Abstract

Elimination of misfolded proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by ER-associated degradation involves substrate retrotranslocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol for degradation by the proteasome. For many substrates, retrotranslocation requires the action of ubiquitinating enzymes, which polyubiquitinate substrates emerging from the ER lumen, and of the p97-Ufd1-Npl4 ATPase complex, which hydrolyzes ATP to dislocate polyubiquitinated substrates into the cytosol. Polypeptides extracted by p97 are eventually transferred to the proteasome for destruction. In mammalian cells, ERAD can be blocked by a chemical inhibitor termed Eeyarestatin I, but the mechanism of EerI action is unclear. Here we report that EerI can associate with a p97 complex to inhibit ERAD. The interaction of EerI with the p97 complex appears to negatively influence a deubiquitinating process that is mediated by p97-associated deubiquitinating enzymes. We further show that ataxin-3, a p97-associated deubiquitinating enzyme previously implicated in ER-associated degradation, is among those affected. Interestingly, p97-associated deubiquitination is also involved in degradation of a soluble substrate. Our analyses establish a role for a novel deubiquitinating process in proteasome-dependent protein turnover.

In eukaryotic cells the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS)2 plays pivotal roles in many protein quality control pathways including the elimination of misfolded proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (1–3). Terminally misfolded ER proteins (both membrane and soluble substrates) are recognized by ER chaperones and targeted to export sites at the ER membrane. Polypeptides are subsequently transferred across the membrane via an unknown conduit to enter the cytosol where they become substrates of the UPS. This pathway, termed retrotranslocation, ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) or dislocation is essential to adapt cells to ER stress caused by protein misfolding (4–6). Interestingly, the retrotranslocation pathway can be hijacked by many viruses to down-regulate the expression of correctly folded cellular proteins involved in the immune defense of cells, which allows these viruses to propagate without being detected by the cytotoxic T cells (7, 8). For example, either of the two proteins (US11 and US2) encoded by human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is able to induce rapid dislocation and degradation of newly synthesized MHC class I heavy chains (9, 10).

Because polypeptides can adopt a variety of incorrectly folded states, different misfolded proteins are likely to be distinguished by discrete mechanisms. Genetic studies in yeast have uncovered at least two routes by which misfolded proteins can be selected to undergo retrotranslocation (11–15). Recent biochemical analyses have identified molecular constituents that account for the mechanistic differences of these pathways. It appears that substrates containing lesions in their luminal domains (ERAD-L substrates) are recognized by chaperones such as Kar2p, Yos9p, and Htm1p/Mn11p, and are targeted to a membrane complex that comprises proteins including Der1p, Usa1p, Hrd3p, and the ubiquitin ligase Hrd1p (16–22). On the other hand, proteins carrying misfolding signals in their cytosolic domains (ERAD-C substrates) are disposed of by a different set of factors associated with another ubiquitin ligase Doa10p (20). When substrates leave the ER, these pathways merge at a highly conserved AAA ATPase (ATPase associated with various cellular activities) termed Cdc48p in yeast or p97/VCP in mammals (23–25). In mammalian cells, p97 can be recruited to the ER membrane via association with two membrane proteins, Derlin and VIMP, which mediate the transport of a subset of substrates to the cytosol (26–32). In yeast, the link of Cdc48p to the ER membrane is provided by Ubx2p (33–35). With the assistance of a dimeric cofactor, Ufd1-Npl4, Cdc48p/p97 acts on both ERAD-L and ERAD-C substrates to extract them from the membrane once these substrates are polyubiquitinated (36–42).

In the next step, substrates dislocated by p97 need to be delivered to the proteasome, which likely occurs in a tightly coupled manner at the ER membrane with the help of some shuttling factors. It was proposed that several ubiquitin-binding proteins including a p97-bound ubiquitin ligase Ufd2 and the proteasome-associated factor Rad23 may form a ubiquitin receiving chain to hand over polyubiquitinated substrates to the proteasome (43). We recently reported that the degradation of several ERAD substrates is also regulated by a p97-associated deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) named ataxin-3 (atx3), which may be part of the substrate delivery system (44). Using EerI as a tool, we now demonstrate the involvement of a p97-associated deubiquitinating process (PAD) in ERAD, which is mediated by p97-associated DUBs such as atx3. We provide evidence that PAD acts on dislocated substrates to facilitate their degradation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Constructs, Antibodies, and Chemicals—The pRK-FLAG-atx3 wt and the C14A mutant plasmids, and the antibodies to ubiquitin, p97 were described previously (44). The pLNCX2-HA-GFPμ plasmid was constructed by ligating the PCR-amplified HA-GFPμ into the BglII and NotI sites of the pLNCX2 vector (Clontech). The pRK-FLAG-HAUSP construct was generated by cloning the PCR-amplified HAUSP cDNA into the SalI and NotI site of the pRK vector. The following primers were used: 5′-ACGCGTCGACCATGAACCACCAGCAGCAGCAGCAGC, 5′-ATAGTTTAGCGGCCGCTCAGTTATGGATTTTAATGGCCTTTTC. FLAG, HA, and GFP antibodies were purchased from Sigma, Roche Applied Science, and Invitrogen, respectively. EerI and MG132 were purchased from Chembridge Inc. and Calbiochem, respectively.

Cell Lines—A9 cells (stably expressing US11 and HA-tagged heavy chain) were described previously (45). TG12 cells (stably expressing TCRα-GFP) were a generous gift of Dr. R. Kopito (Stanford University). To make an astrocytoma cell line expressing HA-tagged GFPμ, a retroviral packaging cell line (GP2-293 cells) was co-transfected with pLNCX2-HA-GFPμ and a plasmid expressing the VSV-G protein. The retrovirus-containing medium was collected 72 h after transfection, and used to infect 373MG cells. HA-GFPμ-expressing cells were selected by neomycin (500 μg/ml). Individual clones were expanded, and a clone that accumulates HA-GFPμ upon MG132 treatment was used in this study.

