Abstract

HBs antigen (HBsAg)183–191 (FLLTRILTI, R187 peptide) is a dominant human leucocyte antigen-A2 (HLA-A2)-restricted epitope associated with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Caucasian populations. However, its prevalence is poorly understood in China, where there is a high incidence of HBV infection. In this report, we sequenced the region of HBsAg derived from 103 Chinese patients. Approximately 16·5% of the patients bore a mutant HBsAg183–191 epitope in which the original arginine (R187) was substituted with a lysine (K187 mutant peptide). Importantly, K187 still bound to HLA-A2 with high affinity, and elicited specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses in HLA-A2/Kb transgenic mice. K187-specific CTLs were also generated successfully in acute hepatitis B (AHB) patients, indicating that this mutant epitope is processed and presented effectively. Our findings show that R187-specific CTLs can cross-react with the K187 peptide. These findings reveal that K187 still has the property of an HLA-A2 restricted epitope, and elicits a protective anti-HBV CTL response in humans.

Keywords: cytotoxic T lymphocyte, epitope, hepatitis B virus, mutation

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is extensively epidemic in the world. Its infection can result in acute and chronic hepatitis, and greatly enhance the risk of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [1]. Evidence suggests that a vigorous, multi-targeted cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response occurs during acute hepatitis B (AHB) [2–6], while the HBV-specific CTL response is very low or undetectable during chronic infection. Moreover, several reports have shown that CTL epitopes mutation abrogate recognition of HBV by prototype CTLs [7, 8], which favour chronic infection by allowing viruses to evade host immunity [9, 10]. These researches indicate that HBV-specific CTLs play a major role in the control and clearance of viral infection [11]. Thus, it is especially critical to identify dominant epitopes that will elicit strong CTL responses in HBV-infected patients. Although a number of epitopes in HBV antigens have been identified in European and northern American HBV patients [2, 4, 12–15], it remains unclear whether mutant epitopes still elicit CTL response in vivo. Theoretically, the T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire is large enough [16] that every viral mutation should be recognized by a specific TCR, thus allowing the host immune system to mount a novel response to mutant peptide-bearing viruses and control their replication. In addition, HBV has been classified into eight genotypes, A to H, according to the divergence of ≥ 8% in the complete genome nucleotide sequence [17–20]. Clinical investigation has indicated that genotypes B and C are the most frequent in China [21, 22], while other genotypes are more prevalent in Europe and North America [23–25]. Distinct distribution of the genotype may cause the sequence mutation of some originally identified epitopes in China. However, so far there has been a paucity of reports regarding epitope discrepancies in HBV-infected patients in China.

In this report we examined the prevalence of the HBV epitope, HBs antigen (HBsAg)183–191 (FLLTRILTI), which is a major human leucocyte antigen-A2 (HLA-A2)-restricted epitope [26]. Our results show that approximately 16·5% of HBV-infected patients have a mutation with an arginine to lysine switch at the fifth amino acid residue in the HBsAg183–191 (FLLTRILTI) epitope, K187. Importantly, subsequent identification showed K187 was still an HLA-A2-restricted epitope. Our findings may aid the design of more efficient HBV-specific epitope vaccines to boost anti-viral immune responses in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

Nine HLA-A2-positive patients (three with AHB and six with CHB) were enrolled for analysis of HBV peptide-specific CTLs. All the patients met the diagnosis standards of AHB and CHB, as described previously [27, 28]. Briefly, patients who display a serum HBsAg conversion within 6 months following onset of HBV infection are classified as AHB, while patients who have viral persistence for more than 6 months and typical manifestations of hepatitis or abnormal hepatic function are classified as CHB. Two HBV-uninfected healthy HLA-A2-positive individuals were used as controls for tetramer staining. One hundred and three samples with viral titres >107 copies/ml were chosen to investigate epitope sequence prevalence. Individuals with concurrent HCV, HDV, HGV or HIV infections or autoimmune liver disease were excluded from the study. Our protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing 302 Hospital and written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

Tissue typing and peptide synthesis

The HLA-A2 haplotype was determined with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated HLA-A2 monoantibody staining. The K187 mutant peptide and the H-Kd-restricted epitope, HBcAg87–95 (SYVNTNMGL) [29], were synthesized at GL Biochem Ltd (Shanghai, China). Peptide purity was >98%, as confirmed by reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry.

