Abstract

Background

Walking is a complex act that requires the coordination of locomotor, cardiovascular, and autonomic systems. Aging affects each of these systems and may alter physiological mechanisms regulating the interactions between them.

Methods

We examined the effects of healthy aging on cardiac–locomotor coupling using treadmill walking at incremental speeds from 0.8 mph to normal walking speed in 12 healthy young (29.0 ± 5.0 years) and 9 healthy elderly persons (70.3 ± 5.1 years). interbeat (R-R) intervals, step intervals, maximum foot pressure (MFP) and normalized maximum force, blood pressure (BP), and blood flow velocity (BFV) in the middle cerebral artery were continuously measured.

Results

Step intervals and R-R intervals decreased, and MFP and BFV increased with walking speed in both groups; systolic BP increased (p < .0001) in the old group. In elderly, but not in young participants, step intervals and R-R intervals were coupled (R2 = 0.84, p < .0001), and MFP was correlated with systolic BP (R2 = 0.51, p < .02).

Conclusion

Cardiolocomotor coupling that becomes manifest with aging may optimize cardiovascular responses during walking. In elderly people, forces generated during the gait cycle may be transmitted to arterial pressure and thus synchronize the central cardiovascular network with the stepping rhythm.

Biological cycles can be entrained by internal rhythmic phenomena, as well as by external periodic inputs. Coupling between locomotor, respiratory, and cardiac rhythms has been reported in humans during walking and running (1–3) and has been modeled in animals (4,5). Complex physiological mechanisms coordinate interactions among the locomotor and cardiovascular systems during walking. Locomotor circuits generating patterns and timing of the gait cycle interact with brainstem cardiorespiratory networks (6). These networks synchronize vagally mediated fluctuations in cardiac cycle with respiration (7) and regulate interactions with sympathetically mediated fluctuations in blood pressure (BP) through the baroreflexes (8). Changes in muscle force and blood flow during the gait cycle provide periodic inputs to the cardiovascular system (1). The peripheral concept of cardiac–locomotor coupling was based on the phase dependency between active muscle contraction and cardiac cycle (3,9). Central entrainment from locomotor to respiratory to cardiac cycles was demonstrated during stimulation of the locomotor mesencephalic area in decerebrated vagotomized cats (4).

The dynamics of cardiac and locomotor rhythms are altered by aging and are sensitive predictors of age-related disorders (10). Synchronization of cardiac and locomotor rhythms may have physiological significance by optimizing cardiovascular performance and perfusion of exercising muscle during rhythmic exercise (1). Walking speed is an indicator of functional status (11,12) in elderly people, and slow walking has been prospectively associated with poor outcome, altered cerebral blood flow regulation, and cognitive decline (13,14).

We hypothesized that aging affects the dynamic interactions between locomotor and cardiovascular systems and cerebral blood flow. Therefore, we studied cardiac–locomotor coupling during walking at incremental treadmill speeds up to normal walking speed (NWS) in healthy young and elderly people.

METHODS

Participants

The study was performed in the Syncope and Falls in the Elderly Laboratory at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. All participants provided written informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1; 12 healthy young persons (29.0 ± 5.0 years) and 9 healthy elderly persons (70.3 ± 5.1 years) were studied. All participants were screened by using a detailed medical history, physical activity questionnaires, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram. They were not receiving treatment for any systemic disease, had no medical history of recurrent falls and foot injuries, and were normotensive by medical history, confirmed by measurements of sitting and standing BP.

Table 1.

Demographic, Cardiovascular, and Gait Characteristics of the Young and Elderly Groups

| Variables | Young | Old | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.0 ± 5.1 (22–39) | 70.3 ± 5.1 (63–78) | < .0001 |

| Men/Women | 5/7 | 5/4 | |

| Weight, kg | 67.9 ± 20.8 | 68.7 ± 12.6 | .92 |

| Height, cm | 171.0 ± 12.0 | 166.0 ± 10.4 | .31 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.8 ± 4.0 | 24.8 ± 3.0 | .23 |

