Abstract

Since a constant supply of oxygen is essential to sustain life, organisms have evolved multiple defence mechanisms to ensure maintenance of the delicate balance between oxygen supply and demand. However, this homeostatic balance is perturbed in response to a severe impairment of oxygen supply, thereby activating maladaptive signalling cascades that result in cardiac damage. Past research efforts have largely focused on determining the pathophysiological effects of severe lack of oxygen. By contrast, and as reviewed here, exposure to moderate chronic hypoxia may induce cardioprotective properties. The hypothesis put forward is that chronic hypoxia triggers regulatory pathways that mediate long-term cardiac metabolic remodelling, particularly at the transcriptional level. The novel proposal is that exposure to chronic hypoxia triggers (a) oxygen-sensitive transcriptional modulators that induce a switch to increased carbohydrate metabolism (fetal gene programme) and (b) enhanced mitochondrial respiratory capacity to sustain and increase efficiency of mitochondrial energy production. These compensatory protective mechanisms preserve contractile function despite hypoxia.

Hypoxia is the result of an imbalance between oxygen supply and demand. Tissue hypoxia is caused by interrupted coronary blood flow and/or a reduction in arterial blood oxygen partial pressure  (Ostadal et al. 1999). It is important to clearly distinguish the differences between hypoxia and ischaemia. Ischaemia signifies reduced tissue blood flow, causing a decrease in substrate supply and removal while hypoxia refers to lowered

(Ostadal et al. 1999). It is important to clearly distinguish the differences between hypoxia and ischaemia. Ischaemia signifies reduced tissue blood flow, causing a decrease in substrate supply and removal while hypoxia refers to lowered  . Hypoxia is therefore an important component of ischaemia, i.e. diminished tissue oxygen supply due to the reduction in blood flow. The effects of ischaemia are usually more severe than hypoxia and typically include lactic acidosis due to anaerobic glycolysis, diminished mitochondrial energy production and cell death (reviewed by Reimer & Jennings, 1992; Williams & Benjamin, 2000). The focus of this review is, however, on hypoxia in its pure form (i.e. no reduction in blood flow), a condition that occurs at high altitude. Furthermore, emphasis is placed on chronic instead of acute exposures to hypoxia. Of note, studies in the field exhibit a considerable degree of variability depending on the degree and duration of the hypoxic stimulus. For the purposes of this review article, the term ‘chronic hypoxia’ broadly refers to a condition where the hypoxic exposure did not result in significant harmful effects to organisms.

. Hypoxia is therefore an important component of ischaemia, i.e. diminished tissue oxygen supply due to the reduction in blood flow. The effects of ischaemia are usually more severe than hypoxia and typically include lactic acidosis due to anaerobic glycolysis, diminished mitochondrial energy production and cell death (reviewed by Reimer & Jennings, 1992; Williams & Benjamin, 2000). The focus of this review is, however, on hypoxia in its pure form (i.e. no reduction in blood flow), a condition that occurs at high altitude. Furthermore, emphasis is placed on chronic instead of acute exposures to hypoxia. Of note, studies in the field exhibit a considerable degree of variability depending on the degree and duration of the hypoxic stimulus. For the purposes of this review article, the term ‘chronic hypoxia’ broadly refers to a condition where the hypoxic exposure did not result in significant harmful effects to organisms.

Physiological hypoxia and cardioprotection

Since a constant, uninterrupted supply of oxygen is essential to sustain life, organisms possess innate defence mechanisms to increase tolerance to acute and chronic oxygen lack. High-altitude dwellers have successfully evolved adaptive regulatory mechanisms to survive in a chronic hypoxic environment. Defence mechanisms include erythropoiesis and angiogenesis to augment red blood cell mass and oxygen delivery, and metabolic remodelling that increases utilization of oxygen-efficient fuel substrates such as carbohydrates (Hochachka, 1998; Ostadal et al. 1999; Semenza, 1999).

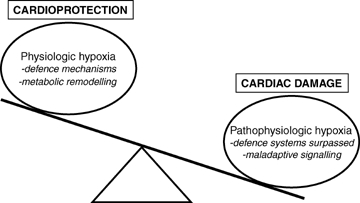

Exposure to chronically reduced oxygen levels is associated with increased protection against various disease states. Indeed, populations residing at high altitude display lower incidences of hypertension (Hurtado, 1960) and mortality rates for coronary heart disease (Mortimer et al. 1977; Voors & Johnson, 1979). Exposure to lower  may also protect organisms when subsequently challenged by an acute oxidant stress. For example, a reduced incidence of myocardial infarctions was observed in high-altitude residents (Hurtado, 1960). However, these studies have several inherent weaknesses, including the lack of properly matched control subjects and additional confounding factors such as socio-economic status, ethnicity and migratory patterns (high- to low-altitude regions) (Regensteiner & Moore, 1985). Further human studies are therefore required to fully address these concerns. In contrast, data generated by animal studies more strongly support the hypoxia-induced cardioprotection paradigm. For example, Meerson et al. (1973) found that rats exposed to hypobaric hypoxia (simulating high-altitude exposure) displayed an improved rate of recovery and reduced myocardial necrosis after coronary artery ligation. Moreover, later studies reported reduced incidences of arrhythmias (Meerson et al. 1987; Asemu et al. 1999) and increased myocardial resilience to severe oxygen deprivation (Turek et al. 1980; Tajima et al. 1994) in animals pre-exposed to chronic hypoxia. A novel concept therefore emerges from these data, i.e. exposure to moderate oxygen lack (physiological hypoxia) triggers (a) defence mechanisms to deal with reduced oxygen supply, and (b) cardioprotective programmes.

may also protect organisms when subsequently challenged by an acute oxidant stress. For example, a reduced incidence of myocardial infarctions was observed in high-altitude residents (Hurtado, 1960). However, these studies have several inherent weaknesses, including the lack of properly matched control subjects and additional confounding factors such as socio-economic status, ethnicity and migratory patterns (high- to low-altitude regions) (Regensteiner & Moore, 1985). Further human studies are therefore required to fully address these concerns. In contrast, data generated by animal studies more strongly support the hypoxia-induced cardioprotection paradigm. For example, Meerson et al. (1973) found that rats exposed to hypobaric hypoxia (simulating high-altitude exposure) displayed an improved rate of recovery and reduced myocardial necrosis after coronary artery ligation. Moreover, later studies reported reduced incidences of arrhythmias (Meerson et al. 1987; Asemu et al. 1999) and increased myocardial resilience to severe oxygen deprivation (Turek et al. 1980; Tajima et al. 1994) in animals pre-exposed to chronic hypoxia. A novel concept therefore emerges from these data, i.e. exposure to moderate oxygen lack (physiological hypoxia) triggers (a) defence mechanisms to deal with reduced oxygen supply, and (b) cardioprotective programmes.

Conversely, a severe impairment of oxygen supply (pathophysiological hypoxia) may exceed the host organism's defence apparatus resulting in a maladaptive cardiac phenotype (Fig. 1). For example, hypoxia is a major contributor to cardiac pathophysiology, including myocardial infarction, cyanotic congenital heart disease and chronic cor pulmonale (Grifka, 1999; Ostadal et al. 1999; Budev et al. 2003). Chronic oxygen lack leads to increased pulmonary vasoconstriction, an attempt to redistribute pulmonary blood flow from regions of low  to high oxygen availability (Von Euler & Liljestrand, 1946; Arias-Stella & Saldana, 1962; Hislop & Reid, 1976). However, chronic pulmonary vasoconstriction may result in pulmonary hypertension, increasing afterload on the right ventricle that may eventually lead to heart failure.

to high oxygen availability (Von Euler & Liljestrand, 1946; Arias-Stella & Saldana, 1962; Hislop & Reid, 1976). However, chronic pulmonary vasoconstriction may result in pulmonary hypertension, increasing afterload on the right ventricle that may eventually lead to heart failure.

