Abstract

Excitation and sensitization to heat of nociceptors by bradykinin (BK) were examined using an isolated rat skin-saphenous nerve preparation.

A total of 52 C-fibres was tested: 42 were mechano-heat sensitive (CMH) and 40 % of them were excited and sensitized to heat by BK superfusion (10−5m, 5 min) of their receptive fields; heat responses were augmented by more than five times and heat thresholds dropped to 36.4 °C, on average.

Sixty per cent of the CMH did not respond to BK itself, but 3/4 of these units showed an increase in their heat responses by more than 100 % following BK exposure.

Ten high-threshold mechanosensitive C-fibres did not discharge upon BK application but following this five of them responded to heat in a well-graded manner.

In all fibres, the sensitizing effect of BK was abolished within 9 min or less of wash-out, and it could be reproduced several times at equal magnitude, whereas the excitatory effect of BK regularly showed profound tachyphylaxis.

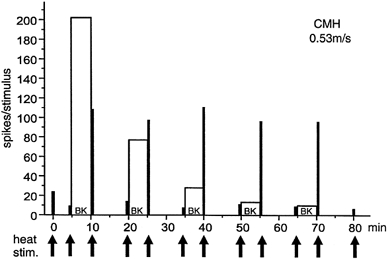

Sustained superfusion (20 min) of BK induced a desensitizing excitatory response while superimposed heat responses showed constant degrees of sensitization.

The large extent and high prevalence of BK-induced sensitization (almost 80 % of all fibres tested) and de novo recruitment of heat sensitivity suggest a prominent role of BK not only in hyperalgesia but also in sustained inflammatory pain which may be driven by body or even lower local temperatures acting on sensitized nociceptors.

Based on the latter assumption, a hypothesis is put forward that excludes a direct excitatory effect of BK on nociceptors, but assumes a temperature-controlled activation as a result of rapid and profound sensitization.

Among the endogenous algogens and inflammatory mediators, bradykinin (BK), serotonin, prostaglandins and histamine, BK has been found to be the most effective agent acting on cutaneous nociceptors in the rat (Lang et al. 1990; Handwerker & Reeh, 1991; Reeh 1994). These studies, however, have shown that BK alone activates less than half of the C-fibres in the rat skin. This prevalence is much lower than that in deep tissues where it has been reported to be about 90 % (Baker et al. 1980; Kumazawa & Mizumura, 1980; Haupt et al. 1983; Kanaka et al. 1985). In addition, the excitatory effect of BK on nociceptive nerve fibres appears to be transient and prone to tachyphylaxis (Kumazawa et al. 1987; Lang et al. 1990; Koltzenburg et al. 1992). Moreover, the BK concentrations needed to excite nerve endings (≈10−6m) are clearly higher than those determined in exudates of painful inflammations (Handwerker & Reeh, 1991). Together, these arguments seem to indicate that the excitatory effect of BK is less important in the overall induction of pain.

On the other hand, BK-induced sensitization of primary afferent nociceptors to heat (Kumazawa et al. 1991; Khan et al. 1992; Koltzenburg et al. 1992; Schuligoi et al. 1994), mechanical (Levine et al. 1986; Steranka et al. 1988; Neugebauer et al. 1989) and endogenous chemical (Kessler et al. 1992; Koppert et al. 1993; Vyklickýet al. 1998) stimulation has been well established. The sensitizing effects of BK have been reported to be more sustained than the excitatory ones (Neugebauer et al. 1989; Manning et al. 1991), and they can occur independently of BK inducing discharge (Beck & Handwerker, 1974; Khan et al. 1992). In the monkey skin, it has been reported that all mechano-heat-sensitive fibres are sensitized to heat stimulation by BK, but only some of them show an excitatory response to the chemical stimulus itself (Khan et al. 1992). Therefore, the sensitizing rather than excitatory effect of BK seems to be the more important one, inducing and eventually maintaining hyperalgesia and pain from harmless stimuli.

In rat and monkey skin it has been shown that BK sensitizes the afferent units to heat but not to mechanical stimulation (Lang et al. 1990; Koltzenburg et al. 1992; Khan et al. 1992). Vice versa, previous heat stimulation was found to leave the afferents with prolonged sensitization to BK stimulation and could even uncover a latent BK responsiveness in units which were previously not excited by BK (Beck & Handwerker, 1974; Lang et al. 1990; Mizumura et al. 1992). These observations suggest a particular functional interrelationship in the transduction of heat and BK stimuli. It is conceivable that such a mutual sensitization may play an important role in inflammatory pain and hyperalgesia since both local temperature and BK concentration are increased and maintained at high levels in inflamed tissue (Hargreaves et al. 1988; Damas et al. 1990). However, little is known about the persistence or possible tachyphylaxis of the sensitizing effect and to what extent BK can induce heat sensitization in the majority of nociceptive fibres which are not excited by BK or insensitive to heat. To answer these questions we have performed the present study using isolated rat skin and recordings from unmyelinated nociceptive nerve fibres.

A short account of the present work has previously been published in abstract form (Haake et al. 1996).

