Abstract

In this study we have investigated the action of bradykinin (Bk) on cultured neonatal rat dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells, with the aim of elucidating whether the neuronal response to Bk is influenced by association with non-neuronal satellite cells.

Bradykinin (100 nm) evoked an inward current (IBk) in 51 of 58 voltage clamped DRG neurones (holding potential (Vh) =−80 mV) that were in contact with non-neuronal satellite cells.

Bradykinin failed to evoke an inward current in isolated DRG neurones (Vh=−80 mV) that were not in contact with non-neuronal satellite cells (n = 41).

The lack of neuronal response to Bk was not influenced by time in culture. Bradykinin failed to evoke a response in isolated neurones through 1–5 days in culture. By contrast neurones in contact with satellite cells responded to Bk throughout the same time period.

Failure of isolated neurones to respond to Bk was not due to the replating procedure or to selective subcellular distribution of receptors/ion channels to the processes rather than the somata of neurones.

Using Indo-1 AM microfluorimetry Bk (100 nm) was demonstrated to evoke an intracellular Ca2+ increase (CaBk) in DRG neurones in contact with non-neuronal satellite cells and in isolated neurones.

These data suggest that the inward current response to Bk requires contact between DRG neurones and non-neuronal satellite cells. This implies an indirect mechanism of action for Bk via the non-neuronal cells, which may perform a nociceptive role. However, Bk can also act directly on the neurones, since it evokes CaBk in isolated neurones. The relationship between CaBk and the Bk-induced inward current is unknown at present.

Bradykinin (Bk) is an inflammatory mediator that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid and other painful or inflammatory conditions (Colman, 1980) where kinin-induced activation of sensory neurones may contribute to the pain associated with inflammation. Pain and hyperalgesia evoked by Bk are believed to result from an increase in firing of nociceptive sensory neurones or an increase in the sensitivity of these neurones to noxious stimuli (Dray & Perkins, 1993). It has been demonstrated that Bk binding to B2 receptors in sensory neurones induces sensitisation (Weinreich et al. 1995) which results in activation of phospholipase C, release of diacyl glycerol (DAG) and hence activation of protein kinase C (PKC) (Steranka et al. 1988; Burgess et al. 1989; Dray & Perkins, 1993). The ε form of PKC has been implicated in Bk-induced sensitisation of the nociceptive heat response (Cesare et al. 2000) and a calcium-dependent cation conductance that is indirectly activated by heat has been described in sensory neurones (Reichling & Levine, 1997).

Many types of non-neuronal cells have been demonstrated to express Bk receptors (Estacion, 1991; Cholewinski et al. 1991). Glial cells depolarise by increased Cl− conductance (De Roos et al. 1997) and display an inward current in concert with intracellular Ca2+ increase, in response to Bk (Cholewinski et al. 1991; Gimpl et al. 1992). In dorsal root ganglia (DRG), neurones are closely associated with non-neuronal satellite cells. These non-neuronal cells display Bk sensitivity, Bk acting via B2 Bk receptors to elicit a Ca2+-dependent chloride conductance and a rise in intracellular Ca2+ (England et al. 2001). We postulated therefore that the non-neuronal DRG satellite cells may influence the neuronal response to Bk. An interaction between non-neuronal cells and neurones has been demonstrated in many cell types (Parpura et al. 1994; Araque et al. 1998), including sensory neurones (Undem et al. 1993). Although the role of non-neuronal cells in the inflammatory process is unclear at present, it is reasonable to suppose that Bk acts on the DRG non-neuronal satellite cells and that these cells influence the electrical activity of the neurones by releasing chemical messages, e.g. amino acids or eicosanoids, in response to Bk.

Preliminary data have been presented previously (Heblich et al. 1999).

METHODS

Preparation of neonatal dorsal root ganglion cultures

Neonatal, 1- to 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups were killed by cervical dislocation and the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) removed. The cell dissociation and culture techniques were based on those described by Wood et al. (1988). Briefly, the ganglia were placed in Ham's F14 medium containing 0.125 % collagenase and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The ganglia were then washed 3 times with Ham's F14 containing 10 % fetal calf serum (FCS), prior to gentle trituration with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. The suspension was filtered through a 100 μm gauze strainer and spun at 800 g for 5 min. The pellet of cells was resuspended in a ‘growth medium’ consisting of Ham's F14 containing 10 % FCS and 50 ng ml−1 nerve growth factor (NGF, 2.5S). Cells were plated onto either 60 mm glass Petri dishes or poly-l-ornithine-coated glass coverslips and maintained for 1–5 days at 37 °C in a humidified incubator gassed with 3.0 % CO2. The cells were re-fed with growth medium every other day.

