Abstract

Electrophysiological and microinjection methods were used to examine the role of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) in regulating transmitter release at the squid giant synapse.

Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) evoked by presynaptic action potentials were not affected by presynaptic injection of an exogenous active catalytic subunit of mammalian PKA.

In contrast, presynaptic injection of PKI-amide, a peptide that inhibits PKA with high potency and specificity, led to a reversible inhibition of EPSPs.

Injection of several other peptides that serve as substrates for PKA also reversibly inhibited neurotransmitter release. The ability of these peptides to inhibit release was correlated with their ability to serve as PKA substrates, suggesting that these peptides act by competing with endogenous substrates for phosphorylation by active endogenous PKA.

We suggest that the phosphorylation of PKA substrates is maintained at a relatively high state under basal conditions and that this tonic activity of PKA is to a large degree required for evoked neurotransmitter release at the squid giant presynaptic terminal.

Transmission at many synapses is regulated by activation of protein kinases including cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA). While PKA can affect synaptic activity by altering postsynaptic properties (Greengard et al. 1991), it also regulates presynaptic function. Activation of PKA enhances the amount of neurotransmitter released from many presynaptic terminals (e.g. Chavez-Noriega & Stevens, 1994; Weisskopf et al. 1994; Huang et al. 1994; Salin et al. 1996; Chen & Regehr, 1997; Tzounopoulos et al. 1998). Targets of PKA include presynaptic ion channels (e.g. Siegelbaum et al. 1982; Alkon et al. 1983; Madison & Nicoll, 1986; Gross et al. 1990; Li et al. 1992), although PKA may also enhance release downstream of Ca2+ influx (Capogna et al. 1995; Trudeau et al. 1996; Chavis et al. 1998) and directly up-regulate the presynaptic secretory machinery (Trudeau et al. 1998).

Here we used the squid giant synapse to investigate the role of PKA in transmitter release. Due to the large size of its presynaptic terminal, a variety of reagents can be microinjected directly while assessing the synaptic effects of these molecular perturbations (Augustine et al. 1999). We found that blockade of PKA activity, by microinjecting a specific inhibitor or several exogenous substrates of this enzyme, inhibited evoked neurotransmitter release. In contrast, injection of the active, catalytic subunit of PKA had no effect. These results indicate that PKA is tonically active in the squid presynaptic terminal and is required for synaptic transmission in response to presynaptic action potentials.

METHODS

Squid (Loligo pealei) were killed by decapitation and stellate ganglia were isolated as described previously (Hilfiker et al. 1998). Ganglia were placed in a recording chamber, where they were continuously superfused with saline (466 mm NaCl, 54 mm MgCl2, 11 mm CaCl2, 10 mm KCl, 3 mm NaHCO3, 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.2) oxygenated with 99.5 % O2-0.5 % CO2 mixture. The temperature was kept constant at 13-15°C with an ice-water bath that cooled the incoming saline line, was monitored throughout all experiments, and varied less than 1°C during an experiment lasting several hours.

Electrical measurements and microinjections were performed as described previously (Hilfiker et al. 1998). Briefly, a microelectrode containing 3 m KCl was placed into the presynaptic axon to deliver depolarizing current pulses (0.4-1 μA) to elicit action potentials, and a second electrode containing 3 m KCl was inserted into the postsynaptic cell to record the EPSP. The initial slope of the EPSP (before the postsynaptic action potential occurred) was used as a measure of neurotransmitter release (Hilfiker et al. 1998). A third electrode was inserted directly into the presynaptic terminal of the giant synapse. This microelectrode was used both for microinjection of reagents and for recording of the presynaptic action potential. It contained the indicated concentrations of synthetic peptides in a peptide injection buffer (100 mm KCl, 250 mm potassium isothionate, 100 mm taurine, 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.4), or the indicated concentrations of the catalytic subunit of PKA in a protein injection buffer (400 mm KCl, 50 mm Hepes, pH 7.4). In both cases, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (0.1 mm, molecular mass 3 or 10 kDa, respectively; Molecular Probes) was included to monitor the volume injected. Electrical signals were filtered at 3-10 kHz, digitized at 33 kHz and analysed using software written in AxoBASIC (Axon Instruments).

