Abstract

Animals and plants respond to bacterial infections and environmental stresses by inducing overlapping repertoires of defense genes. How the signals associated with infection and abiotic stresses are differentially integrated within a whole organism remains to be fully addressed. We show that the transcription of a C. elegans ABC transporter, pgp-5 is induced by both bacterial infection and heavy metal stress, but the magnitude and tissue distribution of its expression differs, depending on the type of stressor. PGP-5 contributes to resistance to bacterial infection and heavy metals. Using pgp-5 transcription as a read-out, we show that signals from both biotic and abiotic stresses are integrated by TIR-1, a TIR-domain adaptor protein orthologous to human SARM, and a p38 MAP kinase signaling cassette. We further demonstrate that not all the TIR-1 isoforms are necessary for nematode resistance to infection, suggesting a molecular basis for the differential response to abiotic and biotic stress.

Keywords: C. elegans, P. aeruginosa, innate immunity, stress, cadmium, infection, P-glycoprotein

INTRODUCTION

In the soil, Caenorhabditis elegans contacts with natural toxins and must defend against potentially pathogenic microorganisms that constitute its food. To defend against pathogens, C. elegans uses an immune system that is regulated by several signaling pathways, including the TGF-β [1], insulin [2] and p38 MAPK pathways. [3]. Phosphorylation of the p38 MAPK, PMK-1 and nematode resistance to pathogens requires the evolutionarily conserved protein TIR-1 [4; 5]. To resist environmental toxins, such as heavy metals, C. elegans utilizes strategies ranging from avoidance to detoxification. Evolutionary conserved signaling pathways, like JNK and p38 MAPK, regulate resistance to these stresses [6; 7]. Interestingly, the p38 MAPK pathway is required for resistance to toxins and nematode immunity [6; 8].

P-glycoproteins (PGP) represent an evolutionary well-conserved sub-group of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that protect cells by actively exporting drugs and toxins [9]. The C. elegans genome encodes 15 PGP proteins [10]. Athough present in almost every tissue [11], the functions of only 3 have been determined. pgp-2 is expressed in the intestine and is required for acidification of lysosomes and lipid storage [12]. pgp-1 and pgp-3 are necessary to resist phenazine toxins secreted by the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa [13], and contribute to heavy metals and drugs resistance [14; 15].

Although signaling cascades necessary for the nematode resistance to infection and stresses have been identified and transcriptional responses to these stresses have been studied at the whole genome level [16; 17; 18; 19], much remained to be elucidated about how specific downstream effectors are regulated. Moreover, it is not known whether the signaling modules regulating nematode immunity act independently or are part of a global regulation network that integrates the responses to pathogens and stress, as previously suggested [20].

We showed that the C. elegans P-glycoprotein gene pgp-5 is induced upon exposure to heavy metals and bacterial pathogens and is necessary for full resistance to these treatments. By investigating the regulation of pgp-5 expression, we found that the axis defined by TIR-1-p38 MAPK module plays a significant role in integrating the signals from both biotic and abiotic stresses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Infection and toxicity assays

Infection assays were performed as described [17]. For toxicity assays, three 1-day-old adult hermaphrodites were deposited on plates seeded with OP50 and allowed to lay eggs for 4–5 h. After the parents were removed, the eggs were counted and the plates incubated for 3 days at 20ºC. The percentage of adults was calculated as the total number of adults divided by the total number of eggs. Each test was performed at least twice with 4 replicates per condition.

RNAi and qRT-PCR experiments

RNAi and qRT-PCR experiments were performed as described [17], and detailed in Supplemental Materials and Methods. After 24 h treatment, animals were either collected for microscopy, COPAS analysis or RNA preparation. The identity of dsRNA-expressing bacteria (Geneservice, UK) was confirmed by sequencing or restriction digest.

