Abstract

In ruminants, progesterone (P4) from the ovary and interferon tau (IFNT) from the elongating blastocyst regulate expression of genes in the endometrium that are hypothesized to be important for uterine receptivity and blastocyst development. These studies determined effects of the estrous cycle, pregnancy, P4, and IFNT on hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) expression in the ovine uterus. HIF1A mRNA, HIF2A mRNA, and HIF2A protein were most abundant in the endometrial luminal and superficial glandular epithelia (LE and sGE, respectively) of the uterus and conceptus trophectoderm. During the estrous cycle, HIF1A and HIF2A mRNA levels were low to undetectable on d 10 in the endometrial LE/sGE, increased between d 10 and 14, and then declined on d 16. Both HIF1A and HIF2A mRNA were more abundant in the endometrial LE/sGE of pregnant ewes. However, HIF3A, HIF1B, HIF2B, and HIF3B mRNA abundance was low in most cell types of the endometria and conceptus. Treatment of ovariectomized ewes with P4 induced HIF1A and HIF2A in the endometrial LE/sGE, and intrauterine infusion of ovine IFNT further increased HIF2A in P4-treated ewes, but not in ewes treated with P4 and the antiprogestin ZK 136,317. HIF3A, HIF1B, HIF2B, and HIF3B mRNA abundance was not regulated by either P4 or IFNT. Two HIF-responsive genes, carboxy-terminal domain 2 and vascular endothelial growth factor A, were detected in both the endometrium and conceptus. These studies identified new P4-induced (HIF1A and HIF2A) and IFNT-stimulated (HIF2A) genes in the uterine LE/sGE, and implicate the HIF pathway in regulation of endometrial epithelial functions and angiogenesis, as well as peri-implantation blastocyst development.

IN SHEEP, ENDOMETRIAL functions during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy are primarily regulated by progesterone (P4) from the corpus luteum (CL) and factors from the conceptus (embryo/fetus and associated membranes), including interferon tau (IFNT) (1,2,3). IFNT, the signal for maternal recognition of pregnancy in ruminants, is produced between d 10 and 25 of pregnancy by the mononuclear trophectoderm cells of the ovine conceptus (3). The antiluteolytic actions of IFNT are required to maintain functional CL for secretion of P4, the essential hormone of pregnancy (4,5). IFNT induces or stimulates expression of a number of genes in the uterus, termed IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), that are hypothesized to play important biological roles in uterine receptivity and conceptus implantation (3,6,7). Most of the classical ISGs, such as ISG15, 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetases (OAS1, OAS2, and OAS3), and beta-2-microglobulin, are induced or increased only in stroma cells and the epithelia of middle to deep glands in the ovine uterus. However, several nonclassical ISGs, including wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 7A (WNT7A) (8), galectin 15 (LGALS15) (9), cathepsin L (CTSL) (10), and cystatin C (CST3) (11), are induced or increased by IFNT specifically in luminal epithelium (LE)/superficial glandular epithelium (sGE) of the endometrium, and implicated in regulation of uterine receptivity and conceptus development (7,12). Our recent transcriptional profiling studies identified hypoxia-inducible factor 1A (HIF1A) as a candidate gene in the ovine endometrium regulated by P4 and IFNT (13).

The HIFs are transcription factors that regulate genes to facilitate adaptation and survival of cells, tissue, organs, and whole organisms under conditions ranging from normoxia to hypoxia (14). HIF proteins are members of a larger, evolutionarily conserved group of proteins known as basic helix-loop-helix Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS) proteins (15,16). The HIF family is comprised of three α-subunits [HIF1A, HIF2A/endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), and HIF3A] and three β-subunits [arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator HIF1B/ARNT, HIF2B/ARNT2, and HIF3B/ARNT3. HIF1A was initially discovered by identification of a hypoxia response element (HRE) (5′-RCGTG-3′) in the 3′ enhancer of the erythropoietin (EPO) gene that is induced in response to hypoxia (17). The heterodimeric protein complex that binds to the HRE consists of an inducible α-subunit and a constitutively expressed β-subunit. In many tissues and cell types, HIF1A is up-regulated in response to hypoxia, and elicits multiple physiological responses, including erythropoiesis and glycolysis, to counteract oxygen deficiency and stimulate angiogenesis as a long-term solution to hypoxia (18). HIF2A is closely related to HIF1A (19,20). HIF2A shares 48% amino acid identity to HIF1A, and a number of structural and biochemical similarities such as heterodimerization with ARNT/HIF1B and binding to HREs. In contrast to HIF1A, HIF2A is predominantly expressed in highly vascularized tissues such as heart, lung, and placenta (19). HIF3A is also expressed in a variety of tissues, dimerizes with ARNT/HIF1B, and binds to HREs (21). Over 200 genes respond to HIF, including EPO, CBP/p300-interacting transactivator with Glu/Asp-rich carboxy-terminal domain 2 (CITED2), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), solute carrier family 2 [facilitated glucose transporter (GLUT) member 1 (SLC2A1; also termed GLUT1)], and IGF2. Emerging evidence indicates that HIF1A and HIF2A have different target genes, although both induce common genes such as VEGFA (22,23).

Mice deficient in Hif1a, Hif2a, or Arnt/Hif1b die at midgestation of vascular defects primarily involving embryonic and extraembryonic vasculature (24,25,26,27,28,29,30). In contrast, mice deficient in Hif2b or Hif3b do not exhibit vascular abnormalities (31,32). These results suggest that Vegfa is primarily regulated by HIF1A, HIF2A, and ARNT/HIF1B during embryonic development. The role of HIFs in regulating VEGFA and, thus, angiogenesis in tumors has been clearly documented (33,34). In the peri-implantation mouse uterus, HIFs are expressed in a cell-specific manner in response to ovarian steroid hormones (35); P4 stimulated Hif1a expression in the uterine LE, and estrogen stimulated Hif2a in uterine stroma. Little information is available on HIFs in other mammalian uteri.

With the exception of identifying HIF1A as a potential P4- and IFNT-stimulated gene in the ovine endometrium (13), HIFs have not been studied in the ovine uterus. Therefore, these studies were conducted to determine: 1) temporal and cell-specific changes in expression of the HIF genes in the ovine endometrium during the estrous cycle and early pregnancy; 2) effects of P4 and IFNT on HIF expression in endometria of ovine uteri; and 3) expression of selected HIF-regulated genes, CITED2 and VEGFA, in ovine uteri during the peri-implantation period of pregnancy. Results indicate that HIF1A and HIF2A are induced in endometrial LE/sGE by P4, HIF2A is also stimulated by IFNT, and CITED2 and VEGFA are expressed in endometria and conceptus trophectoderm. Thus, the HIF system is a candidate mediator of P4 and IFNT actions to establish uterine receptivity, regulate endometrial epithelial functions and angiogenesis, and promote blastocyst development in sheep.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mature crossbred Suffolk ewes (Ovis aries) were observed daily for estrus in the presence of vasectomized rams and used in experiments only after they had exhibited at least two estrous cycles of normal duration (16–18 d). All experimental and surgical procedures were in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Agriculture Animals in Research and Teaching and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Texas A&M University.

