Abstract

The delivery of the diphtheria toxin catalytic domain (DTA) from acidified endosomes into the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells requires protein–protein interactions between the toxin and a cytosolic translocation factor (CTF) complex. A conserved peptide motif, T1, within the DT transmembrane helix 1 mediates these interactions. Because the T1 motif is also present in the N-terminal segments of lethal factor (LF) and edema factor (EF) in anthrax toxin, we asked whether LF entry into the cell might also be facilitated by target cell cytosolic proteins. In this study, we have used LFnDTA and its associated ADP-ribosyltransferase activity (DTA) to determine the requirements for LF translocation from the lumen of endosomal vesicles to the external medium in vitro. Although low-level release of LFnDTA from enriched endosomal vesicles occurs in the absence of added factors, translocation was enhanced by the addition of cytosolic proteins and ATP to the reaction mixture. We show by GST-LFn pull-down assays that LFn specifically interacts with at least ζ-COP and β-COP of the COPI coatomer complex. Immunodepletion of COPI coatomer complex and associated proteins from cytosolic extracts blocks in vitro LFnDTA translocation. Translocation may be reconstituted by the addition of partially purified bovine COPI to the translocation assay mixture. Taken together, these data suggest that the delivery of LF to the cytosol requires either COPI coatomer complex or a COPI subcomplex for translocation from the endosomal lumen. This facilitated delivery appears to use a mechanism that is analogous to that of DT entry.

Keywords: diphtheria toxin, anthrax toxin

Receptor-mediated endocytosis of many bacterial protein toxins ensures their passage through an acidified endosomal compartment. Diphtheria toxin (DT), anthrax toxin (AT), and the botulinum neurotoxins all require exposure to a low-pH environment for the delivery of their respective catalytic domains to the cytosol (1–3). In the case of DT, exposure to a low-pH environment is known to trigger a dynamic change in the transmembrane domain resulting in its spontaneous insertion into the vesicle membrane and the formation of a pore or channel (1). Ratts et al. (4) have demonstrated that the in vitro translocation of the DT catalytic domain from the lumen of partially purified endosomal vesicles through this pore to the external milieu requires the addition of ATP and a cytosolic translocation factor (CTF) complex to the in vitro translocation assay mixture (4). Although the CTF complex has not been fully characterized, several components including Hsp90, thioredoxin reductase, and β-COP from the COPI coatomer complex have been shown to be essential components in the catalytic domain delivery process (4–6).

Subsequently, Ratts et al. (5) described a putative translocation motif, T1, in DT transmembrane helix 1, which is conserved in anthrax lethal factor (LF), edema factor (EF), and botulinum neurotoxins A, C1, and D (5). Because the L221E mutation in the T1 motif in the diphtheria toxin-related fusion protein toxin DAB389IL-2 results in a nontoxic translocation-deficient phenotype (5, 7) and an interaction between this region of the transmembrane domain and β-COP was demonstrated by pull-down experiments (5), it has been hypothesized that this region of the DT transmembrane helix 1 domain plays an essential role in the delivery process.

Because β-COP and possibly other COPI coatomer complex-associated proteins are required for DT catalytic domain translocation and the T1 motif is conserved in the N-terminal portion of LF (5), we reasoned that these sequences might mediate an interaction with COPI coatomer complex protein(s) and thereby facilitate the entry of AT into the target cell cytosol. To test this hypothesis, we used the fusion protein LFnDTA (8) in a series of in vitro translocation assays. In these studies, in vitro translocation and release of LFnDTA from toxin-preloaded and purified endosomal vesicles was monitored by measuring its ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. We demonstrate that the translocation and release of LFnDTA from the lumen of acidified endosomal vesicles to the external milieu is enhanced by the addition of both ATP and crude cytosolic extracts to the translocation assay mixture. Immunodepletion of COPI coatomer complex proteins from these extracts resulted in a marked reduction of in vitro translocation and release of LFnDTA. In addition, pull-down experiments in which GST-LFn was used as bait resulted in the identification of T1 motif-mediated interactions with COPI coatomer complex proteins. The results presented in this article support the hypothesis that anthrax LF delivery to the cytosol is enhanced and facilitated by COPI coatomer complex proteins.

