Abstract

Located within the gastrointestinal (GI) musculature are networks of cells known as interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC). ICC are associated with several functions including pacemaker activity that generates electrical slow waves and neurotransmission regulating GI motility. In this study we identified a voltage-dependent K+ channel (Kv1.1) expressed in ICC and neurons but not in smooth muscle cells.

Transcriptional analyses demonstrated that Kv1.1 was expressed in whole tissue but not in isolated smooth muscle cells. Immunohistochemical co-localization of Kv1.1 with c-kit (a specific marker for ICC) and vimentin (a specific marker of neurons and ICC) indicated that Kv1.1-like immunoreactivity (Kv1.1-LI) was present in ICC and neurons of GI tissues of the dog, guinea-pig and mouse. Kv1.1-LI was not observed in smooth muscle cells of the circular and longitudinal muscle layers.

Kv1.1 was cloned from a canine colonic cDNA library and expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Pharmacological investigation of the electrophysiological properties of Kv1.1 demonstrated that the mamba snake toxin dendrotoxin-K (DTX-K) blocked the Kv1.1 outward current when expressed as a homotetrameric complex (EC50 = 0.34 nm). Other Kv channels were insensitive to DTX-K. When Kv1.1 was expressed as a heterotetrameric complex with Kv1.5, block by DTX-K dominated, indicating that one or more subunits of Kv1.1 rendered the heterotetrameric channel sensitive to DTX-K.

In patch-clamp experiments on cultured murine fundus ICC, DTX-K blocked a component of the delayed rectifier outward current. The remaining, DTX-insensitive current (i.e. current in the presence of 10−8m DTX-K) was outwardly rectifying, rapidly activating, non-inactivating during 500 ms step depolarizations, and could be blocked by both tetraethylammonium (TEA) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP).

In conclusion, Kv1.1 is expressed by ICC of several species. DTX-K is a specific blocker of Kv1.1 and heterotetrameric channels containing Kv1.1. This information is useful as a means of identifying ICC and in studies of the role of delayed rectifier K+ currents in ICC functions.

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) are specialized cells in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that are mesenchymal in origin and fundamental to the physiological functions of GI muscles (Huizinga et al. 1997; Sanders et al. 1999). ICC are present in all of the pacemaking regions of the GI tract, and they act to initiate slow waves that are propagated to the smooth muscle syncytium via gap junctions (see Horowitz et al. 1999 for review). ICC are also positioned between varicose nerve fibres and smooth muscle cells. In the murine fundus these ICC mediate neurotransmission by receiving and transducing neural inputs and conducting electrical responses to smooth muscle cells (Horowitz et al. 1999; Ward et al. 2000a). Given the specialized functions of ICC it can be hypothesized that these cells express electrical components (ion channels, receptors, signal transduction components) not present in smooth muscle cells (SMCs). We have begun to analyse the expression patterns of individual ICC representing classes of cells involved in pacemaking (IC-MY, ICC located at the myenteric border) and neurotransmission (IC-IM, ICC located in the intramuscular region) in the mouse by individually selecting cells based on labelling with c-kit antibody (Epperson et al. 2000). We have used this technology to detect ion channels that are expressed in ICC, but not in SMCs, with the goal of using pharmacological agents to selectively block these channels and determine their significance in ICC function.

Voltage-dependent K+ channels (Kv channels) participate in electrical rhythmicity and smooth muscle responses by contributing to the plateau potential of slow waves and action potentials (Koh et al. 1999b). Kv channels may also contribute to the repolarization phase of excitable events (Thornbury et al. 1992) and the resting potential between slow waves (Thornbury et al. 1992; Koh et al. 1999a). Kv channels also participate in the ICC and SMC responses to neural inputs because they are regulated by excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters (Vogalis et al. 1995; Shuttleworth et al. 1999). Therefore, differences in expression of Kv channels may distinguish between cells that drive electrical slow wave activity (IC-MY) or receive, conduct and transduce neural signals (IC-IM) and the SMCs, which respond to ICC activity and regulate L-type Ca2+ current and contraction.

In seminal studies on the cloning and characterization of Kv channel cDNA from canine colonic smooth muscles, two channels were predominantly expressed in smooth muscle, Kv1.2 and Kv1.5 (Hart et al. 1993; Overturf et al. 1994). However, during the cloning of these cDNAs, Kv1.1 was also recovered from the same cDNA library, which was constructed with RNA derived from bulk circular smooth muscle (Adlish et al. 1991). Since this clone was not expressed in smooth muscle cells (Adlish et al. 1991), it was assumed that Kv1.1 was recovered from the neuronal cells within the tissue preparation. Using a technique to select and analyse individual ICC (Epperson et al. 2000) and antibodies specific for Kv1.1 (Bekele-Arcuri et al. 1996), we have determined that Kv1.1 is localized to IC-MY and IC-IM in several species. We have also determined that DTX-K, a specific blocker of Kv1.1 channels (Robertson et al. 1996), blocks heterotetramers containing Kv1.1. Finally, while DTX-K has no effect on delayed rectifier current in native SMCs, it blocks a significant component of current in acutely cultured ICC.

A portion of this work has been presented at the Biophysical Society meeting (Hatton et al. 2000).

METHODS

The Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Nevada approved the use and treatment of all animals used in the experiments described here.

Identification of acutely dispersed IC-IM from the murine fundus

BALB/c mice (20-30 days old, Harlan Sprague Dawley; Indianapolis, IN, USA) were anaesthetized by chloroform inhalation and decapitated following cervical dislocation. Immunohistochemistry and isolation of acutely dispersed cells was carried out as described previously (Epperson et al. 2000). Smooth muscle cell preparations included approximately 50 cells. Three independent preparations of ICC and SMCs were examined. Immunohistochemical localization of Kv1.1 was carried out as described for whole mount sections. Phase and fluorescence photomicrographs were taken using a Nikon Eclipse TE 200 inverted microscope.

Immunohistochemistry in whole mount preparations from several species

Guinea-pigs, weighing 250-350 g, and Balb/c mice (9-15 days old) were killed by asphyxia with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. The abdomens were cut open and the small intestine and colon removed and placed in cold Krebs-Ringer-bicarbonate solution (KRB) for dissection.