| Sitting heart rate, bpm | 71.2 ± 12.2 | 69.7 ± 10.3 | .78 |

| Sitting systolic/diastolic BP, mmHg | 114 ± 10/68.1 ± 7.1 | 120 ± 16/66.4 ± 8.9 | .33/.65 |

| Sitting mean BFV, cm/s | 66.8 ± 12.3 | 53.4 ± 14.4 | .03 |

| Standing heart rate, bpm | 80.2 ± 13.7 | 74.3 ± 10.1 | .29 |

| Standing systolic/diastolic BP, mmHg | 116.0 ± 9.0/70.2 ± 7.2 | 121 ± 20/67.9 ± 9.4 | .39/.52 |

| Standing mean BFV, cm/s | 63.0 ± 9.8 | 51.2 ± 14.3 | .04 |

| Standing Rate Perceived Exertion | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | .002 |

| NWS heart rate, bpm | 91.8 ± 13.1 | 95.6 ± 20.3 | .61 |

| NWS systolic/diastolic BP, mmHg | 125.9 ± 3.9/66.9 ± 7.5 | 151 ± 13/66.9 ± 14.3 | .03/.99 |

| NWS mean BFV, cm/s | 73.8 ± 11.5 | 59.2 ± 13.7 | .02 |

| NWS Rate Perceived Exertion | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 1.3 | .005 |

| ΔRate Perceived Exertion standing–NWS | 0.25 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | .36 |

| NWS, mph | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | .31 |

| Step interval, ms | 543.2 ± 85.5 | 512.6 ± 55.3 | .36 |

| Stride, ms | 1012.6 ± 121.6 | 1096.5 ± 167.8 | .24 |

| Swing, ms | 423.1 ± 45.6 | 463.3 ± 70.7 | .17 |

| Stance, ms | 589.5 ± 79.1 | 633.2 ± 99.3 | .31 |

Notes: Mean ± standard deviation.

p = group comparisons.

NWS = normal walking speed; BP = blood pressure; BFV = blood flow velocity.

Study Protocol

Self-paced NWS was determined with a 12-minute corridor walk. Participants sat in a chair for 3 minutes and then stood up for 5 minutes. The treadmill speed started at 0.8 mph that was increased by 0.2 mph every 30 seconds until NWS, and then was maintained at NWS for 6 minutes. We examined walking speeds up to NWS, rather than beyond, to minimize any potential effects of cardiovascular stress above that experienced during normal walking. The 10-point Borg Rating Perceived Exertion scale was used to rate exertion after 5 minutes standing and at the end of NWS walking (15).

Data Acquisition, Processing, and Analysis

The electrocardiogram was measured from a modified lead II or III (SpaceLab Medical Inc., Issaquah, WA). Beat-to-beat BP was recorded from a finger with a Finapres device (Ohmeda Monitoring Systems, Englewood, CO) and verified by arterial tonometry. With finger position at the heart level and temperature kept constant, the Finapres device can reliably track intra-arterial BP changes (16). Respiratory parameters were measured using an infrared end tidal volume monitor (Datex Ohmeda, Madison, WI). The right middle cerebral artery was insonated using the 2 MHz probe of a transcranial Doppler ultrasonography system (Multi-Dop X4; DWL Neuroscan Inc., Sterling, VA). The probe was positioned to record the maximal blood flow velocity (BFV) and stabilized using a three-dimensional holder. The middle cerebral artery diameter remains relatively constant under physiological conditions; therefore, BFV can be used to estimate blood flow (17).

Foot pressure distribution was continuously measured using shoe insoles with 99 capacitive sensors, connected to a portable Pedar Mobile device that acquired pressures for each sensor at 50 Hz (Novel Electronics, Munich, Germany) (18). Maximum foot pressure (MFP) reflects the combined effects of weight, anatomical foot structure, and ground impact force during walking (19,20). MFP corresponds to the maximal plantar pressure during the step (21). Treadmill use ensured a consistent speed, as stride variability may affect plantar pressures and forces during normal walking (19). To calculate maximum forces, the pressure time-series data were converted to force by multiplying each pressure value by the cross-sectional area of the corresponding sensor. MFP and forces were averaged for each step and normalized for body weight. Maximum force was also calculated over a time frame corresponding to interbeat (R-R) intervals and normalized for body weight (normalized maximum force within the interbeat R-R interval [NMFRRI]) unrelated to the phase of gait cycle.

