Abstract

The water transport properties of the human Na+-coupled glutamate cotransporter (EAAT1) were investigated. The protein was expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes and electrogenic glutamate transport was recorded by two-electrode voltage clamp, while the concurrent water transport was monitored as oocyte volume changes.

Water transport by EAAT1 was bimodal. Water was cotransported along with glutamate and Na+ by a mechanism within the protein. The transporter also sustained passive water transport in response to osmotic challenges. The two modes could be separated and could proceed in parallel.

The cotransport modality was characterized in solutions of low Cl− concentration. Addition of glutamate promptly initiated an influx of 436 ± 55 water molecules per unit charge, irrespective of the clamp potential.

The cotransport of water occurred in the presence of adverse osmotic gradients. In accordance with the Gibbs equation, energy was transferred within the protein primarily from the downhill fluxes of Na+ to the uphill fluxes of water.

Experiments using the cation-selective ionophore gramicidin showed no unstirred layer effects. Na+ currents in the ionophore did not lead to any significant initial water movements.

In the absence of glutamate, EAAT1 contributed a passive water permeability (Lp) of (11.3 ± 2.0) × 10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1. In the presence of glutamate, Lp was about 50 % higher for both high and low Cl− concentrations.

The physiological role of EAAT1 as a molecular water pump is discussed in relation to cellular volume homeostasis in the nervous system.

Cotransporters are membrane proteins in which the transmembrane fluxes of various substrates are coupled: the downhill flux of one substrate energizes the uphill flux of another. Evidence is accruing, however, that cotransporters, in addition to their recognized functions, also play a direct role in water transport. All cotransporters of the symport type tested so far exhibit cotransport of water, in which a fixed number of water molecules are translocated together with non-aqueous substrates by a process that is independent of external parameters. In addition, the cotransporters can function as passive water channels. The K+-Cl− and H+-lactate cotransporters have been found to cotransport 500 water molecules per turnover (Zeuthen, 1991, 1994; Zeuthen et al. 1996). The human Na+-glucose cotransporter, the rabbit Na+-glucose cotransporter and the Na+-dicarboxylate cotransporter cotransport 210, 390 and 175 water molecules per turnover, respectively (Loo et al. 1996; Zeuthen et al. 1997; Meinild et al. 1998, 2000). Osmotic water transport has been described in detail for the Na+-glucose and the Na+-GABA transporters (Loike et al. 1996; Loo et al. 1996; Loo et al. 1999b).

Here we study the water transport properties of a Na+-amino acid cotransporter, the human glutamate transporter EAAT1. This protein is primarily found in glial cells (Rothstein et al. 1994; Lehre et al. 1995) but its location in peripheral tissue has also been reported (Arriza et al. 1994). Glutamate serves a variety of physiological functions. Besides its role as a constituent of proteins, glutamate is also one of the most abundant neurotransmitters in the mammalian central nervous system. Five different isoforms of the human glutamate transporter (EAAT1-5) have been cloned (Arriza et al. 1994; Fairman et al. 1995; Arriza et al. 1997). It is well established that the cotransporter is electrogenic (Brew & Attwell, 1987), yet the exact stoichiometry is disputed. The cotransport of two Na+ (Stallcup et al. 1979; Erecinska et al. 1986) or three Na+ (Barbour et al. 1988; Zerangue & Kavanaugh, 1996) has been suggested. This is associated with cotransport of H+ (Nelson et al. 1983; Zerangue & Kavanaugh, 1996) and accompanied by countertransport of K+ (Kanner & Bendahan, 1982; Barbour et al. 1988). In addition to the cotransport function, the glutamate transporters possess an anion channel, which is activated in the presence of the substrate (Fairman et al. 1995; Wadiche et al. 1995a; Wadiche & Kavanaugh, 1998).

EAAT1 was expressed and studied in Xenopus laevis oocytes. The data on water transport agree with the conclusions drawn from experiments on the other cotransporters cited above, but show some additional novel features. In addition to the demonstration of cotransport and osmotic transport of water, we show that the passive water permeability is different in different states of the protein, and that conductive Cl− fluxes in the protein do not lead to water transport. From the point of view of protein dynamics, the findings emphasise the importance of water-protein interactions for the conformational changes underlying glutamate transport.

METHODS

The human glutamate transporter (EAAT1) was subcloned into a vector optimized for oocyte expression (pNB1), in vitro transcribed, and expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes (50 ng RNA per oocyte) as previously described (Hediger et al. 1989). Xenopus oocytes were collected under anaesthesia from frogs that were humanely killed after the final collection. Oocytes were incubated in Kulori medium (90 mm NaCl, 1 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2 and 5 mm Hepes; pH 7.4) at 19°C for 3-7 days before experiments were performed. The experimental chamber was perfused by control solution (90 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2 and 10 mm Hepes; pH 7.4, 193 mosmol l−1), a total of 96 mm Cl−. This solution will be referred to as the high Cl− solution. Isotonic test solutions were obtained by adding 100-200 μml-glutamate (RBI, Natick, MA, USA). Experiments with low Cl− concentrations were performed with 90 mm sodium gluconate substituting for 90 mm NaCl. This low Cl− solution contained 6 mm Cl−. Hyper- and hyposmotic test solutions were produced by addition or removal of mannitol.

To test the effects of hyposmolarity on the substrate-induced current (Is), oocytes were adapted to transport in solutions where 90 mm NaCl was replaced by 50 mm NaCl plus 100 mm mannitol. Osmolarities of the test solutions were determined with an accuracy of 1 mosmol l−1. When the influence of unstirred layers and electrode artifacts were tested, the cation-selective ionophore gramicidin D (300 nm, Sigma no. G-5002, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to the bathing solutions. After about 10 min, gramicidin had decreased the input resistance of the oocyte by a factor of 15-60 and was removed from the bathing solution. Ouabain (200 μm, Sigma no. O-3125) was used in order to test contributions from the Na+-K+-ATPase.

The experimental chamber, the voltage clamp, and the optical system for the volume measurements have been described in detail elsewhere (Parent et al. 1992; Zeuthen et al. 1997; Mackenzie et al. 1998). In short, the oocytes were impaled by two microelectrodes, one providing the clamp current and the other measuring the membrane potential. The microelectrodes were filled with 0.5 or 1 m KCl. Consequently the current electrodes do not contribute to the net solute flux since the clamp current will be carried by equal and opposite fluxes of K+ and Cl−. The experimental chamber had a volume of 30 μl and solution changes were 90 % complete in 5 s, given a flow rate of 12 μl s−1. The solutions were fed into the chamber via a mechanical valve with a dead space of 5 μl.

