Abstract

Feline defensive rage, a form of aggressive behavior that occurs in response to a threat can be elicited by electrical stimulation of the medial hypothalamus or midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG). Our laboratory has recently begun a systematic examination of the role of cytokines in the regulation of rage and aggressive behavior. It was shown that the cytokine, interleukin-2 (IL-2), differentially modulates defensive rage when microinjected into the medial hypothalamus and PAG by acting through separate neurotransmitter systems. The present study sought to determine whether a similar relationship exists with respect to interleukin 1-β (IL-1β), whose receptor activation in the medial hypothalamus potentiates defensive rage. Thus, the present study identified the effects of administration of IL-1β into the PAG upon defensive rage elicited from the medial hypothalamus. Microinjections of IL-1β into the dorsal PAG significantly facilitated defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus in a dose and time dependent manner. In addition, the facilitative effects of IL-1β were blocked by pre-treatment with anti-IL-1β receptor antibody, while IL-1β administration into the PAG had no effect upon predatory attack elicited from the lateral hypothalamus. The findings further demonstrated that IL-1β’s effects were mediated through 5-HT2 receptors since pretreatment with a 5-HT2C receptor antagonist blocked the facilitating effects of IL-1β. An extensive pattern of labeling of IL-1β and 5-HT2C in the dorsal PAG supported these findings. The present study demonstrates that IL-1β in the dorsal PAG, similar to the medial hypothalamus, potentiates defensive rage behavior and is mediated through a 5-HT2C receptor mechanism.

Keywords: Aggression, Defensive rage, Cat, PAG, 5-HT2 receptor, IL-1β, Medial hypothalamus

1. Introduction

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by activated monocytes and macrophages in response to infection or injury (Dinarello, 1991). In addition to its role in the immune system, IL-1β derived from local or systemic sources may function in the brain to modulate neurochemical and neuroendocrine responses (Dantzer et al., 2007). For example, administration of IL-1β, either centrally or peripherally, potently modulates, among other functions, monoamine turnover, HPA axis activity, and thermoregulatory activity (Besedovsky and del, 1987; Dantzer et al., 2007; Dascombe et al., 1989). In brain, IL-1β is synthesized and released by glial cells and IL-1 receptors are widely distributed in the regions of temporal lobe, hippocampus, cerebral cortex, medial hypothalamus and cerebellum (Ericsson et al., 1995; Farrar et al., 1987; Hassanain et al., 2005; Takao et al., 1990; Yabuuchi et al., 1994).

Considerable attention has focused on the modulatory effects of IL-1β on brain serotonin activity. Local release of IL-1β is increased by microinjections of this cytokine into discrete brain regions, including the CA1 region of hippocampus (Broderick, 2002), medial basal hypothalamus (Mohankumar et al., 1991; Mohankumar et al., 1993) and anterior hypothalamus (Shintani et al., 1993). Systemic IL-1β administration has also been shown to increase anterior hypothalamic unit activity (Bartholomew and Hoffman, 1993) and turnover of 5-HT in hypothalamus and in extra-hypothalamic sites (Kabiersch et al., 1988; Merali et al., 1997; Zalcman et al., 1994). In another study, Gemma et al., (2003) provided support for the view that serotonin can regulate IL-1 expression in the brain. In this study, peripheral administration of the serotonin precursor, L-5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) selectively increased IL-1β mRNA expression in the hypothalamus 6 hr post injection after an initial decrease at 1 hr post-injection. IL-1β also modulates behaviors that are associated with alterations in brain 5-HT activity (see Dantzer et al., 2007). These include social investigation, exploration of a novel environment, sleep and feeding, among other behaviors (Bartholomew and Hoffman, 1993; Broderick, 2002; del and Besedovsky, 1987; El-Haj et al., 2002; Imeri et al., 1999; Laviano et al., 1999; Mrosovsky et al., 1989; Parnet et al., 2002). Most recently, our laboratory has demonstrated that microinjections of relatively low doses of IL-1β into medial hypothalamus potently facilitate feline defensive rage behavior elicited from the midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) (Hassanain et al., 2005). It was further shown that this effect is mediated via a 5-HT2 receptor mechanism.

Defensive rage, a form of aggressive behavior typically studied in the cat, is characterized by marked hissing, arching of the back, piloerection, retraction of the ears and extension of its claws. The significance of this model is underscored by the fact that this form of aggressive behavior occurs in response to a real or perceived threat within an animal’s environment (Layhausen, 1979). Because this response involves a reciprocal anatomical and functional relationship between the medial hypothalamus and PAG, it can reliably be elicited from both of these regions by electrical stimulation over a period of weeks and even months.

The application of this model for the study of cytokines in aggression in the present as well as in previous studies conducted in our laboratory is based upon the following rationale which lists the strengths of this model. First, the response elicited by brain stimulation closely mimics a form of aggressive behavior exhibited under natural environmental conditions. Second, this response can be elicited easily by electrical stimulation of the hypothalamus or PAG in a repeated manner over a given experimental session. Third, this response can be quantified by measuring current threshold or latency. Fourth, the response is stable, thus permitting systematic examination of how this form of aggression can be modified by physiological or pharmacological challenge to the animal, or by changes in environmental conditions. Fifth, this model relates to human aggression and justification for this conclusion has been demonstrated (Meloy, 1987; 1997; Vitiello et al, 1990; Vitiello and Stoff, 1999). These studies provide evidence that underscores the parallels between feline and human aggression and thus points to the value of this animal model of aggression in providing insights into the neural mechanisms underlying human aggression.

Previous studies conducted in our laboratory have identified the basic neural circuitry and related neurotransmitter-receptor functions utilizing this model of defensive rage behavior in the cat (Siegel et al, 1999; Siegel et al., 2007). Recently, our laboratory has applied this knowledge in order to characterize the effects of cytokines upon defensive rage behavior and to identify the underlying neurochemical mechanisms. The advantage of this approach is that it permits analysis of the site-specific loci of the effects of cytokines upon a given behavioral process, which has previously been lacking in the literature. In our initial studies, microinjections of low doses of IL-1β into the medial hypothalamus potently facilitated defensive rage behavior elicited from the PAG that was mediated through 5-HT2 receptors. In another set of experiments, we observed that the nature of cytokine-induced modulation of defensive rage may depend on interactions with neurotransmitter receptors principally involved in this behavior as well as the site of cytokine microinjection in brain. Specifically, intracerebral microinjections of IL-2 into medial hypothalamus suppressed defensive rage behavior (Bhatt et al., 2005), while microinjections into the PAG facilitated the defensive rage (Bhatt and Siegel, 2006). It was further demonstrated that the effects of IL-2 in the medial hypothalamus are mediated through GABAA receptors (Bhatt et al., 2005), while in the PAG, the potentiating effects of IL-2 are mediated through NK-1 receptors (Bhatt and Siegel, 2006). As noted above, microinjections of IL-1β into the medial hypothalamus potently facilitate defensive rage behavior elicited from the PAG via a 5-HT2 receptor mechanism (Hassanain et al., 2005). In the present study, we sought to identify the effects of IL-1β in the PAG upon defensive rage behavior and its relationship to neurotransmitter function.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Ten adult female cats weighing between 2 and 4 kg (Liberty laboratories, Waverly, NY) were used in this study. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the New Jersey Medical School.