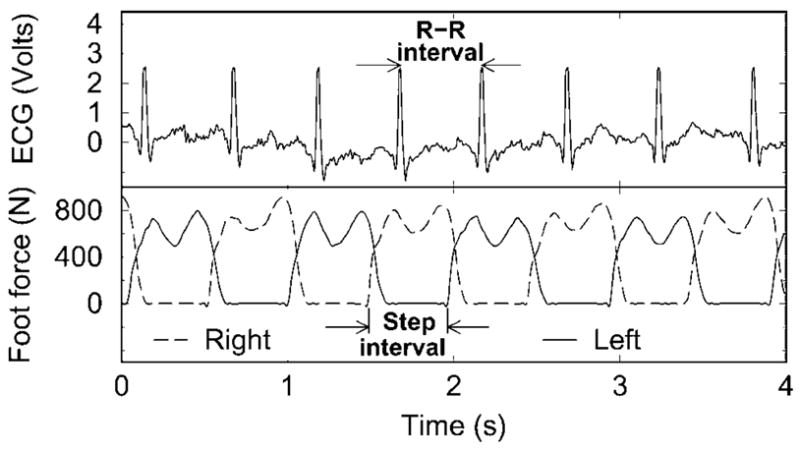

Foot force, electrocardiogram, BP, and BFV analog signals were continuously acquired at 1000 Hz using Lab-VIEW 6.0, NI-DAQ (National Instruments, Inc., Austin, TX). R-R intervals, systolic and diastolic BP, and BFV values were detected beat-to-beat from original time series. Step intervals (right heel touch to left heel touch) and strides (same foot heel-to-heel touch) were detected for each foot. Continuous step interval time series were constructed from consecutive right and left steps from the maximum force signals (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and maximum force signals for the right and left foot, step interval, and interbeat (R-R) intervals.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize physiological variables for all test conditions. The coefficients of correlation and determination (R2) were calculated to evaluate the relationship between step intervals, beat-to-beat R-R intervals, and 30-second averages corresponding to the 0.2-mph increments of the treadmill speed over a linear portion of the signals for treadmill speeds from 0.8 mph to NWS. The standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation were calculated for each speed. The effects of young versus old groups and treadmill speeds on physiological variables were analyzed with multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA). Standard least square models were applied to analyze the relationship between R-R intervals and step intervals, NMFRRI, MFP, and systolic BP, adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, and individual walking speed. Mean and nonparametric variables were compared with one-way ANOVA and the Wilcoxon test. Physiological data are presented for treadmill speeds 0.8–2.4 mph, as the NWS ≥ 2.4 mph in most participants.

RESULTS

Demographic and physiological data during sitting, standing, and treadmill walking at NWS are summarized in Table 1. Heart rate and its increment between sitting and NWS were not different between the groups. BP during sitting and standing was not different between the groups, but systolic BP at NWS (p = .03) was higher in the old group. Mean BFV values were lower in the old participants during sitting (p < .03), standing (p < .04), and at NWS (p = .02). In the old group, the perceived exertion was similar between standing and NWS walking, but was greater than in the young group after standing (p < .002) and NWS walking (p < .005). Gait characteristics were not different between the groups.

