Abstract

Nicotinic effects on glycine release were investigated in slices of lumbar spinal cord using conventional whole-cell recordings. In most of the substantia gelatinosa (SG) neurons tested, nicotine increased the frequency of the glycinergic spontaneous miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs). In a smaller proportion, nicotine evoked not only this same presynaptic response but also a postsynaptic response.

Nicotinic facilitation of glycinergic mIPSCs was investigated in mechanically dissociated SG neurons using nystatin-perforated patch recordings. Nicotine (3 × 10−6 to 10−5m) reversibly enhanced the frequency of glycinergic mIPSCs without altering their amplitudes, thus indicating that nicotine facilitates glycine release through a presynaptic mechanism.

Choline, a selective α7 subunit of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) agonist, had no effect on the mIPSC frequency while anatoxin A, a broad-spectrum agonist of nAChR, facilitated the mIPSC frequency.

α-Bungarotoxin, a selective α7 subunit antagonist, failed to block the nicotinic facilitatory action. Mecamylamine, a broad-spectrum nicotinic antagonist, reversibly inhibited nicotinic action. Dihydro-β-erythroidine, a selective antagonist of nAChRs containing α4-β2 subunits, completely blocked nicotinic action.

Ca2+-free but not Cd2+-containing bath solutions blocked nicotinic actions.

We therefore conclude that nicotine facilitates glycine release in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal dorsal horn via specific nAChRs containing α4-β2 subunits. This action on a subset of presynaptic nAChRs may underlie nicotine's modulation of noxious signal transmission and provide a cellular mechanism for the analgesic function of nicotine.

Nicotine exerts antinociceptive effects by interacting with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) which are present throughout the neuronal pathways involved in the neural processing of pain (Wada et al. 1989; Bannon et al. 1998; Marubio et al. 1999). While these receptors can be assembled from a variety of different subunits, the α4 and β2 subunits of the nAChRs seem to be important components of the nicotinic receptors that mediate this antinociceptive action (Picciotto et al. 1998; Marubio et al. 1999).

Most Aδ and C fibres which carry nociceptive information from peripheral tissues preferentially terminate in the superficial dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The substantia gelatinosa (SG) is a region which has been considered to be a critical site in the processing of nociceptive information and this region may control the activity of projection neurons (Kumazawa & Perl, 1978; Yoshimura & Jessell, 1989). Glycine is a major inhibitory transmitter in the spinal cord. SG neurons receive prominent glycinergic input from local interneurons, and glycinergic transmission could be involved in spinal antinociception (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1995). Various nAChR subunits are expressed in the SG region of the rat spinal cord (Wada et al. 1989). In addition, immunocytochemical studies of choline acetyltransferase have revealed that intrinsic spinal cholinergic neurons exist in the deep dorsal horn, especially in lamina III, and that these neurons terminate in areas of the superficial dorsal horn including the SG (Borges & Iversen, 1986; Ribeiro-da-Silva & Cuello, 1990).

At the cellular level, neuronal nAChRs in the central nervous system (CNS) appear to be important modulators of neurotransmitter release. The activation of presynaptic nAChRs can enhance the release of noradrenaline, dopamine, serotonin, GABA, glutamate and ACh itself (McGehee & Role, 1995; Wonnacott, 1997; MacDermott et al. 1999). However, the mechanisms by which presynaptic nAChRs affect glycinergic transmission are still poorly understood.

Since the cholinergic mechanisms in SG might account for nicotine-associated analgesia, we investigated the nicotinic modulation of glycinergic transmission. We studied nicotinic actions on spontaneous glycinergic miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) by dissociating SG neurons in a manner that preserved the functioning native presynaptic glycinergic nerve endings (Akaike et al. 1992; Rhee et al. 1999).

METHODS

All experiments conformed to the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Animals approved by the Council of the Physiological Society of Japan. All efforts were made to minimize both the number of animals used and any suffering.

Mechanical dissociation

The cell dispersion method has been previously described (Rhee et al. 2000). Briefly, 10- to 14-day-old Wistar rats were decapitated under pentobarbital anaesthesia. The spinal cord was quickly removed from the lumbar vertebral canal and was then sliced at a thickness of 400 μm with a microslicer (DTK-1000, Dosaka, Kyoto, Japan). The slices were incubated for at least 1 h in an incubation solution at room temperature (22–25 °C). The ionic composition of the incubation solution was (mm): 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 24 NaHCO3, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4 and 10 glucose, which was adjusted to 7.4 with 95 % O2 and 5 % CO2.

Following incubation, the slices were transferred into a 35 mm culture dish (Primaria 3801, Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) and the SG region of the spinal cord was identified under a binocular microscope (SMZ-1, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). A fire-polished glass pipette was advanced to contact the surface of the SG region (laminae II) and the pipette was vibrated at 3–5 Hz with an excursion amplitude of 0.3–0.5 mm for about 2 min using our custom-made dissociation apparatus. The speed and excursion amplitude of the pipette vibration were tuned by an AC power supply. Following the removal of the slices, the mechanically dissociated SG neurons adhered to the bottom of the dish within 10 min. Note that these neurons were dissociated without using any enzymes. This procedure could produce neurons that retained prominent morphological features, including extensive portions of the proximal dendritic processes, which are not often found in neurons dissociated by enzymes and trituration. Hence, synaptic activities could thus be detected since the synaptic boutons are retained.