Results

In vitro translocation of LFnDTA from enriched endosomal vesicles is enhanced by cytosolic proteins. LFnDTA is a fusion protein composed of the N-terminal 254-aa segment of LF, which is genetically fused to the DT catalytic domain (DTA) (8). To enter susceptible eukaryotic cells LFnDTA requires protective antigen (PA) for receptor-mediated internalization and compartmentalization into and through an acidified endosomal compartment (9, 10). Endosomal vesicles were preloaded with toxin by exposing HUT102/6TG cells to 10 nM each of PA63 and LFnDTA in the presence of 1 μM Bafilomycin A1. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation and lysed in the presence of 1 μM Bafilomycin A1, and endosomal vesicles were purified by discontinuous sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation as previously described (4–6, 11).

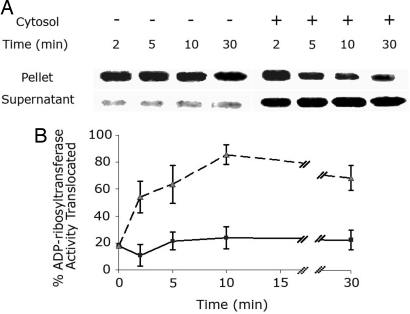

The localization of the ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of LFnDTA to either the vesicle-free supernatant fluid or pellet fraction after in vitro translocation reactions using these toxin-preloaded endosomes provides a sensitive method to determine the relative requirement for host cell cytosolic factors in the translocation process. Fig. 1 A and B shows the time course of LFnDTA translocation and release from enriched endosomal vesicles in the presence and absence of cytosolic extracts and ATP. After the removal of Bafilomycin A1 and the addition of 5 mM ATP to the assay mixture, the level of LFnDTA translocation from enriched endosomal vesicles was found to be 15 ± 5% of the total ADP-ribosyltransferase activity after a 30-min incubation period. In marked contrast, addition of HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts to the reaction mixture greatly enhanced the translocation of LFnDTA from the vesicle lumen, typically amounting to 80 ± 10% of total vesicle-associated enzymatic activity. Total vesicle-associated ADP-ribosyltransferase activity is defined by the phosphorimage signal obtained from the AD[32P]-ribosylation of elongation factor 2 after Triton X-100 lysis of 5 μl of toxin-preloaded endosomes. Because maximal LFnDTA translocation occurred within 10 min, this incubation period was used in all subsequent translocation assays.

Fig. 1.

Time course of LFnDTA translocation from partially purified endosomal vesicles in vitro in either the presence of ATP alone or the presence of ATP and HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts. (A) ADP-ribosyltransferase activity in both the high-speed pellet and supernatant fractions after in vitro translocation of LFnDTA from purified endosomal vesicles. After in vitro translocation reactions, endosomal vesicles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation, and both the lysed pellet and supernatant fluid fraction were assayed for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity by measuring the incorporation of [32P]-NAD+ into AD[32P]ribosyl-EF2 after 7% SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Time course of in vitro translocation of LFnDTA from the lumen of partially purified endosomal vesicles to the external medium. The pellet and supernatant fluid fractions for each time point were assayed for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity, and the autoradiographic signals were measured by densitometry. The sum of the densitometry units from each pair of supernatant fluid and pellet fraction is plotted as the percentage of activity in supernatant fluid at that time point (n = 3; error bar denotes SD). Results are presented as the percent total ADP-ribosyltransferase translocated in the presence of 5 mM ATP alone (squares) or in the presence of 5 mM ATP and 8 μg of cytosolic extracts (triangles).

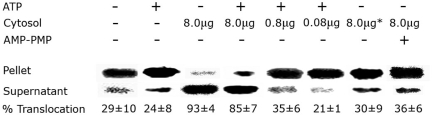

Fig. 2 shows the relative contribution of added ATP and cytosolic extracts to LFnDTA translocation and release from endosomal vesicles in vitro. The addition of translocation buffer alone, or translocation buffer supplemented with 5 mM ATP, to the reaction mixture resulted in release of ≈25% of the total vesicular ADP-ribosyltransferase activity into the supernatant fluid fraction. In contrast, the addition of increasing amounts of HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts markedly stimulated LFnDTA translocation and release in a dose-dependent manner. Because the addition of boiled cytosolic extracts to the assay mixture failed to stimulate in vitro translocation above control levels, we conclude that one or more eukaryotic cytosolic protein(s) are necessary for optimal LFnDTA translocation and release into the external medium. Importantly, in the absence of added ATP, we have found that the addition of the nonhydrolyzable ATP analog AMP-PNP to the translocation assay mixture markedly inhibits the translocation and release of LFnDTA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The in vitro translocation of LFnDTA from endosomal vesicles requires both cytosolic proteins and ATP. Vesicles loaded with 10 nM LFnDTA/PA63 were incubated in translocation buffer with or without 5 mM ATP or AMP-PNP and HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts as indicated for 10 min at 37°C. After in vitro translocation reactions, endosomal vesicles were processed and both the lysed pellet and supernatant fractions were assayed for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity as described in Fig. 1. Percent translocation of LFnDTA ADP-ribosylation activity from the pellet to the supernatant fraction was calculated by densitometric analysis of AD[32P]-ribose-EF2 autoradiographs. Results are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). * indicates heat-inactivated cytosol.