METHODS

Preparation and neurophysiological recording

The in vitro rat skin-saphenous nerve preparation and the single-fibre recording technique were used in the present study. Preparation and recording have previously been described and validated in detail (Reeh, 1986; Kress et al. 1992). Twenty-six male Wistar rats weighing 300-400 g were deeply anaesthetized with thiopental sodium (120 mg kg−1, i.p.). The skin of both hindpaws was excised with the corresponding saphenous nerves in continuity. The rats were then killed by intracardial injection of lidocaine hydrochloride (1 %, 1 ml). The procedures were in accordance with the German Animal Protection Law (1987) and approved by the District Government.

The skin flap was mounted in an organ bath with the corium side up and superfused (16 ml min−1) with synthetic interstitial fluid (SIF; Bretag, 1969) at 32 °C which was continuously aerated with carbogen gas (95 % O2, 5 % CO2) resulting in a pH around 7.4. The saphenous nerve stem was threaded through a hole into an adjacent recording chamber and placed on a small mirror platform where it was covered with paraffin oil. Using the standard teased-fibre technique single-unit activity was recorded through gold wire electrodes. Electrical search stimulation was applied via a fine needle electrode (insulated with Teflon up to 3 mm of the tip) that was pierced through the nerve stem into the Sylgard bottom of the organ bath. A blunt glass rod was used to search and localize the receptive field of single units by probing the corium side of the skin. To determine the conduction velocity, a Teflon-coated steel microneurography electrode (bare tip diameter 5-10 μm, impedance 1-5 MΩ) was inserted into the skin and used to stimulate the receptive field (pulse width 0.5 ms, train frequency 0.2 Hz, variable intensity). The indifferent electrode was placed nearby in the organ bath.

Mechanical, thermal and chemical stimulation

Mechanical stimuli from a set of 18 von Frey hairs, calibrated from 1 to 326 mN, were applied to the most sensitive point of the receptive field on the corium side to determine the mechanical threshold of a unit. A metal ring (diameter 8-12 mm) was then placed on the receptive field and evacuated. The heat and cold responsiveness were subsequently examined. Controlled heat stimulation was performed by focusing a halogen bulb through the translucent bottom of the organ bath and linearly raising the temperature measured at the corium side from 32 to 46 °C over 20 s, which corresponds to a rise from 32 to 52 °C at the epidermal surface (Reeh, 1986). The cold stimulation was performed by filling the metal ring with SIF at 4 °C, by which the receptive field was cooled down to a minimum temperature of 7 °C on the corium side.

Chemical stimulation was applied to those units which had a conduction velocity less than 1.0 m s−1 and a mechanical threshold of more than 16 mN; thus, low-threshold mechanoreceptive C-fibres were excluded from the study. The receptive field of such units, isolated from its surrounding by the metal ring, was superfused with a BK solution of 10−5m at pH 7.3, which is the concentration that is able to excite all BK-sensitive CMH-fibres in the rat skin-nerve preparation (Lang et al. 1990). All superfusions were carried out at a turbulent flow rate of 3 ml min−1 and at a temperature of 32 °C. In most cases BK was applied for 5 min, followed within 30 s by heat and then mechanical stimulation. If the fibre was activated by BK itself and/or sensitized to heat, the same procedure was repeated at 10 min intervals up to five trials if possible. In some cases, the receptive field was superfused with the BK solution for 20 min continuously and heat stimuli were applied every 5 min.

Data processing

Fibres with a conduction velocity of less than 1.0 m s−1 were considered to be unmyelinated C-fibre units. Single-unit action potentials were recorded with a low-noise AC-coupled amplifier and monitored continuously on an oscilloscope and through a loudspeaker. For further analysis the recordings were digitized (12-bit AD-converter, 4 kHz sampling rate) and processed in a PC-type laboratory computer, using the DAP 1200 interface card (Microstar, Redmond, WA, USA). The Spike/Spidi software package which allows for spike discrimination by a template-matching procedure, was used for off-line analysis (Forster & Handwerker, 1990). Heat thresholds were determined as the temperature at which the second action potential of the response occurred. The magnitude of the heat and the BK responses was assessed as the total number of spikes evoked during either stimulus duration. A heat response was considered sensitized when the increase in the number of spikes after BK application was at least 100 %. Means ± standard errors of the mean (s.e.m.) were used to indicate the average values. For statistical analysis the Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used. Differences were considered to be significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Population of units tested

Altogether 52 fibres, which had conduction velocities ranging from 0.3 to 0.9 m s−1 and mechanical thresholds between 16 and 181 mN, were classified as C-fibres, 42 units of which showed a response to heat stimulation prior to BK application with intracutaneous heat threshold temperatures ranging from 38 to 46 °C and were categorized as mechano-heat sensitive (CMH). Ten C-fibres had von Frey thresholds higher than 45 mN, did not respond to heat or cold stimuli prior to the chemical stimulus and were therefore taken as high-threshold mechanosensitive units (C-HTM). None of the C-fibres tested in this study was initially spontaneously active.

