Abstract

We demonstrate that purified recombinant human betainehomocysteine methyltransferase-2 (BHMT-2) is a zinc metalloenzyme that uses S-methylmethionine (SMM) as a methyl donor for the methylation of homocysteine. Unlike the highly homologous betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT), BHMT-2 cannot use betaine. The Km of BHMT-2 for SMM was determined to be 0.94 mm, and it has a turnover number similar to BHMT. Several compounds were tested as inhibitors of recombinant human BHMT and BHMT-2. The SMM-specific methyltransferase activity of BHMT-2 is not inhibited by dimethylglycine and betaine, whereas the former is a potent inhibitor of BHMT. Methionine is a stronger inhibitor of BHMT-2 than BHMT, and S-adenosylmethionine does not inhibit BHMT but is a weak inhibitor of BHMT-2. BHMT can use SMM as a methyl donor with a kcat/Km that is 5-fold lower than the kcat/Km for betaine. However, SMM does not inhibit BHMT activity when it is presented to the enzyme at concentrations that are 10-fold greater than the subsaturating amounts of betaine used in the assay. Based on these data, it is our current hypothesis that in vivo most if not all of the SMM-dependent methylation of homocysteine occurs via BHMT-2.

Homocysteine (Hcy)3 is derived from methionine (Met) and can either be methylated to reform Met (i.e. remethylation) or participate in cysteine biosynthesis via the transsulfuration pathway. Hcy remethylation in mammals has always been attributed to two different enzymes: cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase and betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT; EC 2.1.1.5). Methionine synthase uses 5-methyltetrahydrofolate as the methyl donor and is expressed in all tissues at very low levels, whereas BHMT uses betaine (Bet) as the methyl donor and is only expressed in the liver and kidney, but at very high levels (1–3).

Apart from the mammalian methyltransferases described above, the existence of other Hcy methyltransferase (HMT) activities in rat liver extracts, namely S-methylmethionine (SMM)- and S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet)-HMT, were reported by Shapiro and Yphantis in the late fifties (4). SMM, also known as vitamin U, is an analog of AdoMet, with a methyl group substituted for the adenosyl group. This amino acid is a major sulfur containing metabolite of many plants (5–7) but it is not known to be synthesized by mammals.

In 2000, Chadwick et al. (8) reported mouse and human cDNA sequences whose deduced amino acid sequences had very high homology to BHMT. They were named Bhmt-2 and BHMT-2, respectively, even though their enzymatic activities were not determined. Like human BHMT, the human BHMT-2 mRNA was shown to be abundantly expressed in liver and kidney. BHMT and BHMT-2 are adjacent to each other on human chromosome 5 (5q13), suggesting they are tandem duplicates. We demonstrate herein that the translational product of the cDNA named BHMT-2 is a zinc metalloenzyme that methylates Hcy using SMM, and to a much lesser extent, AdoMet as methyl donors in vitro. We also show that purified recombinant human BHMT has SMM-HMT activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—4-(2-Pyridylazo)resorcinol was purchased from Sigma. Dimethylsulfonioacetate (DMSA) was a gift from Nutriquest. SMM iodide was purchased from Acros Biochemicals, Inc. l-[methyl-14C]S-Adenosyl-l-methionine (52.8 mCi/mmol) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Unlabeled AdoMet was obtained from New England Biolabs. All other reagents were of the highest purity available from commercial vendors.

Generation of the Human BHMT-2 Intein/Chitin Binding Fusion Construct (pTBY3-hBHMT-2)—The cDNA encoding human BHMT-2 (accession number AF257473) was a gift from Dr. Joseph Nadeau (Case Western Reserve University). The BHMT-2 cDNA was amplified by PCR with Pfu DNA Polymerase (Stratagene) and the following forward and reverse primers: 5′-ATATATACCATGGCACCTGCTGGAC-3′ and 5′-TATATAGCTCTTCCGCAGAAGTCTGGCTTTGAC-3′. The reverse primer was designed to oblate the stop codon and introduce a unique SapI site in the cDNA so as to fuse it with the intein/chitin-binding sequence of the pTBY3 vector. The PCR product and pTYB3 were digested with NcoI and SapI, gel purified, ligated together, and transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells. The pTBY3-hBHMT-2 construct was verified by DNA sequencing.

Overexpression and Purification of Human BHMT and Human BHMT-2—BHMT and BHMT-2 were purified using the IMPACT™-T7 protein purification system (New England Biolabs) as described by Breska and Garrow (9). Minor changes included the use of protease inhibitors during the isolation of BHMT-2, on-column cleavage of BHMT at ambient temperature rather than 4 °C, and enzymes were concentrated as needed using Amicon Centricon YM-30 cartridges. Enzymes were dialyzed against buffer (20–50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8) containing modest amounts of dithiothreitol or 2-mercaptoethanol, and either 20% (BHMT) or 40% (BHMT-2) glycerol. Protein concentrations were determined by a Coomassie Blue dye-binding assay (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Protein purity was confirmed by SDS-PAGE.

