Abstract

A successful clinical trial is dependent on recruitment. Between December 2003 and February 2006, our team successfully enrolled 289 participants in a large, single-center, randomized placebo-controlled trial (RCT) studying the impact of the patient-doctor relationship and acupuncture on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients. This paper reports on the effectiveness of standard recruitment methods such as physician referral, newspaper advertisements, fliers, audio and video media ( radio and television commercials) as well as relatively new methods not previously extensively reported on such as internet ads, ads in mass transit vehicles and movie theater previews. We also report the fraction of cost each method consumed and fraction of recruitment each method generated. Our cost per call from potential participants varied from $3–$103 and cost per enrollment participant varied from $12–$584. Using a novel metric, the efficacy index, we found that physician referrals and flyers were the most effective recruitment method in our trial. Despite some methods being more efficient than others, all methods contributed to the successful recruitment. The iterative use of the efficacy index during a recruitment campaign may be helpful to calibrate and focus on the most effective recruitment methods.

Introduction

Background

Recruitment continues to be an immense challenge to randomized clinical trials (RCT). Failure to achieve recruitment goals may jeopardize the quality of a study by compromising the study power, consuming resources allotted to other parts of the study and sometimes causing the broadening of the inclusion criteria potentially reducing the validity of the study (Adams et al. 1997). In addition, recruitment challenges are reported to be the cause of 45% of study delays with delays often exceeding six months. (Anderson 2001) Accurate prediction of the resources required to achieve recruitment goals is difficult due to an insufficient body of literature. The need for recruitment resources is frequently underestimated (Bjornson-Benson et al. 1993). Accurate allocation of such resources is critical, especially when effective, and sometimes expensive, advertising campaigns can be the difference between successful and failed recruitment efforts (Spilker 1991).

Furthermore, considering the importance of recruitment, it is remarkable that recruitment techniques seem to have remained relatively stable over the last 20 years (Bielski, & Lydiard, 1997). Some of the more common recruitment methods include media advertising i.e. television and newspaper advertisements (Bielski & Lydiard 1997), physician referrals (Adams et al., 1997), press releases/public service announcements (Flicker & Wark, 1997), posting fliers (Bjornson-Benson et al. 1993), random mailings (Messer et al 2006), and “cold” calls (Spilker 1991). Although researchers are becoming more sophisticated in terms of internet recruitment techniques, to fully utilize this medium, substantial planning and resources must be invested, which may be more feasible at an institutional level (Harris et al 2005) rather than individual departments and investigators. Even after such investments are made, these internet tools are still inaccessible to certain study populations, requiring continued use of the traditional recruitment methods. The effectiveness of each recruitment method may also depend on how its execution, for example, the time of year and location for outdoor advertising, time of day for television and radio advertising, circulation for all media advertising methods ability to target specific populations in a culturally competent manner (Linden et al. 2007).

Although most studies report the effectiveness of each recruitment method in terms of the number of interested potential participants who contact the study and the number ultimately who enroll (Connett et al. 1993), fewer studies also report the cost per call and the cost per randomization (Adams et al. 1997). Few, if any reports, allow for a precise effectiveness measure that integrates percent of call with percent of enrollments into a single relative measure of effectiveness. Such a cost analysis can be critical in deciding which recruitment methods to implement when resources are limited.

This paper seeks to add to the recruitment literature by including a comprehensive analysis of a wide variety of established recruitment methods, including television, newspaper, and magazine paid advertising, as well as physician referrals, and posting fliers. We will also introduce data on the effectiveness of several methods which are still relatively new to the field including advertising on the internet (Lutz & Henkind 2000, Ehrenberger 20003), in mass transit vehicles and before movie theater previews. Importantly, following the suggestion of previous researchers to develop “more sophisticated methods for monitoring cost and effectiveness,” (Adams et al. 1997, Ota et al 2006), we developed a novel measure that combines both cost and number of enrollments into a single metric that represents both the proportion of the budget consumed by a recruitment method and the proportion of enrollments it generated. Such a method allows an easy and precise comparison of the effectiveness of different recruitment methods.

Methods

We performed a NIH-funded placebo-controlled RCT testing the effect of the patient-physician relationship and acupuncture on irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients at a large tertiary care hospital in a major metropolitan area (Boston). Our accrual goal was 289 participants (262 patients for the main efficacy study and 27 additional patients for a nested qualitative study), which was successfully met. Details of the RCT design and methods are reported elsewhere (Conboy et al. 2006) and the results of the trial are currently being analyzed.

