Abstract

Introduction

There is a significant amount of research demonstrating that the rate of completed suicide among Aboriginal populations is much higher than in the general population. Unfortunately, there is a paucity of research evaluating the risk factors for completed suicide and suicidal behavior in this population. There is an even greater shortage of research on evidence-based interventions for suicidal behaviour.

Method

A literature review was conducted to facilitate the development of an approach to the study of this complex problem.

Results

An approach to developing a research program that informs each step of the process with evidence from the previous steps was developed. The study of risk factors and interventions is described.

Conclusions

Research into the risk factors and evidence-based interventions for Aboriginal suicidal behavior are required. A programmatic approach is described in detail in this paper. It is hoped this informed approach would systematically address this important public health issue that afflicts a significant proportion of the Canadian population.

Keywords: Aboriginal, suicide, research

Résumé

Introduction

Un grand nombre de travaux de recherche attestent que le taux de suicides des autochtones est nettement plus élevé que dans le reste de la population. Malheureusement, peu de travaux évaluent les facteurs de risque et les comportements suicidaires dans cette population. Les programmes d’intervention basés sur les comportements suicidaires sont plus rares encore.

Méthodologie

L’examen de la littérature a permis de développer une approche d’analyse de ce problème complexe.

Résultats

Le programme de recherche mis au point documente chaque étape du processus au moyen de constatations tirées des étapes précédentes et décrit les facteurs de risque et les interventions.

Conclusions

Il est nécessaire d’étudier les facteurs de risque suicidaire et les interventions factuelles chez les autochtones. Cet article présente une approche pragmatique détaillée que les auteurs espèrent voir appliquée systématiquement à l’étude de ce grave problème de santé publique qui touche une grande partie de la population canadienne.

Keywords: aborigène, suicide, santé

Introduction

Among Aboriginal populations there is significant evidence that the rate of completed suicide, especially in youth populations, is much higher than in general population samples (Kirmayer et al, 1998; Malchy et al, 1997; Sigurdson et al, 1994). Suicidal behaviour is an expression of extreme suffering that is best understood as a complex interplay between genetic, psychological, environmental, and community factors (Mann, 2003) that requires a multifaceted approach (Kirmayer, 1994; Kirmayer et al, 1998; Kirmayer et al, 2000). Furthermore, Aboriginal suicidal behaviour has been conceptualized to have multiple layers of determinants, including loss of culture, history of traumatic events, community factors, individual factors, and family factors (Kirmayer, 1994). This paper aims to delineate the approach being taken at the University of Manitoba in developing evidence based culturally sensitive suicide prevention strategies. The program of research outlined in this paper was developed through meetings between multi-disciplinary university-based researchers and First Nations’ community representatives.

Conceptual framework for the programmatic approach

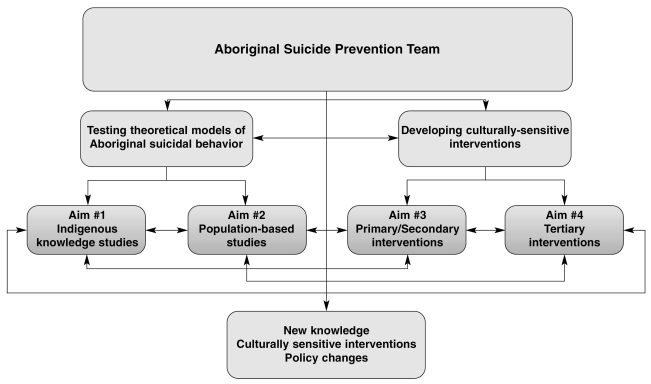

Although the high rate of suicidal behaviour in Aboriginal populations has been well documented, to date, few empirical studies have evaluated risk factors for these behaviours. Additionally, although some efforts have been made to address suicide in Canadian Aboriginal populations, there has been a lack of systematic placement of evidence-based interventions and evaluation of such interventions. The report of the Advisory Group on Suicide Prevention “Acting on What We Know: Preventing Suicide in First Nations” (Health Canada, 2003) suggested a range of recommendations, including research on risk factors for suicidal behaviour, utilizing a broad public health approach to interventions, and working with Aboriginal communities to delineate interventions that are most likely to be successful in specific communities. Based on these recommendations, the current programmatic approach is centered on the development of and ongoing partnership between key personnel – Aboriginal community stakeholders, university-based researchers, and international consultants. This team will conduct research under one conceptual framework (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for the program

Table 1.

