Abstract

Coliphage N4 virion RNA polymerase (vRNAP), which is injected into the host upon infection, transcribes the phage early genes from promoters that have a 5-bp stem–3 nt loop hairpin structure. Here, we describe the 2.0-Å resolution x-ray crystal structure of N4 mini-vRNAP, a member of the T7-like, single-unit RNAP family and the minimal component having all RNAP functions of the full-length vRNAP. The structure resembles a “fisted right hand” with Fingers, Palm and Thumb subdomains connected to an N-terminal domain. We established that the specificity loop extending from the Fingers along with W129 of the N-terminal domain play critical roles in hairpin-promoter recognition. A comparison with the structure of the T7 RNAP initiation complex reveals that the pathway of the DNA to the active site is blocked in the apo-form vRNAP, indicating that vRNAP must undergo a large-scale conformational change upon promoter DNA binding and explaining the highly restricted promoter specificity of vRNAP that is essential for phage early transcription.

RNA polymerases (RNAPs) belonging to the T7-like family consist of a single catalytic polypeptide of ≈100 kDa. This family includes phage-encoded, chloroplast and mitochondrial nuclear-encoded and linear plasmid-encoded enzymes (1). T7 RNAP has been the most extensively studied member of the family, and several crystal structures have been determined (2–5). However, with the exception of T7 and closely related phage T3, SP6, and K11 RNAPs, other members of the family require additional factors for transcription initiation. The yeast mitochondrial RNAP requires transcription factor Mtf1 (6, 7), which associates with the catalytic core RPO41 to form a holoenzyme that is competent for transcription initiation (8). It has been suggested that Mft1 plays a role in promoter melting, because yeast mitochondrial RNAP can initiate specifically on supercoiled or premelted (bubble) templates in the absence of Mtf1 (9). The human mitochondrial RNAP, POLRMT (10), accurately transcribes templates containing its cognate promoters only when supplemented with the high-mobility-group (HMG) protein TFAM (11, 12) along with either TFB1M or TFB2M transcription factors (13).

The early region of the double-stranded linear DNA genome of lytic coliphage N4 is transcribed by a phage-coded, virion-encapsidated RNAP (vRNAP), a 3,500-aa uncleaved polyprotein that is injected into the host cell with the phage genome at the onset of infection (14–16). Limited proteolysis experiments established that the N4 vRNAP polyprotein is composed of three functional domains; the central domain of ≈1,100 aa (mini-vRNAP), which possesses the same transcriptional specificity and properties as full-length vRNAP, is the most evolutionarily diverged member of the T7-like RNAP family (17). The vRNAP recognizes promoters that are composed of a 5-bp stem (nucleotides −17 to −13 and −9 to −5) and a three base-loop (nucleotides −12 to −10) hairpin with conserved sequence (18, 19). The Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein EcoSSB is required for vRNAP transcription initiation and elongation; other single-stranded DNA-binding proteins cannot substitute (20, 21).

To guide further studies aimed at understanding the transcription process of single-unit RNAPs and to elucidate how N4 vRNAP recognizes the unusual hairpin DNA promoter, we have determined the x-ray crystal structure of N4 mini-vRNAP at 2.0-Å resolution. Based on this structure, and on the results of promoter-mini-vRNAP cross-linking studies, together with site-specific mutagenesis of the enzyme, we provide a structural basis for vRNAP recognition of its hairpin promoter and propose a mechanism for promoter-driven enzyme activation.

Results and Discussion

Structure Determination.

The crystal structure of the bacteriophage N4 mini-vRNAP was determined by multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) phasing using selenomethionine-substituted protein. Data collection and refinement statistics are detailed in supporting information (SI) Text. The final crystallographic model contains mini-vRNAP residues 11–1104 plus 475 water molecules with an R-factor of 21.9% (Rfree = 24.8%).

The Crystal Structure of the Mini-vRNAP.

