Abstract

Metabolism of melatonin (MEL) in mouse was evaluated through a metabolomic analysis of urine samples from control and MEL-treated mice. Besides identifying seven known MEL metabolites (6-hydroxymelatonin glucuronide, 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate, N-acetylserotonin glucuronide, N-acetylserotonin sulfate, 6-hydroxymelatonin, 2-oxomelatonin, 3-hydroxymelatonin), principal components analysis of urinary metabolomes also uncovered seven new MEL metabolites, including MEL glucuronide, cyclic MEL, cyclic N-acetylserotonin glucuronide, cyclic 6-hydroxymelatonin; 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetaldehyde, di-hydroxymelatonin and its glucuronide conjugate. However, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxy-kynuramine and N1-acetyl-5-methoxy-kynuramine, known as MEL antioxidant products, were not detected in mouse urine. Metabolite profiling of MEL further indicated that 6-hydroxymelatonin glucuronide was the most abundant MEL metabolite in mouse urine, which comprised 75, 65, and 88% of the total MEL metabolites in CBA, C57/BL6, and 129Sv mice, respectively. Chemical identity of 6-hydroxymelatonin glucuronide was confirmed by deconjugation reactions using β-glucuronidase and sulfatase. Compared with wild-type and CYP1A2-humanized mice, Cyp1a2-null mice yielded much less 6-hydroxymelatonin glucuronide (∼10%) but more N-acetylserotonin glucuronide (∼195%) and MEL glucuronide (∼220%) in urine. In summary, MEL metabolism in mouse was recharacterized by using a metabolomic approach, and the MEL metabolic map was extended to include seven known and seven novel pathways. This study also confirmed that 6-hydroxymelatonin glucuronide was the major MEL metabolite in the mouse, and suggested that there was no interspecies difference between humans and mice with regard to CYP1A2-mediated metabolism of MEL, but a significant difference in phase II conjugation, yielding 6-hydroxymelatonin glucuronide in the mouse and 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate in humans.

IT HAS LONG BEEN established that melatonin (MEL) is primarily converted by metabolic oxidation to 6-hydroxymelatonin (6-HMEL) and N-acetylserotonin (NAS) in a range of species, including humans (1,2,3). However, there have been reports of variable contributions of glucuronidation and sulfation to the conjugation of these primary metabolites, particularly 6-HMEL (1,4,5,6,7,8,9). Knowledge of the principal excretory products of MEL is important because urine represents a readily accessible source of surrogate biomarkers for pineal activity, rather than the determination of very low circulating concentrations of MEL itself. Indeed, pineal activity in both humans and experimental animals is generally evaluated through the urinary excretion of the sulfate conjugate of 6-HMEL (SaMT) using one of several available antibody-based methods (10). The validity of SaMT determinations in this context depends on the relative contribution of this excretory pathway to the overall disposition of MEL. It is necessary to know what proportion of MEL is converted to 6-HMEL and, in addition, what proportion of 6-HMEL is conjugated with sulfate. There would appear to be both interspecies variation in these pathways and a lack of consensus regarding the relative proportions of the excreted metabolites. Of particular note has been recent work in the mouse, in which it was reported that 6-HMEL is excreted almost exclusively as the glucuronide, in contrast to the rat, which excreted the sulfate conjugate (9). In contrast, other workers have claimed that the mouse excretes SaMT, although levels of the glucuronide were not determined (8). Major 6-HMEL glucuronidation would limit the utility of immunoassays for urinary SaMT as a surrogate measure of MEL rhythmicity in mouse investigations.

Metabolomics is the systematic study of small molecule metabolite profiles that are left behind as unique chemical fingerprints by specific cellular processes. By combining the speed and resolving power of ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC) with the accurate mass determination of time-of-flight mass spectrometry (TOFMS) and with multivariate data analysis, it is now possible to determine small changes in the urinary metabolome that occur between different groups of animals or, indeed, human subjects. The utility of this new technology in relation to the metabolism in mice of the experimental cancer drug aminoflavone (11), the areca alkaloids arecoline and arecaidine (12), and the major metabolite of arecoline, arecoline 1-oxide (13), were recently reported. In all of these cases, large numbers of novel urinary metabolites were uncovered and methods were also described for their approximate quantitation using metabolomics (13). Here MEL metabolism in the mouse was studied using metabolomics. In addition, experiments were carried out to determine unequivocally whether 6-HMEL is conjugated with sulfate (8) or glucuronic acid (9) and to investigate the potential species differences of CYP1A2 in MEL metabolism by using wild-type, Cyp1a2-null, and CYP1A2-humanized mice.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and reagents

MEL, 6-HMEL, NAS, 6-chloromelatonin, chlorosulfonic acid, p-nitrocatechol sulfate solution, phenolphthalein β-d-glucuronide, β-glucuronidase (type B-1 from bovine liver), and arylsulfatase (type H-1 from Helix pomatia and type VIII from abalone entrails) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK), N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK), and cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin (c3-HMEL) were a gift from Dr. Dun-Xian Tan (San Antonio, TX). 2-Oxomelatonin (2-OMEL) was a gift from Professor Leopoldo Ceraulo (Palermo, Italy). All solvents for UPLC-TOFMS and liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and other chemicals were of the highest grade commercially available.

Synthesis of SaMT

The synthesis of SaMT was carried out as described previously (14) with minor modification. Briefly, 40 mg of 6-HMEL was dissolved in 200 μl dimethylformamide and cooled on ice. Chlorosulfonic acid (40 μl) was added cautiously at 4 C and the solution left on ice for 30 min. Hexane was added dropwise to the reaction mixture until turbid. The solution was then loaded onto a 23 × 1.5 cm Florisil column, eluted with 20% methanol in chloroform (150 ml), and 4-ml fractions collected. Each fraction was subjected to analysis by thin-layer chromatography on Silica gel F254 plates, eluted with 1-butanol-acetic acid-water (4:1:1). This analysis showed that the first fractions contained a substance that coeluted with authentic 6-HMEL (RF = 0.78) and the later fractions contained no 6-HMEL, rather a single more polar material (RF = 0.49). Fractions 22–27, containing only the polar material, were combined, evaporated to dryness under N2, and redissolved in 2 ml methanol. This solution was analyzed by UPLC-TOFMS and gave a single peak with a m/z 329.081 in positive-ion mode, and a m/z 327.063 in negative-ion mode, both corresponding to the correct empirical formula (C13H16N2O6S) for SaMT, with mass errors of 1.2 and 6.1 ppm, respectively. Further analysis was performed by incubating the product with sulfatase in 200 mm sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 37 C for 6 h, after which ions corresponding to SaMT completely disappeared and the signal for 6-HMEL rose 100-fold, confirming the identity of SaMT with less than 1% contamination by 6-HMEL.

