Abstract

Protein-protein interaction is a common strategy exploited by enzymes to control substrate specificity and catalytic activities. RNA endonucleases, which are involved in many RNA processing and regulation processes, are prime examples of this. How the activities of RNA endonucleases are tightly controlled such that they act on specific RNA is of general interest. We demonstrate in this study that an inactive RNA splicing endonuclease subunit can be switched “on” solely by oligomerization. Furthermore, we show that the mode of assembly correlates with different RNA specificities. The recently identified splicing endonuclease homolog from Sulfolobus solfataricus, despite possessing all of the putatively catalytic residues, has no detectable RNA cleavage activity on its own but is active upon mixing with its structural subunit. Guided by the previously determined three dimensional structure of the catalytic subunit, we altered its sequence such that it could potentially self-assemble thereby enabling its catalytic activity. We present the evidence for the specific RNA cleavage activity of the engineered catalytic subunit and for its formation of a functional tetramer. We also identify a higher order oligomer species that possesses distinct RNA cleavage specificity from that of previously characterized RNA splicing endonucleases.

Keywords: Splicing endonuclease, enzyme oligomerization, substrate specificity, protein engineering, RNA cleavage

Introduction

Ribonucleases (RNases) cleave phosphodiester bonds in RNA and play essential roles in gene expression and regulation1-3. Processive and indiscriminate RNase activity leads to RNA decay, whereas discrete cleavage leads to mature functional RNA. Regardless of the cellular process, the control of RNA cleavage activity is of universal importance because reduced or aberrant cleavage of RNAs is potentially life threatening4-6.

RNases take multiple forms and act on a diverse range of RNA substrates. Consequently, the mechanisms by which RNases control their activity vary substantially. However, recent studies show that many RNases self-organize as multi-domains or multi-subunits to ensure concerted RNA degradation and processing activities. Extraordinary examples of such RNases include the bacterial degradosome and its eukaryotic homolog, the exosome1,7. Several recently determined cocrystal structures of individual riboendonucleases bound to their respective RNA substrates also reveal cooperativity between subunits. RNase E, a multi-functional endonuclease, forms a symmetric dimer; one of its subunits recognizes the 5′-terminal monophosphate, while the other cleaves the phosphodiester bond five bases away8. (RNase G, significantly similar in sequence to the nuclease/self-interaction domain of RNase E, relies upon dimer formation as well9.) RNase III is a dsRNA specific RNase that also exploits composite cleavage sites through dimerization10. Although definite structural evidence remains lacking, both RNase T and tRNase Z are thought to operate by a similar oligomerization mechanism11-13. The RNA splicing endonuclease, the subject of this study, excises phosphodiester bonds at two exon-intron junctions in precursor transfer and archaeal ribosomal RNAs. The eukaryotic enzyme, best characterized in yeast14-16, and the archaeal enzymes15,17 are believed to utilize composite cleavage sites through subunit assembly. Therefore, the assembly of subunits or domains in RNases serves to control their activity and specificity.

It is straightforward to demonstrate the necessity of enzyme assembly for RNA cleavage but it is often impossible to demonstrate that assembly is sufficient for accuracy. Limited by chemical equilibrium, mutations disrupting enzyme assembly reduce but do not eliminate the assembled species. In these cases, catalytic activity is detected at elevated enzyme concentrations9. As a result, enzyme assembly is known only as being necessary but not sufficient for RNA cleavage activity.

In this work, we have engineered a splicing endonuclease subunit which was inherently inactive due to lack of proper assembly and converted it into an active endonuclease with specific splicing activity. We used a recently characterized RNA splicing endonuclease subunit from Sulfolobus solfataricus as our model system. The functional S. solfataricus (Ss) endonuclease contains two subunits, α and β. The α-subunit used in this study possesses the catalytic residues, yet it is completely inactive alone18. The β-subunit has weak homology to the α-subunit,and contains no catalytic residues. Mixing the α- and β-subunits together in RNA cleavage reactions resulted in efficient activity. With no structural information on the functional enzyme, this new splicing endonuclease was tentatively classified as the (αβ)2 family18, reflecting the conserved architecture observed in two other families of archaeal endonucleases14,17. The crystal structure of the α-subunit was determined previously, which provided the structural basis for understanding its inability to cleave RNA but no conclusive insight on how the β-subunit positions the α-subunit in the active assembly18(Figure 1). Based on the structure of the inactive α-subunit alone, we now show that the α-subunit may be engineered into an endonuclease that possesses efficient and specific RNA cleavage activity in the absence of the β-subunit. This result suggests that the wild-type Ss endonuclease forms the same conserved architecture as other archaeal endonucleases and demonstrates the critical importance of enzyme assembly in controlling RNA cleavage activity.