Excitation and sensitization by BK

Seventeen of forty-two units (40.5 %) of the CMH-fibre group were excited during superfusion of BK (10−5m) and all were afterwards found to be sensitized to heat (by at least 100 %) (Fig. 1A). Twenty-five of forty-two fibres (59.5 %) were not excited by BK itself and were therefore counted as BK-unresponsive CMH-fibres. Nineteen of these twenty-five units (76 %) not excited by BK showed a heat response following BK treatment that comprised at least 100 % more spikes than before; the other 6/25 fibres (24 %) were neither excited nor markedly sensitized to heat by BK. In the group of the C-HTM-fibres none was excited; however, 5/10 units (50 %) clearly responded to heat stimulation after superfusion of their receptive fields with BK (Fig. 1B and 7). There were no significant differences in conduction velocities and in von Frey thresholds between BK-responsive and -unresponsive CMH-fibres; also the initial heat responses were not different with respect to threshold, number of spikes and stimulus-response relationship (Fig. 6).

Figure 1. Summary of the 52 C-fibres tested.

BK-responsive and -unresponsive fibres were sensitized to heat by BK (filled part of the columns) or not sensitized (open part of the columns). A, of the 42 CMH-fibres 17 were excited and sensitized by BK, whereas 25/42 CMH-fibres were not excited, but 19 were sensitized to heat stimulation following BK superfusion; 6/25 CMH were neither excited nor sensitized by BK. B, none of 10 C-HTM-fibres responded to heat stimuli prior to BK administration and none was excited by BK; after BK 5/10 C-HTM-fibres reversibly responded to heat stimuli (see Fig. 7). Altogether 79 % of the C-fibres tested were sensitized to heat by BK. See Methods for criteria of sensitization and excitation.

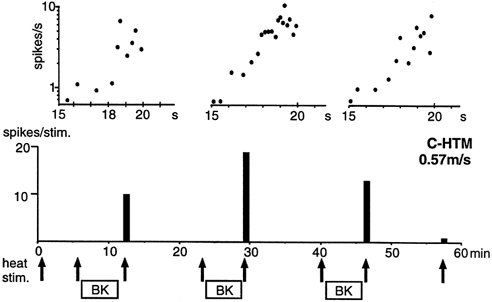

Figure 7. De novo responsiveness to heat after BK superfusion in C-HTM-fibres.

Example of a C-HTM-fibre that was repeatedly sensitized to heat by BK. Lower panel, the heat stimuli are indicated with arrows. The filled columns show the number of spikes per heat stimulus. Upper panel, the heat responses of the fibre recorded after BK applications are shown on an expanded time scale in a semi-logarithmic plot of the instantaneous discharge rate. Each dot represents one spike; the time scale refers to seconds after initiation of the 20 s heat stimulus (same shape as in Fig. 2A). Note the roughly linear increases of the spike rate (with Q10≈ 30) during the last 5 s of the heat stimulations which correspond to a temperature increase of 42.4-46 °C (i.e. at time 15-20 s).

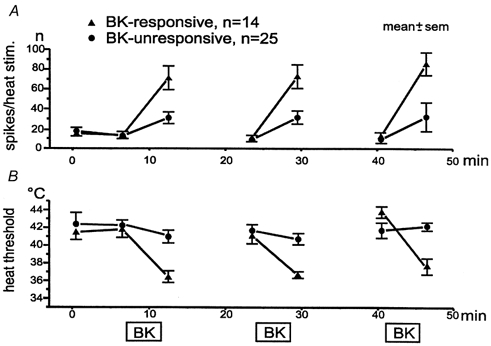

Figure 6. Heat sensitization is different in BK-responsive versus -unresponsive units.

Averaged heat responses and thresholds of BK-responsive and -unresponsive CMH units exposed to repeated superfusion with BK. A, number of spikes per heat stimulus of 20 s duration. B, heat threshold temperatures.

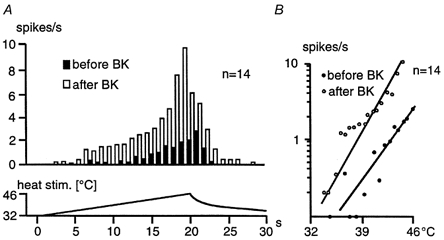

Fourteen of the seventeen BK-responsive fibres were tested with repeated BK applications (10−5m for 5 min) at 10 min intervals and with heat stimuli before and shortly after each chemical stimulation. All these units showed an increase in the magnitude of their heat response and a decrease in threshold temperature after the BK superfusions: across the first administration, for example, the mean discharge increased significantly from 13.6 ± 5.2 to 71.4 ± 19.1 spikes (20 s)−1 of heat stimulation (P < 0.01) and the mean heat threshold dropped by 5.4 °C (P = 0.01). Figure 2A shows averaged histograms of these heat responses. In comparison, the sensitized heat response was not only enhanced in general and showed a lower threshold temperature, but the histogram shows that the peak discharge also appeared earlier, i.e. at lower than maximum temperature. Thereafter, the discharge declined while the stimulus temperature was further increasing - a characteristic finding with sensitized nociceptors suggesting an enhanced rate of adaptation (Koltzenburg et al. 1992). The mean stimulus-response functions are obtained as regression lines calculated from threshold to peak discharge, showing a leftward shift and an increase in slope (from Q10≈ 23 to 40) upon BK administration.

