Abstract

Patch clamp and fura-2 fluorescence were employed to characterize receptor-mediated activation of recombinant Drosophila TrpL channels expressed in Sf9 insect cells. TrpL was activated by receptor stimulation and by exogenous application of diacylglycerol (DAG) or poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Activation of TrpL was blocked more than 70% by U73122, suggesting that the effect of these agents was dependent upon phospholipase C (PLC).

In fura-2 assays, extracellular application of bacterial phosphatidylinositol (PI)-PLC or phosphatidylcholine (PC)-PLC caused a transient increase in TrpL channel activity, the magnitude of which was significantly less than that observed following receptor stimulation. TrpL channels were also activated in excised inside-out patches by cytoplasmic application of mammalian PLC-β2, bacterial PI-PLC and PC-PLC, but not by phospholipase D (PLD). The phospholipases had little or no effect when examined in either whole-cell or cell-attached configurations.

TrpL activity was inhibited by addition of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to excised inside-out membrane patches exhibiting spontaneous channel activity or to patches pre-activated by treatment with PLC. The effect was reversible, specific for PIP2, and was not observed with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), PI, PC or phosphatidylserine (PS). However, antibodies against PIP2 consistently failed to activate TrpL in inside-out patches.

It is concluded that both the hydrolysis of PIP2 and the generation of DAG are required to rapidly activate TrpL following receptor stimulation, or that some other PLC-dependent mechanism plays a crucial role in the activation process.

Stimulation of isolated Drosophila photoreceptor cells by light causes an increase in membrane conductance that requires phospholipase C (PLC) (Bloomquist et al. 1988) and reflects the activity of both the transient receptor potential channel (Trp) and the Trp-like channel (TrpL) (Niemeyer et al. 1996). It was originally thought that light-activated channels were localized in the photoreceptor cell to the base of the microvilli of the rhabdomere (Pollock et al. 1995). The close proximity of the Trp channels to the submicrovilli cisternae, i.e. the internal Ca2+ storage compartment, led to the suggestion that an inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins(1,4,5)P3)-induced Ca2+ release activated Trp and TrpL via a capacitative Ca2+ entry (CCE) mechanism analogous to receptor-mediated activation of Ca2+ entry in mammalian non-excitable cells (Hardie & Minke, 1993). Subsequent studies, however, have shown that the microvilli, which are 1-2 μm long and 50 nm wide, have Trp, TrpL and PLC located along their entire length (Niemeyer et al. 1996; Chevesich et al. 1997; Tsunoda et al. 1997), placing most of the ion channels at a considerable distance from the nearest internal Ca2+ store. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor is not required for activation of Trp or TrpL by light (Acharya et al. 1997; Raghu et al. 2000).

Heterologous expression of TrpL gives rise to Ca2+-permeable, non-selective cation currents that are unaffected by depletion of the internal Ca2+ stores by thapsigargin, but are activated following stimulation of membrane receptors linked to phosphoinositide turnover (Vaca et al. 1994; Hu & Schilling, 1995; Harteneck et al. 1995; Dong et al. 1995; Obukhov et al. 1996; Kunze et al. 1997). Trp and TrpL were the first cloned members of what now appears to be a large family of ion channels found in a variety of mammalian non-excitable and excitable tissues. To date, seven mammalian Trp homologues have been identified (Wes et al. 1995; Zhu et al. 1995, 1996; Philipp et al. 1996; Boulay et al. 1997; Okada et al. 1998, 1999; Liman et al. 1999). Heterologous expression studies have shown that receptor-mediated changes in [Ca2+]i and whole-cell membrane currents are increased in cells expressing mammalian Trp3, Trp4, Trp5, Trp6 and Trp7 (Zitt et al. 1997, 1998; Boulay et al. 1997; Okada et al. 1998, 1999; Hurst et al. 1998; Hofmann et al. 1999; Schaefer et al. 2000). As with the Drosophila homologues, regulation of the mammalian Trp channels by receptor stimulation appears to require phosphoinositide hydrolysis since this regulation can be blocked by U73122, a specific inhibitor of PLC (Zhu et al. 1998; Okada et al. 1999; Kamouchi et al. 1999; Schaefer et al. 2000). The link between PLC and channel activation, however, remains obscure. Although several studies demonstrate that mammalian Trp channels are not activated by depletion of internal Ca2+ stores, at least when heterologously expressed (Zitt et al. 1997; Boulay et al. 1997; Zhu et al. 1998; Sinkins et al. 1998; Okada et al. 1998, 1999; Hurst et al. 1998; Hofmann et al. 1999; Kamouchi et al. 1999; Schaefer et al. 2000), other studies have shown that Trp4 and Trp5 may function as store-operated channels (Philipp et al. 1996, 1998; Warnat et al. 1999). Furthermore, studies using antisense oligonucleotides directed against trp1 and/or trp3 suggest they may play a role in CCE in HEK cells (Wu et al. 2000) and rat submandibular epithelial cells (Liu et al. 2000). Trp3, Trp5 and Trp7 may also be activated by a rise in [Ca2+]iper se (Zitt et al. 1997; Okada et al. 1998, 1999; but see Kamouchi et al. 1999). One consistent result is that Drosophila TrpL and three mammalian Trp homologues, Trp3, Trp6 and Trp7, appear to be activated by exogenous application of diacylglycerols (DAGs) or poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (Okada et al. 1999; Hofmann et al. 1999; Chyb et al. 1999). However, it is not clear whether the effects of DAGs or PUFAs are through direct interaction with the channels or are indirect via some other membrane-associated mechanism(s). Furthermore, the physiological concentration of DAG or PUFA generated in the membrane following receptor stimulation and its relationship to pharmacological doses experienced by the channels during exogenous application of these agents remains unclear.

The consequences of PLC activation may not be limited to the downstream effects of Ins(1,4,5)P3, DAG or Ca2+. Studies have shown that the activity of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger and several K+ channels (Hilgemann & Ball, 1996; Zheng & Makielski, 1997; Huang et al. 1998; Sui et al. 1998) can be regulated in excised membrane patches by phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), suggesting an important role for this minor membrane lipid in the direct regulation of membrane-associated ion transporters. Thus, the effect of PLC on the Trp family of channels may reflect, at least in part, alterations in PIP2 levels following activation of membrane receptors.

Because of the complexity of the PLC/Ins(1,4,5)P3 signalling pathway, it is difficult to distinguish between channel regulatory or modulatory mechanisms and the initial PLC-dependent activation step. To address this issue, the experiments of the present study compare and contrast receptor/PLC-dependent regulation of TrpL channels measured using fura-2 fluorescence in intact cells with results obtained using patch-clamp techniques. With regard to the latter, TrpL channels were recorded in the cell-attached mode (intact cells), the whole-cell configuration (dialysed intact cell), and at the single channel level in excised inside-out membrane patches. For these studies, TrpL was expressed in Sf9 insect cells using baculovirus expression vectors. The Sf9 cell has several advantages over other expression systems for the study of ion channels involved in Ca2+ signalling. Importantly, this method of expression involves viral infection (rather than transfection). Host cell protein synthesis decreases immediately after infection and is essentially zero after 24 h (O’Reilly et al. 1992). Thus, problems associated with up-regulation or co-expression of endogenous proteins is minimized, whereas the probability of measuring homomeric channels is enhanced. Furthermore, Sf9 cells have the molecular machinery necessary for receptor-mediated Ca2+ signalling; responses essentially identical to those observed in mammalian cells are seen in Sf9 cells stimulated with either receptor agonists or thapsigargin (Hu et al. 1994). Lastly, Sf9 cells lack endogenous voltage-gated and Ca2+-activated channels, which potentially may complicate data analysis in other expression systems such as the Xenopus oocyte, CHO cells or HEK cells. The results of the present study demonstrate that receptor-mediated activation of TrpL (1) is dependent upon the activity of PLC, (2) is influenced by DAG and/or PUFAs, at least in part through a PLC-dependent mechanism, and (3) may reflect hydrolysis of PIP2 in addition to the generation of DAG. However, neither hydrolysis of PIP2 nor the release of DAG alone can fully account for receptor-induced activation of TrpL.

METHODS

Solution and reagents

Mes-buffered saline (MBS) contained the following: 10 mm NaCl, 60 mm KCl, 17 mm MgCl2, 10 mm CaCl2, 4 mmd-glucose, 110 mm sucrose, 0.1% bovine serum albumin and 10 mm Mes, pH adjusted to 6.2 at room temperature with Trizma-base. The total osmolarity of MBS was ≈340 mosmol l−1. Nominally Ca2+-free MBS was identical to MBS with the exception that CaCl2 was isosmotically replaced by MgCl2. The free Ca2+ concentration in nominally Ca2+-free MBS was 1.1 μm determined using fura-2. For experiments involving DAGs and PUFAs, bovine serum albumin was omitted from MBS. Phospholipase D (PLD), phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC (PI-PLC), phosphatidylcholine-specific PLC (PC-PLC), linolenic acid (LNA), linoleic acid (LLA), arachidonic acid (AA), oleic acid, stearic acid and anandamide (Anand) were obtained from Sigma. [3H]Inositol and [3H]choline were obtained from New England Nuclear (Boston, MA, USA). Thapsigargin, U73122, U73343, 1-stearoyl-2-arachidonyl-glycerol (SAG), bradykinin (BK), 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) and phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (TPA) were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-PIP2 antibody was obtained from Perceptive Biosystems (Framingham, MA, USA). PIP2 was obtained from Calbiochem or Boehringer-Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and all other lipids were obtained from Sigma. All phospholipids were prepared from chloroform stock solutions as follows. The chloroform was evaporated from an aliquot of lipid solution under nitrogen followed by two rounds of solubilization in pentane and evaporation under nitrogen. Following the final evaporation step, the lipid was dissolved in DMSO to obtain a 1000 x stock solution. For use in electrophysiological experiments, the lipid-DMSO solution was diluted 50-fold with sodium gluconate and sonicated on ice (3 x for 10 s) using a Fisher 550 Sonic Dismembrator on a power setting of 2.5 immediately before addition to the recording chamber. For both electrophysiological and fura-2 experiments, SAG, OAG, AA, LNA, LLA, TPA, anandamide stearic acid and oleic acid were added directly to the bath solution from 1000 x stocks in either DMSO or ethanol. Mammalian PLC-β2 was a generous gift from Dr Alan V. Smrcka (University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, USA). As will be seen in the Results section, this enzyme activates TrpL channels recorded in excised inside-out patches. Because this enzyme was available in limited supply, the minimum effective concentration was determined in preliminary studies. This concentration was employed for all subsequent experiments. We also examined the ability of this enzyme to release PIP2 from liposomes (phosphatidylethanolamine (PE):PIP2, 10:1) supplemented with [inositol-2-3H(N)]phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. PLC-β2 (0.5 μg ml−1) released 67% of the incorporated radiolabel within 10 min at room temperature. As a control, bacterial PI-PLC (0.5 U ml−1) had no effect. This experiment demonstrates that the PLC-β2 was active under our experimental conditions, and that PIP2 was not a substrate for bacterial PI-PLC, as previously reported (Noh et al. 1995).

