Abstract

Data are scant regarding the capacity of cerebrovascular regulation during asphyxia for prevention of brain oxygen deficit in intrauterine growth-restricted (IUGR) newborns. We tested the hypothesis that IUGR improves the ability of neonates to withstand critical periods of severe asphyxia by optimizing brain oxygen supply. Studies were conducted to examine the effects of IUGR on cerebral blood flow (CBF) regulation and oxygen consumption (cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen, CMRO2) at different stages of asphyxia (hypercapnic hypoxaemia) in comparison to pure hypoxia (normocapnic hypoxaemia). We used 1-day-old anaesthetized and ventilated piglets. Animals were divided into normal weight (NW) piglets (n= 47; aged 11–26 h, body weight 1481 ± 121 g) and IUGR piglets (n= 48; aged 13–28 h, body weight 806 ± 42 g) according to their birth weight. Different stages of hypoxaemia were induced for 1 h by appropriate lowering of the inspired fraction of oxygen (moderate hypoxia:  = 31–34 mmHg; severe hypoxia:

= 31–34 mmHg; severe hypoxia:  = 20–22 mmHg). Fourteen NW and 16 IUGR piglets received additionally 9% CO2 in the breathing gas, so that a

= 20–22 mmHg). Fourteen NW and 16 IUGR piglets received additionally 9% CO2 in the breathing gas, so that a  of 74–80 mmHg resulted (hypoxia/hypercapnia groups). Eight NW and nine IUGR animals served as untreated controls. Furthermore, affinity of haemoglobin for oxygen was measured under hypoxic and asphyxic conditions. During asphyxia cerebral oxygen extraction was markedly increased in IUGR animals (P < 0.05). This resulted in a significantly diminished CMRO2-related increase of CBF at gradually reduced arterial oxygen content (P < 0.05). Therefore, an enhanced effectivity in oxygen availability appeared in newborn IUGR piglets under graded asphyxia by improved cerebral oxygen utilization (P < 0.05). This was not supported by related O2 affinity of haemoglobin. Thus, IUGR newborns are more capable to ensure brain O2 demand during asphyxia (hypercapnic hypoxia) than NW neonates.

of 74–80 mmHg resulted (hypoxia/hypercapnia groups). Eight NW and nine IUGR animals served as untreated controls. Furthermore, affinity of haemoglobin for oxygen was measured under hypoxic and asphyxic conditions. During asphyxia cerebral oxygen extraction was markedly increased in IUGR animals (P < 0.05). This resulted in a significantly diminished CMRO2-related increase of CBF at gradually reduced arterial oxygen content (P < 0.05). Therefore, an enhanced effectivity in oxygen availability appeared in newborn IUGR piglets under graded asphyxia by improved cerebral oxygen utilization (P < 0.05). This was not supported by related O2 affinity of haemoglobin. Thus, IUGR newborns are more capable to ensure brain O2 demand during asphyxia (hypercapnic hypoxia) than NW neonates.

Asymmetric IUGR is a crucial factor for perinatal asphyxia and is associated with an increased incidence of perinatal morbidity and mortality including ‘unexplained’ stillbirth (Ashworth, 1998; Kady & Gardosi, 2004). Recent epidemiological studies report on a considerable proportion of permanent neurological sequels following peri-/intranatally occurring asphyxia leading to severe hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy as the single most known cause for cerebral palsy (Cowan et al. 2003; Shevell et al. 2003). Increased risk for peri-/intranatal asphyxia in IURG results mainly from placental insufficiency as the main cause for progressive growth restriction in late fetal life (Levene et al. 1985).

The slow-down of fetal growth late in gestation following intrauterine malnutrition, although resulting in IUGR, can be regarded as a compensatory process, which enables the fetus to survive and thus improves the reproduction rate (Warshaw, 1985; Aplin, 2000). Growth reduction is primarily achieved by altering the endo-crine milieu, possibly by reducing the endocrine and paracrine insulin-like growth factor I activity (Gluckman & Harding, 1997) in response to impaired transplacental nutrient transfer (Liechty et al. 1999). Reduced substrate consumption enables – at least at times – the prevention of a life-threatening imbalance between nutritional supply and demand. Therefore, the period of suitable compensation, characterized by reduced growth due to restricted nutrient availability, but widely compensated placental respiratory function (Pardi et al. 1993), reflects a functional state in which the fetus is able to alter organ maturation including brain functional development (Cook et al. 1988; Henderson Smart, 1995; Bauer et al. 2002). However, additional disturbances of placental perfusion, such as effects of uterus contraction before or during delivery are frequently responsible for acute disruption of fetal gas exchange. Under such circumstances, a sufficient circulatory redistribution towards the cerebral circulation is thought to maintain brain O2 delivery and, hence, prevent disturbances of brain energy supply and their harmful consequences (Jensen et al. 1999). Recent observations suggest that IUGR may have a specific protective influence on brain energy metabolism under conditions with the danger of critical O2 deficiency. We have recently shown that newborn IUGR piglets exhibit an improved ability to withstand critical periods of hypoxia– ischaemia during haemorrhagic hypotension by improved cerebrovascular autoregulation (Bauer et al. 2004).

Until now, there has been insufficient knowledge of the effects of metabolic regulation of cerebral blood flow in IUGR suffering from acute asphyxia. Therefore, we estimated CBF and CMRO2 during gradual hypercapnic hypoxia mimicking states of moderate and severe asphyxia in term-born IUGR newborns. We compared these conditions with those of normocapnic hypoxia in order to differentiate the independent effects of hypoxaemia and hypercapnia on cerebrovascular response and brain O2 metabolism. We used a morphometrically well-characterized state of IUGR in newborn piglets (Bauer et al. 1998b) and included animals with optimal vital conditions early after birth. We verified the hypothesis that IUGR improves the ability of neonates to withstand critical periods of severe asphyxia by optimizing brain oxygen supply.

Methods

All surgical and experimental procedures were approved by the committee of the Thuringian State Government on Animal Research. Animals were obtained from a breeding farm. Delivery was observed and the viability of neonatal piglets assessed immediately after birth so that only animals with a viability score ≥ 7 were included in the study. Immediately before the onset of the experiments, animals were carried to the laboratory in a transport incubator. Animals were divided into normal weight (NW) piglets (n= 47; aged 11–26 h, body weight 1481 ± 121 g) and IUGR piglets (n= 48; aged 13–28 h, body weight 806 ± 42 g) according to their birth weight. The birth weight distribution of the breed of piglets used here (German Landrace) has been previously described (Bauer et al. 1998b).