Amplification and sequencing of the epitope-encoding region of HBV

To amplify the nucleotide sequence that encodes the HBsAg183–191 epitope, we designed the following primers: 5′-CCTAGGACCCCTGCTCGTGTTACAG-3′ and 5′-CCCTACGAACCACTGAACAAATGGCAC-3′. The HBV genome was isolated from infected patients using virus genome extraction kits (TaKaRa Biotechnology (Dalian) Co. Ltd, Dalian, China), and stored at −80°C prior to use as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) template. Amplification was performed as follows: 5 min denaturing at 95°C, 30 cycles with 30 s denaturing at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 58°C and 48 s extension at 72°C. The amplified fragment was extracted from the gel and inserted into the vector using a T-A cloning method. At least three clones per sample were sequenced with a 3730 sequencer in Beijing (Sunbiotech Co. Ltd, Beijing, China).

Refolding of HLA-A2 molecules with peptide

HLA-A2 heavy and light chains and human β2 microglobulin (β2m) were overexpressed in Escherichia coli. The inclusion bodies of each protein were purified and dissolved in 8 M urea; 4 μg peptide was added to 500 ml refolding buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8·0), 400 mM l-arginine-HCl, 2 mM Na ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (NaEDTA), 0·5 mM oxidized glutathione and 5 mM reduced glutathione) followed by 15 mg β2m at 4°C. After 30 min, 15 mg HLA-A2 heavy chain was added gradually and the refolding buffer was stirred. The refolded protein was concentrated in a pressurized chamber and run over a Superdex 75 column.

Peptide binding assay

To determine whether the synthesized peptide could bind to HLA-A2 molecules, we measured peptide-induced HLA-A2 up-regulation on T2 cells [30, 31]. In brief, T2 cells were incubated with 50 μM of the candidate peptides and 3 μg/ml β2m in serum-free RPMI-1640 medium for 18 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Surface expression of HLA-A2 on the T2 cells was quantified using FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-A2 monoclonal antibody and analysed by flow cytometry. The fluorescence index (FI) was calculated as follows: FI = (mean fluorescence with a given peptide − mean fluorescence with no peptide)/(mean fluorescence with no peptide). Peptides with an FI greater than 1 were regarded as high-affinity epitopes.

Tetramer production and staining

Tetrameric HLA-A2 peptide complexes (tetramers) were constructed as described previously [31, 32]. Briefly, HLA-A2 heavy chain, with a Bir A site, and human β2m were expressed in bacteria and the purified inclusion bodies were denatured in 8 M urea buffer. The proteins were refolded with the peptide in vitro, as described above. The HLA-A2-peptide–β2m complexes were then purified through a Superdex 75 column and biotinylated with Bir A enzyme. The biotinylated complexes were purified further by gel filtration, and tetramerization was accomplished by mixing biotinylated HLA-A2-peptide–β2m complex and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated streptavidin at a molar ratio of 4 : 1. Peptide-induced lymphocyte cultures were incubated with PE-conjugated tetramers for 30 min at 4°C, and incubated with FITC-labelled anti-human CD8 monoclonal antibody (mAb) for an additional 30 min at 4°C. After washing with PBS, stained cells were fixed with 0·5% paraformaldehyde and analysed by flow cytometry [33–35].

Immunization of HLA-A2 transgenic mice

HLA-A2/Kb transgenic mice [36], a generous gift from Dr Cao Xuetao (Shanghai Second Military Medical University), were bred and maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities. Expression of HLA-A2 on the cellular membrane was assessed by flow cytometry using FITC-labelled HLA-A2-specific monoclonal antibody (eBioscience Co. Ltd, San Diego, CA, USA). Six to 8-week-old mice were immunized three times intramuscularly every 2 weeks with a mixture of 100 μg peptide with incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA), as described previously [37, 38]. Seven days after the last immunization, mouse splenocytes were isolated and specific CTL responses were analysed by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays.

