Abstract

The cells of the renal medulla produce large amounts of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) via cyclooxygenases (COX)-1 and -2. PGE2 is well known to play a critical role in salt and water balance and maintenance of medullary blood flow. Since renal medullary PGE2 production increases in antidiuresis, and since COX inhibition is associated with damage to the renal medulla during water deprivation, PGE2 may promote the adaptation of renal papillary cells to high interstitial solute concentrations. To address this question, MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase in the presence or absence of 20 μm PGE2 prior to analysis of (i) cell survival, (ii) expression of osmoprotective genes (AR, BGT1, SMIT, HSP70 and COX-2), (iii) subcellular TonEBP/NFAT5 abundance, (iv) TonEBP/NFAT5 transcriptional activity and (v) aldose reductase promoter activity. Cell survival and apoptotic indices after raising the medium tonicity improved markedly in the presence of PGE2. PGE2 significantly increased tonicity-mediated up-regulation of AR, SMIT and HSP70 mRNAs. However, neither nuclear abundance nor TonEBP/NFAT5-driven reporter activity were elevated by PGE2, but aldose reductase promoter activity was significantly increased by PGE2. Interestingly, tonicity-induced COX-2 expression and activity was also stimulated by PGE2, suggesting the existence of a positive feedback loop. These results demonstrate that the major medullary prostanoid, PGE2, stimulates the expression of osmoprotective genes and favours the adaptation of medullary cells to increasing interstitial tonicities, an effect that is not explained directly by the presence of TonEs in the promoter region of the respective target genes. These findings may be relevant in the pathophysiology of medullary damage associated with analgesic drugs.

During antidiuresis, the cells of the renal medulla are exposed to a uniquely harsh environment, characterized by extreme concentrations of NaCl and urea, in addition to low oxygen tension (Brezis & Rosen, 1995; Neuhofer & Beck, 2005). Furthermore, during transition from diuresis to antidiuresis and vice versa, these cells are challenged by massive changes in interstitial solute concentrations. After stimulation of the urinary concentrating mechanism, renal papillary interstitial tonicity may double within a few hours (Beck et al. 1992). Specifically, it has been demonstrated that following intravenous administration of lysine-vasopressin, papillary tissue sodium concentration increases from approximately 140 to more than 300 mm within 2 h (Atherton et al. 1970).

After tonicity increase, renal papillary cells initially shrink, thus leading to elevated concentration of intracellular electrolytes (i.e. the cellular ionic strength). The cells then activate volume regulatory mechanisms, which in turn allow restoration of cell volume, although intracellular ion concentrations remain elevated. A sustained rise in cellular ionic strength is, however, associated with DNA double-strand breaks and induces apoptosis in renal epithelial cells (Galloway et al. 1987; Kültz & Chakravarty, 2001). In the longer term, medullary cells achieve osmotic equilibrium with the high interstitial solute concentrations by intracellular accumulation of small, non-perturbing organic compounds i.e. compatible osmolytes, including myo-inositol, sorbitol and betaine (Burg et al. 1997; Neuhofer & Beck, 2005). The elevated intracellular concentration of these substances predominantly results from increased uptake from the extracellular space (myo-inositol, betaine) or from intracellular synthesis (sorbitol). The proteins involved in intracellular osmolyte accumulation include the sodium-dependent myo-inositol cotransporter-1 (SMIT1), the sodium- and chloride-dependent betaine/GABA transporter-1 (BGT1), and aldose reductase (AR), which converts glucose to sorbitol. In addition, the expression of HSP70, a molecular chaperone expressed abundantly in the renal papilla (Cowley et al. 1995), is stimulated by tonicity stress and is believed to contribute to protection of medullary cells from the acute effects of hypertonicity (Neuhofer & Beck, 2005). The expression of the genes involved in osmolyte accumulation and that of HSP70 is stimulated by a common transcriptional activator, tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein/nuclear factor of activated T cells-5 (TonEBP/NFAT5) (Woo et al. 2002a, b). The importance of this transcriptional activator for the cells of the renal medulla has been demonstrated in mice lacking TonEBP/NFAT5 (Lopez-Rodriguez et al. 2004). These animals show renal medullary atrophy as a result of reduced expression of tonicity-responsive genes (Lopez-Rodriguez et al. 2004).

The action of cyclooxygenases (COX) in the renal medulla contributes importantly to the adaptation of medullary cells to their hostile environment. It has been well documented that prostanoids are important modulators of both medullary perfusion and tubular solute reabsorption, thereby linking tubular work to oxygen availability (Navar et al. 1996; Pallone et al. 2003; Neuhofer & Beck, 2005). In agreement, during antidiuresis, the renal medulla produces large amounts of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), most likely via COX-2, that is expressed constitutively in the renal medulla (Yang, 2003; Yang et al. 2005). COX inhibition by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) has long been known to be associated with renal medullary injury, particularly in situations with stimulation of the renal concentrating mechanism (Schlöndorff, 1993; De Broe & Elseviers, 1998). Thus, the major medullary prostanoid, PGE2, may promote the adaptation of papillary cells to increasing interstitial solute concentrations. This study aimed to address the question of whether PGE2 improves survival of medullary cells exposed to osmotic stress.

