Abstract

Stochastic vestibular stimulation (SVS) can be used to study the postural responses to unpredictable vestibular perturbations. The present study seeks to determine if stochastic vestibular stimulation elicits lower limb muscular responses and to estimate the frequency characteristics of these vestibulo-motor responses in humans. Fourteen healthy subjects were exposed to unpredictable galvanic currents applied on their mastoid processes while quietly standing (±3 mA, 0–50 Hz). The current amplitude and stimulation configuration as well as the subject's head position relative to their feet were manipulated in order to determine that: (1) the muscle responses evoked by stochastic currents are dependent on the amplitude of the current, (2) the muscle responses evoked by stochastic currents are specific to the percutaneous stimulation of vestibular afferents and (3) the lower limb muscle responses exhibit polarity changes with different head positions as previously described for square-wave galvanic vestibular stimulation (GVS) pulses. Our results revealed significant coherence (between 0 and 20 Hz) and cumulant density functions (peak responses at 65 and 103 ms) between SVS and the lower limbs' postural muscle activity. The polarity of the cumulant density functions corresponded to that of the reflexes elicited by square-wave GVS pulses. The SVS–muscle activity coherence and time cumulant functions were modulated by current amplitude, electrode position and head orientation with respect to the subject's feet. These findings strongly support the vestibular origin of the lower limb muscles evoked by SVS. In addition, specific frequency bandwidths in the stochastic vestibular signal contributed to the early (12–20 Hz) and late components (2–10 Hz) of the SVS-evoked muscular responses. These frequency-dependent SVS-evoked muscle responses support the view that the biphasic muscle response is conveyed by two distinct physiological processes.

Galvanic vestibular stimulation (GVS) has long been used as a means to probe the human vestibular system and assess its contributions to posture and gait (Coats, 1973; Nashner & Wolfson, 1974; for review see Fitzpatrick & Day, 2004). When applied in a binaural bipolar configuration, GVS increases the firing rate of the vestibular afferents on the cathodal side and decreases the firing rate of the afferents on the anodal side (Goldberg et al. 1984; Goldberg, 2000). In quietly standing humans, the net effect of bilateral bipolar GVS is a postural adjustment towards the anode which may be modified through changes in sensory input (Lund & Broberg, 1983; Fitzpatrick et al. 1994; Day et al. 1997; Wardman et al. 2003). Correspondingly, GVS elicits well-defined electromyographic (EMG) responses in posturally active muscles, such as soleus and gastrocnemius muscles (Nashner & Wolfson, 1974; Iles & Pisini, 1992; Britton et al. 1993; Fitzpatrick et al. 1994). The postural and lower limb vestibulo-myogenic responses are modified by several factors such as head position (Lund & Broberg, 1983; Iles & Pisini, 1992; Britton et al. 1993), sensory feedback (Britton et al. 1993; Welgampola & Colebatch, 2001; Welgampola & Day, 2006), stimulation parameters (Nashner & Wolfson, 1974; Day et al. 1997; Cauquil & Day, 1998; Rosengren & Colebatch, 2002) and amplitude of background electromyographic (EMG) activity (Watson & Colebatch, 1998; Lee Son et al. 2005). The aforementioned factors modifying the vestibular-evoked muscle responses have been described using square-wave GVS pulses. Although postural and muscular responses are evoked by random vestibular signals, the distinct oscillatory nature of vestibular afferent projection onto motoneurons is not fully understood.

The use of stochastic vestibular stimulation (SVS) in place of the more traditional square-wave or sinusoidal GVS signals has received the attention of a number of researchers (Fitzpatrick et al. 1996; Pavlik et al. 1999; Scinicariello et al. 2001; MacDougall et al. 2006; Moore et al. 2006). In addition to benefits deriving from a signal without bias from expectancy effects (Pavlik et al. 1999), a multi-frequency stochastic signal can estimate – through coherence analyses – the transfer function between the SVS signals and the postural or muscle responses. Typically, researchers have used SVS signals composed of frequencies less than 5 Hz to analyse the effects of SVS on postural and muscular responses (Fitzpatrick et al. 1996; Pavlik et al. 1999; Scinicariello et al. 2001; MacDougall et al. 2006; Moore et al. 2006). Using SVS signals with a frequency content below 5 Hz is justified when examining postural responses but may prove limited when assessing muscular responses. Indeed, oscillations in the GVS-evoked muscle responses have been observed around 6–7 Hz (Fitzpatrick et al. 1994), while inter-muscular coherence analyses have revealed specific bandwidths of interaction between cortical (15–32 Hz) or subcortical centres (10–20 Hz) and limb motoneurons (Halliday et al. 2000; Kilner et al. 2000; Grosse & Brown, 2003). The aim of the current study was to assess if lower limb muscle responses could be elicited using a stochastic vestibular signal with a large bandwidth (0–50 Hz) and to compare these responses to those elicited by square-wave GVS pulses. To unveil the correlation in the time and frequency domain between the SVS and muscle responses, we constructed estimates of linear correlation between processes with a Fourier-based algorithm using the method of disjoint sections (Halliday et al. 1995). This method allows the computation of confidence intervals of parameter estimates, providing a statistical framework to test if the correlation estimates in the time and frequency domains are statistically greater than that expected by chance.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that stochastic vestibular signals evoke lower limb muscle responses. To ascertain the vestibular origin of the muscular responses elicited by SVS, these lower limb muscle responses must exhibit characteristics matching those observed following square-wave pulses. We estimated the coherence, time cumulant and phase between SVS and lower limb muscle activity to assess three specific hypotheses: (1) the muscle responses evoked by stochastic currents will be dependent on the amplitude of the SVS current and specific to the percutaneous stimulation of vestibular afferents; (2) the SVS-evoked muscle responses will exhibit polarity changes with different head positions as previously described for square-wave GVS pulses; and (3) the coherence estimates will exhibit peaks in specific bandwidths that are related to the biphasic characteristics of the SVS-evoked muscle response. Our results support all three hypotheses and demonstrate convincingly the capacity to elicit vestibulo-myogenic responses in lower limb muscles with SVS.