The oocyte was observed from below via a low magnification objective and a charge coupled device camera. To achieve a high stability of the oocyte image, the upper surface of the bathing solution was determined by the flat end of a Perspex rod, which also provided an illuminated background. Images were captured directly from the camera to the random access memory of a computer. The oocyte was focused at the circumference and assumed to be spherical. The volume was recorded and calculated on-line at a rate of one point per second with an accuracy of 3 in 10 000. Only oocytes in a good condition and with well-defined and clean surfaces were used. The diameter of the oocytes was 1.34 ± 0.02 mm (n = 13). The osmotic water permeabilities (Lp) are given per true membrane surface area (Loo et al. 1996). This is about nine times the apparent area due to membrane foldings (Zampighi et al. 1995). The data were corrected for the Lp of the native oocytes that were measured for each batch. Lp values are given in units of cm s−1 (osmol l−1) −1. To obtain Lp in units of cm s−1, the values should be divided by the partial molar volume of water, Vw, of 18 cm3 mol−1. The coupling ratio of the EAAT1 is taken as the number of water molecules cotransported per unit charge by the protein. Accordingly, the coupling ratio equals F JH2O (VwIs)−1, where JH2O is the water flux, Is is the clamp current induced by application of glutamate, and F is Faraday's constant.

All numbers are given as means ±s.e.m. with n equal to the number of oocytes tested unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Cotransport of water under isotonic conditions

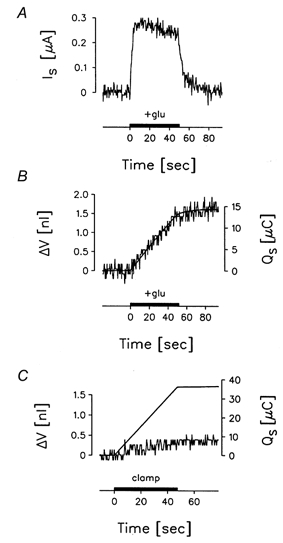

In voltage-clamped oocytes expressing EAAT1, glutamate elicited an abrupt inward current, Is (Fig. 1A), and an inward flux of water detected as a linear increase in oocyte volume (jagged line in Fig. 1B). The volume increase was a direct function of the inward current: the integrated current (Qs) described the volume change. This suggests that a fixed number of water molecules were coupled to the influx of each unit charge (smooth line in Fig. 1B). No current or volume changes were detected in uninjected oocytes (data not shown).

Figure 1. Glutamate-induced current and water flow under isotonic conditions.

A, an EAAT1-expressing oocyte was clamped continuously at -30 mV at an external Cl− concentration of 6 mm. Glutamate (200 μm) was introduced abruptly into the bath (horizontal bar). This caused an inward current, Is, that increased rapidly towards a maximum of 280 nA. B, Is was associated with a linear increase in oocyte volume (ΔV, jagged line), indicative of a constant rate of water influx of about 30 pl s−1. The volume increase and Is were abolished when l-glutamate was removed from the bath. The integrated current (Qs, smooth line in B) describes the volume changes if it is assumed that a fixed number of water molecules enter per unit charge. C, there was no initial change in oocyte volume when the inward Na+ current was mediated by a gramicidin channel. An inward current of about 750 nA was obtained (not shown) by changing the intracellular electrical potential from the resting potential (about -45 mV) to -90 mV by means of the voltage clamp (horizontal bar). The current did not give rise to any immediate change in cell volume (jagged line). The magnitude of the integrated current shows that only a small number of water molecules are transferred per unit charge. The oocyte treated with gramicidin expressed EAAT1 to the same degree as the one used in A and B, but the cotransporter was kept inactive as no substrate was present.

Evaluation of the coupling ratio (water molecules per unit charge) is complicated by the fact that glutamate not only stimulates cotransport, but also opens a Cl− channel in the EAAT1 protein (Wadiche et al. 1995a; Wadiche & Kavanaugh, 1998). Consequently, the total current through the protein is the sum of a conductive and a cotransport component. To study the effect of each of these components, we performed experiments at both high (96 mm) and low (6 mm) external Cl− concentrations; oocytes were adapted to the low Cl− solution for 16-24 h prior to experiments. The intracellular Cl− activity was estimated by adding the Ca2+-selective ionophore A23187 (2 μm) to the bathing solution (Wadiche et al. 1995a). The rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration led to activation of endogenous Cl− channels, which in turn caused the membrane potential to approach the reversal potential for Cl− (ECl). In high Cl− solutions, ECl was in the range -30 to -10 mV, as previously reported (Wadiche et al. 1995a). In oocytes adapted to the low Cl− concentrations the intracellular Cl− concentration was probably too low to contribute significantly to the clamp current. With the endogenous Cl− channels activated, these oocytes exhibited clamp currents (at -100 mV) that were ten times lower than those obtained in high Cl− concentrations (3 oocytes).

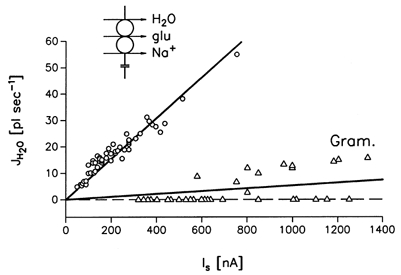

In oocytes adapted to low Cl− concentrations, the glutamate-induced increase in clamp current (Is) was mediated mainly by cotransport. These oocytes exhibited a linear relationship between Is and the water flow, JH2O, with a constant coupling ratio of 436 ± 55 water molecules transported per unit charge (n = 8) (Fig. 2). The effect was tested for Is in the range 40-800 nA obtained by clamp voltages between 0 and -110 mV; the relation between Is and clamp voltage is shown in Fig. 3A.

Figure 2. Cotransport of water as a function of glutamate-induced clamp currents (Is), low external Cl−.