Zinc Binding Assays—To determine the zinc content of the enzymes a microplate-based, spectroscopic assay utilizing the zinc chelator 4-(2-pyridylazo)resorcinol was performed. Aliquots of BHMT or BHMT-2 (10 μm final concentration) were digested for 15 h at 37 °C in 100 μl of buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mm CaCl2, and 3 units of proteinase K (Sigma). Also, a 1-ml mock digest containing buffer alone was used for a background spectroscopic reference and to generate a zinc chloride standard curve (1, 5, 7.5, 12.5, and 25 μm). Ninety μl of each digest was distributed into a 96-well microplate and thoroughly mixed with 90 μl of 4-(2-pyridylazo)resorcinol buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8), 800 mm NaCl, and 200 μm 4-(2-pyridylazo)resorcinol). The absorbance of each sample was measured at 500 nm and compared against the standard curve to determine zinc content. All digest reactions were done in triplicate.

SMM Synthesis—l-[methyl-14C]SMM was synthesized from l-[methyl-14C]Met essentially as described (10) with modifications. Two ml of l-[methyl-14C]Met (Moravek Biochemicals; 55 mCi/mmol) was dried down in an Eppendorf Vacufuge 5301 at 60 °C to remove ethanol. The Met was then resuspended in 225 μl of a solution containing 5.4 m HCl and 2.7 m methanol and transferred to a 0.3-ml Reacti-Vial and incubated for 17 h at 100 °C. The reaction mixture was then diluted to 2 ml with ddH2O and dried down at 45 °C. The material was then resuspended in 1 ml of ddH2O and applied to 1-ml Dowex® 1-X4 (OH–, 200 mesh; Sigma) and Bio-Rex®70 (H+; Bio-Rad) columns arranged in tandem. The 2-column arrangement was washed (2 × 5 ml) with ddH2O. The Bio-Rex column (containing l-[methyl-14C]SMM) was then washed (2 × 5 ml) with ddH2O, followed by elution of the product with 5 ml of 1 m HCl. This procedure resulted in conversion of ∼90% of the l-[methyl-14C]Met to l-[methyl-14C]SMM. Aliquots (250 μl) of l-[methyl-14C]SMM in 1 m HCl were dried down at 45 °C, resuspended in 250 μl of ddH2O and dried down at 45 °C, and resuspended in 125 or 250 μl of 5 mm H2SO4 and 10 mm ethanol for use in enzyme assays.

Enzyme Assays—BHMT activity was assayed as previously described (3). SMM-HMT activity was assayed by the same procedure because like Bet, SMM does not bind to Dowex 1-X4 OH– resin. The concentration of substrates, total assay volume, and amount of enzyme varied in different experiments as indicated in the table legends. Some experiments used 50 mm (final) Hepes-KOH (pH 7.5) rather than 50 mm (final) Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) in the assay mixture. No difference in enzymatic activity was detected between the two buffers.

Radiolabeled SMM and AdoMet were supplemented with cold SMM iodide and AdoMet (New England Biolabs), respectively, to achieve the desired concentration of each methyl donor. Concentrations of unlabeled AdoMet or AdoHcy were determined by UV spectroscopy using a molar extinction coefficient of 15,400. Inhibition assays used the same buffer conditions as the standard assays, except that 0.2 or 2 mm Bet, Met, DMG, DMSA, DMSP, SMM, AdoMet, AdoHcy, or SMM, or 50 or 500 μm S-(δ-carboxybutyl)-l-homocysteine (CBHcy: a transition state analog and potent inhibitor of BHMT activity (11)) was present. The Km of BHMT and BHMT-2 for SMM were determined in the same buffer conditions as the standard assay, except that 270 nCi of radioactivity and varying concentrations of SMM (0.1–9 mm final) were used. Reaction tubes were kept in ice-water until transferred to a 37 °C water bath to initiate the reaction. Assays were incubated for 1 h and then stopped by transferring the tubes back to an ice-water bath. One to 3 ml of cold ddH2O was then added to each reaction. Unreacted radiolabeled methyl donor (Bet, SMM, or AdoMet) was separated from radiolabeled product (Met) for each reaction by application to a 1-ml ion exchange column. For reactions containing Bet or SMM, samples were applied to Dowex 1-X4 OH– columns and subsequently washed with (3 × 5 ml) cold ddH2Oto remove unreacted substrate. Met was eluted into scintillation vials by the addition of 3 ml of 1.5 n HCl. Seventeen ml of scintillation fluid (Scinti-Safe™ Econo 1, Fisher Scientific) was then added and counted. For AdoMet-containing reactions, samples were applied to Bio-Rex 70 H+ columns (12), and the flow-through (containing Met) was collected into a vial. The column was then washed (3 × 3 ml) with cold ddH2O and collected in the same vial, which then was capped, briefly vortexed, and a portion (3 ml) transferred to a scintillation vial. Seventeen ml of scintillation fluid was then added and counted. Resultant counts were multiplied by 3.33 to represent the disintegrations/min in 10 ml. For all reactions, blank reactions without enzyme were counted, and their values were subtracted from samples containing enzyme. All assays were done in duplicate or triplicate, had an average standard deviation of 3.1%, and are reported as means. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism 4 software.

