Abstract

Understanding bladder afferent pathways may reveal novel targets for therapy of lower urinary tract disorders such as overactive bladder syndrome and cystitis. Several potential candidate molecules have been postulated as playing a significant role in bladder function. One such candidate is the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) ion channel. Mice lacking the TRPV1 channel have altered micturition thresholds suggesting that TRPV1 channels may play a role in the detection of bladder filling. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the role of TRPV1 receptors in controlling bladder afferent sensitivity in the mouse using pharmacological receptor blockade and genetic deletion of the channel. Multiunit afferent activity was recorded in vitro from bladder afferents taken from wild-type (TRPV+/+) mice and knockout (TRPV1−/−) mice. In wild-type preparations, ramp distension of the bladder to a maximal pressure of 40 mmHg produced a graded increase in afferent activity. Bath application of the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine (10 μm) caused a significant attenuation of afferent discharge in TRPV1+/+ mice. Afferent responses to distension were significantly attenuated in TRPV1−/− mice in which sensitivity to intravesical hydrochloric acid (50 mm) and capsaicin (10 μm) were also blunted. Altered mechanosensitivity occurred in the absence of any changes in the pressure–volume relationship during filling indicating that this was not secondary to a change in bladder compliance. Single-unit analysis was used to classify individual afferents into low-threshold and high-threshold fibres. Low threshold afferent responses were attenuated in TRPV1−/− mice compared to the TRPV1+/+ littermates while surprisingly high threshold afferent sensitivity was unchanged. While TRPV1 channels are not considered to be mechanically gated, the present study demonstrates a clear role for TRPV1 in the excitability of particularly low threshold bladder afferents. This suggests that TRPV1 may play an important role in normal bladder function.

Controlled micturition is initiated by bladder afferent nerves and depends on an integration of somatic and autonomic efferent mechanisms that coordinate bladder contraction and sphincter relaxation. Disruptions to these normal pathways can give rise to a number of lower urinary tract storage disorders, which may manifest themselves as overactive bladder symptom syndrome (OAB). Historically, research has centred on understanding efferent pathways; however, it is well recognized that afferent nerves are responsible for the initiation of voiding reflexes. It is becoming increasingly apparent that sensory mechanisms may hold the key to new therapeutic targets.

Afferent discharge from the bladder is conveyed by a dual innervation of hypogastric and pelvic afferent nerves (De Groat, 1987). Studies indicate that myelinated Aδ fibres are involved in normal micturition and small diameter unmylinated C-fibres are associated with painful sensations (Janig et al. 1991; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994a; Rong et al. 2004). Both mechanical and chemical stimuli can excite afferent nerves triggering micturition (Moss et al. 1990, 1997; Zagorodnyuk et al. 2006); however, a full understanding of the mechanisms involved in chemo- and mechanosensation is yet to be determined.

Several potential candidate molecules have been identified as playing a significant role in bladder function. Transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV1) ion channel was first cloned by Caterina et al. (1997). TRPV1 is a non-specific cation channel activated by heat, protons (Tominaga et al. 1998), vanilloids such as capsaicin the pungent ingredient found in chilli peppers, and endovanilloids such as anandamide (Zygmunt et al. 1999). The TRPV1 receptor is predominantly expressed in small diameter primary afferent neurones and was initially considered as an integrator for thermal and chemical noxious stimuli. However a growing body of evidence has led to the emergence of TRPV1 as a prominent participator in sensory transduction.

The presence of TRPV1 in the bladder was first detected in rats (Szallasi et al. 1993), and since this discovery many other studies have demonstrated the existence of TRPV1 on afferent nerve fibres (Szallasi et al. 1993; Avelino et al. 2002; Lazzeri et al. 2004) and smooth muscle cells of the lower urinary tract (Ost et al. 2002; Lazzeri et al. 2004). TRPV1 expression has also been located on urothelial cells of rodents (Birder et al. 2001) and has been shown to be functional on both nerve fibres and urothelium (Avelino & Cruz, 2006). Identification of TRPV1 in the urothelium is especially interesting as the urothelium has been shown to exhibit specialized sensory and signalling properties (Birder, 2001; Lazzeri, 2006).

There are many studies which report a role for TRPV1 in bladder inflammation and pain (Vizzard, 2000; Dinis et al. 2004); however, the role of TRPV1 in normal bladder function is more controversial. With the identification of TRPV1 on sensory structures of the bladder it seems reasonable to hypothesize that TRPV1 plays a major sensory role in normal bladder physiology. Absence of TRPV1 in mice has been shown to reduce the frequency of bladder reflex contractions and increase bladder capacity at the threshold for micturition (Birder et al. 2002). Clinical studies have also shown that administration of the TRPV1 agonist capsaicin to the bladder can induce hyperactivity in humans (Lecci et al. 2001). In both of these studies there is an apparent dysfunction of bladder sensory mechanisms.

Knockout studies investigating other visceral structures have suggested a role for TRPV1 in the detection of visceral distension. TRPV1−/− mice have been shown to exhibit blunted responses to jejunal and colorectal distension in vitro, while wild-type mice pretreated with the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine also evoked the same attenuation of afferent response (Rong et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2005). This raises the exciting possibility that TRPV1 may be involved in bladder mechanosensation.

The aim of this present study was to investigate the functional contribution of TRPV1 to bladder afferent signalling in vitro and to evaluate its effect on mechanosensation.