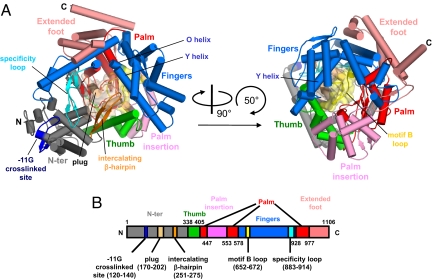

The overall architecture of N4 mini-vRNAP resembles a “fisted right hand” (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1) with approximate dimensions of 96 Å × 81 Å × 70 Å. The mini-vRNAP molecular volume (147,108 Å3) is ≈29% larger than that of the initiation form of the T7 RNAP (Fig. S2A) (3). We were unable to define the domain and subdomain organization of mini-vRNAP using ordinary sequence alignment programs with the T7 RNAP sequence because of the low sequence similarity (17). However, a 3D structural alignment by DALI (22) allowed us to identify clear structural similarities to the structure of T7 RNAP in the promoter complex and to define an N-terminal domain and a polymerase domain with its component Thumb, Palm, and Fingers subdomains in mini-vRNAP (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). In addition, the structural alignment identified three T7 RNAP structural motifs in mini-vRNAP: the AT-rich recognition loop, the intercalating β-hairpin (both in the N-terminal domain), and the specificity loop (extending from the Fingers) (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1). Mini-vRNAP has a 33-residue insertion that forms a globular module—the “plug”—between α-helices 7 and 10 of the N-terminal domain (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1), which is absent from T7 RNAP (Figs. S2 and S3). We discuss this feature below.

Fig. 1.

X-ray crystal structure of N4 mini-vRNAP. (A) Overall views of N4 mini-vRNAP. Domain and subdomains are represented in their characteristic colors as in B. α-Helices and β-strands are depicted as cylinders and arrows, respectively. The plug and motif B loop are represented as molecular surfaces with partial transparency. Part of the N-terminal domain (residues 120–145, dark blue) has been identified as interacting with the −11 base of the promoter hairpin triloop; this region is a structural counterpart of the AT-rich recognition loop of the T7 RNAP. (Right) Another N4 mini-vRNAP view, derived from (Left) as indicated by the arrows. (B) The thick bar represents the N4 mini-vRNAP primary sequence with amino acid numbering. Domains, subdomains and structural motifs are labeled and color-coded as in A.

The N4 mini-vRNAP N-terminal domain contains 337 aa that form an independently folded “V-shape” domain, which associates with the polymerase domain to constitute a platform for promoter DNA binding (Fig. 1A). Results of DNA–protein cross-linking experiments indicated that the central base of the hairpin triloop (−11G) interacts with a surface-exposed segment (residues 120–140, −11G cross-link site in Fig. 1A) of the N4 mini-vRNAP N-terminal domain (23). N4 mini-vRNAP (residues 251–275) (Fig. 1A) has an obvious counterpart of the T7 RNAP intercalating β-hairpin that plays a role in DNA melting of the T7 RNAP promoter duplex. vRNAP is unable to unwind double-stranded DNA to form an open transcription complex (18). Strand opening at N4 vRNAP promoters is achieved by template supercoiling and is stabilized by EcoSSB, which binds to the complementary strand and acts as an architectural transcription factor (20).

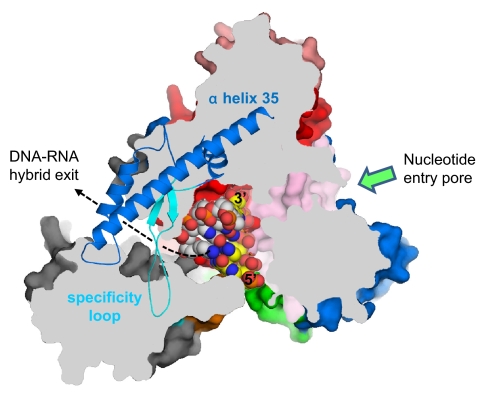

The N4 vRNAP RNA product is not displaced from template DNA, thus limiting template DNA usage to one round (21). Modeling of the DNA–RNA hybrid in the N4 mini-vRNAP structure (Fig. 2) allowed us to find the direction of transcribing RNA and identify a pore, which is surrounded by the N-terminal domain, Palm, and Fingers including the specificity loop. However, the dimensions of the pore (25 Å high and ≈15 Å wide) are not sufficient to allow passage of the DNA–RNA hybrid. Whether the N-terminal domain undergoes a structural rearrangement upon proceeding from initiation to transcript elongation, which enlarges the pore sufficiently to enable the A-form DNA–RNA hybrid to exit from the complex without strand separation, remains to be determined. EcoSSB activates vRNAP transcription at limiting single-stranded template concentrations through template recycling, a function that has been mapped to the C-terminal 10 residues of the EcoSSB (21). We have proposed that EcoSSB functionally substitutes for part of the N-terminal domain of RNAP that should be responsible for RNA separation from template DNA during N4 vRNAP elongation (21). This hypothesis is consistent with our structural observation that mini-vRNAP lacks the counterpart of T7 RNAP subdomain H (Fig. S3), which is involved in displacement of the RNA from the DNA–RNA hybrid (24, 25). We have been unable to detect direct interaction between mini-vRNAP and EcoSSB (E.K.D., unpublished results), although these might only occur in the presence of template or upon entry into the transcription elongation phase (21).

Fig. 2.

