Abstract

PTH is an important peptide hormone regulator of calcium homeostasis and osteoblast function. However, its mechanism of action in osteoblasts is poorly understood. Our previous study demonstrated that PTH activates mouse osteocalcin (Ocn) gene 2 promoter through the osteoblast-specific element 1 site, a recently identified activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) -binding element. In the present study, we examined effects of PTH on ATF4 expression and activity as well as the requirement for ATF4 in the regulation of Ocn by PTH. Results show that PTH elevated levels of ATF4 mRNA and protein in a dose- and time-dependent manner. This PTH regulation requires transcriptional activity but not de novo protein synthesis. PTH also increased binding of nuclear extracts to osteoblast-specific element 1 DNA. PTH stimulated ATF4-dependent transcriptional activity mainly through protein kinase A with a lesser requirement for protein kinase C and MAPK/ERK pathways. Lastly, PTH stimulation of Ocn expression was lost by small interfering RNA down-regulation of ATF4 in MC-4 cells and Atf4−/− bone marrow stromal cells. Collectively, these studies for the first time demonstrate that PTH increases ATF4 expression and activity and that ATF4 is required for PTH induction of Ocn expression in osteoblasts.

PTH IS A MAJOR regulator of osteoblast activity and skeletal homeostasis. PTH has both catabolic and anabolic effects on osteoblasts and bone that depend on the temporal pattern of administration; continuous administration decreases bone mass, whereas intermittent administration increases bone mass (1,2,3). At the molecular level, PTH binds to the PTH-1 receptor (PTH1R), a G protein-coupled receptor that is expressed in osteoblasts (4,5,6) and activates multiple intracellular signaling pathways that involve cAMP, inositol phosphates, intracellular Ca2+, protein kinases A and C (7), and the ERK/MAPK pathway (8,9). The ability of PTH to regulate gene expression is largely dependent on activation of specific transcription factors such as cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) (10,11), activator protein-1 family members (12,13,14,15), pituitary-specific transcription factor-1 (16), and Runt-related transcription factor-2 (Runx2) (12,17). A better understanding of the downstream PTH signaling events is essential to understand the mechanistic basis for the anabolic and catabolic actions of this hormone on bone.

The osteocalcin (Ocn) promoter has been the major paradigm for unraveling the mechanisms mediating osteoblast-specific gene expression and defining a number of transcription factors and cofactors (18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29). Because Ocn gene is regulated by PTH (30,31,32), we considered it a good model for identifying new transcriptional mediators of PTH action. Using this system, we recently showed that the osteoblast-specific element (OSE)-1 in the proximal mouse (Ocn) gene 2 (mOG2) promoter (19) is necessary and sufficient for PTH induction of this gene (33). Immediately after publication of this study, the OSE1 was identified as a binding site for activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) (34).

ATF4, also known as CREB2 (35) and tax-responsive enhancer element B67 (36), is a member of the ATF/CREB family of leucine-zipper factors that also includes CREB, cAMP response element modulator, ATF1, ATF2, ATF3, and ATF4 (37,38,39,40,41). These proteins bind to DNA via their basic region and dimerize via their leucine domain to form a large variety of homodimers and/or heterodimers that allow the cell to coordinate signals from multiple pathways (37,38,39,40,41). An in vivo role for ATF4 in bone development was established using Atf4-deficient mice (29). ATF4 is required for expression of Ocn and bone sialoprotein as demonstrated by the dramatic reduction of their mRNAs in Atf4−/− bone (29). ATF4 activates Ocn transcription through direct binding to the OSE1 site as well as interactions with Runx2 through cooperative interactions with OSE1 and OSE2 (also known as nuclear matrix protein 2 binding site) sites in the promoter (19,20,25). ATF4 activity is negatively regulated by factor inhibiting activating transcription factor-4-mediated transcription (42). Factor inhibiting activating transcription factor binds to ATF4 and represses its activity and bone formation in vivo. Although Atf4 mRNA is ubiquitously expressed, ATF4 protein preferentially accumulates in osteoblasts (34). This accumulation is explained by a selective reduction of proteasomal degradation in osteoblasts.

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of PTH on ATF4 expression and activity and evaluate whether ATF4 mediates PTH induction of Ocn expression in osteoblasts.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Tissue culture media and fetal bovine serum were obtained from HyClone (Logan, UT). γ-[32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) and α-[32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol) were purchased from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ). Other reagents were obtained from the following sources: H89, forskolin (FSK), GF109203X, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), cycloheximide (CHX), actinomycin D (ActD), and mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); U0126 from Promega (Madison, WI); and U0124 from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), PTH (1–34) from Bachem (Torrance, CA), antibodies against ATF4, Runx2, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse or goat IgG from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Cell cultures

Mouse MC3T3-E1 subclone 4 (MC-4) cells were described previously (43,44) and maintained in ascorbic acid-free α-MEM, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and were not used beyond passage 15. Rat osteoblast-like UMR106-01 cells (45) were maintained in DMEM and 10% FBS. Isolation of mouse primary bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) was described previously (33). Briefly, 6-wk-old male C57BL/6 mice were killed by cervical dislocation. Tibiae and femurs were isolated and the epiphyses were cut. Marrow was flushed with DMEM containing 20% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 10−8 m dexamethasone into a 60-mm dish, and the cell suspension was aspirated up and down with a 20-gauge needle to break clumps of marrow. The cell suspension (marrow from two mice/flask) was then cultured in a T75 flask in the same medium. After 10 d, cells reach confluency and are ready for experiments.

DNA constructs and transfection

Wild-type and mutant p4OSE1-luc plasmids were described previously (25,33). Cells were plated on 35-mm dishes at a density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2. After 24 h, cells were transfected with lipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each transfection contained 0.5 μg of the indicated plasmid plus 0.05 μg of pRL-SV40, containing a cDNA for Renilla reformis luciferase to control for transfection efficiency. Cells were harvested and assayed using the dual luciferase assay kit (Promega) on a Monolight 2010 luminometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).