Methods

Animals

TRPV1 WT and KO mice with a genetic background of C57/BL6 were generated in GlaxoSmithKline (Harlow, UK). Trans-membrane domains 2–4 of the mouse VR1 gene (i.e. DNA encoding amino acids 460–555) were replaced by the neo gene (Davis et al. 2000). Mating pairs of TRPV−/− and TRPV1+/+ N1F1 littermates were obtained to generate separate colonies of TRPV1 WT and KO mice at the University of Sheffield according to the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. In the course of the study, genotyping was periodically performed to confirm the absence of TRPV1 gene in the KO mice. There were no overt differences in feeding behaviour, litter size, growth rate and body weight between WT and KO groups.

Six- to eight-week-old male TRPV1 knockout mice and wild-type animals were used in this study. Maintenance and killing of the animals followed principles of good laboratory practice in compliance with UK national laws and regulations. The mice were killed humanely by cervical dislocation.

Preparation and nerve recording

The whole pelvic region including surrounding tissues was dissected from the animal and placed in a recording chamber. The chamber was continually superfused with gassed (95% O2–5% CO2) Krebs–bicarbonate solution (composition, mm: NaCl 118.4, NaHCO3 24.9, CaCl2 1.9, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, glucose 11.7) at 35°C. The urethra was catheterized using a cannula attached to an infusion pump to enable distension of the bladder with saline. The dome was catheterized by a two-way cannula to enable recording of intravesical pressure and allow evacuation of fluid. The ureters were ligated to prevent leakage from the bladder. The afferent nerves were carefully dissected into fine branches and placed into a suction electrode for recording as previously described (Rong et al. 2002). The electrical activity was recorded by a neurolog headstage (NL100, Digitimer Ltd, UK), amplified (NL104) and filtered (NL125, band pass 300–4000 Hz) and captured by a computer via a power 1401 interface and spike2 software (version 5.14, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK).

Experimental protocols

The preparation was allowed an equilibration period of 30 min before any experimental protocol commenced. Control bladder distensions were always carried out using isotonic saline (NaCl, 0.9%) at a rate of 100 μl min−1 to a maximum pressure of 40 mmHg; at this point the infusion pump was stopped and rapid evacuation of the fluid occurred by opening the two way catheter in the dome to the atmosphere. This was repeated several times at intervals of 10 min to assess the viability of the preparation and reproducibility of the intravesical pressure and neuronal responses to distension. The afferent response to bladder distension were investigated in the TRPV1 KO and wild-type animals. Functional TRPV1 mediated afferent responses was assessed by applying 10 μm capsaicin and 50 mm HCl to the bath for 3 min.

The effect of bladder distension was assessed by varying the rate of filling from 50 μl min−1 to 200 μl min−1. To test the effect of capsazepine on distension induced activity, 10 μm capsazepine was applied to the bath and responses to bladder distension were compared in the presence of the vehicle and after exposure to the drug.

Data analysis

Whole nerve multifibre afferent nerve activity was quantified using a spike processor which counted number of action potentials crossing a preset threshold (Digitimer D130). Single-unit discrimination was performed offline using the spike sorting function of Spike2 software (version 5.14) in order to identify the individual single units in each preparation. A threshold level for spike counting was set at the peak of the smallest identifiable spike (at roughly twice the baseline noise level). Afferent activity was sampled at 25 000 Hz such that the 2.5 m period used to construct a spike template that encompassed both the positive and negative excursions of the action potential was approximately 62 data points. Individual spikes were classified to a particular template typically with < 10% variability in amplitude and > 60% of data points within the template boundary. Principal component analysis was used to display the spikes visually in three dimensions allowing overlapping waveforms to be identified and eliminated from the analysis. The total number of single units present within the bundles was used to normalize the whole nerve distension response so that discharge could be expressed as mean discharge per single unit. In addition, a sequential rate histogram for each single unit was constructed and the level of firing in the corresponding 1 s bin calculated at each pressure increment up to 40 mmHg, which was used to define individual stimulus–response functions. Low threshold afferents were defined as responding to pressures below 15 mmHg while units with thresholds above 15 mmHg were considered high threshold (Rong et al. 2002). Baseline afferent activity was obtained by averaging the discharge in the 60 s period immediately prior to treatment or distension. Peak responses were quantified (mean peak response in 10 s time period) after subtracting the baseline firing.

Afferent nerve discharge is expressed as impulses per second (imp s−1) for either the whole nerve activity or for the activity per fibre (imp s−1 fibre−1). Data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was carried out using a either a 2-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni post test where necessary or paired Student's t test and significance was set at P < 0.05.

Bladder compliance was gauged from the pressure–volume relationship during filling. Bladder volume was determined from the infusion rate and time from the start of infusion. Pressure was obtained from the output from the pressure transducer. Volume at 10 mmHg increments in pressure was used to construct pressure–volume curves, the slope of which is a reflection of compliance. Pressure–volume curves were compared in wild-type and TRPV1 knockout animals and in animals before and after capsazepine. The pressure–volume relationship was not linear and therefore to obtain an index for compliance we also determined the bladder volume at which bladder pressure increased to 40 mmHg.