Mammalian Cell Culture, Transient Gene Expression, Fractionation, and Coimmunoprecipitation—Astrocytoma cells and 293T cells were maintained according to standard procedures. Transfections in 293T cells were done with Trans IT 293 (Mirus). Radiolabeling and fractionation experiments in astrocytoma cells were performed as described previously (36). Briefly, astrocytoma cells expressing US11 were treated with chemicals as indicated in the figure legends. Cells were labeled with 27.5 μCi of [35S]methionine per 1.0 × 106 cells. After washing, the cells were permeabilized by addition of 0.028% digitonin on ice in the presence of an ATP-regenerating system. The samples were then incubated at 37 °C for different time periods and separated into membrane and supernatant fractions. Immunoprecipitation with heavy chain antibodies were done as described (36). To detect ubiquitinated HC, cells were solubilized in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mm sodium chloride, 2 mm magnesium chloride, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and a protease inhibitor mixture. Cell extracts were adjusted to contain 0.2% SDS, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, and 5 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). Samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min before subjected to immunoprecipitation. For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, cells were extracted with buffer N (30 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mm potassium acetate, 4 mm magnesium acetate, 1% DeoxyBigCHAP, and a protease inhibitor mixture). All cell extracts were cleared by centrifugation (20,000 × g) and subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies indicated in the figure legends. Immunoblots were visualized with a LAS3000 cooled CCD camera system. Results were quantified using MultiGauge v3.0 Software.

In Vitro Deubiquitination Experiments—To detect p97-, atx3-, or HAUSP-associated deubiquitination, cells were extracted with buffer N (30 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mm potassium acetate, 4 mm magnesium acetate, 1% DeoxyBigCHAP, and a protease inhibitor mixture). Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with either p97 antibodies or anti-FLAG antibody to isolate p97 or FLAG-tagged atx3/HAUSP. Proteins bound to the beads were incubated in a deubiquitinating buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mm potassium chloride, 5 mm magnesium chloride, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 2.5% bovine serum albumin) at 37 °C. Deubiquitination reaction was stopped by addition of SDS sample buffer. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analyses.

Binding of EerI to a p97 Complex—To detect the association of EerI with p97 complexes, EerI-treated or -untreated cells were lysed in a buffer containing 30 mm Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 150 mm potassium acetate, 4 mm magnesium acetate, 1% DeoxyBigCHAP, 5 mm N-ethylmaleimide, and a protease inhibitor mixture. p97 and its associated factors were immunoprecipitated with an anti-p97 antibody. The beads were washed with a phosphate saline buffer, and the fluorescence intensity was measured using a 488/530 nm filter on a Perkin Elmer 1420 Victor plate reader. The amount of EerI associated with p97 complexes was calculated as Itreated – Iuntreated, wherein Itreated is the fluorescence intensity associated with p97 precipitates in EerI-treated cells and Iuntreated represents the background fluorescence associated with p97 precipitates in untreated cells. As a control, Hsp90 was immunoprecipitated from these extracts, and the associated fluorescence was measured in parallel with p97. Where indicated, p97 was precipitated by a FLAG antibody from extract of either untreated or EerI-treated cells that had also been transfected with FLAG-tagged atx3 or a control empty vector.

RESULTS

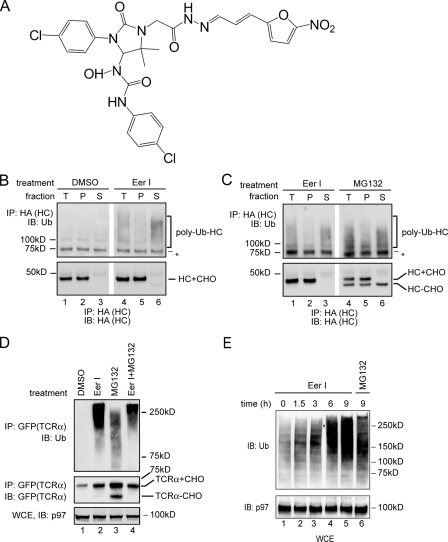

Accumulation of Polyubiquitinated Intermediates in EerI-treated Cells—EerI was identified as a potent inhibitor of ERAD (Fig. 1A), but the precise target of its action is unclear. To understand how EerI influences retrotranslocation, we examined its effect on the degradation of HA-tagged MHC class I heavy chain (HLA-A2) (HC) in astrocytoma cells expressing the HCMV protein US11 (A9 cells). A9 cells treated with EerI or as a control with Me2SO were permeabilized in a buffer containing a low concentration of the detergent digitonin. The permeabilized cells were then subjected to centrifugation to obtain a supernatant fraction that contained cytosol and a pellet fraction that contained the ER membrane (36, 41, 45). HC was immunoprecipitated from detergent extracts of these fractions under denaturing condition, and analyzed by immunoblotting (44, 45). Compared with Me2SO-treated cells, polyubiquitinated HC was accumulated in the cytosol of EerI-treated cells (Fig. 1B, lanes 4 and 6). As a positive control, we treated A9 cells with MG132, a proteasome inhibitor. Consistent with previous reports (9, 36, 45), inhibition of the proteasome function uncoupled dislocation and degradation, leading to an accumulation of polyubiquitinated HC in cytosol (Fig. 1C, lanes 4 and 6). However, a significant fraction of HC accumulated in MG132-treated cells was non-ubiquitinated species with its N-linked glycan removed by a cytosolic N-glycanase (46, 47). The accumulation of these unmodified substrates upon inhibition of the proteasome function has been observed for many proteasome substrates, and was generally attributed to deubiquitination by cytosolic DUBs. Interestingly, compared with MG132-treated cells, EerI-treated cells contained very few such deubiquitinated, deglycosylated HC molecules, although they accumulated a similar amount of polyubiquitinated HC. These results suggest that EerI may inhibit a deubiquitinating process required for the degradation of dislocated HC.

