Abstract

Using a Ussing chamber and neuronal retrograde tracing with 1,1′-didodecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) we characterized the afferent and efferent neuronal pathways which mediated distension-evoked secretion in the guinea-pig distal colon.

Acute capsaicin application (10 μm) to the serosal site of the Ussing chamber evoked a secretory response which was blocked by tetrodotoxin (1 μm), the combined application of the NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists CP-99,994–1 and SR 142801 (1 μm), and by combined application of atropine (10 μm) and the VIP receptor antagonist VIP(6–28) (10 μm). Functional desensitization of extrinsic primary afferents by long-term application of capsaicin significantly diminished distension-evoked secretion by 46 %.

After functional desensitization by capsaicin, serosal application of gadolinium (100 μm) inhibited the distension-evoked chloride secretion by 54 %; the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine (1 μm) and the 5-HT1P receptor antagonist renzapride (1 μm) had no effect. The combination of atropine and VIP(6–28) or the combination of NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists almost abolished distension-evoked secretion.

The secretory response evoked by electrical field stimulation, carbachol (1 μm) or VIP (1 μm) was not attenuated by gadolinium. Field stimulation-evoked chloride secretion was not affected by blockade of NK1 and NK3 receptors.

Twelve per cent of DiI-labelled submucosal neurones with projections to the mucosa were immunoreactive for choline acetyltransferase, substance P and calbindin and very probably represented intrinsic primary afferent neurones.

Distension-evoked chloride secretion was mediated by capsaicin-sensitive extrinsic primary afferents and by stretch-sensitive intrinsic primary afferent neurones. Both the extrinsic and intrinsic afferents converge on common efferent pathways. These pathways consist of VIPergic and cholinergic secretomotor neurones that are activated via NK1 and NK3 receptors.

The enteric nervous system contains local circuits for integrative functions that are essential for regulation and co-ordination of secretory and motor function of the gut (Wood, 1994). Although enteric reflexes operate independently of the central nervous system they are modulated by extrinsic neuronal inputs which arise from sympathetic, parasympathetic or sensory fibres (Wood, 1994). Therefore, the global behaviour of the gut at any moment reflects the integrated activity of intrinsic and extrinsic networks. It is increasingly recognized that neural degeneration and malfunctions of these networks are underlying factors in gastrointestinal disorders (Wood et al. 1999). Dysfunction may occur at the level of afferent and/or motor pathways. Several motor, as well as afferent, pathways exist and their activation is in part stimulus specific. Sensory transmission in the gut is either extrinsic, via vagal or spinal afferents, or via intrinsic primary afferent neurones (IPANs) which are located in the enteric nervous system. A substantial proportion of extrinsic primary afferents express capsaicin-sensitive receptors and it is possible to functionally desensitize them by long-term application of capsaicin (Holzer, 1991b). In contrast, IPANs are not directly affected by capsaicin (Takaki & Nakayama, 1989; Vanner & MacNaughton, 1995). The current concepts indicate that IPANs are located in the myenteric (Furness et al. 1998) as well as in the submucosal plexus (Pan & Gershon, 2000). Both populations of IPANs may respond to chemical and/or mechanical stimuli directly or indirectly through the release of intermediary substances.

The role of intrinsic reflex pathways mediating the peristaltic reflex has been studied extensively (Kunze & Furness, 1999). The neuronal basis of the peristaltic reflex is the polarized projection of myenteric excitatory and inhibitory motor neurones, causing circular muscle contraction oral, and relaxation anal, to the stimulation site (Smith & Robertson, 1998; Smith & McCarron, 1998; Stevens et al. 1999). Such polarized projections are a general principle of enteric circuits in various regions of the gut (Song et al. 1992; Schemann & Schaaf, 1995; Sang et al. 1997; Michel et al. 2000). Several findings suggest that IPANs may be located in the submucosal and/or in the myenteric plexus (Kirchgessner et al. 1992; Furness et al. 1998). IPANs have common characteristic features that are independent of their specific location. They exhibit multipolar Dogiel type 2 morphology, belong electrophysiologically to the population of AH neurones, and their neurochemical characterization indicate that they contain choline acetyltransferase, substance P and calbindin (Kirchgessner et al. 1992; Costa et al. 1996; Neunlist et al. 1999; Lomax & Furness, 2000). Recently, it has been reported that gadolinium, a blocker of some stretch-activated ion channels, inhibits firing in IPANs excited by maintained tension in the muscle probably by an action on the muscle itself (Kunze et al. 1999). In addition to IPANs, there is evidence that primary sensory neurones of the extrinsic nervous system are also involved in the mediation of the peristaltic reflex (Grider & Jin, 1994). This is based on findings that capsaicin, which is neurotoxic to extrinsic sensory neurones (Holzer, 1991b), impairs stretch-activated muscle responses in the rat colon (Grider & Jin, 1994).