Methods

Cell culture and experimental protocol

Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CCL 34). The cells were maintained under standard conditions in Dulbecco's modified Eagles' medium (low glucose) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Two days prior to the experiments, the cells were plated in 60 mm, 35 mm (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany), or 24-well plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and grown to confluence. Subsequently, the medium tonicity was gradually increased over 2 h in eight steps (addition of 25 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 NaCl every 15 min; final medium osmolality 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1). To elevate the medium tonicity to 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, osmolality was raised in 16 steps of 25 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 each by NaCl addition over 4 h. Tonicity increases were performed by adding the required volumes of a 4 m NaCl stock solution drop by drop to the dishes. Changes in pH and temperature as well as mechanical agitation were kept to a minimum. The isotonic control cells were treated accordingly, except that equal volumes of PBS were added to the cells, thus ruling out that the experimental procedure per se had negative effects on cell viability. Tonicity was increased either in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (Sigma, Schnelldorf, Germany; dissolved as a 20 mm stock solution in ethanol) or the same volume of vehicle alone. Subsequently, the cells were processed as indicated.

Northern blot analysis

Following the treatments, the cells were lysed by the addition of TRI reagent (1 ml per 60 mm dish; PeqLab, Erlangen, Germany) and total RNA was recovered according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Aliquots of 20 μg were electrophoresed through 1% agarose–formaldehyde gels, subsequently blotted onto positively charged nylon membranes (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and immobilized by UV crosslinking as described elsewhere (Neuhofer et al. 2002). Relative mRNA abundance of the respective genes was monitored by hybridization with the following digoxigenin-labelled cDNAs: human AR (GenBank accession number J05474), canine SMIT1 (M85068), canine BGT1 (M80403), human inducible HSP70 (M11717), bovine COX-2 (AF031698) and human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; X01677). Generation of non-radioactive, digoxigenin-labelled probes, hybridization conditions and stringency washes are described in detail elsewhere (Neuhofer et al. 2002). Signals were subsequently quantified using Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MA, USA) and the mRNA abundance of each individual gene was normalized to that of GAPDH to correct for differences in RNA loading.

Determination of TonEBP/NFAT5 cytosolic and nuclear abundance

Subcellular extracts were prepared with nuclear and cytosolic extraction reagents (NE-PER; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, with broad specificity protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) added at 1: 100 (v/v). Aliquots of 10 μg from each fraction were run subsequently on 8% SDS–polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking non-specific binding sites with blocking buffer (5% non-fat dry milk–0.1% Tween-20 in PBS) for 1 h, TonEBP/NFAT5 abundance was determined by incubation with TonEBP/NFAT5 antiserum (1: 3000; Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C. Following washing with PBS–0.1% Tween-20 (3 × 5 min) and incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1: 10 000 in blocking buffer, 1 h incubation at room temperature), bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce) and analysed using Image J software.

Reporter gene assays

For assessment of TonEBP transcriptional activity, a reporter construct based on secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) (Berger et al. 1988) was prepared. SEAP is a truncated form of human placental alkaline phosphatase lacking the membrane anchoring domain. Thus, the truncated enzyme is secreted efficiently into the culture supernatant and SEAP activity in the supernatant is directly proportional to SEAP mRNA and protein abundance (Berger et al. 1988; Cullen & Malim, 1992). For generation of a TonE-driven SEAP construct, a DNA fragment containing two copies of the human TonE sequence with adjacent KpnI and Bgl II sites was prepared and inserted into the respective sites of pSEAP-control (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA), thereby adding the 2×TonE sequence upstream from the SV40 early promoter. Subsequently, the 2× TonE-SV40 early promoter fragment was released by KpnI and NruI and inserted into the respective sites of pSEAP-basic (Clontech). In the final construct, pSEAP-TonE, the SEAP-gene is preceded by two copies of the human TonE sequence and the SV40 early promoter, respectively (see also Fig. 6).

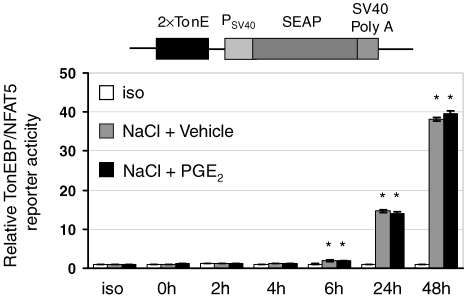

Figure 6.

Effect of PGE2 on TonE-driven reporter activity MDCK cells were stably transfected with a TonE-driven secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter construct. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle), or were kept in isotonic medium (iso). Relative SEAP activity in the cell culture supernatant was assessed at the indicated time points as described in Methods. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 4–8; *P < 0.05 versus iso.

To assess the effect of PGE2 in the context of a native promoter, a 1.5 kb fragment corresponding to nucleotides −1505 to +22 of the human aldose reductase promoter was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA from HEK 293 cells by PCR using primers 5′-AGCT-CGAGCAAACCAACAACAAAGCCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCAAGCTTCGCGTACCTTTAAATAGCCC-3′ (reverse), which introduced XhoI and Hind III sites to 5′- and 3′-ends, respectively. The fragment was subsequently inserted into the corresponding sites of pSEAP2-basic (Clontech). This region has been shown previously to confer osmotic inducibility and to contain at least one TonE (Ruepp et al. 1996; Nadkarni et al. 1999). The final construct, pSEAP-ARpro, was sequenced to verify orientation and sequence of the insert.

For stable transfection of MDCK cells with the TonE construct, exponentially growing cells were transfected (5 μg DNA per 60 mm dish) using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. As pSEAP-2×TonE lacks eukaryotic selection markers, the cells were cotransfected with a 20: 1 molar ratio of pSEAP-2×TonE and pcDNA3.1 (containing a neomycin-resistance gene; Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). Following selection with 600 μg ml−1 geneticine, 40 stable clones were expanded and assessed for tonicity-inducible SEAP activity (see below). Several healthy clones with highly tonicity-inducible SEAP activity were subsequently pooled and used for experiments at passages 3–6 (in the following denoted as MDCK-pSEAP-TonE).