Although no synaptic boutons were visualized, dissociated neurons were visualized using phase-contrast optics (× 400) on an inverted microscope (Diaphot, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Slice preparation

Wistar rats, 13–15 days old, were decapitated under pentobarbital anaesthesia. The spinal cord was quickly removed from the lumbar vertebrae and was then sliced at a thickness of 230 μm with a microslicer (VT-1000S, Leica, Germany) in a cold (0–4 °C) low-Na+ (including sucrose) solution. The ionic composition of the low-Na+ solution was (mm): 230 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 Na2HPO4, 10 MgSO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 30 glucose. The slices were transferred to the incubation solution at 30–35 °C for about 1 h. For the recordings, the slices were transferred to a recording chamber and the SG region was identified under an upright microscope (Axioscope, Zeiss, Germany). Oval or triangular neurons with somatic diameters, measuring about 20 μm in size, were selected for the recordings. The bath solution was perfused at 2–3 ml min−1.

Electrical measurements

In the dissociated neurons, whole-cell recordings were made using the nystatin-perforated patch method (Akaike & Harata, 1994), whereas in the slice preparations, the conventional whole-cell open patch method was used. The nystatin-perforated patch recording for the dissociated neurons allows recording of synaptic activities for >2 h. All recordings were performed under the voltage-clamp mode, using an EPC-7 amplifier (List-Electronic, Germany). Patch pipettes were made from borosilicate glass capillary tubes (1.5 mm o.d., 0.9 mm i.d.; G-1.5, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) in two stages on a vertical pipette puller (PB-7, Narishige). The ionic composition of the internal (patch pipette) solution for the nystatin-perforated patch recording was (mm): 20 N-methyl-d-glucamine methanesulphonate, 20 caesium methanesulphonate, 5 MgCl2, 100 CsCl and 10 Hepes. The pH of the internal solution was adjusted to 7.2 with Tris-OH. Nystatin was dissolved in acidified methanol at 10 mg ml−1. The stock solution was diluted with an internal solution just before use to a final concentration of 100–200 μg ml−1. The ionic composition of the internal (open patch pipette) solution for the conventional whole-cell patch recording was (mm): 43 CsCl, 92 caesium methanesulphonate, 5 TEA-Cl, 2 EGTA, 4 ATP-Mg and 10 Hepes, which was adjusted to 7.2 with Tris-OH. The resistance of the recording electrodes was 5–7 MΩ.

The membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz (E-3201A Decade Filter, NF Electronic Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) and data were digitized at 4 kHz. The current and voltage were monitored on both an oscilloscope (Tektronix 5111A, Sony, Tokyo, Japan) and a pen recorder (Recti-Horiz 8K, Nippondenki San-ei, Tokyo, Japan).

Data analysis

The events were counted from the digitized records using pCLAMP (version 8.0, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), which were set so as to include a minimum of 100 events in each strategy. The threshold criteria used for sampling the mIPSCs were determined from both amplitude and area of individual synaptic events, which were analysed using the Mini Analysis Program by Justin Lee (version 5.01, Synaptosoft Inc., Decatur, GA, USA). Analysis of mIPSCs was performed with a cumulative probability plot, and cumulative amplitude histograms were compared using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for significant difference (P < 0.05) with the Mini Analysis. The postsynaptic responses by nicotine were defined as the response of the visible inward currents. The relative frequency and/or amplitude were shown as a ratio of each control value (= 1). The average summary values are provided as means ±s.e.m. Any differences in the mean amplitude and frequency distribution were tested by Student's paired two-tailed t test.

Solutions

The ionic composition of the external standard solution was (mm): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose and 10 Hepes. The Ca2+-free external solution contained (mm): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 3 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 Hepes and 2 EGTA. These external solutions were adjusted to pH 7.2 with Tris-OH.

In the recording of mIPSCs, these solutions routinely contained 3 × 10−7m tetrodotoxin (TTX) to block voltage-dependent Na+ channels, 3 × 10−6m bicuculline to block GABAA response, and 10−6-10−5m 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), and 10−5mdl-2-amino-5-phosphovaleric acid (dl-AP5) to block glutamatergic responses. As reported previously, these concentrations of drugs were sufficient to block each targeted response (Rhee et al. 2000).

Drugs

The following drugs used for this study were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA): nicotine, dl-AP5, bicuculline, CNQX, EGTA, nystatin, mecamylamine (MEC) and α-bungarotoxin (α-BgTx). Choline, tetrodotoxin (TTX) and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) were purchased from the Isuzu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Osaka, Japan), Wako Pure Chemical (Tokyo, Japan) and RBI (MA, USA), respectively. For the stock solution, 10−2m CNQX was prepared in pure dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO). Drug solutions were applied, using the ‘Y-tube system’ which exchanged solutions completely within 20 ms (Murase et al. 1990).

