Abstract

The temporal properties of limb motoneuron bursting underlying quadrupedal locomotion were investigated in isolated spinal cord preparations (without or with brainstem attached) taken from 0 to 4-day-old rats. When activated either with differing combinations of N-methyl-d,l-aspartate, serotonin and dopamine, or by electrical stimulation of the brainstem, the spinal cord generated episodes of fictive locomotion with a constant phase relationship between cervical and lumbar ventral root bursts. Alternation occurred between ipsi- and contra-lateral flexor and extensor motor root bursts, and the cervical and lumbar locomotor networks were always active in a diagonal coordination pattern that corresponded to fictive walking. However, unlike typical locomotion in adult animals in which extensor motoneuron bursts vary more with cycle period than flexor bursts, in the isolated neonatal cord, an increase in fictive locomotor speed was associated with a decrease in the durations of both extensor and flexor bursts, at cervical and lumbar levels. To determine whether this symmetry in flexor/extensor phase durations derived from the absence of sensory feedback that is normally provided from the limbs during intact animal locomotion, EMG recordings were made from hindlimb-attached spinal cords during drug-induced locomotor-like movements. Under these conditions, the duration of extensor muscle bursts increased with cycle period, while flexor burst durations now tended to remain constant. Moreover, after a complete dorsal rhizotomy, this extensor dominant pattern was replaced by flexor and extensor muscle bursts of similar duration. In vivo and in vitro experiments were also conducted on older postnatal (P10–12) rats at an age when body-supported adult-like locomotion occurs. Here again, characteristic extensor-dominated burst patterns observed during intact treadmill locomotion were replaced by symmetrical patterns during fictive locomotion expressed by the chemically activated isolated spinal cord, further indicating that sensory inputs are normally responsible for imposing extensor biasing on otherwise symmetrically alternating extensor/flexor oscillators.

Mammalian locomotion is generated by localized neuronal circuits or central pattern generators (CPGs) within the spinal cord which interact to produce coordinated movements of the different limbs and body regions. The locomotor CPGs of quadruped mammals consist of half-centre modules located in the cervical and lumbar regions of the spinal cord, with each module being responsible for alternate rhythmic contractions of antagonistic flexor and extensor muscle groups in the corresponding forelimb or hindlimb (Grillner, 1981). In recent years, considerable progress in understanding the neuronal organization and operation of mammalian locomotor CPG networks has been made using the isolated spinal cord of the newborn rat (Kiehn & Butt, 2003), since this in vitro preparation can produce rhythmic motor output patterns similar to those underlying locomotion in the intact adult (Smith & Feldman, 1987; Cazalets et al. 1992; Cowley & Schmidt, 1994; Kiehn & Kjaerulff, 1996). Such in vitro locomotor-related activity, which can be elicited by neurochemical (op. cit.) or brainstem electrical stimulation (Atsuta et al. 1988; Zaporozhets et al. 2004), thus corresponds to the alternate activation of homologous (left–right) limb muscles of the same (cervical or lumbar) girdle as well as of antagonistic flexor and extensor muscles in each limb. To date, the neonatal rat spinal cord model has been mostly used to investigate the neuronal correlates of lumbar CPG activity responsible for rhythmic hindlimb movements. More recently, attention has also become focused on the spinal mechanisms that are necessary to couple the cervical and lumbar CPG networks to produce coordinated quadrupedal locomotion (Ballion et al. 2001; Juvin et al. 2005).

During overground locomotion in adult animal species, including cats (Goslow et al. 1973; Halbertsma, 1983), rats (Slawinska et al. 2000; Navarrete et al. 2002) and humans (Grillner et al. 1979), changes in stepping rate typically result from a change in the duration of the extensor (stance) phase of a limb movement cycle, whereas the flexor (swing) phase duration remains relatively constant (reviewed by Orlovsky et al. 1999). Thus the duration of extensor-related activity is usually strongly correlated with the locomotor cycle period, whereas flexor activity is not. Consequently, the portion of each cycle occupied by extensor activity tends towards constancy, whereas flexor activity has a consistently shorter duration and occupies a smaller fraction of each cycle as periods become longer.

In principle, the physiological basis for this extensor phase ‘dominance’ or ‘biasing’ during stepping in the freely behaving animal could derive from one (or a combination) of three different sources: (1) the extensor/flexor asymmetry is an inbuilt property of the spinal rhythm-generating circuitry itself (Dubuc et al. 1988; Grillner & Dubuc, 1988), (2) the extensor biasing in locomotor network activity is conferred by descending influences from the brainstem (Leblond & Gossard, 1997; Armstrong, 1988), or (3) phasic sensory inputs arising from actual limb movements are able differentially to prolong the extensor phase of otherwise simple alternating CPG half-centres (Engberg & Lundberg, 1969; Barbeau & Rossignol, 1987; McCrea, 2001; Rossignol et al. 2006). However, despite considerable literature on the subject, consistent direct evidence for (or against) any of these possibilities is surprisingly still lacking, possibly in large part due to the necessity to perform the appropriate adult animal experiments in vivo, and under differing conditions of decerebration and deafferentation.

By initially using combined cervical and lumbar ventral root recordings from isolated in vitro preparations of the neonatal (postnatal day (P)0–4) rat spinal cord, we show here that in contrast to the intact adult, the durations of both extensor and flexor motor root bursts at the two cord levels vary similarly with cycle period during both neurochemically and electrically evoked fictive locomotion. Despite several fold changes in cycle period, the locomotor CPGs in the isolated cord generated a solitary coordination pattern that resembled quadrupedal walking. Chemically evoked fictive locomotion with equal flexor/extensor phase durations was also expressed by isolated spinal cords from juvenile rats at P10–12, when body-supported walking occurs. However, semi-intact P0–4 preparations with attached hindlimbs, as well as older intact P10–12 animals, displayed the characteristic adult-like, extensor-dominated pattern during chemically activated locomotion and treadmill walking, respectively. This indicates therefore that the extensor biasing in vivo does indeed derive from movement-activated sensory inputs to the locomotor CPGs which then revert to simple half-centre oscillators after these extrinsic influences are removed. Part of this work has been presented previously in abstract form (Juvin et al. 2006).

Methods

Dissection and in vitro preparation

Experiments were conducted on two age groups (0–4 and 10–12 days old) of Wistar rats that were anaesthetized by hypothermia and rapidly killed and eviscerated. The skin, muscles and bones were removed, and the preparation was then placed in a 25 ml chamber filled with circulating (flow rate 5–10 ml min−1) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; see composition below) maintained at 10°C throughout the dissection. The entire spinal cord was isolated with its ventral roots still attached to allow subsequent extracellular recordings (see below). In some experiments on P0–4 animals, one side of the spinal cord and its ventral roots were exposed, while the ventral roots of the other side were kept intact. The branch of the deep peroneal nerve to the tibialis anterior (ankle flexor muscle) and the gastrocnemius (ankle extensor) nerve were then located and sectioned peripherally at the muscle level to allow locomotor activity to be recorded from their central cut ends. All preparations were placed in a 10 ml recording chamber and superfused continuously (flow rate 3–5 ml min−1) with an ACSF warmed to 25°C, equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2 (pH 7.4) and containing (mm): 113 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 NaHCO3 and 11 d-glucose. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the local ethics committee of the University of Bordeaux 2 and the European Communities Council Directive.

