Abstract

We hypothesised that reducing arterial oxyhaemoglobin (O2Hba) with carbon monoxide (CO) in both normoxia and hyperoxia, or acute hypoxia would cause similar compensatory increases in human skeletal muscle blood flow and vascular conductance during submaximal exercise, despite vast differences in arterial free oxygen partial pressure (Pa,O2).

Seven healthy males completed four 5 min one-legged knee-extensor exercise bouts in the semi-supine position (30 ± 3 W, mean ± s.e.m.), separated by ≈1 h of rest, under the following conditions: (a) normoxia (O2Hba= 195 ml l−1; Pa,O2= 105 mmHg); (b) hypoxia (163 ml l−1; 47 mmHg); (c) CO + normoxia (18% COHba; 159 ml l−1; 119 mmHg); and (d) CO + hyperoxia (19% COHba; 158 ml l−1; 538 mmHg).

CO + normoxia, CO + hyperoxia and systemic hypoxia resulted in a 29-44% higher leg blood flow and leg vascular conductance compared to normoxia (P < 0.05), without altering blood pH, blood acid-base balance or net leg lactate release.

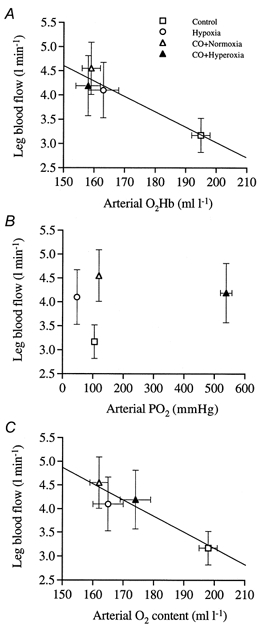

Leg blood flow and leg vascular conductance increased in association with reduced O2Hba (r2= 0.92-0.95; P < 0.05), yet were unrelated to altered Pa,O2. This association was further substantiated in two subsequent studies with graded increases in COHba(n = 4) and NO synthase blockade (n = 2) in the presence of normal Pa,O2.

The elevated leg blood flow with CO + normoxia and CO + hyperoxia allowed a ≈17% greater O2 delivery (P < 0.05) to exercising muscles, compensating for the lower leg O2 extraction (61%) compared to normoxia and hypoxia (69%; P < 0.05), and thereby maintaining leg oxygen uptake constant.

The compensatory increases in skeletal muscle blood flow and vascular conductance during exercise with both a CO load and systemic hypoxia are independent of pronounced alterations in Pa,O2 (47-538 mmHg), but are closely associated with reductions in O2Hba. These results suggest a pivotal role of O2 bound to haemoglobin in increasing skeletal muscle vasodilatation during exercise in humans.

Oxygen delivery to the skeletal muscle is a function of the O2 content of arterial blood (Ca,O2) and muscle blood flow. Blood oxygen content is largely determined by O2 bound to haemoglobin, but there is also a small amount of O2 dissolved in the blood that has generally been thought to act as an important signal for systemic and skeletal muscle blood flow regulation (Jackson, 1987; Baron et al. 1990; Pries et al. 1995). Recent in vitro evidence, however, suggests that the red blood cell itself, the haemoglobin-containing O2 carrier, might function as an O2 sensor, which could contribute significantly to the regulation of local blood flow in vivo by releasing ATP and/or NO in response to reduced oxygenation (Ellsworth et al. 1995; Jia et al. 1996; Stamler et al. 1997). Whether or not skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise is regulated as a function of O2 dissolved in the blood or O2 bound to haemoglobin in humans remains unresolved. It is clear, however, that alterations in Ca,O2 with hyperoxia, hypoxia and anaemia during submaximal exercise are accompanied by proportional changes in skeletal muscle blood flow. The majority of human studies involving a reduction of Ca,O2 with anaemia, hypoxia or combined anaemia and hypoxia show reciprocal elevations in cardiac output and active muscle blood flow and higher leg vascular conductance during submaximal knee-extensor exercise and cycle ergometer exercise (Rowell et al. 1986; Knight et al. 1993; Richardson et al. 1995; Koskolou et al. 1997a, b; Roach et al. 1999; Kjær et al. 1999; Calbet et al. 1999). Conversely, increasing Ca,O2 with hyperoxia has been shown to reduce (Welch et al. 1977) or have no effect (Knight et al. 1993) on skeletal muscle blood flow. The proposed role of dissolved O2 in muscle blood flow regulation was recently questioned by Roach et al. (1999), who discovered equally elevated exercising leg blood flow and vascular conductance when Pa,O2 varied from ≈40 mmHg with hypoxia to ≈105 mmHg with anaemia. However, to conclusively rule out a role of dissolved O2 in local skeletal muscle blood flow regulation, skeletal muscle haemodynamics should be studied when oxyhaemoglobin is equally reduced, but Pa,O2 is severalfold greater than normoxic levels, as normally found with hyperoxia, when skeletal muscle blood flow during submaximal exercise is found to be reduced (Welch et al. 1977).

Carbon monoxide (CO) inhalation affords the opportunity to independently manipulate Pa,O2 and oxyhaemoglobin, while anaemia is a rather cumbersome procedure and systemic hypoxia reduces both Ca,O2 and Pa,O2. The use of CO inhalation to study cardiovascular regulation during exercise in humans has a long history (Chiodi et al. 1941; Asmussen & Nielsen, 1955; Vogel & Gleser, 1972), yet its effects on skeletal muscle haemodynamics have never been assessed. The affinity of haemoglobin for CO is some 200-fold greater that its affinity for O2 (Piantadosi, 1987), thus the volume of free CO in blood while breathing CO is probably very small. Another interesting feature of CO is that it influences the binding kinetics of oxyhaemoglobin, resulting in a leftward shift of the O2 dissociation curve as the co-operative binding of CO with one of the haeme subunits increases the affinity of the remaining subunits for O2 (Douglas et al. 1912; Haldane, 1912). Therefore, a decreased off-loading of O2 from haemoglobin could be anticipated with CO inhalation compared to normoxia and hypoxia. This raises the question as to whether skeletal muscle blood flow increases further than with systemic hypoxia in conditions where O2 off-loading from haemoglobin is diminished, so that muscle oxygen uptake can be maintained constant.

The primary hypothesis of this study was that arterial oxyhaemoglobin is more closely linked to elevations in exercising skeletal muscle blood flow than arterial oxygen tension. The secondary hypothesis was that this elevation in muscle blood flow would compensate for the reduced arterial oxygenation, such that oxygen delivery to the muscle and its oxygen uptake would be maintained. Therefore, leg blood flow, arterial blood pressure, and femoral arterial and venous blood gases were measured repeatedly during submaximal knee-extensor exercise with arterial normoxaemia, arterial hypoxaemia, CO in conjunction with normoxia and CO in conjunction with hyperoxia.