2.2. Surgery

During aseptic surgery, twenty-four stainless steel guide tubes (17 gauge, 10 mm in length) were stereotaxically mounted bilaterally (Atlas of Jasper and Ajmone-Marsan, 1954) over holes drilled through the skull overlying the medial and lateral hypothalamus, and dorsal midbrain PAG. Details of the surgical procedures have been described elsewhere (Bhatt et al., 2003; Bhatt et al., 2005; Gregg and Siegel, 2003; Hassanain et al., 2003; Hassanain et al., 2005).

2.3. Elicitation of defensive rage behavior and predatory attack

Following a 2 week recovery period after surgery, cats were habituated to the experimental cage, veterinary restraining bag and head holder over the course of several days before initiation of experiments. Experiments were carried out in awake, freely moving cats.

Defensive rage behavior was induced by utilizing procedures identical to those used previously in our laboratory (Bhatt et al., 2003; Bhatt et al., 2005; Bhatt and Siegel, 2006; Hassanain et al., 2003; Hassanain et al., 2005; Jasper and Ajmone-Marsan, 1954). A cannula electrode (23 gauge) and a monopolar stimulating electrode (51.5 mm), both insulated throughout its length except at 0.5 mm from the tip (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA), were lowered into the PAG and medial hypothalamus, respectively. The cannula electrode was used both for injection of drugs and for stimulation. Electrodes were lowered in 0.5 mm increments through guide tubes implanted on the skull overlying either the medial hypothalamus or PAG. At each of these increments, electrical stimulation was applied with biphasic, rectangular electrical pulses (0.2–0.8 mA, 63 Hz, 1 ms per half cycle duration), generated by a grass S-88 stimulator connected through differential amplifiers (Tektronix ADA400A) to the cat. Currents were monitored with a Tektronix TDS 3012 digital oscilloscope. Following identification of a defensive rage site the monopolar (or cannula) electrode was cemented in place.

Predatory attack behavior, elicited by stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus, is characterized by initial stalking of the anesthetized rat followed by vigorous biting of its neck (Wasman and Flynn, 1962). The methods for inducing predatory attack in the laboratory are similar to that for defensive rage and are described in detail elsewhere (Bhatt et al., 2005; Han et al., 1997). In the present study, predatory attack was utilized principally as a behavioral control against non-specific effects of IL-1β.

2.4. Measurement of defensive rage and predatory attack

Response latencies for elicitation of hissing, used as a standard measure of defensive rage (Bhatt et al., 2005; Bhatt and Siegel, 2006), or biting of the back of the neck of an anesthetized rat (Wasman and Flynn, 1962), as the measure for predatory attack, was defined as the time required for the cat to express the specific form of aggressive response following onset of electrical stimulation.

The duration of stimulation was limited to 15 s on all trials. If a response could not be elicited within 15 s, a response latency score of 15 s was recorded for that trial even though stimulation was ineffective in generating defensive rage (or predatory attack). If the response was elicited within 15 s, stimulation was terminated and the response latency was recorded.

2.5. Dual stimulation

A dual stimulation procedure, in which 10 paired trials of single stimulation of the medial hypothalamus and dual stimulation of the PAG and medial hypothalamus were administered (at 63 Hz with a 4 ms delay separating biphasic pulses delivered to each region) in an A–B–B–A fashion in which ‘A’ represented stimulation of the medial hypothalamus alone and ‘B’ dual stimulation of the medial hypothalamus plus PAG, was utilized. This method identified sites in the PAG at which stimulation facilitates defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus, in order to ensure the functional relationship between PAG and hypothalamic attack sites in each cat. The current applied to the modulating site in the PAG was maintained at a level below threshold for elicitation of hissing. Response latencies for hissing were determined for each trial. Sites in the PAG that significantly modulated hypothalamically elicited defensive rage were utilized for microinjections of drugs.

2.6. Drugs and drug administration

Selective doses of IL-1β (PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ), anti-human IL-1β receptor type 1 (IL-1RI) neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, Cat # MAB280), 5-HT2 receptor antagonist Ly53857, CCKb receptor antagonist CR 2945 and NK1 receptor antagonist GR82334 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and IgG2a (MP biomedicals, Solon, OH, Cat # 643361) were utilized in this study. Drug dose levels were selected on the basis of findings obtained from pilot experiments in our laboratory. Since the same site was used for administration of different doses of drug, dual stimulation was employed after every 4–5 experimental sessions in order to test the efficacy of the site.

Methods for drug delivery have been described in detail elsewhere (Bhatt et al., 2005; Bhatt and Siegel, 2006; Hassanain et al., 2003; Hassanain et al., 2005). Prior to drug administration, baseline response latencies following medial hypothalamic stimulation were determined. After drug or saline was injected in a total volume of 0.25 μl over a period of 2 min, the syringe was left in place for 1 min to allow for diffusion, and was then slowly removed. Five trials of stimulation were administered over each of the following four blocks of time: 30–40, 60–70, 120–130 and 180–190 min post-injection, with an average inter-trial interval of 2 min. Experiments utilizing pretreatment with an antagonist or antibody prior to microinjection of IL-1β, included a 5 min delay between microinjections with a total injection volume of 0.5 μl. Following completion of each experimental session, the cat was monitored closely by veterinarians for symptoms of sickness behavior and for any of changes in behavior in its home cage. Experimental sessions were separated by at least 48 h in order to minimize the possible interfering effects of prior drug exposure.

A total of five cats received microinjections of each dose of the following drugs and drug interactions: (a) a dose–response analysis which included administration of three doses of IL-1β (1, 2.5 and 5 ng) and saline; analysis of the effects of: (b) anti- IL-1 receptor antibody (5ng), (c) 5-HT2 receptor antagonist LY53857 (3nmol), (d) CCKb receptor antagonist CR 2945 (6nmol), (e) the NK1 receptor antagonist, GR82334 (8 nmol) and (f) antibody isotype control (IgG2a, 5ng). The order of treatments was randomly determined in order to control for the effects of drug exposure. Each animal was utilized as its own control because it received all doses of the same drugs. The final experiment, designed to test the efficacy of the defensive rage sites, included a comparison of the effects of pre-treatment with antibody against administration of IL-1β plus vehicle. In each of the instances in which IL-1β was administered together with vehicle, the hissing response was clearly present, indicating the continued efficacy of these sites.