Ventral root recordings and induction of locomotor activity

Electrical activity in selected spinal ventral roots was recorded using glass suction electrodes or Vaseline-insulated, stainless-steel pin electrodes. Signals were amplified (×10 000) by home-made AC amplifiers, bandpass-filtered (0.1–1 kHz), full-wave rectified, integrated (τ= 20 ms), digitized and stored on a computer hard disk (using Spike2 software from Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) for off-line analysis.

In most experiments, rhythmic locomotor-related activity was pharmacologically induced in isolated spinal cords, beginning 2 h after dissection. Drugs were bath-applied by gravity supply, and unless otherwise specified, consisted of a mixture of N-methyl-d,l-aspartate (NMA; 5–20 μm), serotonin (5HT; 10 μm) and dopamine (DA; 100 μm) (all purchased from Sigma, France).

In a further series of experiments, the brainstem was left attached to the spinal cord in order to stimulate descending spinal pathways without pharmacological activation of spinal locomotor circuitry. The experimental procedure used to stimulate bulbospinal projections capable of inducing locomotor-like activity has been previously described in detail (Zaporozhets et al. 2004). Briefly, a stimulating silver wire electrode inserted into a glass capillary was manipulator positioned in contact with the medio-ventral surface of the brainstem. Stable, well-organized episodes of fictive locomotion were then elicited by applying stimulus pulse trains (range 2–5 V, 10–20 ms duration at 2 Hz) through the electrode with a digital stimulator (API, Jerusalem, Israel).

EMG recordings and semi-isolated preparations

In a further set of experiments (n = 5), an in vitro preparation of the spinal cord with both intact hindlimbs still attached was employed in which EMG recordings were used to monitor lumbar network activity during the occurrence of actual limb movement (Kudo & Yamada, 1987). The spinal cord was exposed as described above with all ventral and dorsal roots left uncut. A thoracic transection (T7) was then made to remove any descending influences either via supra-spinal pathways or from the cervical locomotor-rhythm generators. The preparation was then pinned down ventral side upwards and bipolar EMG electrodes (made from 50 μm silver wire) were then inserted into the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles of one hindlimb, and locomotor activity was pharmacologically induced by a mixture of NMA, 5HT and DA added to the bathing saline.

Treadmill locomotion

To monitor actual locomotor activity in vivo, older (P10–12) rats were anaesthetized by hypothermia until the loss of reflex responsiveness to tail pinching. Bipolar electrodes for EMG were inserted into the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles of a hindlimb and secured externally to the skin by means of tissue glue (collodion; Sigma). Animals were warmed and the temperature of the EMG recording set-up was maintained at ∼30°C by means of spotlights.

Limb muscle activity was recorded during stable episodes (≥10 cycles) of locomotion by rats placed on a low-speed motorized treadmill enclosed in a Plexiglass chamber. Rather than imposing different locomotor speeds, the treadmill was used to maintain stationary body-position stepping by manually adjusting the belt velocity with a variable-speed controller to match belt speed to the spontaneous stepping of the animal.

Data analysis

To evaluate the relationships between the durations of flexor and extensor motor activity and cycle period during fictive, in vitro stepping and real locomotion, the mean durations of individual ventral root bursts or activity of a given muscle were measured from the raw electroneurogram (ENG) or EMG signals, and were then plotted against the corresponding locomotor cycle period (Fig. 1A, right). Cycle period was defined as the interval between the onsets of consecutive bursts in either the corresponding flexor- or extensor-related recordings (note that antagonistic burst pairs could have slightly different period values due to variability in burst timing in the flexor and extensor halves of a given cycle). Unless otherwise stated, burst and cycle duration means were calculated from either ≥20 randomly selected cycles or ≥10 consecutive cycles occurring during a recorded locomotor sequence in a given in vitro preparation (ENG) or animal (EMG), respectively. Linear regression lines were then fitted to the scatterplots and the regression line slopes (a) were determined. Coefficients of linear regression (r) were calculated and their statistical significance was established using the Pearson test. The phases of the onsets and terminations of ipsilateral ventral root discharges were determined as a fraction of the corresponding cycle that had elapsed before the start and finish, respectively, of a given burst. The relative onset, termination, and duty cycle (burst duration/cycle period) of cervical and lumbar rhythmic activity were then expressed in a percentage normalized cycle. Statistical values were given as means ±s.e.m. and differences between means were analysed using a statistical software package (SigmaStat for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and assessed by one-way ANOVA with a Student–Newman–Keuls post test. Unless otherwise specified, the level of statistical significance was set at P< 0.05.

Figure 1.

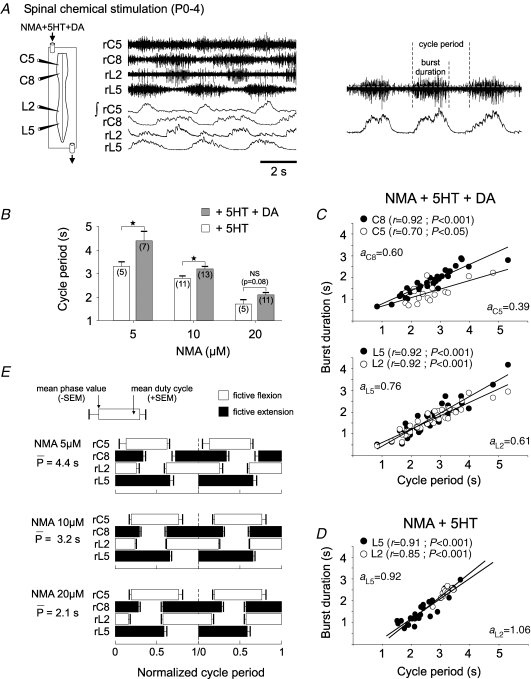

Motor pattern generation for fictive quadrupedal stepping in neonatal rat (P0–4) spinal cord A, left, schematic of isolated spinal cord with extracellular recording locations from right (r) cervical (flexor, C5; extensor, C8) and lumbar (flexor, L2; extensor, L5) ventral roots; right, raw extracellular and corresponding integrated (∫) activity during fictive locomotion evoked by bath-application of N-methyl-d,l-aspartate (NMA; 10 μm), serotonin (5HT; 10 μm) and dopamine (DA; 100 μm). B, relationship between cycle period of chemically induced rhythmicity and the concentration (5, 10 or 20 μm) of NMA used with 5HT alone (open bars), or with 5HT + DA (shaded bars). Vertical lines indicate s.e.m. and numbers of measured preparations for each condition are indicated in parentheses. *P< 0.05; NS, difference not significant. C, scatter plots showing the relationship between homolateral lumbar (lower) and cervical (upper) burst durations and rhythm cycle period. Data were pooled from 13 preparations. Each point represents the mean burst duration for at least 20 cycles of the same duration from a single preparation. A given preparation can be represented by up to three points. Both flexor (L2, C5; ○) and extensor (L5, C8; •) burst durations were positively correlated with cycle period. D, similar dependence of lumbar flexor and extensor burst durations on cycle period in preparations activated with NMA and 5HT alone. Data were pooled from 11 preparations, with measurements made as in C. Each line in C and D is the linear regression for the corresponding pool of flexor and extensor bursts. The coefficients (r) and slopes (a) of the regression lines are indicated. E, phase diagrams showing two normalized cycles of fictive locomotion under different NMA concentrations (top, 5 μm; middle, 10 μm; bottom, 20 μm) and with 5HT and DA constant at 10 and 100 μm, respectively. Cycles were normalized to the onset of consecutive bursts of activity in the L5 ventral root. Despite differences in mean cycle period, the phase relationships in all three cases remained constant and corresponded to fictive walking.