Cell culture

Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) cells were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA) and cultured as previously described (O’Reilly et al. 1992; Hu et al. 1994) using Grace's insect medium supplemented with 2% lactalbumin hydrolysate, 2% yeastolate solution, 2 mml-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA).

Generation of recombinant baculovirus

The cDNA encoding Drosophila TrpL or human B2 bradykinin receptor was subcloned into the baculovirus transfer vector pVL1392 using standard techniques. Recombinant baculoviruses were produced using the BaculoGold transfection kit (PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA) as described in the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Recombinant viruses were plaque purified and amplified 2-4 times to obtain a high titre viral stock solution. The virus was stored at 4oC under sterile conditions until use.

Infection of Sf9 insect cells with recombinant baculovirus

Sf9 cells in Grace's medium were plated into 100 mm plastic tissue culture dishes or onto glass coverslips (≈105 cells cm−2). Following incubation for 30 min, an aliquot of viral stock was added (multiplicity of infection was ≈10) and the cells were maintained at 27oC in a humidified air atmosphere. Unless otherwise indicated, cells were used at 27-32 h post-infection.

Measurement of cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i)

[Ca2+]i was measured in Sf9 cells at 22oC using the fluorescent indicator fura-2, as previously described (Hu et al. 1994; Hu & Schilling, 1995). Calibration of the fura-2 associated with the cells was accomplished using Triton lysis in the presence of a saturating concentration of Ca2+ followed by addition of EGTA (pH 8.5). [Ca2+]i was calculated by the equation of Grynkiewicz et al. (1985) using a Kd value for Ca2+ binding to fura-2 of 278 nm for 22°C (Shuttleworth & Thompson, 1991). In some experiments [Ba2+]i was estimated using the fura-2 fluorescence ratio (excitation wavelengths of 350 and 390 nm) as previously described (Schilling et al. 1989; Hu & Schilling, 1995). Unless otherwise indicated, the results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Electrophysiological techniques

The patch-clamp technique was utilized in whole-cell, cell-attached and excised inside-out recording modes (Hamill et al. 1981; Vaca et al. 1994). All experiments were performed on single Sf9 cells at room temperature (≈22oC). Unless otherwise indicated, the bath and pipette solutions contained 100 mm sodium gluconate and 10 mm Mes, pH 6.5. The osmolarity was adjusted to 340 mosmol l−1 with mannitol. The free Ca2+ concentration in this solution, determined using fura-2 fluorescence, was 1.6 μm. In some experiments, bath Na+ was isosmotically replaced by N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG+). Bath solutions were exchanged by perfusion of the recording chamber (≈500 μl) at a rate of ≈8 ml min−1; complete bath exchange was accomplished within 15-20 s. Data were obtained using an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Pacer Scientific, Los Angeles, CA, USA) using pCLAMP 8.0 software, and recorded on VCR tape via a VR-10B Digital Data Recorder interface (Instrutech Corp., Great Neck, NY, USA) for subsequent computer analysis. To generate current-voltage (I-V) relationships, voltage ramps were applied every 5 or 12 s from -120 to +120 mV using a ramp rate of 1 mV ms−1. The holding potential between ramps was 0 mV. The figures show representative traces uncorrected for leak currents, but corrected for junction potentials, where appropriate. Blank spaces in single channel NPo (number of channels (N)x open probability (Po)) plots indicate solution changes or periods of time when voltage ramps were applied. For purposes of comparison, whole-cell currents were normalized to membrane capacitance and reported as picoamps per picofarad (pA pF−1). Single channel records were filtered at 2 kHz, digitized and analysed using pCLAMP 8.0 and EDA (Event Dynamic Analysis utility; Sui et al. 1998) software. The open probability of multi-channel patches was calculated from the idealized events binned at 1 s intervals. Where indicated, n equals the number of cells examined under each condition. Statistical differences were determined by Student's t test with Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons where appropriate (Winer, 1962) or by ANOVA followed by the appropriate secondary test; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

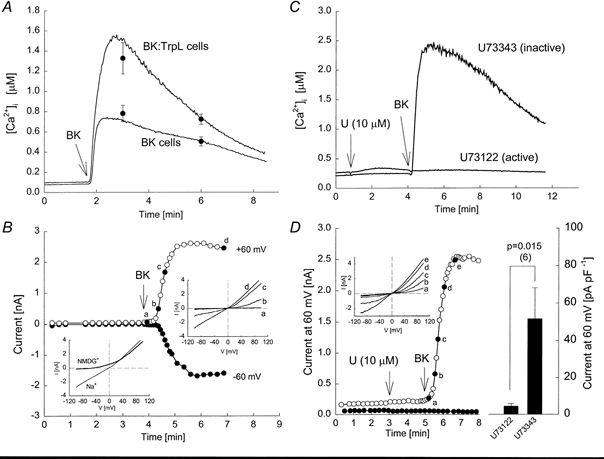

Activation of TrpL by receptor stimulation is dependent upon PLC

Previous studies in Sf9 cells have shown that heterologously expressed TrpL channels are activated following stimulation of G protein-coupled membrane receptors linked to activation of PLC (Hu & Schilling, 1995; Harteneck et al. 1995; Dong et al. 1995; Kunze et al. 1997). An example is shown in Fig. 1. Addition of bradykinin to Sf9 cells expressing the human B2 bradykinin receptor (BK cells) produced a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i from a resting mean ±s.e.m. value of 87 ± 9.7 to 780 ± 81 nm (Fig. 1A). In the continuous presence of receptor agonist, [Ca2+]i subsequently declined slowly with time back towards basal values. A similar time-dependent profile was seen in cells co-expressing both the B2 receptor and the TrpL channel (BK:TrpL cells), but both the peak and subsequent sustained components of the response were significantly increased (P < 0.006) compared to control BK cells. The effect of receptor stimulation on TrpL was also monitored electrophysiologically using patch-clamp techniques. As shown in Fig. 1B, addition of bradykinin during whole-cell recording produced a large, time-dependent increase in both inward and outward current in BK:TrpL cells. The currents, recorded in symmetrical sodium gluconate solutions, were slightly outwardly rectifying with a reversal potential close to 0 mV (Fig. 1B, upper inset). Changing the bath solution to one in which the Na+ was replaced with NMDG+ caused a shift in the reversal potential from 0 to approximately -50 mV and a dramatic reduction in inward current (Fig. 1B, lower inset). These results demonstrate that TrpL can be activated by receptor stimulation and that TrpL channels are relatively impermeable to the large cation NMDG+.

Figure 1. Effect of receptor stimulation on TrpL expressed in Sf9 cells.

Fura-2-loaded Sf9 cells were suspended in MBS. At the indicated time, bradykinin (BK, 50 nm; in this, and all subsequent figures, final concentrations are indicated) was added to the cuvette. A, two traces are shown superimposed; the lower trace was obtained from cells expressing the human B2 bradykinin receptor (BK cells) and the upper trace was obtained from BK-TrpL-co-expressing cells (BK:TrpL cells). The symbols shown represent means ±s.e.m.; n = 7-8. B, membrane currents were recorded from a BK:TrpL cell in symmetrical sodium gluconate solutions. The holding potential was 0 mV. At time 4 min, the bath was perfused with a solution containing bradykinin (50 nm) as indicated by the arrow. The current-voltage (I-V) relationships were generated by ramping the voltage over 200 ms from -100 to +100 mV. The I-V relationships obtained at the indicated times (a, b, c and d) are shown superimposed in the upper inset. Following measurement of the last I-V relationship, the Na+ in the bath solution was isosmotically replaced with NMDG+ and the I-V relationship obtained is shown in the lower inset. C, two traces are shown superimposed. BK:TrpL cells were suspended in MBS. BK was added at the indicated time in the presence of either 10 μm U73122 or 10 μm U73343, added at 50 s. D, whole-cell currents were recorded from BK:TrpL cells in response to BK added to the bath solution at the time indicated in the presence of U73343 (10 μm; ^) or U73122 (10 μm; •). Inset, complete I-V relationships from voltage ramps at the times indicated (a, b, c, d and e). The histogram on the right shows the mean ±s.e.m. peak current at +60 mV following addition of BK for each condition (n = 6).