Methods

Subjects

Fourteen healthy subjects (9 male, 5 female, average height 175 cm ± 14.8 cm) between the ages of 21 and 45 years, with no known history of neurological disease or injury participated in this study. For each subject the experimental protocol was explained and their written, informed consent was obtained. All procedures used in this study conformed to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the University of British Columbia's clinical research ethics board.

Stimulus

Vestibular stimulation was delivered using carbon rubber electrodes (9 cm2) in a bipolar electrode configuration with electrodes placed either binaurally or in a split configuration (control condition). For the binaural configuration, the two electrodes were secured over the mastoid processes with an elastic headband. For the split configuration, one electrode was secured with adhesive tape over the seventh cervical vertebra while the second electrode was positioned over the forehead with an elastic headband. Electrodes were coated with electrode gel (Spectra 360, Parker Laboratories, Fairfield, USA). Three distinct vestibular signals were created for this study: two stochastic signals and a square-wave pulse signal. The stimuli were generated on a PC computer with Spike2 software (stochastic 0–50 Hz, RMS value of 1.10 mA, and square-wave pulses; Cambridge Electronics Design, Cambridge, UK) or Labview software (stochastic 0–35 Hz, RMS value of 0.91 mA; National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) and sent through the analog output of a Micro-1401 interface (Cambridge Electronics Design). The 0–35 Hz stochastic signal was used only for a control condition and created after we observed no coupling between SVS and muscular activity in the 35–50 Hz bandwidth. Subsequently, the stochastic signal was passed through an analog low-pass filter (Neurolog NL-900D, Filter NL 136, Digitimer) with a 50 Hz cut-off. Stochastic signals had a duration of 60 s and a peak amplitude of ±3 mA (or ±0.3 mA for one control stochastic SVS condition). Square-wave GVS pulses had a 30 ms duration and 3 mA amplitude; the anode right–cathode left and cathode right–anode left configurations were randomly presented with an inter-stimulus interval varying between 300 and 556 ms. For all conditions, a constant-current analog stimulus isolation unit (Model 2200 Analog Stimulus Isolator: AM Systems, Carlsborg, WA, USA) was used to isolate and transform the electrical signals prior to the stimulating electrodes.

Protocol

Participants stood on a force plate (Bertec 4060-80: Bertec Corp., Columbus, OH, USA) with their eyes open and feet 2–3 cm apart (inter-malleoli distance). Participants were required to focus at a point on a wall located 2 m in front of them to insure they maintained their head pitch and yaw orientation as stable as possible, with the Frankfurt plane parallel relative to the floor (Cathers et al. 2005). The centre of foot pressure (COP) was computed using the moments (Mx and My) and vertical force (Fz) signals from the force platform. During each trial, participants were asked to keep their arms at their sides and to minimize extraneous body movements. The experimental procedure consisted of six trial conditions. To address our first hypothesis two control conditions were created. The first control condition consisted of ±3 mA bipolar split configuration stochastic signal (0–35 Hz) with the head facing forward (HF). The split configuration (electrodes on the forehead and C7) was intended to stimulate only cutaneous receptors thereby controlling for possible cutaneous-related responses. The second control condition consisted of a ±0.3 mA bilateral binaural stochastic signal (0–50 Hz) with the head facing forward (HF). This condition controlled for the known effect of GVS current amplitude on lower limb myogenic responses. Muscle responses to square-wave GVS are optimally observed with current amplitudes equal to or greater than 2 mA (Fitzpatrick et al. 1994; Ali et al. 2003) but may be produced at currents of less than 2 mA (Britton et al. 1993). To address our second hypothesis ±3 mA stochastic vestibular signal was delivered in a bilateral bipolar configuration (0–50 Hz) with three different head positions relative to the feet: head forward (HF), head left (HL) and head right (HR). An additional trial with the head facing forward was delivered to participants using square-wave pulses (3 mA) in a bilateral bipolar configuration. This condition enabled a direct comparison of muscular responses elicited by the stochastic and square-wave vestibular stimuli. By convention, the vestibular signal was positive for anode right currents and negative for cathode right currents. Each of the SVS trials was repeated three times, with each trial lasting 1 min. The square-wave condition was presented as a single 5 min trial consisting of 760 30-ms GVS perturbations (380 anode right–cathode left: anode right configuration; 380 anode left–cathode right: cathode right configuration). Trial order was randomized with the exception of the split configuration trials which were grouped as three consecutive 1 min trials (due to the change in electrode placement), but interspersed randomly within the rest of the randomized trial conditions. For each condition, 10 individuals were subjected to the SVS. The forehead–C7 and square-wave GVS control conditions were performed on different days and involved the testing of additional subjects, yielding a total of 14 volunteers. Rest periods were provided at the request of the participant to avoid any signs of fatigue.

Electromyography and signal analysis

Surface EMG was collected bilaterally from soleus, medial head of gastrocnemius, and lateral head of the gastrocnemius. Self-adhesive Ag–AgCl surface electrodes (Soft-E H59P: Kendall-LTP, Chicopee, MA, USA) were placed on the skin along the length of the specified muscle with an inter-electrode distance of 12 mm. EMG was amplified, band-pass filtered from 30 Hz to 1000 Hz (Grass P511, Grass-Telefactor, West Warwick, USA), and digitized at 5 kHz (Micro 1401, Cambridge Electronic Design). The signals from the force platform and the vestibular stimulus were digitized, respectively, at 0.5 and 5 kHz (Micro 1401).