Figure 1.

Delicate balance between oxygen supply and demand Physiological hypoxia triggers various defence mechanisms, for e.g. erythropoiesis and angiogenesis to increase red blood cell mass and oxygen delivery to the heart. Adaptive cardiac metabolic remodelling (switch to greater carbohydrate versus fatty acid utilization) is also proposed to play a key role in hypoxia-mediated cardioprotection. Disruption of this homeostatic balance (pathophysiological hypoxia) may overwhelm an organism's defence machinery, triggering maladaptive signalling cascades that result in myocardial damage.

Previous research has largely focused on the patho-physiological effects of hypoxia, revealing a complex interplay between signalling cascades, intracellular mediators and subcellular organelles such as the mitochondrion (Solaini & Harris, 2005). However, the regulatory mechanisms underlying the cardioprotective effects of physiological hypoxia are less well understood. Here greater insight may reveal novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of heart disease.

Adaptive metabolic reorganization, i.e. increased reliance on carbohydrates as cardiac fuel substrate (versus fatty acids) and augmented mitochondrial respiratory capacity, may play a central role in hypoxia-mediated cardioprotection (Meerson). In this review, a proposal is made that chronic hypoxia triggers regulatory pathways that mediate long-term adaptive cardiac metabolic changes, particularly at the transcriptional level. It is further hypothesized that chronic hypoxia triggers (a) oxygen-sensitive transcriptional modulators that induce a switch to greater carbohydrate utilization (fetal gene programme) and (b) enhanced mitochondrial respiratory function to sustain and increase efficiency of mitochondrial energy production, thereby preserving contractile function. This hypothesis is examined by discussing: (1) oxygen sensing; (2) the regulation of cardiac fuel substrate utilization; and (3) mitochondrial respiratory function in response to chronic hypobaric hypoxia, with particular emphasis on the control of gene transcription.

Oxygen sensing

Organisms require a sophisticated oxygen sensing mechanism(s) to rapidly respond to physiological or pathophysiological alterations in  , thereby maintaining intracellular oxygen homeostasis. Oxygen sensor systems should meet several requirements, including (a) the ability to sense oxygen concentrations, (b) initiating intracellular signalling cascades in response to altered

, thereby maintaining intracellular oxygen homeostasis. Oxygen sensor systems should meet several requirements, including (a) the ability to sense oxygen concentrations, (b) initiating intracellular signalling cascades in response to altered  , and (c) the capacity to deal with the differing

, and (c) the capacity to deal with the differing  thresholds for various organs (Acker et al. 2006). Candidate oxygen sensor systems in the heart include the NADPH oxidase enzyme family and components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (complex III or IV) (Acker et al. 2006; Murdoch et al. 2006).

thresholds for various organs (Acker et al. 2006). Candidate oxygen sensor systems in the heart include the NADPH oxidase enzyme family and components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (complex III or IV) (Acker et al. 2006; Murdoch et al. 2006).

Oxygen sensors usually relay alterations in  to the cellular machinery via intracellular signalling intermediates. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) may play a pivotal role in oxygen sensing by acting as secondary messengers, modulating signalling pathways and gene transcription by covalent modification of target molecules (referred to as ‘redox signalling’) (Shah & Sauer, 2006). Here lower, physiological ROS levels (unlike higher damaging levels) are thought to trigger adaptive cascades in the heart. For example, both NADPH oxidase and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (complexes I and III) can produce ROS, thus identifying a potential mechanism whereby an intracellular response(s) may be initiated to counteract

to the cellular machinery via intracellular signalling intermediates. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) may play a pivotal role in oxygen sensing by acting as secondary messengers, modulating signalling pathways and gene transcription by covalent modification of target molecules (referred to as ‘redox signalling’) (Shah & Sauer, 2006). Here lower, physiological ROS levels (unlike higher damaging levels) are thought to trigger adaptive cascades in the heart. For example, both NADPH oxidase and the mitochondrial electron transport chain (complexes I and III) can produce ROS, thus identifying a potential mechanism whereby an intracellular response(s) may be initiated to counteract  perturbations. However, varying results for ROS production under hypoxic conditions have been found, with some studies reporting increased and others decreased mitochondrial ROS production (Acker et al. 2006). The differing responses may be due to variations in experimental models employed, the degree and duration of hypoxia, and limitations of ROS quantification methodologies. However, a single group reported increased radical production in response to hypoxia when employing the sensitive electron spin resonance technique (Liu et al. 2001). It is the author's view that higher physiological ROS production during chronic hypoxic exposure may play an important role in transmitting

perturbations. However, varying results for ROS production under hypoxic conditions have been found, with some studies reporting increased and others decreased mitochondrial ROS production (Acker et al. 2006). The differing responses may be due to variations in experimental models employed, the degree and duration of hypoxia, and limitations of ROS quantification methodologies. However, a single group reported increased radical production in response to hypoxia when employing the sensitive electron spin resonance technique (Liu et al. 2001). It is the author's view that higher physiological ROS production during chronic hypoxic exposure may play an important role in transmitting  changes to the cellular apparatus, thereby initiating numerous adaptive responses including cardiac metabolic remodelling.

changes to the cellular apparatus, thereby initiating numerous adaptive responses including cardiac metabolic remodelling.

Chronic hypoxia and cardiac fuel substrate switching

Fatty acids serve as the major fuel substrate for the normal, fasting adult mammalian heart, providing ∼60–80% of its energy requirements (Opie, 1969). The rest of the heart's ATP is derived from glucose and lactate in nearly equal proportions. After uptake, glucose is rapidly phosphorylated to glucose-6-P. The latter has several metabolic fates, including its complete oxidation to acetyl-CoA and carbon dioxide via the Krebs cycle. Moreover, the partial breakdown of glucose to pyruvate generates ATP without any oxygen requirements (anaerobic glycolysis) while under certain conditions (e.g. hypoxia) pyruvate may be converted to lactate. Additional metabolic fates of glucose include its conversion to glycogen (for rapid utilization at a later stage), carboxylation to oxaloacetate (first reaction of gluconeogenesis) and flux through the polyol, hexosamine biosynthetic and pentose phosphate pathways (Bouche et al. 2004).

Cardiac fuel substrate utilization is dynamic and may be altered according to the prevailing physiological or pathophysiological milieu (Stanley et al. 2005). For example, high-altitude natives like the Himalayan Sherpas and the Andean Quechuas display enhanced glucose uptake (Holden et al. 1995). Moreover, lower PCr/ATP ratios (a useful indicator of energetic status) were observed in Sherpa hearts, suggesting an increased contribution of glucose to myocardial aerobic ATP production (Hochachka et al. 1996). Data on actual myocardial fuel substrate preferences in humans in response to high altitude and matched to appropriate control subjects are limited. However, Moret (1971/72) reported higher cardiac lactate and lower fatty acid utilization in South American individuals residing at high altitude. In agreement, lowland subjects exposed to acute altitude simulation, and rats to hypobaric hypoxia, both displayed increased glucose uptake (Hurford et al. 1990; Roberts et al. 1996).

