Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To review resources available to aid family physicians in their care of prostate cancer patients and develop an algorithm to summarize these findings.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and relevant website search. All relevant guidelines were level III evidence.

MAIN MESSAGE

Improved screening and treatment of patients with prostate cancer is resulting in an increasing number of survivors. These men require ongoing monitoring, a responsibility that is largely falling to family physicians. We review the expected prostate-specific antigen (PSA) responses to different prostate cancer treatment modalities and provide an appropriate schedule of follow-up and monitoring techniques for prostate cancer patients.

CONCLUSION

In light of the paucity of resources for family physicians in their ongoing care of prostate cancer patients, we present an algorithm, primarily based on PSA kinetics, for practical use in the continuing care of these patients.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Faire le point sur les ressources disponibles pour aider les médecins de famille à soigner des patients atteints un cancer de la prostate et développer un algorithme pour résumer ces constatations.

SOURCES DE L’INFORMATION

MEDLINE, EMBASE et sites WEB pertinents. Toutes les directives applicables présentaient des preuves de niveau III.

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

Avec l’amélioration du dépistage et du traitement du cancer prostatique, de plus en plus de patients y survivent. Ces patients requièrent une surveillance continue, et cette responsabilité repose en grande partie sur le médecin de famille. Cet article fait le point sur les réponses habituelles de l’antigène prostatique spécifique (PAS) à différents modes de traitement de ce cancer et propose un calendrier de suivi commode et des techniques de monitorage pour les patients.

CONCLUSION

Vu le peu de ressources dont dispose le médecin de famille dans le suivi des patients atteints de cancer prostatique, nous suggérons un algorithme, basé principalement sur les variations du PAS, comme outil pratique dans le suivi de ces patients.

Case 1

Mr A. is a healthy 71-year-old man treated for prostate cancer (Gleason score 6, pretreatment prostate-specific antigen [PSA] level 9 ng/mL) with radical prostatectomy 5.5 years ago. His care has now been transferred back to you. His PSA level has increased from undetectable 6 months ago to 0.7 ng/mL currently. He has no new clinical symptoms. Do you need to be concerned by this increase?

Case 2

Mr P. is a 63-year-old man who underwent brachytherapy 4 years ago for prostate cancer (Gleason score 5, PSA 7 ng/mL) and is now under your care for his ongoing follow-up. His PSA nadir was 0.2 ng/mL, and PSA values taken every 3 months have been 0.7 ng/mL, 1.0 ng/mL, 0.8 ng/mL, and, most recently, 0.5 ng/mL. What should you do?

Prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer among Canadian men, accounting for 26.4% of newly diagnosed cases of cancer in men in 2006.1 The introduction of PSA testing as a means of screening for prostate cancer has resulted in a stage migration. Because of this, it is almost certain that family practitioners will have patients who have been diagnosed with and treated for this neoplasm.2 Additionally, a substantial proportion of patients will have clinical recurrences more than 5 years after their initial treatment. Family physicians therefore need to understand the appropriate monitoring and follow-up of these patients.

If family physicians are expected to play a greater role in cancer care, this responsibility must be supported through adequate medical education and resources. Currently, there is a paucity of information available to guide family physicians in their follow-up care of patients treated for prostate cancer. This article will review the current resources available and provide suggestions for appropriate monitoring of prostate cancer patients.

Sources of information

MEDLINE (1966 to September 2006) was searched with the following medical subject headings: prostate cancer. mp or prostate neoplasms; practice guideline or care map or follow-up; and primary care or family physician. EMBASE (1980 to October 2006) was searched with the following Excerpta Medica tree terms: prostate cancer.mp or prostate cancer; practice guidelines, care map, or follow-up; and primary care or family physician. Results were all limited to English-language studies involving humans from the years 1990–2006, excepting any entries concerned with screening.

The National Guidelines Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov), the Canadian Medical Association Infobase of clinical practice guidelines (http://mdm.ca/cpgsnew/cpgs/index.asp), the Guidelines Advisory Committee (http://gacguidelines.ca/), the Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences (www.ices.on.ca), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (www.nccn.org), Cancer Care Ontario (www.cancercare.on.ca), and the National Cancer Institute (www.cancer.gov) websites were searched. Additionally, the Canadian Urological Association (www.cua.org), the American Urological Association (www.auanet.org/guide lines), the College of Family Physicians of Canada (www.cfpc.ca), the American Academy of Family Physicians (www.aafp.org), the American Society of Clinical Oncologists (www.asco.org), and the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (www.astro.org) websites were investigated.

