Abstract

The ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH) is a key nucleus in the homeostatic regulation of neuroendocrine and behavioural functions. In mechanically dissociated rat VMH neurones with attached native presynaptic nerve endings, GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were recorded using the nystatin perforated patch recording mode under voltage-clamp conditions.

Histamine reversibly inhibited the sIPSC frequency in a concentration-dependent manner without affecting the mean current amplitude. The selective histamine receptor type 3 (H3) agonist imetit (100 nm) mimicked this effect and it was completely abolished by the selective H3 receptor antagonists clobenpropit (3 μm) and thioperamide (10 μm).

The GTP-binding protein inhibitor N-ethylmaleimide (10 μm) removed the histaminergic inhibition of GABAergic sIPSCs.

Elimination of external Ca2+ reduced the GABAergic sIPSC frequency without affecting the distribution of current amplitudes. In this condition, the inhibitory effect of imetit on the sIPSC frequency completely disappeared, suggesting that the histaminergic inhibition requires extracellular Ca2+.

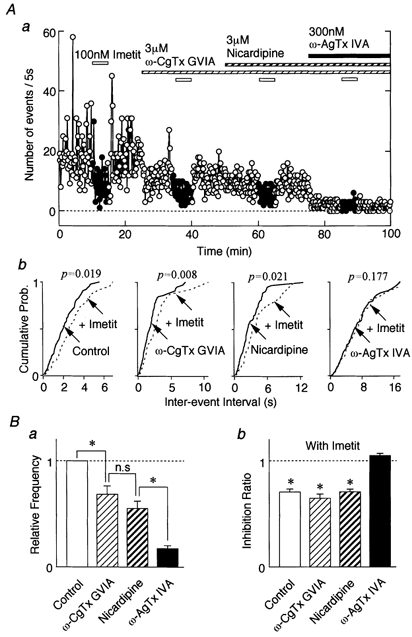

The P/Q-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-agatoxin IVA (300 nm) attenuated the histaminergic inhibition of the GABAergic sIPSC frequency, but neither the N-type Ca2+ channel blocker ω-conotoxin GVIA (3 μm) nor the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nicardipine (3 μm) was effective.

Activation of adenylyl cyclase with forskolin (10 μm) had no effect on histaminergic inhibition of the sIPSCs.

In conclusion, histamine inhibits spontaneous GABA release from presynaptic nerve terminals projecting to VMH neurones by inhibiting presynaptic P/Q-type Ca2+ channels via a G-protein coupled to H3 receptors and this may modulate the excitability of VMH neurones.

Neurones within the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) have important roles in the regulation of homeostasis and behavioural functions. A wide range of systems are affected by the VMH including the neuroendocrine and cardiovascular systems together with many affective, ingestive and sexual behaviours (for review see Canteras et al. 1994). γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS) and both GABAA and GABAB receptors are localized on VMH neurones (McCarthy et al. 1992; Priestley, 1992). In adult animals, VMH GABA transmission has a broad impact on functions that range from reproduction (McCarthy, 1995) to autonomic (Takenaka et al. 1995) and feeding behaviours (Dube et al. 1995). Recently, Tobet et al. (1999) suggested that intrinsic GABA within the VMH directly influences the embryonic development and organization of the VMH. Thus, GABA plays a pivotal role in the development and regulation of the VMH.

Three major histamine receptor subtypes, H1, H2 and H3, have been identified based on their pharmacological properties (Arrang, 1994; Hill et al. 1997). H1 and H2 receptors are located on various target neurones and modulate several ionic currents to alter neurone activity. For example, in the lateral geniculate nucleus, histamine suppresses the leak K+ conductance through an H1 receptor, while the activation of an H2 receptor shifts the voltage dependency of hyperpolarization-activated currents (McCormick & Williamson, 1991). Both H1 and H2 receptors, however, reduce the leak K+ current in neostriatal interneurones (Munakata & Akaike, 1994). The H3 receptor was initially reported as a presynaptic autoreceptor regulating the release and synthesis of histamine in the rat cerebral cortex (Arrang et al. 1983, 1985, 1987). Subsequently, H3 receptors were found to act as presynaptic heteroreceptors modulating the release of several neurotransmitters, such as noradrenaline (Schlicker et al. 1994; Endou et al. 1994), serotonin (Fink et al. 1990), GABA (Garcia et al. 1997) and glutamate (Brown & Haas, 1999). H3 receptors are also found postsynaptically in the rat striatum (Ryu et al. 1994, 1996) and tuberomammillary nucleus (Takeshita et al. 1998). Much less is known about the signal transduction pathway of H3 receptors and the mechanism of histaminergic modulation of inhibitory postsynaptic currents.

In the present study, we have isolated VMH neurones with attached native GABAergic nerve endings by dissociating them mechanically in the absence of enzymes. This procedure allowed us to investigate the histaminergic modulation of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents involved in GABAergic synaptic transmission and its signal transduction pathway.