Experimental design

Study 1.

At estrus (d 0), ewes were mated to either an intact or vasectomized ram and then hysterectomized (n = 5 ewes per d) on either d 10, 12, 14, or 16 of the estrous cycle, or d 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, or 20 of pregnancy as described previously (36). At hysterectomy the uterus was flushed with 20 ml sterile saline. Pregnancy was confirmed on d 10–16 after mating by the presence of a morphologically normal conceptus(es) in the uterine flushing. It was not possible to obtain uterine flushing on either d 18 or 20 of pregnancy because the conceptus had firmly adhered to the endometrial LE and basal lamina. At hysterectomy several sections (∼0.5 cm) from the midportion of each uterine horn ipsilateral to the CL were fixed in fresh 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.2). After 24 h fixed tissues were changed to 70% (vol/vol) ethanol for 24 h, dehydrated through a graded series of alcohol to xylene, and then embedded in Paraplast-Plus (Oxford Labware, St. Louis, MO). The remaining endometrium was physically dissected from myometrium, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 C for subsequent RNA extraction. In monovulatory pregnant ewes, uterine tissue samples were marked as either contralateral or ipsilateral to the ovary bearing the CL, and only tissues from the ipsilateral uterine horn were used in subsequent analyses.

Study 2.

In study 2, cyclic ewes (n = 20) were checked daily for estrus and then ovariectomized and fitted with indwelling uterine catheters on d 5 as described previously (37). Ewes were then assigned randomly (n = 5 per treatment) to receive daily im injections of P4 and/or a P4 receptor (PGR) antagonist (ZK 136,317; Schering AG, Berlin, Germany), and intrauterine (iu) infusions of control (CX) serum proteins and/or recombinant ovine IFNT protein as follows: 1) 50 mg P4 (d 5–16) and 200 μg CX serum proteins (d 11–16) (P4 + CX); 2) P4 and 75 mg ZK 136,317 (d 11–16) and CX proteins (P4 + ZK + CX); 3) P4 and IFNT (2 × 107 antiviral units, d 11–16) (P4 + IFN); or 4) P4 and ZK and IFNT (P4 + ZK + IFN). Steroids were administered im daily in corn oil vehicle. Both uterine horns of each ewe received twice daily injections of either CX proteins (50 μg per horn per injection) or recombinant ovine IFNT (5 × 106 antiviral units per horn per injection). Recombinant ovine IFNT was produced in Pichia pastoris and purified as described previously (38). For preparation of protein injections, serum proteins were obtained from a d-6 cyclic ewe as described previously (39). Jugular vein blood was collected and allowed to clot at room temperature for 1 h and then overnight at 4 C. Serum was collected by centrifugation at 3000 × g for 30 min at 4 C, filtered (0.45 μm), and stored at −20 C. The bicinchoninic assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) was used for protein quantification with BSA as the standard. This regimen of P4 and recombinant ovine IFNT mimics the effects of P4 and IFNT from the conceptus on endometrial expression of hormone receptors and IFNT-stimulated genes during early pregnancy in ewes (39,40,41). All ewes were hysterectomized on d 17, and uteri were processed as described for study 1.

RNA isolation

Total cellular RNA was isolated from frozen endometria using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.-BRL, Bethesda, MD) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. The quantity and quality of total RNA were determined by spectrometry and denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively.

Cloning of partial cDNAs for ovine endometrial HIF1A, HIF2A, HIF3A, HIF1B, HIF2B, HIF3B, CITED2, and VEGFA

Partial cDNAs for ovine HIF1A, HIF2A, HIF3A, HIF1B, HIF2B, HIF3B, CITED2, and VEGFA mRNAs were amplified by RT-PCR using total RNA from endometria of d-16 or -18 pregnant ewes using specific primers (Table 1) and methods described previously (42). PCR amplification was conducted as follows for ovine HIF1A, HIF2A/EPAS1, HIF3A, ARNT/HIF1B, HIF2B/ARNT2, HIF3B/ARNT3, VEGFA, and CITED2: 1) 95 C for 5 min; 2) 95 C for 45 sec, 54.2 C for 1 min (for ARNT/HIF1B), 56.5 C (HIF1A, HIF3A, HIF2B), or 59.1 C (HIF2A, HIF3B, CITED2, VEGFA), and 72 C for 1 min for 35 cycles; and 3) 72 C for 10 min. The partial cDNAs of the correct predicted size were cloned into pCRII using a T/A Cloning Kit (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), and the sequence of each was verified using an ABI PRISM Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit and ABI PRISM automated DNA sequencer (PerkinElmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR and cloning

| Gene | Sequence (5′→3′): forward and reverse | GenBank accession no. | cDNA size (nt) | Homology to bovine and human mRNAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIF1A | TCA GCT ATT TGC GTG TGA GG | EU340260 | 445 | 97%, 94% |

| TTC ACA AAT CAG CAC CAA GC | ||||

| HIF2A/EPAS1 | AAG TCA GCC ACC TGG AAG G | EU340261 | 427 | 98%, 92% |

| TCA CAC ACA TGA TGC ACT GG | ||||

| HIF3A | CTG GAC GGG ACT TCA GTA GC | EU340262 | 286 | 95%, 80% |

| CTC TGC CTC GTC TTC TGA GC | ||||

| ARNT/HIF1B | AGA TGC AGG AAT GGA CTT GG | EU340263 | 363 | 98%, 95% |

| CCT GGC CTT TTA ACT TCA CG | ||||

| HIF2B/ARNT2 | AGG ATG AGG TGT GGA AAT GC | EU340264 | 375 | 97%, 91% |

| CCT CAG AGT GGC AGA ACT CC | ||||

| HIF3B/ARNT3 | GAG GGC AAC AGC TAT TTT GG | EU340265 | 438 | 98%, 94% |

| AGG CGA TGA CCC TCT TAT CC | ||||

| CITED2 | CCA TAT GAT GGC CAT GAA CC | EU340266 | 354 | 98%, 95% |

| GTA GTG GTT GTG GGG GTA GG | ||||

| VEGFA | CAG AAG GAG GGC AGA AAC C | EU340267 | 431 | 98%, 94% |

| TCA CAT CTG CAA GTA CGT TCG |

Slot blot hybridization analyses

Steady-state levels of mRNA in ovine endometria were assessed by slot blot hybridization as described previously (40). Radiolabeled antisense cRNA probes were generated by in vitro transcription using linearized plasmid template, RNA polymerases, and [α-32P]uridine 5′-triphosphate. Denatured total endometrial RNA (20 μg) from each ewe was hybridized with radiolabeled cRNA probes. To correct for variation in total RNA loading, a duplicate RNA slot membrane was hybridized with radiolabeled antisense 18S cRNA (pT718S; Ambion, Austin, TX). After washing, the blots were digested with ribonuclease A and radioactivity associated with slots quantified using a Typhoon 8600 MultiImager (Molecular Dynamics, Piscataway, NJ). Data are expressed as relative units (RUs).