Peptides were synthesized by The Rockefeller University Protein/DNA Technology Center (New York, NY, USA) and purified (> 95 % pure) by reversed-phase HPLC; their identities were confirmed by mass spectroscopy. The catalytic subunit of PKA was a generous gift of A. Horiuchi and A. C. Nairn (The Rockefeller University).

RESULTS

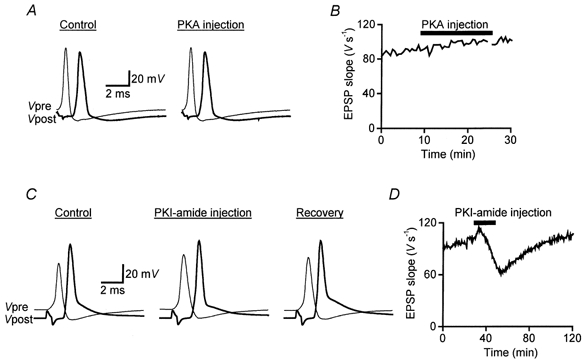

Exogenous PKA does not affect synaptic transmission

We began by determining whether microinjection of exogenous PKA into the giant presynaptic terminal could affect neurotransmitter release. For this purpose, the injection pipette contained the catalytic subunit of PKA (66 μm) and this enzyme was highly active in injection buffer (data not shown). However, even prolonged injection of PKA, up to an estimated presynaptic concentration of 6 μm, had no effect on neurotransmitter release evoked by presynaptic action potentials (Fig. 1A). The lack of effect of injected PKA was clearest when the slope of the postsynaptic response (EPSP) was plotted over time during PKA injection (Fig. 1B). On average, the injected PKA had an insignificant effect on EPSP slope (103 ± 2 % of preinjection values, mean ±s.e.m., n= 3). These data suggest either that PKA does not regulate neurotransmitter release at this synapse or that the activity of endogeneous PKA is high and not rate limiting under our conditions.

Figure 1. Effect of PKA and PKI-amide on transmitter release.

A, examples of presynaptic (Vpre) and postsynaptic (Vpost) responses recorded before (Control, 8.5 min after the start of recording) and during (19 min) injection of PKA. B, injection of the catalytic subunit of PKA had no effect on the slope of postsynaptic responses (EPSP slope) evoked at 30 s intervals. PKA was present at 66 μm in the injection electrode. C, examples of presynaptic (Vpre) and postsynaptic (Vpost) responses recorded before (Control, 29 min after the start of recording), during (53.5 min) and after (Recovery, 100 min) injection of a PKA inhibitor, PKI-amide. D, injection of PKI-amide led to a reversible inhibition of neurotransmitter release, measured as the slope of EPSPs. PKI-amide was present at 20 mm in the injection electrode.

Dual effects of PKI-amide on synaptic transmission

To distinguish between these two possibilities, we next examined the effects of PKI-amide, a peptide derived from an endogenous mammalian protein, termed the ‘Walsh inhibitor’, that is a potent and highly specific inhibitor of PKA (residues 5-24 amide; Walsh & Glass, 1991). PKI-amide had biphasic effects on the release of neurotransmitter evoked by presynaptic action potentials. Injection of PKI-amide into the giant presynaptic terminal inhibited synaptic transmission (Fig. 1C and D). This inhibition of transmitter release by PKI-amide was concentration dependent and reversible upon termination of peptide injection (Fig. 1D), indicating that the inhibition was due to the introduction of PKI-amide rather than to microinjection damage. The largest decrease in EPSP slope produced by PKI-amide was 41 % and the mean inhibition observed in eight experiments was 29 ± 4 % (±s.e.m.; Table 1).

Table 1.