Results

Temporal properties of chemically induced fictive locomotion

As previously reported (Barrière et al. 2004; Juvin et al. 2005), a bath-applied mixture of NMA (10 μm), 5HT (10 μm) and DA (100 μm) elicited stable bouts of fictive locomotion (mean cycle period 3.2 ± 0.1 s; 13 preparations measured) in otherwise quiescent isolated cords of 0- to 4-day-old animals (Table 1; Fig. 1A and B, middle shaded bar). The rhythmic pattern was characterized by a left/right alternation of bursts in homologous motoneurons at both cervical and lumbar levels and consistent with an interlimb coordination appropriate for quadrupedal stepping, an alternation between activity in homolateral flexor (C5 versus L2) and extensor (C8 versus L5) ventral roots (Fig. 1A).

Table 1.

Cycle periods and motor burst durations of fictive locomotion recorded simultaneously from homolateral cervical (C5, C8) and lumbar (L2, L5) ventral roots of isolated P0–4 spinal cords after bath application of three different concentrations of NMA together with 5HT and DA at constant concentrations of 10 and 100 μm, respectively

| Burst duration (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMA (μM) | n | Locomotor period (s) | C5 | C8 | L2 | L5 |

| 5 | 7 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.4 |

| 10 | 13 | 3.2 ± 0.1a | 1.4 ± 0.1a | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1a | 2.0 ± 0.1b |

| 20 | 11 | 2.1 ± 0.1a,c | 0.9 ± 0.1a,c | 1.3 ± 0.1c,d | 1.1 ± 0.1a,c | 1.1 ± 0.1a,c |

NMA, N-methyl-d,l-aspartate; 5HT, serotonin; DA, dopamine; n, number of preparations

P< 0.001 versus 5 μM NMA

P< 0.01 versus 5 μM NMA

P< 0.001 versus 10 μM NMA

P< 0.01 versus 5 μM NMA.

To assess the extent to which this typical activity pattern in the isolated spinal cords of newborn animals had acquired other basic temporal features of adult locomotion, the relationship between burst duration and cycle period (see Fig. 1A, right) during drug-evoked sequences of fictive locomotion was examined. In a first step, in order to ensure unequivocal interpretation of burst–cycle duration relationships, the range of cycle periods expressed by a given in vitro preparation was increased by bath-applying NMA at three different concentrations (5, 10 and 20 μm; Morin & Viala, 2002). Under these different NMA concentrations, but with the accompanying 5HT and DA remaining constant (at 10 and 100 μm, respectively), cycle periods varied significantly by more than twofold from a maximum mean value of 4.4 ± 0.3 s (seven preparations) with 5 μm NMA to a minimum mean of 2.1 ± 0.1 s with NMA at 20 μm (n = 11) (Table 1 and Fig. 1B, shaded bars).

As seen in Fig. 1C, where individual measurements of homolateral C5/C8 (upper) and L2/L5 (lower) root activity in the cervical and lumbar cord, respectively, were plotted against the corresponding cycle period, the durations of both flexor (C5, L2) and extensor (C8, L5) motor bursts were positively correlated with the cycle period of chemically induced fictive locomotion over the three NMA concentrations. In L2 roots (Fig. 1C, lower, open circles), burst durations ranged from means of 1.1 ± 0.1 s with 20 μm NMA (n = 11 preparations) to 2.5 ± 0.2 s with 5 μm NMA (P< 0.001; n = 7; Table 1). L5 bursts also varied significantly over the same range of NMA concentrations from 1.1 ± 0.1 to 2.7 ± 0.4 s (P< 0.01) (Fig. 1C, lower, filled circles). The coefficients of linear regression for the flexor (L2) and extensor (L5) burst/period ratios were both strongly positive and had equal values of 0.92 (P< 0.001).

As for lumbar activity, a positive correlation also occurred between burst duration and cycle period in homolateral cervical motor output (Fig. 1C, upper). Here, flexor (C5) burst durations varied over the range of NMA concentrations from 0.9 ± 0.1 to 2.1 ± 0.1 s (P< 0.001), while extensor (C8) bursts altered from 1.3 ± 0.1 to 2.3 ± 0.2 s (P< 0.01). Again the corresponding coefficients of linear regression for the cervical flexor and extensor burst-cycle duration relationships were both significantly positive with values of 0.70 (P< 0.05) and 0.92 (P< 0.001), respectively.

In a set of control experiments, the three different concentrations of NMA (5, 10 or 20 μm) were applied with 5HT (10 μm) to isolated cords in the absence of DA. Under such conditions, although the range of locomotor cycle periods was significantly reduced (Fig. 1B, open bars) and the rhythms were faster but more irregular (see also Barrière et al. 2004), both extensor and flexor burst durations at cervical and lumbar levels remained significantly correlated with the cycle period. For example, the parallel variance in L5 and L2 burst durations with cycle period in preparations under NMA and 5HT activation can be seen in Fig. 1D. These observations therefore suggest that the similar dependence of flexor and extensor burst durations on cycle period did not derive from differential influences of the two exogenous amines when acting in combination.

A fictive stepping pattern with phase-constant coordination

During locomotion in freely moving quadrupeds, shifts in speed not only result principally from changes in the stance (extensor) phase of a given limb's movement cycle, but are also accompanied by alterations in forelimb–hindlimb coordination that underlie different locomotor gaits (Orlovsky et al. 1999). To explore whether neural correlates of such changes in interlimb coordination are also expressed by locomotor circuitry in the isolated neonatal rat spinal cord, we determined the phase relationships between antagonistic cervical and lumbar ventral root bursts during chemically induced rhythmicity (Fig. 1E). This analysis allowed comparison of the relative onset, offset and duty cycle (the fraction of a cycle during which a given ventral root was active) of motor root bursts within a single normalized cycle. Moreover, to test for any alterations in phase relationships that might be related to cycle period, bursts occurring in short- (mean 2.1 s), medium- (3.2 s) and long-duration (4.4 s) cycles that occurred under the three different NMA concentrations (see Fig. 1B) were analysed separately. However, despite significant modifications in locomotor cycle period under these different neurochemical conditions, the antero-posterior phase relationships, which consisted of a symmetrical out-of-phase coordination between homolateral flexor (C5, L2) and extensor (C8, L5) motor bursts at the cervical and lumbar levels, remained unaltered in the three cycle period ranges (Fig. 1E). As expected from the similarly positive correlations of burst durations in flexor and extensor motor roots with cycle period seen in Fig. 1C, the duty cycles of bursts in each of the four roots did not change significantly (P > 0.05) over the range of cycle periods examined, with flexor and extensor bursts occupying approximately equal proportions (ca≥50%) of each cycle. Furthermore, the phases in each cycle (arbitrarily defined as the time between the start of consecutive L5 root bursts) at which burst onset and termination occurred did not change significantly or consistently with cycle period in any ventral root (Fig. 1E). These results therefore support the conclusion that the inherent coordination between the activity of cervical and lumbar CPGs in the newborn rat spinal cord is restricted to a single stereotyped pattern in which flexor and extensor motor root bursts express an out-of-phase symmetry that remains constant with varying cycle periods.

