Abstract

Chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the rat sciatic nerve increases the excitability of the spinal dorsal horn. This ‘central sensitization’ leads to pain behaviours analogous to human neuropathic pain. We have established that CCI increases excitatory synaptic drive to putative excitatory, ‘delay’ firing neurons in the substantia gelatinosa but attenuates that to putative inhibitory, ‘tonic’ firing neurons. Here, we use a defined-medium organotypic culture (DMOTC) system to investigate the long-term actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as a possible instigator of these changes. The age of the cultures and their 5–6 day exposure to BDNF paralleled the protocol used for CCI in vivo. Effects of BDNF (200 ng ml−1) in DMOTC were reminiscent of those seen with CCI in vivo. These included decreased synaptic drive to ‘tonic’ neurons and increased synaptic drive to ‘delay’ neurons with only small effects on their membrane excitability. Actions of BDNF on ‘delay’ neurons were exclusively presynaptic and involved increased mEPSC frequency and amplitude without changes in the function of postsynaptic AMPA receptors. By contrast, BDNF exerted both pre- and postsynaptic actions on ‘tonic’ cells; mEPSC frequency and amplitude were decreased and the decay time constant reduced by 35%. These selective and differential actions of BDNF on excitatory and inhibitory neurons contributed to a global increase in dorsal horn network excitability as assessed by the amplitude of depolarization-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+. Such changes and their underlying cellular mechanisms are likely to contribute to CCI-induced ‘central sensitization’ and hence to the onset of neuropathic pain.

Neuropathic pain, which is characteristically chronic and frequently intractable, is a major clinical problem. It can be initiated by nerve, brain or spinal cord injury (Kim & Chung, 1992; Kim et al. 1997) or by complications associated with diseases such as postherpetic neuralgia, stroke or diabetes (Chen & Pan, 2002).

Much of our understanding of neuropathic pain mechanisms comes from animal models in which experimentally induced peripheral nerve damage is used to initiate behaviours analogous to the signs of human neuropathic pain. It has been shown that injury to primary afferents can give rise to a global increase in excitability of the dorsal horn (Woolf, 1983; Laird & Bennett, 1993; Dalal et al. 1999; Kohno et al. 2003). Activation of microglia has also been implicated in this process of ‘central sensitization’ (Baba et al. 1999; Tsuda et al. 2005; Zhuang et al. 2005; Hains & Waxman, 2006). Our work, using chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve revealed a distinct pattern of altered synaptic drive to electrophysiologically defined populations of neurons in the substantia gelatinosa of the rat dorsal horn; putative excitatory ‘delay’ firing neurons received more excitation whereas putative inhibitory ‘tonic’ firing neurons received less (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006).

It has been postulated that substances released from damaged primary afferents and/or activated microglia (Coull et al. 2005) signal changes in the properties of dorsal horn neurons. Thus, any chemical instigator of ‘central sensitization’ should affect the dorsal horn in the same way as CCI.

The neurotrophin brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may be one such instigator. It is found in the central nerve terminals of primary afferents fibres (Apfel et al. 1996), and neuropathic pain-related behaviours, such as allodynia, are attenuated by blocking or sequestering BDNF (Zhou et al. 2000; Coull et al. 2005; Matayoshi et al. 2005). Also, following nerve injury, the expression of BDNF and its high-affinity receptor, TrkB, are up-regulated in the superficial dorsal horn (Cho et al. 1998; Michael et al. 1999; Dougherty et al. 2000; Ha et al. 2001; Fukuoka et al. 2001; Miletic & Miletic, 2002). Although elevated levels of BDNF have been shown to persist for several days following nerve injury (Cho et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 1999; Dougherty et al. 2000; Fukuoka et al. 2001), most studies examining its action on dorsal horn neurons have used acute, short-term exposures (Kerr et al. 1999; Garraway et al. 2003; Slack et al. 2004). It is yet to be determined whether long-term exposure of dorsal horn neurons to BDNF instigates the same enduring neuron type-specific changes as CCI as would be expected if it contributes to ‘central sensitization’.

To test this, we developed a defined-medium organotypic culture (DMOTC) of rat spinal cord that allowed us to expose neurons to elevated levels of BDNF for durations that would mimic the effects of CCI in vivo (Lu et al. 2006). Reports of some of our findings have appeared in abstract form (Lu et al. 2004; Smith et al. 2005).

Methods

All procedures were carried out in compliance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council for Animal Care and with the approval of the University of Alberta Health Sciences Laboratory Animal Services Welfare Committee.

Organotypic slice culture preparation

Organotypic cultures (DMOTCs) were prepared as previously described (Lu et al. 2006). Briefly, embryonic day 13 (E13) rat fetuses were delivered by caesarean section from timed-pregnant female Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River, Saint-Constant, QC, Canada) under deep isoflurane anaesthesia. The dam was subsequently killed with an overdose of intracardial chloral hydrate (10.5%). The entire embryonic sac was placed in chilled Hanks' balanced salt solution containing (mm): 138 NaCl, 5.33 KCl, 0.44 KH2PO4, 0.5 MgCl2–6H2O, 0.41 MgSO4–7H2O, 4 NaHCO3, 0.3 Na2HPO4, 5.6 d-glucose and 1.26 CaCl2. Individual rat fetuses were removed from their embryonic sacs and rapidly decapitated. The spinal cord from each fetus was isolated in the above solution and sliced into 275–325 μm transverse slices using a tissue chopper (McIlwain, St Louis, MO, USA). Only lumbar spinal cord slices with an intact spinal cord and two attached dorsal root ganglia were chosen and trimmed of excess ventral tissue and allowed to recover for 1 h at 4°C.

Each embryonic spinal cord slice was plated on a single glass coverslip (Karl Hecht, Sondheim, Germany) and attached with a clot of reconstituted chicken plasma (lyophilized, 0.2 mg% heparin; Cocalico Biologicals Inc., Stevens, PA, USA) and thrombin (200 units ml−1; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). Coverslips were then inserted into flat-bottomed tissue culture tubes (Nunc-Nalgene International, Mississauga, ON, Canada) filled with 1 ml of medium, and then placed into a roller drum rotating at 120 rotations per hour in a dry heat incubator at 36°C. The medium in the tubes was composed of 82% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum and 8% sterile water (all from Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). The medium was supplemented with 20 ng ml−1 NGF (Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Israel) for the first 4 days, and omitted thereafter. Antibiotic and antimycotic drugs (5 units ml−1 penicillin G, 5 units ml−1 streptomycin and 12.5 ng ml−1 amphotericin B; Gibco) were also included in the media during the first 4 days of culture. After 4 days in culture, DMOTC slices were treated with an antimitotic drug cocktail consisting of uridine, cytosine-β-d-arabino-furanoside (AraC), and 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (all at 10 μm) for 24 h to prevent the overgrowth of glial cells. During antimitotic treatment, the serum medium was progressively switched (first diluted 50 : 50 after 4 days, then completely exchanged after 5 days) to a defined, neurotrophin- and serum-free medium consisting of Neurobasal medium with N-2 supplement and 5 mm Glutamax-1 (all from Gibco). The medium within these tubes was exchanged regularly with freshly prepared medium every 3–4 days.

BDNF treatment

DMOTC slices were maintained in vitro for 3–4 weeks before recording to allow cultures to stabilize as previously reported (Lu et al. 2006). Also, the BDNF treatment schedule was chosen to parallel previous whole animal studies (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006) so exposure of dorsal horn neurons to BDNF would be congruent with the time course of BDNF elevation following nerve injury (see Fig. 1). Slices were treated after 15–21 days in vitro for a period of 5–6 days with 200 ng ml−1 BDNF (Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Isreal) in the serum-free medium described above. Thus, the oldest cultures studied were 37 days old. Cultures maintained for longer periods tended to deteriorate. The BDNF medium was exchanged on the third treatment day. Age-matched untreated DMOTC slices served as controls.

Figure 1. Time course of BDNF treatment parallels time course of nerve injury in vivo in a neuropathic pain model (CCI).

Timeline indicated for long-term BDNF DMOTC experiments, shown above, and previous CCI experiments (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006), shown below. Time indicated in postnatal days. The duration of treatment (which lasted 5–6 days) was chosen to correlate with reports of prolonged BDNF release following nerve injury (see Introduction). BDNF treatment was started either 15 or 21 days after the cultures were established and experiments were conducted after the treatment period.

Electrophysiology

For whole-cell recordings, DMOTC slices were superfused at room temperature (∼22°C) with 95% O2–5% CO2-saturated, external recording solution containing (mm): 127 NaCl, 6.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose, 2.5 CaCl2. DMOTC slices assumed a circular shape approximately 5 mm in diameter. Neurons selected for recording were located between 0.5 and 2 mm from the dorsal surface. They were patched under visual guidance using infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) optics.