The fundus and proximal colon were opened along the mesenteric border and the lumenal contents flushed away with cold KRB. The opened segments were pinned mucosa side up onto a Sylgard-coated dish. The mucosa and submucosa were removed by sharp dissection leaving the muscularis externa. The muscularis was relaxed in KRB containing nifedipine (10−6m, Sigma) for 30 min, then stretched to 150 % of resting length and fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for 20 min at 4 oC. Following fixation, tissues were washed in PBS (4 × 30 min) and non-specific antibody binding was reduced by blocking with 10 % bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS containing 0.03 % Triton X-100 for 1 h and then incubated with a monoclonal anti-c-Kit protein raised in rat (ACK2, 5 μg ml−1; Gibco/BRL) for 48 h at 4 oC. Tissues were then washed with PBS (2 × 10 min) and incubated in Alexa 594 (red fluorescence)-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) at 5 μg ml−1. Secondary incubations were performed for 1 h at room temperature. Following secondary incubation, tissues were washed in PBS (3 × 15 min), and then incubated in the second primary antibody (monoclonal anti-Kv1.1 raised in mouse) at a dilution of 1 μg ml−1 overnight at room temperature. The following day tissues were washed with PBS (2 × 10 min) and incubated in biotinylated secondary goat anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), at 5 μg ml−1. Secondary incubation was for 1 h at room temperature and tissues were washed with PBS (2 × 10 min). Tissues were then incubated in streptavidin-conjugated Alexa 488 (green fluorescence) in the same way as for the secondary antibody. Preparations were then washed (3 × 15 min PBS), and mounted on vectabond-coated microscope slides. When mouse monoclonal anti-Kv1.1 was used in mouse tissue, Vector Laboratories mouse-on-mouse detection kit (MOM) was incorporated to minimize non-specific binding to endogenous mouse IgG; the kit was used as per manufacturers instructions. Control tissues for double-labelling immunohistochemistry were prepared by omitting the first primary antibody in one preparation, the second primary antibody in a second preparation and both antibodies in a third preparation. PBS was substituted when an antibody or antibodies were omitted. Tissues were examined using a Bio-Rad MRC 600 confocal microscope with excitation wavelengths appropriate for Alexa 488 (488 nm) and Alexa 594 (594 nm). Confocal micrographs were obtained from digital composites of two-serial scans of optical sections (Z). The depth of optical sections depended upon the tissue and the species. Z-series were constructed with Bio-Rad ‘Comos’ software and final images were prepared using Adobe Photoshop software.

Immunohistochemistry in cryostat sections

Segments of canine and proximal colon were used for cryostat sectioning. Gross preparation of tissues was carried out as described above. The mucosa and submucosa were not removed and fixation was extended to 45 min at 4 oC. Following fixation the tissue was cut both longitudinally and transversely into 0.5 cm strips and washed in PBS (4 × 15 min). Tissue strips were then cryoprotected in a graded series of sucrose solutions (5, 10 and 15 % (w/v) made up in PBS for 1 h each and overnight in 20 %). Tissue strips were then embedded in Tissue Tek‘ embedding medium (Miles, Lake Zurich, IL, USA) and 20 % sucrose in PBS (1 : 2 v/v) and rapidly frozen in isopentane pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Cryosections were cut using a Leica CM 3500 cryostat at a thickness of 8 μm and collected on Vectabond’ (Vector Laboratories)-coated microscope slides. Double-labelling immunohistochemistry was carried out on the sections, basically as described for whole mount tissue preparations.

RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was prepared from isolated cells as described previously (Epperson et al. 2000). Briefly the SNAP Total RNA isolation kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) was used as per the manufacturer's instructions. First strand cDNA was prepared from the RNA preparations using the Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase kit (Gibco/BRL); 100 μg of oligo dT primers were used to reverse transcribe the RNA sample. PCR was performed in a 25 μl reaction using the following cycling parameters: 94oC for 10 min and 40 cycles of 94 oC for 15 s followed by 60 oC for 1 min. The amplified products (10 μl) were separated by electrophoresis on 2 % (β-actin and Kv1.1) and 4 % (c-Kit) agarose/1X TAE (Tris, acetic acid, EDTA) gel, and the DNA bands were visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

The following PCR primers were used (numbers in parentheses are the GenBank accession numbers; the first range of numbers represents the sense bordering nucleotide positions and the second range of numbers is the antisense bordering nucleotide positions): β-actin (V01217) (with intronic sequence) nucleotides (nt) 2383-2402 and 3071-3091; Kv1.1 (NM-010595) nt 1598-1619 and 1694-1714; c-kit (X06182) nt 1897-1919 and 1987-2001.

In all cDNA preparations, specific primers for β-actin were used as a positive control to ensure that each sample was not contaminated with genomic DNA. Primers were designed to span a region of the β-actin that encoded an intron. Thus if DNA was contaminating the sample a 708 bp PCR product would be detected.

Heterologous expression and assay of Kv channel currents

Stage V and VI Xenopus oocytes were collected (under anaesthesia from frogs that were humanely killed after the final collection), injected with mRNA encoding selected Kv channels, and incubated as described previously (Hart et al. 1993; Overturf et al. 1994). We injected either 50 nl of 1 μg μl−1 of cRNA encoding Kv1.1 or 50 nl of 3.5 ng μl−1 of cRNA encoding Kv1.5, or we co-injected 25 nl of both cRNA solutions. We identified donor frogs whose oocytes expressed between 1 and 5 μA of Kv currents and used these oocytes to study the sensitivities of homotetrameric and heterotetrameric Kv channels to dendrotoxin-K. The observation of similar current amplitudes suggests that the co-injections resulted in the expression of equal numbers of Kv1.1 and Kv1.5 subunits in these oocytes.

Whole-cell potassium currents from oocytes were recorded using the two-microelectrode voltage-clamp technique as described previously (Hart et al. 1993). Briefly, microelectrodes were filled with 3 m KCl (resistances between 1 and 3 MΩ) and oocytes were superfused with a solution containing (mm): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 2. 8 MgCl2, 5 Hepes (pH = 7.4). Linear leak and capacitance currents were removed from the recorded currents by applying five hyperpolarizations of one-fifth of the test amplitude, summing the resulting currents, and adding the result to the current elicited by the test pulse (i.e. a -P/5 protocol). Stock solutions of tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA, 1 m, Sigma), 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 0.1 m, Sigma) and dendrotoxin-K (DTX-K, 100 μm, Calbiochem) were prepared in distilled water. Immediately prior to use, stock solutions were diluted to the desired concentration in the superfusate. Each experiment was performed at room temperature (24-28 °C) on oocytes collected from more than one frog.