The oocytes were bathed in low external Cl− concentrations (6 mm) where the current is determined by the cotransport component (see inset and text). ○, the rate of water influx, JH2O, plotted as a function of Is; experiments as in Fig. 1. Clamp voltages were in the range 0 to -110 mV (the relation between Is and clamp voltage is given in Fig. 3A). JH2O (10−3 pl s−1) was a linear function of the clamp current = 77.4 ± 1.6 Is (nA) (r = 0.97, 51 measurements in 8 oocytes). The coupling ratio was 436 ± 55 (n = 8). △, initial rates of water transport in gramicidin-treated oocytes (Gram.) as a function of clamp currents induced by sudden applications of clamp voltage; experiments as in Fig. 1C. EAAT1 was expressed but kept inactivated by the absence of glutamate. The regression line for JH2O is given by (5.8 ± 1.1) x 10−3 pl s−1 nA−1) (r = 0.55, 32 measurements in 6 oocytes).

Figure 3. Cotransport of water as a function of glutamate-induced clamp currents (Is), high external Cl−.

A, the relation between Is and clamp voltage obtained in high Cl− and low Cl− concentrations. The data obtained at low Cl− concentrations (6 mm) are the averaged data from the oocytes presented in Fig. 2. The data obtained at high Cl− concentrations (96 mm) are from an oocyte from the same batch as those used for the low Cl− experiments. Curves are drawn by eye. B, water flux (JH2O) versus glutamate-induced current (Is) for an oocyte bathed in high external Cl− concentrations (96 mm). Data are from the oocyte above, which is typical for ten oocytes. The curved line through the points is the JH2Oversus Is relation constructed from two assumptions: (1) the cotransport of water is linked to the Na+-glutamate transport and given by the relation measured in low Cl− (Fig. 2) and (2) the conductive Cl− current in the EAAT1 does not give rise to water transport. Compare, for example, the data obtained at a clamp voltage of -100 mV and at ECl, which is around -20 mV. The cotransport component of the current at -100 mV is about 100 nA larger than at ECl (Fig. 3A, ▪). Accordingly, JH2O would be predicted to be 7 pl s−1 larger at -100 mV, about 20 pl s−1, see Fig. 2. The total current, however, at -100 mV is 400 nA. The dashed line through zero is the JH2Oversus Is relation in low Cl− solutions (from Fig. 2).

In oocytes adapted to high Cl− concentration, glutamate-induced currents (Is) are the sum of a conductive Cl− current and a cotransport current. The two components were estimated by comparing the relationship between Is and clamp voltage obtained at low and high Cl− concentrations (Fig. 3A). At large negative clamp voltages the conductive current was about 60 % of the total current, in agreement with earlier reports (Wadiche et al. 1995a).

At clamp potentials equal to ECl (about -20 mV), the current generated by Cl− in the conductive pathway is negligible. Consequently, the coupling ratio obtained at -20 mV, 423 ± 25 water molecules per charge (n = 10), was similar to the one obtained at low Cl− concentrations. For clamp potentials more negative than the reversal potential, there was a conductive current in the same direction as the cotransport current, maintained by a Cl− efflux (Fig. 3A). Accordingly, the ratio between the flux of water and the total current was lower at high negative voltages than that estimated at ECl. For clamp voltages more positive than ECl, the conductive current was opposite to the cotransport current and the coupling ratio appears higher than that estimated at ECl. The relationship between JH2O and Is at high Cl− concentrations could be predicted from: (1) the relation between JH2O and Is determined in low Cl− concentrations, and (2) the assumption that the conductive Cl− current in the EAAT1 does not give rise to water transport (see legend to Fig. 3B). A representative example (out of 10 oocytes) of the relation between JH2O and Is obtained in high Cl− concentrations is shown in Fig. 3B. The oocyte had an expression similar to that used for the studies in low Cl− concentrations (Fig. 2).

The glutamate-induced clamp current, Is, exhibited run-down with time. Given a 40 s glutamate stimulation every 3 min, a 30 % reduction over the first 30 min period was not unusual. After that, the run-down decreased markedly. The phenomenon has also been reported for the rabbit Na+-glucose transporter (Mackenzie et al. 1998); its mechanism is not understood. To mitigate the problem, the measurements of curves such as those in Fig. 3A and B were performed at a randomized sequence of clamp potentials and after the initial period of run-down.

Test for specific effects of current on water transport

The observed water flow did not result from current-induced increases or decreases in substrate concentrations adjacent to the oocyte membrane. Such unstirred layer effects were estimated by inserting the cation-selective ionophore gramicidin (Finkelstein & Andersen, 1981) into the EAAT1-expressing oocyte, while the cotransporter was held inactivated by the absence of glutamate. The level of gramicidin incorporation was adjusted in order to decrease the input resistance of the oocyte by a factor of between 15 and 60. By applying a negative clamp voltage, large inward Na+-mediated currents were generated via the ionophore; replacement of external Na+ by choline ions completely abolished the gramicidin-mediated current (n = 7).

The Na+ fluxes by the gramicidin gave rise to no, or only small, initial water fluxes; an example is shown in Fig. 1C. The water fluxes obtained in six oocytes for clamp currents in the range 320-1330 nA are compiled in Fig. 2 where they are compared with the initial values of JH2O obtained from activation of the EAAT1 by glutamate. Gramicidin-mediated currents below 600 nA gave rise to no initial water fluxes, while currents in the range 600-1330 nA did evoke initial water fluxes, up to an average of 8 pl s−1 at the largest currents. Regression analysis shows that the gramicidin-generated currents were, on average, thirteen times less efficient in generating water fluxes than cotransport currents (see Fig. 2).

In order to estimate the significance of the current generated by the Na+-K+-ATPase, ouabain (200 μm) was added during the gramicidin-induced clamp current. Ouabain increased the clamp current by 13.6 ± 5.5 nA (n = 5). Pump currents of this magnitude account for less than 3 % of the currents used in this study.

Osmotic transport

In addition to its capacity to act as a molecular water pump, EAAT1 also sustains a passive water transport when exposed to transmembrane osmotic gradients. The passive water permeability (Lp) of EAAT1-expressing oocytes was measured under different conditions: with and without glutamate present (200 μm), and at high and low Cl− concentrations. In general the external clamp was not applied in order to minimize the cotransport component, yet the effect of external clamping was tested in specific cases. Initially, the oocyte was adapted to the experimental condition to be tested. When the oocyte had achieved a constant volume (ΔV/Δt less than 1 pl s−1), mannitol was added to (or removed from) the bathing solution. The induced volume changes (ΔV/Δt =JH2O) were linear, and osmotic gradients (Δπ) as large as 20 mosmol lasting as long as 1 min were employed. The Lp values were evaluated as ΔJH2O/Δπ (Fig. 4). The values given in the following have been corrected for the Lp of the native oocyte (top trace in Fig. 4A). This was (3.3 ± 0.5) x 10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1(n = 5), in agreement with previous studies (Zhang & Verkman, 1991; Loo et al. 1996; Meinild et al. 1998). This Lp was about 20 % of the permeability of the EAAT1-expressing oocytes, and was independent of Cl− and glutamate concentrations.