Analysis of interferon (IFN)-γ-producing T cells by ELISPOT

ELISPOT was performed using a commercially available human or mice interferon-γ (IFN-γ) ELISPOT kit (e-Bioscience Co. Ltd). Briefly, 96-well polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-treated microtitre plates were coated with anti-IFN-γ mAb at 4°C overnight. Then 2 × 105 cells, which were stimulated with 10 μg/ml peptide for 24 h in 24-well culture plates, were added to each well of the ELISPOT plate. After 16–24 h incubation the cells were discarded and the assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Wells were imaged with an ELISPOT reader, and the spots were counted with an automated system, after setting parameters for size, intensity and gradient with Saizhi ELISPOT analysis software. A response was considered positive if the mean number of spot-forming cells (SFCs) in triplicate sample wells exceeded background. Assay results were displayed as SFC per 1 × 106 cells.

Results

Prevalence of the HBsAg183–191 epitope sequence in CHB patients

Because the variability and distribution of HBV differs among global populations, the epitope sequence identified in Caucasian patients may be mutated in Chinese patients. In order to investigate the prevalence and mutant state of the HBsAg183–191 epitope in Chinese patients, we enrolled 103 subjects randomly from more than 500 CHB patients. The HBV genome was amplified by PCR, DNA fragments containing the HBsAg183–191 epitope sequence were cloned and at least three clones from each sample were confirmed further by direct DNA sequencing. Of the 103 samples, 17 patients (16·5%) had a mutant epitope in whom arginine was substituted with a lysine (Table 1). The results indicate that a considerable percentage of Chinese patients harbour HBV with the K187 mutant HBsAg183–191 sequence.

Table 1.

Frequency of the HBs antigen (HBsAg)183–191 sequence in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

| Item | K187 mutant peptide | R187 peptide | Total sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | 17 | 86 | 103 |

The HBV genome was extracted from 103 chronic hepatitis B patients and the HBsAg183–191 sequence was amplified by polymerase chain reaction. The fragment was cloned into a pMD 18-T vector and three clones were sequenced. Of the 103 samples, 17 had the K187 mutant peptide sequence and 86 had the R187 peptide sequence.

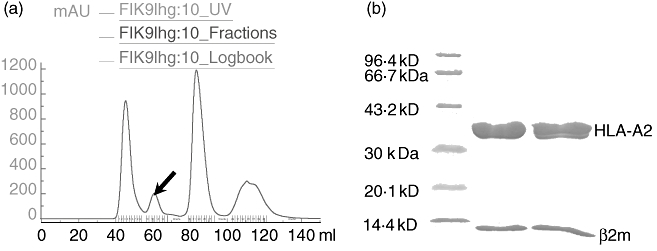

HLA-A2 heavy chain can refold with β2m in the presence of K187 mutant peptide

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted epitopes form a complex with MHC-I molecules within the cellular endoplasmic reticulum (ER). The complex is then displayed on the cellular membrane for peptide presentation. Individual MHC-I molecules are not stable in vitro unless they have bound a suitable epitope. In the presence of an epitope, the heavy chain of MHC-I can refold with β2m [39]. To determine whether the K187 mutant peptide still has the property of an HLA-A2-restricted epitope, we performed a refolding assay with the K187 mutant peptide, HLA-A2 and β2m at a molar ratio of 1 : 4·5 : 18. The refolding efficiency was determined by gel filtration analysis. As shown in Fig. 1a, HLA-A2 molecules/peptide complexes formed in vitro. This was confirmed further by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis (Fig. 1b). These results indicate that the K187 peptide retains the capacity to bind HLA-A2, encouraging us to investigate its characteristics further.

Fig. 1.

Refolding assay using the K187 mutant peptide. (a) Human leucocyte antigen-A2 folded with β2m in the presence of K187 mutant peptide at 4°C. The folded complex was run over a Superdex 75 column. The second peak represents the refolded product (see arrow). (b) Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis assay using the complex represented by the second peak.