All relevant guidelines found were level III evidence. The American Urological Association website had a PSA testing best practice policy,3 which was also cited by the American Academy of Family Physicians web-site. It explored PSA testing as a screening, staging, and follow-up tool for primary care physicians and urologists. We expand on this resource by providing up-to-date information that focuses solely on family physicians’ use of PSA levels for posttreatment monitoring of prostate cancer patients. Other resources found4–8 were skewed toward specialist management of prostate cancer.

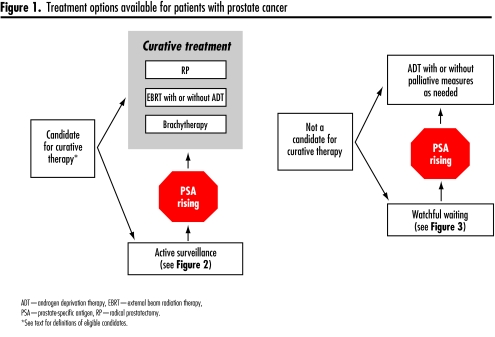

Treatments

There are many treatment options available to men with diagnoses of prostate cancer, depending on the stage of disease and their health status and life expectancy. Men with local disease are candidates for either active surveillance or curative therapy, including radical prostatectomy (RP), external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), or brachytherapy (Figure 1). Intermediate- to high-risk patients (PSA ≥ 15 ng/mL, Gleason score 8–10) within this cohort who are receiving EBRT are given the option of adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) to accompany their radiation treatment. Patients with systemic disease or those with substantial medical comorbidities (life expectancy < 10 years) are more appropriately treated with watchful waiting, ADT, and other palliative measures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treatment options available for patients with prostate cancer

PSA kinetics

Prostate-specific antigen is a glycoprotein found almost exclusively in the epithelial cells of the prostate, and it functions not only as a screening test for prostate cancer, but also as a prognostic factor pretreatment3,9 and a posttreatment surveillance tool.

An increasing PSA level after curative therapy is termed a biochemical recurrence (BCR). Approximately one-third to half of patients will experience BCR during the course of their follow-up, regardless of modality of treatment.10,11 The significance of a BCR is in itself unclear, as not all men who have experienced BCRs will go on to experience metastatic disease.12 In one study, fewer than one-third of patients with BCR after RP developed systemic recurrence.13 In those patients who progress, BCR usually predates metastatic disease progression by an average of 7 years and prostate-cancer specific mortality by 15 years.14 Therefore it is useful in allowing enough lead time to implement effective salvage therapeutic strategies in those patients whose recurrences are deemed to be local (Table 1). The definition of BCR varies depending on the type of treatment that a patient has undergone and is continually being reevaluated as more data become available.

Table 1.

Factors that suggest biochemical recurrence (BCR) represents local vs distant disease after primary treatment with surgery or radiotherapy

| FACTOR | LOCAL RECURRENCE | DISTANT RECURRENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Initial pathology | Gleason score < 7 | Gleason score ≥ 7 |

| Positive surgical margin | Extra-prostatic involvement | |

| No nodal involvement | Nodal involvement | |

| Time to BCR after treatment | > 1–2 y | < 1 y |

| Pretreatment PSA level | < 10 ng/mL | > 10 ng/mL |

| PSADT | > 12 mo | < 6–12 mo |

PSA—prostate-specific antigen, PSADT— prostate-specific antigen doubling time.

Recent studies have shown that the speed at which PSA rises, or the PSA doubling time (PSADT), is one of the strongest predictors of clinical progression and cancer mortality.11 If the PSA is doubling slowly (> 12 months), the probability is high that the recurrence is local.3,10 When PSA doubling time is shorter than 6 months, however, it is more consistent with disseminated disease.3,10 Tools to calculate PSADT are available on-line (eg, www.echurology.co.uk/psadt.html).

Monitoring schedules and tools

Follow-up of patients with prostate cancer should consist of management of treatment-related side effects, as well as surveillance for disease recurrence. Patients with lower risk disease (no nodal or metastatic disease) can be followed every 3 to 4 months for the first year post-treatment, and then every 6 months for 4 years, proceeding to lifetime annual follow-up. Higher risk patients (those with nodal or metastatic disease) should be seen every 3 to 6 months as needed (Table 2).7

Table 2.

