Abstract

A common gene variant in the heparin-binding domain (HBD) of extracellular superoxide dismutase (ECSOD) may predispose human carriers to ischaemic heart disease. We have demonstrated that the HBD of ECSOD is important for ECSOD to restore vascular dysfunction produced by endotoxin. The purpose of this study was to determine whether the gene variant in the HBD of ECSOD (ECSODR213G) protects against endothelial dysfunction in a model of inflammation. We constructed a recombinant adenovirus that expresses ECSODR213G. Adenoviral vectors expressing ECSOD, ECSODR213G or β-galactosidase (LacZ, a control) were injected i.v. in mice. After 3 days, at which time the plasma SOD activity is maximal, vehicle or endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide or LPS, 40 mg kg−1) was injected i.p. Vasomotor function of aorta in vitro was examined 1 day later. Maximal relaxation to sodium nitroprusside was similar in aorta from normal and LPS-treated mice. Maximal relaxation to acetylcholine (10−5) was impaired after LPS and LacZ (63 ± 3%, mean ±s.e.m.) compared to normal vessels (83 ± 3%) (P < 0.05). Gene transfer of ECSOD improved (P < 0.05) relaxation in response to acetylcholine (76 ± 5%) after LPS, whereas gene transfer of ECSODR213G had no effect (65 ± 4%). Superoxide was increased in aorta (measured using lucigenin and hydroethidine) after LPS, and levels of superoxide were significantly reduced following ECSOD but not ECSODR213G. Thus, ECSOD reduces superoxide and improves relaxation to acetylcholine in the aorta after LPS, while the ECSOD variant R213G had minimal effect. These findings suggest that, in contrast to ECSOD, the common human gene variant of ECSOD fails to protect against endothelial dysfunction produced by an inflammatory stimulus.

Endothelial dysfunction during many disease states appears to be mediated by reactive oxygen species (Miller et al. 1998; Gunnett et al. 2000; Nakane et al. 2000; Chu et al. 2003; Didion et al. 2004; Lund et al. 2004). We have demonstrated recently that adenovirusmediated gene transfer of human extracellular superoxide dismutase (ECSOD) improves endothelial dysfunction produced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Lund et al. 2004). ECSOD is secreted by various cells including smooth muscle, fibroblasts and macrophages, and binds to glycosaminoglycans in the vascular extracellular matrix (Marklund 1982) through the heparin-binding domain of ECSOD. Gene transfer of ECSOD with deletion of the heparin-binding domain ECSODΔHBD) fails to improve vascular function in LPS treated rats (Lund et al. 2004).

Rats have low levels of ECSOD in arteries, because the predominant form of ECSOD in rat binds poorly to the glycosaminglycans (Marklund et al. 1982). In contrast, aorta of mice (like humans and other species) contains relatively large amounts of ECSOD (Jung et al. 2003). Thus, gene transfer of ECSOD might be less effective in protection against endothelial dysfunction after LPS in mice and humans, which have higher levels of endogenous ECSOD in blood vessels. Thus, the first goal of this study was to determine whether gene transfer of ECSOD improves vascular function in mice treated with LPS.

Gene variants (or polymorphism) of human ECSOD have been reported (Folz et al. 1994; Adachi et al. 1996). One of the gene variants has a substitution of glycine for arginine at amino acid 213 (R213G) of ECSOD, within the heparin binding domain. This variant is common, as it has been described in 4–6% of populations from Japan, Sweden and Denmark (Marklund et al. 1997; Yamada et al. 2000; Juul et al. 2004). Recently, patients over age 70 with this gene variant have been reported to have a 2.3-fold increase in risk of ischaemic heart disease, or a 9-fold increase in risk when adjusted for plasma levels of ECSOD (Juul et al. 2004). Considering the prevalence of ischaemic heart disease, if the findings (Adachi et al. 1996; Juul et al. 2004) are confirmed, this gene variant may be of great importance.

We have constructed a replication-deficient adenoviral vector that expresses human ECSOD with the gene variant (ECSODR213G) (Chu et al. 2005). SOD activity is not impaired by the gene variant but binding through the HBD is reduced (Chu et al. 2005). The second goal of this study was to determine whether the gene variant alters function of ECSOD sufficiently to compromise its protective effect in a standard model of inflammation. Thus, we determined whether gene transfer of ECSODR213G protects against endothelial dysfunction after LPS in mice.