Four specific aims that are linked together under one conceptual framework

| Research Theme A. To test theoretical models of Aboriginal suicidal behaviour. |

| Aim #1: To explore Aboriginal perspectives on suicide, suicidal behaviour and suicide prevention. |

| Aim #2: To examine recently collected epidemiologic surveys in Aboriginal populations to empirically test models of suicidal behaviour. |

| Research Theme B. To determine the optimal individual, community, and school-based interventions to reduce suicidal behaviour. |

| Aim #3: To develop primary and secondary suicide prevention strategies that can be implemented and evaluated in the Aboriginal communities to promote mental health and screen for suicidal behaviour. |

| Aim #4: To examine the feasibility of an evidence-based psychosocial intervention for suicidal behaviour for use in Aboriginal communities. |

Research Theme A: To test theoretical models of Aboriginal suicidal behaviour

Suicidal ideation (SI) and suicide attempts (SA) are prevalent in general population samples (11–14%, and 2.8–4.6%, respectively) (Kessler et al, 1999) and are strong risk factors for completed suicide (Suominen et al, 2004; Isometsa & Lonnqvist, 1998). Psychological autopsy studies have demonstrated that a significant proportion of completed suicides occur on the individual’s first SA (Gau & Cheng, 2004; Shaffer et al, 1996). Thus, it is highly important to understand risk factors for suicidal behaviour and intervene prior to the individual making an SA. A well-established risk factor for suicidal behaviour is the presence of mental disorders – especially mood disorders (Gould et al, 1998; Kessler et al, 1999), substance use disorders (Verona et al, 2004) and schizophrenia (Black et al, 1985; Bourgeois et al, 2004; Cohen et al, 1990). Recent evidence suggests that anxiety disorders (especially posttraumatic stress disorder [Sareen et al, 2005a; Sareen et al, 2005b]) exposure to traumatic life events (Belik et al, in press; Enns et al, 2006), and particular personality traits (Cox et al, 2004) are independently associated with suicidal behaviour.

Although a number of risk factors found to be important in non-Aboriginal populations are likely to be important in Aboriginal populations, findings from non-Aboriginal populations may not be generalizable to Aboriginal populations. Previous studies have demonstrated that Aboriginal individuals who completed suicide were younger and had a higher mean level of alcohol at the time of the suicide compared to non-Aboriginal individuals (Karmali et al, 2005). As mentioned previously, the experience of a traumatic event has been demonstrated to be associated with suicidal behaviour (Belik et al, in press; Bruce et al, 2001); it is important to note that there are also higher rates of exposure to trauma in Aboriginal populations compared to non-Aboriginal populations (Kirmayer, 1994; Manson et al, 2005).

Kirmayer (Kirmayer, 1994; Kirmayer et al, 1998; Kirmayer et al, 2000) has presented reviews of the literature on risk factors of suicide in Aboriginal populations. There are a number of specific issues that are especially relevant in Aboriginal suicides, which include physical and social environment factors (e.g., isolated rural communities, high latitude communities), cultural factors (historical factors, acculturation issues), childhood adversity (experience of childhood trauma, single parent families), poverty, and social disorganization (Kessler et al, 1998a; Kessler et al, 1998b; Bourke, 2003). Although the theorized models suggest a complex interplay between individual, family, cultural and community factors involved in Aboriginal suicidal behaviour, we were unable to find any empirical evaluations of these models. Finally, it has been demonstrated that the majority of individuals with suicidal behaviour or who complete suicide in the general community have a mental disorder (Ernst et al, 2004; Arsenault et al, 2004). To date, there are no systematic evaluations of the presence of psychopathology among Aboriginal people with suicidal behaviour. A key recommendation from the report of the Advisory Group on First Nation’s Suicide Prevention (Health Canada, 2003) was a comprehensive understanding of risk factors for suicidal behaviour in Aboriginal populations.