Recordings were made using a NPI SEC-05L amplifier (npi Electronics, Tamm, Germany) in whole-cell discontinuous single-electrode voltage-clamp or current-clamp mode. Patch pipettes were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) to 5–10 MΩ resistances and filled with an internal recording solution containing (mm): 130 potassium gluconate, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 EGTA, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP, pH 7.2, 280–310 mosmol l−1.

Current–voltage (I–V) relationships were determined under voltage clamp using a range of 800 ms voltage commands which stepped holding potential from −140 to −20 mV in 10 mV steps. ‘Pseudo-steady state’ current was measured just prior to the termination of each voltage pulse. Input resistance was measured from the slope of the I–V relationship between −70 and −140 mV. Membrane excitability was quantified by examining discharge rates in response to a 1.5 s current ramp at a rate of 60 pA s−1 from a preset membrane potential of −60 mV. Cumulative latencies for the first, second, third and subsequent action potentials were plotted. The rheobase was determined as the minimum amount of current required to initiate firing of an action potential from a membrane potential adjusted to −60 mV.

Spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) were recorded for 3 min with the neuron clamped at −70 mV. At this voltage, Cl− mediated inhibitory events would be small outward currents generated by a 13 mV driving force from the estimated ECl of −83 mV. Miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) were recorded in a similar manner but in the presence of 1 μm tetrodotoxin (TTX; Alomone Laboratories, Jerusalem, Isreal) to block action potential-dependent neurotransmitter release. Blockade of action potential generation was confirmed by the cessation of action potential discharges in response to depolarizing current pulses. Also, the percentage of TTX-sensitive sEPSCs in each neuron (i.e. action potential-dependent events) was calculated from two 3 min recording periods in the absence and presence of TTX using the following equation: % TTX-sensitive sEPSCs = (total number of sEPSCs − total number of mEPSCs)/total number of sEPSCs.

Spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic potentials (sEPSPs) and action potentials were recorded at resting membrane potential in current-clamp mode. All data were acquired using Axon Instruments pCLAMP 9.0 software (Molecular Devices, Burlingame, CA, USA).

Data analysis, modelling and statistical testing

All data, except sEPSCs, mEPSCs and sEPSPs, were analysed using pCLAMP 9.0 software. Statistical comparisons were made with Student's unpaired t test or chi-squared (χ2) test as specified and appropriate, using GraphPad InStat 3.05 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Excitatory synaptic events were analysed using Mini Analysis software (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA, USA). Peaks of events were first automatically detected by the software according to a set of threshold criteria, and then all detected events were visually re-examined and accepted or rejected subjectively (refer to Moran et al. 2004 for complete details). To generate cumulative probability plots for both amplitude and interevent time interval, the same number of events (50–200 events acquired after an initial 1 min of recording) from each neuron was pooled for each neuron type, and input into the Mini Analysis program. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov two-sample statistical test (KS test) was used to compare the distribution of events between control and BDNF-treated groups.

All graphs were plotted and fitted using Origin 7.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) and statistical significance was taken as P < 0.05. Rise times and decay times of individual mEPSCs were fitted with a double exponential equation of the form:

Where y0 and x0 determine the position of the fit relative to the x and y axes, A is an amplitude term, τ1 and τ2 are time constants for the rise and decay of the mEPSC, respectively, and P is a value determining the relative importance of the two parts of the equation that was set to 1 for all fits and simulations. Fitting was carried out by repeated iterations until the χ2 value was unchanged for successive fits; this consistently yielded r2 values > 0.99. Manipulation of the decay time constant τ2 to assess its contribution to response amplitude (Fig. 7H–J) was done using a subroutine written in Microsoft Excel by Dr Gerda de Vries (Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Alberta). Analysis of mEPSC amplitude also involved redistributing event lists into 1 pA bins to produce histograms such as those illustrated in Figs 7E and F and 8E and F. Gaussian curve fitting protocols available in Origin 7.0 were used to identify peaks within the data. Fitting was carried out by repeating iterations until the χ2 value was not further reduced. For most experimental situations, best fits were obtained by fitting to three peak amplitudes as changing from two to three Gaussian fits produced large increases in χ2 values but adding a fourth component produced very little change (see insets to Figs 7E and F and 8E and F).

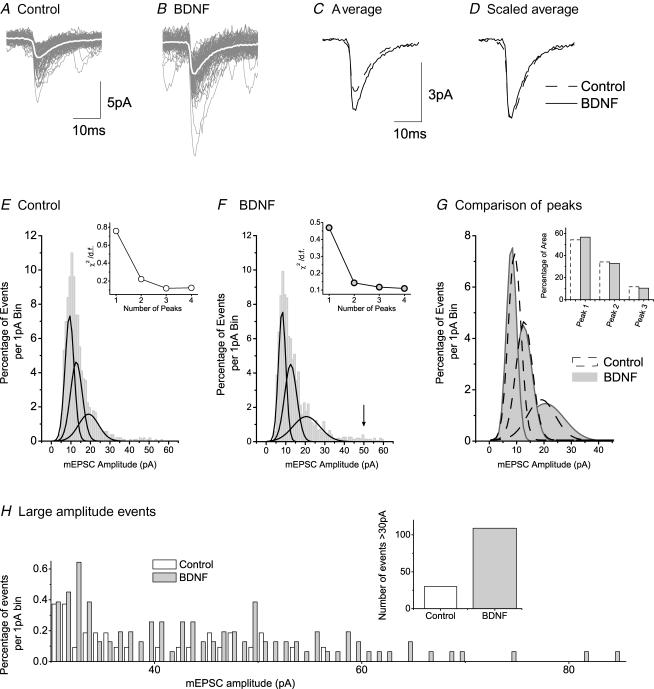

Figure 7. Analysis of the effects of BDNF on mEPSCs of tonic neurons.

A, superimposed recordings of 3 min of mEPSC activity in a control tonic neuron; average of events presented as superimposed white trace. B, similar superimposed recordings from a tonic neuron in a BDNF-treated culture. C, averaged events from the neurons illustrated in A and B. D, averaged events normalized to control size. Note marked increased rate of decay of current. E, distribution histogram (1 pA bins) for amplitudes of 1100 mEPSCs from control tonic neurons. Fit of the data to three Gaussian distributions represented by continuous lines. F, similar histogram and fit to three Gaussian functions for 877 mEPSCs from BDNF-treated neurons. Insets in E and F, graphs to show effect of number of Gaussian fits (peaks) on the value of χ2 divided by the number of degrees of freedom. G, superimposition of the three Gaussian peaks obtained in E with those obtained in F. H–J, modelled mEPSCs to represent the three peak Gaussian amplitudes obtained in E and F; dashed lines are for control events (from E), grey lines are for events in BDNF (from F) and dotted lines illustrate effect of a 35% reduction of τ2 on the control events.

Figure 8. Analysis of the effects of BDNF on mEPSCs of delay neurons.

A, superimposed recordings of 3 min of mEPSC activity in a control delay neuron; average of events presented as superimposed white trace. B, similar superimposed recordings from a delay neuron in a BDNF-treated culture. C, averaged events from the neurons illustrated in A and B. D, averaged events normalized to control size. Note no change in the rate of decay of current. E, distribution histogram (1 pA bins) for amplitudes of 1074 mEPSCs from control delay neurons. Fit of the data to three Gaussian distributions represented by black lines. F, similar histogram and fit to three Gaussian functions for 1554 mEPSCs from BDNF treated neurons; arrow points out small number of very large events that appear in BDNF. Insets in E and F, graphs to show effect of number of Gaussian fits (peaks) on the value of χ2 divided by the number of degrees of freedom. G, superimposition of the three Gaussian peaks obtained in E with those obtained in F. Inset, comparison of area under curves for the three peaks (normalized to total area under peaks). H, data for control and BDNF mEPSCs > 30 pA replotted and compared on the same axes. Inset, number of mEPSC events larger than 30 pA.

Calcium imaging

A single DMOTC slice was incubated for 1 h prior to imaging with 5 μm of the membrane-permeant acetoxymethyl form of the fluorescent Ca2+-indicator dye Fluo-4 (TEF Laboratories Inc., Austin, TX, USA). The conditions for incubating the dye were standardized across different slices to avoid uneven dye loading. After dye loading, the DMOTC slice was transferred to a recording chamber and perfused with external solution containing (mm): 131 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 1.3 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 25 d-glucose, and 2.5 CaCl2 (20°C, flow rate 4 ml min−1). Changes in Ca2+-fluorescence intensity evoked by a high K+ solution (20, 35, or 50 mm, 90 s application) were measured in dorsal horn neurons with a confocal microscope equipped with an argon (488 nm) laser and filters (20× XLUMPlanF1-NA-0.95 objective; Olympus FV300, Markham, Ontario, Canada). Full frame images (512 × 512 pixels) in a fixed xy plane were acquired at a scanning time of 1.08 s frame−1 (Ruangkittisakul et al. 2006). Selected regions of interest were drawn around distinct cell bodies and fluorescence intensity traces were generated with FluoView v. 4.3 (Olympus).

