Abstract

Recombinant rat GABAA (α1β2, α1β2γ2, β2γ2) and human GABAC (ρ1) receptors were expressed in Xenopus oocytes to examine the effect of ultraviolet (UV) light on receptor function.

GABA-induced currents in individual oocytes expressing GABA receptors were tested by two-electrode voltage clamp before, and immediately after, 312 nm UV irradiation.

UV irradiation significantly potentiated 10 μm GABA-induced currents in α1β2γ2 GABA receptors. The modulation was irradiation dose dependent, with a maximum potentiation of more than 3-fold.

The potentiation was partially reversible and decayed exponentially with a time constant of 8.2 ± 1.2 min toward a steady-state level which was still significantly elevated (2.7 ± 0.3-fold) compared to the control level.

The effect of UV irradiation on GABAA receptors varied with receptor subunit composition. UV irradiation decreased the EC50 of the α1β2, α1β2γ2 and β2γ2 GABAA receptors, but exhibited no significant effect on the ρ1 GABAC receptor.

UV irradiation also significantly increased the maximum current 2-fold in α1β2 GABAA receptors with little effect on the maximum of α1β2γ2 (1.1-fold) or β2γ2 (1.1-fold) GABAA receptors.

The effect of UV irradiation on GABAA receptors did not overlap the effect of the GABA receptor- allosteric modulator, diazepam.

The UV effect on GABAA receptors was not prevented by the treatment of the oocytes before and during UV irradiation with one of the following free-radical scavengers: 40 mmd-mannitol, 40 mm imidazole or 40 mm sodium azide. In addition, the effect was not mimicked by the free-radical generator, H2O2.

Potential significance and mechanism(s) of the UV effect on GABA receptors are discussed.

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA)-gated chloride channels mediate fast inhibitory synaptic transmission, thereby controlling neuronal excitability. These chloride channels can be classified into GABAA and GABAC receptors according to their pharmacological properties. GABAA receptors are allosterically modulated by benzodiazepines, barbiturates and neurosteroids, and antagonized by bicuculline, whereas GABAC receptors are insensitive to these compounds (Woodward et al. 1992; Feigenspan et al. 1993; Qian & Dowling, 1993; Macdonald & Olsen, 1994; Johnston, 1996; Lukasiewicz, 1996; Ueno et al. 1997). These two types of GABA receptors also differ in their physiological properties and distribution. For example, GABAA receptors have fast activation and deactivation kinetics and show significant desensitization during prolonged agonist exposure, whereas GABAC receptors have slow kinetics without significant desensitization (Cutting et al. 1991, Amin & Weiss, 1994). While GABAA receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system and retina, GABAC receptors are mainly localized in the retina (Enz et al. 1995, 1996; Yeh et al. 1996; Albrecht et al. 1997; Wegelius et al. 1998).

Molecular cloning has revealed several GABA-gated ion channel subunits and their isoforms α1–6, β1–4, γ1–3, ρ1–3, δ, ε, π and χ (Barnard et al. 1987; Schofield et al. 1987; Khrestchatisky et al. 1989; Olsen & Tobin, 1990; Cutting et al. 1991; Garret et al. 1997; Hedblom & Kirkness, 1997; Whiting et al. 1997). The exogenous expression of GABA receptors simplifies studies by avoiding the complication of heterogeneous populations of GABA receptor subtypes in the same cell. Such studies have revealed that the distinct physiological and pharmacological properties of GABAA and GABAC receptors are due to the differences in their subunit compositions. Recombinant αβγ GABA receptors have pharmacological and physiological properties similar to native GABAA receptors (Levitan et al. 1988; Pritchett et al. 1989; Malherbe et al. 1990; Sigel et al. 1990; Verdoorn et al. 1990), whereas exogenously expressed ρ1 homomeric GABA receptors have properties similar to native GABAC receptors (Cutting et al. 1991). The distinct pharmacological properties and spatial distribution for receptors with different subunit composition is the basis for developing subunit-specific therapeutic approaches for the treatment of insomnia, epilepsy and other neurological disorders.

In this study, we observed that UV irradiation has differential effects on recombinant GABAA and GABAC receptors. α1β2, β2γ2 and α1β2γ2 GABA receptors can be potentiated by UV irradiation whereas ρ1 GABA receptors are insensitive to UV light. The potentiation of GABAA receptors by UV irradiation does not overlap with the effect of the GABAA receptor-allosteric modulator, diazepam. The elucidation of the molecular mechanism could facilitate the identification of new structural element(s) crucial for GABAA receptor function. It could also help us to understand the pathophysiology of UV-induced retina damage, and facilitate the development of strategies to prevent or reverse the damage.