Anaesthesia and surgical preparation

For in vivo studies 40 NW and 39 IUGR piglets were initially anaesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane in 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen by mask. The anaesthesia was maintained throughout the surgical procedure with 1.25% isoflurane. Cutaneous incisions were made after subcutaneous instillation of a local anaesthetic (Xylocitin 2%, Jenapharm, Jena, Germany). A central venous catheter was introduced through the left external jugular vein and was used for the administration of drugs and for volume substitution (heparinized isotonic saline solution (1 i.u. heparin ml−1); 5 ml h−1). An endotracheal tube was inserted through a tracheotomy. After immobilization with pancuronium bromide (0.2 mg (kg body weight)−1 h−1, i.v.), the piglets were artificially ventilated (Servo Ventilator 900C, Siemens-Elema, Sweden). The artificial ventilation was adjusted to maintain normoxic and normocapnic blood gas values. Polyurethane catheters (inner diameter 0.5 mm) were advanced through both umbilical arteries into the abdominal aorta in order to record the arterial blood pressure and to withdraw reference samples for the coloured microsphere technique. A further polyurethane catheter (inner diameter 0.3 mm) was inserted into the superior sagittal sinus through a midline burr hole (3 mm in diameter and located 4 mm caudal to the bregma) and advanced to the confluence of the sinuses in order to obtain brain venous blood samples. The left ventricle was cannulated retrogradely via the right common carotid artery with a polyurethane catheter (inner diameter 0.5 mm). The arterial, left ventricular, and the central venous catheters were connected with pressure transducers (P23Db, Statham Instruments Inc., Hato Rey, Puerto Rico). Correct positioning of the catheter tips was checked by continuous pressure trace recordings and by autopsy at the end of the experiment. Body temperature was monitored by a rectal temperature probe, and was maintained throughout the experiment at 38 ± 0.3°C using a warmed pad and a feedback-controlled heating lamp. Physiological parameters were recorded on a multichannel polygraph (MT95K2, Astro-Med, USA). The arterial blood pressure was monitored continuously, and arterial blood samples were withdrawn and analysed at regular intervals to monitor blood gases and whole blood acid–base parameters.

Experimental protocol

After the surgical preparation was completed, blood exchange of 30 ml was performed (intravenous infusion of heparinized blood obtained from a donor piglet and withdrawal of the same amount from an arterial line, simultaneously) to replace blood volume throughout the experiment. Then, the isoflurane concentration was adjusted to 0.25% in 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen, and the piglets were allowed to rest for ∼60 min.

After control values had been obtained, 31 randomly chosen NW piglets (group 3, n= 8; group 5, n= 7; group 7, n= 7; group 9, n= 9) and 31 IUGR piglets (group 4, n= 8; group 6, n= 7; group 8, n= 7; group 10, n= 9) underwent a 1 h hypoxic insult. Two different levels of hypoxic hypoxia were performed by lowering the inspired fraction of oxygen  from 0.35 to 0.09 in exchange for nitrogen to ensure a moderate degree of arterial hypoxaemia (groups 3, 4, 7, 8) or an

from 0.35 to 0.09 in exchange for nitrogen to ensure a moderate degree of arterial hypoxaemia (groups 3, 4, 7, 8) or an  lowering from 0.35 to 0.06 in exchange for nitrogen to ensure a severe degree of arterial hypoxaemia (groups 5, 6, 9, 10). Furthermore, CO2 was added in groups 7–10 resulting in a hypercapnic hypoxaemia with an arterial

lowering from 0.35 to 0.06 in exchange for nitrogen to ensure a severe degree of arterial hypoxaemia (groups 5, 6, 9, 10). Furthermore, CO2 was added in groups 7–10 resulting in a hypercapnic hypoxaemia with an arterial

of 76 ± 5 mmHg. Thereafter, ventilatory gas mixture was re-established, and the recovery was monitored for 180 min. Immediately after the hypoxic insult a metabolic acidosis was treated by appropriate bicarbonate administration.

of 76 ± 5 mmHg. Thereafter, ventilatory gas mixture was re-established, and the recovery was monitored for 180 min. Immediately after the hypoxic insult a metabolic acidosis was treated by appropriate bicarbonate administration.

The remaining NW piglets (group 1, n= 8) and IUGR piglets (group 2, n= 9) were submitted to all experimental procedures except the alterations of inspired gas mixture and served as untreated control animals.

After the experiments were completed, the deeply anaesthetized animals were killed by intravenous administration of saturated KCl solution.

Measurements

Blood flow and other physiological measurements

The cerebral blood flow (CBF) was measured by means of the reference sample colour-labelled microsphere (Dye-Trak, Triton Technology, San Diego, CA, USA) technique, which represents a valid alternative to the radionuclide-labelled microsphere method for organ blood flow measurement in newborn piglets without the disadvantages arising from radioactive labelling (Walter et al. 1997). Application of this technique in piglets and methodological considerations have been presented and discussed in detail (Walter et al. 1997). Briefly, in random colour sequence, a known amount of coloured polystyrene microspheres was injected into the left ventricle. A blood sample was withdrawn from the abdominal aorta as the reference sample. At the end of each experiment, the piglet brains were obtained. In order to retrieve the microspheres, each tissue sample was digested and then filtered under vacuum suction through an 8-μm pore polyester-membrane filter. Coloured microspheres were quantified by their dye content. The dye was recovered from the microspheres by adding dimethylformamide. The photometric absorption of each dye solution was measured by a diode-array UV/visible spectrophotometer (Model 7500, Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA, USA). Calculations were performed using MISS software (Triton Technology). The number of microspheres was calculated using the specific absorbance value of the different dyes. All reference and tissue samples contained > 400 microspheres.

Arterial blood pressure (ABP), arterial and brain venous pH,  ,

,  , oxygen saturation and Hb values were measured immediately before the microsphere injection. Blood pH,

, oxygen saturation and Hb values were measured immediately before the microsphere injection. Blood pH,  , and

, and  were measured with a blood gas analyser (model ABL50, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark) and blood Hb and oxygen saturation were measured using a haemoximeter (model OSM2, Radiometer), and corrected to the body temperature of the animal at the time of sampling. Glucose and lactate contents were determined with an electrolyte and metabolite analyser (model EML105, Radiometer).

were measured with a blood gas analyser (model ABL50, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark) and blood Hb and oxygen saturation were measured using a haemoximeter (model OSM2, Radiometer), and corrected to the body temperature of the animal at the time of sampling. Glucose and lactate contents were determined with an electrolyte and metabolite analyser (model EML105, Radiometer).

The absolute flows to the tissues measured by the coloured microspheres were calculated by the formula: flowtissue= number of microspherestissue× (flowreference/number of microspheresreference). Flows were expressed in millilitres per minute per 100 g tissue by normalizing for tissue weight. Blood O2 content  was calculated using the equation:

was calculated using the equation:

|

to obtain the sum of oxygen which is physically dissolved and chemically bound to haemoglobin (cHb, Hb concentration;  , O2 saturation; 1.39 [ml g−1], theoretical oxygen capacity of Hb; α

, O2 saturation; 1.39 [ml g−1], theoretical oxygen capacity of Hb; α , solubility of O2 in blood =cHb× 0.000054 [Hb-dependent O2 solubility]+ 0.0029 [solubility of O2 in plasma]). Because the sagittal sinus drains the cerebral cortex, the cerebral white matter, and some deep grey structures (basal ganglia, thalamus, and hippocampus), the blood flow measured to the forebrain included these structures. The CMRO2 was obtained by multiplying the blood flow to the forebrain by the cerebral arteriovenous O2 content difference. Cerebral oxygen extraction was calculated as the ratio between cerebral arteriovenous O2 content difference and arterial O2 content. Cerebrovascular resistance (CVR) was calculated by division of mean arterial blood pressure by CBF.