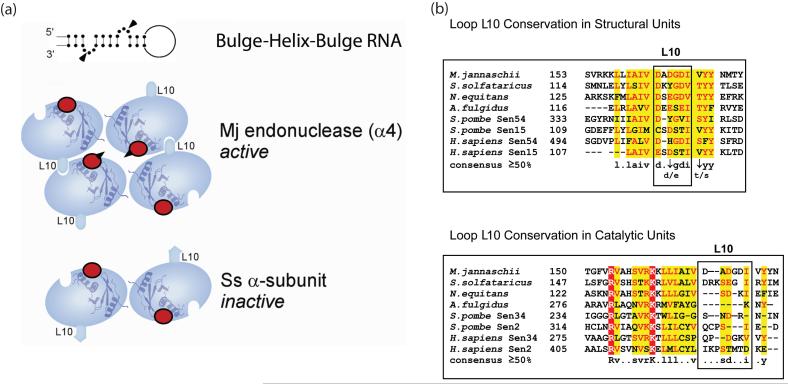

Figure 1.

Enzyme architecture and conservation of loop L10. (a) Comparison of the assembly between the Methanococcus jannaschii (Mj) endonuclease and Ss α-subunit. The top panel shows a schematic drawing of the Bulge-Helix-Bulge (BHB) RNA motif with arrowheads indicating where cleavage occurs. The bottom two panels illustrate the orientation of the catalytic sites (red circles) in the Mj endonuclease and Ss α-subunit relative to the bulges. All the catalytic sites are identical and indicated by red spheres. The sites that participate in cleavage (the two center sites in the Mj endonuclease) are indicated by arrow heads. (b) Sequence alignments of loop L10. Strong conservation is seen in loop L10 of enzyme structural units but not catalytic units.

Results

Protein engineering

The α-subunit of the Ss endonuclease, encoded by the ssendo1 gene, bears 37% sequence identity to the previously characterized Methanococcus jannaschii (Mj) splicing endonuclease monomer encoded by endA gene14. Despite the high degree of sequence homology, the two gene products differ completely in their quaternary structures and RNA cleavage activities (Figure 1). The Mj endonuclease, a homotetramer14, is active and specific for the natural RNA motif at the exon-intron junctions, while the Ss α-subunit forms a homodimer18 with no detectable RNA cleavage activity. These differing multimeric forms suggest that correct assembly is required for binding and cleaving the substrate RNA. Structural analysis indicates that a key element responsible for self-tetramerization in the Mj endonuclease is its acidic loop (L10) connecting the β9-β10 hairpin14. The process leading to a fully assembled tetramer is best described, although not yet verified experimentally, as a two-step assembly. One step is the formation of the tail-to-tail homodimer mediated by the last β-strand. The other is the further oligomerization through an electrostatic interaction between the negative L10 of one subunit and the positively charged pocket of an opposing subunit (Figure 1a). Despite the high degree of sequence homology to Mj endonuclease monomer, the loop L10 of the Ss α-subunit contains additional basic residues rendering its electrostatic properties unsuitable for tetramerization. Consequently, the loop-to-pocket interaction required for tetramerization cannot occur. As revealed by crystallographic and solution studies, the Ss α-subunit forms only the tail-to-tail interaction observed in the Mj endonuclease and is thus inactive18 (Figure 1a).

We hypothesize that L10 of the Ss α-subunit has evolved to relinquish its functional role as an assembly element. Instead, we propose that the β-subunit now fulfills this functional role and offers a structural adaptability to the α-subunit enabling it to bind to intron RNAs. Specifically, the β-subunit contains a highly conserved region that resembles the Mj endonuclease L10 sequence; this is the candidate assembly element. Figure 1b illustrates that the conservation of L10 is much stronger among structural units than among the catalytic units, which supports our hypothesis. To test whether this conserved sequence in the β-subunit facilitates Ss endonuclease assembly, we created an Ss α-subunit mutant, SSα_L10, that bears the L10 sequence of the Ss β-subunit in place of its own L10 sequence. The mutated sequences are shown in Figure 2a.