Digitized EMG during the square-wave trials were full-wave rectified offline and trigger averaged to the GVS pulse onset using Matlab 6.5 software (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). Trigger averages were analysed from 50 ms prior to GVS pulse onset to 300 ms post-GVS pulse onset.

Digitized EMG recorded during the 1 min stochastic SVS trials was time-locked to SVS onset and concatenated within each condition for each participant. Concatenated data from each participant were then further concatenated across all participants creating a single pooled data array for each condition. Pooled EMG data were full-wave rectified and the auto-spectra for the SVS and muscles (fAA(λ) and fBB(λ) respectively) as well as the cross-spectrum (fAB(λ)) were computed for each muscle (λ denotes frequency). Coherence functions (|RAB(λ)|2) between the SVS signal and EMG were estimated for each trial condition within each participant and across all participants using eqn (1). The coherence analyses between the stochastic vestibular signals and lower limb EMG enabled the identification of correlated frequencies between the two signals. In addition, cumulant density estimates and analysis of the phase between the stochastic SVS and EMG signals provided information regarding the time-domain characteristics of the identified coherent frequencies.

| (1) |

Coherence is a measure of the linear relationship between two processes across various frequencies. Similar to correlation, coherence is a unit-less measure bounded between 0 and 1, with 1 indicating a perfect linear relationship and 0 indicating independence (Rosenberg et al. 1989; Halliday et al. 1995; Amjad et al. 1997). Estimation of coherence was performed using a Matlab script based on the method described by Rosenberg et al. (1989). For the single subject coherence analysis, data were broken down into 219 disjoint sections yielding a frequency resolution of 1.22 Hz (0.8192 s segment−1); for the pooled coherence analysis, data were broken down into 2197 disjoint sections, also with a frequency resolution of 1.22 Hz. Frequency-specific coherence was determined significant when values exceeded a 95% confidence limit derived from the number of disjoint segments used in the coherence estimate as described by Halliday et al. (1995). The cumulant density estimate between the stochastic vestibular signal and each of the recorded muscles was determined. Cumulant density functions can be described as the inverse Fourier transform of the cross spectrum estimate (Brillinger, 1974; Rosenberg et al. 1989). The cumulant density function provides a time domain measure of the relationship between two processes, similarly to a cross-correlation histogram (Amjad et al. 1997). A 95% confidence interval (with positive and negative limits) was computed for the cumulant density estimate in accordance with Halliday et al. (1995). Due to the positive vestibular signals for anode right currents, a positive cumulant density function indicates that anode right currents induced a facilitation of the muscle response. The cumulant density functions were estimated to determine the onset and peak of the SVS-evoked responses. The onset (and reversal of polarity) of SVS-evoked muscle activity was determined using a log-likelihood ratio algorithm (Staude & Wolf, 1999; Staude, 2001) and then confirmed visually. In addition, the time-cumulant density functions were used to determine whether the stochastic vestibular signals yielded polarity changes in the SVS-evoked reflexes with varying head positions. Phase estimates between the SVS signal and muscular activity were estimated from the complex valued coherency function (coherence is the square of the absolute value of the coherency (Amjad et al. 1997)). These phase estimates were of particular interest to infer the relationship between the significant frequency bandwidths in the coherence function and the time domain estimation of the biphasic SVS-evoked muscle responses (short and medium latency). For pre-defined regions of significant coherence, regression analysis was used to determine the slope of the phase values over the range of significant coherent values. The slope of the phase estimates indicates the delay (lag or advance) between the SVS and EMG signals for a certain frequency bandwidth. The slope values were multiplied by 1000/2π to provide an estimate of the phase lag (in milliseconds) of the specified regions of significant coherence.

The coherence estimates allow for simple statistical comparisons between various conditions. Significant changes in coherence between the different SVS conditions (e.g. effect of head position) were identified using a difference of coherence test (DoC) (Amjad et al. 1997). The DoC was applied on Fisher transformed coherence values, evaluated for the 0–40 Hz bandwidth and compared to a χ2 distribution with k– 1 degrees of freedom (k is the number of experimental conditions) (Amjad et al. 1997; Blouin et al. 2006). A significance level of P ≤ 0.05 was chosen.

Results

Participants commented on the cutaneous sensation of the stochastic signal but did not report a specific perception of postural movement during the stochastic vestibular stimuli. A common remark following SVS was that the stimulus was slightly ‘prickly’ at the start of the trial but this sensation seemed to dissipate soon after trial initiation.

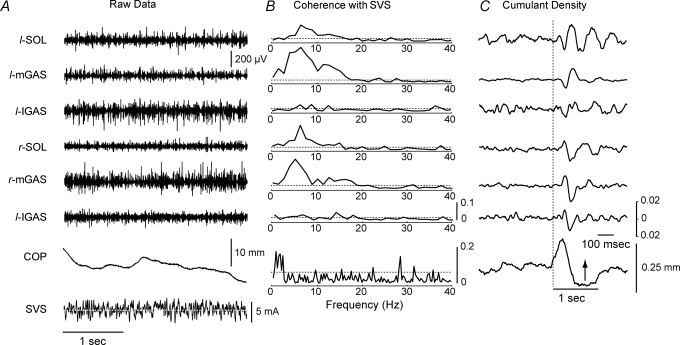

Visual inspection of corresponding EMG and SVS signal did not exhibit obvious patterns of covariance (Fig. 1A). Coherence estimates, however, showed significant SVS–EMG coupling in the 0–20 Hz bandwidth with well-defined peaks at 5–7 Hz and 11–16 Hz (Fig. 1B). Overall, approximately 5–15% of the variability in muscle activity could be explained by the variability in the SVS signal. This coupling was stronger in the soleus and medial head of the gastrocnemius compared with the lateral gastrocnemius. For the SVS-evoked postural responses, SVS–COP coupling was observed predominantly in the 0–3 Hz frequency range with sporadic peaks observed occasionally at higher frequencies (Fig. 1B). The cumulant density estimate between the SVS and muscles displayed similar characteristics to the previously reported biphasic muscular response evoked by square-wave GVS pulses. The muscular responses evoked by the SVS lagged the vestibular signal by approximately 50 ms (Fig. 1C) and appeared largest in the medial gastrocnemius and smallest in the lateral gastrocnemius.