Statistical analysis

For survival analysis, StatView and Prism softwares were used to calculate the mean time to death (TDmean) and the Kaplan-Meier Log rank test assessed the similarity between survival curves. Student’s t-tests were calculated using Microsoft Excel. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Transcription of pgp-5 is induced during infection and heavy metal stress

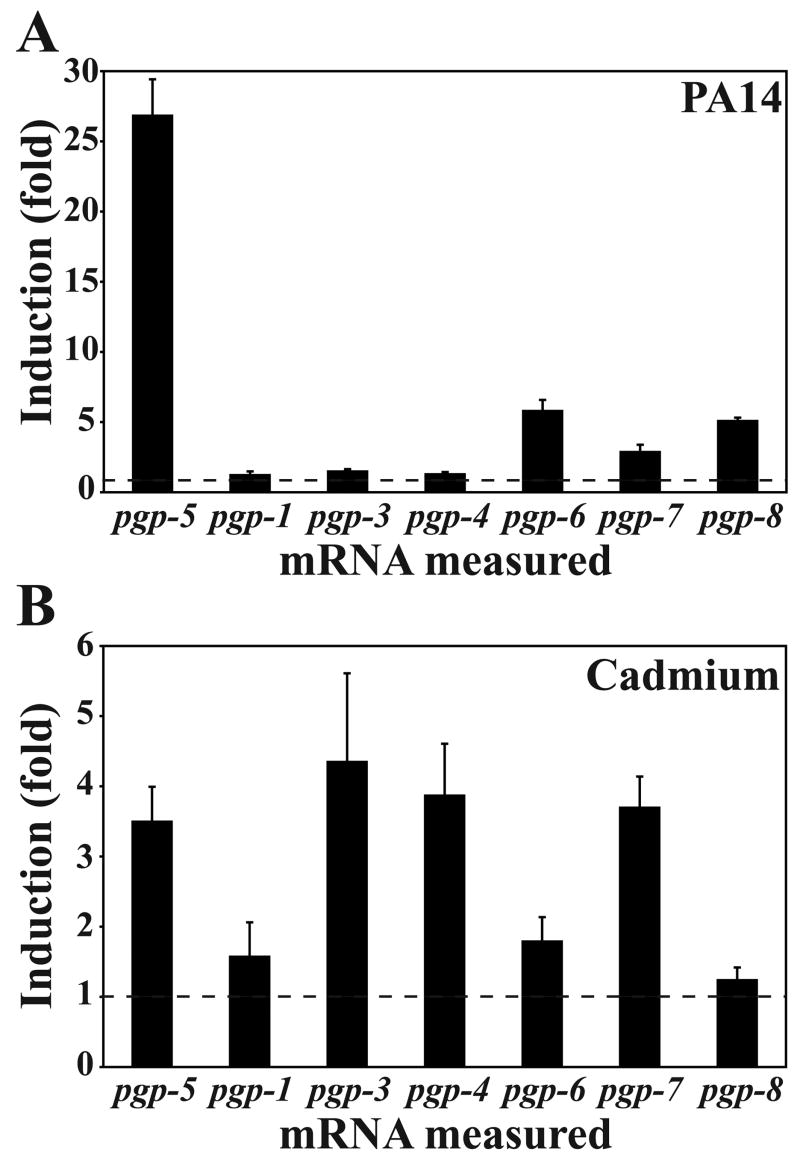

In whole-genome microarray experiments, expression of pgp-5 was among the most highly induced in response to intestinal infection by P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (hereafter referred to as PA14) [17; 18]. To confirm and extend these observations, we measured the mRNA levels of pgp-5 and additional pgp genes upon PA14 infection and exposure to heavy metals by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). We included pgp-1 and pgp-3 for their known function in resistance to PA14 toxin [13], pgp-4 because it is adjacent to pgp-3, and a cluster composed of pgp-5, pgp-6, pgp-7 and pgp-8 (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Following infection or exposure to cadmium, pgp-5 was the only tested gene induced by at least 3-fold in both conditions (Fig. 1A and 1B). We chose pgp-5 for further analyses because its robust induction by both infection and cadmium presents the opportunity to study how responses to biotic and abiotic stresses are integrated in a whole organism.