Recruitment Goals, Timeline and Strategy

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by chronic or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort, usually in the lower abdomen, which is associated with disturbed bowel function (i.e., diarrhea, constipation, or alternating constipation and diarrhea) and feelings of abdominal distention and bloating (Longstreth et al 2006). Between 10% and 15% of the population in Western societies report these symptoms; however, only 30% ever seek medical attention for their symptoms (Saito et al 2002). In the metropolitan area within a 25 mile radius of Boston, there is a population of about 1.3 million adults over 21 years of age (estimate based on 2004 census data and calculated as the sum of the census of Boston and one-third of the adjacent counties). This suggests the area includes over 180,000 people with symptoms that may indicate IBS. The recruitment effort lasted 26 months, from December, 2003 until February, 2006 when the last patient was screened and admitted to the trial. Our prospectively planned and overly optimistic recruitment strategy included obtaining two thirds of calls from physician referrals and the remainder from responses to fliers posted throughout the city. We originally budgeted $5000 for recruitment expenses. After four months of recruitment and one enrollment, it became apparent that our original strategy required evaluation and that the recruitment budget would need to be increased. After a decision to add recruitment methods such as the internet and paid media, we shifted all unessential costs (e.g., consultants, a planned six month subject follow-up) to pay for additional recruitment resources that would be needed to reach our goal. After demonstrating that our new methods were working, we received a small supplemental grant to finish recruitment. We decided to try more methods for recruitment and assess the effectiveness of each method. By making this radical shift, we were able to avoid corroding the integrity of our study by altering our eligibility requirements or reducing our sample size, problems that commonly affected by recruitment difficulty (Harris 2005).

Methods of Recruitment

Media Strategies

Paid advertisements were placed in two newspapers with metropolitan-wide circulations. Free classified ads were placed in local university newspapers. Paid 15-second television commercials were run at varying times of day on a local affiliate of a national broadcasting network and one cable network, with the text of our flier (see Figure 1) read aloud during the commercial. Paid advertisements were also shown before the previews in movie theaters.

Figure 1.

Photo courtesy of Rekha Murthy

Fliers and Brochures

Fliers were 8.5” × 11” posters printed in black on white or colored paper (Figure 1). Three main strategies were employed when posting fliers. The first strategy was posting fliers in locations where they were likely to be noticed by IBS sufferers. Primary locations were inside hospitals which gave IRB approval and outside additional hospitals, colleges, universities, libraries, religious institutions, and private businesses (e.g. restaurants, gyms, grocery stores and restaurants). The second strategy was to post fliers at certain days and times where they would be noticed, e.g. during special events in the metropolitan area. Specific events included Fourth of July celebrations, New Year’s Eve festivities, concerts, and major charity walks. The poster staff consisted primarily of college students that were paid at an hourly rate, while one was paid per poster.

Fliers were also mailed to local yoga teachers, chiropractors, massage therapists, tai chi centers, and other similar businesses asking them to post the flier. We assumed that acupuncture might be attractive to their clientele. In addition, one investigator (TK) regularly asked members of his religious congregation to hang fliers on bulletin boards at their workplaces. To what extent organizations or individuals followed-up with our requests is unknown.

Fliers and brochures were also sent or personally delivered to local gastroenterology and primary care practices to be displayed in waiting rooms. Practice managers were contacted to ensure we had permission to place information in waiting rooms. Again, whether our requests were honored is unclear. On the different university campuses in our area, we usually hired a local student who was familiar with the walking patterns and bulletin board situations at these institutions.

Staff adhered to certain practices to maximize the acceptability of the fliers. These practices consisted of removing old or damaged posters, not posting on clean surfaces, and responding and complying with all complaints including requests to remove fliers.

Mass transit

Ads were placed in both public and private forms of city-wide mass transit. Paid advertising in public mass-transit included large (11” × 27”), full-color posters called “car-cards” hung in approximately 100 subway cars over a one year period. Given the potential number of subway lines in the Greater Boston area, our strategy was to advertise on those lines that were both cost-effective and provided population diversity. Based on this criteria we placed ads on three train lines; one with the highest percentage of riders, another that served the area of our study site, and an additional line that both connected to the line serving the study site and served significant numbers of minority riders. Over the one-year period, the mix of lines, cars, duration, and number of car-cards was adjusted based on recruitment success. Free advertising in a private mass-transit system was employed throughout the recruitment process and consisted of hanging the same car-cards in commuter shuttles run by a local university to transport students and staff.