Drugs and chemicals

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). Fluo-4 AM dye was dissolved in a mixture of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 20% pluronic acid (Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) to a 0.5 mm stock solution and kept frozen until used. TTX was dissolved in distilled water as a 1 mm stock solution and stored at −20°C until use. TTX was diluted to a final desired concentration of 1 μm in external recording solution on the day of the experiment.

Results

Classification of neurons in the superficial dorsal horn of the cultures

In our previous studies of CCI-induced changes in dorsal horn, we recorded from substantia gelatinosa neurons that were classified on the basis of their action potential discharge pattern in response to depolarizing current steps from a preset membrane potential of −60 mV as ‘tonic’, ‘delay’, ‘phasic’, ‘transient’ or ‘irregular’ (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006; Fig. 2A. Because all five neuron types were also encountered in recordings made 0.5–2.5 mm from the dorsal edge of DMOTCs, this region corresponded well with the substantia gelatinosa of acute slices. As was seen with acute slices (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006), delay and tonic cells, which are putative excitatory and inhibitory interneurons, respectively, made up about 60% of the total population in the cultures (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Minimal changes in the proportion of each characterized neuronal cell type within the dorsal horn following BDNF treatment.

A, sample current-clamp recordings displaying different discharge firing patterns used to classify neurons within the dorsal horn. Three different recording traces at different current intensities are overlapped for each cell type. Membrane potential was set to −60 mV prior to injection of current pulses. Refer to text for details of characteristic features of each cell type. B and C, pie graphs showing percentage of each neuronal cell type identified in recordings from control DMOTC slices (n= 120) and BDNF treated DMOTC slices (n= 112). The only significant shift in the population was in the transient cell type group (χ2 test, *P < 0.05).

Apart from an increase in the proportion of ‘transient’ neurons (χ2 test, P < 0.05), there was no significant change in the contribution of each neuronal cell type (χ2 test, P values ranged from 0.41 to 0.77) to the total population following BDNF treatment (n= 120 for controls, n= 112 for BDNF; Fig. 2C).

Minimal effects of BDNF on passive membrane properties; small effect on active properties

Treatment of DMOTC with BDNF did not affect resting membrane potential (RMP) input resistance or the I–V relationship of any neuronal cell type (Table 1, t test, P values ranged from 0.18 to 0.95 for RMP, and from 0.19 to 0.81 for input resistance). This was similar to the situation with CCI in vivo. Moreover, as seen with CCI, BDNF failed to alter rheobase of ‘tonic’, ‘delay’, ‘phasic’ or ‘transient’ neurons in DMOTC (Table 1, t test, P > 0.5). Only ‘irregular’ neurons had a significantly lower rheobase versus control (t test, P < 0.05). Excitability was evaluated further by examining the firing rate in response to a 60 pA s−1 depolarizing current ramp. Firing rate was expressed as the cumulative latency to each action potential spike (Fig. 3). Under these conditions, only ‘delay’ neurons appeared to show a slight increase in excitability following prolonged BDNF exposure (Fig. 3B). Although the data only attained statistical significance at the most positive excursions of the current ramps, its possible importance cannot be ignored as ‘delay’ neurons tended to display bursts of spontaneous action potentials following BDNF treatment (see Fig. 9).

Table 1.

Comparison of membrane properties between control and BDNF-treated DMOTC slices

| RMP (mV) | Rinput (MΩ) | Rheobase (pA) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonic | |||

| Control | −51.79 ± 1.66 (29) | 419.22 ± 36.02 (28) | 29.67 ± 2.56 (30) |

| BDNF | −51.95 ± 1.70 (21) | 435.62 ± 56.31 (22) | 32.73 ± 4.93 (22) |

| Delay | |||

| Control | −47.34 ± 1.70 (38) | 319.83 ± 27.09 (37) | 73.56 ± 6.21 (45) |

| BDNF | −50.61 ± 1.75 (36) | 383.68 ± 39.93 (39) | 70.38 ± 8.24 (39) |

| Irregular | |||

| Control | −47.37 ± 2.16 (27) | 299.28 ± 43.20 (27) | 75 ± 9.98 (29) |

| BDNF | −47 ± 2.87 (21) | 326.74 ± 30.21 (21) | 49.32 ± 5.85* (22) |

| Phasic | |||

| Control | −44 ± 3.93 (7) | 371.12 ± 94.11 (6) | 44.29 ± 7.19 (7) |

| BDNF | −49.88 ± 2.87 (8) | 411.61 ± 73.11 (9) | 46.67 ± 6.01 (9) |

| Transient | |||

| Control | −46.17 ± 7.1 (6) | 301.13 ± 86.44 (9) | 102.78 ± 19.82 (9) |

| BDNF | −54.06 ± 2.70 (16) | 270.22 ± 41.61 (17) | 93 ± 8.92 (20) |

Values expressed as mean ±s.e.m.n values in brackets. For Student's unpaired t test

P < 0.05.

Figure 3. Minimal effects of BDNF membrane excitability.

Membrane excitability was measured as the cumulative latency of action potential discharges in response to a depolarizing current ramp from −60 mV. Top panels show sample records of a typical response of tonic, delay, irregular, phasic and transient cells to a 60 pA s−1 current ramp injection for 1.5 s. With the exception of transient cells, all cell types discharged ≥ 3 spikes in response to the current ramp. Lower panels are graphs of cumulative latency against spike number for each cell type. Not all cells produced the same number of action potential spikes during ramps. For example in A, of the 27 tonic cells examined only 5 of them fired 15 action potentials. The mean cumulative latencies for each spike number therefore have different sample sizes. A, for tonic cells, n= 5–27 for controls, n= 11–22 for BDNF. B, for delay cells, n= 6–27 for controls, n= 10–32 for BDNF. C, for irregular cells, n= 5–18 for controls, n= 5–19 for BDNF. D, for phasic cells, n= 5–7 for controls, n= 5–9 for BDNF. E, for transient cells, n= 3 for controls, n= 4 for BDNF. The only increase in excitability after BDNF treatment was observed in delay cells (t test, *P < 0.05). In some cases, error bars indicating s.e.m. are smaller than the symbols used to plot the data.

Figure 9. Effect of BDNF on spontaneous activity of tonic and delay neurons.

Spontaneous activity was measured as the number of depolarizations or action potential discharges at resting membrane potential in current-clamp mode. The mean number of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic potentials (sEPSPs) and spontaneous action potentials generated from sEPSPs are shown for tonic (A and B, respectively) and delay neurons (C and D, respectively). For tonic neurons, n= 36 for controls, n= 15 for BDNF. For delay neurons, n= 35 for controls, n= 27 for BDNF. E and F, sample 2 min recording of spontaneous activity from a control (E) and BDNF-treated (F) delay neuron. Lower panels show on an expanded time scale a large sEPSP generating an action potential. Note under long-term BDNF treatment conditions, the probability of a large sEPSP generating a burst of action potentials is greater. G, percentage of cells in the tonic and delay group firing a burst of action potentials. White bars indicate controls and grey bars indicate BDNF-treated neurons.

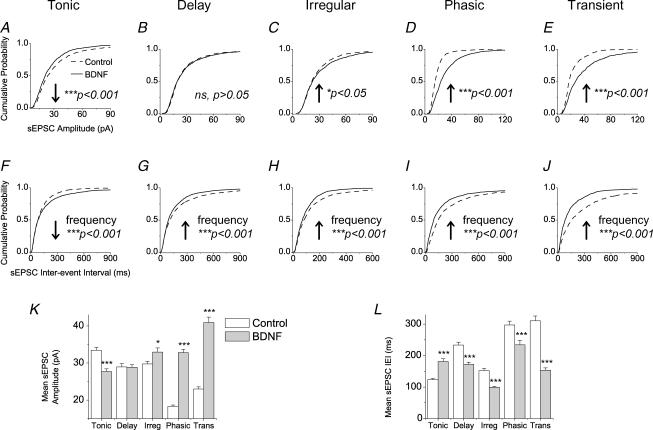

Effects of BDNF on sEPSCs

CCI produces a specific pattern of changes in excitatory synaptic transmission in the substantia gelatinosa (Table 2); different changes are seen in different cell types. In particular, excitatory synaptic drive to putative inhibitory tonic cells is decreased and that to putative excitatory delay cells is increased. If BDNF is involved in the instigation of such changes, it should alter spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) in a neuron type-specific pattern in a similar way to CCI. Effects of BDNF on sEPSC amplitude are illustrated in Fig. 4A–E, and effects on interevent interval (the reciprocal of frequency) are illustrated in Fig. 4F–J. As shown, BDNF reduced the amplitude and frequency of sEPSCs in ‘tonic’ neurons (Fig. 4A and F). Sample recordings illustrating BDNF's effects on sEPSCs of ‘tonic’ neurons are shown in Fig. 6D. By contrast, BDNF increased the frequency of sEPSCs in ‘delay’ neurons but did not affect their amplitude (Fig. 4B and G). Sample recordings illustrating the effect of BDNF on sEPSCs of ‘delay’ neurons are shown in Fig. 6E.