In situ hybridization analyses

Location of mRNA in sections (5 μm) of ovine uterine endometria was determined by radioactive in situ hybridization analysis as described previously (40). Radiolabeled antisense or sense cRNA probes were generated by in vitro transcription using linearized plasmid template, RNA polymerases, and [α-35S]uridine 5′-triphosphate. Deparaffinized, rehydrated, and deproteinated uterine tissue sections were hybridized with radiolabeled antisense or sense cRNA probes. After hybridization, washing, and ribonuclease A digestion, slides were dipped in NTB-2 liquid photographic emulsion (Kodak, Rochester, NY), and exposed at 4 C for 1–4 wk. Slides were developed in Kodak D-19 developer, counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific, Fairlawn, NJ), and then dehydrated through a graded series of alcohol to xylene. Coverslips were then affixed with Permount (Fisher Scientific). Images of representative fields were recorded under bright-field or dark-field illumination using a Nikon Eclipse 1000 photomicroscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Lewisville, TX) fitted with a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunocytochemical localization of HIF2A protein in the ovine uterus was performed as described previously (37) and an antihuman HIF2A polyclonal antibody (catalog no. NB100-480; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) at a 1:500 dilution (2.7 μg/ml). Antigen retrieval was performed using the boiling citrate method. Negative controls included substitution of the primary antibody with purified nonimmune rabbit IgG at the same final concentration.

Statistical analyses

All quantitative data were subjected to least-squares regression analyses (ANOVA) using the General Linear Models procedures of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Slot blot hybridization data were corrected for differences in sample loading using the 18S rRNA data as a covariate. Data from study 1 were analyzed for effects of day, pregnancy status (cyclic or pregnant), and their interaction (day × status) for ewes collected on d 10, 12, 14, and 16 after estrus/mating. Effects of day were determined by regression analysis. Data from study 2 were analyzed using preplanned orthogonal contrasts (P4 + CX vs. P4 + IFN, P4 + CX vs. P4 + ZK + CX, and P4 + IFN vs. P4 + ZK + IFN). Data are presented as least squares means with overall ses.

Results

Cloning of partial cDNAs for the ovine HIF system

Partial cDNAs for the different components of the HIF system studied in the ovine endometrium and conceptus were cloned from endometrium using RT-PCR and primers listed in Table 1. Overall, the partial cDNAs were found to be highly homologous to bovine (95–98%) and human (80%–95%) mRNAs.

Effects of estrous cycle and early pregnancy on expression of HIF mRNAs in ovine endometria (study 1)

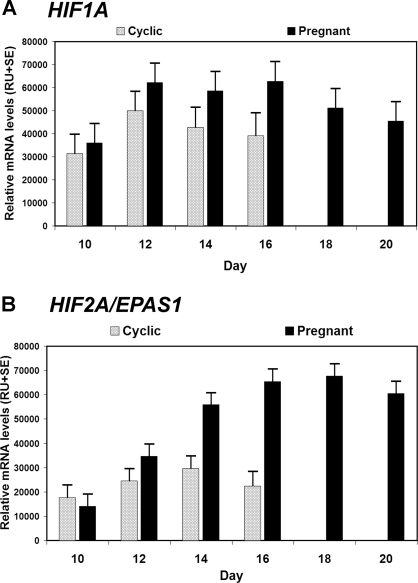

Steady-state levels of ovine HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs in endometria from cyclic and pregnant ewes were affected (P < 0.01) by day, status, and their interaction (Fig. 1). In cyclic ewes, endometrial HIF1A and HIF2A mRNA levels increased (P < 0.01) about 1.3 and 1.7-fold from d 10–14, respectively, and declined to d 16. HIF1A mRNA levels were higher in pregnant than cyclic ewes between d 14 and 16 (P < 0.01; day × status). Endometrial HIF2A mRNA levels increased 4.3-fold between d 10 and 16 of pregnancy, and were higher in pregnant than cyclic ewes on d 14 and 16 (P < 0.01; day × status). HIF2A mRNA levels remained high between d 16 and 20 of pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Steady-state levels of HIF1A and HIF2A/EPAS1 mRNAs in endometria from cyclic and early pregnant ewes as determined by slot blot hybridization analysis. See Materials and Methods for complete description. Both HIF mRNAs were affected (P < 0.01) by day, status, and their interaction. A, HIF1A mRNA in the endometria of cyclic and pregnant ewes (d 10–20). In cyclic ewes, endometrial HIF1A mRNA levels were low on d 10, increased about 1.3-fold from d 10–14, and declined to d 16, and were higher in pregnant than cyclic ewes on d 14 and 16. B, HIF2A mRNA in the endometria of cyclic and early pregnant ewes (d 10–20). In cyclic ewes, endometrial HIF2A mRNA levels were low on d 10, increased about 1.7-fold from d 10–14, and declined to d 16. In contrast, endometrial HIF2A mRNA levels increased 4.3-fold between d 10 and 20 of pregnancy (P < 0.01; day × status).