Internet

Short, text-only advertisements were placed on several websites for free, including clinicaltrials.gov, www.aboutibs.org, and craigslist.com. Websites were selected for their wide circulation and IBS-specific circulation. We also created our own website.

Referral

A large number of referrals were anticipated from the lead study gastroenterologist’s (AL) practice. In addition, the gastroenterology department of our local hospital had an outpatient pool of over 15,000 potential participants. Every six months, each doctor in the department, as well as every gastroenterologist in the Boston area, was called or emailed by the lead gastroenterologist (AL) or a member of the recruitment team and informational materials mailed or hand-delivered. All local private GI practices, as well as members of a GI motility group for physicians, and several local private psychology and general medicine practices received phone-calls and informational materials by mail. Informational materials consisted of an introductory letter and brochures. The lead study gastroenterologist (AL) also sent letters to patients in his practice, notifying them of the study.

Data Collection

During the initial screening call, a trained study staff member not otherwise connected with the study asked potential participants an open-ended question about how he/she learned about the study. A database was created in Microsoft Access to keep track of the callers who were responding to the advertisements and whether they were eligible, willing to participate, and if they passed the physical screening to enroll in the trial. We also tried tracked the exact location where flyers were reportedly seen to see whether any particular location continued to be high yield or not. Callers were logged and categorized by the type of recruitment method that prompted their calling. The methods used were grouped into six primary categories: fliers, mass transit ads, internet ads, newspaper ads, audio-visual commercials, and referrals. Callers who mentioned multiple recruitment methods, were categorized as “multiple sources” (2% of callers). Callers who could not identify how they were informed of the study were categorized as “unknown.” In addition, 23% of total callers were categorized in the database as “unknown.” Callers received this designation for a variety of reasons including: a) they discontinued the telephone conversation when it was clear that they did not want to participate in the study and before we could ask how they heard of the study, b) we were unable to reach them after they left a message on telephone answering machine, and c) they did not remember how they heard of the study. The costs of advertising were recorded for each of the recruitment methods.

Statistical Analysis

We descriptively report the costs, number of calls generated, and number of enrollments generated for each recruitment method. We calculated the cost per call generated and the cost per enrolled participant for each recruitment method from these data. To facilitate our analysis, we also developed several new mathematical measures that are defined below. Callers categorized as multiple sources or unknown were excluded from these calculations.

Enrollment Rate

We define Enrollment Rate (ER) as the proportion of callers who enrolled in the study. Thus, enrollment rate estimates the probability that a caller will enroll or the average enrollment per call. We tested whether the various recruitment types had similar enrollment rates using chi-squared tests of independence.

Fractional cost

For each of the recruitment types, the ratio of its cost over the total cost of the recruitment efforts is called the fractional cost. Fractional cost quantifies the proportion of the overall budget consumed by a single recruitment type. Hence, fractional cost (FC) is a unit-less number between 0 and 1, i.e. in the interval (0, 1], which measures relative cost of each recruitment type as a fraction of the overall cost of the recruitment.

where Ci is the cost incurred by recruitment type i and n is the number of recruitment types employed.

Fractional enrollment

The ratio of enrollments for an individual recruitment method over the total number of enrollments is called the fractional enrollment. Hence, fractional enrollment is a unit-less number between 0 and 1, i.e. in the interval [0, 1], and is a measurement of the relative frequency that each recruitment type brought to the study. Fractional enrollment (FE) quantifies the contribution that a recruitment type brought to the overall effort. FE also indicates the probability that an enrolled subject was recruited by certain recruitment type.

where Ei is the enrollment resulting from recruitment type ith; and n is number of recruitment type employed in the campaign.

Fractional Enrollment-Cost Ratio

The ratio of the fractional enrollment (FE) over the fractional cost (FC) for each recruitment type indicates its relative performance in terms of benefit versus cost. A ratio of 1 indicates an average type that costs as much as it benefits the campaign while a ratio of greater than one is associated with a better than average, and a lower than one, a lower than average.