FIGURE 1.

Accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in EerI-treated cells. A, structure of EerI. B, EerI treatment leads to an accumulation of polyubiquitinated HC in cytosol. A9 cells were treated with either Me2SO (DMSO) or EerI (10 μm, 14 h), and permeabilized with the detergent digitonin. A portion of the cells was solubilized directly (T), whereas the rest of each sample was fractionated into a pellet (P) and a supernatant fraction (S). HC was immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-HA antibody under denaturing condition and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB). (HC+CHO, glycosylated HC; HC-CHO, deglycosylated HC; asterisk, a nonspecific protein cross-reacting with the ubiquitin antibody). C, as in B, except that A9 cells treated with either EerI or MG132 (10 μm) were analyzed. D, accumulation of polyubiquitinated TCRα in EerI-treated cells. Where as indicated, TCRα-GFP-expressing cells were treated with both EerI and MG132 (TCRα+CHO, glycosylated TCRα; TCRα-CHO, deglycosylated TCRα). A fraction of the extracts (WCE) was analyzed directly by immunoblotting. E, accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in EerI-treated cells. WCE of 293T cells treated with the indicated compounds were analyzed by immunoblotting.

We next compared the effect of EerI and MG132 on degradation of overexpressed TCRα-GFP, a glycoprotein dislocated from the ER membrane because of the lack of its assembly partner (48–50). Similar to HC, polyubiquitinated TCRα-GFP was accumulated in MG132-treated cells together with a deubiquitinated, deglycosylated species (Fig. 1D, lane 3). In contrast, cells treated with EerI alone or with both EerI and MG132 accumulated polyubiquitinated TCRα-GFP (lanes 2 and 4), but contained few deubiquitinated, deglycosylated TCRα-GFP molecules. These data suggest that EerI may also inhibit the degradation of TCRα by influencing its deubiquitination, a process that occurs upstream of the proteasome.

Consistent with the notion that EerI inhibits a deubiquitinating process, cells exposed to EerI started to accumulate polyubiquitinated proteins ∼1.5 h after treatment. In addition, for a given time period, EerI-treated cells accumulated more polyubiquitinated proteins than MG132-treated cells (Fig. 1E, lane 5 versus lane 6), even though EerI was shown to only affect the degradation of a subset of the proteasomal substrates (51).

EerI Inhibits PAD—Upon reaching the proteasome, many substrates are subjected to deubiquitination by DUBs associated with the proteasome before degradation takes place (52, 53). For those proteins that are handed over to the proteasome via p97 (such as the ERAD substrates), their deubiquitination appears to begin while these substrates are still bound by p97. Recent studies suggested that atx3, a p97-associated DUB, may promote deubiquitination at p97 to facilitate ER-associated degradation (44, 54). Thus, it is possible that EerI may target PAD. This assumption would explain why several non-ERAD substrates are not affected by EerI (51).

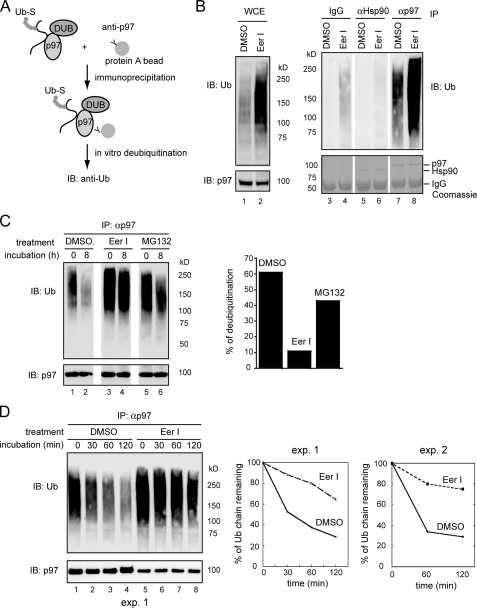

To study PAD, we used a previously established in vitro deubiquitination assay. p97 and its associated substrates were immunoprecipitated from cell extracts and incubated in vitro. Ubiquitin chains on these substrates were deconjugated by DUBs present in the precipitated complex, leading to a reduction in polyubiquitin conjugates (Fig. 2A) (44). Interestingly, in vitro deubiquitination of p97 substrates was slow unless ATP was present (supplemental Fig. S1). This is unlikely caused by ATP-dependent degradation by the proteasome, because the proteolytic subunits of the proteasome were not detected in the p97 immunoprecipitates under this condition (44). Perhaps, p97-bound substrates needed to be released in an ATP-dependent reaction before they could gain access to a p97-associated DUB.

FIGURE 2.

EerI inhibits PAD. A, scheme of the in vitro deubiquitination experiment. Ub-S, ubiquitinated substrates. B, EerI increases the level of p97-bound polyubiquitinated substrates. 293T cells treated with either Me2SO (DMSO) or EerI (10 μm, 12 h) were lysed in a deoxyBigCHAP lysis buffer. A fraction of the lysate was analyzed directly by immunoblotting (IB)(WCE). The rest of the samples were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies. Bottom panels are Coomassie Blue-stained gels. C, p97 and its associated proteins were immunoprecipitated from detergent extracts of DMSO-, MG132-, or EerI-treated cells, and incubated in vitro for the indicated time points. The graph shows the quantification of the experiment. D, as in C, except that ATP (5 mm) was included in the deubiquitinating reactions. Note that only 30% of the immunoprecipitated material for EerI-treated samples was loaded on the gel. The graphs show the quantification of two independent experiments (exp.).