Table 2.

Summary of comparison between sEPSCs and mEPSCs following chronic constriction nerve injury (CCI) and long-term BDNF exposure.

| Tonic | Delay | Irregular | Phasic | Transient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sEPSC amplitude | |||||

| CCI | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| BDNF | ↓ | ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| sEPSC frequency | |||||

| CCI | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| BDNF | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| mEPSC amplitude | |||||

| CCI | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | nd | ↑ |

| BDNF | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ |

| mEPSC frequency | |||||

| CCI | ↓ | ↑ | ↔ | nd | ↑ |

| BDNF | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ |

Data for changes induced by CCI from Balasubramanyan et al. (2006). ↑ indicates a significant increase compared to control; ↓ indicates a significant decrease compared to control; ↔ indicates no change compared to control and nd indicates not determined because n values were too low.

Figure 4. Effects of BDNF on amplitude and interevent interval of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs).

A–E, cumulative probability plots for sEPSC amplitude. The first 50 events following the 1st minute of recordings from each cell were pooled in order to construct cumulative distribution plots, except for phasic and transient cells where the first 200 or 100 events following the 1st minute of recording were taken, respectively. A, tonic cells; 1450 events from control DMOTC slices, 1950 events from BDNF-treated DMOTC slices. B, delay cells; 1900 events for controls, 1100 events for BDNF. C, irregular cells; 1350 events for controls, 1100 events for BDNF. D, phasic cells; 1356 events for controls, 1670 events for BDNF. E, transient cells; 800 events for controls, 800 events for BDNF. An equal number of BDNF-treated transient cells as controls were chosen at random to analyse sEPSC events. P values derived from the KS test indicated on graphs. F–J, cumulative probability plots for sEPSC interevent interval (IEI). P values derived from the KS test indicated on graphs. K and L, effects of BDNF on mean amplitude (K) and IEI (L) of sEPSC events. The same events used to construct cumulative probability plots were used, so the same n values apply. For Student's unpaired t test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

Figure 6. Effects of BDNF on the action potential-dependent (TTX-sensitive) sEPSCs population.

A–B, comparison of sEPSCs to mEPSCs for controls. Comparison of mean amplitudes (A) and mean interevent intervals, IEI (B) are shown. Cross-hatched bars indicate values for sEPSCs and horizontal lined bars indicate values for mEPSCs. C, the percentage of TTX-sensitive sEPSCs was calculated as the number of mEPSCs subtracted from the total number of sEPSCs over the total sEPSCs for each cell. The mean percentages are shown for controls, white bars, and the BDNF-treated group, grey bars. For Student's unpaired t test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate s.e.m.D and E, sample recording traces from tonic (D) and delay (E) cells under control and long-term BDNF exposure conditions. Sample mEPSC recording traces were from the same cell represented in the above sample sEPSC recording trace.

BDNF also increased the amplitude and frequency of sEPSCs in ‘irregular’ (Fig. 4C and H), ‘phasic’ (Fig. 4D and I) and ‘transient’ (Fig. 4E and J) neurons. All changes were significant according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnoff two-sample test (KS test, P values presented in the figures).

Further statistical analysis by means of a parametric t test of all data sets was also applied (Fig. 4K and L). The trends of changes of sEPSC amplitude and interevent interval identified in the KS-test were also apparent from the t test.

Thus, BDNF did not produce identical changes in the synaptic excitation of all neuron groups, but rather induced neuron type-specific effects. ‘Tonic’ neurons received reduced spontaneous excitatory synaptic activity and all other neuron types, ‘delay’, ‘irregular’, ‘phasic’ and ‘transient’ neurons, generally displayed increased synaptic activity. This pattern of BDNF-induced changes in sEPSCs across all cell types was quite similar to that produced by CCI in vivo (Table 2). The correlation was particularly clear for sEPSC frequency; CCI and BDNF increased frequency in all cell types except tonic cells where both produced a decrease.

Effects of BDNF on mEPSCs

Miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) represent the action potential independent release of neurotransmitter (Colomo & Erulkar, 1968). To further characterize the changes in synaptic excitation induced by BDNF, mEPSCs were recorded in the presence of 1 μm TTX and analysed in a similar manner to sEPSC events.

The effects of BDNF on mEPSC amplitude are illustrated in Fig. 5A–E, and its effects on interevent interval are illustrated in Fig. 5F–J. Similar to its action on sEPSCs, BDNF reduced the amplitude and frequency of mEPSCs in ‘tonic’ neurons (Fig. 5A and F). Sample recordings illustrating BDNF-induced decreases in mEPSCs on ‘tonic’ neurons are shown in Fig. 6D. Conversely, long-term BDNF exposure increased the amplitude and frequency of mEPSCs in ‘delay’ neurons (Fig. 5B and G). Sample recordings illustrating BDNF-induced increases in mEPSCs on ‘delay’ neurons are shown in Fig. 6E.

Figure 5. Effects of BDNF on amplitude and interevent interval of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs).

A–E, cumulative probability plots for mEPSC amplitude. The first 50 events following the 1st minute of recordings from each cell were pooled in order to construct cumulative distribution plots. A, tonic cells; 1100 events from control DMOTC slices, 877 events from BDNF-treated DMOTC slices. B, delay cells; 1074 events for controls, 1554 events for BDNF. C, irregular cells; 700 events for controls, 800 events for BDNF. D, phasic cells; 303 events for controls, 300 events for BDNF. E, transient cells; 300 events for controls, 300 events for BDNF. An equal number of BDNF-treated transient cells as controls were chosen at random to analyse mEPSC events. P values derived from the KS test indicated on graphs. F–J, cumulative probability plots for mEPSC interevent interval (IEI). P values derived from the KS test indicated on graphs. K and L, effects of BDNF on mean amplitude (K) and IEI (L) of mEPSC events. The same events used to construct cumulative probability plots were used, so the same n values apply. For Student's unpaired t test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

In addition, BDNF reduced the amplitude and frequency of mEPSCs in ‘irregular’ neurons (Fig. 5C and H), reduced the amplitude but increased the frequency of mEPSCs in ‘phasic’ neurons (Fig. 5D and I) and increased both the frequency and amplitude in ‘transient’ neurons (Fig. 5E and J). All changes mentioned were significant and the P values from KS tests are presented in the figures. The results from t tests on the same data sets are in agreement with the conclusions from the KS test (Fig. 5K and L). As was seen with sEPSCs, the pattern of the action of BDNF on mEPSCs across all cell types was similar to that seen with CCI in vivo (Table 2).

BDNF-induced alterations in the frequency of presynaptic action potentials does not account for changes in sEPSCs of tonic and delay neurons

The sEPSC population is composed of synaptic events generated in response to presynaptic action potentials, as well as mEPSCs resulting from action potential-independent release. TTX significantly reduced the mean sEPSC amplitude (Fig. 6A, t test, P < 0.001) and produced the expected increase in interevent interval (Fig. 6B, t test, P < 0.001) in all neuron types.

BDNF-induced changes in the mEPSC population (Fig. 5) may not be solely responsible for the changes in sEPSCs (Fig. 4). We cannot exclude the possible contribution of changes in presynaptic action potential activity. This would alter the proportion of action potential-dependent synaptic events that are removed by the addition of TTX.

The observed decrease in sEPSC frequency observed in ‘tonic’ neurons with chronic BDNF treatment (Fig. 4F) could not be accounted for by a decrease in action potential-dependent events as the percentage of TTX-sensitive sEPSCs was increased (Fig. 6C, t test, P < 0.05). Sample recordings illustrating this effect of BDNF on relative sEPSC and mEPSC frequency are shown in Fig. 6D.

In ‘delay’ neurons, an increase in action potential-dependent release is unlikely to contribute to the observed increase in sEPSC frequency (Fig. 4G) since the percentage of TTX-sensitive sEPSCs decreased significantly with BDNF treatment (Fig. 6C, t test, P < 0.05). Sample recordings illustrating this effect of BDNF on relative sEPSC and mEPSC frequency are shown in Fig. 6E. Thus, the increased frequency of sEPSCs in ‘delay’ neurons (Fig. 4G) is most likely attributable to an increase in mEPSC frequency (Fig. 5G) and thus perhaps to changes in the release process.

In the case of ‘irregular’ neurons, BDNF increased the frequency of sEPSCs but decreased the frequency of their corresponding mEPSCs. Thus, an increase in the action potential-dependent events is mainly responsible for the increase in synaptic activity in these neuron cell types.

Lastly for ‘phasic’ and ‘transient’ neurons, there was no change in the percentage of TTX-sensitive sEPSCs with BDNF treatment (t test, P > 0.1). Since mEPSC frequency increased (Fig. 5I and J), it is possible that this, as well as an increase in action potential-dependent events, occurred in both cell types.