For recording purposes cells were gently removed from the surface of a 60 mm plate by a jet of medium from a Pasteur pipette, spun at 800 g and replated in growth medium onto poly-l-ornithine-coated glass coverslips. These coverslips were maintained under the same conditions, i.e. at 37 °C in a humidified incubator gassed with 3.0 % CO2. In some experiments coverslips were coated with laminin (5 μg ml−1). When recordings were to be made from isolated neurones (completely unassociated with satellite cells) this replating procedure was performed a minimum of 1 h in advance and recordings made from neurones 1–9 h after replating. For recordings from neurones in contact with satellite cells, replating was performed a minimum of 4 h prior to recording, to allow sufficient time for the neurones and satellite cells to become closely associated. For experiments devised to examine the effect of time in culture on neuronal responsiveness to Bk, cells were maintained in culture for 1–5 days and replated before recording. Recordings from neurones plated onto a confluent layer of satellite cells were made from neurones plated onto glass coverslips covered with a sheet of satellite cells grown from the previous dissection. In this case the neurones were replated 1 day prior to recording.

Electrophysiological recording

The whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique (Hamill et al. 1981) was used to record from neonatal rat DRG neurones, using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments Inc.). Voltage protocols and data acquisition were controlled by pCLAMP 7 software (Axon Instruments Inc.) installed on a personal computer (Siemens), interfaced to the amplifier via a Digidata 1200 A/D (Axon Instruments Inc.). Records were sampled at a rate of 0.1–12.5 kHz and filtered using a low-pass Bessel filter at 0.2 times the sampling rate. Electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass using a Brown-Flaming electrode puller (Sutter Instruments) and fire polished to give a final resistance of 2–5 MΩ.

The extracellular solution perfusing the cells consisted of (mm): 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes, 11 glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 with sodium hydroxide. Bradykinin was dissolved in distilled water and frozen in 100 μm aliquots. Bradykinin was added to the extracellular solution to give a final concentration of 100 nm and applied directly to the cell via a U-tube apparatus during recording. The test concentration of Bk was taken as 100 nm since it has been demonstrated to be close to the top of the concentration-response relationship for Bk-induced inward current in neonatal DRG neurones (EC50= 21.1 nm; McGehee et al. 1992).

All cells were voltage clamped at a holding potential (Vh) of −80 mV and recordings made at room temperature (20–22 °C). A current-voltage relationship was determined for each cell to ensure recordings were made only from neurones. Cells that did not display the large sodium/potassium currents associated with neurones were discarded. Control superfusate was applied to each cell to ensure that artefactual responses were not produced due to the proximity of the U-tube. Additionally, 30 mm KCl was applied to check that the U-tube was correctly positioned in relation to each cell. The pipette solution consisted of (mm): 110 KCl, 10 NaCl, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 2 ATP, 0.2 GTP, adjusted to pH 7.4 with potassium hydroxide.

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Indo-1 AM microfluorimetry was used to perform intracellular Ca2+ measurements. Cells were incubated in 5 μm Indo-1 AM for circa 1 h in the dark and at 37 °C to load with dye. Coverslips of loaded cells were then placed in a custom-built chamber situated on the stage of an inverted microscope equipped for measurement of epifluorescence (Nikon Diaphot 200) and perfused by a gravity feed system. The superfusate was identical to the extracellular solution used for electrophysiological recordings. In the ‘zero’ Ca2+ solution MgCl2 was increased to 2 mm, 1 mm EGTA was added and CaCl2 was omitted. Indo-1 AM was excited at 360 nm via a × 40 fluoro-objective lens and emission wavelengths of 405 and 488 nm simultaneously recorded on a pair of photomultiplier tubes (Thorn EMI). The output voltages were relayed to a custom-built ratio amplifier (Mr T. Dyett, University College London). pCLAMP 6 software running on a personal computer (Zenith 486) was used to display and record the 405 and 488 nm signals and the 405 nm/488 nm ratio.

Prior to making intracellular Ca2+ measurements from each cell, background light levels were offset by recording from an area of the coverslip in which no cells were present. To ensure that Indo-1 AM had not entered intracellular membrane delimiting compartments cells were observed to check loading was uniform and discarded if the resting ratio was unusually high. To ensure that cells from which recordings were made were neuronal, both 30 mm K+ and 0.5 μm capsaicin were applied to every cell and only those cells that displayed responses to both agents were considered.

Since all intracellular Ca2+ measurements were recorded as 405 nm/488 nm ratios, Rmin and Rmax (minimum and maximum ratio values recordable in this cell type using 5 μm Indo-1 AM with this system) were recorded to ensure data were within the measurable range of the calcium ratio. Rmin was determined by perfusing Indo-1-loaded cells with ‘zero’ Ca2+ solution containing BAPTA-AM (250 μm), for approximately 1 h. Prior to and during this period of loading with BAPTA-AM the ratio of a single neurone was monitored at 15 min intervals until no further drop in ratio was observed. Neurones were then chosen at random and ratio measurements made from each to obtain the mean Rmin value. The lowest ratio measured under these conditions was 0.39 and the mean ratio was 0.46 ± 0.01 (n = 20). Cells were perfused with a high Ca2+ (20 mm) solution to which ionomycin was added (10 μm) to determine Rmax. The highest ratio recorded under these conditions was 3.65 and the mean ratio was 3.1 ± 0.1 (n = 20).

Since the perfusion system used in these experiments included a significant deadspace, the time to onset of the Bk response was calculated by subtracting the response time to high K+ for each cell. Experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22 °C).