Proposed schedule of follow-up for patients after prostate cancer treatment

| LOW RISK | HIGH RISK |

|---|---|

|

|

Disease surveillance should entail a clinical evaluation in concert with PSA measurements and optional digital rectal examinations (DRE). Clinical evaluation should attempt to highlight any new systemic symptoms, such as weight loss and fatigue, as well as more localized symptoms, such as bone pain, which might be suggestive of increased disease activity.

The utility of DRE in follow-up after radiotherapy has been questioned, as scar tissue can be difficult to differentiate from neoplastic nodules, and any residual tumour might not be palpable.15 In fact, it has been found that any recurrent nodules are noted within a background of an increasing PSA level, and therefore DRE can be safely omitted.16 Likewise, the relevance of transrectal ultrasound and biopsy is unclear post-treatment, as up to 80% of patients can have positive biopsies after radiotherapy but no other suggestion of active disease.10 These tests are therefore not advisable as standard protocol, leaving PSA testing as the primary tool for monitoring disease recurrence.

Prostate-specific antigen values can also be used to guide when radiologic investigations are appropriate. Bone metastases rarely occur before PSA levels rise above 20 ng/mL,9 and computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have been found to be low yield when PSA is lower than 25 ng/mL.3 There is believed to be little utility in ordering any imaging studies in an asymptomatic patient with PSA < 30 ng/mL,7 but a patient with bone pain should have a bone scan done irrespective of PSA level.

Follow-up: expected PSA responses based on treatment

Active surveillance

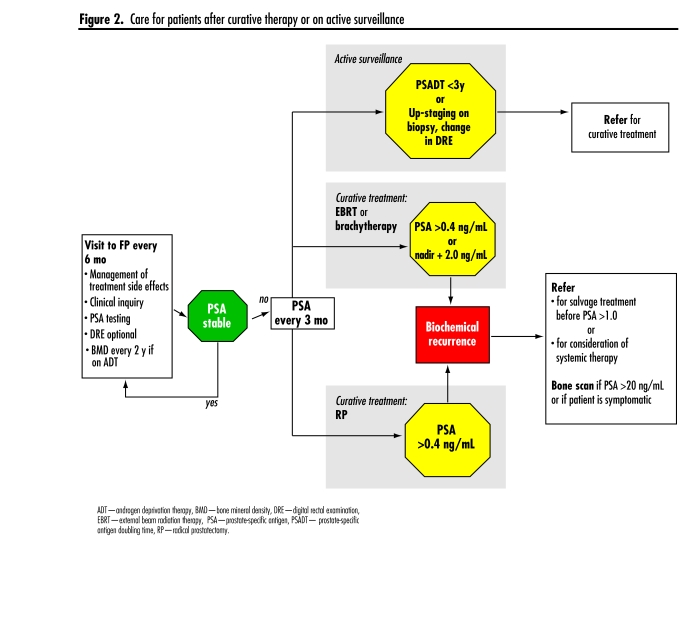

Patients being monitored under active surveillance are those who are still candidates for curative therapy but opt not to pursue immediate treatment owing to the indolent characteristics of their tumours, those who have PSADTs of more than 3 years, or those who are older or who have medical comorbidities. These patients should be followed with PSA testing every 6 months, and curative therapy should be considered if there is evidence of escalating PSADTs (Figure 2). Current practice often includes periodic repeat biopsies to ensure that there is no up-staging of disease.17

Figure 2.

Care for patients after curative therapy or on active surveillance

Radical prostatectomy

Surgical excision of the prostate should remove all the PSA-producing tissue within the body. It is therefore expected that after RP, PSA should decline to undetectable levels within 3 to 6 weeks (Table 3).10,14,18 Any persistent elevation of PSA beyond this time is suggestive of residual local or distant disease,10 but can also reflect the presence of benign glandular tissue at the resection margin. Serial PSA testing will remain static in the latter case. Once PSA levels reach 0.4 ng/mL, it is considered a true BCR.14 Several studies, however, have suggested that the more conservative value of 0.2 ng/mL should be employed as a threshold, as beyond this level PSA begins to rise exponentially (Figure 2).7,13

Table 3.

expected PSA values posttreatment

| VALUE | RADICAL PROSTATECTOMY | EXTERNAL BEAM RADIATION THERAPY | BRACHYTHERAPY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to nadir | 3–6 wk | 18–36 mo | > 36 mo |

| Expected nadir | < 0.10 ng/mL | < 0.2–0.5 ng/mL | < 0.2–0.5 ng/mL |

| Biochemical recurrence | 0.2–0.4 ng/mL | Nadir + 2.0 ng/mL | Nadir + 2.0 ng/mL |