Figure 1. mRNA levels of pgp genes in PA14-infected and cadmium-exposed animals.

mRNA level measured by qRT-PCR after exposure to PA14 (A) or OP50 with 50 μM CdCl2 in the media (B) for 24 h at 25ºC. Fold induction corresponds to the ratio between mRNA levels from animals under test conditions and mRNA levels from animals on OP50. Error bars correspond to standard deviation from 3 replicates in the same experiment. Each graph is representative of at least two independent experiments. Dotted line represents the basal expression on OP50.

The magnitude and tissue distribution of pgp-5 expression in response to infection and environmental insults are different

To determine if the response of pgp-5 to different forms of stresses differs in tissue expression, and to confirm the observed difference in magnitude, we monitored the expression of green fluorescence protein (GFP) in ppgp-5::gfp transgenic animals. The ppgp-5::gfp reporter strain contains an integrated transgene, ppgp-5::gfp, in which the GFP-encoding gene is under the control of the 300 bp upstream sequence of the pgp-5 promoter (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Under standard growth conditions, green fluorescence was undetectable at low magnification (25X) and was detected at a very low level throughout the intestine (Supplemental Fig. 2A) at high magnification (200X) in the majority of adult animals. Consistent with microarray and qRT-PCR data, we observed a very strong increase of green fluorescence in the intestine of PA14-infected worms (Supplemental Fig 2B), and quantified fluorescence related to pgp-5 induction with the COPAS worm sorter (Supplemental Fig 2D). pgp-5 expression was also induced in the intestine of animals infected with pathogenic Salmonella typhimurium, Serratia marcescens or Staphylococcus aureus, but not in worms fed on the non-pathogenic Bacillus subtilis (Supplemental Table 2).

Heavy metals, such as cadmium robustly induced the pgp-5 transcription in intestinal cells of adults (Supplemental Fig. 2C and D). In addition to the intestinal expression, majority of cadmium-treated animals expressed the transgene in the terminal bulb of the pharynx (80%, n = 59, Supplemental Fig. 2C). In contrast, only 14% (n = 74) of PA14-infected animals had detectable transgene expression in the pharynx. Copper, colchicine and zinc also potently induced pgp-5 expression (Supplemental Table 2). In general, pgp-5 expression was robustly induced in the intestinal cells of animals exposed to diverse pathogenic bacteria, but the induction was more moderate in animals exposed to several abiotic noxious molecules.

PGP-5 is necessary for full resistance to heavy metals and bacterial infections

The increase in pgp-5 transcription in response to bacterial infections and toxic compounds suggested that PGP-5 could be involved in protection from these insults. We tested this possibility by analyzing the pgp-5(ok856) mutant, in which a 1 kb region, including exons 11 to 13 that encode the second transmembrane domain is deleted (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Under standard culture conditions, the pgp-5(ok856) mutant was phenotypically wild-type.