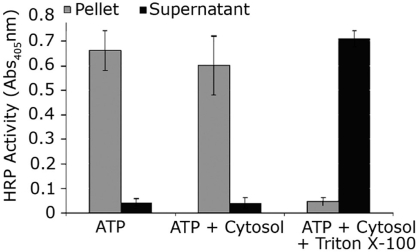

To address the possibility that translocation assay conditions might lead to endosomal lysis, we coloaded vesicles with both LFnDTA/PA63 and HRP in the presence of Bafilomycin A1. After cell lysis and partial purification of endosomal vesicles, vesicle integrity was monitored by measuring both ADP-ribosyltransferase and HRP activity in the supernatant fluid and pellet fractions after in vitro translocation assays. The addition of ATP and cytosolic extracts to the assay mixture resulted in release of >80% of the total ADP-ribosyltransferase activity into the high-speed supernatant fraction, whereas, under these conditions, >90% of the HRP activity remained associated with the pellet fraction (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Translocation of LFnDTA from vesicles is not a result of spontaneous lysis. The endosomal vesicle compartment in HUT102/6TG cells was preloaded with 10 nM LFnDTA/PA63 and 5 mg/ml HRP in the presences of Bafilomycin A1. Endosomal vesicles were partially purified as described, and translocation reactions were performed as described in Fig. 1. After in vitro translocation, endosomal vesicles were pelleted by ultracentrifugation and HRP activity was measured in both the lysed pellet and supernatant fluid fractions by using Super Aqua Blue ELISA substrate (eBioscience). HRP activity was measured as absorbance at the wavelength of 405 nm according to the manufacturer's instructions. (n = 3; error bars denote SD).

To obtain qualitative information about the toxin-preloaded vesicles used in these translocation assays, we examined their morphology by transmission electron microscopy and partially characterized vesicular and vesicle-associated proteins by SDS/PAGE and immunoblot analysis [see supporting information (SI) Figs. S1 and S2]. Representative micrographs indicate that the endosomal vesicles have the following size distribution: 50–75 nm (≈21%), 75–100 nm (≈71%), and 100–140 nm (≈8%) in diameter (Fig. S1). This size distribution of endocytic vesicles is consistent with earlier observations (12). Partial characterization of vesicle surface determinants after SDS/PAGE and immunoblot analysis demonstrated the presence of the small GTPases Rab5 and Rab7 and early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1), but not the lysosomal marker LAMP-1 (Fig. S2).

GST-LFn Specifically Interacts with Components of the COPI Coatomer Complex.

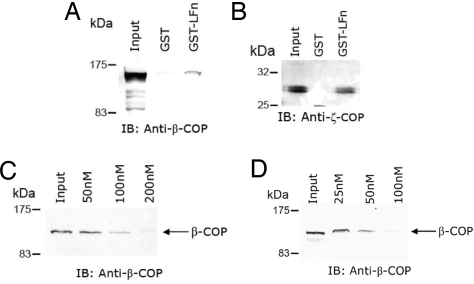

Ratts et al. (5) demonstrated that the region in transmembrane helix 1 that carries the T1 motif plays an essential role in the translocation of the DT catalytic domain from the lumen of endosomal vesicles to the external medium (5). Pull-down experiments in which GST-DT140-271 was used as bait resulted in the observation that at least β-COP from the COPI coatomer complex specifically bound to this segment of DT (5). Moreover, the interaction between GST-DT140-271 and β-COP was found to be inhibited in a dose-dependent fashion by the addition of a synthetic peptide that carried the T1 motif. This observation suggested that the β-COP binding site on GST-DT140-271 at least overlapped with a portion of the T1 motif. Because the anthrax LF T1-like motif is positioned between amino acid residues 27–40 in a region of the toxin that has been shown to be essential for entry (10), we performed a series of GST-LFn pull-down experiments to determine whether β-COP or any of the COPI coatomer complex proteins might also interact with LF. In these experiments, GST and GST-LFn Sepharose beads were incubated with HeLa cell extracts and washed, and the immobilized proteins were then denatured and resolved by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot. As shown in Fig. 4 A and B, both β-COP (≈110 kDa) and ζ1-COP (≈28 kDa) (13, 14) are specifically pulled down from HeLa cell extracts by GST-LFn. In contrast, pull-down experiments in which GST alone was used as bait under the same conditions failed to bind either of these COPI coatomer proteins. Importantly, the addition of a synthetic peptide containing either the DT or the LFn T1 motif to the GST-LFn pull-down reaction mixture results in the dose-dependent loss of β-COP binding (Fig. 4 C and D). In control experiments, a peptide of similar molecular weight and pI as the T1 peptide had no effect on the binding of β-COP by GST-LFn (data not shown). Taken together these results raise the possibility that the interactions between β-COP or a COPI coatomer complex with GST-LFn are similar to those that have been shown to bind to the DT transmembrane helix 1 domain and facilitate the in vitro endosomal vesicle membrane translocation of the DT catalytic domain.