RESULTS

Nicotine actions on SG neurons in slice preparation

Spontaneous postsynaptic currents (PSCs) were recorded from SG neurons in slice preparation, using conventional, open patch whole-cell recordings, held at a holding potential (Vh) of −70 mV under the voltage-clamp mode. In the presence of 3 × 10−7m TTX, 10−5m AP5, 10−5m CNQX and 10−5m bicuculline, glycinergic spontaneous miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were inward, since the theoretical Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) was −25.3 mV calculated from the Nernst equation using 129 mm[Cl−]o and 49 mm[Cl−]i in slice experimental conditions.

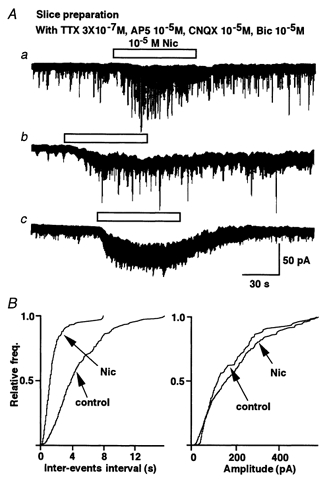

In the most common response pattern, nicotine (10−5m) reversibly and significantly facilitated the glycinergic mIPSC frequency without altering the mIPSC amplitude (Fig. 1Aa and B; n = 6/14, P < 0.01). In other cells, nicotine induced a slow postsynaptic inward current with (n = 3/14) or without (n = 2/14) altering mIPSC frequency (Fig. 1Ab and c). In addition to these nicotine-responsive neurons, three neurons failed to respond to nicotine at all (data not shown).

Figure 1. Nicotine responses of substantia gelatinosa (SG) neurons in spinal cord slices.

Whole-cell recordings were performed on SG neurons in slices of lumbar spinal cord. VH was −70 mV. A, representative traces are shown. In the presence of Na+ channel blocker (3 × 10−7m TTX), ionotropic glutamate receptor blockers (10−5m AP5 and 10−5m CNQX) and GABAA receptor blocker (10−5m bicuculline), nicotine (10−5m) evoked a variety of responses in different SG neurons. Most commonly (Aa), nicotine increased the frequency of glycinergic mIPSCs. In a smaller proportion of SG neurons, nicotine evoked not only this presynaptic response (Ab) but also evoked a sustained inward current (postsynaptic response). Two neurons showed only a postsynaptic response (Ac). B, nicotine shifted the cumulative frequency but not the amplitude distribution of mIPSCs from the same neuron showed in Aa.

To better understand the mechanisms underlying the nicotinic presynaptic action, we turned to a simpler preparation in which the neurons were dissociated from the slices. We used purely mechanical dissociation in order to preserve functional and native glycinergic presynaptic nerve endings (Akaike et al. 1992; Rhee et al. 1999). Unlike other approaches (Drewe et al. 1988), the elimination of enzymes minimized possible proteolytic changes in the isolated neurons. As a result, all of the following experiments were conducted on this dissociated neuron preparation.

Glycine and GABA release in dissociated SG neurons

The dissociated SG neurons had oval, fusiform or triangular somata with somatic diameters ranging in size from 15 to 30 μm. Spontaneous mIPSCs were recorded from mechanically dissociated SG neurons using nystatin-perforated patch recordings held at a VH of −60 mV under voltage clamp.

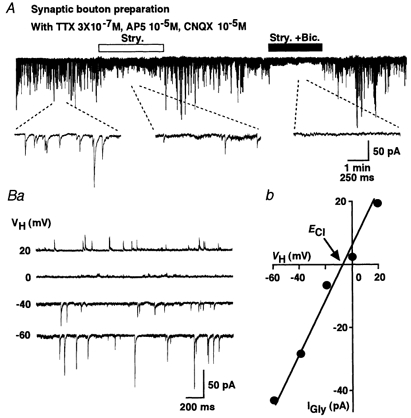

Strychnine (10−7m), a selective glycine receptor antagonist, reversibly blocked nearly all mIPSCs in the presence of 3 × 10−7m TTX, 10−6m CNQX and 10−5m AP5 (Fig. 2A). Bicuculline (3 × 10−6m), a selective GABAA receptor antagonist, blocked the remaining mIPSCs (n = 6; Fig. 2A). Since these SG neurons received a mixture of glycinergic and GABAergic inputs, bicuculline (3 × 10−6m) was added to the mixture of blockers in the external solution to isolate the glycinergic mIPSCs for all subsequent studies.

Figure 2. Glycinergic spontaneous miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs).

A, strychnine reversibly blocked most mIPSCs at a VH of −60 mV, and subsequent application of bicuculline completely blocked mIPSCs in the presence of TTX, AP5 and CNQX. Insert traces were expanded from each stage. Ba, representative recordings of glycinergic mIPSC at various VH values are shown. Bb, a plot of the mean amplitude of glycinergic mIPSCs during 3 min recorded period at various VH values. The reversal potential of glycinergic mIPSCs (EGly) was close to the ECl.