METHODS

cDNA and cRNA preparation

cDNAs encoding rat GABA receptor subunits α1, β2 and γ2L were cloned into pAlter-1 in the SP6 orientation (Amin et al. 1994) and the human ρ1 GABA receptor subunit was cloned into pAlter-1 in the T7 orientation (Amin & Weiss, 1994). The cDNAs were linearized by Ssp I (α, β and γ) or Nhe I (ρ1). cRNAs were transcribed by standard in vitro transcription protocols. Briefly, RNase-free DNA templates were prepared by treating linearized DNA with proteinase K. The cRNAs then were transcribed by SP6 RNA polymerase (α, β and γ subunits) or T7 RNA polymerase (ρ1 subunit). After degradation of the DNA template by RNase-free DNase I, the cRNAs were purified and resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. cRNA yield and integrity were examined on a 1 % agarose gel.

Oocyte preparation and receptor expression

Female Xenopus laevis (Xenopus I, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) were anaesthetized by 0.2 % MS-222 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). The ovarian lobes were surgically removed from the frog and placed in calcium-free OR2 incubation solution consisting of (mm): 92.5 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 Na2HPO4, and 5 Hepes; plus 50 U ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin, pH 7.5. The frog was then allowed to recover from surgery before being returned to the incubation tank. After the third surgery, the frog was killed by decapitation while still under anaesthesia. This procedure was carried out in accordance with the rules and regulations set forth by the UAB Animal Care Committee. The ovarian lobes were cut into small pieces, and digested with 0.3 % Collagenase A (Boehringer-Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with constant stirring at room temperature for 1.5–2 h. The dispersed oocytes were thoroughly rinsed with the above solution plus 1 mm CaCl2. The stage VI oocytes were selected and the follicular layer (if still present) was manually removed with fine forceps. The oocytes were incubated at 18 °C before injection.

Micropipettes for cRNA injection were pulled from borosilicate glass (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA, USA) on a Sutter P87 horizontal puller, and the tips were cut with forceps to ∼40 μm in diameter. The cRNA, with proper dilution in DEPC-treated water, was drawn up into the micropipette and injected into oocytes with a Nanoject micro-injection system (Drummond Scientific) at a total volume of 20–60 nl.

Electrophysiology

One to three days after cRNA injection, the oocyte was placed in a 100 μl chamber with continuous OR2 perfusion. The oocytes were voltage clamped at −70 mV to measure GABA-induced currents using a GeneClamp 500 (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). The OR2 was used as an extracellular solution, which consisted of the following (mm): 92.5 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 5 Hepes, pH 7.5.

Ultraviolet irradiation

After recording control GABA-induced currents, each oocyte was taken out of the recording chamber and placed onto a FBTIV-614 transilluminator (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Except for the UV dose-response experiments, the oocyte was irradiated by UVB (312 nm) at 8 mW cm−2 for 1 min. The oocyte was then placed back into the recording chamber to assess the UV effect with the same set of GABA concentrations. For spectral response comparison, an ELC-403 UV curing light gun (Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ, USA) emitting UVA (340–380 nm, peak at 365 nm) with a minimum output of 40 mW cm−2 at 2.54 cm distance (Edmund Optics) was used. The oocyte was taken out of the recording chamber and placed onto a fused silica glass window mounted in the bottom of a Petri dish. The UV gun was directed from the bottom of the fused silica glass window for 1 min at the oocyte. For visible light stimulation, an illuminator with an EKE type 150 W halogen lamp (Southern Micro Instruments, Marietta, GA, USA) was used with a fibre optic guide pointed towards the oocyte in the recording chamber. After voltage clamping the oocyte, all the lights were turned off for 10 min and a 3 μm GABA-induced current was monitored at 5 min intervals before and after a 5 min exposure to light at 80 % of the maximum intensity.

Drug preparation

GABA (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) stock solution (100 mm) was prepared daily from the solid form. Diazepam (Sigma) stock solution (50 mm) was prepared in DMSO and stored at −20 °C. Imidazole (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), d-mannitol (Sigma) and sodium azide (Sigma) solutions were freshly prepared from the solid form. The H2O2 solution was freshly diluted before use (J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA).