Identification of cultured ICC

The appearance of murine ICC and ICC networks is distinct from other cell types in these cultures as described previously (Koh et al. 1998). Only cells with a ‘bipolar’ appearance featuring a central ovoid cell body and two long and thin processes extending in either direction were included in this study. Cells with multiple processes or elongated cell bodies were excluded. Therefore, it was possible to select cells for electrophysiological experiments by phase contrast microscopy.

Culture of ICC

Small pieces of antrum muscle were equilibrated in Ca2+-free Hank's solution for 30 min. The buffer was replaced with an enzyme solution containing: 1.3 mg ml−1 collagenase (Worthington type II), 2 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (Sigma), 2 mg ml−1 trypsin inhibitor (Sigma), and 0.27 mg ml−1 ATP. The tissues were placed in a 37 oC water bath for 25 min without agitation. After 3-4 washes with Ca2+-free Hanks solution to remove the enzyme, the tissues were triturated through a series of three blunt pipettes of decreasing tip diameter. The resulting cell suspension was plated onto murine collagen (2.5 μg ml−1, Falcon/BD)-coated sterile glass coverslips, in 35 mm culture dishes. The cells were allowed to settle for 10 min before adding culture medium. The culture medium used was SMGM (Clonetics Corp., San Diego CA, USA) supplemented with 2 % antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco) and murine stem cell factor (SCF, 5 ng ml−1, Sigma). The cells were incubated at 37 oC in a 95 % O2-5 % CO2 incubator. The medium was changed after 24 h to SMGM containing SCF without antibiotics or antimycotics, and then the medium was changed every other day until the cells were used for electrophysiological experiments. Experiments were performed after 3-7 days of culture.

Electrophysiological methods

The whole-cell patch-clamp technique was used to record currents from cultured ICC. Currents were recorded with an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) and digitized with a 12 bit A/D converter (TL-1, DMA interface, Axon Instruments). Currents were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized online using pCLAMP 6.0 software (Axon Instruments). Cultured cells were bathed in a solution containing (mm): 5 KCl, 135 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris. The pipette solution contained (mm): 110 potassium gluconate, 20 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 2.7 K2ATP, 0.1 Na2GTP, 2.5 disodium creatine phosphate, 5 Hepes, 0.1 EGTA, adjusted to pH 7.2 with Tris. All experiments were performed at room temperature (24-28 oC).

Data analysis

Results were analysed using pCLAMP 6.0 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 5.0 (Microcal, Northampton, MA, USA) or Prizm 2.01(GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) software. Data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. Differences in the data were evaluated by Student's t test and P values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. The n values reported in the text refer to the number of oocytes or cells used in electrophysiological experiments.

RESULTS

Expression of Kv1.1 in isolated IC-IM from murine fundus

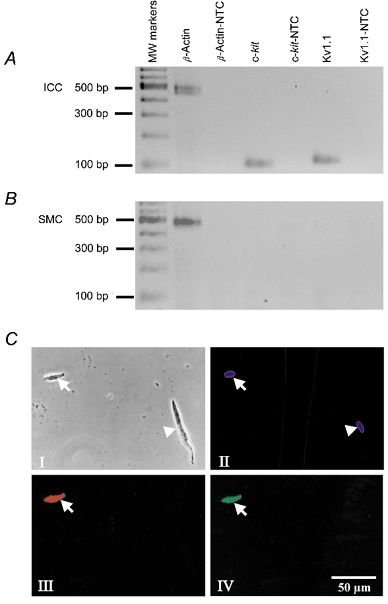

RT-PCR of total RNA isolated from individual IC-IM from the murine fundus were positive for c-kit expression and Kv1.1 (Fig. 1a), while SMC RNA preparations were negative for both amplicons (Fig. 1B). Three independently prepared ICC showed identical results. The SMC preparations were made from 50 selected cells in each preparation as described previously (Epperson et al. 2000). Three independently isolated preparations of SMCs showed identical results. No-template control (NTC) checks for primer contamination were made. Figure 1C displays the co-localization of c-kit and Kv1.1 immunoreactivity in acutely dispersed cells. Panel I is a nuclear stain showing viable cells. Panel II shows an isolated IC-MY cell in the same field as a SMC. ICC were immunopositive for both c-kit (panel III) and Kv1.1 (panel IV) antibodies. Neither antibody stained the SMC.

Figure 1. Transcriptional expression of Kv1.1 in isolated smooth muscle cells of murine fundus and isolated murine fundus IC-IM.

Phase and fluorescence photomicrographs of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI in isolated murine fundus cells. RNA was prepared from isolated ICC. A, freshly dispersed murine fundus IC-IM. B, freshly dispersed murine fundus myocytes. c-kit and Kv1.1 were expressed in ICC but not in SMCs. Kv1.1 expression in ICC was confirmed at the protein level. C, phase contrast and fluorescence photomicrographs of a freshly dispersed ICC and a smooth muscle cell isolated from murine fundus. Panel I, a phase contrast photomicrograph of an ICC (arrow) and a smooth muscle cell (arrowhead). Panel II, photomicrograph of Hoechst 33342 fluorescence (blue) showing viable nuclei in both the ICC (arrow) and the smooth muscle cell (arrowhead). Panel III, photomicrograph of c-Kit-LI fluoresecence (red) in the ICC (arrow) but not in the smooth muscle cell. Panel IV, photomicrograph of Kv1.1-LI fluorescence (green) in the ICC (arrow) but not in the smooth muscle cell.

Immunohistochemical localization of Kv1.1 in GI tissues

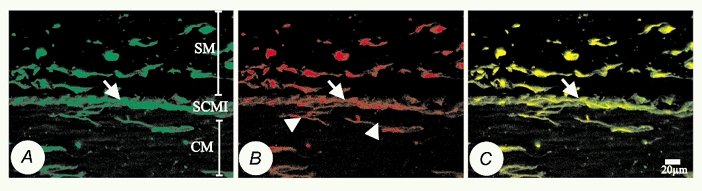

Initial immunohistochemical staining in cryosections (8 μm) of canine proximal colon demonstrated Kv1.1-like immunoreactivity (Kv1.1-LI) within a subgroup of cells of the muscularis externa. The position and morphology of these cells were indicative of two cell types, ICC and enteric neurons (Ward & Sanders, 1990) (Fig. 2a). Immunoreactivity was not observed in smooth muscle cells. When an antibody against vimentin (strongly expressed in ICC; Wang et al. 1999) was used (Fig. 2B), double labelling revealed Kv1.1-LI and vimentin-like immunoreactivity (vimentin-LI) co-localized in ICC (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Confocal micrographs of 8 μm cryosections, showing double labelling with Kv1.1 (FITC) and vimentin (Texas red) antibodies at the submucosal-circular muscle interface (SCMI) of canine proximal colon.