Figure 1.

Raw data from a single subject exposed to SVS with the head facing forwards A, 3 s of raw data comprising EMG for the six measured muscles, medio-lateral centre of foot pressure (COP) and SVS (horizontal dashed line indicates 0 mA mark for SVS). B, corresponding coherence plots for each of the six muscle groups. The bottom plot is the coherence plot between the SVS and the COP trace. Coherence exhibited between the SVS–EMG signals is localized between 1 and 20 Hz and coherence between the SVS–COP signals is localized in the 0–3 Hz bandwidth. Horizontal dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence limit. C, cumulant density estimates for the six measured muscles displaying a biphasic response. The bottom plot shows changes in COP associated with the SVS (note the different time scale for this plot; arrow indicates movement of COP to the left). COP, centre of pressure; SVS, stochastic vestibular stimulation; SOL, soleus; mGAS, medial head of gastrocnemius; lGAS, lateral head of gastrocnemius; l, left; r, right.

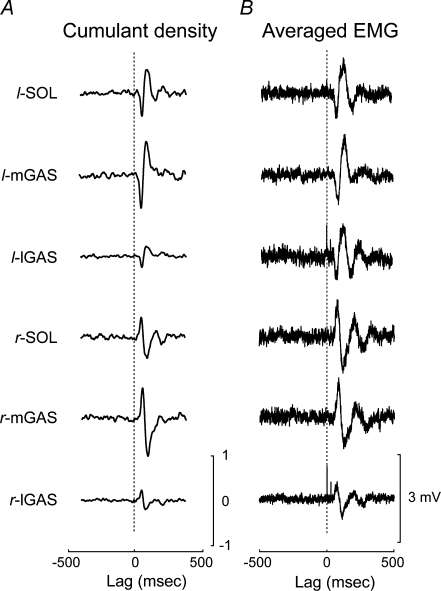

Pooled coherence between the SVS and EMG activity reached significant levels in all muscles for the 3 mA HF bilateral binaural SVS condition (n = 10; Fig. 2). Coherence was localized in the 0–20 Hz bandwidth with distinct peaks between 5–7 and 11–16 Hz. Conversely, the 0.3 mA HF bilateral binaural SVS condition and the 3 mA HF split condition exhibited coherence values that remained below the 0.95 confidence interval across all frequencies. The cumulant density estimates exhibited the same pattern. Significant peaks and troughs were observed for the 3 mA HF bilateral binaural condition, but not for the 0.3 mA or split configuration SVS.

Figure 2.

Pooled comparison of 3 mA head forward condition with 0.3 mA and split head forward conditions A, pooled (n = 10) coherence plots for each of the six lower limb muscles comparing the 3 mA head forward, 0.3 mA head forward and the 3 mA head forward split electrode conditions. Horizontal dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence limit. Significant coherence levels were observed only for the 3 mA head forward condition. B, pooled (n = 10) cumulant density estimates for each of the six lower limb muscles comparing the 3 mA head forward, 0.3 mA head forward and the 3 mA head forward split electrode conditions. The horizontal dashed lines represent the 95% confidence interval. Significance levels were only reached in the 3 mA head forward condition. HF, head forward; Split, split electrode condition with electrodes on the forehead and on the spinous process of C7; SOL, soleus; mGAS, medial head of gastrocnemius; lGAS, lateral head of gastrocnemius; l: left; r: right.

For the 3 mA HF bilateral binaural condition, the biphasic response observed in the cumulant density estimate exhibited the same polarity as that elicited during the anode right 3 mA square-wave pulses (Fig. 3). The cumulant density estimate appeared as a low-pass filtered version of the responses generated by the square-wave GVS pulses. The left leg's muscles cumulant density estimate had an initial negative peak followed by a positive-going peak whereas the right leg's muscles displayed an inverted biphasic response (positive peak followed by a negative peak). On average, the onset of the biphasic response measured from the cumulant density estimate was 47 ± 2 ms and the onset of the second peak was 82 ± 3 ms while the onset of the responses elicited by the square-wave GVS pulses occurred ∼10–15 ms later (57 ± 1 and 96 ± 4 ms). The peaks of the SVS-evoked muscle responses occurred approximately 20 ms earlier in the cumulant density estimates compared with the responses elicited by the square-wave GVS pulses (66 ± 1 versus 85 ± 7 ms and 104 ± 6 versus 128 ± 7 ms).

Figure 3.

Pooled comparison of cumulant density estimates to the EMG responses evoked by square-wave GVS pulses A, pooled (n = 10) cumulant density estimates for each of the six muscle groups derived from the SVS in the head forward condition. The vertical dashed line indicates zero lag mark between the SVS and muscle activity. B, pooled (n = 10) spike trigger averaged EMG corresponding to the square-wave pulse trials with participants head's forward. The vertical dashed line indicates the onset of the square-wave GVS pulse. SOL, soleus; mGAS, medial head of gastrocnemius; lGAS, lateral head of gastrocnemius; l: left; r: right.