METHODS

Subjects

Thirteen healthy, recreationally active males participated in this study. They had a mean (±s.d.) age of 26 ± 1 years, body weight of 77 ± 4 kg and height of 178 ± 4 cm. The subjects were fully informed of any risks and discomfort associated with the experiments before giving their informed written consent to participate. The study conformed to the code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Copenhagen and Frederiksberg communities. Prior to the experimental trial (3-4 days), the subjects performed two incremental knee-extensor exercise tests until fatigue under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (11% inspired O2 fraction, FI,O2).

Experimental design

On the experimental day, seven of the subjects completed four 5 min one-legged knee-extensor exercise bouts in the semi-supine position at 41 ± 1% (mean ±s.e.m.) of the peak knee-extensor power output (30 ± 3 W; range, 24-48 W; ≈60 r.p.m.), separated by ≈1 h of rest, under the following conditions: (a) normoxia (FI,O2, 21%); (b) hypoxia (FI,O2, ≈12%); (c) carbon monoxide (CO) breathing combined with normoxia (18 ± 1% circulating carboxyhaemoglobin fraction (FCOHb); FI,O2, 21%); and (d) CO breathing combined with hyperoxia (19 ± 1%FCOHb; FI,O2, 90-99%). The normoxic and hypoxic trials were performed first and second, respectively, whereas the order of the two subsequent CO trials was counterbalanced across subjects. The decision to perform the CO trials after normoxia and hypoxia was based on the rate of CO elimination from the body having a half-time of 1.5-4.0 h (Pace et al. 1950). Thus, a time period of 7-8 h would have been required to reach baseline values, thereby making it impractical to perform the experimental tests in a single day.

The subjects reported to the laboratory at 08.00 h, following the ingestion of breakfast. Upon arrival, they rested in the supine position while two catheters were placed using the Seldinger technique, one in the femoral vein and another in the femoral artery of the right leg. Both catheters were positioned in close proximity (1-2 cm) to the inguinal ligament. A thermistor to measure venous blood temperature was inserted through a catheter and advanced 10 cm proximal to the tip of the infusion catheter for the determination of femoral venous blood flow. Electrodes to measure 3-lead electrocardiograms were also attached. Following ≈15 min of supine rest on the knee-extensor ergometer, blood samples were withdrawn simultaneously from the femoral artery and femoral vein for later determination of baseline blood variables. The subjects then started to exercise in the normoxic condition. Before and during exercise in the hypoxia and CO trials, the subjects breathed in a closed-circuit system (see Fig. 1). The rebreathing closed-circuit system consisted of a 4 l custom-made chamber containing CO2 absorber (Sofnolime, Molecular Products, Essex, UK), a 10 l reservoir, a two-way breathing valve (Hans-Rudolph Inc., Kansas City, MO, USA) and two hoses connecting the chamber and the breathing valve (Fig. 1). The composition of the inspired gas was manually adjusted in the reservoir using gas regulators connected to two tanks containing 11% O2 in N2 and 100% O2, while being monitored on-line with a Medgraphics CPX/D metabolic cart (Minneapolis-St Paul). During the rest period after the hypoxic trial, CO (95% purity) was administered through an extension line and a series of luer-lock stopcocks (Ohmeda, Helsingborg, Sweden) connected to the two-way valve, using calibrated plastic syringes (24-48 ml; see Fig. 1). A series of CO boluses estimated to increase FCOHb by 10% (148 ± 7 ml; range, 120-159 ml) was initially administered and the arterial FCOHb was measured after 20 min. A second CO dose aimed to increase FCOHb to ≈20% was then administered (total CO administered, 253 ± 26 ml; range, 179-360 ml). All subjects tolerated this procedure well, showing no signs of discomfort. During exercise, heart rate and arterial blood pressure were recorded continuously. Leg blood flow was measured (thermodilution) at 1, 2 and 4 min of exercise. Arterial and venous blood samples (2 ml) were withdrawn simultaneously after blood flow measurements. The experiment was performed in a thermoneutral environment (22-25°C ambient temperature and 755-762 mmHg barometric pressure).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the experimental set-up.

The apparatus consists of a closed-circuit respiratory system and an ergometer for knee-extensor exercise (Anderson & Saltin, 1985). The closed-circuit system comprised a 4 l custom-made chamber containing CO2 absorber, a 10 l reservoir, a two-way breathing valve and two hoses connecting the chamber and the breathing valve. The inspiratory gas in the reservoir was adjusted using gas regulators connected to two tanks containing 11% O2 in N2 and 100% O2, while being monitored on-line with a Medgraphics CPX/D metabolic cart. This set-up provides the opportunity to study the systemic (e.g. cardiac output, heart rate, ventilation) and the local regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow while using CO to manipulate the O2 bound to haemoglobin and varying the inspiratory fraction of O2 to alter the O2 dissolved in the blood.

Additional experiments

The other six subjects participated in two additional experiments aimed at determining: (1) whether exercising skeletal muscle blood flow increases in direct proportion to the reductions in arterial oxyhaemoglobin, and (2) whether the enhanced skeletal muscle vasodilatation is mediated by a mechanism involving NO. To accomplish the first aim, four subjects completed three 5 min knee-extensor exercise bouts at ≈40% of the peak knee-extensor power output (range, 35-48 W; ≈60 r.p.m.), separated by ≈1 h of rest, under the following conditions: (1) normal CO (COHba= 2 ± 0.1% (mean ±s.e.m.); O2Hba= 206 ± 8 ml l−1; Pa,O2= 113 ± 10 mmHg); (2) mild CO (9 ± 1%; 192 ± 8 ml l−1; 115 ± 5 mmHg); and (3) moderate CO (16 ± 1%; 178 ± 7 ml l−1; 117 ± 3 mmHg). To shed some light onto the second question, two subjects completed four exercise bouts under: (1) normoxia, (2) hypoxia, (3) hypoxia + NO blockade, and (4) CO + normoxia + NO blockade. NOS inhibition was achieved by intra-arterial infusion of the competitive inhibitor NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA). The rate of l-NMMA infusion was 3 mg min−1 l−1 thigh volume during the 3 min prior to exercise as well as during exercise.