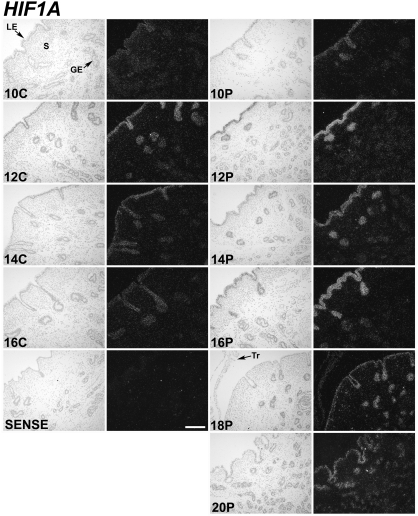

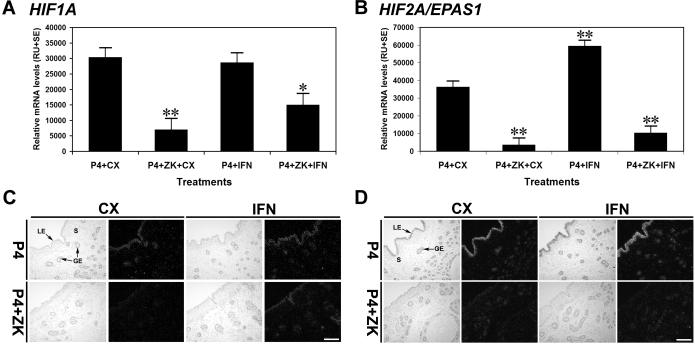

In situ hybridization analyses found that HIF1A and HIF2A mRNA were most abundant in the endometrial epithelia (Figs. 2 and 3). Little or no mRNA was observed in the endometrial stroma, blood vessels, or immune cells as well as myometrium. In cyclic ewes, a transient increase in HIF1A and HIF2A mRNA abundance was observed in LE/sGE between d 10 and 16. In pregnant ewes, HIF1A and HIF2A mRNA increased in endometrial LE/sGE between d 10 and 16, and remained abundant to d 20. On d 18 and 20 of pregnancy, HIF2A mRNA was observed in both LE/sGE and middle to deep glands of the endometrium. Both HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs were also observed in trophectoderm of conceptuses on d 18 and 20 of pregnancy. In contrast to HIF1A and HIF2A, the overall abundance of HIF3A, ARNT/HIF1B, HIF2B, and HIF3B mRNA was low in the endometria of both cyclic (data not shown) and pregnant ewes, and was detected in most cell types of the uterus and conceptus (results can be found in supplemental Fig. 1, which is published as supplemental data on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org).

Figure 2.

In situ hybridization analyses of HIF1A mRNAs in uteri of cyclical and early pregnant ewes. Cross-sections of the uterine wall from cyclic (C) and pregnant (P) ewes were hybridized with radiolabeled antisense or sense ovine HIF1A cRNA probes. See Materials and Methods for complete description. HIF1A mRNA was detectable primarily in endometrial LE, sGE, and conceptus trophectoderm. S, Stroma; Tr, trophectoderm. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Figure 3.

In situ hybridization analyses of HIF2A/EPAS1 mRNAs in uteri of cyclic and early pregnant ewes. Cross-sections of the uterine wall from cyclic (C) and pregnant (P) ewes were hybridized with radiolabeled antisense or sense ovine HIF2A cRNA probes. See Materials and Methods for complete description. HIF2A mRNA was detectable primarily in endometrial LE and sGE, and conceptus trophectoderm. S, Stroma; Tr, trophectoderm. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

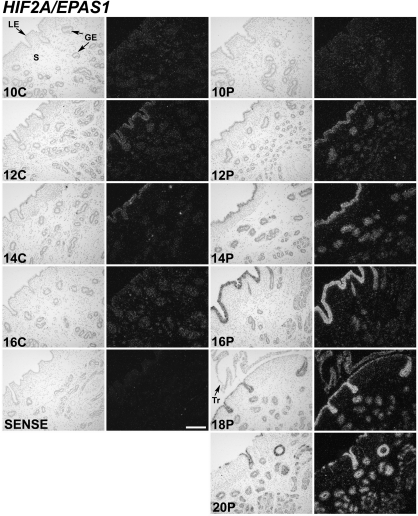

P4 and IFNT regulate endometrial HIF1A and HIF2A (study 2)

To determine if P4 and/or IFNT regulated endometrial HIF1A and HIF2A, cyclic ewes were ovariectomized and fitted with indwelling uterine catheters on d 5, and then treated with P4 or P4 and ZK 136,317 antiprogestin (P4 + ZK), and infused with CX proteins or recombinant ovine IFNT. In ewes receiving iu infusions of CX proteins, P4 induced a 4.4- and 10-fold increase (P < 0.001; P4 + CX vs. P4 + ZK + CX) in endometrial HIF1A and HIF2A mRNA levels, respectively, when compared with ewes receiving P4 + ZK treatment (Fig. 4, A and B). iu infusion of IFNT did not affect (P > 0.10; P4 + CX vs. P4 + IFN) endometrial HIF1A mRNA abundance in P4-treated ewes; however, IFNT infusion increased endometrial HIF1A mRNA in P4 + ZK-treated ewes (P < 0.05; P4 + CX vs. P4 + ZK + IFN). In contrast, iu infusion of IFNT stimulated a 1.6-fold increase (P < 0.001; P4 + CX vs. P4 + IFN) in HIF2A mRNA levels in P4-treated ewes, but not in P4 + ZK-treated ewes (P > 0.10). The effects of P4 and/or IFNT on HIF1A and HIF2A expression were specific to endometrial LE/sGE (Fig. 4, C and D). In contrast, endometrial HIF3A, ARNT/HIF1B, HIF2B, and HIF3B expression was not regulated by either P4 or IFNT (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effects of P4 and IFNT on HIF1A and HIF2A/EPAS1 mRNAs in ovine uteri (study 2). See Materials and Methods for complete description. A and B, Steady-state levels of HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs in endometria as determined by slot blot hybridization analysis. Treatment of ewes with P4 increased both HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs in endometria (P4 + CX vs. P4 + ZK + CX; P < 0.001). iu infusion of IFNT stimulated HIF2A mRNA in the endometrium (P4 + CX vs. P4 + IFN; P < 0.001), but not in ewes receiving the ZK antiprogestin (P4 + ZK + CX vs. P4 + ZK + IFN; P > 0.10). iu infusion of IFNT did not stimulate HIF1A mRNA in endometria of ewes treated with P4 only (P4 + CX vs. P4 + IFN; P > 0.10) or ewes receiving P4 and the ZK antiprogestin (P4 + ZK + CX vs. P4 + ZK + IFN; P > 0.10). The asterisk (*) denotes an effect of treatment (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001). C and D, In situ localization of HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs. Cross-sections of the uterine wall were hybridized with radiolabeled antisense or sense ovine HIF1A and HIF2A cRNA probes. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