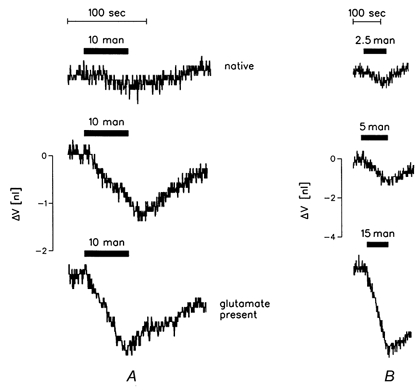

Figure 4. Passive water permeability of EAAT1-expressing oocytes.

A, effects of the presence of glutamate. Lp was determined from the linear volume change elicited by the addition of mannitol to the bathing solution. Upper trace, native oocyte. Middle trace, EAAT1-expressing oocyte. Lower trace, the same oocyte as above, but with glutamate (200 μm) present throughout, i.e. in both the bathing and test solutions. The oocyte was unclamped in order to minimize the cotransport component. Accordingly, a well-defined baseline was achieved, indicative of little or no change in oocyte volume (see text). It is seen that the presence of glutamate increases Lp. The native and EAAT1-expressing oocytes were from the same batch. B, effects of magnitude of osmotic gradient. Volume changes are in response to hyperosmolar challenges of 2.5, 5 or 15 mosmol l−1. The recordings are from the same oocyte and are plotted in Fig.6A (○). It appears that the same Lp was determined irrespective of the magnitude of the osmotic challenge. Glutamate was present in bathing and test solutions throughout, no external clamp applied (see text).

High Cl− concentrations (96 mm) and glutamate absent

Lp averaged (11.3 ± 2.0) x 10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1. These data were from eight oocytes, the expression level of which were characterized by glutamate-induced currents (Is) in the range 350-800 nA measured at clamp potentials around ECl. In general, a larger expression level was associated with a larger Lp. Normalized to an oocyte with an Is of 500 nA, Lp was calculated as (9.0 ± 1.5) x 10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1. The oocytes tested had membrane potentials between -25 and -40 mV. The membrane potential did not change during the osmotic challenge. Conversely, we found no differences in Lp values of oocytes whether unclamped or clamped to a membrane potential in range -25 to -40 mV (n = 4).

High Cl− concentrations (96 mm) and glutamate present

The presence of glutamate (200 μm) increased Lp by a factor of 1.4 ± 0.1 (n = 6) compared with the glutamate-free case presented above (Fig. 4A). The comparison is performed in paired experiments so the difference is highly significant (P < 0.01). Glutamate concentrations of 100 and 300 μm were also tested; K0.5 for the effect on Lp was below 100 μm. Volume changes obtained by osmotic gradients of various size are shown in Fig. 4B and plotted in Fig. 6A (○).

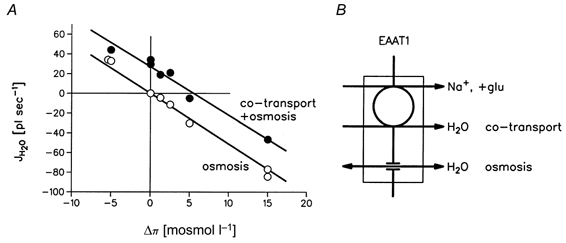

Figure 6. Independence of the cotransport component and the osmotic component of water transport in EAAT1.

A, summary of the data obtained in Figs 4B and 5, where the cotransport and the passive components of water transport were studied as a function of the transmembrane osmotic difference. The (minor) fraction of the water flux going through the native oocyte membrane has been subtracted. The upper curve (•) represents the water fluxes (JH2O=ΔV/Δt) obtained by the simultaneous activation of the cotransport and the osmotic water transports by sudden application of glutamate and mannitol (data from Fig. 5). JH2O as a function of Δπ is given by the regression line JH2O= 26.7 pl s−1 - 4.8 pl s−1 (mosmol l−1)−1 (r = -0.99). The lower curve (○) represents JH2O values obtained from osmotic challenges only; data from Fig. 4B. JH2O is given by the line -5.5 pl s−1 (mosmol l−1)−1 (r = -0.997). The two sets of data are from the same oocyte. The slopes of the two lines were similar and represent the Lp of EAAT1 in the presence of glutamate. The constant vertical displacement represents the cotransport component of water transport. Similar sets of data were obtained in 7 other oocytes (Table 1). B, a model of the protein in which the cotransport and the osmotic water transport work in parallel and independently.

The application of glutamate to the EAAT1-expressing oocyte under conditions of no clamp depolarized oocytes to +24 ± 5 mV (n = 16). Even at this positive potential there is probably a slow rate of inwardly directed cotransport. The turnover rate can be estimated to be up to 20 % of the maximal rate (Wadiche et al. 1995a); Mitrovic et al. 1998). After about 3-5 min, however, the oocyte volume increase tended to stabilize at a value of around 4 pl s−1. Lp was recorded during this phase. It should be emphasized that activity of the cotransporter does not prevent the measurement of Lp. Lp was derived from the change in water flow induced by a change in bath osmolarity; gradients of up to ±20 mosmol l−1 were employed. Gradients of this magnitude do not affect the rate of cotransport. This was estimated from the sensitivity of Is to osmotic challenges. Under clamped conditions it took gradients of 100 mosmol l−1 mannitol to reduce Is by 6.9 ± 0.8 %(n = 6). Is increased by a similar percentage if the external osmolarity was decreased by 100 mosmol l−1.

Low Cl− concentrations (6 mm) and glutamate absent

The Lp recorded at low external Cl− appeared to be lower than that recorded in the presence of Cl−. Normalized to an oocyte with an Is of 500 nA, Lp was calculated as (7.5 ± 0.7) x 10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1 (data from Table 1). It was not possible, however, to apply the high and low Cl− conditions on the same oocyte in a way that would allow the oocyte to be its own control; oocytes adapted to low Cl− were rather fragile. A firm conclusion on the effects of Cl− requires further experiments.

Table 1.