To test for the involvement of PLC in the receptor-mediated activation of TrpL, we examined the effect of the PLC inhibitor U73122. This compound selectively inhibits mammalian PLC, but has no effect on bacterial PLC, bacterial or mammalian phospholipase A2 (PLA2), or adenylyl cyclase (Smith et al. 1990). Both U73122 and U73343, an analogue that has no effect on PLC (Smith et al. 1990), produced a small, transient increase in basal non-stimulated [Ca2+]i in BK:TrpL cells (Fig. 1C). In contrast to U73343, which had no effect, pretreatment with U73122 completely inhibited the bradykinin-induced change in [Ca2+]i. U73122 also blocked bradykinin-induced TrpL whole-cell membrane currents. As shown in Fig. 1D, addition of bradykinin during whole-cell recording produced a dramatic time-dependent increase in inward and outward TrpL current in the presence of U73343. Bradykinin had no effect on whole-cell current when applied after U73122. Neither U73122 nor U73343 had a significant effect on TrpL currents recorded before addition of bradykinin (see also Fig. 5). These results suggest that receptor-mediated activation of TrpL requires PLC.

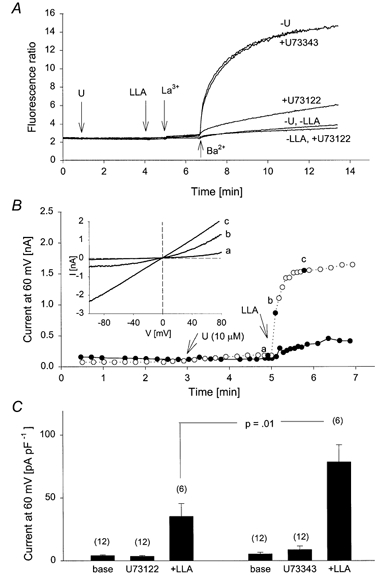

Figure 5. Effect of inhibition of PLC on LLA-induced activation of TrpL.

A, five traces are shown superimposed. TrpL cells were suspended in nominally Ca2+-free MBS. All traces received 10 μm La3+ to block the endogenous CCE pathway. TrpL channel activity was estimated from the fluorescence change following addition of Ba2+ (10 mm) to the bath solution at the indicated time in each trace. Addition of LLA (20 μm) and U73122 or U73343 (10 μm) at the respective arrows is as indicated on the right. B, whole-cell currents were recorded from TrpL cells in response to LLA added to the bath solution at the time indicated in the presence of U73343 (10 μm; ^) or U73122 (10 μm; •). Inset shows complete I-V relationships from voltage ramps at the times indicated (a, b and c). C, histogram shows the mean ±s.e.m. current at +60 mV before (base) and after addition of the indicated U-compound and LLA; n is shown in parentheses above each bar.

TrpL is activated by exogenous diacylglycerol

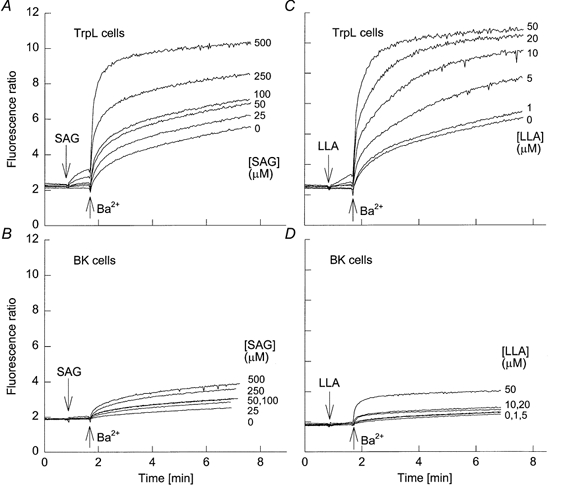

PLC generates two second messengers, Ins(1,4,5)P3 and DAG. Although we previously reported that Ins(1,4,5)P3 activates TrpL whole-cell currents (Dong et al. 1995), we found no effect of Ins(1,4,5)P3 on TrpL single channels recorded in excised inside-out patches (Kunze et al. 1997), suggesting that the effect of Ins(1,4,5)P3 was indirect. Recent reports suggest that TrpL can be activated by exogenous PUFAs (Chyb et al. 1999), and that three mammalian Trp homologues, Trp3, Trp6 and Trp7, can be transiently activated by exogenous DAGs (Okada et al. 1999; Hofmann et al. 1999). We therefore examined the effect of 1-stearoyl-2-arachidonyl-glycerol (SAG), and arachidonic (AA), linoleic (LLA) and linolenic (LNA) acids on Ba2+ influx in control BK cells and TrpL cells suspended in nominally Ca2+-free buffer. Ba2+ permeates the TrpL channel and produces spectral changes in fura-2 similar to those produce by Ca2+, but is a poor substrate for the membrane pumps responsible for removing Ca2+ from the cytosol (Schilling et al. 1989; Hu et al. 1994). Furthermore, Ba2+ does not activate TrpL (Estacion et al. 1999). At low concentrations, SAG had no effect on [Ca2+]i in either BK or TrpL cells. At the highest concentrations examined, a small, but detectable increase in [Ca2+]i was observed following addition of SAG to TrpL-expressing cells (Figs. 2A) in nominally Ca2+-free buffer, suggesting that SAG may release Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum. Consistent with this hypothesis, essentially identical profiles were obtained in extracellular buffer containing 0.5 mm EGTA to reduce [Ca2+]o to less than 50 nm (data not shown). Subsequent addition of Ba2+ to the extracellular buffer after SAG produced a dramatic increase in the fluorescence ratio, consistent with a large, stimulated Ba2+ influx; the SAG-stimulated Ba2+ influx in TrpL cells was greater than that seen for BK cells. Similar results were obtained with LLA (Fig. 2C and D), AA and LNA (data not shown). The EC50 value for SAG-, AA-, LNA- and LLA-induced changes in Ba2+ influx in TrpL cells was ≈200, 35, 5 and 5 μm, respectively. Because the responses to these agents were very large, we considered the possibility that the results reflect, at least in part, cell lysis. However, SAG (100 μm) and LNA (20 μm) had no effect on either YO-PRO or ethidium uptake in either BK or TrpL cells (data not shown). These vital dyes are normally excluded from the interior of intact cells, but gain access to cellular nucleotides following membrane disruption. Thus, the large effects of SAG and PUFAs on Ba2+ influx cannot be explained by a gross loss of membrane integrity.

Figure 2. Effect of SAG and LLA on Ba2+ influx.

A and B, six traces are shown superimposed. TrpL cells (A) or BK cells (B) were suspended in nominally Ca2+-free MBS. SAG was added to each trace at 50 s at the indicated final concentrations followed by Ba2+ (10 mm) at the times indicated. C and D, same protocol as in A and B, but with LLA added at the indicated concentrations at 50 s followed by Ba2+.

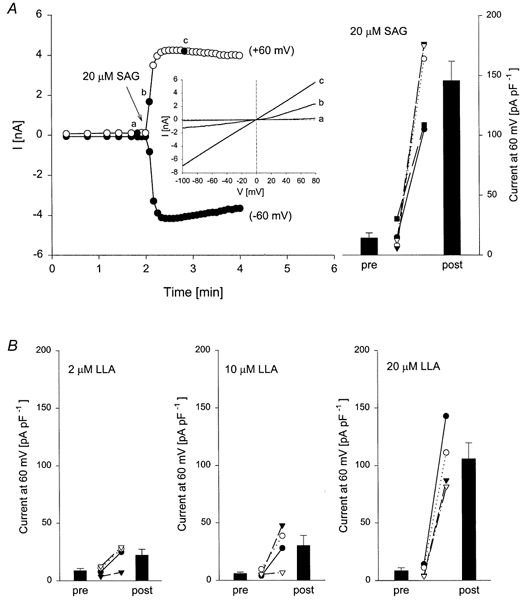

The effect of SAG on TrpL whole-cell currents is shown in Fig. 3. Addition of SAG to the bath solution during whole-cell recording produced a rapid and irreversible increase in membrane current in TrpL cells. The response was time dependent and current in TrpL cells peaked within 30 s following a challenge with 20 μm SAG. A similar, although smaller response was seen in control BK cells (n = 6) and in uninfected Sf9 cells (n = 4). In both of these control cell types, currents induced by SAG (10 μm) exhibited a linear I-V relationship and a reversal potential of 0 mV in symmetrical sodium gluconate solutions. Unlike TrpL currents (see Fig. 1), the currents activated by SAG in control cells were little affected by replacement of bath Na+ with NMDG+, which shifted the reversal potential by only -10 ± 1.6 mV; current density in the control cells stimulated by SAG was 33 ± 3.8 pA pF−1 at a membrane potential of 60 mV. Application of AA, LNA, LLA and oleic acid (but not stearic acid) produced a similar increase in whole-cell membrane current in TrpL cells; the effect of LLA was concentration dependent between 2 and 20 μm (Fig. 3B). The effects of various DAGs and PUFAs were also examined at the single channel level. SAG and LLA produced large increases in NPo when applied to the cytoplasmic surface of an inside-out patch from TrpL-expressing cells (Fig. 4A and B). Likewise, LNA, AA and oleic acid stimulated TrpL channel activity; OAG, TPA, Ins(1,4,5)P3, stearic acid and anandamide were without effect at the single channel level at the concentrations tested (Fig. 4C).

Figure 3. Effect of SAG and LLA on TrpL whole-cell currents.