Drugs

Capsaicin and capsazepine (Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK) were dissolved in ethanol (100%) as 10 mm stock solution and were diluted in isotonic saline (NaCl, 0.9%) and Krebs solution, respectively, to the required concentrations before use. The maximum final bath concentration of ethanol was 0.1%. Hydrochloric acid (Fisher scientific, Leicester, UK) was diluted in saline for intraluminal infusion. All inorganic salts were purchased from BDH (Poole, UK).

Results

Response to ramp distension

There was little spontaneous activity in the bladder afferent recordings with similar discharge rates in the TRPV1 knockout (0.2 ± 0.1 imp s−1 fibre−1) and wild-type mice (0.2 ± 0.04 imp s−1). Ramp distension caused an increase in afferent discharge with increasing intravesical pressure. However, the relationship between afferent discharge and pressure was nonlinear with afferent activity increasing markedly during the initial rise in intraluminal pressure (between 0 and 20 mmHg – phase 1), followed by a smaller increase as intraluminal pressure increased further (between 20 and 40 mmHg – phase 2) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Afferent response to bladder distension in the mouse.

A, representative sequential rate histogram of the afferent response to a control distension (with isotonic saline at a rate of 100 μl min−1). B, raw multiunit afferent nerve activity in response to ramp distension. C, increase in intravesical pressure due to infusion of saline. Note that two phases can clearly be identified, a first phase in which the pressure increases slowly and the afferent response increases rapidly and a second phase where there is a more rapid increase in intravesical pressure and a slower increase in afferent activity.

The effect of capsazepine

The effect of the TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine (CPZ, 10 μm) on distension-induced afferent activity was assessed by bath application of 10 μm capsazepine to bladders from wild-type mice (n = 10). Capsazepine caused a significant (P < 0.001, 2-way ANOVA) and reversible attenuation of the afferent response to distension when expressed as either whole nerve discharge or normalized per single unit (Fig. 2). At 40 mmHg the afferent discharge before drug application was 26.0 ± 3.2 imp s−1 and was reduced to 16.6 ± 2.9 imp s−1 after application (P < 0.002, Student's t test). No alteration in bladder compliance was observed after CPZ application.

Figure 2. The effect of capsazepine on afferent response to ramp distension.

A, whole nerve afferent response to distension before (control) and after application of 10 μm capsazepine in wild-type mice (P < 0.001 2-way ANOVA). B, the whole nerve response has been normalized to the number of single units in the afferent bundles (see Methods). The variability in the whole nerve responses arising because of the different number of single units that contribute to each nerve bundle is eliminated by this procedure making the statistical difference after treatment more robust (P < 0.001, 2-way ANOVA).

Acid and capsaicin sensitivity

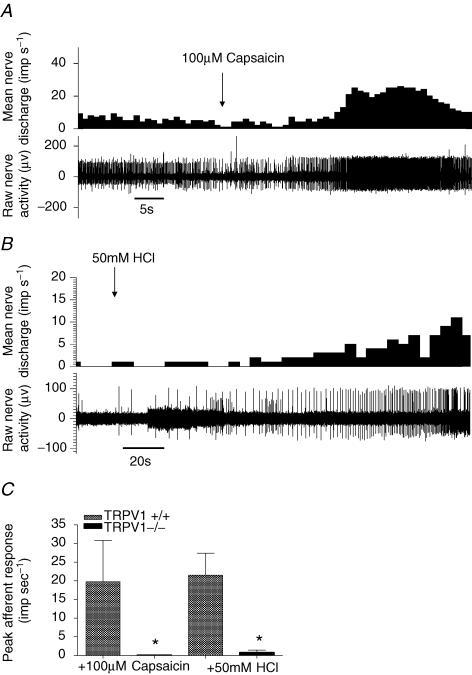

To confirm the absence of TRPV1 in the knockout animals and to assess the contribution of TRPV1 to proton and capsaicin sensitivity of the bladder afferents, 50 mm hydrochloric acid (HCl) and 100 μm capsaicin were infused for 3 min into the lumen of the bladder with the out-flow tap open to avoid distension. In wild-type mice, application of both HCl and capsaicin induced a robust excitatory afferent whole nerve response with a peak increase of discharge of 21.5 ± 5.9 imp s−1 and 19.8 ± 11.0 imp s−1, respectively. The response to acid and capsaicin was significantly attenuated in the TRPV1 knockout animals (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Effect of capsaicin and hydrochloric acid on bladder afferent activity.

A, representative trace showing a marked increase in baseline afferent discharge in the presence of 100 μm capsaicin in TRPV1+/+. B, representative trace showing response during intravesical application of 50 mm HCl in a wild-type preparation. C, bar graph showing the magnitude of the increase in afferent discharge in response to HCl and capsaicin in TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− mice (P < 0.05, t test).

Response to distension in TRPV1−/−

The response to distension was significantly attenuated in the TRPV1−/− mouse compared to the wild-type animal (P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. The response to ramp distension in TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− mice.

A, afferent response to increasing intravesical pressure. Whole nerve discharge is normalized to the number of single units in the afferent bundles (P < 0.001, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post test). B, pressure–volume curve during distension in the TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− mice. Note the curves are identical indicating that bladder compliance is not different in the TRPV1−/− mouse.

Compliance of TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− bladders

Compliance, defined as change in volume per unit change in pressure, was not different in the TRPV1 wild-type and TRPV1 knockout mice (Fig. 4B). Bladder compliance was nonlinear and decreased markedly with bladder filling but nevertheless the volume–pressure curves from the two groups of animals was superimposable.