Further analysis of the mechanism of action of BDNF on tonic cells

Since tonic and delay cells comprise ∼60% of the neurons studied, and they likely represent inhibitory and excitatory neurons, respectively, mEPSC data from these two cell types were analysed more thoroughly.

Besides the reduction in mEPSC amplitude and frequency (Fig. 5A and F), BDNF reduced the time constant for mEPSC decay (τ2) by 35%. τ2 = 10.5 ± 0.43 ms (n= 1151) for control and 6.8 ± 0.28 ms (n= 631) for mEPSCs recorded after BDNF treatment (t test, P < 0.0001). Superimposed events from a typical control ‘tonic’ neuron and from another neuron from a BDNF-treated culture are shown in Fig. 7A and B. The white traces show superimposed average data from the two cells and these are compared in Fig. 7C. The scaled averages presented in Fig. 7D emphasize the increased rate of mEPSC decay in ‘tonic’ neurons from BDNF-treated cultures.

Three populations of mEPSC amplitudes of 12.1 ± 0.28, 19.7 ± 2.22 and 35.7 ± 7.38 pA were seen in control ‘tonic’ cells (Fig. 7E). These may reflect three different populations of vesicles in presynaptic terminals, different sizes of vesicles in different types of afferents, i.e. various intraspinal inputs such as primary afferents or local interneurons, or different populations of terminals at different distances from the site of recording. Three populations of mEPSC amplitude were also seen in BDNF-treated neurons (Fig. 7F) but these had smaller peak amplitudes at 7.3 ± 0.19, 10.9 ± 1.19 and 19.4 ± 2.35 pA. The insets to Fig. 7E and F show that fitting with three peaks produced the optimal reduction in χ2 (see Methods). Figure 7G shows a replot of the three Gaussian distributions of mEPSC amplitude from control and BDNF ‘tonic’ cells for comparison.

The apparent leftward shift in the three distributions raised the possibility that the reduction in time constant for mEPSC recovery contributed to the observed decrease in amplitude. To test this, we modelled three different mEPSCs using two exponential equations (Fig. 7I–J; see Methods). We used the mean value of τ2 as 10.5 ms and modelled the event amplitudes to represent the three peak mEPSC amplitudes seen in control neurons (Figs 7E and G). We next modelled mEPSCs based on the three peak amplitudes for events in BDNF-treated neurons using the reduced mean value of 6.8 ms for τ2. Lastly, we remodelled the control events using the τ2 value of 6.8 ms from events acquired in BDNF. Since this increase in decay rate produced only slight reductions in the calculated amplitudes of peaks 1, 2 and 3, a decrease in the decay time constant τ2 for mEPSC decay cannot account for the substantially reduced peak amplitudes seen in BDNF-treated cells; other pre- or postsynaptic mechanisms must contribute to this effect.

Further analysis of the mechanism of action of BDNF on delay cells

Unlike ‘tonic’ cells, the overall τ for recovery of mEPSC amplitude was unchanged in ‘delay’ cells (control τ= 10.73 ± 0.55 ms, n= 766; BDNF τ= 9.5 ± 0.82 ms, n= 1177; t test, P > 0.2). Superimposed events from a typical control and a typical BDNF-treated ‘delay’ neuron are shown in Fig. 8A and B. Figure 8C shows superimposed average data from these cells and scaled averages are presented in Fig. 8D.

As with ‘tonic’ cells, three populations of mEPSC amplitude were identified in control ‘delay’ cells by fitting Gaussian curves to binned histogram data. These appeared at 9.26 ± 1.51, 12.7 ± 9.0 and 19.0 ± 12.3 pA in control ‘delay’ cells (Fig. 8E) and at very similar amplitudes (8.14 ± 0.24, 12.5 ± 1.38 and 20.5 ± 4.3 pA) in BDNF-treated cells (Fig. 8F). Insets to Fig. 8E and F show optimized χ2 values for using three peaks to fit the data. Figure 8G is a replot of the distributions for comparison between control and BDNF-treated cells. Since overall mEPSC amplitude is increased in ‘delay’ cells (Fig. 5B), we tested whether changes in the number of events contributing to each of the three distributions could explain this increase. This was done by measuring the area under the Gaussian curves in Fig. 8G and expressing the results as a percentage of the total area (Fig. 8G inset). Surprisingly, similar proportions of the total events made up each of the three peaks under control and BDNF-treated conditions. However, further inspection of the histogram data obtained from BDNF-treated cells revealed a new population of very large events (indicated by arrow in Fig. 8F). Whereas only 30 events in the control data had amplitudes > 30 pA, 106 events in data from BDNF-treated cells fell into this category. The appearance of this new population of large events is emphasized by the presentation of data for mEPSCs > 30 pA in Fig. 8H. Although few events appear in this group, those that do, have large amplitudes. Thus, the emergence of a new group of large mEPSC amplitude events in BDNF may have a noticeable effect on overall mEPSC amplitude.

Alterations in synaptic activity can affect spontaneous action potential activity of dorsal horn neurons

If BDNF-induced changes in spontaneous synaptic activity are responsible for the overall increased excitability of the dorsal horn that follows CCI (Dalal et al. 1999) one would also expect to observe changes in spontaneous action potential activity in neurotrophin-treated cultures.

As would predicted from the sEPSC data (Fig. 4A and F), long-term BDNF treatment significantly reduced the mean number of sEPSPs per minute in ‘tonic’ neurons (Fig. 9A, t test, P < 0.05). More importantly however, the mean number of spontaneous action potentials generated from these sEPSPs significantly decreased following BDNF treatment (Fig. 9B, t test, P < 0.01). Therefore, long-term BDNF treatment significantly reduced the spontaneous firing of ‘tonic’ neurons.

There was also the anticipated significant increase in the number of sEPSPs per minute in ‘delay’ neurons following BDNF treatment (Fig. 9C, t test, P < 0.05). The mean number of spontaneous action potentials observed during the recording period also increased but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 9D, t test, P > 0.1). However, there was a change in the pattern of spontaneous action potential activity following BDNF treatment. A typical sEPSP triggering a single action potential in a control ‘delay’ neuron is illustrated in Fig. 9E. However in BDNF-treated cultures, sEPSPs often produced bursts of three to four action potentials in ‘delay’ neurons (Fig. 9F). There was a 15% increase in the number of ‘delay’ neurons that displayed such bursts following long-term BDNF exposure (Fig. 9G). A low percentage of control ‘tonic’ neurons displayed bursting behaviour but the percentage did not change following BDNF treatment. Therefore, long-term BDNF treatment selectively increased the spontaneous bursting activity of ‘delay’ neurons.

Enhanced overall excitability of BDNF-treated DMOTC slices

BDNF-induced increased burst firing of ‘delay’ cells and reduced firing of ‘tonic’ cells would only be expected to increase overall dorsal horn network excitability if ‘delay’ cells are excitatory and ‘tonic’ cells are inhibitory. Although this idea is generally well accepted, we do not know whether these effects, seen in 60% of the neuronal population, are sufficient to generate a global increase in dorsal horn excitability. BDNF also has effects on ‘phasic’, ‘transient’ and ‘irregular’ cells, all of which have undefined function. It is possible therefore that the changes in tonic and delay cells described above are insufficient to produce an overall excitatory effect. We therefore used confocal Ca2+ imaging techniques (Ruangkittisakul et al. 2006) to monitor the responses of both control and BDNF-treated DMOTC slices to depolarizing stimuli of varying strength (20, 35, or 50 mm K+ solution for 90 s). If overall network excitability is increased, we predicted that depolarizing stimuli should produce larger Ca2+ signals.

With identical stimuli, networks of dorsal horn neurons in BDNF-treated DMOTC slices exhibited a larger increase in Fluo-4 fluorescence intensity compared to cells in the same region in control untreated DMOTC slices. This is clear from the images and sample traces of Fluo-4 fluorescence intensity signal for control (Fig. 10A and C) and BDNF-treated cells (Fig. 10B and D). Quantification of the peak amplitude revealed a significant increase in the Ca2+ response in the BDNF-treated group at all K+ concentrations tested (Fig. 10E, t test, P < 0.001). As well, the area under the Ca2+ intensity signal was significantly larger for the BDNF-treated DMOTC slices for all challenges (Fig. 10F, t test, P < 0.05).

Figure 10. Enhanced K+-induced Ca2+ rise in BDNF-treated DMOTC slices.