Data analysis

Data was analysed using the Clampfit option of pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments Inc.). Statistical comparisons were made using Student's paired or unpaired (where appropriate) t test, with P > 0.05 taken as significant (MicroCal Origin 4.1). All data are displayed as means ±s.e.m.

RESULTS

Cell configurations

Recordings were made from neonatal DRG neurones in three different configurations, either in contact with the non-neuronal satellite cells (associated neurones), completely isolated and unassociated with non-neuronal cells or plated on to a confluent layer of satellite cells.

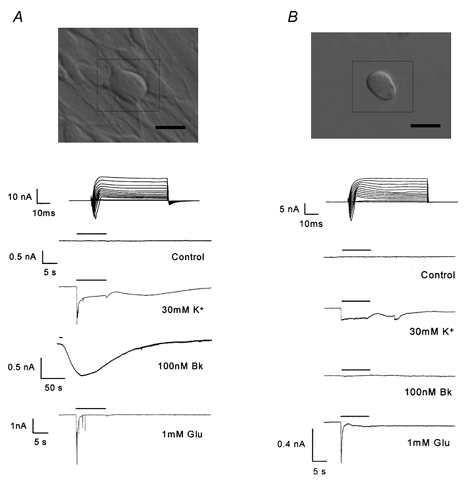

Action of Bk on neurones in contact with satellite cells

Application of Bk (100 nm) to DRG neurones in contact with non-neuronal satellite cells evoked an inward current (IBk, 358 ± 32 pA, n = 51), in 51 of 58 neurones. The IBk developed after a delay of 6.4 ± 0.6 s, reached a maximum in 55 ± 3 s and decayed with a half-time of 229 ± 18 s. These neurones were of 41.3 ± 0.8 μm mean diameter, had a mean holding current of −191 ± 22 pA and all displayed voltage-activated inward and outward currents (presumably Na+ and K+) with a mean inward current amplitude of 7.1 ± 0.5 nA. All responded rapidly to 30 mm K+, did not respond to vehicle application and when challenged, produced a response to an excitatory amino acid agonist (one or more of 1 mm glutamate (Glu), 4 μm domoate (Dom) or 200 μm kainate, Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Bradykinin evokes an inward current in DRG neurones in contact with non-neuronal satellite cells but not in isolated neurones.

Photomicrographs and recordings from two configurations of DRG neurone/satellite cells. A, DRG neurone in contact with satellite cells. B, isolated DRG neurone completely unassociated with satellite cells. The scale bars (bottom right of the photomicrographs) represent 50 μm. Top traces display current-voltage relationships elicited by 50 ms voltage pulses, incrementing in 10 mV steps between −70 and +70 mV, from a holding potential (Vh) of −80 mV. The traces below display currents elicited from a single neurone by 10 s application (represented by the horizontal bar) of reagents, Vh=−80 mV.

Responsiveness of isolated DRG neurones to Bk

Bradykinin (100 nm) failed to elicit an inward current when applied extracellularly to isolated DRG neurones (Vh=−80 mV) that were completely unassociated with non-neuronal satellite cells (n = 41). These neurones had a mean diameter of 39.8 ± 0.8 μm, a mean holding current of −151 ± 33 pA and each expressed voltage-dependent inward and outward currents, with a mean inward current amplitude of 6.8 ± 0.8 nA. The values for cell diameter, holding current and inward current amplitude were not significantly different from those of neurones in contact with non-neuronal cells (Student's unpaired t test). All responded rapidly to 30 mm K+ application and produced a response to an excitatory amino acid agonist in 95 % of cases but did not on any occasion respond to Bk (Fig. 1B).

Time in culture

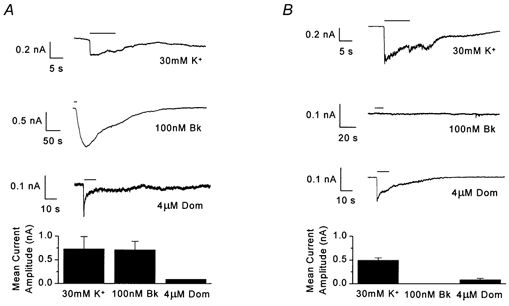

To address the possibility that the lack of Bk responsiveness in isolated neurones was due to a time-dependent sampling error, we tested the action of Bk on isolated neurones over a period of 1–5 days in culture. Maintenance of the cells in culture did not influence the action of Bk on neurones unassociated with satellite cells as Bk failed to elicit an inward current in acutely isolated neurones (day 1, Fig. 2A), through to neurones that had been maintained in culture for 5 days (Fig. 2B). Responses to glutamate (1 mm) displayed no significant difference in amplitude between different test days but high K+ responses were significantly larger (Student's unpaired t test) on day 2 compared with days 4 and 5. For each day in culture a minimum of seven neurones were tested.

Figure 2. Time in culture does not influence Bk neuronal responsiveness.

Recordings made from isolated DRG neurones on culture days 1 (A) and 5 (B) and from DRG neurones in contact with satellite cells on days 2 (C) and 5 (D) of culture. The traces show currents elicited by Bk (100 nm) application for 10 s (horizontal bar). Bar charts display the mean current amplitude elicited by application of 30 mm K+ (n≥ 7), 100 nm Bk (n≥ 7), or 1 mm glutamate (Glu, n≥ 3), for the culture days represented.