A, Kv1.1-like immunoreactivity (Kv1.1-LI, green), showing intense staining (arrow) at the submucosal-circular muscle interface (SCMI) between the circular muscularis (CM) and submucosa (SM). A network of ICC is found at this level and is positive for Kv1.1. B, vimentin-like immunoreactivity (vimentin-LI, red) of the same specimen, showing labelling of ICC in the SCMI and neurons (arrowheads) in the circular muscularis. C, co-localization (yellow) of Kv1.1-LI and vimentin-LI. Negative controls where primary antibodies were omitted showed no staining.

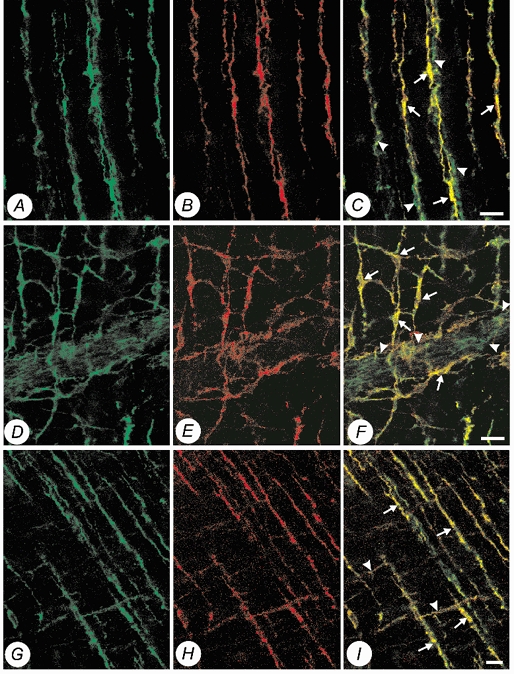

Double labelling with antibodies for Kv1.1 and c-Kit in whole mount tissue sections of guinea-pig proximal colon showed co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI in intra-muscular ICC (IC-IM) which run parallel to the long axis of muscle fibres. IC-IM are located in close apposition to varicose nerve fibres within the circular muscle layer (Fig. 3a–C). The varicose nerve fibres also exhibited Kv1.1-LI, but these structures did not display c-Kit-LI. c-Kit-LI and Kv1.1-LI were also present in IC-MY, which are located at the level of the myenteric plexus between the circular and longitudinal muscle layers. IC-MY are closely associated with ganglia and nerve fibres of the myenteric plexus. Kv1.1-LI, but not c-Kit-LI, was observed in neurons within the myenteric ganglia (Fig. 3D–F).

Figure 3. Confocal micrographs of whole mount preparations of guinea-pig proximal colon and gastric fundus, showing double labelling of Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) and c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) within the muscularis externa.

A, Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) within the circular muscularis of the proximal colon. B, c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) within the circular muscularis of the same specimen. C, co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI (yellow) showing that intramuscular ICC (arrows) and juxtaposed varicose nerve fibres (arrowheads) express Kv1.1. D, Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) at the level of the myenteric plexus. E, c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) at the level of the myenteric plexus in the same specimen. F, co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI (yellow) showing that both the cell bodies (arrows) and intricate processes of myenteric ICC are immunopositive for Kv1.1. Note also myenteric ganglia (arrowheads) are also immunopositive for Kv1.1. G, Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) within the circular and longitudinal muscularis of the gastric fundus. H, c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) within the circular and longitudinal muscularis of the gastric fundus of the same specimen. I, co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI (yellow), showing that intramuscular ICC in both the longitudinal muscularis (arrowheads) and circular muscularis (arrows) are immunopositive for Kv1.1. (Scale bars, 20 μm.)

Double labelling for Kv1.1 and c-Kit in whole mount tissue sections of guinea-pig gastric fundus showed co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI in IC-IM of both the longitudinal and circular muscle layers (Fig. 3G–I). Similar to the expression pattern in guinea-pig colon, Kv1.1-LI, but not c-Kit-LI, was observed in myenteric neurons.

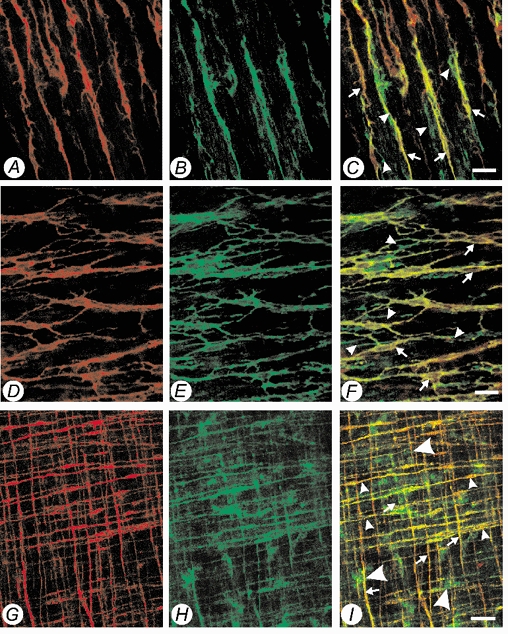

Double-labelling experiments of murine proximal colon (Fig. 4A–C), jejunum (Fig. 4D–F), and gastric fundus (Fig. 4G–I) showed expression patterns for c-Kit and Kv1.1 similar to the guinea-pig.

Figure 4. Confocal micrographs of whole mount preparations of murine proximal colon and gastric fundus, showing double labelling of Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) and c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) within the muscularis externa.

A, c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) within the circular muscularis at the level of the sub-mucosal border of the proximal colon. B, Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) within the circular muscularis at the level of the sub-mucosal border of the proximal colon of the same specimen. C, co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI (yellow) showing that intramuscular ICC (arrows) and juxtaposed varicose nerve fibres (arrowheads) express Kv1.1. D, c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) at the level of the myenteric plexus. E, Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) at the level of the myenteric plexus of the same specimen. F, co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI (yellow) showing that both the cell bodies (arrows) and intricate processes of myenteric ICC are immunopositive, note also myenteric ganglia (arrowheads) and neuronal processes are also immunopositive for Kv1.1. G, c-Kit-LI (Alexa 594, red) within the circular and longitudinal muscularis of the gastric fundus. H, Kv1.1-LI (Alexa 488, green) within the circular and longitudinal muscularis of the gastric fundus of the same specimen. I, co-localization of Kv1.1-LI and c-Kit-LI (yellow). Intramuscular ICC in both the longitudinal muscularis (arrows) and circular muscularis (arrowheads) are immunopositive for Kv1.1. Myenteric ganglia are also immunopositive for Kv1.1 but not for c-Kit (large arrowheads). (Scale bars: A–F, 20 μm; G–I, 50 μm.)

Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of Kv1.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes

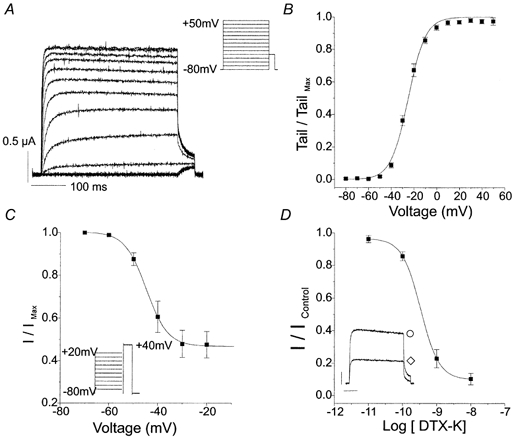

The day following injection of mRNA encoding canine Kv1.1 into Xenopus oocytes, large currents could be elicited upon step depolarizations from -80 mV. These currents were not observed in oocytes injected with water. Figure 5a shows typical outward currents evoked by 400 ms voltage steps from a holding potential of -80 mV to test potentials ranging from -80 mV to +50 mV. Currents were activated at test potentials positive to -40 mV and showed rapid activation and little inactivation during 400 ms pulses. The time to half-activation was voltage dependent, decreasing with stronger depolarizations. The voltage dependence of the activation of the conductance mediated by expression of canine Kv1.1 was determined by measuring the amplitude of the currents immediately after repolarization to -40 mV. The normalized amplitudes as a function of conditioning potential were fitted to a Boltzmann function. As shown in Fig. 5B, the average half-maximal activation (V1/2) was -25 ± 0.5 mV (n = 5) and the slope factor (k) was 7.7 ± 0.5 mV (n = 5). Although the currents mediated by canine Kv1.1 showed little or no inactivation during short depolarizations, 15.5 s steps inactivated about half of the current. The voltage dependence of inactivation of the Kv1.1 current during 15.5 s conditioning pulses is shown in Fig. 5C. Currents elicited by the +40 mV test potential were normalized to currents following the -70 mV conditioning pulse and plotted as a function of the conditioning potential. In six oocytes, the V1/2 was -44.8 ± 0.3 mV and k was 4.4 ± 0.2 mV.

Figure 5. Characterization of Kv1.1 cloned from canine colon tissue.

A, representative currents recorded from an oocyte injected with cRNA encoding Kv1.1. Currents were evoked by 400 ms voltage steps from a holding potential of -80 mV to test potentials ranging from -80 to +50 mV, followed by a step to -40 mV to measure tail currents. B, normalized Kv1.1 tail currents at -40 mV following 400 ms step to test potentials ranging from -80 to +50 mV were fitted with a Boltzmann function (V1/2= -25.0 mV, k = 7.7 mV, n = 5). C, voltage dependence of inactivation of Kv1.1 current was measured using 15.5 s conditioning pulses from -70 to +20 mV followed by a step to +40 mV. Normalized test currents were plotted as a function of conditioning pulse potential and fitted with a Boltzmann function (V1/2= -44.8 mV, k = 4.4 mV, n = 6). D, dose-response relationship for DTX-K was plotted at steady-state block. The IC50 was 0.34 nm for DTX-K (n = 5). The inset shows illustrative Kv1.1 currents evoked by 400 ms voltage steps from a holding potential of -80 mV to 0 mV in the absence (○) and presence (⋄) of 1 nm DTX-K.

We examined the sensitivity of canine Kv1.1 current to TEA and 4-AP, non-specific inhibitors of K+ channels, and to dendrotoxin-K (DTX-K), a component of mamba venom selective for Kv1.1 (Robertson et al. 1996). The steady-state response was measured as the late current during a 400 ms voltage step from a holding potential of -80 mV to 0 mV. TEA blocked Kv1.1 current with an IC50 of 0.20 ± 0.1 mm (n = 4). 4-AP blocked Kv1.1 current with an IC50 of 74.2 ± 0.1 μm (n = 4). Figure 5D shows whole-cell Kv1.1 current and the dose-response relationship for DTX-K (n = 5). DTX-K blocked Kv1.1 current in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 0.34 ± 0.01 nm. The inhibition by DTX-K was irreversible, even on prolonged washing. The Hill co-efficient values were 0.9 for TEA, 1.3 for 4-AP and 1.2 for DTX-K.

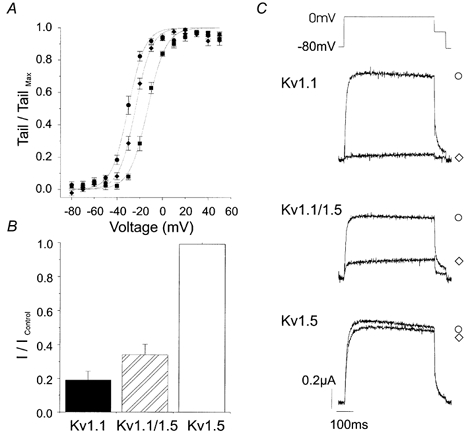

Thus, we confirm previously published observations of the sensitivity of Kv1.1 channels to DTX-K (Robertson et al. 1996). However, delayed rectifier currents in native cells can be mediated by heterotetramers made up of different Kvα subunits (Scott et al. 1994). Accordingly, we wished to establish the sensitivity of heterotetrameric channels containing Kv1.1 subunits to DTX-K. We did this by injecting oocytes with cRNA encoding Kv1.1 alone, a different Kvα subunit (Kv1.5), or both Kv1.1 and Kv1.5. Kv currents recorded from oocytes injected with Kv1.1 or Kv1.5, or co-injected with Kv1.1 and Kv1.5 showed different voltage-dependent activation (Fig. 6a). The V1/2 values were -30.3 ± 0.3 mV for Kv1.1, -13.1 ± 0.3 mV for Kv1.5 and -23.9 ± 0.3 mV for coinjections of Kv1.1 plus Kv1.5 (n = 6 for each). The V1/2 for Kv1.5 was significantly different from that for Kv1.1 or the coinjected subunits (P < 0.05, ANOVA). The k values were not significantly different.