Rates of distension

The role of the TRPV1 receptor in bladder mechanosensitivity was assessed using filling rates of 50 μl min−1 and 200 μl min−1. With each there was a graded increase in afferent activity. At 200 μl min−1 there was significantly higher afferent discharge than with 50 μl min−1 in both the wild-type and knockout bladders (P < 0.0001, 2-way ANOVA, Table 1). However, while the high filling rate response was significantly attenuated in the TRPV1−/− mice, the response at low filling rate was not significantly different. In contrast, bladder compliance as reflected in the volume necessary to increase pressure by 40 mmHg was not different with different filling rates or between knockout and wild-type.

Table 1.

Afferent response to distension and bladder volume at various filling rates in TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− mice

| Firing frequency at 40 mmHg (imp s−1) | Volume at 40 mmHg (μl) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 μl min−1 | 200 μl min−1 | 50 μl min−1 | 200 μl min−1 | |

| TRPV1+/+ | 11.8 ± 1.8*** | 22.7 ± 2.7*** | 320.9 ± 25.4 | 292.8 ± 22.7 |

| TRPV1−/− | 10.8 ± 1.9 | 15.7 ± 1.4*** | 383.8 ± 44.4 | 377.9 ± 29.4 |

P < 0.0001, 2-Way ANOVA

Single unit response characteristics

A total of 77 single fibres were characterized by their activation threshold in the wild-type mice and 50 in the knockouts (Table 2). Two types of fibre were identified in the whole nerve bundles. Low threshold units had distension thresholds < 15 mmHg and high threshold units had thresholds above this (Fig. 5). The cut off of 15 mmHg was chosen because this is the threshold used in previous studies and is around the level of the micturition threshold in the mouse (Rong et al. 2002; Igawa et al. 2004).

Table 2.

Summary of fibre types in TRPV1 wild-type and knockout mice

| TRPV1+/+ | TRPV1−/− | |

|---|---|---|

| Low threshold fibres | 62 (80.5%) | 43 (86.0%) |

| High threshold fibres | 15 (19.5%) | 7 (14%) |

| Total | 77 (100%) | 50 (100%) |

Figure 5. Single unit analysis of bladder afferent responses to distension.

A, representative traces of increased intravesical pressure, concurrent increase in afferent discharge and whole nerve spike rate histogram. Waveform analysis (see Methods) revealed 5 distinct single units that could be clearly separated using the Principle Component analysis function in Spike2 software (C). Individual spike shapes are coloured differently in the wavemark channel and presented in separate histograms in panel B. Overlaid action potentials are shown in the insets which illustrates the distinct amplitude and duration of these single units. Each inset represents a period of 2 ms. Note that each unit has a distinct threshold and response profile which is used to classify individual units into LT and HT afferents. In this example the lower 3 afferents were classified as LT and the upper 2 as HT.

The majority of fibres identified were low threshold units and the relative proportion of high to low threshold fibres was similar in both the knockout and wild-type animals (Fig. 6). However distension induced low threshold fibre activity was significantly lower in the knockouts compared to the wild-type mice. At a maximal distension (40 mmHg) low threshold unit afferent activity from the bladders of mutant mice was 40% lower than that of the wild-type low threshold fibre responses (12.8 ± 1.9, n = 62, in wild-type compared to 7.7 ± 0.9 in KO, n = 43). In contrast, there was no significant difference between the high threshold fibre responses to distension in knockout and wild-type animals (Fig. 6B). In wild-type animals 67% and 43% of low threshold afferents responded to capsaicin and HCl, respectively. In these experiments, none of the high threshold fibres responded to HCl and only 1 of the 15 responded to capsaicin.

Figure 6. Stimulus–response profile of low threshold (A) and high threshold (B) bladder afferents.

Note that the LT afferents have a blunted response profile in the TRPV1−/− mice compared to wildtype (P < 0.001, 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post test). The response profile of HT afferents is unchanged.

Discussion

The role of TRPV1 in bladder afferent function has not previously been investigated using direct electrophysiological techniques to assess changes in stimulus–response function as a consequence of deletion or pharmacological blockade of the channel. One previous study in the TRPV1 knockout used cystometry to indirectly address the role of afferent inputs to the micturition reflex and showed that TRPV1−/− animals have an increased bladder capacity and attenuated voiding contractions resulting in overflow incontinence in some cases. These changes in bladder function were suggested to result from reduced afferent input to micturition reflex pathways, a conclusion supported by the observation that the number of c-fos positive neurones in the sacral spinal cord following bladder filling was reduced in the TRPV1 knockout mouse (Birder et al. 2002). That these changes could have been secondary to altered bladder mechanics would seem unlikely in the light of the current observations. Here, we provide unequivocal evidence for a mechanosensory deficit in the TRPV1 knockout using direct recording of afferent impulses generated from the bladder of TRPV1 knockout and wild-type mice. Furthermore, this study is the first to investigate the relative contribution of TRPV1 to high and low threshold afferent fibre activation in response to bladder filling. In knockout models there is the potential for adaptive mechanisms to compensate for genetic alteration. In the present study we also used acute pharmacological blockade of the TRPV1 receptor and showed, similar to that seen with genetic deletion, an attenuated afferent response to bladder distension. This study therefore provides mechanistic insight into the way in which bladder mechanosensitivity is modulated by the TRPV1 channel.