Leg blood flow, heart rate and arterial blood pressure

Femoral venous blood flow (i.e. leg blood flow, LBF, largely indicative of quadriceps blood flow during knee-extensor exercise) was determined by the constant infusion thermodilution technique, originally described by Andersen & Saltin (1985) and recently modified (González-Alonso et al. 1998). Briefly, both venous and infusate temperatures were measured continuously during saline infusion (15-20 s, 110 ml min−1; Harvard pump 44, Harvard Apparatus, Millis, MA, USA) via thermistors (Edslab, TD probe 94-030-2.5 F) connected to a custom-made electronic box, which was interfaced to a Power Macintosh computer using a MacLab/16 s data acquisition system (ADInstruments, Sydney, Australia). The venous thermistor was positioned ≈10 cm beyond the tip of the 8 cm catheter. LBF was calculated using a heat balance equation and values in this study represent the average of measurements made at 2 and 4 min of exercise when LBF had reached a plateau. Heart rate was obtained either from the continuously recorded electrocardiogram signal or from the record obtained with a PE 3000 Sports Tester (Polar Electro, Finland). Arterial blood pressure was continuously monitored in the femoral artery in the inguinal region (40-60 cm below the heart) by a pressure transducer (Pressure Monitoring Kit, Baxter). Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was computed by integration of each pressure curve. Leg vascular conductance was calculated as the quotient between LBF and MABP and expressed as conductance units of litres per minute per millimetre Hg (l min−1 mmHg−1).

Blood analysis

Haematocrit was measured in triplicate after micro-centrifugation and corrected for trapped plasma (0.98). Haemoglobin concentration, carboxyhaemoglobin fraction and blood O2 saturation were determined spectrophotometrically (OSM-3 Hemoximeter, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). PO2, PCO2 and pH were determined with the Astrup technique (ABL5, Radiometer) and corrected for measured femoral venous blood temperature, whereas HCO3− concentration was calculated as described by Siggaard-Andersen (1974). Blood glucose, lactate and electrolyte (K+, Na+, Ca2+ and K+) concentrations were determined with an automated electrolyte-metabolite analyser (EML 105/100, Radiometer). Arterial plasma noradrenaline and adrenaline concentrations were determined using high performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (Hallman et al 1978).

Calculations

To guide the initial administration of CO, total haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]) was estimated using resting [Hb] and body weight, assuming an average circulating blood volume of 82 ml kg−1 (Roach et al. 1999). The volume of CO (ml) administered was calculated according to the following formula (Christensen et al. 1993):

where 0.978 is the correction factor for CO remaining in the lung-bag system after equilibration with the blood; DnCO (mmol) is the ratio between the estimated total [Hb] and the desired increase in carboxyhaemoglobin (FCOHb; e.g. 0.10); 0.08206 is the gas constant; Ta is the ambient temperature (°C); PB is barometric pressure (mmHg); and FCO is the fraction of CO in the gas mixture (i.e. 0.95).

where 0.978 is the correction factor for CO remaining in the lung-bag system after equilibration with the blood; DnCO (mmol) is the ratio between the estimated total [Hb] and the desired increase in carboxyhaemoglobin (FCOHb; e.g. 0.10); 0.08206 is the gas constant; Ta is the ambient temperature (°C); PB is barometric pressure (mmHg); and FCO is the fraction of CO in the gas mixture (i.e. 0.95).

Blood O2 content (ml l−1) was calculated as (1.39 × [Hb] × O2 saturation) + (0.003 × PO2). LBF and blood parameters represent the mean of the samples obtained at 2 and 4 min of exercise when these parameters had reached a plateau level. Leg O2 uptake (leg  ) was calculated by multiplying the mean LBF by the difference in concentration of O2 between the femoral artery and vein (a-vO2 difference). Leg O2 delivery was calculated by multiplying the mean LBF by the femoral arterial O2 content. The ratio between the femoral a-vO2 difference and arterial O2 concentration was calculated as the index of O2 extraction. P50, defined as the PO2 where 50% of the haemoglobin binding sites are bound with O2, was calculated using the following formula (Perego et al. 1996):

) was calculated by multiplying the mean LBF by the difference in concentration of O2 between the femoral artery and vein (a-vO2 difference). Leg O2 delivery was calculated by multiplying the mean LBF by the femoral arterial O2 content. The ratio between the femoral a-vO2 difference and arterial O2 concentration was calculated as the index of O2 extraction. P50, defined as the PO2 where 50% of the haemoglobin binding sites are bound with O2, was calculated using the following formula (Perego et al. 1996):

where Sat is the O2 saturation and n = 2.7. Heart rate and MABP were calculated as the mean response over the 5 min exercise period.

where Sat is the O2 saturation and n = 2.7. Heart rate and MABP were calculated as the mean response over the 5 min exercise period.

Statistical analysis

A one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to test the significance between and within treatments. Following a significant F test, pair-wise differences were identified using Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc procedure. When appropriate, significant differences were also identified using Student's paired t tests. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

Interventions

During exercise, systemic hypoxia reduced Ca,O2 by 17% compared to normoxia, as a result of the 16% reduction in oxyhaemoglobin and a 45% fall in Pa,O2 (Table 1). The administration of CO in combination with normoxia or hyperoxia increased FCOHb to 18-19% (1.6-1.7 mmol l−1) from 2-3% (0.2-0.3 mmol l−1) in normoxia and hypoxia. The administration of CO in combination with normoxia reduced Ca,O2 by 18% due only to reduced oxyhaemoglobin, while the inhalation of CO in combination with hyperoxia reduced Ca,O2 by 12% as a result of the 19% decline in oxyhaemoglobin and the 5-fold increase in Pa,O2. In all trials, the a-vCOHb difference was zero indicating that there was no net CO exchanged across the leg. However, CO inhalation resulted in a leftward shift in the oxyhaemoglobin curve as reflected by the decline in P50 from 26 ± 1 mmHg in normoxia and hypoxia to 20 ± 1 mmHg in the CO trials and the concurrent reduction in the Hill coefficient, nH, from 2.7 ± 0.1 to 2.1 ± 0.1 (both P < 0.05). However, total haemoglobin concentration, haematocrit and blood temperature (≈37.1°C from 2 to 5 min of exercise) were similar in all conditions at rest and during exercise (Table 1).

Table 1.