Increased glucose utilization in response to hypoxia may occur since it is a more oxygen-efficient fuel substrate to generate ATP compared with fatty acids. On the contrary, long-chain fatty acids are associated with reduced cardiac efficiency, i.e. the ATP produced per mole of oxygen consumed. This may, in part, be due to a single round of β-oxidation requiring two ATPs for the activation of fatty acids, a reaction catalysed by fatty acyl-CoA synthetase (thiokinase). However, a switch from exclusive use of long-chain fatty acids as an energy source to the exclusive use of glucose is calculated to increase the efficiency of ATP production by 12–14%. Since a complete substrate switch is unlikely, the energetic benefit of greater glucose utilization under hypoxic conditions may appear relatively small. However, another explanation is provided by fatty acid-mediated uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in diminished mitochondrial ATP production for a given rate of oxygen consumption (Wojtczak & Wieckowski, 1999). For example, modest elevation of free fatty acid levels increased the oxygen uptake of the isolated rat heart by ∼33% (Boehm et al. 2001).

The regulatory mechanisms directing cardiac metabolic remodelling in response to chronic hypoxia are complex and the subject of ongoing research work. However, a crossover point probably exists where carbohydrate fuel substrate utilization predominates over fatty acid utilization. This proposal is an extension of the ‘crossover concept’ suggested to occur under conditions of increasing exercise intensity (Brooks, 1998). The hypothesis advanced is that as exercise intensity increases (mild to moderate) it results in fuel substrate switching (or crossing over) from lipids to carbohydrates (Brooks & Mercier, 1994; Brooks, 1998). Moreover, a clear crossing-over point in fuel selection may be experimentally determined, taken as the power output at which energy from carbohydrate-derived fuels predominate over that derived from lipids (reviewed by Philp et al. 2005). In light of this, it is proposed here that a similar scenario may occur with increasing exposure times, or degrees of severity, to chronic hypoxia. This hypothesis should be relatively easy to investigate.

Putative regulatory steps directing fuel substrate switching in response to chronic hypoxia may include: attenuated sarcolemmal fatty acid uptake, reduced mitochondrial fatty acid uptake, or increased malonyl-CoA levels inhibiting carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), the rate-limiting enzyme of mitochondrial fatty acid transfer (reviewed by Philp et al. 2005). Interestingly, circulating lactate levels have also been implicated in this process. For example, increased arterial lactate content and consumption were reported for natives residing at high altitude (Moret, 1971/72). Furthermore, simultaneous uptake and release of myocardial lactate were found in response to hypoxia (Wisneski et al. 1985; Gertz et al. 1988; Mazer et al. 1990; Goodwin et al. 1998), probably occurring as a result of substrate partitioning via the ‘lactate shuttle’ (Brooks, 2002). Here, myocardial lactate metabolism is proposed to be compartmentalized with the mitochondrion regarded as the main site for exogenous lactate oxidation, while glycolytically derived lactate is more likely to be exported out of the cell (Chatham et al. 2001). In support, a mitochondrial lactate dehydrogenase and lactate transporter were identified in the heart (Brooks et al. 1999), providing a plausible mechanism for mitochondrial lactate oxidation.

Increased expression of lactate shuttle components was found in response to hypoxia (McClelland & Brooks, 2002; Ullah et al. 2006). For example, higher expression of the plasma membrane lactate transporter, monocarboxylate transporter MCT4 (mediating lactate efflux), was observed in response to in vitro and in vivo hypoxia (McClelland & Brooks, 2002; Ullah et al. 2006). Cardiac lactate dehydrogenase expression was also increased following chronic hypobaric hypoxia (McClelland & Brooks, 2002). However, the impact of these changes on mitochondrial lactate oxidation rates was not assessed. Greater flux through the lactate shuttle in response to chronic hypoxia would be expected to result in increased ATP generation (via mitochondrial lactate oxidation) and higher lactate efflux (via MCT4) to neighbouring tissues. Enhanced lactate efflux may be an adaptive measure to prevent accumulation of detrimental levels of lactate (lactic acidosis) within the myocardium or to distribute carbon potential to neighbouring cells (reviewed by Philp et al. 2005). Importantly, it may also play a role in regulating fuel substrate selection. In support, previous studies reported decreasing non-esterified fatty acid levels in response to increasing lactate levels (Corbett et al. 2004), implying that high circulating lactate content may have a direct inhibitory effect on lipolysis (Boyd et al. 1974; Issekutz et al. 1975). However, further studies are required to investigate myocardial lactate metabolism, the regulation of lactate shuttle components, and the underlying mechanisms governing the fuel substrate switch (fatty acids to carbohydrates) in response to moderate chronic hypoxia.

Chronic hypoxia and cardiac metabolic gene remodelling

Relatively few studies have examined the regulation of glucose metabolic genes in response to chronic hypobaric hypoxia. In vitro studies found that mammalian cells augment glycolytic capacity in response to hypoxia by increasing the expression of genes regulating glucose uptake and glycolysis (Semenza et al. 1994; Ebert et al. 1995; Semenza et al. 1996).

To gain further insight into hypoxia-mediated gene regulation, we measured temporal changes in glucose metabolic genes in response to moderate hypobaric hypoxia (Sharma et al. 2004; Adrogue et al. 2005). Here, the right and left ventricles were separately analysed due to differences in exposure to external stimuli, i.e. while both ventricles are exposed to hypoxia and neuroendocrine stimulation, only the right ventricle is challenged by increased load (pulmonary hypertension). We observed dynamic regulation of gene expression over the course of several weeks of exposure, with an early switch to a fetal expression pattern in both right and left ventricles (Sharma et al. 2004). Transcript levels of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK-4), an inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase and glucose oxidation, were reduced while expression of the cardiac-enriched glucose transporters, i.e. GLUT1 (fetal-enriched isoform) and GLUT4 (insulin-responsive adult isoform) was not altered. However, Sivitz et al. (1992) reported increased expression of GLUT1 and unchanged levels of GLUT4 for a similar hypobaric hypoxic exposure time. It is possible that these differences may be due to variation in hypobaric hypoxic experimental models employed. Although such changes in gene expression are usually reflected at the protein and enzyme activity levels (Barrie & Harris, 1976; Sivitz et al. 1992; Daneshrad et al. 2000), additional studies to determine the actual fuel substrate metabolism by the heart are required to further complete our understanding of these changes.

Reduced enzyme activity for β-hydroxy-acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (fatty acid β-oxidation enzyme) and CPT1 was found in response to chronic hypoxia (Daneshrad et al. 2000; Kennedy et al. 2001). Limited studies show that these findings are paralleled at the gene expression level. For example, we found that gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), a pivotal transcriptional modulator of numerous fatty acid metabolic genes, and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), a representative enzyme of fatty acid β-oxidation, were not rapidly altered in response to chronic hypoxic exposure (Sharma et al. 2004). However, PPARα and its target genes, CPT1 and MCAD, were down-regulated after 1 week's exposure to hypobaric hypoxia. Furthermore, in vivo cardiac MCAD gene promoter activity was reduced in parallel (Ngumbela et al. 2003). These data are in agreement with Razeghi et al. (2001) who showed decreased gene expression of PPARα and its target genes in two rat models of systemic hypoxia (cobalt chloride treatment and iso-volaemic dilution). The transcriptional profile of fatty acid metabolic genes in response to chronic hypoxia is therefore consistent with a fuel substrate switch that recapitulates the fetal pattern, i.e. decreased fatty acid and increased carbohydrate utilization.