Figure 2. BK-induced sensitization to heat of CMH-fibres excited by BK.

A, averaged histogram of the heat responses before and after BK application in relation to the linearly increasing intradermal temperature (lower trace). The mean number of spikes per heat stimulus increased significantly after the BK application (P < 0.01; Wilcoxon matched pairs test). Note the decline of the sensitized heat response before peak temperature is reached, suggesting that activation as well as inactivation (adaptation) of the stimulus transduction mechanism are temperature dependent and facilitated by BK. B, semi-logarithmic stimulus-response functions obtained from the beginning of the response to peak discharge corresponding to the data in A. Note that the regression line approximating the stimulus-response function is shifted leftward after BK superfusion with an increase in slope (Q10≈ 40 versus 23 before BK) and that both heat threshold and peak discharge are shifted towards lower temperatures.

Tachyphylaxis to BK but sustained sensitization

A representative example of a CMH-fibre which received five successive BK superfusions shows a marked decrease in BK-induced discharge, whereas the sensitization to heat could be reproduced four times with similar magnitude and rapid wash-out (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Repeated heat sensitization by BK of polymodal nociceptor.

Example of a BK-responsive CMH-fibre which responded to five BK applications. The responses to BK itself (open columns) show a strong tachyphylaxis, whereas the transient sensitization to heat (heat responses, filled columns) by BK could be reproduced four times at similar magnitude.

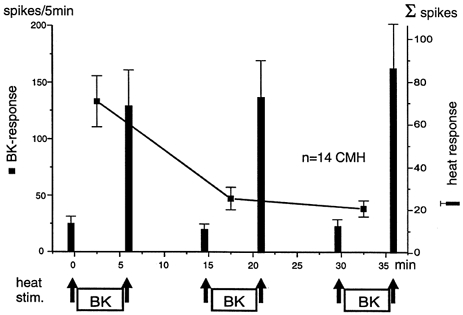

All the 14/17 CMH-fibres tested with repeated BK applications showed a marked, progressive decrease of their excitatory responses. As shown in Fig. 4, the mean BK response dropped significantly from 133.1 ± 35.6 spikes during the first to 47.3 ± 12.6 spikes during the second BK application (P < 0.01) and again to the third application with 38.3 ± 10.2 spikes (P = 0.24). In contrast, the response to heat stimulation was significantly increased after each BK application and significantly decreased again after the wash-out periods (P < 0.01): the mean enhancement was by a factor of 5.25, 6.7 and 6.8, respectively. The three mean heat responses before the BK superfusions were not significantly different from each other and the same was true for the sensitized heat responses (P > 0.24).

Figure 4. No tachyphylaxis of BK-induced heat sensitization.

Averaged responses ±s.e.m. of 14 BK-responsive CMH-fibres to BK and to heat stimulation. The heat stimuli applied before and after each BK administration are indicated by arrows. The responses to BK (filled squares) show the well documented tachyphylaxis. The difference between the first and the second response to BK was significant (P < 0.01; Wilcoxon matched pairs test). The responses to heat stimulation (filled columns) were significantly increased after each BK superfusion and significantly decreased again after the wash-out periods (P < 0.01). Note the apparent complete lack of tachyphylaxis of the sensitizing BK effect.

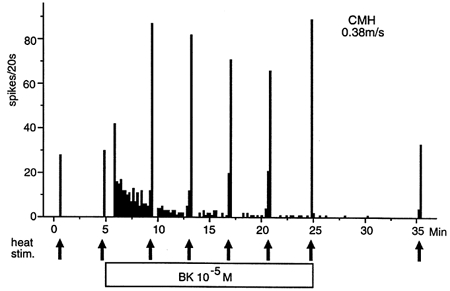

The other 3/17 BK-responsive CMH-fibres were treated with BK superfusion over a period of 20 min. They all showed a monotonously declining BK discharge, whereas their responses to heat stimuli applied every 5 min remained constantly elevated. After a final wash-out period of 10 min the heat responses were again as before the BK application. Figure 5 shows an example recorded from a unit that presented with the longest lasting BK-induced discharge.

Figure 5. BK induces transient excitation but sustained sensitization to heat.

Example of a BK-responsive CMH-fibre that was treated with BK continuously over a period of 20 min. The heat stimuli applied are indicated by arrows. The BK response shows a strong desensitization whereas the superimposed heat responses remain constantly elevated. This result was reproduced with two other CMH-fibre units.

Heat sensitization without excitation by BK

All 25 BK-unresponsive CMH-fibres were tested with repeated BK superfusions but not excited. Six of these CMH-fibres were not sensitized to heat by repeated BK applications when sensitization was again defined as an increase in number of heat-induced spikes by more than 100 %. There were no significant differences in number of spikes between the first two heat responses prior to BK superfusion nor between the BK-responsive and -unresponsive fibre populations (Fig. 6A). However, after the BK administrations the fibres, which had not been excited by BK, clearly showed much smaller, though still significant (P < 0.01, 0.01 and 0.04) and reproducible, increases in heat-induced discharge than the BK-responsive ones.