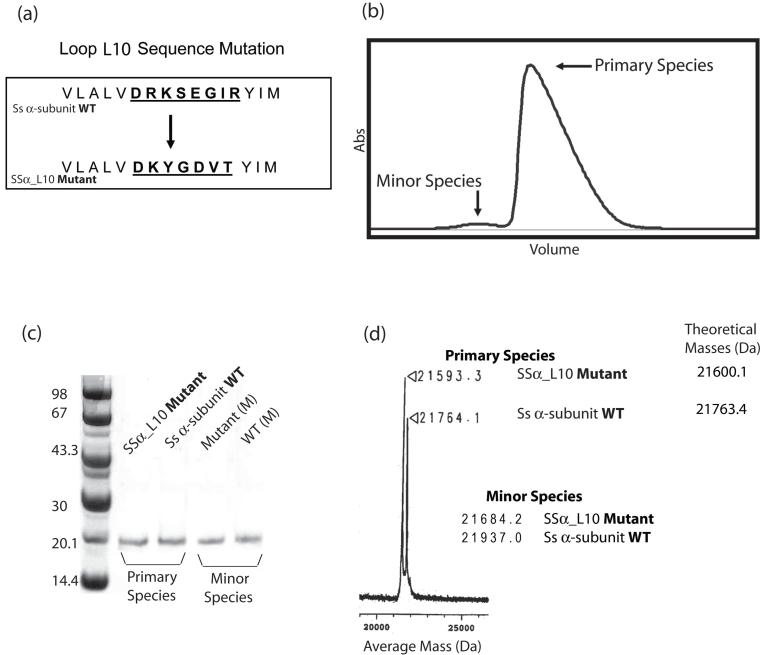

Figure 2.

Purified protein samples and verification of SSα_L10. (a) The loop L10 sequences of the Ss α-subunit before and after mutation. (b) Gel filtration profile of a typical Ss α-subunit purification. The SSα_L10 mutant profile is nearly identical. (c) 10% SDS-PAGE gel analysis of the primary and minor species of both wild-type and mutant proteins. (d) Mass spectrometry analysis of the wild-type and the mutant proteins. The spectrum illustrates average mass peaks for the primary species only, with mass values for both species shown to the right. The theoretical molecular weights are included for comparison.

The SSα_L10 mutant protein was expressed and purified following a protocol similar to that employed for the wild-type Ss α-subunit. Gel filtration profiles for wild-type and mutant samples were nearly identical and displayed predominantly one species (the primary species). However, a very small fraction of protein (the minor species) was eluted ahead of the primary species (Figure 2b). When analyzed by SDS-PAGE, both species contained a single band migrating at ∼21.7 kDa corresponding to the approximate molecular weight of the wild-type/mutant α-subunits (Figure 2c). Since the primary species comprises nearly 99% of the total protein, its RNA cleavage activity and oligomerization were analyzed first. We also characterized the RNA cleavage activity of the minor species, which will be described in later sections. In our subsequent discussions, we refer to the primary species as “Ss α-subunit” for the wild-type protein and “SSα_L10” for the mutant.

SDS PAGE analysis of SSα_L10 indicated that it was at least 98% pure (Figure 2c). In addition to DNA sequencing, mass spectrometry analysis confirmed the substitution of the amino acids in SSα_L10 (Figure 2d).