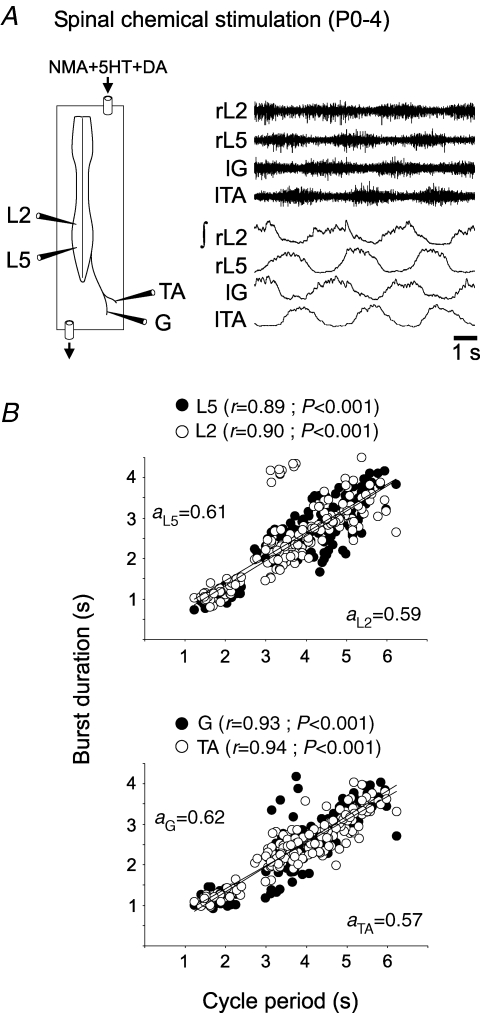

Correspondence between ventral root and muscle nerve activity

Flexor and extensor motor pools overlap within the mammalian spinal lumbar enlargement (Nicolopoulos-Stournaras & Iles, 1983) and their axons may share the same ventral root exit from the cord (Cowley & Schmidt, 1994). Thus the discharge of individual neurons within a given root population may be masked by overlapping firing in cells with different properties and functions, thereby preventing the accurate determination of single unit burst durations. To address this potential problem, additional experiments (n = 5) were performed in which identified tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius (G) nerve branches that innervate ankle flexor and extensor muscles, respectively, were dissected out until close to their muscle targets. After cord isolation, these muscle nerves were recorded simultaneously with the contralateral L2 and L5 ventral roots (Fig. 2A). Here again, under NMA, 5HT and DA, the burst durations in identified TA and G terminal nerve branches were positively correlated with locomotor cycle period (Fig. 2B, lower), and in a very similar manner to the corresponding whole-root activity recorded on the other side of the cord (Fig. 2B, upper). This finding therefore further supports the conclusion that the limb generators in the in vitro spinal cord produce alternating rhythmicity in which bursts in individual flexor/extensor motoneurons do indeed covary as a function of the fictive step cycle duration.

Figure 2.

Correspondence between locomotor-related bursting recorded from lumbar ventral roots and identified peripheral limb nerves A, experimental preparation (left) showing recording positions from right lumbar roots (rL2 and rL5), and the left tibialis anterior (lTA) and gastrocnemius (lG) nerve branches, and locomotor-related activity (raw and integrated traces at right) induced by a mixture of NMA (10 μm), 5HT (10 μm) and DA (100 μm). B, scatter plots of burst duration versus cycle period for flexor (L2) and extensor (L5) ventral root activity (upper), and flexor (TA) and extensor (G) peripheral nerve activity (lower). Note the close similarity in the relations between burst and cycle duration at the two recording levels. Data were pooled from five preparations, with each point representing the burst–cycle duration ratio for a single cycle. r and a are the coefficient and slope, respectively, of the corresponding regression line.

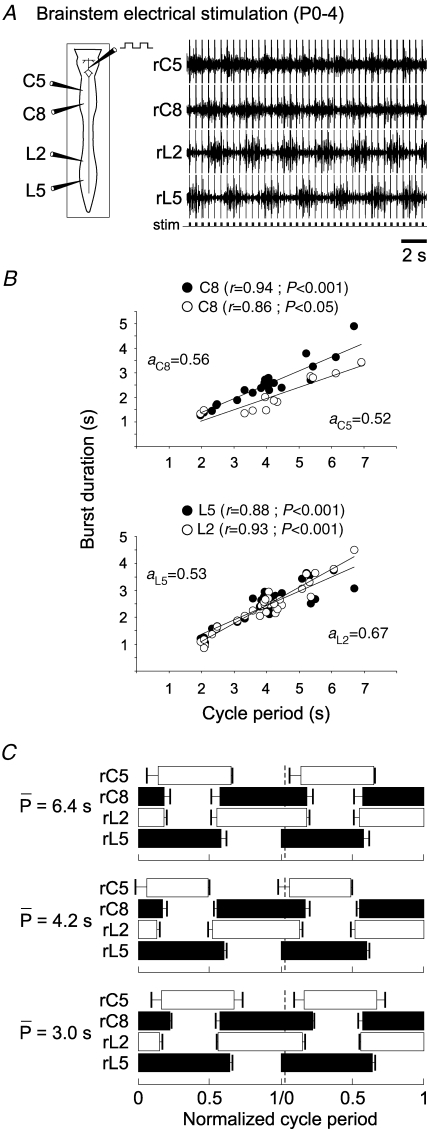

Locomotor patterns induced by brainstem electrical stimulation

Since the pioneering study of Smith & Feldman (1987), the bath-application of neuroactive substances has been widely used to induce fictive locomotor-like activity in the peri-natal rat spinal cord in vitro. However this method has the potential limitation of causing a non-specific activation of spinal neurons, some of which, although not belonging to the locomotor circuitry per se, may exert spurious effects on burst timing during drug-activated CPG rhythms. Therefore, to determine whether generalized drug exposure was somehow shaping the phase durations of motoneuron activity, we employed a more selective means to elicit fictive locomotion, namely via electrical stimulation of descending bulbospinal projections in isolated cords with the brainstem left attached (Fig. 3A). This effective method of eliciting stable locomotor rhythms in vitro (Zaporozhets et al. 2004) appears to mimic endogenous brainstem activation of spinal stepping generators, with cycle frequency varying as a function of stimulus intensity (see Methods).