Fig. 4.

Addition of GST and GST-LFn to cytosolic extracts of HeLa cells results in the specific pull-down of COPI coatomer components. (A) Immunoblot of GST and GST-LFn pull-down reactions from HeLa cell extracts probed with anti-β-COP. (B) Immunoblot of GST and GST-LFn pull-down reactions from HeLa cell extracts probed with anti-ζ1-COP. (C) Immunoblot of GST-LFn pull-down reactions from HeLa cell extracts that were performed in the presence of increasing concentrations (50–200 nM) of a synthetic peptide containing the DT T1 motif and probed with anti-β-COP. (D) Immunoblot of GST-LFn pull-down reactions from HeLa cell extracts that were performed in the presence of increasing concentrations (25–100 nM) of a synthetic peptide containing the LF T1 motif and probed with anti-β-COP.

Immunodepletion of COPI Subunits from Cytosolic Extracts Attenuates in Vitro Translocation of LFnDTA.

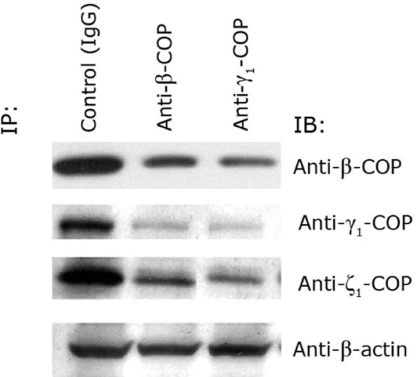

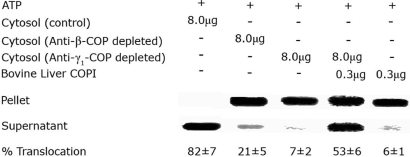

In an attempt to establish a functional role for β-COP and/or COPI coatomer complex in the translocation of LFnDTA from toxin-preloaded endosomal vesicles, we used anti-β-COP- and anti-γ-COP-specific antibodies to deplete COPI coatomer from cytosolic extracts by immunoprecipitation (15–17). Fig. 5 demonstrates that immunodepletion of cytosol with antibodies raised against any one COPI subunit results in the depletion of the other associated members of the COPI complex. Because all of the antibodies used in these studies were raised in rabbits, we used nonspecific rabbit IgG as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 6, immunodepletion of COPI coatomer complex proteins from HUT102/6TG cell extracts with either anti-β-COP or anti-γ1-COP antibodies resulted in a significant decrease in LFnDTA translocation and release from endosomal vesicles in vitro. Importantly, the addition of partially purified COPI coatomer complex proteins from bovine liver to immunodepleted HUT102/6TG cell extracts resulted in a partial restoration of in vitro LFnDTA translocation activity.

Fig. 5.

Immunoprecipitation of HeLa cell cytosolic extracts with either anti-β-COP or anti-γ1-COP results in the depletion of COPI coatomer complex proteins. Shown is immunoblot analysis of HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts after immunoprecipitation with anti-β-COP and anti-γ1-COP and probed with anti-β-COP, anti-γ1-COP, and anti-actin.

Fig. 6.

Immunodepletion of COPI coatomer complex proteins from HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts results in a reduction of in vitro LFnDTA translocation from endosomal vesicles. Immunodepleted HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts that were supplemented with partially purified bovine liver COPI coatomer complex reconstitutes in vitro LFnDTA translocation. Translocation assays were performed in the presence of 5 mM ATP and 8 μg of HUT102/6TG cytosolic extracts and processed for ADP-ribosyltransferase assays as described in Fig. 1. Percent translocation of LFnDTA ADP-ribosyltransferase activity into the high-speed supernatant fraction was determined as described in Fig. 2 (n = 3; ± SD).