It is well accepted that a complex interplay between individual, family, and community factors plays a role in the development of Aboriginal suicidal behaviour (Kirmayer, 1994). Recent evidence from Chandler et al.’s (2006 (1998) work suggests that there are wide differences in rates of suicide across different Aboriginal communities in British Columbia (Chandler et al, 2003). Most interestingly, Chandler and Lalonde (1998) demonstrated that various community level factors were associated with rates of suicidal behaviour. Therefore, we can conclude that each Aboriginal community deals with different social, environmental and individual factors that may contribute to suicidal behaviour in their particular community resulting in a differing rate of suicide in each community. In order to develop an effective and specific community-level intervention, it is important to understand these critical issues in the communities of interest.

In this approach, specific models utilizing both qualitative and quantitative analytic approaches are applied. First, theoretical models utilizing a qualitative approach within the Aboriginal communities are evaluated. Second, the work from the communities will guide epidemiologic research in population-based studies. Finally, this approach utilizes a large population-based U.S. survey to delineate whether these models are generalizable to other Aboriginal communities.

Aim #1: To explore Aboriginal perspectives on suicide, suicidal behaviour and suicide prevention

Aboriginal communities and community members have been dealing with the problem of youth suicide for several decades. In order to develop new models of understanding and preventing suicide, these models need to be grounded in indigenous concepts and approaches. A qualitative investigation of indigenous perspectives on suicide, suicidal behaviour and suicide prevention would facilitate a research-based understanding of these problems. The investigation involves key informant interviews, focus groups, and field observation. A critical ethnographic approach would be used to situate individual and family experiences within the context of their everyday lives. This approach would be supplemented with an institutional ethnographic approach in order to critically situate these experiences within the wider social, historical, economic, cultural and political context.

Aim #1 will enhance the indigenous knowledge base related to suicide and suicide prevention by identifying existing strengths in the communities with the aim of further developing or building on these strengths. The knowledge gained from these interviews will lead to refined models of suicidal behaviour that will be tested in large population-based epidemiologic studies. Furthermore, the themes and knowledge that come from these qualitative investigations will inform the design of public health interventions at both universal and targeted levels.

Aim #2: To examine recently collected epidemiologic surveys in Aboriginal populations to empirically test models of suicidal behaviour

Aim #2A: To examine the correlates of suicide attempts in the Manitoba First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey (MFNRLHS)

The Manitoba First Nations Regional Longitudinal Health Survey-Youth sample (MFNRLHS-Y) is a comprehensive, population-based survey that examines social and cultural dimensions of health. It identifies specific health issues, protective factors, and intervention points at various stages of the life course. The survey included measures on suicide risk, substance abuse, and protective measures derived from internationally validated resilience studies addressing individual and communal forms of resilience (Beals et al, 2005; Manson et al, 2005). The survey also included questions on a recent experience of trauma (physical, sexual or verbal abuse), injuries related to trauma, and various forms of trauma experienced which caused a great deal of worry or unhappiness (death of a significant other, family discord, domestic violence, family alcoholism or mental health disorders, peer or relationship problems, residential dislocation, and personal or family health problems).

The impact of traumatic events, family dysfunction, exposure to suicide in the community, and substance abuse in relation to suicide attempts would be tested. Also, whether peer-relationships, adherence to cultural practices, or spirituality mediate the relationship between traumatic events and suicidal behaviour. To the best of our knowledge, this would be the first empirical examination using the only population-based dataset in Canada that documents more fully the risk and protective factors related to suicide attempts in FN youth. Findings and knowledge from Aim #1 (qualitative studies) will directly input into the design and implementation of research questions in the MFNRLHS-Y. Furthermore, the findings of the current aim will directly impact upon the types of interventions that are considered optimal (Aims #3 and #4).

Aim #2B: To examine the correlates of suicide attempts in the American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP)

The limitation of the Manitoba youth survey (MFNRLHS-Y) is that a detailed, structured examination of mental disorders was not conducted. This limitation holds true across Canada. To date, there has not been a detailed evaluation of mental disorders in a population-based sample of Canadian Aboriginals. Beals and Manson have adapted the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler et al, 1994) to be culturally sensitive to Aboriginal populations and conducted the first standardized, detailed mental health survey of two American Indian tribes (Beals et al, 2005; Manson et al, 2005; Norton & Manson, 1996).