Preparation of nuclear extracts and gel mobility shift assay (GMSA)

Nuclear extracts were prepared and GMSAs were conducted as previously described (43). Each reaction contained 1 μg of nuclear extracts. The DNA sequences of OSE1 oligonucleotides used for GMSA were as follows: wild-type (wt): TGC TTA CAT CAG AGA GCA); mutant (mt): TGC TTA gta CAG AGA GCA.

Western blot analysis

Twenty micrograms of nuclear extracts were fractionated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH). The membrane was blocked in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 buffer; probed with antibodies against ATF4 (1:1000) followed by incubation with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5000); and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Finally, blots were stripped two times in buffer containing 65 mm Tris Cl (pH 6.8), 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.7% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol at 65 C for 15 min and reprobed with β-actin antibody (1:5000) for normalization.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed using 2 μg of denatured RNA and 100 pmol of random hexamers (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA) in a total volume of 25 μl containing 12.5 U MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on an iCycler (Bio-Rad, Minneapolis, MN) using a SYBR Green PCR core kit (Applied Biosystems) and cDNA equivalent to 10 ng RNA in a 50-μl reaction according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA sequences of mouse primers used for real-time PCR were: Atf4, 5′-GAG CTT CCT GAA CAG CGA AGT G-3′ (forward), 5′-TGG CCA CCT CCA GAT AGT CAT C-3′ (reverse); Ocn, 5′-TAG TGA ACA GAC TCC GGC GCT A-3′ (forward), 5′-TGT AGG CGG TCT TCA AGC CAT-3′ (reverse); Pth1r, 5′-GAT GCG GAC GAT GTC TTT ACC-3′ (forward), 5′-GGC GGT CAA ATA CCT CC-3′ (reverse); Col1(I), 5′-AGA TTG AGA ACA TCC GCA GCC-3′ (forward), 5′-TCC AGT ACT CTC CGC TCT TCC A-3′ (reverse); Opn, 5′-CCA ATG AAA GCC ATG ACC ACA-3′, (forward), 5′-CGT CAG ATT CAT CCG AGT CCA C-3′ (reverse); Gapdh, 5′-CAG TGC CAG CCT CGT CCC GTA GA-3′ (forward), 5′-CTG CAA ATG GCA GCC CTG GTG AC-3′ (reverse). For all primers the amplification was performed as follows: initial denaturation at 95 C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 C for 15 sec and 60 C for 60 sec. Melting curve analysis was used to confirm the specificity of the PCR products. Six samples were run for each primer set. The levels of mRNA were calculated by the ΔCT (the difference between the threshold cycles) method (46). Atf4, Ocn, Col1(I), Pth1r, and Opn mRNAs were normalized to Gapdh mRNA.

Northern blot

Twenty micrograms of total RNA was fractionated on 1.0% agarose-formaldehyde gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose paper. The mouse Atf4 cDNA inserts were excised from plasmid DNA with the appropriate restriction enzymes and purified by agarose gel electrophoresis before labeling with α-[32P]dCTP using a random primer kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Hybridizations were performed as previously described using a Bellco Autoblot hybridization oven (47). Same blots were reprobed with [32P]-labeled cDNA to 18S rRNA for loading (48).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-MC-4 cells, which contain high levels of Atf4 mRNA, were seeded at a density of 25,000 cells/cm2. After 24 h, cells were transfected with mouse Atf4 siRNA (sense: 5′-GAG CAU UCC UUU AGU UUA GUU-3′; antisense: 5′-CUA AAC UAA AGG AAU GCU CUU-3′) (49) or negative control siRNA (low GC, catalog no. 12935–200; Invitrogen) using LipofectAMINE 2000 (Invitrogen). After 48 h, cells from three identically treated dishes were pooled and harvested for total RNA, followed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses for Atf4, Ocn, and Col1(I) mRNAs. A second set of mouse Atf4 siRNAs was purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX; catalog no. AM16704, ID 160775 and 160776) and used to confirm the results using the first set of Atf4 siRNA.

Atf4-deficient mice

Breeding pairs of mice heterozygous for ATF4 (Swiss Black mouse background) were obtained from Dr. Randal J. Kaufman (the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the University of Michigan School of Medicine). These mice were originally developed by Dr. Tim M. Townes (University of Alabama at Birmingham) and were used to generate Atf4 wild-type (Atf4+/+), heterozygous (Atf4+/−), and homozygous mutant (Atf4−/−) embryos/pups for this study. Original reports describing the phenotype of Atf4 homozygote-null mutants used the identical strain of mice (50). PCR genotyping was performed on tail DNA using a cocktail of three primers (TOWNES-1: 5′-AGC AAA ACA AGA CAG CAG CCA CTA-3′; TOWNES-2: 5′-GTT TCT ACA GCT TCC TCC ACT CTT-3′, and TOWNES-3: 5′-ATA TTG CTG AAG AGC TTG GCGGC-3′) obtained from the laboratories of Dr. Randal J. Kaufman. A 700-bp DNA PCR product was amplified from Atf4−/− mouse tail DNA and a 900-bp product from wild-type mice (see Fig. 7A). The genotype of each mouse established by PCR of tail genomic DNA was confirmed by Western blotting of calvaria cell lysates and anti-ATF4 antibody. A breeding colony was established using heterozygote mice to provide littermate controls. All animal studies were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Healthcare System.

Figure 7.

PTH stimulation of Ocn expression is lost in Atf4−/− BMSCs. A, PCR genotyping was performed on tail DNA using a cocktail of three primers (see Materials and Methods). A 700-bp DNA PCR product is amplified from Atf4−/− mouse tail DNA and a 900-bp product from wild-type mice. B–E, Effects of ATF4 deficiency on PTH stimulation of Atf4 (B), Ocn (C), Opn (D), and Pth1r (E) expression in BMSCs. Primary BMSCs were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2 in 35-mm dishes and cultured in 10% FBS medium overnight. Cells were then treated with 10−7 m PTH for 6 h followed by RNA preparation and quantitative real-time RT/PCR for Atf4 (B), Ocn (C), Opn (D), and Pth1r (E) mRNA, which were normalized to the Gapdh mRNAs. *, P < 0.05 (ctrl vs. PTH); #, P < 0.05 (wt vs. mt). Data represent mean ± sd. Experiments were repeated three times, and qualitatively identical results were obtained.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). A one-way ANOVA analysis was used followed by the Dunnett’s test (see Fig. 3, B and C). Student’s’ t test was used to test for differences between two groups of data. Differences with a P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Results were expressed as means ± sd.