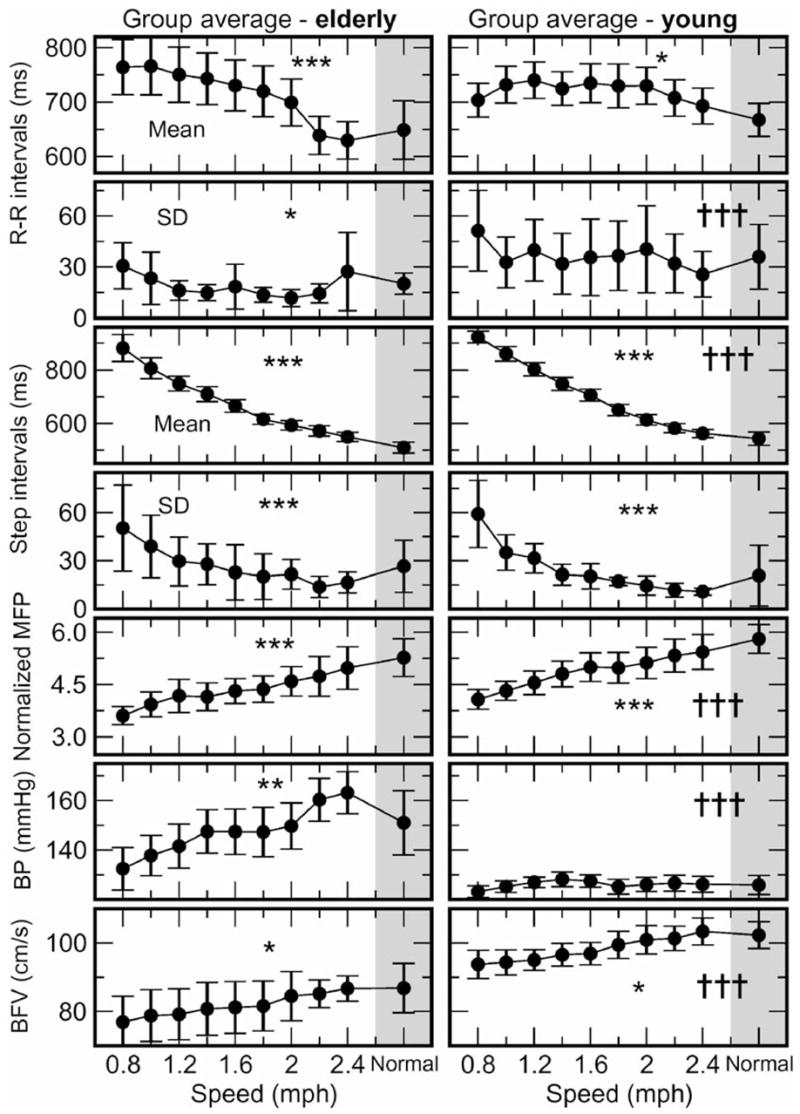

Walking at incremental speeds had significant effects on gait and cardiovascular variables. Figure 2 shows the profile of average R-R intervals, R-R interval SD, step intervals, step interval SD, normalized MFP, systolic BP, and mean BFV for treadmill speeds from 0.8 mph to 2.4 mph, and at NWS. In both groups R-R intervals decreased with speed (old: p < .0001; young: p < .02), but were not different between groups. R-R intervals were associated with speed (p < .001), body mass (p = .005), and sex (p = .02), but not with the group. In contrast, R-R interval variability (SD p < .0001) and coefficient of variation p < .0001) were lower in the old participants for all walking speeds.

Figure 2.

The 30-second averages of interbeat (R-R) intervals, standard deviation (SD) of R-R intervals, step intervals, SD of step intervals, normalized maximum foot pressure (MFP), systolic blood pressure (BP), and mean blood flow velocity (BFV) during treadmill walking from 0.8 mph to 2.4 mph and at normal walking speed (NWS) (gray shading) for the young and the elderly groups (mean ± standard error). The effect of speed in each group ***p < .0001, **p < .003, *p < .03 and the effect of group across all speeds †††p < .0001, ††p < .003.

In both groups, step intervals decreased (p < .0001) and normalized MFP increased with treadmill speed (p < .0001). Step intervals at each walking speed and at NWS were not different between the groups, but there was an overall effect of group (p < .0001), body mass (p < .0003), and sex (p < .0001) on step intervals. Step interval variability (SD and coefficient of variation) diminished during walking (p < .0001) but was not different between groups for any speed. Normalized MFP (p < .0001), maximum force (p < .0001), and mean foot pressure (p < .0001) were lower in the old group at all speeds. Normalized MFP increased with speed in both young and old groups (p < .0001). Systolic BP increased with speed in the old group (p = .002), and was higher than in the young group (p < .0001), in which BP remained stable. In addition, systolic BP variability was greater in old participants (p < .004). Diastolic and mean BP were not different. Cerebral BFV values were higher during treadmill walking and at NWS compared to sitting and standing. During walking, systolic (p = .01), diastolic (p = .04), and mean BFV values (p = .01) increased in the old group, and systolic (p = .0004) and mean BFV values (p = .01) increased in the young group. BFV values remained lower in the old group (p = .0001) at all speeds. Notably, although R-R intervals were not different between groups at any speed, the R-R interval variability was reduced and systolic BP variability was increased in the old group. Step intervals decreased with speed in both groups and step interval variability was not different.

