Abstract

Angiogenesis, which is essential for the physiological adaptation of skeletal muscle to exercise, occurs in response to the mechanical forces of elevated capillary shear stress and cell stretch. Increased production of VEGF is a characteristic of endothelial cells undergoing either stretch- or shear-stress-induced angiogenesis. Because VEGF production is regulated by hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs), we examined whether HIFs play a significant role in the angiogenic process initiated by these mechanical forces. Rat extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles were overloaded to induce stretch, or exposed to the dilator prazosin to elevate capillary shear stress, and capillaries from these muscles were isolated by laser capture microdissection for RNA analysis. HIF-1α and HIF-2α transcript levels increased after 4 and 7 days of stretch, whereas a transient early induction of HIF-1α and HIF-2α transcripts was detected in capillaries from prazosin-treated muscles. Skeletal muscle microvascular endothelial cells exposed to 10% stretch in vitro showed an elevation in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA, which was preceded by increases in HIF-binding activity. Conversely, HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA were reduced significantly, and HIF-α proteins were undetectable, after 24 h exposure to elevated shear stress (16 dyn cm−2 (16 ×10−5 N cm−2). Given the disparate regulation of HIFs in response to these mechanical stimuli, we tested the requirement of HIF-α proteins in stretch- and shear-stress-induced angiogenesis by impeding HIF accumulation through use of the geldanamycin derivative 17-DMAG. Treatment with 17-DMAG significantly impaired stretch-induced, but not shear-stress-induced, angiogenesis. Together, these results illustrate that activation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α contributes significantly to stretch- but not to shear-stress-induced capillary growth.

Capillary growth in adult tissues is regulated stringently by cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, and by levels of locally released angiogenic/angiostatic molecules. Angiogenesis is known to be triggered by exposure of endothelial cells to a local hypoxic or inflammatory environment (Ausprunk & Folkman, 1977; Pepper, 1997; Folkman, 2003). Endothelial cells also are exposed recurrently to extracellular mechanical stimuli such as shear stress and stretch/strain, which they transduce into intracellular signalling cascades that generate numerous cellular responses (Davies, 1995; Lehoux & Tedgui, 1998; Ingber, 2006; Chien, 2007). Sensitivity to the local haemodynamic environment facilitates assembly of appropriate microvascular network structures during development, and may continue to be critical in maintaining and modifying capillary networks in adulthood (Hudetz & Kiani, 1992; Pries et al. 2001; Dor et al. 2003). Capillary network remodelling, which is essential for the physiological adaptation of muscle to exercise, occurs in response to the mechanical forces of increased shear stress and cell stretch (Hudlicka et al. 1992; Prior et al. 2004).

While a substantial body of research has defined the initial activation of endothelial cells by mechanical stimuli, the pathways through which these mechanical forces lead to the induction of angiogenesis within quiescent capillaries have not been established. Hypoxia inducible factors (HIF-1 and -2) regulate the transcription of genes involved in cellular survival and angiogenesis (e.g. GLUT1, EPO1, PDGFB, VEGF-A and VEGFR1) (Ema et al. 1997; Semenza, 1998; Harris, 2002). In normoxia, both HIF-1α and -2α proteins are subject to rapid degradation, which is regulated at the post-translational level by Von Hippel-Lindau protein (Semenza, 2001; Brahimi-Horn et al. 2005). Despite similarities in hypoxia-mediated induction and proteasomal-mediated degradation pathways, HIF-1α and HIF-2α have distinct effects on gene expression and cell migration (Raval et al. 2005). Some target genes, for example VEGF-A, are induced by both HIF-α isoforms, while others are preferentially activated by one or the other (Ema et al. 1997; Hu et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2005). While HIF-1α has a broad pattern tissue distribution, HIF-2α is expressed mainly in endothelial cells, where it enhances the transcription of endothelial-specific genes related to angiogenesis and vessel maturation (e.g. VEGFR1, VEGFR2, Tie2, angiopoietin-1) (Ema et al. 1997; Hu et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2005). Recent studies demonstrated that HIF-1α expression is modulated by mechanical forces in addition to the well-recognized stimulus of low oxygen tension (Richard et al. 2000; Kim et al. 2002; Kakinuma et al. 2005). Consistent with those findings, we reported that endothelial cell VEGF-A levels increase in response to changes in microvascular shear stress and to muscle stretch (Milkiewicz et al. 2001, 2007; Rivilis et al. 2002). Because of the established role of HIF proteins in transcriptional regulation of VEGF-A and the previous reports of stretch-induced upregulation of HIF-1α in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle, we examined whether endothelial HIF-1α, and related family member HIF-2α, are induced by mechanical stretch and shear stress within skeletal muscle, and if these transcription factors play significant roles in the processes of capillary growth initiated by mechanical stimuli.

Methods

Ethical approval

Animal studies were approved by the York University Committee on Animal Care, and performed in accordance with Animal Care Procedures at York University and the American Physiological Society's Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals.

Rat studies

Male Sprague Dawley rats (200–250 g; Charles River Laboratories, Quebec, Canada) were used for all experiments. Rats (n = 12) were subject to sustained stretch of the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscle by unilateral extirpation of the agonist muscle tibialis anterior (Egginton et al. 1998). Rats (n = 12) were subject to chronic vasodilatation of skeletal muscle vasculature using the α1 adrenergic antagonist prazosin hydrochloride (50 mg l−1 in drinking water; Sigma Aldrich; Dawson & Hudlicka, 1989). Surgical procedures were carried out under anaesthesia (intraperitoneal injection of ketamine, 80 mg kg−1; and xylazine, 10 mg kg−1). Untreated rats (n = 4) were used as controls. In a second study, rats (n = 24) were treated with the Hsp90 inhibitor, 17-DMAG (NSC 707545; 17-demethoxy-17-[[(2-dimethylamino)ethyl]amino]geldanamycin), which was provided by the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch, National Cancer Institute, USA. Either 17-DMAG (12.5 mg ml−1 in 5% sterile dextrose), or 5% sterile dextrose alone, was delivered to EDL by means of Alzet osmotic pumps (Model 2002; delivery rate 0.5 μl h−1 for 14 days; Duret Corporation), which were implanted subcutaneously in the upper thigh region of one hindleg. Rats then were subjected to stretch or dilator protocols. Post-surgery, all rats received a single dose of butorphanol (1 mg kg−1, subcutaneous) and received food and water ad libitum. Upon completion of each treatment time course, rats were anaesthetized (intraperitoneal injection of ketamine 80 mg kg−1, and xylazine 10 mg kg−1) and EDL muscles were removed for further analysis. Animals were killed by cardiac puncture while under anaesthesia.