A, whole-cell currents were recorded from TrpL cells in response to SAG (20 μm) added to the bath solution at the time indicated. The figure shows currents at +60 mV (^) and -60 mV (•) as a function of time and the inset shows complete I-V relationships from voltage ramps at the times indicated (a, b and c). The histogram on the right shows the mean ±s.e.m. current at 60 mV before (pre) and after (post) SAG; individual experiments are shown as different symbols. Similar experiments were performed with LLA and the mean ±s.e.m. current at 60 mV before (pre) and after (post) the indicated concentrations of LLA is shown in B along with the individual experiments.

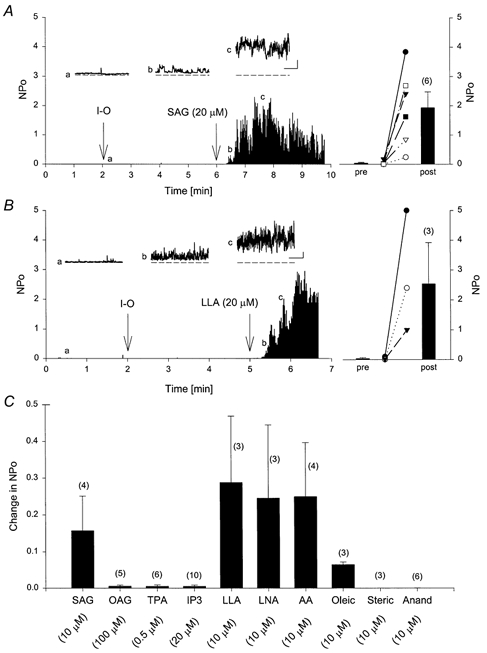

Figure 4. Effect of DAGs and PUFAs on TrpL single channels.

A and B, TrpL channels were initially recorded in cell-attached mode with sodium gluconate solution in both the pipette and bath. At 2 min, an inside-out (I-O) patch was obtained. SAG or LLA (20 μm) was added to the bath solution at the time indicated in each panel. The insets show channel activity on an expanded time base taken at the times indicated (a, b and c). Scale bars shown in the insets are 50 ms and 5 pA. The histogram on the right of each panel shows the mean ±s.e.m. NPo before (pre) and after (post) SAG and LLA. C, summary histogram of all experiments performed with the indicated agents reported as the change in NPo; n is shown in each histogram in parentheses above each bar.

Activation of TrpL by PUFAs is attenuated following inhibition of PLC

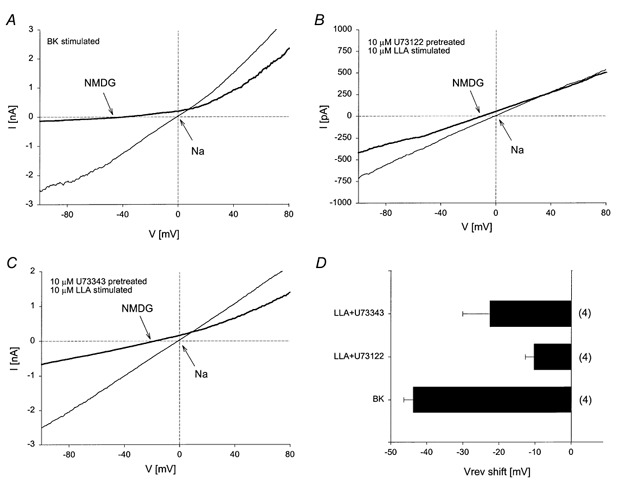

Since PUFAs have been reported to activate PLC (Hwang et al. 1996; Sekiya et al. 1999), we examined the effect of U73122 and U73343 on Ba2+ influx stimulated by LLA in TrpL cells suspended in nominally Ca2+-free buffer. As shown in Fig. 5A, U73343 had no effect on LLA-stimulated Ba2+ influx in TrpL cells, whereas U73122 inhibited it by 70-80%. SAG-induced Ba2+ influx in TrpL cells was also inhibited by U73122, but not U73343 (not shown). These results suggest that the effect of SAG and PUFAs on TrpL may occur, at least in part, via activation of PLC. To further explore this possibility, the effect of LLA on whole-cell TrpL currents was examined in the presence of the U-compounds (Fig. 5B and C). Application of U73343 or U73312 had no effect on basal currents recorded before application of LLA. However, U73122 produced a significant 50% reduction of LLA-induced current compared to that seen in the presence of U73343. To determine the extent to which TrpL contributed to the current activated by LLA, Na+ in the bath was exchanged for NMDG+ (Fig. 6). For comparison, similar experiments were performed in which TrpL was activated by bradykinin receptor stimulation. Activation of TrpL by bradykinin caused an increase in membrane current that was slightly outwardly rectifying. Upon exchanging bath Na+ with NMDG+, the reversal potential shifted to -43.7 ± 2 mV and the I-V relationship showed a pronounced reduction in inward current (Fig. 6A and D). Application of LLA in the presence of U73343 also increased membrane current in TrpL cells, but substantial inward current was recorded following exchange of bath Na+ with NMDG+ and the reversal potential shifted to only -22.5 ± 7 mV (Fig. 6C and D). In the presence of U73122, LLA produced a much smaller increase in membrane current as discussed above; however, changing bath Na+ to NMDG+ had almost no effect on the reversal potential and caused only a small reduction in inward current (Fig. 6B and D). The residual current seen in TrpL cells after LLA in the presence of U73122 was similar to LLA-induced currents in control cells. In both uninfected Sf9 cells (n = 3) and BK cells (n = 3), LLA (10 μm) produced an increase in current that exhibited a linear I-V relationship and a reversal potential of 0 mV in symmetrical sodium gluconate solutions. Replacement of bath Na+ with NMDG+ produced a shift in reversal potential of only -11.5 ± 4.2 mV; current density in control cells stimulated by LLA was 45 ± 9.5 pA pF−1 at 60 mV. These results suggest that LLA activates two current components in TrpL cells; one which is relatively impermeable to NMDG+ and presumably reflects TrpL, and another current, endogenous to the Sf9 cell, which is non-selective, allowing NMDG+ to permeate. Furthermore, activation of TrpL by LLA (i.e. the NMDG+-sensitive current) was substantially blocked by U73122 suggesting that the PUFAs affect TrpL indirectly by activation of PLC. Similar results with U73122 were obtained on SAG-induced whole-cell current in TrpL cells (not shown).

Figure 6. Comparison of BK-stimulated TrpL current with LLA-induced currents.

A, whole-cell current was recorded from BK:TrpL cells in symmetrical sodium gluconate solutions. Following activation of TrpL by bradykinin, Na+ in the bath solution was isosmotically replaced with NMDG+ and the I-V relationship obtained. B and C, whole-cell currents were recorded as in A from TrpL cells with the indicated treatments shown in each panel. D, histogram showing the mean ±s.e.m. reversal potential (Vrev) shift following the exchange of Na+ with NMDG+ in the bath solution for the conditions shown in A, B and C; n is shown in parentheses to the right of each bar.

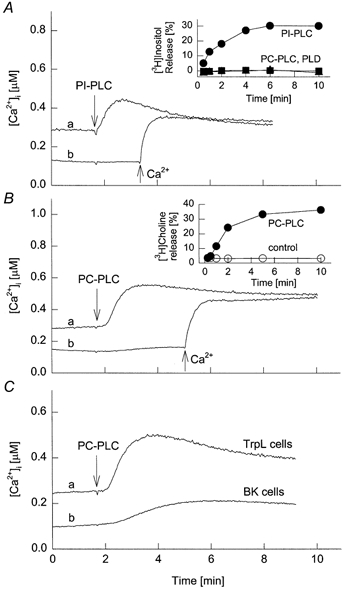

The results presented thus far suggest that pharmacological levels of PUFAs and SAG stimulate TrpL activity and that this reflects, at least in part, activation of PLC by exogenous application of these compounds. Since activation of endogenous PLC generates two major second messengers, determining the contribution of each following receptor activation in an intact cell is difficult. Furthermore, the amount of endogenous DAG or PUFA generated by receptor activation relative to that delivered by exogenous application of these agents remains unclear. We reasoned, however, that addition of PLC to the extracellular bath would generate endogenous DAG within the membrane and thus approximate the levels expected during receptor stimulation. Under these conditions, Ins(1,4,5)P3 and subsequent downstream signalling events would not be activated, thus allowing for the selective evaluation of DAG. Bacterial phosphatidylinositol-specific PLC (PI-PLC) is selective for PI and does not hydrolyse phosphatidylinoistol 4-phosphate (PIP) or PIP2 to any significant extent (Noh et al. 1995). To confirm that extracellularly applied PI-PLC is active, Sf9 cells were incubated with myo-[3H]inositol for 24 h to label the phosphatidylinositol pool. The cells were subsequently challenged with bacterial PI-PLC, mammalian phosphatidylcholine-specific PLC (PC-PLC) or PLD and the release of radioactivity monitored versus time (Fig. 7A, inset). Within 4 min of PI-PLC addition, ≈30% of the total radioactivity incorporated into the cell was released. In contrast, neither PC-PLC nor PLD had any effect on [3H]inositol release. We next examined the effect of PI-PLC on [Ca2+]i in TrpL cells. Addition of PI-PLC produced a small transient increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 7A). In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, PI-PLC had no effect, but subsequent re-addition of Ca2+ to the extracellular bath caused a rapid increase in [Ca2+]i indicative of Ca2+ influx. PI-PLC had no effect on control BK cells (not shown). Thus, the increase in [Ca2+]i produced by extracellular PI-PLC is specific and is not related to the release of Ca2+ from internal stores, but appears to be related to stimulation of Ca2+ influx via TrpL. It is noteworthy that although PI-PLC presumably caused a substantial generation of endogenous DAG within the membrane, the [Ca2+]i response was considerably smaller than that observed following receptor stimulation.