Relationship Between Step Intervals and R-R Intervals

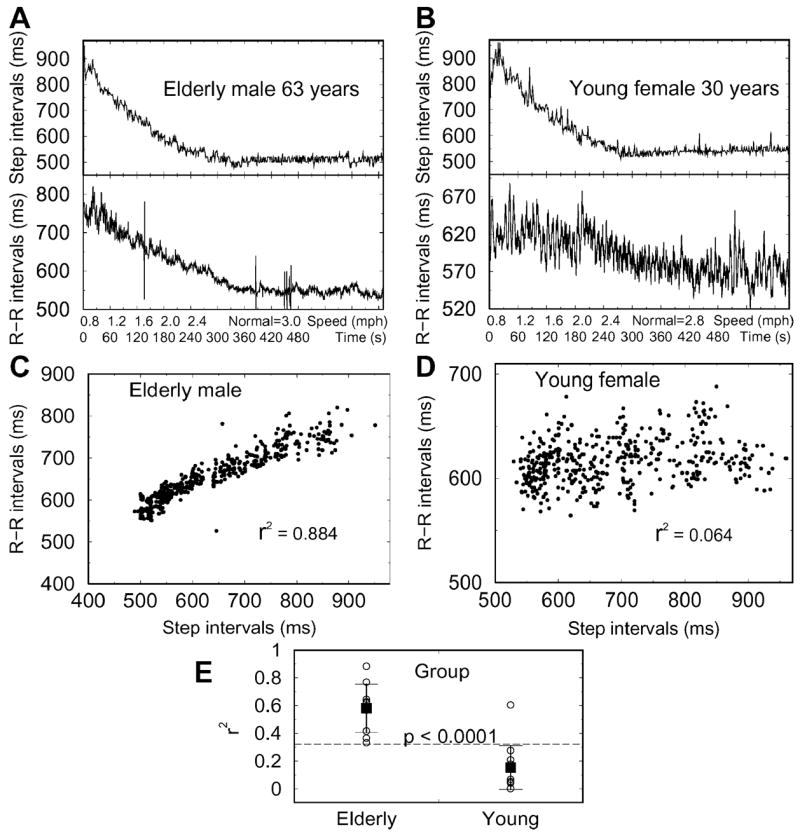

Figure 3 shows step intervals and beat-to-beat R-R intervals for a healthy elderly (A) and a young participant (B) for treadmill walking from 0.8 mph until NWS. Correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between step intervals and beat-to-beat R-R intervals in the old (C) but not in the young participant (D). The coefficients of determination (R2) were greater in the old group than in the young group (R2 = 0.58 ± 0.18 vs 0.15 ± 0.16, p < .0001) (E). The relationship between step intervals and R-R intervals was stronger in the old versus the young group (R2 = 0.84 ± 0.06 vs 0.41 ± 0.06, p < .0001) for coefficients of determination calculated from 30-second averages of these data shown. The coefficients of determination were associated with age (p =.006), but not with sex, body mass index, NWS, or the rate of perceived exertion between beginning and end of walking. In the old group, coefficients of correlation and determination between normalized MFP (averaged for the right and left foot) and systolic BP were significant compared to the young group (MFP average: R = 0.66 ± 0.28 vs 0.19 ± 0.45, p < .01; R2 = 0.51 ± 0.31 vs 0.22 ± 0.21, p < .02).

Figure 3.