To assess the effect of PGE2 on TonEBP transcriptional activity under hypertonic conditions, MDCK-pSEAP-TonE cells were seeded in a 24-well plate 2 days prior to the experiment at a density to reach confluence within 2 days. Prior to the experiments, the medium (1 ml DMEM without phenol red lacking G418 per well) was refreshed and the cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 500 mosmol kg−1 as described above. After the indicated periods, 50 μl medium was removed and stored in 96-well plates at −80°C for further analysis. Prior to determination of SEAP activity, the 96-well plates containing the conditioned medium were sealed and incubated for 45 min in a water bath at 65°C to inactivate endogenous alkaline phosphatase activity, since SEAP is extremely heat stable (Cullen & Malim, 1992). Subsequently, 150 μl p-nitrophenyl phosphate liquid substrate (Sigma) was added and the mixture incubated for 1–2 h at room temperature. Finally, SEAP activity was assessed at 405 nm in a microplate reader.

Transient transfections were performed in 24-well plates at 50–75% cell confluence with a 3: 1 molar ratio of pSEAP-ARpro and pcDNA3-LacZ using Effectene transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24 h, the cells were used for experiments, and SEAP activity was determined as described above and subsequently normalized to that of β-galactosidase. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and lysed in situ by vigorous shaking for 5 min after the addition of 135 μl TBS–0.1% Triton X-100, followed by two freeze–thaw cycles. Then, 600 μl β-galactosidase substrate was added per well (0.1 mm chlorophenol red-beta-d-galactopyranoside (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, containing 2 mm DTT and 1 mm MgCl2). The reaction was incubated for 2–4 h at room temperature and finally read at 574 nm.

Assessment of cell survival

After the respective treatments, detached cells were aspirated, adherent cells were collected by trypsinization, and cell numbers in both fractions were counted in a haemocytometer. The surviving fraction was expressed as the adherent/total (adherent plus detached) cell ratio as previously described (Neuhofer et al. 2001).

Determination of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release

Following the respective treatments, a small aliquot of medium was removed and adherent cells were then collected and disrupted by repeated vigorous passage through a 26-gauge needle. LDH activity was determined using a commercially available assay and expressed as the ratio between the activities in the supernatant and total LDH activity (supernatant plus adherent) as previously described (Neuhofer et al. 2001).

Determination of caspase-3 activity

Caspase-3 activity was assessed using an assay based on the cleavage of a synthetic, p-nitroanilin-conjugated caspase-3 substrate (Asp-Glu-Val-Asp; CaspACE Assay System; Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, cells in 35-mm dishes were washed with ice-cold PBS after the indicated treatments and disrupted by the addition of 100 μl lysis buffer. After three freeze–thaw cycles, the lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 12 000 g at 4°C for 20 min. Caspase-3 activity was monitored in 10 μl aliquots from the supernatant by an increase in absorbance at 405 nm according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and was referred subsequently to the protein concentration in the cell lysates. Relative caspase-3 activity is expressed as nanomoles of p-nitroanilin released per milligram of protein in 1 h.

Determination of COX activity

COX activity in lysates of MDCK cells was assessed using a commercially available assay (COX activity assay kit; Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) based on the colourimetric measurement of the peroxidase activity of cyclooxygenase by monitoring the formation of oxidized N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylendiamine (TMPD) at 620 nm. Briefly, cells were washed with ice-cold TBS and harvested in 200 μl TBS containing 1 mm EDTA and 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), and lysed mechanically by repeated vigorous passage through a 26-gauge needle. Subsequently, the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 12 000 g for 15 min at 4°C and COX activity was assessed on equal volumes of the supernatant according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. To distinguish COX-2 from COX-1 activity, the samples were compared to a corresponding one containing an isoenzyme-specific inhibitor for COX-2 and COX-1, respectively (DuP-697, SC-560; 300 nm final concentration each). Subsequently, COX activity was normalized to the protein concentration in the lysates and expressed as U (μg of protein)−1.

Measurement of intracellular electrolytes

MDCK cells were grown on collagen-coated filter membranes (Millicell-CM; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). At the end of the experiments, the medium was removed rapidly and the filters covered with a standard albumin solution applied on both apical and basal sides and snap frozen in a mixture of propane and isopentane (3: 1 v/v; −196°C) as described elsewhere (Beck et al. 1992; Neuhofer et al. 2002). The standard albumin solution was prepared by dissolving 2 g bovine serum albumin in 10 ml of the respective medium. Cryosections (1 μm) were cut at −80°C using an ultracryomicrotome (LKB, Bromma, Sweden). The cryosections were then freeze-dried and analysed in a scanning electron microscope equipped with an X-ray detector system as described in detail elsewhere (Beck et al. 1992). Intracellular electrolyte concentration is expressed as mmol (kg wet weight)−1.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. The significance of differences between the means was assessed by Student's t test. P < 0.05 was regarded as significant.

Results

Effect of PGE2 on survival of MDCK cells under hypertonic conditions

To determine whether PGE2 enhances cell survival under osmotic stress, MDCK cells were subjected to a gradual tonicity increase to 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by NaCl addition over a period of 4 h in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 or only vehicle ethanol. Comparable tonicity increases have been observed in the papilla of the mammalian kidney in vivo 2–4 h following acute stimulation of the urinary concentrating mechanism (Atherton et al. 1971). As the interstitial tonicity rises continuously over several hours after stimulation of the urinary concentrating mechanism, in the present experiments a nearly linear osmolality increase was employed to mimic more closely the situation in the renal medulla in situ compared with a single step increase.