Figure 7. Effect of exogenous PLC on TrpL activity.

A and B, TrpL cells were suspended in MBS (trace a) or nominally Ca2+-free MBS (trace b). At the time indicated, bacterially derived PI-PLC (0.5 U ml−1; A) or PC-PLC (0.25 U ml−1; B) was added. Ca2+ (10 mm) was added to trace b in each panel at the time indicated. Insets, the release of [3H]inositol (A) or [3H]choline (B) was followed as a function of time after the extracellular addition of PI-PLC or PC-PLC to pre-labelled cells. Controls had PC-PLC or PLD added (A) or no addition (B). C, TrpL cells (trace a) or control BK cells (trace b) were suspended in MBS and PC-PLC (0.25 U ml−1) was added at the time indicated.

We next examined the effect of exogenous application of PC-PLC. PC is the major phospholipid in most cell membranes, comprising ≈25% of the total phospholipid pool. The total PI pool in the plasmalemma is much lower than that of PC and is thought to be in the range of 2-4% (Michell et al. 1970). Thus, PC-PLC was expected to generate at least 5- to 10-fold more DAG compared to PI-PLC. Extracellular addition of PC-PLC to Sf9 cells, pre-incubated with [3H]choline for 24 h, caused a time-dependent release of the radiolabel that was essentially complete by 5 min (Fig. 7B, inset), demonstrating that a substantial amount of PC is accessible in the outer leaflet of the plasmalemma. PC-PLC caused an increase in [Ca2+]i in TrpL cells, similar to that seen with PI-PLC (Fig. 7B). The effect was unrelated to the release of Ca2+ from internal stores, since PC-PLC had little or no effect in Ca2+-free extracellular buffer at the concentration shown. In contrast to PI-PLC, PC-PLC also produced an increase in [Ca2+]i in BK cells (Fig. 7C), suggesting that the generation of large amounts of DAG has non-specific effects on endogenous Ca2+ flux pathways in Sf9 cells, as was seen with exogenous application of SAG and LLA.

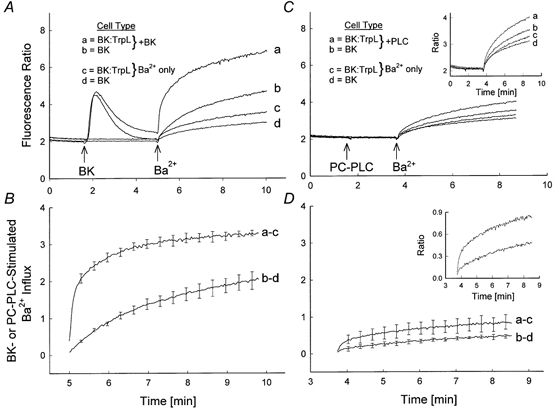

To directly assess the contribution of DAG to receptor-mediated activation of TrpL, the effect of bradykinin was compared to that of PC-PLC in paired experiments on BK-TrpL receptor-co-expressing (BK:TrpL) cells and on cells expressing only the BK receptor (Fig. 8). Addition of bradykinin to both cell types in Ca2+-free extracellular buffer caused an increase in [Ca2+]i indicative of Ca2+ release from internal stores (Fig. 8A). Subsequent addition of Ba2+ produced an increase in the fluorescence ratio reflecting Ba2+ influx. The bradykinin-stimulated Ba2+ influx was significantly increased (P < 0.004) in cells expressing the TrpL channel (Fig. 8B). Addition of PC-PLC also produced an increase in Ba2+ influx that was significantly greater (P < 0.05) in BK:TrpL cells compared to BK cells (Fig. 8C and D). Importantly, the magnitude of the response was 8.7-fold greater following bradykinin receptor stimulation compared to that following PC-PLC addition (P < 0.009, n = 3). Together these results suggest that generation of DAG alone may not be sufficient to explain receptor-mediated activation of TrpL.

Figure 8. Comparison of receptor-mediated and PC-PLC-induced activation of TrpL.

A, four traces are shown superimposed. Fura-2-loaded BK:TrpL cells (traces a and c) or BK cells (traces b and d) were suspended in nominally Ca2+-free MBS. At the times indicated in traces a and b, bradykinin (50 nm) and Ba2+ (10 mm) were added to the cuvette and the fluorescence recorded; cells represented by traces c and d received Ba2+ only (no bradykinin). B, bradykinin-stimulated Ba2+ influx for BK:TrpL cells (trace a minus c) and BK cells (trace b minus d) was calculated from three independent experiments performed as shown in A. Values represent means ±s.e.m. For clarity, s.e.m. are shown at 20 s intervals. C and D, same protocol as in A and B with PC-PLC (0.25 U ml−1) added at the time indicated. Insets in each panel show the data from the main panel with an expanded ratio scale. Note that the traces shown in A and C were obtained from the same batch of cells.

TrpL channels are activated by PLC in excised patches

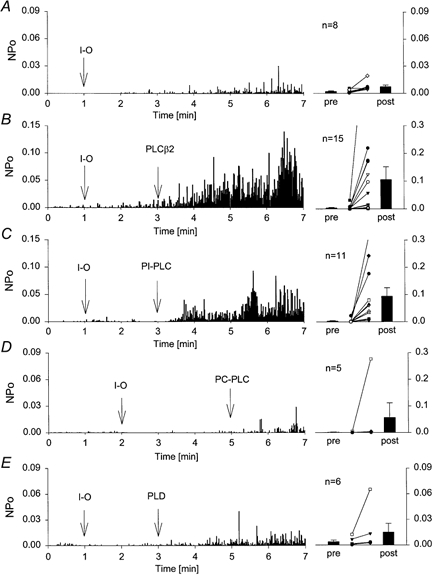

To more closely mimic receptor-induced DAG production, mammalian PLC-β2 was added to the bath solution during recording of single TrpL channels in excised inside-out patches. Under these conditions, DAG should be generated in the inner leaflet and Ins(1,4,5)P3 should rapidly diffuse into the bath. TrpL channel activity was low and stable when recorded in the cell-attached mode. Excision of the patch into the inside-out configuration caused a spontaneous, time-dependent increase in TrpL channel activity (Fig. 9A). As previously reported (Kunze et al. 1997), the spontaneous increase in TrpL channel activity reflects an increase in NPo. The spontaneous increase in TrpL channel activity following patch excision was variable, increasing slowly in the majority of patches (e.g. Fig. 9A), but increasing rapidly in others (e.g. Fig. 10). The first 2-3 min of channel recording following patch excision was a good predictor of spontaneous channel activation rate. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, TrpL channel activity was generally monitored for this length of time to establish the spontaneous growth rate for each patch. Addition of PLC-β2 to the bath solution during cell-attached recordings of single TrpL channels had no effect on channel activity (n = 17). However, application of PLC-β2 following patch excision (Fig. 9B), or excision into bath solution containing PLC-β2 (not shown) caused a significant increase in TrpL channel activity that was not observed following comparable additions of PLD (Fig. 9E). The effect of PLC-β2 was essentially irreversible; extensive washing by bath exchange did not return TrpL activity to basal levels and channel activity remained high for as long as the patch was maintained. TrpL channels were also activated by application of PI-PLC and PC-PLC to excised inside-out patches, but not when these phospholipases were applied in the cell-attached mode (Fig. 9C and D). Since TrpL channel activity was unaffected by exogenous phospholipases when recorded in the cell-attached mode, access of the enzymes to the cytoplasmic membrane surface must be required. Although it is difficult to compare between treatments because the total number of channels per patch is unknown, the effect of the phospholipases on TrpL followed the sequence PLC-β2 > PI-PLC > PC-PLC. As mentioned above, the percentage of PC in the plasmalemma is thought to be 5- to 10-fold greater than that of PI. Exton and colleagues have shown that the composition of the inositol phospholipid pool in liver plasma membrane is ≈90% PI, 1% PIP and 9% PIP2 (Augert et al. 1989). Since the substrate preference of PC-PLC, PI-PLC and PLC-β2 is PC, PI and PIP/PIP2, respectively, the amount of DAG generated by these enzymes should follow the sequence PC-PLC >> PI-PLC >> PLC-β2. Furthermore, none of these phospholipases activated TrpL in the cell-attached mode. As previously reported, TrpL is activated in the cell-attached mode by receptor stimulation when the agonist is added to the bath solution, i.e. outside the patch (Kunze et al. 1997). Together, these results suggest that DAG may not be the primary activator of TrpL.

Figure 9. Stimulation of TrpL single channels by PLC-β2.

A-E, single TrpL channels were recorded in cell-attached mode. The average NPo, binned at 1 s intervals, is shown on the left as a function of time after seal formation. At the time indicated (I-O), membrane patches were excised from the cell into the inside-out configuration. PLC-β2 (0.5 μg ml−1), PI-PLC (0.25 U ml−1), PC-PLC (0.5 U ml−1) or PLD (25 U ml−1) was added to the bath solution at the time indicated in each panel. The average NPo was determined for each patch 30 s before (pre) and 2 min after (post) exposure of the cytoplasmic surface of the patch to the indicated phospholipase. For clarity, different scales are shown in each panel. Bars show the mean ±s.e.m. (n as indicated); the post-phospholipase values for each are significantly different from the pre-phospholipase values (P ranged from < 0.039 to 0.001). Post-phospholipase values for PLC-β2 and PI-PLC were significantly different from control (P < 0.05), whereas those for PC-PLC and PLD were not.

