Abstract

Ire1 is an ancient transmembrane sensor of ER-stress with dual protein kinase and ribonuclease activities. In response to ER stress, Ire1 catalyzes the splicing of target mRNAs in a spliceosome independent manner. We have determined the crystal structure of the dual-catalytic region of Ire1at 2.4Å resolution, revealing the fusion of a domain, which we term the KEN domain, to the protein kinase domain. Dimerization of the kinase domain composes a large catalytic surface on the KEN domain which carries out ribonuclease function. We further show that signal induced trans-autophosphorylation of the kinase domain permits unfettered binding of nucleotide, which in turn promotes dimerization to compose the ribonuclease active site. Comparison of Ire1 to a topologically disparate ribonuclease reveals the convergent evolution of their catalytic mechanism. These findings provide a basis for understanding the mechanism of action of RNaseL and other pseudo-kinases, which represent 10% of the human kinome.

Introduction

Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) stress is characterized by the accumulation of toxic misfolded protein aggregates in the ER lumen (Bernales et al., 2006; Ron and Walter, 2007). Ire1 is an evolutionarily conserved, ER-stress sensor present in all eukaryotes with both protein kinase and ribonuclease activities (Sidrauski and Walter, 1997). These activities are critical for the induction of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) - a complex set of homeostatic mechanisms evolved to cope with ER stress in eukaryotes by promoting protein folding and maturation in the ER (Bernales et al., 2006; Ron and Walter, 2007).

Ire1 detects elevated unfolded protein levels in the ER and transmits a signal to the nucleus by splicing mRNAs encoding master transcriptional regulators of the UPR response – Hac1p in yeast and Xbp1 in metazoans – independent of the spliceosome (Calfon et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2002; Sidrauski and Walter, 1997; Yoshida et al., 2001). Ire1 cleaves a single phosphodiester bond in each of two RNA hairpins (with non-specific base paired stems and loops of consensus sequence CNCNNGN, where N is any base)(Gonzalez et al., 1999) to remove an intervening intron from target transcripts. A second enzyme, the yeast tRNA ligase Rlg1, joins the adjacent exons to generate a mature transcript (Gonzalez et al., 1999; Sidrauski et al., 1996) (the metazoan homolog of Rlg1 has yet to be identified). Removal of the intron introduces a frame shift that yields a functional activator of the UPR (Calfon et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2002; Mori, 2003; Sidrauski and Walter, 1997; Yoshida et al., 2001). The mature forms of Xbp1 and Hac1 execute the UPR transcription program to upregulate the expression of a multitude of gene products including ER-resident proteins that promote protein folding and maturation and ER-associated proteins involved in protein degradation (Travers et al., 2000).

Ire1 is a type I transmembrane receptor consisting of an N-terminal ER luminal domain, a transmembrane segment and a cytoplasmic region. The cytoplasmic region of Ire1 encompasses a protein kinase domain followed by a C-terminal extension of ~150 residues. The x-ray crystal structure of the luminal domain of yeast and human Ire1 have been determined (Credle et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2006), shedding light into signal dependent dimerization /oligomerization of the receptor. No structural information has been forthcoming for the cytoplasmic/enzymatic portion of the protein. The cytoplasmic region of Ire1 contains its catalytic activities and is related to the anti-viral ribonuclease RNaseL, which is thought to share a common ribonuclease mechanism. Unlike Ire1, RNaseL lacks protein kinase activity and cleaves single-stranded RNA to inhibit protein synthesis in response to viral stress (Floyd-Smith et al., 1981). While kinase activity seems expendable in the ribonuclease mechanism of RNaseL, and by inference that of Ire1, the structural integrity of the kinase domains of both Ire1 and RNaseL are, paradoxically, essential for their ribonuclease functions. Incidentally, neither Ire1 nor RNaseL display sequence similarity to known nucleases.

Structural and biophysical characterization of the luminal domain of human and yeast Ire1 supports the notion that Ire1 has a propensity to dimerize upon exposure to unfolded protein in the ER lumen. In analogy to many transmembrane receptor kinases, the signal induced dimerization/oligomerization of human and yeast Ire1 in the plane of a membrane is thought to promote trans-phosphorylation on positive regulatory sites within the protein kinase domain (minimally Ser 840 and Ser 841 in yeast Ire1) by juxtaposing two kinase domains in close proximity and thus to induce its cytoplasmic kinase activity (Shamu and Walter, 1996; Welihinda and Kaufman, 1996).

In addition to effecting a change in its protein kinase catalytic function, dimerization and auto-phosphorylation of Ire1 lead to the activation of its ribonuclease activity (Sidrauski and Walter, 1997). Interestingly, the ribonuclease function of Ire1 is also greatly potentiated in vitro by the binding of nucleotide (either ADP or ATP and its non-hydrolysable analogues, with ADP having the greatest effect) (Sidrauski and Walter, 1997) presumably to the kinase domain active site. The mechanism by which receptor dimerization, kinase domain auto-phosphorylation and nucleotide binding regulate ribonuclease function remains an open question. In addition, the absence of similarity between Ire1 and any previously characterized ribonuclease enzyme leaves the basis by which Ire1 (and by extension RNaseL) binds and cleaves RNA a complete mystery.

To gain mechanistic insight into the basis of RNA cleavage by Ire1 and the regulatory link between its ribonuclease and protein kinases catalytic functions, we have solved the 2.4Å X-ray crystal structure of a cytoplasmic region of Ire1 encompassing the protein kinase domain and C-terminal kinase extension. Together with mutational and functional analyses on Ire1 performed in vitro and in vivo, these studies further our understanding of how Ire1 transduces a signal across the ER membrane in response to the detection of unfolded protein in the ER lumen.

Results

A survey of N-and C-terminal boundaries uncovered a minimal cytosolic fragment of yeast Ire1 (residues 658 to 1115), denoted Ire1cyto, that expressed well in bacteria as a TEV protease cleavable polyhistidine tag fusion, and that displayed regulatory and catalytic properties of the full length protein (Cox et al., 1993; Mori et al., 1993; Sidrauski and Walter, 1997). Ire1cyto is active as a protein kinase as evidenced by its steady state phosphorylation status following purification from E. coli lysates (see change in electrophoretic mobility following phosphatase treatment - Supplementary Figure 1A) and its ability to autophosphorylate in an enzyme concentration dependent manner in the presence of γ-[32P]-ATP (Supplementary Figure 1B). Mass spectroscopy analysis revealed stoichiometric phosphorylation on two previously characterized regulatory sites (Ser840 and Ser841) (Shamu and Walter, 1996) and two novel sites with no known regulatory function (Thr844, and Ser850) within its activation segment (Supplementary Figure 1C). Mutation of Thr844 but not Ser850 severely impaired Ire1 function in vivo, as observed for mutation of Ser841 and to a lesser degree Ser840 (Supplementary Figure 1D). Ire1cyto cleaves model RNA substrates such as a tandem hairpin substrate derived from human Xbp1, denoted XBP1mini (Supplementary Figure 3A-B) and a single hairpin substrate modeled on the 3’ splice junction hairpin of yeast Hac1 (Supplementary Figure 4A-B), at the physiologically relevant loop positions. RNA cleavage of Xbp1mini was potentiated by dimerization (compare Ire1cyto +/- fusion to a GST dimerization domain), the presence of nucleotide (compare Ire1cyto +/- ADP) with a preference for ADP over the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog AMPPNP (compare Ire1cyto +ADP versus Ire1cyto +AMPPNP), and the phosphorylation status of the enzyme (compare Ire1cyto wild type and a kinase domain active site mutant) (Supplementary Figure 3B, C, D and E, respectively).