VH altered the amplitude of the mIPSC. The resulting current-voltage (I–V) relationship had a reversal potential (EGly) of glycinergic mIPSCs estimated from a linear regression of the average amplitude at each VH, which was −9.5 mV. This value was close to the ECl of −10.4 mV calculated from the Nernst equilibrium using the given extra- and intracellular Cl− concentrations (161 and 110 mm, respectively). This result verifies that these mIPSCs were mediated by a highly Cl−-selective channel, and this result was consistent with that for the strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors (Fig. 2B).

Pre- and postsynaptic nicotinic action on SG neurons

The nicotine responses of the dissociated SG neurons (n = 169) varied but were generally similar to the responses of such neurons in the slices. Most commonly (62/169, 36.7 %), nicotine (3 × 10−6m) increased the mIPSC frequency without affecting the mIPSC amplitude distribution (Figs 3A and 4). Unless otherwise noted, all tests used solutions with 3 × 10−6m nicotine. In a substantial proportion of SG neurons (40/169, 23.7 %), nicotine evoked a sustained inward current (a postsynaptic action) simultaneous with an increase of the mIPSC frequency (a presynaptic action) (Fig. 3B). Nicotine induced only postsynaptic transient inward currents without changing mIPSC frequency in 17.2 % of neurons (Fig. 3C; n = 29/169). In all the neurons tested, the amplitude distribution of mIPSCs was not modified by nicotine (data not shown), thus suggesting that nAChRs and glycine receptors did not interact postsynaptically. The remainder of the neurons (38/169, 22.5 %) were unresponsive to nicotine with neither a pre- nor postsynaptic effect (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Nicotine evoked several response patterns.

Glycinergic mIPSCs were specifically isolated by the presence of TTX, AP5, CNQX and bicuculline. Left panel shows diagrammatic representation of pre- and postsynaptic nAChRs. The accompanying right panels display traces of representative nicotine response recordings. Most commonly, nicotine selectively facilitated mIPSC frequency, a presynaptic response profile (A). In other neurons, nicotine both increased the mIPSC frequency and also evoked a steady inward current (postsynaptic response, B). In some SG neurons, nicotine only induced the postsynaptic inward current (C) or had no effect at all (D).

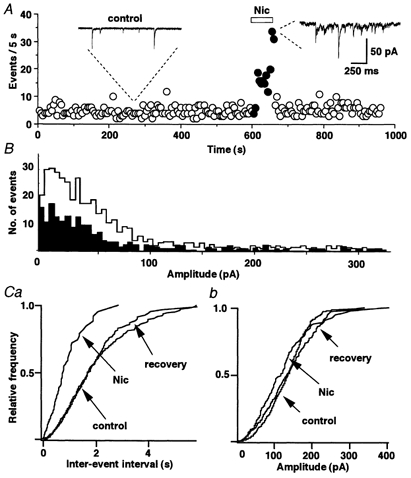

Figure 4. Nicotine alters glycinergic mIPSCs presynaptically.

A, representative example of the time course of event frequency before, during and after the application of nicotine. Inserts show the recordings of mIPSCs before and during the nicotine application. B, amplitude histograms show that nicotine uniformly increases the number of events at all amplitudes from control (black) to during the application of nicotine (white) (P = 0.25 by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; number of events 223 for control and 506 for nicotine). C, only the cumulative frequency distribution (a) was affected by nicotine. The amplitude distribution (b) of mIPSC was constant in the same neuron as shown in A.

To clearly characterize the mechanisms of presynaptic nAChRs, we focused our analysis on the most common SG neurons, those with presynaptic but without postsynaptic nicotinic responses (as shown in Fig. 3A). In a representative example, nicotine substantially increased the mIPSC frequency (Fig. 4A; 627.3 ± 42.9 %, P < 0.01) but did not alter the distribution of mIPSC amplitudes. The increase in the number of events in this SG neuron was evenly distributed across all event amplitudes (Fig. 4B). The overall distribution of the mIPSC amplitudes during application of nicotine was similar to that before the application of nicotine. Nicotine substantially shifted the frequency distribution (Fig. 4C) to shorter intervals, thus indicating that the probability of glycine release from the presynaptic nerve terminals is greatly facilitated by the application of nicotine. Similar results were observed in all 62 neurons with this response phenotype.

In addition, nicotine did not alter the kinetic characteristics of the mIPSCs (data not shown).

Pharmacological profiles of presynaptic nAChRs

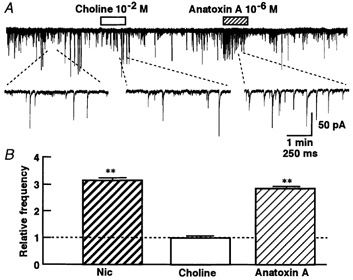

Presynaptic nAChRs in the mammalian CNS contain the α-BgTx-sensitive α7 subunit (Role & Berg, 1996). In addition, their activation enhances neurotransmitter release. However, presynaptic α-BgTx-insensitive nAChRs and/or high affinity α-BgTx-insensitive nAChRs also include nAChRs containing the α4-β2 subunits (Guo et al. 1998), which may facilitate neurotransmitter release. To characterize the pharmacological profile of the nAChRs at glycinergic nerve terminals on SG neurons, we tested choline at an agonist concentration selective for the α7 subunit (Alkondon et al. 1999). Choline (10−2m) had no effect on the mIPSC frequency (Fig. 5A). However, the broad-spectrum nAChR agonist, anatoxin A (10−6m) (Thomas et al. 1993), increased the mIPSC frequency in a manner similar to that of nicotine itself.