PKI-amide and PKA substrate peptides inhibit synaptic transmission

| Peptide | Sequence | Number of injections | Amplitude inhibition (%) | kcal/Km (M−1 s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PepsynI | YLRRRLSDSNF | 3 | 62 ± 13 | 2 × 105 |

| PepCFTR | LQARRRQSVL | 2 | 81 ± 13 | 1.75 × 106 |

| PepARPP-21 | NQERRKSKSGAGK | 3 | 60 ± 9 | 1 × 105 |

| PepARPP-21mut | NQERRKTKSGAGK | 3 | 25 ± 15 | 3.6 × 102 |

| PKI-amide | TTYADFIASGRTGRRNAIHD | 8 | 29 ± 4 | — |

Peptides correspond to amino acid residues 3–13 of rat synapsin Ia (pepsynI), amino acid residues 761–770 of human CFTR (pepCFTR), amino acid residues 49–61 of bovine ARPP–21 (pepARPP–21 and pepARPP–21mut) and amino acid residues 5–24 of Walsh inhibitor (PKI-amide). The consensus sequences for PKA phosphorylation are boxed. Postsynaptic responses were measured just before and at the peak of inhibition of the indicated peptides. kcat and Km are Michaelis-Menten kinetics parameters. Inhibition data are means ± s.e.m.

In addition to the inhibitory effect, PKI-amide injection also caused an initial, transient enhancement of postsynaptic responses. This modest enhancement was probably due to an increase in the amplitude and duration of the presynaptic action potential (Fig. 1C). The two opposing effects of this peptide presumably account for a partial net inhibition of synaptic transmission by PKI-amide.

Presynaptic effects of exogenous PKA substrate peptides

While the inhibitory actions of PKI-amide are consistent with the hypothesis that PKA is tonically active at the squid presynaptic terminal, the dual effects of this peptide complicate interpretation of its actions. As an alternative means of interfering with PKA activity, we injected peptides containing the phosphorylation sites of various PKA substrates that are not present in the squid presynaptic terminal. The rationale was that these peptides should compete with the PKA substrates within the terminal and thereby decrease their phosphorylation state, thus interfering with the downstream effects of PKA.

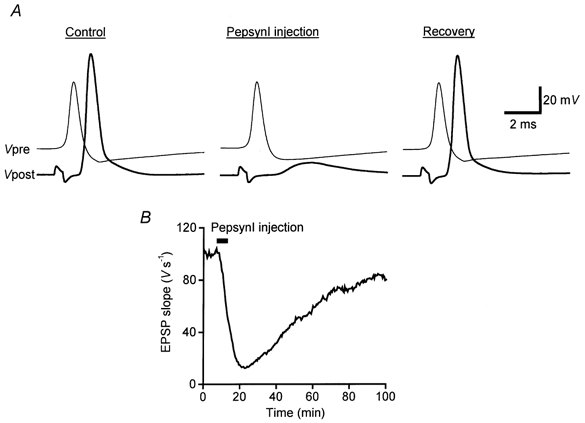

We first tested the effect of a peptide corresponding to residues 3-13 amide of rat synapsin I. This peptide, termed pepsynI, is an excellent substrate for PKA in vitro (kcat/Km= 2 × 105m−1 s; M. Picciotto & A. C. Nairn, personal communication). Except for the presence of a conserved consensus site for phosphorylation by PKA, the sequence of this peptide differs from that of the homologous region in domain A of squid synapsins (Hilfiker et al. 1998). Thus, pepsynI should selectively interfere with endogeneous PKA activity, rather than the interactions of endogenous synapsin with other proteins. Injection of pepsynI inhibited neurotransmitter release (Fig. 2A). This peptide did not alter the presynaptic resting potential or action potentials and there was no transient enhancement of transmitter release as was observed for PKI-amide. As a result, the inhibitory effect of pepsynI was measurable within 60 s after the start of the injection (Fig. 2B). The effects of this peptide were reversible, with a maximum 88 % decrease of EPSP slope and a mean decrease of 62 ± 13 % (±s.e.m., n= 3; Table 1).

Figure 2. Effect of pepsynI substrate peptide on transmitter release.

A, examples of presynaptic (Vpre) and postsynaptic (Vpost) responses recorded before (Control, 6 min after the start of recording), during (23 min) and after (Recovery, 97 min) injection of a PKA substrate, pepsynI. B, injection of pepsynI led to a drastic and reversible inhibition of neurotransmitter release. PepsynI was present at 40 mm in the injection electrode.