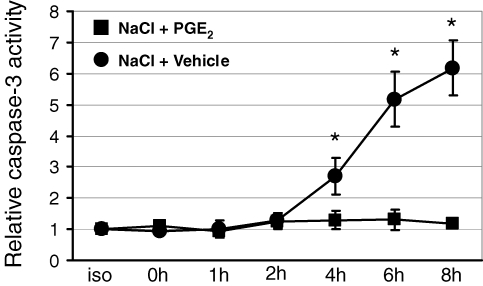

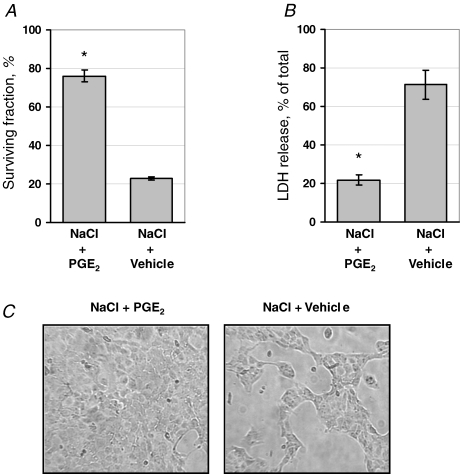

Since hypertonicity induces apoptosis in non-protected cells, the effect of PGE2 on tonicity-induced caspase-3 activation was measured. As shown in Fig. 1, caspase-3 activity time-dependently increased after elevating the medium tonicity in the absence of PGE2. However, when PGE2 was present from the beginning of the tonicity increase, caspase-3 activity remained at levels not different from isotonic controls, indicating protection from tonicity-induced apoptosis by PGE2. The same effect was evident when markers of cell damage were assessed. As shown in Fig. 2A, the vast majority of cells detached 20 h after the tonicity increase in the absence of PGE2. In the presence of PGE2, however, the cell monolayer remained largely intact (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, PGE2 significantly prevented LDH release into the medium after elevating the medium osmolality (Fig. 2B).

Figure 1.

Effect of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) on tonicity-induced caspase-3 activation MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 over 4 h by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle). At the times indicated after reaching the final osmolality of 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, relative caspase-3 activity was determined as described in Methods. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 4–6; *P < 0.05 versus NaCl + PGE2.

Figure 2.

Effect of PGE2 on cell survival of MDCK cells under hypertonic conditions MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 over 4 h by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle). Twenty hours after reaching the final osmolality of 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, cell survival was assessed. A, percentage of surviving cells determined as described in Methods. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 4; *P < 0.05 versus NaCl + vehicle. B, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release expressed as percentage of total LDH activity of the respective cultures. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 4; *P < 0.05 versus NaCl + vehicle. C, representative phase contrast micrographs of the cells remaining attached to the culture dish 20 h after tonicity increase.

Effect of PGE2 on expression of osmoprotective genes

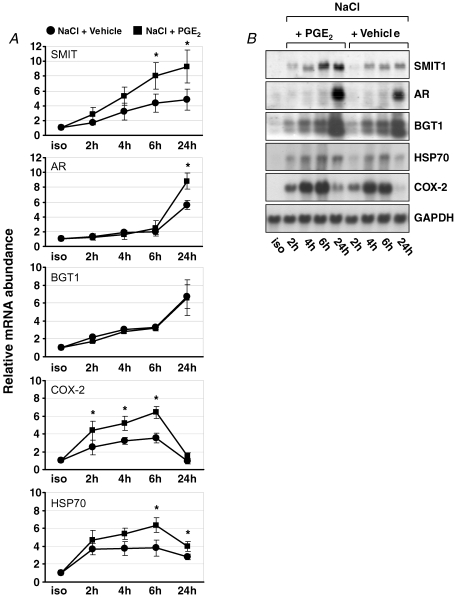

To determine whether protection against tonicity-induced cell damage by PGE2 is associated with enhanced expression of osmoprotective genes, mRNA abundance of several osmosensitive genes was determined. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, SMIT1, AR and BGT1 mRNA abundance increased time dependently in MDCK cells after raising the medium osmolality. Up-regulation of SMIT and BGT1 preceded that of AR. Addition of PGE2 further enhanced SMIT and AR mRNA expression, but interestingly, not that of BGT1.

Figure 3.

Effect of PGE2 on expression of osmoprotective genes in MDCK cells under hypertonic conditions MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle), or were kept in isotonic medium (iso). The expression of the respective genes (SMIT, sodium myo-inositol cotransporter-1; AR, aldose reductase; BGT1, betaine/GABA transporter-1; HSP70, heat shock protein 70; COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) was determined at the times indicated after reaching the final osmolality of 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by Northern blot analysis. A, relative mRNA abundance was normalized to that of GAPDH. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 4; *P < 0.05 versus NaCl + vehicle. B, representative Northern blots.

In addition to genes involved in osmolyte accumulation, two other genes with osmoprotective functions, HSP70 and COX-2, were also assessed. As shown in Fig. 3, tonicity-induced up-regulation of HSP70 mRNA was more transient and declined with increased expression of AR, BGT1 and SMIT. In the presence of PGE2, induction of HSP70 was significantly enhanced. Interestingly, tonicity-induced COX-2 mRNA abundance was further enhanced, suggesting the presence of a positive feedback loop.