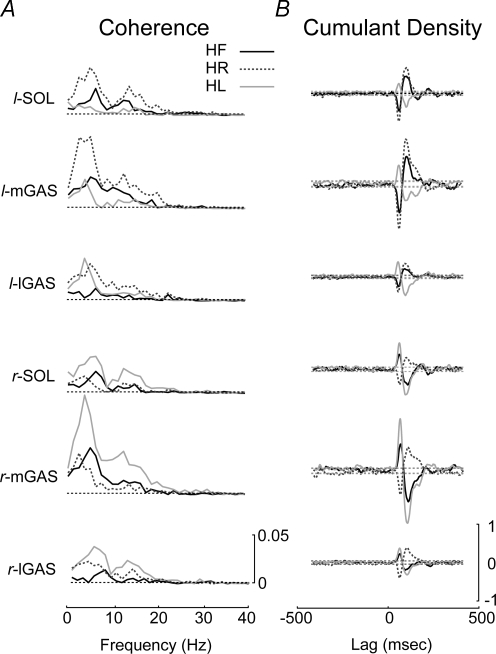

Bilateral comparison of the response polarity observed in the cumulant density estimate revealed inverted responses in the HF condition but matching response polarity for the HL and HR conditions (Fig. 4). For the 3 mA HL condition, the bilateral muscles exhibited biphasic responses with an initial positive peak followed by a negative peak. The biphasic muscle response polarity reversed bilaterally in the HR condition. In the frequency domain, the DoC test revealed significant differences in the coherence estimates between the three head conditions for all muscles (Fig. 5). Pair-wise DoC tests showed increased coherence values in the limb opposite the head turn, i.e. the coherence estimates were larger in the left leg muscles when the participants turned their head to the right (Fig. 5C). These changes in coherence were reflected in the time-cumulant estimates (Fig. 4). While significant differences were found between all pairings, the magnitude of the DoC test was largest for the medial head of the gastrocnemius and smallest for the lateral head of the gastrocnemius, particularly in the HR versus HL comparison.

Figure 4.

Coherence and cumulant density estimates for the different head positions A, pooled (n = 10) coherence plots between the SVS and the muscle activity for the head forward, head right and head left conditions. Significant coherence was observed in all muscles for the three head positions. Coherence was larger in the limb opposite to the head turn (right leg when the head is turned to the left). The horizontal dashed lines represent the 95% confidence limit. B, pooled (n = 10) cumulant density estimate showing the presence of a biphasic response reversing in polarity between the head right and head left conditions. The dashed line represents the 95% confidence interval. HR, head right; HL, head left; SOL, soleus; mGAS, medial head of gastrocnemius; lGAS, lateral head of gastrocnemius; l: left; r: right.

Figure 5.

Comparison of different head positions A, superimposed pooled (n = 10) coherence plots for each of the head position conditions for each of the six muscle groups. The largest SVS–EMG coherence was seen in the medial gastrocnemius of the limb opposite to the head turn. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence limit. B, difference of coherence test for all three head positions and all six muscles displaying significant differences in coherence between the three head positions. Horizontal segmented lines represents the significance level for the χ2 distribution (P = 0.05). C, difference of coherence test between each pair of head positions across all six muscle groups. The horizontal segmented lines represents the significance level for the χ2 distribution (P = 0.05). The medial head of the gastrocnemius showed the largest coherence changes across different head positions. HF, head forward; HR, head right; HL, head left; DoC, difference of coherence test; SOL, soleus; mGAS, medial head of gastrocnemius; lGAS, lateral head of gastrocnemius; l: left; r: right.

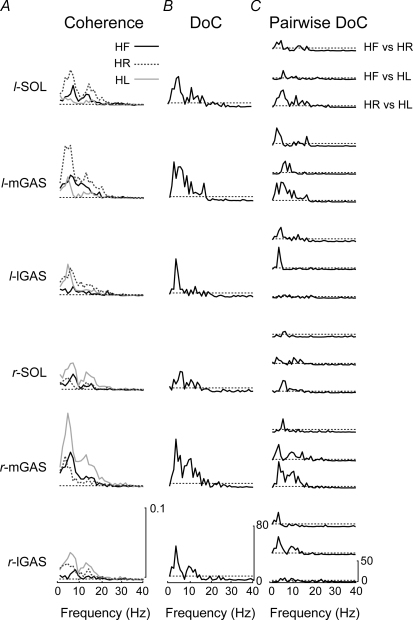

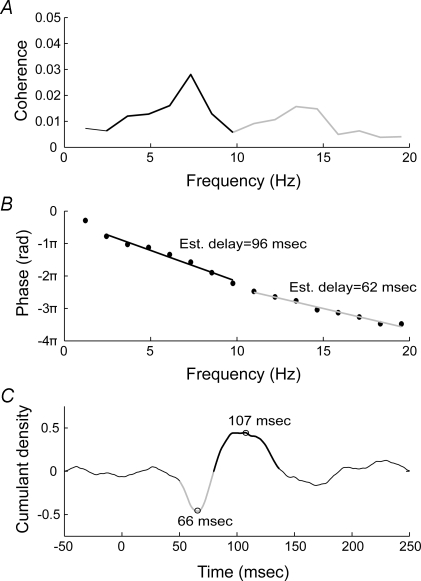

The slope of the phase estimates between the SVS and the muscle EMG was computed in order to determine the link between the coherent frequencies and the peaks observed in the cumulant density functions (Fig. 6). The slopes were computed for two regions exhibiting localized coherence peaks (2–10 Hz and 11–20 Hz) for all head conditions (Table 1). When averaged across all conditions and muscles, the slope of the phase estimates calculated for the higher frequency bandwidth revealed a 76 ± 7 ms delay. This delay corresponded to the first peak described in the time cumulant estimates (on average 65 ± 1 ms). On the other hand, the slope of the phase estimates calculated for the lower frequency bandwidth revealed a 96 ± 5 ms delay (averaged across all conditions and muscles) which corresponded to the second peak observed in the time cumulant estimate (on average 105 ± 4 ms).

Figure 6.