Crystals derived from Ire1cyto were not suitable for structure determination. To improve the crystallizability of Ire1cyto, we engineered a variant, denoted Ire1cytoΔ24, containing a 24 residue (C869-F892) internal deletion within the kinase domain that removes a protease labile loop. This loop deletion did not affect the enzymatic properties of the protein in vitro (Supplementary Figure 3F). Only in the presence of the nucleotide ADP did Ire1cytoΔ24 yield crystals (space group P65, a=b=130.3 Å, c=175.0Å, α=β=90°, γ=120°, with two Ire1cytoΔ24 molecules in the asymmetric unit) suitable for structure determination using the selenomethionine single anomalous dispersion method (see methods). A near complete model of Ire1cytoΔ24, lacking fourteen N-terminal residues and three internal sequences corresponding to flexible loops, was refined to Rfactor / Rfree values of 23.8%/27.2% to 2.4 Å resolution. The model displayed good geometry and Ramachandran statistics commensurate with the resolution of this study. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table I. A representative region of experimentally phased electron density is shown in Supplementary Figure 5A. A structure-based sequence alignment of the protein kinase domain and conserved C-terminal extension of Ire1, and for comparison RNaseL, is shown in Figure 1. Ribbon representations of the Ire1 structure are shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 5B.

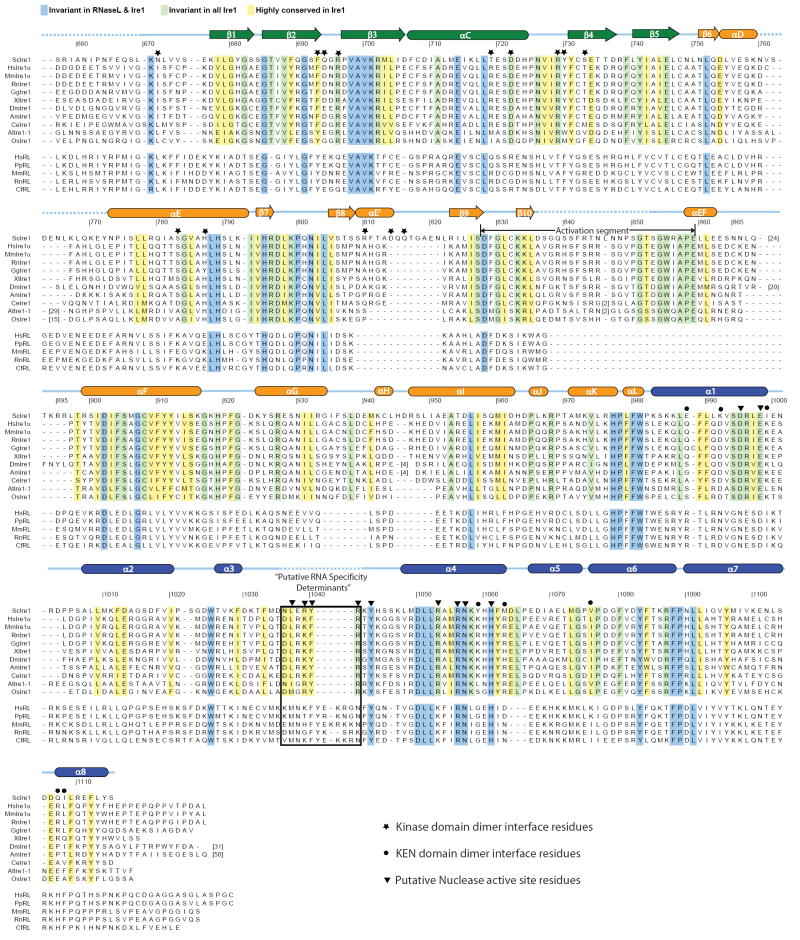

Figure 1. Sequence conservation in the dual-catalytic core of Ire1.

Structure based sequence alignment of the protein kinase domain and KEN (Kinase Extension Nuclease) domain of Ire1 sequences from S. cerevisiae (yeast), H. sapiens (human), M. musculus (mouse), R. norvegicus (rat), G. gallus (chicken), X. laevis (frog), D. melanogaster (fruitfly), A. mellifera (honey bee), C. elegans (nematode), A. thaliana (mouse-ear cress), and O. sativa (rice); and RNase L sequences from H. sapiens (human), P. pygmaeus (orangutan), M. musculus (mouse), R. norvegicus (rat), and C. familiarus (dog). Residues invariant across the Ire1-RNaseL family of kinase-ribonucleases are highlighted in blue, while residues invariant or highly conserved specifically in Ire1 are colored in green and yellow, respectively. The secondary structure of S. cerevisiae Ire1 is indicated above the alignment using the coloring scheme of Protomer 1 in Figure 2A. A conserved disordered region in the KEN domain termed “Putative RNA specificity determinants” is delineated by a black-box. The kinase domain activation segment of Ire1 is indicated by a set of black arrows. Dashed lines represent unmodeled disordered regions of the crystal structure.

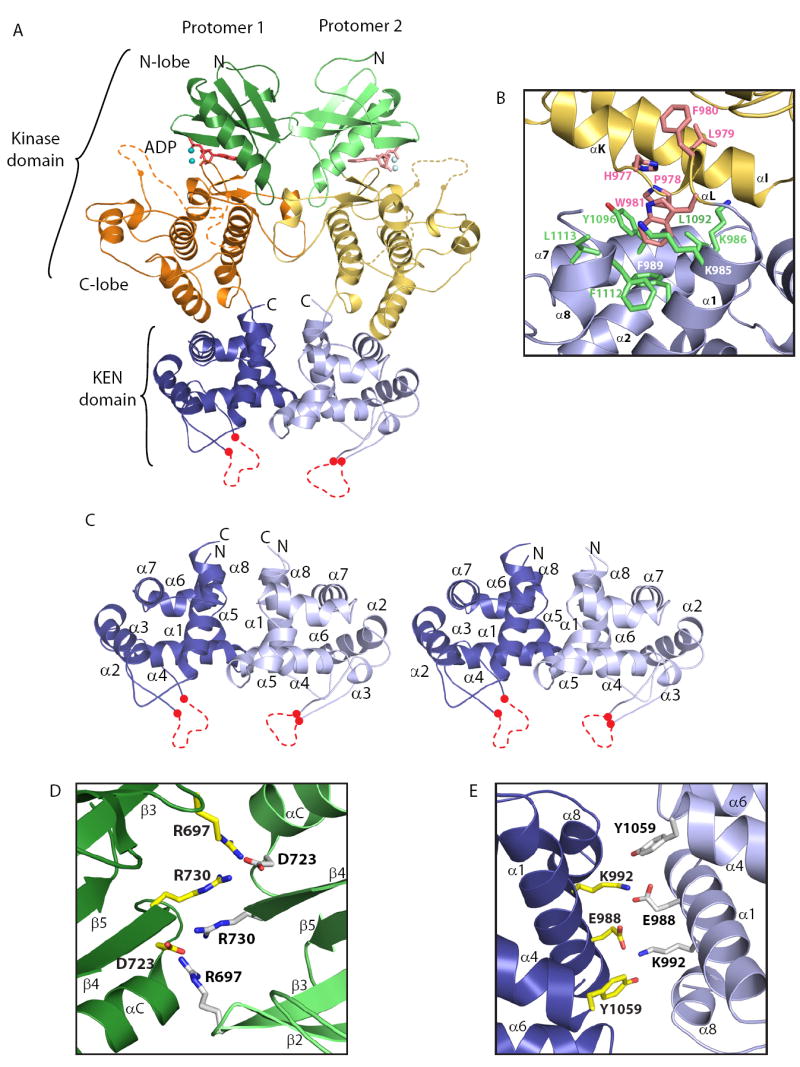

Figure 2. Structure of Ire1.

(A) Ribbons representation of the dimeric dual-catalytic region of Ire1 encompassing the protein kinase domain and KEN domain. The kinase N-lobe, C-lobe and the KEN domain are colored green, orange and blue (protomer 1) and light green, yellow and light blue (protomer 2), respectively. ADP and coordinating metal ions are shown within the kinase domain catalytic cleft. Two internal regions within the kinase domain and one internal region within the KEN domain not modeled due to disorder are shown as dashed lines.

(B) A continuous hydrophobic core connects the kinase C-lobe and the KEN domain. Residues originating from the C-lobe and KEN domain are colored in pink and green, respectively. Ribbons diagram color scheme corresponds to that of protomer 2 in (A).

(C) Detailed stereoview of the KEN domain dimer as shown in (A). Disordered regions corresponding to putative RNA specificity determinants are shown as red dashed lines.