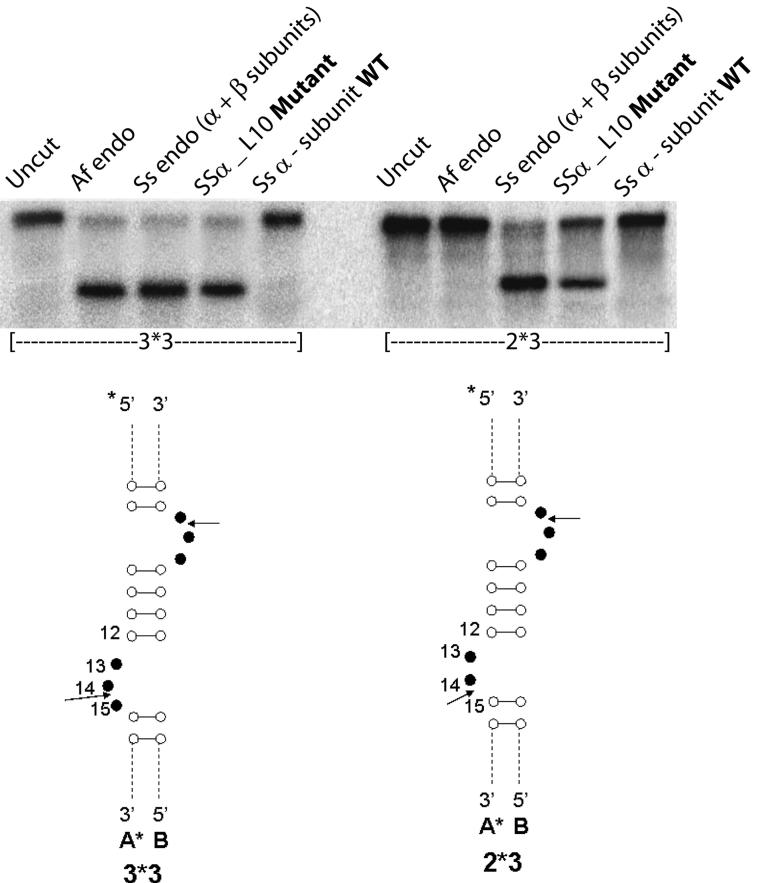

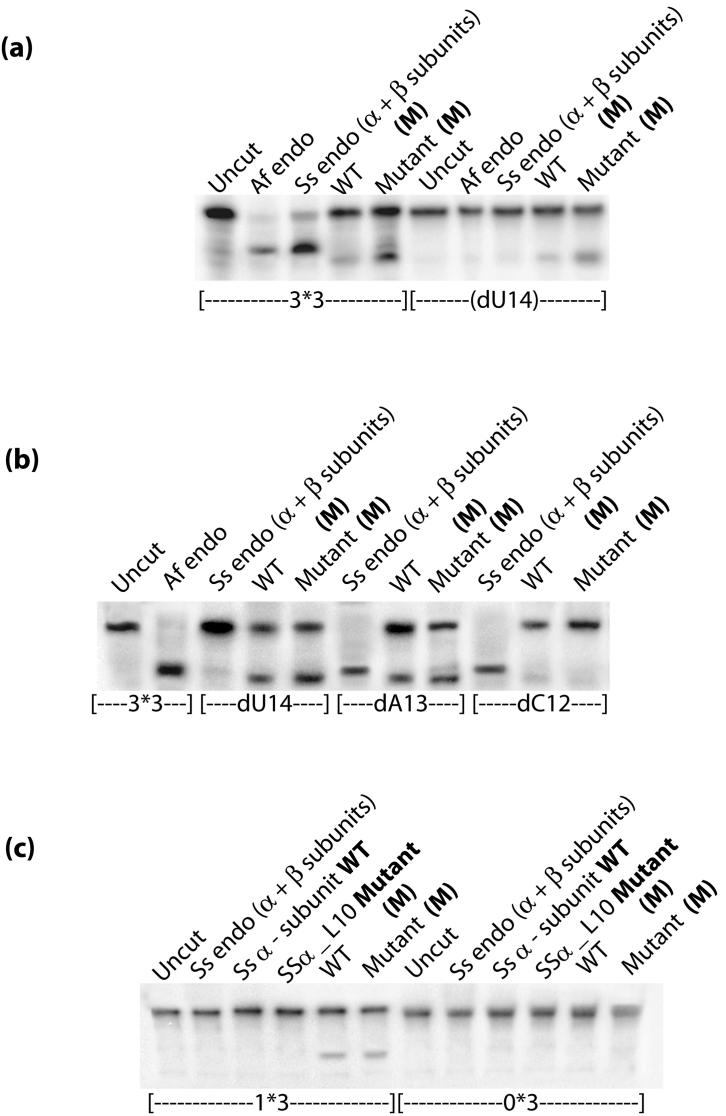

SSα_L10 cleaves BHB RNA specifically

We used the standard in vitro RNA cleavage assay to compare the RNA cleavage activity of SSα_L10 to that of the wild-type Ss α-subunit. The most common in vivo RNA substrate includes an RNA motif comprised of a pair of three-nucleotide bulges separated by a four base-pair helix called the “Bulge-Helix-Bulge” (BHB) motif, represented by our in vitro 3*3 substrate (Figures 1, 3, 4 and 6). Variations of the canonical BHB motif are also found in Archaea. Our 2*3 substrate represents an in vivo example of this, with one bulge having two bases and the other having three bases (Figure 3). We showed previously that the wild-type Ss endonuclease containing both α- and β-subunits is specific for both canonical BHB as well the relaxed BHB motifs18. 5′-radiolabeled BHB RNA substrates formed from annealed oligomers were incubated separately with SSα_L10, the wild-type Ss α-subunit, and another BHB cleavage endonuclease from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Af). Results presented in Figure 3 show that SSα_L10 efficiently cleaved the BHB RNAs and the wild-type Ss α-subunit did not. In order to ensure that SSα_L10 has the same specificity as a canonical splicing endonuclease, we mapped the site of cleavage by using 3*3 BHB substrates bearing 2′-deoxy substitutions at positions C12, A13 and U14. Based on the known specificity of the splicing endonucleases, nucleotide U14 of our 3*3 substrate contains the attacking nucleophile group and a 2′-deoxy modification at this nucleotide would inhibit its cleavage. Similar to the active Af endonuclease control, SSα_L10 was inhibited only by 2′-deoxy modification on U14 but not on A13 or C12 (Figure 4). Therefore, converting the Ss α-subunit into the SSα_L10 mutant produced a splicing endonuclease specific for cleavage at position 14, like a canonical splicing endonuclease.

Figure 3.

Evidence for RNA cleavage activity of the SSα _L10 Mutant. The gel shows that cleavage activity by SSα_L10 is quite similar to the active S. solfataricus enzyme, which is comprised of both α and β-subunits and labeled “Ss endo (α + β subunits).” Below are schematic drawings of the BHB motif region of the substrates, with arrows indicating the cleavage sites. Strand A is 5′-radioactively labeled and designated by an asterisk (*). Nucleotides 12, 13 and 14 are of special interest and explicitly labeled. The actual annealed oligomers in the 3*3 and 2*3 substrates contain the number of bases described in Materials and Methods.