Figure 3.

Brainstem electrical stimulation also induces phase-locked fictive locomotion in the isolated P0–4 spinal cord A, schematic of brainstem/spinal cord preparation (left) and extracellular recordings (right) from homolateral cervical (C5, C8) and lumbar (L2, L5) ventral roots during electrical stimulation (stim; lower trace) of the ventral surface of the brainstem. B, flexor/extensor burst durations at lumbar (lower plots) and cervical (upper plots) levels as a function of rhythm cycle period. Each point represents the mean burst duration for at least 20 cycles in a single preparation. The data set was obtained from 11 preparations, with a given preparation being represented by up to three points. r, coefficient of regression line; a, slope of regression line. C, phase diagrams showing two normalized fictive step cycles during electrically evoked fictive locomotion. Cycles were normalized to burst onset in right L5. To test for cycle period-dependent changes in phase relationships, bursts were divided into arbitrarily defined cycle period groups (means (P) of 6.4, 4.2 and 3.0 s) and their phase diagrams were constructed separately.

As previously observed during whole-cord neurochemical activation (Figs 1C and 2B), the durations of both extensor and flexor bursts recorded from homolateral lumbar (Fig. 3B, lower) and cervical (Fig. 3B, upper) ventral roots remained significantly and positively correlated to the fictive stepping period during brainstem electrical stimulation. Moreover, a statistical comparison revealed no fundamental differences between burst phase relationships in the patterns elicited by the two methods of rhythm induction (compare Figs 1E and 3C). Here again, the duty cycles of flexor and extensor motor root bursts were similar (occupying approximately 50% of each cycle), and as seen in the phase diagrams of Fig. 3C (which derived from arbitrarily chosen short-, medium- and long-duration ranges of cycle period), the relative timing within this symmetrical burst pattern did not change significantly with modifications in cycle duration.

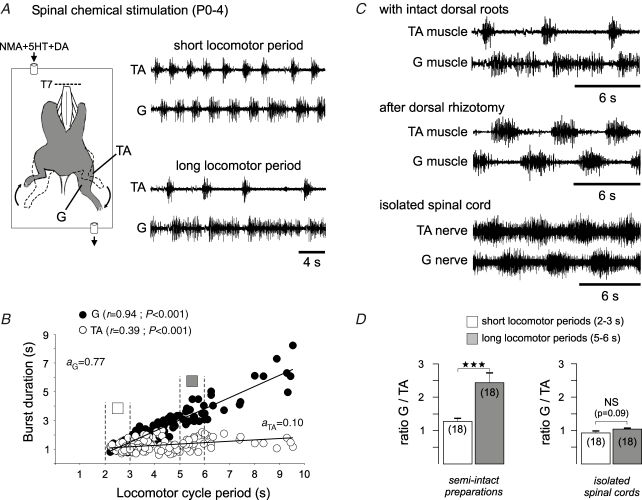

Flexor/extensor locomotor patterns in semi-isolated preparations

In a next step, we examined the extent to which the symmetrical flexor–extensor burst patterns generated by the completely isolated spinal cord might be influenced by sensory inputs resulting from actual limb movements. To address this we used hindlimb-attached preparations (n = 5) in which activity of the TA (flexor) and G (extensor) muscles was recorded during chemically induced rhythmic hindlimb movements. In these semi-isolated preparations, moreover, descending influences originating from either the brainstem or the cervical locomotor CPGs were prevented by a transection of the spinal cord at the mid-thoracic (T7) level. The bath-application of NMA, 5HT and DA to the remaining spinal cord (with intact dorsal and ventral roots; Fig. 4A, left) elicited episodes of rhythmic ‘upside-down stepping’ that consisted of clearly evident left–right alternating hindlimb movements associated with out-of-phase bursts in homolateral TA (flexor) and G (extensor) muscles (Fig. 4A, right). As is evident in these recordings, which show sequences with short (upper panel) and longer (lower panel) cycle periods, and the group analysis of Fig. 4B, variations in stepping cycle period were now extensor phase-dominated: the durations of G muscle burst activity were strongly correlated (r = 0.94) with cycle duration, while flexor TA burst durations remained relatively constant (r = 0.39). The importance of intact afferent pathways in the shaping of locomotor output is illustrated in the raw data of Fig. 4C and the analysis in Fig. 4D. As illustrated in the sample recordings from a semi-intact, non-deafferented preparation in Fig. 4C (upper traces), the durations of G and TA muscle bursts were clearly different. In the same hindlimb-attached preparation. however, this extensor dominance in the stepping pattern was replaced by flexor and extensor muscle bursts of similar duration after a complete dorsal rhizotomy (Fig. 4C, middle traces), and was similar to the symmetrical pattern that was recorded in the corresponding muscle nerves after complete spinal cord isolation (Fig. 4C, lower traces). As a consequence, the ratios between the durations of G and TA muscle bursts in hindlimb-attached preparations with intact dorsal roots were significantly different at short (arbitrarily defined as 2–3 s) and long (5–6 s) locomotor cycle periods (1.2 ± 0.1 and 2.4 ± 0.3, respectively; P< 0.001) (Fig. 4D, left). This is in direct contrast to the equivalent ratios during fictive locomotion in the completely isolated spinal cord (see Fig. 2B, bottom) where the proportions of burst durations in the motor nerves remained similar at all cycle periods (0.9 ± 0.05 and 1.0 ± 0.03; P = 0.09; Fig. 4D, right).

Figure 4.

Extensor-phase-dominated locomotor burst patterns in P0–4 semi-isolated preparations A, schematic of hindlimb-attached spinal cord preparation (left) and EMG recordings (raw traces; right) from homolateral tibialis anterior (TA) and gastrocnemius (G) muscles during chemically induced rhythmic locomotor movements (NMA, 5–20 μm; 5HT, 10 μm; DA, 100 μm). The spinal cord was sectioned at the thoracic (T7) level (dotted line). B, scatter plots showing asymmetrical relationships between the flexor (TA, ○) and extensor (G, •) burst durations and cycle period. Data were pooled from five preparations and each point represents the burst–cycle duration ratio for a single cycle period. r, coefficient of regression line; a, slope of regression line. Note that squares correspond to the data sets (between dotted lines) used to calculate D. C, G and TA muscle activities during pharmacologically induced locomotion in a hindlimb-attached preparation before (upper traces) and after a complete dorsal rhizotomy (middle traces). The symmetrical locomotor pattern observed in this deafferented semi-intact preparation was similar to that recorded from G and TA nerve branches in a different completely isolated spinal cord (lower panel). D, ratio between burst durations in the G and TA muscles (left) and in their nerves (right) for arbitrarily defined ‘short’ (open bars) and ‘long’ (shaded bars) locomotor cycle periods in semi-intact (left) and isolated spinal cord (right) preparations. Vertical lines indicate s.e.m. and the numbers of cycles used for each experimental condition are indicated in parentheses. Note that data illustrated in D were obtained from two different groups of animals (five semi-intact preparations, and five isolated spinal cords as in Fig. 2B, lower). ***P< 0.001; NS, not significant.