Haematological responses to submaximal one-legged knee-extensor exercise under normoxia (FI,O2, 21%), hypoxia (FI,O2, ∼12%), CO breathing combined with normoxia, and CO breathing combined with hyperoxia (FI,O2, 90–99%)

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | CO + normoxia | CO + hyperoxia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Hb]a (mmol l-1) | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 8.8 ± 0.1 | 8.9 ± 0.2 |

| [Hb]v mmol l-1 | 9.1 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.2 | 8.8 ± 0.2 | 8.7 ± 0.2*† |

| Hcta (%) | 45.3 ± 1.0 | 45.6 ± 1.0 | 45.0 ± 0.9 | 44.9 ± 0.7 |

| Hctv (%) | 45.7 ± 1.0 | 45.6 ± 1.0 | 45.0 ± 1.1 | 44.8 ± 0.6 |

| COHba (%) | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 18.4 ± 1.2*† | 19.4 ± 1.2*† |

| COHbv (%) | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 18.4 ± 1.2*† | 19.5 ± 1.2*† |

| O2Hba (ml l-1) | 195 ± 3 | 163 ± 5* | 159 ± 3* | 158 ± 4* |

| O2Hbv (ml l-1) | 63 ± 2 | 50 ± 4* | 61 ± 1† | 66 ± 2† |

| Pa,O2 (mmHg) | 105 ± 3 | 47 ± 3* | 119 ± 4† | 538 ± 19*† |

| Pv,O2 (mmHg) | 22 ± 1 | 18 ± 1* | 18 ± 1* | 19 ± 1* |

| Ca,O2 (ml l-1) | 198 ± 3 | 165 ± 5* | 162 ± 3* | 174 ± 5* |

| Cv,O2 (ml l-1) | 64 ± 2 | 51 ± 4* | 62 ± 1† | 67 ± 2† |

| Sa,O2 (%) | 97.9 ± 0.1 | 82.6 ± 3.6* | 98.6 ± 0.2† | 99.8 ± 0.1† |

| Sv,O2 (%) | 31.7 ± 0.5 | 25.7 ± 2.4* | 38.4 ± 0.6*† | 42.2 ± 1.1*† |

| Pa,CO2 (mmHg) | 40.5 ± 0.9 | 35.2 ± 1.0* | 38.4 ± 1.5 | 36.8 ± 0.8* |

| Pv,CO2 (mmHg) | 62.1 ± 1.3 | 52.3 ± 1.4* | 54.0 ± 2.4* | 54.1 ± 1.5* |

| pHa | 7.39 ± 0.01 | 7.44 ± 0.01 | 7.40 ± 0.01 | 7.41 ± 0.01 |

| pHv | 7.30 ± 0.01 | 7.34 ± 0.01 | 7.31 ± 0.02 | 7.32 ± 0.01 |

| []a (mmol l-1) | 24 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 |

| []v (mmol l-1) | 28 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 | 27 ± 1 |

| ABEa (mmol l-1) | −1 ± 1 | −1 ± 1 | −1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 |

| ABEv (mmol l-1) | 1 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 0 ± 1 | 1 ± 1 |

Values are means ± s.e.m. for 7 subjects. [Hb], total haemoglobin concentration; Hct, haematocrit; COHb, carboxyhaemoglobin; O2Hb, oxyhaemoglobin; CO2, total oxygen content of blood; SO2, oxygen saturation; ABE, actual base excess. Subscripts a and v denote arterial and venous, respectively.

Significantly different from normoxia (P < 0.05).

Significantly different from hypoxia (P < 0.05).

Haemodynamics

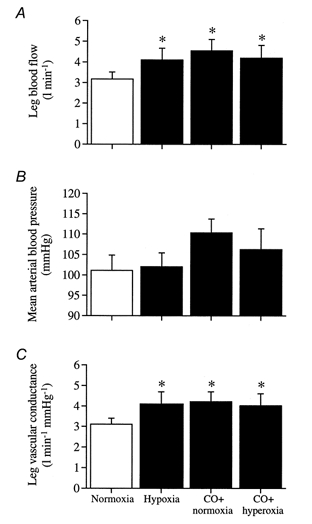

With CO + normoxia, CO + hyperoxia and systemic hypoxia, LBF increased 1.0-1.4 l min−1 (32-44%) above the 3.1 ± 0.3 l min−1 observed in normoxia (P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). The elevation in LBF with systemic hypoxia and CO inhalation was already present after the first minute of exercise (2.9 ± 0.3, 3.6 ± 4, 4.0 ± 0.4 and 3.9 ± 0.7 l min−1 during normoxia, hypoxia, CO + normoxia and CO + hyperoxia, respectively). MABP was unaltered by systemic hypoxia but tended to increase in CO trials (mean change range, 6-10 mmHg; P = 0.17; Fig. 2B). Leg vascular conductance was elevated by 29-35% with both CO conditions and hypoxia compared to normoxia (P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). Compared to normoxia, heart rate was elevated with hypoxia (86 ± 2 vs. 95 ± 3 beats min−1, respectively; P < 0.05), but was not significantly different in the CO trials (86 ± 3 and 90 ± 3 beats min−1 in CO + normoxia and CO + hyperoxia, respectively).

Figure 2. Blood flow and blood pressure responses to submaximal one-legged knee-extensor exercise with normoxia, hypoxia and CO breathing combined with normoxia and hyperoxia.

A, leg blood flow. B, mean arterial blood pressure. C, leg vascular conductance. *Significantly higher than normoxia (P < 0.05).

Leg a-vO2 difference declined from 134 ± 2 ml l−1 in normoxia to 113 ± 3 ml l−1 with hypoxia, 100 ± 2 ml l−1 with CO + normoxia and 106 ± 4 ml l−1 with CO + hyperoxia (all P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Leg O2 delivery increased in both CO trials (15-18%; P < 0.05) in proportion to the reduction in O2 extraction compared to normoxia (Fig. 3B and C). However, leg O2 delivery and extraction were unchanged by hypoxia. Neither CO administration nor systemic hypoxia altered leg VO2 (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Oxygen parameters measured during submaximal one-legged knee-extensor exercise with normoxia, hypoxia and CO breathing combined with normoxia and hyperoxia.

A, leg femoral arterial-to-venous oxygen difference (a-vO2 diff). B, leg oxygen delivery. C, leg oxygen extraction. D, leg oxygen uptake (VO2). *Significantly different from normoxia (P < 0.05).

Acid-base balance, metabolite and electrolyte responses

No significant differences in arterial or femoral venous blood pH, bicarbonate, base excess, lactate, glucose, K+, Na+, Cl− or Ca2+ were observed between trials either at rest or during exercise (see Tables 1 and 2 for exercise values). Furthermore, there was no net lactate release during exercise in either condition (2.39 ± 1.36, 2.70 ± 0.76, 2.16 ± 0.79 and 2.63 ± 1.58 mmol min−1 in normoxia, hypoxia, CO + normoxia and CO + hyperoxia, respectively; P = 0.84).

Table 2.