, solubility of O2 in blood =cHb× 0.000054 [Hb-dependent O2 solubility]+ 0.0029 [solubility of O2 in plasma]). Because the sagittal sinus drains the cerebral cortex, the cerebral white matter, and some deep grey structures (basal ganglia, thalamus, and hippocampus), the blood flow measured to the forebrain included these structures. The CMRO2 was obtained by multiplying the blood flow to the forebrain by the cerebral arteriovenous O2 content difference. Cerebral oxygen extraction was calculated as the ratio between cerebral arteriovenous O2 content difference and arterial O2 content. Cerebrovascular resistance (CVR) was calculated by division of mean arterial blood pressure by CBF.

Determination of haemoglobin affinity for oxygen

For determination of haemoglobin affinity for oxygen, individual oxygen dissociation curves were estimated. Therefore, from eight NW and eight IUGR piglets 2 ml arterial blood was obtained (i) under normoxic/normocapnic conditions, and (ii) under normoxic/hypercapnic conditions. Blood was heparinized and immediately filled in a temperature-controlled (37°C) tonometer. By means of stepwise desaturation by aerating with either (i) a 90% nitrogen–5.6% carbon dioxide gas mixture, or (ii) a 94.4% nitrogen–10.0% carbon dioxide gas mixture, individual oxygen dissociation curves were performed under standardized acid–base balance conditions. The half-saturation oxygen pressure (P50) values were calculated under (i) normocapnic or (ii) hypercapnic conditions from linear interpolations using the Hill plot.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as means ±s.d. Comparisons between groups were made with one-way ANOVA. Comparisons of measurements between baseline and different stages of normocapnic or hypercapnic hypoxaemia within the groups were made with one-way ANOVA, with repeated measures. Post hoc comparisons were made with Tukey's test for all pairwise multiple comparisons. In order to verify a relationship between determinants of cerebral blood pressure regulation during normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia a simple linear regression was performed if the data passed the test of the assumption that the source population was normally distributed around the regression line. Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to estimate differences in regressions coefficients between NW and IUGR animals during normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia as well as within both animal groups under different experimental conditions. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 summarizes some morphometric parameters of the experimental groups. Naturally occurring growth restriction in swine is asymmetrical with an increase in the mean ratio of brain weight to liver weight from 0.92–1.07 to 1.59–2.02 (P < 0.01). The reduction in brain weight was quite small (90% of NW groups). In contrast, the decrease in liver weight (47–55% of NW groups) was similar to that in body weight (54–55% of NW groups). All differences in organ weight were significant (P < 0.01). Comparisons within the NW groups as well as the IUGR groups did not show any relevant differences.

Table 1.

Organ weights of newborn piglets following normal growth (NW: groups 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9) or restricted intrauterine growth (IUGR: groups 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10)

| Group | n | Body weight (g) | Brain weight(g) | Liver weight (g) | Brain/liver ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 1496 ± 114 | 33.1 ± 0.6 | 36.6 ± 5.8 | 0.92 ± 0.13 |

| 2 | 9 | 802 ± 44* | 29.5 ± 0.2* | 17.6 ± 2.6* | 1.71 ± 0.26* |

| 3 | 8 | 1496 ± 167 | 33.2 ± 0.8 | 31.8 ± 3.7 | 1.05 ± 0.11 |

| 4 | 8 | 838 ± 19* | 29.7 ± 0.1* | 15.7 ± 3.9* | 1.99 ± 0.47* |

| 5 | 7 | 1483 ± 127 | 33 ± 0.7 | 31.3 ± 3.8 | 1.07 ± 0.12 |

| 6 | 7 | 809 ± 40* | 29.5 ± 0.2* | 16 ± 1.2* | 1.85 ± 0.14* |

| 7 | 7 | 1496 ± 100 | 33.1 ± 0.5 | 31.1 ± 2.6 | 1.07 ± 0.08 |

| 8 | 7 | 783 ± 40* | 29.4 ± 0.2* | 14.9 ± 2.4* | 2.02 ± 0.31* |

| 9 | 9 | 1443 ± 110 | 32.8 ± 2.2 | 33.6 ± 7.6 | 1.01 ± 0.19 |

| 10 | 9 | 797 ± 47* | 28.7 ± 1.8* | 18.9 ± 3.8* | 1.59 ± 0.39* |

Normal weight (NW) groups: 1 (untreated), 3 (moderate normocapnic hypoxia), 5 (severe normocapnic hypoxia), 7 (moderate hypercapnic hypoxia), 9 (severe hypercapnic hypoxia). IUGR groups: 2 (untreated), 4 (moderate normocapnic hypoxia), 6 (severe normocapnic hypoxia), 8 (moderate hypercapnic hypoxia), 10 (severe hypercapnic hypoxia). Values are means ±s.d.

P < 0.01, comparison between normal weight and IUGR newborn piglets.

During baseline conditions ABP, acid–base balance, and blood gas values were similar in NW and IUGR piglets and within the physiological range (Table 2), and consistent with other data obtained from anaesthetized and artificially ventilated newborn piglets (Eisenhauer et al. 1994). However, arterial glucose content was markedly reduced by 36% in IUGR piglets (P < 0.01) whereas arterial lactate content was slightly elevated by 16% (P < 0.05). Cerebrovascular and brain metabolic data obtained were also similar in NW and IUGR piglets (Table 3).

Table 2.

Effect of gradual normocapnic (NCH) and hypercapnic hypoxia (HCH) on arterial blood gases, acid–base balance, and metabolic parameters in NW and IUGR piglets

| Baseline | Hypoxia 10th min | Hypoxia 50th min | Recovery 180th min | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial blood pressure (mmHg) | ||||||

| Control | NW | 67 ± 4 | 71 ± 7 | 72 ± 4 | 68 ± 10 | |

| IUGR | 60 ± 7 | 62 ± 7 | 64 ± 13 | 56 ± 6 | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 60 ± 6 | 65 ± 9 | 68 ± 11# | 56 ± 8 |

| IUGR | 58 ± 10 | 61 ± 9 | 59 ± 11 | 60 ± 14 | ||

| Severe | NW | 65 ± 11 | 68 ± 6 | 67 ± 9 | 73 ± 17 | |

| IUGR | 58 ± 9 | 56 ± 10§ | 45 ± 9*§# | 68 ± 14 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 61 ± 7 | 80 ± 8‡# | 74 ± 11# | 59 ± 10 |

| IUGR | 60 ± 11 | 71 ± 14# | 71 ± 16# | 64 ± 18 | ||

| Severe | NW | 63 ± 4 | 79 ± 7# | 64 ± 10 | 62 ± 11 | |

| IUGR | 62 ± 10 | 70 ± 9 | 52 ± 15 | 66 ± 8 | ||

(mmHg) (mmHg) | ||||||

| Control | NW | 40 ± 2 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 2 | 40 ± 1 | |

| IUGR | 40 ± 1 | 39 ± 2 | 40 ± 2 | 38 ± 3 | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 3 | 39 ± 2 | 37 ± 5 |