RESULTS

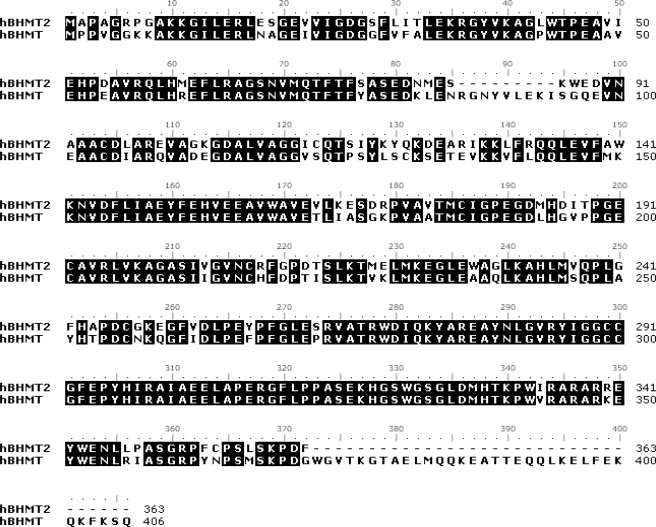

Comparative Amino Acid Sequence and Structural Analysis of Human BHMT and Human BHMT-2—The BHMT-2 gene encodes for a 40-kDa protein that shares 73% sequence identity with the 45-kDa BHMT protein (8). Sequence alignments indicate that both BHMT proteins belong to a family of thiol/selenol methyltransferases (Pfam 02574). Pfam 02574 members contain conserved Hcy and zinc binding motifs. The alignment of BHMT and BHMT-2 presented in Fig. 1 highlight two regions where these proteins significantly differ. First, BHMT contains a region (residues 86–94) that is not found in BHMT-2. Second, the C terminus of BHMT is 43 residues longer than BHMT-2. Both BHMT proteins have sequence segments in their C terminus that are not found in other Pfam 02574 members. These regions have been shown to participate in the oligomerization of BHMT (13, 14).

FIGURE 1.

Alignment of human BHMT and human BHMT-2 amino acid sequences. Identical residues are shaded in black. The accession numbers are human BHMT, NP_001704; and human BHMT-2, NP_060084.

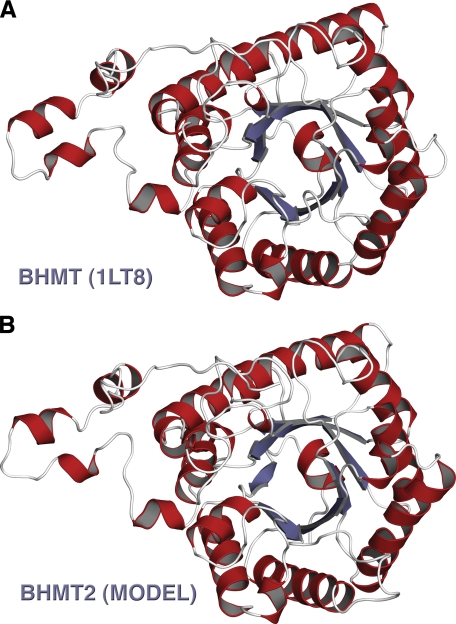

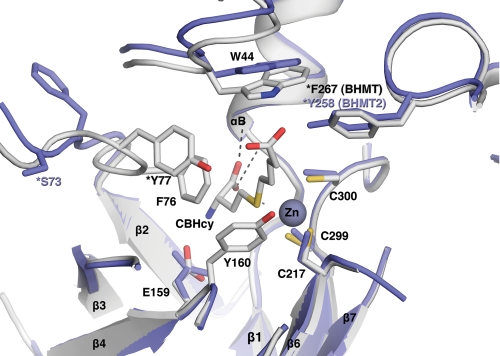

A monomeric theoretical model of human BHMT-2 was generated using Swiss model 3.5 software (Fig. 2). The structures of human BHMT (PDB file 1LT8) (13) and rat liver BHMT (PDB file 1UMY) (15) were used as modeling templates. Like BHMT, the theoretical structure of BHMT-2 is comprised of a (β/α)8 barrel, two loops positioned over the C-terminal ends of the barrel strands, and an extended substructure referred to as a “dimerization” arm for BHMT (13). Key residues involved in BHMT dimerization are conserved in BHMT-2, including Leu264, Glu266, Pro268, Phe269, Val275, Trp279, Arg346, Trp352, Ala358, and Arg361. Residues involved in BHMT tetramerization are also conserved in BHMT-2, including Pro316, Leu321, Gly329, and Ser330. In addition, the BHMT tetramer has a strong ion pair between Lys349 and Glu387 (15), but in BHMT-2 the Lys349 is occupied by Arg350. An examination of the putative BHMT-2 active site reveals three conserved cysteine residues (Cys208, Cys290, and Cys291) that are analogous to residues in BHMT (Cys217, Cys299, and Cys300) that participate in zinc binding (Fig. 3). The BHMT-2 active site also is laced with residues analogous to BHMT residues that participate in substrate binding. Glu159 and backbone residues of αB (Gly27, Phe29, and Val30) are important Hcy binding determinants in BHMT. Similarly, Glu150 is predicted to be at the same position in BHMT-2, although the interactions of the carboxyl moiety of Hcy with the backbone amido and carbonyl groups of Gly27, Phe29, and Leu30 are retained. Residues Trp44, Tyr77, and Tyr160 have been shown to be Bet binding determinants in BHMT (16). The equivalent residues Trp44, Ser77, and Tyr151 are found in or near the active site of BHMT-2. In addition, His338 of one monomer was found to have a role in Bet binding at the active site of the opposite monomer in a BHMT dimer (14). Interestingly, this residue is conserved in BHMT-2. These observations predict, from a sequence and structural perspective, that BHMT-2 is a functional zinc metalloenzyme that performs Hcy methylation and has potential to oligomerize with itself and perhaps with BHMT.