Blood electrolyte, metabolite and catecholamine concentrations during submaximal one-legged knee-extensor exercise under normoxia (FI,O2, 21%), hypoxia (FI,O2, ∼12%), CO breathing combined with normoxia, and CO breathing combined with hyperoxia (FI,O2, 90–99%)

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | CO + normoxia | CO + hyperoxia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mmol l-1) | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.3 |

| (mmol l-1) | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.2 |

| (mmol l-1) | 138 ± 1 | 138 ± 1 | 137 ± 1 | 138 ± 1 |

| (mmol l-1) | 140 ± 1 | 140 ± 1 | 139 ± 1 | 139 ± 1 |

| (mmol l-1) | 107 ± 1 | 107 ± 2 | 107 ± 1 | 107 ± 1 |

| (mmol l-1) | 105 ± 2 | 106 ± 2 | 106 ± 2 | 106 ± 1 |

| (mmol l-1) | 1.21 ± 0.03 | 1.20 ± 0.03 | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 1.19 ± 0.04 |

| (mmol l-1) | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 1.24 ± 0.02 | 1.22 ± 0.02 | 1.21 ± 0.05 |

| Lactatea (mmol l-1) | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.4 |

| Lactatev (mmol l-1) | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.7 |

| Glucosea (mmol l-1) | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.5 |

| Glucosev (mmol l-1) | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.5 |

| Noradrenalinea (nmol l-1) | 1.51 ± 0.10 | 1.90 ± 0.22 | 1.92 ± 0.22 | 2.05 ± 0.11* |

| Adrenalinea (nmol l-1) | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 1.01 ± 0.30 | 0.72 ± 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.15 |

Values are means ± s.e.m. for 7 subjects.

Significantly higher than Normoxia (P < 0.05).

Catecholamines

After 5 min of exercise, arterial noradrenaline concentration was significantly higher with CO + hyperoxia compared to normoxia (2.1 ± 0.1 vs. 1.5 ± 0.1 nmol l−1, respectively; see Table 2). A trend for a higher arterial noradrenaline concentration was also observed with CO + normoxia and systemic hypoxia compared to normoxia (1.9 ± 0.2 and 1.9 ± 0.2 vs. 1.5 ± 0.1 nmol l−1, respectively). Arterial adrenaline concentration during exercise was similar in all conditions (0.6 ± 0.2, 1.0 ± 0.3, 0.7 ± 0.2 and 0.7 ± 0.1 nmol l−1 in normoxia, hypoxia, CO + normoxia and CO + hyperoxia, respectively; P = 0.23).

Additional experiments

Progressive reductions in O2Hba produced by graded increases in COHba (1.8 ± 0.1, 9.1 ± 0.6 and 15.7 ± 0.8% COHba) under normoxic conditions (Pa,O2=≈115 mmHg) resulted in a 28-45% higher LBF and leg vascular conductance compared to the control condition (P < 0.05; Fig. 6). Arterial lactate concentration (mean range, 1.4-1.5 mmol l−1), heart rate (85-87 beats min−1), MABP (129-130 mmHg) and leg oxygen uptake (540-600 ml min−1) were similar in all conditions. On the other hand, the injection of l-NMMA to block NO synthase activity did not attenuate the CO- or systemic hypoxia-evoked muscle vasodilatation in the two subjects studied (see Fig. 7).

Figure 6. Effect of graded reductions in arterial oxyhaemoglobin on skeletal muscle haemodynamics during submaximal one-legged knee-extensor exercise.

A, leg blood flow. B, mean arterial blood pressure. C, leg vascular conductance. The progressive reductions in arterial oxyhaemoglobin (O2Hb) were produced by graded increases in carboxyhaemoglobin (COHb), i.e. 1.8 ± 0.1, 9.1 ± 0.6 and 15.7 ± 0.8% COHb, when Pa,O2 was maintained between 113 and 117 mmHg. Data are means ±s.e. for 4 subjects.

Figure 7. Effect of NO synthase blockade on skeletal muscle haemodynamics during submaximal one-legged knee-extensor exercise when exposed to systemic hypoxia and CO combined with normoxia.

A, leg blood flow. B, mean arterial blood pressure. C, leg vascular conductance. Two subjects underwent this follow-up study showing no effect of NO synthase blockade on skeletal muscle haemodynamics. Data from one of the subjects are depicted.

DISCUSSION

This study tested the hypothesis that the amount of O2 bound to haemoglobin in arterial blood plays a greater role than that of dissolved O2 in the regulation of human skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise. We found that arterial oxyhaemoglobin equally reduced with either CO in combination with hyperoxia or hypoxia resulted in similar increases in exercising knee-extensor muscle blood flow and vascular conductance, despite an 11-fold difference in Pa,O2. This increased leg vasodilatation occurred in the face of unaltered blood pH, leg net lactate release and acid-base balance, and was closely related to the fall in oxyhaemoglobin. These results support the concept that the red blood cell itself plays a crucial role in the regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow during exercise, possibly by sensing O2 availability within the erythrocyte itself.

This is the first study that has separated the effects of oxyhaemoglobin and Pa,O2 on contracting human skeletal muscle blood flow and local vascular conductance by combining CO and normoxic or hyperoxic air breathing in comparison to normoxia and hypoxia. The majority of previous human studies involving a reduction in arterial O2 content with anaemia, hypoxia or combined anaemia and hypoxia, although not independently manipulating Pa,O2, show reciprocal elevations in cardiac output and active muscle blood flow and higher leg vascular conductance during knee-extensor exercise and cycle ergometer exercise (Rowell et al. 1986; Knight et al. 1993; Richardson et al. 1995; Koskolou et al. 1997a, b; Roach et al. 1999; Kjær et al. 1999). Conversely, elevated arterial O2 content evoked by systemic hyperoxia is associated with reduced (Welch et al. 1977) or unchanged (Knight et al. 1993) muscle blood flow and vascular conductance during cycle ergometer exercise. Together these results therefore show a close inverse linear relationship between alterations in arterial O2 content and changes in skeletal muscle blood flow during submaximal exercise (Roach et al. 1999). In determining the primary signalling for vasodilatation, Roach et al. (1999) observed that cardiac output, LBF and arterial O2 delivery to contracting skeletal muscle with normoxia, anaemia, hypoxia and anaemia + hypoxia were closely linked to the magnitude of arterial O2 content. Arguing against a major role of dissolved O2 in muscle blood flow regulation, they observed similar LBF and leg vascular conductance when Pa,O2 varied from ≈40 mmHg with hypoxia to ≈105 mmHg with anaemia. This was clearly demonstrated to an even greater extent in the present study where the increased LBF and leg vascular conductance were tightly coupled to the level of arterial oxyhaemoglobin, regardless of a normal or an 11-fold difference in Pa,O2 (47 vs. 538 mmHg). Therefore, previous (Koskolou et al. 1997a, b; Roach et al. 1999; Calbet et al. 1999) and the present results from this laboratory do not support the idea that dissolved O2 in arterial blood exerts, by itself, a measurable effect on the vascular smooth muscle of exercising humans in vivo. This is in agreement with the classical in vitro observation that hypoxia does not relax pig carotid artery unless the core of the blood vessel wall is virtually anoxic (Pittman & Duling, 1973).