Methods

Adenoviral vectors

We used three replication-deficient adenoviruses: 1, AdCMVLacZ containing the reporter gene for β-galactosidase, was used as a control virus (Chu & Heistad 2002); 2, AdCMVECSOD, which expresses ECSOD (Chu et al. 2003); and 3, AdCMVECSODR213G, which expresses ECSOD with a polymorphism in the HBD (ECSODR213G). To produce this new virus, the cDNA from human ECSOD was modified (Chu et al. 2005). Adenoviral vectors were propagated at the Vector Core Laboratory of the University of Iowa and stored at −80°C until used.

Animals

Adult male C57BL/6J mice (20–25 g) were restrained, and adenovirus (0.1 ml of 1 × 1012 particles ml−1 in 3% sucrose in PBS) was injected in the tail vein (i.v.). Three days after viral injections, mice were treated with vehicle or LPS (E. coli serotype 0128:B12, 40 mg kg−1, i.p.). Twenty-four hours later, mice were killed by injection of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg kg−1, i.p.) followed by exsanguination.

The aorta was quickly removed and placed in cold (4°C) oxygenated Krebs solution (133 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 1.35 mm NaH2PO4, 16.3 mm NaHCO3, 0.61 mm MgSO4, 7.8 mm glucose and 2.52 mm CaCl2). Aortas were cut in rings 5–7 mm in length. All procedures and handling of animals were reviewed and approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa.

Detection of superoxide

Superoxide levels were measured by lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence as previously described (Lund et al. 2004; Chu et al. 2005). Vessel segments were placed in 0.5 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 5 μm lucigenin, and relative light units (RLU) were measured for 5 min. Background counts were determined and subtracted, RLUs were normalized to surface area. Dihydroethidine (DHE), an oxidative fluorescent dye, was used to evaluate superoxide in aorta in situ, as previously described (Lund et al. 2004).

Vasomotor responses

Aortic rings were mounted on stainless-steel hooks at optimal resting tension (0.5 g) in individual organ baths in Krebs bicarbonate solution at 37°C and aerated with 95% O2–5% CO2. Tension was periodically adjusted to the desired level during a 45 min equilibration period. Vascular rings were then precontracted with 10−5 mol l−1 PGF-2α and initially tested with 3 × 10−5 acetylcholine and washed. Vascular rings were then contracted to 50–70% of maximal contraction, with 10−5 mol l−1 PGF-2α. Responses to an endothelium-dependent vasodilator, acetylcholine (10−9–10−5 mol l−1), and an endothelium-independent vasodilator, sodium nitroprusside (10−9–10−5 mol l−1), were then examined. Responses to PGF-2α (10−9–10−5 mol l−1) were also examined. Contractile responses are expressed as grams of tension, and relaxation is expressed as a percentage of contraction produced by PGF-2α.

Drugs

Lipopolysaccharide (0128:B12), PGF-2α, acetylcholine chloride, sodium nitroprusside, and lucigenin (Sigma) were dissolved in normal saline. Hydroethidine was obtained from Molecular Probes, Inc., and suspended in dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 10−2 mol l−1.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. Inter-group comparisons were performed using analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test. Differences were considered to be significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Vasomotor responses

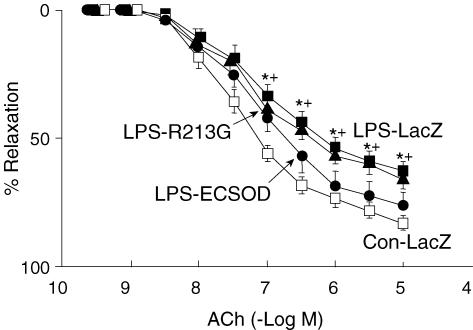

In arteries from mice treated with LacZ and given LPS, maximal relaxation to acetylcholine was significantly less (63 ± 4%) than in arteries of control mice treated with vehicle (83 ± 3%) (Fig. 1). Relaxation to acetylcholine was augmented in vessels from mice given LPS and transfected with ECSOD (76 ± 5%), compared to LacZ. In mice given LPS, AdECSODR213G did not improve responses to acetylcholine (65 ± 4%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Vasomotor responses to acetylcholine.