2.7. Behavioral specificity of IL-1β

The behavioral specificity of IL-1β was explored by comparing its effects upon predatory attack behavior (n = 3). The same paradigm utilized for the study of defensive rage was employed for the study of predatory attack behavior.

2.8. Histology

Cats were perfused transcardially under deep anesthesia (pentobarbital 100 mg/Kg body weight) with 9.25% sucrose solution in PBS (w/v) (pH 7.2) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) at 4 °C. Brains were removed from the skull, blocked, and stored in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution at 4 °C overnight. Then, brains were placed in 30% sucrose solution at 4 °C until they sunk to the bottom. Brain sections were cut in a cryostat (Leica CM1900) at 20–25 μm at −20 °C, air dried and stored at −20 °C.

2.9. Immunohistochemistry and Western blotting

For IL-1RI and 5-HT2 receptors staining, previously described methods were used (Bhatt et al., 2005; Bhatt and Siegel, 2006). The primary antibodies for staining of IL-1 (anti-IL-1RI, rabbit polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA Cat # SC688) and 5-HT2 receptors (anti-5-HT2C, goat polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat # SC15081) were used at a dilution of 1:200. The secondary antibodies used were bovine anti rabbit-FITC for IL-1RI (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat # SC2365) and bovine anti-goat-Rhodamine for 5-HT2C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, Cat # SC2349) at a dilution of 1:500. Photomicrographs of sections were taken with an Olympus AX-70 microscope using an Optronics Microfire digital camera.

Protein from PAG of cats not used in behavioral studies was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Biorad laboratories, Hercules, CA) and the specificity of primary antibodies to IL-1 receptor type I and 5-HT2c receptor used in immunohistochemistry were confirmed by Western blotting using the standard protocol.

2.10. Statistical analysis

A t-test for paired observation was used to determine the effects of dual vs. single stimulation. Since pre-injection baseline latencies differed among animals, data were transformed from response latency scores to percentage changes in response latencies relative to baseline response latencies for the remaining statistical analyses. Percentage changes were calculated as follows: percentage change = [(pre-drug latency post-drug latency)/pre-drug latency] × 100.

A two-way randomized blocks ANOVA was used to analyze the effects of different doses of drugs (variable A) upon response latencies over pre-injection and four post-injection time periods (variable B). One-way ANOVAs were used to determine the level of significance of individual doses of drug over four periods of time. A Newman–Keuls Multiple Comparisons test was employed to determine differences in responses at two different points of time with the significance level set at p < 0.05 for all experiments.

3. Results

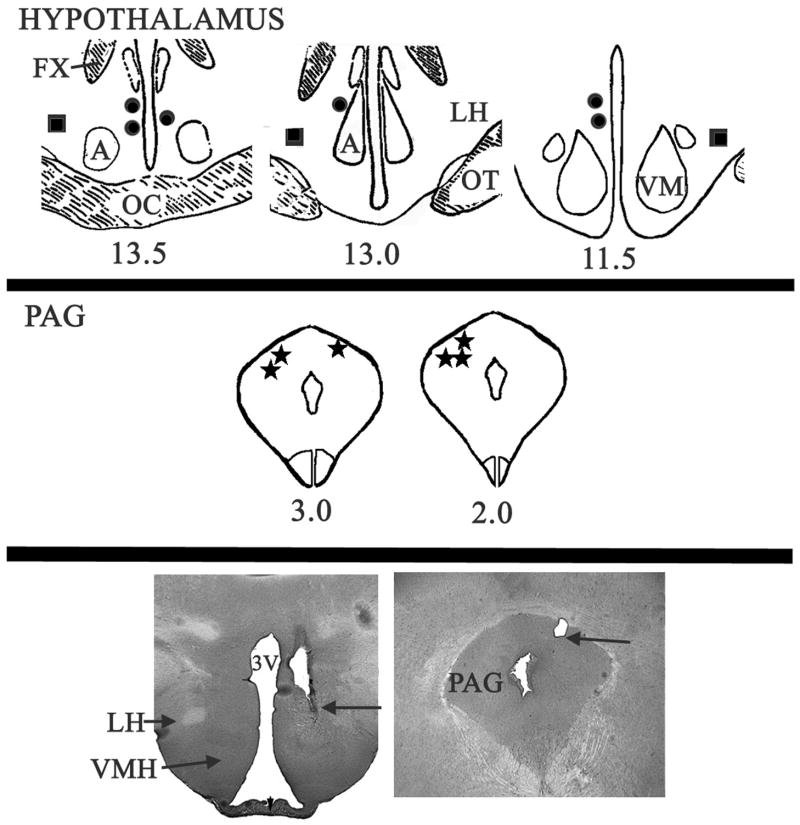

3.1. Anatomical localization of defensive rage sites

As shown in Fig. 1, all electrode tips used to elicit defensive rage by medial hypothalamic stimulation for behavioral–pharmacological experiments were located in or near the anterior, medial and dorsomedial hypothalamus immediately dorsal to the ventromedial nucleus. Electrode tips used to elicit predatory attack were located in the middle third of the lateral hypothalamus. Five of the six electrode tips used for microinjections into the PAG were located on the left side and one on the right side of the dorsal aspect of the PAG.

Fig. 1.

Stimulation and injection sites. Upper panel: Tips of electrodes used to elicit defensive rage from the medial hypothalamus (filled circles) and predatory attack from the lateral hypothalamus (filled squares). Five electrodes were located on the left side of the dorsomedial hypothalamus (for defensive rage) and one on the right side for this response. For predatory attack, two electrodes were located in the ventrolateral aspect of the lateral hyupothalamus of the left and one in the same region of the right side. Lower panel: Location of tips of cannula electrodes used to elicit defensive rage and for microinjections into the PAG (filled stars). Five cannula eleectrodes were located on the left side and one on the right side of the dorsolateral PAG at approximately middle levels along its rostro-caudal axis. . Abbreviations: A, anterior hypothalamus; FX, fornix; LH, lateral hypothalamus; OT, optic tract; PAG, periaqueductal gray; VM, ventromedial hypothalamus (adopted from Atlas of Jasper and Ajmone-Marsan (Jasper et al., 1954)).