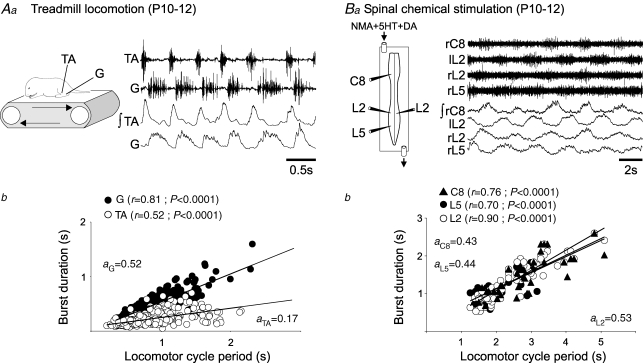

In vivo and in vitro locomotor activity in P10–12 animals

The comparison of data from isolated and semi-isolated spinal cords therefore suggested that, at least in the early postnatal animal, sensory feedback from actual limb movement does indeed play a role in shaping locomotor pattern generation so that extensor-dominated output patterns are produced. To verify that this is also the case for the locomotor systems of more mature animals, a series of in vivo (n = 5) and in vitro experiments (n = 9) was conducted on older P10–12 rats in which adult-like patterns of locomotion occur (Westerga & Gramsbergen, 1990), while their spinal cords remain viable and continue to generate locomotor rhythms under in vitro experimental conditions. First, animals (n = 5) were placed on a treadmill in order to monitor actual locomotion via EMG recordings from homolateral TA and G muscles (Fig. 5Aa). As expected under these in vivo conditions, changes in stepping cycle period were due more to variations in extensor (stance) phase duration than in flexor (swing) phase duration. This is evident in the scatterplots of Fig. 5Ab, where the significantly stronger association between extensor (G) muscle activity and step cycle duration (r = 0.81) than flexor (TA) muscle activity (r = 0.52), resulted in an asymmetrical pattern in which extensor bursts consistently occupied ≥50% of the step cycle period, whereas flexor bursts varied less and occupied <50% of each cycle.

Figure 5.

Real and fictive locomotion in 10- to 12-day-old rats Aa, treadmill locomotion of intact animal (see schematic, left) during EMG recordings from the flexor tibialis anterior (TA) and extensor gastrocnemius (G) muscles of the same hindlimb. Ba, chemically induced fictive locomotion in the isolated spinal cord as recorded from cervical (C8) and lumbar (left/right L2 and L5) ventral roots. NMA, 5HT and DA were bath-applied at 10, 10 and 100 μm, respectively. Ab and Bb, scatter plots showing relationships between the duration of flexor (○) and extensor activity (•) and real (Ab) or fictive (Bb) locomotor cycle period. In both cases, each point represents the mean burst duration for ≥10 cycles of the same duration in a single preparation. Note that the apparent lack of paired data points in each plot is due to a superposition (and masking) of identical burst duration/cycle period values. Data sets in Ab and Bb were obtained from five and three animals, respectively. r, coefficient of regression line; a, slope of regression line.

In three of nine isolated spinal cord preparations taken from a further group of P10–12 animals, bath application of a mixture of NMA, 5HT and DA at concentrations similar to those used on newborn rats was effective in generating bouts of fictive locomotion with cycle periods ranging from 1 to 5 s (note that the relatively low proportion of active preparations was due to the diminished viability of these older cords after isolation). No significant differences were found between the phase relationships of motor bursts in the three active cords (data not shown, but compare Fig. 5Ba with Fig. 1A) and bursts in the drug-induced locomotor patterns recorded in the cords of P0–4 animals. Moreover, when plotted against cycle period (Fig. 5Bb), the durations of both extensor (C8 and L5) and flexor (L2) root bursts displayed an equivalent cycle-period dependence which also resembled that observed during locomotor output in the isolated spinal cords of younger animals (compare Fig. 5Bb with Fig. 1C). Therefore, after spinal cord isolation in vitro, the locomotor oscillators of P10–12 rats, as at P0–4, appear to operate as simple alternating half-centres that generate equal flexion and extension phases.

Discussion

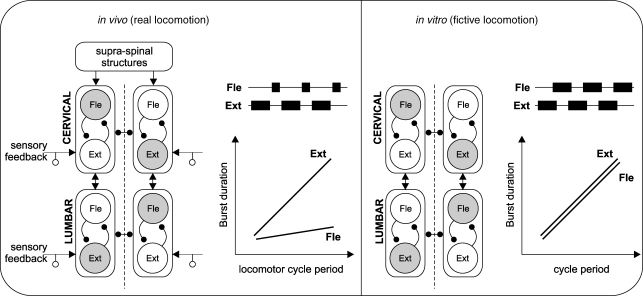

This study has shown that after isolation in vitro, and under either chemical or brainstem electrical activation, the neonatal rat spinal cord generates locomotor-related rhythmicity with a single pattern of coordination in which antagonistic flexor and extensor bursts occupy similar proportions of each cycle. Moreover, the durations of both flexor and extensor phases of the motor rhythm at both cervical and lumbar levels remain positively correlated with cycle duration. It is noteworthy that this covariation seen in our pooled measurements was also observed in data from individual in vitro preparations and therefore did not merely result from combining burst and cycle duration measurements from different experiments. Despite significant modifications in cycle period (by manipulation of NMA concentration or by altering parameters of brainstem stimulation), the fictive gait generated by the isolated cord always corresponded to quadrupedal walking, i.e. alternating bursting in homologous (left–right) motoneurons of the same (cervical or lumbar) segment as well as in homolateral antagonistic (flexor–extensor) motoneurons.

During normal locomotion, proprioceptive feedback from limb muscles and joints as well as descending inputs to the spinal cord have been repeatedly reported to play a crucial role in setting the overall timing of the step cycle by adjusting the durations of the extensor (stance) and flexor (swing) phases of the step cycle and regulating the transitions between these cycle phases (for recent reviews, see McCrea, 2001; Lam & Pearson, 2002; Rossignol et al. 2006). By selectively phase-advancing or -delaying components of the step cycle, proprioceptive afferents can adjust the frequency of stepping and match CPG output to actual limb forces and movements. During normal overground or treadmill stepping, intact adult animals usually adapt their speed through a shortening of the stance phase as speed increases, whereas the swing phase remains relatively constant (Goslow et al. 1973; Grillner, 1981; Halbertsma, 1983; Nicolopoulos-Stournaras & Iles, 1984; see Fig. 6, left). A similar asymmetric control of extensor phase duration has been reported in spinalized cats during different speeds of treadmill locomotion (Barbeau & Rossignol, 1987), indicating that proprioceptive inputs from muscles and/or joints play the major role in locomotor speed adaptation.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of locomotor circuitry responsible for flexor (Fle) and extensor (Ext) burst activity during real (in vivo) and fictive (in vitro) quadrupedal locomotion Shaded circles denote coincident flexor/extensor activity at bilateral cervical (C5, C8) and lumbar (L2, L5) levels. Note left–right and homolateral flexor–extensor alternation that corresponds to a walking gait. In the intact stepping animal (left panel) with brainstem descending pathways and movement-derived sensory input from the limbs, the step cycle is dominated by extensor muscle activity, the duration of which is positively correlated with the cycle period, while flexor activity changes much less. In the isolated cord, however (right panel), descending and sensory inputs are absent and the fictive locomotor pattern now consists of symmetrical flexor–extensor alternation, with bursts in both phases displaying a positive correlation with cycle duration. See Discussion for further explanation.