Immunohistochemistry

Muscle vascularity was evaluated by determination of the capillary-to-fibre ratio (C:F) within alkaline-phosphatase-stained frozen sections (five independent fields of view per muscle, and four rats per condition). Immunostaining was performed as described earlier (Milkiewicz et al. 2004), using mouse HIF-1α or rabbit HIF-2α antibodies (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) and detection with Alexa-586-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Canada). Sections were viewed using an Olympus confocal microscope or a Zeiss inverted microscope (M200; Carl Zeiss, Germany) using an oil immersion ×40 objective, Lambda 10-2 filter changer (Sutter Instruments) and a cooled digital CCD camera (Quantix57; Photometrics), which were controlled using MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging). Image exposure settings were identical for all images captured. Average pixel intensity within a defined region of each image was calculated using MetaMorph software, from a minimum of five independent images for each condition. Mean pixel intensities (± s.e.m.) were calculated.

Laser capture microdissection, RNA isolation and cDNA production

Muscle capillaries were isolated using the PixCell II laser capture microdissection system (Arcturus Bioscience, Mountain View, CA, USA) with a laser beam diameter of 7.5 μm). Cell lysis, RNA purification (PicoPure RNA Isolation; Arcturus Bioscience, USA) and cDNA synthesis of this capillary-enriched population were conducted as previously described (Milkiewicz & Haas, 2005)

Cell culture and cDNA production

Skeletal muscle microvascular endothelial cells (SMEC) were isolated from EDL muscles of male Sprague Dawley rats (200–250 g, n = 10) using the anaesthesia and euthanasia protocols outlined above, and cultured under standard growth conditions up to 10 passages (Han et al. 2003). For stretch experiments, SMEC were exposed to 10% static stretch (0.5, 2, 6 and 24 h) using a Flexcell strain unit (FX-4000 Tension Plus; Flexcell International, Hillsborough, NC, USA) (Milkiewicz et al. 2007). Controls were plated on Bioflex plates for equivalent times but not subjected to stretch. For inhibition studies, cells were pretreated with U0126 (0.3 μm), PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μm) or VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor I (VRI, 10 μm; (Z)-3-[(2,4-dimethyl-3-(ethoxycarbonyl)pyrrol-5-yl)methylidenyl]indolin-2-one]; Calbiochem no. 676480) for 30 min (VRI) or 2 h (U0126 and LY294002) prior to initiation of stretch. For shear-stress experiments, cells were plated onto glass coverslips, mounted in two parallel laminar flow chambers (FCS2; Bioptechs, Butler, PA, USA) and exposed to flow (16 dyn cm−2 (16 ×10−5 N cm−2)) for 0.5–24 h, as previously described (Milkiewicz et al. 2006). Cells plated on coverslips and not subjected to fluid flow served as static controls. Cells were pretreated with drugs at final concentrations of 30 μm for l-NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA), or 0.3 μm for U0126. First-strand cDNA were produced using Cells-to-cDNA (Ambion). For in vitro testing of 17-DMAG, cells were plated on collagen-coated dishes, and exposed for 20 h to cobalt chloride (0.1 mm), 17-DMAG (3 μm) or cobalt chloride + 17-DMAG, followed by lysis and immunoblotting for HIF-1α and HIF-2α. In some experiments, cells were treated with clioquinol (100 μm) to inhibit the asparaginyl hydroxylase activity of factor-inhibiting HIF (FIH-1) for 6 h prior to lysis for RNA analysis. This treatment was demonstrated to stabilize transcriptionally competent HIF-1α in a variety of cell types (Choi et al. 2006).

Real-time RT-PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR (q-PCR) assays for HIF-1α, HIF-2α, VEGF and control ribosomal RNA transcripts were carried out using gene-specific TaqMan FAM- or VIC-labelled probes obtained from Applied Biosystems (HIF-1α, Rn00577560_m1; HIF-2α, Mm00438717_m1; VEGF-A, Rn00582935_m1; 18S rRNA, P/N4308329). Real-time PCR analysis was conducted using a ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, USA) as previously described (Milkiewicz & Haas, 2005).

Immunoblotting

Proteins isolated from cultured SMEC or from muscle homogenates (10–125 μg) were analysed by Western blotting using conventional procedures. Primary antibodies were as follows: rabbit anti-VEGF-A (Santa Cruz); rabbit anti-phospho ERK1/2, anti-ERK1/2, anti-phospho-Akt, anti-β-actin, or anti-tubulin (Cell Signalling); mouse anti-HIF-1α or rabbit anti-HIF-2α (Novus Biologicals). Bands were quantified using Fluorchem software (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA, USA).

DNA-binding assay

Complementary pairs of 5′ biotinylated oligonucleotides containing the wild-type (5′GCCCTACGTGCTGTCTCATACGTGCTGTCTCA3′) or mutated (5′GCCC-TAAAAGCTGTCTCATAAAAGCTGTCTCA3′) hypoxia response element (HRE) sequences (consensus region underlined; based on the human VEGF promoter sequence; Liu et al. 1995) were synthesized (Sigma Genosys) and annealed. Nuclear extracts from endothelial cells subjected to no stretch or static 10% stretch for 4 h were used to quantify HIF-1α and HIF-2α interactions with HRE elements, according to kit instructions (TransFactor Universal Chemiluminescent; Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). Each nuclear extract was assayed in duplicate, and a total of three independent experiments were analysed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Student's paired t test, or one-way ANOVA, followed by Fisher's or Tukey post hoc tests, as appropriate, using StatView 5.0 or GraphPad Prism 4. Results are expressed as means ± s.e.m. for at least three separate experiments for each treatment. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Laser capture microdissection (LCM) was used to isolate capillaries from rat skeletal muscles (Fig. 1A–D) for analysis of gene expression of VEGF-A, HIF-1α and HIF-2α from this capillary-enriched sample. Muscle overload, which causes stretch of the surrounding capillaries (Ellis et al. 1990), resulted in significant increases in HIF-1α mRNA after 4 and 7 days (Fig. 1E), while HIF-2α expression was augmented after 4 days (P = 0.059 versus control) followed by significant elevation after day 7 of stretch (P < 0.05 versus control; Fig. 1F). VEGF-A mRNA in the same capillaries was increased after 7 days of treatment (Fig. 1G). In response to prazosin treatment, HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA were elevated after 2 days, but were not significant compared with control values by 4 and 7 days of treatment (Fig. 1H and I). VEGF-A mRNA increased significantly after 2 and 4 days of prazosin treatment, yet was reduced, to 50% of control values, after 7 days (Fig. 1J). HIF-1α protein was detectable in myonuclei and in capillary structures, and HIF-2α showed a similar but weaker pattern of production. Staining intensity of both HIF-1α and HIF-2α were greater in 7 day stretched compared with unstretched muscles, and prazosin-treated samples appeared similar to control (Supplementa1 Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Analysis of mRNA from LCM-captured capillaries shows differential changes in expression of HIF-1α, HIF-2α and VEGF mRNA during overload-induced muscle stretch or prazosin-induced elevation in shear stress.