(D) and (E) Dimer interface interactions involving conserved residues in the kinase domain (D) and the KEN domain (E), respectively, viewed along the two fold axis of rotational symmetry. For clarity, only residues targeted for mutation in this study are shown in ball and stick representation. Residues colored yellow and white originate from promoter 1 and 2, respectively. Ribbons coloring scheme corresponds to that in (A).

Structure of the Ire1 protomer

Ire1cytoΔ24 forms a dimer in the crystal environment (Figure 2). Each Ire1 protomer (i.e. half of the dimer) consists of an N-terminal kinase-domain followed by a 132 residue globular domain formed by the conserved C-terminal kinase extension. We have termed the latter domain the kinase-extension nuclease (KEN) domain for reasons explained later in this study.

The kinase domain possesses a prototypical bilobal fold with a smaller N-terminal lobe (N-lobe) and a larger C-terminal lobe (C-lobe). The N-lobe (residues 673 to 748) consists of a twisted 5-strand anti-parallel β sheet (denoted β1 to β5) and a laterally flanking helix αC (Supplementary Figure 5B). The C-lobe (residues 749-982) is comprised of two paired antiparallel β-strands (β7-β10 and β8-β9) and eleven α helices (αD to αL). Positioned between β-strand 10 and helix αEF (and corresponding to residues 828 to 859) is the activation segment, which serves a phospho-regulatory function in many protein kinases including Ire1 (Nolen et al., 2004). In the Ire1cytoΔ24 crystal structure, a major portion of the activation segment (residues 836-852) is disordered. We interpret this to reflect the dynamic nature of the activation segment in its phosphorylated productive state. Lastly, Ire1 possesses a non-canonical helix, denoted αE’, inserted between β-strands β8 and β9 of the C-lobe. This helix resides on the back-side of the protein kinase domain where it participates in dimer formation (discussed below).

Visible within the inter-lobe cleft of each Ire1cytoΔ24 protomer is a fully resolved ADP molecule (Supplementary Figure 5A). The binding of ADP gives rise to a closed conformation of the bi-lobal kinase domain compatible with the phosphor-transfer mechanism. Indeed, all invariant active site residues amongst protein kinases that play a role in nucleotide binding or in the phospho-transfer mechanism are positioned in a productive manner (Supplementary Figure 5B) (reviewed in (Huse and Kuriyan, 2002)).

Extending immediately from the C-lobe of the kinase domain is the KEN domain. The disposition of the KEN domain on the opposite face of the kinase domain C-lobe, relative to the N-lobe, gives rise to an elongated tri-lobal structure (Figure 2A). As assessed by Dali (Holm and Sander, 1995) and VAST (Madej et al., 1995), the eight α-helices (denoted α1 to α8 – Figure 2C) of the KEN domain comprise a novel fold. Within this fold, only a six-residue conserved sequence (Asn1036-Arg1041) between helices α3 and α4 is disordered. The hydrophobic nature of the inter domain contact surfaces appears to enforce a fixed orientation between the KEN domain and the C-lobe of the kinase domain and a co-dependence for proper folding (Figure 2B). This might explain our inability to express stable forms of the individual KEN and kinase domains (data not shown). Sequence conservation across Ire1 and RNaseL orthologues suggests that the KEN domain structure and its relative orientation to the adjacent kinase domain will be shared by RNAseL (Figure 1).

Dimerization of Ire1

Ire1cytoΔ24 adopts a parallel back to back dimer configuration related by a non-crystallographic 2-fold rotation about the long axis of the protomer. The larger of two discontinuous dimerization surfaces is composed by the kinase domain (Figure 2A) and buries a total of 2400 Å2 of area. Residues on this surface include N672, F694, R697, T720, D723, R730, Y731, S783, H787, R810, D814, and Q816 (Figure 1 and 2D). Residues projecting from the N-lobe (specifically β-strands β2, β3, β4 and helix αC) are well conserved across Ire1 orthologous, while those from the C-lobe, (projecting from the non-conical helix αE’ and its flanking linker sequences) appear specific to yeast Ire1.

Comparison of the Ire1cytoΔ24 structure to previously determined protein kinase domain structures reveals great similarity to the dimer configurations of the eIF2α protein kinase PKR (RMSD = 3.72Å) (Supplementary Figure 5C) and the Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein kinases PknB, and PknE (Gay et al., 2006; Ortiz-Lombardia et al., 2003; Young et al., 2003). Since signal induced dimerization of PKR (Dey et al., 2005) and the Pkn family kinases (Greenstein et al., 2007) serves to allostrerically regulate their kinase activities, this similarity raises the possibility of a similar role for dimerization in regulating Ire1 protein kinase function.

The second non-contiguous dimerization surface of Ire1cytoΔ24, is composed entirely by the KEN domain (Figure 2A). Residues on this 1320 Å2 surface, including E988, K992, I999, Y1059, M1063, V1076, Q1107 and I1108, (Figure 1 and 2E). While the majority of these residues are different in the metazoans orthologues, the positions are nevertheless conserved within the metazoan Ire1 group, suggesting that the same dimer configuration of the KEN domain might be accessed by all Ire1 orthologues.

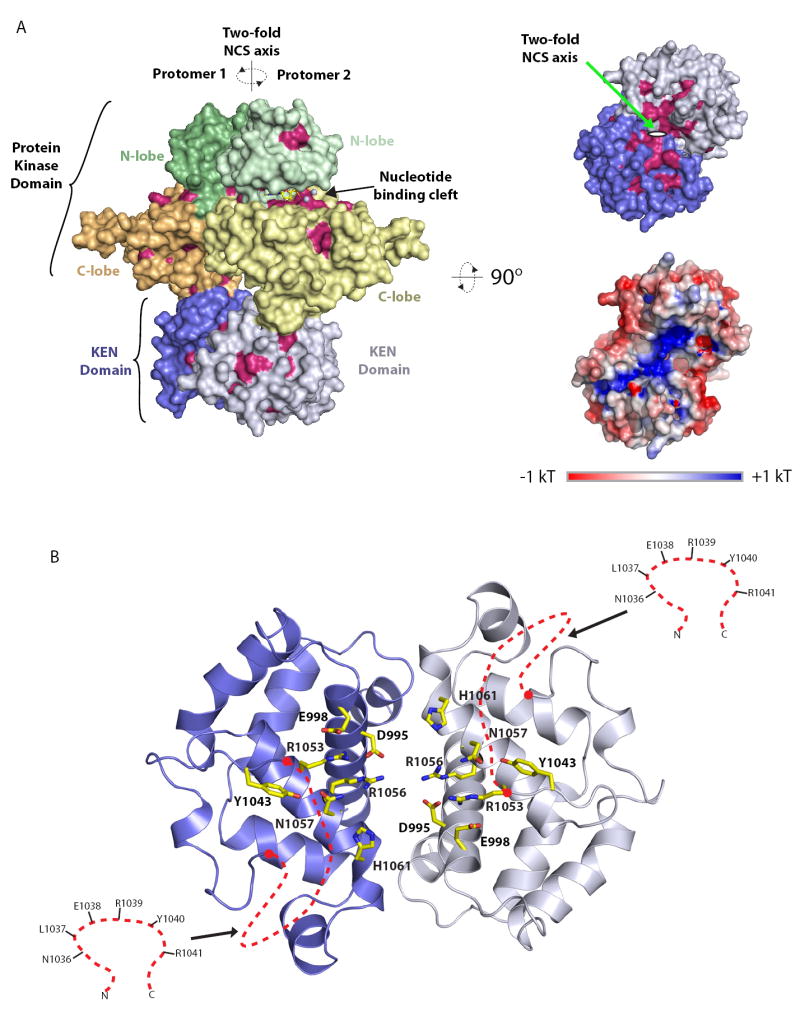

Localization of the putative ribonuclease active site on the KEN domain

The dimer configuration of Ire1cytoΔ24 gives rise to an extensive concave surface on the bottom of the KEN domain. This surface represents the most conserved region of the whole Ire1cytoΔ24 dimer structure (Figure 3A). Within the ordered part of this surface reside three highly conserved residues (D995, E998, R1053) and four invariant residues (Y1043, R1056, N1057 and H1061) (Figure 3B). Within the disordered part of the surface, consisting of a six residue linker connecting helices α3 and α4, reside five highly conserved residues (N1036, L1037, R1039, Y1040, and R1041) (Figure 3B). Based on 1) the pocket like nature of this surface, 2) the observation that four ordered residues, namely Y1043, R1056, N1057, and H1061, are invariant across the larger Ire1/RNAseL ribonuclease family (which likely share a common ribonuclease catalytic mechanism) (Figure 1 and Figure 3B) and 3) the observation that R1056 and H1061 in Ire1 (R667 and H672 in human RNaseL) are essential for ribonuclease function (Dong et al., 2001), we reason that this surface comprises the ribonuclease active site of Ire1. We test this hypothesis experimentally below.