Discussion

In the present report we have described a series of experiments that demonstrate that protective antigen PA63-mediated translocation and release of anthrax LF from the lumen of acidified endosomal vesicles likely occurs by two distinct but overlapping mechanisms. These observations confirm and extend earlier observations by Krantz and colleagues (18, 19), who demonstrated that the Φ-clamp in the PA transmembrane β-barrel functions as a chaperone in the voltage-dependent delivery of LF across the lipid bilayer (18–20). Although this study used artificial lipid bilayers, it clearly demonstrated that the Φ-clamp was required for LF translocation. In the simplest interpretation of these data, the Φ-clamp serves as a pH-dependent gate for anthrax catalytic domain (LF/EF) delivery to the cytosol. In this report, we have used partially purified endosomal vesicles that were preloaded with PA63 and the fusion protein LFnDTA to determine whether either the Φ-clamp alone or in concert with host cell factors was capable of facilitating the membrane translocation of LF from endosomal vesicles in vitro. In these studies, we used the ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of the DTA portion of LFnDTA as a sensitive measure of LF translocation and release into the external medium. This analysis has revealed a basal level of translocation and release of LFnDTA of ≈22 ± 2% of the total ribosyltransferase activity. This fractional release presumably is driven by the proton gradient established by ATP-dependent vATPase acidification of the endosomal vesicle lumen and gated by the PA63 intrinsic Φ-clamp (20).

We have used partially purified endosomal vesicles preloaded with PA63/LFnDTA to examine the requirements for LFnDTA translocation from the vesicle lumen to the external medium. We have demonstrated that the addition of HUT102G/6TG cytosolic extracts to an in vitro translocation assay mixture greatly stimulates LFnDTA translocation across the endosomal vesicle membrane and release into the external medium in a time- and dose-dependent manner. In the presence of cytosolic extracts under optimal conditions 87 ± 2% of the total vesicle-associated ADP-ribosyltransferase activity is translocated and released from vesicles within the first 10 min of incubation at 37°C. Under these conditions, where LFnDTA is almost completely translocated into the external medium, cointernalized HRP remains in the high-speed centrifugation pellet fraction and can be released only by detergent-mediated lysis. These results strongly support the hypothesis that the translocation of LFnDTA is specific and not due simply to the spontaneous disruption of endosomal vesicles or loss of membrane integrity. Moreover, because denaturation of cytosolic proteins by boiling of extracts before addition to the translocation assay inhibited in vitro LFnDTA translocation to control levels, it is likely that a protein factor(s) plays an important role in LFn translocation.

We have previously demonstrated that both ATP and cytosolic translocation factor (CTF) complex, which includes Hsp90, thioredoxin reductase, and β-COP, is required for DT catalytic domain translocation from toxin-preloaded endosomal vesicles in vitro (4, 6). In the present study, we have also shown that the addition of a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog, AMP-PNP, to the translocation assay mixture inhibits the translocation and release of LFnDTA from endosomal vesicles in vitro.

Ratts et al. (5) described a 10-aa motif, T1, in DT transmembrane helix 1 that appears to be essential in the translocation of the DT catalytic domain. Interestingly, this motif was found to be conserved in anthrax LF and EF, as well as in the botulinum neurotoxins, all of which deliver their catalytic domains after passage through an acidified endosomal compartment in their respective target cells. In the present study, we reasoned that the T1-like motif in anthrax LF may also be required for its efficient membrane translocation and release.

Because Ratts et al. (5) demonstrated that β-COP interacts with DT transmembrane helix 1 in a region that at least overlaps the T1 motif, we examined the potential interactions between LFn and target cell proteins by pull-down experiments using GST-LFn. We have demonstrated here that the use of GST-LFn as bait results in the specific pull-down of β-COP and ζ1-COP from cell extracts. Moreover, because the interaction between β-COP and LFn can be blocked in a dose-dependent fashion by a synthetic peptide that carries either the LFn or the DT T1 motif, we conclude that this interaction involves a common feature(s). In addition, we have shown that immunodepletion of COPI coatomer complex proteins from cytosolic extracts abolishes their ability to stimulate LFnDTA translocation and release from endosomal vesicles in vitro. Because the addition of bovine COPI complex proteins to immunodepleted cytosolic extracts restores LFnDTA translocation, we conclude that COPI coatomer complex proteins or possibly COPI-associated proteins are required for enhanced translocation. These results further suggest that COPI protein function is a key component of a cytosolic translocation factor complex for LF similar to those required for the translocation of the diphtheria toxin catalytic domain.