A–B, sample fluorescent Ca2+ intensity traces during a 90 s, 20 mm K+ challenge for a cell in a control DMOTC slice (A), and a BDNF-treated DMOTC slice (B). C and D, sample fluorescence images (512 × 512 pixels) of the dorsal region of a control slice (C) and a BDNF-treated DMOTC slice (D), loaded with Fluo-4 AM, during a 20 mm K+ solution challenge. White scale bar is 50 μm. E, comparison of Ca2+ fluorescence signal amplitude over a range of high K+ solutions tested. Amplitude of the signal was measured from baseline to peak of each trace recorded from cells in control and BDNF-treated DMOTC slices (n= 30 cells for control, n= 41 cells for BDNF). Scaling is in arbitrary units (a.u.) F, comparison of area under the Ca2+ fluorescence signal traces over a range of high K+ solutions in control and BDNF-treated DMOTC slices. At all concentrations tested, both area and amplitude of the Ca2+ signal were significantly larger in BDNF-treated cells (t test; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001). Error bars indicate s.e.m.G and H, sample baseline recordings from four cells in the same control DMOTC slice (G) and a BDNF-treated DMOTC slice (H). Dots with dashed lines indicate synchronous oscillations in Ca2+.

During the course of Ca2+ imaging experiments, synchronous oscillations in the Ca2+ signal were observed in BDNF-treated slices (Fig. 10H). These synchronous oscillations, which were not usually present in control slices (Fig. 10G), were observed across the entire dorsal region of the slice at a frequency of 0.05–0.1 Hz. All 7/7 BDNF-treated DMOTC slices tested, compared to only 2/9 control DMOTC slices, displayed this phenomenon. Because these effects were blocked by TTX (1 μm) and glutamatergic receptor blockers kyneurinic acid (1 mm) or NBQX (10 μm) (data not shown), they ate likely to represent oscillations in neuronal [Ca2+]i rather than glial [Ca2+]i.

Discussion

The main findings of this study are as follows. (1) BDNF produces a pattern of neuron type-specific changes that resembled those seen with CCI in vivo. This suggests that the actions of BDNF in DMOTCs are not a general neurotrophic effect but are instead more relevant to its putative role as a harbinger of neuropathic pain (Coull et al. 2005; Yajima et al. 2005). (2) BDNF increases excitatory synaptic drive to most neuron types except putative inhibitory ‘tonic’ cells, where synaptic drive decreases. (3) Effects of BDNF on putative excitatory ‘delay’ cells may be exclusively presynaptic whereas both pre- and post-components are involved in its action on putative inhibitory ‘tonic’ neurons. (4) BDNF does not increase the sensitivity of ‘delay’ cells to glutamate. (5) BDNF-induced changes in synaptic drive to discrete neuronal populations contribute to an overall increase in dorsal horn excitability.

To the best of our knowledge, all studies of injury-induced increases in spinal BDNF levels have relied on immunological or immunohistochemical techniques (Cho et al. 1997; Cho et al. 1998; Ha et al. 2001) and this has precluded measurements of exact neurotrophin concentration. The nature of our study dictated the use of a relatively high concentration of BDNF to assure that a robust effect would be observed. Extensive data analysis from large numbers of neurons was required to document the actions of BDNF. Had a lower concentration been used, considerable effort may have been wasted in attempting to statistically distinguish some potentially small effects. Also, because it was not feasible to routinely maintain sterile viable cultures for more than 40 days, the age of neurons used in the BDNF experiments only approximates that of the in vivo neurones used in the CCI study (Fig. 1). Neuronal age in the in vivo studies is dictated by the need to use animals > 20 days old to produce behavioural manifestations of neuropathic pain (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006). Although there are inevitable physiological differences between age-matched substantia gelatinosa neurons in vivo and in DMOTCs, these are surprisingly minor (Lu et al. 2006). We therefore contend that our comparison of CCI in vivo and BDNF's effects in DMOTCs is the best feasible methodology given the constraints imposed by the two experimental systems.

Cell type-specific effects of BDNF on excitatory synaptic transmission

Because input resistance, rheobase and firing latency were unchanged in most neuron types (Fig. 3 and Table 1), alterations in the intrinsic membrane excitability of individual neurons may play only a minor role in the increase in overall excitability of the dorsal horn produced by BDNF. An exception may be the increased excitability of ‘delay’ neurons (Fig. 3B) as these tended to display bursts of action potentials in response to spontaneously occurring EPSPs (Fig. 9D–G).

Thus, the actions of BDNF are dominated by its effects on synaptic activity (Figs 4–9). Spontaneous excitatory synaptic activity increased in all neuron types except ‘tonic’ cells where a decrease was observed (Fig. 4A, F, K and L). Interestingly, similar changes in excitatory synaptic activity were observed following sciatic nerve CCI (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006). Table 2 compares the changes seen in five defined types of substantia gelatinosa neurons in CCI with those seen with long-term BDNF exposure. The degree of similarity, which is especially clear for ‘tonic’, ‘delay’ and ‘transient’ neurons and for sEPSC frequency in all cell types, supports the role of BDNF in instigating changes in dorsal horn neurons which can lead to neuropathic pain.

It could of course be argued that any potentially traumatic manipulation of the cultures would produce a similar pattern of changes, so that the similarity between the actions of CCI and BDNF is of little significance. However, in other experiments we have maintained DMOTC in the presence of interleukin-1β. Although it has been suggested that this cytokine may be responsible for the development of various types of chronic inflammatory pain (Watkins et al. 1995; Ledeboer et al. 2005), it is probably not responsible for the allodynia associated with neuropathic pain (Ledeboer et al. 2006). Consistent with this, we found that the pattern of changes produced by IL-1β, was quite dissimilar to that produced by BDNF and CCI (Lu et al. 2005). This underlines the significance of the similarity between the actions of BDNF and CCI which produces neuropathic pain.

Effect of BDNF on ‘tonic’ neurons

Several lines of evidence are consistent with the possibility that ‘tonic’ neurons are inhibitory. Specifically, ‘tonic’ neurons often exhibit the morphology of dorsal horn islet cells (Grudt & Perl, 2002), and many islet cells express markers for GABAergic neurons (Todd & McKenzie, 1989; Heinke et al. 2004). Moreover, simultaneous paired whole-cell recordings of Lamina II neurons have revealed the generation of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials following stimulation of ‘tonic’ neurons (Lu & Perl, 2003).

Our finding that BDNF reduced excitatory synaptic transmission to ‘tonic’ neurons would predict decreased release of inhibitory neurotransmitters and a reduction in inhibitory tone within the dorsal horn network. Loss of inhibition has been implicated in the generation of pain-like behaviours in nerve injury models of neuropathic pain (Sivilotti & Woolf, 1994; Moore et al. 2002; Baba et al. 2003) and as shown in Table 2, a reduction in synaptic drive to ‘tonic’ neurons also occurs following CCI (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006).

The decrease in sEPSC and mEPSC frequency of ‘tonic’ neurons implicates a presynaptic site of action for BDNF. A loss of vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1), which has been observed following nerve injury (Oliveira et al. 2003; Alvarez et al. 2004), could account for the observed decrease in sEPSC and mEPSC frequency, but other mechanisms such as loss of presynaptic release sites may also be involved (Bailey et al. 2006). Reduced sEPSC frequency is unlikely to reflect a decrease in the frequency of presynaptic action potentials because a greater percentage of TTX-sensitive spontaneous events appeared in ‘tonic’ neurons after BDNF treatment (Fig. 9C).

Because the decrease in the time constant for mEPSC decay (τ2) has little effect on event amplitude (Fig. 7H–J), other pre- or postsynaptic mechanisms must be invoked to explain the BDNF-induced decrease in mEPSC amplitude. One possibility is dendritic shunting, as this would reduce the amplitude as well as increasing the rate of decay of mEPSCs. This could occur, for example, as a result of BDNF-induced increases in dendritic K+ conductance(s).

Thus, effects of BDNF on mEPSC in ‘tonic’ cells include a presynaptic component, which accounts for their decrease in frequency, a postsynaptic component, which accounts for their increased rate of decay, and a third component that may be either pre- or postsynaptic, which accounts for much of their reduction in amplitude.

Effect of BDNF on ‘delay’ neurons

Less than 1% of GAD-positive neurons in the substantia gelatinosa display a ‘delay’ firing pattern (Hantman et al. 2004; Heinke et al. 2004; Dougherty et al. 2005), and since simultaneous paired recordings show the production of an excitatory postsynaptic potential following stimulation of ‘delay’ neurons (Lu & Perl, 2005), these are likely to represent a population of excitatory neurons.

In contrast to ‘tonic’ neurons, long-term BDNF exposure produced a significant increase in excitatory synaptic drive to ‘delay’ neurons. As illustrated in Table 2, a similar effect was seen following CCI (Balasubramanyan et al. 2006). Lu & Perl (2005) have suggested Lamina II ‘delay’ neurons form excitatory connections with Lamina I neurons, which may include projection neurons that signal to higher pain centres. Therefore, enhanced activation of ‘delay’ neurons following BDNF treatment could lead to increased transmission of nociceptive information at the spinal level.