Efficacy index

Efficacy is the ability to produce a desired amount of a desired effect.

Contrasting to effectiveness, which is getting things done, efficacy is doing the ‘right’ thing. To help achieve efficiency in our recruitment efforts, one of our statisticians (LN) developed a novel measure we call the efficacy index (EI) to guide the the selection of recruiting venues. The EI is an objective ranking mechanism. The EI is a dynamic measure that takes into account the costs, in dollars, and effectiveness, in terms of enrollments, of each recruitment method, relative to others used in the recruitment campaign.

This EI concept integrates the fractional cost and fractional enrollment, and their ratio, fractional enrollment-cost ratio (FEC ratio), as defined above. Efficacy index (EI) for each recruitment method is defined as the product of its fractional enrollment-cost ratio and its fractional enrollment. Thus, the EI for each recruitment method is calculated using the following formula.

Thus, EI is a non-negative number. As calculated, EI reflects the relative cost effectiveness of the various recruitment approaches that were employed and its fractional contribution to the campaign. A higher EI value indicates a better recruitment method. If a recruitment method has its fractional cost equal to its fractional enrollment, thus having its FEC ratio equal to 1, its EI would have the same value as its fractional enrollment. Hence, for two methods that have the same FEC ratios, the recruitment method that brought a higher number of enrollments would have a higher efficacy index. On the other hand, for two methods that brought in the same number of enrollments, the method that cost less, thus having a higher FEC ratio, would have a higher efficacy index. Thus defined, EI provides a utility to compare the efficacies of the recruitment methods used. The higher the EI values, the more cost effective the method. In this paradigm, the recruitment with its EI equal its FE is an average performer. The recruitment method that has its EI greater than its FE is better than average. Lower than average methods would have their EIs less than their respective FEs. The magnitude of EI is an indicator of its performance. Higher numbers indicate more effectiveness.

Results

The costs of advertising were recorded for each of the six recruitment methods, as seen in Table 1. The total number of callers was 2149 of which 289 enrolled. A small portion (41) of callers mentioned multiple recruitment methods, and were categorized as “multiple sources.” A much larger number of callers (485) could not identify how they were recruited and are categorized as “unknown”.

Table 1.

| Category | #Calls | #Enrolled | Total Costs ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flier | 745 | 120 | 26,848 |

| Mass Transit | 192 | 38 | 19,831 |

| Audio/Video Media | 221 | 30 | 17,513 |

| Newspaper | 234 | 24 | 9,355 |

| Internet | 42 | 11 | 1,010 |

| Referrals | 189 | 43 | 500 |

| Multiple Sources | 41 | 10 | |

| Unknown | 485 | 13 | |

| Total | 2149 | 289 | 75,056 |

Our total cost for recruitment was $75,056. We spent the most money on posting fliers ($26,848), while referral was the least expensive method ($500). Fliers accounted for the most calls (745) and enrollments (120), while the internet accounted for the fewest calls (42) and enrollments (11). All six primary methods contributed to calls and enrollments. Advertisements occurring before a movie theater preview (classified as Audio-Visual media in our analysis) failed to generate any calls or enrollments.

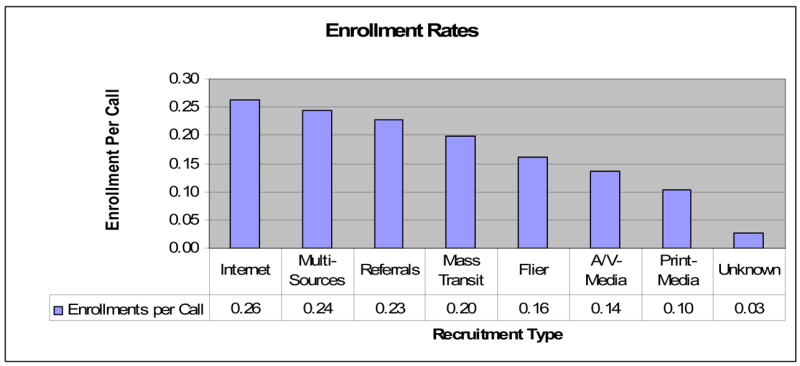

Figure 2 illustrates the different enrollment rates for each recruitment type that we identified. These 8 categories have statistically different enrollment rates (p=0.0001). If we exclude callers in the multiple sources and unknown categories, the remaining categories are still different (p=0.003). Internet methods have the highest enrollment rate (ER) while newspaper advertisements have the lowest.