Step intervals and interbeat (R-R) intervals for treadmill speeds to normal walking speed for an old (A) and young participant (B). Each point corresponds to a step interval and corresponding R-R interval for all walking speeds. Correlation analysis revealed a significant relationship between step intervals and beat-to-beat R-R intervals for the old (C) but not for the young participant (D). The coefficients of determination (R2) were higher (E) in the elderly compared to the young group.

We applied the standard least square models to examine the relationship between R-R intervals and systolic BP, normalized foot force corresponding to R-R intervals (NMFRRI), and normalized MFP for each step. To adjust for the possible effects of age, body mass index, sex, and NWS of individuals, we used model residuals of linear least-square fittings of each variable and these four parameters. We found in both young and old groups that R-R intervals are associated with larger normalized force NMFRRI (p < .0001). In the old group, R-R intervals were also positively correlated with step intervals (p =.0004), and negatively correlated to systolic BP (p < .0001), whereas normalized MFP had no significant effect (p = .16) (R2 = 0.64). In contrast, R-R intervals of the young group did not show dependence on step intervals (p = .26) and systolic BP (p = .08), but they were strongly associated with normalized MFP (p < .0001) (R2 = 0.64).

DISCUSSION

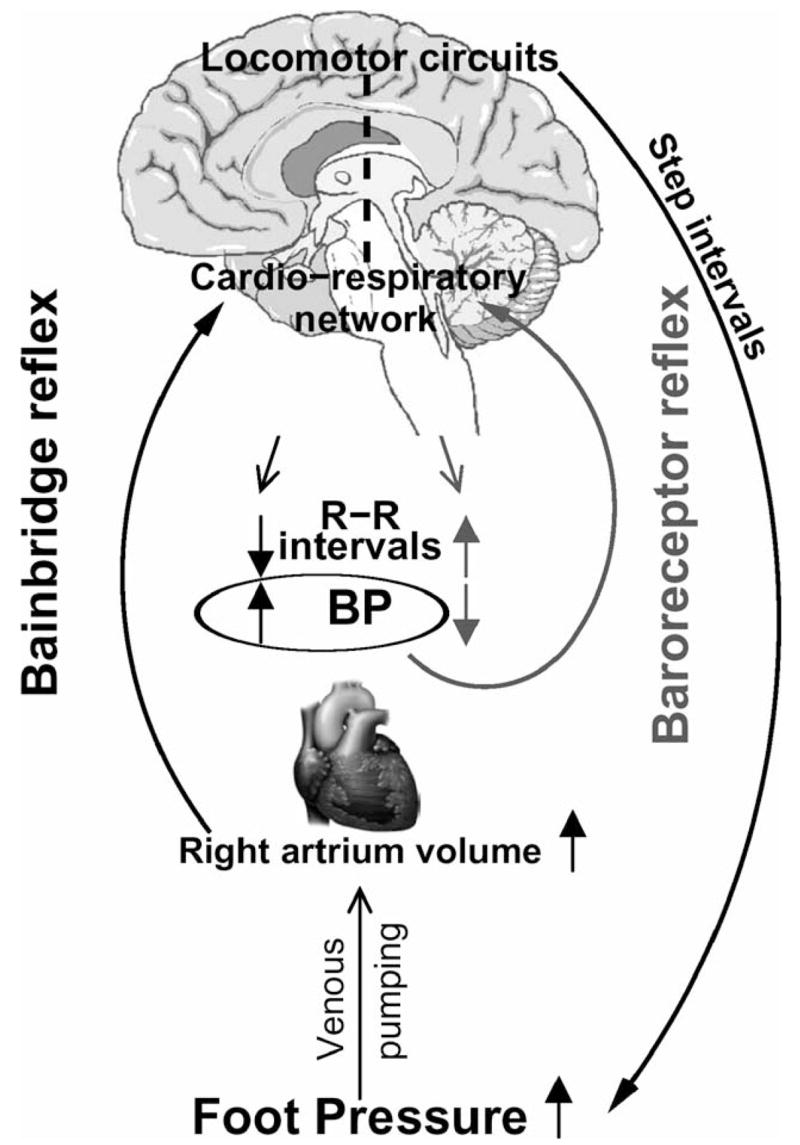

This study has identified significant cardiac–locomotor coupling in elderly people during treadmill walking from 0.8 mph to NWS that was not apparent in young participants. The coupling between R-R and step intervals was associated with age, but not with sex, body mass index, NWS, or rate of perceived exertion during walking. In old participants, R-R intervals during treadmill walking were positively associated with normalized maximum force and step intervals, and negatively with systolic BP. The cardiac–locomotor entrainment may become enhanced in elderly people, as the cardiac–respiratory fluctuations and vagally mediated baroreflexes become attenuated with aging. Therefore, we hypothesized that forces generated by muscle contraction during walking may act as a pump, rhythmically propelling venous blood to the right atrium with a step-synchronized rhythm (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Conceptual model of cardiac–locomotor coupling during walking. Stepping rhythm that is generated in locomotor circuits is transferred to interbeat (R-R) intervals through the effects of muscle pump on venous return and cardiac reflexes. Beat-to-beat systolic blood pressure (BP) fluctuations are dampened by baroreflexes.

These intermittent increases in venous return may activate cardiopulmonary stretch reflexes through atrial distension and increased cardiac volume. Beat-to-beat increases in systolic BP are dampened by the baroreflexes, leading to R-R interval prolongation and increased R-R interval variability (10,22). The activation of stretch reflexes (e.g., Bain-bridge reflex) would increase systolic BP and shorten R-R intervals in response to volume loading (23). Thus the rhythmical stimulation of cardiac reflexes, activated by the increases in the cardiac volume generated with each step, may synchronize the cardiac cycle with the stepping rhythm. Niizeki and colleagues (2) also observed that episodes of cardiac–locomotor coupling at treadmill speeds from 2.6 to 5.5 mph were associated with blunted R-R interval variability. With attenuation of autonomic feedback mechanisms with aging, the muscle forces generated during the gait cycle may exert a greater impact on cardiac cycle.

