Increasing patient choice is at the heart of current UK health service policy. At the end of life the focus is on eliciting patients' preferences for where end-of-life care is delivered, facilitating death at home when desired, and preventing crisis admissions in the last few days of life.1

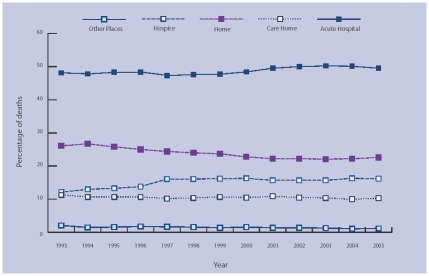

Less than one-fifth (18.5%) of deaths from all causes in England and Wales currently occur at home. More than half of all deaths (58.3%) occur in hospital, with evidence of a slow but steady decline in deaths occurring at home and a rising proportion of deaths in hospital. Figure 1 shows data for cancer deaths from 1993 to 2005 from the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Figure 1.

Place of death for cancer patients in England and Wales 1993–2005.

There is a mismatch between patients' preferred and actual place of death. Cross-sectional studies of patients,2,3 their informal carers,4 and the lay public5 reveal a majority preference for death at home: for most of us it is the natural place that death should come, reflecting who we are and what home and family means. Such preferences are not categorical, but are usually stronger or weaker leanings in one direction or another, qualified by uncertainty about the impact of future events.6

Conditions at three levels must be met for palliative care at home to be successful. Personal factors include the patient's desire to remain at home, their attitude towards death and dying, and the impact of their illness in terms of symptom management and the maintenance of personal dignity in the face of increasing weakness. Social factors include the presence of lay carers and their ability to cope both physically and emotionally. Structural factors include health and social care professionals' availability day and night, the reliability of services to provide a safety net in the face of unexpected events, and the proximity and availability of inpatient facilities. All these factors need to be taken into account. In 2004 the House of Commons Health Select Committee expressed concerns:

‘While we sympathise with and support the aspiration to allow patients to die at home if they choose, we question how realistic this objective really is at the present time. The option to die at home will only be realisable if there is a guarantee of 24-hour care and support, with the backup from appropriate specialists’.7

Patient preferences for place of death are not stable. Longitudinal4 and qualitative studies6 reveal preference for home death declines as illness progresses; patients increasingly opt for inpatient care as they become less well. Whether this reflects a resigned acceptance to save relatives and friends the burden of caring at home, or a positive decision seeking better care as an inpatient, or a combination of these and other factors remains unclear:8 insufficient longitudinal data are available at the present time.

Home deaths are not always characterised by the presence of close family and excellent support and symptom control: ‘home can be the best place or the worst place to die’.9 It seems very likely that recent changes in primary care, especially reduced personal continuity of care both in-hours and out-of-hours,10 have at times disadvantaged our dying patients. Recent initiatives such as the Gold Standards Framework11 and the Marie Curie Delivering Choice Programme (http://deliveringchoice.mariecurie.org.uk/) seek to address these issues and optimise primary palliative care.

At a population level, to interpret the proportion of home deaths as an indicator of good end-of-life care implies that deaths that take place in other locations are second best. This risks demonising hospital deaths as the result of family, professional or system failure. At an individual level this may result in the demoralisation of hospital-based healthcare professionals and leave relatives with a sense of guilt or failure for being unable to provide care at home up to the point of death. Many people who die in hospital are admitted for perfectly valid reasons: it is frequently far from clear at the time of admission that they are close to the end of life. Prognostication is notoriously difficult, especially in non-malignant illness. While people may receive excellent care at the end of life in hospital, there is room for improvement in staff knowledge, attitudes, communication, and team-working skills, and a need for greater flexibility towards patients' families. Recent initiatives such as the Liverpool Care Pathway for the dying12 seek to address many of these issues.