Neurones in contact with non-neuronal cells responded to Bk through culture days 2 (Fig. 2C) to 5 (Fig. 2D). The mean amplitude for IBk recorded on culture day 4 (437 ± 64 pA) was significantly (Student's unpaired t test) larger than amplitudes recorded on days 3 (256 ± 40 pA) and 5 (225 ± 40 pA). However, there were no significant differences (Student's unpaired t test) in high K+ or glutamate responses (1 mm) between culture days. Additionally, there were no significant differences in the amplitude of glutamate (1 mm) responses between isolated and associated neurones across days 2–5. The high K+ response was significantly (Student's unpaired t test) larger in associated neurones compared with isolated neurones only on day 5.

Replated neurones

Experiments were performed to ensure that the mechanical replating procedure itself did not compromise the general properties and responsiveness of the neurones. Recordings were made from replated neurones in contact with satellite cells, where Bk (100 nm) was demonstrated to elicit an inward current (713 ± 170 pA, n = 5, Fig. 3A). On the same day that these results were obtained, cells from coverslips seeded concurrently and from the same 60 mm glass Petri dish as the neurones that displayed IBk, were replated onto new coverslips. Later the same day, 1–4 h after replating, isolated neurones on these coverslips were challenged with Bk, which again failed to evoke an inward current in all cells tested (n = 5, Fig. 3B). The replated cells still expressed voltage-gated inward and outward currents and gave rapid responses to high K+ and excitatory amino acid agonists that were not significantly different (Student's unpaired t test) in amplitude from those displayed by the associated neurones.

Figure 3. The replating procedure does not compromise neuronal responsiveness.

Traces displayed for example cells demonstrating responses to 10 s applications (horizontal bar) of 30 mm K+, 100 nm Bk and 4 μm domoate (Dom). Bar charts display the mean current amplitude elicited by application of 30 mm K+ (n≥ 5), 100 nm Bk (n≥ 5) and 4 μm domoate (n≥ 2). A, recordings from DRG neurones in contact with satellite cells. B, recordings made from isolated neurones replated from coverslips that were matched to those recorded from in A.

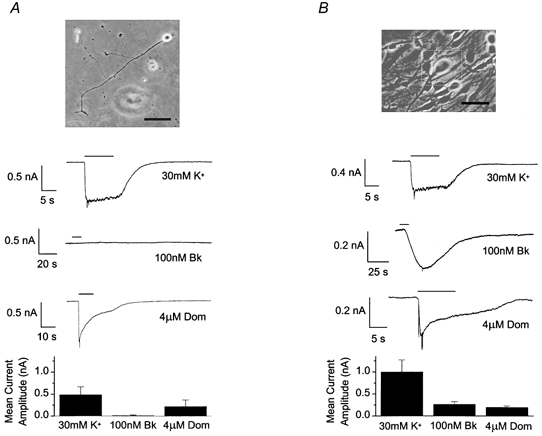

Isolated neurones with processes

The possibility that the Bk receptors/ion channels are located on the processes rather than the soma of the cell was considered. It may be that on replating of the neuronal somata the responsive part of the cell is left behind. To address this issue of location on the processes we grew cultures where neurones and non-neuronal cells developed together. All the cultures were treated with sodium arabinoside (10 μm) from approximately 1 h after replating until recordings were made, to remove the non-neuronal cells but leave the neurones intact and with processes. To encourage rapid growth of processes the coverslips were coated with laminin (5 μg ml−1). Completely isolated neurones with processes were very difficult to locate, since many non-neuronal cells remained present in the culture despite the presence of sodium arabinoside. We identified seven neurones by eye which we believed to be isolated and made recordings from them. Of these seven neurones five were completely unresponsive to Bk (100 nm), although they expressed inward and outward voltage-dependent currents and rapidly responded to both 30 mm K+ and excitatory amino acids (Fig. 4A). Two neurones displayed very small inward currents in response to Bk (38 and 67 pA).

Figure 4. Failure of Bk to produce a response is not due to location of receptors/ion channels on the processes.

Photomicrographs of and recordings from cells treated with sodium arabinoside (10 μm) and grown on laminin (5 μg ml−1)-coated coverslips. A, an isolated neurone displaying processes. B, a neurone with processes and in contact with satellite cells. The scale bars at the bottom right of the photomicrographs represent 100 μm. Traces displayed, as in Fig. 3, for example cells in each configuration. Bar charts display mean current amplitude evoked by 30 mm K+, 100 nm Bk (A, n≥ 7; B, n≥ 5) and 4 μm domoate (A, n≥ 5; B, n≥ 3).

Experiments were performed to ensure that the laminin coating on the coverslips and the presence of sodium arabinoside in the growth medium were not responsible for altering neuronal responsiveness to Bk. Since sodium arabinoside did not completely remove the non-neuronal cells it was possible to make recordings from neurones associated with non-neuronal cells, that had been cultured under exactly the same conditions as the neurones described above, i.e. plated onto laminin-coated coverslips and treated with sodium arabinoside from circa 1 h after replating until recording. In contrast to the isolated neurones with processes, all the neurones (with processes) in contact with non-neuronal cells responded to Bk (265 ± 60 pA, n = 5, Fig. 4B). High K+ and domoate produced responses in these cells that were not significantly different (Student's unpaired t test) from those evoked in the isolated neurones with processes.