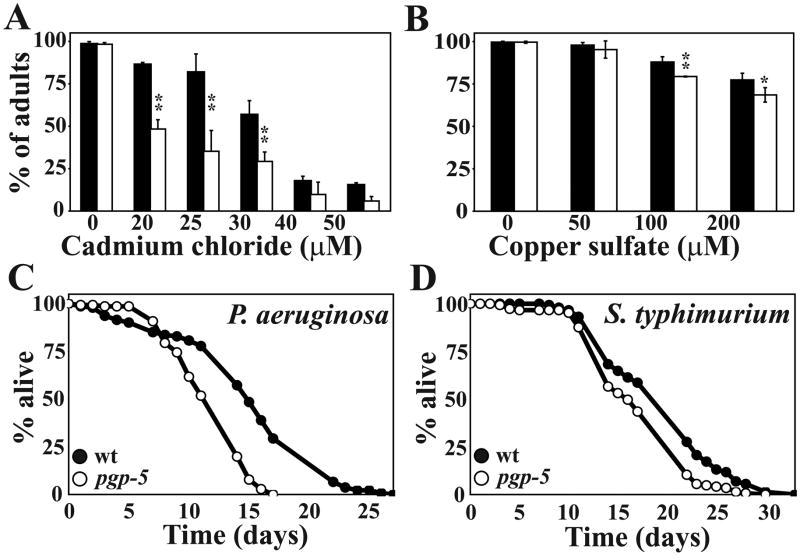

We assayed the effects of different toxic compounds on the developmental rate of pgp-5 mutant animals at a range of concentrations. In the absence of toxic molecules in the media, the N2 and pgp-5 mutant worms developed at the same rate: close to 100% of the eggs developed into adults in 3 days at 20°C (Fig. 2A–B, the “0” columns). At concentrations of cadmium chloride and copper sulfate in which development of wild type animals was impaired, the proportions of pgp-5 animals with developmental delay were significantly higher (Fig. 2A and B). No significant difference between wild type and pgp-5 was observed on colchicine and sodium arsenite at all test concentrations (Supplemental Fig. 3A and B). We therefore conclude that pgp-5 is required for C. elegans’ full resistance to cadmium and copper.

Figure 2. The pgp-5 mutant is susceptible to heavy metals and bacterial infection.

Percent of N2 (closed bars) and pgp-5(ok856) mutant (open bars) to develop from eggs to adults in the presence of (A) CdCl2 and (B) CuSO4. The number of animals quantified from left to right were in (A) 351, 521, 715, 607, 641, 578, 444, 634, 769, 529, 325, 491, and in (B) 162, 135, 500, 470, 446, 449, 485, 493. Representatives of at least two independent experiments are shown. * represents p < 0.05 and ** represents p < 0.0001 by Student’s t-test. (C and D) Survival of N2 (closed circles) and pgp-5(ok856) mutant (open circles) infected with P. aeruginosa PA14 (C) or S. typhimurium SL1344 (D).

We next asked if pgp-5 is required to protect C. elegans from bacterial infections by determining the TDmean of worms infected with PA14 or S. typhimurium SL1344. No significant difference in survival could be detected between wild type and pgp-5 mutants on PA14 (TDmean of 3.15 ± 0.05 days and 3.25 ± 0.05 days, respectively; Log rank test, p > 0.11) and SL1344 (TDmean of 9.4 ± 0.6 days and 10.1 ± 0.5 days, respectively; Log rank test, p > 0.07) when the assays were carried out at 25°C. Because small differences in resistance to bacterial pathogens could be better resolved when infections are carried out at a lower temperature [21], we repeated the infection assays at 15°C. At 15°C, wild-type nematodes infected with PA14 had a TDmean of 13.5 ± 1.7 days, whereas the TDmean for pgp-5 was 10.9 ± 1.0 days (Fig. 2C, Log rank test p < 0.0001). Similarly, pgp-5 worms infected with SL1344 were significantly more susceptible than wild-type animals, with a TDmean of 16.7 ± 1.0 days, and 19.3 ± 0.5 days, respectively (Fig. 2D, Log rank test, p < 0.001). Importantly, the lifespan of the pgp-5 mutants cultivated on the innocuous E. coli strain OP50 was not different from that of N2 animals at 25°C (data not shown) nor at 15°C (Supplemental Fig. 3C). Together, the results indicate that PGP-5 has modest but detectable roles in providing full protection from bacterial infection and a subset of toxic chemicals.