The American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) is a cross-sectional survey of two American Indian reservation populations (Northern Plains tribe and a Southwestern tribe) (Beals et al, 2005). Preliminary studies examining suicidal behaviour in the AI-SUPERPFP have been published recently (Lemaster et al, 2004; Garroutte et al, 2003). To date, complex models of understanding suicidal behaviour in this dataset have not been conducted. Findings and knowledge from Aim #1 (qualitative studies), and Aim #2A will directly input into the design and implementation of research questions in the AI-SUPERPFP. Furthermore, the findings of the current aim will directly impact upon the types of interventions that are considered optimal (Aims #3 and #4).

Research Theme B: To determine the optimal individual, community, and school-based interventions to reduce suicidal behaviour

Suicide Prevention Strategies

A systematic review of suicide prevention strategies has been recently published (Mann et al, 2005). Also, as recommended by the Advisory Group on Suicide Prevention in Canada (Health Canada, 2003), suicide prevention strategies are best conceptualized as a community wellness strategy promoting whole person health (physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual) (Kirmayer et al, 2003). Recent evidence from a U.S. American Indian community provided initial evidence to support this suggestion (May et al, 2005). A community-based approach was utilized with all levels of public health intervention (primary, secondary, and tertiary), which led to a reduction in suicidal behaviour (particularly suicide attempts) in the community over a long time period (May et al, 2005). A range of community-level suicide prevention strategies has been recommended with differing levels of empirical support (Health Canada, 2003; May et al, 2005).

Primary level prevention strategies have included general health promotion programs and suicide awareness programs across the community to improve the mental, physical, spiritual, and cultural well-being of individuals (May et al, 2005). School-based curricula in health promotion, recreational and sports programs, cultural programs, family life education and parenting skills workshops would be included (Gould et al, 2003). Suicide awareness campaigns have also been suggested to make community members aware of suicide and methods of gaining appropriate treatment.

Secondary level suicide prevention strategies are based on the rationale that most individuals (especially adolescents) with suicidal ideation are not appropriately recognized by health professionals. Gatekeeper training of school personnel (Gould et al, 2003; King et al, 2000), community members (Capp et al, 2001) and teachers to identify and help facilitate access to treatment for suicidal individuals is based on evidence that suicidal individuals (especially youth) are under-recognized and have a tendency to negate help (Deane et al, 2001). Screening programs to identify suicidal individuals have also been considered. There has been specific interest in school-wide screening programs to detect youth with depression and suicidal behaviour (Gould & Kramer, 2001). Evaluations of youth screening programs have been demonstrated to have moderate to high sensitivity (83%–100%) with moderate specificity (51%–76%) (Gould et al, 2003). Recent evidence from Gould’s group has demonstrated that school-based screening of suicidal ideation does not iatrogenically increase the risk of suicidal ideation (Gould et al, 2005).

Post-suicide interventions are based on the rationale that a timely response to suicide is likely to reduce subsequent morbidity, mortality and suicidality, especially in youth (Thompson et al, 2001). The evidence for efficacy of postvention strategies is sparse. The Centre for Disease Control has developed specific guidelines for response to prevent cluster suicides (O’Carroll et al, 1988), which have been documented in adolescent samples (Gould et al, 1990; Hazell, 1993) and in Aboriginal youth (Wilkie et al, 1998).

Tertiary level intervention for suicidal behaviour has been a controversial and difficult issue. There are no randomized controlled trials evaluating treatment of suicidal Aboriginal youth. In fact, there is a paucity of studies evaluating treatment of any suicidal youth (Gould et al, 2003). Over the last decade, a new psychological treatment, Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), has been demonstrated to be efficacious in reducing suicidal behaviour in adults. This exciting and important new therapy is a theoretically grounded and empirically supported psychotherapy originally developed by Linehan (1991, 1993) for chronically parasuicidal women with borderline personality disorder (BPD). DBT integrates traditional cognitive-behavioural psychotherapeutic approaches with Eastern philosophy and meditation practices and shares elements with psychodynamic, client-centered, Gestalt, paradoxical and strategic approaches (Koerner et al, 1998). There is now empirical data supporting use of DBT with chronically parasuicidal women with BPD in both inpatient (Bohus et al, 2004) and outpatient settings (Linehan et al, 1991; Linehan et al, 2006; Verheul et al, 2003; Koons et al, 2001). As well, DBT has been modified for use with patients with substance abuse (Linehan et al, 1999; Linehan et al, 2002). Recently, Katz has demonstrated the feasibility of utilizing DBT with an adolescent inpatient sample, which included Aboriginal youth (25% of the DBT group). The Aboriginal youth responded to the treatment with the same outcomes as non-Aboriginal youth (Katz et al, 2004). DBT has also been applied in adolescent outpatients (Miller, 1999, Miller et al, 1997, Rathus & Miller, 2002) and geriatric populations (Lynch et al, 2003).