Relaxation of aorta to acetylcholine in control mice treated with vehicle (Con-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with LacZ (LPS-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with ECSOD (LPS-ECSOD, n= 8) and mice given LPS after transfection with ECSODR213G (LPS-R213G, n= 6). Values are means ±s.e.m.*P < 0.05 versus control. +P < 0.05 versus LPS – ECSOD.

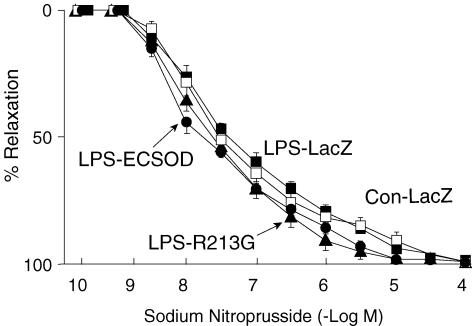

Responses to sodium nitroprusside, an endotheliumindependent vasodilator, were not altered in mice given LPS versus the control (Fig. 2). Transfection with ECSOD or ECSOD-213G did not alter the response to nitroprusside in mice given LPS.

Figure 2. Relaxation to nitroprusside.

Relaxation of aorta to nitroprusside of control mice treated with vehicle (Con-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with LacZ (LPS-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with ECSOD (LPS-ECSOD, n= 8) and mice given LPS after transfection with ECSODR213G (LPS-R213G, n= 6). Values are means ±s.e.m.

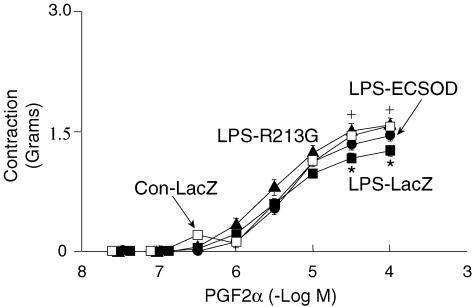

In aortic rings from mice treated with LacZ and given LPS, PGF2α produced slightly less contraction than in control mice treated with vehicle (Fig. 3). The response to PGF2α in mice given LPS after transfection with ECSOD was restored to normal. Responses in mice given LPS after transfection with AdECSODR213G were not significantly different from responses in mice given LPS after transfection with LacZ.

Figure 3. Contraction to prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α).

Contraction of aorta to F2α PGF2α in control mice treated with vehicle (Con-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with LacZ (LPS-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with ECSOD (LPS-ECSOD, n= 8), and mice given LPS after transfection with ECSODR213G (LPS-R213G, n= 6). Values are mean ±s.e.m.*P < 0.05 versus control. +P < 0.05 versus LPS-LacZ.

Superoxide levels

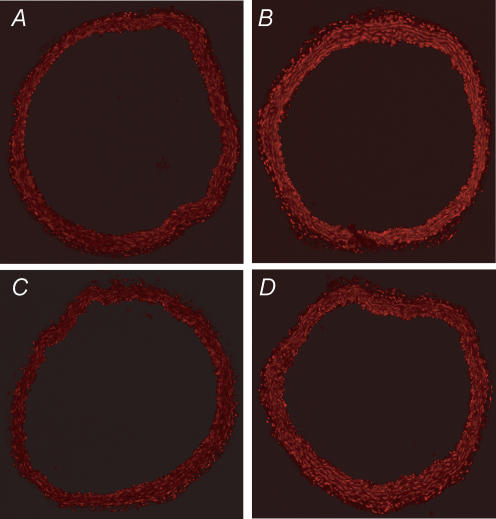

Levels of superoxide, measured by DHE fluorescence, were increased in blood vessels from LPS treated mice (Fig. 4A and B). Increased fluorescence was observed in endothelial cells, media and adventitia. In mice treated with AdECSOD and given LPS, increases in superoxide appeared to be attenuated (Fig. 4C); however, in vessels treated with AdECSODR213G and LPS, superoxide was not reduced compared to the LPS treated mice (Fig. 4D). The relative fluorescence levels for these four groups was as follows: Control 1.0, LPS 1.2 ± 0.4, LPS + ECSOD 0.8 ± 0.1, LPS + ECSODR213G 1.2 ± 0.2 (n= 3 for each group).

Figure 4. Detection of superoxide in mouse aorta in situ.