Transcriptional regulatory mechanisms

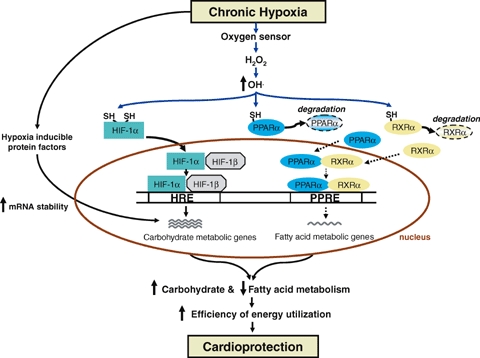

Delineation of transcriptional mechanisms orchestrating the regulation of metabolic genes has been largely investigated employing in vitro hypoxic experimental models. Previous studies highlighted the central role of the redox-sensitive transcriptional modulator, hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), in regulating the expression of numerous adaptive genes (Williams & Benjamin, 2000). Under normoxic conditions the HIF-1α isoform is hydroxylated by oxygen-dependent prolyl hydroxylases, thereafter ubiquitinylated and targeted for proteasomal degradation (Safran & Kaelin, 2003). However, hypoxia stabilizes HIF-1α allowing it to form a heterodimer with the constitutively expressed aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (also known as HIF-1β). HIF-1α–HIF-1β heterodimers bind to cis-acting hypoxia-response elements (HRE), including the core recognition sequence 5′-TACGTG-3′, to induce expression of target genes (Williams & Benjamin, 2000; Safran & Kaelin, 2003).

HIF-1 enhances glucose metabolism by inducing the expression of GLUT1 and several glycolytic genes (Ebert et al. 1995; Semenza et al. 1996; Wenger, 2002). Furthermore, it also induces the expression of non-metabolic targets, including genes regulating erythropoiesis (e.g. erythropoietin (EPO)) and angiogenesis (e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)) to increase oxygen carrying capacity of organisms in response to chronic hypoxia. In addition to HIF-1, other transcriptional regulators such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), activator protein-1, serum response factor, PPARα, retinoid X receptor α (RXRα), Nkx2.5, Sp1 and Sp3 have also been implicated in hypoxia-mediated transcriptional processes (Pahl & Baeuerle, 1994; Discher et al. 1998; Huss et al. 2001; Razeghi et al. 2001; Bar et al. 2003; Sharma et al. 2004). However, the role(s) of these factors in hypoxia-mediated gene transcription are not well understood at present and further studies are required to delineate precise modes of action.

How is the signal of altered  relayed to the transcriptional machinery to regulate gene expression? One potential mechanism may be via stabilization of mRNA under hypoxic conditions. The stability of mRNA determines its half-life and subsequent degradation, and is therefore an important factor regulating mRNA steady-state levels. For example, increased VEGF and GLUT1 expression observed during hypoxia may also be due to hypoxia-mediated mRNA stabilization, thereby increasing its half-life and preventing mRNA degradation that occurs under normoxic conditions (Dibbens et al. 1999; Paulding & Czyzyk-Krzeska, 2000). Hypoxia inducible protein factors forming complexes with canonical sequence motifs such as 5′-A(U)3-5A-3′ located within untranslated mRNA regions play a key role in mRNA stabilization.

relayed to the transcriptional machinery to regulate gene expression? One potential mechanism may be via stabilization of mRNA under hypoxic conditions. The stability of mRNA determines its half-life and subsequent degradation, and is therefore an important factor regulating mRNA steady-state levels. For example, increased VEGF and GLUT1 expression observed during hypoxia may also be due to hypoxia-mediated mRNA stabilization, thereby increasing its half-life and preventing mRNA degradation that occurs under normoxic conditions (Dibbens et al. 1999; Paulding & Czyzyk-Krzeska, 2000). Hypoxia inducible protein factors forming complexes with canonical sequence motifs such as 5′-A(U)3-5A-3′ located within untranslated mRNA regions play a key role in mRNA stabilization.

Another possibility is that higher, physiological ROS levels may act as secondary messengers to transduce extracellular signals to transcription factors. For example, increased mitochondrial ROS production may activate transcriptional regulators such as HIF-1 and NF-κB (Schreck et al. 1992; Chandel & Schumacker, 2000). How do altered ROS levels relay the signal to transcriptional modulators? It is likely that ROS directly regulate redox-sensitive transcription factors by altering the oxidation status of specific protein chemical groups, for e.g. cysteine residues (Michiels et al. 2002). H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) is an ideal candidate to transmit the primary signal from an oxygen sensor to the transcriptional machinery since it is non-charged, freely diffusible and its intracellular levels are tightly regulated (Kietzmann et al. 2000). The concept put forward is that high H2O2 levels under arterial  will increase OH• (hydroxy radical) formation via an iron-dependent Fenton reaction (H2O2+ Fe2+→ Fe3++ OH−+ OH•) (Kietzmann et al. 2000). Since OH• has an extremely short diffusion range this reaction is predicted to occur in close proximity to targeted transcription factors. Thus a highly specific signal would be transmitted, i.e. localized oxidation of sulfhydroxyl groups within target transcription factors. Conversely, lower

will increase OH• (hydroxy radical) formation via an iron-dependent Fenton reaction (H2O2+ Fe2+→ Fe3++ OH−+ OH•) (Kietzmann et al. 2000). Since OH• has an extremely short diffusion range this reaction is predicted to occur in close proximity to targeted transcription factors. Thus a highly specific signal would be transmitted, i.e. localized oxidation of sulfhydroxyl groups within target transcription factors. Conversely, lower  levels would reduce H2O2 levels, generating less OH• intermediates thereby resulting in transcription factors existing in a more reduced state. Physiological ROS may therefore modulate the redox status of transcriptional regulators to either increase or decrease its activity, thereby regulating the expression of target genes (Pahl & Baeuerle, 1994; Duranteau et al. 1998; Michiels et al. 2002).

levels would reduce H2O2 levels, generating less OH• intermediates thereby resulting in transcription factors existing in a more reduced state. Physiological ROS may therefore modulate the redox status of transcriptional regulators to either increase or decrease its activity, thereby regulating the expression of target genes (Pahl & Baeuerle, 1994; Duranteau et al. 1998; Michiels et al. 2002).

Less is known regarding transcription factors regulating fatty acid gene expression in response to chronic hypoxia. We found attenuated cardiac PPARα protein levels in mice exposed to chronic hypobaric hypoxia (Ngumbela et al. 2003). In agreement, others reported reduced myocardial expression of PPARα and target genes in response to hypoxia (Razeghi et al. 2001). PPARα heterodimerizes with its obligate partner RXR, subsequently binding to PPAR response elements (PPRE) located within promoter regions. PPREs usually consist of a direct repetition of the consensus sequence 5′-AGGTCA-3′ half site spaced by one or two nucleotides (reviewed by Marx et al. 2004). Reduced expression of RXRα was found in cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia (Huss et al. 2001). Moreover, binding of the PPARα–RXRα heterodimer to the mCPT1 gene promoter was reduced in parallel, consistent with a switch away from fatty acid metabolism. However, the mechanisms responsible for reduced PPARα and/or RXRα levels in response to hypoxia are not clear and further studies are needed to establish whether decreased synthesis or increased degradation of these transcription factors determine steady-state levels with hypoxia. mRNA stability and/or ROS signalling may also modulate the activity of these transcription factors. Indeed, repetitive ischaemia/reperfusion was associated with a ROS-dependent reduction of PPARα gene expression (Dewald et al. 2005).