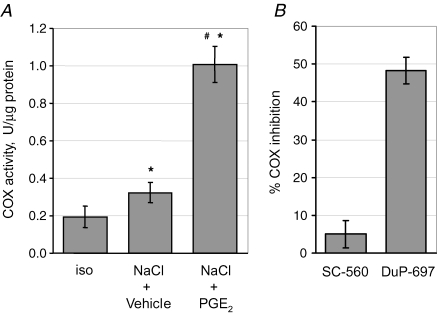

Effect of PGE2 on COX activity

As shown in Fig. 3, induction of COX-2 mRNA in response to osmotic stress was further enhanced in the presence of PGE2, suggesting the presence of a positive feedback loop. This phenomenon was also evident at the protein level (not shown). To assess whether these effects on COX-2 abundance are accompanied by parallel changes in COX-2 activity, the latter was determined in lysates from cells exposed to osmotic stress in the presence or absence of 20 μm PGE2. As shown in Fig. 4A, hypertonicity significantly increased COX activity, which was further stimulated about threefold by PGE2. Addition of DuP-697 (300 nm), a COX-2 specific inhibitor, to the reaction reduced total COX activity by about 50%, whereas inclusion of SC-560 (300 nm), a COX-1 specific inhibitor, had only minor effects on COX activity, indicating that COX-2 accounts for the vast majority of COX activity and that COX-2 is indeed positively regulated by PGE2 in response to hypertonicity at the functional level.

Figure 4.

Effect of PGE2 on COX activity in MDCK cells exposed to osmotic stress MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle), or were kept in isotonic medium (iso). A, after 24 h, COX activity was determined as described in Methods. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 4; *P < 0.05 versus iso; #P < 0.05 versus NaCl + vehicle. B, the contribution of COX-1 and COX-2 isoforms to total COX activity in lysates from cells treated with NaCl in the presence of PGE2 was assessed by addition of COX-1 (SC-560) and COX-2 (Du-P697) specific inhibitors, respectively. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 4.

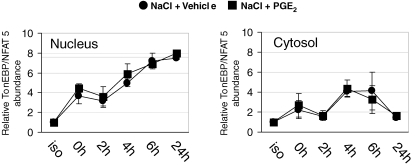

Effect of PGE2 on TonEBP/NFAT5 transcriptional activity

Following osmotic stress, expression of AR, BGT1, SMIT and HSP70 is stimulated by a common transcriptional activator, TonEBP/NFAT5. We therefore determined in the next step, whether the enhanced expression of AR, SMIT and HSP70 in the presence of PGE2 is related to increased TonEBP/NFAT5 activity.

Enhanced expression and translocation of TonEBP/NFAT5 from the cytosol to the nucleus represents an important mechanism regulating TonEBP/NFAT5 transcriptional activity (Cha et al. 2001). Therefore, nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared at different times after the tonicity increase in the presence or absence of PGE2. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, TonEBP/NFAT5 accumulated rapidly in the nucleus following osmotic stress; however, this translocation was not affected by PGE2. In cytosolic fractions, TonEBP/NFAT5 abundance was also not different. Likewise, total TonEBP/NFAT5 expression in whole cell lysates was equal in PGE2 and vehicle-treated cells (not shown). We can, however, not rule out the possibility that changes in TonEBP/NFAT5 transactivation activity, an important mechanism regulating TonEBP/NFAT5 activity (Ferraris et al. 2002), are affected by PGE2, because this parameter was not assessed in the present study.

Figure 5.

Effect of PGE2 on nuclear and cytosolic abundance of tonicity-responsive enhancer binding protein/nuclear factor of activated T cells-5 (TonEBP/NFAT5) under hypertonic conditions MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle), or were kept in isotonic medium (iso). At the times indicated after reaching the final osmolality of 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared and relative TonEBP/NFAT5 abundance within each fraction was determined by Western blot analysis. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 3–4.

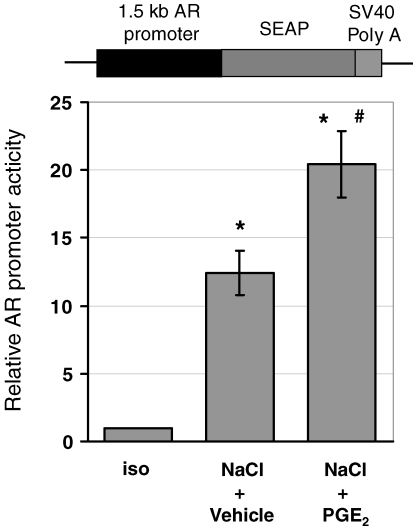

TonEBP/NFAT5 reporter activity was then assessed in MDCK cells stably transfected with a TonE-SEAP construct following osmotic stress in the presence and absence of PGE2. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, TonE-driven SEAP expression time dependently increased after raising the medium osmolality. This response was, however, not further enhanced by PGE2. To assess the effect of PGE2 in the context of a native promoter, additional reporter gene assays were performed using a 1.5 kb fragment of the AR promoter (Fig. 7). In contrast to the results obtained with the TonE-driven construct, PGE2 significantly stimulated AR promoter-driven reporter activity in response to an increase in tonicity. In aggregate, these data indicate that the presence of TonEs is not sufficient to explain the effect of PGE2 on AR promoter activity and on the expression of osmoprotective genes. Putative, yet unidentified, factors probably contribute.

Figure 7.