Confocal fluorescence photomicrographs of aorta incubated with DHE from control mouse (A) and LPS treated mouse (B). In aortas from control mice, fluorescence is minimal. In contrast, in LPS-treated mice, fluorescence is increased. In mice given LPS after transfection with ECSOD (C), fluorescence is minimal. In mice given LPS after transfection with ECSODR213G (D), superoxide is similar to the untreated LPS mice. Similar finding were observed in 3 mice from each group.

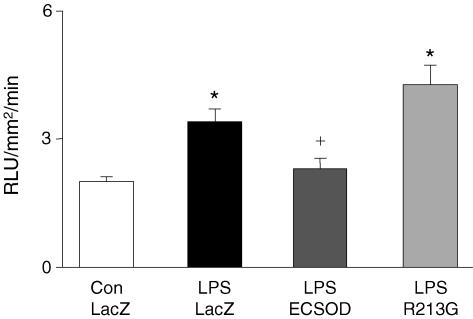

Levels of superoxide, measured with lucigenin chemiluminescence, were higher in aortas from mice treated with LacZ and given LPS than in control aortas (Fig. 5). Superoxide levels in aortas from mice treated with ECSOD and given LPS were significantly lower than LacZ treated mice. ECSODR213G treatment failed to reduce superoxide levels in the aorta. Similar results were also seen with DHE fluorescence (fig. 4).

Figure 5. Superoxide in aorta.

Superoxide levels (lucigenin) in aorta of control mice treated with vehicle (Con-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with LacZ (LPS-LacZ, n= 15), mice given LPS after transfection with ECSOD (LPS-ECSOD, n= 8) and mice given LPS after transfection with ECSODR213G (LPS-R213G, n= 6). Values are means ±s.e.m.*P < 0.05 versus control. +P < 0.05 versus LPS-LacZ.

Discussion

The major new finding in this study is that gene transfer of the human gene variant ECSODR213G fails to improve vasomotor responses after LPS, even though the enzymatic activity of ECSODR213G is normal (Adachi et al. 1996; Chu et al. 2005; Iida et al. 2006). The finding that the gene variant fails to protect against an inflammatory stimulus may have important implication in understanding mechanisms that account for the association of this common human gene variant with increased risk of ischaemic heart disease.

In addition we found that (1) relaxation to acetylcholine is impaired in aorta from mice treated with LPS, and improved by gene transfer of ECSOD, and (2) levels of superoxide, which are elevated in the aorta of mice following LPS, are decreased toward normal by gene transfer of ECSOD. These findings, although they confirm in mice our previous findings in rat (Lund et al. 2004), are important because endogenous levels of ECSOD in vessels are higher in mice than in rats.

Vasorelaxation

Impaired relaxation of arteries to acetylcholine following LPS is consistent with data from previous studies (Gunnett et al. 1998, 1999; Lund et al. 2004), and presumably is related to elevated levels of superoxide in arteries after LPS (Biguad et al. 1990; Janiszewski et al. 2002; Didion et al. 2004; Lund et al. 2004). Current data with ECSOD also suggest that superoxide is an important mediator of impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation after LPS.

We chose to study effects of acetylcholine because vasomotor responses to acetylcholine reflect endothelial release of NO. We chose to study responses to nitroprusside because responses to nitroprusside are mediated primarily by release of NO at the level of vascular muscle. The finding that relaxation to nitroprusside is normal after LPS suggests that impaired responses to acetylcholine were not produced by non-specific damage to smooth muscle in aorta. The finding that ECSOD improved responses to acetylcholine after LPS provides additional evidence that altered vasomotor responses were not due to irreversible damage to vessels.

Binding of ECSOD to extracellular surfaces of endothelium and/or vascular muscle appears to be necessary to improve endothelium-dependent relaxation after LPS. In a previous study, we found that ECSOD protein was localized to endothelium and the luminal aspect of vascular muscle following gene transfer of ECSOD (Chu et al. 2003). In the same report, levels of ECSOD were elevated in plasma, but not in vascular tissue after gene transfer of ECSODΔHBD, and ECSODΔHBD did not alter vasomotor responses in our previous study. After gene transfer of ECSOD into cerebrospinal fluid in rabbits, concentrations of ECSOD were increased in basilar arteries, and vasospasm after subarachnoid haemorrhage was attenuated (Watanabe et al. 2003). In contrast, gene transfer of ECSODΔHBD increased ECSOD in cerebrospinal fluid, but not in the cerebral arteries, and failed to protect against vasospasm. The data in this study are consistent with earlier studies, in which binding of ECSOD to vascular tissues was necessary for protective effects on vascular function.