Patients with confirmed BCRs, anticipated life spans of more than 10 years, and clinical pictures suggestive of local recurrence (Table 1) might be candidates for local salvage treatment; EBRT can be offered to these men.7 This should be performed before the PSA level rises to 0.6 ng/mL,14 although 1.0 to 1.5 ng/mL could also be an appropriate level.19 A Canadian consensus group addressing the appropriate cutoff value is currently under development. For those patients who have BCRs and clinical pictures more consistent with meta-static disease, salvage radiotherapy would not be indicated, and standard management would include the discussion of early versus delayed ADT.

External beam radiotherapy

Prostate-specific antigen levels are not expected to decline to undetectable levels after EBRT, as prostate tissue remains in situ. It is expected, however, that there should be a substantial decline in PSA level to a nadir level, the value of which is contested, but generally held to be anywhere from 0.2 ng/mL19 to 0.5 ng/mL (Table 3).3 Each treated individual will have a nadir characterized by the lowest PSA measurement recorded after treatment completion. Generally, at 3 months of follow-up the PSA level should be half of its pretreatment level. It can take as long as 18 to 36 months to reach the nadir value.14 The nadir value is predictive of treatment success, and values less than 0.5 ng/mL are consistent with a 5-year disease-free survival in 93% of patients, compared with only 26% of patients having disease-free status at 5 years when they have a nadir of greater than 1.0 ng/mL.20

There is a phenomenon termed PSA bounce that is seen in 10% to 30% of patients who have been treated with EBRT.14 The PSA bounce generally occurs within 9 months of treatment, but can occur up to 60 months after completion of therapy. It is a transitory PSA rise of at least 0.4 ng/mL, or a 15% rise in the previous PSA value, which resolves spontaneously.21 The etiology of this phenomenon is not well understood. In order to differentiate BCR from a bounce, the Phoenix definition of BCR—the nadir plus elevation of PSA by 2.0 ng/mL—has been developed (Figure 2).22 Salvage procedures, such as RP and cryotherapy can be offered to patients who have EBRT and have documented BCRs with local disease.7

Brachytherapy

Prostate-specific antigen response after brachytherapy is not as well described. It appears that a PSA bounce might be more common among patients treated with brachytherapy, occurring in up to 32% to 46% of men.23,24 In some studies, patients experiencing PSA bounces were less likely to have BCRs.23 Currently, the same definitions of BCR are employed as in EBRT (Table 3, Figure 2).

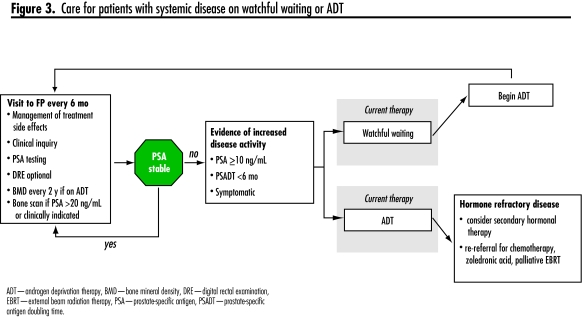

Watchful waiting

Patients with incurable disease can be observed with watchful waiting, and ADT can be initiated as disease activity begins to escalate. There is no clear indication of the appropriate time at which to initiate ADT. Some clinicians use an absolute PSA value, while others take into consideration the PSADT (< 6 months), but it is often the patient’s comfort level with watchful waiting versus treatment and its associated side effects that dictates timing of treatment.20 There is increasing evidence that patients receiving immediate ADT treatment fare better in terms of quality of life and survival than those patients treated at the time of symptomatic progression (Figure 3).25–27 The optimal timing for the initiation of ADT, however, remains elusive.

Figure 3.

Care for patients with systemic disease on watchful waiting or ADT

Androgen deprivation therapy can be accomplished either by bilateral orchiectomy or with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. Peripherally acting nonsteroidal antiandrogens are used for patients being started on gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists to prevent disease flare due to the initially increased testosterone levels. The benefit of more prolonged use of these oral antiandrogens to block any adrenal androgen activity on prostate cancer cells in addition to medical or surgical castration (maximum androgen blockade) is controversial. There are ongoing studies comparing the cancer control of intermittent and continuous ADT.