Data analysis

The dose-response relationship of the GABA-induced current in recombinant GABAA or GABAC receptors before and after UV irradiation was analysed by a least-squares fit to the following Hill equation:

|

(1) |

where the GABA-induced current (I) is a function of the GABA concentration, EC50 is the GABA concentration required for inducing a half-maximal current, nh is the Hill coefficient, and Imax is the maximum current. The maximum current was then used to normalize the dose-response curve for each individual oocyte. For the GABA dose-response relationship after UV irradiation, the normalization was achieved by using the maximum current before irradiation. The average of the normalized currents for each GABA concentration was used to plot the data. All the data are presented as means ±s.e.m. (standard error of the mean).

The UV irradiation dose-dependent potentiation was normalized as follows:

| (2) |

where the fraction of potentiation, P, was calculated from the current response before (Icontrol) and after (IUV) UV exposure. The potentiation data were least squares fitted with the Hill equation in the following form:

|

(3) |

where the percentage potentiation P is a function of the time of UV irradiation. The ED50 is the time required for 50 % of the maximum potentiation.

For the recovery of the UV effect, the following exponential equation was used:

| (4) |

where the 10 μm GABA-induced current (I) was measured repeatedly at 10 min intervals. I0 is the current amplitude immediately after UV exposure (time zero) and IS is the steady-state level of potentiation (i.e. the irreversible component).

RESULTS

UV irradiation potentiated GABA-induced currents in recombinant GABAA receptors

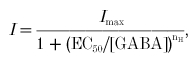

Figure 1A shows that the GABA-induced current (10 μm GABA) in an oocyte expressing α1β2γ2 GABA receptors can be potentiated by 1 min UV irradiation using a transilluminator (left). The GABA-induced current did not change in control oocytes placed on the same surface, but without UV irradiation (right). Note that the GABA-induced current trace shows no desensitization before UV irradiation. After UV irradiation, however, the increased current shows some desensitization, suggesting an increase in GABA sensitivity. Figure 1B is a bar graph presentation of the averaged data from three oocytes.

Figure 1. UV irradiation potentiated GABA-induced currents (10 μm GABA) in oocytes expressing α1β2γ2 GABA receptors.

A, left, the GABA-mediated current (10 μm GABA) was potentiated 3.0 ± 0.3-fold upon UV irradiation for 1 min on a transilluminator (n = 3). Right, in contrast, no potentiation was observed (1.0 ± 0.0) after 1 min on the transilluminator with the UV lamp off (n = 3). B, averaged data presented as a bar graph.

UV enhancement of the GABA-induced current was dose dependent

Since we could not accurately vary the UV intensity to test the dose-response relationship, we varied the exposure time at a fixed intensity. Figure 2A shows that the increase in the GABA-induced current (10 μm GABA) in oocytes expressing α1β2γ2 GABA receptors is irradiation dose dependent. The ED50 (half-saturation dose) was 12.4 s × intensity (max) with a Hill coefficient of 1.8 (Fig. 2B). Since the effect was observed in different oocytes for each exposure time, the large variability precluded a detailed analysis of the dose-response relationship (i.e. the significance of the co-operative Hill coefficient). Nevertheless, the dependence of the potentiation of the GABA-induced current on the UV exposure time further confirms that UV irradiation can potentiate GABAA receptors.

Figure 2. The effect of UV irradiation on recombinant GABAA receptors was irradiation dose dependent.

A, the normalized current traces before and immediately after UV irradiation. The UV dose was controlled by varying the exposure time as indicated with a fixed intensity (maximum, see Methods). Each oocyte was exposed to UV irradiation only once. B, the difference in the currents before and after UV irradiation for each oocyte was calculated and normalized to its own control (before UV). Each data point is the average of three oocytes. The continuous line is the least-squares fit to the averaged data points using eqn (3). The fit resulted in an EC50 of 12.4 s × intensity(max) and a Hill coefficient of 1.8.

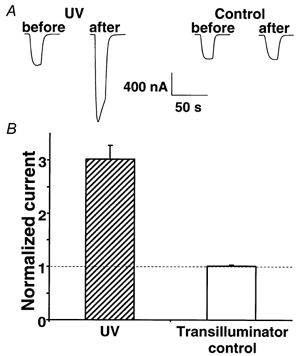

The UV effect on GABAA receptors was partially reversible

Figure 3 shows that immediately after UV irradiation, the GABA-induced current in α1β2γ2 GABA receptors was potentiated 3.4 ± 0.2-fold (n = 3). However, when we monitored the current for 1 h, the amplitude decreased as a single exponential toward a steady-state level which was still 2.7 ± 0.3-fold higher than the control value. The time constant of the decay was 8.2 ± 1.2 min. Long term monitoring can be complicated by changes in expression level. New GABA receptor expression will result in a mixed population of UV-irradiated and non-irradiated GABA receptors. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of a much slower component of recovery than that observed in Fig. 3. Nevertheless, these data suggest that the UV effect on GABAA receptors was only partially reversible.