We have recently identified polarized innervation pathways to the mucosa of the guinea-pig colon and demonstrated their functional significance. Selective activation of the different pathways revealed that descending secretomotor neurones release VIP, whereas ascending secretomotor neurones release acetylcholine (Neunlist et al. 1998; Neunlist & Schemann, 1998). These secretomotor pathways are involved in reflex-activated secretory responses. It has been demonstrated that mechanical stimuli, such as mucosal stroking and tissue distension, initiate chloride secretion, mediated via submucosal neurones (Diener & Rummel, 1990; Frieling et al. 1992; Schulzke et al. 1995; Sidhu & Cooke, 1995). Some of the neural components that are involved in mucosal stroking-evoked secretion have been characterized. Thus, it is known that mucosal distortion initially induces release of 5-HT from enterochromaffin cells (Kirchgessner et al. 1992; Sidhu & Cooke, 1995; Gershon, 1999). 5-HT then activates submucosal IPANs, probably via 5-HT1P receptors. The resulting secretion is mediated by acetylcholine and VIP. An additional role for prostaglandins has been demonstrated for mucosal stroking-evoked secretory responses. A comparable characterization of sensory and motor components involved in distension-evoked secretory responses is missing.

Therefore, it was the aim of the present study to characterize functionally and morphologically the afferent and efferent pathways as well as the mediators involved in distension-evoked chloride secretion in the guinea-pig distal colon using a modified Ussing chamber technique and neuronal retrograde tracing.

METHODS

All experiments were carried out on preparations from male guinea-pigs (300–500 g) that were killed by cervical dislocation followed by exsanguination. All procedures used were in accordance with the German ethical guidelines for animal experiments and were approved by the animal care committees of Düsseldorf and Hannover.

Ussing chamber experiments

The distal colon (5–10 cm proximal to the anus) was removed, opened along the mesenteric border, and rinsed free of luminal contents. The longitudinal and circular muscle layers and the myenteric plexus were removed by blunt dissection to leave sheets of submucosa/ mucosa that were mounted in modified Ussing chambers with a measuring area of 0.785 cm2. The mucosal and serosal sides were bathed separately with 10 ml of modified Krebs solution. The solution was of the following composition (mm): NaCl, 117; KCl, 4.7; MgCl2, 1.2; NaH2PO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 25; CaCl2, 2.5; glucose, 11.5, maintained at 37 °C, aerated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2, and buffered at a pH of 7.4.

The experimental methods for studying mucosal transport were similar to those described previously (Frieling et al. 1992). Briefly, the chambers were equipped with a pair of Krebs Ringer agar bridges connected to calomel half cells for measurement of transepithelial potential difference (PD) with respect to the luminal solution. Positive short-circuit currents (Isc) indicated a net anion current from serosa to lumen. A pair of Ag-AgCl disk electrodes was connected to a voltage clamp apparatus (VCC 600, Physiologic Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) that compensated for the solution resistance between the PD sensing bridges. Electrodes were juxtaposed between the Ussing chamber halves and the submucosal surface. Tissue conductance was calculated according to Ohm's law.