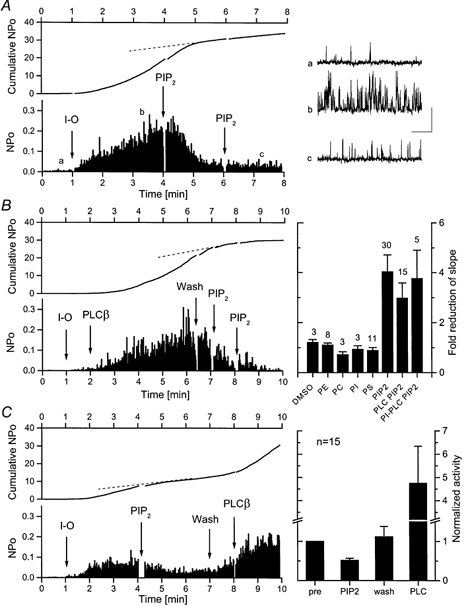

Figure 10. Inhibition of spontaneous TrpL channel activity by PIP2.

A, the activity of single TrpL channels recorded in the inside-out configuration was allowed to spontaneously increase with time. Channel activity was recorded at a holding potential of +50 mV and the complete diary of NPo (binned at 1 s intervals) is shown in the lower panel. PIP2 (0.5 μg ml−1) was added to the bath solution at the times indicated. Upper panel shows the cumulative NPo plot for this experiment. Representative TrpL channel activity is shown on the right on an expanded time base taken at the times indicated in the main panel (a, b, c); scale bars indicate 5 pA and 50 ms. B, same protocol as in A. The activity of single TrpL channels recorded in inside-out configuration was stimulated by addition of 0.5 μg ml−1 PLC-β2 and inhibited by addition of PIP2 (0.5 μg ml−1) to the bath solution at the times indicated. The histogram on the right summarizes results from experiments performed as in A and B. Each bar represents the mean (±s.e.m.)-fold reduction in cumulative NPo (slope) following the addition of vehicle (DMSO) or the indicated phospholipid; n is shown above each bar. PE, PC, PI and PS were applied at 1 μg ml−1 final concentration. The inhibition produced by PIP2 was significant; P < 0.001. C, TrpL channels, pre-inhibited by PIP2, could be reactivated by wash or by subsequent addition of PLC-β2. The histogram on the right shows the mean ±s.e.m. slope values normalized to that observed before addition of PIP2 (pre versus PIP2, P < 0.001; wash versus PLC, P < 0.05).

TrpL channels are inhibited by PIP2 in excised patches

Although DAG and/or PUFAs appear to regulate TrpL channel activity, the results presented thus far suggest that their role in receptor-mediated activation of TrpL may be secondary or indirect. We therefore tested the alternative hypothesis that activation of TrpL by PLC reflects, at least in part, the hydrolysis of PIP2 rather than the generation of either Ins(1,4,5)P3 or DAG. If TrpL is activated by PLC via hydrolysis of PIP2, we reasoned that addition of exogenous PIP2 to excised inside-out patches should inhibit TrpL activity. The results of one such experiment are shown in Fig. 10A. TrpL channel activity increased rather dramatically following patch excision, but stabilized at ≈3.5 min as indicated by the NPo plot. Application of PIP2 (0.5 μg ml−1; 0.5 μm) to the patch at 4 min caused a dramatic reduction in TrpL channel activity, but subsequent addition of a second aliquot of the lipid had no further effect. Cumulative NPo plots are often informative of changes in channel activity. If channel activity is constant, cumulative NPo will be linear with time; if channel activity increases with time, the cumulative NPo plot will be concave upward and if channel activity decreases with time, a reduction of the slope will be observed. All three profiles are represented in Fig. 10A. Initially channel activity spontaneously increases with time and cumulative NPo is concave upward. Between 3.5 and 4.5 min, channel activity is constant and cumulative NPo is linear. At ≈4.5 min, 30 s after PIP2 addition, channel activity decreases and there is a substantial reduction in slope of the cumulative NPo plot. Overall, inhibition of spontaneous TrpL channel activity by 0.5 μm PIP2, as measured by the change in slope of the NPo plot, was observed in 45 out of 76 patches. Likewise, PIP2 inhibited TrpL channel activity that was stimulated by pre-treatment with either PLC-β2 (Fig. 10B, 15 of 21patches) or PI-PLC (5 of 5 patches). The inhibition was specific for PIP2; no effect (i.e. no reduction in the slope of the cumulative NPo plot) was observed upon application of vehicle alone (DMSO) or following application of PC, PE, PI or PS to TrpL-containing patches (Fig. 10B, right). The next experiments determined whether the effect of PIP2 was irreversible. As shown in Fig. 10C, TrpL channels inhibited by PIP2 partially recovered following washout of the phosphatidylinositide from the bath. Recovery during washout probably reflects endogenous PLC activity associated with the patch. Subsequent addition of PLC-β2 significantly increased TrpL channel activity above the level observed following washout of PIP2. Thus, the effect of PIP2 on TrpL is reversible, suggesting that it may be related to the membrane concentration of PIP2. To test this hypothesis, the effect of PIP2 sequestration by anti-PIP2 antibodies was examined. Addition of anti-PIP2 antibodies had no significant effect on TrpL channel activity measured in excised inside-out patches (n = 27). However, preincubation of PIP2 with the antibody significantly reduced the effectiveness of PIP2 on TrpL channel activity, as did preincubation with penta-lysine (n = 4 of 4 for each; P < 0.05 relative to penta-alanine control), suggesting that both manoeuvres reduce the effective concentration of PIP2. Thus, sequestration of PIP2 in the membrane by anti-PIP2 antibodies is not sufficient for activation of TrpL. Lastly, we examined the effect of PIP2 on TrpL channels activated by LLA and LNA. PIP2 had no effect in the presence of strong stimulation by 20 μm LLA or LNA (n = 4). However, when the concentration of LLA or LNA was reduced to 2 μm, PIP2 produced a significant 63 ± 12%(n = 4 of 4, P < 0.05) reduction of channel activity as indicated by the change in slope of the cumulative NPo plot.

For many of the assays and agents examined in this study, similar concentrations were employed, allowing for cross-comparison between techniques. A summary of all such experiments with a semi-quantitative indication of effect in each recording mode is given in Table 1. For LNA and LLA, there was a good correlation between the results obtained with fura-2 and the electrophysiological assays. However, both SAG and AA were less potent in the fura-2 assay. This is somewhat surprising, given that SAG and AA were strong activators of TrpL recorded in the whole-cell or cell-attached mode. It is noteworthy that all of the phospholipases tested in the whole-cell or cell-attached recording mode had little or no effect on TrpL channel activity. For PLC-β2, this was expected, since it is unlikely that PIP or PIP2 is present in the outer leaflet of the membrane. However, the relative insensitivity of TrpL to PI-PLC and PC-PLC in these recording modes provides additional support for the conclusion that endogenously generated DAG has only a modest effect. Alternatively, there may be a substantial diffusion barrier preventing DAG generated in the outer leaflet of the membrane from gaining access to TrpL channels either in a whole-cell or in a cell-attached patch. We also noted a small effect of PLA2, but only in inside-out mode, probably reflecting local generation of AA or some other PUFA.

Table 1.

Summary of effects of various agents on TrpL recorded using the fura-2 assay or by the patch-clamp technique in whole-cell, inside-out and cell-attached recording modes

| Assay | PLC-β2 (0.5 μg ml−1) | PI-PLC (0.5 U ml−1) | PC-PLC (5.0 U ml−1) | PLD (25Uml−1) | PLA2 (1.2 U ml−1) | SAG(20 μm) | LLA(20 μm) | LNA (20 μm) | AA (10 μm) | Anand (10 μm) | OAG (100 μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fura-2 | ND | + | + | ND | ND | + | ++++ | ++++ | – | – | – |

| WC | – | + | + | – | – | +++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | – | – |

| (3) | (8) | (14) | (3) | (6) | (6) | (14) | (4) | (6) | (3) | (3) | |

| I-O | +++ | ++ | + | – | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++ | – | – |

| (20) | (22) | (6) | (8) | (2) | (11) | (9) | (8) | (3) | (6) | (5) | |

| C-A | – | – | – | – | – | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | – | – |

| (17) | (9) | (14) | (2) | (4) | (6) | (3) | (7) | (2) | (1) | (1) | |

| PIP2 inhibits(I-O) | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | — | Yes | Yes | — | — | — |

A semi-quantitative comparison is made for each agent at the indicated concentrations added to the bath solution in each recording mode (WC, whole cell; I-O, inside out; C-A, cell attached). Please note that other concentrations have been examined for some of these agents (see text). PIP2 (0.5 μg ml−1) inhibits activity stimulated by 2 μm LLA or LNA. The number of experiments is given in parentheses for the electrophysiological experiments; the fura-2 experiments were performed at least 3 times. Positive effect is on a scale of 1–5; a minus sign indicates no effect; ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

The Drosophila photoreceptor protein TrpL was the first of the Trp family of ion channels to be heterologously expressed (Hu et al. 1994; Harteneck et al. 1995; Lan et al. 1996; Xu et al. 1997). Early studies revealed that TrpL channels could be activated by receptor stimulation through a mechanism that was not related to depletion of the internal Ca2+ store (Hu & Schilling, 1995; Harteneck et al. 1995). Previous studies have also shown that receptor-mediated activation of TrpL heterologously expressed in Drosophila S2 cells is greatly attenuated by U73122, suggesting that PLC is required (Hardie & Raghu, 1998). Likewise, the present study found that TrpL activation in Sf9 cells by bradykinin receptor stimulation was completely inhibited by U73122, but not by U73343. This result was obtained in fura-2 assays and in whole-cell recordings of TrpL channels. Thus, as in Drosophila photoreceptor cells, activation of heterologously expressed TrpL by receptor stimulation requires PLC.