Surprisingly, however, direct evidence for such an adaptive influence has been fragmentary and even conflicting. For example, in an early study on fictive locomotor patterns recorded from spinalized and paralysed cats, no significant differences between the slopes of the burst–cycle duration relationship for limb flexor and extensor motoneurons were observed (Baker et al. 1984). In contrast, a weak or absent dependence of flexor burst duration on cycle period was reported for fictive locomotor patterns recorded from deafferented decorticate cats (Grillner & Zangger, 1984), or paralysed (Grillner & Dubuc, 1988) or de-efferented spinal preparations (Pearson & Rossignol, 1991). These observations therefore appeared to suggest that phasic sensory feedback does not after all make a major contribution to extensor/flexor burst duration asymmetries in the normal intact animal. Indeed, it has been inferred that the preferential alteration in extensor burst duration during changing locomotor speeds derives from hard-wired asymmetry in the central locomotor CPG circuitry itself (Grillner & Dubuc, 1988), since in spinal and decorticate cat preparations, flexor and extensor burst durations appeared to show the same asymmetrical relationship with cycle duration as in ordinary intact locomotion.

Inconsistent data have also been previously reported in the neonatal rat. For example, Navarrete et al. (2002) reported that l-DOPA-induced locomotion in freely moving P7–9 rats differs from overground locomotion in the adult in that the activity durations of extensor and flexor muscles in the postnatal animal appear to be equally correlated to step cycle period. However, this conclusion derived from a limited range of cycle durations for a given preparation, thereby risking ambiguity in apparent burst–cycle duration relationships. In contrast, Kiehn & Kjaerulff (1996) reported in semi-isolated P0–4 spinal cord preparations with one attached hindlimb that during dopamine (but not 5HT) activation of fictive locomotion, extensor EMG burst durations varied more with cycle period than flexor muscle bursts. However, this asymmetry was apparently unaffected by a dorsal rhizotomy in two preparations (see also Kudo & Yamada, 1987), thereby implying that sensory feedback was not after all involved in shaping the respective extensor/flexor burst–cycle duration relationships. Moreover, it was suggested that differences in the degree of extensor dominance seen under DA and 5HT could result from differential contributions of these neurochemicals to rhythm induction (Kiehn & Kjaerulff, 1996; see also Barthe & Clarac, 1997). However, in our experiments on completely isolated spinal cords, although exposure to 5HT alone or in combination with DA produced locomotor rhythms with widely different frequency ranges, the basic unbiased temporal organization of the two patterns remained similar. In addition, our finding that brainstem electrical stimulation also elicited symmetrical flexor/extensor locomotor patterns further argues against the possibility that pharmacological rhythm-induction was somehow responsible for selectively altering the relationship between flexor burst duration and cycle period. Finally, the striking difference between the symmetrical locomotor patterns that we observed in the completely isolated spinal cord with the extensor-dominated rhythms in bilateral hindlimb-attached preparations in which proprioceptive pathways are preserved remains consistent with the idea that movement-generated afferent signals are normally responsible for imposing adult-like extensor/flexor burst asymmetry.

The possibility that the extensor phase dominance seen during intact adult locomotion may reflect an intrinsic asymmetry in central locomotor circuitry has also been called into question by a recent study of brainstem stimulation-induced fictive locomotion in adult decerebrate cats (Yakovenko et al. 2005). Those authors reported that depending on the experimental animal, spontaneous variations in the cycle duration of fictive locomotion could be due to changes in either extensor or flexor phase durations. Similar transitions between extensor and flexor dominant behaviour were also previously observed in decerebrate rats (Iles & Nicolopoulos-Stournaras, 1996). On the basis of modelling, moreover, Yakovenko et al. (2005) suggested that such alternative phase dominance in paralysed animals could be explained by inherent, animal-specific imbalances in the background excitatory drive to the extensor and flexor CPG half-centres, but that in the normal intact cat, peripheral inputs ensure that extensor-biased patterns predominate (also see below). Our present results are therefore consistent with, and extend on, this view (see also Baker et al. 1984): in the completely isolated cord under steady-state in vitro conditions (Fig. 6, right), the half-centres of each locomotory CPG are presumably exposed to equivalent levels of drug-derived excitation, thereby resulting in an inherent unbiased drive to flexor and extensor motoneurons at all cycle frequencies.

This lack of bias in the fictive locomotor patterns of isolated spinal cords from both P0–4 and older P10–12 animals alike was also evident from the similarity in the duty cycles of flexor and extensor bursts, both of which remained relatively constant at 50–55% at all cycle periods. This is in contrast to the significantly differing flexor/extensor duty cycle ratios found during body-supported overground locomotion in P3 and P10 rats (Jamon & Clarac, 1998), where flexor and extensor muscle activity occupies ca 30% and 70%, respectively, of an average step cycle (see also Fig. 5Ab). Similar differences in the flexor/extensor duty cycles are also evident in limb muscle and nerve recordings during real and fictive locomotion in mice (see for example Fig. 1 in Gordon & Whelan, 2006). Whereas a typical extensor phase-dominance is apparent in hindlimb EMG recordings during adult animal treadmill walking, extensor and flexor motor bursts occupy similar portions of each cycle during locomotor-related activity in the isolated spinal cord (Whelan et al. 2000). Finally, it is interesting that flexor/extensor burst relationships have been found to vary presumably as a function of load sensing during rhythmic leg movements. For example, more flexor-dominant locomotor patterns have been observed during unloaded-limb swimming movements in rats (Iles & Coles, 1991). More recently, during treadmill stepping in human infants when ground contact is preferentially loading the limbs during extension phase of each movement cycle, an extensor biasing is observed, while a switch to a flexor-dominated pattern occurs when the limbs are loaded more during the flexion phase while the infant is air-stepping (Musselman & Yang, 2007).

In conclusion, our findings in the rat at early postnatal and juvenile stages are in general agreement with the original hypothesis of Engberg & Lundberg (1969) in which the unit CPG for both fore- and hindlimb movements consists of simple flexor and extensor half-centres that contribute equally to rhythmogenesis, but during normal locomotion, an extensor half-centre dominance is conferred by sensory information feedback from the moving limb.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from “Conseil Régional d'Aquitaine/Fond Européen du Développement Régional” and the “Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale”. Laurent Juvin was also supported by the “Demain Debout” and “Institut pour la Recherche sur la Moelle épinière et l'Encéphale” organisations. We also thank Charlotte Micon for assistance with the peripheral limb-nerve recording experiments.