Figure 4.

The SSα_L10 mutant is specific for Bulge-Helix-Bulge RNA. dU14, dA13 and dC12 denote a 2′-deoxy modification at positions 14, 13, and 12 respectively.

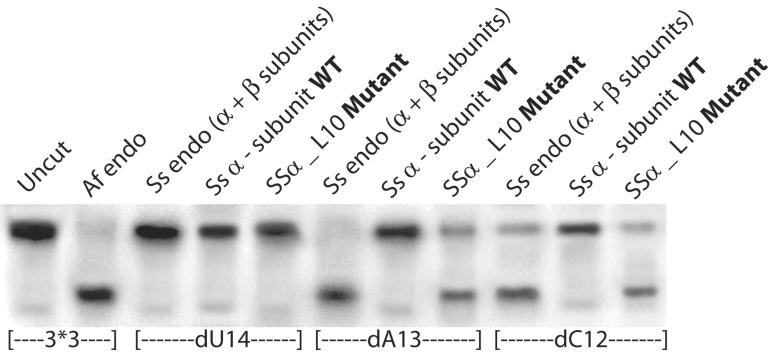

Figure 6.

Aberrant cleavage activity of the Ss α-subunit minor species. (a) RNA cleavage results indicating that the minor species cleaves at a different site than the primary species as indicated by cleavage of the BHB RNA deoxy modified at U14. (b) RNA cleavage results indicating that the minor species cleaves at position 12. (c) RNA cleavage results indicating that the minor species, but not the primary species, cleaves the 1*3 BHB RNA containing a one nucleotide bulge. No cleavage occurred on the 0*3 substrate, which is missing one bulge entirely.

SSα_L10 forms an active tetramer

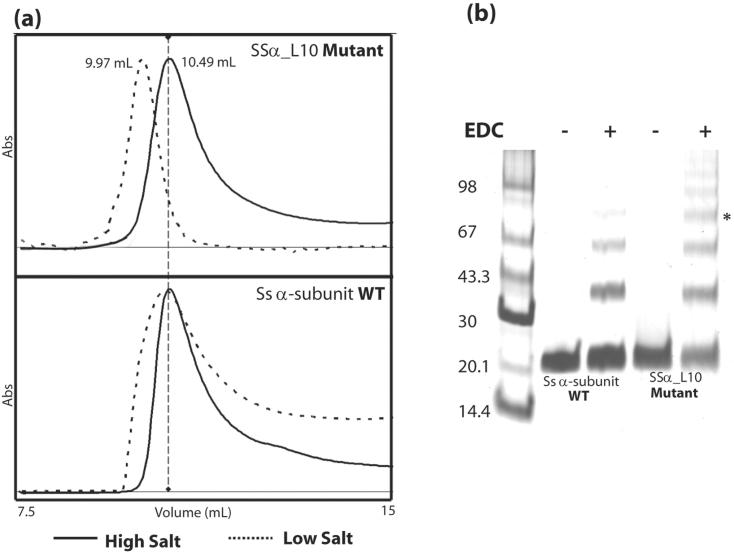

To provide evidence that the SSα_L10 mutant is assembled into an active tetramer while the wild-type Ss α-subunit remains a dimer, we performed analytic gel filtration experiments and protein cross-linking studies using purified protein samples. Because the loop-to-pocket interaction is electrostatic in nature14, we anticipated that the oligomerization mediated by L10 is sensitive to salt concentrations. Specifically, the strength of Columbic interactions between the acidic L10 and the basic pocket would be stronger at lower salt concentrations. Therefore, gel filtration chromatography was performed at various salt concentrations. As shown in Figure 5a, the elution profiles for SSα_L10 and the wild-type Ss α-subunit at 1 M NaCl are the same. However at low salt concentrations (50 mM NaCl), SSα_L10, but not the wild-type Ss α-subunit, displays a significant upward shift, which signifies the formation of a higher oligomer. Consistent with the physicochemical property of the loop-to-pocket interaction, this result indicates that in low salt SSα_L10 likely forms a tetramer while the wild-type Ss α-subunit remains a dimer.

Figure 5.

SSα_L10 mutant forms a tetramer in low salt conditions. (a) Comparison of analytical gel filtration profiles between SSα_L10 mutant (upper curve) and the Ss α-subunit WT protein (lower curve) in high salt (solid lines) and low salt (dashed lines) conditions. (b) Chemical crosslinking results with EDC. The asterisk marks the band corresponding to tetramers at 86.4 kDa.