Figure 6. Sensitivity of homo- and heterotetramers of Kv1.1 and Kv1.5 to DTX-K.

Oocytes were injected with mRNA encoding Kv1.1 alone, Kv1.5 alone, or both Kv1.1 and Kv1.5 cRNA. A, voltage dependence of activation of Kv1.1 alone (•), Kv1.5 alone (▪) and co-injected Kv1.1 plus Kv1.5 (♦) currents. Normalized Kv1.1 tail currents were fitted with a Boltzmann function. The V1/2 and k values were, respectively, -30.3 mV and 7.4 mV for Kv1.1 (n = 6), -13.1 mV and 8.0 mV for Kv1.5 (n = 6), -23.9 mV and 7.1 mV for co-injected Kv1.1 plus Kv1.5 (n = 6). B, the steady-state response of homo- and heterotetramers of Kv1.1 and Kv1.5 to 1 nm DTX-K was measured as the late current during a 400 ms voltage step from a holding potential of -80 mV to 0 mV. DTX-K inhibited currents encoded by Kv1.1 alone (80 ± 6 %, n = 5), and co-injected Kv1.1 plus Kv1.5 (68 ± 6 %, n = 5), but not Kv1.5 alone (3 ± 1 %, n = 4). C, illustrative currents in the absence (○) and presence (⋄) of 1 nm DTX-K.

The sensitivity of homo- and heterotetramers of Kv1.1 and Kv1.5 to 1 nm DTX-K is shown in Fig. 6B, with illustrative currents shown in Fig. 6C. The steady-state response was measured as the late current during a 400 ms voltage step from a holding potential of -80 mV to 0 mV. In this series of experiments, DTX-K inhibited 80 ± 6 % of the current encoded by Kv1.1 alone (n = 5). In contrast, 1 nm DTX-K had no significant effect on currents mediated by Kv1.5 alone (3 ± 1 %, P > 0.05, n = 4), similar to previously published evidence for the specificity of this toxin for Kv1.1 channels. In oocytes injected with cRNA encoding both Kv1.1 and Kv1.5, if the subunits are expressed equally and if they assemble randomly into tetramers, 0.063 of the channels will be homotetramers of Kv1.1 with the remaining channels containing from one to four Kv1.5 subunits. Thus, if only the Kv1.1 homotetramers are sensitive to DTX-K, one expects that the current in these oocytes will be reduced by 81 % of 0.063, i.e. ≈5 % of control (Russell et al. 1994). However, as seen in Fig. 6B, the current in co-injected oocytes was reduced by 68 ± 6 % of control (n = 5), indicating that heterotetramers containing Kv1.1 plus Kv1.5 subunits are blocked by DTX-K.

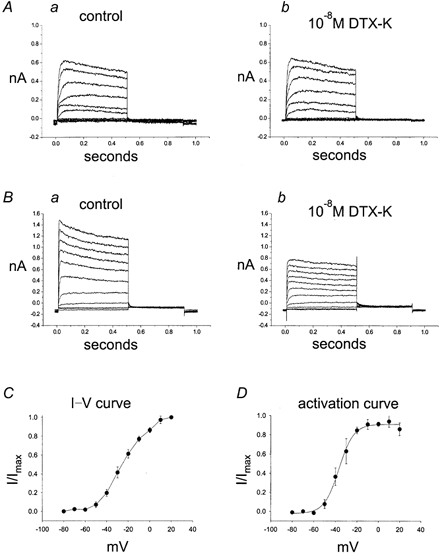

Electrophysiological recordings from cultured ICC-like cells demonstrate block of a component of delayed rectifier current by DTX-K

Mouse fundus ICC-like cells were chosen according to morphological criteria described in the Methods after 2-7 days of culture. Fast-activating, slowly inactivating, outwardly rectifying K+ current was observed in 12 of 31 cells and the peak amplitude ranged from 0.9 to 5.4 nA at +20 mV in physiological salt solution. Application of 10−8m DTX-K blocked 45-90 % of this current, while outward currents from SMCs were never blocked by DTX-K (i.e. at 0 mV, control current was 732 ± 10 pA and current in DTX-K was 708 ± 28 pA; n = 3). We noted that expression of DTX-K-sensitive current in ICC was variable. In 2- to 4-day cultures 3 of 21 cells displayed DTX-K-sensitive current, while in 5- to 7-day cultures 9 of 10 cells showed DTX-K-sensitive current (Fig. 7A–B). I-V relationships and activation kinetics were investigated in more detail in 6 of these 12 cells in which DTX-K-sensitive currents were recorded. On average, DTX-K blocked 62 ± 5 % of peak current and 40 ± 6 % of current at the end of a 500 ms step depolarization to +20 mV (n = 6 cells). The I-V and activation curves of the DTX-sensitive current (current under control conditions minus current in presence of 10−8m DTX-K) averaged from six cells are shown in Fig. 7C and D. Activation curves were obtained from tail currents measured immediately after repolarization to -60 mV and fitted with a Boltzman function (V1/2= -36.8 mV, k = 6.8 mV). These data are similar to the properties of Kv1.1 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes.

Figure 7. DTX-K-sensitive outward current in cultured ICC-like cells from mouse fundus.

Outward current was elicited by step depolarizations from -80 to +20 mV from a holding potential of -80 mV. Tail currents were recorded at -60 mV. A, recording from a 4-day cultured ICC-like cell that did not display DTX-K-sensitive current. B, recording from a 4-day cultured ICC-like cell that expressed DTX-K-sensitive current. Note that currents under control conditions in A activate more slowly than currents under control conditions in B. The I-V relationships and kinetics of the DTX-sensitive component were obtained by subtracting current in presence of 10−8m DTX-K from current under control conditions. C, I–V relationship of the DTX-sensitive difference current (b – a), normalized to maximum current at +20 mV. D, activation curve obtained from tail currents of the DTX-sensitive difference current (b – a). Data are averaged from 6 cells.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study were: (1) ICC express Kv1.1 and SMCs do not, (2) DTX-K block dominates in heterotetramers containing Kv1.1, and (3) DTX-K blocks a component of delayed rectifier current in ICC but not in SMCs. These findings suggest that Kv1.1 is a component of delayed rectifier current in ICC, and expression of this current can differentiate between ICC and SMCs.