To facilitate the laser capture microdissection (LCM) process, capillaries were visualized by Alexa488-lectin staining (A), then targeted by the laser beam. (B), dark bands on the tissue define individual laser activations. (C), captured capillaries were no longer detectable within the tissue section after removal of the LCM cap. (D), the isolated capillaries were observable on the surface of the LCM cap. (A–D), arrows mark the same three capillaries. Total RNA was isolated from the capillaries captured from extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles and the relative mRNA expression levels of HIF-1α (E and H), HIF-2α (F and I), and VEGF-A (G and J), were determined by real-time quantitative PCR (q-PCR). mRNA levels were analysed for samples taken from muscles subjected to stretch for 4 or 7 days (E–G), or to elevated shear stress for 2, 4 or 7 days (H–J). In each case, values of mRNA amounts were normalized to 18S rRNA and expressed relative to sham-operated controls. Error bars represent s.e.m.*P < 0.05 versus controls; n = 4.

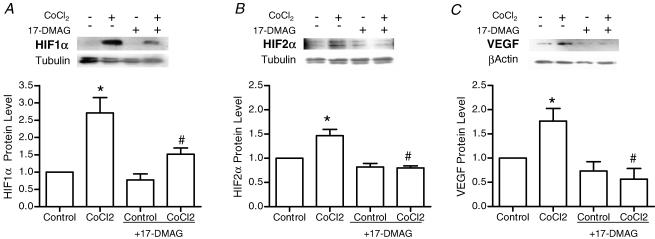

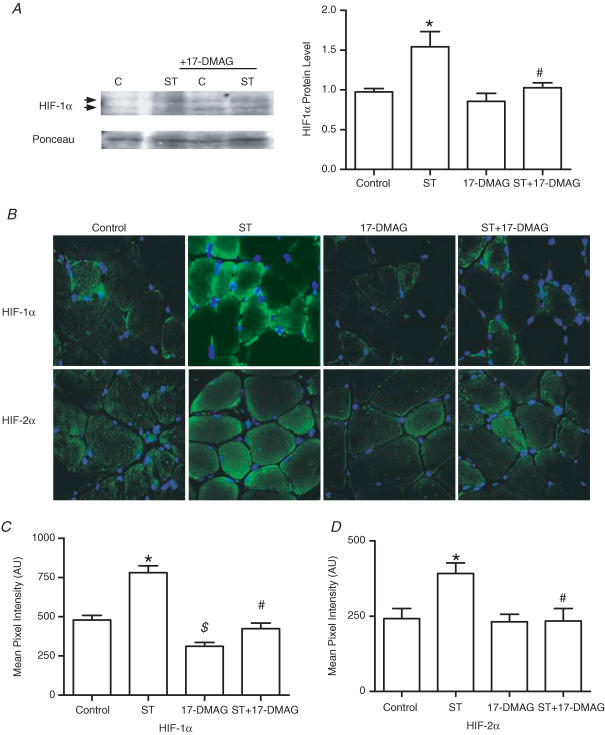

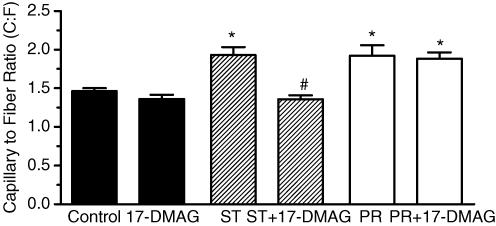

A HIF-destabilizing drug was used to test the requirement of HIF proteins in the angiogenesis response to stretch or shear stress. Interaction of HIF-1α and HIF-2α with heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) is essential for the accumulation and subsequent nuclear transport of these transcription factors (Minet et al. 1999b; Katschinski et al. 2004; Isaacs et al. 2004). The geldanamycin-derived Hsp90 inhibitor, 17-DMAG, reduces the interaction of Hsp90 with HIF, promoting HIF protein destabilization and subsequent degradation. Drug efficacy and specificity was confirmed first in cultured cells. 17-DMAG significantly decreased basal and cobalt chloride-induced HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein levels, as well as the expression of HIF target gene VEGF-A (Fig. 2). In contrast to the effects on HIF-α proteins, we found that expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (which is regulated by ERK1/2, JNK1/2 and PI3K pathways (Boyd et al. 2005; Ispanovic & Haas, 2006; Milkiewicz et al. 2007) but is not a direct transcriptional target of HIF family transcription factors) was unaffected by 17-DMAG treatment in vitro (Supplementa1 Table 1). Further, 17-DMAG treatment did not reduce the increase in MMP-2 typically observed in overloaded muscle (Supplementa1 Table 2). In rat experiments, localized delivery of 17-DMAG to the EDL muscle effectively reduced HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein levels within the EDL, as assessed by Western blotting (Fig. 3A; the signal was detectable in whole-muscle homogenates for HIF-1α, but not for HIF-2α) and immunostaining (HIF-1α and HIF-2α; Fig. 3B and C). The effect of HIF-α inhibition on stretch-induced capillary growth was analysed. Treatment with 17-DMAG completely blocked angiogenesis in stretched skeletal muscle, as capillary to fibre ratio in stretch + 17-DMAG muscles was not different from vehicle or drug-treated unstretched muscles, and was significantly lower than that measured in vehicle-treated stretched muscle (Fig. 4). In contrast, continuous delivery of 17-DMAG for 7 days did not inhibit the increased capillary number observed in response to chronic dilator treatment (Fig. 4).

Figure 2. Effect of 17-DMAG, an Hsp90 inhibitor, on HIF-1α, HIF-2α and VEGF-A protein production in cultured endothelial cells.

Cells were treated overnight with cobalt chloride (0.1 mm) to induce HIF protein accumulation, in the absence and presence of 17-DMAG (3 μm). Cell lysates were analysed by Western blot for HIF-1α (A), HIF-2α (B) and VEGF-A (C). Loading variability was normalized according to levels of tubulin (HIF blots) or β-actin (VEGF blots). *P < 0.05 compared with control; #P < 0.05 compared with cobalt chloride treatment; n = 3 or 4 for each protein analysed.

Figure 3. Effect of 17-DMAG on HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein production in rat EDL muscles.

A, Western blotting of skeletal muscle extracts showed increased HIF-1α protein in muscles subjected to overload (ST), and this was not observed in muscles subjected to overload in combination with 17-DMAG (ST + DMAG). Ponceau S staining of membranes was used to normalize for loading. *P < 0.05 compared with control unstretched; #P < 0.05 compared with 7 day overload (ST). B, immunostaining was performed on control, 7 day overload (ST), 17-DMAG-treated, and 7 day overload + 17-DMAG-treated (ST+17-DMAG), EDL muscles. Images in the top panels represent HIF-1α immunodetection (green) and those in the bottom panels correspond to HIF-2α immunostaining (green). Corresponding DAPI staining (blue) was used to visualize nuclei. All images were collected using a ×40 objective. Exposure settings used to capture images of HIF-1α staining were identical for all conditions. Pixel intensity quantification of all conditions immunostained for HIF-1α (C) and HIF-2α (D) identified significant increases in staining intensity in overload (ST) compared with control (C; *P < 0.05). Intensity of HIF-α staining in ST+DMAG was reduced significantly compared with ST (#P < 0.05). HIF-1α staining was reduced in unstretched muscles treated with DMAG compared with vehicle treatment ($P < 0.05).