Relationship between coherence, phase estimation and cumulant density for the left soleus A, pooled coherence (n = 10) for the head forward condition in the left soleus. Coherence estimate displays two peaks, the first between 2 and 10 Hz and the second between 11 and 20 Hz. B, phase estimates between the SVS and the muscle activity at various frequencies. Typically, phase estimates cycle between −π and π; here the phase estimates have been reset to display the points corresponding to the frequency bandwidths of interest on a continuous slope. Linear regression was used to compute a slope for the phase points corresponding to the regions of interest in the coherence estimate. The slope of the phase points provide the lag of the EMG signal with respect to the SVS signal for a particular frequency bandwidth. C, the peaks in the biphasic cumulant density estimate correspond to the lags estimated for the slope of the phase between the SVS and muscle signals. The early component of the biphasic cumulant density function is associated with the high-frequency bandwidth of the coherence plot (11–20 Hz) and second peak in the cumulant density function is associated with the low-frequency bandwidth (2–10 Hz).

Table 1.

Comparison of delays calculated from the phase estimates with the corresponding delays of peaks obtained from the cumulant density functions

| A. Delays (ms) estimated from the phase estimates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | HL | HR | ||||

| 11–20 Hz | 2–10 Hz | 11–20 Hz | 2–10 Hz | 11–20 Hz | 2–10 Hz | |

| l-SOL | 62 | 96 | 94 | 106 | 71 | 98 |

| l-mGAS | 79 | 93 | 83 | 102 | 80 | 100 |

| l-lGAS | 70 | 89 | 77 | 99 | 73 | 91 |

| r-SOL | 69 | 98 | 75 | 104 | 73 | 92 |

| r-mGAS | 83 | 101 | 79 | 97 | 76 | 97 |

| r-lGAS | 79 | 83 | 82 | 94 | 70 | 96 |

| B. Delays (ms) of the peak values of the cumulant density functions | ||||||

| HF | HL | HR | ||||

| SL | ML | SL | ML | SL | ML | |

| l-SOL | 66 | 107 | 64 | 106 | 64 | 106 |

| l-mGAS | 67 | 105 | 64 | 110 | 66 | 105 |

| l-lGAS | 66 | 99 | 63 | 103 | 63 | 99 |

| r-SOL | 63 | 110 | 64 | 102 | 65 | 102 |

| r-mGAS | 66 | 109 | 64 | 105 | 66 | 110 |

| r-lGAS | 65 | 96 | 63 | 106 | 63 | 107 |

A, time delays computed from the slope of the phase estimates for the low (2–10 Hz) and high (11–20 Hz) frequency components of the significant coherence. These time delays were calculated for each muscle using the group mean data (N = 10). B, estimated time delay of the peak magnitudes for the short and medium latency myogenic responses obtained from the cumulant density functions for each muscle (group mean, N = 10). SOL, Soleus; mGAS, medial head of gastrocnemius; lGAS, lateral head of gastrocnemius; l, left; r, right.; HF, head forward; HL, head left; HR, head right; SL, short latency; ML, medium latency.

Discussion

The aim of the current experiment was to determine if lower limb muscle responses could be elicited by SVS in standing subjects. Our results revealed significant coherence and cumulant density functions between SVS and muscle activity in the lower limbs. These resulting SVS–EMG coherence and time cumulant functions were modulated by current amplitude, electrode position and head orientation with respect to the subject's feet. In addition, specific frequency bandwidths in the stochastic vestibular signal contributed to the early and late components of the SVS-evoked muscular responses. These findings strongly support our initial hypothesis that SVS evokes muscular responses in lower limb muscles.

Vestibular origin of the muscular responses

The presence of the SVS-evoked muscular responses was observed for all binaural bipolar conditions in which the current amplitude was 3 mA. We did not observe significant coherence between SVS and lower limb EMGs with a current amplitude of 0.3 mA or when the electrodes were positioned on the forehead and C7 (current amplitude 3 mA). GVS-evoked muscle responses are modified with current amplitude and previous researchers have suggested that 2–2.5 mA pulses are sufficient to reliably elicit these myogenic responses (Fitzpatrick et al. 1994; Ali et al. 2003). The absence of muscular responses to 3 mA stochastic currents applied to the forehead and C7 argues for the specificity of the observed correlation between the SVS and muscle signals. It can be ruled out that our observations resulted from random processes occurring in the SVS signals and the EMG activity in the lower limbs. More importantly, this observation demonstrates that SVS–lower limb EMG coherence occurs as a consequence of modulation of the firing frequency of vestibular afferents and not as a result of a non-specific cutaneous reflex.

Estimation of the time cumulant function between SVS and lower limb EMG yielded biphasic muscular responses. These muscular responses exhibited the same polarity as the EMG responses elicited by short duration square-wave GVS pulses (anode right configuration) and approximated the short and medium latencies of the GVS-evoked responses. Manipulation of participant's head position relative to their feet produced polarity changes in the stochastically induced EMG responses similar to those previously reported (Iles & Pisini, 1992; Britton et al. 1993) using more traditional square-wave GVS pulses. The polarity of the short and medium latency responses reversed as the participants turned their head from 90 deg to the right to 90 deg to the left. This correspondence between the myogenic responses elicited by stochastic and square-wave vestibular stimulations further supports the vestibular origin of the muscular reflexes elicited by the SVS signal.

The only notable difference between the muscular responses elicited by SVS and square-wave GVS pulses was the shorter onset latency of the reflexes using the former technique (by ∼10–15 ms). This difference cannot be attributed to muscular activation as larger activity in the target muscles increases reflex amplitude but does not modify onset latency. This apparent discrepancy could be explained by the minimal square-wave duration (∼10–25 ms) required to elicit a muscular response (Britton et al. 1993). SVS, on the other hand, may alter continuously the firing rate of primary vestibular afferents at various frequencies thus by-passing the possible delay induced by square-wave GVS pulses. This raises the possibility that SVS may be a better protocol to determine the onset of the vestibular-evoked muscle responses in humans.