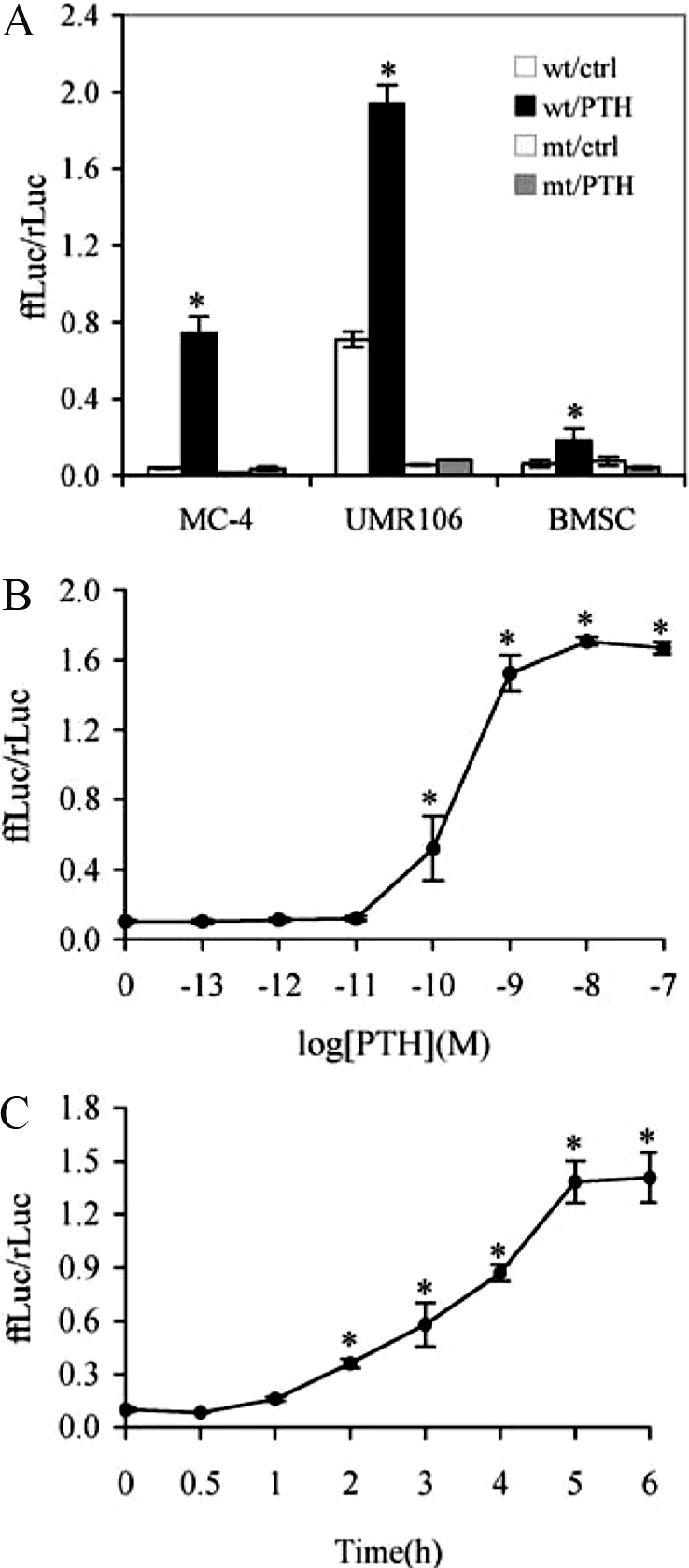

Figure 3.

PTH increases ATF4-dependent transcriptional activity in MC-4 cells. A, Target cell specificity. Cells (MC-4, UMR106–01, and primary BMSCs) were transiently transfected with p4OSE1-luc and renilla luciferase normalization plasmid and treated with 10−7 m PTH for 6 h before being harvested and assayed for dual-luciferase activity. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to renilla luciferase activity (for transfection efficiency). B, Dose dependence. MC-4 cells were transiently transfected as in Fig. 2A and treated with indicated concentration of PTH (from 10−11 to 10−7 m) for 6 h followed by dual-luciferase assay. C, Time course. MC-4 cells were transiently transfected as in Fig. 2A and treated with 10−7 m PTH for indicated times. Data represent mean ± sd. Experiments were repeated three to four times and qualitatively identical results were obtained. *, P < 0.05 [control (ctrl) vs. PTH].

Results

PTH increases ATF4 expression in MC-4 cells

To determine the effect of PTH on Atf4 mRNA expression, MC-4 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PTH (from 10−13 to 10−7 m) for 6 h, and total RNA was isolated for Northern blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 1A, PTH dose-dependently increased levels of Atf4 mRNAs with a significant stimulatory effect first detected at a concentration of 10−10 m. Western blot analyses using nuclear extracts from MC-4 cells with and without PTH treatment show that PTH also dose-dependently elevated the levels of ATF4 protein with maximal stimulation at 10−10 m. Measurable stimulation of ATF4 protein was observed 1 h after PTH addition with maximal induction occurring at 3 h and lasting for at least 5 h (Fig. 1, B and C). PTH similarly increased Atf4 and Ocn mRNA expression in mouse primary bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) (see Fig. 7, B and C). To assess the molecular mechanisms of PTH stimulation of Atf4 mRNA expression, MC-4 cells were treated with and without inhibitors of transcription and translation in the presence and absence of PTH (10−7 m) for 6 h. As shown in Fig. 2A, the protein synthesis inhibitor CHX alone induced Atf4 mRNA by 4-fold, which is typically observed in immediate early response genes such as Fra-2 (15). The PTH-stimulation of Atf4 mRNA was not blocked by CHX treatment, suggesting that de novo protein synthesis is not necessary for the PTH regulation. In contrast, the transcription inhibitor ActD completely abolished the PTH-stimulated Atf4 mRNA induction (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the PTH effect requires transcription.

Figure 1.