Taken together, the proposal is made here (Fig. 2) that decreased  detected by oxygen sensors results in higher intracellular OH• intermediates. Subsequently, targeted transcription factors (e.g. HIF-1α, PPARα and RXRα) exist in a more reduced state. HIF-1α is thus stabilized allowing it to heterodimerize with HIF-1β, thereafter binding to HREs located within promoters regions of target genes. Expression of glucose metabolic genes may also be augmented by increased mRNA stability. On the contrary, PPARα and RXRα (in a reduced state) would be tagged for increased proteasomal degradation. This would result in decreased binding of the PPARα–RXRα heterodimer to PPREs, thereby reducing the expression of fatty acid metabolic genes. In support of the latter concept, we recently found increased transcript levels of ubiquitin proteasome regulators in response to hypobaric hypoxia (Razeghi et al. 2006).

detected by oxygen sensors results in higher intracellular OH• intermediates. Subsequently, targeted transcription factors (e.g. HIF-1α, PPARα and RXRα) exist in a more reduced state. HIF-1α is thus stabilized allowing it to heterodimerize with HIF-1β, thereafter binding to HREs located within promoters regions of target genes. Expression of glucose metabolic genes may also be augmented by increased mRNA stability. On the contrary, PPARα and RXRα (in a reduced state) would be tagged for increased proteasomal degradation. This would result in decreased binding of the PPARα–RXRα heterodimer to PPREs, thereby reducing the expression of fatty acid metabolic genes. In support of the latter concept, we recently found increased transcript levels of ubiquitin proteasome regulators in response to hypobaric hypoxia (Razeghi et al. 2006).

Figure 2.

Cardiac metabolic gene remodelling in response to chronic hypoxia It is proposed that ROS relay extracellular signals to the transcriptional machinery to initiate adaptive cardiac metabolic remodelling. HIF-1α (in reduced state) heterodimerizes with HIF-1β and subsequently binds to hypoxia-response elements (HRE) within the promoter region to increase expression of glucose metabolic genes. Hypoxia-mediated mRNA stabilization may also increase steady-state levels of glucose metabolic gene transcripts. Altered OH• levels are proposed to decrease PPARα and RXRα (in reduced state) by increased proteasomal degradation, leading to reduced binding to PPAR response elements (PPRE) within the promoter region and lower expression of fatty acid metabolic genes.

Collectively these studies demonstrate that cardiac metabolic remodelling (increased carbohydrate and decreased fatty acid utilization) in response to chronic hypoxia is coordinated at multiple levels as part of an adaptive response to ensure more oxygen-efficient fuel substrate utilization to help sustain cardiac output (Fig. 2). In addition to fuel substrate switching, however, hypoxia-mediated adaptive mechanisms also include the regulation of mitochondrial respiratory function.

Chronic hypoxia and mitochondrial respiratory function

Beyond the role as the energy powerhouse of the cell, mitochondria also act to integrate various signalling networks in response to biological stressors. This includes coordination of intracellular defence mechanisms to ensure the cell's survival when stressed, or if exceeded, translating stress signals into cell death. Numerous molecules (e.g. ROS, Ca2+) are regarded as important mediators of intramitochondrial physiological and pathophysiological signalling cascades (reviewed by Chandel & Budinger, 2007; Graier et al. 2007).

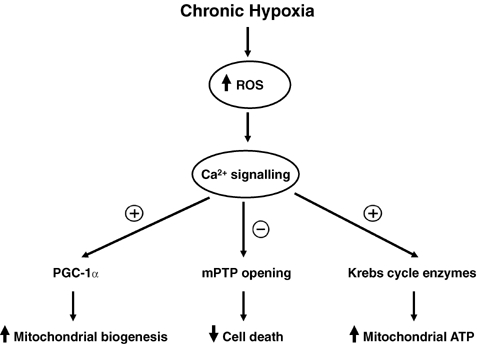

The mitochondrion is considered a source of ROS production (via complex I and/or complex III) under physiological conditions (Chandel & Schumacker, 2000). Physiological ROS may also regulate transcription of mitochondrial respiratory chain genes. Here the proposal is made that physiological ROS generated during moderate chronic hypoxia modulate Ca2+ signalling and transcriptional pathways, thereby augmenting cardiac mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity (Fig. 3). Activation of these pathways is also proposed to decrease cell death. This concept is supported by a recent study reporting increased H2O2 levels associated with enhanced gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis (Hashimoto et al. 2007). Moreover, Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) expression was elevated in parallel supporting a link between ROS production and intracellular Ca2+ signalling. In agreement, genetically manipulated mice expressing the constitutively active form of CaMKIV displayed augmented mitochondrial biogenesis and increased PGC-1α expression (Wu et al. 2002). Additional investigations are required, however, to determine whether physiological ROS can induce PGC-1α expression independently of Ca2+ signalling cascades, and to further elucidate the role of other transcriptional modulators also implicated in this process (e.g. nuclear respiratory factors, mitochondrial transcription factor A) (reviewed by Ojuka, 2004).

Figure 3.

Mitochondria integrate signalling cascades and transcriptional circuits in response to chronic hypoxia It is proposed that physiological ROS generated during moderate chronic hypoxia modulate Ca2+ signalling and transcriptional pathways to enhance cardioprotection in response to severe biological stress. Firstly, ROS activate Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) to increase expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α (PGC-1α), a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Secondly, co-localization between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum facilitates mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, thereby accelerating enzyme activities of Krebs cycle dehydrogenases. Thirdly, moderate chronic hypoxia enhances tolerance of myocardial mitochondria to Ca2+ overload, thereby lowering the probability of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening. Together these steps are proposed to enhance mitochondrial energy production and attenuate cell death in the heart when challenged by stress for, for example, severe oxygen deprivation.

Proliferation of smaller mitochondria was found in response to chronic hypobaric hypoxia, suggested to form part of an adaptive process to increase mitochondrial oxygen uptake by enhancing the mitochondrial surface-to-volume ratio (Friedman et al. 1973). Previous studies reported sustained and/or increased mitochondrial respiratory function and ATP synthesis in animals exposed to mild chronic hypoxia (Costa et al. 1988; Reynafarje & Marticorena, 2002; Essop et al. 2004). Enhanced activities of respiratory enzymes and coenzymes were also found in response to high altitude or experiments simulating this condition (Moret, 1971/72; Hochachka et al. 1982). Mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling may play an important role in this process. Co-localization between mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum facilitates mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, allowing it to accelerate enzyme activities of Krebs cycle dehydrogenases (reviewed by Graier et al. 2007). Calcium-mediated activation of Krebs cycle enzymes would therefore be expected to augment mitochondrial ATP production after exposure to moderate chronic hypoxia (Fig. 3). The production of high energy phosphates may also contribute to greater mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity in response to chronic hypoxia. For example, hearts exposed to high altitude displayed increased levels of high energy phosphate compounds in response to coronary artery ligation (Opie et al. 1978). Also, higher rates of myocardial phosphocreatine synthesis (Novel-Chate et al. 1995) and cardiac ATPase activity (Tappan et al. 1957) were reported in response to chronic hypoxia.

Reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity was, however, also observed after exposure to hypobaric hypoxia (Green et al. 1989; Nouette-Gaulain et al. 2005). For example, Green et al. (1989) determined that muscle oxidative potential was lower in human subjects exposed to increasing levels of hypobaric hypoxia. This decline was noted only under extreme hypobaric hypoxic conditions. Moreover, reduced myocardial mitochondrial mass was found under severe hypoxic conditions (Cervos-Navarro et al. 1999). The precise reasons for attenuated mitochondrial respiratory function in response to severe hypoxia are unclear at present. However, Hochachka & Lutz (2001) proposed that suppression of ATP demand and supply pathways under severe hypoxic conditions allows ATP levels to remain constant, even while ATP turnover rates greatly decline. Several ATP-dependent processes (e.g. protein synthesis and ion pumping) are down-regulated accordingly (Hochachka & Lutz, 2001). These studies therefore emphasize how varying degrees of hypoxic exposure (moderate versus severe) may result in distinct mitochondrial functional phenotypes.

An emerging paradigm suggests that moderate chronic hypoxia prevents Ca2+ overload and apoptosis, thus enhancing cardioprotection (Fig. 3). It is well-known that calcium overload due to abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis results in damaging intracellular effects such as cell death (Halestrap, 2006). For example, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), a non-specific pore located within the inner mitochondrial membrane, occurs under conditions of Ca2+ overload (Halestrap et al. 1998). Prolonged mPTP opening leads to decreased mitochondrial ATP generation and initiation of the apoptotic cascade (reviewed by Essop & Opie, 2004). However, cardiac mitochondria pre-exposed to chronic intermittent hypoxia display reduced mPTP opening (Zhu et al. 2006). Moreover, these authors demonstrated that hypobaric hypoxia enhances the resilience of heart mitochondria to Ca2+ overload, thereby lowering the probability of mPTP opening. Also, Chen et al. (2006) found that pre-exposure to chronic intermittent hypoxia preserved myocardial Ca2+ homeostasis and contraction in response to severe oxygen deprivation. Whether this process occurs in a ROS-dependent manner requires further investigation.

Protein signalling networks are likely to also play a role in this process. For example, activation of CaMKII is suggested as a potential mechanism by which chronic intermittent hypoxia protects the heart against the Ca2+ overload injury (Xie et al. 2004). Other studies demonstrated activation of protein kinase C (PKC) in the heart after exposure to chronic hypoxia (reviewed by Ostadal & Kolar, 2007). Since the cardioprotective PKCɛ isoform is associated with the mPTP, it is a likely candidate to reduce mPTP opening in response to chronic hypoxia. We recently reported that PKCɛ preserved cardiac mitochondrial function via maintenance of mPTP components in response to severe oxygen deprivation (McCarthy et al. 2005). Furthermore, PKCɛ overexpressing mice exposed to chronic hypobaric hypoxia exhibited increased mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity associated with sustained cardiac contractile function (McCarthy, 2006). These studies strongly implicate the mitochondrion in hypoxia-mediated cardioprotection, i.e. integrating multiple signalling pathways and transcriptional circuits to enhance energy production and diminish cell death in response to severe biological stress. It is important to note here that mitochondrial signalling networks and regulators mediating these and other cardioprotective processes are complex and include several molecular and biochemical modulators (e.g. nitric oxide, mitochondrial KATP channels, antioxidant defences) not discussed in this review article (refer to reviews by Lynn et al. 2007; Zaobornyj et al. 2007).

Summary

This review highlights the adaptive role of cardiac metabolic remodelling in response to chronic hypoxia. We hypothesize that moderate chronic hypobaric hypoxia activates regulatory pathways that mediate long-term cardiac metabolic remodelling, particularly at the transcriptional level. The proposal is that physiological ROS plays a central role, modulating the activity of redox-sensitive transcription factors to induce a fetal gene programme (increased carbohydrate and decreased fatty acid metabolism) and increased mitochondrial biogenesis in the heart. It is suggested that together these programmes will increase the efficiency of energy production and augment mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity to sustain cardiac contractile function despite hypoxia. Therefore, investigations to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying hypoxia-mediated cardioprotection may unlock novel therapeutic interventions that may help to reduce the growing burden of heart disease.

Acknowledgments

I thank MRC and NRF for financial support, Dr Lionel Opie for helpful comments, Miss Anna Chan and Mrs Tasneem Adam for assisting with preparation of this manuscript.

References

- Acker T, Fandrey J, Acker H. The good, the bad and the ugly in oxygen-sensing: ROS, cytochromes and prolyl-hydroxylases. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrogue JV, Sharma S, Ngumbela K, Essop MF, Taegtmeyer H. Acclimatization to chronic hypobaric hypoxia is associated with a differential transcriptional profile between the right and left ventricle. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;278:71–78. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-6629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Stella J, Saldana M. The muscular pulmonary arteries in people native to high altitude. Med Thorac. 1962;19:484–493. doi: 10.1159/000192256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asemu G, Papousek F, Ostadal B, Kolar F. Adaptation to high altitude hypoxia protects the rat heart against ischemia-induced arrhythmias. Involvement of mitochondrial KATP channel. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1821–1831. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar H, Kreuzer J, Cojoc A, Jahn L. Upregulation of embryonic transcription factors in right ventricular hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2003;98:285–294. doi: 10.1007/s00395-003-0410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrie SE, Harris P. Effects of chronic hypoxia and dietary restriction on myocardial enzyme activities. Am J Physiol. 1976;231:1308–1313. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.4.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm EA, Jones BE, Radda GK, Veech RL, Clarke K. Increased uncoupling proteins and decreased efficiency in palmitate-perfused hyperthyroid rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H977–H983. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.3.H977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouche C, Serdy S, Kahn CR, Goldfine AB. The cellular fate of glucose and its relevance in type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:807–830. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd AE, 3rd, Giamber SR, Mager M, Lebovitz HE. Lactate inhibition of lipolysis in exercising man. Metabolism. 1974;23:531–542. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(74)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks GA. Mammalian fuel utilization during sustained exercise. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;120:89–107. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(98)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks GA. Lactate shuttles in nature. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:258–264. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks GA, Dubouchaud H, Brown M, Sicurello JP, Butz CE. Role of mitochondrial lactate dehydrogenase and lactate oxidation in the intracellular lactate shuttle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1129–1134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks GA, Mercier J. Balance of carbohydrate and lipid utilization during exercise: the ‘crossover’ concept. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:2253–2261. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.6.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budev MM, Arroliga AC, Wiedemann HP, Matthay RA. Cor pulmonale: an overview. Semin Respir Crit Care Medical. 2003;24:233–244. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervos-Navarro J, Kunas RC, Sampaolo S, Mansmann U. Heart mitochondria in rats submitted to chronic hypoxia. Histol Histopathol. 1999;14:1045–1052. doi: 10.14670/HH-14.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Budinger GRS. The cellular basis for diverse responses to oxygen. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel NS, Schumacker PT. Cellular oxygen sensing by mitochondria: old questions, new insight. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1880–1889. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatham JC, Des Rosiers C, Forder JR. Evidence of separate pathways for lactate uptake and release by the perfused rat heart. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281:E794–E802. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.4.E794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Lu XY, Li J, Fu JD, Zhou ZN, Yang HT. Intermittent hypoxia protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced alterations in Ca2+ homeostasis and contraction via the sarcoplasmic reticulum and Na+/Ca2+ exchange mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1221–C1229. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00526.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett J, Fallowfield JL, Sale C, Harris RC. Relationship between plasma lactate concentration and fat oxidation. Proceedings of the 9th Annu Congr Eur Coll Sports Sci. 2004. p. P172.