Figure 3. Sequence conservation of Ire1 reveals the ribonuclease active site.

(A) Surface representations of the Ire1cyto dimer. Frontal view (left panel) and bottom view (top right panel) are coloured as in Figure 2A with all highly conserved/invariant residues highlighted in red. Bottom right panel displays a bottom view of Ire1cyto coloured according to electrostatic potential. The axis of two-fold non-crystallographic symmetry is indicated in each view.

(B) Expanded bottom view of a highly conserved surface on the KEN domain. Invariant or highly conserved side chains are displayed in yellow ball and stick representation. The red dashed lines indicate the position of disordered linkers corresponding to putative determinant of RNA specificity. Residues within the disordered linker are shown in inset.

Mutational analysis of the Ire1 dimer contact surfaces

Based on the similarity of the dimer configuration of Ire1cytoΔ24 to the kinase domain structures of PKR and PknB/E, we reasoned that the observed mode of Ire1 dimerization might play an essential role in regulating protein kinase activity. Alternatively, based on the possibility that the ribonuclease active site of Ire1 resides within a composite surface spanning two KEN domains, we reasoned that the Ire1cyto Δ24 dimer configuration might play an essential role in regulating ribonuclease function. To test these models, we introduced site-specific mutations at dimer interface positions of Ire1cyto and tested in vitro ribonuclease and protein kinase functions of recombinant mutant proteins expressed in bacteria.

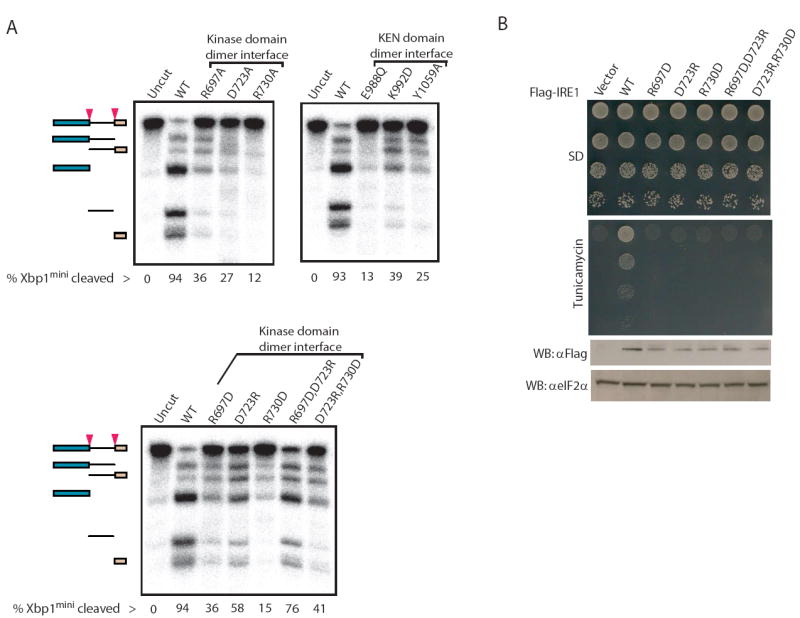

Wild type Ire1cyto cleaved Xbp1mini, yielding the expected products (Figure 4A). In contrast, alanine substitution of kinase domain dimer interface residues R697, D723, and R730 (Figure 2D) or charge reversal mutations R697D, D723R, R730D, greatly perturbed ribonuclease function (Figure 4A). Similarly, KEN domain dimer interface mutations including E988Q, K992D, Y1059A (Figure 2E), greatly compromised the ability to cleave Xbp1mini. In contrast to the potent effect on ribonuclease function, none of the aforementioned dimer interface mutations perturbed protein kinase catalytic function (Supplementary Figure 2A, B and E). Together these results indicate that, in stark contrast to PKR, residues comprising the kinase domain and KEN domain dimer interfaces are essential for the ribonuclease but not the protein kinase function of Ire1.

Figure 4. Kinase domain and KEN domain dimerization surfaces are important for Ire1 ribonuclease function.

(A) Autoradiograms of radiolabelled Xbp1mini cleavage products generated by wild type and the indicated single-site dimer interface mutants of Ire1cyto (top) or single-site and double-site charge reversal mutants of Ire1cyto (bottom). The percentage substrate cleaved is indicated below each lane. Note the marked improvement in cleavage efficiency observed when the charge reversal mutations R697D and D723R or D723R and R730D are combined. All cleavage reactions were performed using identical enzyme and substrate concentrations.

(B) Ire1-null yeast strains transformed with wild type or the indicated dimer interface mutants of full-length FLAG tagged-Ire1 were grown to saturation and 4-μl of 10-fold serial dilutions (starting OD600 = 1.0) were spotted on minimal medium supplemented with essential nutrients (SD) or medium containing 0.25 μg/ml tunicamycin. (Bottom panel) Western analysis of Ire1 expression in yeast. 30-μg of yeast whole-cell extracts, prepared as described previously (Kimata et al., 2004), were separated by SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted using monoclonal anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma) or with anti-eIF2α antibodies as a control.

We next tested whether the double charge reversal mutations R697D/D723R and D723R/R730D, could restore ribonuclease function by reconstituting a dimer spanning salt-bridge in Ire1cyto (Figure 4A, bottom panel). As shown in Figure 4A, both R697D/D723R and D723R/R730D double mutant proteins displayed partial [two-fold] improvement in ribonuclease function relative to the most perturbing single site mutant proteins (i.e. R697D and R730D, respectively). These results strongly support the notion that the specific dimer configuration of Ire1cytoΔ24 observed in the crystal structure is critically important for the ribonuclease function of Ire1.

Consistent with a requirement of the kinase domain dimer interface residues R697, D723 and D730 for ribonuclease function, charge reversal mutations at these positions inactivated yeast Ire1 in vivo without affecting protein levels (Figure 4B, compare vector and WT lanes). In addition, these kinase domain dimer interface mutations blocked the tunicamycin-induced activation of a lacZ reporter gene under the control of a UPR element from the yeast KAR2 gene (Supplementary Figure 6). In contrast to the partial restoration of ribonuclease activity observed in vitro, combining the R697D and D723R or the D723R and R730D mutations failed to rescue growth on medium containing tunicamycin or activation of the tunicamycin-inducible lacZ reporter (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure 6). These data indicate that the salt bridge interactions spanning the kinase domain dimer interface are necessary for Ire1 function in vivo. The inability of yeast expressing the double charge reversal Ire1 mutants to grow on medium containing tunicamycin may indicate that the partial restoration of ribonuclease activity provided by combining these mutations is below the threshold level required for yeast cell growth.

Mutational analysis of the candidate ribonuclease active site

To assess the importance of residues within the candidate ribonuclease active site of Ire1cyto, we introduced site specific mutations into Ire1cyto and tested the mutant recombinant proteins for function as for the dimer interface mutants described above. We first investigated conserved residues on the ordered portion of the KEN domain surface (Figure 3B). We found that the D995A, Y1043A, R1053E, R1056A, N1057A, and H1061A mutant proteins displayed a complete loss of RNA cleavage function (Figure 5A, upper panel), without an apparent loss of protein kinase function (Supplementary Figure 2C and E). We next investigated conserved residues within a disordered loop connecting KEN domain helices α3 and α4 (Figure 3B). We found that the L1037A, R1039A, Y1040A and R1041A but not N1036A mutant proteins, were greatly deficient for ribonuclease function (Figure 5A and B) but not protein kinase function (Supplementary Figure 2D).