PTH increases levels of ATF4 expression in osteoblasts. A, Effect of PTH on Atf4 mRNA. MC-4 cells were seeded at a density of 50,000 cells/cm2 in 35-mm dishes and cultured in 10% FBS medium overnight. Cells were then treated with various concentration of PTH for 6 h. For each group, total RNA (20 μg/lane) was loaded for Northern hybridization using cDNA probes for mouse Atf4 mRNA and 18S rRNAs (for normalization). B, Effect of PTH on ATF4 proteins (dose response). MC-4 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of PTH for 6 h and nuclear extracts were prepared for Western blot analysis for ATF4. C, Effect of PTH on ATF4 proteins (time course). MC-4 cells were treated with 10−7 m PTH for indicated time (h). Experiments were repeated three to four times, and qualitatively identical results were obtained.

Figure 2.

Effects of CHX/ActD treatment on PTH induction of Atf4 mRNA. MC-4 cells were treated with vehicle or 10 μg/ml CHX (A) or ActD (B) in the absence or presence of PTH for 6 h. Atf4 and Gapdh mRNAs were determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis. Experiments were repeated three times, and qualitatively identical results were obtained. *, P < 0.05 [control (ctrl) vs. PTH]; #, P < 0.05 (CHX vs. CHX/PTH); †, < 0.05 (control vs. CHX).

PTH increases ATF4-dependent transcriptional activity in osteoblasts

The effect of PTH on ATF4-dependent transcriptional activity was evaluated in two osteoblast cell lines and primary mouse bone marrow stromal cells. Cells were transiently transfected with wt or mt p4OSE1-luc, an artificial promoter containing four copies of wt or mt OSE1 (a specific ATF4-binding element) fused to a −34 to +13 minimal mOG2 promoter, and pRL-SV40, a renilla luciferase normalization plasmid. After 42 h, cells were treated with PTH (10−7 m) for 6 h followed by dual-luciferase assay. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to renilla luciferase activity as a control for transfection efficiency. As shown in Fig. 3A, PTH stimulated ATF4-dependent OSE1 activity by 17-, 2.7-, and 2.8-fold in MC-4, UMR106-01, and primary BMSCs (P < 0.05, control vs. PTH), respectively. This PTH response was completely lost with the introduction of a 3-bp point mutation in the OSE1 core sequence (from TTACATCA to TTAGTACA). (Note that there are no additional OSE1 sites in the upstream region of the mOG2 promoter.) Figure 3B shows that PTH stimulated ATF4-dependent transcriptional activity in a dose-dependent manner with a significant stimulatory effect first detected at a concentration of 10−10 m. This is consistent with our previous study that examined effects of PTH on endogenous Ocn mRNA (33). Time-course studies revealed that the earliest effect of PTH stimulation was seen within 1 h and peaked at 5–6 h (Fig. 3C).

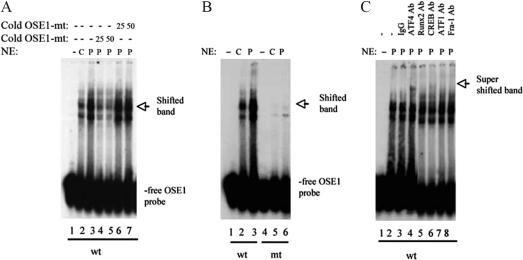

PTH increases ATF4 binding to OSE1 DNA

To determine whether PTH increases ATF4 binding to OSE1 DNA, we performed GMSA using nuclear extracts from MC-4 cells with and without 10−7 m PTH for 6 h. Consistent with our previous observation (33), nuclear extracts from PTH-treated MC-4 cells exhibited increased binding to intact OSE1 oligonucleotides (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 3), and this binding was significantly reduced by the addition of 25- and 50-fold molar excesses of unlabeled wt OSE1 oligonucleotides (Fig. 4A, lanes 4 and 5) but not by unlabeled mt OSE1 oligonucleotides (Fig. 4A, lane 6 and 7). In contrast, GMSA using labeled mt OSE1 oligonucleotides as probes showed that both basal and PTH-induced binding activity was abolished by the same 3-bp point mutation (Fig. 4B, lanes 4–6). The same mutation also abolished PTH activation of 647- and 116-bp mOG2 promoter fragments and 4OSE1 (33) (Fig. 3A). Importantly, PTH-increased binding to OSE1 was supershifted with an anti-ATF4 antibody (Fig. 4C, lanes 4). In contrast, normal IgG or antibodies against Runx2, CREB, ATF1, and Fra-1 did not significantly supershift the PTH-stimulated band (Fig 4C, lanes 3–8). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that ATF4 is a component of the PTH-stimulated DNA-protein complex associating with OSE1. [Note that PTH treatment did not alter binding of Runx2 to OSE2 DNA in the mOG2 promoter in GMSA (33).]

Figure 4.

PTH increases binding of ATF4 to OSE1 DNA. A, PTH increases binding of osteoblast nuclear extracts (NE) to OSE1. Nuclear extracts were prepared from MC-4 cells with (P) (lanes 3–7) or without (C) (lane 2) PTH treatment for 6 h. One microgram of each nuclear extract was incubated with end-labeled double-stranded OSE1 (TGC TTA CAT CAG AGA GCA) and analyzed by electrophoresis on 4% polyacrylamide gels. DNA binding to labeled wild-type OSE1 probe was analyzed in the presence of 25- to 50-fold molar excesses of cold wt (lanes 6 and 7) or mt (lanes 4 and 5) OSE1 (TGC TTA gta CAG AGA GCA) by GMSA using 1 μg of nuclear extracts from PTH-treated MC-4 cells. B, Binding site specificity. Labeled wt (lanes 1–3) and mt (lanes 4–6) OSE1 probes were incubated with 1 μg nuclear extracts from MC-4 cells with and without PTH treatment. C, The nuclear complex binding OSE1 contains ATF4. Labeled wild-type OSE1 probe was incubated with 1 μg nuclear extracts from PTH-treated MC-4 cells in the presence of normal control IgG (lane 3), ATF4 antibody (lane 4), Runx2 antibody (lane 5), CREB antibody (lane 6), ATF1 antibody (lane 7), and Fra-1 antibody (lane 8). Experiments were repeated three to four times, and qualitatively identical results were obtained.