Effect of PGE2 on aldose reductase promoter activity MDCK cells were transiently transfected with a 1.5 kb aldose reductase promoter-driven secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter construct. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 500 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle), or were kept in isotonic medium (iso). Relative SEAP activity in the cell culture supernatant was assessed 24 h after tonicity increase as described in Methods. Means ±s.e.m. for n = 6. *P < 0.05 versus iso; #P < 0.05 versus NaCl + vehicle.

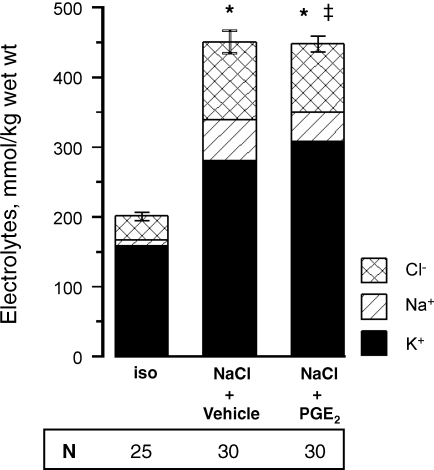

Effect of PGE2 on intracellular electrolytes

In cells exposed to osmotic stress, the intracellular concentration of monovalent ions is increased substantially in the initial phase. Subsequently, intracellular electrolytes are continuously replaced by metabolically neutral organic osmolytes, a process requiring up to several days. To assess whether PGE2 affects cellular ionic strength (which is determined largely by the sum of intracellular Na+, Cl− and K+ concentrations), MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 over 4 h. After an additional 6 h at 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, intracellular electrolytes were determined by electron microprobe analysis. Since progressive cell detachment occurs after 6 h at 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 in the absence of PGE2, extension of the observation period was not feasible. As shown in Fig. 8, cellular ionic strength was elevated substantially after 6 h in MDCK cells exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, both in the presence of PGE2 or vehicle as compared with cells kept in isotonic medium (300 mosmol (kg H2O)−1). Although intracellular concentrations of Na+ and Cl− were less in the presence of PGE2, those of K+ were higher than in vehicle-treated cells, thus resulting in comparable cellular ionic strength. The results suggest that organic osmolytes have not been accumulated in significant amounts after 6 h, and that enhanced expression of HSP70 may be more relevant for cytoprotection by PGE2.

Figure 8.

Effect of PGE2 on intracellular electrolyte concentrations in MDCK under hypertonic conditions MDCK cells were exposed to a gradual tonicity increase to 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1 by NaCl addition in the presence of 20 μm PGE2 (NaCl + PGE2) or vehicle ethanol (NaCl + vehicle), or kept in isotonic medium (iso). Then, 6 h after reaching the final osmolality of 700 mosmol (kg H2O)−1, intracellular concentrations of Na, Cl and K were determined by electron microprobe analysis. The number of intracellular measurement (N) is indicated. *P < 0.05 versus iso; ‡P < 0.05 versus NaCl + vehicle for Na and K.

Discussion

Analgesic drug-induced nephropathy accounts for a significant proportion of patients with chronic renal failure (De Broe & Elseviers, 1998). Even short-term use of these compounds may result in impaired renal function, in particular when accompanied by dehydration (Schlöndorff, 1993; De Broe & Elseviers, 1998; Kovacevic et al. 2003). This phenomenon has been traditionally ascribed to an imbalance between medullary vasoconstrictors (i.e. angiotensin II, arginine–vasopression, endothelin and others) to medullary vasodilators (i.e. nitric oxide, prostacyclin, PGE2), thus resulting in hypoxic damage of medullary cells (Schlöndorff, 1993; Brezis & Rosen, 1995). In particular, the production of the latter two substances is impeded by NSAIDs, indicating that prostanoids may contribute decisively to the survival of medullary cells in conditions associated with stimulation of the urinary concentrating mechanism.

During antidiuresis, the renal inner medulla is not only chronically hypoxic, but is also characterized by extreme interstitial solute concentrations (Neuhofer & Beck, 2005). It is thus conceivable that medullary prostanoids not only improve medullary oxygen balance but also favour the adaptation of medullary cells to high interstitial solute concentrations. In agreement, PGE2, the major medullary prostanoid, is produced in large amounts in the renal medulla during antidiuresis (Breyer & Breyer, 2001; Yang, 2003).

Indeed, the present observations clearly demonstrate that PGE2 promotes survival of MDCK cells exposed to osmotic stress, which coincided with enhanced expression of osmoprotective genes (SMIT, AR, HSP70). In the present experiments, extracellular tonicity was raised almost linearly over several hours, an approach which more closely resembles the situation in the renal papilla in situ, than does a one-step elevation that has been employed in most experimental models to date. A comparable increase in interstitial tonicity has been reported in the papilla of the mammalian kidney in vivo following acute stimulation of the urinary concentrating mechanism (Atherton et al. 1971). Enhanced cell survival has been directly demonstrated following a gradual increase in osmolality (Cai et al. 2002). In contrast to a step increase, cells exposed to a gradual tonicity increase are unlikely to show a significant reduction in cell volume by virtue of the concurrent operation of volume regulatory mechanisms, a situation known as isovolumetric regulation (Lohr & Grantham, 1986). This is achieved by gradual uptake of electrolytes from the extracellular space and intracellular accumulation of organic osmolytes with increasing extracellular osmolality and osmotically obliged water entry, thus allowing maintenance of cell volume (Rome et al. 1989). Nonetheless, both a step and a gradual tonicity increase are associated with a rise in cellular ionic strength, which exerts adverse effects on cell viability, including DNA double strand breaks and induction of apoptosis (Galloway et al. 1987; Kültz & Chakravarty, 2001). In the longer term, renal medullary cells both in vivo and in vitro adapt to elevated extracellular solute concentrations by the accumulation of osmotically active, non-perturbing organic osmolytes, which replace intracellular ions. In conjunction with osmotic changes, there is enhanced expression of cytoprotective heat shock proteins, mainly HSP70 (Cohen et al. 1991; Neuhofer & Beck, 2005).