DBT for parasuicidal adolescents utilizes an expanded application of DBT, modified from treatment of patients with BPD to parasuicidal adolescents with or without BPD (Katz et al, 2002, Katz & Cox, 2002). Although it is expanded in terms of inclusion criteria the treatment for adolescents is a condensed model of the original treatment. For outpatients, it consists of sixteen weeks of combined individual and group sessions that occur on a weekly basis. For inpatients it is condensed to a two week model. Adolescents are taught behavioral skills to cope with the circumstances in their lives while at the same time are validated for the difficulty of their situation. Therapists utilize various commitment and cognitive-behavioral strategies to assist in keeping the adolescents in treatment while coping with the challenges they face. Support for the treatment team throughout this process is an integral part of the treatment. DBT for adolescents has been applied to multiple cultural groups on a clinical basis. Whether it will require adaptation for application to Aboriginal communities is an empirical question. Thus far, in its clinical application to inpatient Aboriginal youth, DBT has sufficient flexibility to allow application as evidenced by the data from Katz et al (2004). The reader is referred elsewhere for a thorough review of DBT for parasuicidal adolescents (Katz et al, 2002; Miller et al, 2006).

Aim #3: To develop primary and secondary suicide prevention strategies that can be implemented and evaluated in Aboriginal communities to promote mental health and screen for suicidal behaviour

It is evident that several community-level suicide prevention strategies have been described with various levels of evidence. It is important to individualize these community-level, intervention-based strategies to the needs of the specific communities, as well as based on the evidence and feasibility of particular strategies. The approach of the program will be to delineate the specific strategies that are needed in the Aboriginal communities and then design evaluation studies. Among the interventions mentioned above, the focus is placed on development of mental health promotion curricula that teach adolescents strategies to cope with life stress.

Information used for this aim would be specifically delineated in the indigenous knowledge qualitative studies conducted in Aim #1. The program could pilot test gatekeeper training of school personnel, youth peers, and community members. Furthermore, feasibility and pilot testing of school-wide and primary care screening programs for depression and suicide could be included. Each screening program would first be examined and adapted to be culturally sensitive. For example, school-based mental health promotion curricula could be adapted to ensure that there is significant emphasis on traditional community values. Gatekeeper training programs could similarly be adapted from previous ones utilized in Australian Aboriginal populations (Capp et al, 2001). The program would assess each of the proposed programs related to their acceptability, sustainability, and capacity to integrate into existing organizational or community structures.

Knowledge gained from the first two aims will be important in delineating the interventions that are most likely to be acceptable. Furthermore, the first two aims will delineate those individuals that are at highest risk for committing suicide. Thus, the intervention programs will aim to utilize this knowledge and directly point to interventions that target the individuals at highest risk for suicidal behaviour.

Aim #4: To examine the feasibility of an evidence-based psychosocial intervention for suicidal behaviour for use in Aboriginal communities

The program will bring together researchers and members of the community to be able to adapt the DBT intervention to be culturally sensitive, yet retain all of the core characteristics of DBT. The program will evaluate whether mental health care providers working in Aboriginal communities can be trained to a level of adherence to be able to deliver DBT.

Each section of the DBT training manual will be analyzed to delineate the changes required to DBT that will make it culturally sensitive. Next, a pilot study could be conducted that will train mental health providers working specifically in the Aboriginal communities in the culturally adapted DBT and will evaluate whether the therapists can be adherent to DBT principles in treatment (using standard fidelity measures). This pilot study will help further refine methods and form the basis for a randomized controlled trial for testing the culturally adapted DBT in Aboriginal communities.

The current aim will clearly be linked to previous aims. Screening programs and gatekeeper training programs will help identify individuals who are suicidal. These individuals will then be offered the opportunity to be involved in the culturally adapted psychological intervention.