Protein kinase A (PKA) is the major signaling pathway mediating the PTH response

To identify signaling pathways mediating PTH activation of ATF4 transcriptional activity, we examined the effects of various inhibitors or activators. As shown in Fig. 5A, H89, a selective inhibitor of the PKA pathway, completely abolished PTH-stimulated ATF4 transcriptional activity (P > 0.05, control vs. PTH). GF109203X, a specific inhibitor of the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway, significantly decreased the PTH stimulation. U0126, a specific inhibitor of MAPK, partially suppressed PTH stimulation. As shown in Fig. 5B, FSK, a well-known activator of PKA, increased ATF4 activity in the absence of PTH in a dose-dependent manner. In combination with PTH, the effect of FSK was not additive, indicating that the PKA pathway was maximally stimulated. PMA, a PKC activator, did not significantly affect the PTH-induced ATF4 activity at a concentration range of 0.1–5 μm. A higher concentration of PMA (20 μm) slightly increased PTH-stimulated ATF4 activity without changing the basal activity (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results indicate that PKA is the major pathway mediating PTH activation of ATF4 in osteoblasts with PKC and MAPK/ERK pathways playing lesser roles in the PTH response. The concentrations of the inhibitors or activators used in this study are in the range reported to selectively affect the relevant pathways (33,51,52,53). We found no evidence of toxicity; compounds did not reduce cell DNA or protein under the current condition (data not shown).

Figure 5.

PKA is the major signaling pathway mediating the PTH response. A, Effects of inhibitors/activators on PTH-induced ATF4 transcriptional activity. MC-4 cells were transiently transfected with p4OSE1-luc and renilla luciferase normalization plasmid. After 42 h, cells were treated with 10 μm inhibitors/activators in the absence or presence of 10−7 m PTH for 6 h followed by dual-luciferase assay. Compounds used were: H89, a PKA inhibitor; FSK, a PKA activator; GF109203X, a PKC inhibitor; PMA, a PKC activator; U0126, a MAPK inhibitor; and U0124, an inactive analog of U0126. B and C, Dose-response of FSK (B) and PMA (C) on PTH stimulation of ATF4 transcriptional activity. MC-4 cells were transiently transfected as in Fig. 5A and treated with indicated concentration of respective activator for 6 h in the absence and presence of 10−7 m PTH followed by dual-luciferase assay. Data represent mean ± sd. Experiments were repeated three times and qualitatively identical results were obtained. *, P < 0.05 [control (ctrl) vs. PTH].

PTH-dependent induction of Ocn gene expression requires ATF4

We used two separate approaches to establish the requirements for ATF4 in the regulation of Ocn gene expression by PTH. First, we examined whether ATF4 is necessary for PTH induction of Ocn mRNA expression in osteoblasts by knocking down endogenous Atf4 transcripts using siRNA. MC-4 cells, which express high levels of Atf4 mRNA, were transiently transfected with ATF4 siRNA or negative control siRNA (Invitrogen) using LipofectAMINE 2000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This siRNA specifically targets mouse Atf4 (49). As shown in Fig. 6A, quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis showed that ATF4 siRNA (20 and 40 nm) efficiently reduced the levels of Atf4 mRNA by 57 and 71%, respectively. In contrast, the negative control siRNA did not reduce the Atf4 mRNA (Fig. 6B). As shown in Fig. 6C, the basal level of Ocn mRNA was reduced greater than 70% by ATF4 siRNA (P < 0.05, control vs. ATF4 siRNA). Importantly, PTH-stimulated Ocn mRNA was completely abolished in ATF4 siRNA group relative to the control siRNA group. Conversely, Col1(I) mRNA was not altered by ATF4 siRNA or PTH (Fig. 6D). Similar results were obtained when a different set of ATF4 siRNAs was used in MC-4 cells (data not shown).

Figure 6.

ATF4 siRNA blocks PTH stimulation of Ocn expression. A and B, MC-4 cells were transiently transfected with Atf4 siRNA (A) or negative control (Ctrl) siRNA (B). After 48 h, total RNA was prepared for quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses for Atf4 mRNA, which was normalized to Gapdh mRNA. C and D, MC-4 cells were transiently transfected with 40 nm Atf4 siRNA or negative control siRNAs. After 42 h, cells were treated with and without 10−7 m PTH for 6 h followed by RNA preparation and quantitative real-time RT-PCR analyses for Ocn and Col1(I) mRNAs, which were normalized to the Gapdh mRNAs. *, P < 0.05 (ctrl vs. PTH); #, P < 0.05 (ctrl siRNA vs. ATF4 siRNA). Data represent mean ± sd. Experiments were repeated three times, and qualitatively identical results were obtained.

To further establish the requirement for ATF4 in the PTH response, primary BMSCs were isolated from wt and Atf4−/− mice (Fig. 7A) and treated with or without PTH (10−7 m) for 6 h followed by RNA preparation and quantitative real-time PCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 7B, minimal Atf4 mRNA was detected by real-time RT/PCR in the Atf4−/− BMSCs. Consistent with the results of experiments with MC-4 cells, PTH significantly stimulated Atf4 mRNA in wt BMSCs (P < 0.05, control vs. PTH), but this induction was completely lost in cells from Atf4−/− mice (Fig. 7B). As shown in Fig. 7C, PTH significantly increased Ocn mRNA in wt BMSCs, which was abolished in Atf4−/− BMSCs (P > 0.05, control vs. PTH). The basal level of Ocn mRNA was also significantly reduced in Atf4−/− BMSCs relative to wt cells (P < 0.05, wt vs. mt). In contrast, PTH did not increase Opn mRNA in wt or mt BMSCs (P > 0.05, control vs. PTH) (Fig. 7D). However, the level of Opn mRNA was increased in Atf4−/− cells (P < 0.05, wt vs. mt), indicating that ATF4 may function as a negative regulator of Opn expression (Fig. 7D). In addition, the levels of Pth1r mRNA were not significantly changed by either ATF4 deficiency or PTH, suggesting that PTH signaling is intact in the absence of ATF4 (Fig. 7E). Taken together, these data clearly establish that ATF4 is required for PTH induction of Ocn mRNA in primary BMSCs.