The increased frequency of sEPSCs in ‘delay’ neurons following BDNF treatment (Fig. 5G) implies a presynaptic site of action. However, the proportion of TTX-sensitive sEPSC events decreased (Fig. 6C), indicating a smaller proportion of spontaneous synaptic events were action potential dependent. This argues against an increase in presynaptic action potential activity as a mechanism of BDNF action. Noxious stimulation induces phosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit of AMPA receptors and subsequently enhances recruitment and surface expression of functional AMPA receptors (Nagy et al. 2004; Galan et al. 2004). Interestingly, BDNF has also been shown to enhance phosphorylation of the GluR1 subunit (Wu et al. 2004). GluR1 is strongly associated with nociceptive primary afferents and its distribution in the dorsal horn is restricted to Lamina II (Lee et al. 2002; Nagy et al. 2004). Possible recruitment of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors presynaptically could increase intracellular Ca2+ levels in the terminal and thereby enhance action potential-independent glutamate release. This could explain action of BDNF on mEPSC amplitude and frequency. If expression of GluR1 is specific to primary afferent terminals that contact ‘delay’ neurons, this could represent a possible mechanism by which BDNF can differentially affect one neuron type in the dorsal horn and not another.

Increased insertion of postsynaptic AMPA receptors is unlikely to occur as the mean amplitudes of the three populations of mEPSCs in delay neurons were unchanged (Fig. 8E–G) and a new population of events appeared in BDNF-treated neurons. These large events may reflect coincident release of two or more vesicles from terminals contacting ‘delay’ cells. Mechanistically, this could reflect increased levels of ambient Ca2+ in the presynaptic terminal as described above, or perhaps BDNF-induced sprouting of presynaptic terminals such that coincidental release of vesicles occurs more frequently.

These observations are important as they imply that BDNF treatment does not change the postsynaptic sensitivity of ‘delay’ cells to glutamate (Fig. 8G). This further suggests that its actions do not invoke an LTP-type phenomenon involving the insertion of new postsynaptic AMPA receptors (Hayashi et al. 2000). We therefore attribute all actions of BDNF on synaptic activity in ‘delay’ cells to presynaptic mechanisms.

Effect of BDNF on ‘irregular’, ‘phasic’ and ‘transient’ neurons

There is currently no consensus as to the transmitter phenotype of neurons that exhibit an ‘irregular’, ‘phasic’ or ‘transient’ firing pattern. Rather, evidence has been found to support these neurons as both excitatory or inhibitory (Hantman et al. 2004; Heinke et al. 2004; Dougherty et al. 2005). Regardless, the magnitude and frequency of spontaneous excitatory neurotransmission to all three neuron types increased significantly following BDNF treatment (Fig. 5C–E and H–J). Because of the ambiguity of these neuronal populations, it is unclear if an increase in the excitatory drive to any of them would enhance excitation in the dorsal horn. Nevertheless, it would appear that the action potential-dependent population of synaptic events mainly contributed to the increase in synaptic events for ‘irregular’ neurons. This implicates BDNF in increasing the activity of presynaptic excitatory neurons, either primary afferents or excitatory spinal interneurons such as ‘delay’ neurons.

Several underlying mechanisms may underlie the differential actions of BDNF on the various cell types in dorsal horn. First, as already mentioned, GluR1 receptors which are phosphorylated following BDNF exposure (Wu et al. 2004) are strongly associated with nociceptive primary afferents (Lee et al. 2002). This implies that BDNF may not affect terminals that do not express these receptors. Second, BDNF exerts its actions both by TrkB and via the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Whereas TrkB activation generally produces positive actions on neuronal growth and sprouting, activation of p75 can sometimes produce effects that are deleterious and can even include apoptosis (Huang & Reichardt, 2003). Thus, in order to determine how the differential effects of BDNF on various neurons terminals and cell bodies in the dorsal horn are generated, it will be necessary to determine which AMPA receptor subtypes and which BDNF receptors are expressed on the cell bodies and afferent terminals of various types of electrophysiologically defined dorsal horn neuron. Such information is not yet available.

Long-term BDNF exposure increases overall dorsal horn excitability

The Ca2+ responses to high K+ stimulation were significantly larger in BDNF-treated DMOTC slices than in age-matched controls (Fig. 10). Therefore, the cellular changes produced by BDNF contributed to an overall increase in the excitability of the dorsal horn.

Even though the [Ca2+]i was not determined, the relative increase in Fluo-4 fluorescence signal intensity still provided a good measure of a slice's excitability since Fluo-4 fluorescence intensity correlates well with Ca2+ concentration at physiological ranges (Gee et al. 2000). Also, it is unlikely that the dye saturated since there was a progressive increase in the Ca2+ signal amplitude at higher K+ concentrations.

Although other studies have examined the acute effects of BDNF on dorsal horn neurons (Kerr et al. 1999; Garraway et al. 2003; Slack et al. 2004), we are the first to show that long-term, 5–6 days exposure to BDNF, which resembles the time course of nerve injury-induced BDNF elevation (Cho et al. 1997; Zhou et al. 1999; Dougherty et al. 2000; Fukuoka et al. 2001), can induce persistent, and possibly permanent, changes to the dorsal horn network. BDNF is also well known to attenuate GABAergic transmission in dorsal horn (Coull et al. 2005) and such effects could contribute to increased excitability seen in our experiments. The long-term effects of BDNF on spinal GABAergic function in ‘tonic’, ‘delay’, ‘phasic’, ‘transient’ and ‘irregular’ cells are currently being investigated.

The phenomenon of rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations has been reported in the spinal cord following various pharmacological manipulations (Ruscheweyh & Sandkuhler, 2005) or during development (Fabbro et al. 2007). Our observation that the probability of synchronous Ca2+ oscillations increased notably in BDNF-treated DMOTC slices shows that they may play a role in the pathology of chronic pain in adults. Similar oscillations have also been described in hippocampal slices under epileptiform conditions (Kovacs et al. 2005) suggesting they may be indicative of hyperexcitable networks.

Conclusions

BDNF induced significant changes in excitatory neurotransmission that reflected both pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms but there was no obvious increase in sensitivity of postsynaptic neurons to glutamate. The pattern of changes was specific to different neuronal populations and was not uniform across the entire dorsal horn. This distinct pattern of changes contributes to an increase in overall excitability in BDNF-treated DMOTC slices. Moreover, the similarity between this pattern of changes and that seen in CCI are consistent with a role for BDNF in the induction of neuropathic pain.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Araya Ruangkittisakul for skilled assistance with calcium imaging experiments, Dr Gerda deVries for help with curve fitting and Dr Kwai Alier for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. Funding support was provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR, MOP 13456 and MT10520), the Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR). V.B.L. received studentship stipends from the CIHR and AHFMR. W.F.C. and K.B. are AHFMR Medical Scientists. Funding for equipment in K.B.'s laboratory provided by AHFMR, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the Alberta Science and Research Authority (ASRA).