Animals and treatments

Three strains of wild-type mice (WT) were used in the current study with the background of C57/BL6, CBA, and 129Sv. To investigate a potential species difference of CYP1A2 activity in MEL metabolism, Cyp1a2-null mice and CYP1A2-humanized mice (hCYP1A2) were also used. The characteristics of Cyp1a2-null mice and hCYP1A2 mice have been previously described (15,16). All mice were maintained under a standard 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle with water and chow provided ad libitum. Handling was in accordance with animal study protocols approved by the National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee. MEL (4 mg/kg) was administered by ip, and mice were immediately housed in separate metabolic chambers (Jencons, Leighton Buzzard, UK). Urines were collected over a 24-h period after MEL administration. Control urine samples were collected 2 d before MEL treatments. Urine samples were centrifuged (3000 g, 5 min, 4 C) to discard farragoes and stored at −80 C for further analysis.

UPLC-TOFMS analysis

Urines were analyzed by UPLC-TOFMS (11), and urinary metabolomes of the control and MEL-treated mice were characterized in a principal components analysis (PCA) model. Samples for UPLC-TOFMS analysis were prepared by mixing 20 μl of urine with 200 μl of 50% acetonitrile and centrifuging at 18,000 × g for 5 min to remove protein and particulates. A 200-μl aliquot of the supernatant was transferred to an autosampler vial, and a 5-μl aliquot was injected into a UPLC-TOFMS system (Waters, Milford, MA). An Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (Waters) was used to separate MEL and its metabolites. The flow rate of mobile phase was 0.6 ml/min with a gradient ranging from water to 95% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid in a 10 min run. The QTOF Premier mass spectrometer was operated in both positive and negative electrospray ionization mode. Source temperature and desolvation temperature were set at 120 and 350 C, respectively. Nitrogen was applied as the cone (50 liters/h) and desolvation gas (600 liters/h) and argon as collision gas. For accurate mass measurement, the QTOFMS was calibrated with sodium formate solution (range m/z 100-1000) and monitored by the intermittent injection of the lock mass sulfadimethoxine [(M+H)+ = 311.0814 m/z] in real time. Mass chromatograms and mass spectral data were acquired by MassLynx software in centroid format and were further processed by MetaboLynx software to screen and identify potential MEL metabolites. The structure of each MEL metabolite was elucidated by tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) fragmentation with collision energy ranging from 10 to 40 eV. MEL metabolites were ascertained on the basis of the accurate masses obtained, their MS/MS fragmentation patterns, and comparison with authentic standards. In the case of sulfate and glucuronic acid conjugates, structural assignment was made on the basis of both accurate mass and deconjugation experiments.

Deconjugation of urinary MEL metabolites

β-Glucuronidase (type B-1, G0251), sulfatase (type H-1, S9626), and sulfatase (type VIII, S9754) were used for the deconjugation studies. d-Saccharic acid 1,4-lactone (SAL) was used as a specific β-glucuronidase inhibitor (8). p-Nitrocatechol sulfate and phenolphthalein β-d-glucuronide were used as positive control substrates for sulfatase and β-glucuronidase, respectively (17,18). Sulfatase and β-glucuronidase were dissolved in 0.2% (wt/vol) sodium chloride solution immediately before use. The deconjugation system included 50 μl MEL-treated mouse urine, 40 U/ml sulfatase, or β-glucuronidase, with or without 1 mm SAL, 200 mm sodium acetate buffer, and the total volume was 1 ml. The deconjugation mixtures were incubated for 6 h at 37 C. The incubation was terminated by the addition of 2 ml ethyl acetate/tert-butyl methyl ether (1:1). 6-Chloromelatonin (5 μl of 100 μm) was added as internal standard. The samples were vortexing for 20 sec and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min at 4 C. The organic layers were transferred to clean tubes and blown to dryness under N2. The extracted urine samples were reconstituted in 100 μl 70% aqueous methanol containing 0.1% formic acid, and 6 μl were injected to LC-MS/MS for MEL, 6-HMEL, and NAS analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis

LC-MS/MS analysis was described previously (19). Briefly, LC-MS/MS was performed using an API 2000 ESI triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). A Luna 3 μm 50 × 4.6 mm C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) was used to separate the MEL, 6-HMEL, and NAS. The flow rate through the column at ambient temperature was 0.25 ml/min with 70% aqueous methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. The mass spectrometer was equipped with a turbo ion spray source and run in the positive ion mode. The turbo ion spray temperature was maintained at 350 C and a voltage of 5.0 kV was applied to the sprayer needle. N2 was used as both turbo ion spray and nebulizer gas. The detection and quantification of MEL, 6-HMEL, and NAS were accomplished by multiple reactions monitoring with the transitions m/z 232.9/174.0 for MEL, 249.1/190.0 for 6-HMEL, and 219.0/160.1 for NAS. MS/MS conditions were optimized automatically for each analyte and the raw data were processed using Analyst software (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical and multivariate data analysis

Centroided and integrated mass spectrometric data from the UPLC-TOFMS were processed to generate a multivariate data matrix using MarkerLynx (Waters). Centroided data were Pareto scaled and further analyzed by principal components analysis (PCA) and orthogonal projection to latent surfaces (OPLS) using SIMCA-P+ software (Umetrics, Kinnelon, NJ). All values are expressed as the means ± sd and group differences analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test.

Results

Justification of MEL dose

This study was designed to determine the metabolic pathways of exogenously administered MEL, and thus, a pharmacological dose of 4 mg/kg was used. This dose is comparable with the dose clinically used in humans, when the mouse-human species difference is taken into consideration In humans, exogenous MEL is generally used for anesthesia premedication at a dose of up to 0.2 mg/kg (20,21). In cancer chemotherapy, MEL was used at doses from 0.2 to 0.6 mg/kg (22). Used as an antioxidant in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients, 5 mg/kg was administered up to 4 months (23). The dose in current study on exogenous MEL was 4 mg/kg in mice, which is about 0.4 mg/kg when extrapolated to the human dose according to the species difference between mice and humans. In the earliest study on the disposition of MEL, approximately 1–2 mg/kg MEL was used in rats (4). In a recent study in mice and rats, the doses were approximately 160 mg/kg (9). The dose of 4 mg/kg is reasonably conservative.