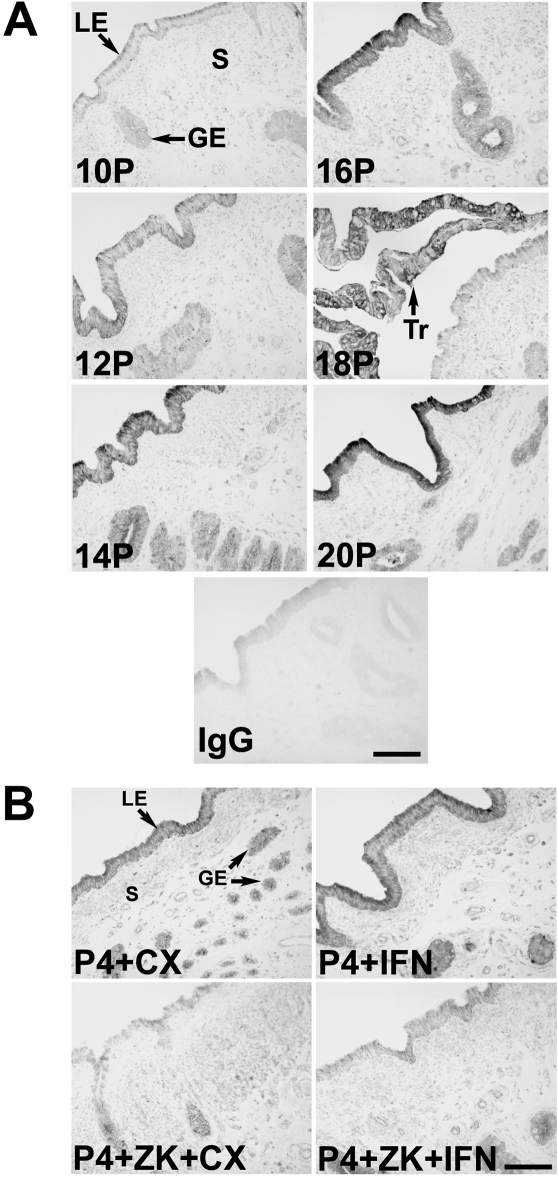

HIF2A protein in the ovine uterus

Western blot analysis of both cytosolic and nuclear extracts from endometrial LE cells with the rabbit antihuman HIF2A polyclonal antibody detected a protein of approximately 116 kDa in size using reducing conditions (data not shown). Consistent with results from in situ hybridization analyses, immunoreactive HIF2A protein was most abundant in endometrial LE/sGE and conceptus trophectoderm of pregnant ewes (Fig. 5A). HIF2A protein appeared to be most abundant in the cytoplasm but was also detected in the nuclei of endometrial LE/glandular epithelium (GE) and conceptus trophectoderm. In study 2, immunoreactive HIF2A protein was most abundant in endometrial LE/sGE of ewes treated with P4 (P4 + CX and P4 + IFN) compared with ewes treated with P4 and the ZK antiprogestin (P4 + ZK + CX and P4 + ZK + IFN) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

HIF2A/EPAS1 protein in endometria from studies 1 (A) and 2 (B). See Materials and Methods for complete description. Immunoreactive HIF2A protein was localized predominantly in endometrial LE and sGE and conceptus trophectoderm using a rabbit antihuman HIF2A polyclonal antibody. For the IgG control, normal rabbit IgG was substituted for the primary antibody. Sections were not counterstained. S, Stroma; Tr, trophectoderm. Scale bar represents 5 μm.

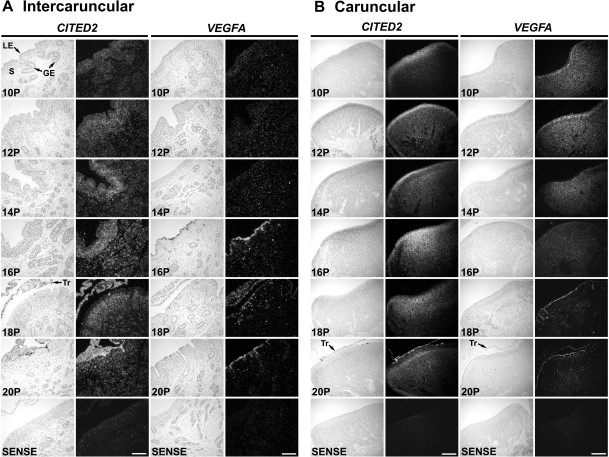

CITED2 and VEGFA in the ovine endometrium and conceptus

CITED2 and VEGFA are HIF-regulated genes (23,43,44,45,46). Between d 10 and 20 of pregnancy, CITED2 mRNA was detected in all endometrial cell types but was particularly abundant in the subepithelial stroma of the intercaruncular and caruncular areas of the endometrium (Fig. 6). Between d 10 and 14 of pregnancy, VEGFA mRNA was detected at a low abundance in stromal cells of the intercaruncular endometrium and not in LE/sGE; however, VEGFA mRNA was particularly abundant in stromal cells in endometrial caruncles. Interestingly, VEGFA mRNA was detected in the endometrial LE/sGE of the intercaruncular endometrium on d 16–20 of pregnancy, and in LE of caruncular endometrium on d 18 and 20. Moreover, the abundance of VEGFA mRNA declined in caruncular stromal cells after d 14 of pregnancy. Both CITED2 and VEGFA mRNA were observed in the conceptus trophectoderm on d 18 and 20 of pregnancy (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

In situ hybridization analyses of CITED2 and VEGFA mRNAs in intercaruncular (A) and caruncular (B) endometria of uteri from early pregnant ewes. Cross-sections of the uterine wall from pregnant (P) ewes were hybridized with radiolabeled antisense or sense ovine CITED2 and VEGFA cRNA probes. S, Stroma; Tr, trophectoderm. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

Discussion

We initially identified HIF1A as a potential P4-regulated gene in ovine endometria using transcriptional profiling (13). Results of the present studies validate that study, and support the hypothesis that transcription of HIF1A and HIF2A genes in endometrial LE/sGE is increased by ovarian P4. Similarly in the mouse uterus, Hif1a is also up-regulated by P4 in LE/sGE (35). However, the induction of Hif1a in uterine LE on d-4 gestation in mice is immediately after loss of PGRs from those cells (47), and activity of the Hif1a promoter was not directly stimulated by liganded PGR (35). Thus, P4 induction of HIF1A may be indirect. In the present study, the increase in HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs in the LE/sGE between d 10 and 12 after estrus/mating in study 1 is coincident with the loss of PGR mRNA and protein in the epithelia (39,48). Furthermore, the decrease in HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs in LE/sGE between d 14 and 16 of the cycle is coincident with the reappearance of PGR protein in endometrial LE/sGE. In fact, continuous exposure of the sheep uterus to P4 for about 10 d down-regulates PGR mRNA and PGR protein in endometrial LE and sGE, but not stroma or myometrium (49). In the present study, HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs were detected in endometrial LE/sGE of P4-treated ewes, but not in ewes treated with P4 and the PGR antagonist ZK 136,317. PGRs are present in the endometrial epithelia of P4 + ZK-treated sheep (49) because PGR antagonists prevent P4 from down-regulating expression of its own receptor. Consequently, P4 induction of HIF1A and HIF2A mRNAs in uterine LE/sGE may be attributed, at least in part, to the P4-induced loss of PGR in those epithelia (2,50). Indeed, PGR loss in endometrial epithelia is associated with the induction of or increase in expression of genes (LGALS15, CTSL, CST3, HIF1A, HIF2A) in endometrial LE/sGE and other genes (STC1, SPP1, UTMP) in the middle to deep GE that are implicated in uterine receptivity and conceptus implantation (2). Although the LE and GE cease to express the PGR during most of gestation, P4 is hypothesized to act on PGR-positive stromal cells to induce growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor 7, fibroblast growth factor 10, and/or hepatocyte growth factor, that regulate expression of epithelial genes (2,51). Thus, antiprogestins prevent both the loss of the PGR from endometrial epithelia and stromal-derived progestamedins, resulting in nonreceptive uteri. Understanding the transcriptional regulation of HIF1A and HIF2A in the uterine LE could reveal novel cellular and molecular pathways that mediate cross talk between ovarian hormones and stromal growth factors.