FIGURE 2.

Structural comparison of human BHMT and human BHMT-2. A, monomer from the PDB 1LT8 of human BHMT. B, human BHMT-2 theoretical model generated from Swiss model 3.5, a protein structure homology-modeling server (35). This figure was generated using the PyMOL Molecular Visualization System (DeLano Scientific LLC, Palo Alto, CA).

FIGURE 3.

Structural superposition of the active sites of structure 1LT8 (gray, human BHMT with CBHCy bound) and the model (blue, human BHMT-2). Positions of pertinent residues are indicated. This figure was generated using the PyMOL Molecular Visualization System.

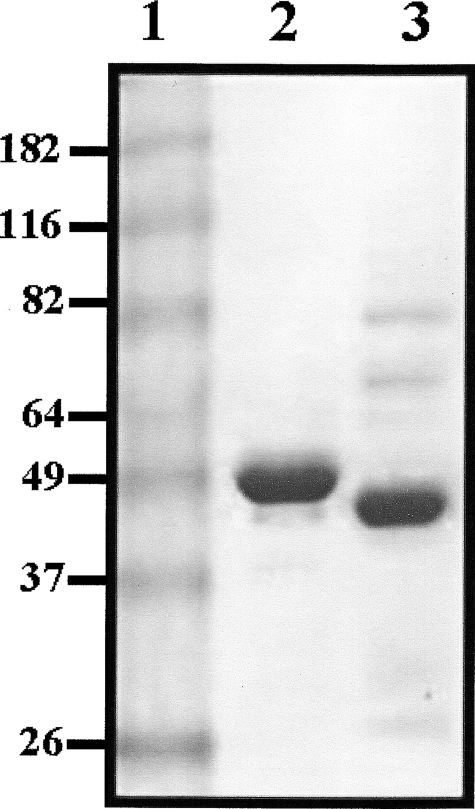

Enzymatic Properties of Purified Human BHMT and Human BHMT-2—SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that recombinant human BHMT and BHMT-2 proteins were at least ∼90% pure, and had molecular masses similar to their predicted sizes of 45 and 40 kDa, respectively (Fig. 4). As expected, BHMT and BHMT-2 preparations were replete with metal, having zinc: monomer ratios of 1.1 and 0.98, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Image of a Coomassie Blue R-250-stained discontinuous 10% SDS-PAGE gel containing 10 μg of recombinant human BHMT and recombinant human BHMT-2. The electrophoretic mobilities of molecular weight standards can be seen in lane 1. Sizes are as indicated and in kilodaltons. Lane 2 contains purified BHMT and lane 3 contains purified BHMT-2.

Early attempts at purifying BHMT-2 resulted in very low yields, and, after identification of its enzyme activity, it was noted to rapidly lose catalytic potential. In contrast, wild type BHMT is very stable, even at low concentrations in buffers without stabilizing agents such as glycerol or ethylene glycol. However, we previously showed that truncating BHMT at the C terminus (deleting residues after Asp371), which reduces the primary sequence of BHMT to match that of BHMT-2, resulted in a protein that did not express well in E. coli (14), presumably due to a destablizing effect on its quaternary structure. It was subsequently determined that concentrating BHMT-2 and storing the enzyme in high concentrations of glycerol (40%, v/v) greatly stabilized its activity, thus allowing further study of its catalytic activity.

The Hcy methylation capacities of BHMT and BHMT-2 were investigated using Bet, SMM, or AdoMet as methyl donors (Table 1). BHMT is active in the presence of Bet or SMM, with the enzyme consuming over 10-fold more Bet than SMM over the duration of 1 h. Surprisingly, BHMT-2 was unable to use Bet, but did have HMT activity with SMM. Although BHMT had no AdoMet-HMT activity, BHMT-2 exhibited some activity with this substrate. The initial rate kinetics of BHMT and BHMT-2 are shown in Table 2. The catalytic efficiency of BHMT toward Bet is 5-fold greater than for SMM, an effect predominantly mediated through kcat. The catalytic efficiency of BHMT-2 with SMM was 5-fold greater than the SMM-dependent activity of BHMT, which is primarily due to the lower Km BHMT-2 has for SMM.

TABLE 1.

Methyl donor specificity of human BHMT and human BHMT-2

Assays (50 μl) contained 2 mm dl-Hcy and 200 μm Bet (0.08 μCi), SMM (0.06 μCi), or AdoMet (0.09 μCi).

| Enzyme | Beta | SMM | AdoMet |

|---|---|---|---|

| BHMT | 501 | 42 | 0.7 |

| BHMT-2 | 0.3 | 280 | 12 |

For Bet-Hcy and AdoMet-Hcy methylation reactions, values are reported as nanomole of Met formed per h per mg of protein. For SMM-Hcy methylation reactions, values reported are nanomole of SMM consumed per h per mg of protein.