The BK-responder and non-responder populations showed slightly different mean heat threshold temperatures of 41.5 ± 0.9 and 42.2 ± 1.3 °C, respectively (not significant). The BK-induced threshold decreases were clearly smaller in BK-unresponsive than -responsive fibres, though significant in both populations (P = 0.03 and 0.02, respectively). Only after the third BK superfusion did the BK non-responder population fail to show threshold decrease, although the number of spikes in the respective heat response was still significantly enhanced (Fig. 6B).

Heat sensitization de novo by BK

Five of the ten C-HTM-fibres that were previously unresponsive to heat responded to heat stimulation after the first BK application with a median number of only 4 spikes and a median heat threshold temperature of 42 °C (Fig. 7). The number of spikes per heat response ranged from 1 to 18. Ten minutes later, after wash-out of BK, none of the previously recruited fibres delivered a single spike upon the repeated heat stimulation. The median heat response was again 4 spikes (ranging from 2 to 48 spikes) and the median threshold temperature was 42.5 °C after the second BK application. Only three fibres could be tested with a third BK application and their heat responses ranged from 13 to 45 spikes (threshold temperatures 40-43 °C). An example of such a C-HTM-fibre is shown in Fig. 7; it is representative in that the instantaneous discharge frequencies closely matched the ramp-shaped rise in temperature (upper panels).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we confirmed in isolated rat skin that more than 80 % of the primary cutaneous CMH-afferents, the most frequent ‘polymodal’ type of nociceptor in the skin, are strongly sensitized to heat stimulation by bradykinin, and that this can occur without any previous excitation by BK. A novel finding was that the sensitization was much stronger in BK-responsive than -unresponsive nerve endings. For the first time also, de novo recruitment by BK of heat responsiveness in 50 % of previously unresponsive mechanonociceptors could be demonstrated. However, the main new finding in the present work was the apparently complete lack of tachyphylaxis or desensitization to BK in respect to its heat-sensitizing effect and in open contrast to the excitatory effect which showed the usual decrease upon repeated or sustained BK administration. Together, these results corroborate the concept that BK is of particular importance in inducing hyperalgesia and, by that, maintaining inflammatory pain.

The molecular requisites to integrate the phenomena observed here are bradykinin receptors, the signal transduction pathways and heat-activated ion channels. Bradykinin is thought to act on neurons through the constitutive B2 receptor, as the B1 receptor is mainly expressed during sustained inflammation (Davis & Perkins, 1994). Like other inflammatory mediators, bradykinin receptors are coupled to Gq/11 proteins activating phospholipase C and finally, through diacylglycerol, the calcium-independent ε-subtype of protein kinase C (PKC; Cesare et al. 1999). Based on evidence from cultured dorsal root ganglion cells taken as a model of the nociceptive terminal, the excitatory as well as the heat-sensitizing effects of bradykinin could be attributed to activation of protein kinase C (Burgess et al. 1989; Cesare & McNaughton, 1996). Direct stimulation of PKC by phorbolesters induced excitation and sensitization to heat in visceral nociceptors, in vitro, and showed cross-tachyphylaxis (heterologous desensitization) with bradykinin (Leng et al. 1996; Mizumura et al. 1997). The target of the protein kinase action in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells are the heat-activated ion channels showing two rapid and marked effects (of BK): decrease of the temperature threshold and increase of the depolarizing cation conductance (Cesare & McNaughton, 1996; Vyklickýet al. 1999). VR1, the cloned ionotropic capsaicin receptor, is a good model of a heat-transduction molecule but it cannot be the only one since VR1 knock-out mice retain noxious heat responsiveness to a certain extent (Caterina et al. 2000; Davis et al. 2000).

While PKC activation dominates in the acute effects of bradykinin, the lasting and after-effects involve stimulation of eicosanoid formation; also prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) can induce heat hyperalgesia in rats and sensitization to heat of testicular nociceptors (McGuirk & Dolphin, 1992; Mizumura et al. 1993; Schuligoi et al. 1994). In addition to phospholipase C, B2 receptors activate phospholipase A2 and at the end of this cascade, involving prostaglandin receptors and cAMP, protein kinase A is activated, which finally mediates a heat-sensitizing effect (Cui & Nicol, 1995; Kress et al. 1996; Pizard et al. 1999). Complicating the picture, there is biochemical evidence for multiple cross-talk between the pathways to PKA and PKC activation (Graness et al. 1997).