Figure 2.

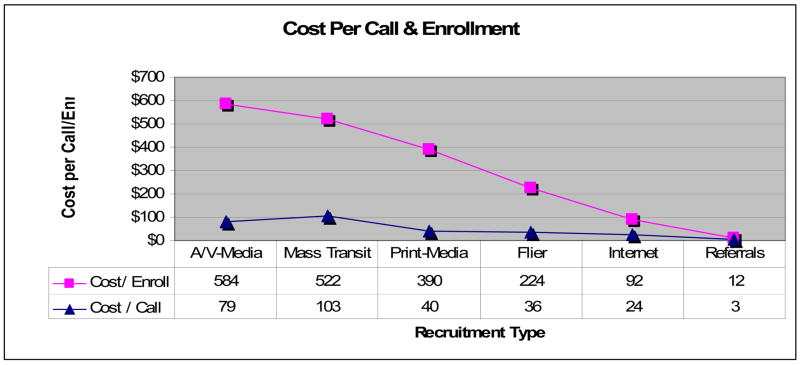

The costs per call and per enrollment for each recruitment method are graphed together in Figure 3. The recruitment types are ordered so that cost per enrollment decreases from left to right. Mass transit advertisements have the highest cost per call, whereas Audio-Visual Media has the highest cost per enrollment. Referrals has both the lowest cost per call and cost per enrollment. Cost per call averaged $46 and cost per enrollment averaged $282.

Figure 3.

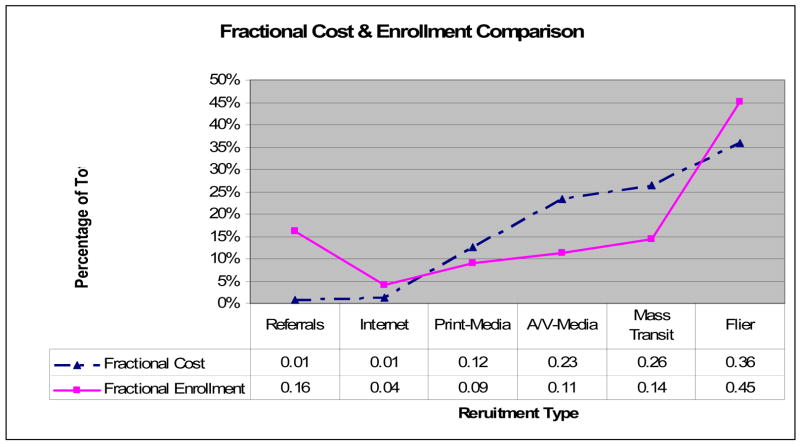

Figure 4 shows the fractional costs and fractional enrollment for each of the methods. Fliers consumed the largest fraction of the recruitment budget, and also made the largest fractional contribution to enrollment. Physician referrals had the lowest fractional cost, but made a substantial contribution to enrollment.

Figure 4.

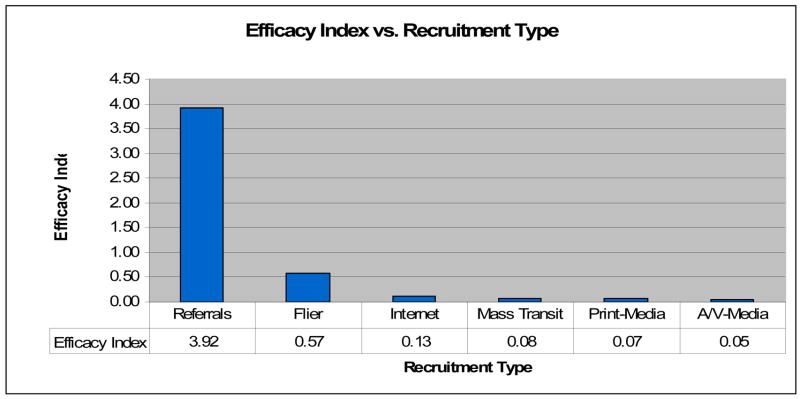

The EI for each recruitment method is shown in Figure 5. By this measure, referrals and fliers were the most efficient methods we employed in our study.