The accumulation of significant amounts of organic osmolytes is, however, a relatively slow process, requiring up to several days. In agreement, in the present experiments, cellular ionic strength 6 h after a gradual tonicity increase was elevated to comparable levels in the presence of PGE2 or vehicle. These observations argue against the accumulation of significant amounts of organic osmolytes in this early phase. Nevertheless, caspase-3 activation at this time is completely prevented by PGE2 and cell survival is strongly enhanced after 20 h (Figs 1 and 2). As shown in Fig. 3, induction of HSP70 precedes that of SMIT and AR, suggesting that HSP70 may protect medullary cells in a situation in which compatible osmolytes are not yet present in sufficient amounts. In agreement, HSP70 potently blocks apoptosis at several levels, including direct interaction with caspase-3, thus impairing the execution of the apoptotic pathway (Ravagnan et al. 2001; Komarova et al. 2004). In addition to the increased mRNA abundance of HSP70 in the presence of PGE2, HSP70 was also induced more vigorously at the protein level when the hypertonic medium was supplemented with PGE2 (not shown). Thus, in the early phase of osmotic stress, HSP70 may be important for cell survival.

Tonicity-stimulated expression of AR, BGT1, SMIT and HSP70 has been demonstrated to be mediated by TonEBP/NFAT5 (Woo et al. 2002a, b). Although the activity of TonEBP/NFAT5 is required for tonicity-induced expression of osmoprotective genes (Na et al. 2003; Lopez-Rodriguez et al. 2004), the present data demonstrate enhanced expression of AR, SMIT, HSP70 and COX-2 in the presence of PGE2 in the absence of increased nuclear abundance or elevated TonE-driven reporter activity. Nevertheless, PGE2 significantly increased reporter activity in experiments using a 1.5 kb fragment of the AR promoter. These data indicate that the presence of TonEs is not sufficient to explain the effect of PGE2 on AR promoter activity and expression of osmoprotective genes. Probably, additional signalling events and transcriptional activators modulate the expression of osmoprotective genes, possibly via cooperative effects on TonEBP. This assumption is supported further by the lack of stimulation of BGT1 expression. Divergent pathways regulating the expression of SMIT and BGT1 have already been previously described (Atta et al. 1999). Additionally, tonicity-induced expression of COX-2 was also markedly stimulated by PGE2, although COX-2 is not a known TonEBP/NFAT5 target gene (Yang, 2003), further supporting the view that the stimulatory effect of PGE2 is not directly mediated via enhanced TonEBP-TonE signalling.

In summary, PGE2 promotes survival of MDCK cells exposed to osmotic stress, which occurred in parallel with enhanced expression of osmoprotective genes. The latter effect appears, however, not to be directly mediated by increased transcriptional activity of TONEBP/NFAT5. Tonicity-induced expression of COX-2 and activity was further stimulated by PGE2, indicating the existence of a positive feedback loop. This observation may reflect the requirement for the rapid production of PGE2 after stimulation of the urinary concentrating mechanism. Thus, elevated PGE2 concentrations during antidiuresis may not only help to prevent hypoxic injury to medullary cells, but also to promote osmoadaptation. The present concept that PGE2 promotes osmoadaptation of medullary cells is in good agreement with the observation that COX inhibition may be associated with renal papillary injury in vivo (Moeckel et al. 2003; Neuhofer et al. 2004), particularly when accompanied by dehydration.