If activation is dependent upon PLC, but not on depletion of the internal Ca2+ store, then Ins(1,4,5)P3, DAG, hydrolysis of PIP2 or PLC itself may directly activate the channels. There is little support for the hypothesis that Ins(1,4,5)P3 directly regulates TrpL (Kunze et al. 1997; Hardie & Raghu, 1998; Chyb et al. 1999). However, it has recently been proposed that TrpL, and other members of the Trp channel family, may be regulated by DAG and/or PUFAs (Okada et al. 1999; Hofmann et al. 1999; Chyb et al. 1999). Although it is clear that the activity of these channels can be dramatically increased by exogenous application of various DAGs and PUFAs, two questions remain unresolved. Is this the mechanism by which receptor-mediated activation occurs, and is this a direct effect of these agents on the channels? In the present study, SAG and all of the PUFAs tested increased Ba2+ influx in control BK cells. Furthermore, LLA and SAG caused the activation of an endogenous, NMDG+-permeable, non-selective cation channel in both TrpL and BK cells, suggesting that these agents have significant non-specific effects unrelated to the activation of TrpL. However, the response of the TrpL-expressing cells was always much greater than that observed in the infection-control cells. Indeed, the effects of these agents on TrpL activity measured either electrophysiologically or by fura-2 assay, were much larger than any activation seen following receptor stimulation. At least in part, these agents seem to affect PLC activity in the Sf9 cell, since > 70% of the stimulation by LLA and SAG was blocked by U73122, but not by U73343. Together, these results suggest that exogenous DAG and PUFAs produce non-specific effects in Sf9 cells and may activate TrpL via indirect mechanisms, e.g. activation of endogenous PLC. Chyb et al. (1999) reported that LNA activates the light-sensitive channels in photoreceptor cells from Drosophila norpA mutants. Since norpA flies lack functional PLC, this result suggests that PLC is not required for channel activation by PUFAs. However, the absence of light-activated PLC in norpA mutants does not eliminate the possibility that PUFAs are acting via a different isoform of PLC. It is also important to note that compensatory changes in flies lacking functional PLC have not been considered. Thus, changes in channel density, upregulation of other phospholipases, changes in other enzymes or substrates (e.g. the phosphatidylinositol transfer protein) may occur in mutant flies lacking PLC and have an unknown or unexpected impact on channel activity. Thus, it could be difficult to recognize non-specific or indirect effects of DAGs or PUFAs in intact photoreceptor cells. On the other hand, several results suggest that the effects of low concentrations of DAG and PUFAs exhibit specificity. Both anandamide, a derivative of AA in which the acid group is conjugated to ethanolamine via an amide linkage, and OAG, a more permeable form of DAG compared to SAG, had no effect on TrpL channel activity at the concentrations tested. Likewise, oleic acid was less effective and stearic acid was without effect. These results suggest that there are specific structural requirements for both the fatty acid tails and the head group important for activation of TrpL, at least for exogenously applied DAGs and PUFAs. Whether these structural requirements reflect an interaction of these agents with TrpL or PLC requires further investigation.

Because a number of signalling cascades may be activated or inhibited following stimulation of G protein-coupled membrane receptors, and because of uncertainties with regard to actual concentrations of DAG or PUFAs released in the membrane during challenge with receptor agonists, we examined the effect of extracellular application of PI-PLC which, at least in theory, should release endogenous DAG without activation of G proteins or release of intracellular second messengers. Furthermore, the composition of the DAG should be identical to that released following receptor stimulation. The results show that there is a small and relatively slow increase in [Ca2+]i following challenge with PI-PLC. The effect was specific for TrpL-expressing Sf9 cells and was not related to the release of Ca2+ from internal stores. The effect was transient and followed closely the time course of [3H]inositol release, measured in parallel experiments. Thus, it seems likely that endogenous DAG specifically activates TrpL, but the effect is modest and apparently requires the continuous production of DAG. In this regard, the response to PI-PLC is different from that obtained with receptor stimulation. However, higher concentrations of PI-PLC might produce a greater and perhaps more rapid activation of TrpL, but these experiments were prohibited by cost. We therefore employed PC-PLC to generate larger quantities of endogenous DAG and the response was compared to that obtained following receptor stimulation. This comparison was made on identical cells to ensure that the level of TrpL channel expression was the same. The results clearly show that receptor-induced activation of TrpL was significantly greater compared to the activation induced by PC-PLC. Furthermore, PI-PLC and PC-PLC had no significant effect on TrpL currents recorded in cell-attached patches and only a small effect in whole-cell mode. Together, these results suggest that the release of DAG cannot mimic receptor-mediated activation of TrpL.

The DAG produced by extracellular PI-PLC or PC-PLC is generated in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane, and is presumably generated globally, whereas receptor stimulation releases DAG to the inner leaflet and may be localized to specific sites. We therefore examined the effect of PLC on TrpL recorded at the single channel level in excised inside-out membrane patches. These experiments showed that TrpL channel activity was activated by exogenous PLC-β2, PI-PLC and PC-PLC, but not by PLD, when the enzymes were added to the solution bathing the cytoplasmic membrane surface. Two lines of evidence suggest that DAG alone is not sufficient to explain this activation. First, all three enzymes generate DAG, and the amount of DAG produced should follow the sequence PC-PLC >> PI-PLC >> PLCβ2, yet PLCβ2 was the most effective activator of TrpL and PC-PLC the least. Second, the channels in inside-out patches remained activated despite washout of the enzyme. The fura-2 experiments demonstrate that the response to exogenous PI-PLC and PC-PLC was transient and correlated closely with the time course of inositol or choline release, suggesting that continuous DAG production is required. Therefore, DAG may be a regulator of channel function, but may not be responsible for the initial activation of TrpL induced by receptor stimulation. One note of caution, although the composition of the fatty-acid tails in PI and PIP2 from liver plasma membrane is similar (Augert et al. 1989), the composition of the DAG produced by PC-PLC, PI-PLC and PLC-β2 in Sf9 cells is unkonwn. Therefore, we cannot eliminate the possibility that differences in TrpL activation by the various phospholipases reflect the proportion of saturated fatty acids in PC, PI and PIP2.

Alternatively, PLC may directly activate TrpL, independent of enzyme activity, or hydrolysis of PIP2 may be the crucial event. Addition of PIP2 to the cytoplasmic surface of an inside-out patch either had no effect or produced a substantial inhibition of channel activity. The inhibition was seen on spontaneously active TrpL channels or on channels that had been pre-activated with PLC-β2, PI-PLC, LLA or LNA. Inhibition by PIP2 could be reversed by subsequent application of PLC-β2 and the effect was specific for PIP2. Importantly, no inhibition was observed with PS, suggesting that the effect of PIP2 was not simply a negative charge effect. Lastly, the effect of PIP2 could be attenuated by preincubation with agents known to bind PIP2, specifically penta-lysine and the anti-PIP2 antibody. Thus, it seems unlikely that the effect is related to some minor contaminant present in the PIP2 preparations employed. The reasons for the inability of PIP2 to inhibit TrpL in all patches examined is unknown. It suggests, however, that the effects of PIP2 may depend on the state of the channel or on the presence of some other protein in the patch. In this regard, the experiments in the present study were performed in the absence of added ATP. Thus it seems unlikely that mechanisms requiring phosphorylation events (e.g. activation of PI-3 kinase) are involved in PIP2-induced inhibition.

Although the single channel results suggest that PIP2 can influence TrpL channel activity, several lines of evidence suggest that hydrolysis of PIP2 is not the primary mechanism of activation of TrpL following receptor stimulation. As mentioned above, each of the PLCs tested has different substrate specificities and only mammalian PLC-β2 will directly hydrolyse PIP2, yet both bacterial PI-PLC and PC-PLC activate TrpL in inside-out membrane patches. The anti-PIP2 antibody, which was expected to activate TrpL, had no significant effect. Furthermore, PIP2 never produced 100% inhibition of channel activity even when higher amounts of the phospholipid were added to the bath. Lastly, it is clear that TrpL channels recorded in cell-attached patches can be activated by application of receptor agonist to the bath solution (Kunze et al. 1997). Since the channel is shielded from the bath solution under this recording condition, involvement of PIP2 hydrolysis in the activation mechanism would require that PLC activation outside the patch can deplete PIP2 in the patch membrane, or that activated G-proteins migrate from the cell to the patch membrane and activate patch-associated PLC. Both scenarios seem unlikely.

In conclusion, activation of heterologously expressed TrpL channels by receptor stimulation requires PLC. However, neither the hydrolysis of PIP2 nor the generation of DAG alone seems sufficient to explain this activation. It remains possible that hydrolysis of PIP2 and localized generation of DAG synergistically combine to activate TrpL during receptor stimulation. Likewise, we cannot eliminate the possibility that activated PLC directly regulates channel function independent of enzymatic activity, or that some other PLC-dependent step is crucial.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant GM52019 from NIH/NIGMS. W.G.S. was a recipient of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association, Northeastern Ohio Affiliate.