Cotransport of water (JH2O) and osmotic water permeability (Lp) of EAAT1-expressing oocytes

| Oocyte no. | JH2O initial (pl s−1) | Lp (−clamp, −glu) (10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1) | Lp (−clamp, +glu) (10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1) | Lp (+clamp, +glu) (10−6 cm s−1 (osmol l−1)−1) | Clamp voltage (mV) | Is (nA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Cl− | ||||||

| 1 | 64.7 ± 1.8(7) | 19.5 ± 0.2(6) | 28.9 ± 0.6(7) | 24.9 ± 1.0(7) | −30 | 795 |

| 2 | 26.0 ± 0.9(13) | n.d. | 9.9 ± 0.4(5) | 12.1 ± 0.3(13) | −30 | 575 |

| 3 | 30.8 ± 0.6(9) | 7.3 ± 0.1(9) | 11.5 ± 0.1(8) | 11.9 ± 0.2(9) | −30 | 875 |

| 4 | 26.7 ± 1.0(7) | 7.3 ± 0.1(9) | 11.5 ± 0.1(8) | 10.1 ± 0.3(7) | −30 | 340 |

| 5 | 22.0 ± 1.5 (7) | 9.8 ± 0.2(10) | 13.4 ± 0.3(8) | 14.7 ± 0.3(7) | −20 | 535 |

| Low Cl− | ||||||

| 6 | 22.1 ± 2.1(8) | 3.8 ± 0.1(11) | 5.7 ± 0.1(11) | n.d. | −70 | 330 |

| 7 | 18.5 ± 1.9(7) | 2.5 ± 0.3(5) | 5.0 ± 0.4(11) | 4.4 ± 0.4(7) | −50 | 440 |

| 8 | 19.5 ± 2.8(3) | 5.7 ± 0.04(23) | 6.9 ± 0.02(17) | n.d. | −50 | 470 |

| 9 | 30.0 ± 1.1(8) | 6.7 ± 0.2(8) | 12.4 ± 0.3(5) | 14.9 ± 0.4(8) | −50 | 750 |

The Lp was determined under three conditions: Lp (—clamp, —glu) gives the value obtained from under conditions of no external clamp and no glutamate present (Fig. 4A, middle external clamp applied (Fig. 4A, lower trace); Lp (+clamp, +glu) gives the value obtained applications of glutamate and mannitol under voltage clamp conditions (Fig. 5). Oocytes 4 represent recordings from the same oocyte at different times: early in the experiment the (Is) were high; after about half an hour of glutamate stimulation under clamped conditions Is had stabilized at a lower level.

Low Cl− concentrations (6 mm) and glutamate present

The presence of glutamate increased the Lp by a factor of 1.6 ± 0.2 (n = 7) compared with the values above (Table 1). The comparison was performed in paired experiments so the differences are highly significant (P < 0.01).

Separation of cotransport and osmotic water transport

In order to test whether the cotransport and osmotic components could be treated as independent modalities, we performed experiments in which cotransport and osmotic transport were activated simultaneously. In the control situation, oocytes were bathed in a glutamate-free solution and clamped to a negative potential. The cotransport component was determined by adding glutamate (200 μm) under isotonic conditions (Fig. 5, first trace), in analogy to the experiments shown in Fig. 1A and B. In the subsequent experiments the osmolarity of the bathing solution was changed simultaneously with the application of glutamate. Results from nine oocytes serving as their own controls are listed in Table 1.

Figure 5. Uphill transport of water by EAAT1.

The EAAT1-expressing oocyte was initially bathed in glutamate-free control solutions under clamped conditions (-30 mV). At the time indicated by the horizontal bar, glutamate (200 μm) was added to the bathing solution (+glu). This induced an immediate swelling of the oocyte; this part of the experiment is analogous to that illustrated in Fig. 1A and B. In the following three recordings the stimulation by glutamate was combined with a hyperosmotic challenge of 2.5, 5 and 15 mosmol l−1 of mannitol, respectively (+man). The glutamate-induced current Is (not shown) was about 300 nA in all four experiments (see text). It appears that the inwardly directed cotransport of water can proceed despite adverse osmotic gradients. The rates of water transport are plotted in Fig. 6A as a function of the osmotic challenge.

The oocyte would swell in the face of small hyperosmotic gradients and shrink at the larger gradients; values in the range ±20 mosmol l−1 were tested. At an osmotic gradient of +5 mosmol l−1 the osmotic efflux and the cotransported influx of water would be about equal, and the oocyte volume would remain stable (Fig. 5). The rate of swelling plotted as a function of the osmotic gradient defines a line (Fig. 6A, •), the slope of which determines an Lp (Table 1, Lp+clamp, +glu). This Lp was not significantly different from the Lp determined in the presence of glutamate without the external clamp turned on (Table 1, Lp -clamp, +glu). This shows that the osmotic pathway of EAAT1 in the presence of glutamate can be described by a single Lp value that is independent of the osmotic gradient and of the rate of cotransport.

The cotransport component of the water transport was also independent of the magnitude and direction of the osmotic challenge. The data in Fig. 5 are explained most simply by a model in which a constant component of water cotransport is superimposed upon the osmotic component of the water transport (Fig. 6). As described above, the cotransport current was independent of osmotic gradients in the range employed; it took 100 mosmol l−1 to produce significant changes in Is.

Temperature dependence

The glutamate-induced cotransport current and associated water flow were studied as a function of temperature (range 13-24°C). The Arrhenius activation energy, Ea, for Is was 25 ± 4 kcal mol−1 (105 ± 17 kJ mol−1; n = 6). In two of the oocytes, Ea for JH2O was found to be the same as that for Is. In four of the oocytes the low temperature reduced JH2O below detection level, about 2 pl s−1, which means that Ea for JH2O was larger or equal to that of Is. The high values of Ea suggest that the charge translocation and the associated water transport take place with substantial conformational changes of the protein, and reflect the comparatively low turnover number (about 15 s−1) for these transporters (Wadiche et al. 1995b). Ea for the passive osmotic water permeability of the EAAT1-expressing oocytes was not significantly different from that of the uninjected oocytes, which is about 10 kcal mol−1 (42 kJ mol−1; Zhang & Verkman, 1991). This makes a quantitative evaluation difficult, but suggests that Ea for the osmotic water transport is low, indicative of minor conformational changes associated with this type of transport. This is in analogy with findings for other symporters (Meinild et al. 1998; Loo et al. 1999a,b).