Figure 5. nAChR agonist profile of mIPSC facilitation.

A, representative recordings of choline and anatoxin A actions, which were applied during a 1 min period. Insert traces were expanded from the indicated portion of the experiment. B, the pooled mean frequency data are shown as mIPSC frequency relative to control. Each column is the mean of six neurons. **P < 0.01vs. control.

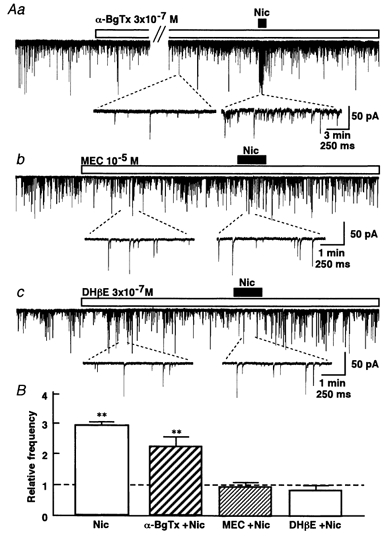

The facilitatory effect of nicotine was not altered by exposure to α-BgTx (3 × 10−7m) for > 40 min in SG neurons (Fig. 6Aa). The application of α-BgTx had no effect on either the glycinergic mIPSC frequency or the amplitude. The nicotinic action was abolished in the presence of mecamylamine (10−5m), a broad-spectrum nicotinic antagonist (P < 0.01, n = 7; Fig. 6Ab). DHβE (3 × 10−7m), an antagonist for nAChRs containing the selective α4-β2 subunit, also completely blocked the facilitatory actions of nicotine (P < 0.01, n = 4; Fig. 6Ac). These results indicate that the nAChRs mediating the facilitation of glycine release contain α4 but not α7 subunits, possibly in association with the β2 subunits.

Figure 6. nAChR selective antagonism of nicotinic facilitation of mIPSCs.

A, representative recordings of nicotinic effects on glycinergic mIPSCs in the presence or absence of 3 × 10−7mα-BgTx (a; n = 5), 10−5m mecamylamine (b; n = 7) and 3 × 10−7m DHβE (c; n = 4). α-BgTx was treated at least 40 min before the application of nicotine. Mecamylamine and DHβE were treated 5 min before the application of nicotine. Insert traces were expanded from the indicated time points within the experiment. B, the pooled data are shown as mIPSC frequency relative to control. **P < 0.01vs. control.

Role of Ca2+ in nicotinic facilitation

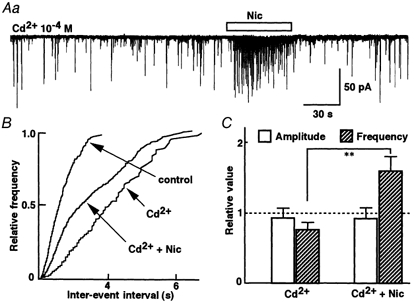

Neuronal nAChRs, particularly those containing α7 subunits, can display a high permeability of Ca2+ and Na+ (Rathouz & Berg, 1994) and the resulting Ca2+ influx may cause a facilitation of neurotransmitter release. Activation of presynaptic nAChRs depolarizes the nerve terminals and activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels to facilitate neurotransmitter release (Lena & Changeux, 1997). To test whether Ca2+ influx contributes to the nicotine-induced facilitation of glycine release, we examined the effect of Cd2+ at 10−4m, a concentration which blocks high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels (Hille, 1992). HVA Ca2+ channels are generally assumed to be responsible for the presynaptic Ca2+ influx causing neurotransmitter release (Dunlap et al. 1995). In the presence of Cd2+, the mIPSC frequency decreased by 24 % without changing mIPSC amplitude (Fig. 7C). However, Cd2+ failed to block nicotinic enhancement of the mIPSC frequency (Fig. 7A; n = 5). The mIPSC amplitude was not affected by nicotine in this condition. The facilitatory effect of nicotine on mIPSC frequency was similar in the presence and absence of Cd2+. It therefore seems that the presynaptic action of nicotine is not due to the Ca2+ influx passing through HVA Ca2+ channels.

Figure 7. Contribution of high-voltage activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels.

A, representative recording of mIPSCs in the presence of 10−4m Cd2+ to the application of nicotine. B, cumulative curve shows that nicotine increases the mIPSC frequency in the presence of Cd2+. C, the pooled data show averaged nicotinic responses in the presence of Cd2+. Each column is the mean response of five neurons expressed relative to the control frequency (without Cd2+). **P < 0.01vs. Cd2+.