Conclusions

The current program of research addresses a serious multi-faceted public health problem –suicidal behaviour in Aboriginal populations. It utilizes a systematic approach that furthers the understanding of risk factors and intervention needs of particular communities. Within one conceptual framework, the current proposal includes a step-by-step line of inquiry that will ultimately lead to increased knowledge of the types of culturally sensitive suicide prevention strategies required in Aboriginal communities.

Acknowledgments

CIHR New Investigator awards to Drs. Sareen and Elias, a Canada Research Chair award to Dr. Brian J. Cox support this research and a CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship –Master’s Award to Shay-Lee Belik. The authors thank Garry Munro, Frank Deane, Jan Beals, Madelyn Gould, Murray Stein, Alec Miller, Catherine Cook, Rachel Eni, Tracie Afifi, Jina Pagura & Ian Clara for their thoughtful contributions to this work.

References

- Arsenault-Lapierre G, Kim C, Turecki G. Psychiatric diagnoses in 3275 suicides: A meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, Mitchell CM. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(1):99–108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belik SL, Cox BJ, Stein MB, Asmundson GJG, Sareen J. Traumatic events and suicidal behavior: Results from a national mental health survey. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0b013e318060a869. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Winokur G, Warrack G. Suicide in schizophrenia: The Iowa Record Linkage Study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1985;46(11 Pt 2):14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohus M, Haaf B, Simms T, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient dialectical behavioral therapy for borderline personality disorder: A controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42(5):487–99. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois M, Swendsen J, Young F, et al. Awareness of disorder and suicide risk in the treatment of schizophrenia: Results of the international suicide prevention trial. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1494–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourke L. Toward understanding youth suicide in an Australian rural community. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57(12):2355–65. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce SE, Weisberg RB, Dolan RT, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care patients. Primary Care Companion Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;3(5):211–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capp K, Deane FP, Lambert G. Suicide prevention in Aboriginal communities: Application of community gatekeeper training. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2001;25(4):315–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde C. Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1998;35(2):191–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE, Sokol BW, Hallett D. Personal persistence, identity development, and suicide: A study of Native and Non-native North American adolescents. Monographs of Social Research in Child Development. 2003;68(2):vii–viii. 1. doi: 10.1111/1540-5834.00246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M, Proulx T. Changing selves in changing worlds: Youth suicide on the fault-lines of colliding cultures. Archives of Suicide Research. 2006;10(2):125–40. doi: 10.1080/13811110600556707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LJ, Test MA, Brown RL. Suicide and schizophrenia: data from a prospective community treatment study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147(5):602–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Enns MW, Clara IP. Psychological dimensions associated with suicidal ideation and attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2004;34(3):209–19. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.3.209.42781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane FP, Wilson CJ, Ciarrochi J. Suicidal ideation and help-negation: Not just hopelessness or prior help. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57(7):901–14. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enns MW, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, ten Have M, Sareen J. Childhood adversities and risk for suicidal ideation and attempts: A longitudinal population-based study. Psychological Medicine. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008646. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst C, Lalovic A, Lesage A, Seguin M, Tousignant M, Turecki G. Suicide and no axis I psychopathology. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte EM, Goldberg J, Beals J, Herrell R, Manson SM. Spirituality and attempted suicide among American Indians. Social Science Medicine. 2003;56(7):1571–9. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SS, Cheng AT. Mental illness and accidental death: Case-control psychological autopsy study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;185:422–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.5.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, Shaffer D. Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(4):386–405. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046821.95464.CF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, et al. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(9):915–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Kramer RA. Youth suicide prevention. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2001;31(Suppl):6–31. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.5.6.24219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Kleinman M, et al. Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening programs: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293(13):1635–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, Wallenstein S, Kleinman M. Time-space clustering of teenage suicide. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1990;131(1):71–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell P. Adolescent suicide clusters: Evidence, mechanisms and prevention. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;27(4):653–65. doi: 10.3109/00048679309075828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Acting on what we know: Preventing youth suicide in First Nations. Ottawa: Advisory Group on Suicide Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Isometsa E, Lonnqvist J. Suicide attempts preceding completed suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;173:531–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.6.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali S, Laupland K, Harrop AR, et al. Epidemiology of severe trauma among status Aboriginal Canadians: A population-based study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2005;172(8):1007–11. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LY, Cox BJ. Dialectical behavior therapy for suicidal adolescent inpatients: A case study. Clinical Case Studies. 2002;1:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Katz LY, Cox BJ, Gunasekara S, Miller AL. Feasibility of dialectical behavior therapy for suicidal adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(3):276–82. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LY, Gunasekara S, Miller AL Adolescent Psychiatry: the Annals of the American Society for Adolescent Psychiatry ed. Dialectical behavior therapy for inpatient and outpatient parasuicidal adolescents. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen H. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998a;7:171–85. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):617–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Wittchen H-U, Abelson JM, et al. Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998b;7(1):33–55. [Google Scholar]