A pore for exit of the DNA–RNA hybrid. View of the N4 mini-vRNAP structure, shown as a molecular surface. Orientation of this view is the same as in Fig. 1A Left with the same color code. The molecular surface has been sliced by a parallel plane to this view. The plug module has been removed for clarity. A portion of the Fingers (residues 803–928), which is above the plane, is depicted as a ribbon model, revealing a pore surrounded by the N-terminal domain, Palm core, and Fingers including α-helix 35 and the specificity loop. The pore is ≈25 Å high and ≈15 Å wide. Four base pairs of DNA–RNA hybrid from the T7 RNAP elongation complex (the N4 mini-vRNAP and T7 RNAP elongation complex were aligned at their Palm cores) have been placed in the structure. DNA template strand, white; RNA, yellow; 5′ and 3′ ends of RNA are labeled (5). The RNA extends from the active center to the pore, suggesting that the pore is a putative DNA–RNA hybrid exit channel in the transcription elongation complex; the direction of RNA extending to the pore is indicated by a dashed line. The nucleotide entry pore to the RNAP active center is also indicated by a green arrow.

The N4 mini-vRNAP Palm (residues 405–577 and 928-1106), located at the base of a deep cleft bounded by the Fingers and Thumb, catalyzes the nucleotidyl transferase reaction (Fig. 1). The structural comparison of T7 RNAP with Pol I family DNAPs identifies insertions in the T7 RNAP Palm (2) denoted as Palm insertion (residues 449–530) and extended foot (residues 839–883) (Fig. S2). These insertions are also present in the N4 mini-vRNAP structure (Fig. 1) suggesting essential roles in single-unit RNAPs. For convenience, we have denoted the Palm excluding the Palm insertion and extended foot as the “Palm core.” The structures of almost the entire the Palm cores of the N4 and T7 RNAPs can be superimposed, although they share only 28% sequence similarity (12.8% identity). The superposition establishes D559 and D951 as the active site residues in the N4 vRNAP (Fig. 3B), a proposition that has been confirmed by mutational analyses and iron-induced cleavage experiments (17).

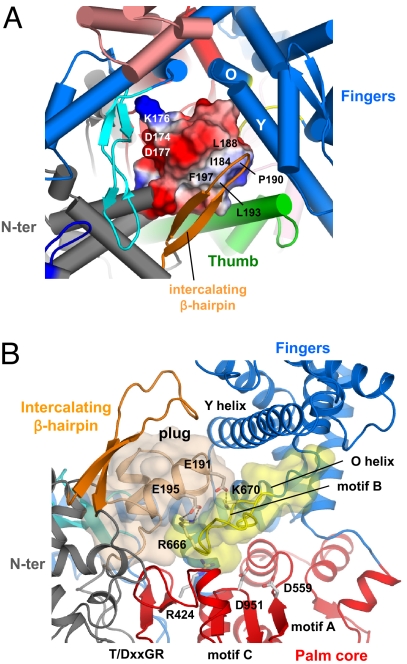

Fig. 3.

The Plug module blocks the DNA-binding channel. (A) Close-up view of the DNA-binding channel of N4 mini-vRNAP shown in the same orientation as Fig. 1A Right. The plug module, which has an amphipathic surface, is depicted as its molecular surface with electrostatic distribution (positive electrostatic potential is blue, negative potential is red, and neutral is white). The hydrophobic surface (including residues I184, L188, P190, L193, and F197) interacts with the intercalating β-hairpin and Thumb, whereas the hydrophilic surface (including residues D174, K176, and D177) faces the Palm core. (B) Close-up view showing that the plug and the Palm core sandwich the motif B loop, burying almost all amino acid residues essential for the catalytic activity of RNAP; R424 (T/DxxGR motif) for substrate binding, D559 (motif A), and D951 (motif C) for chelating the catalytically essential Mg2+ ions, and R666 and K670 (motif B) for substrate binding. E191 and E195 in the plug form salt bridges, indicated as dotted lines, with R666 and K679, respectively. The Thumb and Palm insertions have been removed from this view for clarity.

The Fingers subdomain contains two essential functions of RNAP: the N-terminal two-thirds of the subdomain play a role in the nucleotide addition cycle, whereas the C-terminal one-third is involved in promoter recognition. The first half (residues 578–805) of the N4 mini-vRNAP Fingers (residues 578–927) contains nine α-helices including the O/Y helices and two β-strands (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1). It is well established that a swing motion of this part of the Fingers is coupled with nucleotide addition, translocation of the DNA–RNA hybrid, and downstream double-strand DNA opening (26, 27).