TABLE 2.

Kinetic constants (kcat values are per h, and Km values are mm) of human BHMT, human BHMT-2, and mouse liver BHMT-2

|

kcat

|

Km

|

kcat/Km

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bet | SMM | Bet | SMM | Bet | SMM | |

| Human BHMTa | 88 | 24 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 40 | 8 |

| Human BHMT-2b | 38 | 0.94 | 40 | |||

| Mouse BHMT-2c | 0.76 | |||||

Bet kinetic constants were from a previously published report (19).

Assays (50 μl) contained 2 mm dl-Hcy and varying concentrations of SMM (constant radioactivity; 0.27 μCi).

Assays (500 μl) contained 62.5 μm CBHcy, 2.5 mm dl-Hcy, and varying concentrations of SMM (constant radioactivity; 0.5 μCi).

The substrate specificity was further evaluated by measuring the Bet- or SMM-dependent activities in the presence of various unlabeled methyl donors, products, and the bisubstrate BHMT inhibitor CBHcy (16) (Table 3). These compounds will either compete with or inhibit the generation of radiolabeled Met from radiolabeled Bet or SMM. The Bet-dependent activity of BHMT was not altered in the presence of 10-fold excess SMM, and the SMM-dependent activity of BHMT-2 was not changed in the presence of Bet. A 10-fold excess of AdoMet had no effect on BHMT activity, but reduced the SMM-methylation capacity of BHMT-2 by 24%. AdoHcy had no effect on the activity of either protein. DMG, the product of the Bet-mediated methylation of BHMT, at 10-fold excess obliterated apparent BHMT activity but only reduced BHMT-2 activity by 11%. A 10-fold excess of Met, the product of both BHMT and BHMT-2 reactions, reduced apparent BHMT activity by 11% and apparent BHMT-2 activity by 60%. Fifty μm CBHcy eliminated BHMT activity, whereas 500 μm CBHcy only inhibited BHMT-2 activity by 26%. A 10-fold excess of DMSA reduced the apparent BHMT activity by 79% and BHMT-2 activity by 20%. A 10-fold excess of DMSP reduced the apparent BHMT activity by 8% and BHMT-2 activity by 29%. Combined, these results clearly indicate that BHMT and BHMT-2 have functional differences in their methyl donor binding sites.

TABLE 3.

Inhibition of human BHMT and human BHMT-2 activities (relative) by methyl donor substrates, products, and CBHcy

Assays (50 μl) contained 2.0 mm dl-Hcy and 200 μm Bet (0.08 μCi) or SMM (0.06 μCi) for BHMT or BHMT-2 activity determinations, respectively.

| Ligand | [Ligand] | BHMT | BHMT-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm | |||

| Enzyme alone | 100 | 100 | |

| Bet | 0.2 | 102 | |

| 2.0 | 101 | ||

| SMM | 0.2 | 97 | |

| 2.0 | 97 | ||

| AdoMet | 0.2 | 100 | 99 |

| 2.0 | 96 | 76 | |

| DMSA | 0.2 | 71 | 93 |

| 2.0 | 21 | 80 | |

| DMSP | 0.2 | 98 | 90 |

| 2.0 | 92 | 71 | |

| DMG | 0.2 | 20 | 98 |

| 2.0 | 3 | 89 | |

| Met | 0.2 | 98 | 83 |

| 2.0 | 85 | 40 | |

| AdoHcy | 0.2 | 97 | 97 |

| CBHcy | 0.05 | 3 | 99 |

| 0.50 | 0 | 74 |

Characterization of Bet- and SMM-Hcy Methylation Activities in Mouse Tissue Extracts—CBHcy was used to develop an assay that could distinguish between Bet- and SMM-dependent Hcy methylation activities in mouse liver extracts. The assumption was made that, like the human enzymes, the Bet- and SMM-dependent methylation activities of mouse BHMT would be completely inhibited by CBHcy but have little affect on the SMM-dependent activity of BHMT-2. Consistent with this assumption, low concentrations of CBHcy abolished the Bet-dependent activity in mouse liver extract, whereas most of the SMM-dependent activity remained (Table 4). Furthermore, in the presence of CBHcy the Km for mouse BHMT-2 (0.76 mm) in mouse liver was in good agreement with that of purified human BHMT-2 (0.94 mm) (Table 2). An apparent inhibition study was also done on Bet- and SMM-mediated methylation activity in mouse liver extracts. The apparent inhibition patterns of the Bet-Hcy methylation activity of BHMT and the SMM-Hcy methylation activity of BHMT-2 in mouse liver are very similar to the results obtained for human BHMT and BHMT-2 (Table 5 versus Table 3). The BHMT activity in mouse liver was 21-fold greater than that of BHMT-2, whereas these enzyme activities were much lower in the kidney and were present in approximately equal amounts (Table 6). No BHMT-2 activity was detected in the heart, skeletal muscle, spleen, brain, small intestine, or lung (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Dose-dependent inhibition (relative) of Bet- and SMM-dependent Hcy methyltransferase activities by CBHcy in mouse liver extract

Assays (500 μl) contained 2.5 mm dl-Hcy and 250 μm (0.5 μCi) methyl donor.

| Bet-dependent | SMM-dependent | |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme alone | 100 | 100 |

| CBHcy (μm) | ||

| 25 | 1.3 | 78 |

| 62.5 | 0.35 | 64 |

| 125 | 0.18 | 51 |

| 250 | 0.06 | 34 |

| 500 | 0 | 19 |

TABLE 5.