References

- Armstrong DM. The supraspinal control of mammalian locomotion. J Physiol. 1988;405:1–37. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsuta Y, Garcia-Rill E, Skinner RD. Electrically induced locomotion in the in vitro brainstem–spinal cord preparation. Brain Res. 1988;470:309–312. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LL, Chandler SH, Goldberg LJ. l-dopa-induced locomotor-like activity in ankle flexor and extensor nerves of chronic and acute spinal cats. Exp Neurol. 1984;86:515–526. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(84)90086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballion B, Morin D, Viala D. Forelimb locomotor generators and quadrupedal locomotion in the neonatal rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1727–1738. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau H, Rossignol S. Recovery of locomotion after chronic spinalization in the adult cat. Brain Res. 1987;412:84–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91442-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrière G, Mellen N, Cazalets JR. Neuromodulation of the locomotor network by dopamine in the isolated spinal cord of newborn rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1325–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthe JY, Clarac F. Modulation of the spinal network for locomotion by substance P in the neonatal rat. Exp Brain Res. 1997;115:485–492. doi: 10.1007/pl00005718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalets JR, Sqalli-Houssaini Y, Clarac F. Activation of the central pattern generators for locomotion by serotonin and excitatory amino acids in neonatal rat. J Physiol. 1992;455:187–204. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley KC, Schmidt BJ. Some limitations of ventral root recordings for monitoring locomotion in the in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord preparation. Neurosci Lett. 1994;171:142–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90625-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuc R, Cabelguen JM, Rossignol S. Rhythmic fluctuations of dorsal root potentials and antidromic discharges of primary afferents during fictive locomotion in the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1988;60:2014–2036. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.60.6.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engberg I, Lundberg A. An electromyographic analysis of muscular activity in the hindlimb of the cat during unrestrained locomotion. Acta Physiol Scand. 1969;75:614–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1969.tb04415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon IT, Whelan PJ. Deciphering the organization and modulation of spinal locomotor central pattern generators. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:2007–2013. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goslow GE, Reinking RM, Stuart DG. The cat step cycle: hind limb joint angles and muscle lengths during unrestrained locomotion. J Morph. 1973;141:1–41. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051410102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S. Control of locomotion in bipeds, tetrapods and fish. In: Brookhardt JM, Mountcastle VB, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 2, The Nervous System. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1981. pp. 1179–1236. [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Dubuc R. Control of locomotion in vertebrates: spinal and supraspinal mechanisms. Adv Neurol. 1988;47:425–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Halbertsma J, Nilsson J, Thortensson A. The adaptation to speed in human locomotion. Brain Res. 1979;165:177–182. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Zangger P. The effect of dorsal root transection on the efferent motor pattern in the cat's hindlimb during locomotion. Acta Physiol Scand. 1984;120:393–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1984.tb07400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbertsma JM. The stride cycle of the cat: the modelling of locomotion by computerized analysis of automatic recordings. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1983;521:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iles JF, Coles SK. Effects of loading on muscle activity during locomotion in rat. In: Armstrong DM, Bush BMH, editors. Locomotor Neural Mechanisms in Arthropods and Vertebrates. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press; 1991. pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Iles JF, Nicolopoulos-Stournaras S. Fictive locomotion in the adult decerebrate rat. Exp Brain Res. 1996;109:393–398. doi: 10.1007/BF00229623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamon M, Clarac F. Early walking in the neonatal rat: a kinematic study. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1218–1228. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvin L, Simmers J, Morin D. Propriospinal circuitry underlying interlimb coordination in mammalian quadrupedal locomotion. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6025–6035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0696-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvin L, Simmers J, Morin D. Remote sensory control of locomotor pattern-generator coordination in neonatal rat. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2006;36:252.2. [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Butt SJ. Physiological, anatomical and genetic identification of CPG neurons in the developing mammalian spinal cord. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:347–361. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Kjaerulff O. Spatiotemporal characteristics of 5-HT and dopamine-induced rhythmic hindlimb activity in the in vitro neonatal rat. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1472–1482. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.4.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo N, Yamada T. N-Methyl-D,L-aspartate-induced locomotor activity in a spinal cord–hindlimb muscles preparation of newborn rat studied in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 1987;75:43–48. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T, Pearson KG. The role of proprioceptive feedback in the regulation and adaptation of locomotor activity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;508:343–355. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0713-0_40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblond H, Gossard JP. Supraspinal and segmental signals can be transmitted through separate spinal cord pathways to enhance locomotor activity in extensor muscles in the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1997;114:188–192. doi: 10.1007/pl00005619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea DA. Spinal circuitry of sensorimotor control of locomotion. J Physiol. 2001;533:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0041b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin D, Viala D. Coordinations of locomotor and respiratory rhythms in vitro are critically dependent on hindlimb sensory inputs. J Neurosci. 2002;22:4756–4765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-11-04756.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselman KE, Yang JF. Loading the limb during rhythmic leg movements lengthens the duration of both flexion and extension in human infants. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1247–1257. doi: 10.1152/jn.00891.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete R, Slawinska U, Vrbova G. Electromyographic activity patterns of ankle flexor and extensor muscles during spontaneous and L-DOPA-induced locomotion in freely moving neonatal rats. Exp Neurol. 2002;173:256–265. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolopoulos-Stournaras S, Iles JF. Motor neuron columns in the lumbar spinal cord of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1983;217:75–85. doi: 10.1002/cne.902170107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolopoulos-Stournaras S, Iles JF. Hindlimb muscle activity during locomotion in the rat (Rattus norvegicus) (Rodentia-Muridea) J Zool (Lond) 1984;203:427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Orlovsky GN, Deliagina TG, Grillner S. Quadrupedal locomotion in mammals. In: Orlovsky GN, Deliagina TG, Grillner S, editors. Neuronal Control of Locomotion: from mollusc to man. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 154–246. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson KG, Rossignol S. Fictive motor patterns in chronic spinal cats. J Neurophysiol. 1991;66:1874–1887. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.6.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol S, Dubuc R, Gossard JP. Dynamic sensorimotor interactions in locomotion. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:89–154. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawinska U, Majczynski H, Djavadian R. Recovery of hindlimb motor functions after spinal cord transection is enhanced by grafts of the embryonic raphe nuclei. Exp Brain Res. 2000;132:27–38. doi: 10.1007/s002219900323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JC, Feldman JL. In vitro brainstem–spinal cord preparations for the study of motor systems for mammalian respiration and locomotion. J Neurosci Methods. 1987;21:321–333. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerga J, Gramsbergen A. The development of locomotion in the rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;57:163–174. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90042-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan P, Bonnot A, O'Donovan MJ. Properties of rhythmic activity generated by the isolated spinal cord of the neonatal mouse. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2821–2933. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.6.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakovenko S, McCrea DA, Stecina K, Prochazka A. Control of locomotor cycle durations. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:1057–1065. doi: 10.1152/jn.00991.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaporozhets E, Cowley KC, Schmidt BJ. A reliable technique for the induction of locomotor-like activity in the in vitro neonatal rat spinal cord using brainstem electrical stimulation. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;139:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]