Figure 3. UV-mediated potentiation of GABA-induced currents on α1β2γ2 GABA receptors was partially reversible.

A, examples of current traces before and after UV irradiation with a 1 min exposure at the maximum intensity (see Methods). A 10 μm GABA test pulse was applied every 10 min. The potentiation decreased over time as a single exponential. B, the normalized (to control current) and averaged 10 μm GABA-test pulse was plotted against time. The fitting of the data points to eqn (4) resulted in a time constant of 8.2 ± 1.2 min (n = 3). Note that the GABA-induced current slowly decreased in amplitude towards a steady-state level, which was still significantly elevated (2.7 ± 0.3-fold).

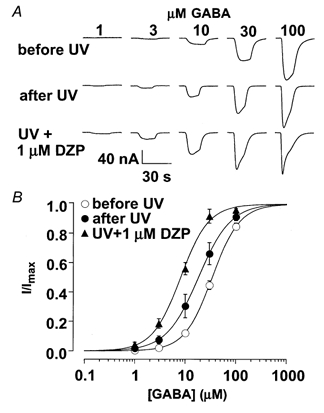

UV irradiation shifts the GABA dose-response curve to the left for GABAA, but not GABAC, receptors

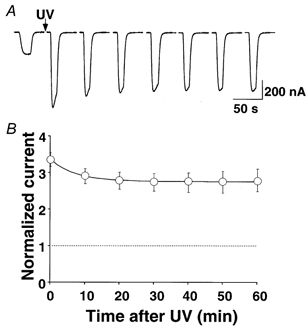

Since 10 μm GABA was not a saturating concentration for α1β2γ2 GABA receptors, the increase in GABA-induced current could be due to an increase in sensitivity to GABA or to an increase in the maximum current (maximum-open probability or single-channel conductance) or both. This question can be addressed by comparing dose- response relationships before and after UV irradiation. Note that due to the slow recovery process, the dose- response relationship constructed by multiple GABA concentrations tested over about 15 min would be partially recovered. Nevertheless, Fig. 4A shows that the α1β2γ2 GABA receptor dose-response relationship was shifted by UV irradiation to the left by about 2-fold (from 44.2 ± 5.7 to 23.2 ± 5.4 μm). The maximum current, however, was only slightly increased by UV irradiation. A similar EC50 shift without a significant change in the maximum was observed for β2γ2 GABA receptors (Fig. 4B). For α1β2 receptors, UV irradiation significantly increased the maximum current (2-fold), and decreased the EC50 (Fig. 4C). In contrast to α1β2γ2, β2γ2, and α1β2 receptors, homomeric ρ1 GABAC receptors were insensitive to UV irradiation (Fig. 4D). The maximum current, EC50 and Hill coefficients before and after UV irradiation are listed in Table 1.

Figure 4. The effect of UV irradiation on the GABA dose-response curve of GABA receptors.

A, examples of current traces induced by a range of GABA concentrations before and after UV irradiation. The average of the normalized current was plotted against GABA concentration. Continuous lines are from least-squares fits of the data points to eqn (1). The resulting EC50 values and Hill coefficients are listed in Table 1. Note that UV irradiation shifted the GABA dose-response curve to the left about 2-fold, without a significant change in the maximum current. B and C, similar to A, but for β2γ2 and α1β2 GABAA receptors. Note that for α1β2, UV irradiation shifted the GABA dose-response curve to the left ∼3.8-fold, as well as increased the maximum current (∼2-fold). D, in contrast to α1β2γ2, β2γ2 and α1β2 receptors, homomeric ρ1 GABAC receptors were insensitive to UV irradiation.