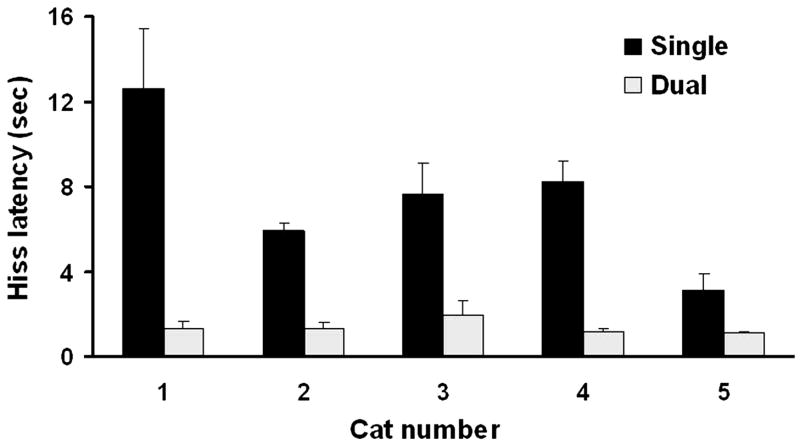

3.2. Modulation of defensive rage following dual stimulation

Dual stimulation of the PAG facilitated MH-elicited defensive rage in each of the cats tested as seen in Fig. 2 (t = 12.34, d.f. = 50.82, p < 0.0001). Following dual stimulation, the average reduction in response latencies was 74% (range 47–95%). The facilitating effects of dual stimulation reflect the presence of a functional excitatory relationship which would provide evidence of the integrity of circuits linking the medial hypothalamus and PAG sites used in this study and thus serve as a rational basis for the subsequent microinjection of IL-1β and other drugs.

Fig. 2.

Dual stimulation involving concurrent stimulation of the medial hypothalamus and PAG facilitated defensive rage behavior elicited from the PAG relative to stimulation of the PAG alone (p < .0001, N = 5).

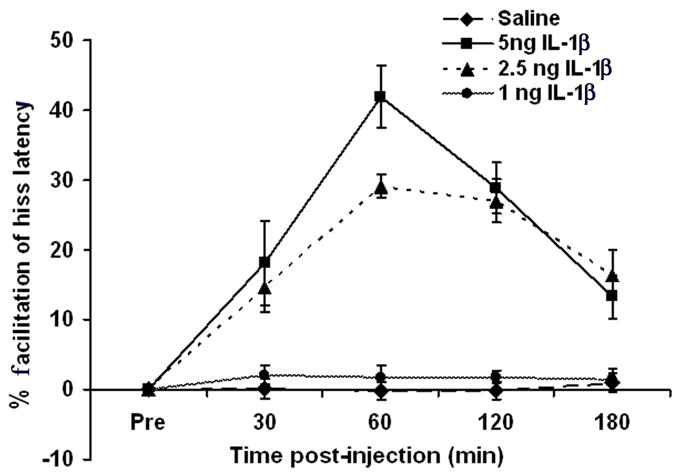

3.3. Facilitation of defensive rage following microinjections of IL-1β into PAG

To determine the effects of IL-1β microinjections into the PAG upon medial hypothalamically elicited defensive rage behavior, three doses of IL-1β (1, 2.5 and 5 ng) and saline were tested over five blocks of time (pre-injection, 30–40, 60–70, 120–130 and 180–190 min). The results of a two-way ANOVA comparing dose vs. time indicated that microinjections of IL-1β into the PAG resulted in a significant facilitation of the hiss response as seen in Fig. 3 [F(3,9) = 85.46, p < 0.0001]. A Post hoc analysis showed that 5 ng of IL-1β induced significant facilitation of hissing when compared to the effects of administration of 1 ng, 2.5 ng or saline. The maximal facilitation, induced by 5 ng of IL-1β, was observed at 60 min (25%), declined over time, but remained significantly above baseline levels even at 180 min, post-injection [one-way ANOVA with respect to time: F(3,192) = 3.01, p < 0.0001]. A dose of 2.5 ng of IL-1β also induced significant facilitation of hissing over time (one-way ANOVA: [F(3,96) = 5.84, p < 0.001]. Doses of either 1 ng or saline had no effect on response latencies for hissing over time (one-way ANOVAs for 1 ng and saline, respectively [F(3,116) = .16, p = 0.92, NS and F(3,96) = 0.052, p = 0.98, NS].

Fig. 3.

Microinjections of IL-1β into the PAG facilitated defensive rage elicited from the medial hypothalamus in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Maximal facilitation of defensive rage was induced by 5 ng of IL-1β at 60 min, post-injection (p < 0.0001, N = 5).

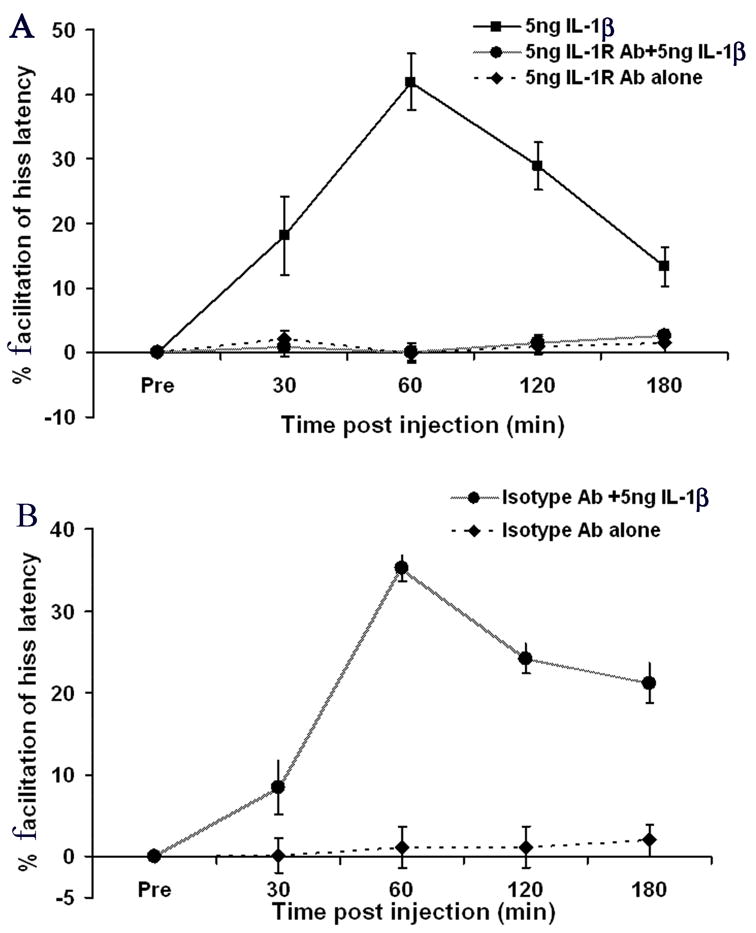

3.4. IL-β induced facilitation of defensive rage response is blocked by pre-treatment with anti-IL-1 receptor antibody

Microinjections of an anti-IL-1 receptor antibody into the same PAG site 5 min prior to microinjections of IL-1β completely blocked the facilitative effects of IL-1β upon medial hypothalamically elicited hissing response [F(2,6) = 103.07, p < 0.0001; (antibody + IL-1β vs. IL-1β alone)]. In contrast, microinjections of the anti-IL-1R antibody alone did not significantly alter response latencies [F(3,96) = 0.17, p = 0.91]. These results demonstrate that the effects mediated by IL-1β are specific and manifested via by IL-1 receptors (Fig 4A).