K187 mutant peptide up-regulates expression of HLA-A2 molecules on T2 cells

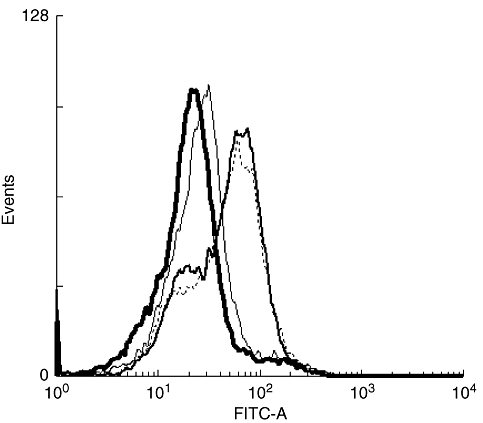

The affinity of peptides for MHC-I is associated closely with their immunogenicity [40]. High-affinity peptides are immunogenic, while low-affinity peptides are not. Affinity for MHC-I is often evaluated with the competitive binding inhibition assay [17]. It is also monitored by detection of peptide-induced up-regulation of HLA-A2 molecules on transporter protein for antigenic peptide (TAP)-deficient T2 cells [41]. To measure the affinity of K187 for HLA-A2, we adopted a protocol in which affinity is expressed as a fluorescence index (FI) value, as described previously [30, 31, 42]. As shown in Table 2, the FI of K187 mutant peptide reached 1·575, while the FI of the control peptide, HBcAg87–95, reached only 0·193. Simultaneously, we performed the experiment with the R187 epitope and identified its FI value as 1·632. The histograms of three peptides were overlaid with the negative control curve, using WinMDI version 2·9 software (Fig. 2). Both K187 mutant peptide and R187 epitope showed a higher fluorescence intensity than the control peptide, HBcAg87–95, and no peptide samples. These results indicate that K187 has an almost equally high affinity for HLA-A2 as R187, and possesses the property of a CD8+ CTL epitope.

Table 2.

Binding affinity of K187 or R187 to human leucocyte antigen-A2 molecule on T2 cells.

| Name of sample | Mean fluorescence value | FI value |

|---|---|---|

| β2m control well | 723 | 0 |

| HBcAg87–95 peptide control well | 863 | 0·193 |

| K187 mutant peptide well | 1862 | 1·575 |

| R187 mutant peptide well | 1903 | 1·632 |

Mean fluorescence value of T2 cells stained with the fluorescein isothiocyanate-human leucocyte antigen-A2 (FITC-HLA-A2) monoclonal antibody and fluorescence index (FI) value. The FI value was obtained according to the following formula: FI = (mean FITC fluorescence of the given peptide − mean FITC fluorescence without peptide)/mean FITC fluorescence without peptide.

Fig. 2.

Human leucocyte antigen-A2 expressing on T2 cells: thick-line histogram represents T2 cells incubated with β2m protein alone; thin-line histogram represents T2 cells incubated with HBcAg87–95 control peptide and β2m; broken-line histogram represents T2 cells incubated with K187 mutant peptide and β2m; narrow-brush histogram represents T2 cells incubated with R187 peptide.

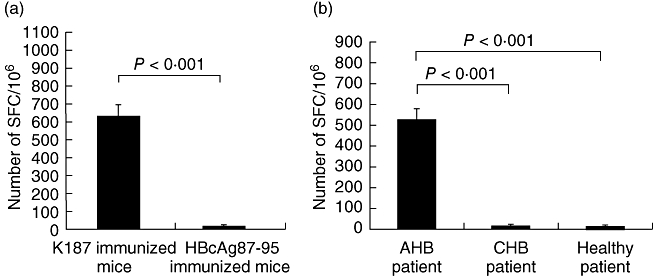

K187 mutant peptide elicits specific CD8+ CTL responses in HLA-A2/Kb transgenic mice

It is critical to show that CD8+ CTL epitopes can elicit a specific CTL response efficiently in vivo. To address this, we immunized HLA-A2/Kb transgenic mice with K187 mutant peptide or the control peptide, HBcAg87–95. After three immunizations, splenocytes were isolated and specific CTL responses were analysed by ELISPOT. As shown in Fig. 3a, K187 mutant peptide mounted a peptide-specific CTL efficiently in HLA-A2/Kb mice, while the control peptide did not. The results indicate that the K187 mutant peptide is presented to CD8+ T cells in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Detection of hepatitis B virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) by interferon (IFN)-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay. (a) Mice were immunized three times with 100 μg K187 mutant or HBcAg87–95 control peptide. Seven days following the third injection, splenocytes were isolated and peptide-specific IFN-γ cells were quantified by ELISPOT. (b) K187-specific CTLs were detected in representative acute hepatitis B and chronic hepatitis B patients or healthy subjects. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from each individual were isolated, stimulated with 10 μg/ml peptide, and IFN-γ responses were detected by ELISPOT assay.