Tissue distension was evoked by removal of small volumes of bath solution from the serosal side with the outer and inner tubing ports of the Ussing chamber clamped. Infusion of solution to the mucosal side was not performed in order to avoid direct mechanical stimulation of the mucosal cell lining. The serosal volume removal induced pressure gradients and caused distension of tissue to the serosal side (Frieling et al. 1992). After replacement of the bath solution the tissue returned to its original position. The time between two distension stimuli was 3 min. Distention-evoked increases in Isc reflected electrogenic chloride secretion (Frieling et al. 1992; Schulzke et al. 1995). The onset of distention-evoked increases in Isc was reached after 35.7 ± 16.5 s; the baseline value of Isc was restored after 80.2 ± 21.7 s.

Using a micropump (SP230iw, World Precision Instruments, Berlin, Germany), 200, 220, 240, 260, 280 and 300 μl of bath solution were consecutively removed and replaced immediately. The distending volumes corresponded to volumes of faecal pellets (260 ± 60 μl) as well as to the volumes of pellet-dilated distal colonic segments (250 ± 40 μl). In initial experiments, each of the distending volumes were applied with velocities of 11.7, 36.7, 55.0 and 73.3 μl s−1. The distending volumes and velocities induced tissue distension of 5.5–51.4 s duration, which was within the range of physiological values of distension duration obtained during natural pellet propagation (Jin et al. 1999).

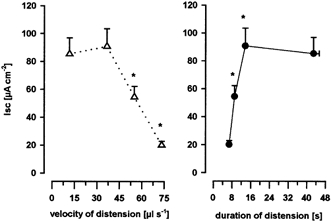

The magnitude of the distension-evoked increase in Isc was dependent on the distending volume, the velocity and the duration of distension. The effects of velocity and duration were demonstrated by calculating the mean increase in Isc over all volumes at a given distension velocity. A decrease in the velocity of distension from 73.3 to 55.0 and then to 36.7 μl s−1 (n = 6 tissues) and the corresponding prolongation in the mean duration of distension from 6.8 ± 0.4 to 9.1 ± 0.5 and then to 13.6 ± 0.8 s significantly enhanced the distension-evoked increase in Isc from 20.1 ± 2.8 to 54.5 ± 7.7 and then to 90.8 ± 12.7 μA cm−2, respectively. No further increase in mean Isc occurred at lower distension velocities and corresponding longer durations of distension (Fig. 1). In order to investigate distension-evoked electrogenic chloride secretion in a mainly volume-dependent approach, i.e. unaffected by distending velocity and nearly unaffected by distension duration, all experiments were conducted with a constant distending velocity of 36.7 μl s−1. With this velocity and distension volumes of 200, 220, 240, 260, 280 and 300 μl the corresponding distension durations were 10.9, 12.0, 13.1, 14.2, 15.3 and 16.4 s, respectively. At significant distension volumes (> 240 μl), the corresponding durations of distension (> 14 s) were shown to have a minor influence on the increase in Isc (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Effects of velocity and duration on distension-evoked chloride secretion.

Distension-evoked increase in short-circuit current (Isc), representing electrogenic chloride secretion, decreased with increasing velocity of distension and increased with increasing duration of distension. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m.; * significantly different from next lower velocity of distension or significantly different from next longer mean duration of distension; P < 0.05 ANOVA, post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test, n = 6 tissues per velocity or duration.

The distension-evoked increase in Isc was studied during neuronal blockade (tetrodotoxin), functional extrinsic desensitization (capsaicin) and in the presence or absence of various antagonists. The antagonists were given 10 min prior to the first distension stimulus.

Organotypic culture of distal colon segments and retrograde tracing

Specimens of distal colon (5–10 cm proximal to the anus; 4–5 cm in length) were removed and placed in modified Krebs solution (composition as used in the Ussing chamber experiments with the addition of 1–3 μm nifedipine). The organotypic culture method has been previously described in detail (Neunlist & Schemann, 1997). After removal from the animal and several washes, a 7 cm × 2 cm segment of distal colon was pinned flat out in a Sylgard-covered Petri dish and the mucosa was carefully removed except for a small patch of about 1 cm × 1 cm. A DiI (1,1′-didodecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA)-coated glass bead (diameter 50–100 μm) was slightly pressed onto the mucosa with forceps. Care was taken not to push the bead too deep into the mucosa.