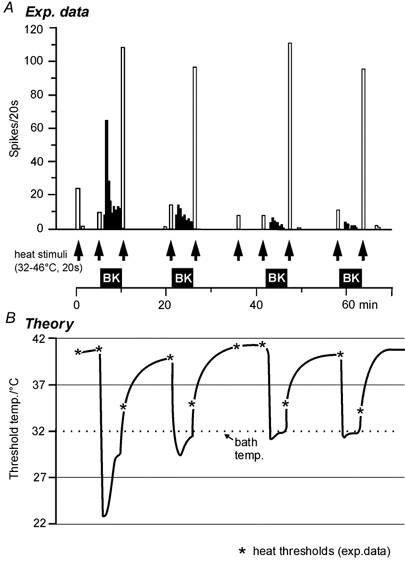

Up to PKC activation, at least, the outlined sequence of events is the same for excitation and sensitization by BK. In the present work, however, the excitation showed the usual tachyphylaxis (homologous desensitization) while the heat-sensitizing effect was reproducible and sustained in an apparently constant manner. The desensitization to BK involves ligand-dependent internalization and phosphorylation of the B2 receptors (Pizard et al. 1999). How could such a basic mechanism possibly affect the excitatory but spare the sensitizing effect of BK? In our view, the only way out of this dilemma is to assume that the sensitizing effect was not that constant but was actually much larger during the early phase of BK action, i.e. during the period of excitation when testing heat sensitivity was precluded by the ongoing discharge induced (Fig. 8). The peak of the sensitizing effect and its subsequent decline (‘desensitization’) may, thus, be hidden behind the apparent excitation by BK. If this was true, the excitation may virtually be the result, rather than the counterpart, of an extreme sensitization by which nociceptive heat thresholds drop far below the ambient temperature (of 32 °C in the organ bath). Thereby, the bath temperature in vitro or the body and tissue temperature in vivo would become an effective ‘heat stimulus’ to the sensitized nociceptors.

Figure 8. A novel theory of BK action.

A, histograms from a CMH-fibre responding to BK (filled columns) and to heat stimuli (open columns) demonstrate the apparent paradox of desensitizing (tachyphylactic) BK responses in contrast to the reproducible sensitization to heat by BK. B, the theoretical model excludes a direct excitatory effect of BK and suggests a supersensitizing action of BK that lowers nociceptive ‘heat’ thresholds far below ambient temperature of the preparation (32 °C). Thereby, the tissue temperature becomes a driving force for nociceptor discharge which is subject to adaptation and to desensitization to BK upon repeated (or prolonged) exposure. Residual desensitization to BK reduces the BK effect from trial to trial but with a tendency to level out. The measured heat thresholds (asterisks) are derived from the heat responses in A; the connecting lines are hypothetical and meant to reflect the BK-induced discharge in A.

There are examples of this speculation in previous studies. In cells expressing VR1 ‘capsaicin is not an agonist per se but functions as a modulatory agent, lowering the channel's response threshold to the ubiquitous actions of heat’ (Tominaga et al. 1998). Also in cultured DRG cells the thresholds of heat-activated currents drop from over 43 °C to room temperature within seconds after superfusion with capsaicin, bradykinin or pH 6.1 (Vyklickýet al. 1999).

In Fig. 8 a residual desensitization to BK is assumed to reduce the sensitizing and thereby the excitatory effect from trial to trial with a tendency to level out at assumed heat thresholds near bath temperature during BK superfusion. Similarly, in Fig. 5 the BK-induced discharge faded - by homologous desensitization and classical sensory adaptation - while the sensitized heat thresholds of the C-fibre settled around bath temperature. This is still 6 °C below normal body temperature of the rat and may be a reason for the ongoing discharge encountered in nociceptors innervating inflamed tissue in all animal models of inflammation (Reeh & Sauer, 1997).

Our idea that nociceptor excitation by BK is the ‘tip of an iceberg’ of heat sensitization is in accord with the finding that sensitization by BK is much more prevalent among nociceptors than excitation (80 versus 40 %), if one assumes that B2 receptor density may be different among nerve endings. This assumption would also explain our result that heat sensitization is much stronger in BK-responsive than non-responsive units, which probably are less well equipped with B2 receptors. De novo emergence of heat sensitivity in mechanonociceptive C-fibres had previously been observed after topical application of an irritant, mustard oil, to rat skin (Reeh et al. 1986). Part of these mechanonociceptors may be equipped with a few heat-activated channels which only become effective when sensitized by bradykinin and produce a heat response.

The relatively low prevalence of BK-induced nociceptor excitation in the skin (at 32 °C) is in contrast to about 90 % of the slow conducting afferents in ‘deep tissues’ being excited by BK, perhaps owing to the higher temperature in the body core (Baker et al. 1980; Kumazawa & Mizumura, 1980; Haupt et al. 1983; Kanaka et al. 1985). This corresponds with an amazingly high prevalence in deep tissues of mechano-heat-sensitive primary afferents which encode temperatures more than sufficient to kill immediately (Reeh & Pethö, 2000, for review). Noxious heat sensitivity in the depth of the body would make sense if, as speculated, heat-activated channels were needed to exert the apparent excitatory effects of bradykinin.