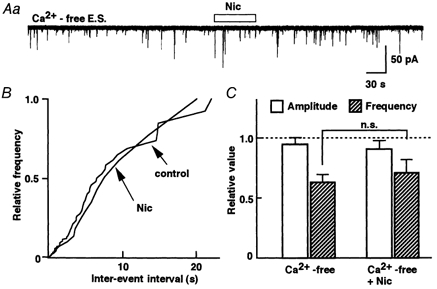

Nicotinic receptors, however, may directly allow a sufficient Ca2+ influx to promote exocytosis (Wonnacott, 1997). To investigate this possibility in SG neurons, we tested nicotine responses recorded in Ca2+-free external solutions. Ca2+-free external solution depressed mIPSC frequency to 77 % of control (P < 0.05, n = 5) without changing the mIPSC amplitude distribution (Fig. 8C). Nicotine failed to increase mIPSC frequency in the Ca2+-free external solution (Fig. 8A). This result suggests that the increase in mIPSC frequency during the application of nicotine requires Ca2+ influx passing through the nAChR-gated cation channels.

Figure 8. Dependence on external Ca2+.

A, nicotine had no effect on mIPSC frequency in Ca2+-free external solution including 2 mm EGTA. B, cumulative curve shows a complete overlap of nicotine on the mIPSC frequency distribution with control in Ca2+-free external solution. C, the pooled data are shown as the mean response relative to the control (normal external Ca2+). Each column is the mean of five neurons.

DISCUSSION

Nicotinic AChRs are broadly expressed in the CNS and are also associated with a range of regulatory functions (Lena et al. 1993). Nicotinic AChRs in presynaptic terminals facilitate the release of many neurotransmitters. The present study demonstrates that glycine release from the nerve terminals on SG neurons in the rat spinal cord is enhanced by nicotine.

Presynaptic nicotinic AChRs facilitate glycinergic transmission to SG neurons

Recently, the concept of distinct preterminal nAChRs and presynaptic nAChRs has been reported. Namely, nicotinic agonists can increase the frequency of postsynaptic currents in both TTX-sensitive and TTX-insensitive manners (see reviews, Wonnacott, 1997; MacDermott et al. 1999). The nAChRs which have been shown to induce GABA release in a TTX-sensitive manner have been referred to as ‘preterminal’ and are presumably dependent on Na+ channel mechanisms to regulate the release process (Lena et al. 1993; Wonnacott, 1997). By contrast, in the other synapses, nAChRs increase GABA, glutamate or acetylcholine release in a TTX-insensitive manner and have been referred to as ‘presynaptic’ release mechanisms (Lena & Changeux, 1997; Wonnacott, 1997).

Based on the present results, it thus appears that nicotine increases glycine release by activating nAChRs at the presynaptic level in SG neurons. Since the effect of nicotine was insensitive to TTX, the nAChRs are likely to be very close to the glycine release site. Therefore, the nAChRs studied here are classified as presynaptic rather than preterminal.

Molecular type of presynaptic nAChRs

Nicotinic AChRs can contain a variety of different subunits, some of which confer differential pharmacological sensitivity to the receptor complex. We attempted to pharmacologically identify the possible combinations of nAChR subunits, which mediate the enhancement of glycine release from glycinergic nerve terminals on rat spinal SG neurons.

Anatoxin A is a potent but relatively broad-spectrum agonist of nAChRs. This toxin is more potent in activating nAChRs comprising α4 and β2 subunits rather than homopentameric α7 nAChRs (Thomas et al. 1993). In SG neurons, anatoxin A mimicked the facilitatory action of nicotine on mIPSC frequency. In contrast, choline, a selective agonist at α7-containing nAChRs (Alkondon et al. 1999), failed to alter the mIPSC frequency. Broad-spectrum nAChR antagonists, mecamylamine and DHβE, blocked nicotine facilitation of glycine release in SG neurons (Fig. 6). Overall, the pharmacological profile supported by our results resembles the characteristics of nAChRs containing the α4 subunits but not the α7 subunits (Alkondon & Albuquerque, 1993; Seguela et al. 1993; Lena & Changeux, 1997). Immunohistochemical evidence has suggested that α4 and β2 subunits but not α7 subunits are expressed in the CNS. Furthermore, the β2 subunits appear to be associated with the α4 subunits. Moreover, both are widely expressed in the CNS (Wada et al. 1989). In the hippocampus, α-BgTx- and choline-sensitive nAChRs containing α7 subunits contribute to presynaptic facilitation of GABA release from presynaptic terminals in a TTX-sensitive manner (Alkondon et al. 1999). However, these α7-selective drugs failed to alter glycine release in SG neurons in the present study. As a result, the presynaptic nAChRs in the present preparation are likely to correspond to a single class of oligomers containing α4-β2 subunits.

Interestingly, in the lateral geniculate nucleus, both glutamate and GABA release are enhanced by distinct subtypes of presynaptic nAChRs (Guo et al. 1998). Such results have led to the suggestion that α7-containing subunits potentiate excitatory neurotransmission (McGehee et al. 1995; Gray et al. 1996; Guo et al. 1998; Radcliffe & Dani, 1998). Conversely, the activation of α4-β2-containing receptors, which are also extensively expressed in the CNS, potentiates inhibitory transmission (Lena & Changeux, 1997; Guo et al. 1998). At hippocampal interneurons, however, both the α7 and α4-β2 subunits facilitate GABA release (Alkondon et al. 1999).