Table 1. UV effect on dose–response relationships of recombinant GABAA and GABAC receptors.

| Before UV | After UV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subunit combinations | Imax (nA) | EC50 (μm) | Hill coeff | Imax (nA) | EC50 (μm) | Hill coeff | Number of oocytes |

| α1β2γ2 | 922 ± 460 | 44.2 ± 3.3 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1093 ± 601 | 23.2 ± 3.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 3 |

| α1β2 | 178 ± 77 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 375 ± 200 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 3 |

| β2γ2 | 380 ± 91 | 51.3 ± 9.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 400 ± 103 | 25.1 ± 2.8 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 4 |

| ρ1 | 182 ± 91 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 197 ± 96 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 3 |

The UVA or visible light did not significantly potentiate GABAA receptors

Since GABAA receptors can be modulated by UV, it is possible that they might be modulated by other wavelengths of light. To test this possibility, we examined the effects of visible light and UVA (340–380 nm) on α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors. Oocytes were placed in the dark for 10 min and then exposed to visible light for 5 min. At the end of this 5 min exposure, the current amplitude in response to 3 μm GABA (normalized to control) was 1.02 ± 0.01 (n = 3). We also examined the GABA-activated current after a 1 min exposure to UVA irradiation. In this case the amplitude of the GABA (10 μm)-activated current was 1.08 ± 0.07 (n = 4) with respect to the control. These results suggest that the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptors are much less sensitive, if at all, to light with a wavelength longer than 340 nm.

Positive modulation of UV irradiation on the GABAA receptor was independent of the effect of diazepam

Modulation of GABAA, but not GABAC, receptors by UV irradiation raised the possibility that the mechanism of UV potentiation might overlap with that of the GABAA receptor allosteric modulator, diazepam. To investigate this possibility, we tested diazepam after potentiation by UV irradiation. Figure 5 shows that UV irradiation shifted the GABA dose-response curve to the left. The EC50 decreased from a control value of 34.5 ± 2.6 to 18.7 ± 4.7 μm after UV irradiation (n = 3). Diazepam (1 μm) further shifted the dose-response curve to the left with an EC50 of 8.2 ± 1.1 μm. The additional 2.3-fold decrease in the EC50 by diazepam after a saturating UV irradiation was comparable to the 2.5-fold shift by the same diazepam concentration without UV (Ghansah & Weiss, 1999) indicating that the potentiation by irradiation does not occlude potentiation by diazepam.

Figure 5. UV-mediated modulation of GABAA receptors was distinct from benzodiazepine- mediated modulation.

A, current traces induced by a range of GABA concentrations before irradiation, after irradiation, and after UV irradiation in the presence of 1 μm diazepam. B, the normalized currents were plotted against GABA concentration. The continuous lines are least-squares fits of the data points to eqn (1). Note that after a saturating UV exposure, diazepam still shifted the GABA dose-response curve to the left (∼2.3 fold). This is similar to the 2.5-fold shift by the same diazepam concentration without UV (Ghansah & Weiss, 1999).

The UV effect on GABAA receptors cannot be prevented by free radical scavengers, nor mimicked by a free radical generator

UV irradiation can generate free radicals, which in turn can activate protein kinases, thereby modulating protein function (Klotz et al. 1997). To test the possibility of UV irradiation acting through free radicals, we used the following free radical scavengers: the singlet oxygen quenchers, sodium azide (40 mm) and imidazole (40 mm), or the hydroxyl radical scavenger, d-mannitol (40 mm). These compounds have been shown to block the UV irradiation effects on c-Jun-N-terminal kinase (Klotz et al. 1997) at similar concentrations. For UV irradiation, we used an exposure (20 s × max) that achieved about 75 % of the maximum potentiation on GABAA receptors and the oocytes were both preincubated in the compounds and incubated during UV exposure. The level of potentiation was unaltered by these compounds with a fractional potentiation of 2.80 ± 0.20 (n = 5), 2.88 ± 0.19 (n = 3), 3.05 ± 0.14 (n = 3) and 2.61 ± 0.25 (n = 3) for normal OR2 (control), sodium azide, d-mannitol and imidazole, respectively. In addition 1 % H2O2 (free radical generator) did not potentiate the GABA-induced current. In fact, the current was slightly decreased after H2O2 treatment to 0.80 ± 0.01 of the control value (n = 3). This oxidation stress has an inhibitory effect on GABAA receptors similar to the effect of the oxidizing agent, 5–5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (Pan et al. 2000). These two pieces of evidence suggest that UV light exerts its effect on GABAA receptors by means other than through free radicals.

DISCUSSION

GABAA and GABAC receptors have distinct activation and pharmacological properties. In this study, we have provided evidence that they are also distinct in UV-mediated modulation. UV irradiation has positive allosteric modulatory effects on α1β2, α1β2γ2 and β2γ2 GABAA receptors, but not on ρ1 GABAC receptors. The UV potentiation of α1β2γ2 GABA receptors was only partially reversible, did not appear to overlap the effect of the benzodiazepine diazepam and did not appear to be mediated by singlet oxygen or hydroxyl radicals.