- Costa LE, Boveris A, Koch OR, Taquini AC. Liver and heart mitochondria in rats submitted to chronic hypobaric hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1988;255:C123–C129. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1988.255.1.C123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneshrad Z, Garcia-Riera MP, Verdys M, Rossi A. Differential responses to chronic hypoxia and dietary restriction of aerobic capacity and enzyme levels in the rat myocardium. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;210:159–166. doi: 10.1023/a:1007137909171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewald O, Sharma S, Adrogue J, Salazar R, Duerr GD, Crapo JD, Entman ML, Taegtmeyer H. Downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha gene expression in a mouse model of ischemic cardiomyopathy is dependent on reactive oxygen species and prevents lipotoxicity. Circulation. 2005;112:407–415. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.536318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibbens JA, Miller DL, Damert A, Risau W, Vadas MA, Goodall GJ. Hypoxic regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA stability requires the cooperation of multiple RNA elements. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:907–919. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Discher DJ, Bishopric NH, Wu X, Peterson CA, Webster KA. Hypoxia regulates β-enolase and pyruvate kinase-M promoters by modulating Sp1/Sp3 binding to a conserved GC element. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26087–26093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.26087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duranteau J, Chandel NS, Kulisz A, Shao Z, Schumacker PT. Intracellular signaling by reactive oxygen species during hypoxia in cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11619–11624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert BL, Firth JD, Ratcliffe PJ. Hypoxia and mitochondrial inhibitors regulate expression of glucose transporter 1 via distinct cis-acting sequences. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29083–29089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essop MF, Opie LH. Metabolic therapy for heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1765–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essop MF, Razeghi P, McLeod C, Young ME, Taegtmeyer H, Sack MN. Hypoxia-induced decrease of UCP3 gene expression in rat heart parallels metabolic gene switching but fails to affect mitochondrial respiratory coupling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:561–564. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman I, Moravec J, Reichart E, Hatt PY. Subacute myocardial hypoxia in the rat. An electron microscopic study of the left ventricular myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1973;5:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(73)90045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz EW, Wisneski JA, Stanley WC, Neese RA. Myocardial substrate utilization during exercise in humans. Dual carbon-labeled carbohydrate isotope experiments. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:2017–2025. doi: 10.1172/JCI113822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin GW, Taylor CS, Taegtmeyer H. Regulation of energy metabolism of the heart during acute increase in heart work. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29530–29539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graier WF, Frieden M, Malli R. Pflugers Arch. 2007. Mitochondria and Ca2+ signaling: old guests, new functions. DOI: 10.1007/s00424-007-0296-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green HJ, Sutton JR, Cymerman A, Young PM, Houston CS. Operation Everest II: adaptations in human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:2454–2461. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.5.2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grifka RG. Cyanotic congenital heart disease with increased pulmonary blood flow. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:405–425. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap AP. Calcium, mitochondria and reperfusion injury: a pore way to die. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:232–237. doi: 10.1042/BST20060232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halestrap AP, Kerr PM, Javadov S, Woodfield KY. Elucidating the molecular mechanism of the permeability transition pore and its role in reperfusion injury of the heart. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1366:79–94. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T, Hussien R, Oommen S, Gohil K, Brooks GA. Lactate sensitive transcription factor network in L6 cells: activation of MCT1 and mitochondrial biogenesis. FASEB J. 2007;21:2602–2612. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8174com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hislop A, Reid L. New findings in pulmonary arteries of rats with hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Br J Exp Pathol. 1976;57:542–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka P. Mechanism and evolution of hypoxia-tolerance in humans. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:1243–1254. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Clark CM, Holden JE, Stanley C, Ugurbil K, Menon RS. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the Sherpa heart: a phosphocreatine/adenosine triphosphate signature of metabolic defense against hypobaric hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1215–1220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Lutz PL. Mechanism, origin, and evolution of anoxia tolerance in animals. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;130:435–459. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Stanley C, Sumar-Kalnuwski J. Metabolic meaning of elevated levels of oxidative enzymes in high altitude animals: an interpretive hypothesis. Respir Physiol. 1982;52:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(83)90087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden JE, Stone CK, Clark CM, Brown WD, Nickles RJ, Stanley C, Hochachka PW. Enhanced cardiac metabolism of plasma glucose in high-altitude natives: adaptation against chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:222–228. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurford WE, Crosby G, Strauss HW, Jones R, Lowenstein E. Ventricular performance and glucose uptake in rats during chronic hypobaric hypoxia. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1344–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado A. Some clinical aspects of life at high altitudes. Ann Intern Med. 1960;53:247–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-53-2-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huss JM, Levy FH, Kelly DP. Hypoxia inhibits the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/retinoid X receptor gene regulatory pathway in cardiac myocytes: a mechanism for O2-dependent modulation of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27605–27612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issekutz B, Jr, Shaw WA, Issekutz TB. Effect of lactate on FFA and glycerol turnover in resting and exercising dogs. J Appl Physiol. 1975;39:349–353. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SL, Stanley WC, Panchal AR, Mazzeo RS. Alterations in enzymes involved in fat metabolism after acute and chronic altitude exposure. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:17–22. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kietzmann T, Fandrey J, Acker H. Oxygen radicals as messengers in oxygen-dependent gene expression. News Physiol Sci. 2000;15:202–208. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.4.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Kuppusamy P, Sham JS, Shimoda LA, Zweier JL, Sylvester JT. Increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by pulmonary arterial smooth muscle is required for hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:A395. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn EG, Lu Z, Minerbi D, Sack MN. The regulation, control, and consequences of mitochondrial oxygen utilization and disposition in the heart and skeletal muscle during hypoxia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1353–1362. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2006. PKCε and cardioprotection: an exploration of putative mechanisms. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J, McLeod CJ, Minners J, Essop MF, Ping P, Sack MN. PKCε activation augments cardiac mitochondrial respiratory post-anoxic reserve – a putative mechanism in PKCε cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:697–700. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GB, Brooks GA. Changes in MCT 1, MCT 4, and LDH expression are tissue specific in rats after long-term hypobaric hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:1573–1584. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01069.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx N, Duez H, Fruchart J-C, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and atherogenesis: regulators of gene expression in vascular cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:1168–1178. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000127122.22685.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazer CD, Stanley WC, Hickey RF, Neese RA, Cason BA, Demas KA, Wisneski JA, Gertz EW. Myocardial metabolism during hypoxia: maintained lactate oxidation during increased glycolysis. Metabolism. 1990;39:913–918. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerson FZ. Essentials of Adaptive Medicine: Protective Effects of Adaptation (A Manual) Geneva: Hypoxia Medical Ltd; [Google Scholar]