Figure 5.

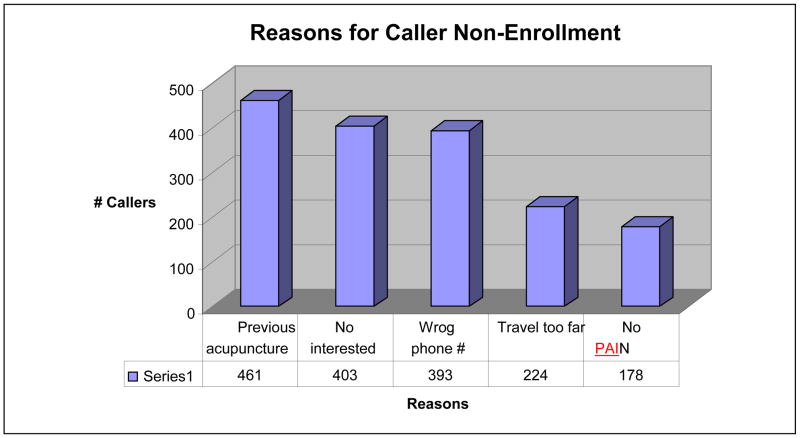

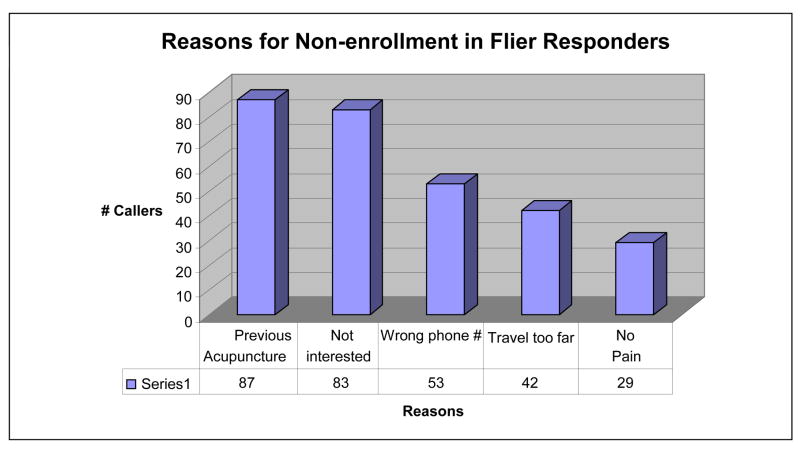

The five main reasons callers cited for not enrolling or not being accepted into the trial were previous acupuncture, no interest, wrong telephone number, travel to distance and no abdominal pain. The exact numbers are shown in Figure 6. As a specfic sub-example, the five main reason callers did not enter who responded from the fliers is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Comparison of enrollment proportions among the recruitment methods was done using Chi-Square test. The p-values of <0.0001 led us to reject the null hypothesis of equal proportions and conclude that the difference in the proportions among different methods was statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

An efficient recruitment method generates many calls and enrollments quickly with minimal effort by the recruitment staff and at a minimal cost. Internet advertising had the highest per call enrollment rate (0.26) while it contributed only 12 subjects (1.3% of total). We speculate that this occurred because a caller had to be actively searching for terms related to clinical trials and/or IBS in order to encounter our advertisements. Also the NIH clinical trials website (clinicaltrials.gov) had a detailed description of the study so that potential subjects could more easily discern eligibility and the ability to participate. If someone is actively seeking information related to their condition, especially novel approaches to treatment, their proactive efforts would likely make them more motivated to call and enroll in a research study. Along the same lines, referrals also had a relatively high enrollment rate (number of enrollments per call) of 0.23. If a potential participant’s physician, friend, family member or coworker actively seeks to inform them of the study, this vetted information bout a research opportunity may increase the individual’s likelihood of calling. In contrast, if a participant cannot remember how they heard about the study, or had study information placed in their hands (e.g. in a newspaper ad), they were less active about seeking study information and may be less likely to enroll. Participants who could not cite a source had the lowest enrollment rate (0.03) and participants recruited via newspaper ads had the second lowest enrollment rate (0.10). In addition, for some people IBS may be a stigma, and so potential participants may be hesitant to write down a phone number in public or pull a tab off of a flier (Figure 1).