Bk response of neurones plated onto a confluent layer of satellite cells

Recordings were made from neuronal somata plated on to a confluent layer of non-neuronal satellite cells. Since, if Bk evokes release of an excitatory agent from the satellite cells it would be expected to elicit an inward current in neurones in this configuration. However, the neurones appeared to adhere poorly to the satellite layer, they ‘sat’ on top of the cell layer, were easily disturbed mechanically and did not develop processes that invaded the layer of cells. Neurones recorded from in this configuration (n = 28) did respond to Bk (100 nm) but the response was much smaller (46.6 ± 10 pA) and less frequent (25 %) than in our mixed cultures. All the neurones recorded from in this configuration expressed voltage-gated inward and outward currents and rapidly responded to both high K+ and excitatory amino acid agonists.

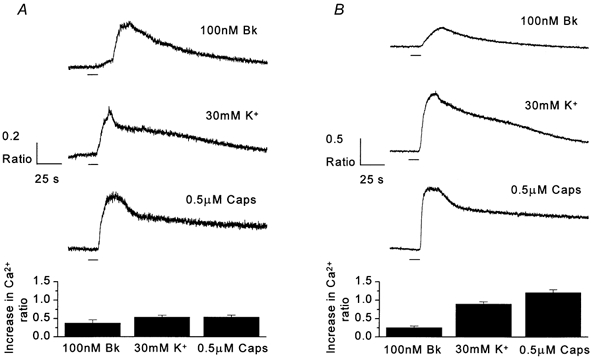

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Neurones, loaded with Indo-1 AM, that were situated in contact with non-neuronal satellite cells displayed a resting 405 nm/488 nm fluorescence ratio of 0.7 ± 0.02 (n = 13). Bradykinin application (100 nm) increased intracellular Ca2+, as indicated by a mean rise in fluorescence ratio of 0.38 ± 0.09, in all 13 neurones tested. From the start of the response the Bk-induced ratio increase (CaBk) took 22.9 ± 1.6 s to reach maximum and decayed with a half-time of 95.9 ± 8.7 s (n = 13). Only cells that responded to both high K+ (30 mm) and capsaicin (Caps, 0.5 μm) were included in this study, these agents resulting in ratio increases of 0.54 ± 0.05 and 0.55 ± 0.05 respectively (Fig. 5A).

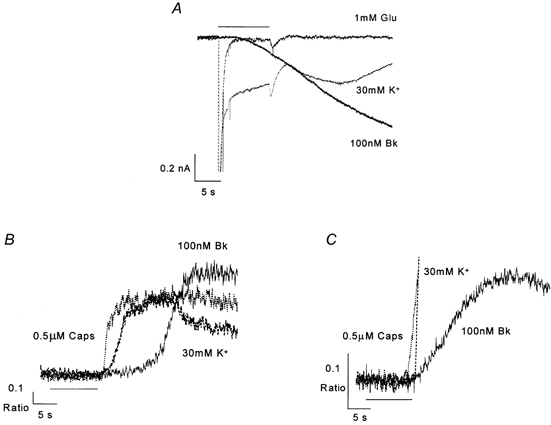

Figure 5. Bradykinin evokes CaBk in both isolated neurones and neurones in contact with satellite cells.

Traces recorded using Indo-1 AM microfluorimetry to make intracellular Ca2+ measurements from neurones in contact with non-neuronal cells (A) and isolated neurones (B). All recordings made as 405 nm/488 nm ratios (see Methods for details). Traces display rises in 405 nm/488 nm ratios in response to 10 s applications (horizontal bar) of 100 nm Bk, 30 mm K+ and 0.5 μm capsaicin (Caps), from example neurones. Bar charts represent mean increases in ratio after application of reagents (A, n = 13; B, n = 9).

The mean resting fluorescence ratio of isolated DRG neurones that were completely unassociated with non-neuronal satellite cells was 0.67 ± 0.03 (n = 9). In contrast to results obtained using electrophysiological recording techniques, where 100 nm Bk failed to elicit a response (inward current) in any isolated neurone, 100 nm Bk application produced a response in all the Indo-1 AM-loaded isolated neurones tested, giving a mean increase in fluorescence ratio of 0.26 ± 0.04 (n = 9, Fig. 5B). This value is not significantly different from the ratio increase produced by Bk (0.38 ± 0.09) in neurones in contact with non-neuronal satellite cells (Student's unpaired t test). Bradykinin responses took 24.8 ± 1.6 s to reach a maximum from the beginning of the ratio rise and decayed with a half-time of 96.2 ± 6.6 s. Ratio rises of 0.90 ± 0.06 and 1.21 ± 0.08 were produced by 30 mm K+ and 0.5 μm capsaicin, respectively.

Onset of Bk response

We measured the delay to onset for IBk and for CaBk in associated neurones. The response to Bk was always slower than the response to high K+ for either measurement. Onset of the IBk response was slower than the current response to high K+ by 6.2 ± 0.6 s (n = 51, Fig. 6A). The CaBk response was 5.4 ± 1.5 s (n = 13) later in onset than the calcium ratio rise in response to high K+ (Fig. 6B). These delays in onset were not significantly different (Student's unpaired t test).