Even though this is the first study on contracting human skeletal muscle haemodynamics with systemic CO exposure, previous reports indicate that cardiac output at rest and during exercise is elevated with the lower arterial oxygenation associated with accompanying elevated carboxyhaemoglobin levels (> 33%) in humans (Chiodi et al. 1941; Vogel & Gleser, 1972), dogs (Asmussen & Vinther-Paulsen, 1949; Sylvester et al. 1979) and rats (Penney et al. 1979; Kanten et al. 1983). However, in this study with lower carboxyhaemoglobin values (≈18%), heart rate did not increase above the normoxic levels. This is in contrast to the 13% higher heart rate with hypoxia, thus suggesting that reduced circulating free O2 is intimately linked to the elevation in heart rate with systemic hypoxia. Collectively, it seems possible that the increased active skeletal muscle blood flow with CO breathing observed here was related, at least in part, to an increased cardiac output via an elevated stroke volume (Sylvester et al. 1979; Penney et al. 1979; Kanten et al. 1983).

The mechanism/s underlying the elevated skeletal muscle vasodilatation with CO inhalation and systemic hypoxia in humans is/are unclear. The present observation that blood pH, blood K+, blood Ca2+, blood temperature, muscle lactate release, blood bicarbonate and blood acid-base balance were unaltered by CO inhalation and systemic hypoxia during light exercise suggests that the exhibited vasodilatation was not triggered by any of these vasodilators. This is also consistent with the observation that CO increased LBF by 44% in two subjects during passive exercise, when the muscle chemoreflex is generally thought to be unchanged. There is compelling evidence in vitro demonstrating that CO increases the perfusion of isolated hearts (McFaul & McGrath, 1987), vasodilates the aorta (Coburn, 1979), and relaxes guinea-pig ileal and ductus arteriosus smooth muscle (Conceani et al. 1984; Utz & Ullrich, 1991). Therefore, it is not clear from our experiments to what extent the enhanced leg vasodilatation resulted from direct or indirect effects of CO on the vascular smooth muscle of vessels perfusing the muscles. CO is thought to cause vasodilatation in a similar manner to NO; namely, by activation of guanylate cyclase (Arnold et al. 1977; Utz & Ullrich, 1991). Although we cannot rule out a direct effect of CO, the tight correlation between skeletal muscle blood flow and vascular conductance and arterial oxyhaemoglobin (see Fig. 6) as well as the strikingly similar response with no CO present (see Figs 4A and 5A) favour the idea that the effect of CO was predominantly the result of a simple reduction in available haemoglobin.

Figure 4. Relationship between leg blood flow and arterial blood oxygen.

A, rise in leg blood flow with reduced oxyhaemoglobin concentration induced by hypoxia and carbon monoxide inhalation under normoxic and hyperoxic conditions. B, lack of relationship between the rise in leg blood flow and the alterations in arterial PO2. C, rise in leg blood flow with reduced arterial oxygen content.

Figure 5. Relationship between leg vascular conductance and arterial blood oxygen.

A, rise in leg vascular conductance with reduced oxyhaemoglobin concentration induced by hypoxia and carbon monoxide inhalation under normoxic and hyperoxic conditions. B, lack of relationship between the rise in leg vascular conductance and the alterations in arterial PO2. C, rise in leg vascular conductance with reduced arterial oxygen content.

The concept that the red blood cell participates in the regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow is consistent with two recently proposed molecular mechanisms by which reduced oxyhaemoglobin leads to vasodilatation in vitro (Ellsworth et al. 1995; Jia et al. 1996; Stamler et al. 1997). Diminished oxygenation is thought to evoke vasodilatation in vitro by stimulating the release of ATP from the erythrocyte, which in turns binds to purinergic receptors (P2y) in the vascular endothelium, resulting in a NO- and/or endothelium-derived hyperpolarization factor-mediated vasodilatory response (Ellsworth et al. 1995). In the same light, it has been suggested that haemoglobin deoxygenation promotes the release of NO from the S-nitrosohaemoglobin molecule (SNOHb), allowing the diffusion of the NO group to the vascular endothelium where it stimulates vessel relaxation (Jia et al. 1996; Stamler et al. 1997). Interestingly, the present observation that leg vasodilatation in response to systemic hypoxia, CO + hyperoxia and CO + normoxia was rather similar raises the question as to whether NO mediated the elevation in muscle perfusion during exercise with equally reduced arterial oxygenation. The observation that the injection of l-NMMA, a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, did not attenuate the CO- or systemic hypoxia-evoked muscle vasodilatation during exercise in two subjects argues against the involvement of NO (Fig. 7), conforming to findings in humans exercising under normoxic conditions (Rådegran & Saltin, 1999). l-NMMA primarily blocks the endothelial NO synthase, thus the possibility that NO release from the erythrocyte mediated the persistent vasodilatation cannot be completely excluded. Yet, the NO release from the erythrocyte is quantitatively less important as the endogenous SNOHb to Hb ratio is only 1:1000 and the effective diffusion distance of NO to the site of action in the vascular smooth muscle cells is greater than the equilibrium constant of the target enzyme guanylate cyclase (Vaughn et al. 1998). Alternatively, recent evidence in humans (MacLean et al. 1998; Leuenberger et al. 1999) and rats (Mian & Marshall, 1991) suggests that adenosine plays a major role in stimulating skeletal muscle vasodilatation during acute systemic hypoxia. Other vasoactive factors such as ATP, prostaglandins, bradykinins and K+ might also contribute (Marshall, 2000). At present, evidence for such mechanisms with CO exposure in humans is lacking.

We have focused on the influence of altered arterial oxygenation in the regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow. However, the observation that leg O2 delivery was enhanced in the CO trial in association with diminished leg O2 extraction raises the possibility that skeletal muscle blood flow regulation is sensitive not only to alterations in arterial oxygenation, but also to peripheral changes in the affinity of haemoglobin for O2. In the CO trials, femoral venous O2 saturation (38-42%) was significantly higher compared to normoxia (32%) and hypoxia (25%), and LBF particularly during CO + normoxia was some 0.5 l min−1 higher than in the hypoxic trial in association with the 10 mmHg elevation in MABP. A similar elevation in O2 delivery was achieved in the CO + hyperoxia condition resulting from the increased blood flow and slightly greater arterial O2 content accompanying the greatly enhanced Pa,O2 with equivalent levels of oxyhaemoglobin (Table 1). Although in the femoral venous circulation, oxyhaemoglobin was higher in the CO trials compared to systemic hypoxia, PO2 was remarkably similar (18-19 mmHg). Taken as a whole, these observations of an elevation in O2 delivery and venous oxyhaemoglobin with CO inhalation refute the concept that limb blood flow is regulated simply to maintain O2 delivery to the contracting muscle, and provide indirect evidence to suggest that O2 off-loading from haemoglobin is also sensed.