We originally identified HIF1A as a P4- and IFNT-stimulated gene by microarray analysis of endometria from the same ewes used for study 2 (13). That study found that HIF1A was up-regulated 2.6-fold in endometria of P4 + CX compared with P4 + ZK + CX ewes, and this result was validated in the present study using slot blot and in situ hybridization analyses. However, our previous microarray study found that IFNT infusion increased HIF1A mRNA by 2.7-fold in P4-treated ewes (13), but the present studies did not validate that finding. Thus, the higher abundance of HIF1A mRNA in the uterine LE/sGE of pregnant compared with cyclic ewes between d 12 and 16 is not due to conceptus-derived IFNT. However, one may speculate that higher levels of HIF1A mRNA in endometrial LE/sGE of early pregnant ewes are due to local hypoxia during this period of rapid growth of the conceptus or perhaps another factor from the conceptus, such as prostaglandin E2 (52). Indeed, Critchley et al. (53) recently reported that prostaglandin E2 up-regulated HIF1A mRNA and protein via the E-series prostaglandin E receptor 2 in human endometrium.

The present studies discovered that HIF2A is another nonclassical IFNT-stimulated gene in endometrial LE/sGE. During early pregnancy, HIF2A mRNA abundance in endometrial LE/sGE paralleled increases in production of IFNT by the elongating conceptus, which is maximal on d 16 (54,55). In addition, iu administration of recombinant ovine IFNT increased HIF2A mRNA in P4, but not P4 + ZK-treated ewes. The inability of IFNT to stimulate HIF2A expression in ewes treated with the ZK antiprogestin is likely due to the absence of P4 priming and progestamedins from stromal cells that are hypothesized to act on LE/sGE to regulate their responsiveness to IFNT (1,2). The signaling pathway whereby IFNT regulates transcription of the HIF2A gene is not known, but it clearly does not involve the classical janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway because signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 is not expressed in LE/sGE of ovine uteri during pregnancy (56). To date, CST3, CTSL, WNT7A, and LGALS15 are the only other genes identified in endometrial LE/sGE that are induced or stimulated by IFNT in progestinized ewes (8,9,10,11). Thus, the pleiotropic actions of IFNT on endometrial LE/sGE include repression of genes, such as estrogen receptor α (ESR1) to abrogate the development of the luteolytic mechanism, and stimulation of genes that are hypothesized to be involved in uterine receptivity and conceptus growth and differentiation (2,7). Knowledge of mechanisms whereby IFNT stimulates HIF2A expression in endometrial LE/sGE is expected to help unravel nonclassical cell signaling pathway(s) for IFNT and other type I IFNs.

Although HIF-regulated genes have been studied in other cells, tissues, and animal models (14,18,46,57,58), few of the genes known to be regulated by HIF1A and HIF2A have been studied in the ovine uterus. In the present studies, two HIF-regulated genes, CITED2 and VEGFA, were found to be expressed in both ovine endometria and concepti. Both the HIFs and the HIF-regulated genes were abundantly expressed in the conceptus, and Hifs as well as Vegfa and Cited2 play important biological roles in the formation and development of the placenta in mice (19,26,59,60,61). VEGFA has a paramount role in angiogenesis that involves vasodilation and endothelial sprouting and outgrowth (62,63,64). CITED2 binds CBP/p300 and interacts with a variety of transcription factors (65), including some critical to trophoblast formation and vascularization of the placenta (61). In the present studies, temporal and spatial alterations in CITED2 mRNA were not consistent with direct regulation by HIF1A or HIF2A in the endometrial LE/sGE because CITED2 mRNA was predominantly observed in stromal cells of the intercaruncular and caruncular areas of the endometrium. However, the appearance of VEGFA mRNA in the intercaruncular LE/sGE and then caruncular LE was coincident with maximal increases in HIF2A mRNA and IFNT production by ovine conceptuses. The biological roles of epithelial VEGFA may be manifest on either the subepithelial stroma and/or conceptus. In rodents, endometrial Vegfa mRNA is predominantly limited to LE in response to estrogen, and Vegfa protein is secreted apically into uterine lumen (63,66,67). However, Vegfa could also be secreted in an endocrine manner and act on blood vessels within the endometrial stroma. VEGFA clearly plays a central role in increasing microvascular permeability and angiogenesis (68). During early pregnancy in sheep, blood flow increases to the uterus approximately 2-fold between d 10 and 20 of early pregnancy (69,70), which could be driven by VEGFA from the LE/sGE and conceptus trophectoderm. The loss of VEGFA from the endometrial caruncles between d 10 and 20 of early pregnancy is difficult to explain, particularly because angiogenesis in the caruncles is important to establish delivery of gases and micronutrients to the conceptus as maternal caruncles and placental cotyledons form placentomes (71), and VEGFA clearly increases in abundance in placentomes during gestation (72). The reduction in VEGFA in the caruncular stroma and concomitant induction in the endometrial LE/sGE occurs before placentome formation and during initial vascularization of the placenta. Thus, the focal production of VEGFA by the endometrial LE may be necessary to stimulate chorionic rather than caruncular angiogenesis. In addition to VEGFA, the temporal and spatial alterations in SLC2A1/GLUT1 and IGF2 expression in endometrial LE/sGE (Kim, J., H. Gao, T. E. Spencer, and F. W. Bazer, unpublished results) are consistent with regulation by P4 and/or IFNT via HIF2A and perhaps HIF1A (22,23).

Collectively, these studies have identified new P4-induced (HIF1A and HIF2B) and IFNT-stimulated (HIF2A) genes in the endometrial LE/sGE that are also present in the conceptus. In the developing ovine conceptus, the HIFs are undoubtedly involved in placental development because mice deficient in Hif1a, Hif2a, or Arnt/Hif1b die at midgestation of vascular defects primarily involving embryonic and extraembryonic vasculature (24,25,26,27,28,29,30). In addition to mediating developmental and physiological pathways that deliver oxygen or allow cells to survive oxygen deprivation, the HIFs regulate hundreds of genes (73). The temporal changes in HIF expression during early pregnancy suggest that this pathway may regulate the response of the endometrial LE/sGE to IFNT, and also trophectoderm growth and differentiation that is independent of well-established roles of the HIF pathway in angiogenesis. Future studies will focus on mechanisms whereby HIF genes are regulated by P4 and/or IFNT in the endometrium, the role of HIF2A and HIF1A in mediating the effects of IFNT on the uterine LE/sGE, and the biological roles of the HIF pathway and HIF-regulated genes in uteroplacental angiogenesis, endometrial epithelial cell functions, peri-implantation uterine receptivity, and conceptus growth and differentiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the Laboratory for Uterine Biology and Pregnancy for assistance and management of animals. We also thank Drs. Robert C. Burghardt and Greg A. Johnson for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants 5 R01 HD32534 and 5 P30 ES09106.