Following the bead application, 20 ml of culture medium containing 1 μm nifedipine was added to the culture dish. The culture medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's-Ham's F-12 medium; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) was supplemented with 10 % heat inactivated fetal calf serum (CC Pro, Karlsruhe, Germany), 100 i.u. ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 2.75 μg ml−1 amphotericin B, and 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin (Sigma) and adjusted to pH 7.4. The tissue was maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and equilibrated with 5 % CO2 in air for a period of 48 to 72 h. The dishes were placed on a rocking tray shaking at a frequency of about 0.5 Hz. The culture medium was changed once daily.

Immunohistochemistry

The tissue was fixed overnight in 2 % paraformaldehyde and 0.2 % picric acid in 0.1 m phosphate buffer at 4 °C (pH = 7.44). The fixed tissue was then repeatedly washed with phosphate buffer. The DiI application site was marked by pushing a hole with a fine needle. Further dissection was done to obtain a submucous plexus preparation.

Immunohistochemical detection of neuronal antigens was made using a procedure previously described in detail (Neunlist & Schemann, 1997). After the membrane permeabilization procedure, the tissue was exposed at room temperature to the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) (1:2000) (Schemann et al. 1993) or goat anti-ChAT (1:100; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA), mouse anti-calbindin (Calb) (1:200; SWANT, Bellinzona, Switzerland), rat anti-substance P (SP) (1:1000; Fitzgerald, USA/ 10-SO15). The following affinity-purified secondary antibodies were used: goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to indodicarbocyanin (Cy5), goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to either dichloro-triazinyl aminofluorescin (DTAF) 1:100 and goat anti-rat conjugated to 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetate (AMCA) 1:50 (all secondary antibodies from Dianova, Hamburg, Germany). An Olympus IX70 microscope (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) fitted with the following filter cubes (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) was used for immunohistochemical studies: UM41007 (Beam splitter: 565 DCLP, Ex.: BP 530–560, Em.: BP 575–645) for DiI, U-MNIBA (Beam splitter DM 505, Ex.: BP 470–490, Em.: D520) for DTAF, U-MWU (Beam splitter DM400, Ex.: BP 330–385, Em.: BP 460–490) for AMCA and U-M41008 (Beam splitter Q660 LP, Ex.: BP 540–650, Em.: BP 667–735) for Cy5. No cross-detection between the four fluorophores-filter cube combinations was observed. The preparations were further analysed using an image analysis system. Pictures were acquired with a black and white video camera (Mod. 4910, Cohu Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) connected to a Macintosh computer and controlled by the IPLab Spectrum 3.0 software (Signal Analytics, Vienna, VI, USA). Frame integration and contrast enhancement was used for picture processing.

Computer assisted mapping of DiI neurones

In the present study the same notations are used as described previously (Neunlist & Schemann, 1998). In brief, each DiI-labelled neurone was located with respect to its Cartesian x and y co-ordinate from the DiI application site using a computerized stage mapping system (Märzhäuser and Kassen, Wetzlar, Germany) with a precision of 1 μm. The DiI application site had the co-ordinate: 0;0. Longitudinally projecting neurones were neurones whose co-ordinate verified: |x| > |y|. Circumferentially projecting neurones verified: |x| < |y|. Longitudinally projecting neurones were further classified into two categories: descending neurones, i.e. neurones whose cell bodies were located oral from the DiI application site (x < 0), and ascending neurones, i.e. neurones whose cell bodies were located anal from the DiI application site (x > 0). The projection distance of the DiI-labelled soma from the tracer application site (d) was calculated as

Data were plotted and analysed with Sigma Plot and Sigma Stat (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) on a personal computer.