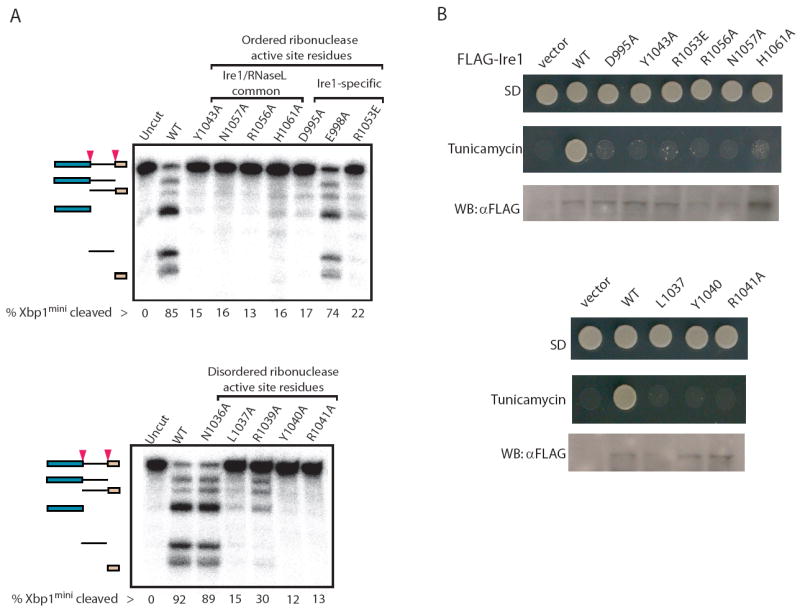

Figure 5. Disruption of the putative ribonuclease active site abrogates ribonuclease function.

(A) Autoradiograms of radiolabelled Xbp1mini cleavage products generated by wild type and the indicated single-site mutants of Ire1cyto within the ordered conserved surface of the KEN domain (top) and the disordered conserved linker adjoining helix α3 and α4 (bottom).

(B) Ire1-null yeast strains transformed with wild type or the indicated KEN domain single-site mutants of full-length FLAG tagged-Ire1 were spotted on minimal medium supplemented with essential nutrients (SD) or medium containing 0.25 μg/ml tunicamycin. (Bottom panels) Western analyses of Ire1 expression in yeast. 30-μg of yeast whole-cell extracts, prepared as described previously (Kimata et al., 2004), were separated by SDS-PAGE and then immunoblotted using monoclonal anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma).

As was observed with the kinase domain interface mutants, the ribonuclease active site mutants blocked Ire1 function in yeast. Mutation of both the ordered and the disordered ribonuclease active site residues abrogated Ire1 function in yeast (Figure 5B and supplementary Figure 7). Together, our in vitro and in vivo mutational results provide compelling support to the notion that the concave surface on the KEN domain embodies the ribonuclease active site of Ire1.

ADP binding promotes Ire1cyto dimerization

Our structural and functional studies thus far indicate that as a ribonuclease, Ire1 functions as a dimer. To investigate the oligomerization state of Ire1cyto in solution, we performed analytical ultracentrifugation. In its apo form, Ire1cyto behaves as a homogeneous monomer in solution over all protein concentrations tested (6.1 to 24.6μM) (Supplementary Figure 8). In contrast, the solution behavior of Ire1cyto transitions to a monomer-dimer equilibrium in the presence of ADP with an approximate dissociation constant of 298μM. Since nucleotide potentiates the ribonuclease activity of Ire1, we reason that this phenomenon might reflect the ability of ADP to promote the specific dimer configuration of Ire1cyto we observe in the x-ray crystal structure.

Phosphorylation status regulates access of the kinase domain active site to nucleotide

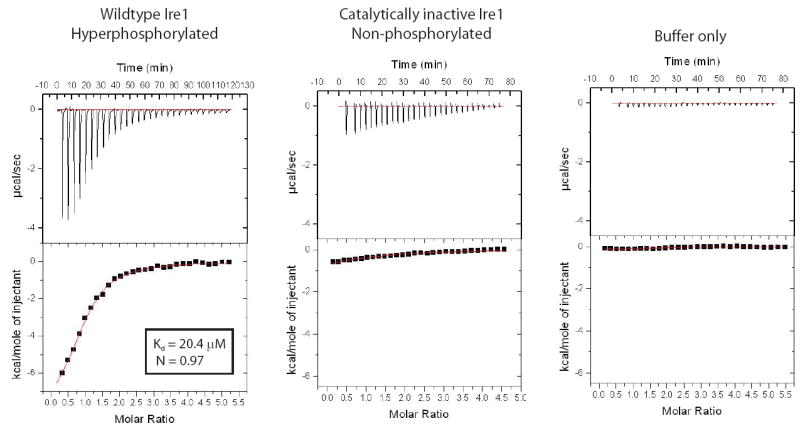

Given that nucleotide binding to the kinase domain appears to stimulate Ire1cyto dimerization, we asked whether nucleotide binding is a regulated process. Based on the ability of the activation segment to regulate access of nucleotide to the catalytic cleft of other protein kinases (Hubbard et al., 1994; Huse and Kuriyan, 2002), we performed isothermal titration calorimetry to test if activation segment phosphorylation regulates nucleotide access to the kinase domain. To do so, we compared binding of ADP to Ire1cyto in its hyperphosphorylated active state versus Ire1cyto in its non-phosphorylated state. We observed that hyperphosphorylated Ire1cyto displays a significant ADP binding signal (Kd ≈ 20.4 μM; N ≈1) while non-phosphorylated Ire1cyto and a buffer only control displayed no sign of saturable binding to ADP (Figure 6). From this data, we conclude that auto-phosphorylation, presumably on regulatory sites within the activation segment, serves to regulate access of the kinase domain active site to nucleotide binding.

Figure 6. Ire1 autophosphorylation enables nucleotide binding.

Isothermal titration calorimetry profiles obtained by titration of ADP against hyperphosphorylated wildtype Ire1cyto (left), a non-phosphorylated catalytically inactive Ire1cyto(D797A) mutant (middle), and protein buffer control (right). The dissociation constant (Kd) and stoichiometry (N) obtained by fitting to a one-site binding model for wildtype Ire1 are shown in inset.

Ribonuclease catalytic mechanism of Ire1

Our studies thus far have identified 10 of 458 residues in the minimal catalytic region of Ire1 that are surface exposed, highly conserved, clustered in space and required for the ribonucleolytic activity. Based on the likelihood that Ire1 and RNaseL share a common RNA cleavage mechanism, we reasoned that the residues directly involved in catalysis must be common to both enzymes. Only four residues in the Ire1 nuclease active site fulfill this requirement, namely Y1043, R1056, N1057, and H1061.