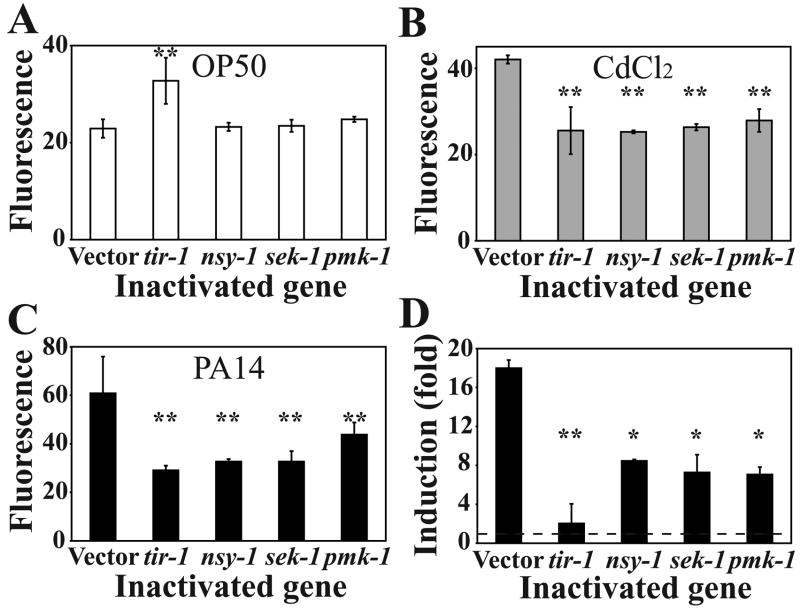

The induction of pgp-5 in response to infection and heavy metal requires TIR-1 and the p38 MAP kinase signaling cascade

The pgp-5 transgenic reporter strain allows us to visualize and quantify pgp-5 induction. Combined with gene knock down by RNAi at later larval stages, thereby avoiding potentially confounding effects of developmentally important genes, this represents a powerful tool to identify in vivo regulatory elements that control pgp-5 expression. Initially, we focused on the nsy-1/sek-1/pmk-1 p38 MAPK cascade, because this module is important for defense against both infection and abiotic stresses [3; 7], and on tir-1, an upstream component of the p38 MAPK pathway in C. elegans immunity [5]. With the exception of tir-1, RNAi knock down of nsy-1, sek-1 and pmk-1 did not significantly affect the basal expression of pgp-5 (Fig. 3A). Increased fluorescence in tir-1 RNAi-treated animals was due to a specific, but yet unexplained, increase in reporter gene expression in the pharynx (Supplemental Fig. 4). By contrast, knockdown of tir-1 or each member of the nsy-1/sek-1/pmk-1 module significantly reduced pgp-5 induction in ppgp-5::gfp worms compared to control animals following cadmium exposure (Fig. 3B) and PA14 infection (Fig. 3C). We confirmed the requirement for tir-1 and the nsy-1/sek-1/pmk-1 module for pgp-5 induction during PA14 infection by qRT-PCR (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. The p38 MAPK signaling cascade and TIR-1 are required for pgp-5 induction upon bacterial infection and cadmium exposure.

COPAS biosort quantification of green fluorescence in ppgp-5::gfp animals treated with a given dsRNA followed by exposure to either OP50 (A), 100 μM CdCl2 (B) or PA14 (C). Column represents mean ± SD of green fluorescence in arbitrary, but constant units. For each bar from left to right, the total number of animals tested (n) from two independent experiments were: (A), n = 645, 290, 1213, 918 and 460, in (B), n = 548, 784, 449, 403, and 813, and in (C), n = 346, 598, 784, 410 and 390. (D) Effect of dsRNA-treatment (x-axis) on fold induction of pgp-5 by PA14 infection (y-axis) as determined by qRT-PCR. Column represents mean ± SD of fold induction, which is the ratio of mRNA levels between animals infected with PA14 and animals fed with OP50. Representative of 2 independent experiments, each with 3 replicates, is shown. Dotted line in (D) represents the basal expression level on OP50. * represents p < 0.01 and ** represents p < 0.0001 by Student’s t-test.