TRPV1 receptor contributes to bladder afferent sensitivity to acid and capsaicin

About two-thirds of DRG neurones supplying the bladder express TRPV1 (Hwang et al. 2004). Capsaicin and proton sensitive currents have been described in DRG neurons supplying the rat bladder (Dang et al. 2005), and attenuation of the acid response by capsazepine implicates TRPV1 in acid sensing. There are clearly other potential contributing channels such as the acid sensing ion channels (ASICs) although their role in the bladder has not been determined. Activity at the level of the sensory neuronal soma is considered to reflect transduction mechanisms at the sensory nerve terminal. In the present study we have confirmed the role of TRPV1 in acid sensing using electrophysiological techniques to directly record from afferent fibres supplying the bladder. We clearly demonstrate that functional TRPV1 channels are required for bladder afferent sensitivity to intravesical acid. However, these data contrast with Birder et al. (2002) who demonstrated that micturition responses and c-fos expression in the sacral spinal cord of TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− mice in response to application of acetic acid were similar. They concluded that acid acts in the bladder via a TRPV1-independent mechanism. However, there are a number of differences between the present study and the previous investigation by Birder et al. (2002), most notably is the nature of the acid stimulus. In the present study afferent firing was examined in response to intraluminal perfusion with 50 mm HCl. This strongly acidic solution was chosen because it had been shown previously to evoke a robust response from acid-sensitive afferents supplying the gastrointestinal tract despite the diffusion barrier and potential buffering by the mucosal epithelium (Rong et al. 2004). A diffusion barrier across the urothelium was evident from the long latency (1–2 min) between infusion of the acid stimulus and evoked bladder afferent response which recovered with a similar time course following flushing the bladder with saline and returning to neutral pH. In the study of Birder et al. (2002), a weak (0.1%) acetic acid solution was used, which sensitized the micturition response and led to an increase in spinal c-fos levels, both of which were similar in the TRPV1 knockout and wild-type controls. While the assumption was that this was a sufficient stimulus to activate a proton response, it is not clear the extent to which this weak acid will give rise to a pH change at the level of the sensory terminal sufficient for activation of the TRPV1 receptors. Moreover, the conjugate base acetate, and other short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), has been shown to act via receptor mechanisms other than those that rely on proton gating (e.g. GPR43) (Nilsson et al. 2003). GPR43 is considered to be important for trans-epithelial signalling, in particular in the colon, where bacterial fermentation generates high luminal concentrations of SCFAs (Karaki et al. 2006). Although there are no reports of GPR43 in the bladder, Karaki et al. (2006) also demonstrated GPR43 expression on intestinal masts cells raising the possibility that acetate may cause mast cell degranulation, which in the bladder may cause afferent sensitization via histamine release (Theoharides et al. 1998; Sant & Theoharides, 1994). Indeed, the use of acetic acid to trigger bladder inflammation in models of bladder hypersensitivity could involve such a mast cell mediated mechanism. Thus, our data suggests a role for TRPV1 in acid sensing from the bladder, which contrasts with the previous study of Birder et al. (2002) but is consistent with other studies in the bowel in which sensitivity to HCl evoked a robust response from intestinal afferents that was attenuated in the TRPV1 knockout animal (Rong et al. 2004; Jones et al. 2005).

Acidification can affect the TRPV1 receptor by lowering the activation threshold of the channel, or increasing the potency of other TRPV1 stimulants such as capsaicin and temperature (Baumann & Martenson, 2000). This action may be a direct one, by increasing the open probability of the channel or an indirect one where acid acts at other ion channels to pretune the afferent nerves and potentiate the level of excitability. The latter might occur following acid acting on other proton-gated channels, e.g. ATP, ASICs, both of which are expressed on DRG neurones supplying the bladder (Zhong et al. 2003; Cockayne et al. 2005; Dang et al. 2005). It is likely that a host of ion channels and receptors determine excitability in these bladder afferents and therefore determine the ability to respond to protons. Indeed, this is the interpretation given below to explain the attenuated mechanosensitivity in the TRPV1 knockout since this channel is not considered to be mechanically gated. A similar potentiating interaction between receptors and ion channels may also underlie sensitivity to acid. However, because TRPV1 is gated directly by protons there is also the possibility that acid is acting directly. This may explain why mechanosensitivity is only blunted while the acid response is blocked. Moreover, the observation that acid causes an increase in afferent activity in the absence of any other stimulus may be evidence of a direct involvement of TRPV1 in bladder acid sensitivity.