METHODS

Preparation

Wistar rats (12-15 days old) were decapitated under pentobarbitone anaesthesia (50 mg kg−1, i.p.). The brain was quickly removed and transversely sliced at a thickness of 400 μm using a vibrating microslicer (VT1000S, Leica, Germany). Following incubation in control medium (see below) at room temperature (21-24 °C) for at least 1 h, slices were transferred to a 35 mm culture dish (Primaria 3801, Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) containing the standard external solution (see below) for dissociation. Details of the mechanical dissociation have been described previously (Rhee et al. 1999). Briefly, mechanical dissociation was accomplished using a custom-built vibration device and a fire-polished glass pipette oscillating at 3-5 Hz (0.1-0.2 mm). The ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) was identified under a binocular microscope (SMZ-1, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and the tip of the fire-polished glass pipette was lightly placed on the surface of the VMH region with a micromanipulator. The tip of the glass pipette was vibrated horizontally for about 2 min. Slices were removed and the mechanically dissociated neurones allowed to settle and adhere to the bottom of the dish for about 15 min. These dissociated neurones retained short portions of their proximal dendrites.

All experiments conformed to the guiding principles for the care and use of animals approved by The Council of The Physiological Society of Japan. Efforts were made to minimize the number of animals and any suffering.

Electrical measurements

All electrical measurements were performed using the nystatin perforated patch recording mode to allow electrical access to the cytoplasm with limited intracellular dialysis (Akaike & Harata, 1994). All voltage-clamp recordings were made at a holding potential (VH) of -60 mV (CEZ-2300, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate capillary glass (1.5 mm o.d., 0.9 mm i.d.; G-1.5, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) in two stages on a vertical pipette puller (PB-7, Narishige). The resistance of the recording pipettes filled with internal solution was 6-8 MΩ. Neurones were visualized under phase contrast on an inverted microscope (Diaphot, Nikon). Current and voltage were continuously monitored on an oscilloscope (VC-6023, Hitachi, Japan) and a pen recorder (RECTI-HORIT-8K, Sanei, Tokyo, Japan), and recorded on a digital-audio tape recorder (RD-120TE, TEAC, Japan). Membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz (E-3201A Decade Filter, NF Electronic Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) and digitized at 4 kHz. During recordings, 10 mV hyperpolarizing step pulses (30 ms in duration) were periodically delivered to monitor the access resistance. Since the stabilization of the series resistance (20-25 MΩ) took 10-15 min, experiments were initiated 25-30 min after making the tight seal. In most experiments 70-90 % series resistance compensation was applied. All experiments were performed at room temperature (21-24 °C).

Data analysis

To collect samples for analysis, 10-15 min records of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were used to assess the actions of antagonists and inhibitors and 5 min records were used for agonists. Events were counted and analysed using DETECTiVENT software (Ankri et al. 1994) and Igor Pro software (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA). Inclusion criteria required a minimum event duration of 1.0 ms together with a detection threshold of 3 pA. The amplitudes and inter-event intervals of these sets of sIPSC samples were examined by constructing cumulative probability distributions and compared using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test. The continuous curves for concentration-response relationships were fitted using a least-squares fit to the following equation:

in which I is the inhibition ratio of sIPSC frequency, C is the concentration of the drug, EC50 is the concentration for the half-maximum response and nH is the Hill coefficient. Numerical values are provided as means ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Differences in mean event amplitude and frequency were tested by Student's paired two-tailed t test using their absolute values. P values of < 0.05 were considered significant.

Solutions

The ionic composition of the incubation medium was (mm): 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4 and 10 glucose bubbled with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2. The pH was 7.45. The standard external solution consisted of (mm): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose and 10 Hepes. Ca2+-free external solution consisted of (mm): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 5 MgCl2, 2 EGTA, 10 glucose and 10 Hepes. These external solutions were adjusted to pH 7.4 with Tris-base. For recording sIPSCs, external solutions routinely contained 300 nm tetrodotoxin (TTX) to block voltage-dependent Na+ channels, and 3 μm 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) and 10 μmdl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP5) to block ionotropic glutamatergic currents. The ionic composition of the internal (patch-pipette) solution was 40 caesium methanesulfonate, 100 CsCl, 5 MgCl2 and 10 Hepes with pH adjusted to 7.2 with Tris-base. Nystatin was dissolved in acidified methanol at 10 mg ml−1. This stock solution was diluted with the internal solution just before use to a final concentration of 100-200 μg ml−1.

Drugs

Drugs used in the present study were AP5, bicuculline, CNQX, EGTA, forskolin, histamine, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), thioperamide, nicardipine and nystatin from Sigma (USA); ω-conotoxin GVIA (ω-CgTx GVIA) and ω-agatoxin IVA (ω-AgTx IVA) from the Peptide Institute (Osaka, Japan); and imetit and clobenpropit from RBI (USA). CNQX, forskolin and nicardipine were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide at 10 mm as an initial stock solution. All solutions containing drugs were applied by the Y-tube system for complete solution exchange within 20 ms (Akaike & Harata, 1994).

RESULTS

GABAergic spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents

After the mechanical dissociation of the VMH region, we found that the individual neurones were either pyramidal in shape (about 20 μm in somal diameter) or bipolar (10-15 μm). In the presence of TTX (300 nm) and the excitatory amino acid antagonists CNQX (3 μm) and AP5 (10 μm), prominent spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) were observed in these isolated VMH neurones. However, as the results of the present study will demonstrate, the sIPSCs in these mechanically dissociated VMH neurones had unusual properties and were unlike classical miniature events (Scanziani et al. 1992; Capogna et al. 1993). VMH sIPSCs were sensitive to extracellular Ca2+ entry including that through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (see below). As a result, we termed these synaptic events ‘spontaneous IPSCs’ rather than ‘miniature IPSCs’ (see below and Discussion; see also Rhee et al. 1999).