Androgen independence is inevitable for patients on ADT, but its timing varies across patients. This is reflected in a rise in PSA after anywhere from 18 to 64 months on hormonal therapy.28 The median survival time after this point is 1 to 4.5 years, depending on the presence of documented metastases at the time of the PSA rise.29 Treatment options include secondary hormonal manipulations such as starting or discontinuing oral antiandrogens. Palliative radiotherapy is very useful for the commonly discovered bony metastases and recent studies have suggested a protective benefit to bone with zoledronic acid.30 Men with hormone refractory prostate cancer and a good performance status might also benefit from chemotherapy using mitoxantrone or docetaxel (Figure 3).31

Case resolutions

Mr A. has evidence of BCR and needs rapid referral for potential EBRT salvage therapy.

Mr P. has not met the criteria for BCR and is likely experiencing a PSA bounce. He should continue regular monitoring of his PSA levels and symptoms.

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is a common disease, and current screening and treatment modalities are resulting in a high survival rate. Patients are, however, still at substantial risk for disease recurrence and, as there are effective salvage treatments available, require careful monitoring. This often falls within the domain of the family physician; however, there are few resources available to assist primary caregivers in this role. We present a summary of expected PSA response to disease treatment, as well as an outline of appropriate clinical inquiry and investigations to help guide family physicians.

Levels of evidence

Level I: At least one properly conducted randomized controlled trial, systematic review, or meta-analysis

Level II: Other comparison trials, non-randomized, cohort, case-control, or epidemiologic studies, and preferably more than one study

Level III: Expert opinion or consensus statements

Prostate cancer resources

Prostate Cancer Research Foundation of Canada (information for patients and families, including a Prostate Owner’s Manual; funding opportunities for researchers) www.prostatecancer.ca

Canadian Cancer Society (check under “prostate cancer” for information) www.cancer.ca

Canadian Prostate Cancer Network (prostate cancer support group information) www.cpcn.ca

Prostate Cancer Foundation (information for patients and families) www.prostatecancerfoundation.org

Acknowledgment

Salary support for Dr Wilkinson was received from the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing is the primary tool for surveillance for disease recurrence in patients with prostate cancer. The usefulness of digital rectal examination has been questioned.

The pattern of the fall and possible rise in PSA levels posttreatment differs by treatment modality. If PSA levels reach 0.2–0.4 ng/mL after prostatectomy (or the nadir PSA level plus 2.0 ng/mL after radiation therapy or brachytherapy), this is considered a true biochemical recurrence.

A PSA “bounce” can occur posttreatment, which must be differentiated from a biochemical recurrence.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

La principale façon de déceler une récidive de cancer prostatique est le dosage de l’antigène prostatique spécifique (PSA). L’utilité du toucher rectal est remise en question.

Le modèle de la chute et de l’éventuelle remontée du PSA après traitement diffère selon la modalité thérapeutique. On parlera d’une véritable récidive biochimique si le niveau du PSA atteint 0,2–0,4 ng|/mL après une prostatectomie (ou 2,0 ng|/mL de plus que le nadir observé après radiothérapie ou curiethérapie).

Le rebond du PSA parfois observé après le traitement ne doit pas être confondu avec une récidive biochimique.