The O-helix contains part of motif B (Rx3Kx7YG, Fig. S1B), which is perfectly conserved in all DNAPs and RNAPs, binds the triphosphate moiety of the incoming nucleotide. The N4 mini-vRNAP motif B sequence was identified at residues 666–679, and results of site-specific mutagenesis experiments showed that residues K670 and Y678 play roles in NTP binding and discrimination against dNTP, respectively (17). The N terminus of N4 mini-vRNAP motif B forms a singular structure, the “motif B loop,” which protrudes into the DNA-binding pocket and makes extensive interactions with the plug module (Fig. 3B, light brown) and the Palm core.

The C-terminal one-third of the Fingers subdomain (residues 806–927) forms the left-side wall of the active center cleft. It has an inserted segment, called the “specificity loop” (residues 883–914, Figs. 1A and 3A), which extends across the catalytic cleft and packs against the N-terminal domain. The tip of the specificity loop has three surface-exposed hydrophilic residues (D901, R902, and R904, Fig. 4A), and Ala substitutions at these residues significantly reduce vRNAP-promoter binding affinity (this study). N4 mini-vRNAP has an inserted segment (residues 827–868) relative to T7 RNAP, which makes α-helix 35 twice as long as the corresponding T7 RNAP α-helix (Fig. S1). Helix 35 reaches to, and interacts extensively with, the N-terminal domain to constitute the top wall of the DNA–RNA hybrid exit channel on the back of mini-vRNAP (Figs. 1A and 2). Two lines of evidence suggest that this insertion segment plays a role in promoter binding. This segment (residues 843–854) has been shown to lie relatively close to nucleotide −11 by photochemical cross-linking to an azidophenacyl-derivatized phosphorothioate internucleotide linkage (−1/−12, E.K.D., I. Kaganman, K. Kazmierczak, M. Gittman, and L.B.R.-D., unpublished work), and Ala substitutions at K849 and K850 reduce RNAP-promoter binding (this study).

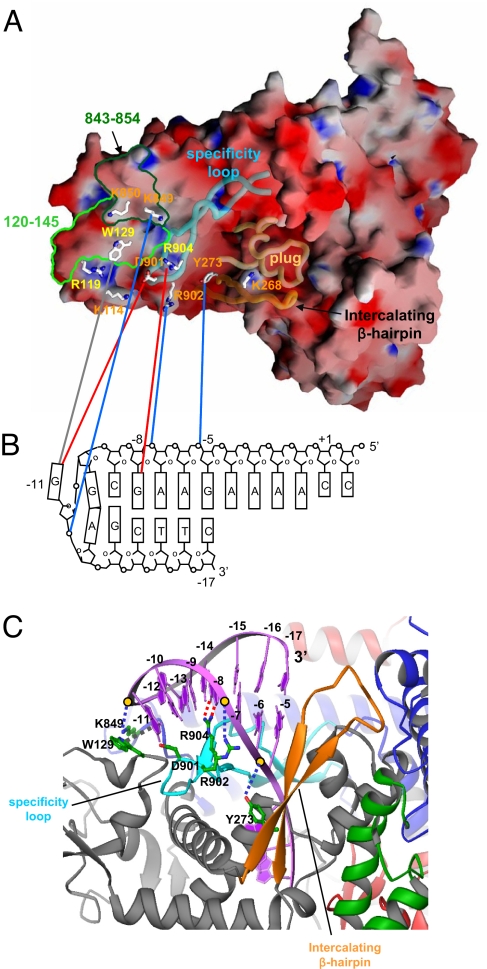

Fig. 4.

Recognition of hairpin-promoter by N4 mini-vRNAP. (A) Electrostatic distribution of N4 mini-vRNAP. Positive electrostatic potential is blue, and negative potential is red. The transparent α-carbon backbones of the specificity loop, intercalating β-hairpin and plug are superimposed. Residues identified from biochemical studies to be important for promoter binding are depicted as stick model and labeled and color-coded as follows: major promoter binding and salt resistance, yellow; minor promoter binding, orange. Mapped −11 5IdU (light green, residues 120–145) and −11/−12 AzPh (dark green, residues 843–854) cross-links are also shown. This figure was made with the program GRASP (32). (B) N4 mini-vRNAP and promoter hairpin DNA interaction. A schematic representation of the N4 vRNAP P2 promoter is shown. The transcription start site (+1), beginning, and end of the hairpin-stem (−5 and −17, respectively), and DNA bases essential for vRNAP binding (−8 and −11) are indicated. N4 mini-vRNAP residues that participate in promoter recognition (A) are connected to their proposed interacting partners on promoter DNA (B) by lines: potential van der Waal's interaction between −11 G and W129 (gray), −8 G recognition by R904 (red), −11 G recognition by D901 (red), and phosphate backbone interactions by Y273 (−5/−6 P), R902 (−7/−8 P) and K849 (−11/−12 P) (blue). (C) Docked model of the N4 mini-vRNAP and promoter hairpin DNA. Hairpin-form DNA is depicted as purple ribbon and bases are labeled. N4 mini-vRNAP residues that participate in promoter recognition are indicated. Dashed lines indicate protein-DNA interactions as shown in B. This figure was made with the program Ribbons (33).