Application of 3 μm bicuculline completely and reversibly blocked VMH sIPSCs (Fig. 1A). The amplitude of these sIPSCs varied with the holding potential (VH; Fig. 1B). The reversal potential (-13.5 ± 2.8 mV) of these sIPSCs as estimated from the I-V relationship was very similar to the theoretical Cl− Nernst equilibrium potential (ECl) of -10.4 mV calculated using the extra- and intracellular Cl− concentrations of 161 and 110 mm, respectively. Thus the spontaneous events were identified as GABAergic sIPSCs mediated by GABAA receptors.

Figure 1. GABAergic sIPSCs.

Application of 3 μm bicuculline rapidly and completely blocked sIPSCs in responsive, dissociated VMH neurones. Aa and b, typical traces of sIPSCs. B, traces of sIPSCs recorded at various VH(a) and their mean amplitude I-V curve (b). In b, each point is the mean of 4 neurones. [Cl−]i and [Cl−]o show the intra- and extracellular Cl− concentrations, respectively. The continuous line is the least-squares linear fit to the mean sIPSC values at each VH.

Histaminergic modulation of GABAergic sIPSCs

Application of histamine (10 μm) or the H3 receptor-selective agonist imetit (100 nm) decreased the sIPSC frequency in the majority of the VMH neurones (100/143) tested. These responsive neurones included 63 pyramidal and 37 bipolar ones. In the remaining neurones (n = 43), these drugs did not alter either the frequency or amplitude of sIPSCs (pyramidal, 28; bipolar, 15). Mean responses show a rapid and sustained decrease in sIPSC frequency (Fig. 2Ab). Upon washing out histamine, the sIPSC frequency rebounded in a brief burst of increased sIPSC frequency before returning to control levels (Fig. 2Aa and b). Figure 2Ba and b shows cumulative probability plots for inter-event interval and current amplitude of sIPSCs. Histamine shifted the distribution to higher sIPSC frequencies without affecting the amplitude. The pooled data (n = 6) show that histamine decreased the mean sIPSC frequency to 72.5 ± 3.56 % of control (P < 0.05), but the mean amplitude was not affected significantly (103.3 ± 8.6 % of control, P = 0.776; Fig. 2Ba and b, insets). Histamine and imetit both decreased the sIPSC frequency in a similar dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2C) with the latter having a 100-fold lower EC50. The results suggest that histamine acts presynaptically to inhibit the release of GABA at these synapses.

Figure 2. Histaminergic depression of GABAergic sIPSCs.

A, application of 10 μm histamine (a) in a typical sIPSC example decreased the number of events observed per 10 s (b). Each point is the mean of 6 neurones. Dotted line is the mean of the 10 min control. B, cumulative distributions for inter-event interval (a) and current amplitude (b) of sIPSCs recorded from the same neurone. P values indicate the results of K-S tests for frequency and amplitude (341 events for control and 116 events for histamine). Inset, all amplitudes and frequencies of sIPSCs are normalized to their control (n = 6). His, histamine; Cont, control. *P < 0.05. C, concentration-response curves for the normalized sIPSC frequency of histamine and imetit. The continuous lines represent the least-squares fit. Each point is the mean of 4-8 neurones. EC50 values of histamine and imetit are about 440 and 4.7 nm, respectively. The vertical error bars represent ±s.e.m.

The H3 receptor modulates histamine release as a presynaptic autoreceptor in addition to its heteroreceptor impact on the release of other neurotransmitters (such as GABA, acetylcholine and noradrenaline) (Fink et al. 1990; Schlicker et al. 1994; Endou et al. 1994; Garcia et al. 1997; Brown & Haas, 1999). Thus, we tested the effects of the selective H3 receptor antagonists clobenpropit and thioperamide on GABAergic sIPSCs. Clobenpropit (3 μm) completely blocked the actions of histamine on GABAergic transmission (n = 5, Fig. 3A, upper trace). Likewise, the H3 agonist imetit inhibited sIPSCs (Fig. 3A, middle trace) by reducing the mean frequency to 71.5 ± 3.31 % of control (P < 0.05, n = 5) without affecting the mean amplitude (105.9 ± 5.1 % of control, P = 0.69, n = 5, Fig. 3B and C). The imetit concentration- response relationship for inhibition of sIPSC frequency was 2 log units more potent than histamine itself (Fig. 2C). The imetit action was also abolished by 3 μm clobenpropit (n = 5, Fig. 3A, lower trace) or by 10 μm thioperamide (n = 4, data not shown). Clobenpropit alone did not affect the frequency or the amplitude of sIPSCs (102.64 ± 8.76 and 99.50 ± 8.71 % of control, respectively, Fig. 3Ca and b). Such results indicate that histaminergic modulation of GABAergic synaptic transmission is mediated by presynaptic H3 receptors. Therefore, given its selectivity for these H3 receptors, imetit was used in the following experiments.

Figure 3. Presynaptic inhibition of GABAergic sIPSCs by histamine.

A, typical traces of sIPSCs observed before, during and after the application of 10 μm histamine or 100 nm imetit in the standard solution with or without 3 μm clobenpropit. The lower two traces were obtained from the same neurone. B, cumulative distributions for inter-event interval (a) and amplitude (b) of sIPSCs in the same neurone. P values indicate the results of K-S tests for frequency and amplitude (256 events for clobenpropit and 94 events for imetit in the presence of clobenpropit). C, each column is the mean of 6 neurones. All frequencies and amplitudes of sIPSCs are normalized to the control. *P < 0.05.