The contribution of TRPV1 to bladder mechanosensation

The afferent response profile induced by distension observed in the present study was similar to that seen in previous in vitro afferent nerve preparations from the murine bladder (Rong et al. 2002). As distension commences there is an initial excitation of the afferent nerves despite a small rise in intraluminal pressure, followed by a continuing but slower increase in discharge as the intravesical pressure rises more dramatically. This can be seen in Fig. 1 and more clearly in Fig. 2 where discharge rate is plotted against pressure rather than time. These data can be explained by the activation of different subsets of afferent nerve fibres with low and high thresholds for activation. It has been proposed previously (Bahns et al. 1987; Habler et al. 1990; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994) that the initial increase in afferent discharge is attributed to low threshold mechanosensitive afferents which begin to fire at pressures that are within the physiological range of intravesical pressures observed during normal bladder filling. The micturition threshold in the mouse has been demonstrated to be around 13 mmHg (Igawa et al. 2004) and thus afferents responding to pressures around this level would likely contribute to the sensory input into reflex voiding. However, these afferents continue to encode beyond the micturition threshold, but the response begins to plateau. The vast majority of afferents recorded in the present study reflected this pattern of activity. High threshold afferents, in contrast were relatively sparse. These were defined, as in previous studies (Rong et al. 2002; Sengupta & Gebhart, 1994b), by activation thresholds above 15 mmHg and continued to encode pressure into the nociceptive range that in animals evokes pain-related behaviour. The graded increase in whole nerve afferent response therefore reflects the combined activity of these two populations of afferents with the low threshold afferents contributing the greatest.

The response profile to bladder distension was qualitatively similar in the TRPV1+/+ mice and the TRPV1−/− mice, with increasing intraluminal pressure giving rise to an increase in afferent discharge. However, the magnitude of these increases was different in the mutant animals, which showed a significantly blunted response to distension, especially at higher pressures, suggesting that the absence of the TRPV1 receptor results in a reduced afferent sensitivity to distension. This conclusion is supported by the observation that in wild-type mice the TRPV1 receptor antagonist capsazepine caused an attenuation of the response to distension which recovered upon washout of the antagonist. It is particularly striking that the decrease in afferent activity observed with the antagonist was similar to that recorded from the TRPV1−/− animals.

The contribution of TRPV1 to mechanosensitivity is comparable to a previous study of gastrointestinal afferents in vitro (Rong et al. 2004). In this study mechanosensitivity was attenuated but not abolished indicating that other mechanosensory mechanisms exist in the bladder and bowel that have as yet to be determined. The extent to which the observations in vitro reflect the whole animal is difficult to gauge. However, it is striking that in the pain behavioural studies of Jones et al. 2005, sensitivity to distension was reduced by about 40% in the TRPV1 knockout, similar to that in the present study. In contrast, the c-fos response to distension was completely absent in the Birder et al. (2002) study in which distension was applied in anaesthetized animals. However, spinal c-fos as an activity marker may not show the graded response profile seen in the previous pain behaviour and current electrophysiology study. A small decrease in sensory input may be sufficient to take the c-fos response below threshold and thus no longer detected. In this respect the cystometric analysis in TRPV1 undertaken by Birder et al. (2002) is revealing in that voiding responses were defective rather than absent consistent with attenuated sensory input to the micturition pathways. Irrespective of these differences in methodology (in vitro versus in vivo, awake versus conscious, electrophysiology versus pain behaviour, immunohistochemical detection of c-fos versus cystometry) there is unanimous agreement that TRPV1 contributes to mechanosensitivity. These data also suggest that TRPV1 contributes both to reflex voiding and to nociception. Since we could evaluate the contribution of TRPV1 to the activity of both low and high threshold mechanosensitivity we were able in the present study to address the question of the relative contribution to physiological versus pathophysiological sensory signalling.

Mechanosensitivity shows static and dynamic components that reflect the absolute level of stimulation and the rate of change, respectively. Both may rely on adaptive changes in the muscle such that greater accommodation occurs at lower rates of filling. A physiological level of distension would be one that is within the normal range of bladder volumes, but if such volume is delivered at a rate that exceeds normal bladder filling then it becomes unphysiological. It may also become pathophysiological if mechanisms that contribute to accommodation are disturbed in disease or if the sensitivity of the afferents gives rise to early micturition responses. We address the relative importance of rate of filling comparing a fast filling rate (200 μl min−1) with one that was much slower (50 μl min−1). Intriguingly, the increase in afferent discharge at low filling rates was not different in the knockout animals. That the response to distension was not different between TRPV1+/+ and TRPV1−/− mice when low rates of distension are used but was apparent with higher rates of distension might suggest that TRPV1 may be more relevant for pain behaviour rather than normal micturition. However, the single unit analysis revealed that the stimulus–response function of high-threshold afferents was not different in the TRPV1 knockout. It was the low threshold afferents whose response profile was blunted showing attenuated responses at higher levels of distension. Thus these low threshold afferents may contribute to nociceptive behaviour during supraphysiological levels (or rates) of distension which generate high levels of discharge. Since these afferents possess low thresholds for activation they may also contribute to micturition responses, especially if muscle function is altered to modify pressure, generation during filling, such as might occur in disease stales that lead to overactive bladder syndrome.

To assess the potential role of TRPV1 in bladder muscle function we assessed the pressure–volume relationship during bladder filling as an index of compliance. The curves were superimposable suggesting that compliance was similar in TRPV1−/− and TRPV1+/+ mice. Capsazepine also had no effect on bladder compliance. Thus, the difference in afferent sensitivity particularly at the higher filling rates suggests that the altered sensitivity is not secondary to changes in bladder muscle tone. Compliance was not assessed in other studies with the TRPV1 knockout animals, but there are reported observations that loss of TRPV1 leads to an increase in bladder capacity in rodents (Birder et al. 2002). However, capacity here was defined as the volume necessary to evoke a micturition response and so was influenced by reflex mechanisms. Moreover, bladders taken from TRPV1−/− mice had similar weights and were not morphologically different from bladders taken from TRPV1+/+ mice.