An interesting observation in this study was the maintenance of leg  with moderate carboxyhaemoglobinaemia during submaximal knee-extensor exercise. This resulted from the compensatory increase in O2 delivery counteracting the decline in O2 extraction. The fall in O2 extraction produced by CO was associated with an increase in the affinity of haemoglobin for O2, and thus attenuated O2 off-loading, resulting from a leftward shift in the haemoglobin dissociation curve as indicated by a ≈23% reduction in P50 and nH in the CO trials compared to both normoxia and hypoxia. The alternative hypothesis that CO impaired the diffusion of dissolved O2 to the mitochondria appears unlikely based on the finding that O2 extraction was the same in both CO trials (60%) despite pronounced differences in the O2 gradient. It might be expected that CO inhalation would produce some degree of myoglobin CO saturation. However, it can be inferred from the observation that CO exchange across the leg was zero in all trials that myoglobin CO saturation was not markedly enhanced by CO inhalation. Collectively, the finding that leg

with moderate carboxyhaemoglobinaemia during submaximal knee-extensor exercise. This resulted from the compensatory increase in O2 delivery counteracting the decline in O2 extraction. The fall in O2 extraction produced by CO was associated with an increase in the affinity of haemoglobin for O2, and thus attenuated O2 off-loading, resulting from a leftward shift in the haemoglobin dissociation curve as indicated by a ≈23% reduction in P50 and nH in the CO trials compared to both normoxia and hypoxia. The alternative hypothesis that CO impaired the diffusion of dissolved O2 to the mitochondria appears unlikely based on the finding that O2 extraction was the same in both CO trials (60%) despite pronounced differences in the O2 gradient. It might be expected that CO inhalation would produce some degree of myoglobin CO saturation. However, it can be inferred from the observation that CO exchange across the leg was zero in all trials that myoglobin CO saturation was not markedly enhanced by CO inhalation. Collectively, the finding that leg  was maintained and net lactate release was unchanged with moderate levels of carboxyhaemoglobin strongly supports the notion that moderate CO intoxication does not impair net skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration during submaximal exercise in humans. It is clear, however, that severe carboxyhaemoglobinaemia (65-88% carboxyhaemoglobin), induced in in vitro preparations, in situ perfused myocardium and in vivo animal studies, hampers muscle respiration by possibly blocking cytochrome c oxidase (King et al. 1987; Brown & Piantadosi, 1992; Glabe et al. 1998; Thom et al. 1999). The involvement of cytochrome c oxidase in exercising humans exposed to moderate carboxyhaemoglobinaemia could be assessed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Richardson et al. 1995), and a lack of carboxymyoglobin would rule out a role of cytochrome c oxidase and myoglobin.

was maintained and net lactate release was unchanged with moderate levels of carboxyhaemoglobin strongly supports the notion that moderate CO intoxication does not impair net skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration during submaximal exercise in humans. It is clear, however, that severe carboxyhaemoglobinaemia (65-88% carboxyhaemoglobin), induced in in vitro preparations, in situ perfused myocardium and in vivo animal studies, hampers muscle respiration by possibly blocking cytochrome c oxidase (King et al. 1987; Brown & Piantadosi, 1992; Glabe et al. 1998; Thom et al. 1999). The involvement of cytochrome c oxidase in exercising humans exposed to moderate carboxyhaemoglobinaemia could be assessed by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Richardson et al. 1995), and a lack of carboxymyoglobin would rule out a role of cytochrome c oxidase and myoglobin.

In conclusion, contracting human muscle blood flow and vascular conductance during submaximal knee-extensor exercise is tightly coupled with the fall in arterial oxyhaemoglobin, and seems largely independent of oxygen dissolved in the blood (range, 47-538 mmHg). Increased muscle vasodilatation was unrelated to vasoactive effects of H+ and K+, since it occurred in the face of unaltered blood pH, leg lactate release, acid-base balance and circulating K+ concentration. Enhanced muscle vasodilatation also occurred despite the ≈30% higher circulating noradrenaline concentration, which possibly underlies an elevation in vasoconstrictor sympathetic nerve activity. Furthermore, the lack of effect of l-NMMA infusion suggests that endothelial NO may not mediate the enhanced muscle vasodilatation with reduced oxyhaemoglobin. Increased blood flow and oxygen delivery to the exercising leg afford the maintenance of muscle oxygen uptake and thus muscle mitochondrial respiration during submaximal exercise, despite a lower O2 extraction that appears to be largely related to reduced O2 off-loading from haemoglobin in the presence of CO.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are given to Dr Poul Christensen for the loan of his equipment and for help in initiating this project. The excellent technical assistance of Carsten Nielsen, Karin Hansen and Birgitte Jessen is acknowledged. We also would like to thank Dr Mikael Sender and Dr Goran Rdegran for their help during the l-NMMA infusion experiments. This study was supported by a grant from The Danish National Research Foundation (504-14). R. S. R. was on leave from the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Diego, USA, and was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, USA (HL 17731).

References

- Andersen P, Saltin B. Maximal perfusion of skeletal muscle in man. Journal of Physiology. 1985;366:233–249. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WP, Mittal CK, Katsuki S, Murad F. Nitric oxide activates guanylate cyclase and increases guanosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate levels in various tissue preparations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1977;74:3203–3207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.8.3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmussen E, Nielsen M. The cardiac output in rest and work at low and high oxygen pressures. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1955;35:73–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1955.tb01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmussen E, Vinther-Paulsen N. On the circulatory adaptations to arterial hypoxemia (CO-poisoning) Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1949;19:115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Baron JF, Vicaut E, Hou X, Duvelleroy M. Independent role of arterial O2 tension in local control of coronary blood flow. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;258:H1388–1394. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.5.H1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Piantadosi CA. Recovery of energy metabolism in rat brain after carbon monoxide hypoxia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1992;89:666–672. doi: 10.1172/JCI115633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calbet JAL, Rådegran G, Boushel R, Søndergaard H, Wagner PD, Saltin B. Is acclimation induced polycythemia an advantage for maximal exercise performance under hypoxic conditions in humans? FASEB Journal. 1999;13:LB53. [Google Scholar]