Because EerI did not inhibit the retrotranslocation and degradation of MHC class I heavy chain when added to permeabilized US11 cells (data not shown), we suspected that EerI might need to be metabolized into an active species in intact cells to exert its inhibitory effect. Consistent with this interpretation, US11 cells grown in suspension after being treated with trypsin no longer responded to EerI (supplemental Fig. S2). These trypsin-treated cells apparently could still take up EerI because they became yellowish after exposure to EerI and emitted fluorescence when excited with an appropriate light (EerI is a yellow chemical that emits fluorescence at the wavelength of 488 nm) (Fig. 7A). Thus, it is possible that trypsinization or permeabilization of cells disrupts certain cellular pathways required for activation of EerI. For this reason, we first treated cells with EerI or as a control with Me2SO. The p97-substrate complex was then immunopurified from these cells, and subjected to deubiquitination in vitro. Compared with control cells, significantly more polyubiquitinated proteins were bound to p97 in EerI-treated cells (Fig. 2B, lane 8 versus lane 7). In contrast, when Hsp90, an abundant cytosolic protein, was immunoprecipitated, little ubiquitinated proteins were co-precipitated (lanes 5 and 6). When p97-associated substrates were subjected to in vitro deubiquitination by DUBs co-precipitated with p97, substrates isolated from EerI-treated cells were significantly more stable (only reduced by ∼10% after incubation compared with ∼60% for substrates isolated from control cells) (Fig. 2C, lanes 3, 4 versus lanes 1, 2). Kinetic experiment further supported this conclusion (Fig. 2D, lanes 5–8 versus lanes 1–4). On the other hand, inhibition of the proteasome function only slightly affected PAD (Fig. 2C, lanes 5–6, also see the graph in Fig. 2C). Together, these data suggest that EerI inhibits deubiquitination associated with p97.

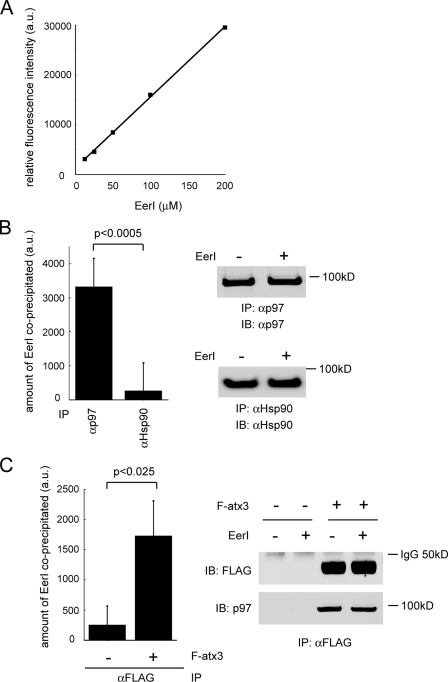

FIGURE 7.

EerI associates with a p97 complex in cells. A, EerI emits fluorescence. a.u. artificial unit. B, association of EerI with p97. Endogenous p97 or Hsp90 was immunoprecipitated from extracts of EerI-treated 293T cells. The amount of EerI co-precipitated was determined by measuring the fluorescence associated with the precipitated material as described under “Experimental Procedures.” p97 or Hsp90 purified from untreated cells was used as blank. The immunoprecipitated proteins were also analyzed by IB with the indicated antibodies. Error bars show S.D. of five independent experiments. C, association of EerI with p97-atx3 complex. Endogenous p97 was immunoprecipitated (IP) with FLAG antibody from extract of EerI-treated cells that had been transfected with FLAG-atx3 (F-atx3). The amount of EerI present in the precipitated complex was determined as described under “Experimental Procedures.” As a control, cells transfected with an empty vector was used (–). The gel show the precipitated proteins determined by immunoblotting. Error bars show the S.D. of three independent experiments.

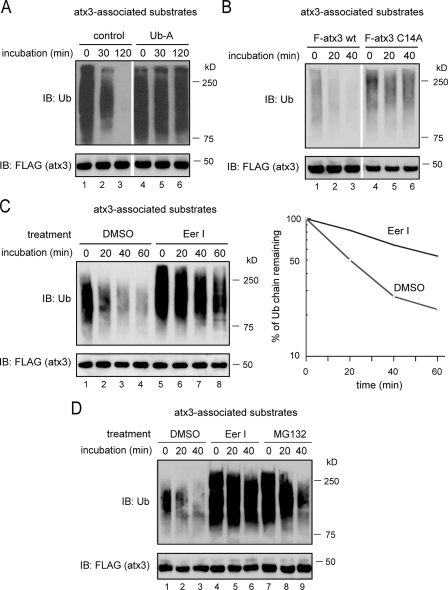

EerI Inhibits atx3-mediated Deubiquitination—Because atx3 acts downstream of p97 to promote deubiquitination of substrates dislocated by p97 during retrotranslocation (44), we wanted to determine whether EerI affects atx3-associated deubiquitination. To study atx3-dependent deubiquitination, atx3 and its associated substrates were immunoprecipitated from detergent extracts of 293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged atx3, and incubated in vitro in the absence of ATP. Immunoblotting showed that ubiquitinated proteins bound by atx3 were rapidly turned over, which was apparently caused by deubiquitination because it could be inhibited by ubiquitin aldehyde, a deubiquitination inhibitor (Fig. 3A, lanes 4–6 versus lanes 1–3). In addition, because substrates co-precipitated with a deubiquitination defective atx3 mutant (atx3 C14A) remained relatively stable under the same condition (Fig. 3B), the disappearance of atx3-associated substrates in this reaction was primarily caused by atx3-mediated deubiquitination.

FIGURE 3.