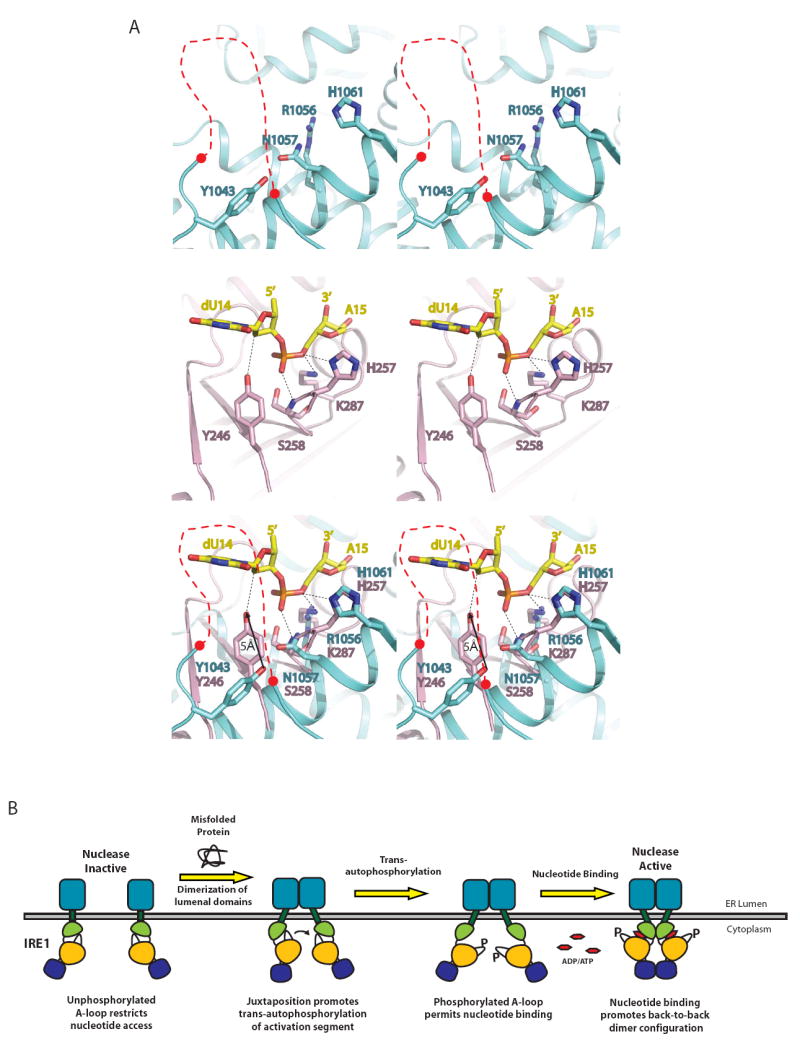

We next assessed whether this group of four residues in Ire1 bears geometric and chemical similarity to the catalytic residues in any of the 12 non-redundant ribonuclease folds represented in the protein data bank. Within this group of ribonucleases, the tRNA splicing endonuclease (PDB ID = 2GJW) displays a similar composition of catalytic residues, (Y246, S258, H257, K287) to the residues we identified for Ire1, despite a complete lack of similarity in their three-dimensional folds (Figure 7). Superposition of the catalytic residues in the tRNA endonuclease and Ire1 crystal structures reveals striking correspondence in both the chemical nature and spatial disposition of functional groups (Figure 7A, bottom panel), which allows us to infer the specific role of each of the four residues in the Ire1 catalytic cluster.

Figure 7. Convergent evolution of ribonuclease active site.

(A) Structural alignment illustrating concordance in the three-dimensional disposition of ribonuclease catalytic residues in Ire1 and tRNA endonuclease. Sidechains of catalytic residues in the KEN domain of Ire1 are colored blue and the conserved disordered linker connecting helices α3 and α4 is demarked as a red dashed line (top). Catalytic residues in the ribonuclease active site of a topologically disparate splicing ribonuclease – tRNA endonuclease (PDB ID = 2GJW) are shown in pink, while the bound RNA substrate analogue is colored in yellow (middle). For clarity, only the scissile phosphate and the flanking nucleotides are shown. RNA-protein interactions are indicated with black dashed lines. Functionally analogous residues in Ire1 (N1057, R1056 and H1061) and tRNA endonuclease (S258, R1056 and H257) align very well, with the exception of Y1043 in Ire1, which is displaced from the functionally equivalent Y246 in tRNA endonuclease by 5Å (bottom).

(B) Model of dimerization induced signaling by Ire1 across the ER membrane.

As shown in Figure 7A (bottom panel), the imidazolium ring of Ire1 H1061 aligns well with that of tRNA endonuclease H257, which serves as a general acid to protonate the 5’-OH leaving group (Xue et al., 2006). The sidechain amide nitrogen of N1057 in Ire1 aligns well with the backbone amide nitrogen of tRNA endonuclease S258, which positions the scissile phosphate for nucleophilic attack. The guanidinium group of Ire1 R1056 and the amino group of the tRNA endonuclease K287, which stabilizes the negatively charged transition state, are similarly disposed. Only the hydroxyl group of Y1043 is shifted 5Å from its expected postion relative to Y246 in tRNA endonuclease. Given that Y1043 resides within a flexible region of Ire1, we reason that Y1043 reorients to the position occupied by tRNA endonuclease Y246 to enable catalysis. Such a repositioning might occur as a result of Ire1 binding to RNA substrates. Consistent with the notion that Ire1 employs the same catalytic mechanism as tRNA endonuclease and other 2’-3’ cyclizing ribonucleases, wherein the 2’-OH group adjacent to the scissile phosphate plays a critical role in catalysis, substitution of the conserved guanosine 5’ to the scissile phosphate with deoxyguanosine completely abolishes cleavage of single hairpin substrates by Ire1 (Supplementary Figure 4B). Furthermore, Ire1 has also been reported to generate products bearing 2’-3’ cyclic phosphate termini (Gonzalez et al., 1999).

Discussion

Model of Ire1 regulation

Our results provide a basis for understanding how the protein kinase and ribonuclease activities of Ire1 are regulated and how the two distinct structural domains responsible for each activity are functionally interconnected (Figure 7B). In its resting state, Ire1 resides in a monomeric form, in part because the cytoplasmic and the ER luminal regions of the transmembrane receptor lack a strong ability to dimerize or are prevented from dimerizing in the absence of unfolded protein. In response to the accumulation of unfolded protein in the ER, the luminal domain of Ire1 tightly dimerizes (possibly oligomerizes) promoting the juxtaposition of two cytoplasmic kinase domains in a face to face manner that facilitates trans-autophosphorylation on regulatory sites within the activation segment. This post-translational modification provides unfettered access of the kinase domain to the binding of nucleotide which in turn enables a back-to-back dimer configuration involving discontinuous surfaces on the protein kinase and KEN domains. This mode of dimerization generates a large two fold symmetric catalytic surface on the base of the KEN domain that is fully competent for ribonuclease function.

Regulation of ribonuclease function by nucleotide binding

Protein kinase domains possess a bilobal architecture characterized by great interlobe flexibility (Huse and Kuriyan, 2002) that facilitates the exchange of ADP and phospho-protein products with ATP and protein reactants. As evidenced by crystallographic studies, the binding of nucleotide (ATP/ADP) to the catalytic cleft of protein kinase domains favours the adoption of a well defined closed conformation compatible with the phosphor-transfer mechanism (Huse and Kuriyan, 2002). In the Ire1cyto crystal structure, this same closed nucleotide bound conformation of the kinase domain appears conducive to dimer formation. Indeed, we show that ADP binding actually promotes the ability of Ire1cyto to form dimers in solution. Based on these observations, we reason that nucleotide binding stabilizes dimer formation by limiting the kinase domain from sampling alternate interlobe conformations that are incompatible with dimer formation. Since the degree of lobe closure is very similar for kinase domains when bound to ATP or ADP, this could explain why both molecules (and also non-hydrolysable analogues of ATP) can potentiate ribonuclease function (Sidrauski and Walter, 1997). We were able to reproduce the observation that ADP is a more potent stimulator than ATP (Sidrauski and Walter, 1997). If this reflects tighter binding of ADP versus ATP, we speculate that the presence of the gamma phosphate moiety to ATP creates greater electrostatic repulsion between the quadruplely phosphorylated A-loop than generated by ADP, and as a consequence lowers the binding affinity of ATP. This is manifested in the differential effect of ADP versus ATP on Ire1 ribonuclease function (Supplementary Figure 3D and (Sidrauski and Walter, 1997)).

Regulation of ribonuclease activity by the activation segment

The phosphorylation status of Ire1 affects its ability to bind nucleotide and nucleotide binding in turn promotes the ability of Ire1 to dimerize. By analogy to the insulin receptor kinase (Hubbard et al., 1994), we reason that the activation segment in its dephosphorylated state engages the active site of the kinase domain to inhibit nucleotide binding. This might occur in a manner that locks the two kinase lobes in a fixed orientation that is incompatible with dimerization or in a manner that accentuates inter-lobe flexibility. The latter might provide an entropic impediment to dimerization.

Interestingly, Papa et. al. demonstrated that the binding of the protein kinase inhibitor 1NM-PP1 to analogue sensitive forms of Ire1 had the effect of activating rather than inhibiting the downstream UPR signaling response. From this result, we reason that the 1NM-PP1 inhibitor must bind to the kinase domain of Ire1 in a manner that enforces a closed conformation of the kinase domain similar to the ATP/ADP bound state and thus promotes dimerization to activate ribonuclease function. If true, this raises the possibility that other kinase domain targeting inhibitors of Ire1 that enforce dimer-incompatible closure of the kinase domain might serve to inhibit Ire1 ribonuclease function. Presumably, the binding mode of 1NM-PP1 to Ire1 is sufficiently different from ADP that it is insensitive to the phosphorylation status of the activation segment and hence bypasses the need for auto-phosphorylation. Alternatively 1NM-PP1 might bind to Ire1 with sufficient affinity that it competitively displaces any inhibitory conformation of the activation segment.