Fig. 4.

(A) Pre-treatment of the PAG with an anti-IL-1 receptor antibody completely blocked the facilitating effects of IL-1 upon medial hypothalamically elicited defensive rage (p < 0.0001, N = 5). Note that administration of the anti-IL-1 receptor antibody alone did not alter response latencies for hissing (p = 0.91, NS, N =5); (B) Pre-treatment of the defensive rage site in the PAG with an isotype antibody (IgG2a) did not block the potentiating effects of IL-1β upon defensive rage (p < 0.0001, N =2) and that administration of the isotype antibody alone did not alter latencies for defensive rage (p = 0.95, NS, N = 2).

Since it is possible that the antibody, (IgG molecule), itself, may induce non-specific suppression of behavioral responses, an additional control experiment was designed to determine the effects of administration of an IgG isotype on the hissing response. As indicated in Fig. 4B, pretreatment of the PAG attack site with the IgG isotype antibody (IgG2a) did not block or suppress IL-1β induced potentiation of hissing where the effects of IgG + IL-1β were compared against administration of IgG alone [F(1,92) = 149.41, p < 0.0001]. Moreover, administration of IgG alone produced no change in hissing responses [F(3,36) = 0.14, p=0.96, NS]. This control experiment indicates that IgG, itself, has no effect in modulating defensive rage behavior.

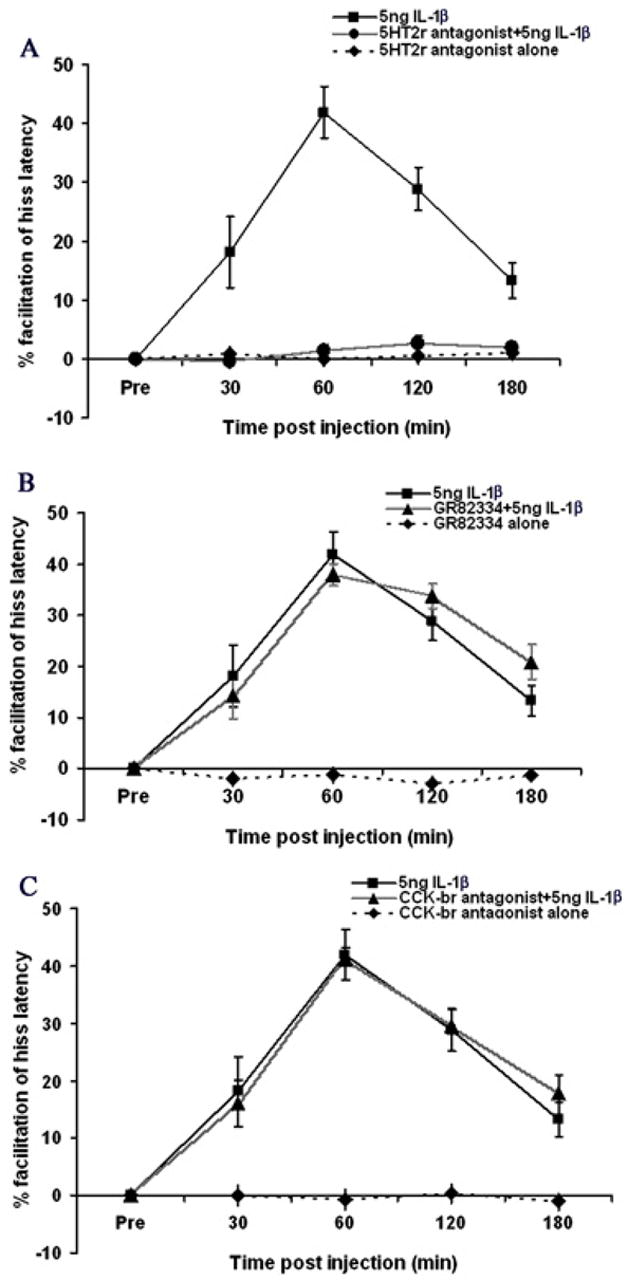

3.5. IL-1β induced facilitation of defensive rage is blocked by pre-treatment with an 5-HT2 receptor antagonist but not with NK-1 or CCKb antagonist

To determine the type(s) of receptors involved in IL-1β induced facilitation of PAG elicited defensive rage, three receptors known to be involved in facilitation of defensive rage within the PAG (as determined from previous studies in our laboratory) were tested—NK-1, 5-HT2 and CCKb receptor (Bhatt et al., 2003; Hassanain et al., 2003; Luo et al., 1998; Shaikh et al., 1997). For this experiment, the same site in the PAG which received microinjections of IL-1β was pre-treated with either the NK1 receptor antagonist, GR82334, 5-HT2 receptor antagonist LY53857, or CCKb antagonist, CR2945. The results, shown in Fig. 5 A, indicated that administration of the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist blocked the facilitative effects induced by IL-1β [F(1,3) = 111.03, p < 0.0001], while pretreatment with GR82334 (Fig 5b) and CR2945 (Fig 5C) prior to IL-1β injection had no effect on hiss latencies [F(1,3)=.177, p=.67, NS and F(1,3)=1.34, p=.24, NS, respectively]. Microinjections of LY53857 or GR82334 or CR2945 alone had no effect upon response latencies for hissing over time [F(3,96) = .112, p = 0.95; F(3,96)=.38, p=.76 and F(3,96)=.14, p=.93, respectively)].

Fig. 5.

(A) Pre-treatment with the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, Ly53857, completely blocked the facilitating effects of IL-1 beta upon defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus (p < 0.0001, N = 5). Administration of the 5-HT2 receptor antagonist alone had no effect upon defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus (p = 0.112, NS); (B) Pre-treatment with the NK-1 receptor antagonist, GR82334, had no effect upon defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus (p = 0.112, NS); (C) Pre-treatment with the CCKb receptor antagonist, CR2945, had no effect upon defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus (p = 0.112, NS).

3.6. Microinjections of IL-1β into the PAG has no effect on predatory attack behavior elicited from the lateral hypothalamus

This experiment was conducted to compare the effects of IL-1β upon another form of aggression, namely, predatory attack behavior. Specifically, we determined the effects of microinjections of IL-1β into the PAG on predatory attack elicited from the lateral hypothalamus. The results of a one-way ANOVA, where 5 ng of IL-1β was microinjected into the PAG (i.e., the dose that was maximally effective against defensive rage) indicated no significant changes in response latencies for predatory attack elicited from the lateral hypothalamus over all time periods examined [F(3,56) = 0.01, p = 0.99]. The percent changes in response latencies following IL-1β administration were as follows: 30 min, 1.64%; 60 min, 1.55%; 120 min, 1.77% and 180 min, 1.26%. The results of this experiment thus provide evidence that the facilitative effects of IL-1β upon defensive rage behavior elicited from the PAG are specific to this form and not to predatory attack.