Vasoconstriction

The finding that constriction to PGF2α in aorta tends to be reduced after LPS is consistent with several previous studies (Gunnett et al. 1998; Gunnett et al. 1999; Boyle 2000; Ulker et al. 2001). The finding that gene transfer of ECSOD improved constrictor responses to PGF2α suggests that removal of extracellular superoxide may improve contraction after LPS. The finding that gene transfer of ECSODR213G as well as ECSOD improved constrictor responses suggests that circulating levels of ECSOD, which are elevated after gene transfer of ECSODR213G (Chu et al. 2005), may be important in improving constrictor response. Thus, binding of ECSOD to the vessel wall, which is impaired by the ECSODR213G gene variant, may not be as important in constrictor responses after LPS.

Superoxide levels

The inflammatory response to LPS generates a cascade of events which includes elevation of superoxide which are thought to contribute to vasomotor dysfunction (Cuzzocrea et al. 1998). Previous studies suggest that levels of superoxide are elevated in blood vessels following LPS (Brovkovych et al. 1997; Jung et al. 2003; Javesghani et al. 2003; Gunnett et al. 2005), and pharmacological reduction of superoxide or gene transfer of ECSOD in arteries improves endothelium-dependent relaxation (Biguad et al. 1990; Rey et al. 2002; Itoh et al. 2003). We used lucigenin to quantify superoxide levels. Although lucigenin can redox cycle at high concentrations (in the range of 25 μm or higher), this has not been observed at low concentrations (5 μm) of lucigenin (Janiszewski et al. 2002). We also looked at DHE fluorescence which is especially useful for examining distribution of superoxide within the vessel wall. DHE was used in only a few mice but it appeared that superoxide levels were increased in all layers of the vessel, and tended to be reduced by ECSOD but not ECSODR213G.

Our current data support previous findings that levels of superoxide are elevated in aorta following LPS, and the increase in superoxide occurs primarily in endothelium and to a lesser extent in adventitia (Juul et al. 2004). In a previous study, we observed with immunostaining that ECSOD protein is present on endothelium in carotid arteries after administration of ECSOD (Chu et al. 2003). In the current study, ECSOD, but not ECSODR213G, reduced the levels of superoxide in arteries from LPS-treated mice. Thus, a gene variant in the heparin-binding domain appears to prevent binding to endothelium and reduction of levels of superoxide in arteries in mice that expressed ECSODR21t.

An important question is whether efficacy of infection is less with AdECSODR213G than with AdECSOD, which could provide an explanation for minimal vascular effects of AdECSODR213G. There are several reasons to suggest that AdECSOD and AdECSODR213G have similar efficiency of infection. First, equal amounts of active virus were used. The serotype and construction of virus is identical, and there is no theoretical reason for different efficiency of infection. Second, as we have shown previously in vitro (Chu et al. 2005), SOD activity in culture medium after AdECSOD versus AdECSODR213G transduced cells was equal. Because binding of ECSOD to cells is minimal, compared to the amount produced by the cells in the culture, the findings suggest that efficacy of infection by the two viruses in vitro is similar. Third, in vivo, after intravenous injection of equal amounts of viruses, the level of ECSODR213G is greater in plasma and less in blood vessels than that of ECSOD, as expected because of differences in cell-binding by the protein. The finding could be interpreted to imply that efficiency of infection is greater with AdECSODR213 than with AdECSOD (which is not likely). If efficacy of infection were greater with AdECSODR213, this would further strengthen the conclusions of this study, as we would conclude that greater protection occurs with ECSOD despite less infectivity of AdECSOD. Fourth, we presented similar findings that plasma levels of ECSOD are higher after AdECSODR213 than after AdECSOD in another paper (Iida et al. 2006). Because we have provided evidence to address this concern previously, we chose not to repeat the measurements in this study.

These data are consistent with our recent findings in LPS treated rats (Juul et al. 2004) in which gene transfer of ECSOD prevented impairment of endotheliumdependent relaxation after LPS. Protection by ECSOD required the heparin-binding domain of ECSOD, because ECSOD with the deletion of heparin binding domain failed to protect against vascular dysfunction.