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online January 3, 2008

Abbreviations: ARNT, Arylhydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator; CITED2, carboxy-terminal domain 2; CL, corpus luteum; CST3, cystatin C; CTSL, cathepsin L; CX, control; EPAS1, endothelial PAS acid domain protein 1; GE, glandular epithelium; GLUT, glucose transporter; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; HRE, hypoxia response element; IFNT, interferon tau; ISG, interferon-stimulated gene; iu, intrauterine; LE, luminal epithelium; LGALS15, galectin 15; OAS, 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase; P4, progesterone; PGR, progesterone receptor; RU, relative unit; sGE, superficial glandular epithelium; VEGFA, vascular endothelial growth factor A.

References

- Spencer TE, Bazer FW 2002 Biology of progesterone action during pregnancy recognition and maintenance of pregnancy. Front Biosci 7:d1879–d1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Bazer FW 2004 Progesterone and placental hormone actions on the uterus: insights from domestic animals. Biol Reprod 71:2–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Johnson GA, Bazer FW, Burghardt RC 2007 Fetal-maternal interactions during the establishment of pregnancy in ruminants. Soc Reprod Fertil Suppl 64:379–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer FW 1992 Mediators of maternal recognition of pregnancy in mammals. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 199:373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazer FW, Spencer TE, Ott TL 1997 Interferon tau: a novel pregnancy recognition signal. Am J Reprod Immunol 37:412–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen TR, Austin KJ, Perry DJ, Pru JK, Teixeira MG, Johnson GA 1999 Mechanism of action of interferon-tau in the uterus during early pregnancy. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 54:329–339 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Sandra O, Wolf E Genes involved in conceptus-endometrial interactions in ruminants: insights from reductionism and thoughts on holistic approaches. Reproduction, in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Choi Y, Bazer FW, Spencer TE 2003 Identification of genes in the ovine endometrium regulated by interferon τ independent of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1. Endocrinology 144:5203–5214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CA, Adelson DL, Bazer FW, Burghardt RC, Meeusen EN, Spencer TE 2004 Discovery and characterization of an epithelial-specific galectin in the endometrium that forms crystals in the trophectoderm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:7982–7987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Spencer TE, Bazer FW 2005 Cathepsins in the ovine uterus: regulation by pregnancy, progesterone, and interferon τ. Endocrinology 146:4825–4833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G, Spencer TE, Bazer FW 2006 Progesterone and interferon-τ regulate cystatin C in the endometrium. Endocrinology 147:3478–3483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Johnson GA, Bazer FW, Burghardt RC, Palmarini M 2007 Pregnancy recognition and conceptus implantation in domestic ruminants: roles of progesterone, interferons and endogenous retroviruses. Reprod Fertil Dev 19:65–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray CA, Abbey CA, Beremand PD, Choi Y, Farmer JL, Adelson DL, Thomas TL, Bazer FW, Spencer TE 2006 Identification of endometrial genes regulated by early pregnancy, progesterone, and interferon tau in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 74:383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q, Costa M 2006 Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol Pharmacol 70:1469–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews ST 1998 Control of cell lineage-specific development and transcription by bHLH-PAS proteins. Genes Dev 12:607–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL 1995 Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:5510–5514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL, Nejfelt MK, Chi SM, Antonarakis SE 1991 Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3′ to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:5680–5684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL 1998 Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: master regulator of O2 homeostasis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8:588–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, Sogawa K, Matsuda Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y 1997 A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:4273–4278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, McKnight SL, Russell DW 1997 Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev 11:72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu YZ, Moran SM, Hogenesch JB, Wartman L, Bradfield CA 1998 Molecular characterization and chromosomal localization of a third alpha-class hypoxia inducible factor subunit, HIF3alpha. Gene Expr 7:205–213 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covello KL, Kehler J, Yu H, Gordan JD, Arsham AM, Hu CJ, Labosky PA, Simon MC, Keith B 2006 HIF-2alpha regulates Oct-4: effects of hypoxia on stem cell function, embryonic development, and tumor growth. Genes Dev 20:557–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CJ, Iyer S, Sataur A, Covello KL, Chodosh LA, Simon MC 2006 Differential regulation of the transcriptional activities of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 26:3514–3526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer NV, Leung SW, Semenza GL 1998 The human hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha gene: HIF1A structure and evolutionary conservation. Genomics 52:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL 2000 HIF-1: mediator of physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 88:1474–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan HE, Lo J, Johnson RS 1998 HIF-1 alpha is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO J 17:3005–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltepe E, Schmidt JV, Baunoch D, Bradfield CA, Simon MC 1997 Abnormal angiogenesis and responses to glucose and oxygen deprivation in mice lacking the protein ARNT. Nature 386:403–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adelman DM, Gertsenstein M, Nagy A, Simon MC, Maltepe E 2000 Placental cell fates are regulated in vivo by HIF-mediated hypoxia responses. Genes Dev 14:3191–3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak KR, Abbott B, Hankinson O 1997 ARNT-deficient mice and placental differentiation. Dev Biol 191:297–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Zhang L, Drysdale L, Fong GH 2000 The transcription factor EPAS-1/hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha plays an important role in vascular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:8386–8391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya T, Oda Y, Takahashi S, Morita M, Kawauchi S, Ema M, Yamamoto M, Fujii-Kuriyama Y 2001 Defective development of secretory neurones in the hypothalamus of Arnt2-knockout mice. Genes Cells 6:361–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowden KD, Simon MC 2002 The bHLH/PAS factor MOP3 does not participate in hypoxia responses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 290:1228–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger RH, Camenisch G, Desbaillets I, Chilov D, Gassmann M 1998 Up-regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is not sufficient for hypoxic/anoxic p53 induction. Cancer Res 58:5678–5680 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, De Marzo AM, Laughner E, Lim M, Hilton DA, Zagzag D, Buechler P, Isaacs WB, Semenza GL, Simons JW 1999 Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in common human cancers and their metastases. Cancer Res 59:5830–5835 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikoku T, Matsumoto H, Gupta RA, Das SK, Gassmann M, DuBois RN, Dey SK 2003 Expression of hypoxia-inducible factors in the peri-implantation mouse uterus is regulated in a cell-specific and ovarian steroid hormone-dependent manner. Evidence for differential function of HIFs during early pregnancy. J Biol Chem 278:7683–7691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Bartol FF, Bazer FW, Johnson GA, Joyce MM 1999 Identification and characterization of glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion molecule 1-like protein expression in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 60:241–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Gray A, Johnson GA, Taylor KM, Gertler