EerI inhibits atx3-dependent deubiquitination. A and B, atx3-dependent deubiquitination. A, FLAG-tagged atx3 and its associated proteins were immunoprecipitated from detergent extracts of atx3-expressing cells, and subjected to in vitro deubiquitination. Where indicated, the precipitated materials were incubated in the presence of ubiquitin aldehyde (Ub-A). B, ubiquitinated substrates bound to either FLAG-tagged wild-type atx3 (F-atx3) or to FLAG-tagged atx3 C14A (F-atx3 C14A) were analyzed by in vitro deubiquitination. C, EerI inhibits atx3-dependent deubiquitination. atx3 and its associated proteins immunoprecipitated from detergent extracts of Me2SO (DMSO)- or EerI-treated cells (10 μm, 5 h) were incubated and analyzed as in A. The graph shows the quantification of the experiment. D, as in C, except that the atx3-substrate complex isolated from cells treated with MG132 was also included, and that the treatment time was 10 h.

In accordance with the idea that EerI may need to be converted into an active form in cells to inhibit the degradation of p97 substrates, adding EerI to purified atx3-substrate complex had no effect on atx3-mediated deubiquitination (data not shown). We therefore isolated atx3-substrate complex from cells treated with Me2SO, EerI, or MG132, and analyzed the deubiquitination of atx3-associated substrates in vitro. Compared with control cells, atx3-bound ubiquitin conjugates from EerI-treated cells were more resistant to deubiquitination (Fig. 3C, lanes 5–8 versus lanes 1–4). By contrast, ubiquitin chains on atx3 substrates isolated from MG132-treated cells were rapidly deconjugated similar to those purified from control cells (Fig. 3D, lanes 7–9 versus lanes 1–3). These data suggest that EerI inhibits atx3-associated deubiquitination.

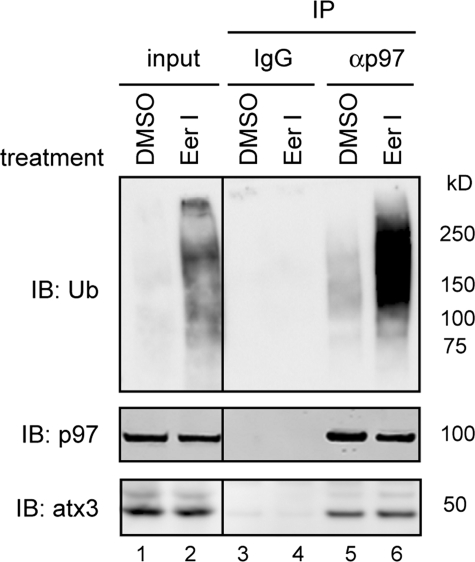

To see whether EerI could irreversibly inhibit the enzymatic activity of atx3, atx3 purified from EerI-treated cells was analyzed for its ability to disassemble excess chemically synthesized ubiquitin conjugates (Ub2–7). The results indicated that atx3 isolated from EerI-treated cells still retained deubiquitinating activity toward exogenously added substrate (Ub2–7) (supplemental Fig. S3). Thus, EerI appears to inhibit atx3-associated deubiquitination without irreversibly abolishing its enzymatic activity. Further, because the association of p97 with atx3 was not disrupted in EerI-treated cells (Fig. 4, lane 6 versus lane 5), EerI or its metabolites may influence atx3-associated deubiquitination possibly by acting on a cofactor that is associated with the p97-atx3 complex (see below).

FIGURE 4.

EerI does not disrupt the interaction between p97 and atx3. Detergent extracts of 293T cells treated with Me2SO (DMSO) or EerI were subjected to immunoprecipitation with either control (IgG) or anti-p97 (αp97) antibodies. The immunoprecipitated material was immunoblotted (IB) with the indicated antibodies. Where indicated, a fraction of the extract (input, 15%) was directly analyzed by immunoblotting.

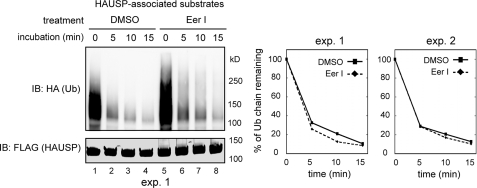

To see whether EerI could influence deubiquitinating process mediated by other DUBs, we tested the effect of EerI on HAUSP-associated deubiquitination. HAUSP is a deubiquitinating enzyme that regulates the stability of many cellular factors including the tumor suppressor protein p53 (55). To this end, we expressed FLAG-tagged HAUSP in 293T cells, and treated these cells with either EerI or Me2SO. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody to purify HAUSP and its associated ubiquitinated substrates. EerI treatment moderately increased the amount of ubiquitinated proteins associated with HAUSP (Fig. 5, lane 5 versus lane 1), which may be caused by an interaction of HAUSP with the accumulated polyubiquitinated proteins in EerI-treated cell extract. Nonetheless, when HAUSP-associated deubiquitination was measured, HAUSP-bound substrates isolated from either Me2SO- or EerI-treated cells both decayed rapidly (Fig. 5). These experiments suggest that HAUSP-associated deubiquitination is not affected by EerI.

FIGURE 5.

EerI does not affect HAUSP-associated deubiquitination. 293T cells transfected with a plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged HAUSP together with HA-ubiquitin were treated as indicated. HAUSP and its associated substrates were immunoprecipitated from detergent extracts. HAUSP-mediated deubiquitination was analyzed. The graphs show the quantification of two independent experiments (exp.).