We studied mice in these experiments, and rats previously (Lund et al. 2004). Rats have low levels of ECSOD activity in blood vessels because they produce an ECSOD with minimal binding of ECSOD to the vascular wall (Marklund et al. 1982). In contrast, mice have levels of ECSOD in arteries that are much higher than in rats and comparable to humans (Jung et al. 2003). It is intriguing that the amount of LPS required to produce similar impairment in the endothelial function was higher in the mouse than rat (40 mg kg−1versus 10 mg kg−1 LPS). We speculate that greater susceptibility of rats than mice to endothelial dysfunction after LPS may be related in part to low levels of endogenous ECSOD levels in rats. Nevertheless, gene transfer of ECSOD prevented endothelial dysfunction in mice as well as rats.

The rationale for this study focuses on effects of the R213G gene variant on the aorta, not on resistance vessels. In a previous study of hypertensive rats (Chu et al. 2005), we found that ECSOD not only protects against oxidative stress in the aorta, but also has important effects on arterial pressure, presumably from effects on resistance vessels. In our previous study of hypertension (Chu et al. 2005), it clearly was important to study resistance vessels as well as the aorta. In this study, however, the focus was on effects of oxidative stress and inflammation on the aorta, not resistance vessels.

Limitations of the study

We considered performing studies in vivo, including measurements of arterial pressure before the animals were killed, but decided that measurements of arterial pressure during anaesthesia would be of limited value, because they would be especially susceptible to changes in intravascular volume after LPS. We also considered the possibility of inserting catheters before injection of LPS and measuring arterial pressure in unanaesthetized animals; however, it may also be difficult to interpret those findings, because of changes in water intake and intravascular volume, as well as neurohumoral changes. Because these measurements were not obtained, it is important to be cautious about whether the changes we observed ex vivo are directly relevant to effects on blood pressure.

We should also point out that the goal of this study did not relate primarily to haemodynamic effects of LPS. Our goal was to determine whether ECSODR213G modulates effects of inflammation produced by LPS on vasomotor responses of a large artery that is susceptible to vascular diseases, including atherosclerosis. The rationale was based on previous studies linking the R213G gene variant to increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Juul et al. 2004). Thus, the absence of measurements of blood pressure does not detract from the primary conclusion of this study – that the ECSOD gene variant fails to protect against endothelial dysfunction of the large artery produced by an inflammatory stimulus.

Implications of these findings

The finding that gene transfer of ECSODR213G failed to improve vasomotor function after LPS suggests that the R213G gene variant impairs binding of ECSOD to vessels sufficiently to interfere with a protective effect of the antioxidant enzyme. One possible explanation for the data may be a change in the redox state of the mice. In our previous paper (Iida et al. 2006), AdECSOD did not potentiate endothelium-dependent responses in normal rats, presumably with a balanced redox state. Because levels of endogenous ECSOD are much higher in vessels from mice than rats, protection by additional ECSOD from gene transfer in normal mice would be even less likely in vessels from normal mice than from normal rats.

The findings in this study may be of clinical importance, because the R213G polymorphism within the HBD has been described in humans (Marklund et al. 1997; Yamada et al. 2000; Juul et al. 2004). The variant may disrupt electrostatic binding between the six positively charged amino acids of the HBD to the negatively charged heparan sulphate on the cell surface, and thereby prevent the enzyme from binding to the arterial wall. Accordingly, despite high levels of active enzyme in plasma, levels of ECSOD in the vessel wall may be greatly reduced.

The R213G gene variant is expressed in 4–6% of the population in Sweden, Denmark and Japan (Marklund et al. 1997; Yamada et al. 2000; Juul et al. 2004). Individuals with the gene variant have an 8- to 10-fold increase in the level of ESCOD in their plasma. The risk of ischaemic heart disease is 9-fold higher in aged R213G carriers than in non- carriers, when adjusted for plasma ECSOD levels (Jung et al. 2003). The finding suggests that binding of ECSOD to the vessel wall may be an important factor in prevention of ischaemic heart disease or its complications.

The findings in the present study support our previous finding in hypertensive rats that ECSODR213G fails to protect against endothelial dysfunction during hypertension (Chu et al. 2005). Furthermore we have demonstrated recently that, in contrast to ECSOD, gene transfer of ECSODR213G in rats with heart failure has minimal beneficial effects in protection against oxidative stress, endothelial function, or basal bioavailability of NO (Iida et al. 2006).