We next examined the actions of a peptide corresponding to residues 761-770 of the human cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), termed pepCFTR (Gadsby & Nairn, 1994). This peptide is an excellent substrate for PKA in vitro (kcat/Km= 1.75 × 106m−1 s), even though the comparable region of the native CFTR protein is inaccessible to kinases (Picciotto et al. 1992). Thus, even in the unlikely case that a homologue of CFTR was present in the squid presynaptic terminal, pepCFTR could not interfere with CFTR function in vivo. As a result, injected pepCFTR should only serve as an exogenous substrate for PKA within the terminal. PepCFTR injection decreased EPSPs elicited by presynaptic action potentials (Fig. 3A). This effect began rapidly, within 60 s after the start of peptide injection, and was not associated with any changes in presynaptic resting or action potentials. The inhibitory effect of pepCFTR was reversible and caused a maximum inhibition of EPSP slope of 93 %, with a mean inhibition of 81 ± 13 % (±s.e.m., n= 2; Table 1).

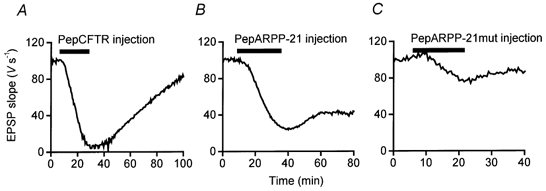

Figure 3. Effects of pepCFTR, pepARPP-21 and pepARPP-21mut substrate peptides on neurotransmitter release.

Differential effects of presynaptic injection of pepCFTR (A), pepARPP-21 (B) and pepARPP-21mut (C) on EPSP slope. Each peptide was present at 20 mm in the injection electrode.

We also injected a peptide corresponding to residues 49-61 of bovine ARPP-21 (pepARPP-21), which is a good substrate for PKA in vitro (kcat/Km= 1 × 105m−1 s; Hemmings et al. 1989). ARPP-21 is a protein that is enriched in dopamine-innervated brain regions (Hemmings et al. 1989) and thus is unlikely to be present at the squid presynaptic terminal. Presynaptic microinjection of pepARPP-21 inhibited neurotransmitter release within 4 min after the start of peptide injection and the effect partially reversed once peptide injection ceased (Fig. 3B). The inhibition of synaptic transmission occurred without any change in presynaptic resting or action potentials. PepARPP-21 inhibited EPSP slope maximally by 76 %, with a mean inhibition of 60 ± 9 % (±s.e.m., n= 3; Table 1).

As a control for the actions of pepARPP-21, we tested a mutated peptide (pepARPP-21mut) with a Ser to Thr substitution at residue 7 that makes it a poor substrate for PKA (kcat/Km= 3.6 × 102m−1 s; Hemmings et al. 1989). When microinjected into the squid presynaptic terminal, this peptide inhibited neurotransmitter release maximally by 51 %, with a mean inhibition of 25 ± 15 % (±s.e.m., n= 3; Table 1, Fig. 3C). The effect of this peptide was significantly less (Student’s t test, P > 0.25) than the inhibition produced by comparable injections of pepARPP-21. This suggests that the inhibition of transmitter release by pepARPP-21 is likely to be a consequence of its ability to act as a substrate for PKA. The differential actions of the four PKA substrate peptides on neurotransmitter release are summarized in Table 1. The presynaptic effects of these peptides correlated well with their apparent affinities as substrates for PKA in vitro (pepCFTR > pepsynI ∼ pepARPP-21 >> pepARPP-21mut) (Table 1), supporting the notion that these peptides acted by interfering with endogeneous PKA activity.

DISCUSSION

We have explored the role of PKA in transmission at the squid giant synapse. Inhibiting the activity of PKA, either by a selective inhibitor (PKI-amide) or by substrate peptides, led to a reversible inhibition of neurotransmitter release. In contrast, upregulating the activity of PKA by presynaptic injection of an exogenous, active form of the catalytic subunit caused no change in synaptic transmission. From these results, we conclude that the basal level of PKA activity at the squid giant synapse is high and that this activity tonically enhances neurotransmitter release elicited by single action potentials. The almost complete inhibition of neurotransmission by pepCFTR, the most effective in vitro PKA substrate, suggests that tonic activity of PKA may even be obligatory for neurotransmitter release at the squid giant synapse.