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Deutsche Nierenstiftung and the Münchener Medizinische Wochenschrift. Critical reading of the manuscript by Dr J. Davis is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Atherton JC, Evans JA, Green R, Thomas S. The rapid effects of lysine-vasopressin clearance on renal tissue composition in the conscious water-diuretic rat. J Physiol. 1971;215:42P–43P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atherton JC, Green R, Thomas S. Effects of lysine-vasopressin dosage on renal tissue and urinary composition in the conscious, water diuretic rat. J Physiol. 1970;208:68P–69P. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atta MG, Dahl SC, Kwon HM, Handler JS. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and immunosuppressants perturb the myo-inositol but not the betaine cotransporter in isotonic and hypertonic MDCK cells. Kidney Int. 1999;55:956–962. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055003956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck FX, Schmolke M, Guder WG, Dorge A, Thurau K. Osmolytes in renal medulla during rapid changes in papillary tonicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1992;262:F849–F856. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1992.262.5.F849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J, Hauber J, Hauber R, Geiger R, Cullen BR. Secreted placental alkaline phosphatase: a powerful new quantitative indicator of gene expression in eukaryotic cells. Gene. 1988;66:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyer MD, Breyer RM. G protein-coupled prostanoid receptors and the kidney. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:579–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brezis M, Rosen S. Hypoxia of the renal medulla – its implications for disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:647–655. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503093321006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg MB, Kwon ED, Kultz D. Regulation of gene expression by hypertonicity. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:437–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q, Michea L, Andrews P, Zhang Z, Rocha G, Dmitrieva N, Burg MB. Rate of increase of osmolality determines osmotic tolerance of mouse inner medullary epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F792–F798. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00046.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha JH, Woo SK, Han KH, Kim YH, Handler JS, Kim J, Kwon HM. Hydration status affects nuclear distribution of transcription factor tonicity responsive enhancer binding protein in rat kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2221–2230. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12112221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DM, Wasserman JC, Gullans SR. Immediate early gene and HSP70 expression in hyperosmotic stress in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1991;261:C594–C601. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.4.C594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley BD, Jr, Muessel MJ, Douglass D, Wilkins W. In vivo and in vitro osmotic regulation of HSP-70 and prostaglandin synthase gene expression in kidney cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1995;269:F854–F862. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.269.6.F854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BR, Malim MH. Secreted placental alkaline phosphatase as a eukaryotic reporter gene. Methods Enzymol. 1992;216:362–368. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)16033-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Broe ME, Elseviers MM. Analgesic nephropathy. N Engl J Medical. 1998;338:446–452. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraris JD, Williams CK, Persaud P, Zhang Z, Chen Y, Burg MB. Activity of the TonEBP/OREBP transactivation domain varies directly with extracellular NaCl concentration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:739–744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241637298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway SM, Deasy DA, Bean CL, Kraynak AR, Armstrong MJ, Bradley MO. Effects of high osmotic strength on chromosome aberrations, sister-chromatid exchanges and DNA strand breaks, and the relation to toxicity. Mutat Res. 1987;189:15–25. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(87)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova EY, Afanasyeva EA, Bulatova MM, Cheetham ME, Margulis BA, Guzhova IV. Downstream caspases are novel targets for the antiapoptotic activity of the molecular chaperone hsp70. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:265–275. doi: 10.1379/CSC-27R1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacevic L, Bernstein J, Valentini RP, Imam A, Gupta N, Mattoo TK. Renal papillary necrosis induced by naproxen. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:826–829. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kültz D, Chakravarty D. Hyperosmolality in the form of elevated NaCl but not urea causes DNA damage in murine kidney cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1999–2004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohr JW, Grantham JJ. Isovolume tric regulation of isolated S2 proximal tubules in anisotonic media. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:1165–1172. doi: 10.1172/JCI112698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rodriguez C, Antos CL, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Lin F, Novobrantseva TI, Bronson RT, Igarashi P, Rao A, Olson EN. Loss of NFAT5 results in renal atrophy and lack of tonicity-responsive gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2392–2397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308703100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeckel GW, Zhang L, Fogo AB, Hao CM, Pozzi A, Breyer MD. COX2 activity promotes organic osmolyte accumulation and adaptation of renal medullary interstitial cells to hypertonic stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19352–19357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na KY, Woo SK, Lee SD, Kwon HM. Silencing of TonEBP/NFAT5 transcriptional activator by RNA interference. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:283–288. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000045050.19544.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni V, Gabbay KH, Bohren KM, Sheikh-Hamad D. Osmotic response element enhancer activity. Regulation through p38 kinase and mitogen-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20185–20190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navar LG, Inscho EW, Majid SA, Imig JD, Harrison-Bernard LM, Mitchell KD. Paracrine regulation of the renal microcirculation. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:425–536. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer W, Bartels H, Fraek ML, Beck FX. Relationship between intracellular ionic strength and expression of tonicity-responsive genes in rat papillary collecting duct cells. J Physiol. 2002;543:147–153. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer W, Beck FX. Cell survival in the hostile environment of the renal medulla. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:531–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.031103.154456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer W, Holzapfel K, Fraek ML, Ouyang N, Lutz J, Beck FX. Chronic COX-2 inhibition reduces medullary HSP70 expression and induces papillary apoptosis in dehydrated rats. Kidney Int. 2004;65:431–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhofer W, Lugmayr K, Fraek ML, Beck FX. Regulated overexpression of heat shock protein 72 protects Madin-Darby canine kidney cells from the detrimental effects of high urea concentrations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2565–2571. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V12122565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallone TL, Zhang Z, Rhinehart K. Physiology of the renal medullary microcirculation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F253–F266. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00304.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravagnan L, Gurbuxani S, Susin SA, Maisse C, Daugas E, Zamzami N, Mak T, Jaattela M, Penninger JM, Garrido C, Kroemer G. Heat-shock protein 70 antagonizes apoptosis-inducing factor. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:839–843. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rome L, Grantham J, Savin V, Lohr J, Lechene C. Proximal tubule volume regulation in hyperosmotic media: intracellular K+, Na+, and Cl−. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1989;257:C1093–C1100. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.257.6.C1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruepp B, Bohren KM, Gabbay KH. Characterization of the osmotic response element of the human aldose reductase gene promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8624–8629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlöndorff D. Renal complications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Kidney Int. 1993;44:643–653. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SK, Lee SD, Kwon HM. TonEBP transcriptional activator in the cellular response to increased osmolality. Pflugers Arch. 2002a;444:579–585. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0849-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SK, Lee SD, Na KY, Park WK, Kwon HM. TonEBP/NFAT5 stimulates transcription of HSP70 in response to hypertonicity. Mol Cell Biol. 2002b;22:5753–5760. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5753-5760.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T. Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 in renal medulla. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;177:417–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Zhang A, Honeggar M, Kohan DE, Mizel D, Sanders K, Hoidal JR, Briggs JP, Schnermann JB. Hypertonic induction of COX-2 in collecting duct cells by reactive oxygen species of mitochondrial origin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34966–34973. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]