Involvement of G-proteins

The H3 receptor is thought to be coupled to GTP-binding proteins (G-proteins) like other presynaptic inhibitory receptors (Endou et al. 1994; Clark & Hill, 1996). To test whether H3 receptors on GABAergic presynaptic nerve terminals in the VMH are coupled to a pertussis toxin-sensitive G-protein pathway (Gi or Go), we utilized NEM, a sulphydryl-alkylating agent (Asano & Ogasawara, 1986). NEM pretreatment (10 μm) for 15 min increased sIPSC frequency to 211.25 ± 23.49 % of control (P < 0.05, n = 5) without affecting the mean amplitude (109.38 ± 9.06 % of control, P = 0.51, Fig. 4A and C). The NEM-induced increase of sIPSC frequency completely occluded the presynaptic inhibitory actions of H3 receptor activation by imetit (105.47 ± 7.14 % of NEM control, P = 0.61, n = 5) without affecting the amplitude distribution (Fig. 4B and C).

Figure 4. H3 receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of GABAergic sIPSCs is coupled to G-protein.

A, a typical trace of sIPSCs observed before, during and after the application of 100 nm imetit in solution containing 10 μm NEM. B, cumulative distributions for inter-event interval (a) and amplitude (b) of sIPSCs in the same neurone. P values indicate the results of K-S tests for frequency and amplitude (698 events for NEM and 364 events for imetit in the presence of NEM). C, each column is the mean of 4 neurones. All amplitudes and frequencies are normalized to the control. *P < 0.05.

Effect of Ca2+-free external solution

Although the postsynaptic membrane potential in our dissociated neurones can be accurately controlled by voltage clamping, the presynaptic nerve terminals are not under direct control. Since external Ca2+ entry plays an important part in the release of neurotransmitter from presynaptic nerve terminals (Wu & Saggau, 1994), we tested whether the H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of the GABAergic sIPSCs requires extracellular Ca2+ entry. Ca2+-free external solution markedly decreased the sIPSC frequency to 21.81 ± 3.96 % of control (P < 0.01, n = 5), without changing the amplitude significantly (89.45 ± 9.84 %; Fig. 5A and C). The result suggests that about 80 % of GABAergic sIPSCs depend on Ca2+ influx from the external solution. In Ca2+-free external solution, imetit failed to alter sIPSC frequency (103.45 ± 5.48 % of Ca2+-free control; Fig. 5B and C). Thus, the H3 receptor-mediated inhibitory action strongly depends on extra cellular Ca2+, suggesting a possible involvement of Ca2+ influx.

Figure 5. Effect of external Ca2+ on H3 receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition.

A, a typical trace of sIPSCs observed before, during and after the application of 100 nm imetit in Ca2+-free external solution. B, cumulative distributions for inter-event interval (a) and amplitude (b) of sIPSCs in the same neurone. P values indicate the results of K-S tests for frequency and amplitude (104 and 197 events for Ca2+-free solution with and without imetit, respectively). C, each column is the mean of 5 neurones. All amplitudes and frequencies are normalized to the control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; n.s., not significant.

Selective inhibition of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels

Multiple voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) control the release of neurotransmitters at the central synapse. N- and P/Q-types are particularly important in the evoked transmitter release at some central synapses (Wu & Saggau, 1997), while L- and P/Q-types modulate the spontaneous release of GABA in the Meynert neurones (Rhee et al. 1999). Previous studies also suggest that the modulation of VDCCs by histamine occurs presynaptically (Endou et al. 1994; Brown & Haas, 1999) as well as postsynaptically (Takeshita et al. 1998). Thus, to better understand the role of extracellular Ca2+, specific Ca2+ channel antagonists including ω-CgTx GVIA for N-type, ω-AgTx IVA for P/Q-type and nicardipine for L-type Ca2+ channels were tested. The pharmacological properties of these antagonists are well characterized (Birnbaumer et al. 1994).

When these VDCC antagonists were applied cumulatively in the order ω-CgTx GVIA (3 μm, n = 9), nicardipine (3 μm, n = 9) and ω-AgTx IVA (300 nm, n = 6), they depressed the sIPSC frequency successively to 68.46 ± 7.66, 55.10 ± 7.15 and 17.41 ± 2.78 % of control, respectively (Fig. 6Aa and Ba). These VDCC antagonists did not alter the mean amplitude or cumulative distributions of GABAergic sIPSCs (data not shown). Such findings suggest that N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (P < 0.05) but not L-type ones (P = 0.08) significantly modulated GABAergic sIPSCs. The H3 agonist imetit significantly decreased sIPSC frequency to 64.72 ± 4.12 % (P < 0.05, n = 9) and 70.94 ± 2.15 % (P < 0.05, n = 9) of control in the presence of ω-CgTx GVIA and nicardipine, respectively (Fig. 6Ab and Bb). Imetit did not affect the mean IPSC amplitude (87.40 ± 4.83 % with ω-CgTx GVIA and 106.35 ± 5.29 % with nicardipine). The effect of imetit was completely abolished in the presence of ω-AgTx IVA (104.87 ± 2.09 %, P = 0.169, n = 6, Fig. 6Bb).

Figure 6. Effect of VDCC antagonists on the H3 receptor-mediated inhibitory effect.