Compatible with the idea of excitation through sensitization are previous findings with BK, such as the general temperature dependency of the excitatory BK effect and the fact that much lower concentrations induce heat sensitization than excitation (Kumazawa & Mizumura, 1983; Kumazawa et al. 1991). One puzzle may also be resolved which is that BK-induced inward currents in cultured DRG cells can be recorded in some but not in other laboratories (Reeh & Pethö, 2000, for review). Patch-clamping is usually done at ‘room temperature’ which may be too low in some places to be reached by the dropping threshold of heat-activated channels under the influence of BK. Of course, these considerations are hypothetical but, at least, they are checkable, predicting that BK and perhaps other heat-sensitizing mediators or irritants should be devoid of excitatory actions if the ambient temperature is set sufficiently low. This would be in agreement with the medical routine of cooling injured, acutely inflamed or chemically irritated tissue which mostly leads to immediate pain relief - also under several experimental conditions (Reeh & Pethö, 2000, for review).

In conclusion, we have provided evidence that sensitization to heat is perhaps the only, certainly the predominant, effect of bradykinin on nociceptors, in particular since it can last for as long as the mediator is present. Nociceptor thresholds can drop and remain well below body temperature, suggesting that bradykinin may contribute to persistent inflammatory pain. Finally, a theory is presented that tries to unify the mechanisms of excitation and sensitization by bradykinin, attributing the quantitative differences to tachyphylaxis (homologous desensitization) and to different BK receptor densities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 353-B12 and by a fellowship (to Y.-F. L.) of the Japanese government. We thank Dr S. Sauer for supervising part of the experiments, Dr G. Pethö for carefully reading the manuscript and I. Izydorczyk for expert technical assistance.