Abrami et al. (21) have demonstrated that a functional COPI coatomer complex was required for anthrax toxin action in intact cells in culture. In these experiments, cells expressing a temperature-sensitive mutant of ε-COP (21, 22) were shifted to the nonpermissive temperature, 40°C, and the resulting decrease in ε-COP expression resulted in an apparent block in the insertion of PA63 into the membrane. In the present study, analysis of partially purified endosomal vesicles revealed that PA63 was in a high-molecular-weight SDS-resistant form (23), suggesting that heptamerization and membrane insertion occurred normally during the process of toxin preloading before cell lysis and preparation of vesicles used in subsequent translocation assays. As a result, any role that COPI coatomer complex proteins might play in facilitating the PA63 vesicular membrane insertion process would not be expected to be altered. Because the addition of synthetic peptides that carry either the DT or the LF T1 motif were found to block the interaction between GST-LFn and β-COP, and immunodepletion of COPI from cytosolic extracts inhibits in vitro translocation of LFnDTA, we conclude that COPI complex proteins are most likely to play a direct role in facilitating the translocation process in addition to its potential involvement in PA63 vesicular membrane insertion.

The requirement for target cell vesicle-associated proteins and cytosolic factors in the translocation and release of LFnDTA as described here are consistent with our previous findings that DT translocation requires a cytosolic translocation factor (CTF) complex that includes COPI coatomer proteins. Because COPI coatomer complex proteins play an essential role in the translocation of both the DT catalytic domain and LFnDTA in vitro, and the interaction between COPI and either GST-DT140-271 or GST-LFn involves their respective T1 motif, we propose that the cytosolic delivery of the catalytic domains of both DT and AT share a similar, or at least partially overlapping, mechanism. We are currently testing the hypothesis that the interactions between COPI and the T1 motif represent an early step in the translocation of both the DT catalytic domain and anthrax LF. In both instances, we envision that as the T1 motif emerges from the pore formed by either the DT transmembrane domain or heptameric anthrax PA63, COPI coatomer complex protein(s) binds to the motif and facilitates translocation of their respective catalytic domains. Although these two toxins share few structural or functional characteristics, it is attractive to speculate that they have evolved convergently and exploit similar interactions with COPI in their respective mechanism(s) of entry into the eukaryotic cell cytosol.

Experimental Procedures

Partial Purification of Toxin-Preloaded Endosomal Vesicles.

Endosomes were isolated from HUT102/6TG T lymphocytes according to a flotation protocol modified from Lemichez et al. (6). The early endosomal compartment was loaded with 10 nM each of LFnDTA and PA63 (List) and/or 5 mg/ml HRP (Pierce) in the presence of 1 μM Bafilomycin A1 (LC Laboratories).

Preparation of Cytosolic Extracts from HUT102/6TG Cells.

Crude cytosolic extract was isolated from HUT102/6TG cells according to the protocol modified from Bomsel et al. (24). In brief, cells were washed three times with cold PBS, then lysed by 20 passages through a 25-gauge needle in cytosol buffer (CB: 8% sucrose/10 mM Hepes-KOH, pH 7.4/50 mM KCl/1.5 mM MgCl2/0.2 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT) containing protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The postnuclear supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was dialyzed overnight at 4°C against CB. No additional steps were taken to remove <2,500-Da molecular species.

In Vitro Translocation of LFnDTA from Endosomal Vesicles.

Translocation of LFnDTA was performed by using a protocol modified from Ratts et al. (4) as follows: 25-μl reaction mixtures contained 5 μl of early endosomes in translocation buffer (TB: 100 mM Tris·HCl/25 mM EDTA, pH 7.4). Each reaction contained ATP and/or cytosol as indicated. Translocation mixtures were incubated at 37°C for time indicated, and the supernatant fluid and pellet were separated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. The pellet fraction was resuspended in 25 μl of ribosyltransferase assay buffer containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma–Aldrich), and both the supernatant fluid and lysed pellet fraction were assayed for ADP-ribosyltransferase activity.

ADP-Ribosyltransferase Assay.

The in vitro NAD-dependent ADP-ribosylation of EF-2 was performed according to a modified protocol from Chung and Collier (25). Reaction mixtures contained 3 pM [32P]-NAD (≈1,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham), 5 mM ATP, 0.1 μg/μl crude HUT102/6TG cytosol, 15 ng/μl EF2, and 0.2% Triton X-100. Autoradiographic signals were obtained on AR film (Fuji), and phosphorimager signals were analyzed by Quantity One software (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer's directions.