Aa, effect of 100 nm imetit on a typical time course of event frequency of sIPSCs under the cumulative application of VDCC antagonists in a neurone. The number of events per 5 s is plotted. Ab, cumulative distributions for inter-event interval in the same neurone. P values indicate the results of K-S tests. B, the effects of VDCC antagonists on the sIPSC frequency (a) and the inhibition ratio of imetit in the presence of VDCC antagonists (b). Each column is the mean of 6-9 neurones and is normalized to the control. * P < 0.05.

VDCC control of neurotransmitter release is often considered to be synergistic (Wu & Saggau, 1994; Mintz et al. 1995) so that the previous drug may lead to an exaggerated effect of the current drug. Therefore, imetit was tested in the presence of ω-AgTx IVA alone. ω-AgTx IVA (300 nm) itself significantly decreased GABAergic sIPSC frequency to 60.34 ± 6.57 % (P < 0.05, n = 5, Fig. 7A and B) without affecting the mean amplitude (94.78 ± 8.91 %). Pretreatment with ω-AgTx IVA completely occluded the inhibitory effect of imetit on GABAergic transmission (105.1 ± 9.42 % of ω-AgTx IVA alone condition, n = 5, Fig. 7A and B). Thus, imetit appears to decrease sIPSC frequency by selective inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels.

Figure 7. Inhibitory effect of H3 receptors on GABAergic sIPSCs mediated by P/Q-type Ca2+ channels.

A, typical traces of sIPSCs observed before, during and after the application of 100 nm imetit in the absence (upper trace) or presence (lower trace) of 300 nmω-AgTx IVA. B, each column is the mean of 5 neurones. All frequencies (a) and amplitudes (b) are normalized to control. * P < 0.05.

To test whether presynaptic depolarization influences H3 receptor modulation of GABAergic transmission, 4-AP was applied. 4-AP blocks presynaptic K+ channels, so strengthening synaptic transmission by presynaptic depolarization (Harvey & Marshall, 1977). Application of 100 μm 4-AP greatly increased sIPSC frequency to 873.98 ± 142.24 % of control (P < 0.01, n = 7, Fig. 8Aa and Ba), without altering the sIPSC amplitude (data not shown). This enhancement of sIPSC frequency is consistent with the expected depolarization of presynaptic nerve terminals, which should activate VDCCs. In the presence of 4-AP, imetit effectively depressed sIPSC frequency to 66.41 ± 2.34 % of that in the presence of 4-AP alone (n = 7, P < 0.01) without affecting sIPSC amplitude (104.30 ± 3.7 % of 4-AP control, P = 0.82). When the VDCC antagonists ω-CgTx GVIA (3 μm, n = 7), nicardipine (3 μm, n = 7) and ω-AgTx IVA (300 nm, n = 6) were applied cumulatively in the presence of 4-AP, each depressed the sIPSC frequency (49.98 ± 5.43, 24.28 ± 5.65 and 2.85 ± 0.93 % of 4-AP control, respectively; Fig. 8Aa and Ba). The results indicate that GABA release probability is significantly inhibited by VDCC antagonists even during presynaptic depolarization. However, the mean amplitude and cumulative distributions were not changed significantly (data not shown). Subsequent application of 100 nm imetit in the presence of ω-CgTx GVIA or nicardipine also significantly inhibited sIPSC frequency to 66.90 ± 4.01 % (P < 0.05, n = 7) and 65.34 ± 4.41 % (P < 0.05, n = 7) of control, respectively (Fig. 8Ab and Bb), without affecting the mean amplitude (99.69 ± 4.07 and 101.60 ± 3.54 %, respectively). H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of sIPSC frequency was completely abolished in the presence of ω-AgTx IVA (inhibition ratio 125.04 ± 15.98 %, P = 0.302, n = 6, Fig. 8Bb).

Figure 8. Effect of presynaptic depolarization on the H3 receptor-mediated inhibitory effect.

Aa, a typical time course of event frequency of sIPSCs observed before, during and after the application of 100 nm imetit in the presence of 100 μm 4-AP and various VDCC antagonists in a neurone. VDCC antagonists were applied cumulatively in the presence of 4-AP. The number of events per 5 s is plotted. Ab, cumulative distributions for inter-event intervals in the same neurone. P values indicate the results of K-S tests. B, the effects of VDCC antagonists on the sIPSC frequency in the presence of 4-AP (a) and inhibition ratio of imetit in the presence of VDCC antagonists (b). Each column is the mean of 6-7 neurones and is normalized to the control. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Possible involvement of adenylyl cyclase-cAMP pathway

Since H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of GABAergic transmission is likely to be coupled to a G-protein, a mechanism linking the activation of G-protein and the modulation of VDCCs was examined. Recently, cloned human H3 receptor studies revealed that forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation was reduced by (R)-α-methylhistamine, a selective H3 receptor agonist. Such findings suggest a coupling to the adenylyl cyclase- cAMP signal transduction pathway (Lovenberg et al. 1999).

In our VMH neurones, activation of adenylyl cyclase with 10 μm forskolin significantly increased sIPSC frequency to 270.96 ± 56.18 % of control (P < 0.05, n = 4), although mean amplitude slightly increased to 132.19 ± 14.36 % of control (Fig. 9A and C). In the presence of forskolin, 100 nm imetit decreased sIPSC frequency to 61.58 ± 8.21 % of the forskolin control (P < 0.05, n = 4) without affecting the mean amplitude (99.03 ± 5.25 %, P = 0.919, n = 4, Fig. 9B and C). This result suggests that the H3 receptor is unlikely to be coupled to the adenylyl cyclase -cAMP pathway in VMH neurones.