Mini-vRNAP Inactivation by the Plug Module.

The volume of the plug module (3,535 Å3) is similar to that of the 7-bp DNA–RNA hybrid in the T7 RNAP transcription elongation complex (4, 5). The plug makes multiple contacts with the T/DxxGR motif in the Palm core and with the motif B and the O/Y-helices of the Fingers. The plug module also interacts with the intercalating β-hairpin of the N-terminal domain, α-helix 17 of the Thumb (Figs. 1A and 3). Indeed, 64% of the accessible surface of the plug module participates in these interactions. The plug and the Palm-core sandwich the motif B loop, burying almost all amino acid residues essential for the catalytic activity, including R424 (of the T/DxxGR motif) for substrate binding, D559 (motif A) and D951 (motif C) for chelating the catalytically essential Mg2+ ions, and R666 and K670 (motif B) for substrate binding (Fig. 3B).

The plug has an amphipathic protein surface (Fig. 3A): its hydrophobic side (I184, L188, P190, L193 and F197) interacts with the intercalating β-hairpin and Thumb, and its hydrophilic side (D174, K176 and D177) faces the wall of the DNA-binding channel formed by the Palm core and the second half of the Fingers. Thus, the plug occupies the pocket that accommodates DNA (Fig. 1A Left), and we expect that it must change its location when single-stranded DNA enters the channel to form a functional transcription complex.

Why does N4 mini-vRNAP have a plug that must block its activity? N4 vRNAP is present in one to two copies per virion and is injected into a host cell along with the N4 linear genome at the onset of infection (15, 16). vRNAP recognizes a DNA hairpin structure at the promoter that arises from the introduction of negative supercoiling by E. coli DNA gyrase (28, 29). Subsequent binding of EcoSSB unwinds the nontemplate-strand hairpin allowing vRNAP to bind to the template-strand hairpin, which is resistant to melting by EcoSSB (19, 20, 28). We surmise that the enzyme is maintained in an inactive conformation until this transcription-compatible structure of the promoter is elicited; furthermore, we propose that the promoter hairpin must act as the “key” to open the locked, inactive-form of vRNAP. Moreover, the existence of the inactive form of vRNAP explains its very low activity on single-stranded DNAs lacking promoters (30); indeed, the injection of vRNAP in an inactive state would preclude binding of nonspecific single-stranded DNA into its active site.

Mini-vRNAP–Promoter DNA Interaction.

Although the overall charge of RNAP is highly negative (the pI of mini-vRNAP is 5.25), the distribution of electrostatic charge over the surface is not uniform (Fig. 4A). The outside of the enzyme is almost uniformly acidic, except for surfaces that we propose to be the binding site for promoter DNA. The basic region includes the specificity loop, the C-terminal end of α-helix 35, the loop between helices 35 and 36, and a site on the N-terminal domain.

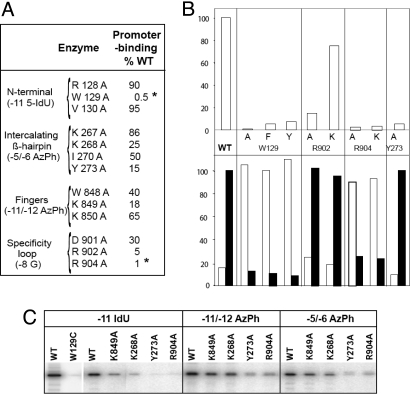

Two positions at the N4 vRNAP promoters are essential for RNAP binding: −11G at the center of the hairpin triloop, and −8G on the downstream side of the hairpin stem (23; Fig. 5B). Substitutions at these positions decrease promoter-binding affinity and render the otherwise salt-resistant promoter–RNAP complex salt-sensitive (31). Mini-vRNAP interactions at these positions require the G 6-keto and 7-imino groups, indicating that recognition of −8G in the stem must occur through the major groove. Although the affinity of mini-vRNAP to a 20-mer promoter-containing oligonucleotide (−7 to +3) with 5-iododeoxyuracil (5IdU) at position −11 decreases 250-fold, cross-linking by 320 nm light occurs with high efficiency (Fig. 5C) (23). The mini-vRNAP residue cross-linked to −11 5IdU was localized to W129 (23). Replacement of W129 with C abolished cross-linking (Fig. 5C, WT vs. W129C). Promoter binding was greatly decreased when W129 was replaced with F or Y or abolished when replaced with A (Fig. 5B Upper). All three substitutions rendered the promoter complex salt-sensitive (Fig. 5B Lower). Amino acids flanking W129 do not participate in this interaction (Fig. 5A, R128A and V130A). These results indicate that W129 is essential for N4 mini-vRNAP–promoter interaction.