| IUGR | 40 ± 3 | 41 ± 4 | 42 ± 3 | 41 ± 3 | ||

| Severe | NW | 38 ± 2 | 37 ± 1 | 40 ± 4 | 40 ± 3 | |

| IUGR | 38 ± 1 | 36 ± 2 | 39 ± 4 | 39 ± 2 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 40 ± 4 | 75 ± 5*‡# | 80 ± 6*‡# | 39 ± 3 |

| IUGR | 40 ± 2 | 79 ± 6*‡# | 74 ± 3*‡# | 39 ± 4 | ||

| Severe | NW | 38 ± 1 | 78 ± 3*‡# | 79 ± 3*‡# | 41 ± 2 | |

| IUGR | 41 ± 4 | 75 ± 7*‡# | 75 ± 3*‡# | 43 ± 4* | ||

| Arterial pH | ||||||

| Control | NW | 7.46 ± 0.02 | 7.46 ± 0.02 | 7.46 ± 0.02 | 7.44 ± 0.02 | |

| IUGR | 7.47 ± 0.04 | 7.48 ± 0.03 | 7.45 ± 0.05 | 7.45 ± 0.05 | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 7.46 ± 0.04 | 7.46 ± 0.05 | 7.44 ± 0.05 | 7.47 ± 0.06 |

| IUGR | 7.46 ± 0.04 | 7.41 ± 0.05*# | 7.34 ± 0.07*# | 7.44 ± 0.04 | ||

| Severe | NW | 7.54 ± 0.04 | 7.43 ± 0.04# | 7.06 ± 0.08*§# | 7.51 ± 0.08 | |

| IUGR | 7.55 ± 0.02 | 7.47 ± 0.03 | 7.20 ± 0.05*†‡# | 7.43 ± 0.17 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 7.47 ± 0.04 | 7.23 ± 0.03*‡# | 7.19 ± 0.04*†‡# | 7.48 ± 0.04 |

| IUGR | 7.47 ± 0.03 | 7.17 ± 0.06*‡# | 7.17 ± 0.03*‡# | 7.44 ± 0.06 | ||

| Severe | NW | 7.49 ± 0.05 | 7.12 ± 0.04*‡§ | 6.87 ± 0.08*†‡§ | 7.46 ± 0.05 | |

| IUGR | 7.48 ± 0.05 | 7.13 ± 0.08*‡# | 6.92 ± 0.11*†‡§ | 7.41 ± 0.09 | ||

| Arterial O2 content (mmol l−1) | ||||||

| Control | NW | 6.1 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | |

| IUGR | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 0.6# | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 2.8 ± 0.5*# | 2.7 ± 0.6*# | 5.2 ± 1.0# |

| IUGR | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 0.5*# | 2.4 ± 0.4*# | 4.5 ± 0.5# | ||

| Severe | NW | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3*†# | 0.9 ± 0.2*†# | 5.0 ± 1.0 | |

| IUGR | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 0.2*†# | 0.9 ± 0.3*†# | 4.7 ± 1.2 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.7*# | 2.5 ± 0.5*# | 4.9 ± 0.8 |

| IUGR | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 0.7*# | 2.6 ± 0.5*# | 4.1 ± 0.7# | ||

| Severe | NW | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 0.1*†# | 0.7 ± 0.2*†# | 5.0 ± 1.6 | |

| IUGR | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.2*†# | 0.7 ± 0.2*†# | 4.4 ± 1.2 | ||

Values are presented as means ±s.d.

P < 0.05. indicates comparison with untreated control animals

P < 0.05. comparison within every group with baseline

P < 0.05. comparison between severity within NCH or HCH

P < 0.05. comparison between NW versus IUGR within severity

P < 0.05. comparison between NCH and HCH.

Table 3.

Effect of gradual normocapnic (NCH) and hypercapnic hypoxia (HCH) on brain haemodynamic and brain oxidative parameters in NW and IUGR piglets

| Baseline | Hypoxia 10th min | Hypoxia 50th min | Recovery 180th min | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBF (ml (100 g)−1 min−1) | ||||||

| Control | NW | 41 ± 8 | 45 ± 7 | 55 ± 13 | 53 ± 24 | |

| IUGR | 47 ± 19 | 48 ± 18 | 61 ± 21 | 75 ± 35 | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 52 ± 16 | 128 ± 52*# | 127 ± 34# | 54 ± 17 |

| IUGR | 52 ± 17 | 126 ± 87*# | 128 ± 34# | 67 ± 26 | ||

| Severe | NW | 42 ± 7 | 161 ± 48*# | 141 ± 26*# | 49 ± 13 | |

| IUGR | 40 ± 8 | 113 ± 49# | 116 ± 56# | 43 ± 13 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 45 ± 13 | 157 ± 59*# | 264 ± 90*‡# | 39 ± 13 |

| IUGR | 43 ± 17 | 194 ± 64*# | 186 ± 56*# | 56 ± 17 | ||

| Severe | NW | 51 ± 14 | 230 ± 50*# | 197 ± 36*# | 62 ± 14 | |

| IUGR | 52 ± 14 | 195 ± 55*‡# | 172 ± 87*# | 47 ± 7 | ||

| CVR (mmHg min (100 g) ml−1) | ||||||

| Control | NW | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | |

| IUGR | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.2*# | 0.6 ± 0.2*# | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| IUGR | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.3*# | 0.5 ± 0.2*# | 1.0 ± 0.5 | ||

| Severe | NW | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.1*# | 0.5 ± 0.1*# | 1.6 ± 0.5 | |

| IUGR | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.2*# | 0.5 ± 0.3*# | 1.6 ± 0.3 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.2*# | 0.3 ± 0.1*# | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| IUGR | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 0.4 ± 0.3*# | 0.4 ± 0.2*# | 1.2 ± 0.5 | ||

| Severe | NW | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.1*# | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | |

| IUGR | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.1*# | 0.5 ± 0.5*# | 1.4 ± 0.2 | ||

| CMRO2 (ml O2 (100 g)−1 min−1) | ||||||

| Control | NW | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 3.6 ± 1.2 | |

| IUGR | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 1.5 |

| IUGR | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 2.0 | 4.1 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | ||

| Severe | NW | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.5*†# | 3.0 ± 0.4 | |

| IUGR | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7*†# | 2.3 ± 0.7 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 1.5 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 0.8 |

| IUGR | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | ||

| Severe | NW | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.7*†# | 3.4 ± 0.6 | |

| IUGR | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.8*† | 2.6 ± 0.3 | ||

| Oxygen extraction ratio | ||||||

| Control | NW | 55 ± 5 | 50 ± 4 | 55 ± 4 | 53 ± 7 | |

| IUGR | 57 ± 8 | 55 ± 6 | 55 ± 9 | 50 ± 3 | ||

| NCH | Moderate | NW | 55 ± 10 | 48 ± 12 | 51 ± 13 | 54 ± 11 |

| IUGR | 54 ± 10 | 51 ± 17 | 60 ± 13‡ | 49 ± 13 | ||

| Severe | NW | 57 ± 4 | 67 ± 5*†# | 66 ± 5# | 57 ± 9 | |

| IUGR | 58 ± 6 | 68 ± 14† | 63 ± 14 | 54 ± 16 | ||

| HCH | Moderate | NW | 52 ± 10 | 23 ± 8*†‡# | 30 ± 7*†‡# | 59 ± 13 |

| IUGR | 61 ± 14 | 35± 11*†‡# | 41 ± 3# | 59 ± 15 | ||

| Severe | NW | 50 ± 7 | 55 ± 10 | 65 ± 14# | 54 ± 10 | |

| IUGR | 55 ± 10 | 73 ± 11*§# | 75 ± 11*†# | 56 ± 10 | ||

Values are presented as means ±s.d. CVR, cerebrovascular resistance.