Figure 9. H3 receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of sIPSC is not related to the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP signal transduction pathway.

A, effect of 100 nm imetit on a typical trace of sIPSCs in the presence of 10 μm forskolin. B, cumulative distributions for inter-event intervals (a) and amplitude (b) of sIPSCs in the same neurone. P values indicate the results of K-S tests for frequency and amplitude (231 and 524 events for forskolin with or without imetit, respectively). C, each column is the mean of 4 neurones. All amplitudes and frequencies are normalized to the control. * P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Our present studies suggest that presynaptic H3 receptors inhibit GABAergic transmission in rat VMH neurones. This histaminergic inhibition of GABAergic transmission is mediated by a selective modulation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels via Gi/Go-protein coupling but not via an adenylyl cyclase-cAMP pathway.

Mechanically dissociated VMH neurones and H3 receptors

Our mechanical dissociation of rat VMH neurones yielded two morphological groups, pyramidal and bipolar neurones. In the present study, histamine and the selective H3 receptor agonist imetit depressed GABAergic synaptic transmission in most of the neurones tested, regardless of their morphological differences (bipolar, 37/52, 71 %; triangular, 63/91, 69 %). These H3 receptor actions were completely eliminated by H3 receptor-selective antagonists. Since histamine did not affect sIPSCs in the presence of H3 receptor blockade, contributions of either H1 or H2 receptors appear negligible. H3 receptors exist on the GABAergic presynaptic nerve terminals projecting to VMH neurones to mediate modulation of GABAergic sIPSCs.

GABAergic sIPSCs in VMH neurones

Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels participates in neurotransmitter release and is activated when Na+-dependent action potentials invade the axon terminal. Elevated intraterminal Ca2+ concentrations then increase the probability that transmitter-containing vesicles will fuse with the presynaptic membrane and release their contents into the synaptic cleft. However, neurotransmitter release can undergo spontaneous vesicle fusion with the presynaptic membrane, independent of conducted electrical signals. In fact, miniature excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs and mIPSCs) are recorded in the presence of TTX, which blocks Na+-dependent action potentials. Since the frequency of both mEPSCs and mIPSCs in the presence of TTX is unaffected by further removal of extracellular Ca2+ or by the application of Cd2+ or Co2+ (Scanziani et al. 1992; Capogna et al. 1993), these events should not depend on extracellular Ca2+ entry and/or VDCCs.

In contrast, in the present study, the frequency of GABAergic sIPSCs in the presence of TTX was greatly reduced by removal of extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5C), an observation consistent with the possible involvement of Ca2+ influx from the external solution even during Na+ channel blockade. Cumulative application of VDCC antagonists greatly reduced the sIPSC frequency (Fig. 6Ba). Thus, the GABA release probability in VMH neurones is closely related to Ca2+ influx through VDCCs. Such findings suggest that the GABAergic nerve terminals on VMH neurones may have a somewhat depolarized membrane potential. At depolarized potentials, the spontaneous activation of VDCCs may result in the release of GABA. Events that remain in Ca2+-free solution may be classical miniature synaptic currents. Alternatively, the synaptic events observed in the present preparation might be Ca2+-dependent mIPSCs. Actually, Ca2+-dependent mIPSCs have been reported in rat central neurones (Doze et al. 1995; Soltesz & Mody, 1995). Recently, Rhee et al. (1999) also reported that L- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels contribute to the appearance of GABAergic sIPSCs in mechanically dissociated rat Meynert neurones. However, the reason for the dependency of sIPSCs on extracellular Ca2+ and/or VDCCs remains incompletely understood.

The mechanism of histaminergic modulation of GABAergic sIPSCs

H3 receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition is blocked by agents that inactivate Gi/Go-proteins such as pertussis toxin (Endou et al. 1994) or NEM (Schlicker et al. 1994). Such results are consistent with the present findings using NEM in VMH neurones. Signal transduction and radioligand binding studies recently revealed that the clone GPCR97 is the Gi-coupled histamine H3 receptor (Lovenberg et al. 1999). Thus, H3 receptors may generally be coupled to Gi/Go-proteins. Activation of presynaptic receptors coupled to G-proteins could utilize at least three possible mechanisms to depress synaptic transmission (Wu & Saggau, 1997). Firstly, the activation of presynaptic K+ channels could hyperpolarize the presynaptic terminals, resulting in decreased excitability and therefore decreased synaptic release. Secondly, the inhibition of presynaptic VDCCs could reduce Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. Thirdly, actions on the proteins of the transmitter release machinery, such as synaptobrevin, could lower neurotransmitter release probability.

If histaminergic inhibition is related to the modulation of the synaptic release machinery, which does not depend on Ca2+ influx, then the inhibition by imetit should remain after the removal of extracellular Ca2+. In the present study, however, the effects of imetit disappeared in Ca2+-free extracellular solution (Fig. 5). Thus, the actions of imetit in VMH neurones might not be directly related to the synaptic release machinery, but may depend more closely on extracellular Ca2+ and VDCCs. Experiments using selective VDCC antagonists support a key contribution of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels to histaminergic modulation of GABAergic sIPSCs (Figs 6, 7 and 8).