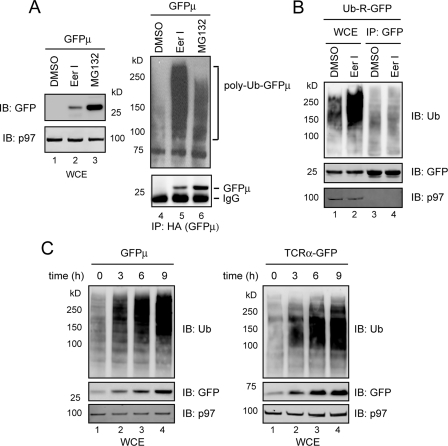

EerI Inhibits the Degradation of a Soluble Substrate—Because the degradation of GFPμ, a soluble proteasome substrate (56) is strongly influenced by expression of an atx3 mutant (57), we speculated that the degradation of GFPμ may involve PAD. Consistent with this interpretation, expression of a dominant negative p97 mutant stabilized GFPμ in part as a p97-associated form (data not shown), confirming that GFPμ is a p97 substrate. We therefore tested whether EerI could inhibit the degradation of GFPμ. Indeed, in EerI-treated cells, GFPμ was present almost exclusively as a polyubiquitinated form. This was in contrast to MG132-treated cells in which GFPμ was mostly accumulated in a deubiquitinated form, and only to a lesser extent as polyubiquitinated species (Fig. 6A, lane 6 versus lane 5). On the other hand, the degradation of Ub-R-GFP, a substrate whose degradation is independent of atx3 (44), was not affected by EerI-treatment (Fig. 6B). Kinetic experiments showed that GFPμ was accumulated in EerI-treated cells at a similar rate as the ERAD substrate TCRα-GFP (Fig. 6C), indicating that the blockage in the degradation of GFPμ is not a secondary defect of ERAD inhibition. Together, these data indicate that EerI also delays the degradation of a soluble p97 substrate by influencing its deubiquitination.

FIGURE 6.

EerI inhibits the degradation of a cytosolic p97 substrate. A, EerI inhibits the degradation of GFPμ. Astrocytoma cells stably expressing HA-tagged GFPμ were treated with the indicated chemicals (12 h). The steady state levels of GFPμ in WCE were analyzed by IB. Where indicated, GFPμ was first immunoprecipitated before immunoblotting. B, EerI does not affect the degradation of Ub-R-GFP. C, rate of GFPμ accumulation in EerI-treated cells correlates with that of an ERAD substrate. Stable cell lines expressing either GFPμ or TCRα-GFP were treated with EerI for the indicated time points. WCE were analyzed by IB.

A p97 Complex Is Targeted by EerI—To understand how EerI affects p97-associated deubiquitination, we tested whether EerI could associate with p97 complexes in cells. We took advantage of the observation that EerI emitted fluorescence when excited with an appropriate light (Fig. 7A). If EerI associates with a p97 complex, we should be able to detect fluorescence emitted from p97 complexes isolated from EerI-treated cells. Indeed, p97 complex purified from EerI-treated cells consistently emitted fluorescence at higher levels than that isolated from untreated cells, which we took as background. By contrast, little fluorescence was detected in association with Hsp90 in EerI-treated cells (Fig. 7B). Moreover, when we purified p97 by precipitating its interaction partner atx3, we also observed fluorescence emitted from samples purified from EerI-treated cells (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these results suggest that EerI can associate with a p97 complex in cells.

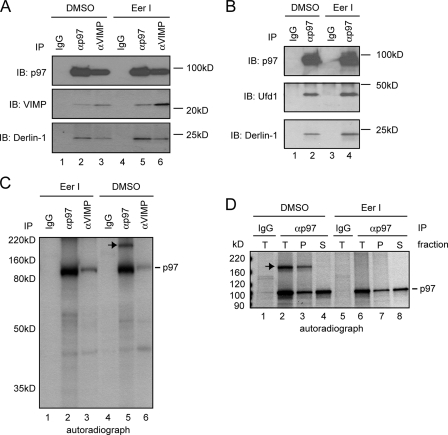

To further understand how EerI affects the function of p97, we analyzed the interaction of p97 with its known partners in EerI-treated cells. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments showed that EerI did not disrupt the interaction of p97 with Derlin-1 and VIMP (Fig. 8A), neither was its association with Ufd1 affected (Fig. 8B). However, when we purified p97 from cells radiolabeled with [35S]methionine, an unknown protein of ∼180 kDa was found to interact with p97 in untreated cells, but not in EerI-treated cells (Fig. 8C, lane 5 versus lane 2). Interestingly, fractionation experiments showed that the interaction of p97 with this 180 kDa protein was exclusively restricted to the membrane fraction (Fig. 8D, lane 3 versus lane 4). Together, these data suggest that EerI selectively disrupts the interaction of p97 with certain factors in cells.

FIGURE 8.

EerI targets a p97 complex. A, EerI does not affect the association of p97 with Derlin-1 and VIMP. Endogenous proteins from extracts of 293T cells were analyzed by immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies followed by immunoblotting. B, EerI does not affect the association of p97 with Ufd1. C, EerI treatment alters a p97 complex. EerI-treated or -untreated astrocytoma cells were radiolabeled with [35S]Met/Cys. Detergent extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the indicated antibodies. Note that the short labeling time used did not allow the labeling of all p97 cofactors. Nonetheless, an unknown protein of 180 kDa (indicated by the arrow) was found in association with p97 only in untreated cells. D, interaction of the 180 kDa protein with p97 is exclusively on the membrane. Astrocytoma cells were treated with either Me2SO (DMSO) or EerI, and permeabilized with the detergent digitonin. A portion of the cells was solubilized directly (T), whereas the rest of each sample was fractionated into a pellet (P) containing the ER membrane and a supernatant fraction (S) containing cytosol before subjected to solubilization and immunoprecipitation.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we demonstrate that EerI inhibits some deubiquitination reactions associated with the dislocase p97. We further identified atx3 as one of the DUBs affected by EerI. We previously showed that atx3 functions downstream of p97, and the latter hydrolyzes ATP to extract ERAD substrates from the ER membrane. Thus, atx3-mediated PAD appears to act preferentially on substrates that have been extracted from the ER membrane. Accordingly, inhibition of PAD should result in accumulation of a fraction of polyubiquitinated retrotranslocation substrates in cytosol, which was indeed observed in cells treated with EerI (Fig. 1, B and C). Interestingly, a previous study has proposed that EerI may inhibit ERAD by blocking substrate dislocation from the ER membrane (51). Our finding that the degradation of a cytosolic proteasome substrate, which does not involve membrane dislocation, is also inhibited by EerI argues against this model. Instead, it favors the idea that the target of EerI must reside in cytosol, which is in line with our interpretation that EerI targets certain cytosolic deubiquitinating activities associated with p97.