Discussion

This study examined actions of PTH on ATF4 expression and activity in osteoblasts. Using the Ocn gene as a model system for studying PTH-dependent transcription, we found the following: 1) PTH rapidly induces Atf4 expression in MC-4 cells and mouse primary bone marrow stromal cells in a time- and dose-dependent manners; 2) PTH increases in vitro binding of ATF4 to OSE1 DNA; 3) PTH dramatically activates ATF4 transcriptional activity mainly through the PKA pathway; 4) PTH stimulation of Ocn gene expression requires ATF4 because it is abolished by ATF4 siRNA in MC-4 cells and is not seen in ATF4-deficeint BMSCs. Collectively, this study establishes that ATF4 is a novel downstream target of PTH actions in osteoblasts.

It is well documented that PTH signals mainly through the PKA pathway. In the present study, we show that PKA inhibition completely blocked PTH stimulation of ATF4 activity. Furthermore, activation of the PKA pathway by FSK dramatically increased ATF4 activity in the absence of PTH. However, when combined with PTH, the effect of FSK was not additive. These results strongly suggest that PKA is the major pathway for PTH to activate ATF4 because each agent (i.e. FSK or PTH) maximally stimulates the same pathway, making additional ATF4 activation impossible. Inhibition of the PKC pathway also resulted in a significant reduction in PTH-induced ATF4 activity (data not shown), but PKC activation by PMA failed to activate both basal or PTH-induced ATF4 activity. Thus, PKC is partially required for PTH activation of ATF4. Lastly, inhibition of the MAPK/ERK pathway led to partial inhibition of the PTH stimulation. These three pathways are also required for PTH induction of both Ocn mRNA and 1.3-kb mOG2 promoter activity as previously described (33), further supporting our hypothesis that ATF4 mediates PTH induction of Ocn gene expression.

A recent study showed that ATF4 mediates β-adrenergic induction of Rankl mRNA expression via direct binding to the upstream OSE1 site in the Rankl promoter in osteoblasts (54). However, PTH stimulation of Rankl expression was not reduced in the absence of ATF4, suggesting that this catabolic action of PTH is independent of this transcription factor. Phosphorylation seems to be critical for ATF4 to elicit its function in osteoblasts and bone. A PKA phosphorylation site (serine 254) within the ATF4 molecule was recently shown to mediate β-adrenergic induction of Rankl mRNA expression in osteoblasts (54). In addition, ATF4 is phosphorylated at serine 251 by ribosomal kinase 2 (RSK2), the kinase inactivated in Coffin-Lowry syndrome, an X-linked mental retardation disorder associated with skeletal manifestations (29). Because RSK2 is an immediate downstream target of MAPK/ERK that is activated by PTH signaling (8,9), PTH may in part activate ATF4 via the MAPK/ERK/RSK2 pathway. It remains to be determined whether the PKA and/or RSK2 phosphorylation sites are involved in the PTH activation of ATF4.

One of the major downstream factors for PTH signaling is CREB, the cAMP response element binding protein. Actions of CREB are mediated through cAMP response elements (CREs) in the regulatory regions of target genes. PTH phosphorylates CREB at serine 133. This phosphorylation event stimulates the binding of CREB to the CRE and is required for CREB to activate transcription of target genes. Through this classical pathway, PTH rapidly induces transcription of immediate-early response genes including those encoding activator protein-1 family members such as c-Fos, c-Jun, Fra-1, Fra-2, and FosB (10,14,15,52,55,56,57). Although CREB was shown to binding to the OSE1 site (29), overexpression of CREB was unable to activate OSE1-dependent transcription activity of the mOG2 promoter in vitro (29), suggesting that this site is not a major functional site for CREB. Furthermore, the OSE1 binding activity stimulated by PTH was not supershifted by an anti-CREB antibody. Instead, this complex clearly contains ATF4 protein (Fig. 4C). Thus, we were unable to obtain any evidence for the involvement of CREB in the PTH response. However, our results do not exclude the possibility that PTH/CREB activates Atf4 mRNA transcription via CREB binding to potential CRE sites in the Atf4 promoter.

PTH induction of immediate-early response genes occurs very rapidly (minutes to hours) and lasts for several hours. This PTH response is usually independent upon the presence of de novo protein synthesis but requires active cellular transcription. The time-course experiments in the present study indicate that PTH induction of Atf4 occurs within 1 h of PTH addition and peaks after 3–6 h. Furthermore, this regulation depends on active cellular transcription and does not require de novo protein synthesis. Therefore, ATF4 may be considered as an additional PTH early response gene.

ATF4-deficeint mice as well as humans with mutations in RSK2, an ATF4 activating kinase, exhibit striking deficits in bone formation and osteoblast activity. Because ATF4 is required for osteoblast function and bone formation in vivo, and as shown herein, ATF4 is a novel downstream target of PTH in osteoblasts, it will be important to determine whether ATF4 is also required for the anabolic actions of PTH in bone.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Randal J. Kaufman (Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the University of Michigan School of Medicine) for providing us with the Atf4-deficient mice.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK072230 (to G.X.) and DE11723 and DE12211 (to R.T.F.) and Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-07-1-0160 (to G.X.)

Disclosure Statement: The authors of this manuscript have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online January 10, 2008

Abbreviations: ActD, Actinomycin D; ATF4, activating transcription factor 4; BMSC, bone marrow stromal cell; CHX, cycloheximide; CRE, cAMP response element; CREB, CRE binding protein; FBS, fetal bovine serum; FSK, forskolin; GMSA, gel mobility shift assay; MC-4, MC3T3-E1 subclone 4; mOG2, mouse Ocn gene 2; mt, mutant; OCN, osteocalcin; OSE1, osteoblast-specific element-1; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; PTH1R, PTH-1 receptor; RSK2, ribosomal kinase 2; Runx2, Runt-related transcription factor-2; siRNA, small interfering RNA; wt, wild type.