H3 receptor-mediated presynaptic modulation attenuates noradrenaline release from sympathetic nerve endings by inhibiting N-type Ca2+ channels via Gi/Go-protein in the guinea-pig myocardium (Endou et al. 1994). In rat hippocampal slices, histamine also inhibited glutamate release by inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ entry via a direct G-protein-mediated inhibition of multiple Ca2+ channels (Brown & Haas, 1999). In the light of our present results, coupling between H3 receptors and VDCCs might vary across brain regions. Alternatively, particular H3 receptor subtypes might be selectively coupled to specific VDCCs. Radioligand binding studies with selective H3 agonists identified two binding sites with high and low affinity, and possible heterogeneity among the binding sites (Arrang et al. 1990; West et al. 1990; but see also Brown et al. 1996). Clearly, further studies are required to discern the details of specific coupling between H3 receptors and VDCCs.

The activation of H3 receptors inhibits histamine release by activating K+ channels in rat posterior hypothalamus (Yang & Hatton, 1991). Although it is not known whether K+ channels are modulated directly by G-proteins or indirectly by soluble second messengers, our present results in VMH neurones are not consistent with H3 actions at K+ channels, in agreement with other studies (Schlicker et al. 1994; Brown & Haas, 1999).

Second messengers

In general, βγ-subunits of G-proteins can directly modulate the α-subunit of VDCCs in many receptors coupled to G-proteins (Dolphin, 1998). Previous studies suggest that inhibition of evoked glutamate release by histamine in rat hippocampus was not related to any second-messenger system (Brown & Haas, 1999). Here we found that the effects of H3 receptor activation on GABAergic sIPSCs persisted in the presence of adenylyl cyclase activation and thus may not be related to the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP pathway (Fig. 9). Histaminergic modulation of GABAergic sIPSCs is thus probably mediated by the inhibition of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels via a direct action of G-protein βγ-subunits. In a functional expression study, however, Lovenberg et al. (1999) revealed that expression of the cloned human H3 receptor inhibited cAMP formation, suggesting an involvement of the adenylyl cyclase-cAMP pathway. Further study of the coupling to second-messenger systems will be necessary to resolve whether additional H3 receptor subtypes are responsible.

Physiological implications

The present results revealed that the activation of presynaptic H3 receptors inhibits GABAergic synaptic transmission. In hypothalamic neurones, GABA-induced postsynaptic responses change from depolarization to hyperpolarization during postnatal development (Chen et al. 1996), suggesting that GABAergic systems may be closely related to neuronal maturation during postnatal development. In addition, since GABAergic systems are closely related to VMH function in adult as well as young animals (Dube et al. 1995; Takenaka et al. 1995; Tobet et al. 1999), histamine may have an important role in the regulation of VMH function during neuronal development. In such a view, histaminergic modulation of GABAergic transmission may contribute to the development and regulation of VMH function as well as the excitability of VMH neurones. It would be interesting to determine whether the histaminergic modulation of GABAergic transmission found in the present study changes with development.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Drs M. C. Andresen and A. Moorhouse for critically reading the manuscript. This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research, The Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, Japan (nos 10044301 and 10470009), The Japan Health Sciences Foundation (no. 21279, Research on Brain Science), and Kyushu University Interdisciplinary Programs in Education and Projects in Development to Norio Akaike.