Next we tested two other MAPK pathways, ERK and JNK. ERK contributes to resistance to rectal infection by M. nematophilum [22], and JNK is required for resistance to heavy metal stress [7]. dsRNA knockdown of mpk-1 (ERK) and mek-1 and kgb-1 (JNK) did not significantly affect the basal expression nor the induction of pgp-5 in response to infection or cadmium stress (Supplemental Fig. 5A–C). Two additional immunity pathways, the TGF-beta [1] and insulin pathways [2], also did not affect pgp-5 induction upon infection (see Supplemental Results). Collectively, the results indicate that the tir-1-p38 MAPK pathway is important for the induction of pgp-5 in response to infection and heavy metal stresses.

The tir-1 mRNA can be spliced into at least five isoforms, namely tir-1a-e [23] (Supplemental Fig. 6A). The dsRNA construct used in the previous experiments targets all the isoforms (Supplemental Fig. 6A). To determine if different TIR-1 isoforms play distinct roles in discriminating between infection and heavy metal responses upstream of pgp-5, we generated the tir-1b and tir-1a,c,e isoform-specific dsRNA constructs (Supplemental Fig. 6A). Neither RNAi against the tir-1a,c,e nor the tir-1b isoforms reproduced the significant reduction as obtained by pan-isoform RNAi on the cadmium- and PA14-induced expression of ppgp-5::gfp (Supplemental Fig. 6C and D).

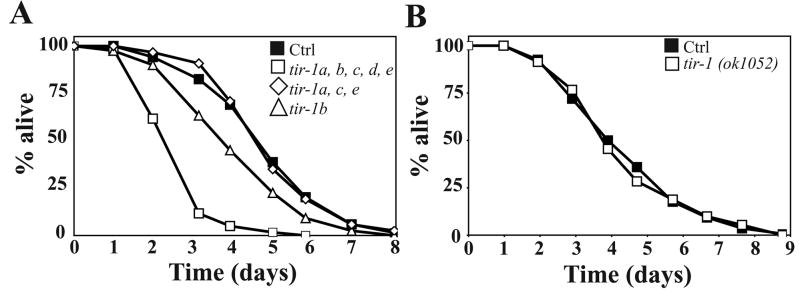

As only the pan-isoform tir-1 RNAi significantly reduced the pgp-5 induction by PA14 and heavy metals, we decided to directly test the role of the tir-1 isoforms for resistance to infection. As reported [5], knock-down of all the tir-1 isoforms markedly increased susceptibility to PA14 infection (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, RNAi against tir-1a, c, e did not affect resistance to PA14 (Log rank test, p > 0.6), whereas RNAi against tir-1b significantly reduced survival on PA14 compared to control animals (Fig. 4A). RNAi treatments did not significantly affect lifespan on E. coli: mean life spans for animals treated with vector control, tir-1 RNAi and tir-1b RNAi were 9.7 ± 0.7, 10.0 ± 0.5 and 10.2 ± 0.2 days, respectively (Log rank test, p > 0.8 when compared to vector). The RNAi results were confirmed with tir-1(ok1052) animals, which has a deletion that only removes tir-1a,c and e isoforms [23]. The tir-1(ok1052) animals had an essentially wild-type resistance to PA14 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that tir-1b, and perhaps the tir-1d isoform, may be the most important tir-1 isoforms for resistance to PA14.

Figure 4. TIR-1b, but not TIR-1ac,e is required for the C. elegans resistance to the PA14 infection.

(A) Survival of animals treated with either control (closed squares, TDmean=115 ± 8.5 hours), tir-1 (open squares, TDmean=67 ± 10 hours), tir-, TDmea1b (triangle, TDmean=88 ± 8 hours) or tir-1 a,c,e (open squares, TDmean of 109 ± 11 hours) dsRNA at the L1 stage for 48 h then exposed to PA14 at 25°C. (B) Survival curves of tir-1(ok1052) (open squares) and N2 animals (closed squares) exposed to PA14 at 25°C.