3.7. Effect of volume

The experiment was carried out to rule out the tonic effects of volume on defensive rage in experiments involving pretreatment of antagonist/antibody followed by IL-1β injections, where a total volume of 0.5 μl was injected compared to single injections of drugs/vehicle where total volume was 0.25 μl. The results indicate that relative percent change in its hiss response latencies following injections of 5 ng of IL-1β and 5 ng IL-1 β plus saline did not differ significantly (F(1,3)=3.01, p=.08, NS).

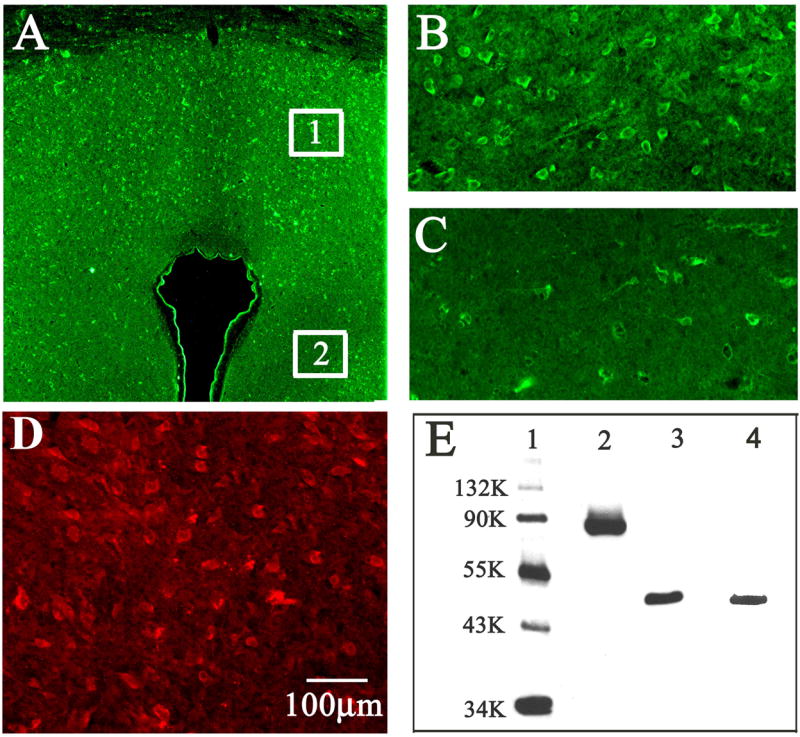

3.8. Immunocytochemical labeling/Western blotting of IL-1β and 5-HT2 receptors

Immunocytochemical analysis, shown in Fig. 6, indicated that IL-1β receptors are distributed widely and in a relatively uniform manner throughout the dorsal half of the PAG (Fig. 6A & 6B). Although IL-1 receptors could also be detected within the ventral aspect of the PAG, a much weaker pattern of labeling was displayed relative to that observed in the dorsal PAG (Fig. 6A & 6C). The labeling pattern of 5-HT2 receptors indicated a relative uniform distribution of these receptors throughout the PAG (Fig. 6D). The specificity of the antibody for these receptors was determined by the western blotting which showed the presence of single band for IL-1βR at 88KD and for 5-HT2 receptor at 47KD (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Immunocytochemical distribution of IL-1β and 5-HT2c receptors in the PAG. Shown are (A) Low power view of the PAG indicating the regions from which photomicrographs of were taken. panel (B) dorsal PAG, depicting relatively intense labeling (taken from region 1 in 7A ), panel (C) ventral PAG, depicting relatively sparse labeling of IL-1β receptors (taken from region 2 in 7A), panel (D) labeling of 5-HT2C receptors and panel (taken from region 1 in 7A ) (D) western blot of IL-1β and 5-HT2C receptors shows: lane 1, molecular weight marker; lane 2, IL-1R1 at 88KD; lane 3, 5-HT2c receptor at 47 KD; and lane 4: β-actin at 46 KD.

4. Discussion

The present study represents a continuation of a recent line of research designed to identify the sites within known neural circuits associated with defensive rage behavior at which specific cytokines interact with neurotransmitter-receptors to powerfully modulate this form of aggression. The principal finding of the present study demonstrated that activation of IL-1 receptors in the PAG potentiates defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus. This finding supports the overall view that brain cytokines can powerfully modulate defensive rage behavior in cats (Bhatt et al., 2005; Bhatt and Siegel, 2006; Hassanain et al., 2005). It extends our previous observations, indicating that IL-1β has a consistent potentiating effect upon defensive rage in both the medial hypothalamus and PAG, where integration of this form of aggression takes place.

It should be noted that the facilitative effects of IL-1β in the PAG could be effectively blocked by pretreatment of the injection site with an IL-1 receptor type I antibody. The results suggest that IL-1β in the PAG facilitates feline defensive rage behavior through IL-1RI and 5-HT receptor mechanisms. Consistent with these findings were the immunocytochemical anatomical observations that revealed the presence of dense quantities of both IL-1RI and 5-HT2 receptors in the dorsal PAG, the region associated with the expression of defensive rage behavior. That an IL-1RI antibody significantly blocked the effects of IL-1β on defensive rage behavior, while microinjections of the IL-1RI antibody alone into the PAG did not influence defensive rage behavior, suggest that its inhibitory effects are not due to any non-specific actions of the drug. In addition, the absence of an effect of administration of the IL-1RI antibody alone further suggests that facilitation of defensive rage within the PAG is manifest through a phasic rather than through a tonic mechanism.

By pretreating the injection site with the selective 5-HT2 receptor antagonist, LY-53857, we were able to block the facilitative effects of IL-1β on defensive rage, while pretreatment with an NK-1 or CCKb receptor antagonist had no effect on IL-1β induced facilitation of defensive rage. This finding indicates the specificity of the effects 5-HT2 receptors in mediating of IL-1β induced facilitation of defensive rage. The results further indicate that the mechanisms underlying modulation of defensive rage in the cat utilized by IL-1β may be similar in both the medial hypothalamus and PAG. This conclusion is based upon the fact that the facilitative effects of activation of IL-1β receptors in the medial hypothalamus upon PAG elicited defensive rage, can be blocked by pretreatment with a 5-HT2 receptor antagonist (Hassanain et al., 2003; Hassanain et al., 2005).