P < 0.05. indicates comparison with untreated control animals

P < 0.05. comparison within every group with baseline

P < 0.05. comparison between severity within NCH or HCH

P < 0.05. comparison between NW versus IUGR within severity

P < 0.05. comparison between NCH and HCH.

The effects of normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia on physiological parameters are summarized in Table 2. It is shown that the relative degrees of severity (moderate versus severe) of both kinds of loading (normocapnic versus hypercapnic hypoxia) provoked similar intensities in NW as well as IUGR piglets on the related target parameters (e.g. arterial oxygen content and  ). Furthermore it was shown that newborn NW and IUGR are able to withstand a severe arterial O2 deficit (∼16–20% of baseline) for 1 h. However, in the late phase of severe hypoxia a marked reduction of arterial blood pressure occurred in IUGR piglets, in particular under normocapnic hypoxia (P < 0.05, Table 2). The expected metabolic effects (e.g. an initial respiratory acidosis in groups with hypercapnic hypoxia; a gradual increase of metabolic (lact-) acidosis in relation to severity of the O2 deficit), is reflected by a respective decrease of arterial pH and a gradual increase of arterial lactate content up to 9.9- to 10.4-fold at the end of the hypoxic load (P < 0.05). There was a similar response in corresponding NW and IUGR piglets.

). Furthermore it was shown that newborn NW and IUGR are able to withstand a severe arterial O2 deficit (∼16–20% of baseline) for 1 h. However, in the late phase of severe hypoxia a marked reduction of arterial blood pressure occurred in IUGR piglets, in particular under normocapnic hypoxia (P < 0.05, Table 2). The expected metabolic effects (e.g. an initial respiratory acidosis in groups with hypercapnic hypoxia; a gradual increase of metabolic (lact-) acidosis in relation to severity of the O2 deficit), is reflected by a respective decrease of arterial pH and a gradual increase of arterial lactate content up to 9.9- to 10.4-fold at the end of the hypoxic load (P < 0.05). There was a similar response in corresponding NW and IUGR piglets.

In the early phase of normocapnic as well as hypercapnic hypoxia a maintained CMRO2 was realized by a marked CBF increase, maintained O2 delivery and adjusted O2 utilization. Of note, the underlying compensatory mechanisms are obviously different under normocapnic or hypercapnic conditions. Indeed, whereas cerebral O2 utilization was maintained/increased under normocapnic hypoxia (P < 0.05), a significant decrease occurred during hypercapnic hypoxia (P < 0.05). However, under severe hypercapnic hypoxia IUGR piglets showed a higher amount of cerebral O2 utilization compared to NW piglets (P < 0.05). Furthermore, during the late phase of severe hypoxia cerebral O2 supply cannot be completely compensated in NW and IUGR piglets, because CMRO2 was markedly reduced under normocapnic and hypercapnic conditions (P < 0.05).

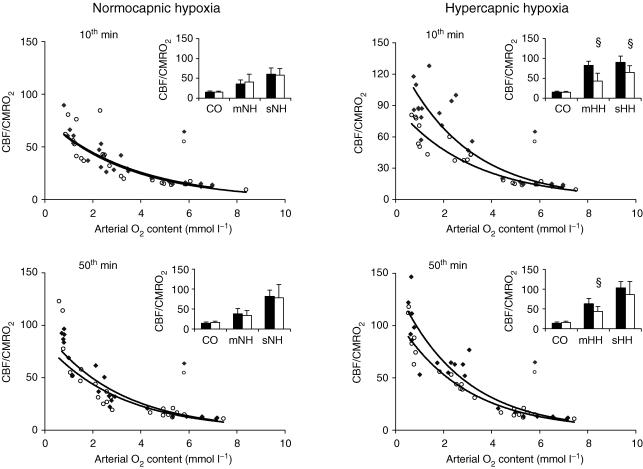

As shown in Fig. 1, there is an exponential relation between arterial O2 content and CBF response related to the O2 demand (CBF/CMRO2 ratio) under gradual normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia (P < 0.05). However, whereas under normocapnic conditions a similar index of cerebral blood supply (expressed as CBF/CMRO2 ratio) was found in NW and IUGR piglets, IUGR piglets showed in hypercapnic hypoxia a markedly reduced index of cerebral blood supply compared with NW piglets (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effect of gradual normocapnic versus hypercapnic hypoxia on CBF response normalized on brain O2 demand of normal weight (NW; n= 39, filled symbols/filled columns) and intrauterine growth-restricted (IUGR) piglets (n= 40, open symbols/open columns) in relation to the arterial oxygen content, estimated at the early phase (10th minute) and late phase (50th minute) of the O2 deficiency period. Values are presented as means +s.d.§P < 0.05, indicates comparison between NW and IUGR piglets. CO, control; mNH, moderate normocapnic hypoxia; sNH, severe normocapnic hypoxia; mHH, moderate hypercapnic hypoxia; sHH, severe hypercapnic hypoxia.

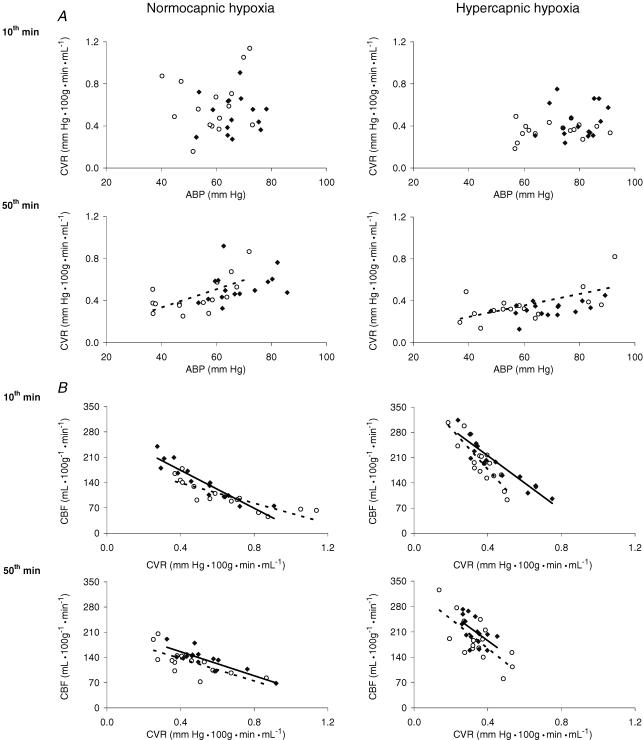

Regression analysis revealed that in NW animals ABP did not predict CVR during normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia, whereas in IURG a weak but significant regression of ABP and CVR occurred during the late phase of oxygen deficit with a coefficient of determination of 0.37–0.40 (P < 0.05, Fig. 2A). Furthermore, ABP did not predict CBF during normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia. In contrast, a strong relationship was elicited between CVR and CBF with a remarkable amount of prediction with regression coefficients almost > 0.7. In addition, during the early phase of normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia the regression line slopes of NW and IUGR values were different: whereas pure O2 deficit provoked a diminished impact of CVR on CBF in IUGR piglets, asphyxic conditions induced an enhanced effect (P < 0.05, Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Effect of gradual normocapnic versus hypercapnic hypoxia on cerebrovascular resistance (CVR) in NW (n= 31, filled symbols; regression line: continuous line) and IUGR piglets (n= 31, open symbols; regression line: dashed line) in relation to the arterial blood pressure (ABP) (A), and on cerebral blood flow (CBF) in NW (n= 31, filled symbols; regression line: continuous line) and IUGR piglets (n= 31, open symbols; regression line: dashed line) in relation to the CVR (B), estimated at the early phase (10th minute) and late phase (50th minute) of the O2 deficiency period. Note that the regression line is plotted, if the independent variable can be used to predict the dependent variable, because the respective regression coefficient was significantly different to zero (P < 0.05).