References

- Baker DG, Coleridge JGG, Nerdum T. Search for a cardiac nociceptor: stimulation by bradykinin of sympathetic afferent nerve endings in the heart of the cat. Journal of Physiology. 1980;306:519–536. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck PW, Handweker HO. Bradykinin and serotonin effects on various types of cutaneous nerve fibres. Pflügers Archiv. 1974;374:209–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00592598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretag A. Synthetic interstitial fluid for isolated mammalian tissue. Life Sciences. 1969;8:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(69)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess GM, Mullaney I, Mc Neill M, Dunn PM, Rang HP. Second messengers involved in the mechanism of action of bradykinin in sensory neurons in culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1989;9:3314–3325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-09-03314.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina JM, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and painsensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P, Dekker LV, Sardini A, Parker PJ, McNaughton P. Specific involvement of PKC-epsilon in sensitization of the neuronal response to painful heat. Neuron. 1999;23:617–624. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P, McNaughton P. A novel heat-activated current in nociceptive neurons and its sensitization by bradykinin. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:15435–15439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M, Nicol GD. Cyclic AMP mediates the prostaglandin E2-induced potentiation of bradykinin excitation in rat sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 1995;2:459–466. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00567-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damas J, Bourdon V, Remacle-Volon G, Adam A. Kinins and peritoneal exudates induced by carrageenin and zymosan in rats. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1990;101:418–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AJ, Perkins MN. The involvement of bradykinin B1 and B2 receptor mechanisms in cytokine-induced mechanical hyperalgesia in the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;113:63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb16174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthrope MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A, Sheardown SA. Vanilloid receptor-1 is essential for inflammatory thermal hyperalgesia. Nature. 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster C, Handwerker HO. Automatic classification and analysis of microneurographic spike data using a PC/AT. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1990;31:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graness A, Adomeit A, Ludwig B, Muller WD, Kaufmann R, Liebmann C. Novel bradykinin signalling events in PC-12 cells: stimulation of the cAMP pathway leads to cAMP-mediated translocation of protein kinase C epsilon. Biochemical Journal. 1997;327:147–154. doi: 10.1042/bj3270147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake B, Liang Y-F, Reeh PW. Bradykinin effects and receptor subtypes in rat cutaneous nociceptors, in vitro. Pflügers Archiv. 1996;431(suppl):R15. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves KM, Troullos ES, Dionne RA, Schmidt EA, Schafer SC, Joris JL. Bradykinin is increased during acute and chronic inflammation: Therapeutic implications. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy. 1988;33:613–621. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1988.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker HO, Reeh PW. Pain and inflammation. In: Bond MR, Charlton JE, Woolf CJ, editors. Proceedings of the VIth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Haupt P, Jänig W, Kohler W. Response pattern of visceral afferent fibres supplying the colon upon chemical and mechanical stimuli. Pflügers Archiv. 1983;398:41–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00584711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaka R, Schaible HG, Schmidt RF. Activation of fine articular afferent units by bradykinin. Brain Research. 1985;327:81–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler W, Kirchhoff C, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Excitation of cutaneous afferent nerve endings in vitro by a combination of inflammatory mediators and conditioning effect of substance P. Experimental Brain Research. 1992;91:467–476. doi: 10.1007/BF00227842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Raja SN, Manning DC, Campbell JN, Meyer RA. The effects of bradykinin and sequence-related analogs on the response properties of cutaneous nociceptors in monkeys. Somatosensory and Motor Research. 1992;9:97–106. doi: 10.3109/08990229209144765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koltzenburg M, Kress M, Reeh PW. The nociceptor sensitization by bradykinin does not depend on sympathetic neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;46:465–473. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90066-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppert W, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Conditioning of histamine by bradykinin alters responses of rat nociceptor and human itch sensation. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;152:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90497-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Koltzenburg M, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Responsiveness and functional attributes of electrically localized terminals of cutaneous C-fibres in vivo and in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:581–595. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.2.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Roedl J, Reeh PW. Stable analogues of cyclic AMP but not GMP sensitize unmyelinated primary afferents in rat skin to heat stimulation but not to inflammatory mediators, in vitro. Neuroscience. 1996;74:609–617. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T, Mizumura K. Chemical response of polymodal receptors of the scrotal contents in dog. Journal of Physiology. 1980;299:219–232. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T, Mizumura K. Temperature dependency of the chemical responses of the polymodal receptor units in vitro. Brain Research. 1983;278:305–307. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T, Mizumura K, Minagawa M, Tsujii Y. Sensitizing effects of bradykinin on the heat responses of the visceral nociceptor. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1991;66:1819–1824. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.66.6.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T, Mizumura K, Sato J. Response properties of polymodal receptors studied using in vitro testis superior spermatic nerve preparations of dog. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1987;57:702–711. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.3.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang E, Novak A, Reeh PW, Handwerker HO. Chemosensitivity of fine afferents from rat skin in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;63:887–901. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng S, Mizumura K, Koda H, Kumazawa T. Excitation and sensitization of the heat response induced by a phorbol ester in canine visceral polymodal receptors studied in vitro. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;206:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JD, Taiwo YO, Collins SD, Tam JK. Noradrenaline hyperalgesia is mediated through interaction with sympathetic postganglionic neuron terminals rather than activation of primary afferent nociceptor. Nature. 1986;323:158–160. doi: 10.1038/323158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirk SM, Dolphin AC. G-protein mediation in nociceptive signal transduction: an investigation into the excitatory action of bradykinin in a subpopulation of cultured rat sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;49:117–128. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90079-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning DC, Srinivasa NR, Meyer RC, Campbell JN. Pain and hyperalgesia after intradermal injection of bradykinin in humans. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy. 1991;50:721–729. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1991.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumura K, Koda H, Kumazawa T. Augmenting effects of cyclic AMP on the heat response of canine testicular polymodal receptors. Neuroscience Letters. 1993;162:75–77. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90563-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumura K, Koda H, Kumazawa T. Evidence that protein kinase C activation is involved in the excitatory and facilitatory effects of bradykinin of canine visceral nociceptors in vitro. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;237:29–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00793-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumura K, Sato J, Kumazawa T. Strong heat stimulation sensitizes the heat response as well as the bradykinin response of visceral polymodal receptors. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:1209–1215. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer V, Schaible H-G, Schmidt RF. Sensitization of articular afferents to mechanical stimuli by bradykinin. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;415:330–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00370884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizard A, Blaukat A, Müller-Esterl W, Alhenc-Gelas F, Rajerison RM. Bradykinin-induced internalization of the human B2 receptor requires phosphorylation of three serine and two threonine residues at its carboxyl tail. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;18:12738–12747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeh PW. Sensory receptors in mammalian skin in an in vitro preparation. Neuroscience Letters. 1986;66:141–147. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeh PW. Chemical excitation and sensitization of nociceptors. In: Urban I, editor. Cellular Mechanisms of Sensory Processing. Heidelberg: Springer; 1994. pp. 119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Reeh PW, Kocher L, Jung S. Does neurogenic inflammation alter the sensitivity of unmyelinated nociceptors in the rat? Brain Research. 1986;384:42–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeh PW, Pethö G. Nociceptor excitation by thermal sensitization - a hypothesis. In: Sandkühler J, Bromm B, Gebhart GF, editors. Nervous System Plasticity and Chronic Pain. Vol. 129. Amsterdam: Progress in Brain Research, Elsevier; 2000. pp. 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeh PW, Sauer S. Chronic aspects in peripheral nociception. In: Jensen TS, Turner JA, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, editors. Proceedings of the 8th World Congress on Pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 1997. pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Schuligoi R, Donnerer J, Amann R. Bradykinin-induced sensitization of afferent neurons in the rat paw. Neuroscience. 1994;59:211–215. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steranka LR, Manning DC, Dehaas CJ, Ferkany JW, Borosky SA, Connor JR, Vavrek RJ, Stewart JM, Snyder SH. Bradykinin as a pain mediator: Receptors are localized to sensory neurons and antagonists have analgesic action. Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the USA. 1988;85:3245–3249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyklický V, Knotkova-Urbancova H, Vitaskowa Z, Vlachova V, Kress M, Reeh PW. Inflammatory mediators and acidic pH activate capsaicin receptors in cultured sensory neurons from newborn rats. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:670–676. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyklický V, Vlachová V, Vitásková Z, Dittert I, Kabát M, Orkand RK. Temperature coefficient of membrane currents induced by noxious heat in sensory neurones in the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:181–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0181z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]