Callers who reported multiple sources were responsible for at least 41 calls and 10 enrollments and have the second highest enrollment rate (0.24), demonstrating that potential participants who see ads repeatedly or in multiple modalities are more likely to call. Therefore, it may be more efficient to run multiple recruitment methods concurrently, although it will be more difficult to attribute calls to specific methods. Also, our staff noted that many callers named one source, but commented that they saw different types of ads in multiple locations. Since only a single source was recorded for these calls, this is an indication that synergy may be underestimated in our study. Also, it may be arbitrary how a caller decides which recruitment method informed them of the study (Connett, 1993). Multiple recruitment campaigns may be responsible for piquing the interest of a caller. Also, it might be possible that callers may be more likely to report fliers than other methods which require them to write down the phone number.

When fractional enrollments exceed fractional costs, the resulting efficacy index (EI) indicates better than average strategies. Looking at individual recruitment methods, fractional enrollments are larger than fractional costs for the internet ads, referrals, and fliers while the reverse is true for the newspaper, Audio/Video Media and mass transit ads. The newspaper, Audio/Video Media and mass transit ads, on the other hand, incurred more share of the cost than the share of enrollments that they contributed.

According to EI, referrals were the most efficient recruitment method, because the proportional enrollments far exceeded the proportional costs, resulting in an EI of 3.92. All other methods had smaller gaps between fractional enrollments and fractional costs. The large magnitude of the EI for referrals results from the miniscule cost of referrals ($500) and the large number of enrollments that it effected.

Looking at EI provides a way to compare recruitment methods using a measure that incorporates costs and enrollments; data that can provide feedback and guidance in allocating financial and staff resources. If one is to use a single technique to compare the effectiveness of recruitment methods, EI is the most comprehensive. Without a comprehensive measure, it is difficult to compare the effectiveness of different recruitment methods, because costs are measured in different units than calls or enrollments. For example, referrals had the highest EI (3.92). It would have been hard to glean this information from the majority of statistics already in the literature, such as cost per call, cost per enrollment and enrollment rate, since referrals had the third highest enrollment rate (0.23) and the lowest cost per call (2) and enrollment (11). Efficacy index enables us to combine information we are already collecting into a single measure of effectiveness. This new statistic also enables us to compare the effectiveness of recruitment efforts between studies. It would also allow frequent monitoring of recruitment efforts in future large-scale clinical trials enabling researchers to identify optimal methods and scaling back or eliminating methods that are less effective.

This paper presents several recruitment methods which have only begun to be discussed in the literature, including internet advertising, mass transit advertising and advertising before movie theater previews. Based on our study’s limited approach to internet advertising, our costs were relatively low and consisted primarily of creating and maintaining our one page site. We definitely recommend posting on free websites which have high traffic and exploring low or no cost techniques for increasing web visibility (i.e. paid placements, meta tags). Our findings in this regard support the recent work of other researchers. (Byrom et al. 2004, Harris et al. 2005, West et al. 2006).. (Unfortunately, our website was ineffective in our recruitment campaign because it was extremely difficult to locate without knowing the exact address and its placement within the PIs home institution’s website.)

Movie theatre advertisements were included in the audio-visual category; we spend $1,550 for 15 second ads and received no calls from this venue. Whether this paucity of calls is because the method is generally not efficient (e.g. writing in the darkor attending movies with friends in which the stigma associated with conditions such as IBS make it difficult to copy contact information discreetly)) or reflects unique patterns of IBS patients in unclear.

One important limitation of this study is that calls and enrollment listings that were the result of multiple or unknown sources could not be attributed to a specific method. Thus, it is possible that we overestimated costs/calls and cost/enrollment. Whether this could effect the EI is unclear.

We anticipate that the iterative use of the efficacy index during a recruitment campaign may be helpful in identifying an optimal recruitment strategy in terms of both study cost and subject enrollment.