Presynaptic integration of nAChR activation

The voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels at the nerve terminals are high-voltage-activated (HVA) Ca2+ channels (Meir et al. 1999). The activation of nAChRs elevates intracellular Ca2+ concentration either by depolarizing the presynaptic membrane resulting in the activating of the HVA Ca2+ channels (Vijayaraghavan et al. 1992; Rathouz & Berg, 1994; Alkondon et al. 1999), or by directly fluxing Ca2+ through the nAChR-channel complex (Mulle et al. 1992; Vernino et al. 1994; Lena & Changeux, 1997). As a result, the overall presynaptic impact of activating nAChRs appears to represent a balance between these two mechanisms. Clearly the degree of the nAChR-elicited depolarization will determine whether the presynaptic terminal potential reaches the threshold of the HVA Ca2+ channels as well as the magnitude of the Ca2+ influx via the nAChRs in the glycinergic terminals of SG neurons (Lena & Changeux, 1997).

The failure of Cd2+ to alter nicotine-induced facilitation of glycinergic transmission suggests that the HVA Ca2+ channels are not involved (Fig. 7). However, the Ca2+ influx clearly contributes to the facilitatory effect of nicotine since the response was fully abolished in the Ca2+-free external solution (Fig. 8). Nicotinic AChRs therefore mediate the facilitation of glycine release via their Ca2+ permeability, which promotes exocytosis (Mulle et al. 1992; Wonnacott, 1997). This mechanism in SG neurons contrasts with the Cd2+-sensitive nicotinic enhancement of neurotransmission seen in other synapses (Vizi et al. 1995; Soliakov & Wonnacott, 1996).

Physiological significance of presynaptic nAChRs in SG neurons

Glycine is implicated in the processing of nociceptive transmission in the SG (Yoshimura & Nishi, 1995). Nicotine obtained from tobacco could contribute to relief of pain at different levels of the CNS (see introduction).

Our present study provides interesting evidence that a presynaptic cholinergic system, acting through nAChRs, enhances glycine release from glycinergic nerve terminals projecting to the SG neurons. This might contribute to nicotinic analgesia, by facilitating this inhibitory transmission at the spinal cord level. In fact, knockout mice lacking α4 and β2 nAChR genes demonstrate a compromised antinociceptive effect for nicotine (Picciotto et al. 1998; Marubio et al. 1999). Taken together, our pharmacological results on glycinergic nerve endings that project to SG neurons along with other immunohistochemical evidence (Wada et al. 1989) suggest that α4/β2 nAChRs mediate nicotinic analgesia. In addition, nicotine induced prominent postsynaptic inward currents in some SG neurons (Fig. 3).

In conclusion, our experiments provide electrophysiological evidence that glycinergic mIPSC frequency is facilitated by nicotine. The nAChRs that exert this facilitatory effect seem likely to be localized presynaptically and to be composed of α4-β2 subunits, although the definite composition remains to be determined. Ca2+ influx appears to be required to obtain an enhancement through the nAChR-cation channel complex rather than HVA Ca2+ channels. This enhancement of glycine release might be one mechanism by which nicotine exerts its analgesic action by enhancing the inhibitory transmission in the spinal nociceptive pathways.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs A. Moorhouse and M. C. Andresen for critical reading and valuable comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by grants to N. Akaike from The Japan Health Sciences Foundation (Research on Brain Science) and Kyushu University Interdisciplinary Programs in Research Development.