Fig. 5.

Effects of mini-vRNAP amino acid substitutions on promoter interaction. (A) Effects of mini-vRNAP amino acid substitutions in the N-terminal, intercalating β-hairpin, Fingers, and specificity loop on promoter binding. Asterisks indicate amino acid substitutions that render the promoter complex salt-sensitive. (B) Effects of amino acid substitutions on promoter binding (Upper) and salt-resistance (Lower). (C) Effects of mini-vRNAP amino acid substitutions on RNAP cross-linking to −11 5IdU-, −11/−12 AzPh-, and −5/−6 AzPh-substituted promoters.

Mini-vRNAP contacts with the promoter DNA phosphate backbone were identified through mini-vRNAP cross-linking to 5′ 32P end-labeled oligonucleotides containing single azidophenacyl (AzPh)-derivatized phosphorothioate-linked nucleotides and mapping. Contacts to the −11/−12 and −5/−6 phosphates were localized to the residues 843–854 (present in close proximity to W129, see Fig. 4A) and the residues 260–280 (intercalating β-hairpin) regions, respectively (Fig. 4A; E.K.D., I. Kaganman, K. Kazmierczak, M. Gittman, and L.B.R.-D., unpublished work).

Based on these results, and on homology modeling of promoter DNA from the structure of the T7 RNAP-promoter complex (3), the promoter was docked onto the structure of mini-vRNAP (Fig. 4C). All interactions predicted by the modeled complex clustered on the basic patch of mini-vRNAP encompassing: (i) the specificity loop (residues D901, R902, and R904 and −8G in the promoter hairpin stem), (ii) the loop between α-helices 35 and 36 (residues K849 or K850 and −11/−12 phosphate), and (iii) the intercalating β-hairpin (residues 260–280 and −5/−6 phosphate) (Fig. 4C).

To test the relevance of the proposed interactions, mini-vRNAP enzymes with changes in the residues predicted to interact with the promoter were characterized (Fig. 5). All three elements of the basic patch were targeted (Fig. 5A). Amino acid substitutions in the intercalating β-hairpin affected promoter-binding affinity to different extents (Fig. 5 A and B), as reflected by reduced cross-linking to a −11 5IdU-substituted promoter (Fig. 5C). However, these substitutions had no effect on the salt resistance of the resulting complex (Fig. 5 A and B, Lower). The Y273A substitution reduced cross-linking to −11 5IdU-, −11/−12 AzPh-, and −5/−6 AzPh-derivatized promoters (Fig. 5C). Mapping the −5/−6 AzPh cross-link to the amino acid 260–280 region and the docked model suggest that Y273 interacts with the −5/−6 phosphate (Fig. 5C). The effect of the Y273A substitution on cross-linking to −11 5IdU or −11/−12 AzPh-substituted promoters indicates that the interaction between Y273 and the −5/−6 phosphate is important for positioning the hairpin on the surface of the basic patch for interactions with −11 and −8G.

The K849A substitution led to a 5-fold decrease in promoter binding affinity (Fig. 5A) and cross-linking to a −11 5IdU-substituted promoter (Fig. 5C). Based on the mapping of the −11/−12 AzPh cross-link to the 843–854 residue segment, in the loop between α-helices 35 and 36 in the Fingers and the location of K849 in the docking model, we propose that K849 interacts with the −11/−12 phosphate (Fig. 5).

Although with different consequences, substitutions of all three charged amino acids in the specificity loop (D901, R902, and R904) affected promoter–RNAP interactions. The D901A and R902A enzymes showed decreased promoter-binding affinity, but the substitutions had no effect on the salt-resistance of the promoter complex (Fig. 5A). Substitution of R902 with K yielded an enzyme with nearly wild-type properties indicating that the positive charge is necessary for promoter interaction (Fig. 5B). Our docked model suggests that R902 interacts with the −7/−8 phosphate, whereas D901 interacts with the −11G 2-amino group (Fig. 5). In contrast, the R904A mutant enzyme showed a 100-fold decrease in promoter binding, yielding a salt-sensitive complex (Fig. 5 A and B Lower). Similar results were obtained when the affinity and salt resistance of wild-type mini-vRNAP to promoters with substitutions of −8G to −8 2-aminopurine or −8 7-deazaG were analyzed (23). Because R904 cannot be substituted by K (Fig. 5B), these results indicate that R904 is making a bidentate interaction in the major groove of the stem with −8G, as predicted by the docking model. We propose that the −8G–R904 interaction plays a role in the correct placement of W129 for stacking with −11G, explaining the salt-sensitivity of the mini-vRNAP R904A-promoter complex.