Figure 4. Destabilization of HIF-1α protein using 17-DMAG inhibits stretch-induced but not shear-stress-induced angiogenesis in EDL muscles.

Capillary supply was evaluated on the basis of capillary staining by alkaline phosphatase and expressed as capillary-per-fibre ratio, C:F. Rats were treated continuously with vehicle (control) or 17-DMAG delivered locally to the muscle via an implanted osmotic pump. After 14 days, C:F ratio was elevated significantly in stretched muscles compared with control or 17-DMAG-treated muscle (*P < 0.05 versus control). Stretch + 17-DMAG-treated (ST+17-DMAG) muscles had a significantly lower C:F ratio compared with stretch alone (#P < 0.001 versus stretch). 17-DMAG treatment itself did not modify C:F compared with control muscles. Prazosin (PR) treatment for 7 days resulted in significantly greater C:F compared with control. In this case, the C:F for PR+17-DMAG was not different from PR alone. Data are shown as means ± s.e.m.; n = 4.

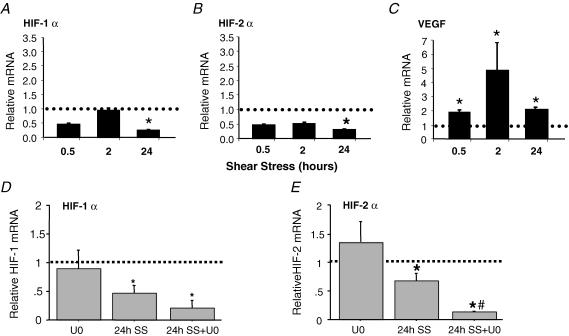

To support the evidence that shear-stress-induced angiogenesis does not involve increases in HIF-α, we exposed cultured microvascular endothelial cells to laminar shear stress (16 dyn cm−2 (16 ×10−5 N cm−2)) for 30 min to 24 h. Elevated shear stress did not enhance HIF-1α or HIF-2α mRNA expression and, in fact, mRNA levels were downregulated significantly after 24 h (Fig 5A and B). HIF-1α and HIF-2α proteins were not detectable by Western blotting in cells stimulated by shear stress (data not shown). In contrast, shear-stress-induced substantial increases in VEGF-A mRNA as early as 30 min after shear stress exposure, and mRNA remained elevated up to 24 h (Fig. 5C). The shear-stress-induced repression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA was augmented in the presence of the ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 5D and E). We also tested whether shear-stress-induced nitric oxide production contributed to the reduction in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA. However, treatment of cells with the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor l-NNA relieved the shear-stress-induced suppression of HIF-2α, but not of HIF-1α mRNA (HIF-2α mRNA: control set to 1; 24 h shear stress, 0.4 ± 0.02*; 24 h shear stress +l-NNA, 0.98 ± 0.15**; n = 3; *P < 0.05 compared with control; **P < 0.05 compared with shear stress).

Figure 5. Regulation of VEGF-A, HIF-1α and HIF-2α by shear-stress stimulation of cultured microvascular endothelial cells.

Cells were subjected to 16 dyne cm−2 laminar shear stress (SS) for 0.5, 2 and 24 h. mRNA levels of HIF-1α (A) HIF-2α (B) and VEGF-A (C) were determined by real-time q-PCR. Levels of target genes were normalized to 18S rRNA, then expressed relative to static time-matched controls (set to 1). Each bar represents the mean ± s.e.m. of at least four experiments. *P < 0.05 versus control. In a subsequent set of experiments, endothelial cells were pretreated with vehicle or the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (U0; 0.3 μm) prior to shear or static exposure for 24 h. Real-time q-PCR of HIF-1α mRNA (D) showed a trend for further reductions in HIF-1α mRNA in shear-exposed cells with U0 treatment, while the reduction in HIF-2α mRNA was significantly greater in cells treated with U0 in combination with shear stress than in cells stimulated by shear stress itself (E). For each time point and drug treatment, mRNA levels in sheared samples were expressed as a ratio to their respective static control (set to 1). The dotted line represents the control level for each condition. n = 3; *P < 0.05 compared with control; #P < 0.05 compared with shear stress.

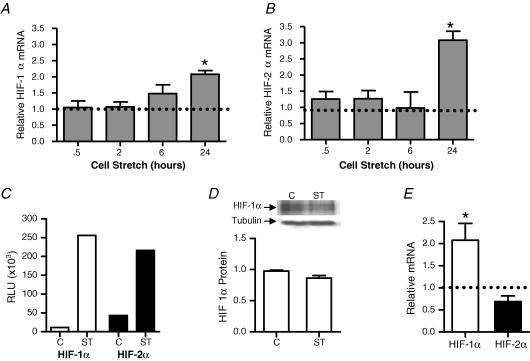

To further examine the responsiveness of HIF-α gene expression to muscle stretch, we tested whether direct application of stretch to cultured microvascular endothelial cells would alter expression of HIF-α transcription factors. In cultured microvascular endothelial cells, up to 6 h of static stretch did not alter levels of HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA, but significant increases in both mRNA transcripts were detectable at 24 h (Fig. 6A and B). Earlier observations indicated that VEGF-A mRNA and protein increased significantly in microvascular endothelial cells subjected to 10% static stretch for 24 h (Milkiewicz et al. 2007). DNA-binding assays showed that 4 h of stretch was sufficient to cause an increased association of HIF-1α and HIF-2α proteins with their consensus DNA-binding sequence (Fig. 6C). This increased activity occurred in the absence of a change in total cellular HIF-1α protein (Fig. 6D). We considered the possibility that initial increases in HIF DNA-binding activity could contribute to the later increase in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA. We treated cells with the FIH-1 inhibitor, clioquinol, which is known to increase the amount of functionally active HIF-α through preventing asparaginyl hydroxylation of HIF-α (Choi et al. 2006) and thus preserving the capacity of HIF-α to interact with the transcriptional coactivator CBP/p300 (Freedman et al. 2002; Lando et al. 2002; Stolze et al. 2004; Brahimi-Horn et al. 2005). HIF-1α but not HIF-2α mRNA increased significantly in cells treated with clioquinol (Fig. 6E). Conversely, treatment of cells with 17-DMAG significantly reduced levels of HIF-1α mRNA in endothelial cells (0.10 ± 0.09 versus control 1.0 ± 0.03; P < 0.01; n = 3).

Figure 6. Effect of mechanical stretch on expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in cultured microvascular endothelial cells.