- King KA, Smith J. Project SOAR: a training program to increase school counselors’ knowledge and confidence regarding suicide prevention and intervention. Journal of School Health. 2000;70:402–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ. Suicide among Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review. 1994;31(1):3–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Boothroyd LJ, Hodgins S. Attempted suicide among Inuit youth: Psychosocial correlates and implications for prevention. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;43(8):816–22. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Brass GM, Tait CL. The mental health of Aboriginal peoples: Transformations of identity and community. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;45(7):607–16. doi: 10.1177/070674370004500702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Simpson C, Cargo M. Healing traditions: Culture, community and mental health promotion with Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Australas Psychiatry. 2003;11(Suppl1):S15–S23. [Google Scholar]

- Koerner K, Miller AL, Wagner AW. Dialectical behavior therapy: part I. Principle-based intervention for patients with multiple problems. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health. 1998;4:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Therapy. 2001;32:371–90. [Google Scholar]

- LeMaster PL, Beals J, Novins DK, Manson SM. The prevalence of suicidal behaviors among Northern Plains American Indians. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2004;34(3):242–54. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.3.242.42780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48(12):1060–4. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy versus treatment by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–66. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;67:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Schmidt H, Dimeff LA, Craft JC, Kanter J, Comtois KA. Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug dependence. American Journal of Addictions. 1999;8:279–92. doi: 10.1080/105504999305686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Morse JQ, Mendelson T, Robins CJ. Dialectical behavior therapy for depressed older adults: A randomized pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchy B, Enns MW, Young TK, Cox BJ. Suicide among Manitoba’s Aboriginal people, 1988 to 1994. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1997;156(8):1133–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ. Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4:819–28. doi: 10.1038/nrn1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294(16):2064–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD. Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(5):851–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Serna P, Hurt L, DeBruyn LM. Outcome evaluation of a public health approach to suicide prevention in an American Indian tribal nation. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1238–44. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL. Dialectical behavior therapy: A new treatment approach for suicidal adolescents. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1999;53(3):413–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1999.53.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM. Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Suicidal Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Rathus JH, Linehan MM, Wetzler S, Leigh E. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health. 1997;3:78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Norton IM, Manson SM. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Navigating the cultural universe of values and process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):856–60. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Carroll PW, Mercy JA, Steward JA. CDC recommendations for a community plan for the prevention and containment of suicide clusters. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 1988;37:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathus JH, Miller AL. Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 2002;32(2):146–57. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.146.24399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Houlahan T, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJG. Anxiety disorders associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders. 2005a;193(7):450–4. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000168263.89652.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: A population-based longitudinal study of adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005b;62:1249–57. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Fisher P, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis in child and adolescent suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(4):339–48. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830040075012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdson E, Staley D, Matas M, Hildahl K, Squair K. A five-year review of youth suicide in Manitoba. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;39(8):397–403. doi: 10.1177/070674379403900808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suominen K, Isometsa E, Suokas J, Haukka J, Achte K, Lonnqvist J. Completed suicide after a suicide attempt: a 37-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:562–563. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EA, Eggert LL, Randell BP, Pike KC. Evaluation of indicated suicide risk prevention approaches for potential high school dropouts. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(5):742–52. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, Van Den Bosch LM, Koeter MW, De Ridder MA, Stijnen T, van den Brink W. Dialectical behavior therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in The Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:135–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verona E, Sachs-Ericsson N, Joiner TE., Jr Suicide attempts associated with externalizing psychopathology in an epidemiological sample. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):444–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie C, Macdonald S, Hildahl K. Community case study: Suicide cluster in a small Manitoba community. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;43(8):823–8. doi: 10.1177/070674379804300807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]