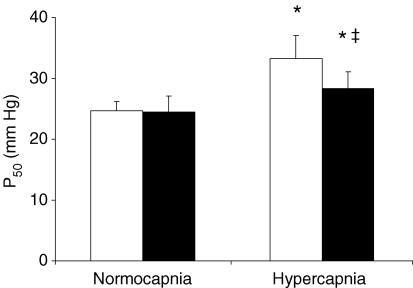

Haemoglobin affinity for oxygen is similar in whole blood of NW and IUGR piglets under normocapnic conditions. However, under hypercapnic conditions whole blood derived from IUGR piglets exhibited an increase of haemoglobin affinity for oxygen, expressed as a significant decrease of the P50 value compared to NW piglets (P < 0.05, Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of normocapnia (NW: n= 8,  = 40.2 ± 1.1 mmHg; IUGR: n= 6,

= 40.2 ± 1.1 mmHg; IUGR: n= 6,  = 40.5 ± 1.2 mmHg) and hypercapnia (NW: n= 8,

= 40.5 ± 1.2 mmHg) and hypercapnia (NW: n= 8,  = 78.4 ± 7.5 mmHg; IUGR: n= 8,

= 78.4 ± 7.5 mmHg; IUGR: n= 8,  = 81.2 ± 5.3 mmHg) on the half-saturation oxygen pressure (P50) of normal weight (NW, open columns) and intrauterine growth-restricted newborn piglets (IUGR, filled columns). Values are presented as means +s.d.*‡: P < 0.05. * indicates comparison within every group between normocapnia and hypercapnia; ‡ indicates comparison between NW and IUGR animals.

= 81.2 ± 5.3 mmHg) on the half-saturation oxygen pressure (P50) of normal weight (NW, open columns) and intrauterine growth-restricted newborn piglets (IUGR, filled columns). Values are presented as means +s.d.*‡: P < 0.05. * indicates comparison within every group between normocapnia and hypercapnia; ‡ indicates comparison between NW and IUGR animals.

Discussion

The main new finding in this study is that IUGR induces an increased ability to optimize cerebral O2 supply in neonatal asphyxia, because we could show that under hypercapnic hypoxia with combined respiratory/metabolic acidosis the cerebral O2 demand was realized by a blunted CBF increase. Indeed, whereas in the early phase of exposure a metabolically normalized CBF increase of 5.4- to 5.9-fold was necessary to maintain cerebral O2 demand at conditions of moderate or severe O2 deficit in newborn NW piglets, under similar conditions IUGR piglets were able to compensate a cerebral O2 deficit just by a 2.8- to 4.4-fold increase. Interestingly, the influence of increased  is presumably responsibe for this marked difference in response between NW and IUGR piglets. We did not find altered responsibility between newborn NW and IUGR animals under related conditions of normocapnic hypoxia. In addition, the effect was most pronounced during the early phase of hypercapnic hypoxia with only a minor impact of metabolic acidosis. The strength of alteration was gradually reduced with augmentation of metabolic disturbances and increased lactacidosis.

is presumably responsibe for this marked difference in response between NW and IUGR piglets. We did not find altered responsibility between newborn NW and IUGR animals under related conditions of normocapnic hypoxia. In addition, the effect was most pronounced during the early phase of hypercapnic hypoxia with only a minor impact of metabolic acidosis. The strength of alteration was gradually reduced with augmentation of metabolic disturbances and increased lactacidosis.

The underlying mechanisms were not addressed by these experiments. Methodological reasons for the differences between NW and IUGR animals are unlikely because the experimental conditions were similar. However, we cannot fully exclude a different sensitivity of the cerebral vasculature to the pancuronium bromide used as myorelaxant. In a high dosage with ganglion blocking activity (i.e. 0.4 mg kg−1), this drug enhances CBF autoregulation, whereas in a dose more selective for the neuromuscular junction (i.e. 0.1 mg kg−1), it does not alter CBF autoregulation in the newborn piglet (Chemtob et al. 1992). We used a dosage of 0.2 mg kg−1 h−1 in NW and IUGR piglets in order to produce sufficient myorelaxation and assume that the dosage used in the recent study did not alter the CBF response to normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia in NW animals. However, we are unable to exclude the possibility that the cerebral vasculature of IUGR animals may be more susceptible to pancuronium bromide, even if no evidence exist from our own or other studies (Bauer et al. 2004). The action time of a single dose was similar in NW and IUGR piglets.

Mild sedation by volatile anaesthetics and analgesia by nitrous oxide, as used here, appears to be adequate for the experimental approach of this study. Previous studies have shown that there is no detectable influence on cardiovascular response in newborn piglets (Gootman et al. 1978). Furthermore, CBF and cerebral O2 uptake values presented in this study were similar to values obtained from newborn piglets which were treated with other drugs for general anaesthesia that had been shown not to alter brain oxidative metabolism and from awake newborn piglets (Flecknell et al. 1983; Anday et al. 1993). In a previous study with extensive surgical preparations, including opening the abdominal cavity, craniotomy, ureter cannulization after retroperitoneal preparation and up to 5 h experimental performance, sham-operated newborn piglets showed no significant differences in arterial blood pressure and only a slight increase in heart rate (by 20%). This corresponded to a comparatively moderate increase in circulating catecholamines (adrenaline (epinephrine) by 73%, noradrenaline (norepinephrine) by 66%) (Bauer et al. 2000). This elevation in circulating catecholamines was markedly blunted compared with a rather mild hypoxic exposure. After 45 min of mild normocapnic hypoxia (arterial O2 saturation, 71 ± 8%; arterial  , 39 ± 7 mmHg) we found a marked increase in circulating catecholamines (adrenaline: by 175%; noradrenaline: by 125%) (Bauer et al. 1998a). Furthermore, during baseline conditions data were within the physiological range, consistent with other data obtained from anaesthetized newborn piglets (Lerman et al. 1990), and similar to data obtained from newborn non-anaesthetized piglets (Eisenhauer et al. 1994).