Afferent innervation of the bladder is transmitted via pelvic and hypogastric fibres with the cell bodies located in thoracolumbar and lumbrosacral DRG neurons, respectively. The differences observed between high and low threshold units in these experiments could represent a difference between the two distinct populations contained within mixed nerve bundles. Conversely Dang et al. (2005) demonstrated that the majority of neurones from the ganglia of lumbrosacral and thoracolumbar nerves respond to both capsaicin and protons, suggesting that there is little difference between the actions of TRPV1 on these two distinct populations. The number of responsive single units identified in both mutant and wild-type mice was not significantly different and classification into low and high threshold fibres indicated that the overall whole nerve composition was similar in the two groups, thus it is unlikely that a specific subset of afferents is inactive in the mutants.

How exactly TRPV1 participates in bladder mechanosensation is at present not clear. There are several potential explanations. Firstly, TRPV1 may be mechanically gated, but this is generally considered not to be the case. Secondly, TRPV1 may pre-tune the excitability of bladder afferents. This was the conclusion reached from an earlier study on the involvement of TRPV1 in intestinal mechanosensitivity on the basis of the known interactions between a variety of ion channels and receptors that regulate afferent excitability (Rong et al. 2004). An ion channel like TRPV1 that contributes to membrane excitability would reduce afferent sensitivity to various stimuli if it were absent. Thus our interpretation is that TRPV1 contributes to the general level of excitability and thus contributes to mechanosensitivity indirectly. This leaves the identity of the mechanosensor unknown. A possible candidate is the P2X3 receptor activated by ATP released during distension. Evidence to support such a mechanisms stems from the observation that bladder afferent responses to distension are attenuated in the P2X3 knockout (Rong et al. 2002; Vlaskovska et al. 2001), that the bladders of these animals have disrupted micturition responses (Cockayne et al. 2005) and that ATP is release from the urothelium during distension (Ferguson et al. 1997). It has been reported that in TRPV1−/− mice, release of ATP is significantly depressed (Birder et al. 2002) implying that the site of action of TRPV1 is the urothelium rather than sensory afferent terminal. However, this is a controversial area and a recent study in which bladder afferent sensitivity was assessed in the absence of the urothelium suggests that mechanosensitivity arises by a direct physical mechanism at the nerve terminal rather than via release of a chemical mediator from the urothelium (Zagorodnyuk et al. 2006).

Concluding remarks

This is the first study to report the functional significance of the TRPV1 receptor in urinary bladder mechanosensitivity by direct recordings from murine afferent nerves in vitro.

In wild-type preparations capsaicin and hydrochloric acid induced typical excitatory responses of the afferent fibres. In contrast, neither capsaicin nor HCl had significant excitatory effects in knockout preparations. This study demonstrates that a loss of capsaicin and proton sensitivity is concurrent with an attenuated afferent sensitivity to distension. Taken together, the present observations suggest TRPV1 plays an important role in bladder afferent nerve function.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Department of Urology, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, via a grant from the Robert Luff Foundation. We would also like to acknowledge GlaxoSmithKline (Harlow, UK) for providing the TRPV1 knockout mice.