References

- Akaike N, Harata N. Nystatin perforated patch recording and its applications to analyses of intracellular mechanisms. Japan Journal of Physiology. 1994;44:433–473. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.44.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akaike N, Harata N, Ueno S, Tateishi N. GABAergic synaptic current in dissociated nucleus basalis of Meynert neurons of the rat. Brain Research. 1992;570:102–108. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90569-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. Diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. I. Pharmacological and functional evidence for distinct structural subtypes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1993;265:1455–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkondon M, Pereira EF, Eisenberg HM, Albuquerque EX. Choline and selective antagonists identify two subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate GABA release from CA1 interneurons in rat hippocampal slices. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:2693–2705. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannon AW, Decker MW, Holladay MW, Curzon P, Donnelly-Roberts D, Puttfarcken PS, Bitner RS, Diaz A, Dickenson AH, Porsolt RD, Williams M, Arneric SP. Broad-spectrum, non-opioid analgesic activity by selective modulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1998;279:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5347.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges LF, Iversen SD. Topography of choline acetyltransferase immunoreactive neurons and fibers in the rat spinal cord. Brain Research. 1986;362:140–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewe J, Childs G, Kunze D. Synaptic transmission between dissociated adult mammalian neurons and attached synaptic boutons. Science. 1988;241:1810–1813. doi: 10.1126/science.2459774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends in Neurosciences. 1995;18:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray R, Rajan AS, Radcliffe KA, Yakehiro M, Dani JA. Hippocampal synaptic transmission enhanced by low concentrations of nicotine. Nature. 1996;383:713–716. doi: 10.1038/383713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JZ, Tredway TL, Chiappinelli VA. Glutamate and GABA release are enhanced by different subtypes of presynaptic nicotinic receptors in the lateral geniculate nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:1963–1969. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-01963.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. 2. Sunderland, MA, USA: Sinauer Associates; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kumazawa T, Perl ER. Excitation of marginal and substantia gelatinosa neurons in the primate spinal cord: indications of their place in dorsal horn functional organization. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1978;177:417–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.901770305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena C, Changeux JP. Role of Ca2+ ions in nicotinic facilitation of GABA release in mouse thalamus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:576–585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00576.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lena C, Changeux JP, Mulle C. Evidence for “preterminal” nicotinic receptors on GABAergic axons in the rat interpeduncular nucleus. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:2680–2688. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02680.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermott AB, Role LW, Siegelbaum SA. Presynaptic ionotropic receptors and the control of transmitter release. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1999;22:443–485. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.22.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Heath MJ, Gelber S, Devay P, Role LW. Nicotine enhancement of fast excitatory synaptic transmission in CNS by presynaptic receptors. Science. 1995;269:1692–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.7569895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Role LW. Physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by vertebrate neurons. Annual Review of Physiology. 1995;57:521–546. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LMDelMar, Arroyo-Jimenez M, Cordero-Erausquin M, Lena CLe, Novere N, De Kerchoved'Exaerde A, Huchet M, Damaj MI, Changeux JP. Reduced antinociception in mice lacking neuronal nicotinic receptor subunits. Nature. 1999;398:805–810. doi: 10.1038/19756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meir A, Ginsburg S, Butkevich A, Kachalsky SG, Kaiserman I, Ahdut R, Demirgoren S, Rahamimoff R. Ion channels in presynaptic nerve terminals and control of transmitter release. Physiological Review. 1999;79:1019–1088. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.3.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulle C, Choquet D, Korn H, Changeux JP. Calcium influx through nicotinic receptor in rat central neurons: its relevance to cellular regulation. Neuron. 1992;8:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90115-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulle C, Lena C, Changeux JP. Potentiation of nicotinic receptor response by external calcium in rat central neurons. Neuron. 1992;8:937–945. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90208-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase K, Randic M, Shirasaki T, Nakagawa T, Akaike N. Serotonin suppresses N-methyl-d-aspartate responses in acutely isolated spinal dorsal horn neurons of the rat. Brain Research. 1990;525:84–91. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Lena C, Marubio LM, Pich EM, Fuxe K, Changeux JP. Acetylcholine receptors containing the β2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature. 1998;391:173–177. doi: 10.1038/34413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe KA, Dani JA. Nicotinic stimulation produces multiple forms of increased glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:7075–7083. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07075.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathouz MM, Berg DK. Synaptic-type acetylcholine receptors raise intracellular calcium levels in neurons by two mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:6935–6945. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06935.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee JS, Ishibashi H, Akaike N. Calcium channels in the GABAergic presynaptic nerve terminals projecting to Meynert neurons of the rat. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1999;72:800–807. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee JS, Wang JM, Nabekura J, Inoue K, Akaike N. ATP facilitates spontaneous glycinergic IPSC frequency at dissociated rat dorsal horn interneuron synapses. Journal of Physiology. 2000;524:471–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro-Da-Silva A, Cuello AC. Choline acetyltransferase-immunoreactive profiles are presynaptic to primary sensory fibers in the rat superficial dorsal horn. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;295:370–384. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role LW, Berg DK. Nicotinic receptors in the development and modulation of CNS synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1077–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguela P, Wadiche J, Dineley-Miller K, Dani JA, Patrick JW. Protein, nucleotide molecular cloning, functional properties, and distribution of rat brain α7: a nicotinic cation channel highly permeable to calcium. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:596–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliakov L, Wonnacott S. Voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels involved in nicotinic receptor-mediated [3H] dopamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1996;67:163–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67010163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Stephens M, Wilkie G, Amar M, Lunt GG, Whiting P, Gallagher T, Pereira E, Alkondon M, Albuquerque EX. (+)-Anatoxin-a is a potent agonist at neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1993;60:2308–2311. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernino S, Rogers M, Radcliffe KA, Dani JA. Quantitative measurement of calcium flux through muscle and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:5514–5524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-09-05514.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayaraghavan S, Pugh PC, Zhang ZW, Rathouz MM, Berg DK. Nicotinic receptors that bind α-bungarotoxin on neurons raise intracellular free Ca2+ Neuron. 1992;8:353–362. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90301-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizi ES, Sershen H, Balla A, Mike A, Windisch K, Juranyi Z, Lajtha A. Neurochemical evidence of heterogeneity of presynaptic and somatodendritic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1995;757:84–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb17466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada E, Wada K, Boulter J, Deneris E, Heinemann S, Patrick J, Swanson LW. Distribution of alpha 2, alpha 3, alpha 4, and beta 2 neuronal nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in the central nervous system: a hybridization histochemical study in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1989;284:314–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.902840212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott S. Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Jessell TM. Primary afferent-evoked synaptic responses and slow potential generation in rat substantia gelatinosa neurons in vitro. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1989;62:96–108. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M, Nishi S. Primary afferent-evoked glycine- and GABA-mediated IPSPs in substantia gelatinosa neurones in the rat spinal cord in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1995;482:29–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]