DISCUSSION

We show that water can be transported across cell membranes by the human glutamate transporter EAAT1. The transport proceeds by two mechanisms, cotransport and osmosis, which operate in parallel and independently (Fig. 6B).

EAAT1 as a molecular water pump

Cotransport of one unit charge led to the cotransport of about 436 water molecules. This was demonstrated directly at low Cl− concentrations where the clamp current could be identified with the cotransport current (Fig. 2). The coupling ratio was independent of the presence of Cl−: a similar coupling ratio was observed in solutions with high Cl− concentrations at clamp potentials equal to ECl, where the conductive Cl− fluxes through the protein were minimized (Fig. 3B). In addition, the cotransport of water was independent of clamp potentials, currents via the Cl− channel of the protein, and external osmolarity. Most importantly, cotransport of water could proceed uphill, against the water chemical potential difference (Fig. 5 and 6A).

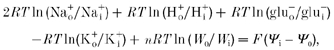

The cotransport of water appears to be energized by coupling to the electrochemical driving force by a mechanism within the protein, which requires major conformational changes. If we assume a stoichiometry with cotransport of 2 Na+, 1 H+, 1 glutamate, 436 water molecules, and countertransport of 1 K+ (for references, see Introduction), the Gibbs equation gives:

|

(1) |

where ‘o’ defines the outside and ‘i’ the inside compartment, W is the water concentration (proportional to exp(-osmolarity/nw)), nw is the molarity of water (= 55 m), n is the coupling ratio (= 436), and ψ is the electrical potential (Zeuthen, 1996; Meinild et al. 1998; Rudnick, 1998). With a membrane potential of -50 mV, tenfold concentration differences for Na+, glutamate (inwardly directed) and K+ (outwardly directed) and no concentration difference for H+, it can be calculated that the inward water flux would proceed in spite of adverse osmotic gradients of up to 1500 mosmol l−1. The Na+ and the electrical gradients alone would account for 900 mosmol l−1. With the assumption of cotransport of 3 Na+, the numbers would be 2100 and 1800 mosmol l−1. These estimates comply with the finding that the cotransport was insensitive to osmotic challenges of the order of 20 mosmol l−1 (Fig. 5A). The dependence of the cotransport on osmotic gradients only became apparent at gradients as large as ±100 mosmol l−1.

The properties of EAAT1 as a molecular water pump were compatible with those observed for other electrogenic Na+-coupled cotransporters listed in the introduction. In the EAAT1, however, the Lp was large relative to its capacity for water cotransport compared with the Na+-glucose cotransporter SGLT1. In EAAT1 it took an external hyperosmolarity of 5 mosmol l−1 to produce an osmotic efflux that matched the cotransported influx (Fig. 6A). In SGLT1 it took an external hyperosmolarity of 15 mosmol l−1 to match osmosis with cotransport (Meinild et al. 1998). In other words, the capacity for uphill water transport in EAAT1 is three times smaller than in SGLT1.

Estimation of unstirred layer effects and electrode artifacts

Large currents maintained by gramicidin did not give rise to any significant initial water flows (Fig. 2). This suggests that the current flow as such in the EAAT1 does not give rise to initial water flows.

In order to compare the effects of gramicidin-generated currents and cotransport currents, the stoichiometry of the EAAT1 has to be considered. With 3 Na+ and 1 glutamate (negatively charged) two osmotically active particles are transferred for each unit charge; with 2 Na+ and 1 glutamate, three osmotically active particles are transferred for each unit charge; the transport of K+ and H+ may cancel out (see below). In the worst case, then, the volume effects observed in the gramicidin experiments should be multiplied by a factor of three in order to mimic the EAAT1 experiments. As seen from Fig. 2, the JH2O values induced by the EAAT1 are more than one order of magnitude larger than the effects observed with gramicidin. We suggest that currents as such cannot explain the initial values of JH2O.

Three minor effects may be relevant for the above comparison. (i) The estimated number of osmotic particles transported by the EAAT1 is probably an overestimate. EAAT1 exports 1 K+ and imports 1 H+, but due to binding, the H+ may not exert any osmotic effects in the oocyte. (ii) The Na+ ions transported by the gramicidin will become surrounded by Cl− or other osmotically active counter ions at the inside of the membrane. The Na+ ions carried by the EAAT1 already have glutamate as counter ions, consequently the excess density of other counter ions will be smaller. From (i) and (ii) it appears that in the worst case, the volume effects observed in the gramicidin experiments should be multiplied by a factor of only two in order to mimic the EAAT1 experiments. (iii) If glutamate diffuses twice as slowly as Na+, the volume effects observed in the gramicidin experiments should be multiplied by a factor of four in order to mimic the EAAT1 experiments. A recent estimate, however, indicates that glucose (which is larger than glutamate) makes unstirred layers only 10-20 % larger than those of Na+ (Zeuthen et al. 2001).

Unstirred layer effects have been suggested to arise at least in part from the folded nature of the oocyte membrane (Diamond, 1996). The plasma membrane of the oocyte contains microvilli, which are about 10 μm long and 1 μm wide (Soreq & Seidman, 1992). Such dimensions, however, cannot amplify unstirred layer effects significantly (for a review, see House, 1974), in agreement with our findings of no unstirred layer effects.

The relation between water transport and current observed in solutions with high Cl− concentrations could be explained quantitatively by a combination of the cotransport component and the current via the Cl− channel part of the protein (see above and legend to Fig. 3). This suggests that the electrogenic Cl− current through the EAAT1 does not give rise to water transport.

In order to minimize net solute flow from the microelectrodes, KCl was used as filling solution. This ensures that currents are carried by equal and opposite fluxes of K+ and Cl−. The lack of initial changes in oocyte volume with large gramicidin currents supports this notion.

The osmotic water permeability of EAAT1

Glutamate increased the Lp of the EAAT1 irrespective of the rate of cotransport. We determined the Lp in the presence of glutamate under two transport conditions. In one condition the oocyte was unclamped and allowed to reach a positive steady state potential of about +25 mV (Lp -clamp, +glu; Table 1). Under these conditions the rate of cotransport is slow, about 20 % of the maximal rate (Wadiche et al. 1995; Mitrovic et al. 1998). In the other situation Lp was determined under conditions of maximal rate of cotransport obtained at negative clamp potentials (Lp+clamp, +glu). The two Lp values were the same but about 50 % larger than the Lp determined in the absence of glutamate.