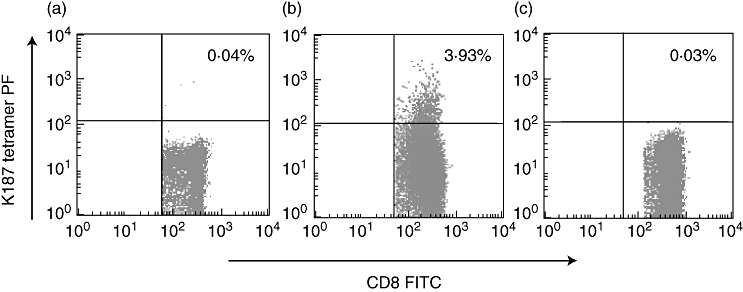

K187-specific CTLs are detected in AHB patients, but not in CHB patients

Based on our results, we expected the K187 mutant peptide to elicit specific CTLs in HBV-infected patients. To confirm this further, we stained the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) with tetramer in HLA-A2-positive AHB and CHB patients. Approximately 3·93% of the total CD8+ T cells were specific for K187 in the AHB patients (Fig. 4). ELISPOT analysis supported the result (Fig. 3b). Through PCR amplification and direct cDNA sequencing, we confirmed that the HBsAg183–191 sequence in these patients is the K187 mutant peptide, FLLTKILTI. Our findings indicate that patients who recover successfully from an acute self-limiting HBV infection develop strong K187 epitope-specific CTL responses.

Fig. 4.

Tetramer staining of K187-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared from the blood of uninfected healthy human leucocyte antigen-A2-positive person (a), acute hepatitis B (b) and chronic hepatitis B patients (c) by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and stained for 15 min with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled anti-human CD8 monoclonal antibody and phycoerythrin-conjugated K187 mutant peptide tetramer.

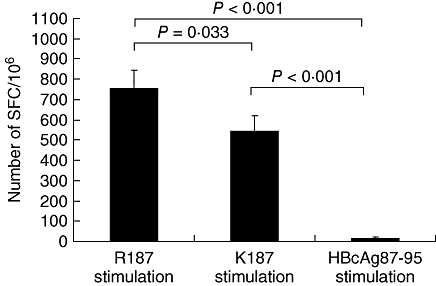

R187 epitope-specific CTLs can cross-react with K187 epitope

To address cross-reactivity between the above-mentioned two epitopes, we enrolled two HLA-A2 restricted patients who recovered from acute HBV infection and were found with HBV-infected R187 epitopes. PBMCs of the patients were isolated and stimulated with R187 and K187 epitopes, respectively. Secretion of IFN-γ by R187-specific CTLs were detected with ELISPOT assay. As shown in Fig. 5, both R187 and K187 epitopes can stimulate the R187 epitope-specific CTLs to secrete IFN-γ. The data indicate that R187 and K187 epitopes can cross-react.

Fig. 5.

Cross-reaction between the K187 epitope and R187 epitope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL): R187-specific CTLs in a human leucocyte antigen-A2-restricted acute hepatitis B patient were stimulated with K187 and R187 epitope, respectively, in enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) plates for 24 h. The epitope-specific CTLs were counted with ELISPOT reader.

Discussion

Epitopes in HBV antigens are important for viral clearance in patients. Many epitopes have been identified within the HBV core [43, 44], envelope [17], polymerase [4] and Xproteins [20] of infected Caucasian individuals. As the HBV genome is variable, HBV epitope sequences often generate mutations. However, very little research has focused upon the prevalence of these mutations and their effect on CTL generation, particularly in China. Here, we found that approximately 16·5% of HBV-infected Chinese patients bore a mutant HBsAg183–191 epitope in which the original arginine (R187) was substituted with a lysine (K187 mutant peptide). In addition, the mutated K187 epitope can cross-react with R187-specific CTLs, and elicits a protective anti-HBV CTL response in Chinese patients with HBV infection.