Relatively little has been reported about the ionic conductances expressed by ICC, in contrast to a large body of information available about ionic channels in GI SMCs (see Farrugia, 1999, for review). Initial studies on isolated ICC used morphology as the main criterion to identify the cells (Langton et al. 1989). ICC identified from the canine colon pacemaker region displayed some electrophysiological differences compared with SMCs dispersed from the same region (Lee & Sanders, 1993). For example, 4-aminopyridine-sensitive K+ currents were recorded from both cell types but half-inactivation was 25 mV more negative in ICC. More recently, ICC dispersed from the murine small intestine have been cultured for several days and then recorded from with patch electrodes (Koh et al. 1998; Thomsen et al. 1998). The cells remain rhythmic in culture, although some changes in contractile phenotype occur (Epperson et al. 2000). Spontaneous electrical activity of these cells was unaffected by L-type Ca2+ channel blockers but was inhibited by blockers of non-selective cation channels (Koh et al. 1998).

Lee et al. (1999) reported that whole-cell outward currents of cultured ICC from the murine small intestine are rapidly activating and slowly inactivating. In contrast, SMCs from the same region of the small bowel had a distinct transient component to the outward current. Outward currents recorded from small intestinal ICC were tetraethylammonium insensitive (5 mm) and displayed half-activation at -8.7 mV (Lee et al. 1999). Kv1.1 is sensitive to TEA (IC50= 0.2 mm), and the half-activation of this conductance occurs at about -25 mV. Thus it is unlikely that the presence of Kv1.1 was detected in cells from the small intestine. ICC from the small intestine were likely to be IC-MY because they were rhythmically active (Lee et al. 1999), but the cells examined in this report (see Fig. 7) were c-Kit-positive cells from the murine fundus, which lack IC-MY. Therefore, these cells were likely to be IC-IM because this is the only species of ICC found in the murine fundus (Burns et al. 1996). Outward currents of fundus ICC displayed a distinct component that was blocked by DTX-K and was TEA sensitive (5 mm). However, we also found that Kv1.1 is expressed in IC-MY of the small intestine in situ (see Figs 2–4). A contribution from this current may have been missed in the previous study of ICC from the small bowel (Lee et al. 1999).

Although the immunofluorescence studies suggested significant expression of Kv1.1 protein in ICC, we noted considerable variability in the expression of outward current properties in cultured IC-IM. Changes in gene expression during the culture of these cells have been previously documented (Epperson et al. 2000), and it is possible that cells in culture recover slowly from down-regulation of Kv1.1 as a result of cell dispersion. While cultured ICC appear to be a highly effective model for studying electrical rhythmicity (Ward et al. 2000b), some caution is needed and comparative studies must be used when attempting to relate the function of these cells to native ICC. Since this is the first study of IC-IM to date, the information gained about expression of Kv1.1 as a function of time in culture may be an effective means of electrically screening for IC-IM. In the future it may become possible to perform studies on freshly dispersed IC-IM to test whether the majority of cells express resolvable currents consistent with the widespread expression of Kv1.1. If that result occurs, the use of Kv1.1 (i.e. the presence of a DTX-K-sensitive outward current) could become a recognized electrophysiological signature for ICC.

The activation and inactivation parameters of canine Kv1.1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes are similar to those previously reported for rat, mouse and human Kv1.1 expressed in oocytes and mammalian cells (Stuhmer et al. 1989; Bosma et al. 1993). The IC50 value for TEA of canine Kv1.1 (0.2 mm) is close to the reported range for rat and mouse Kv1.1 (0.4-0.8 mm; Stuhmer et al. 1989; Bosma et al. 1993). The sensitivity of canine Kv1.1 to 4-AP (74.2 μm) is higher than that of rat and mouse Kv1.1. However, the reported range of IC50 values for 4-AP is highly variable, ranging from 89 μm to 1 mm (Stuhmer et al. 1989; Christie et al. 1989; Bosma et al. 1993; Castle et al. 1994). The IC50 value for DTX-K (0.34 nm) on canine Kv1.1 expressed in oocytes is also within the reported range (0.03-2.5 nm; Robertson et al. 1996; Owen et al. 1997).

Currents due to Kv channels appear to affect electrical activity in GI muscles by contributing to membrane potential and regulating the plateau phase of slow waves (Horowitz et al. 1999). Future experiments using DTX-K in experiments on intact muscles during intracellular electrical recording may help to illustrate how a specific component of Kv expressed by ICC (i.e. Kv1.1) might contribute to the electrical behaviour of the ICC-smooth muscle syncytium. The role of Kv1.1 expressed in IC-IM is more difficult to assess. IC-IM are involved in motor neurotransmission in GI muscles (Burns et al. 1996; Ward et al. 2000a). Kv1.1 is expressed both in IC-IM and in motor neurons according to our immunohistochemical studies. Therefore, it is difficult to know whether effects of DTX-K are due to pre- or post-junctional responses or both. Blocking Kv1.1 in the guinea-pig ileum enhanced acetylcholine release and increased contractions of smooth muscle (Suarez-Kurtz et al. 1999). Studies of Kv1.1 knock-out mice, particularly mice with cell-specific knock-outs of Kv1.1 would be useful for future functional analysis of the role of Kv1.1.

In conclusion, ICC are important cells in normal GI motility. Identification, at a molecular level, of individual components responsible for ICC function will enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of GI motility. Discovery of reagents to detect ICC (e.g. antibodies) or to modulate ICC function (e.g. pharmacological agonists or antagonists) will facilitate investigation of the role of ICC in GI motility and perhaps provide new ideas for therapies for GI motor dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIDDK program project grant DK41315. H.M. is a postdoctoral fellow of the American Heart Association, Western States Affiliate.

William J. Hatton and Helen S. Mason contributed equally to this work.