References

- Akaike N, Harata N. Nystatin perforated patch recording and its application to analysis of intracellular mechanism. Japanese Journal of Physiology. 1994;44:433–473. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.44.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankri N, Legendre P, Faber DS, Korn H. Automatic detection of spontaneous synaptic responses in central neurons. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1994;52:87–100. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM. Pharmacological properties of histamine receptor subtypes. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 1994;40:273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Schwartz JC. Auto-inhibition of brain histamine release mediated by a novel class (H3) of histamine receptor. Nature. 1983;302:832–837. doi: 10.1038/302832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Schwartz JC. Autoregulation of histamine release in brain by presynaptic H3-receptors. Neuroscience. 1985;15:553–562. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Schwartz JC. Autoinhibition of histamine synthesis mediated by presynaptic H3-receptors. Neuroscience. 1987;23:149–157. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM, Roy J, Morgat JL, Schunack W, Schwartz JC. Histamine H3 receptor binding sites in rat brain membranes: modulations by guanine nucleotides and divalent cations. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990;188:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(90)90005-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano T, Ogasawara N. Uncoupling of gamma-aminobutyric acid B receptors from GTP-binding proteins by N-ethylmaleimide: effect of N-ethylmaleimide on purified GTP-binding proteins. Molecular Pharmacology. 1986;29:224–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaumer L, Campbell KP, Catterall WA, Harpold MM, Hofmann F, Horne WA, Mori Y, Schwartz A, Snutch TP, Tanabe T, Tsien RW. The naming of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron. 1994;13:505–506. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, O'Shaughnessy CT, Kilpatrick GJ, Scopes DI, Beswick P, Clitherow JW, Barnes JC. Characterization of the specific binding of the histamine H3 receptor antagonist radioligand [3H] GR168320. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;311:305–310. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Haas HL. On the mechanism of histaminergic inhibition of glutamate release in the rat dentate gyrus. Journal of Physiology. 1999;515:777–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.777ab.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW. Organization of projections from the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: a Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin study in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994;348:41–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna M, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Mechanism of μ-opioid receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1993;470:539–558. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Trombley PQ, van den Pol AN. Excitatory actions of GABA in developing hypothalamic neurones. Journal of Physiology. 1996;494:451–464. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark EA, Hill SJ. Sensitivity of histamine H3 receptor agonist-stimulated [35S]GTP gamma[S] binding to pertussis toxin. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;296:223–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. Mechanisms of modulation of voltage-dependent calcium channels by G proteins. Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.003bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doze VA, Cohen GA, Madison DV. Calcium channel involvement in GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition of GABA release in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;74:43–53. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube MG, Kalra PS, Crowley WR, Kalra SP. Evidence of a physiological role for neuropeptide Y in ventromedial hypothalamic lesion-induced hyperphagia. Brain Research. 1995;690:275–278. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endou M, Poli E, Levi R. Histamine H3-receptor signaling in the heart: possible involvement of Gi/Go proteins and N-type Ca2+ channels. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;269:221–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink K, Schlicker E, Neise A, Gothert M. Involvement of presynaptic H3-receptors in inhibitory effect of histamine on serotonin release in the rat brain cortex. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1990;342:513–519. doi: 10.1007/BF00169038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M, Floran B, Arias-Montano JA, Young JM, Aceves J. Histamine H3 receptor activation selectively inhibits dopamine D1 receptor-dependent [3H]GABA release from depolarization-stimulated slices of rat substantia nigra pars reticulata. Neuroscience. 1997;80:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AL, Marshall IG. The facilitatory actions of aminopyridines and tetraethylammonium on neuromuscular transmission and muscle contractility in avian muscle. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1977;299:53–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00508637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SJ, Ganellin CR, Timmerman H, Schwartz JC, Shankley NP, Young JM, Schunack W, Levi R, Haas HL. International Union of Pharmacology. XIII. Classification of histamine receptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 1997;49:253–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovenberg TW, Roland BL, Wilson SJ, Jiang X, Pyati J, Huvar A, Jackson MR, Erlander MG. Cloning and functional expression of the human histamine H3 receptor. Molecular Pharmacology. 1999;55:1101–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM. Functional significance of steroid modulation of GABAergic neuro-transmission: analysis at the behavioral, cellular, and molecular levels. Hormones and Behavior. 1995;29:131–140. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1995.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy MM, Coirini H, Schumacher M, Johnson AE, Pfaff DW, Schwartz-Giblin S, McEwen BS. Steroid regulation and sex differences in 3H-mucimol binding in hippocampus, hypothalamus and midbrain in rats. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 1992;4:393–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1992.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, Williamson A. Modulation of neural firing mode in cat and guinea pig LGNd by histamine: possible cellular mechanisms of histaminergic control of arousal. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:3188–3199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03188.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Calcium control of transmitter release at cerebellar synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:675–688. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munakata M, Akaike N. Regulation of K+ conductance by histamine H1 and H2 receptors in neurones dissociated from rat neostriatum. Journal of Physiology. 1994;480:233–245. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestley T. The effect of baclofen and somatostatin on neuronal activity in the rat ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90018-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee J-S, Ishibashi H, Akaike N. Calcium channels in the GABAergic presynaptic nerve terminals projecting to Meynert neurons of the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;72:800–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Yanai K, Watanabe T. Marked increase in histamine H3 receptors in the striatum and substantia nigra after 6-hydroxydopamine-induced denervation of dopaminergic neurons: an autoradiographic study. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;178:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu JH, Yanai K, Zhao X-L, Watanabe T. Effects of chronic treatments with dopamine D1 and D2 agonists on histamine H3, dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in unilaterally 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1996;118:610–613. [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M, Capogna M, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Presynaptic inhibition of miniature excitatory synaptic currents by baclofen and adenosine in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1992;9:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Kathmann M, Detzner M, Exner HJ, Gothert M. H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of noradrenaline release: an investigation into the involvement of Ca2+ and K+ ions, G protein and adenylate cyclase. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1994;350:34–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00180008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltesz I, Mody I. Ca2+-dependent plasticity of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents after amputation of dendrites in central neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1995;73:1763–1773. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.5.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka K, Sasaki S, Nakamura K, Uchida A, Fujita H, Itoh H, Nakata T, Takeda K, Nakagawa M. Hypothalamic and medullary GABAA and GABAB-ergic systems differently regulate sympathetic and cardiovascular systems. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1995;22:S48–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita Y, Watanabe T, Sakata T, Munakata M, Ishibashi H, Akaike N. Histamine modulates high-voltage-activated calcium channels in neurons dissociated from the rat tuberomammillary nucleus. Neuroscience. 1998;87:797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Henderson RG, Whiting PJ, Sieghart W. Special relationship of γ-aminobutyric acid to the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus during embryonic development. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1999;405:88–98. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990301)405:1<88::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RE, Zweig A, Shin NY, Siegel MI, Egan RW, Clark MA. Identification of two H3-histamine receptor subtypes. Molecular Pharmacology. 1990;38:610–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Saggau P. Pharmacological identification of two types of presynaptic voltage-dependent calcium channels at CA3-CA1 synapses of the hippocampus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:5613–5622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05613.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LG, Saggau P. Presynaptic inhibition of elicited neurotransmitter release. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang OZ, Hatton GI. H3-Histamine receptors activate K+ channels to hyperpolarize magnocellular histaminergic neurons of rat posterior hypothalamus. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1991;17:409. [Google Scholar]