Figure 6. Delay to onset of Bk responses in DRG neurones.

A, superimposed inward currents elicited from a single DRG neurone in contact with satellite cells by application (horizontal bar) of drugs, Vh=−80 mV. B and C, rise in intracellular Ca2+ in response to drug application (horizontal bar) in a DRG neurone in contact with satellite cells (B) and an isolated neurone (C). Note that traces for glutamate and high K+ in A and capsaicin and high K+ in C are truncated in order to focus on the delay in onset.

Surprisingly, CaBk in isolated neurones was delayed with respect to the high K+ response by only 0.4 ± 0.6 s (n = 8, Fig. 6C), which is significantly shorter than the latencies for either IBk or CaBk (Student's unpaired t test) in associated neurones. The time from the start to the peak of the calcium ratio rise in response to high K+, capsaicin or Bk was not significantly different between associated and isolated neurones.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we have shown that sensory neuronal responsiveness to Bk is influenced by the proximity of the neurones to non-neuronal satellite cells. The satellite cells are not a prerequisite for Bk sensitivity since Bk provokes an increase in intracellular Ca2+ (CaBk) in the neurones whether or not they are in contact with (associated neurones) satellite cells. However, the inward current response to Bk (IBk) – a predicate of acute excitation – is seen only in associated neurones. These data imply a role for non-neuronal DRG cells in nociception.

Our observations agree with those of several groups who have shown that Bk increases intracellular Ca2+ in DRG neurones (Bleakman et al. 1990; Stucky et al. 1996; Smith et al. 2000). We also concur with those who have found that Bk does not evoke an inward current in adult DRG neurones unless it is applied as part of a ‘cocktail’ of inflammatory mediators (Kress et al. 1997; Vyklicky et al. 1998). On the other hand, our observations are not in agreement with those studies which have presented evidence that Bk evokes an inward current in isolated DRG neurones (Burgess et al. 1989; McGehee et al. 1992; Nicol & Cui, 1994; Cesare & McNaughton, 1996; Vyklicky et al. 1999). We are confident that our recordings were made from healthy neuronal cells, since the neurones had a relatively low ‘leak’ current, displayed a full range of voltage-dependent currents and were responsive to high K+ and amino acids (glutamate, domoate and/or kainate). So far as we can determine there were no consistent differences between the methods that we have used for cell preparation, electrophysiological recording (including recipes for pipette and superfusate solutions) and those used in the studies mentioned above. Interestingly, all but one (Cesare & McNaughton, 1996) of the above groups who report inward current responses to Bk have used cell preparations treated with mitotic inhibitors (e.g. cytosine arabinoside or fluorodeoxyuridine). By contrast, in most of our experiments we have relied on physiological criteria to identify neurones and visual inspection to ensure that neuronal somata were free of processes and not in contact with satellite cells. McGuirk & Dolphin (1992) whose results are consistent with ours in that they could not detect somatic responses to Bk, used a simple replating method to reduce the satellite cell population in their preparation. It is unlikely that the presence of mitotic inhibitors alone would enable neurones to respond to Bk with an inward current and, anyway, it is clear from our data that this is not the case. A more likely conclusion is that a simple reduction of the number of dividing cells in a culture with mitotic inhibitors is not sufficient to eliminate the influence of satellite cells on neuronal responsiveness.

When neurones were allowed to grow in contact with satellite cells application of Bk resulted consistently in an inward current. The characteristics of the current were similar to those described by others for sensory neuronal responses to Bk (Burgess et al. 1989; McGehee et al. 1992; Nicol & Cui, 1994; Cesare & McNaughton, 1996) except that the amplitude of IBk recorded in our experiments was usually larger.

We have been especially careful to consider possible artefact sources that could give rise to the differences between our data and that of others, i.e. the lack of Bk-induced IBk in our experiments with isolated neurones. We addressed the possibility that the lack of Bk responsiveness in isolated neurones was due to a time-dependent sampling error, since Bk responsiveness may take a few days to develop in culture (Segond Von Banchet et al. 1996). In our hands associated neurones were responsive to Bk throughout the period they were grown in culture (2–5 days) although there were some time-dependent variations in the mean amplitude of IBk. However, apart from these changes in amplitude time in culture did not appear to affect Bk responsiveness per se. In contrast Bk failed to evoke IBk in isolated neurones through culture days 1–5. The complete absence of Bk-induced inward currents in isolated neurones cannot therefore be explained by a time-dependent sampling error.

Artefacts that might arise from the mechanical trauma that occurs during replating (to isolate the neuronal somata) are also unlikely to explain the absence of IBk since the isolated cells were otherwise unaffected and responded normally to excitatory amino acids and demonstrated a full range of voltage-activated ionic currents. Furthermore, in cells that had not been replated and which retained their processes IBk was almost eliminated when the influence of satellite cells was minimised by application of mitotic inhibitors. The absence of IBk is unlikely to be an artefact of our experimental conditions.