HRP Activity Assay in Vesicles Coloaded with LFnDTA/PA.

The membrane integrity of purified early endosomes in the assay system was verified by using a protocol modified from Lemichez et al. (6) as follows: 200-μl reaction mixtures containing 40 μl of HRP and LFnDTA coloaded endosomes, 5 mM ATP, 0.3 μg/μl cytosol in TB with or without 0.2% Triton X-100 as indicated were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and the supernatant fluid and pellet were separated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. Both fractions were resuspended in a final volume of 400 μl of HRP reaction mixture containing Super Aqua Blue ELISA substrate (eBioscience) and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl of 625 mM oxalic acid. HRP activity was measured by spectrophotometry (absorbance 405 nm).

GST Pull-Down Experiments.

GST and the fusion protein GST-LFn were expressed in E. coli strain BL-21(DE-3) transformed with either pGEX-6P-1 or pGEX-LFn (LF 1–254) and purified as described by Bharti et al. (26). pGEX-LFn was constructed by using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-TACAAGCTCGAGCGATGACGGCGGCTGAGAAC-3′ and 3′-TTTATTTAGATAGGCCGCACTCCTAGGAGCAGT-5′.

Protein concentrations were determined by the modified Bradford reagent (Pierce). After purification, GST and GST-LFn were incubated separately with glutathione Sepharose beads (1 ml of GST beads per milligram of recombinant protein) at 4°C for 2 h in PBS. HeLa cell lysate was prepared and GST-pull down experiments were performed essentially as described (5). Briefly, HeLa cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris·HCl/10 mM KCl/1.5 mM MgCl2/1 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. The cells were homogenized, and the resulting lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 h. Equal volumes and concentrations of lysate were passed separately through GST and GST-LFn beads. Proteins bound to the bead columns were eluted by adding reducing SDS sample buffer and incubating at 98°C for 5 min. Elutions were then analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblot analysis with rabbit anti-β-COP (Abcam) or anti-ζ1-COP antibodies. The sequences of the synthetic peptides containing the 10-aa T1 motifs of the DT transmembrane domain and LFn are as follows: RDKTKTKIESLKEHGPIKNS and EERNKTQEEHLKEIMKHIVK (their respective T1 sequences are underlined). These peptides were synthesized and purified to at least 90% purity by high-performance liquid chromatography (21st Century Biochemicals and Kopella) and have molecular masses of 2,351 and 2,520 Da and pI values of 10.38 and 7.9, respectively. A 2,335-Da peptide with the sequence AENSDKHRIMQVFHRTLNQ with a pI of 8.8 was used as a negative control in pull-down experiments.

Immunodepletion of COPI Complex and Isolation of Enriched Fractions.

Protein G-Sepharose beads were blocked with crude cytosolic extracts for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were washed with cytosol buffer (CB) then incubated with anti-β-COP (Abcam) (17) or anti-γ1-COP antibodies for 1 h at 4°C. After washing extensively with cytosol buffer, cytosolic extracts (1.6 mg/40 μl beads) were added and incubated for 1 h at 4°C. Depleted cytosol was separated from beads by centrifugation. In this fashion, a single cytosol preparation was passed over three freshly prepared antibody-conjugated bead sets. Protein concentrations were determined by a modified Bradford reagent (Pierce), and cytosol was checked for depletion of coatomer by immunoblot. Coatomer-enriched fractions were prepared from bovine liver as described by Duden et al. (27). Briefly, fresh cow liver was perfused in ice-cold homogenization buffer (25 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/320 mM sucrose), homogenized by blender (Waring), and clarified by centrifugation in bovine cytosol buffer (25 mM Tris·HCl/50 mM KCl/250 mM sucrose/2 mM EDTA/protease inhibitors, pH 7.4). Bovine liver cytosol was prepared in bovine cytosol buffer by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. The resulting bovine liver cytosol was dialyzed against 25 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl, and 1 mM DTT. The bovine liver cytosol was then brought to 40% ammonium sulfate, and the coatomer-containing precipitate was collected by centrifugation and resuspended by Dounce homogenization in 60 ml of 25 mM Tris·HCl, 1 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol (pH 7.4). This material was diluted 1:1 in 25 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 10% sucrose, and 100 mM KCl and loaded onto a prepared 7.5–32.5% sucrose gradient. The 13S fraction containing intact COPI coatomer and associated proteins was then used a source of COPI coatomer to rescue translocation activity in immunodepleted HUT102/6TG cytosol preparations.