References

- Alvarez FJ, Villalba RM, Zerda R, Schneider SP. Vesicular glutamate transporters in the spinal cord, with special reference to sensory primary afferent synapses. J Comp Neurol. 2004;472:257–280. doi: 10.1002/cne.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfel SC, Wright DE, Wiideman AM, Dormia C, Snider WD, Kessler JA. Nerve growth factor regulates the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA in the peripheral nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;7:134–142. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba H, Doubell TP, Woolf CJ. Peripheral inflammation facilitates Aβ fiber-mediated synaptic input to the substantia gelatinosa of the adult rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:859–867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00859.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba H, Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Ataka T, Wakai A, Okamoto M, Woolf CJ. Removal of GABAergic inhibition facilitates polysynaptic A fiber-mediated excitatory transmission to the superficial spinal dorsal horn. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:818–830. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AL, Ribeiro-da-Silva A. Transient loss of terminals from non-peptidergic nociceptive fibers in the substantia gelatinosa of spinal cord following chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve. Neuroscience. 2006;138:675–690. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanyan S, Stemkowski PL, Stebbing MJ, Smith PA. Sciatic chronic constriction injury produces cell-type-specific changes in the electrophysiological properties of rat substantia gelatinosa neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:579–590. doi: 10.1152/jn.00087.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SR, Pan HL. Hypersensitivity of spinothalamic tract neurons associated with diabetic neuropathic pain in rats. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2726–2733. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Kim JK, Park HC, Kim JK, Kim DS, Ha SO, Hong HS. Changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor immunoreactivity in rat dorsal root ganglia, spinal cord, and gracile nuclei following cut or crush injuries. Exp Neurol. 1998;154:224–230. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Kim JK, Zhou XF, Rush RA. Increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor immunoreactivity in rat dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord following peripheral inflammation. Brain Res. 1997;764:269–272. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00597-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomo F, Erulkar SD. Miniature synaptic potentials at frog spinal neurones in the presence of tertodotoxin. J Physiol. 1968;199:205–221. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JA, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Gravel C, Salter MW, De Koninck Y. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature. 2005;438:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal A, Tata M, Allegre G, Gekiere F, Bons N, Albe-Fessard D. Spontaneous activity of rat dorsal horn cells in spinal segments of sciatic projection following transection of sciatic nerve or of corresponding dorsal roots. Neuroscience. 1999;94:217–228. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty KD, Dreyfus CF, Black IB. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and microglia/macrophages after spinal cord injury. Neurobiol Dis. 2000;7:574–585. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty KJ, Sawchuk MA, Hochman S. Properties of mouse spinal lamina I GABAergic interneurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3221–3227. doi: 10.1152/jn.00184.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbro A, Pastore B, Nistri A, Ballerini L. Activity-independent intracellular Ca2+ oscillations are spontaneously generated by ventral spinal neurons during development in vitro. Cell Calcium. 2007;41:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka T, Kondo E, Dai Y, Hashimoto N, Noguchi K. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor increases in the uninjured dorsal root ganglion neurons in selective spinal nerve ligation model. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4891–4900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04891.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan A, Laird JM, Cervero F. In vivo recruitment by painful stimuli of AMPA receptor subunits to the plasma membrane of spinal cord neurons. Pain. 2004;112:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway SM, Petruska JC, Mendell LM. BDNF sensitizes the response of lamina II neurons to high threshold primary afferent inputs. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2467–2476. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee KR, Brown KA, Chen WN, Bishop-Stewart J, Gray D, Johnson I. Chemical and physiological characterization of fluo-4 Ca2+-indicator dyes. Cell Calcium. 2000;27:97–106. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grudt TJ, Perl ER. Correlations between neuronal morphology and electrophysiological features in the rodent superficial dorsal horn. J Physiol. 2002;540:189–207. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha SO, Kim JK, Hong HS, Kim DS, Cho HJ. Expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rat dorsal root ganglia, spinal cord and gracile nuclei in experimental models of neuropathic pain. Neuroscience. 2001;107:301–309. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, Waxman SG. Activated microglia contribute to the maintenance of chronic pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4308–4317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0003-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantman AW, van den Pol AN, Perl ER. Morphological and physiological features of a set of spinal substantia gelatinosa neurons defined by green fluorescent protein expression. J Neurosci. 2004;24:836–842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4221-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi Y, Shi SH, Esteban JA, Piccini A, Poncer JC, Malinow R. Driving AMPA receptors into synapses by LTP and CaMKII: requirement for GluR1 and PDZ domain interaction. Science. 2000;287:2262–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5461.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinke B, Ruscheweyh R, Forsthuber L, Wunderbaldinger G, Sandkuhler J. Physiological, neurochemical and morphological properties of a subgroup of GABAergic spinal lamina II neurones identified by expression of green fluorescent protein in mice. J Physiol. 2004;560:249–266. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:609–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr BJ, Bradbury EJ, Bennett DL, Trivedi PM, Dassan P, French J, Shelton DB, McMahon SB, Thompson SW. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates nociceptive sensory inputs and NMDA-evoked responses in the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5138–5148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05138.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Yoon YW, Chung JM. Comparison of three rodent neuropathic pain models. Exp Brain Res. 1997;113:200–206. doi: 10.1007/BF02450318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno T, Moore KA, Baba H, Woolf CJ. Peripheral nerve injury alters excitatory synaptic transmission in lamina II of the rat dorsal horn. J Physiol. 2003;548:131–138. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs R, Kardos J, Heinemann U, Kann O. Mitochondrial calcium ion and membrane potential transients follow the pattern of epileptiform discharges in hippocampal slice cultures. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4260–4269. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4000-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird JM, Bennett GJ. An electrophysiological study of dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord of rats with an experimental peripheral neuropathy. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:2072–2085. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeboer A, Mahoney JH, Milligan ED, Martin D, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Spinal cord glia and interleukin-1 do not appear to mediate persistent allodynia induced by intramuscular acidic saline in rats. J Pain. 2006;7:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledeboer A, Sloane EM, Milligan ED, Frank MG, Mahony JH, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Minocycline attenuates mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in rat models of pain facilitation. Pain. 2005;115:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CJ, Bardoni R, Tong CK, Engelman HS, Joseph DJ, Magherini PC, MacDermott AB. Functional expression of AMPA receptors on central terminals of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons and presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release. Neuron. 2002;35:135–146. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00729-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu VB, Chee MJS, Gustafson SL, Colmers WF, Smith PA. 2005 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2005. Concentration-dependent effects of long-term interleukin-1 treatment on spinal dorsal horn neurons in organotypic slice cultures. Program No. 292.3. [Google Scholar]

- Lu VB, Colmers WF, Dryden WF, Smith PA. 2004 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2004. Brain – derived neurotrophic factor alters the synaptic activity of dorsal horn neurons in long-term organotypic spinal cord slice cultures. Program No. 289,15. [Google Scholar]

- Lu VB, Moran TD, Balasubramanyan S, Alier KA, Dryden WF, Colmers WF, Smith PA. Substantia gelatinosa neurons in defined-medium organotypic slice culture are similar to those in acute slices from young adult rats. Pain. 2006;121:261–275. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Perl ER. A specific inhibitory pathway between substantia gelatinosa neurons receiving direct C-fiber input. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8752–8758. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08752.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Perl ER. Modular organization of excitatory circuits between neurons of the spinal superficial dorsal horn (laminae I and II) J Neurosci. 2005;25:3900–3907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0102-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matayoshi S, Jiang N, Katafuchi T, Koga K, Furue H, Yasaka T, Nakatsuka T, Zhou XF, Kawasaki Y, Tanaka N, Yoshimura M. Actions of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on spinal nociceptive transmission during inflammation in the rat. J Physiol. 2005;569:685–695. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael GJ, Averill S, Shortland PJ, Yan Q, Priestley JV. Axotomy results in major changes in BDNF expression by dorsal root ganglion cells: BDNF expression in large trkB and trkC cells, in pericellular baskets, and in projections to deep dorsal horn and dorsal column nuclei. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:3539–3551. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miletic G, Miletic V. Increases in the concentration of brain derived neurotrophic factor in the lumbar spinal dorsal horn are associated with pain behavior following chronic constriction injury in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;319:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA, Kohno T, Karchewski LA, Scholz J, Baba H, Woolf CJ. Partial peripheral nerve injury promotes a selective loss of GABAergic inhibition in the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6724–6731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06724.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran TD, Colmers WF, Smith PA. Opioid-like actions of neuropeptide Y in rat substantia gelatinosa: Y1 suppression of inhibition and Y2 suppression of excitation. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:3266–3275. doi: 10.1152/jn.00096.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy GG, Al Ayyan M, Andrew D, Fukaya M, Watanabe M, Todd AJ. Widespread expression of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit at glutamatergic synapses in the rat spinal cord and phosphorylation of GluR1 in response to noxious stimulation revealed with an antigen-unmasking method. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5766–5777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1237-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AL, Hydling F, Olsson E, Shi T, Edwards RH, Fujiyama F, Kaneko T, Hokfelt T, Cullheim S, Meister B. Cellular localization of three vesicular glutamate transporter mRNAs and proteins in rat spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. Synapse. 2003;50:117–129. doi: 10.1002/syn.10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangkittisakul A, Schwarzacher SW, Secchia L, Poon BY, Ma Y, Funk GD, Ballanyi K. High sensitivity to neuromodulator-activated signaling pathways at physiological [K+] of confocally imaged respiratory center neurons in on-line-calibrated newborn rat brainstem slices. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11870–11880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3357-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscheweyh R, Sandkuhler J. Long-range oscillatory Ca2+ waves in rat spinal dorsal horn. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1967–1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivilotti L, Woolf CJ. The contribution of GABAA and glycine receptors to central sensitization: disinhibition and touch-evoked allodynia in the spinal cord. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:169–179. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.1.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack SE, Pezet S, McMahon SB, Thompson SW, Malcangio M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces NMDA receptor subunit one phosphorylation via ERK and PKC in the rat spinal cord. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1769–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PA, Lu VB, Balasubramanyan S. 2005 Abstract Viewer/Itinerary Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; 2005. Chronic constriction injury and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) generate similar ‘pain footprints’ in dorsal horn neurons. Program No. 748,2. [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ, McKenzie J. GABA-immunoreactive neurons in the dorsal horn of the rat spinal cord. Neuroscience. 1989;31:799–806. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Inoue K, Salter MW. Neuropathic pain and spinal microglia: a big problem from molecules in ‘small’ glia. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins LR, Maier SF, Goehler LE. Immune activation: the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in inflammation, illness responses and pathological pain states. Pain. 1995;63:289–302. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ. Evidence for a central component of post-injury pain hypersensitivity. Nature. 1983;306:686–688. doi: 10.1038/306686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Len GW, McAuliffe G, Ma C, Tai JP, Xu F, Black IB. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor acutely enhances tyrosine phosphorylation of the AMPA receptor subunit GluR1 via NMDA receptor-dependent mechanisms. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;130:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]