Identification of the urinary metabolites of MEL using metabolomics

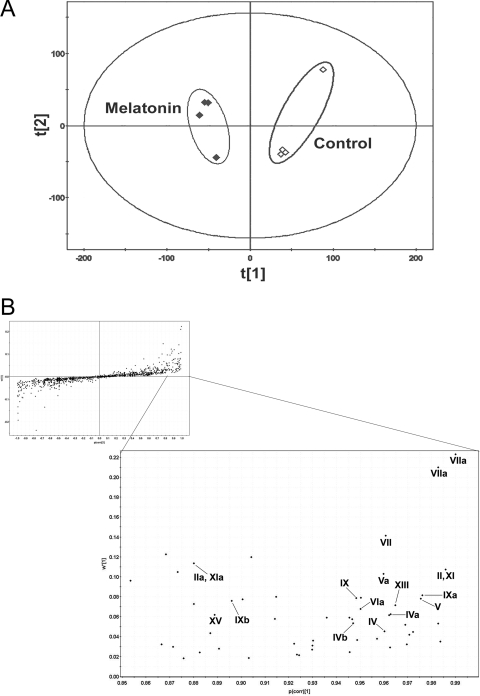

Results of the chemometric analysis on the ions produced by UPLC-MS assay of control and MEL-treated mouse urines are shown in Fig. 1. The unsupervised PCA scores plot (Fig. 1A) reveals two clusters corresponding to the control and MEL-treated groups. The corresponding S-plot (Fig. 1B), derived from OPLS shows the ions that contribute to this group separation. The ions associated with MEL treatment that contribute to group separation are listed in Table 1, and many of the highest ranking ions were MEL metabolites.

Figure 1.

Metabolomic analysis of control and MEL-treated mouse urines. WT mice (n = 4) were treated with 4 mg/kg MEL (ip), and 24-h urines were collected for analysis. A, Separation of control and MEL-treated mouse urine samples in a PCA scores plot. The t(1) and t(2) values represent the scores of each sample in principal component 1 and 2, respectively. B, Loadings S-plot generated by OPLS analysis. The y-axis is a measure of the relative abundance of the ions, and the x-axis is a measure of the correlation of each ion to the model. This loading plot represents the relationship between variables (ions) and observation groups (control and MEL treated) with regard to the first and second components present in A. MEL metabolites are labeled.

Table 1.

The ions associated with MEL treatment that contribute to group separation

| Observed m/z (M+H)+ | Retention time (min) | Significance score | Identity | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 249.124 | 2.81 | 16.4 | 6-HMEL glucuronide (in-source fragment) | VIIa |

| 447.137 | 2.81 | 15.4 | 6-HMEL glucuronide (sodium adduct) | VIIb |

| 425.154 | 2.81 | 10.1 | 6-HMEL glucuronide | VII |

| 249.124 | 3.30 | 7.9 | 6-HMEL and c3-HMEL | II, XI |

| 271.107 | 3.30 | 7.5 | 6-HMEL and c3-HMEL (sodium adduct) | IIa, XIa |

| 271.106 | 3.51 | 7.4 | 2-OMEL (sodium adduct) | Va |

| 287.101 | 2.66 | 6.8 | di-HMEL (sodium adduct) | VIa |

| 219.114 | 2.41 | 5.9 | NAS glucuronide (in-source fragment) | IXa |

| 249.124 | 3.52 | 5.7 | 2-OMEL | V |

| 395.144 | 2.41 | 5.5 | NAS glucuronide | IX |

| 393.130 | 2.81 | 5.2 | cNAS glucuronide | XIII |

| 417.130 | 2.40 | 5.1 | NAS glucuronide (sodium adduct) | IXb |

| 431.144 | 3.40 | 4.5 | MEL glucuronide (sodium adduct) | IVa |

| 194.080 | 3.46 | 4.1 | 5-HIAL | XV |

| 409.160 | 3.40 | 3.7 | MEL glucuronide | IV |

| 233.131 | 3.40 | 3.7 | MEL glucuronide (in-source fragment) | IVb |

Urine samples (n = 4) were collected 24 h after MEL (ip) treatment and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Screening and identification of major metabolites were performed by using MetaboLynx software based on accurate mass measurement.

6-HMEL glucuronide

The top three ranking ions were all derived from 6-HMEL glucuronide (VII) and had masses of [M+H]+ = 425.154 m/z (VII; C19H25N2O9), [M+Na]+ = 447.137 m/z (VIIb; sodium adduct), and their in-source fragment [M+H]+ = 249.124 m/z (VIIa; loss of glucuronic acid, −176 Da). The MS/MS structural elucidation of 6-HMEL glucuronide was shown in Fig. 2A, and the major daughter ions 249, 190, and 158 from fragmentation were interpreted in the inlaid structural diagram.

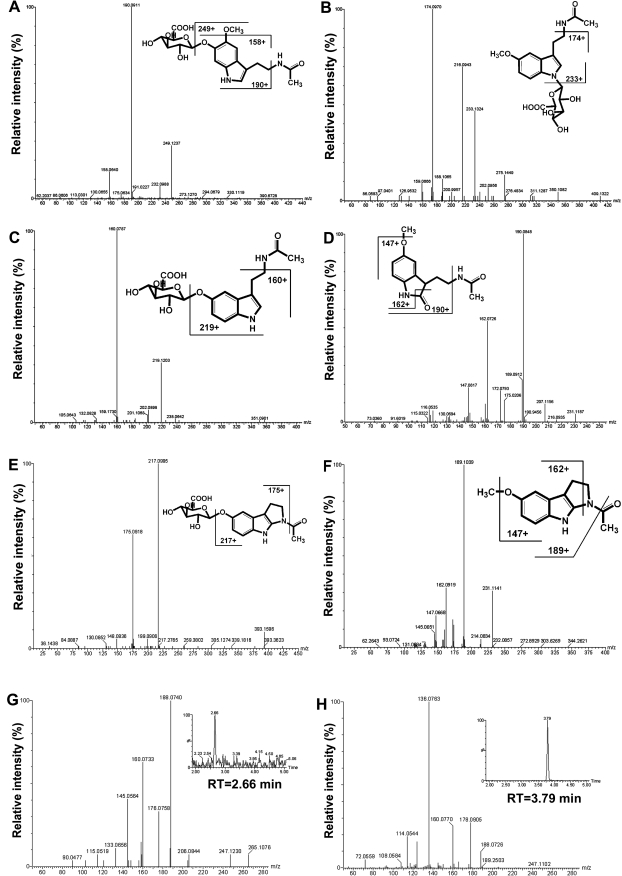

Figure 2.