Cardiac–locomotor synchronization was more frequent and longer lasting during running compared to cycling (3), even if the metabolic demands and heart rate were matched in both exercises. Synchronization between the muscle contraction and the systolic phase of the cardiac cycle had a tendency to shorten R-R intervals, suggesting afferent signaling from active muscle to cardiovascular centers (9). Furthermore, cardiac entrainment can be achieved by rhythmical increases of intramuscular pressure at the resting heart beat frequency using periodic thigh-cuff occlusions above systolic BP without increasing cardiovascular load (24). Therefore, periodic increases of muscle pressure and venous return during walking may play a significant role in cardiac–locomotor coupling. The above findings support the notion that the differences in aerobic capacity between young and old persons may not be the primary mechanism for enhancement of cardiolocomotor coupling in elderly people. Cerebral flow velocity was lower in the elderly participants during sitting and standing up, but increased during walking. In elderly participants, maintenance of cerebral perfusion improved with increasing speed up to NWS. These findings indicate that moderate activity may have beneficial effects on cerebral perfusion in old people.

Complex fluctuations modulating the gait cycle, beat-to-beat heart rate, and BP reflect interactions between central oscillatory networks and peripheral inputs. These nonlinear relationships among multiple variables are difficult to evaluate using standard techniques. Stepwise increase of treadmill speed enabled us to evaluate cardiolocomotor entrainment over a linear scale of walking frequencies and to examine age-related differences in cardiolocomotor interactions using time-domain methods. The complexity of neural networks and feedback loops responsible for the integration of multiple physiological responses to everyday activities declines with age (10). As the influence of baroreflexes on beat-to-beat heart rate modulation diminishes with aging, relative contributions of muscle activity and sympathetic vasomotor responses prevail. Consequently, the peripheral forces generated during walking may optimize cardiovascular adaptation during physiological stress. These adaptive processes may be beneficial by providing effective feedback necessary to enhance cardiovascular performance and to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion during walking. This study demonstrated that coupling between cardiac and locomotor rhythms during normal walking is enhanced in the aged population. Walking at normal speed may have beneficial effects on cardiovascular performance and cerebral perfusion in elderly people.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Older American Independence Center Grant 2P60 AG08812-11 and by Research Nursing Home Program Project Grant AG004390 and General Clinical Research Center Grant MO1-RR01032 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. Dr. Lipsitz holds the Irving and Edyth S. Usen and Family Chair in Geriatric Medicine at Hebrew SeniorLife.