- Chiodi H, Dill DB, Consolazio F, Horvath SM. Respiratory and circulatory responses to acute carbon monoxide poisoning. American Journal of Physiology. 1941;134:683–693. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P, Rasmussen JW, Henneberg SW. Accuracy of a new bedside method for estimation of circulating blood volume. Clinical Care Medicine. 1993;21:1535–1540. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199310000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn RF. Mechanism of carbon monoxide toxicity. Preventive Medicine. 1979;8:3310–3322. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(79)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coceani F, Hamilton NC, Labuc J, Olley PM. Cytochrome P45-linked monooxygenase: involvement in the lamb ductus arteriosus. American Journal of Physiology. 1984;246:H640–643. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.4.H640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas CG, Haldane JS, Haldane JBS. The law of combination of haemoglobin with carbon monoxide and oxygen. Journal of Physiology. 1912;44:275–304. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1912.sp001517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth ML, Forrester T, Ellis CG, Dietrich HH. The erythrocyte as a regulator of vascular tone. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:H2155–2161. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.6.H2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe A, Chung Y, Xu D, Jue T. Carbon monoxide inhibition of regulatory pathways in myocardium. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:H2143–2151. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.6.H2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Alonso J, Calbet JAL, Nielsen B. Muscle blood flow is reduced with dehydration during prolonged exercise in humans. Journal of Physiology. 1998;513:895–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.895ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane JS. The dissociation of oxyhaemoglobin in human blood during partial CO poisoning. Journal of Physiology. 1912;45:22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman H, Farnebo LO, Hamberger B, Jonsson G. A sensitive method for the determination of plasma catecholamines using liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Life Science. 1978;23:1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(78)90665-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WF. Arteriolar oxygen reactivity: where is the sensor? American Journal of Physiology. 1987;253:H1120–1126. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Bonaventura C, Bonaventura J, Stamler J. S-nitrosohaemoglobin: a dynamic activity of blood involved in vascular control. Nature. 1996;380:221–226. doi: 10.1038/380221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanten WE, Penney DG, Francisco K, Thill JE. Hemodynamic responses to acute carboxyhemoglobinemia in the rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1983;244:H320–327. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.3.H320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CE, Dodd SL, Cain SM. Oxygen delivery to contracting muscle during hypoxia and CO hypoxia. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1987;63:726–732. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.2.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjær M, Hanel B, Worm L, Perko G, Lewis SF, Sahlin K, Galbo H, Secher NH. Cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responses to exercise in hypoxia during impaired neural feedback from muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:R76–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.1.R76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DR, Schffartizik W, Poole DC, Hogan MC, Bebout DE, Wagner P. Effects of hyperoxia on maximal leg O2 supply and utilization in man. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1993;75:2586–2594. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.6.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskolou MD, Calbet JAL, Rådegran G, Roach RC. Hypoxia and the cardiovascular response to dynamic knee-extensor exercise. American Journal of Physiology. 1997a;272:H2655–2663. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskolou MD, Roach RC, Calbet JAL, Rådegran G, Saltin B. Cardiovascular responses to dynamic exercise with acute anemia in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1997b;273:H1787–1793. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.H1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenbenger UA, Gray K, Herr MD. Adenosine contributes to hypoxia-induced forearm vasodilation in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1999;87:2218–2224. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFaul SJ, McGrath JJ. Studies on the mechanism of carbon monoxide-induced vasodilation in the perfused heart. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1987;87:464–467. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(87)90252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean DA, Sinoway LI, Leuenberger U. Systemic hypoxia elevates skeletal muscle interstitial adenosine levels in humans. Circulation. 1998;98:1990–1992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.19.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JM. Adenosine and muscle vasodilatation in acute systemic hypoxia. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2000;168:561–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mian R, Marshall JM. The role of adenosine in dilator responses induced in arterioles and venules of rat skeletal muscle in systemic hypoxia. Journal of Physiology. 1991;443:499–511. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace N, Strajman E, Walker EL. Acceleration of carbon monoxide elimination in man by high pressure oxygen. Science. 1950;111:652–654. doi: 10.1126/science.111.2894.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penney DG, Sodt PC, Cutilleta A. Cardiodynamic changes during prolonged carbon monoxide exposure in the rat. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1979;50:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(79)90146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego GB, Marenzi GC, GuaIZZ M, Sganzerla P, Assanelli E, Palermo P, Conconi B, Lauri G, Agostini PG. Contribution of PO2, P50, and Hb to changes in arteriovenous O2 content during exercise in heart failure. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1996;80:623–631. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.2.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi CA. Carbon monoxide, oxygen transport and oxygen metabolism. Journal of Hyperbaric Medicine. 1987;2:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pittman RN, Duling BR. Oxygen sensitivity of vascular smooth muscle. Microvascular Research. 1973;6:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(73)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pries AR, Heide J, Ley K, Klotz K-F, Gaehtgens P. Effect of oxygen tension on regulation of arterial diameter in skeletal muscle in situ. Microvascular Research. 1995;49:289–299. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1995.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rådegran G, Saltin B. Nitric oxide in the regulation of vasomotor tone in human skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:H1951–1960. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson RS, Noyszewski EA, Kendrick KF, Leigh JS, Wagner PD. Myoglobin O2 desaturation during exercise: evidence of limited O2 transport. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;96:1916–1926. doi: 10.1172/JCI118237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach RC, Koskolou MD, Calbet JAL, Saltin B. Arterial O2 content and tension in regulation of cardiac output and leg blood flow during exercise in humans. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:H438–445. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Saltin B, Kiens B, Christiansen NJ. Is peak quadriceps blood flow in humans even higher during exercise in hypoxemia? American Journal of Physiology. 1986;251:H1038–1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.5.H1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggaard-Andersen O. The Acid-Base Status of Blood. 4. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Jia L, Eu JP, McMahon TJ, Demchenko IT, Bonaventura J, Gernert K, Piantadosi CA. Blood flow regulation by S-nitrosohemoglobin in the physiological oxygen gradient. Science. 1997;276:2034–2037. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester JT, Scharf SM, Gilbert RD, Fitzgerald RS, Traystman JT. Hypoxic and CO hypoxia in dogs: hemodynamics, carotic reflexes, and catecholamines. American Journal of Physiology. 1979;236:H22–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.1.H22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom SR, Fisher D, Xu YA, Garner S, Ischiropoulos H. Role of nitric oxide-derived oxidants in vascular injury from carbon monoxide in the rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:H984–992. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.3.H984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz J, Ullrich V. Carbon monoxide relaxes ileal smooth muscle through activation of guanylate cyclase. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1991;41:1195–1201. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90658-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn MW, Kuo L, Liao JC. Effective diffusion distance of nitric oxide in the microcirculation. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:H1705–1714. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel JA, Gleser M. Effect of carbon monoxide on oxygen transport during exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1972;32:234–239. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch HG, Bonde-Petersen F, Graham T, Klausen K, Secher N. Effects of hyperoxia on leg blood flow and metabolism during exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1977;42:385–390. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.42.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]