Regulation of ribonuclease function by dimerization

The requirement of dimerization for Ire1 ribonuclease function suggests that certain functional determinants are supplied in trans from opposing protomers. Consistent with the notion that the core catalytic tetrad defining each ribonuclease active site is constituted in cis (Figure 7A), mixing of active site mutants did not restore nuclease activity (Supplementary Figure 9) We surmise that the functional component supplied in trans is represented by the substrate recognition infrastructure, which may be provided wholly or in part by opposing protomers in trans. Alternatively, if all functional determinants are self-contained within each protomer of Ire1, we surmise that dimerization serves to regulate each catalytic center through an allosteric mechanism.

Implications of twinned catalytic centers in the Ire1 nuclease active site

The Ire1 crystal structure reveals two catalytic centers symmetrically arrayed on adjacent KEN domains. Since the RNA hairpins recognized by Ire1 are paired in its physiological substrates (Mori, 2003), we reason that Ire1 may engage two hairpins cooperatively, perhaps as a mean to increase the affinity and specificity of the interaction. Indeed, this might explain why tandem hairpin substrates are more efficiently cleaved than single hairpin substrates (Gonzalez et al., 1999).

Since the two ribonuclease catalytic centers in the Ire1 dimer are related by two-fold rotation symmetry, we reason that cooperative substrate recognition may be achieved when the two hairpins in transcripts recognized by Ire1 are pre-ordered in a two-fold symmetric structure. Consistent with this possibility, the loop sequences of target hairpins are pseudo-palindromic and display striking potential to base pair when aligned in a staggered anti-parallel manner (Supplementary Figure 10A). This pattern is reminiscent of kissing hairpin structures, which contains dyad symmetry (Supplementary Figure 10B). An interesting feature of the kissing hairpin model is that it places the projected cleavage sites within adjacent hairpins in the same approximate distance of separation as the two catalytic centers of the KEN domain dimer (11.5Å in RNA model versus 13.5Å in KEN domain dimer). Close correspondence in the distance of separation between twinned RNA cleavage sites and twinned catalytic centers appears to be a requisite for substrate recognition by tRNA endonuclease (Supplementary Figure 10B and (Xue et al., 2006)). Further understanding of Ire1’s ribonuclease catalytic mechanism and the structural features of its RNA substrates that mediate recognition awaits the structure of Ire1 in complex with RNA.

Relevance to RNaseL

Ire1 and RNaseL compose a unique subfamily of proteins possessing a recognizable protein kinase domain and ribonuclease activity. The latter is attributable to the presence of the KEN domain in both proteins. The ribonuclease activity of both enzymes are regulated by dimerization, and potentiated by nucleotide binding (Credle et al., 2005; Dong et al., 1994; Sidrauski and Walter, 1997; Zhou et al., 2006). We anticipate that RNaseL will also adopt the same back-to-back dimer conformation in its active state. Similarly, we anticipate that nucleotide binding to the kinase domain of RNaseL promotes dimerization and hence ribonuclease activity through a common mechanism.

Unlike Ire1, RNaseL lacks protein kinase catalytic function and does not require auto-phosphorylation for the activation of its ribonuclease function (Dong et al., 1994). Based on sequence alignments (Figure 1), this might be explained by the complete absence of an activation segment in RNaseL. In contrast to Ire1, the absence of an activation segment would provide constitutive access of the kinase domain active site to nucleotide binding. Thus, the primary mode of regulation for RNaseL would lie at the level of dimerization which is promoted by the binding of virus induced second messengers, namely 2’-5’ oligo-adenylate polymers, to the N-terminal ankyrin repeat domain of RNaseL (Dong and Silverman, 1995).

RNaseL targets a distinct class of RNA substrates from those targeted by Ire1, cleaving singled stranded regions in both coding and non-coding RNAs (Floyd-Smith et al., 1981). We surmise that differences in substrate preferences between Ire1 and RNaseL are attributable in part to a disordered region connecting helices α3 and α4 in the KEN domain, whose sequence is unqiuely conserved in each group of enzymes. (Figure 1). Consistent with this possibility, we showed that the residues in the disordered region of Ire1 are essential for its ribonuclease function.

Comparison to PKR and relevance for pseudo-kinases

Despite close phylogenetic descent and similarity in the back-to-back dimer configuration adopted by Ire1 and PKR, the effect of dimerization on protein function is radically divergent. In the case of PKR, kinase domain dimerization allosterically upregulates phosphotransfer activity; in the case of Ire1, dimerization of the kinase domain simply serves as a scaffold to bring two adjacent KEN domains into a precise register that has no bearing on kinase activity. In the extreme case of the pseudo-kinase RNaseL, the kinase domain of RNaseL has completely lost phosphotransfer function. In this regard, the structure of Ire1cyto provides a basis for understanding the mechanism of action of other pseudo-kinases which represent 10% of the 518 protein kinases encoded in the human genome (Boudeau et al., 2006).

Recent studies have demonstrated frequent mutation of Ire1 in human cancer genomes (Greenman et al., 2007) as well as the direct involvement of the downstream target of Ire1, namely Xbp1, in the development of multiple myeloma (Carrasco et al., 2007). The work presented here provides a framework for dissecting the potentially complex relationship between Ire1 function and its role in disease such as cancer. Furthermore, this work sheds light on potential therapeutic avenues for the positive and negative manipulation of Ire1 signaling function.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification

Ire1cyto, and derivatives thereof, were recombinantly expressed from pProEx (Invitrogen) or pGEX-2T (Pharmacia) plasmids in E. coli BL21 cells as TEV protease-cleavable His-or GST-tagged fusions, respectively. Expressed proteins were bound to either Ni-NTA or glutathione Sepharose beads and eluted with imidazole, or by TEV protease treatment, respectively, and further purified by anion exchange (Q-Sepharose™) and size exclusion (Superdex™ 200) chromatography.

Crystallization, Data Collection, Structure Determination and Modeling

Ire1cytoΔ24 was produced as a His-tag fusion and labeled with seleno-methionine in BL21 CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene). Crystals were obtained in hanging drops containing purified Ire1cytoΔ24, and ADP mixed with an equal volume of well solution containing 50mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 200mM KOAc, 50mM SrOAc, 10mM MgCl2 and 10% PEG 8K. Crystals were cryoprotected with lower well solution supplemented with 30% ethylene glycol prior to flash freezing in liquid N2. A single anomalous dispersion experiment was performed on beamline 19-BM (Advanced Photon Source, Argonne, IL). SHELX D (Schneider and Sheldrick, 2002) was used to locate all 12 selenium sites. Phase extensions were performed with SHELX E (Debreczeni et al., 2003). Density modification and automated model building was performed using RESOLVE (Terwilliger, 2003). The final model was generated using a combination of manual adjustment (COOT -(Emsley and Cowtan, 2004)) and model refinement (REFMAC5 - (Vagin et al., 2004)) to a final resolution of 2.4 Å with Rwork=23.8% and Rfree=27.2%.