A, Gootwine E, Ott TL, Bazer FW 1999 Effects of recombinant ovine interferon tau, placental lactogen, and growth hormone on the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 61:1409–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Heeke G, Ott TL, Strauss A, Ammaturo D, Bazer FW 1996 High yield expression and secretion of the ovine pregnancy recognition hormone interferon-tau by Pichia pastoris. J Interferon Cytokine Res 16:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Becker WC, George P, Mirando MA, Ogle TF, Bazer FW 1995 Ovine interferon-tau regulates expression of endometrial receptors for estrogen and oxytocin but not progesterone. Biol Reprod 53:732–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Stagg AG, Ott TL, Johnson GA, Ramsey WS, Bazer FW 1999 Differential effects of intrauterine and subcutaneous administration of recombinant ovine interferon tau on the endometrium of cyclic ewes. Biol Reprod 61:464–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Stewart MD, Gray CA, Choi Y, Burghardt RC, Yu-Lee LY, Bazer FW, Spencer TE 2001 Effects of the estrous cycle, pregnancy, and interferon tau on 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase expression in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 64:1392–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KM, Chen C, Gray CA, Bazer FW, Spencer TE 2001 Expression of messenger ribonucleic acids for fibroblast growth factors 7 and 10, hepatocyte growth factor, and insulin-like growth factors and their receptors in the neonatal ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 64:1236–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aprelikova O, Wood M, Tackett S, Chandramouli GV, Barrett JC 2006 Role of ETS transcription factors in the hypoxia-inducible factor-2 target gene selection. Cancer Res 66:5641–5647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang V, Davis DA, Haque M, Huang LE, Yarchoan R 2005 Differential gene up-regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha in HEK293T cells. Cancer Res 65:3299–3306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Maemura K, Imai Y, Harada T, Kawanami D, Nojiri T, Manabe I, Nagai R 2004 Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 gene promotes angiogenesis through the transactivation of both vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, Flt-1. Circ Res 95:146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll VA, Ashcroft M 2006 Role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha versus HIF-2alpha in the regulation of HIF target genes in response to hypoxia, insulin-like growth factor-I, or loss of von Hippel-Lindau function: implications for targeting the HIF pathway. Cancer Res 66:6264–6270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Paria BC, Dey SK, Das SK 1999 Differential uterine expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors correlates with uterine preparation for implantation and decidualization in the mouse. Endocrinology 140:5310–5321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathes DC, Hamon M 1993 Localization of oestradiol, progesterone and oxytocin receptors in the uterus during the oestrous cycle and early pregnancy of the ewe. J Endocrinol 138:479–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GA, Spencer TE, Burghardt RC, Taylor KM, Gray CA, Bazer FW 2000 Progesterone modulation of osteopontin gene expression in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 62:1315–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Johnson GA, Bazer FW, Burghardt RC 2004 Implantation mechanisms: insights from the sheep. Reproduction 128:657–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TE, Bazer FW 2002 Biology of progesterone action during pregnancy recognition and maintenance of pregnancy. Front Biosci 7:d1879–d1898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland JH, Manns JG, Humphrey WD 1982 Prostaglandin production by ovine embryos and endometrium in vitro. J Reprod Fertil 65:299–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critchley HO, Osei J, Henderson TA, Boswell L, Sales KJ, Jabbour HN, Hirani N 2006 Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression in human endometrium and its regulation by prostaglandin E-series prostanoid receptor 2 (EP2). Endocrinology 147:744–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Spencer TE, Bazer FW 2000 Expression of hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor c-met in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 62:1844–1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Spencer TE, Bazer FW 2000 Fibroblast growth factor-10: a stromal mediator of epithelial function in the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 63:959–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Johnson GA, Burghardt RC, Berghman LR, Joyce MM, Taylor KM, Stewart MD, Bazer FW, Spencer TE 2001 Interferon regulatory factor-two restricts expression of interferon-stimulated genes to the endometrial stroma and glandular epithelium of the ovine uterus. Biol Reprod 65:1038–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL 2001 HIF-1 and mechanisms of hypoxia sensing. Curr Opin Cell Biol 13:167–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowden Dahl KD, Robertson SE, Weaver VM, Simon MC 2005 Hypoxia-inducible factor regulates alphavbeta3 integrin cell surface expression. Mol Biol Cell 16:1901–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamforth SD, Braganca J, Eloranta JJ, Murdoch JN, Marques FI, Kranc KR, Farza H, Henderson DJ, Hurst HC, Bhattacharya S 2001 Cardiac malformations, adrenal agenesis, neural crest defects and exencephaly in mice lacking Cited2, a new Tfap2 co-activator. Nat Genet 29:469–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamforth SD, Braganca J, Farthing CR, Schneider JE, Broadbent C, Michell AC, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Norris D, Brown NA, Anderson RH, Bhattacharya S 2004 Cited2 controls left-right patterning and heart development through a Nodal-Pitx2c pathway. Nat Genet 36:1189–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withington SL, Scott AN, Saunders DN, Lopes Floro K, Preis JI, Michalicek J, Maclean K, Sparrow DB, Barbera JP, Dunwoodie SL 2006 Loss of Cited2 affects trophoblast formation and vascularization of the mouse placenta. Dev Biol 294:67–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds LP, Borowicz PP, Vonnahme KA, Johnson ML, Grazul-Bilska AT, Wallace JM, Caton JS, Redmer DA 2005 Animal models of placental angiogenesis. Placenta 26:689–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girling JE, Rogers PA 2005 Recent advances in endometrial angiogenesis research. Angiogenesis 8:89–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T 1997 The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev 18:4–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braganca J, Eloranta JJ, Bamforth SD, Ibbitt JC, Hurst HC, Bhattacharya S 2003 Physical and functional interactions among AP-2 transcription factors, p300/CREB-binding protein, and CITED2. J Biol Chem 278:16021–16029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Tan J, Matsumoto H, Robert B, Abrahamson DR, Das SK, Dey SK 2001 Adult tissue angiogenesis: evidence for negative regulation by estrogen in the uterus. Mol Endocrinol 15:1983–1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak NR, Brenner RM 2002 Vascular proliferation and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in the rhesus macaque endometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1845–1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N 2004 Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev 25:581–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds LP, Magness RR, Ford SP 1984 Uterine blood flow during early pregnancy in ewes: interaction between the conceptus and the ovary bearing the corpus luteum. J Anim Sci 58:423–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds LP, Redmer DA 1992 Growth and microvascular development of the uterus during early pregnancy in ewes. Biol Reprod 47:698–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds LP, Redmer DA 2001 Angiogenesis in the placenta. Biol Reprod 64:1033–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CY, Brace RA 1999 Developmental expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in ovine placenta and fetal membranes. J Soc Gynecol Investig 6:179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manalo DJ, Rowan A, Lavoie T, Natarajan L, Kelly BD, Ye SQ, Garcia JG, Semenza GL 2005 Transcriptional regulation of vascular endothelial cell responses to hypoxia by HIF-1. Blood 105:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.