Frequency content of the SVS-evoked muscular responses

Two distinct regions of coherence between the SVS signal and the EMG of the lower limb musculature were identified in this study: 2–10 Hz and 11–20 Hz. The corresponding cumulant density estimate indicated a biphasic EMG response to the SVS signal with distinct peaks at approximately 65 ± 1 and 105 ± 4 ms. Calculation of the slope of the SVS/EMG phase estimates in the identified regions of significant coherence, showed that the biphasic reflex was an amalgamation of two input signals. The higher frequency coherence (11–20 Hz) contributed to the short latency component of the vestibulo-myogenic reflex (76 ± 7 ms) whereas the lower frequency coherence (2–10 Hz) contributed to the medium latency component of the reflex (96 ± 5 ms). The short latency response had a smaller period than the medium latency response and therefore was composed of higher frequency signal than the medium latency response. Indirect support for this observation was the reduced short latency responses (but not medium latency) observed when ramped galvanic stimuli have slow rates of increase (Rosengren & Colebatch, 2002).

The frequency content of each deflection of the biphasic muscle response may indicate the neural origin of these deflections. Researchers have suggested that vestibular input to lower limb muscles may travel through two separate spinal pathways (Britton et al. 1993). These authors postulated that the first EMG response to GVS perturbations is transmitted through reticulospinal tracts whereas the second response travels through vestibulospinal pathways. Recently, Grosse & Brown (2003) argued that muscular oscillations in the 10–20 Hz bandwidth could be used as a surrogate marker of reticulospinal drive. The correspondence between the 11–20 Hz coherence and the first muscle deflection observed here provides additional support for the reticulospinal origin of the early GVS/SVS-evoked muscular response (short latency). The potential frequency characteristics of vestibulospinal drive have not been formally identified. Fitzpatrick et al. (1994), however, have observed reciprocal activity in the soleus and tibialis anterior at a 6–7 Hz frequency in participants stimulated with 6 mA differential galvanic vestibular stimuli. These 6–7 Hz oscillations correspond to the 2–10 Hz frequencies constituting the second muscular response to the SVS that has been hypothesized to be conveyed through vestibulospinal tracts. An extended hypothesis for the different frequency content of the biphasic muscle response may stem from recent work by Cathers et al. (2005). These authors observed independent modulation of the medium latency component of the biphasic muscle response by modifying head pitch position due to a separation of the otolith- and canal-mediated responses. They proposed otolith afferents trigger the short latency responses through the reticulo-spinal pathway whereas semicircular canal afferents trigger the medium latency responses through the vestibulo-spinal pathway. Together with the current observations, it can be hypothesized that high-frequency currents preferentially activate otolithic afferents which generate the short latency response through reticulo-spinal pathways. The medium latency response could be triggered by low-frequency currents activating preferentially semicircular canal afferents and vestibulo-spinal pathways. Although the proposed frequency–reflex components relationship is supported by previous research, further work is necessary to validate the proposal that specific pathways convey the two sources of coherent input on the lower limb musculature.

Advantages and limitations of stochastic vestibular stimulation

In addition to producing results similar to those achieved using square-wave GVS, a stochastic signal has many benefits over traditional square-wave GVS stimuli. First, the duration of stimulation required to produce similar SVS-evoked muscle responses was 2 min shorter for the stochastic signal compared with the square-wave pulses. This may be due to the continuous nature of the SVS signal in opposition to the varying quiescent inter-stimulus interval associated with the square-wave GVS pulses. While a stochastic signal may require less stimulus duration than a square-wave signal to produce interpretable results it is important to note that sufficient stimulus length (approximately 3 min) is required to achieve a representative coherence estimate. Second, SVS provides frequency relationships between the stimulation signal and the muscular responses through coherence estimates. This important feature may lead to the development of new stimulation protocols targeting specific components of the muscle or posture response. In addition, the coherence framework associated with the analysis of SVS has inherent advantages. Coherence estimates are self-normalized by the power of the SVS and muscle signals, effectively normalizing the coherence estimate for the magnitude of the EMG signal. This allows inter- and intra-subject coherence calculation and comparison without potential bias induced by changes in EMG activity amplitude. This intrinsic EMG normalization could prove very useful when comparing the SVS-evoked muscles responses between healthy individuals and various patient populations. Confidence intervals for the coherence estimates can be computed on a subject-by-subject basis and different conditions can be readily compared using a simple DoC test. Finally, verbal report of the cutaneous sensation resulting from the SVS indicate that while the stochastic signal was perceived as ‘weird’, it was generally more comfortable and less irritating or nauseating than the square-wave GVS signal.

While a stochastic vestibular stimulus has benefits, the relatively weak coherence estimates (5–10%) observed here may provide their own inherent difficulties. The combined weakness and wide bandwidths of significant SVS–EMG coherence observed here may confound identification of the specific oscillatory content of vestibulo-motor responses and in consequence the calculation of phase estimates and lags of the cumulant density functions.

In summary, the results of the current experiment showed that SVS elicits muscle responses in the lower limbs of standing subjects. The responses observed following SVS behaved similarly to those elicited by square-wave pulses, arguing for their vestibular origin. The different frequency content of the early and late components of the SVS-evoked muscle responses provides additional support for the involvement of two separate physiological processes in the generation of these responses. The present work demonstrates that SVS is a viable option when probing the vestibular system and lays a rigid framework to study the SVS-evoked muscle responses in healthy individuals and patient populations.

Acknowledgments

The current study was funded by the National Sciences & Engineering Research Council (NSERC) (J.T.I. and C.J.D.) and Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation & Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CCRF-CIHR) (J.-S.B.).