References

- Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, Prince R, Gaich GA, Reginster JY, Hodsman AB, Eriksen EF, Ish-Shalom S, Genant HK, Wang O, Mitlak BH 2001 Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 344:1434–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao D, He B, Karaplis AC, Goltzman D 2002 Parathyroid hormone is essential for normal fetal bone formation. J Clin Invest 109:1173–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiralp B, Chen HL, Koh AJ, Keller ET, McCauley LK 2002 Anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone during bone growth are dependent on c-fos. Endocrinology 143:4038–4047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge NC, Alcorn D, Michelangeli VP, Kemp BE, Ryan GB, Martin TJ 1981 Functional properties of hormonally responsive cultured normal and malignant rat osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology 108:213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley LK, Koh AJ, Beecher CA, Cui Y, Decker JD, Franceschi RT 1995 Effects of differentiation and transforming growth factor β1 on PTH/PTHrP receptor mRNA levels in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 10:1243–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley LK, Koh AJ, Beecher CA, Cui Y, Rosol TJ, Franceschi RT 1996 PTH/PTHrP receptor is temporally regulated during osteoblast differentiation and is associated with collagen synthesis. J Cell Biochem 61:638–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarthout JT, D’Alonzo RC, Selvamurugan N, Partridge NC 2002 Parathyroid hormone-dependent signaling pathways regulating genes in bone cells. Gene 282:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpio L, Gladu J, Goltzman D, Rabbani SA 2001 Induction of osteoblast differentiation indexes by PTHrP in MG-63 cells involves multiple signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281:E489–E499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarthout JT, Doggett TA, Lemker JL, Partridge NC 2001 Stimulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases and proliferation in rat osteoblastic cells by parathyroid hormone is protein kinase C-dependent. J Biol Chem 276:7586–7592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearman AT, Chou WY, Bergman KD, Pulumati MR, Partridge NC 1996 Parathyroid hormone induces c-fos promoter activity in osteoblastic cells through phosphorylated cAMP response element (CRE)-binding protein binding to the major CRE. J Biol Chem 271:25715–25721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez GA, Montminy MR 1989 Cyclic AMP stimulates somatostatin gene transcription by phosphorylation of CREB at serine 133. Cell 59:675–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvamurugan N, Chou WY, Pearman AT, Pulumati MR, Partridge NC 1998 Parathyroid hormone regulates the rat collagenase-3 promoter in osteoblastic cells through the cooperative interaction of the activator protein-1 site and the runt domain binding sequence. J Biol Chem 273:10647–10657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alonzo RC, Kowalski AJ, Denhardt DT, Nickols GA, Partridge NC 2002 Regulation of collagenase-3 and osteocalcin gene expression by collagen and osteopontin in differentiating MC3T3-E1 cells. J Biol Chem 277:24788–24798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley LK, Koh AJ, Beecher CA, Rosol TJ 1997 Proto-oncogene c-fos is transcriptionally regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH) and PTH-related protein in a cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent manner in osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology 138:5427–5433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley LK, Koh-Paige AJ, Chen H, Chen C, Ontiveros C, Irwin R, McCabe LR 2001 Parathyroid hormone stimulates fra-2 expression in osteoblastic cells in vitro and in vivo. Endocrinology 142:1975–1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata Y, Nakao S, Kim RH, Li JJ, Furuyama S, Sugiya H, Sodek J 2000 Parathyroid hormone regulation of bone sialoprotein (BSP) gene transcription is mediated through a pituitary-specific transcription factor-1 (Pit-1) motif in the rat BSP gene promoter. Matrix Biol 19:395–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan V, Moore TL, Ma YL, Helvering LM, Frolik CA, Valasek KM, Ducy P, Geiser AG 2003 Parathyroid hormone bone anabolic action requires cbfa1/runx2-dependent signaling. Mol Endocrinol 17:423–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Zhang R, Geoffroy V, Ridall AL, Karsenty G 1997 Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell 89:747–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Karsenty G 1995 Two distinct osteoblast-specific cis-acting elements control expression of a mouse osteocalcin gene. Mol Cell Biol 15:1858–1869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriman HL, van Wijnen AJ, Hiebert S, Bidwell JP, Fey E, Lian J, Stein J, Stein GS 1995 The tissue-specific nuclear matrix protein, NMP-2, is a member of the AML/CBF/PEBP2/runt domain transcription factor family: interactions with the osteocalcin gene promoter. Biochemistry 34:13125–13132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GS, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL 1997 The osteocalcin gene: a model for multiple parameters of skeletal-specific transcriptional control. Mol Biol Rep 24:185–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee C, McCabe LR, Choi JY, Hiebert SW, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB 1997 Runt homology domain proteins in osteoblast differentiation: AML3/CBFA1 is a major component of a bone-specific complex. J Cell Biochem 66:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee C, Hiebert SW, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS 1996 An AML-1 consensus sequence binds an osteoblast-specific complex and transcriptionally activates the osteocalcin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:4968–4973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian JB, Stein GS 2003 Runx2/Cbfa1: a multifunctional regulator of bone formation. Curr Pharm Des 9:2677–2685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Jiang D, Ge C, Zhao Z, Lai Y, Boules H, Phimphilai M, Yang X, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT 2005 Cooperative Interactions between activating transcription factor 4 and Runx2/Cbfa1 stimulate osteoblast-specific osteocalcin gene expression. J Biol Chem 280:30689–30696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GS, Lian JB, Stein JL, van Wijnen AJ, Frankel B, Montecino M 1996 Mechanisms regulating osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. In: Bilezikian JP, Raise LG, Rodon GA, eds. Principles of bone biology. San Diego: Academic Press; 69–86 [Google Scholar]