LC-MS/MS structural elucidation of MEL metabolites in mouse urine. Urine samples from WT mice were collected for 24 h after ip administration of 4 mg/kg MEL. MS/MS fragmentation was conducted with collision energy ramping from 10 to 40 eV. Major daughter ions from fragmentation were interpreted in the inlaid structural diagrams. A, MS/MS fragmentation of 6-HMEL glucuronide. B, MS/MS fragmentation of MEL glucuronide. C, MS/MS fragmentation of NAS glucuronide. D, MS/MS fragmentation of 2-OMEL. E, MS/MS fragmentation of cNAS glucuronide. F, MS/MS fragmentation of cMEL. G, MS/MS fragmentation of di-HMEL (m/z 265+), retention time at 2.66 min. H, MS/MS fragmentation of AFMK (m/z 265+), retention time at 3.79.

MEL monohydroxylation

Three MEL monohydroxylated metabolites, 6-HMEL (II), c3-HMEL (XI), and 2-OMEL (V), were observed in the high ranking ions list after 6-HMEL glucuronide (Table 1). Unconjugated 6-HMEL could not be resolved from c3-HMEL in the UPLC-MS system (Fig. 3A). Both 6-HMEL and c3-HMEL had masses of [M+H]+ = 249.124 m/z (C13H17N2O3), [M+Na]+ = 271.107 m/z (IIa and XIa; sodium adduct). A previous study had reported 2-OMEL as a MEL metabolite in vivo (7). In the current study using the metabolomics approach, 2-OMEL (V), retention time at 3.52 min, was also detected in positive ion mode (Fig. 3A). 2-OMEL had masses of [M+H]+ = 249.124 m/z (C13H17N2O3), [M+Na]+ = 271.106 m/z (Va; sodium adduct). The MS/MS structural elucidation of 2-OMEL was shown in Fig. 2D, and the major daughter ions 190, 162, and 147 from fragmentation were interpreted in the inlaid structural diagram (Fig. 2D).

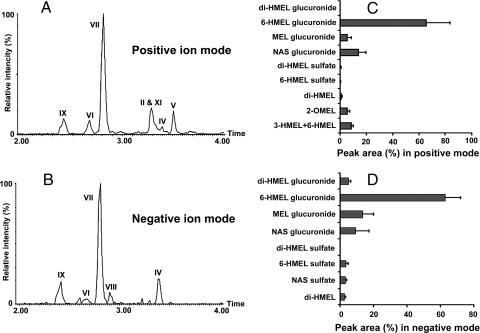

Figure 3.

Representative chromatograms of major MEL metabolites and their relative quantification. WT mice (C57/BL6 strain) were treated with 4 mg/kg MEL (ip). Urine samples were collected 24 h after MEL treatment, and analyzed by UPLC-MS. Screening and identification of major metabolites were performed by using MetaboLynx software based on accurate mass measurement. The identities of metabolites were presented in Table 1 and Fig. 7. A, Chromatograms of major MEL metabolites in positive ion mode. B, Chromatograms of major MEL metabolites in negative ion mode. C, Relative quantification of MEL metabolites in positive ion mode. D, Relative quantification of MEL metabolites in negative ion mode. The abundance of each metabolite was represented as a relative peak area (area percent ± sd, n = 4) by calculating its percentage in the total peak area of MEL and its urinary metabolites.

MEL dihydroxylation

A mass of [M+Na]+ = 287.101 m/z (VIa) was noted in the high ranking ions list after the MEL monohydroxylated metabolites (Table 1). This ion gave a clear peak by UPLC-MS with a m/z of 265.108 in positive-ion mode (Figs. 2G and 3A), which corresponded to the correct empirical formula (C13H17N2O4) for a dihydroxymelatonin (di-HMEL; VI), with mass error less than 10 ppm. di-HMEL had a significantly shorter retention time (2.66 min) than all of the MEL monohydroxylated metabolites (Fig. 3A). AFMK (XVI), a well known MEL metabolite, has the same molecular weight as di-HMEL, but it was not detected in mouse urine. Based on the differences of retention time and MS/MS fragmentation (Fig. 2, G and H), the proposed di-HMEL is not the same ion as AFMK. Moreover, AMK (XVII), a subsequent metabolite of AFMK, was also not detected in mouse urine.

NAS and cyclic NAS (cNAS) glucuronide

NAS glucuronide had masses of [M+H]+ = 395.144 m/z (IX; C18H23N2O8), [M+Na]+ = 417.130 m/z (IXb; sodium adduct), and their in-source fragment [M+H]+ = 219.114 m/z (IXa; loss of glucuronic acid, −176 Da). The MS/MS structural elucidation of NAS glucuronide is shown in Fig. 2C, and the major daughter ions 219 and 160 from fragmentation were interpreted in the inlaid structural diagram. A novel MEL metabolite, cNAS glucuronide (XIII), was identified with mass of [M+H]+ = 393.130 m/z, which corresponded to the correct empirical formula (C18H21N2O8) with mass error 1.5 ppm. The MS/MS fragmentation of cNAS glucuronide is interpreted in Fig. 2E, with major daughter ions 217 and 175.

MEL glucuronide

MEL glucuronide (IV) was identified as another novel metabolite with a formula of C19H24N2O8, present as a protonated molecular ion (m/z = 409.160, IV), a sodium adduct (m/z = 431.144, IVa), and an in-source fragment ion (m/z = 233.131, IVb; MH+-176 Da). The loss of 176 Da is characteristic of glucuronides. Treatment with β-glucuronidase abolished this peak and a peak appeared at 4.42 min, corresponding to MEL with [M+H]+ = 233.129 m/z and [M+Na]+ = 255.111 m/z. The only possible site for a direct glucuronide of MEL is on the indole nitrogen. The MS/MS fragmentation was consistent for MEL glucuronide with the major daughter ions 233 and 174 (Fig. 2B).

Other novel MEL metabolites

In addition to di-HMEL, cNAS glucuronide, and MEL glucuronide, four more novel MEL metabolites were identified as cyclic MEL (cMEL, XIV, C13H14N2O2), cyclic 6-HMEL (c6-HMEL, XII, C13H14N2O3), 5-hydroxyindoleacetaldehyde (5-HIAL, XV, C10H9NO2), and di-HMEL glucuronide (C19H24N2O10). All mass errors for these new metabolites were less than 10 ppm.