Cells were subjected to 10% static stretch for 0.5, 2, 6 and 24 h. mRNA levels of HIF-1α (A) and HIF-2α (B) were determined by real-time q-PCR. Levels of target genes were normalized to 18S rRNA and expressed relative to unstretched time-matched controls (set to 1). Each bar represents the mean ± s.e.m. of at least four experiments. *P < 0.05 versus control. Dotted lines represent the level of HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA in unstretched samples for each time point. DNA-binding assays were performed on nuclear extracts isolated from control cells and cells subjected to 10% static stretch for 4 h (C). HIF-1α (open bars) and HIF-2α (filled bars) both exhibited greater binding to the hypoxia response element (HRE) in nuclear extracts from stretched cells. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Western blot analysis of HIF-1α from extracts of control or stretched (4 h) endothelial cells showed no significant change in protein quantity in response to stretch (D). Cells were treated with clioquinol (100 μm) or vehicle for 6 h, followed by lysis and analysis of HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA transcripts by q-PCR (E). Data are expressed relative to control (set to 1). *P < 0.05 versus control, n = 4.

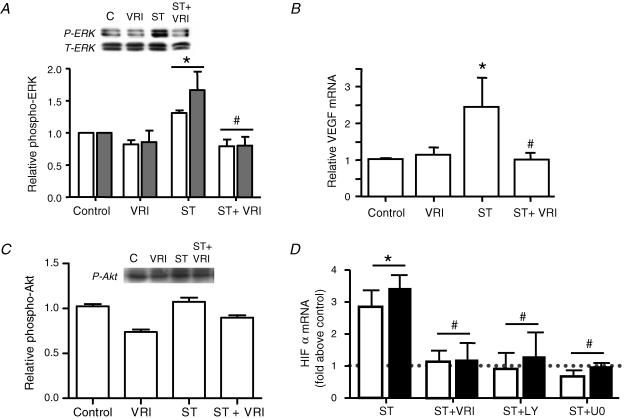

Based on reports that demonstrated non-hypoxic modulation of HIF-1α via receptor tyrosine kinase, PI3K and/or ERK1/2 signalling (Zhong et al. 2000; Skinner et al. 2004; Peng et al. 2006), we examined whether components of the VEGFR2 signal pathway contribute to the stretch-induced increases in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA. Previously, we have shown that ERK1/2 phosphorylation increases rapidly upon stretch stimulation of endothelial cells, reaching a maximum at 10 min, followed by gradual decline to control levels by 24 h (Milkiewicz et al. 2007). Treatment of endothelial cells with VEGFR2 kinase inhibitor I (VRI) prevented the stretch-induced increases in ERK1/2 phosphorylation and VEGF mRNA expression (Fig. 7A and B). Conversely, Akt phosphorylation was not increased after 10 min stretch, and was not modulated significantly by VEGFR2 inhibition (Fig. 7C). Pretreatment of microvascular endothelial cells with VEGFR2 inhibitor VRI (10 μm), PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (10 μm) or MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (0.3 μm) substantially reduced the stretch-induced expression of HIF-1α (Fig. 7D) and HIF-2α (Fig. 7E) mRNA.

Figure 7. Effect of VEGFR2-dependent signalling on HIF-1α and HIF-2α gene expression in stretched microvascular endothelial cells.

VEGFR2 inhibition (VRI; 10 μm) reduced the typical increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation (A) induced following 10 min exposure to 10% static stretch (ST). Phospho-ERK values were normalized to total ERK, and expressed relative to unstretched controls. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.; n = 3 or 4; *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus ST. VEGFR2 inhibition also reduced the stretch-induced increase in VEGF mRNA observed at 24 h of 10% static stretch (B). Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.; n = 3 or 4; *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus ST. Phosphorylation of Akt was not altered significantly measured in response to 10 min stretch, in the absence or presence of the VEGFR2 inhibitor (C). Pre-treatment of cells with VEGFR2 inhibitor I (VRI; 10 μm), PI3K inhibitor (LY; 10 μm), or MEK1/2 inhibitor (U0; 0.3 μm), significantly diminished the stretch-induced (ST; 24 h, 10%) expression of HIF-1α (open bars) and HIF-2α mRNA (solid bars) compared with their respective drug-treated unstretched controls (D). Data are presented as means ± s.e.m.; n = 3 or 4; #P < 0.05 versus ST + vehicle (ST).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that endothelial cell production of HIF-1α and HIF-2α responds uniquely to different forms of mechanical stimuli. The essential role of HIF-α proteins during stretch-induced angiogenesis was illustrated by the inhibition of capillary growth that was observed during treatment with 17-DMAG, a drug that prevents the accumulation of HIF-α protein. In contrast, HIF-α protein accumulation was not required for shear-stress-dependent angiogenesis, despite the increase in VEGF-A observed in response to shear stress.

We observed significant increases in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA and protein in capillaries following skeletal muscle stretch, as well as increases in DNA binding and mRNA levels in cultured endothelial cells subjected to static stretch. Kim et al. (2002) first demonstrated the induction of HIF-1α protein in response to elevated mechanical stress in non-hypoxic myocardium by modulating left ventricular wall tension by aortocaval shunt or by intraventricular balloon expansion. An increase in HIF-1α protein also was detected following 24 h cyclic stretch of fibroblasts (Petersen et al. 2004). While neither of those studies detected changes in HIF-1α mRNA level, transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α was reported in vascular smooth muscle cells stimulated by angiotensin II (Page et al. 2002) or by cyclic stretch (Chang et al. 2003). We consider it is unlikely that the observed increases in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA in response to stretch involves a hypoxic stimulus, particularly as HIF-1α mRNA is not induced by hypoxia (Huang et al. 1996), and the in vitro stretch experiments were conducted in 21% oxygen. While it is difficult to assess skeletal myocyte PO2 in EDL during stretch/overload, numerous studies indicate that the magnitude of stretch elicited within the muscle is not sufficient to reduce capillary or arteriole diameter or capillary haematocrit (Kindig & Poole, 1999, 2001), and that blood flow to the muscle is not impaired (Armstrong et al. 1986; Egginton et al. 1998), implying that oxygen delivery to the muscle is maintained. However, we cannot exclude the possibility of a hypoxic component to the upregulation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α in response to EDL stretch/overload.

Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α interact with Hsp90 via their bHLH-PAS domains, which facilitates the rapid accumulation of HIF proteins, as well as their DNA-binding and transcriptional activation in normoxic and hypoxic conditions (Minet et al. 1999b; Isaacs et al. 2002; Katschinski et al. 2004). The Hsp90 inhibitor 17-DMAG was effective in reducing HIF-α levels both in vitro and in vivo. Delivery of 17-DMAG blocked the mechanical stretch-induced capillary growth in overloaded EDL. Unlike the response observed in overloaded muscles, 17-DMAG treatment had no effect on the typical increase in capillary number occurring in response to elevated capillary shear stress.