Chemical cross-linking studies were also carried out to discern the oligomerization states of the wild-type and the mutant enzymes. We employed EDC (1-Ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide Hydrochloride) as the cross-linker which specifically reacts to carboxyl groups to form an amine-reactive O-acylisourea intermediate19 (Pierce Biotechnology, www.piercenet.com). In the presence of primary amines, the reaction proceeds to couple the carboxyl group to the primary amine, forming a stable amide bond. EDC-treated WT Ss α-subunit and SSα_L10 mutant were separated on a SDS-PAGE gel. As shown in Figure 5b, under the same cross-linking conditions, only SSα_L10 produced a clear cross-linked species corresponding to 86.4 kDa, the molecular weight of a tetramer. Previously, after long incubation times we observed a crosslinked tetrameric species in the WT Ss α-subunit with no cleavage activity (data not shown), suggesting the tendency for Ss α-subunit to form an inactive tetramer. From this evidence, together with the gel filtration results, we conclude that SSα_L10 is more susceptible to forming the tetramer believed to be responsible for RNA cleavage activity.

Enzyme assembly dictates substrate specificity

In the earlier section that describes purification of the Ss α-subunit, we described a portion of protein which eluted from the gel filtration column as a minor species. Mass spectrometry and SDS-PAGE gel analysis verified that these minor species contain primarily the WT or SSα_L10 endonuclease subunits (Figure 2d). The difference in masses between the primary and minor species is most likely attributable to the varied methods used to obtain data (See Materials and Methods).

We took fractions from both the wild-type and the L10 mutant proteins corresponding to this minor species and separately analyzed their RNA cleavage activity. We refer to these samples as WT (M) and Mutant (M). In both protein samples, this species efficiently cleaved the BHB RNA but at a distinctly different site. As seen in Figure 6a, the cleavage product migrated consistently faster than products from canonical cleavage activity. Using the same series of 2′-deoxy modified BHB RNA substrates, we found that cleavage by the minor species occurred at position C12, as seen in Figure 6b, rather than position U14, as was seen in Figure 4.

We further tested the ability of the minor species in cleavage of other relaxed RNA substrates. We found that the minor oligomeric species was able to process the 1*3 RNA containing a single bulge nucleotide as long as a three nucleotide bulge for the second cleavage site is also present. In contrast, the primary species of the Ss α-subunit and SSa_L10 were not able to cleave this unusual substrate (Figure 6c). No species were able to cleave the 0*3 substrate in which one bulge is missing entirely.

Since this cleavage activity occurs independently of L10 mutation by an enzyme oligomer distinct from that seen in the crystal structure (produced from the primary species), we hypothesize that this activity is due to an uncharacterized assembly of the Ss α-subunit. Assuming this alternatively assembled enzyme contains two concomitant active sites, the distance between the two sites would only be about 16 Å (the distance between the two equivalent C12 nucleotides), as opposed to the ∼28 Å distance observed between the canonical cleavage sites. Apparently, the minor species no longer maintains the conserved spacing between the two active sites. Although the precise mode of oligomerization giving rise to the alternative cleavage activity is unclear, this discovery demonstrates the possibility that alternative assembly from same catalytic components can alter enzyme specificity. To our knowledge, the minor species cleavage activity has not been reported in other splicing endonucleases.

Discussion

We have shown that endonucleases which are inherently inactive due to lack of proper assembly can be converted through protein engineering to have specific RNA cleavage activity. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the same endonuclease subunit can alternatively assemble and exhibit unusual RNA substrate specificity.

The splicing endonuclease is essential for the maturation of RNA molecules involved in protein synthesis. In this process, the endonuclease discriminates among all RNA encountered in the cell to cleave precisely and exclusively at its two splice sites. Our previous structural studies of a dimeric endonuclease17 revealed cooperative binding to canonical RNA substrates, however, the extent to which enzyme assembly impinged upon RNA cleavage activity was not known. This study unambiguously demonstrates that enzyme assembly is both necessary and sufficient for RNA cleavage, provided that individual subunits possess catalytic components. It is remarkable that by enabling tetramerization alone, a completely inactive splicing endonuclease subunit became active and specific. Our results reaffirm the critical importance previously proposed for loop L10 in the active assembly of all splicing endonucleases15. More importantly, these results explain the requirement for this assembly in the splicing endonuclease’s substrate recognition and cleavage.