Conclusion

Understanding what makes recruitment methods effective as both individual approaches and synergistic methods is critical to successful study enrollment In a large RCT of IBS patients, we found that physician referral was the most efficient method because it had the highest EI (3.92) and an enrollment rate of .23. Posting fliers was the second most efficient, with an EI of 0.57 and an enrollment rate of .16. Of the recruitment methods which have a smaller presence in the literature, internet advertising was the most efficient (EI .03) and had the highest overall enrollment rate (.26). Mass transit ads were the least efficient (EI -.12) with the fourth highest overall enrollment rate (.20). Our novel Efficacy Index measure allows a clear comparison between recruitment methods. Despite a large variety of methods and their different effectiveness profiles, all methods, (including synergy between methods) were necessary contributors to our recruitment success.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The research was possible by Grant Numbers 1R01 AT01414-01,1 R21 AT002564-01 and 1K24 AT004095-01 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) at the NIH and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Also, this research was supported in part by grant RR 01032 to the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center General Clinical Research Center from the NIH.

Footnotes

Informed Consent: Permission for this study was given by the Institutional Review Boards of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Works Cited

- Adams J, Silverman M, Musa D, Peele P. Recruiting older adults for clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1997;18:14–26. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(96)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DL. A Guide To Patient Recruitment. CenterWatch/Thomson Healthcare; Boston, Massachusetts, USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bielski RJ, Lydiard RB. Therapeutic trial participants :where do we find them and what does it cost? Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997;33:75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornson-Benson WM, Stibolt TB, Manske BA, Zavela KJ, Youtsey DJ, Buist AS. Monitoring recruitment effectiveness and cost in a clinical trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1993;14:52S–67S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrom B, Stein D, Carey R. [Accessed August 14, 2007];Technology Enhanced Patient Recruitment: A Community Approach. May/June European Pharmaceutical Executive. 2004 www.clinphone.com/files/item66.aspx.

- Conboy LA, Wasserman RH, Jacobson EE, Davis RB, Legedza ATR, Park M, et al. Investigating placebo effects in irritable bowel syndrome: a novel research design. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2006;27:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connett JE, Bjornson-Benson WM, Daniels K. Recruitment of participants in the lung health study, II: assessment of recruiting strategies. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1993;14:38S–51S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberger HE. The e-recruitment of participants for clinical trials. IRB. 2003;25:16–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker L, Wark JD. Recruitment strategies for randomized clinical trials in elderly Australians. Medical Journal of Australia. 1997;167:438–439. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb126657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon JS, Akers L, Severson HH, Danaher BG, Boles SM. Successful participant recruitment strategies for an online smokeless tobacco cessation program. Nicotine and Tobacco Research Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2006 Dec;8(Suppl 1):S35–41. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Lane L, Biaggioni I. Clinical research subject recruitment: the Volunteer for Vanderbilt Research Program. The Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2005 Nov–Dec;12(6):608–13. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1722. www.volunteer.mc.vanderbilt.edu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hungin APS, Chang L, Locke GR, Dennis EH, Barghout V. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacology Therapy. 21:1365–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden H, Reisch L, Hart A, Jr, Harrington M, Nakano C, Jackson JC, Elmore J. Attitudes Toward Participation in Breast Cancer Randomized Clinical Trials in the African American Community. Cancer Nursing. 2007;30(4) doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281732.02738.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstreth, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz S, Henkind SJ. Recruitment for clinical trials on the Web. Healthplan. 2000;24:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer BT, Moreno SI, Pickard AR, Wurst BE, Norden DK, Schumacher HR., Jr A comparison of recruitment methods for an osteoarthritis exercise study. Arthritis Care Research. 1995;8:161–166. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messer KI, Herzog AR, Seng JS, Sampsell CM, Diokno AC, Raghunahan TE, Hines SH. Evaluation of a mass mailing recruitment strategy to obtain a community sample of women for a clinical trial of an incompetence prevention. International Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 2006;38:253–61. doi: 10.1007/s11255-006-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota K, Friedman L, Wesson Ashford J, Hernandez B, Penner A, Stepp A, Raam R, Yesavage J. The Cost-Time Index: A new method for measuring the efficiencies of recruitment-resources in clinical trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2006;27:494–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito YA, Schoenfeld P, Locke GR. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in North America: a systematic review. American J Gastroenterology. 2002;97:1910–1915. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilker B. Guide to clinical trials. New York: Raven Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- West R, Gilsenan A, Coste F, Zhou X, Brouard R, Nonnemaker J, Curry S, Sullivan S. The ATTEMPT cohort: a multi-national longitudinal study of predictors, patterns and consequences of smoking cessation; introduction and evaluation of internet recruitment and data collection methods. Addiction. 2006;101:1352–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]