While this conclusion is contrary to the more generally accepted notion that PKA activity is dynamically regulated during intermittant periods of intracellular signal transduction, our findings are in agreement with biochemical indications of high PKA activity in the cytoplasm of squid neurons (Takahashi et al. 1995) and with observations that pharmacological agents that increase intracellular cAMP levels (forskolin and a cAMP-dependent phosphodiesterase inhibitor) has no effect on transmission at the squid synapse (M. P. Charlton & G. J. Augustine, unpublished observations). PKA contrasts with other presynaptic protein kinases, such as protein kinase C (Osses et al. 1989) and calcium- calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (Llinas et al. 1985, 1991), whose activity can be up-regulated to enhance transmission at the squid giant synapse. The effects of PKA vary among synapses: while PKA enhances neurotransmitter release in many cases, at some synapses blockade of PKA activity has no effect (Weisskopf et al. 1994) or can decrease neurotransmitter release (Tzounopoulos et al. 1998). PKA-dependent potentiation of release can even vary between individual presynaptic boutons of a neuron (Chavis et al. 1998). Thus, it appears that the basal level of PKA activity varies at different synapses and can cause transmitter release to be differentially sensitive to enhancement or inhibition of PKA. Perhaps the most general function of PKA is to set the initial efficacy of synaptic transmission, upon which other influences, such as synaptic activity or additional protein kinases, can be superimposed.

Inhibition of PKA by PKI-amide, but not by PKA substrate peptides, also led to a reversible increase in the amplitude and a widening of the shape of the presynaptic action potential, accompanied by a transient increase in transmitter release. These changes are probably due to a PKA-dependent increase in the activity of Na+ channels and/or a decrease in the activity of K+ channels, as has been reported in other cell systems (Siegelbaum et al. 1982; Alkon et al. 1983; Madison & Nicoll, 1986; Li et al. 1992). This selective effect of PKI-amide might be due to a combination of factors, including the existence of at least two distinct subcellular pools of PKA (Faux & Scott, 1996) and the broad differential affinities of the inhibitor and substrate peptides for PKA (Ki= 1.6 nm versus Km= 10-1000 μm, respectively).

The peptide-mediated inhibition of release was not accompanied by equivalent changes in the shape of the presynaptic action potential. While this suggests that the inhibition is not due to effects on presynaptic ion channels, the presynaptic action potential mainly arises from Na+ and K+ currents. Thus, it remains possible that part of the inhibition is due to PKA-mediated changes in Ca2+ channel current. Given the documented effects of PKA downstream from Ca2+ influx (Capogna et al. 1995; Trudeau et al. 1996; Chavis et al. 1998), we suspect that a phosphorylation-dependent regulation of the exocytotic apparatus is primarily involved. While the precise downstream targets of PKA are currently unknown, several synaptic proteins have been shown to be substrates for PKA in vitro. Examples include rabphilin (Lonart & Sudhof, 1998), SNAP-25 (Risinger & Bennett, 1999) and α-SNAP (Hirling & Scheller, 1996), all proteins that are involved in neurotransmitter release at the squid synapse (Augustine et al. 1999). Thus, it seems likely that PKA modulates the efficacy of synaptic vesicle exocytosis by phosphorylating one or more proteins involved in synaptic vesicle trafficking reactions, thereby regulating the efficacy of these steps in the exocytotic process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Rockefeller University Abroad Program Fellowship to S.H., NIH grant MH-39327 to P.G. and NIH grant NS-21624 to G.J.A.