This work suggests that differences in substrate specificity may be facilitated by different modes of enzyme assembly. The splicing endonuclease is a rapidly evolving enzyme, particularly in its mode of subunit assembly. In archaea alone, the splicing endonuclease varies from homodimers to homotetramers and heterotetramers, while maintaining the invariant catalytic components. Recent biochemical studies show that individual endonucleases exhibit unique RNA specificities dependent upon their mode of assembly. For instance, the αβγδ eukaryotic endonucleases can cleave nuclear pre-tRNA substrates, but can also cleave the minimal BHB motif14,20. To recognize pre-tRNA substrates, these enzymes require two distinct structural elements in RNA: 1) A conserved base pair between an anticodon and an intron nucleotide (A-I basepair), and 2) The presence of the mature domain of the precursor tRNA14. Euryarchaeal homomeric enzymes can only cleave the classical BHB motif, while the new (αβ)2 family of archaeal endonucleases, found in Crenarchaea and Nanoarchaea, is capable of excising a number of non-canonical BHB motifs18,21. We still do not know precisely how the β-subunit positions the α-subunit in the active (αβ)2 assembly. This work supports but does not prove the hypothesis that the conserved enzyme architecture previously observed14,17 applies to the (αβ)2 family. Crystal structures of a dimeric enzyme, alone and in complex with BHB RNA, show that the residues contacting the RNA are conserved in all splicing endonucleases. This raises the possibility that varied enzyme subunit arrangement may confer varied substrate specificity. The observation that modes of enzyme assembly are correlated with intron structures14,18,20,21 suggests that enzyme assembly is the most efficient means for adaptation.

Our results regarding the minor species fragment seen in both the wild-type and the mutant Ss α-subunit may have important implications for other endonucleases. On one hand, this alternatively assembled species could be an artifact of the in-vitro environment. However, it is also possible that in-vivo, for heteroassociated splicing endonucleases such as those of Crenarchaeota, N. equitans, and eukaryotes, individual catalytic subunits could potentially assemble on their own in a manner similar to the Ss α-subunit minor species and cleave RNA other than their known substrates.

Although demonstrated specifically by the RNA splicing endonuclease, these results underscore for RNases in general the power of enzyme assembly in controlling activity.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis and protein expression

The wild-type Loop 10 sequence of the Ss α-subunit, DRKSEGIR, was mutated to that of the Ss β-subunit, DKYGDVT, to create the SSα_L10 mutant. Two rounds of mutagenesis using the Quikchange Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA) were required to achieve substitution of the DNA sequence corresponding to this region. Protein expression and purification was carried out as previously described for the wild-type subunit18.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis

Dilute primary species samples were dialyzed into a 20 mM MES pH 7.5 buffer containing no salt and concentrated to 3 mg/mL. Apomyoglobin at 3 mg/ml was used for internal calibration and 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (sinapinic acid) was the matrix. Data were collected using a Bruker MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer and analyzed with the Biflex III_MALDI imaging system_and XMASS/XTOF analysis program (Bruker Daltronics, Billerica, MA). Dilute minor species samples were concentrated and prepared for analysis using ZipTip pipette tips (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Apomyoglobin and aldolase were internal calibrants and 2-(4-hydroxyphenylazo)benzoic acid (HABA) was the matrix. Data were collected using an Axima CFR-plus MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer and analyzed with the Kompact Launchpad software package (Kratos Analytical/Shimadzu Corporation, Chestnut Ridge, NY).

Cleavage activity assays

RNA oligomers were obtained from Dhamarcon (Lafayette, CO) and deprotected/purified following manufacture’s protocols. Strand A, bearing the 5′ cleavage site, was radioactively labeled by 5′-phosphorylation using 32P-γ-ATP (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). The sequences of the 21-oligomer strands comprising the 3*3 substrate are 21A: 5′-AAGCGACCGACCAUAGCUGCA-3′ and 21B: 5′-AAUGCAGCGGUCAAAGGUCGC-3′ (bulge nucleotides are in bold face type). Strand 20A, used in the 2*3 substrate, is identical to 21A with the exception of a deleted bulge nucoeotide (U). Strand 19A in the 1*3 substrate contains a single A bulge nucleotide and is otherwise identical to 21A. Strand 18A in the 0*3 substrate has no bulge. Deoxy modifications to positions C12, A13 or U14 were made to Strand 21A and used in 3*3 substrates as indicated. Splicing reactions were carried out at 60°C for 30 minutes in a reaction buffer containing 40mM Tris pH 7.4, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA and 1X RNase inhibitor. Final protein concentrations were 0.75 μM in all splicing reactions. Cleavage products were separated on a 10% denaturing acrylamide gel and visualized by phosphorimaging using the Molecular Dymanics Storm 860 Scanner and ImageQuant analysis software (GE Healthcare).

Analytical gel filtration analysis

A Superdex 75 10/30 column was pre-equilibrated with a high or low salt buffer on an AKTA Prime FPLC instrument (GE Healthcare). The high salt concentration was 400 mM NaCl and the low salt concentration was 50 mM NaCl. 100 μL samples from purified proteins were then injected to the column and eluted fractions were analyzed using the Unicorn Prime Evaluation analysis software. SSα_L10 mutant concentrations were 2.0 mg/mL and wild-type Ss α-subunit concentrations were 3.9 mg/mL. Normalized elution profiles are displayed in Figure 6a.