The osmotic water permeability is the weighed average of the Lp values of the conformational states occupied under the given circumstances. Our finding suggests that the presence of glutamate shifts the conformational equilibrium towards more water-permeable states. Full activation of the cotransporter does not change the Lp, but it adds a constant component of water transport that is independent of the osmotic gradient (Fig. 6A). Further experiments would be required to obtain a precise correlation between the Lp and the distribution of conformational states of the protein, and to obtain the Lp values of individual conformational states.

For equal values of substrate-induced currents, EAAT1-expressing oocytes had a 6-fold higher Lp than oocytes expressing the human Na+-glucose cotransporter (cf. Meinild et al. 1998). This could reflect a higher expression level for the EAAT1 transporter. The EAAT1 has a turnover rate, 15 s−1 (Wadiche et al. 1995b), lower than that of the Na+-glucose transporter, which is about 60 s−1 (Parent et al. 1992). Consequently, it would take a higher expression level of EAAT1 to achieve the same current. Substrate-induced changes in Lp values were not observed with the Na+-glucose transporters (Loo et al. 1999b). Possibly, the expression levels in these studies are too low to detect analogous changes in the Lp.

Molecular mechanisms

The molecular mechanisms underlying water transport in the EAAT1 and other symporters are as yet unknown. Two models based on mobile barriers or loops have been suggested (Zeuthen, 1996). The models are based on the fact that a well-defined number of water molecules are bound or released by enzymes during conformational changes. This applies both to aqueous enzymes (Colombo et al. 1992; Rand et al. 1993; Qian et al. 1995) as well as to membrane-bound enzymes (Zimmerberg & Parsegian, 1986; Kornblatt & Hoa, 1990); values in the range of 10-1200 water molecules have been reported. The models suggest that binding of glutamate at the outside is associated with the opening and filling of an aqueous pathway in the protein. This agrees with our finding of a glutamate-induced increase in Lp and with studies of the accessibility of specific amino acid residues in neurotransmitter transporters, which indicate the existence of a water-filled pore in the proteins (Golovanevsky & Kanner, 1999; Slotboom et al. 1999). When glutamate is subsequently released to the other side of the membrane, the process is reversed: the cavity closes and the water is released. To accommodate 400 water molecules as bulk water, the cavity would have to be about 104Å3 large. If, in analogy to haemoglobin (Colombo et al. 1992), the water was held as loosely bound surface water, it would need a surface of about 4000 Å2, roughly equivalent to the van der Waal surface of three α-helices, 80 Å long.

Physiological relevance

Due to the wide distribution of Na+-glutamate transporters, the ability to transport water may have several physiological consequences in relation to both epithelial absorption and cellular water homeostasis. The EAAT1 is primarily located in glial cells (Rothstein et al. 1994; Lehre et al. 1995) where the water channel AQP4 has also been found (Jung et al. 1994; Frigeri et al. 1995; Nielsen et al. 1997). Glial cells have been proposed to be osmometers of the central nervous system (Jung et al. 1994; King & Agre, 1996). Osmotic imbalances of these cells could occur from uncompensated uptake of solutes, such as glutamate, which would lead to disturbances of the water homeostasis of the brain. This perturbation would be alleviated, at least in part, by cotransport of water in the EAAT1. A precise evaluation requires knowledge of the osmolarity of the transported solution, and therefore of the stoichiometry of the EAAT1 (see introduction). If 2 Na+ and 1 H+ were cotransported per glutamate, while 1 K+ was countertransported, 141 water molecules would enter per particle, 212 if 3 Na+ ions were translocated. These values should be compared with human plasma (320 mosmol l−1), which contains about 170 water molecules per osmotically active particle. In conclusion, water transport by the EAAT1 renders the glutamate re-uptake nearly isotonic and hence non-disturbing to the osmosensation of the glial cells.

Acknowledgments

The clone for EAAT1 was a kind gift from Dr Susan Amara. We are grateful for the technical assistance of S. Christoffersen, B. Lynderup and T. Soland, and for the valuable discussions with Morten Grunnet and Stine Meinild. This study was supported by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Danish Research Council.

References

- Arriza JL, Eliasof S, Kavanaugh MP, Amara SG. Excitatory amino acid transporter 5, a retinal glutamate transporter coupled to a chloride conductance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:4155–4160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arriza JL, Fairman WA, Wadiche JI, Murdoch GH, Kavanaugh MP, Amara SG. Functional comparisons of three glutamate transporter subtypes cloned from human motor cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:5559–5569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05559.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Brew H, Attwell D. Electrogenic glutamate uptake in glial cells is activated by intracellular potassium. Nature. 1988;335:433–435. doi: 10.1038/335433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew H, Attwell D. Electrogenic glutamate uptake is a major current carrier in the membrane of axolotl retinal glial cells. Nature. 1987;327:707–709. doi: 10.1038/327707a0. (published erratum appears in Nature (1987) 328, 742) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo MF, Rau DC, Parsegian VA. Protein solvation in allosteric regulation: A water effect on hemoglobin. Science. 1992;256:655–659. doi: 10.1126/science.1585178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JM. Wet transport proteins. Nature. 1996;384:611–612. doi: 10.1038/384611a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erecinska M, Troeger MB, Wilson DF, Silver IA. The role of glial cells in regulation of neurotransmitter amino acids in the external environment. II. Mechanism of aspartate transport. Brain Research. 1986;369:203–214. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairman WA, Vandenberg RJ, Arriza JL, Kavanaugh MP, Amara SG. An excitatory amino-acid transporter with properties of a ligand-gated chloride channel. Nature. 1995;375:599–603. doi: 10.1038/375599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein A, Andersen OS. The gramicidin A channel: a review of its permeability characteristics with special reference to the single-file aspect of transport. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1981;59:155–171. doi: 10.1007/BF01875422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigeri A, Gropper MA, Turck CW, Verkman AS. Immunolocalization of the mercurial-insensitive water channel and glycerol intrinsic protein in epithelial cell plasma membranes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:4328–4331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovanevsky V, Kanner BI. The reactivity of the γ-aminobutyric acid transporter GAT-1 toward sulfhydryl reagents is conformationally sensitive. Identification of a major target residue. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:23020–23026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger MA, Turk E, Wright EM. Homology of the human intestinal Na+/glucose and Escherichia coli Na+/proline cotransporters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1989;86:5748–5752. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House CR. Water Transport in Cells and Tissues. London: Edward Arnold Publishers Ltd; 1974. p. 562. [Google Scholar]