References

- 1.Kirby RL, MacLeod DA, Marble AE. Coupling between cardiac and locomotor rhythms: the phase lag between heart beats and pedal thrusts. Angiology. 1989;40:620–625. doi: 10.1177/000331978904000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niizeki K, Kawahara K, Miamoto Y. Interaction among cardiac, respiratory and locomotor rhythms during cardiolocomotor synchronization. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:1815–1821. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.4.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura K, Takei Y, Yanagida Y. Comparison of cardiolocomotor synchronization during running and cycling. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0784-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawahara K, Yoshioka T, Yamauchi Y, Niizeki K. Heart beat fluctuation during fictive locomotion in decerebrate cats: locomotor-cardiac coupling of central origin. Neurosci Lett. 1993;150:200–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90535-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons AD, Carrier DR, Farmer CG, Gregersen CS. Lack of locomotor-cardiac coupling in trotting dogs. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R1352–R1360. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.4.R1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guadagnoli MA, Etnyre B, Rodrique ML. A test of a dual central pattern generator hypothesis for subcortical control of locomotion. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2000;10:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s1050-6411(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novak V, Novak P, de Champlain J, Le Blanc AR, Martin R, Nadeau R. Influence of respiration on heart rate and blood pressure fluctuations. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:617–626. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.2.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benarroch EE. Central autonomic network. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;68:988–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niizeki K, Miamoto Y. Phase-dependent heartbeat modulation by muscle contractions during dynamic handgrip in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H1331–H1338. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipsitz LA. Dynamics of stability: the physiological basis of functional health and frailty. J Gerontol Biol Sci. 2002;57A:B115–B125. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.3.b115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brach JS, FitzGerald S, Newman AB, et al. Physical activity and functional status in community-dwelling older women: a 14-year prospective study. Arch Int Med. 2003;163:2565–2571. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.21.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gulati M, Black HR, Shaw LJ, et al. The prognostic value of a nomogram for exercise capacity in women. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:468–475. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Beckett LA, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Progression of gait disorder and rigidity and risk of death in older persons. Neurology. 2002;58:1815–1819. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Kuslansky G, Katz MJ, Buschke H. Abnormality of gait as a predictor of non-Alzheimer’s dementia. N Engl J Med. 2002;28:1761–1768. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borg G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scand J Rehab Med. 1970;2:92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novak V, Novak P, Schondorf R. Accuracy of beat-to-beat noninvasive measurement of finger arterial pressure using the Finapres: a spectral analysis approach. J Clin Monit. 1994;10:118–126. doi: 10.1007/BF02886824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serrador JM, Picot PA, Rutt BK, Shoemaker JK, Bondar RL. MRI measures of middle cerebral artery diameter on conscious humans during simulated orthostasis. Stroke. 2000;31:1672–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weijers RE, Walenkamp GH, van Mameren H, Kessels AG. The relationship of the position of the metatarsal heads and peak plantar pressure. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:349–353. doi: 10.1177/107110070302400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavanagh PR, Morag E, Boulton AJ, Young MJ, Deffner KT, Pammer SE. The relationship of static foot structure to dynamic foot function. J Biomech. 1997;30:243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bus SA. Ground reaction forces and kinematics in distance running in older-aged men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1167–1175. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074441.55707.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hessert MJ, Vyas M, Leach J, Hu K, Lipsitz L, Novak V. Foot pressure distribution during walking in young and old. BMC Geriatr. 2005;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyengar N, Peng CK, Morin R, Goldberger AL, Lipsitz LA. Age-related alterations in the fractal scaling of cardiac interbeat interval dynamics. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R1078–R1084. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.4.R1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbieri R, Triedman JK, Saul JP. Heart rate control and mechanical cardiopulmonary coupling to assess central volume: a systems analysis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R1210–R1220. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00127.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niizeki K. Intramuscular pressure-induced inhibition of cardiac contraction: implications for cardiac-locomotor synchronization. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R645–R650. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00491.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]