References

- Adlish JD, Overturf KO, Hart P, Duval D, Sanders KM, Horowitz B. Molecular cloning and differential expression of potassium and calcium channels expressed in canine colonic circular muscles. Biophysical Journal. 1991;59:454a. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele-Arcuri Z, Matos MF, Manganas L, Strassle BW, Monaghan MM, Rhodes KJ, Trimmer JS. Generation and characterization of subtype-specific monoclonal antibodies to K+ channel alpha- and beta-subunit polypeptides. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:851–865. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosma MM, Allen ML, Martin TM, Tempel BL. PKA-dependent regulation of mKv1. 1, a mouse Shaker-like potassium channel gene, when stably expressed in CHO cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:5242–5250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05242.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns AJ, Lomax AEJ, Torihashi S, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate inhibitory neurotransmission in the stomach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:12008–12013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NA, Fadous SR, Logothetis DE, Wang GK. 4-Aminopyridine binding and slow inactivation are mutually exclusive in rat Kv1. 1 and Shaker potassium channels. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;46:1175–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ, Adelman JP, Douglass J, North RA. Expression of a cloned rat brain potassium channel in Xenopus oocytes. Science. 1989;244:221–224. doi: 10.1126/science.2539643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperson A, Hatton WJ, Callaghan B, Doherty P, Walker RL, Sanders KM, Ward SM, Horowitz B. Molecular markers expressed in cultured and freshly isolated interstitial cells of cajal. American Journal of Physiology: Cell Physiology. 2000;279:C529–539. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.2.C529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia G. Ionic conductances in gastrointestinal smooth muscles and interstitial cells of Cajal. Annual Reviews in Physiology. 1999;61:45–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart PJ, Overturf KE, Russell SN, Carl A, Hume JR, Sanders KM, Horowitz B. Cloning and expression of a Kv1. 2 class delayed rectifier K+ channel from canine colonic smooth muscle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1993;90:9659–9663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton WJ, Stratton CJ, Callaghan B, Doherty P, Ward SM, Horowitz B. Kv channel expression in specialized smooth muscle cells and discrete plasma membrane compartments. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:451a. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz B, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Cellular and molecular basis for electrical rhythmicity in gastrointestinal muscles. Annual Reviews in Physiology. 1999;61:19–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Vanderwinden JM, Rumessen JJ. Interstitial cells of Cajal as targets for pharmacological intervention in gastrointestinal motor disorders. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1997;18:393–403. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Perrino BA, Hatton WJ, Kenyon JL, Sanders KM. Novel regulation of the A-type K+ current in murine proximal colon by calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Journal of Physiology. 1999a;517:75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0075z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Spontaneous electrical rhythmicity in cultured interstitial cells of cajal from the murine small intestine. Journal of Physiology. 1998;513:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.203by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh SD, Ward SM, Dick GM, Epperson A, Bonner HP, Sanders KM, Horowitz B, Kenyon JL. Contribution of delayed rectifier potassium currents to the electrical activity of murine colonic smooth muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1999b;515:475–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.475ac.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langton P, Ward SM, Carl A, Norell MA, Sanders KM. Spontaneous electrical activity of interstitial cells of Cajal isolated from canine proximal colon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1989;86:7280–7284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Sanders KM. Comparison of ionic currents from interstitial cells and smooth muscle cells of canine colon. Journal of Physiology. 1993;460:135–152. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Thuneberg L, Berezin I, Huizinga JD. Generation of slow waves in membrane potential is an intrinsic property of interstitial cells of cajal. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:G409–423. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.2.G409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overturf KE, Russell SN, Carl A, Vogalis F, Hart PJ, Hume JR, Sanders KM, Horowitz B. Cloning and characterization of a Kv1. 5 delayed rectifier K+ channel from vascular and visceral smooth muscles. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:C1231–1238. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen DG, Hall A, Stephens G, Stow J, Robertson B. The relative potencies of dendrotoxins as blockers of the cloned voltage-gated K+ channel, mKv1. 1 (MK-1), when stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1997;120:1029–1034. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson B, Owen D, Stow J, Butler C, Newland C. Novel effects of dendrotoxin homologues on subtypes of mammalian Kv1 potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. FEBS Letters. 1996;383:26–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SN, Overturf KE, Horowitz B. Heterotetramer formation and charybdotoxin sensitivity of two K+ channels cloned from smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1994;267:C1729–1733. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders KM, Ordog T, Koh SD, Torihashi S, Ward SM. Development and plasticity of interstitial cells of Cajal. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 1999;11:311–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1999.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott VE, Muniz ZM, Sewing S, Lichtinghagen R, Parcej DN, Pongs O, Dolly JO. Antibodies specific for distinct Kv subunits unveil a heterooligomeric basis for subtypes of alpha-dendrotoxin-sensitive K+ channels in bovine brain. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1617–1623. doi: 10.1021/bi00173a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth CW, Sweeney KM, Sanders KM. Evidence that nitric oxide acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter supplying taenia from the guinea-pig caecum. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;127:1495–1501. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuhmer W, Ruppersberg JP, Schroter KH, Sakmann B, Stocker M, Giese KP, Perschke A, Baumann A, Pongs O. Molecular basis of functional diversity of voltage-gated potassium channels in mammalian brain. EMBO Journal. 1989;8:3235–3244. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Kurtz G, Vianna-Jorge R, Pereira BF, Garcia ML, Kaczorowski GJ. Peptidyl inhibitors of shaker-type Kv1 channels elicit twitches in guinea pig ileum by blocking Kv1. 1 at enteric nervous system and enhancing acetylcholine release. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;289:1517–1522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen L, Robinson TL, Lee JC, Farraway LA, Hughes MJ, Andrews DW, Huizinga JD. Interstitial cells of Cajal generate a rhythmic pacemaker current. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:848–851. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornbury KD, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Outward currents in longitudinal colonic muscle cells contribute to spiking electrical behavior. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:C237–45. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.1.C237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogalis F, Ward M, Horowitz B. Suppression of two cloned smooth muscle-derived delayed rectifier potassium channels by cholinergic agonists and phorbol esters. Molecular Pharmacology. 1995;48:1015–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XY, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Intimate relationship between interstitial cells of cajal and enteric nerves in the guinea-pig small intestine. Cell and Tissue Research. 1999;295:247–256. doi: 10.1007/s004410051231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Beckett EA, Wang X, Baker F, Khoyi M, Sanders KM. Interstitial cells of cajal mediate cholinergic neurotransmission from enteric motor neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000a;20:1393–1403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01393.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Ordog T, Koh SD, Baker SA, Jun JY, Amberg G, Monaghan K, Sanders KM. Pacemaking in interstitial cells of Cajal depends upon calcium handling by endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Journal of Physiology. 2000b;525:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SM, Sanders KM. Pacemaker activity in septal structures of canine colonic circular muscle. American Journal of Physiology. 1990;259:G264–273. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.2.G264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]