Electron Microscopy and Immunoblot Analysis of Endosomes.

Endosomal vesicles were loaded with LFnDTA/PA63 and after cell lysis were isolated by discontinuous sucrose ultracentrifugation as described above. Partially purified endosomal vesicles were pelleted by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C. The supernatant fluid was removed, and the pellet was fixed with 2% formaldehyde. After fixation at room temperature the pellet was washed with PBS containing 0.2 M glycine. Before freezing in liquid nitrogen the endosomal pellet was infiltrated with 2.3 M sucrose in PBS for 15 min. Frozen samples were sectioned at −120°C, and the sections were then transferred to formvar-carbon coated copper grids. Contrasting/embedding of the grids was performed on ice in 0.3% uranyl acetate in 2% methyl cellulose for 10 min. Processed grids were then examined in the electron microscope according to standard methods.

For immunoblots analysis, partially purified endosomal vesicles were diluted in SDS/PAGE loading buffer, and samples were then boiled and electrophoresed in SDS/polyacrylamide gels. After electrophoresis proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes. Immunoblots were then probed with the following antibodies: mouse anti-Rab5 (BD), rabbit anti-Rab7 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-LAMP1 (Abcam), and mouse anti-EEA1 (Abcam).

Acknowledgments.

Antibodies against γ1-COP and ζ1-COP were a generous gift from Dr. Felix T. Wieland (Biochemie Zentrum, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg). We thank Dr. Maria Ericsson (Harvard Medical School) for performing the transmission electron microscopy. This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant AI-021628 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (to J.R.M.) and by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Regional Center of Excellence Grant AI-057159.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0710100105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Finkelstein A. J Physiol (Paris) 1990;84:188–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller CJ, Elliott JL, Collier RJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10432–10441. doi: 10.1021/bi990792d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fischer A, Montal M. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29604–29611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratts R, Zeng H, Berg EA, Blue C, McComb ME, Costello CE, vanderSpek JC, Murphy JR. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:1139–1150. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ratts R, Trujillo C, Bharti A, vanderSpek J, Harrison R, Murphy JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15635–15640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504937102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemichez E, Bomsel M, Devilliers G, vanderSpek J, Murphy JR, Lukianov EV, Olsnes S, Boquet P. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:445–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1997.tb02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.vanderSpek JC, Howland K, Friedman T, Murphy JR. Protein Eng. 1994;7:985–989. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.8.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora N, Leppla SH. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4955–4961. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4955-4961.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milne JC, Blanke SR, Hanna PC, Collier RJ. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:661–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S, Finkelstein A, Collier RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16756–16761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405754101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trujillo C, Ratts R, Tamayo A, Harrison R, Murphy JR. Neurotox Res. 2006;9:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF03033924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen SH, Sandvig K, van Deurs B. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:731–741. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.4.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hara-Kuge S, Kuge O, Orci L, Amherdt M, Ravazzola M, Wileand FT, Rothman JE. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:883–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.6.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuge O, Hara-Kuge S, Orci L, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Tanigawa G, Wieland FT, Rothman JE. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1727–1734. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moelleken J, Malsam J, Betts MJ, Movafeghi A, Reckmann I, Meissner I, Hellwig A, Russell RB, Söllner T, Brügger B, Wieland FT. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4425–4430. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611360104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allan VJ, Kreis TE. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2229–2239. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowe M, Kreis TE. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31364–31371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krantz BA, Melnyk RA, Zhang S, Juris SJ, Lacy DB, Wu Z, Finkelstein A, Collier RJ. Science. 2005;309:777–781. doi: 10.1126/science.1113380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krantz BA, Finkelstein A, Collier RJ. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:968–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melnyk RA, Collier RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9802–9807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abrami L, Lindsay M, Parton RG, Leppla SH, van der Goot FG. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:645–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo Q, Penman M, Trigatti BL, Krieger M. J Biol Chem. 1999;271:11191–11196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rainey GJ, Wigelsworth DJ, Ryan PL, Scobie HM, Collier RJ, Young JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13278–13283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505865102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bomsel M, Parton R, Kuznetsov SA, Schroer TA, Gruenberg J. Cell. 1990;64:719–731. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90117-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung DW, Collier RJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;483:248–257. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(77)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bharti AK, Olson MO, Kufe DW, Rubin EH. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1993–1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duden R, Griffiths G, Frank R, Argos P, Kreis TE. Cell. 1991;64:649–665. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90248-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]