In this study, we found that the mutant sequence of the HBsAg183–191 epitope, K187, can bind effectively to HLA-A2 molecules. Our results were not consistent with other reports illustrating that mutant HBV epitopes have a reduced ability to bind HLA-A2 molecules [11]. The short peak of the refolding complex in Fig. 1 did not suggest that HLA-A2 and β2m have a lower folding efficiency in the presence of K187. A parallel experiment using the HBsAg183–191 epitope confirmed this result (data not shown). Instead, the short peak was likely to be caused by the hydrophobicity of the peptide, which decreased its water solubility. FI values were also very similar between the K187 mutant and R187 peptides (data not shown). These results can be explained by previous findings that interior amino acid residues in HBV epitopes are required for TCR interaction [45]. Their mutation does not affect the binding ability of epitope to MHC-I molecule [46, 47].

Previous studies have shown that substitution of internal amino acid residues in some epitopes of HBV disrupts the ability of the virus to be recognized by TCRs [11, 12, 48]. In this study, we found that K187-specific CTLs can be primed in HLA-A2/Kb transgenic mice and in patients with acute HBV infection, indicating that the mutant peptide complexes efficiently with MHC-I molecules and interacts with the TCR. Our study is the first to confirm that the K187 mutant epitope can induce CTLs in vivo.

Some epitope mutations favour virus escape from the host immune response [14, 49]. However, our findings suggest that this may be not the case for the K187 mutation, as this epitope still induced HBV-specific CTLs in vivo. Alternatively, these HBsAg183–191-specific CTLs may still respond to mutant epitope by different TCRs which have a different Vβ chain [48, 50]. In addition, many HBV epitopes are found in the surface, core and polymerase proteins [4, 17–19]. These epitopes also elicit CTLs in vivo and can contribute to the elimination of the K187 mutant HBV. However, because our investigation does not show other mutations at the 187 position of the HBsAg183–191 epitope, we do not know whether or not other mutations at this position cause escape from the host immune response. Riedl et al. have reported that mutant epitopes can disrupt the immune tolerance of prototype epitopes, even with only one amino acid substitution [51]. Our findings confirm further that R187-specific CTLs can cross-react with the K187 epitope. In future, according to the research by Riedl et al., the K187 mutant epitope is a good choice to use to disrupt the immune tolerance of the R187 epitope-bearing HBV to cure CHB patients.

Overall, our results show that the substitution of K187 for R187 in the HBsAg183–191 sequence affects neither epitope binding to HLA-A2 nor CTL recognition of the epitope. Indeed, K187 is an efficient HLA-A2-restricted immunogenic peptide capable of inducing an anti-HBV-specific CTL response in AHB patients. Our findings will aid the design of alternative therapies for CHB patients in China.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to technician Songshan Wang for performing the ELISPOT assay, technician Fulian Liao for helping isolate the splenocyte from mice, technician Chunbao Zhou for FACS analysis, Professor Xuetao Cao for providing HLA-A2 transgenic mice, Yanning Song for graphic preparation and Dr Zhang Zheng for critical reading of our manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Frontier Research Program (Project 973) of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (grant numbers 2005CB522901, 2001CB51003 and 2005CB523001).