- Lian JB, Stein GS, Stein JL, Van Wijnen A, McCabe L, Banerjee C, Hoffmann H 1996 The osteocalcin gene promoter provides a molecular blueprint for regulatory mechanisms controlling bone tissue formation: role of transcription factors involved in development. Connect Tissue Res 35:15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P, Karsenty, G 1999 Transcriptional control of osteoblast differentiation. Endocrinologist 9:32–35 [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Matsuda K, Bialek P, Jacquot S, Masuoka HC, Schinke T, Li L, Brancorsini S, Sassone-Corsi P, Townes TM, Hanauer A, Karsenty G 2004 ATF4 Is a substrate of RSK2 and an essential regulator of osteoblast biology: implication for Coffin-Lowry syndrome. Cell 117:387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguslawski G, Hale LV, Yu XP, Miles RR, Onyia JE, Santerre RF, Chandrasekhar S 2000 Activation of osteocalcin transcription involves interaction of protein kinase A- and protein kinase C-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem 275:999–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu XP, Chandrasekhar S 1997 Parathyroid hormone (PTH 1–34) regulation of rat osteocalcin gene transcription. Endocrinology 138:3085–3092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux JM, Towler DA 1996 Synergistic induction of osteocalcin gene expression: identification of a bipartite element conferring fibroblast growth factor 2 and cyclic AMP responsiveness in the rat osteocalcin promoter. J Biol Chem 271:7508–7515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Franceschi RT, Boules H, Xiao G 2004 Parathyroid hormone induction of the osteocalcin gene: requirement for an osteoblast-specific element 1 sequence in the promoter and involvement of multiple signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 279:5329–5337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Karsenty G 2004 ATF4, the osteoblast accumulation of which is determined post-translationally, can induce osteoblast-specific gene expression in non-osteoblastic cells. J Biol Chem 279:47109–47114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski BA, Morle GD, Huggenvik J, Uhler MD, Leiden JM 1992 Molecular cloning of human CREB-2: an ATF/CREB transcription factor that can negatively regulate transcription from the cAMP response element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:4820–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto A, Nyunoya H, Morita T, Sato T, Shimotohno K 1991 Isolation of cDNAs for DNA-binding proteins which specifically bind to a tax-responsive enhancer element in the long terminal repeat of human T-cell leukemia virus type I. J Virol 65:1420–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindle PK, Montminy MR 1992 The CREB family of transcription activators. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2:199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hai T, Wolfgang CD, Marsee DK, Allen AE, Sivaprasad U 1999 ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr 7:321–335 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TE, Habener JF 1993 Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate response element binding protein (CREB) and related transcription-activating deoxyribonucleic acid-binding proteins. Endocr Rev 14:269–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassone-Corsi P 1994 Goals for signal transduction pathways: linking up with transcriptional regulation. EMBO J 13:4717–4728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziff EB 1990 Transcription factors: a new family gathers at the cAMP response site. Trends Genet 6:69–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu VW, Ambartsoumian G, Verlinden L, Moir JM, Prud’homme J, Gauthier C, Roughley PJ, St. Arnaud R 2005 FIAT represses ATF4-mediated transcription to regulate bone mass in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol 169:591–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Cui Y, Ducy P, Karsenty G, Franceschi RT 1997 Ascorbic acid-dependent activation of the osteocalcin promoter in MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts: requirement for collagen matrix synthesis and the presence of an intact OSE2 sequence. Mol Endocrinol 11:1103–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Christensen K, Chawla K, Xiao G, Krebsbach PH, Franceschi RT 1999 Isolation and characterization of MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast subclones with distinct in vitro and in vivo differentiation/mineralization potential. J Bone Miner Res 14:893–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MD, Bargeon JL, Xiao G, Thomas PE, Kim A, Cui Y, Franceschi RT 2000 Identification of a homeodomain binding element in the bone sialoprotein gene promoter that is required for its osteoblast-selective expression. J Biol Chem 275:13907–13917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xi L, Hunt JL, Gooding W, Whiteside TL, Chen Z, Godfrey TE, Ferris RL 2004 Expression pattern of chemokine receptor 6 (CCR6) and CCR7 in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck identifies a novel metastatic phenotype. Cancer Res 64:1861–1866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi RT, Iyer BS, Cui Y 1994 Effects of ascorbic acid on collagen matrix formation and osteoblast differentiation in murine MC3T3-E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 9:843–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkawitz R, Gerbi SA, Glatzer KH 1979 Ribosomal DNA of fly Sciara coprophila has a very small and homogeneous repeat unit. Mol Gen Genet 173:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams CM 2007 Role of the transcription factor ATF4 in the anabolic actions of insulin and the anti-anabolic actions of glucocorticoids. J Biol Chem 282:16744–16753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuoka HC, Townes TM 2002 Targeted disruption of the activating transcription factor 4 gene results in severe fetal anemia in mice. Blood 99:736–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G, Gopalakrishnan R, Jiang D, Reith E, Benson MD, Franceschi RT 2002 Bone morphogenetic proteins, extracellular matrix, and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways are required for osteoblast-specific gene expression and differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Bone Miner Res 17:101–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvamurugan N, Pulumati MR, Tyson DR, Partridge NC 2000 Parathyroid hormone regulation of the rat collagenase-3 promoter by protein kinase A-dependent transactivation of core binding factor α1. J Biol Chem 275:5037–5042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang H, Franceschi R, McCauley L, Wang D, Somerman M 2000 Parathyroid hormone-related protein downregulates bone sialoprotein gene expression in cementoblasts: role of the protein kinase A pathway. Endocrinology 141:4671–4680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elefteriou F, Ahn JD, Takeda S, Starbuck M, Yang X, Liu X, Kondo H, Richards WG, Bannon TW, Noda M, Clement K, Vaisse C, Karsenty G 2005 Leptin regulation of bone resorption by the sympathetic nervous system and CART. Nature 434:514–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porte D, Tuckermann J, Becker M, Baumann B, Teurich S, Higgins T, Owen MJ, Schorpp-Kistner M, Angel P 1999 Both AP-1 and Cbfa1-like factors are required for the induction of interstitial collagenase by parathyroid hormone. Oncogene 18:667–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson DR, Swarthout JT, Partridge NC 1999 Increased osteoblastic c-fos expression by parathyroid hormone requires protein kinase A phosphorylation of the cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate response element-binding protein at serine 133. Endocrinology 140:1255–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koe RC, Clohisy JC, Tyson DR, Pulumati MR, Cook TF, Partridge NC 1997 Parathyroid hormone versus phorbol ester stimulation of activator protein-1 gene family members in rat osteosarcoma cells. Calcif Tissue Int 61:52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]