Inhibition of mouse liver BHMT and BHMT-2 activities (relative) by methyl donor substrates and products

Assays (500 μl) contained 2.5 mm dl-Hcy and 250 μm methyl donor (0.5 μCi). BHMT-2 assays were done in the presence of 62.5 μm CBHcy.

| Ligand | [Ligand] | BHMT | BHMT-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| μm | |||

| Enzyme alone | 100 | 100 | |

| Bet | 0.25 | 102 | |

| 2.5 | 96 | ||

| SMM | 0.25 | 97 | |

| 2.5 | 96 | ||

| AdoMet | 0.25 | 97 | 97 |

| 2.5 | 95 | 85 | |

| DMSA | 0.25 | 71 | 99 |

| 2.5 | 18 | 94 | |

| DMSP | 0.25 | 97 | 98 |

| 2.5 | 89 | 83 | |

| DMG | 0.25 | 36 | 97 |

| 2.5 | 5 | 81 | |

| Met | 0.25 | 98 | 91 |

| 2.5 | 62 | 52 |

TABLE 6.

BHMT and BHMT-2 activities in mouse liver and kidney

Assays (500 μl) contained 2.5 mm dl-Hcy and 250 μm methyl donor (0.5 μCi).

| Protein | Activity | BHMT/BHMT-2 ratioa |

|---|---|---|

| Liver BHMT | 79 | |

| Liver BHMT-2 | 3.8 | 20.8 |

| Kidney BHMT | 0.41 | |

| Kidney BHMT-2 | 0.32 | 1.3 |

BHMT-2 assays were done in the presence of 62.5 μm CBHcy. Activities are reported as nanomole of Met formed per hour per mg of protein with an n = 5 for each organ.

DISCUSSION

This report represents the first characterization of enzyme activity associated with BHMT-2. Hitherto, reports on BHMT-2 were restricted to an examination of the expression of human and mouse genes (8, 17) and detection of the protein in rat liver extract by pseudopeptide affinity chromatography (18). We have shown that human BHMT-2 is a zinc metalloenzyme that catalyzes Hcy methylation.

Despite the sequence similarity between BHMT and BHMT-2, no Bet-dependent activity of BHMT-2 could be detected. Rather, BHMT-2 has substantial SMM-HMT activity, and to a lesser extent, AdoMet-HMT activity (Table 1). The lack of inhibition of the SMM-HMT activity of BHMT-2 by Bet and DMG (Tables 3 and 5) supports the conclusion that BHMT-2 does not use Bet to methylate Hcy. We have also determined that BHMT performs SMM-mediated Hcy methylation in vitro. However, the ability of BHMT to use this substrate in vivo is doubtful because SMM did not inhibit BHMT activity when the enzyme was presented with a concentration of SMM that was 10-fold greater than Bet (Tables 3 and 5), the latter of which was well below the Km (19, 20) for this substrate. Bet concentrations in mouse and rat liver are about 500 nmol/g wet weight of organ (21). The SMM concentration in liver is not known and presumably varies depending upon dietary SMM and feeding-fasting cycles, but it is probably reasonable to assume its concentration never exceeds hepatic Bet concentrations unless supplemented. Future work needs to measure SMM in liver and plasma to confirm its potential as a physiological substrate for BHMT-2. Combined, our in vitro data suggest that BHMT can be ascribed all the Bet-dependent activity in vivo, whereas BHMT-2 can most likely be ascribed to all of the SMM-dependent activity.

A previous report indicated that AdoMet does not inhibit BHMT activity (22), which we have verified. Furthermore, Bose et al. (22) could not detect any binding of AdoMet to BHMT using microcalorimetry. In contrast, BHMT-2 displayed low activity using AdoMet as a methyl donor and AdoMet also inhibited the SMM-Hcy methylation activity of BHMT-2. The utilization of BHMT-2 for AdoMet is not surprising because it has a preference for SMM and many Pfam 02574 members, including AtHMT-1 and 2 (23), YagD (24), and Sam4p (25) are known to catalyze AdoMet-mediated Hcy methylation.

BHMT-2 was not inhibited by AdoHcy, a potent inhibitor of most AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases (26). This result could be due to the lack of a positively charged sulfonium moiety. As noted previously, the charge carried by sulfonium or ammonium groups (16) may facilitate the binding of ligands to BHMT enzymes. Furthermore, analysis of BHMT crystal structures (13, 15) do not reveal the presence of the AdoMet-dependent methyltransferase fold found in most AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases (27). Thus, members of Pfam 02574 that catalyze AdoMet-dependent methylations must have a different AdoMet binding mechanism.