In vitro λPPase and RNA cleavage assays

The phosphorylation status of purified Ire1 proteins was assessed by incubation of ten-fold molar excess of Ire1 with λPPase in the presence of 0.1mM MnCl2 at 37°C followed by SDS-PAGE. For radiometric RNA cleavage assays, Xbp1mini (5’ GCGAAUUGGGUACCGUGGCGGCGCCUCCUGAGUCCGCAGCACUCAGACUCUCUGCACCUCUGCAGCAGGUGCAGGCGCC 3’) was transcribed in vitro from a T7 promoter and labeled with α-[32P]-CTP. For fluorescent RNA cleavage assays, single RNA hairpins containing a 5’-end fluorescein label were purchased from Dharmacon. Cleavage reactions were performed as described in (Gonzalez et al., 1999).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Equilibrium sedimentation and data analysis was performed as described in (Dey et al., 2005) using purified Ire1cyto prepared in 50mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.0), 20mM MgCl2, 20mM KCl, and 0.5mM TCEP in the absence or presence of 1mM ADP.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC was performed using a VP-ITC calorimeter (MicroCal). 2.5μM ADP, 100μM Ire1cyto, and 100μM Ire1cyto(D797A) were individually prepared in 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.0), 150 mM NaCl, 20mM MgCl2, 2mM DTT. The ADP solution was serially titrated into 1.35mL of Ire1 protein solution or buffer control using 28 consecutive 10μL injections at 240 second intervals at 20°C. Resultant binding isotherms were processed using MicroCal Origin 5.0 software. The final model was fitted to a one-site binding model.

Yeast experiments

The entire yeast IRE1 gene including 1-kb of 5’ and 0.3-kb of 3’ flanking sequence was amplified by PCR and cloned between the XhoI and EagI sites of the low copy-number LEU2 vector pRS315 generating pC3059. Plasmid pC3060 was derived from pC3059 by inserting a PstI site and FLAG epitope (DYKDDDDK) immediately before the IRE1 stop codon. Plasmids pC3061-pC3067 containing the IRE1 dimer-interface mutations R697A, R697D, D732R, D730A, D730R, R697D-D730R, and D723R-R730D, respectively, were generated in pC3060 by fusion PCR. Untagged versions of the IRE1 mutants were generated by transferring an NheI-SacI fragment carrying the mutations to pC3059. The nuclease active-site mutations were transferred from the E. coli expression vectors to pC3060 generating the low copy-number LEU2 plasmids pC2994-pC2997 and pC3032-pC3036 carrying the mutations Y1043A, R1056A, N1057A, H1061A, R1053E, D995A, L1037A, Y1040A, and R1041A, respectively. Mutant plasmids were introduced into yeast strain F862 (MATa his3-Δ1 leu2-Δ0 met5-Δ0 ura3-Δ0 ire1∷kanMX), obtained from the yeast genome deletion collection, and tested for growth on SD minimal medium supplemented with essential nutrients and 0.25 μg/ml tunicamycin.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratories, where diffraction data were collected. We thank Rick Collins and Duane Smith for helpful discussions during the preparation of this manuscript. We thank the members of the Sicheri laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute of Canada and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (F.S.) and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD (T.E.D.). F.S. is a recipient of a National Cancer Institute of Canada Scientist award.

Footnotes

Accession Number The coordinates reported herein have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the ID code 2RIO.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bernales S, Papa FR, Walter P. Intracellular Signaling by the Unfolded Protein Response. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.122303.120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudeau J, Miranda-Saavedra D, Barton GJ, Alessi DR. Emerging roles of pseudokinases. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:443–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, Till JH, Hubbard SR, Harding HP, Clark SG, Ron D. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature. 2002;415:92–96. doi: 10.1038/415092a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco DR, Sukhdeo K, Protopopova M, Sinha R, Enos M, Carrasco DE, Zheng M, Mani M, Henderson J, Pinkus GS, et al. The differentiation and stress response factor XBP-1 drives multiple myeloma pathogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Shamu CE, Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Credle JJ, Finer-Moore JS, Papa FR, Stroud RM, Walter P. On the mechanism of sensing unfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18773–18784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509487102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debreczeni JE, Bunkoczi G, Girmann B, Sheldrick GM. In-house phase determination of the lima bean trypsin inhibitor: a low-resolution sulfur-SAD case. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:393–395. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902020917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey M, Cao C, Dar AC, Tamura T, Ozato K, Sicheri F, Dever TE. Mechanistic link between PKR dimerization, autophosphorylation, and eIF2alpha substrate recognition. Cell. 2005;122:901–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Niwa M, Walter P, Silverman RH. Basis for regulated RNA cleavage by functional analysis of RNase L and Ire1p. Rna. 2001;7:361–373. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Silverman RH. 2-5A-dependent RNase molecules dimerize during activation by 2-5A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4133–4137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.8.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Xu L, Zhou A, Hassel BA, Lee X, Torrence PF, Silverman RH. Intrinsic molecular activities of the interferon-induced 2-5A-dependent RNase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14153–14158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd-Smith G, Slattery E, Lengyel P. Interferon action: RNA cleavage pattern of a (2’-5’)oligoadenylate--dependent endonuclease. Science. 1981;212:1030–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.6165080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay LM, Ng HL, Alber T. A conserved dimer and global conformational changes in the structure of apo-PknE Ser/Thr protein kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Biol. 2006;360:409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez TN, Sidrauski C, Dorfler S, Walter P. Mechanism of non-spliceosomal mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response pathway. Embo J. 1999;18:3119–3132. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, Dalgliesh GL, Hunter C, Bignell G, Davies H, Teague J, Butler A, Stevens C, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein AE, Echols N, Lombana TN, King DS, Alber T. Allosteric activation by dimerization of the PknD receptor Ser/Thr protein kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11427–11435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610193200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Sander C. Dali: a network tool for protein structure comparison. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:478–480. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard SR, Wei L, Ellis L, Hendrickson WA. Crystal structure of the tyrosine kinase domain of the human insulin receptor. Nature. 1994;372:746–754. doi: 10.1038/372746a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse M, Kuriyan J. The conformational plasticity of protein kinases. Cell. 2002;109:275–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00741-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata Y, Oikawa D, Shimizu Y, Ishiwata-Kimata Y, Kohno K. A role for BiP as an adjustor for the endoplasmic reticulum stress-sensing protein Ire1. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:445–456. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Tirasophon W, Shen X, Michalak M, Prywes R, Okada T, Yoshida H, Mori K, Kaufman RJ. IRE1-mediated unconventional mRNA splicing and S2P-mediated ATF6 cleavage merge to regulate XBP1 in signaling the unfolded protein response. Genes Dev. 2002;16:452–466. doi: 10.1101/gad.964702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madej T, Gibrat JF, Bryant SH. Threading a database of protein cores. Proteins. 1995;23:356–369. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K. Frame switch splicing and regulated intramembrane proteolysis: key words to understand the unfolded protein response. Traffic. 2003;4:519–528. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Ma W, Gething MJ, Sambrook J. A transmembrane protein with a cdc2+/CDC28-related kinase activity is required for signaling from the ER to the nucleus. Cell. 1993;74:743–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90521-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen B, Taylor S, Ghosh G. Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:661–675. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Lombardia M, Pompeo F, Boitel B, Alzari PM. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the PknB serine/threonine kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13094–13100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa FR, Zhang C, Shokat K, Walter P. Bypassing a kinase activity with an ATP-competitive drug. Science. 2003;302:1533–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1090031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamu CE, Walter P. Oligomerization and phosphorylation of the Ire1p kinase during intracellular signaling from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus. Embo J. 1996;15:3028–3039. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrauski C, Cox JS, Walter P. tRNA ligase is required for regulated mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1996;87:405–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81361-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrauski C, Walter P. The transmembrane kinase Ire1p is a site-specific endonuclease that initiates mRNA splicing in the unfolded protein response. Cell. 1997;90:1031–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC. SOLVE and RESOLVE: automated structure solution and density modification. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:22–37. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin AA, Steiner RA, Lebedev AA, Potterton L, McNicholas S, Long F, Murshudov GN. REFMAC5 dictionary: organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2184–2195. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Oligomerization and trans-phosphorylation of Ire1p (Ern1p) are required for kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18181–18187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue S, Calvin K, Li H. RNA recognition and cleavage by a splicing endonuclease. Science. 2006;312:906–910. doi: 10.1126/science.1126629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell. 2001;107:881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young TA, Delagoutte B, Endrizzi JA, Falick AM, Alber T. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis PknB supports a universal activation mechanism for Ser/Thr protein kinases. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:168–174. doi: 10.1038/nsb897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Liu CY, Back SH, Clark RL, Peisach D, Xu Z, Kaufman RJ. The crystal structure of human IRE1 luminal domain reveals a conserved dimerization interface required for activation of the unfolded protein response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14343–14348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606480103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.