, 39 ± 7 mmHg) we found a marked increase in circulating catecholamines (adrenaline: by 175%; noradrenaline: by 125%) (Bauer et al. 1998a). Furthermore, during baseline conditions data were within the physiological range, consistent with other data obtained from anaesthetized newborn piglets (Lerman et al. 1990), and similar to data obtained from newborn non-anaesthetized piglets (Eisenhauer et al. 1994).

A mechanistic explanation for an enhanced cerebrovascular adaptation in IUGR piglets on hypercapnic hypoxia but unaltered response during normocapnic hypoxia compared to NW animals cannot be derived from the present study. In addition, no other studies are known which deal with the mechanisms underlying the regulation of cerebrovascular tone in newborn IUGR individuals. It is well known that in the newborn period CBF is also markedly influenced by arterial  as well as arterial O2 content (Wagerle & Jones, 1998). However, previous studies in newborn piglets have shown that hypoxia and hypercapnia involve different mechanisms to induce cerebral vasodilatation, which include endothelial, smooth muscle and neuroglial components (Parfenova et al. 1994; Leffler et al. 1997).

as well as arterial O2 content (Wagerle & Jones, 1998). However, previous studies in newborn piglets have shown that hypoxia and hypercapnia involve different mechanisms to induce cerebral vasodilatation, which include endothelial, smooth muscle and neuroglial components (Parfenova et al. 1994; Leffler et al. 1997).

Regression analysis revealed that an augmented cerebral vasoreactivity is probably responsible for the increased ability of IUGR piglets to optimize cerebral O2 supply in neonatal asphyxia. We verified that in IUGRs, at least during the early phase of hypercapnic hypoxia, the CVR is able to control the CBF response more tightly as indicated by a significantly steeper slope of the regression line, compared with that of NW piglets (P < 0.05). In contrast, ABP failed to have a lasting effect on CBF and CVR under these conditions, presumably because of a maintained cerebral perfusion pressure within the autoregulatory range for newborn NW and IUGR piglets (Bauer et al. 2004). The improved O2 utilization in asphyxic IUGR piglets is mainly provoked by an increased O2 extraction ratio, so that the maintenance of brain O2 demand was warranted with blunted CBF elevation. The diminished hyperperfusion is obviously crucial to the improved oxygen extraction, because a CBF rise induced by hypercapnic hypoxia led predominantly to a marked reduction of the blood transit time by ∼75% in newborn piglets. The cerebral blood volume was moderately elevated by ∼50% (Bauer et al. 1999). Both effects contribute to compromise oxygen exchange between blood and brain tissue. Therefore, a less intense response of hyperperfusion improves brain oxygen supply in asphyxic IUGR piglets.

An influence of altered haemoglobin affinity for oxygen on brain O2 supply by IUGR can be precluded because of the similarity in P50 under normocapnic conditions. Furthermore, the reduced Bohr effect (e.g. reduced P50 under hypercapnic circumstances) in blood derived from IUGR piglets results in a debased oxygen diffusibility into the brain tissue and, in turn, a possible reason for CBF elevation, when a maintained brain O2 delivery is measured (Koehler et al. 1986), as we have found in this study (Fig. 3).

We cannot address conclusively the reasons for the different response of cerebral vasculature of newborn IUGR piglets to hypercapnic hypoxia, compared to NW piglets. Nevertheless, it is obvious that the regulatory capacity of the cerebral resistance vessels is modified, i.e. hypercapnic vasodilatation is significantly reduced, leading to a restricted CBF increase but without differences in brain O2 supply. Such alterations in cerebrovascular tone can be due to the chronic effects of enhanced glucocorticoid availability during fetal development of IUGR. Recently it has been reported that dexamethasone treatment induces an increase in the tone of cerebral resistance vessels with attenuation of the hypercapnia-induced vasodilatation and enhancement of the hypocapnia-related vasoconstrictor response (Heinonen et al. 2003). A diminished release of endothelium-derived prostanoids appears to be involved (Wagerle et al. 1991), presumably by inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 itself and/or induction of phospholipase A2 inhibitory proteins (Hirata et al. 1980; Parfenova et al. 2001). Furthermore it has been shown that glucocorticoids down-regulate the expression of calcium-dependent potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle (Brem et al. 1999) and may thereby interfere with the carbon monoxide-induced vasorelaxant response shown in newborn piglets (Leffler et al. 1999).

An increased exposure to glucocorticoids is evidenced in IUGR fetuses due to disturbed placental clearance of maternal glucocorticoids. Because the concentration of circulating corticosteroid is severalfold higher in the sow than in the pig fetus (Klemcke, 1995), fetal protection against maternal corticosteroid intoxication is normally effected through conversion of physiological glucocorticoids to inactive products by placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD) (Murphy, 1981; Brown et al. 1993; Klemcke & Christenson, 1996). This may be altered during IUGR pregnancies. Placental 11β-HSD activity was markedly reduced in the late gestational period of maternal protein malnutrition sufficient to cause IUGR in rats (Langley-Evans et al. 1996b). A significant association was found in pigs between fetal or placental size and placental 11β-HSD net dehydrogenase activity (Klemcke, 2000). In addition, IUGR rats exhibited elevated liver and brain activities of specific glucocorticoid-inducible marker enzymes (Langley-Evans et al. 1996a), suggesting an increased glucocorticoid action in these organs.

In summary, this study shows that different modes of systemic hypoxia are well-tolerated in newborn piglets by sufficient compensatory redistribution of circulating blood with sustained brain O2 supply, even in animals affected by IUGR. Normocapnic and hypercapnic hypoxia induced similar consequences on brain oxidative metabolism with maintained brain O2 consumption under moderate O2 deficit and gradual decline of CMRO2 during severe hypoxia. In addition, gradual normocapnic hypoxia induces similar cerebrovascular response and brain O2 utilization in NW and IUGR piglets. However, in hypercapnic hypoxia IUGR piglets exhibited an increased brain O2 extraction compared to NW piglets resulting in a diminished CBF elevation related to brain O2 demand. Causal mechanisms for these differences are unknown. We suggest that IUGR newborns are more capable of protecting the brain against O2 loss during asphyxia (hypercapnic hypoxia) than NW neonates.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Bonn, Federal Government Germany, grants BMBF 01ZZ9104 (to R.B.). The authors thank Mrs U. Jäger, Mrs R.-M. Zimmer, and Mr L. Wunder for skilful technical assistance.