DISCUSSION

P-glycoproteins protect many organisms from environmental insults. In C. elegans, the intestinal epithelial cells are the main sites of exchange with the external milieu and potential sites for bacterial colonization. Our results suggest that PGP-5 is part of the machinery necessary to protect C. elegans intestinal cells from certain biotic and abiotic toxins, as do other P-glycoproteins in C. elegans and mammals. Although PGP-5 is required for full resistance to cadmium, its role is minor compared to that of stress response regulators like KGB-1 or MEK-1 [7]. On the other hand, like the C. elegans metallothionein genes, the induction of pgp-5 by heavy metals underscores its potential physiological role in heavy metal detoxification. PGP-5 is also contributes to resistance to bacterial infections and its expression is upregulated by infection. By analogy to PGP-1 and PGP-3, PGP-5 may be directly involved in depotentiating bacterial virulence factor(s) other than phenazines. C. elegans pgp-5 is clustered with 3 highly similar genes, pgp-6, -7 and -8 whose expression are induced during PA14 infection and/or cadmium exposure (Fig. 1). The significant, though minor, effects of loss of pgp-5 on sensitivity to pathogens and heavy metals may be due to partial compensation by these P-glycoproteins. The severely compromised resistance of tir-1(RNAi) (Fig. 4A, [4; 5]), nsy-1 and sek-1 mutants to infection [3] is likely due to the deregulation of multiple downstream effectors. The modest effect of the pgp-5 mutation relative to the loss of the TIR-1/p38 MAPK module on the nematode’s capacity to resist bacterial infection indicates that PGP-5 is only one element of the worm’s p38-dependent defense machinery.

Knocking down nsy-1, sek-1 or pmk-1 function significantly reduced pgp-5 induction by PA14 infection and cadmium. These results support a model in which defense pathways converge on the corresponding MAP3K and MAP2K and diverge downstream of their target p38 MAPK, PMK-1. TIR-1 could be one source of specificity in p38 signaling upstream of NSY-1 and SEK-1. At least 5 major isoforms of tir-1 exist (Supplemental Fig. 6A). The tir-1 locus is complex and the precise expression pattern of each tir-1 isoform remains unknown. The tir-1a,c,e isoforms are involved in the activation of NSY-1 and SEK-1 in specific neurons during development [23]. Our results indicate that these isoforms are not important for resistance to pathogens, but implicate tir-1b in this function. The possibility that tir-1d is important for defense against intestinal infection must await the availability of isoform-specific mutants.