Quantification of the urinary MEL metabolites

Chromatograms in positive and negative mode for all ions identified as MEL metabolites are shown in Fig. 3, A and B. 6-HMEL glucuronide (VII) showed the biggest peak in both positive ion mode (Fig. 3A) and negative ion mode (Fig. 3B), with a retention time of 2.81 min. SaMT (VIII), which is the predominant urinary metabolite in rat and human (4,5), was not detected in mouse urine in positive ion mode (Fig. 3A). However, it appeared as a small peak in the negative ion chromatogram (Fig. 3B). This peak had an identical retention time (2.90 min) to authentic SaMT and an identical fragmentation pattern by LC-MS/MS. All MEL metabolites were quantitated according to their total peak area (MH+ plus Na+ adduct plus in-source fragment ion) and the results are depicted in Fig. 3, C and D. In C57/BL6 mouse urine, 6-HMEL glucuronide (VII) corresponded to 65.2% of total peak area in positive ion mode and next for NAS glucuronide (IX) at 13.6%. After 6-HMEL glucuronide and NAS glucuronide, the contributions of 2-OMEL (V), MEL glucuronide (IV), and di-HMEL (VI) were 5.6, 5.4, and 0.8%, respectively (Fig. 3C). Using the negative ion mode peak areas (Fig. 3D), the highest compound was still 6-HMEL glucuronide (VII) at 62.8% of total peak area. No significant strain difference was observed for 6-HMEL glucuronidation in mice, with 75, 65, and 88% in total MEL metabolites in CBA, C57/BL6, and 129Sv mouse strains, respectively. Compared with 6-HMEL glucuronide (VII), SaMT (VIII) was minor, whose contribution to the total peak area is about 0.1% in positive mode and 3.6% in negative mode.

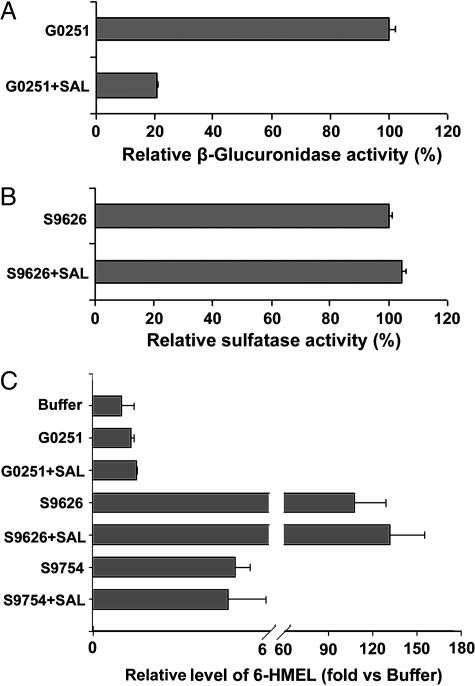

Deconjugation of MEL urinary metabolites

There has been a debate regarding the MEL final excretory products in mouse urine, whether these are 6-HMEL sulfate or glucuronide (8,9). In the current study, both β-glucuronidase and sulfatase were used for deconjugation analysis. SAL was used as a specific β-glucuronidase inhibitor. Incubation with p-nitrocatechol sulfate solution or phenolphthalein β-d-glucuronide, together with or without SAL, was performed to identify the activity of sulfatase and β-glucuronidase (Fig. 4, A and B). Deconjugation for standard SaMT revealed sulfatase activity for both S9626 and S9754, and SAL had no significant effect on SaMT deconjugation (Fig. 4C). Because of the high activity of S9626 sulfatase in SaMT deconjugation, it was used for deconjugation of urinary MEL metabolites. S9626 sulfatase contains some β-glucuronidase activity (http://www.sigmaaldrich.com). However, SAL can significantly inhibit β-glucuronidase in S9626. After a 6-h incubation, the 6-HMEL level increased 18 and nine times, respectively, for S9626 and G0251, and both were inhibited by SAL (Fig. 5, A and D), which indicated that the major conjugated metabolite for 6-HMEL in mouse urine was 6-HMEL glucuronide. These deconjugation data were consistent with the data produced in the UPLC-MS assay (Table 1 and Fig. 3). For NAS glucuronide, deconjugation by β-glucuronidase resulted in a greater than 10 times increase in NAS concentration (Fig. 5, B and E). Deconjugation by β-glucuronidase also increased the MEL concentration greater than 50%, compared with the buffer alone (Fig. 5, C and E), which confirmed the existence of a MEL glucuronide in mouse urine (Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 4.

β-Glucuronidase (G0251) and sulfatase (S9626 and S9754) activity analysis. A, Deconjugation of phenolphthalein β-d-glucuronide by β-glucuronidase. The deconjugation system included 1 mm phenolphthalein β-d-glucuronide, 40 U/ml β-glucuronidase, with or without 1 mm SAL, 200 mm sodium acetate buffer, and the total volume was 1 ml. The incubation proceeded at 37 C for 30 min with shaking and terminated by adding 1 ml 1 m NaOH and tested by spectrophotometry at 540 nm. B, Deconjugation of p-nitrocatechol sulfate by sulfatase. The deconjugation system included 1 mm p-nitrocatechol sulfate, 40 U/ml sulfatase, with or without 1 mm SAL, 200 mm sodium acetate buffer, and the total volume was 1 ml. The incubation proceeded at 37 C for 30 min with shaking and terminated by adding 1 ml 1 m NaOH and tested by spectrophotometry at 515 nm. C, Deconjugation of SaMT by sulfatase. The deconjugation system included standard SaMT, 40 U/ml sulfatase or β-glucuronidase, with or without 1 mm SAL, 200 mm sodium acetate buffer, and the total volume was 1 ml. The incubation proceeded at 37 C for 6 h with shaking and terminated by adding 2 ml ethyl acetate/tert-butyl methyl ether. The deconjugation mixture was extracted and 6-HMEL monitored by LC-MS/MS.

Figure 5.

Deconjugation of urinary MEL metabolites. The deconjugation system included 50 μl MEL-treated mouse urine, 40 U/ml sulfatase or β-glucuronidase, with or without 1 mm SAL, 200 mm sodium acetate buffer, and the total volume was 1 ml. The deconjugation mixtures were incubated for 6 h at 37 C. The incubation was terminated by the addition of 2 ml ethyl acetate/tert-butyl methyl ether (1:1). The deconjugation mixture was extracted, and 6-HMEL, NAS, and MEL were monitored by LC-MS/MS. A, Relative level of 6-HMEL in deconjugation system with S9626. B, Relative level of NAS in deconjugation system with S9626. C, Relative level of MEL in deconjugation system with S9626. D, Relative level of 6-HMEL in deconjugation system with G0251. E, Relative level of NAS in deconjugation system with G0251. F, Relative level of MEL in deconjugation system with G0251.