Concluding Remarks.

The N4 mini-vRNAP crystal structure provides a framework for addressing the mechanism of factor-dependent transcription by the single-unit RNAPs. The structure-based biochemical experiments presented provide insights into: (i) the highly restricted specificity of N4 vRNAP for single-stranded promoter-containing template through blockage of the DNA-binding pathway by its plug module, (ii) the interaction of vRNAP with its promoter hairpin, and (iii) the unusual salt resistance of promoter–polymerase complex. The structures of mini-vRNAP–promoter complexes will provide answers to how the interaction with the promoter allows activation of the enzyme and explain why the stacking of W129 with the main determinant of promoter recognition leads to a promoter–vRNAP complex that is so remarkably salt resistant.

Methods

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination.

For details of protein purification, crystallization, data collection, and structure determination, see SI Text.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Mini-vRNAP.

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out on plasmid pEKD27, a derivative of pKMK25 where the Myc epitope sequence (GTIWEFEAYVEQKLISEEDLNSAVD) was deleted, resulting in mini-vRNAPHis6, by using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Mutant mini-vRNAP enzymes contain the following DNA sequence changes: R128A, CGT to GCT; W129C, TGG to TGC; W129A, TGG to GCG; W129F, TGG to TTC; W129Y, TGG to TAC; V130A, GTA to GCA; K176C, AAA to TGC; K267A, AAG to GCG; K268A, AAG to GCG; I270A, ATT to GCT; Y273A, TAC to GCC; W848A, TGG to GCG; K849A, AAG to GCG; K850A, AAA to GCA; S885C, TCA to TGT; D901A, GAC to GCC; R902A, CGT to GCT; R902K, CGT to AAG; R904A, CGT to GCT; R904K, CGT to AAA. The sequence of all polymerase expression constructs was confirmed. Enzymes were produced and purified as described (31). Mutant mini-vRNAP enzymes were diluted to 10 μM in 50% glycerol, 20 mM Tris·HCl at pH 8.0, and kept at −20°C.

UV Cross-Linking of 5-IododU-Substituted or Azidophenacyl-Modified Promoter Oligonucleotides to Wild-Type Mini-vRNAP and Variants.

Cross-linking of wild-type mini-vRNAP and mutant enzymes to 5IdU-substituted or azidophenacyl-modified P2–3 deoxyoligonucleotides (5′TCCAAAA GAAGCGGAGCTTC3′, +1 and inverted repeats italicized), was performed as described except that 5-min irradiation was used for azidophenacyl-modified deoxyoligonucleotides (23) (E.K.D., I. Kaganman, K. Kazmierczak, M. Gittman, and L.B.R.-D, unpublished work).

Salt Resistance of Promoter–vRNAP Complexes and Determination of Equilibrium Dissociation Binding Constants.

The salt resistance of mini-vRNAP–promoter complexes and determination of equilibrium dissociation constants were performed as described (23).

Acknowledgments.