References

- Alkon DL, Acosta-Urquidi J, Olds J, Kuzma G, Neary JT. Protein kinase injection reduces voltage-dependent potassium currents. Science. 1983;219:303–306. doi: 10.1126/science.6294830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Burns ME, Debello WM, Hilfiker S, Morgan J, Schweizer FE, Tokumaru H, Umayahara K. Proteins involved in synaptic vesicle trafficking. Journal of Physiology. 1999;520:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00033.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, Gaehwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic enhancement of inhibitory synaptic transmission by protein kinases A and C in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:1249–1260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01249.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Stevens CF. Increased transmitter release at excitatory synapses produced by direct activation of adenylate cyclase in rat hippocampal slices. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:310–317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00310.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis P, Mollard P, Bockaert J, Manzoni O. Visualization of cyclic AMP-regulated presynaptic activity at cerebellar granule cells. Neuron. 1998;20:773–781. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Regehr WG. The mechanism of cAMP-mediated enhancement at a cerebellar synapse. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:8687–8694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08687.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faux MC, Scott JD. More on target with protein phosphorylation: conferring specificity by location. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1996;21:312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsby DC, Nairn AC. Regulation of CFTR channel gating. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1994;19:513–518. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P, Jen J, Nairn AC, Stevens CF. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase enhances glutamate response in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Science. 1991;253:1135–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1716001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross RA, Uhler MD, Macdonald RL. The cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit selectively enhances calcium currents in rat nodose neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1990;429:483–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings HC, Girault J-A, Williams KR, Lopresti MB, Greengard P. ARPP-21, a cyclic AMP-regulated phosphoprotein (Mr = 21,000) enriched in dopamine-innervated brain regions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1989;264:7726–7733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilfiker S, Schweizer FE, Kao H-T, Czernik AJ, Greengard P, Augustine GJ. Two sites of action for synapsin domain E in regulating neurotransmitter release. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:29–35. doi: 10.1038/229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirling H, Scheller RH. Phosphorylation of synaptic vesicle proteins: Modulation of the αSNAP interaction with the core complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:11945–11949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-Y, Li X-C, Kandel ER. cAMP contributes to mossy fiber LTP by initiating both a covalently mediated early phase and macromolecular synthesis-dependent late phase. Cell. 1994;79:69–79. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, West JW, Lai Y, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Functional modulation of brain sodium channels by cAMP-dependent phosphorylation. Neuron. 1992;8:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, Gruner JA, Sugimori M, McGuinness TL, Greengard P. Regulation by synapsin I and Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II of transmitter release in squid giant synapse. Journal of Physiology. 1991;436:257–282. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R, McGuinness TL, Leonard CS, Sugimori M, Greengard P. Intraterminal injection of synapsin I or calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alters neurotransmitter release at the squid giant synapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1985;82:3035–3039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.9.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonart G, Sudhof TC. Region-specific phosphorylation of rabphilin in mossy fiber nerve terminals of the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:634–640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00634.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison DV, Nicoll RA. Cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate mediates β-receptor actions of noradrenaline in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. Journal of Physiology. 1986;372:245–259. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osses LR, Barry SR, Augustine GJ. Protein kinase C activators enhance transmission at the squid giant synapse. Biological Bulletin. 1989;177:146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto M, Cohn J, Bertuzzi G, Greengard P, Nairn AC. Phosphorylation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:12742–12752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger C, Bennett MK. Differential phosphorylation of syntaxin and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) isoforms. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;72:614–624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin PA, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Cyclic AMP mediates a presynaptic form of LTP at cerebellar parallel fiber synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:797–803. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegelbaum SA, Camardo JS, Kandel ER. Serotonin and cyclic AMP close single K+ channels in Aplysia sensory neurones. Nature. 1982;299:413–417. doi: 10.1038/299413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Amin N, Grant P, Pant HC. P13suc1 associates with a cdc2-like kinase in a multimeric cytoskeletal complex in squid axoplasm. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6222–6229. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06222.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau L-E, Emery DG, Haydon PG. Direct modulation of the secretory machinery underlies PKA-dependent synaptic facilitation in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1996;17:789–797. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau L-E, Fang Y, Haydon PG. Modulation of an early step in the secretory machinery in hippocampal nerve terminals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1998;95:7163–7168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzounopoulos T, Janz R, Sudhof TC, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. A role for cAMP in long-term depression at hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 1998;21:837–845. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80599-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DA, Glass DB. Utilization of the inhibitor protein of adenosine cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase, and peptides derived from it, as tools to study adenosine cyclic monophosphate-mediated cellular processes. Methods in Enzymology. 1991;201:304–316. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)01027-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf MG, Castillo PE, Zalutsky RA, Nicoll RA. Mediation of hippocampal mossy fiber long-term potentiation by cyclic AMP. Science. 1994;265:1878–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.7916482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]