BHMT-2 was more potently inhibited by Met than BHMT. Methyltransferases from Arabidopsis, AtHMT-1 and -2, also differ in their sensitivity to Met. AtHMT-1 is strongly inhibited by Met, whereas AtHMT-2 is not (23), and both enzymes use SMM and AdoMet as methyl donors. The authors attribute the difference in Met sensitivities as an important regulatory feature of the plant SMM cycle. Accordingly, BHMT and BHMT-2 may have independent or interactive roles in the regulation of Hcy and Met metabolism in mammals.

We also tested DMSA and DMSP, sulfonium compounds resembling Bet and SMM, respectively, for their ability to bind to BHMT-2. Both DMSA and DMSP have been shown to be methyl donors for Met generation from Hcy in animal tissue homogenates (28) and for purified BHMT (29). Both BHMT and BHMT-2 activities were reduced in the presence of DMSA or DMSP. Together these studies show that BHMT and BHMT-2 can use a variety of sulfonium compounds with different catalytic efficiencies in vitro. It is reasonable to suggest that these enzymes and other members of the Pfam 02574 have divergently evolved from a progenitor zinc and Hcy binding enzyme. Although only BHMT has been crystallized, the theoretical structure of BHMT-2 and the sequence conservation of Pfam 02574 members indicate that all of these enzymes have a similar core structure for zinc and Hcy binding (13). In the structure of BHMT, Bet binding is thought to be mediated by flexible loops L1 and L7 and portions of the dimerization arm (13, 14), which all lie in an open region at the C-terminal ends of β-strands comprising the (β/α)8 barrel that binds zinc and Hcy. The openness and flexibility of the active site in the crystal structure of BHMT probably explains why BHMT enzymes can accommodate a variety of structurally different methyl donors.

Although both BHMT and BHMT-2 appear to have flexible methyl donor binding sites, why can only BHMT use Bet? A major difference between the BHMT and BHMT-2 methyl donor-binding regions is the presence of a nine-amino acid sequence in BHMT (RGNYVLEKI; residues 86–94 in Fig. 1) that is absent in BHMT-2. In the crystal structures of both rat and human BHMT, this region (contained within loop L2 and distal to the active site) is partially disordered (13). Gonzalez et al. (15) noted that a conformational change in an ordered portion of loop L2 occurs upon Hcy binding that orients it toward the active site. Direct evidence that at least a portion of L2 of BHMT undergoes conformational change upon substrate binding was provided by partial trypsin digestion experiments in the presence and absence of CBHcy (30). In the presence of CBHcy, BHMT was resistant to proteolysis, but in the absence of CBHcy the protein was very sensitive to cleavage at L2 residues Arg86 and Lys93. Loop L2 also contains Tyr77, which in the crystal structure of human BHMT complexed with CBHcy is clearly involved in binding the carboxylate anion of the carboxybutyl Bet mimic (13). Tyr77 also seems to have a role in Hcy recognition and/or triggering key conformational changes during catalysis. The Y77A rat BHMT mutant has been reported to have only 7% of wild type activity (31), whereas the Y77F human BHMT mutant had no activity and was shown by intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence to be either unable to bind Hcy or induce the normal conformational changes observed subsequent to its binding (16). In addition, the human BHMT Y77F mutant had a Kd for CBHcy that was 100-fold greater than the wild type enzyme. In BHMT-2 this position is occupied by Ser77 (Fig. 3), which seems too distant to interact with the carboxyl moiety of a substrate like Bet. However, this residue could potentially have a role in facilitating binding and/or catalysis of SMM-dependent HMT activity of BHMT-2. Thus, Tyr77 and the nine additional amino acid residues in the N terminus BHMT, all of which are in a flexible region of L2 and are lacking in BHMT-2, most likely confer to BHMT its unique ability to use Bet as a methyl donor. Indeed, we found that a deletion mutant of BHMT (Δ86–96) that removed residues 86–94 was void of activity using Bet at the methyl donor, suggesting that this region is important for substrate recognition (data not shown). The structural comparison of the active sites of BHMT and BHMT-2 outlined here could explain why BHMT-2 cannot bind and therefore use Bet as a substrate (Tables 1 and 3), and why CBHcy has much lower affinity for BHMT-2 compared with BHMT (Tables 3 and 4).

Another interesting difference between the methyl donor binding sites of BHMT and BHMT-2 are the equivalent locations of Phe267 in BHMT and Tyr258 in BHMT-2 (Fig. 3). Although Phe267 does not appear to have a direct role in binding Bet in BHMT, it could be that the additional hydroxyl group on Tyr258 in BHMT-2 could have a role in SMM binding, a possibility that warrants further study.

BHMT, as opposed to other characterized members of the Pfam 02574 family, is an oligomeric protein and we previously showed that oligomerization is essential for catalysis (14). In this prior report we showed by sequence alignment that regions of the BHMT protein involved in oligomerization were not evident in other Pfam 02574 members that are known to be monomeric. For instance, one of these regions forms the “dimerization arm” (residues 319–353) of BHMT. The dimerization arm sequence and the presence of an ordered arm structure in the theoretical model of BHMT-2 are evident. Thus, the addition of these oligomerization regions in the BHMT proteins suggests further evolutionary divergence from a zinc and Hcy binding progenitor. Speculatively, it may be possible for BHMT and BHMT-2 to hetero-oligomerize.