Role of human CYP1A2 in MEL metabolism

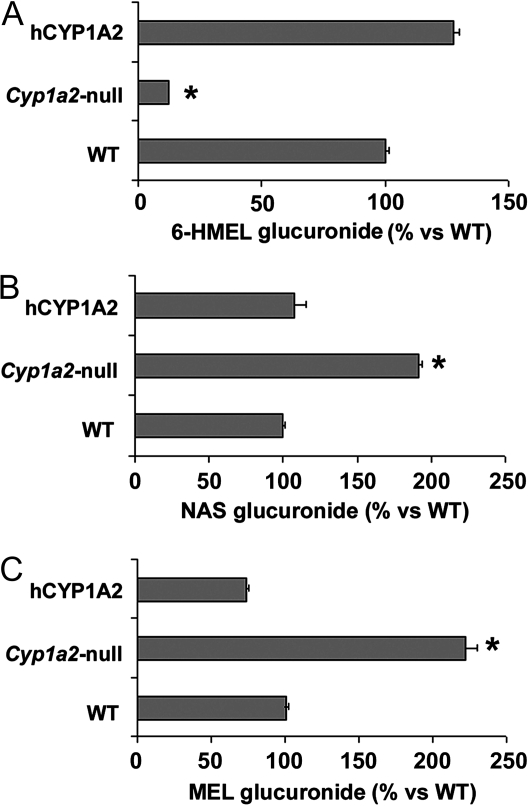

To investigate a potential species difference in MEL metabolism due to CYP1A2, Cyp1a2-null mice and hCYP1A2 were used together with wild-type mice. Compared with WT and hCYP1A2, Cyp1a2-null mice yielded much less 6-HMEL glucuronide (Fig. 6A) but more NAS glucuronide and MEL glucuronide in urine (Fig. 6, B and C). For each major MEL metabolite, hCYP1A2 mice showed a similar metabolic profile to WT, suggesting that there was no interspecies difference between humans and mice in CYP1A2-mediated MEL 6-hydroxylation.

Figure 6.

Major urinary MEL metabolites in WT, Cyp1a2-null, and hCYP1A2 mice. MEL (4 mg/kg) was administered ip, and mice were immediately housed in separate metabolic chambers. Urines were collected over a 24-h period after MEL administration and analyzed by UPLC-MS. A, Relative level of 6-HMEL glucuronide in mouse urine. B, Relative level of NAS glucuronide in mouse urine. C, Relative level of MEL glucuronide in mouse urine. Each metabolite in the WT group was regarded as 100%. *, P < 0.05, compared with WT and hCYP1A2 mice (n = 4).

Discussion

Two lines of evidence revealed that the dominant MEL metabolite in mouse urine is 6-HMEL glucuronide. First, ions corresponding to 6-HMEL glucuronide ranked first in the contribution to the separation of control and MEL-treated mouse urines in the PCA analysis, in which they corresponded to over 60% of total MEL metabolites. Second, β-glucuronidase treatment dramatically increased 6-HMEL urinary concentrations, and this was inhibited by the specific β-glucuronidase inhibitor SAL. Conversely for SaMT, its contribution to total peak area was approximately 0.1% in positive ion mode and 3.6% in negative ion mode, which suggested that SaMT was only a minor metabolite in mouse urine, especially when compared with 6-HMEL glucuronide. These data are consistent with a previous report that 6-HMEL was excreted almost exclusively as the glucuronide in the mouse (9) but at variance with a more recent report that SaMT is a key urinary metabolite in the mouse (8). The confirmation of 6-HMEL glucuronide as the major MEL metabolite has several implications, especially for the use of urinary biomarkers of pineal activity and MEL rhythmicity in mice. In a recent study, urinary SaMT was detected at 7.5 ng/ml in C3H/He mice and 42.6 ng/ml in C57BL/6 mice (8). However, C57BL/6 mice are genetically MEL deficient (24), and C3H mice are MEL proficient, especially compared with C57BL mice (25). So the result for urinary SaMT in C57BL/6 mice is questionable (8), which also suggested that SaMT is not an accurate indicator for MEL in mice.

Moreover, it is interesting to note the significant species difference in 6-HMEL conjugation between both mouse and human and also mouse and rat, whereby 6-HMEL glucuronidation occurs in mice and sulfation in human and rat (1,9). However, by comparing urinary MEL metabolite profiles among wild-type, Cyp1a2-null, and hCYP1A2 mice, it was revealed that there was no species difference in MEL CYP1A2-mediated 6-hydroxylation between humans and mice. Species differences in xenobiotic metabolism are very common, and often the mechanisms are unknown. For example, the procarcinogen 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine is predominantly metabolized to N2-hydroxylation and further conjugated with glucuronide in humans; however, in mice, the main pathway is 4-hydroxylation and sulfation (26). Indeed, this is opposite to what was found with MEL and probably reflects the differences in substrate specificities between the human and mouse conjugating enzymes. Species differences in drug metabolism are important issues in the preclinical development of new drugs, including hormone derivatives, and this is the major reason for generation of numerous in vitro and in vivo models to investigate species differences in drug metabolism (27,28,29).

PCA analysis of the mouse urinary metabolome also uncovered seven new MEL metabolites, specifically, MEL glucuronide, cMEL, cNAS glucuronide, c6-HMEL; 5-HIAL, di-HMEL and its glucuronide conjugate. Among these new metabolites, MEL glucuronide was the most abundant, which contributed approximately 5% to the total MEL metabolite profile. Three cyclic metabolites, cMEL, c6-HMEL, and cNAS glucuronide, were observed in mouse urine, but their contribution was less than 1% of total MEL metabolites. 5-HIAL excretion in urine was also small, but it provided the solid evidence for the proposed serotonin-melatonin cycle in vivo, as MEL catalyzed by arylacylamidase to 5-methoxytryptamine, and further metabolized by monoamine oxidase to 5-HIAL (30). Together with three established MEL monohydroxylated metabolites, di-HMEL and its glucuronide conjugate were observed in mouse urine. di-HMEL has the same molecular weight as AFMK; however, it was not AFMK based on differences in MS/MS fragmentation and UPLC retention time. The structure of di-HMEL was not further pursued, but it is likely to occur subsequent to the major metabolic pathway of 6-hydroxylation and therefore could be 4,6-di-HMEL, 6,7-di-HMEL, or even 2,6-di-HMEL.