Our results point to involvement of PI3K and ERK1/2 in inducing the increases in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA in response to stretch. Both kinases are known to be associated intimately with regulation of HIF-1α protein translation, stabilization and transcriptional activity (Feldser et al. 1999; Zhong et al. 2000; Berra et al. 2000; Laughner et al. 2001; Brahimi-Horn et al. 2005). ERK1/2 activity enhances nuclear translocation of HIF-1α (Mylonis et al. 2006), and the association of HIF-1α with its coactivator CBP/p300 (Sang et al. 2003). Through phosphorylation of HIF-1α, ERK1/2 can enhance HIF-1-dependent transcriptional activity by limiting HIF-1α nuclear export50. The P13K/mTOR signalling pathway, through activation of p70S6K1 and 4E-BP1, stimulates translation of HIF-1α mRNA in response to myocardial stretch, IGF-1 and AngII (Kim et al. 2002; Page et al. 2002; Treins et al. 2005). Because we did not observe increases in HIF-1α protein at 4 or 24 h of stretch in cultured cells, it appears unlikely that translation of HIF-1α was increased during this time period. This is consistent with a lack of phosphorylation of Akt upon acute stretch stimulation. However, significant increases in HIF-1α protein were observed in the 7 day stretched EDL muscle, which may be consistent with reports of prolonged activation of Akt/mTOR/p70S6K within the skeletal muscle fibres in response to an overload stimulus (Bodine et al. 2001). Based on in vitro results, we suggest that the early (4 h time point) increase in HIF-1α and HIF-2α DNA-binding activity contributes to the subsequent increases in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA through autocrine transcriptional control. Consonant with this idea, the mRNA response was inhibited by blocking pathways known to affect HIF-α protein levels, and the HIF-1α promoter contains one or more HREs (Minet et al. 1999a; De Armond et al. 2005). Further, treatment of cells with the FIH inhibitor clioquinol, which has been previously demonstrated to increase HIF-dependent transcription by preventing asparaginyl hydroxylation at Asn803 within the HIF C-terminal activation domain (Choi et al. 2006), resulted in elevated levels of HIF-1α but not HIF-2α mRNA. Further study is required to define possible roles for altered FIH hydroxylase activity, HIF-1α and/or p300 phosphorylation by ERK1/2 (Mylonis et al. 2006; Sang et al. 2003) in modulating HIF-1α- and HIF-2α-dependent transcription in response to stretch stimulation.

Interestingly, we found that inhibition of VEGFR2 in cultured endothelial cells prevented HIF-1α and HIF-2α gene activation and reduced VEGF mRNA level induced by mechanical stretch. While VEGFR2-dependent modulation of HIF-1α and VEGF expression (via the PI3K/AKT/p70S6K1 signalling pathway) has been reported in ovary cancer cells (Zhong et al. 2004; Fang et al. 2005), to our knowledge, this is the first evidence of stretch-induced VEGFR2 signalling. However, precedent clearly exists for mechano-activation of this receptor, as VEGFR2 activation in response to shear stress occurs independently of ligand binding (Jin et al. 2003).

Cultured microvascular endothelial cells responded to elevated shear stress with a substantial increase in VEGF-A mRNA, which was sustained over 24 h of shear exposure. Notably, the gene expression profiles of HIF-1α or HIF-2α did not parallel that of VEGF-A, as significant decreases in both HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA levels occurred by 24 h of shear exposure, and HIF-α protein levels were undetectable in sheared cells. These results clearly indicate that shear-induced VEGF production is not controlled by HIFs. The VEGF promoter, in addition to HRE-dependent transcription, can be activated by Sp-1 (Bradbury et al. 2005). Because Sp-1 phosphorylation and DNA-binding activity increases under shear-stress conditions (Yun et al. 2002), it is possible that Sp-1 contributes to the observed increase in VEGF mRNA in shear-stimulated endothelial cells. The mechanism by which shear stress reduced HIF-1α and HIF-2α in cultured endothelial cells requires additional study. Repression of nitric oxide production relieved the shear-stress-induced repression of HIF-2α, but did not significantly affect HIF-1α mRNA levels. This differential regulation of HIF-1α and HIF-2α transcription is consistent with reports of divergent roles of these two transcriptional regulators (Carroll & Ashcroft, 2006).

In contrast to the response of cultured endothelial cells exposed to elevated shear stress, expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA transiently increased in EDL capillaries from prazosin-treated rats. This increase in mRNA (seen at 2 days) occurs much earlier than the increase in capillary number (detectable at 7 days), and it may correspond to a different initial pattern of the positive regulators of HIF expression, PI3K or ERK1/2, in vivo compared with in vitro. The mechanisms underlying this difference require further examination. However, results from the 17-DMAG treatment imply that this transient increase in HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA is not a critical component of the shear-stress-induced angiogenesis process.

Findings from this study indicate that ERK1/2 is a positive modulator of HIF-1α and HIF-2α expression. During either shear-stress or stretch stimulation, HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA decreased when cells were cotreated with an inhibitor of ERK1/2 activation. Previously, we demonstrated a strong activation of ERK1/2 in response to stretch, which was necessary to promote stretch-induced increases in VEGF mRNA (Milkiewicz et al. 2007). In response to shear stress, ERK1/2 increase transiently, but was counter-balanced by a sustained activation of p38 MAPK (Milkiewicz et al. 2006). These patterns of ERK1/2 activation correlate closely with the observed effects of stretch and shear stress on HIF-1α and HIF-2α mRNA. Consistent with the effect of VEGFR2 inhibition on HIF mRNA in response to stretch, pharmacological inhibition of VEGFR2 abolished the stretch-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2.

Our results demonstrate that the transcription factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α are angiogenic mediators during adaptation to constant mechanical stress present in vasculature of skeletal muscle. The contrast in involvement of HIF-1α and/or HIF-2α in the process of capillary growth in response to stretch, but not in response to shear stress, complements the growing body of knowledge that differential patterns of capillary growth occur in response to muscle stretch and shear stress stimulation (Egginton et al. 2001; Williams et al. 2006a, b). Muscle stretch produced by sustained overload induces capillary growth by means of the invasive process of abluminal sprouting (; Zhou et al. 1998b; Egginton et al. 2001; Rivilis et al. 2002), which relies on endothelial cell proliferation, proteolysis and migration (Ausprunk & Folkman, 1977). In contrast, shear-stress-induced capillary growth occurs via internal or luminal division of capillaries, which lacks an invasive phenotype (Zhou et al. 1998a; Egginton et al. 2001), as it involves minimal endothelial cell proliferation, production of proteases, or formation of abluminal sprouts (Milkiewicz et al. 2001; Rivilis et al. 2002). Identification of the diverse stimulus-dependent patterns of expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α advances our knowledge of the molecular events that control these different modes of capillary growth. These findings have implications for the design and interpretation of gene-based therapies using angiogenic growth factors or transcription factors. Further investigation of the interplay between HIF-1α and HIF-2α and their downstream gene targets will facilitate the launching of more successful strategies for the therapeutic manipulation of angiogenesis in ischaemic skeletal muscle.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the assistance of Cassandra Uchida and Gagan Dhanota with laser capture microdissection. T.L.H. received funding for this work from a Canadian Institutes of Health Research research grant and New Investigator award, and from the Premiers Research Excellence Award (Government of Ontario).