References

- 1.Chisari FV, Ferrari C. Hepatitis B virus immunopathogenesis. Annu Rev Immunology. 1995;13:29–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobao Y, Sugi K, Tomiyama H, et al. Identification of hepatitis B virus-specific CTL epitopes presented by HLA-A*2402, the most common HLA class I allele in East Asia. J Hepatol. 2001;34:922–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boettler T, Spangenberg HC, Neumann-Haefelin C, et al. T cells with a CD4+CD25+ regulatory phenotype suppress in vitro proliferation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:7860–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7860-7867.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rehermann B, Fowler P, Sidney J, et al. The cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to multiple hepatitis B virus polymerase epitopes during and after acute viral hepatitis. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1047–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster GJ, Reignat S, Maini MK, et al. Incubation phase of acute hepatitis B in man: dynamic of cellular immune mechanisms. Hepatology. 2000;32:1117–24. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohr HF, Krug S, Herr W, et al. Quantitative and functional analysis of core-specific T-helper cell and CTL activities in acute and chronic hepatitis B. Liver. 1998;18:405–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1998.tb00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang H-R, Tang G-I, Sun M, et al. Molecular biological features and clinical significance of hepatitis B virus genotype in Nanjin. World J Infect. 2004;4:232–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan L, Hou J-L, Jiang S, et al. A study on the relationship between HBV genotype and outcome of hepatitis B virus infection. J Chin Physicians. 2004;6:1347–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao JH. Hepatitis B viral genotypes: clinical relevance and molecular characteristics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:643–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grandjacques C, Pradat P, Stuyver L, et al. Rapid detection of genotypes and mutations in the pre-core promoter and the pre-core region of hepatitis B virus genome: correlation with viral persistence and disease severity. J Hepatol. 2000;33:430–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertoletti A, Costanzo A, Chisari FV, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte response to a wild type hepatitis B virus epitope in patients chronically infected by variant viruses carrying substitutions within the epitope. J Exp Med. 1994;180:933–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertoletti A, Sette A, Chisari FV, et al. Natural variants of cytotoxic epitopes are T-cell receptor antagonists for antiviral cytotoxic T cells. Nature. 1994;369:407–10. doi: 10.1038/369407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klenerman P, Zinkernagel RM. Original antigenic sin impairs cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to viruses bearing variant epitopes. Nature. 1998;394:482–5. doi: 10.1038/28860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips RE, Rowland-Jones S, Nixon DF, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus genetic variation that can escape cytotoxic T cell recognition. Nature. 1991;354:453–9. doi: 10.1038/354453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thimme R, Wieland S, Steiger C, et al. CD8(+) T cells mediate viral clearance and disease pathogenesis during acute hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:68–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.68-76.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westland CE, Yang H, Delaney WEt, et al. Week 48 resistance surveillance in two phase 3 clinical studies of adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2003;38:96–103. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nayersina R, Fowler P, Guilhot S, et al. HLA A2 restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to multiple hepatitis B surface antigen epitopes during hepatitis B virus infection. J Immunol. 1993;150:4659–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertoletti A, Chisari FV, Penna A, et al. Definition of a minimal optimal cytotoxic T-cell epitope within the hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid protein. J Virol. 1993;67:2376–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2376-2380.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung MK, Yoon H, Min SS, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes with peptides in vitro: identification of candidate T-cell epitopes in hepatitis B virus X antigen. J Immunother. 1999;22:279–87. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199907000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang YK, Kim NK, Park JM, et al. HLA-A2 1 restricted peptides from the HBx antigen induce specific CTL responses in vitro and in vivo. Vaccine. 2002;20:3770–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis MM, Bjorkman PJ. T-cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature. 1988;334:395–402. doi: 10.1038/334395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, et al. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:2575–83. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-10-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norder H, Courouce AM, Magnius LO. Complete genomes, phylogenetic relatedness, and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology. 1994;198:489–503. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, et al. A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:67–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO. Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2059–73. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertoni R, Sidney J, Fowler P, Chesnut RW, Chisari FV, Sette A. Human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-binding supermotifs predict broadly cross-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in patients with acute hepatitis. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:503–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI119559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rehermann B, Pasquinelli C, Mosier SM, Chisari FV. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) sequence variation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes is not common in patients with chronic HBV infection. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1527–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI118191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu D, Fu J, Jin L, et al. Circulating and liver resident CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells actively influence the antiviral immune response and disease progression in patients with hepatitis B. J Immunol. 2006;177:739–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuhrober A, Wild J, Pudollek HP, Chisari FV, Reimann J. DNA vaccination with plasmids encoding the intracellular (HBcAg) or secreted (HBeAg) form of the core protein of hepatitis B virus primes T cell responses to two overlapping Kb- and Kd-restricted epitopes. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1203–12. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.8.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Passoni L, Scardino A, Bertazzoli C, et al. ALK as a novel lymphoma-associated tumor antigen: identification of 2 HLA-A2.1-restricted CD8+ T-cell epitopes. Blood. 2002;99:2100–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang B, Chen H, Jiang X, et al. Identification of an HLA-A*0201-restricted CD8+ T-cell epitope SSp-1 of SARS-CoV spike protein. Blood. 2004;104:200–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ju DW, Tao Q, Lou G, et al. Interleukin 18 transfection enhances antitumor immunity induced by dendritic cell-tumor cell conjugates. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3735–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJ, et al. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuzushima K, Hayashi N, Kudoh A, et al. Tetramer-assisted identification and characterization of epitopes recognized by HLA A*2402-restricted Epstein–Barr virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2003;101:1460–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lechner F, Wong DK, Dunbar PR, et al. Analysis of successful immune responses in persons infected with hepatitis C virus. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1499–512. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vitiello A, Marchesini D, Furze J, Sherman LA, Chesnut RW. Analysis of the HLA-restricted influenza-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in transgenic mice carrying a chimeric human–mouse class I major histocompatibility complex. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1007–15. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yasutomi Y, Palker TJ, Gardner MB, Haynes BF, Letvin NL. Synthetic peptide in mineral oil adjuvant elicits simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1993;151:5096–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou M, Xu D, Li X, et al. Screening and identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-specific CTL epitopes. J Immunol. 2006;177:2138–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li H, Zhou M, Han J, et al. Generation of murine CTL by a hepatitis B virus-specific peptide and evaluation of the adjuvant effect of heat shock protein glycoprotein 96 and its terminal fragments. J Immunol. 2005;174:195–204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sette A, Vitiello A, Reherman B, et al. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1994;153:5586–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Regner M, Claesson MH, Bregenholt S, Ropke M. An improved method for the detection of peptide-induced upregulation of HLA-A2 molecules on TAP-deficient T2 cells. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1996;13:30–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuzushima K, Hayashi N, Kimura H, Tsurumi T. Efficient identification of HLA-A*2402-restricted cytomegalovirus-specific CD8(+) T-cell epitopes by a computer algorithm and an enzyme-linked immunospot assay. Blood. 2001;98:1872–81. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penna A, Del Prete G, Cavalli A, et al. Predominant T-helper 1 cytokine profile of hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid-specific T cells in acute self-limited hepatitis B. Hepatology. 1997;25:1022–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Penna A, Chisari FV, Bertoletti A, et al. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize an HLA-A2-restricted epitope within the hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid antigen. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1565–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bertoletti A, Southwood S, Chesnut R, et al. Molecular features of the hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid T-cell epitope 18–27: interaction with HLA and T-cell receptor. Hepatology. 1997;26:1027–34. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madden DR, Garboczi DN, Wiley DC. The antigenic identity of peptide–MHC complexes: a comparison of the conformations of five viral peptides presented by HLA-A2. Cell. 1993;75:693–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90490-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogg GS, McMichael AJ. HLA–peptide tetrameric complexes. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:393–6. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maini MK, Reignat S, Boni C, et al. T cell receptor usage of virus-specific CD8 cells and recognition of viral mutations during acute and persistent hepatitis B virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:3067–78. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200011)30:11<3067::AID-IMMU3067>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pircher H, Moskophidis D, Rohrer U, Burki K, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Viral escape by selection of cytotoxic T cell-resistant virus variants in vivo. Nature. 1990;346:629–33. doi: 10.1038/346629a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding YH, Smith KJ, Garboczi DN, Utz U, Biddison WE, Wiley DC. Two human T cell receptors bind in a similar diagonal mode to the HLA-A2/Tax peptide complex using different TCR amino acids. Immunity. 1998;8:403–11. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80546-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riedl P, Bertoletti A, Lopes R, Lemonnier F, Reimann J, Schirmbeck R. Distinct, cross-reactive epitope specificities of CD8 T cell responses are induced by natural hepatitis B surface antigen variants of different hepatitis B virus genotypes. J Immunol. 2006;176:4003–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]