AFMK and AMK are well known as MEL metabolites arising from the reaction of MEL with reactive oxygen species (31,32,33,34,35). Surprisingly, AFMK and AMK were not detected in mouse urine after ip treatment with 4 mg/kg MEL. Previously it was reported that they comprised approximately 0.04% of total MEL metabolites in mouse urine after an oral dose of 20 mg/kg MEL (7). AFMK and AMK were the first identified MEL metabolites, as early as 1974, and this pathway was reported to represent 35% of the dose after intracisternal injection and 15% after iv injection (36). However, this is the second time that AFMK and AMK were found as very minor MEL metabolites or, in this case, undetectable, which raises the question regarding the role of AFMK and AMK as antioxidant products in vivo because MEL is commonly taken as an antioxidant (37,38). Interestingly, both 2-OMEL and c3-HMEL were detected in our current and previous studies. Of note is the excretion of 2-OMEL, which comprised more than 5% of total MEL metabolites, which is more than 100 times more than the AMK/AFMK pathway (7). c3-HMEL excretion in mouse urine was reported to be significantly higher than that of AFMK and AMK after oral administration MEL (7). 2-OMEL was recently identified as a product of the reaction between MEL and the Fenton reagent, as well as with both HOCl and oxoferryl hemoglobin, and it has been reported as a MEL product in vivo (7,39). c3-HMEL is the product of the reaction of melatonin with HO•, generated in the Fenton reaction and in an UV photolysis system, and it has been reported in the urine of both rats and humans (40). The excretion of both 2- and 3-oxidized MEL derivatives in mouse urine demonstrates that these are formed in vivo. Further studies are suggested to investigate whether 2-OMEL and c3-HMEL are potential antioxidant products of MEL in vivo.

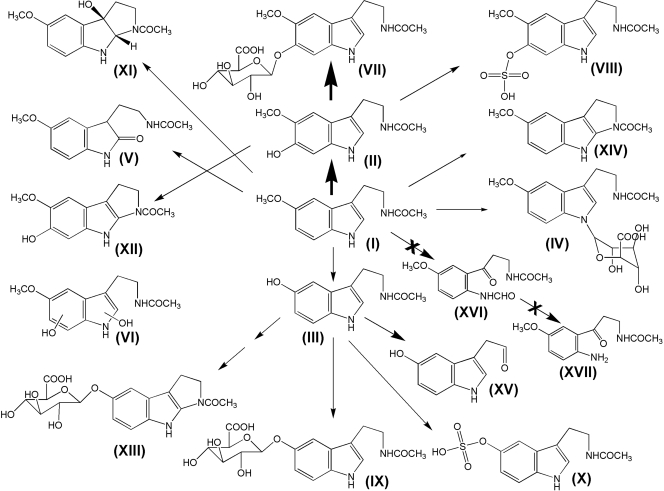

In summary, MEL metabolism in mouse was recharacterized by using a metabolomic approach, and MEL metabolism maps were extended to include seven known and seven novel pathways (Fig. 7). This study also confirmed that 6-HMEL glucuronidation was the major MEL metabolic pathway in mouse and suggested that there was no interspecies difference between humans and mice with regard to CYP1A2-mediated metabolism of MEL but a significant difference in conjugation reactions, with 6-HMEL glucuronide excreted in mice and 6-HMEL sulfate in humans. These findings have implications for the utility of the mouse as a model for MEL biochemistry, physiology, and endocrinology.

Figure 7.

MEL metabolic pathways in mouse. CYP1A2 transforms MEL (I) to 6-HMEL (II), which can be further metabolized dominantly to glucuronide metabolite (VII) and minor sulfate metabolite (VIII). Besides C6 hydroxylation, MEL undergoes O-demethylation to NAS (III), which is further conjugated to its glucuronide (IX) and sulfate (X). MEL can also be converted to MEL glucuronide (IV), 2-OMEL (V), 3-HMEL (XI), di-HMEL (VI), cNAS glucuronide (XIII), cMEL (XIV), c6-HMEL (XII), and 5-HIAL (XV). AFMK (XVI) and AMK (XVII) pathways are insignificant.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute Intramural Research Program and by a grant for collaborative research from US Smokeless Tobacco Company (to J.R.I.) and in part by National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases) Grant U19 AI067773-02.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online January 10, 2008

Abbreviations: AFMK, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine; AMK, N1-acetyl-5-methoxy-kynuramine; c3-HMEL, cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin; cMEL, cyclic melatonin; c6-HMEL, cyclic 6-hydroxymelatonin; cNAS, cyclic N-acetylserotonin; di-HMEL, dihydroxymelatonin; hCYP1A2, CYP1A2-humanized mice; 5-HIAL, 5-hydroxyindole-3-acetaldehyde; 6-HMEL, 6-hydroxymelatonin; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry; MEL, melatonin; MS/MS, tandem mass spectrometry; NAS, N-acetylserotonin; 2-OMEL, 2-oxomelatonin; OPLS, orthogonal projection to latent surfaces; PCA, principal components analysis; SAL, D-saccharic acid 1,4-lactone; SaMT, 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate; TOFMS, time-of-flight mass spectrometry; UPLC, ultraperformance liquid chromatography; WT, wild type.