The NHS has recently invested £12 million in the End of Life Care Programme which is rolling out tools such as the Gold Standards Framework, the Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying, and the Preferred Place of Care document.13 Building on this programme, an NHS End of Life Care Strategy is currently under development to optimise care for all illness groups in all settings. These initiatives require rigorous evaluation using suitable outcome measures. At a population level, while the proportion of home deaths is limited as a measure of the quality of end-of-life care, it does have the advantage of being available for all deaths and free from the methodological difficulties that beset much palliative care research.14 Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and ONS national datasets are useful data sources, although HES can only provide information about deaths in hospital. The value of both sources could be substantially increased if record linkage between them was routinely available.

The NHS Connecting for Health IT programme might become a useful means of assessing end-of-life care quality, subject to suitable ethical controls. Days in hospital or numbers of admissions within the last 3 months of life, deaths within 2 days of admission from home, or within 7 days of admission from a care home have all been advocated as measures of quality of end-of-life care.

One alternative approach is to obtain the views of patients close to the end of life by means of interviews or questionnaires, but such studies encounter difficulties of identification, recruitment and attrition15 and are probably not practical outside academic research studies. A more fruitful approach for routine NHS use may be to seek the views of informal carers after death by interview or questionnaire. Such studies are also affected by identification and recruitment difficulties, and only obtain the retrospective views of proxies who are affected by the passage of time and grief.16

While no approach to measurement of the quality of end-of-life care is without its drawbacks, we advocate that an attempt be made to measure systematically the care provided in all settings in order to assess progress in improving end-of-life care for all. Each day in the UK 1500 people die. An annual postal survey of the next of kin of all people who died on a particular day 6 months previously could provide invaluable data.

Service initiatives on their own are unlikely to alter place of death greatly, since the factors influencing place of death are many and varied, and include powerful social and cultural factors.17 The real challenge therefore is to improve the quality of end-of-life care in all settings, wherever people spend their last weeks and days, and especially in the general wards of our hospitals which are increasingly the predominant place of death. Almost all health and social care professionals are to some extent involved in end-of-life care. This is predominantly a task for generalists, supported where appropriate by palliative care specialists. Death affects us all, both directly and indirectly: these are challenges to which we must rise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health. Building on the best: end of life care initiative. London: Department of Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend J, Frank A, Fermont D, et al. Terminal cancer care and patients' preference for place of death: a prospective study. BMJ. 1990;301(6749):415–417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6749.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gott M, Seymour J, Bellamy G, et al. Older people's views about home as a place of care at the end of life. Palliat Med. 2004;18(5):460–467. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm889oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinton J. Which patients with terminal cancer are admitted from home care? Palliat Med. 1994;8(3):197–210. doi: 10.1177/026921639400800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higginson I. Priorities and preferences for end of life care in England, Wales and Scotland. London: National Council for Palliative Care; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas C, Morris S, Clark D. Place of death: preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(12):2431–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.House of Commons Health Select Committee. Palliative care: Fourth report of session 2003–04. London: The Stationery Office; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higginson I, Sen-Gupta G. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2000;3(2):287–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkes CM. Home or hospital? Terminal care as seen by surviving spouses. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1978;28(186):19–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burt J, Barclay S, Marshall N, et al. Continuity within primary palliative care: an audit of general practice outof-hours co-operatives. J Public Health. 2004;26(3):275–276. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas K. The Gold Standards Framework in community palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care. 2006;10(3):113–115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellershaw J, Ward C. Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ. 2003;326(7379):30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pemberton C, Storey L, Howard A. The preferred place of care document: an opportunity for communication. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2003;9(10):439–441. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2003.9.10.19789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kendall M, Harris F, Boyd K, et al. Key challenges and ways forward in researching the ‘good death’: qualitative in-depth interview and focus group study. BMJ. 2007;334(7592):521–524. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39097.582639.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewing G, Rogers M, Barclay S, et al. Recruiting patients into a primary care based study of palliative care: why is it so difficult? Palliat Med. 2004;18(5):452–459. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm905oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McPherson C, Addington-Hall J. Judging the quality of care at the end of life: can proxies provide reliable information? Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(1):95–109. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes B, Higginson I. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):515–518. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]