References

- Avelino A, Cruz F. TRPV1 (vanilloid receptor) in the urinary tract: expression, function and clinical applications. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;373:287–299. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avelino A, Cruz C, Nagy I, Cruz F. Vanilloid receptor 1 expression in the rat urinary tract. Neuroscience. 2002;109:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00496-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahns E, Halsband U, Janig W. Responses of sacral visceral afferents from the lower urinary tract, colon and anus to mechanical stimulation. Pflugers Arch. 1987;410:296–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00580280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann TK, Martenson ME. Extracellular protons both increase the activity and reduce the conductance of capsaicin-gated channels. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-j0004.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder LA. Involvement of the urinary bladder urothelium in signaling in the lower urinary tract. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 2001;44:85–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder LA, Kanai AJ, De Groat WC, Kiss S, Nealen ML, Burke NE, Dineley KE, Watkins S, Reynolds IJ, Caterina MJ. Vanilloid receptor expression suggests a sensory role for urinary bladder epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13396–13401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231243698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder LA, Nakamura Y, Kiss S, Nealen ML, Barrick S, Kanai AJ, Wang E, Ruiz G, De Groat WC, Apodaca G, Watkins S, Caterina MJ. Altered urinary bladder function in mice lacking the vanilloid receptor TRPV1. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:856–860. doi: 10.1038/nn902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockayne DA, Dunn PM, Zhong Y, Rong W, Hamilton SG, Knight GE, Ruan HZ, Ma B, Yip P, Nunn P, Mcmahon SB, Burnstock G, Ford AP. P2X2 knockout mice and P2X2/P2X3 double knockout mice reveal a role for the P2X2 receptor subunit in mediating multiple sensory effects of ATP. J Physiol. 2005;567:621–639. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang K, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. Differential responses of bladder lumbosacral and thoracolumbar dorsal root ganglion neurons to purinergic agonists, protons, and capsaicin. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3973–3984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5239-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A, Sheardown SA. Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature. 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groat WC. Neuropeptides in pelvic afferent pathways. Experientia. 1987;43:801–813. doi: 10.1007/BF01945358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinis P, Charrua A, Avelino A, Yaqoob M, Bevan S, Nagy I, Cruz F. Anandamide-evoked activation of vanilloid receptor 1 contributes to the development of bladder hyperreflexia and nociceptive transmission to spinal dorsal horn neurons in cystitis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:11253–11263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2657-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DR, Kennedy I, Burton TJ. ATP is released from rabbit urinary bladder epithelial cells by hydrostatic pressure changes – a possible sensory mechanism? J Physiol. 1997;505:503–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.503bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habler HJ, Janig W, Koltzenburg M. Activation of unmyelinated afferent fibres by mechanical stimuli and inflammation of the urinary bladder in the cat. J Physiol. 1990;425:545–562. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SJ, Burette A, Rustioni A, Valtschanoff JG. Vanilloid receptor VR1-positive primary afferents are glutamatergic and contact spinal neurons that co-express neurokinin receptor NK1 and glutamate receptors. J Neurocytol. 2004;33:321–329. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044193.31523.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igawa Y, Zhang X, Nishizawa O, Umeda MIA, Taketo MM, Manabe T, Matsui M, Andersson KE. Cystometric findings in mice lacking muscarinic M2 or M3 receptors. J Urol. 2004;172:2460–2464. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000138054.77785.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janig W, Schmidt M, Schnitzler A, Wesselmann U. Differentiation of sympathetic neurones projecting in the hypogastric nerves in terms of their discharge patterns in cats. J Physiol. 1991;437:157–179. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC, 3, Xu L, Gebhart GF. The mechanosensitivity of mouse colon afferent fibers and their sensitization by inflammatory mediators require transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and acid-sensing ion channel 3. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10981–10989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaki S, Mitsui R, Hayashi H, Kato I, Sugiya H, Iwanaga T, Furness JB, Kuwahara A. Short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, is expressed by enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells in rat intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:353–360. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzeri M. The physiological function of the urothelium – more than a simple barrier. Urol Int. 2006;76:289–295. doi: 10.1159/000092049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzeri M, Vannucchi MG, Zardo C, Spinelli M, Beneforti P, Turini D, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. Immunohistochemical evidence of vanilloid receptor 1 in normal human urinary bladder. Eur Urol. 2004;46:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecci A, Carini F, Tramontana M, Birder LA, De Groat WC, Santicioli P, Giuliani S, Maggi CA. Urodynamic effects induced by intravesical capsaicin in rats and hamsters. Auton Neurosci. 2001;91:37–46. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss NG, Harrington WW, Tucker MS. Pressure, volume, and chemosensitivity in afferent innervation of urinary bladder in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;272:R695–R703. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.2.R695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss HE, Tansey EM, Milner P, Lincoln J, Burnstock G. Neuropeptide immunoreactivity and choline acetyltransferase activity in the mouse urinary bladder following inoculation with Semliki Forest Virus. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1990;31:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(90)90171-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson NE, Kotarsky K, Owman C, Olde B. Identification of a free fatty acid receptor, FFA2R, expressed on leukocytes and activated by short-chain fatty acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:1047–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ost D, Roskams T, Van Der Aa F, De Ridder D. Topography of the vanilloid receptor in the human bladder: more than just the nerve fibers. J Urol. 2002;168:293–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong W, Hillsley K, Davis JB, Hicks G, Winchester WJ, Grundy D. Jejunal afferent nerve sensitivity in wild-type and TRPV1 knockout mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:867–881. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong W, Spyer KM, Burnstock G. Activation and sensitisation of low and high threshold afferent fibres mediated by P2X receptors in the mouse urinary bladder. J Physiol. 2002;541:591–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sant GR, Theoharides TC. The role of the mast cell in interstitial cystitis. Urol Clin North Am. 1994;21:41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Characterization of mechanosensitive pelvic nerve afferent fibers innervating the colon of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1994a;71:2046–2060. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Mechanosensitive properties of pelvic nerve afferent fibers innervating the urinary bladder of the rat. J Neurophysiol. 1994b;72:2420–2430. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szallasi A, Conte B, Goso C, Blumberg PM, Manzini S. Characterization of a peripheral vanilloid (capsaicin) receptor in the urinary bladder of the rat. Life Sci. 1993a;52:PL221–226. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theoharides TC, Pang X, Letourneau R, Sant GR. Interstitial cystitis: a neuroimmunoendocrine disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:619–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard MA. Alterations in spinal cord Fos protein expression induced by bladder stimulation following cystitis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R1027–R1039. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaskovska M, Kasakov L, Rong W, Bodin P, Bardini M, Cockayne DA, Ford AP, Burnstock G. P2X3 knockout mice reveal a major sensory role for urothelially released ATP. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5670–5677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05670.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorodnyuk VP, Costa M, Brookes SJ. Major classes of sensory neurons to the urinary bladder. Auton Neurosci. 2006;126–127:390–397. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Banning AS, Cockayne DA, Ford AP, Burnstock G, Mcmahon SB. Bladder and cutaneous sensory neurons of the rat express different functional P2X receptors. Neuroscience. 2003;120:667–675. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt PM, Petersson J, Andersson DA, Chuang H, Sorgard M, Di Marzo V, Julius D, Hogestatt ED. Vanilloid receptors on sensory nerves mediate the vasodilator action of anandamide. Nature. 1999;400:452–457. doi: 10.1038/22761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]