Evidence for the existence of an interaction between IL-1β and 5-HT system has been documented. For example, IL-1β modulates 5-HT release and utilization as well as inducing behavioral changes that are associated with central 5-HT alterations, including sickness behavior (Broderick, 2002; Imeri et al., 1999; Laviano et al., 1999; Zubareva et al., 2001). Although, relatively little is known about the downstream signals involved in this interaction, the observation that the maximal facilitation of defensive rage occurs following 5 and 2.5 ng of IL-1β that peaks at 60 min post injection suggests the possible involvement of transcription dependent synthesis of inflammatory mediators. The effects of IL-1β in brain that have a slow onset (45 min to hours) have been shown to be mediated by the induction of cyclooxygenase and the subsequent synthesis and release of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a process that requires 45–60 min (Cao et al., 1997; Lu et al., 1992; Molina-Holgado et al., 2000). In contrast, the effects of IL-1β such as those on body temperature or sleep are observed within minutes of exposure to the cytokine. These effects may be mediated by the fast activation of the N-sphingomyelinase (N-Smase) and ceramide production (Mathias and Kolesnick, 1993; Nalivaeva et al., 2000). They are PGE2 independent and rapidly change the firing rates of neurons following binding of IL-1β to its receptor (Hori et al., 1988; Sanchez-Alavez et al., 2006; Wilkinson et al., 1993). Although the signaling molecules involved in the action of IL-1β upon defensive rage have not been identified, the observation that the maximum effect was observed at 60 minutes post injection suggests that the cyclooxygenase and PGE2 mediated pathway may be involved in IL-1β mediated potentiation of defensive rage in the cat.

The results of the present study further suggest that these cytokine-neurotransmitter interactions and the ensuing behavioral effects may differ from one region of the brain to another. The results of the present study are a case in point. While the evidence suggests that the mechanisms governing IL-1β induced potentiation of defensive rage associated with the medial hypothalamus and PAG are similar, several differences concerning these two regions should be noted. First, the maximal facilitation of defensive rage in the PAG was achieved at 50% of the dose producing an equivalent effect from the medial hypothalamus (i.e. 5 vs 10 ng, respectively) (Hassanain et al., 2005), suggesting that the effects of IL-1β may be more potent in the PAG than medial hypothalamus. However, the greater potency of the effects of IL-1β in the PAG may be due to the presence of greater densities of neurons and their receptors within the PAG relative to the medial hypothalamus. The second and perhaps more significant difference is that the effects of IL-1β in the PAG decline over time; in contrast, the effects of IL-1β in the medial hypothalamus revealed a second peak of facilitation present at 180 min post injection (Hassanain et al., 2005). Concerning this phenomenon, the mechanisms underlying the differential actions of IL-1β in the PAG and medial hypothalamus are not known. However, a possible explanation may lie in the neuroanatomical location of secondary messenger molecules that signal the release of the second peak following IL-1β administration in the medial hypothalamus. One such possible candidate may be prostaglandin acting through an EP3 receptor subtype. Ek et al., (2000) have reported that EP3 plays an important role in IL-1β mediated local release of IL-1β into the brain. These authors further confirmed that, while EP3 is widely distributed in the medial hypothalamus, it is not present in the region of the PAG. Another explanation may lie in the interaction between IL-1 receptor types 1 (IL-1RI) and 2 (IL-1RII). While in the present study, the IL-1RI antibody blocked the behavioral effects of IL-1β, it does not allow the exclusion of a possible contribution of IL-RII in the regulation of the action of IL-1β in the brain. In the immune system, support for this view is based upon the observation that IL-1RII has been described as an active regulative target that is able to down regulate the actions of IL-1β (Bossu et al., 1995). Since the co-expression of IL-1RI and IL-1RII varies from region to region in brain (Parnet et al., 2002), this phenomenon could account for the variations in the regulatory effects of IL-1 receptors in the hypothalamus and PAG upon defensive rage behaviors including, its effects upon this response beyond 60 min, post injection.

The overlapping distribution of IL-1RI and 5-HT receptors presents an interesting pattern and provides anatomical support for the pharmacological-behavioral observations reported above. In the present study, this relationship was observed in the region proximal to the injection sites in the PAG. Although evidence for the possible mechanisms for the interaction between IL-1 receptors and 5-HT is lacking in literature, the following possible mechanism is proposed as an explanation to the phenomenon observed in the present study. Our hypothesis is that activation of IL-1 receptors activates signals that have excitatory effects upon 5-HT neurons thus providing excitatory inputs to PAG neurons, resulting in the potentiation of defensive rage behavior. Therefore, blockade of 5-HT2 receptors would eliminate the routes by which IL-1β excites PAG neurons associated with the expression of defensive rage behavior.