References

- Acharya JK, Jalink K, Hardy RW, Hartenstein V, Zuker CS. InsP3 receptor is essential for growth and differentiation but not for vision in Drosophila. Neuron. 1997;18:881–887. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80328-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augert G, Blackmore PF, Exton JH. Changes in the concentration and fatty acid composition of phosphoinositides induced by hormones in hepatocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:2574–2580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist BT, Shortridge RD, Schneuwly S, Perdew M, Montell C, Steller H, Rubin G, Pak WL. Isolation of a putative phospholipase C gene of Drosophila, norpA, and its role in phototransduction. Cell. 1988;54:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay G, Zhu X, Peyton M, Hurst R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Cloning and expression of a novel mammalian homolog of Drosophila transient receptor potential (Trp) involved in calcium entry secondary to activation of receptors coupled by Gq class of G protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:29672–29680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevesich J, Kreuz AJ, Montell C. Requirement for the PDZ domain protein, INAD, for localization of the TRP store-operated channel to a signaling complex. Neuron. 1997;18:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyb S, Raghu P, Hardie RC. Polyunsaturated fatty acids activate the Drosophila light-sensitive channels TRP and TRPL. Nature. 1999;397:255–259. doi: 10.1038/16703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Kunze DL, Vaca L, Schilling WP. Ins(1,4,5)P3 activates Drosophila cation channel Trpl in recombinant baculovirus-infected Sf9 insect cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:C1332–1339. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.5.C1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacion M, Sinkins WG, Schilling WP. Stimulation of Drosophila TrpL by capacitative Ca2+ entry. Biochemical Journal. 1999;341:41–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC, Minke B. Novel Ca2+ channels underlying transduction in Drosophila photoreceptors: Implications for phosphoinositide-mediated Ca2+ mobilization. Trends in Neurosciences. 1993;16:371–376. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC, Raghu P. Activation of heterologously expressed Drosophila TRPL channels: Ca2+ is not required and InsP3 is not sufficient. Cell Calcium. 1998;24:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(98)90125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harteneck C, Obukhov AG, Zobel A, Kalkbrenner F, Schultz G. The Drosophila cation channel trpl expressed in insect Sf9 cells is stimulated by agonists of G-protein-coupled receptors. FEBS Letters. 1995;358:297–300. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01455-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgemann DW, Ball R. Regulation of cardiac Na+,Ca2+ exchange and KATP potassium channels by PIP2. Science. 1996;273:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5277.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature. 1999;397:259–263. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Rajan L, Schilling WP. Ca2+ signaling in Sf9 insect cells and the functional expression of a rat brain M5 muscarinic receptor. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;266:C1736–1743. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Schilling WP. Receptor-mediated activation of recombinant Trpl expressed in Sf9 insect cells. Biochemical Journal. 1995;305:605–611. doi: 10.1042/bj3050605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Vaca L, Zhu X, Birnbaumer L, Kunze DL, Schilling WP. Appearance of a novel Ca2+ influx pathway in Sf9 insect cells following expression of the transient receptor potential-like (trpl) protein of Drosophila. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1994;201:1050–1056. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C-L, Feng S, Hilgemann DW. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gβγ. Nature. 1998;391:803–806. doi: 10.1038/35882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst RS, Zhu X, Boulay G, Birnbaumer L, Stefani E. Ionic currents underlying HTRP3 mediated agonist-dependent Ca2+ influx in stably transfected HEK293 cells. FEBS Letters. 1998;422:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SC, Jhon D-Y, Bae YS, Kim JH, Rhee SG. Activation of phospholipase C-γ by the concerted action of tau proteins and arachidonic acid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:18342–18349. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamouchi M, Philipp S, Flockerzi V, Wissenbach U, Mamin A, Raeymaekers L, Eggermont J, Droogmans G, Nilius B. Properties of heterologously expressed hTRP3 channels in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:345–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0345p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze DL, Sinkins WG, Vaca L, Schilling WP. Properties of single Drosophila trpl channels expressed in Sf9 insect cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C27–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.1.C27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan L, Bawden MJ, Auld AM, Barritt GJ. Expression of Drosophila trpl cRNA in Xenopus laevis oocytes leads to the appearance of a Ca2+ channel activated by Ca2+ and calmodulin, and by guanosine 5′[gamma-thio]triphosphate. Biochemical Journal. 1996;316:793–803. doi: 10.1042/bj3160793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman ER, Corey DP, Dulac C. TRP2: a candidate transduction channel for mammalian pheromone sensory signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:5791–5796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang W, Singh BB, Lockwich T, Jadlowiec J, O'Connell B, Wellner R, Zhu MX, Ambudkar IS. Trp1, a candidate protein for the store-operated Ca2+ influx mechanism in salivary gland cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:3403–3411. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell RH, Hawthorne JN, Coleman R, Karnovsky ML. Extraction of polyphosphoinositides with neutral and acidified solvents. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1970;210:86–91. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(70)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer BA, Suzuki E, Scott K, Jalink K, Zuker CS. The Drosophila light-activated conductance is composed of the two channels TRP and TRPL. Cell. 1996;85:651–659. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh D-Y, Shin SH, Rhee SG. Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C and mitogenic signaling. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1995;1242:99–114. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(95)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly DR, Miller LK, Luckow VA. Baculovirus Expression Vectors: A Laboratory Manual. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Obukhov AG, Harteneck C, Zobel A, Harhammer R, Kalkbrenner F, Leopoldt D, Lückhoff A, Nürnberg B, Schultz G. Direct activation of trpl cation channels by Gα11 subunits. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:5833–5838. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Inoue R, Yamazaki K, Maeda A, Kurosaki T, Yamakuni T, Tanaka I, Shimizu S, Ikenaka K, Imoto K, Mori Y. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel mouse transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP7. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:27359–27370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Shimizu S, Wakamori M, Maeda A, Kurosaki T, Takada N, Imoto K, Mori Y. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel receptor-activated TRP Ca2+ channel from mouse brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:10279–10287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp S, Cavalié A, Freichel M, Wissenbach U, Zimmer S, Trost C, Marquart A, Murakami M, Flockerzi V. A mammalian capacitative calcium entry channel homologous to Drosophila TRP and TRPL. EMBO Journal. 1996;15:6166–6171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp S, Hambrecht J, Braslavski L, Schroth G, Freichel M, Murakami M, Cavalie A, Flockerzi V. A novel capacitative calcium entry channel expressed in excitable cells. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:4274–4282. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JA, Assaf A, Peretz A, Nichols CD, Mojet MH, Hardie RC, Minke B. TRP, a protein essential for inositide-mediated Ca2+ influx is localized adjacent to the calcium stores in Drosophila photoreceptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3747–3760. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03747.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghu P, Colley NJ, Webel R, James T, Hasan G, Danin M, Selinger Z, Hardie RC. Normal phototransduction in Drosophila photoreceptors lacking an InsP3 receptor gene. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2000;15:429–445. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Plant TD, Obukhov AG, Hofmann T, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Receptor-mediated regulation of the non-selective cation channels TRPC4 and TRPC5. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:17517–17526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.23.17517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling WP, Rajan L, Strobl-Jager E. Characterization of the bradykinin-stimulated calcium influx pathway of cultured vascular endothelial cells: Saturability, selectivity and kinetics. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:12838–12848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya F, Bae YS, Rhee SG. Regulation of phospholipase C isozymes: activation of phospholipase C-γ in the absence of tyrosine-phosphorylation. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 1999;98:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(99)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth TJ, Thompson JL. Effect of temperature on receptor-activated changes in [Ca2+]i and their determination using fluorescent probes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:1410–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkins WG, Estacion M, Schilling WP. Functional expression of TrpC1: a human homologue of the Drosophila Trp channel. Biochemical Journal. 1998;331:331–339. doi: 10.1042/bj3310331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RJ, Sam LM, Justen JM, Bundy GL, Bala GA, Bleasdale JE. Receptor-coupled signal transduction in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils: Effects of a novel inhibitor of phospholipase C-dependent processes on cell responsiveness. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1990;253:688–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui JL, Petit-Jacques J, Logothetis DE. Activation of the atrial KACh channel by the βγ subunits of G proteins or intracellular Na+ ions depends on the presence of phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:1307–1312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda S, Sierralta J, Sun Y, Bodner R, Suzuki E, Becker A, Socolich M, Zuker CS. A multivalent PDZ-domain protein assembles signalling complexes in a G-protein-coupled cascade. Nature. 1997;388:243–249. doi: 10.1038/40805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaca L, Sinkins WG, Hu Y, Kunze DL, Schilling WP. Activation of recombinant Trp by thapsigargin in Sf9 insect cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:C1501–1505. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnat J, Philipp S, Zimmer S, Flockerzi V, Cavalié A. Phenotype of a recombinant store-operated channel: highly selective permeation of Ca2+ Journal of Physiology. 1999;518:631–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0631p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wes PD, Chevesich J, Jeromin A, Rosenberg C, Stetten G, Montell C. TRPC1, a human homolog of a Drosophila store-operated channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:9652–9656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer BJ. Statistical Principles in Experimental Design. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Babnigg G, Villereal ML. Functional significance of human trp1 and trp3 in store-operated Ca2+ entry in HEK-293 cells. American Journal of Physiology: Cell Physiology. 2000;278:C526–536. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.3.C526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XZS, Li HS, Guggino WB, Montell C. Coassembly of TRP and TRPL produces a distinct store-operated conductance. Cell. 1997;89:1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng F, Makielski JC. Anionic phospholipids activate ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:5388–5395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Chu PB, Peyton M, Birnbaumer L. Molecular cloning of a widely expressed human homologue for the Drosophila trp gene. FEBS Letters. 1995;373:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01038-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Jiang M, Birnbaumer L. Receptor-activated Ca2+ influx via human Trp3 stably expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells. Evidence for a non-capacitative Ca2+ entry. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:133–142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Jiang MS, Peyton M, Boulay G, Hurst R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. trp, a novel mammalian gene family essential for agonist-activated capacitative Ca2+ entry. Cell. 1996;85:661–671. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitt C, Obukhov AG, Strübing C, Zobel A, Kalkbrenner F, Lückhoff A, Schultz G. Expression of TRPC3 in Chinese hamster ovary cells results in calcium-activated cation currents not related to store depletion. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;138:1333–1341. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]