In order to alter vasomotor function, viruses do not need to transduce the vessel that is studied. Virtually all adenoviruses are removed by the liver in mice after i.v. injection (Nicol et al. 2004). Thus relatively few virions pass through the liver and directly infect blood vessels. This has been a major obstacle in previous studies in which viruses are injected i.v. to alter blood vessels, because the viruses fail to infect blood vessels and thus fail to transfer a gene (Miller et al. 2005). In this study, we took advantage of the fact that both ECSOD and R213G proteins are synthesized in the liver after i.v. injection of the adenoviruses, and then secreted in large amounts into the blood.

The frequency of the R231G variant in haemodialysis patients is higher than in the normal population (19%versus 6%), and there is a significant increase in mortality among diabetics with the R213G variant compared to diabetics with normal ECSOD (Yamada et al. 2000). Thus, ECSOD may be especially important as an antioxidant in patients with high levels of oxidative stress, such as diabetes and haemodialysis. We speculate that when subjects with the gene variant are exposed to high oxidative stress, such as during endotoxaemia, effects of the gene variant may be unmasked.

In conclusion, vasorelaxation in response to acetylcholine is impaired by LPS and restored by gene transfer of ECSOD. Because ECSOD is an extracellular enzyme (Fukai et al. 2002), extracellular superoxide appears to be a key mediator of vascular dysfunction following LPS. Data in this study demonstrate protection of endothelium-dependent relaxation in arteries during inflammation by antioxidant effects of ECSOD in mice, which have endogenous ECSOD levels that are comparable to humans but higher than rats. Most importantly, findings with ECSODR213G may suggest that the gene variant may lead an augmented risk factor in the vasomotor responses to endotoxaemia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Arlinda LaRose for secretarial assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants HL 62984, HL 16066, NS 24621, HL 38901, DK 54759, funds from the Department of Veterans Affairs, and funds from a Carver Trust Research Program of Excellence of the University of Iowa.