In summary, we have demonstrated that microinjections of low doses of IL-1β into defensive rage sites in the PAG potentiates defensive rage behavior though a serotonergic 5-HT2 mechanism. These results, in combination with other studies (Laviano et al., 1999; Shaikh et al., 1997; Broderick, 2002; El-Haj et al., 2002), are consistent with the hypothesis that IL-1 induces the release of 5-HT, which results in the facilitation of defensive rage behavior via a 5-HT2 receptor mechanism and that these interactions are site specific.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant NS 07941-35.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bartholomew SA, Hoffman SA. Effects of peripheral cytokine injections on multiple unit activity in the anterior hypothalamic area of the mouse. Brain Behav Immun. 1993;7:301–316. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1993.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besedovsky H, del RA. Neuroendocrine and metabolic responses induced by interleukin-1. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18:172–178. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490180124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Gregg TR, Siegel A. NK1 receptors in the medial hypothalamus potentiate defensive rage behavior elicited from the midbrain periaqueductal gray of the cat. Brain Res. 2003;966:54–64. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Siegel A. Potentiating role of interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptors in the midbrain periaqueductal gray (PAG) upon defensive rage behavior in the cat: role of neurokinin NK(1) receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Zalcman S, Hassanain M, Siegel A. Cytokine modulation of defensive rage behavior in the cat: role of GABAA and interleukin-2 receptors in the medial hypothalamus. Neuroscience. 2005;133:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu P, Visconti U, Ruggiero P, Macchia G, Muda M, Bertini R, Bizzarri C, Colagrande A, Sabbatini V, Maurizi G. Transfected type II interleukin-1 receptor impairs responsiveness of human keratinocytes to interleukin-1. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1852–1861. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick PA. Interleukin 1alpha alters hippocampal serotonin and norepinephrine release during open-field behavior in Sprague-Dawley animals: differences from the Fawn-Hooded animal model of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1355–1372. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(02)00301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Matsumura K, Watanabe Y. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in the brain by cytokines. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;813:307–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, Bluthe RM, Kent S, Kelley KW. Behavioural effects of cytokines. Pergamon; New York: 2007. Interleukin-1 in the brain; pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Dascombe MJ, Rothwell NJ, Sagay BO, Stock MJ. Pyrogenic and thermogenic effects of interleukin 1 beta in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1989;256:E7–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.256.1.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del RA, Besedovsky H. Interleukin 1 affects glucose homeostasis. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:R794–R798. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.5.R794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Interleukin-1 and interleukin-1 antagonism. Blood. 1991;77:1627–1652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek M, Arias C, Sawchenko P, Ericsson-Dahlstrand A. Distribution of the EP3 prostaglandin E(2) receptor subtype in the rat brain: relationship to sites of interleukin-1-induced cellular responsiveness. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:5–20. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<5::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Haj T, Poole S, Farthing MJ, Ballinger AB. Anorexia in a rat model of colitis: interaction of interleukin-1 and hypothalamic serotonin. Brain Res. 2002;927:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03305-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson A, Liu C, Hart RP, Sawchenko PE. Type 1 interleukin-1 receptor in the rat brain: distribution, regulation, and relationship to sites of IL-1-induced cellular activation. J Comp Neurol. 1995;361:681–698. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar WL, Kilian PL, Ruff MR, Hill JM, Pert CB. Visualization and characterization of interleukin 1 receptors in brain. J Immunol. 1987;139:459–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemma C, Imeri L, Opp MR. Serotonergic activation stimulates the pituitary-adrenal axis and alters interleukin-1 mRNA expression in rat brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28:875–884. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg TR, Siegel A. Differential effects of NK1 receptors in the midbrain periaqueductal gray upon defensive rage and predatory attack in the cat. Brain Res. 2003;994:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Shaikh MB, Siegel A. Ethanol enhances medial amygdaloid induced inhibition of predatory attack behaviour in the cat: role of GABAA receptors in the lateral hypothalamus. Alcohol Alcohol. 1997;32:657–670. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanain M, Bhatt S, Siegel A. Differential modulation of feline defensive rage behavior in the medial hypothalamus by 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptors. Brain Res. 2003;981:201–209. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanain M, Bhatt S, Zalcman S, Siegel A. Potentiating role of interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) and IL-1beta type 1 receptors in the medial hypothalamus in defensive rage behavior in the cat. Brain Res. 2005;1048:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T, Shibata M, Nakashima T, Yamasaki M, Asami A, Asami T, Koga H. Effects of interleukin-1 and arachidonate on the preoptic and anterior hypothalamic neurons. Brain Res Bull. 1988;20:75–82. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(88)90010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imeri L, Mancia M, Opp MR. Blockade of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin)-2 receptors alters interleukin-1-induced changes in rat sleep. Neuroscience. 1999;92:745–749. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper HH, Ajmone-Marsan CA. Stereotaxic atlas of the diencephalon of the cat. National Research Council of Canada; Ottawa: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Kabiersch A, del RA, Honegger CG, Besedovsky HO. Interleukin-1 induces changes in norepinephrine metabolism in the rat brain. Brain Behav Immun. 1988;2:267–274. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(88)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviano A, Cangiano C, Fava A, Muscaritoli M, Mulieri G, Rossi FF. Peripherally injected IL-1 induces anorexia and increases brain tryptophan concentrations. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;467:105–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4709-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layhausen P. Cat behavior, The predatory and social behavior of domestic and wild cats. Garland STPM Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Lu CL, Shaikh MB, Siegel A. Role of NMDA receptors in hypothalamic facilitation of feline defensive rage elicited from the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Brain Res. 1992;581:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B, Cheu JW, Siegel A. Cholecystokinin B receptors in the periaqueductal gray potentiate defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus of the cat. Brain Res. 1998;796:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias S, Kolesnick R. Ceramide: a novel second messenger. Adv Lipid Res. 1993;25:65–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloy RJ. The psychopathic mind: origins, dynamics, and treatment. Jason Aronson, Inc; Northvale, NJ: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Meloy RJ. Predatory violence during mass murder. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42:326–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merali Z, Lacosta S, Anisman H. Effects of interleukin-1beta and mild stress on alterations of norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin neurotransmission: a regional microdialysis study. Brain Res. 1997;761:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohankumar PS, Thyagarajan S, Quadri SK. Interleukin-1 stimulates the release of dopamine and dihydroxyphenylacetic acid from the hypothalamus in vivo. Life Sci. 1991;48:925–930. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90040-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohankumar PS, Thyagarajan S, Quadri SK. Interleukin-1 beta increases 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid release in the hypothalamus in vivo. Brain Res Bull. 1993;31:745–748. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90151-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Holgado E, Ortiz S, Molina-Holgado F, Guaza C. Induction of COX-2 and PGE(2) biosynthesis by IL-1beta is mediated by PKC and mitogen-activated protein kinases in murine astrocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:152–159. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrosovsky N, Molony LA, Conn CA, Kluger MJ. Anorexic effects of interleukin 1 in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:R1315–R1321. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.257.6.R1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalivaeva NN, Rybakina EG, Pivanovich IY, Kozinets IA, Shanin SN, Bartfai T. Activation of neutral sphingomyelinase by IL-1beta requires the type 1 interleukin 1 receptor. Cytokine. 2000;12:229–232. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnet P, Kelley KW, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R. Expression and regulation of interleukin-1 receptors in the brain. Role in cytokines-induced sickness behavior. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;125:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Alavez M, Tabarean IV, Behrens MM, Bartfai T. Ceramide mediates the rapid phase of febrile response to IL-1beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2904–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510960103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh MB, De Lanerolle NC, Siegel A. Serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2/1C receptors in the midbrain periaqueductal gray differentially modulate defensive rage behavior elicited from the medial hypothalamus of the cat. Brain Res. 1997;765:198–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani F, Kanba S, Nakaki T, Nibuya M, Kinoshita N, Suzuki E, Yagi G, Kato R, Asai M. Interleukin-1 beta augments release of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in the rat anterior hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3574–3581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03574.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takao T, Tracey DE, Mitchell WM, De Souza EB. Interleukin-1 receptors in mouse brain: characterization and neuronal localization. Endocrinology. 1990;127:3070–3078. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-6-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello B, Behar D, Hunt J, Stoff D, Ricciuti A. Subtyping aggression in children and adolescents. J Neuropsychiatr. 1990;2:189–192. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello B, Stoff DM. Subtypes of aggression and their relevance to child psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:307–315. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasman M, Flynn P. Directed attack elicited from hypothalamus. Arch Neurol. 1962;6:220–227. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1962.00450210048005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MF, Mathieson WB, Pittman QJ. Interleukin-1 beta has excitatory effects on neurons of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Brain Res. 1993;625:342–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi K, Minami M, Katsumata S, Satoh M. Localization of type I interleukin-1 receptor mRNA in the rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1994;27:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalcman S, Green-Johnson JM, Murray L, Nance DM, Dyck D, Anisman H, Greenberg AH. Cytokine-specific central monoamine alterations induced by interleukin-1, -2 and -6. Brain Res. 1994;643:40–49. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubareva OE, Krasnova IN, Abdurasulova IN, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Klimenko VM. Effects of serotonin synthesis blockade on interleukin-1 beta action in the brain of rats. Brain Res. 2001;915:244–247. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02910-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]