Footnotes

Competing interests

None declared

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Canadian Cancer Society, National Cancer Institute of Canada, Statistics Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian cancer statistics 2006. Toronto, ON: National Cancer Institute of Canada; 2006. [Accessed 2008 January 11]. Available from: www.ncic.cancer.ca/vgn/images/portal/cit_86751114/31/23/935505938cw_2006stats_en.pdf.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Giudice L, Bondy SJ, Chen Z, Maaten S. Physician care of cancer patients. In: Jaakkimainen L, Upshur R, Klein-Geltink JE, Leong A, Maaten S, Schultz SE, et al., editors. Primary care in Ontario: ICES atlas. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. pp. 161–74. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Urological Association. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) best practice policy. Oncology. 2000;14(2):267–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology version 2. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2005. [Accessed 2008 January 11]. Available from: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/prostate.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawashima A, Choyke PL, Bluth EI, Bush WH, Jr, Casalino DD, Francis IR, et al. Expert panel on urologic imaging. Posttreatment follow-up of prostate cancer. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kataja VV, Bergh J. ESMO minimum clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(Suppl 1):i34–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aus G, Abbou CC, Bolla M, Heidenreich A, Schmid HP, van Poppel H, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2005;48:546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagliardi AR, Fleshner N, Langer B, Stern H, Brown AD. Development of prostate cancer quality indicators: a modified Delphi approach. Can J Urol. 2005;12(5):2808–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naito S. Evaluation and management of prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35(7):365–74. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitchner J. The management of prostate cancer in patients with a rising prostate-specific antigen level. BJU Int. 2000;86:181–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sengupta S, Blute ML, Bagniewski SM, Myers RP, Bergstralh EJ, Leibovich BC, et al. Increasing prostate specific antigen following radical prostatectomy and adjuvant hormonal therapy: doubling time predicts survival. J Urol. 2006;175:1684–90. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00978-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duchesne GM, Millar JL, Moraga V, Rosenthal M, Royce P, Snow R. What to do for prostate cancer patients with a rising PSA—a survey of Australian practice. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(4):986–91. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1991;281:1591–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephenson AJ, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, Dotan ZA, Bianco FJ, Jr, Lilja H, et al. Defining biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: a proposal for a standardized definition. J Clin Onc. 2006;24(24):3973–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crook JM, Choan E, Perry GA, Robertson S, Esche BA. Serum prostate-specific antigen profile following radiotherapy for prostate cancer: implications for patterns of failure and definition of cure. Urology. 1998;51:566–72. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00650-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnstone PA, McFarland JT, Riffenburgh RH, Amling CL. Efficacy of digital rectal examination after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;166:1684–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klotz L. Active surveillance with selective delayed intervention for favorable risk prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2006;24(1):46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Critz FA, Williams WH, Holladay CT, Levinson AK, Benton JB, Holladay DA, et al. Posttreatment PSA ≤0.2 ng/mL defines disease freedom after radiotherapy for prostate cancer using modern techniques. Urology. 1999;54:968–71. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00346-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boccon-Gibod L, Djavan WB, Hammerer P, Hoeltl W, Kattan MW, Prayer-Galetti T, et al. Management of prostate-specific antigen relapse in prostate cancer: a European consensus. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:382–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Critz FA, Levinson AK, Williams WH, Holladay DA, Holladay CT. The PSA nadir that indicates potential cure after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Urology. 1997;49:322–6. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catton C, Milosevic M, Warde P, Bayley A, Crook J, Bristow R, et al. Recurrent prostate cancer following external beam radiotherapy: follow-up strategies and management. Urol Clin North Am. 2003;30(4):751–63. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(03)00051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H, Jr, Schellhammer P, Shipley WU, Sokol GH, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toledano A, Chauveinc L, Flam T, Thiounn N, Solignac S, Timbert M, et al. PSA bounce after permanent implant prostate brachytherapy may mimic a biochemical failure: a study of 295 patients with a minimum 3-year followup. Brachytherapy. 2006;5(2):122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciezki JP, Reddy CA, Garcia J, Angermeier K, Ulchaker J, Mahadevan A, et al. PSA kinetics after prostate brachytherapy: PSA bounce phenomenon and its implications for PSA doubling time. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(2):512–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medical Research Council Prostate Cancer Working Party Investigators Group. Immediate versus deferred treatment for advanced prostate cancer: initial results of the Medical Research Council trial. Br J Urol. 1997;79:235–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1997.d01-6840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messing EM, Manola J, Sarosdy M, Wilding G, Crawford ED, Trump D. Immediate hormonal therapy compared with observation after radical pros-tatectomy and pelvic lymphadenopathy in men with node-positive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1781–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912093412401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirth MP, See WA, McLeod DG, Iversen P, Morris T, Carroll K, et al. Bicaltamide 150 mg in addition to standard care in patients with localized or locally advanced prostate cancer: results from the second analysis of the early prostate cancer program at median followup of 5.4 years. J Urol. 2004;172:1865–70. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000140159.94703.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oefelein MG, Ricchiuti VS, Conrad PW, Goldman H, Bodner D, Resnick MI, et al. Clinical predictors of androgen-independent prostate cancer and survival in the prostate-specific antigen era. Urology. 2002;60:120–4. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01633-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharifi N, Dahut WL, Steinberg SM, Figg WD, Tarassoff C, Arlen P, et al. A retrospective study of the time to clinical endpoints for advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2005;96:985–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pienta KJ, Smith DC. Advances in prostate cancer chemotherapy: a new era begins. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:300–18. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.5.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]