Speculation on the mechanism of the UV effect on GABA receptors

The possible mechanism of the UV-mediated potentiation of GABAA receptors could be a direct effect on the GABAA receptor or an indirect effect such as activation of intracellular signalling pathways, which in turn modulate channel function. The direct effect could be due to absorption of UV light by select amino acids such as tyrosine, phenylalanine, tryptophan or cysteine. The cross-linking or ionization of these residues could change the free energy landscape of the receptor and result in changes in receptor conformation and responsiveness to agonists. For example, redox modulation of recombinant GABAA, but not GABAC, receptors has been reported (Amato et al. 1999; Pan et al. 2000) which involved a cysteine residue in the M3 domain. We mutated the corresponding amino acid residue in the ρ1 subunit to cysteine (S330C) and, similar to the wild type ρ1 receptor, we failed to see an UV effect on this mutant GABAC receptor (data not shown). Furthermore, the reported redox effect on GABA receptors was mainly limited to an amplitude change without a significant change in GABA sensitivity (Amato et al. 1999; Pan et al. 2000). In contrast, the UV-mediated modulation we report here mainly changed the EC50 with little effect on the maximum current in α1β2γ2 and β2γ2 GABA receptors. For α1β2 GABA receptors, however, UV irradiation decreased the EC50 and increased the maximum current. This does not necessarily imply a different mechanism of modulation since an increase in the ratio of the opening and closing rate constants could shift the dose-response relationship to the left and would also increase the maximum if the initial maximum open probability (before UV irradiation) was low, as has been reported for αβ receptors (Serafini et al. 2000). This subunit-dependent potentiation of the maximum amplitude is similar to the reported dithiothreitol (DTT) effect (Amato et al. 1999; Pan et al. 2000). One difference, however, is that the UV potentiation has a much longer lifetime than the DTT effect, which is rapidly reversible (Pan et al. 2000). Since the apparent affinity of GABAA receptors increased upon UV irradiation, UV irradiation could also interact with residues in the GABA binding site. However, conservation of tyrosines in proposed GABA binding sites (Amin & Weiss, 1993, 1994) across α1, β2, γ2 and ρ1 subunits suggests that it is unlikely that UV irradiation can selectively modulate tyrosine residues in α1, β2 or γ2 subunits, but not in the highly homologous ρ1 subunit.

GABAA receptors can be modulated by interacting with other proteins (Brandon et al. 1999; Liu et al. 2000) or by phosphorylation (Moss et al. 1995; Yan & Surmeier, 1997; McDonald et al. 1998; Poisbeau et al. 1999; Filippova et al. 2000; Flores-Hernandez et al. 2000). Concerning a potential indirect effect of UV irradiation on GABA receptors, UV irradiation could activate a protein kinase, which in turn could modulate receptor function. There is evidence that many protein kinases can be activated by UV irradiation (Bender et al. 1997). The phosphorylation of tyrosine residues of several growth factor receptors is the early detectable cellular reaction after UV irradiation (Bender et al. 1997). However, 40 μm genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, did not block the UV-mediated modulation of the GABAA receptor (data not shown).

Potential significance of the finding

In this study we demonstrate that GABAA receptors can be modulated by UV irradiation. It has previously been demonstrated that light of wavelength < 324 nm potentiates NMDA receptors in isolated retinal neurons (Leszkiewicz et al. 2000). Thus, both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission are potential targets for light-mediated modulation. The components of sunlight with wavelength shorter than 290 nm (UVC) do not reach the earth's surface because they are absorbed by the ozone layer (Madronich, 1993). UVB and UVA, however, do reach the earth's surface, and can cause significant damage to skin and eyes. Whether UVB and UVA can reach the human retina is still controversial. For example, it has been suggested that the young primate lens can transmit UVB (Gaillard et al. 2000). In contrast, Dillon et al. (2000) concluded that the anterior segment of young primates transmits almost no UV light. Therefore, there is a possibility that UV light may have an influence on GABAA receptors in the human retina, which may have potential physiological or pathophysiological significance. For example, stimulation of GABAA receptors may be neurotoxic in the retina (Chen et al. 1999). Furthermore, the elucidation of the mechanism of UV-mediated potentiation on GABAA receptors may provide a new way to modulate GABAA receptor function, although identification of the precise mechanism must await future studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by DK07545 to Y. Chang and by NS35291 to D. S. Weiss.