References

- Adachi T, Yamada H, Yamada Y, Morihara N, Yamazaki N, Murakami T, Futenma A, Kato K, Hirano K. Substitution of glycine for arginine-213 in extracellularsuperoxide dismutase impairs affinity for heparin and endothelial cell surface. Biochem J. 1996;313:235–239. doi: 10.1042/bj3130235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biguad M, Julou-Schaeffer G, Parratt JR, Stoclet JC. Endotoxin-induced impairment of vascular smooth muscle contractions elicited by different mechanisms. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;190:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94125-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle WA, 3rd, Parvathaneni LS, Bourlier V, Sauter C, Laubach VE, Cobb JP. iNOS gene expression modulates microvascular responsiveness in endotoxin-challenged mice. Circ Res. 2000;87:E18–E24. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.7.e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Alwahdani A, Iida S, Lund DD, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Effects of gene variant of extracellular superoxide dismutase in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation. 2005;112:1047–1053. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Heistad DD. Gene transfer to blood vessels using adenoviral vectors. Methods Enzymol. 2002;346:263–276. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)46060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y, Iida S, Lund DD, Weiss RM, DiBona GF, Watanabe Y, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Gene transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase reduces arterial pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats: role of heparin-binding domain. Circ Res. 2003;92:461–468. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000057755.02845.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzocrea S, Zingarelli B, O'Connor M, Salzman AL, Szabo C. Effect of 1-buthionine-(S,R) -sulphoximine, an inhibitor of γ-glutamylcysteine synthase on peroxynitrite- and endotoxic shock-induced vascular failure. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:525–537. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Fegan PE, Didion LA, Faraci FM. Overexpression of CuZn-SOD prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced endothelial dysfunction. Stroke. 2004;36:1963–1967. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000132764.06878.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folz RJ, Peno-Green L, Crapo JD. Identification of a homozygous missense mutation (Arg to Gly) in the critical binding region of human EC-SOD gene (SOD3) and its association with dramatically increased serum enzyme levels. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:2251–2254. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.12.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukai T, Folz RJ, Landmesser U, Harrison DG. Extracellular superoxide dismutase and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnett CA, Berg DJ, Faraci FM, Feuerstein G. Vascular effects of lipopolysaccharide are enhanced in interleukin-10- deficient mice. Stroke. 1999;30:2191–2196. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.10.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnett CA, Chu Y, Heistad DD, Loihl A, Faraci FM. Vascular effects of LPS in mice deficient in expression of the gene for inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H416–H421. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnett CA, Heistad DD, Berg DJ, Faraci FM. IL-10 deficiency increases superoxide and endotheli1al dysfunction during inflammation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1555–H1562. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.4.H1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnett CA, Lund DD, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Vascular interleukin-10 protects against LPS-induced vasomotor dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H624–H630. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01234.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Chu Y, Weiss RM, Kang YM, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Vascular effects of a common gene variant of extracellular superoxide dismutase in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H914–H920. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00080.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh T, Kajikuri J, Hattori T, Kusama N, Yamamoto T. Involvement of H2O2 in superoxide-dismutase-induced enhancement of endothelium-dependent relaxation in rabbit mesenteric resistance artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:444–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiszewski M, Souza HP, Liu X, Pedro MA, Sweier JL, Laurindo FR. Overestimation of NADP-driven vascular oxidase activity due to lucigenin artifacts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;31:446–453. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javesghani D, Hussain SN, Scheidel J, Quinn MT, Magder SA. Superoxide production in the vasculature of lipopolysaccharide-treated rats and pigs. Shock. 2003;19:486–493. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000054374.88889.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung O, Markland SL, Geiger H, Pedrazzini T, Busse R, Brandes RP. Extracellular superoxide dismutase is a major determinant of nitric oxide bioavailability. In vivo and ex vivo evidence from ecSOD-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2003;93:622–629. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000092140.81594.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juul K, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Marklund S, Heegaard NH, Steffensen R, Sillesen H, Jensen G, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically reduced antioxidative protection and increased ischemic heart disease risk: The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;109:59–65. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105720.28086.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund DD, Gunnett CA, Chu Y, Brooks RM, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Gene transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase improves relaxation of aorta after treatment with endotoxin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H805–H811. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00907.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund S. Human copper-containing superoxide dismutase of high molecular weight. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.24.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund SL, Holme E, Hellner L. Superoxide dismutase in extracellular fluids. Clin Chim Acta. 1982;126:41–51. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(82)90360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund SL, Nilsson P, Israelsson K, Schampi I, Peltonen M, Asplund K. Two variants of extracellular-superoxide dismutase: relationship to cardiovascular risk factors in an unselected middle-aged population. J Intern Med. 1997;242:5–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WH, Brosnan MJ, Graham D, Nicol CG, Morecroft I, Channon KM, Danilov SM, Reynolds PN, Baker AH, Dominiczak AF. Targeting endothelial cells with adenovirus expressing nitric oxide synthase prevents elevation of blood pressure in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Mol Ther. 2005;12:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FJ, Jr, Gutterman DD, Rios CD, Heistad DD, Davidson BL. Superoxide production in vascular smooth muscle contributes to oxidative stress and impaired relaxation in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 1998;82:1298–1305. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.12.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakane H, Miller FJ, Jr, Faraci FM, Toyoda K, Heistad DD. Gene transfer of endothelial nitric oxide synthase reduces angiotensin II-induced endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 2000;35:595–601. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol CG, Graham D, Miller WH, White SJ, Smith TA, Nicklin SA, Stevenson SC, Baker AH. Effects of adenovirus serotype 5 fiber and penton modifications on in vivo tropism in rats. Mol Ther. 2004;10:344–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey FE, Li XC, Carretero OA, Garvin JL, Pagano PJ. Perivascular superoxide anion contributes to impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation: Role of gp91 (phox) Circulation. 2002;106:2497–2502. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038108.71560.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulker S, Cinar MG, Can C, Evinc A, Kosay S. Endotoxin-induced vascular hyporesponsiveness in rat aorta: in vitro effect of aminoguanidine. Pharmacol Res. 2001;44:22–27. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Chu Y, Andresen JJ, Nakane H, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Gene transfer of extracellular superoxide dismutase reduces cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2003;34:434–440. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000051586.96022.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Yamada Y, Adachi T, Fukatsu A, Sakuma M, Futenma A, Kakumu S. Protective role of extracellular superoxide dismutase in hemodialysis patients. Nephron. 2000;84:218–223. doi: 10.1159/000045580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brovkovych V, Patton S, Brovkovych S, Kiechle F, Huk I, Malinski T. In situ measurement of nitric oxide, superoxide and peroxynitrite during endotoxemia. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1997;48:633–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]