The discrepancy between the two reports is likely caused by the different methodologies used in these studies. In previously published work, the fate of newly synthesized MHC class I heavy chain was examined by pulse-chase experiments after cells were treated with EerI for 16 h. Because EerI treatment causes accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in cells, which should lead to depletion of the free ubiquitin pool, and because ubiquitin is required for heavy chain dislocation in US11 cells (58, 59), it is possible that a prolonged treatment with EerI may ultimately block dislocation as a consequence of ubiquitin deficiency induced by lack of deubiquitination. In this case, the cytosolic accumulation of polyubiquitinated ERAD substrates prior to dislocation inhibition can only be detected by examining the steady state level of these substrates as shown in this study, but would escape detection by the previously published approach.

Our results suggest that EerI can associate with a p97 complex to influence a downstream deubiquitination process. We attempted to determine the in vitro ATPase activity of p97 that had been purified from either EerI-treated or untreated cells. We found that EerI treatment did not lower the ATPase activity of p97 (data not shown). This is consistent with our finding that fully dislocated MHC class I heavy is accumulated in the cytosol of EerI-treated cells. These data indicate that EerI-induced defect in deubiquitination is unlikely a secondary consequence of inactivation of the p97 ATPase activity.

How does EerI act to influence PAD? The binding of EerI to p97 complexes does not block the interaction between p97 and the deubiquitinating enzyme atx3 (Fig. 4), neither does it irreversibly inactivate the enzymatic activity of atx3. Thus, EerI might cause a conformational change in certain constituents of a p97 complex or alter its composition by influencing the association of p97 with some other cofactors. Our co-immunoprecipitation data indicate that at least the association of p97 with an unknown protein of 180 kDa is disrupted in cells treated with EerI. Characterizing the identity of this 180 kDa protein may provide some clues on how EerI influences the function of p97.

Why would substrates need to be deubiquitinated by enzymes associated with p97? Although ubiquitin chains consisting of at least 4 ubiquitin moieties are required for guiding a substrate to the proteasome, these conjugates eventually need to be removed by DUBs associated with the proteasome before degradation can take place efficiently (52, 53). Thus, it is possible that p97-associated deubiquitination may partially trim ubiquitin chains attached to a p97 substrate, which may facilitate the subsequent disassembly of these ubiquitin chains by a downstream proteasome-associated DUB. Alternatively, p97-associated DUBs may have an editing function to disassemble ubiquitin chains containing incorrect linkages. This would ensure that substrates to be transferred to the proteasome always carry ubiquitin chains with the proper linkage.

Several lines of evidence suggest that EerI may need to be metabolized into an active species to exert its inhibitory effect. First, EerI does not inhibit atx3-mediated deubiquitination unless atx3-substrate complex purified from EerI-treated cells is analyzed. Second, US11 cells grown in suspension after being treated with trypsin no longer respond to EerI. Third, when added to permeabilized US11 cells, EerI fails to inhibit retrotranslocation of MHC class I heavy chain even at a concentration 15 times higher than that needed to block HC degradation in intact cells (data not shown). Presumably, trypsinization or permeabilization of cells disrupts certain cellular pathways required to activate EerI.

In summary, our results suggest that EerI specifically targets a subset of deubiquitinating processes in cells that are associated with p97. Since the UPS plays a critical role in cell cycle progression, which is particularly essential for the survival of cancer cells, an UPS inhibitor like EerI may offer attractive therapeutic possibilities for certain types of human cancer. Indeed, a proteasome inhibitor named bortezomib has recently been approved for treating patients with multiple myeloma (60). It would be interesting to test whether EerI can be further developed to become an anti-cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Will Prinz, Martin Gellert, and Tom Rapoport, for critical reading of the manuscript, Ron Kopito (Stanford University) for TCRα-GFP-expressing cell line, and the GFPμ plasmid, and Wei Gu (Columbia University) for HAUSP cDNA.

This work was supported by an Intramural Research Program of the NIDDK at the National Institutes of Health. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: UPS, ubiquitin proteasome system; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERAD, ER-associated protein degradation; PAD, p97-associated deubiquitination; DUB, deubiquitinating enzyme; HC, MHC class I heavy chain; atx3, ataxin-3; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; HA, hemagglutinin; GFP, green fluorescent protein; WCE, whole cell extract; IP, immunoprecipitate; IB, immunoblotting; Me2SO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