Our data strongly suggest that the close proximity of non-neuronal cells is a pre-requisite for neuronal Bk responsiveness at least with respect to changes in membrane conductance. A variety of non-neuronal cells, including fibroblasts (Estacion, 1991) and astrocytes (Cholewinski et al. 1991), have been demonstrated to express Bk receptors. Bradykinin has been demonstrated to act on DRG satellite cells, eliciting a Ca2+-activated chloride current by activation of B2 receptors (England et al. 2001). It is therefore possible that Bk acts directly on the satellite cells via B2 receptors and evokes release of, for example, amino acids and/or eicosanoids from the satellite cells which then act directly on the neurones, mediating or potentiating the inward current. IBk observed in associated neurones is consistently slower and significantly later in onset than responses to either high K+ or to amino acids – characteristics of the Bk response that concur with those reported by others (McGehee et al. 1992; Cesare & McNaughton, 1996). The late onset of the response is consistent with an indirect Bk action, as Bk would first have to act on the satellite cells evoking release of an agent that then acts on the neurones. Interestingly, Bk-evoked release of amino acids has been demonstrated from non-neuronal DRG Schwann cell cultures (Parpura et al. 1995). Preliminary experiments in our laboratory suggest, however, that ecosanoids rather than amino acids are involved as mediators of the Bk-induced response (Heblich & Docherty, 2000) in DRG but further work is required to confirm these data.

If IBk is due to Bk-evoked release of an excitatory agent from non-neuronal cells we would expect that isolated neuronal somata replated on to a confluent layer of non-neuronal cells would show a response to Bk. However, neurones replated onto such a layer responded less frequently (25 %) to Bk and with a much smaller current (46.6 ± 10 pA, n = 7 of 28 cells tested) than in normal mixed cultures, though data were comparable to published accounts of Bk responses (McGehee et al. 1992; Nicol & Cui, 1994). We noticed that the neurones adhered poorly to the confluent layer of non-neuronal cells, and remained spherical with no outgrowth of processes. This implies that close contact between membranes is required and that Bk responsiveness depends on an adhesion interaction or, conceivably, an excitatory chemical agent that is released from the non-neuronal cells and which may be strongly lipophilic or is immediately diluted by the superfusing medium.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the present study is the fact that there is a clear dissociation between neuronal membrane conductance responses to Bk and intracellular Ca2+ responses with respect to the influence of satellite cells. We are confident that the Bk-evoked rise in intracellular Ca2+ and associated increase in Ca2+-activated Cl− current in DRG satellite cells is mediated by B2 receptors (England et al. 2001). Given that the Bk-induced inward current in DRG neurones is a cation conductance (Burgess et al. 1989), the mechanism and the receptors involved could be completely different in neurones and in satellite cells. It will be important to establish whether the different types of neuronal responses to Bk are mediated by a single receptor type or whether different receptors are involved. Unlike the IBk and CaBk responses in associated neurones, surprisingly CaBk in isolated neurones showed no appreciable delay to onset. We know that this response must be due to a direct action of Bk on the neurones (since the neurones are not in contact with satellite cells) but the absence of a delay suggests that the mechanism of the response may be different from the response in associated neurones. IBk could be identical to the heat-sensitive (Reichling & Levine, 1997) Ca2+-activated cation conductance that has been demonstrated in DRG neurones (Ayar et al. 1999). If this is the case then the influence of the non-neuronal cells on Bk responses may depend on regulation of neuronal Ca2+-activated cation channels. Bradykinin has also been shown to activate heat-sensitive ion channels (Cesare & McNaughton, 1996) that have similar characteristics to vanilloid-gated ion channels (Tominaga et al. 1998), via a protein kinase C-mediated mechanism (Cesare et al. 2000). Conceivably, the expression of this type of ion channel activity might be dependent on non-neuronal cells. Insufficient information is available concerning the nature of IBk and its pharmacology to speculate further. Whatever the molecular target(s) in neurones, our data suggest that regulation of IBk by the non-neuronal satellite cells is fast and reversible since neurones lose their IBk after dissociation.

In conclusion, IBk in the somata of neonatal DRG neurones are dependent on a close association between the neurones and satellite cells. If similar mechanisms are present in adult neurones and their processes then this could represent an important, novel mechanism that regulates the chemical sensitivity of primary afferent neurones. Since Bk is an important inflammatory mediator, these data imply a role for non-neuronal cells as nociceptors.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Dr Jon Robbins for his advice and use of the Indo-1 microfluorimetry equipment. Financial support for this work was provided by the Wellcome Trust (053230/Z97/Z/JRS/JP/JAT).