We are indebted to M. Becker and the staff at X25 of the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY) for support during data collection. The figures were prepared by using PyMOL (http://pymol.sourceforge.net/) and GRASP (32). We thank Erna Davydova and Luciano Marraffini for the construction of mini-vRNAP mutant clones. We thank E. P. Geiduschek, J. G. Ferry, S. A. Darst, and R. Yajima for critiques of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants AI12575 (to L.B.R.-D.), and GM071897 (to K.S.M.) This work was initiated in the laboratory of Seth A. Darst with the support of NIH Grant GM61898 (to S. A. Darst).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2PO4).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0712325105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cermakian N, Ikeda TM, Cedergren R, Gray MW. Sequences homologous to yeast mitochondrial and bacteriophage T3 and T7 RNA polymerases are widespread throughout the eukaryotic lineage. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:648–654. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeruzalmi D, Steitz TA. Structure of T7 RNA polymerase complexed to the transcriptional inhibitor T7 lysozyme. EMBO J. 1998;17:4101–4113. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheetham GM, Jeruzalmi D, Steitz TA. Structural basis for initiation of transcription from an RNA polymerase-promoter complex. Nature. 1999;399:80–83. doi: 10.1038/19999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tahirov TH, et al. Structure of a T7 RNA polymerase elongation complex at 2.9 Å resolution. Nature. 2002;420:43–50. doi: 10.1038/nature01129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin YW, Steitz TA. Structural basis for the transition from initiation to elongation transcription in T7 RNA polymerase. Science. 2002;298:1387–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.1077464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkley CS, Keller MJ, Jaehning JA. A multicomponent mitochondrial RNA polymerase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14214–14223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schinkel AH, Koerkamp MJ, Touw EP, Tabak HF. Specificity factor of yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Purification and interaction with core RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12785–12791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangus DA, Jang SH, Jaehning JA. Release of the yeast mitochondrial RNA polymerase specificity factor from transcription complexes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26568–26574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsunaga M, Jaehning JA. A mutation in the yeast mitochondrial core RNA polymerase, Rpo41, confers defects in both specificity factor interaction and promoter utilization. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2012–2019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiranti V, et al. Identification of the gene encoding the human mitochondrial RNA polymerase (h-mtRPOL) by cyberscreening of the Expressed Sequence Tags database. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:615–625. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher RP, Clayton DA. A transcription factor required for promoter recognition by human mitochondrial RNA polymerase. Accurate initiation at the heavy- and light-strand promoters dissected and reconstituted in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:11330–11338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parisi MA, Clayton DA. Similarity of human mitochondrial transcription factor 1 to high mobility group proteins. Science. 1991;252:965–969. doi: 10.1126/science.2035027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falkenberg M, et al. Mitochondrial transcription factors B1 and B2 activate transcription of human mtDNA. Nat Genet. 2002;31:289–294. doi: 10.1038/ng909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothman-Denes LB, Schito GC. Novel transcribing activities in N4-infected Escherichia coli. Virology. 1974;60:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(74)90366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falco SC, Laan KV, Rothman-Denes LB. Virion-associated RNA polymerase required for bacteriophage N4 development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:520–523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falco SC, Zehring W, Rothman-Denes LB. DNA-dependent RNA polymerase from bacteriophage N4 virions. Purification and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4339–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazmierczak KM, Davydova EK, Mustaev AA, Rothman-Denes L-B. The phage N4 virion RNA polymerase catalytic domain is related to single-subunit RNA polymerases. EMBO J. 2002;21:5815–5823. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haynes LL, Rothman-Denes LB. N4 virion RNA polymerase sites of transcription initiation. Cell. 1985;41:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glucksmann MA, Markiewicz P, Malone C, Rothman-Denes LB. Specific sequences and a hairpin structure in the template strand are required for N4 virion RNA polymerase promoter recognition. Cell. 1992;70:491–500. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90173-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glucksmann-Kuis MA, Dai X, Markiewicz P, Rothman-Denes LB. E. coli SSB activates N4 virion RNA polymerase promoters by stabilizing a DNA hairpin required for promoter recognition. Cell. 1996;84:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davydova EK, Rothman-Denes LB. Escherichia coli single-stranded DNA-binding protein mediates template recycling during transcription by bacteriophage N4 virion RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9250–9255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133325100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holm L, Sander C. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:123–138. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davydova EK, Santangelo TJ, Rothman-Denes LB. Bacteriophage N4 virion RNA polymerase interaction with its promoter DNA hairpin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7033–7038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610627104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopal V, Brieba LG, Guajardo R, McAllister WT, Sousa R. Characterization of structural features important for T7 RNAP elongation complex stability reveals competing complex conformations and a role for the non-template strand in RNA displacement. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:411–431. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang M, Ma N, Vassylyev DG, McAllister WT. RNA displacement and resolution of the transcription bubble during transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. Mol Cell. 2004;15:777–788. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin YW, Steitz TA. The structural mechanism of translocation and helicase activity in T7 RNA polymerase. Cell. 2004;116:393–404. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Temiakov D, et al. Structural basis for substrate selection by T7 RNA polymerase. Cell. 2004;116:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai X, Greizerstein MB, Nadas-Chinni K, Rothman-Denes LB. Supercoil-induced extrusion of a regulatory DNA hairpin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2174–2179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai X, Kloster M, Rothman-Denes LB. Sequence-dependent extrusion of a small DNA hairpin at the N4 virion RNA polymerase promoters. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:43–58. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Falco SC, Zivin R, Rothman-Denes LB. Novel template requirements of N4 virion RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3220–3224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davydova EK, Kazmierczak KM, Rothman-Denes LB. Bacteriophage N4-coded, virion-encapsulated DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol. 2003;370:83–94. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholls A, Sharp KA, Honig B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carson M. RIBBONS 2.0. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:958–961. [Google Scholar]