References

- 1.Hampton, R. Y. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14 476–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romisch, K. (2005) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21 435–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meusser, B., Hirsch, C., Jarosch, E., and Sommer, T. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7 766–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng, D. T., Spear, E. D., and Walter, P. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150 77–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedlander, R., Jarosch, E., Urban, J., Volkwein, C., and Sommer, T. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2 379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Travers, K. J., Patil, C. K., Wodicka, L., Lockhart, D. J., Weissman, J. S., and Walter, P. (2000) Cell 101 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lybarger, L., Wang, X., Harris, M. R., Virgin, H. W. T., and Hansen, T. H. (2003) Immunity 18 121–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lilley, B. N., and Ploegh, H. L. (2005) Immunol. Rev. 207 126–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiertz, E. J. H. J., Jones, T. R., Sun, L., Bogyo, M., Geuze, H. J., and Ploegh, H. L. (1996) Cell 84 769–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiertz, E. J. H. J., Tortorella, D., Bogyo, M., Yu, J., Mothes, W., Jones, T. R., Rapoport, T. A., and Ploegh, H. L. (1996) Nature 384 432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson, R., Locher, M., and Hochstrasser, M. (2001) Genes Dev. 15 2660–2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caldwell, S. R., Hill, K. J., and Cooper, A. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 23296–23303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vashist, S., Kim, W., Belden, W. J., Spear, E. D., Barlowe, C., and Ng, D. T. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155 355–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taxis, C., Hitt, R., Park, S. H., Deak, P. M., Kostova, Z., and Wolf, D. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 35903–35913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vashist, S., and Ng, D. T. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 165 41–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buschhorn, B. A., Kostova, Z., Medicherla, B., and Wolf, D. H. (2004) FEBS Lett. 577 422–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhamidipati, A., Denic, V., Quan, E. M., and Weissman, J. S. (2005) Mol. Cell 19 741–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szathmary, R., Bielmann, R., Nita-Lazar, M., Burda, P., and Jakob, C. A. (2005) Mol. Cell 19 765–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, W., Spear, E. D., and Ng, D. T. (2005) Mol. Cell 19 753–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carvalho, P., Goder, V., and Rapoport, T. A. (2006) Cell 126 361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denic, V., Quan, E. M., and Weissman, J. S. (2006) Cell 126 349–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauss, R., Jarosch, E., Sommer, T., and Hirsch, C. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8 849–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bays, N. W., and Hampton, R. Y. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12 R366–R371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye, Y. (2005) Essays Biochem. 41 99–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye, Y. (2006) J. Struct. Biol. 156 29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye, Y., Shibata, Y., Kikkert, M., van Voorden, S., Wiertz, E., and Rapoport, T. A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 14132–14138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilley, B. N., and Ploegh, H. L. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 14296–14301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye, Y., Shibata, Y., Yun, C., Ron, D., and Rapoport, T. A. (2004) Nature 429 841–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lilley, B. N., and Ploegh, H. L. (2004) Nature 429 834–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Younger, J. M., Chen, L., Ren, H. Y., Rosser, M. F., Turnbull, E. L., Fan, C. Y., Patterson, C., and Cyr, D. M. (2006) Cell 126 571–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oda, Y., Okada, T., Yoshida, H., Kaufman, R. J., Nagata, K., and Mori, K. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 172 383–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun, F., Zhang, R., Gong, X., Geng, X., Drain, P. F., and Frizzell, R. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 36856–36863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knop, M., Finger, A., Braun, T., Hellmuth, K., and Wolf, D. H. (1996) EMBO J. 15 753–763 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuber, O., Jarosch, E., Volkwein, C., Walter, J., and Sommer, T. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7 993–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuberth, C., and Buchberger, A. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7 999–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye, Y., Meyer, H. H., and Rapoport, T. A. (2001) Nature 414 652–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bays, N. W., Wilhovsky, S. K., Goradia, A., Hodgkiss-Harlow, K., and Hampton, R. Y. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12 4114–4128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hitchcock, A. L., Krebber, H., Frietze, S., Lin, A., Latterich, M., and Silver, P. A. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12 3226–3241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabinovich, E., Kerem, A., Frohlich, K. U., Diamant, N., and Bar-Nun, S. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22 626–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun, S., Matuschewski, K., Rape, M., Thoms, S., and Jentsch, S. (2002) EMBO J. 21 615–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ye, Y., Meyer, H. H., and Rapoport, T. A. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 162 71–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong, X., Shen, Y., Ballar, P., Apostolou, A., Agami, R., and Fang, S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 45676–45684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richly, H., Rape, M., Braun, S., Rumpf, S., Hoege, C., and Jentsch, S. (2005) Cell 120 73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, Q., Li, L., and Ye, Y. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 174 963–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shamu, C. E., Story, C. M., Rapoport, T. A., and Ploegh, H. L. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147 45–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blom, D., Hirsch, C., Stern, P., Tortorella, D., and Ploegh, H. L. (2004) EMBO J. 23 650–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirsch, C., Blom, D., and Ploegh, H. L. (2003) EMBO J. 22 1036–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huppa, J. B., and Ploegh, H. L. (1997) Immunity 7 113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu, H., and Kopito, R. R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 36852–36858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeLaBarre, B., Christianson, J. C., Kopito, R. R., and Brunger, A. T. (2006) Mol. Cell 22 451–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiebiger, E., Hirsch, C., Vyas, J. M., Gordon, E., Ploegh, H. L., and Tortorella, D. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15 1635–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verma, R., Aravind, L., Oania, R., McDonald, W. H., Yates, J. R., 3rd, Koonin, E. V., and Deshaies, R. J. (2002) Science 298 611–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao, T., and Cohen, R. E. (2002) Nature 419 403–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhong, X., and Pittman, R. N. (2006) Hum. Mol. Genet. 15 2409–2420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li, M., Chen, D., Shiloh, A., Luo, J., Nikolaev, A. Y., Qin, J., and Gu, W. (2002) Nature 416 648–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bence, N. F., Bennett, E. J., and Kopito, R. R. (2005) Methods Enzymol. 399 481–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burnett, B., Li, F., and Pittman, R. N. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 3195–3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shamu, C. E., Flierman, D., Ploegh, H. L., Rapoport, T. A., and Chau, V. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12 2546–2555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kikkert, M., Hassink, G., Barel, M., Hirsch, C., van der Wal, F. J., and Wiertz, E. (2001) Biochem. J. 358 369–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adams, J. (2004) Cancer Cell 5 417–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.