- Jung JS, Bhat RV, Preston GM, Guggino WB, Baraban JM, Agre P. Molecular characterization of an aquaporin cDNA from brain: Candidate osmoreceptor and regulator of water balance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:13052–13056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.13052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner BI, Bendahan A. Binding order of substrates to the sodium and potassium ion coupled L-glutamic acid transporter from rat brain. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6327–6330. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LS, Agre P. Pathophysiology of the aquaporin water channel. Annual Review of Physiology. 1996;58:619–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.003155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblatt JA, Hoa GHB. A non-traditional role for water in the cytochrome c oxidase reaction. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9370–9376. doi: 10.1021/bi00492a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehre KP, Levy LM, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J, Danbolt NC. Differential expression of two glial glutamate transporters in the rat brain: quantitative and immunocytochemical observations. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:1835–1853. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01835.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loike J, Hickman S, Kuang K, Xu M, Cao L, Vera JC, Silverstein SC, Fischbarg J. Sodium-glucose cotransporters display sodium- and phlorizin-dependent water permeability. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;271:C1774–1779. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo DDF, Hirayama BA, Meinild A-K, Chandy G, Zeuthen T, Wright EM. Passive water and ion transport by cotransporters. Journal of Physiology. 1999a;518:195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0195r.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo DDF, Wright EM, Meinild A-K, Klaerke DA, Zeuthen T. Commentary on ‘Epithelial fluid transport - a century of investigation’. News in Physiological Sciences. 1999b;14:98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo DD, Zeuthen T, Chandy G, Wright EM. Cotransport of water by the Na+/glucose cotransporter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:13367–13370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie B, Loo DD, Wright EM. Relationships between Na+/glucose cotransporter (SGLT1) currents and fluxes. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1998;162:101–106. doi: 10.1007/s002329900347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinild A-K, Klaerke DA, Loo DDF, Wright EM, Zeuthen T. The human Na+-glucose cotransporter is a molecular water pump. Journal of Physiology. 1998;508:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.015br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinild AK, Loo DD, Pajor AM, Zeuthen T, Wright EM. Water transport by the renal Na+-dicarboxylate cotransporter. American Journal of Physiology Renal Physiology. 2000;278:F777–783. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovic AD, Amara SG, Johnston GA, Vandenberg RJ. Identification of functional domains of the human glutamate transporters EAAT1 and EAAT2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:14698–14706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PJ, Dean GE, Aronson PS, Rudnick G. Hydrogen ion cotransport by the renal brush border glutamate transporter. Biochemistry. 1983;22:5459–5463. doi: 10.1021/bi00292a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen S, Nagelhus EA, Amiry-Moghaddam M, Bourque C, Agre P, Ottersen OP. Specialized membrane domains for water transport in glial cells: high-resolution immunogold cytochemistry of aquaporin-4 in rat brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:171–180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent L, Supplisson S, Loo DD, Wright EM. Electrogenic properties of the cloned Na+/glucose cotransporter: I. Voltage-clamp studies. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1992;125:49–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00235797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian M, Haser R, Payan F. Carbohydrate binding sites in a pancreatic α-amylase-substrate complex, derived from X-ray structure analysis at 2. 1 Å resolution. Protein Science. 1995;4:747–755. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand RP, Fuller NL, Butko P, Francis G, Nicholls P. Measured change in protein solvation with substrate binding and turnover. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5925–5929. doi: 10.1021/bi00074a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Martin L, Levey AI, Dykes-Hoberg M, Jin L, Wu D, Nash N, Kuncl RW. Localization of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters. Neuron. 1994;13:713–725. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnick G. Ion-coupled neurotransmitter transport: thermodynamic vs. kinetic determinations of stoichiometry. Methods in Enzymology. 1998;296:233–247. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)96018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotboom DJ, Sobczak I, Konings WN, Lolkema JS. A conserved serine-rich stretch in the glutamate transporter family forms a substrate-sensitive re-entrant loop. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:14282–14287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soreq H, Seidman S. Xenopus oocyte microinjection: from gene to protein. Methods in Enzymology. 1992;207:225–265. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallcup WB, Bulloch K, Baetge EE. Coupled transport of glutamate and sodium in a cerebellar nerve cell line. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1979;32:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb04509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadiche JI, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Ion fluxes associated with excitatory amino acid transport. Neuron. 1995a;15:721–728. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadiche JI, Arriza JL, Amara SG, Kavanaugh MP. Kinetics of a human glutamate transporter. Neuron. 1995b;14:1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadiche JI, Kavanaugh MP. Macroscopic and microscopic properties of a cloned glutamate transporter/chloride channel. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:7650–7661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-19-07650.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampighi GA, Kreman M, Boorer KJ, Loo DDF, Bezanilla F, Chandy G, Hall JE, Wright EM. A method for determining the unitary functional capacity of cloned channels and transporters expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1995;148:65–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00234157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerangue N, Kavanaugh MP. Flux coupling in a neuronal glutamate transporter. Nature. 1996;383:634–637. doi: 10.1038/383634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T. Secondary active transport of water across ventricular cell membrane of choriod plexus of Necturus maculosus. Journal of Physiology. 1991;444:153–173. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T. Cotransport of K+, Cl− and H2O by the membrane proteins from choroid plexus epithelium of Necturus maculosus. Journal of Physiology. 1994;478:203–219. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T. Molecular Mechanisms of Water Transport. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1996. p. 170. [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T, Hamann S, La Cour M. Cotransport of H+, lactate and H2O by membrane proteins in retinal pigment epithelium of bullfrog. Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:3–17. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T, Meinild AK, Klaerke DA, Loo DD, Wright EM, Belhage B, Litman T. Water transport by the Na+/glucose cotransporter under isotonic conditions. Biology of the Cell. 1997;89:307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(97)83383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen T, Meinild A-K, Loo DDF, Wright EM, Klaerke DA. Isotonic transport by the Na+-glucose cotransporter from human and rabbit. Journal of Physiology. 2001 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0631h.x. in the Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Verkman AS. Water and urea permeability properties of Xenopus oocytes: expression of mRNA from toad urinary bladder. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:C26–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.1.C26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerberg J, Parsegian VA. Polymer inaccessible volume changes during opening and closing of a voltage-dependent ionic channel. Nature. 1986;323:36–39. doi: 10.1038/323036a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]