References

- Anday EK, Lien R, Goplerud JM, Kurth CD, Shaw LM. Pharmacokinetics and effect of cocaine on cerebral blood flow in the newborn. Dev Pharmacol Ther. 1993;20:35–44. doi: 10.1159/000457539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin J. Maternal influences on placental development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11:115–125. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth A. Effects of intrauterine growth retardation on mortality and morbidity in infants and young children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52(Suppl. 1):S34–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Bergmann R, Walter B, Brust P, Zwiener U, Johannsen B. Regional distribution of cerebral blood volume and cerebral blood flow in newborn piglets – effect of hypoxia/hypercapnia. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;112:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Walter B, Bauer K, Klupsch R, Patt S, Zwiener U. Intrauterine growth restriction reduces nephron number and renal excretory function in newborn piglets. Acta Physiol Scand. 2002;176:83–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2002.01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Walter B, Gaser E, Rosel T, Kluge H, Zwiener U. Cardiovascular function and brain metabolites in normal weight and intrauterine growth restricted newborn piglets – effect of mild hypoxia. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1998a;50:294–300. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(98)80009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Walter B, Hoppe A, Gaser E, Lampe V, Kauf E, Zwiener U. Body weight distribution and organ size in newborn swine (sus scrofa domestica) – a study describing an animal model for asymmetrical intrauterine growth retardation. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1998b;50:59–65. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(98)80071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Walter B, Vollandt R, Zwiener U. Intrauterine growth restriction ameliorates the effects of gradual hemorrhagic hypotension on regional cerebral blood flow and brain oxygen uptake in newborn piglets. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:639–646. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000139425.94975.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer R, Walter B, Zwiener U. Effect of severe normocapnic hypoxia on renal function in growth-restricted newborn piglets. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R1010–R1016. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.3.R1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem AS, Bina RB, Mehta S, Marshall J. Glucocorticoids inhibit the expression of calcium-dependent potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67:53–57. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RW, Chapman KE, Edwards CR, Seckl JR. Human placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: evidence for and partial purification of a distinct NAD-dependent isoform. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2614–2621. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.6.8504762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob S, Barna T, Beharry K, Aranda JV, Varma DR. Enhanced cerebral blood flow autoregulation in the newborn piglet by d-tubocurarine and pancuronium but not by vecuronium. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:236–244. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CJ, Gluckman PD, Williams C, Bennet L. Precocial neural function in the growth-retarded fetal lamb. Pediatr Res. 1988;24:600–604. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan F, Rutherford M, Groenendaal F, Eken P, Mercuri E, Bydder GM, Meiners LC, Dubowitz LM, de Vries LS. Origin and timing of brain lesions in term infants with neonatal encephalopathy. Lancet. 2003;361:736–742. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12658-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer CL, Matsuda LS, Uyehara CF. Normal physiologic values of neonatal pigs and the effects of isoflurane and pentobarbital anesthesia. Lab Anim Sci. 1994;44:245–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flecknell PA, Wootton R, John M. Cerebral blood flow and cerebral metabolism in normal and intrauterine growth retarded neonatal piglets. Clin Sci. 1983;64:161–165. doi: 10.1042/cs0640161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gluckman PD, Harding JE. The physiology and pathophysiology of intrauterine growth retardation. Horm Res. 1997;48(Suppl. 1):11–16. doi: 10.1159/000191257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootman PM, Buckley NM, Gootman N, Crane LA, Buckley BJ. Integrated cardiovascular responses to combined somatic afferent stimulation in newborn piglets. Biol Neonate. 1978;34:187–198. doi: 10.1159/000241126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen K, Fedinec A, Leffler CW. Dexamethasone pretreatment attenuates cerebral vasodilative responses to hypercapnia and augments vasoconstrictive responses to hyperventilation in newborn pigs. Pediatr Res. 2003;53:260–265. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000047524.30084.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson Smart DJ. Postnatal consequences of chronic intrauterine compromise. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1995;7:559–565. doi: 10.1071/rd9950559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata F, Schiffmann E, Venkatasubramanian K, Salomon D, Axelrod J. A phospholipase A2 inhibitory protein in rabbit neutrophils induced by glucocorticoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:2533–2536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A, Garnier Y, Berger R. Dynamics of fetal circulatory responses to hypoxia and asphyxia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;84:155–172. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kady SM, Gardosi J. Perinatal mortality and fetal growth restriction. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:397–410. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemcke HG. Placental metabolism of cortisol at mid- and late gestation in swine. Biol Reprod. 1995;53:1293–1301. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod53.6.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemcke HG. Dehydrogenase and oxoreductase activities of porcine placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Life Sci. 2000;66:1045–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00669-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemcke HG, Christenson RK. Porcine placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:217–223. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler RC, Traystman RJ, Jones MD., Jr Influence of reduced oxyhemoglobin affinity on cerebrovascular response to hypoxic hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1986;251:H756–H763. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.4.H756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Gardner DS, Jackson AA. Maternal protein restriction influences the programming of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Nutr. 1996a;126:1578–1585. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.6.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Phillips GJ, Benediktsson R, Gardner DS, Edwards CR, Jackson AA, Seckl JR. Protein intake in pregnancy, placental glucocorticoid metabolism and the programming of hypertension in the rat. Placenta. 1996b;17:169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(96)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler CW, Nasjletti A, Yu C, Johnson RA, Fedinec AL, Walker N. Carbon monoxide and cerebral microvascular tone in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H1641–H1646. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.H1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler CW, Smith JS, Edrington JL, Zuckerman SL, Parfenova H. Mechanisms of hypoxia-induced cerebrovascular dilation in the newborn pig. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;272:H1323–H1332. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.3.H1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman J, Oyston JP, Gallagher TM, Miyasaka K, Volgyesi GA, Burrows FA. The minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) and hemodynamic effects of halothane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane in newborn swine. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:717–721. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199010000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levene ML, Kornberg J, Williams TH. The incidence and severity of post-asphyxial encephalopathy in full-term infants. Early Hum Dev. 1985;11:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(85)90115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechty EA, Boyle DW, Moorehead H, Lee WH, Yang XL, Denne SC. Glucose and amino acid kinetic response to graded infusion of rhIGF-I in the late gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1999;277:E537–E543. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.3.E537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BE. Ontogeny of cortisol-cortisone interconversion in human tissues: a role for cortisone in human fetal development. J Steroid Biochem. 1981;14:811–817. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(81)90226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardi G, Cetin I, Marconi AM, Lanfranchi A, Bozzetti P, Ferrazzi E, Buscaglia M, Battaglia FC. Diagnostic value of blood sampling in fetuses with growth retardation. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:692–696. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303113281004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfenova H, Neff RA, 3rd, Alonso JS, Shlopov BV, Jamal CN, Sarkisova SA, Leffler CW. Cerebral vascular endothelial heme oxygenase: expression, localization, and activation by glutamate. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1954–C1963. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfenova H, Shibata M, Zuckerman S, Leffler CW. CO2 and cerebral circulation in newborn pigs: cyclic nucleotides and prostanoids in vascular regulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1994;266:H1494–H1501. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevell MI, Majnemer A, Morin I. Etiologic yield of cerebral palsy: a contemporary case series. Pediatr Neurol. 2003;28:352–359. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(03)00006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagerle LC, DeGiulio PA, Mishra OP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M. Effect of dexamethasone on cerebral prostanoid formation and pial arteriolar reactivity to CO2 in newborn pigs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1991;260:H1313–H1318. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.4.H1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagerle LC, Jones MD., Jr . Regulation of the fetal cerebral blood flow. In: Polin RA, Fox WW, editors. Fetal and Neonatal Physiology. 2. Philadelphia, London, Toronto, Montreal, Sydney, Tokyo: W.B. Saunders Company; 1998. pp. 933–942. [Google Scholar]

- Walter B, Bauer R, Gaser E, Zwiener U. Validation of the multiple colored microsphere technique for regional blood flow measurements in newborn piglets. Basic Res Cardiol. 1997;92:191–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00788636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw JB. Intrauterine growth retardation: adaptation or pathology? Pediatrics. 1985;76:998–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]