Although previous studies have identified genes upregulated by abiotic stress or bacterial infection in C. elegans [1; 16; 17; 18; 19], the ppgp-5::gfp reporter provides the first visual in vivo read-out for response against bacterial infections and abiotic stresses. The pgp-5 transgenic strain should therefore serve as an important tool for systematic dissections of molecular networks responsible for the distinct but overlapping responses to the environment at the level of the whole organism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Tan lab, the Stanford C. elegans community and Nathalie Pujol for critical comments, discussions and technical advice; Y. Duverger and S. Scaglione for worm sorting at the C. elegans functional genomics platform of Marseille-Nice genopole®. Some nematode strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (MWT) and the Canadian Institute of Health Research (DLB). CLK was supported in part by a Bernard Cohen and a Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale Postdoctoral Fellowships.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mallo GV, Kurz CL, Couillault C, Pujol N, Granjeaud S, Kohara Y, Ewbank JJ. Inducible antibacterial defense system in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1209–14. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00928-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garsin DA, Villanueva JM, Begun J, Kim DH, Sifri CD, Calderwood SB, Ruvkun G, Ausubel FM. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science. 2003;300:1921. doi: 10.1126/science.1080147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Alloing G, Emerson FE, Garsin DA, Inoue H, Tanaka-Hino M, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Tan MW, Ausubel FM. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science. 2002;297:623–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1073759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couillault C, Pujol N, Reboul J, Sabatier L, Guichou JF, Kohara Y, Ewbank JJ. TLR-independent control of innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by the TIR domain adaptor protein TIR-1, an ortholog of human SARM. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:488–94. doi: 10.1038/ni1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liberati NT, Fitzgerald KA, Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Golenbock DT, Ausubel FM. Requirement for a conserved Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain protein in the Caenorhabditis elegans immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6593–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308625101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DH, Liberati NT, Mizuno T, Inoue H, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Ausubel FM. Integration of Caenorhabditis elegans MAPK pathways mediating immunity and stress resistance by MEK-1 MAPK kinase and VHP-1 MAPK phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10990–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403546101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizuno T, Hisamoto N, Terada T, Kondo T, Adachi M, Nishida E, Kim DH, Ausubel FM, Matsumoto K. The Caenorhabditis elegans MAPK phosphatase VHP-1 mediates a novel JNK-like signaling pathway in stress response. Embo J. 2004 doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huffman DL, Abrami L, Sasik R, Corbeil J, van der Goot FG, Aroian RV. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways defend against bacterial pore-forming toxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10995–1000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schinkel AH, Borst P. Multidrug resistance mediated by P-glycoproteins. Semin Cancer Biol. 1991;2:213–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheps JA, Ralph S, Zhao Z, Baillie DL, Ling V. The ABC transporter gene family of Caenorhabditis elegans has implications for the evolutionary dynamics of multidrug resistance in eukaryotes. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R15. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Z, Sheps JA, Ling V, Fang LL, Baillie DL. Expression analysis of ABC transporters reveals differential functions of tandemly duplicated genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeder LK, Kremer S, Kramer MJ, Currie E, Kwan E, Watts JL, Lawrenson AL, Hermann GJ. Function of the Caenorhabditis elegans ABC transporter PGP-2 in the biogenesis of a lysosome-related fat storage organelle. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahajan-Miklos S, Tan MW, Rahme LG, Ausubel FM. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model. Cell. 1999;96:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80958-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broeks A, Gerrard B, Allikmets R, Dean M, Plasterk RH. Homologues of the human multidrug resistance genes MRP and MDR contribute to heavy metal resistance in the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Embo J. 1996;15:6132–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broeks A, Janssen HW, Calafat J, Plasterk RH. A P-glycoprotein protects Caenorhabditis elegans against natural toxins. Embo J. 1995;14:1858–66. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Rourke D, Baban D, Demidova M, Mott R, Hodgkin J. Genomic clusters, putative pathogen recognition molecules, and antimicrobial genes are induced by infection of C. elegans with M. nematophilum. Genome Res. 2006;16:1005–16. doi: 10.1101/gr.50823006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shapira M, Hamlin BJ, Rong J, Chen K, Ronen M, Tan MW. A conserved role for a GATA transcription factor in regulating epithelial innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14086–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603424103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Troemel ER, Chu SW, Reinke V, Lee SS, Ausubel FM, Kim DH. p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui Y, McBride SJ, Boyd WA, Alper S, Freedman JH. Toxicogenomic analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans reveals novel genes and pathways involved in the resistance to cadmium toxicity. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R122. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurz CL, Ewbank JJ. Caenorhabditis elegans: an emerging genetic model for the study of innate immunity. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:380–90. doi: 10.1038/nrg1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurz CL, Chauvet S, Andres E, Aurouze M, Vallet I, Michel GP, Uh M, Celli J, Filloux A, De Bentzmann S, Steinmetz I, Hoffmann JA, Finlay BB, Gorvel JP, Ferrandon D, Ewbank JJ. Virulence factors of the human opportunistic pathogen Serratia marcescens identified by in vivo screening. Embo J. 2003;22:1451–60. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholas HR, Hodgkin J. The ERK MAP kinase cascade mediates tail swelling and a protective response to rectal infection in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1256–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuang CF, Bargmann CI. A Toll-interleukin 1 repeat protein at the synapse specifies asymmetric odorant receptor expression via ASK1 MAPKKK signaling. Genes Dev. 2005;19:270–81. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.