In summary, we demonstrate that BHMT-2 is an SMM-Hcy methyltransferase. SMM, a component of plant foods, has been shown to have dietary choline sparing activity in chickens (32), and Met sparing activity in rats (33, 34). Because Met can be a limiting amino acid for animal growth and development, it is possible that retaining the ability to use dietary SMM as a Met precursor and one carbon donor (via BHMT-2) offered a competitive advantage throughout evolution. Furthermore, Shapiro and Yphantis (4) found that rat liver extracts contained low AdoMet-Hcy methylation activity, and our in vitro work with BHMT-2 shows that it can methylate Hcy using AdoMet, albeit poorly. It is possible, therefore, that BHMT-2 may have some AdoMet-HMT activity in vivo.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK52501 (to T. A. G.) and GM48533 (to M. L. Ludwig and J. L. Smith), and Illinois Agricultural Experiment Station Project ILLU-698-352. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: Hcy, homocysteine; BHMT, betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase; BHMT-2, betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase-2; CBHcy, S-(δ-carboxybutyl)-l-homocysteine; DMG, dimethylglycine; DMSP, dimethylsulfoniopropionate; AdoMet, S-adenosylmethionine; AdoHcy, S-adenosylhomocysteine; SMM, S-methylmethionine; HMT, Hcy methyltransferase; DMSA, dimethylsulfonioacetate.

References

- 1.Finkelstein, J. D., Harris, B. J., and Kyle, W. E. (1972) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 153 320–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelstein, J. D., and Martin, J. J. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259 9508–9513 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrow, T. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 22831–22838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro, S. K., and Yphantis, D. A. (1959) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 36 241–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim, G. (2003) Food Sci. Tech. Res. 9 316–319 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanson, A. D., Rivoal, J., Paquet, L., and Gage, D. A. (1994) Plant Physiol. 105 103–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunau, J. M. (1991) Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 22 1873–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chadwick, L. H., McCandless, S. E., Silverman, G. L., Schwartz, S., Westaway, D., and Nadeau, J. H. (2000) Genomics 70 66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breksa, A. P., 3rd, and Garrow, T. A. (1999) Biochemistry 38 13991–13998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lavine, T. F., Floyd, N. F., and Cammaroti, M. S. (1954) J. Biol. Chem. 207 107–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awad, W. M., Jr., Whitney, P. L., Skiba, W. E., Mangum, J. H., and Wells, M. S. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258 12790–12792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holcomb, E. R., and Shapiro, S. K. (1975) J. Bacteriol. 121 267–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans, J. C., Huddler, D. P., Jiracek, J., Castro, C., Millian, N. S., Garrow, T. A., and Ludwig, M. L. (2002) Structure 10 1159–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szegedi, S. S., and Garrow, T. A. (2004) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 426 32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez, B., Pajares, M. A., Martinez-Ripoll, M., Blundell, T. L., and Sanz-Aparicio, J. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 338 771–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro, C., Gratson, A. A., Evans, J. C., Jiracek, J., Collinsova, M., Ludwig, M. L., and Garrow, T. A. (2004) Biochemistry 43 5341–5351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steele, W., Allegrucci, C., Singh, R., Lucas, E., Priddle, H., Denning, C., Sinclair, K., and Young, L. (2005) Reprod. Biomed. Online 10 755–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collinsova, M., Castro, C., Garrow, T. A., Yiotakis, A., Dive, V., and Jiracek, J. (2003) Chem. Biol. 10 113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Millian, N. S., and Garrow, T. A. (1998) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 356 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakajima, K. (2006) J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 52 61–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koc, H., Mar, M. H., Ranasinghe, A., Swenberg, J. A., and Zeisel, S. H. (2002) Anal. Chem. 74 4734–4740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bose, N., Greenspan, P., and Momany, C. (2002) Protein Expression Purif. 25 73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranocha, P., Bourgis, F., Ziemak, M. J., Rhodes, D., Gage, D. A., and Hanson, A. D. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 15962–15968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhierl, B., Thanbichler, M., Lottspeich, F., and Bock, A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 5407–5414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas, D., Becker, A., and Surdin-Kerjan, Y. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 40718–40724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulrey, C. L., Liu, L., Andrews, L. G., and Tollefsbol, T. O. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14 R139–R147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin, J. L., and McMillan, F. M. (2002) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12 783–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dubnoff, J. W., and Borsook, H. (1948) J. Biol. Chem. 176 789–796 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ericson, L. E. (1960) Acta Chem. Scand. 14 2127–2134 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, C. M., Szegedi, S. S., and Garrow, T. A. (2005) Biochem. J. 392 443–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez, B., Campillo, N., Garrido, F., Gasset, M., Sanz-Aparicio, J., and Pajares, M. A. (2003) Biochem. J. 370 945–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Augspurger, N. R., Scherer, C. S., Garrow, T. A., and Baker, D. H. (2005) J. Nutr. 135 1712–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegedus, M., Fekete, S., Andrasofszky, E., Tamas, J., and Kovari, L. (1992) Acta Vet. Hung. 40 145–150 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsuo, T., Seri, K., and Kato, T. (1980) Arzneim.-Forsch. 30 68–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwede, T., Kopp, J., Guex, N., and Peitsch, M. C. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3381–3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]