References

- Leone RM, Silman RE 1984 Melatonin can be differentially metabolized in the rat to produce N-acetylserotonin in addition to 6-hydroxy-melatonin. Endocrinology 114:1825–1832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young IM, Leone RM, Francis P, Stovell P, Silman RE 1985 Melatonin is metabolized to N-acetyl serotonin and 6-hydroxymelatonin in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 60:114–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopin IJ, Pare CM, Axelrod J, Weissbach H 1960 6-Hydroxylation, the major metabolic pathway for melatonin. Biochim Biophys Acta 40:377–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopin IJ, Pare CM, Axelrod J, Weissbach H 1961 The fate of melatonin in animals. J Biol Chem 236:3072–3075 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis PL, Leone AM, Young IM, Stovell P, Silman RE 1987 Gas chromatographic-mass spectrometric assay for 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate and 6-hydroxymelatonin glucuronide in urine. Clin Chem 33:453–457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone AM, Francis PL, Silman RE 1987 The isolation, purification, and characterisation of the principal urinary metabolites of melatonin. J Pineal Res 4:253–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Idle JR, Krausz KW, Tan DX, Ceraulo L, Gonzalez FJ 2006 Urinary metabolites and antioxidant products of exogenous melatonin in the mouse. J Pineal Res 40:343–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene DJ, Timbers SE, Middleton B, English J, Kopp C, Tobler I, Ioannides C 2006 Mice convert melatonin to 6-sulphatoxymelatonin. Gen Comp Endocrinol 147:371–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennaway DJ, Voultsios A, Varcoe TJ, Moyer RW 2002 Melatonin in mice: rhythms, response to light, adrenergic stimulation, and metabolism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282:R358–R365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peniston-Bird JF, Di WL, Street CA, Edwards R, Little JA, Silman RE 1996 An enzyme immunoassay for 6-sulphatoxy-melatonin in human urine. J Pineal Res 20:51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Meng L, Ma X, Krausz KW, Pommier Y, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ 2006 Urinary metabolite profiling reveals CYP1A2-mediated metabolism of NSC686288 (aminoflavone). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 318:1330–1342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri S, Idle JR, Chen C, Zabriskie TM, Krausz KW, Gonzalez FJ 2006 A metabolomic approach to the metabolism of the areca nut alkaloids arecoline and arecaidine in the mouse. Chem Res Toxicol 19:818–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri S, Krausz KW, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ 2007 The metabolomics of (±)-arecoline 1-oxide in the mouse and its formation by human flavin-containing monooxygenases. Biochem Pharmacol 73:561–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone AM, Francis PL, McKenzie-Gray B 1988 Rapid and simple synthesis for the sulphate esters of 6-hydroxy-melatonin and N-acetyl-serotonin. J Pineal Res 5:367–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang HC, Li H, McKinnon RA, Duffy JJ, Potter SS, Puga A, Nebert DW 1996 Cyp1a2(−/−) null mutant mice develop normally but show deficient drug metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:1671–1676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung C, Ma X, Krausz KW, Kimura S, Feigenbaum L, Dalton TP, Nebert DW, Idle JR, Gonzalez FJ 2005 Differential metabolism of 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (PhIP) in mice humanized for CYP1A1 and CYP1A2. Chem Res Toxicol 18:1471–1478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois G, Turpin J, Baumann N 1976 p-Nitrocatechol sulfate for arylsulfatase assay: detection of metachromatic leukodystrophy variants. Adv Exp Med Biol 68:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szasz G 1967 Comparison between p-nitrophenyl glucuronide and phenolphthalein glucuronide as substrates in the assay of β-glucuronidase. Clin Chem 13:752–759 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Idle JR, Krausz KW, Gonzalez FJ 2005 Metabolism of melatonin by human cytochromes p450. Drug Metab Dispos 33:489–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naguib M, Gottumukkala V, Goldstein PA 2007 Melatonin and anesthesia: a clinical perspective. J Pineal Res 42:12–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh Kumar PN, Andrade C, Bhakta SG, Singh NM 2007 Melatonin in schizophrenic outpatients with insomnia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 68:237–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills E, Wu P, Seely D, Guyatt G 2005 Melatonin in the treatment of cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis. J Pineal Res 39:360–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weishaupt JH, Bartels C, Polking E, Dietrich J, Rohde G, Poeggeler B, Mertens N, Sperling S, Bohn M, Huther G, Schneider A, Bach A, Siren AL, Hardeland R, Bahr M, Nave KA, Ehrenreich H 2006 Reduced oxidative damage in ALS by high-dose enteral melatonin treatment. J Pineal Res 41:313–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara S, Marks T, Hudson DJ, Menaker M 1986 Genetic control of melatonin synthesis in the pineal gland of the mouse. Science 231:491–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gall C, Lewy A, Schomerus C, Vivien-Roels B, Pevet P, Korf HW, Stehle JH 2000 Transcription factor dynamics and neuroendocrine signalling in the mouse pineal gland: a comparative analysis of melatonin-deficient C57BL mice and melatonin-proficient C3H mice. Eur J Neurosci 12:964–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfatti MA, Kulp KS, Knize MG, Davis C, Massengill JP, Williams S, Nowell S, MacLeod S, Dingley KH, Turteltaub KW, Lang NP, Felton JS 1999 The identification of [2-(14)C]2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine metabolites in humans. Carcinogenesis 20:705–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre G, Combalbert J, Berger Y, Cano JP 1990 Human hepatocytes as a key in vitro model to improve preclinical drug development. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 15:165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez FJ 2002 Transgenic models in xenobiotic metabolism and toxicology. Toxicology 181–182:237–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martignoni M, Groothuis GM, de Kanter R 2006 Species differences between mouse, rat, dog, monkey and human CYP-mediated drug metabolism, inhibition and induction. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2:875–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu AM, Idle JR, Byrd LG, Krausz KW, Kupfer A, Gonzalez FJ 2003 Regeneration of serotonin from 5-methoxytryptamine by polymorphic human CYP2D6. Pharmacogenetics 13:173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt S, Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Hardeland R, Cabrera J, Karbownik M 2001 DNA oxidatively damaged by chromium(III) and H(2)O(2) is protected by the antioxidants melatonin, N(1)-acetyl-N(2)-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine, resveratrol and uric acid. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 33:775–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan DX, Manchester LC, Burkhardt S, Sainz RM, Mayo JC, Kohen R, Shohami E, Huo YS, Hardeland R, Reiter RJ 2001 N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine, a biogenic amine and melatonin metabolite, functions as a potent antioxidant. FASEB J 15:2294–2296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida EA, Martinez GR, Klitzke CF, de Medeiros MH, Di Mascio P 2003 Oxidation of melatonin by singlet molecular oxygen [O2(1deltag)] produces N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynurenine. J Pineal Res 35:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozov SV, Filatova EV, Orlov AA, Volkova AV, Zhloba AR, Blashko EL, Pozdeyev NV 2003 N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine is a product of melatonin oxidation in rats. J Pineal Res 35:245–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva SO, Rodrigues MR, Carvalho SR, Catalani LH, Campa A, Ximenes VF 2004 Oxidation of melatonin and its catabolites, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine and N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine, by activated leukocytes. J Pineal Res 37:171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata F, Hayaishi O, Tokuyama T, Seno S 1974 In vitro and in vivo formation of two new metabolites of melatonin. J Biol Chem 249:1311–1313 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisimov VN 2003 Effects of exogenous melatonin—a review. Toxicol Pathol 31:589–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Pandya R, Hooton N, Tjosvold L, Hartling L, Baker G, Vohra S, Klassen T 2004 Melatonin for treatment of sleep disorders. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agozzino P, Avellone G, Bongiorno D, Ceraulo L, Filizzola F, Natoli MC, Livrea MA, Tesoriere L 2003 Melatonin: structural characterization of its non-enzymatic mono-oxygenate metabolite. J Pineal Res 35:269–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan DX, Manchester LC, Reiter RJ, Plummer BF, Hardies LJ, Weintraub ST, Vijayalaxmi, Shepherd AM 1998 A novel melatonin metabolite, cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin: a biomarker of in vivo hydroxyl radical generation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 253:614–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]