References

- Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG. Glutamate-dependent astrocyte modulation of synaptic transmission between cultured hippocampal neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;10:2129–2142. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayar A, Storer C, Tatham EL, Scott RH. The effects of changing intracellular Ca2+ buffereing on the excitability of cultured dorsal root ganglion neurones. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;271:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakman D, Thayer SA, Glaum SR, Miller RJ. Bradykinin-induced modulation of calcium signals in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons in vitro. Molecular Pharmacology. 1990;38:785–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess GM, Mullaney I, McNeill M, Dunn PM, Rang HP. 2nd messengers involved in the mechanism of action of bradykinin in sensory neurons in culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1989;9:3314–3325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-09-03314.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P, Dekker LV, Sardini A, Parker PJ, McNaughton PA. Specific involvement of PKC-e in sensitization of the neuronal response to painful heat. Neuron. 2000;23:617–624. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80813-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesare P, McNaughton P. A novel heat-activated current in nociceptive neurons and its sensitization by bradykinin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1996;93:15435–15439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholewinski AJ, Stephens G, McDermott AM, Wilkin GP. Identification of B2 bradykinin binding-sites on cultured cortical astrocytes. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1991;57:1456–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman RW. Patho-physiology of the kallikrein system. Annals of Clinical Laboratory Science. 1980;10:226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Roos ADG, Van Zoelen EJJ, Theuvenet PR. Membrane depolarization in NRK fibroblasts by bradykinin is mediated by a calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1997;170:166–173. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199702)170:2<166::AID-JCP8>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray A, Perkins M. Bradykinin and inflammatory pain. Trends in Neurosciences. 1993;16:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England S, Heblich F, James IF, Robbins J, Docherty RJ. Bradykinin evokes a calcium-activated chloride current in non-neuronal satellite cells isolated from neonatal dorsal root ganglion. Journal of Physiology. 2001;530:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0395k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estacion M. Acute electrophysiological responses of bradykinin-stimulated human fibroblasts. Journal of Physiology. 1991;436:603–620. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpl G, Walz W, Ohlemeyer C, Kettenmann H. Bradykinin receptors in cultured astrocytes from neonatal rat-brain are linked to physiological responses. Neuroscience Letters. 1992;144:139–142. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90735-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Archiv. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heblich F, Docherty RJ. An investigation of the possible indirect mechanisms for bradykinin (Bk) induced inward current I(Bk) in neonatal rat dorsal root ganglion neurones in culture. Journal of Physiology. 2000;523.P:156P. [Google Scholar]

- Heblich F, England S, Guidato S, Docherty RJ. On the responsiveness of cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons to bradykinin. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1999;25:897.11. [Google Scholar]

- Kress M, Reeh PW, Vyklicky L. An interaction of inflammatory mediators and protons in small diameter dorsal root ganglion neurons of the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;224:37–40. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGehee DS, Goy MF, Oxford GS. Involvement of the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP pathway in the desensitization of bradykinin responses of cultured rat sensory neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:315–324. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90170-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuirk SM, Dolphin AC. G-protein mediation in nociceptive signal transduction — an investigation into the excitatory action of bradykinin in a subpopulation of cultured rat sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;49:117–128. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90079-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol GD, Cui M. Enhancement by prostaglandin E2 of bradykinin activation of embryonic rat sensory neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1994;480:485–492. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Basarsky TA, Liu F, Jeftinija K, Jeftinija S, Haydon PG. Glutamate-mediated astrocyte neuron signalling. Nature. 1994;369:744–747. doi: 10.1038/369744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Liu F, Jeftinija KV, Haydon PG, Jeftinija SD. Neuroligand-evoked calcium-dependent release of excitatory amino-acids from schwann-cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:5831–5839. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05831.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichling DB, Levine JD. Heat transduction in rat sensory neurones by calcium-dependent activation of a cation channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:7006–7011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segond Von Banchet GS, Petersen M, Heppelmann B. Bradykinin receptors in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion cells: Influence of length of time in culture. Neuroscience. 1996;75:1211–1218. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JAM, Davis CL, Burgess GM. Prostaglandin E2-induced sensitisation of bradykinin-evoked responses in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones is mediated by camp-dependent protein kinase A. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12:3250–3258. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steranka LR, Manning DC, Dehaas CJ, Ferkany JW, Borosky SA, Connor JR, Vavrek RJ, Stewart JM, Snyder SH. Bradykinin as a pain mediator: receptors are localised to sensory neurones and antagonists have analgesic actions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1988;85:3245–3249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stucky CL, Thayer SA, Seybold VS. Prostaglandin E(2) increases the proportion of neonatal rat dorsal root ganglion neurons that respond to bradykinin. Neuroscience. 1996;74:1111–1123. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron. 1998;21:531–543. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem BJ, Hubbard W, Weinreich D. Immunologically induced neuromodulation of guinea pig nodose ganglion neurons. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1993;44:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyklicky L, Knotkovaurbancova H, Vitaskova Z, Vlachova V, Kress M, Reeh PW. Inflammatory mediators at acidic pH activate capsaicin receptors in cultured sensory neurons from newborn rats. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:670–676. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyklicky L, Vlachova V, Vitaskova Z, Dittert I, Kabat M, Orkland RK. Temperature coefficient of membrane currents induced by noxious heat in sensory neurones in the rat. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:181–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0181z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich D, Koschorke GM, Undem BJ, Taylor GE. Prevention of the excitatory actions of bradykinin by inhibition formation in nodose neurones of the guinea-pig. Journal of Physiology. 1995;483:735–746. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JN, Winter J, James IF, Rang HP, Bevan S. Capsaicin-induced ion fluxes in dorsal-root ganglion-cells in culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:3208–3220. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-09-03208.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]