Chemical crosslinking

SSα_L10 and Ss α-subunits were separately incubated at 0.5 mg/mL with 30 mM EDC (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford IL) in a buffer containing 0.1 M MES pH 5.0 and 0.25 M NaCl. One-step reactions with and without EDC were carried out at room temperature for 30 minutes. Cross-linked samples were run on an 8% SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Comassie blue.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by a National Science Foundation grant (0517300) (H.L) and American Heart Association Pre-Doctoral Fellowship (0415091B) (K.C.). We thank the members of the Li Lab for helpful discussions, Drs. R. Dhanarajan, M. Seavy, U. Goli, and D. Terry for technical advice and expertise.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Buttner K, Wenig K, Hopfner KP. Structural framework for the mechanism of archaeal exosomes in RNA processing. Mol Cell. 2005;20:461–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutscher MP. Degradation of RNA in bacteria: comparison of mRNA and stable RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:659–66. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholson AW. Function, mechanism and regulation of bacterial ribonucleases. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:371–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiang Y, Wang Z, Murakami J, Plummer S, Klein EA, Carpten JD, Trent JM, Isaacs WB, Casey G, Silverman RH. Effects of RNase L mutations associated with prostate cancer on apoptosis induced by 2′,5′-oligoadenylates. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crow YJ, Leitch A, Hayward BE, Garner A, Parmar R, Griffith E, Ali M, Semple C, Aicardi J, Babul-Hirji R, Baumann C, Baxter P, Bertini E, Chandler KE, Chitayat D, Cau D, Dery C, Fazzi E, Goizet C, King MD, Klepper J, Lacombe D, Lanzi G, Lyall H, Martinez-Frias ML, Mathieu M, McKeown C, Monier A, Oade Y, Quarrell OW, Rittey CD, Rogers RC, Sanchis A, Stephenson JB, Tacke U, Till M, Tolmie JL, Tomlin P, Voit T, Weschke B, Woods CG, Lebon P, Bonthron DT, Ponting CP, Jackson AP. Mutations in genes encoding ribonuclease H2 subunits cause Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and mimic congenital viral brain infection. Nat Genet. 2006;38:910–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levinger L, Morl M, Florentz C. Mitochondrial tRNA 3′ end metabolism and human disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5430–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conti E, Izaurralde E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: molecular insights and mechanistic variations across species. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:316–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callaghan AJ, Marcaida MJ, Stead JA, McDowall KJ, Scott WG, Luisi BF. Structure of Escherichia coli RNase E catalytic domain and implications for RNA turnover. Nature. 2005;437:1187–91. doi: 10.1038/nature04084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briant DJ, Hankins JS, Cook MA, Mackie GA. The quaternary structure of RNase G from Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1381–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gan J, Tropea JE, Austin BP, Court DL, Waugh DS, Ji X. Structural insight into the mechanism of double-stranded RNA processing by ribonuclease III. Cell. 2006;124:355–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel A, Schilling O, Spath B, Marchfelder A. The tRNase Z family of proteins: physiological functions, substrate specificity and structural properties. Biol Chem. 2005;386:1253–64. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zuo Y, Deutscher MP. Mechanism of action of RNase T. I. Identification of residues required for catalysis, substrate binding, and dimerization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50155–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuo Y, Deutscher MP. Mechanism of action of RNase T. II. A structural and functional model of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50160–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207707200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abelson J, Trotta CR, Li H. tRNA splicing. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12685–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Trotta CR, Abelson J. Crystal structure and evolution of a transfer RNA splicing enzyme. Science. 1998;280:279–84. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trotta CR, Paushkin SV, Patel M, Li H, Peltz SW. Cleavage of pre-tRNAs by the splicing endonuclease requires a composite active site. Nature. 2006;441:375–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue S, Calvin K, Li H. RNA recognition and cleavage by a splicing endonuclease. Science. 2006;312:906–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1126629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calvin K, Hall MD, Xu F, Xue S, Li H. Structural characterization of the catalytic subunit of a novel RNA splicing endonuclease. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:952–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grabarek Z, Gergely J. Zero-length crosslinking procedure with the use of active esters. Anal Biochem. 1990;185:131–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90267-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabbri S, Fruscoloni P, Bufardeci E, Di Nicola Negri E, Baldi MI, Attardi DG, Mattoccia E, Tocchini-Valentini GP. Conservation of substrate recognition mechanisms by tRNA splicing endonucleases. Science. 1998;280:284–6. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randau L, Calvin K, Hall M, Yuan J, Podar M, Li H, Soll D. The heteromeric Nanoarchaeum equitans splicing endonuclease cleaves noncanonical bulge-helix-bulge motifs of joined tRNA halves. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17934–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]