References

- Albrecht BE, Breitenbach U, Stuhmer T, Harvey RJ, Darlison MG. In situ hybridization and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction studies on the expression of the GABAC receptor ρ1- and ρ1-subunit genes in avian and rat brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;9:2414–2422. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato A, Connolly CN, Moss SJ, Smart TG. Modulation of neuronal and recombinant GABAA receptors by redox reagents. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:35–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0035z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J, Dickerson I, Weiss DS. The agonist binding site of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A channel is not formed by the extracellular cysteine loop. Molecular Pharmacology. 1994;45:317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J, Weiss DS. GABAA receptor needs two homologous domains of the β-subunit for activation by GABA but not by pentobarbital. Nature. 1993;366:565–569. doi: 10.1038/366565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin J, Weiss DS. Homomeric ρ1 GABA channels: Activation properties and domains. Receptors and Channels. 1994;2:227–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard EA, Darlison MG, Seeburg P. Molecular biology of the GABAA receptor: the receptor/channel superfamily. Trends in Neuroscience. 1987;10:502–509. [Google Scholar]

- Bender K, Blattner C, Knebel A, Iordanov M, Herrlich P, Rahmsdorf HJ. UV-induced signal transduction. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 1997;37:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(96)07459-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon NJ, Uren JM, Kittler JT, Wang H, Olsen R, Parker PJ, Moss SJ. Subunit-specific association of protein kinase C and the receptor for activated C kinase with GABA type A receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:9228–9234. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09228.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Moulder K, Tenkova T, Hardy K, Olney JW, Romano C. Excitotoxic cell death dependent on inhibitory receptor activation. Experimental Neurology. 1999;160:215–225. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting GR, Lu L, O'Hara BF, Kasch LM, Montrose-Rafizadeh C, Donovan DM, Shimada S, Antonarakis SE, Guggino WB, Uhl GR, Kazazian HH. Cloning of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) ρ1 cDNA: a GABA receptor subunit highly expressed in the retina. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:2673–2677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon J, Zheng L, Merriam JC, Gaillard ER. Transmission spectra of light to the mammalian retina. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2000;71:225–229. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)071<0225:tsoltt>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz R, Brandstatter JH, Hartveit E, Wassle H, Bormann J. Expression of GABA receptor ρ1 and ρ1 subunits in the retina and brain of the rat. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;7:1495–1501. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz R, Brandstatter JH, Wassle H, Bormann J. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAc receptor ρ subunits in the mammalian retina. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:4479–4490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenspan A, Wassle H, Bormann J. Pharmacology of GABA receptor Cl− channels in rat retinal bipolar cells. Nature. 1993;361:159–162. doi: 10.1038/361159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippova N, Sedelnikova A, Zong Y, Fortinberry H, Weiss DS. Regulation of recombinant γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A and GABAC receptors by protein kinase C. Molecular Pharmacology. 2000;57:847–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Hernandez J, Hernandez S, Snyder GL, Yan Z, Fienberg AA, Moss SJ, Greengard P, Surmeier DJ. D(1) dopamine receptor activation reduces GABAA receptor currents in neostriatal neurons through a PKA/DARPP-32/PP1 signaling cascade. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:2996–3004. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard ER, Zheng L, Merriam JC, Dillon J. Age-related changes in the absorption characteristics of the primate lens. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2000;41:1454–1459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garret M, Bascles L, Boue-Grabot E, Sartor P, Charron G, Bloch B, Margolskee RF. An mRNA encoding a putative GABA-gated chloride channel is expressed in the human cardiac conduction system. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;68:1382–1389. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghansah E, Weiss DS. Benzodiazepines do not modulate desensitization of recombinant α1β2γ2 GABA(A) receptors. NeuroReport. 1999;10:817–821. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199903170-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedblom E, Kirkness EF. A novel class of GABAA receptor subunit in tissues of the reproductive system. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:15346–15350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston GAR. GABAC receptors: relatively simple transmitter-gated ion channels? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1996;17:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khrestchatisky M, Maclennan J, Chiang M, Xu W, Jackson M, Brecha N, Sternini C, Olsen R, Tobin A. A novel α subunit in rat brain GABAA receptors. Neuron. 1989;3:745–753. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz LO, Briviba K, Sies H. Singlet oxygen mediates the activation of JNK by UVA radiation in human skin fibroblasts. FEBS Letters. 1997;408:289–291. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leszkiewicz DN, Kandler K, Aizenman E. Enhancement of NMDA-mediated currents by light in rat neurones in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 2000;524:365–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan ES, Blair LA, Dionne VE, Barnard EA. Biophysical and pharmacological properties of cloned GABAA receptor subunits expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Neuron. 1988;1:773–781. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Wan Q, Pristupa ZB, Yu XM, Wang YT, Niznik HB. Direct protein-protein coupling enables cross-talk between dopamine D5 and γ-aminobutyric acid A receptors. Nature. 2000;403:274–280. doi: 10.1038/35002014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz PD. GABAC receptors in the vertebrate retina. Molecular Neurobiology. 1996;12:181–194. doi: 10.1007/BF02755587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BJ, Amato A, Connolly CN, Benke D, Moss SJ, Smart TG. Adjacent phosphorylation sites on GABAA receptor β subunits determine regulation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:23–28. doi: 10.1038/223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor channels. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1994;17:569–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madronich S. The atmosphere and UVB radiation at ground level. In: Young A, Bjorn L, Moan J, Nultsch W, editors. Environmental UV Photobiology. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Malherbe P, Sigel E, Baur R, Persohn E, Richards JG, Mohler H. Functional characteristics and sites of gene expression of the α1, β1, γ2-isoform of the rat GABAA receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:2330–2337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02330.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss SJ, Gorrie GH, Amato A, Smart TG. Modulation of GABAA receptors by tyrosine phosphorylation. Nature. 1995;377:344–348. doi: 10.1038/377344a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW, Tobin AJ. Molecular biology of GABAA receptors. FASEB Journal. 1990;4:1469–1480. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.5.2155149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZH, Zhang X, Lipton SA. Redox modulation of recombinant human GABAA receptors. Neuroscience. 2000;98:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poisbeau P, Cheney MC, Browning MD, Mody I. Modulation of synaptic GABAA receptor function by PKA and PKC in adult hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19:674–683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00674.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett DB, Sontheimer H, Shiver BD, Ymer S, Kettenmann H, Schofield P, Seeburg PH. Importance of a novel GABAA receptor subunit for benzodiazepine pharmacology. Nature. 1989;338:582–586. doi: 10.1038/338582a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Dowling J. Novel GABA responses from rod-driven retinal horizontal cells. Nature. 1993;361:162–164. doi: 10.1038/361162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield PR, Darlison MG, Fujita N, Burt DR, Stephenson FA, Rodriguez H, Rhee LM, Ramachandran J, Reale V, Glencorse TA, Seeburg PH, Barnard EA. Sequence and functional expression of the GABAA receptor shows a ligand-gated receptor superfamily. Nature. 1987;328:221–227. doi: 10.1038/328221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini R, Bracamontes J, Steinbach JH. Structural domains of the human GABAA receptor β3 subunit involved in the actions of pentobarbital. Journal of Physiology. 2000;524:649–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel E, Baur R, Trube G, Mohler H, Malherbe P. The effect of subunit composition of rat brain GABAA receptors on channel function. Neuron. 1990;5:703–711. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Bracamontes J, Zorumski C, Weiss DS, Steinbach JH. Bicuculline and gabazine are allosteric inhibitors of channel opening of the GABAA receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:625–634. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00625.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn TA, Draguhn A, Ymer S, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Functional properties of recombinant rat GABAA receptors depend upon subunit composition. Neuron. 1990;4:919–928. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegelius K, Pasternack M, Hiltunen JO, Rivera C, Kaila K, Saarma M, Reeben M. Distribution of GABA receptor rho subunit transcripts in the rat brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;10:350–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting PJ, McAllister G, Vassilatis D, Bonnert TP, Heavens RP, Smith DW, Hewson L, O'Donnell R, Rigby MR, Sirinathsinghji J, Marshall G, Thompson SA, Wafford KA, Vassilatis D. Neuronally restricted RNA splicing regulates the expression of a novel GABAA receptor subunit conferring atypical functional properties. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17:5027–5037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05027.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward R, Polenzani L, Miledi R. Characterization of bicuculline/baclofen-insensitive-aminobutyric acid receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. I. Effects of Cl− channel inhibitors. Molecular Pharmacology. 1992;42:165–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Surmeier DJ. D5 dopamine receptors enhance Zn2+-sensitive GABAA currents in striatal cholinergic interneurons through a PKA/PP1 cascade. Neuron. 1997;19:1115–1126. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh HH, Grigorenko EV, Veruki ML. Correlation between a bicuculline-resistant response to GABA and GABAA receptor ρ1 subunit expression in single rat retinal bipolar cells. Visual Neuroscience. 1996;13:283–292. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800007525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]