References

- Ali AS, Rowen KA, Iles JF. Vestibular actions on back and lower limb muscles during postural tasks in man. J Physiol. 2003;546:615–624. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amjad AM, Halliday DM, Rosenberg JR, Conway BA. An extended difference of coherence test for comparing and combining several independent coherence estimates: Theory and application to the study of motor units and physiological tremor. J Neurosci Meth. 1997;73:69–79. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(96)02214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin JS, Inglis JT, Siegmund GP. Startle responses elicited by whiplash perturbations. J Physiol. 2006;573:857–867. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brillinger DR. Cross-spectral analysis of processes with stationary increments including the stationary. Ann Probability. 1974;2:815–827. [Google Scholar]

- Britton TC, Day BL, Brown P, Rothwell JC, Thompson PD, Marsden CD. Postural electromyographic responses in the arm and leg following galvanic vestibular stimulation in man. Exp Brain Res. 1993;94:143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00230477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathers I, Day BL, Fitzpatrick RC. Otolith and canal reflexes in human standing. J Physiol. 2005;563:229–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauquil AS, Day BL. Galvanic vestibular stimulation modulates voluntary movement of the human upper body. J Physiol. 1998;513:611–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.611bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coats AC. The variability of the galvanic body-sway test. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1973;82:333–339. doi: 10.1177/000348947308200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day BL, Severac Cauquil A, Bartolomei L, Pastor MA, Lyon IN. Human body-segment tilts induced by galvanic stimulation: a vestibulary driven balance protection mechanism. J Physiol. 1997;500:661–672. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R, Burke D, Gandevia SC. Task-dependent reflex responses and movement illusions evoked by galvanic vestibular stimulation in standing humans. J Physiol. 1994;478:363–372. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick R, Burke D, Gandevia SC. Loop gain of reflexes controlling human standing measured with the use of postural and vestibular disturbances. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3994–4008. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick RC, Day BL. Probing the human vestibular system with galvanic stimulation. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:2301–2316. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00008.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JM. Afferent diversity and the organization of central vestibular pathways. Exp Brain Res. 2000;130:277–297. doi: 10.1007/s002210050033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JM, Smith CE, Fernandez C. Relation between discharge regularity and responses to externally applied galvanic currents in vestibular nerve afferents of the squirrel monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1984;51:1236–1256. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.6.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse P, Brown P. Acoustic startle evokes bilaterally synchronous oscillatory EMG activity in the healthy human. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:1654–1661. doi: 10.1152/jn.00125.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday DM, Conway BA, Farmer SF, Shahani U, Russell AJ, Rosenberg JR. Coherence between low-frequency activation of the motor cortex and tremor in patients with essential tremor. Lancet. 2000;355:1149–1153. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday DM, Rosenberg JR, Amjad AM, Breeze P, Conway BA, Farmer SF. A framework for the analysis of mixed time series/point process data – theory and application to the study of physiological tremor, single motor unit discharges and electromyograms. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1995;64:237–278. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(96)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iles JF, Pisini JV. Vestibular-evoked postural reactions in man and modulation of transmission in spinal reflex pathways. J Physiol. 1992;455:407–424. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilner JM, Baker SN, Salenius S, Hari R, Lemon RN. Human cortical muscle coherence is directly related to specific motor parameters. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8838–8845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08838.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Son GM, Blouin JS, Inglis JT. Assessing the modulations in vestibulospinal sensitivity during quiet standing using galvanic vestibular stimulation. Abstr Soc Neurosci. 2005;168:17. [Google Scholar]

- Lund S, Broberg C. Effects of different head positions on postural sway in man induced by a reprodutible vestibular error signal. Acta Physiol Scand. 1983;117:307–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1983.tb07212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDougall HG, Moore ST, Curthoys IS, Black FO. Modeling postural instability with galvanic vestibular stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 2006;172:208–220. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0329-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore ST, Macdougall HG, Peters BT, Bloomberg JJ, Curthoys IS, Cohen HS. Modeling locomotor dysfunction following spaceflight with galvanic vestibular stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 2006;174:647–659. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0528-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM, Wolfson P. Influence of head position and proprioceptive cues on short latency postural reflexes evoked by galvanic stimulation of the human labyrinth. Brain Res. 1974;67:255–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik AE, Inglis JT, Lauk M, Oddsson L, Collins JJ. The effects of stochastic galvanic vestibular stimulation on human postural sway. Exp Brain Res. 1999;124:273–280. doi: 10.1007/s002210050623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg JR, Amjad AM, Breeze P, Brillinger DR, Halliday DM. The fourier approach to the identification of functional coupling between neuronal spike trains. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1989;53:1–31. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(89)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengren SM, Colebatch JG. Differential effect of current rise time on short and medium latency vestibulospinal reflexes. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scinicariello AP, Eaton K, Inglis JT, Collins JJ. Enhancing human balance control with galvanic vestibular stimulation. Biol Cybern. 2001;84:475–480. doi: 10.1007/PL00007991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staude GH. Precise onset detection of human motor responses using a whitening filter and the log-likelihood ratio test. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2001;48:1292–1305. doi: 10.1109/10.959325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staude G, Wolf W. Objective motor response onset detection in surface myoelectric signals. Med Eng Phys. 1999;21:449–467. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(99)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardman DL, Taylor JL, Fitzpatrick RC. Effects of galvanic vestibular stimulation on human posture and perception while standing. J Physiol. 2003;551:1033–1042. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.045971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson SR, Colebatch JG. Vestibular-evoked electromyographic responses in soleus: a comparison between click and galvanic stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 1998;119:504–510. doi: 10.1007/s002210050366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welgampola MS, Colebatch JG. Vestibulospinal reflexes: Quantitative effects of sensory feedback and postural task. Exp Brain Res. 2001;139:345–353. doi: 10.1007/s002210100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welgampola MS, Day BL. Craniocentric body-sway responses to 500 Hz bone-conducted tones in man. J Physiol. 2006;577:81–95. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]