- Meerson FZ, Gomzakov OA, Shimkovich MV. Adaptation to high altitude hypoxia as a factor preventing development of myocardial ischemic necrosis. Am J Cardiol. 1973;31:30–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(73)90806-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerson FZ, Ustinova EE, Orlova EH. Prevention and elimination of heart arrhythmias by adaptation to intermittent high altitude hypoxia. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:783–789. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960101202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michiels C, Minet E, Mottet D, Raes M. Regulation of gene expression by oxygen: NF-κB and HIF-1, two extremes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1231–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moret PR. Myocardial metabolic changes in chronic hypoxia. Cardiol. 1971/72;56:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer EA, Jr, Monson RR, MacMahon B. Reduction in mortality from coronary heart disease in men residing at high altitude. N Engl J Med. 1977;296:581–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197703172961101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch CE, Zhang M, Cave AC, Shah AM. NADPH oxidase-dependent redox signalling in cardiac hypertrophy, remodelling and failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngumbela KC, Sack MN, Essop MF. Counter-regulatory effects of incremental hypoxia on the transcription of a cardiac fatty acid oxidation enzyme-encoding gene. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;250:151–158. doi: 10.1023/a:1024921329885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouette-Gaulain K, Malgat M, Rocher C, Savineau JP, Marthan R, Mazat JP, Sztark F. Time course of differential mitochondrial energy metabolism adaptation to chronic hypoxia in right and left ventricles. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novel-Chate V, Aussedat J, Saks VA, Rossi A. Adaptation to chronic hypoxia alters cardiac metabolic response to beta stimulation: novel face of phosphocreatine overshoot phenomenon. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:1679–1687. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(95)90755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojuka EO. Role of calcium and AMP kinase in the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and GLUT4 levels in muscle. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:275–278. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie LH. Metabolism of the heart in health and disease. II. Am Heart J. 1969;77:100–122. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(69)90135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie LH, Duchosal F, Moret P. Effects of increased left ventricular work, hypoxia, or coronary ligation on hearts from rats at high altitude. Eur J Clin Invest. 1978;8:309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1978.tb00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostadal B, Kolar F. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007. Cardiac adaptation to chronic high-altitude hypoxia: beneficial and adverse effects. DOI: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostadal B, Ostadalova I, Dhalla NS. Development of cardiac sensitivity to O2 deficiency: comparative and ontogenetic aspects. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:635–659. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl HL, Baeuerle PA. Oxygen and the control of gene expression. Bioessays. 1994;16:497–502. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulding WR, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF. Hypoxia-induced regulation of mRNA stability. In: Lahiri S, Prabhakar NR, Forster RE II, editors. Oxygen Sensing: Molecule to Man. the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Philp A, Macdonald AL, Watt PW. Lactate – a signal coordinating cell and systemic function. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:4561–4575. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razeghi P, Baskin KK, Sharma S, Young ME, Stepkowski S, Essop MF, Taegtmeyer H. Atrophy, hypertrophy, and hypoxemia induce transcriptional regulators of the ubiquitin proteasome system in the rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razeghi P, Young ME, Abbasi S, Taegtmeyer H. Hypoxia in vivo decreases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-regulated gene expression in rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:5–10. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regensteiner JG, Moore LG. Migration of the elderly from high altitudes in Colorado. JAMA. 1985;253:3124–3128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer KA, Jennings RB. Myocardial ischemia, hypoxia, and infarction. In: Fozzard HA, et al., editors. The Heart and Cardiovascular System. 2. New York: Raven Press Ltd; 1992. Chap. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Reynafarje BD, Marticorena E. Bioenergetics of the heart at high altitude: environmental hypoxia imposes profound transformations on the myocardial process of ATP synthesis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2002;34:407–412. doi: 10.1023/a:1022597523483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, Reeves JT, Butterfield GE, Mazzeo RS, Sutton JR, Wolfel EE, Brooks GA. Altitude and β-blockade augment glucose utilization during submaximal exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1996;80:605–615. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran M, Kaelin WG., Jr HIF hydroxylation and the mammalian oxygen-sensing pathway. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:779–783. doi: 10.1172/JCI18181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck R, Albermann K, Baeuerle PA. Nuclear factor κ B: an oxidative stress-responsive transcription factor of eukaryotic cells (a review) Free Radic Res Commun. 1992;17:221–237. doi: 10.3109/10715769209079515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Perspectives on oxygen sensing. Cell. 1999;98:281–284. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81957-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL, Jiang BH, Leung SW, Passantino R, Concordet JP, Maire P, Giallongo A. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32529–32537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL, Roth PH, Fang HM, Wang GL. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23757–23763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AM, Sauer H. Transmitting biological information using oxygen: reactive oxygen species as signalling molecules in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Taegtmeyer H, Adrogue J, Razeghi P, Sen S, Ngumbela K, Essop MF. Dynamic changes of gene expression in hypoxia-induced right ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1185–H1192. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00916.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivitz WI, Lund DD, Yorek B, Grover-McKay M, Schmid PG. Pretranslational regulation of two cardiac glucose transporters in rats exposed to hypobaric hypoxia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1992;263:E562–E569. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.263.3.E562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaini G, Harris DA. Biochemical dysfunction in heart mitochondria exposed to ischaemia and reperfusion. Biochem J. 2005;390:377–394. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley WC, Recchia FA, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial substrate metabolism in the normal and failing heart. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1093–1129. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima M, Katayose D, Bessho M, Isoyama S. Acute ischaemic preconditioning and chronic hypoxia independently increase myocardial tolerance to ischaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:312–319. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappan DV, Reynafarje B, Potter VR, Hurtado A. Alterations in enzymes and metabolites resulting from adaptation to low oxygen tensions. Am J Physiol. 1957;190:93–98. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1957.190.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turek Z, Kubat K, Ringnalda BE, Kreuzer F. Experimental myocardial infarction in rats acclimated to simulated high altitude. Basic Res Cardiol. 1980;75:544–554. doi: 10.1007/BF01907836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah MS, Davies AJ, Halestrap AP. The plasma membrane lactate transporter MCT4, but not MCT1, is up-regulated by hypoxia through a HIF-1α-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9030–9037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511397200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Euler US, Liljestrand G. Observation on the pulmonary arterial blood pressure in the cat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1946;12:301–320. [Google Scholar]

- Voors AW, Johnson WD. Altitude and arteriosclerotic heart disease mortality in white residents of 99 of the 100 largest cities in the United States. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger RH. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia: O2-sensing protein hydroxylases, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, and O2-regulated gene expression. FASEB J. 2002;16:1151–1162. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0944rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RS, Benjamin IJ. Protective responses in the ischemic myocardium. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:813–818. doi: 10.1172/JCI11205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisneski JA, Gertz EW, Neese RA, Gruenke LD, Morris DL, Craig JC. Metabolic fate of extracted glucose in normal human myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1819–1827. doi: 10.1172/JCI112174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtczak L, Wieckowski MR. The mechanisms of fatty acid-induced proton permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1999;31:447–455. doi: 10.1023/a:1005444322823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Kanatous SB, Thurmond FA, Gallardo T, Isotani E, Bassel-Duby R, Williams RS. Regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle by CaMK. Science. 2002;296:349–352. doi: 10.1126/science.1071163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Zhu WZ, Zhu Y, Chen L, Zhou ZN, Yang HT. Intermittent high altitude hypoxia protects the heart against lethal Ca2+ overload injury. Life Sci. 2004;76:559–572. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaobornyj T, Gonzales GF, Valdez LB. Mitochondrial contribution to the molecular mechanism of heart acclimatization to chronic hypoxia: role of nitric oxide. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1247–1259. doi: 10.2741/2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu WZ, Xie Y, Chen L, Yang HT, Zhou ZN. Intermittent high altitude hypoxia inhibits opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores against reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]