Supplemental material

Online supplemental material for this paper can be accessed at:

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2007.136325/DC1

and

http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/suppl/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.136325

References

- Armstrong RB, Ianuzzo CD, Laughlin MH. Blood flow and glycogen use in hypertrophied rat muscles during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61:683–687. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausprunk DH, Folkman J. Migration and proliferation of endothelial cells in preformed and newly formed blood vessels during tumor angiogenesis. Microvasc Res. 1977;14:53–65. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(77)90141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berra E, Milanini J, Richard DE, Le Gall M, Vinals F, Gothie E, Roux D, Pages G, Pouyssegur J. Signaling angiogenesis via p42/p44 MAP kinase and hypoxia. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00423-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonzalez M, Kline WO, Stover GL, Bauerlein R, Zlotchenko E, Scrimgeour A, Lawrence JC, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nature Cell Biol. 2001;3:1014–1019. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd PJ, Doyle J, Gee E, Pallan S, Haas TL. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling regulates endothelial cell assembly into networks and the expression of MT1-MMP and MMP—. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C659–C668. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00211.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury D, Clarke D, Seedhouse C, Corbett L, Stocks J, Knox A. Vascular endothelial growth factor induction by prostaglandin E2 in human airway smooth muscle cells is mediated by E prostanoid EP2/EP4 receptors and SP-1 transcription factor binding sites. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29993–30000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahimi-Horn C, Mazure N, Pouyssegur J. Signalling via the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α requires multiple posttranslational modifications. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll VA, Ashcroft M. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) 1 αversus HIF-2 α in the regulation of HIF target genes in response to hypoxia, insulin-like growth factor-I, or loss of von Hippel-Lindau function: implications for targeting the HIF pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6264–6270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Shyu KG, Wang BW, Kuan P. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α by cyclical mechanical stretch in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;105:447–456. doi: 10.1042/CS20030088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien S. Mechanotransduction and endothelial cell homeostasis: the wisdom of the cell. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1209–H1224. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01047.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SM, Choi KO, Park YK, Cho H, Yang EG, Park H. Clioquinol, a Cu(II)/Zn(II) chelator, inhibits both ubiquitination and asparagine hydroxylation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α, leading to expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and erythropoietin in normoxic cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34056–34063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PF. Flow-mediated endothelial mechanotransduction. Physiol Rev. 1995;75:519–560. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1995.75.3.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JM, Hudlicka O. The effects of long term administration of prazosin on the microcirculation in skeletal muscles. Cardiovasc Res. 1989;23:913–920. doi: 10.1093/cvr/23.11.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Armond R, Wood S, Sun DY, Hurley LH, Ebbinghaus SW. Evidence for the presence of a guanine quadruplex forming region within a polypurine tract of the hypoxia inducible factor 1 α promoter. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16341–16350. doi: 10.1021/bi051618u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dor Y, Djonov V, Keshet E. Making vascular networks in the adult: branching morphogenesis without a roadmap. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egginton S, Hudlicka O, Brown MD, Walter H, Weiss JB, Bate A. Capillary growth in relation to blood flow and performance in overloaded rat skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:2025–2032. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.6.2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egginton S, Zhou AL, Brown MD, Hudlicka O. Unorthodox angiogenesis in skeletal muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:634–646. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CG, Mathieucostello O, Potter RF, Macdonald IC, Groom AC. Effect of sarcomere-length on total capillary length in skeletal-muscle –in vivo evidence for longitudinal stretching of capillaries. Microvasc Res. 1990;40:63–72. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(90)90008-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M, Taya S, Yokotani N, Sogawa K, Matsuda Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. A novel bHLH-PAS factor with close sequence similarity to hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α regulates the VEGF expression and is potentially involved in lung and vascular development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4273–4278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Xia C, Cao ZX, Zheng JZ, Reed E, Jiang BH. Apigenin inhibits VEGF and HIF-1 expression via P13K/AKT/p70S6K1 and HDM2/p53 pathways. FASEB J. 2005;19:342–353. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2175com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldser D, Agani F, Iyer NV, Pak B, Ferreira G, Semenza GL. Reciprocal positive regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α and insulin-like growth factor 2. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3915–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Fundamental concepts of the angiogenic process. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:643–651. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman SJ, Sun ZY, Poy F, Kung AL, Livingston DM, Wagner G, Eck MJ. Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5367–5372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082117899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han XY, Boyd PJ, Colgan S, Madri JA, Haas TL. Transcriptional up-regulation of endothelial cell matrix metalloproteinase 2 in response to extracellular cues involves GATA-2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47785–47791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309482200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AL. Hypoxia – a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/nrc704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1 α) and HIF 2 α in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LE, Arany Z, Livingston DM, Bunn HF. Activation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor depends primarily upon redox-sensitive stabilization of its alpha subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32253–32259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudetz AG, Kiani MF. The role of wall shear stress in microvascular network adaptation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;316:31–39. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3404-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudlicka O, Brown MD, Egginton S. Angiogenesis in skeletal and cardiac muscle. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:369–417. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber DE. Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. FASEB J. 2006;20:811–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5424rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Mimnaugh EG, Martinez A, Cuttitta F, Neckers LM. Hsp90 regulates a von-Hippel-Lindau-independent hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α -degradative pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29936–29944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Neckers L. Aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator (ARNT) promotes oxygen-independent stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α by modulating an Hsp90-dependent regulatory pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16128–16135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313342200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ispanovic E, Haas TL. JNK and PI3K differentially regulate MMP-2 and MT1-MMP mRNA and protein in response to actin cytoskeleton reorganization in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C579–C588. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00300.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin ZG, Ueba H, Tanimoto T, Lungu AO, Frame MD, Berk BC. Ligand-independent activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 by fluid shear stress regulates activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circ Res. 2003;93:354–363. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089257.94002.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakinuma Y, Ando M, Kuwabara M, Katare RG, Okudela K, Kobayashi M, Sato T. Acetylcholine from vagal stimulation protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia and hypoxia involving additive non-hypoxic induction of HIF-1 α. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2111–2118. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katschinski DM, Le L, Schindler SG, Thomas T, Voss AK, Wenger RH. Interaction of the PAS B domain with HSP90 accelerates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α stabilization. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2004;14:351–360. doi: 10.1159/000080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CH, Cho YS, Chun YS, Park JW, Kim MS. Early expression of myocardial HIF-1 α in response to mechanical stresses: regulation by stretch-activated channels and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway. Circ Res. 2002;90:E25–E33. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.104923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindig CA, Poole DC. Effects of skeletal muscle sarcomere length on in vivo capillary distensibility. Microvasc Res. 1999;57:144–152. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1998.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindig CA, Poole DC. Sarcomere length-induced alterations of capillary hemodynamics in rat spinotrapezius muscle: vasoactive vs passive control. Microvasc Res. 2001;61:64–74. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2000.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lando D, Peet DJ, Gorman JJ, Whelan DA, Whitelaw ML, Bruick RK. FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1466–1471. doi: 10.1101/gad.991402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughner E, Taghavi P, Chiles K, Mahon PC, Semenza GL. HER2 (neu) signaling increases the rate of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α (HIF-1 α) synthesis: novel mechanism for HIF-1-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3995–4004. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.12.3995-4004.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux S, Tedgui A. Signal transduction of mechanical stresses in the vascular wall. Hypertension. 1998;32:338–345. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Cox SR, Morita T, Kourembanas S. Hypoxia regulates vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in endothelial cells: identification of a 5′-enhancer. Circ Res. 1995;77:638–643. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiewicz M, Brown MD, Egginton S, Hudlicka O. Association between shear stress, angiogenesis, and VEGF in skeletal muscles in vivo. Microcirculation. 2001;8:229–241. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiewicz M, Haas TL. Effect of mechanical stretch on HIF-1 α and MMP-2 expression in capillaries isolated from overloaded skeletal muscles: laser capture microdissection study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1315–H1320. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00284.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiewicz M, Kelland C, Colgan S, Haas TL. Nitric oxide and p38 MAP kinase mediate shear stress-dependent inhibition of MMP-2 production in microvascular endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:229–237. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiewicz M, Mohammedzadeh F, Ispanovic E, Gee E, Haas TL. Static strain stimulates expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and VEGF in microvascular endothelium via JNK and ERK dependent pathways. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:750–761. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiewicz M, Pugh CW, Egginton S. Inhibition of endogenous HIF inactivation induces angiogenesis in ischaemic skeletal muscles of mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:21–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minet E, Ernest I, Michel G, Roland I, Remacle J, Raes M, Michiels C. HIF1A gene transcription is dependent on a core promoter sequence encompassing activating and inhibiting sequences located upstream from the transcription initiation site and cis elements located within the 5′UTR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999a;261:534–540. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minet E, Mottet D, Michel G, Roland I, Raes M, Remacle J, Michiels C. Hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1: role of HIF–1alpha–Hsp90 interaction. FEBS Lett. 1999b;460:251–256. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mylonis I, Chachami G, Samiotaki M, Panayotou G, Paraskeva E, Kalousi A, Georgatsou E, Bonanou S, Simos G. Identification of MAPK phosphorylation sites and their role in the localization and activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33095–33106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605058200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page EL, Robitaille GA, Pouyssegur J, Richard DE. Induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α by transcriptional and translational mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48403–48409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng XH, Karna P, Cao Z, Jiang BH, Zhou M, Yang L. Cross-talk between epidermal growth factor receptor and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α signal pathways increases resistance to apoptosis by up-regulating survivin gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25903–25914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603414200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper MS. Manipulating angiogenesis. From basic science to the bedside. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:605–619. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen W, Varoga D, Zantop T, Hassenpflug J, Mentlein R, Pufe T. Cyclic strain influences the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and the hypoxia inducible factor 1 α (HIF-1 α) in tendon fibroblasts. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pries AR, Reglin B, Secomb TW. Structural adaptation of microvascular networks: functional roles of adaptive responses. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1015–H1025. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior BM, Yang HT, Terjung RL. What makes vessels grow with exercise training? J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1119–1128. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00035.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ. Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5675–5686. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.13.5675-5686.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard DE, Berra E, Pouyssegur J. Nonhypoxic pathway mediates the induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26765–26771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivilis I, Milkiewicz M, Boyd P, Goldstein J, Brown MD, Egginton S, Hansen FM, Hudlicka O, Haas TL. Differential involvement of MMP-2 and VEGF during muscle stretch- versus shear stress-induced angiogenesis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1430–H1438. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00082.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang N, Stiehl DP, Bohensky J, Leshchinsky I, Srinivas V, Caro J. MAPK signaling up-regulates the activity of hypoxia-inducible factors by its effects on p300. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14013–14019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209702200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and the molecular physiology of oxygen homeostasis. J Lab Clin Med. 1998;131:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(98)90091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. HIF-1, O(2), and the 3 PHDs: how animal cells signal hypoxia to the nucleus. Cell. 2001;107:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HD, Zheng JZ, Fang J, Agani F, Jiang BH. Vascular endothelial growth factor transcriptional activation is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α, HDM2, and p70S6K1 in response to phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45643–45651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolze IP, Tian YM, Appelhoff RJ, Turley H, Wykoff CC, Gleadle JM, Ratcliffe PJ. Genetic analysis of the role of the asparaginyl hydroxylase factor inhibiting hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) in regulating HIF transcriptional target genes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42719–42725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treins C, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Murdaca J, Monthouel-Kartmann MN, Van Obberghen E. Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 activity and expression of HIF hydroxylases in response to insulin-like growth factor I. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1304–1317. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang V, Davis DA, Haque M, Huang LE, Yarchoan R. Differential gene up-regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 α and hypoxia-inducible factor-2 α in HEK293T cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3299–3306. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JL, Cartland D, Hussain A, Egginton S. A differential role for nitric oxide in two forms of physiological angiogenesis in mouse. J Physiol. 2006b;570:445–454. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JL, Weichert A, Zakrzewicz A, Silva-Azevedo L, Pries AR, Baum O, Egginton S. Differential gene and protein expression in abluminal sprouting and intraluminal splitting forms of angiogenesis. Clin Sci. 2006a;110:587–595. doi: 10.1042/CS20050185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun S, Dardik A, Haga M, Yamashita A, Yamaguchi S, Koh Y, Madri JA, Sumpio BE. Transcription factor Sp1 phosphorylation induced by shear stress inhibits membrane type 1-matrix metalloprotinase expression in endothelium. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34808–34814. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Chiles K, Feldser D, Laughner E, Hanrahan C, Georgescu MM, Simons JW, Semenza GL. Modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α expression by the epidermal growth factor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/FRAP pathway in human prostate cancer cells: implications for tumor angiogenesis and therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong XS, Zheng JZ, Reed E, Jiang BH. SU5416 inhibited VEGF and HIF-1α expression through the PI3K/AKT/p70S6K1 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324:471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou AL, Egginton S, Brown MD, Hudlicka O. Capillary growth in overloaded, hypertrophic adult rat skeletal muscle: an ultrastructural study. Anat Rec. 1998b;252:49–63. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199809)252:1<49::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou A, Egginton S, Hudlicka O, Brown MD. Internal division of capillaries in rat skeletal muscle in response to chronic vasodilator treatment with α1-antagonist prazosin. Cell Tissue Res. 1998a;293:293–303. doi: 10.1007/s004410051121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.