Chemicals

Tetrodotoxin (TTX), atropine, gadolinium, nifedepine and capsaicin were purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). The NK3 receptor antagonist SR 142801 was provided by Sanofi (Montpellier, France); the NK1 receptor antagonist CP-99,994–1 was from Pfizer Inc. (Groton, CT, USA). The VIP receptor antagonist VIP(6–28) was purchased from Peninsula (Belmont, CA, USA). The 5-HT1P receptor antagonist renzapride (BRL 24924A) was a gift from SmithKline Beecham (Harlow, UK). Atropine, capsaicin, SR 142801 and renzapride were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). All other substances were dissolved in Krebs solution. When DMSO was used as solvent, control experiments were performed with the vehicle.

Statistics

All data are expressed as means ±s.e.m. The data were assessed for statistical analysis using ANOVA. A significant difference was considered at P < 0.05 (post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test). In Ussing chamber experiments, statistical analysis was performed between treated tissues and the same number of corresponding control tissues. In the figures, control values of the corresponding experiments have been pooled in order to get a clear presentation. There was no significant difference among the different control groups (ANOVA).

RESULTS

Ussing chamber experiments

The results were obtained from 188 submucosa/mucosa preparations from 47 guinea-pigs. The guinea-pig distal colon exhibited baseline short-circuit current (Isc) and conductance comparable to that described previously (Frieling et al. 1992; Kuwahara & Cooke, 1990). Average basal Isc was −15.5 ± 3.0 μA cm−2 and total tissue conductance was 11.4 ± 0.2 mS cm−2. The magnitude of the distension-evoked Isc increased with increasing distension volumes. Volumes of 200, 220, 240, 260, 280 and 300 μl evoked Isc of 6.7 ± 1.6, 25.7 ± 7.7, 51.4 ± 12.1, 101.9 ± 16.3, 178.6 ± 23.4 and 259.5 ± 26.7 μA cm−2, respectively (n = 11 tissues).

Extrinsic and intrinsic components: effect of capsaicin and TTX

Serosal application of capsaicin (10 μm) induced an initial increase in Isc that desensitized in the continuous presence of capsaicin. The capsaicin-induced increase in Isc of 218.2 ± 41.3 μA cm−2 (n = 17) reached its maximum after 33.9 ± 2.6 s. Baseline Isc was restored after 5.6 ± 1.1 min. Further applications of capsaicin were without effect indicating functional desensitization of extrinsic primary afferents. Pretreatment of tissues with TTX (1 μm; n = 5) or the NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists CP-99,994–01 and SR 142801 (1 μm; n = 4), completely blocked the capsaicin-induced secretory response. Preincubation of tissues with atropine (10 μm) significantly (P < 0.05) diminished the capsaicin-evoked increase in Isc (109.5 ± 52.6 vs. 333.6 ± 72.6 μA cm−2; n = 4). Combined preincubation of 10 μm atropine together with the VIP receptor antagonist VIP(6–28) (10 μm) virtually abolished capsaicin-mediated secretion (9.6 ± 1.0 vs. 197.1 ± 43.8 μA cm−2; n = 4). These data suggest that capsaicin induced release of substance P that activated cholinergic and VIPergic secretomotor neurones.

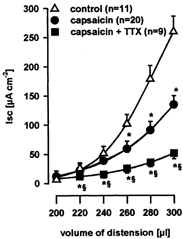

Continuous application of capsaicin has been previously used to induce functional desensitization of extrinsic primary afferents in in vitro preparations (Holzer, 1991a). Functional desensitization of extrinsic primary afferents with capsaicin (10 μm; n = 11) significantly decreased distension-evoked Isc for distending volumes of 260–300 μl by 46.3 ± 1.6 % (Fig. 2). TTX (1 μm) significantly reduced the capsaicin-insensitive component by 61.2 ± 4.2 % for distending volumes of 200–300 μl (n = 9, Fig. 2). This suggested that the capsaicin-insensitive response was mediated by nerves very probably belonging to the enteric nervous system. To characterize this intrinsic neuronal component of the reflex-evoked secretory response, further experiments were performed in the continuous presence of 10 μm capsaicin.

Figure 2. Effect of capsaicin and TTX.

Distension-evoked increase in short-circuit current (Isc), increased with increasing distension volumes. Functional desensitization of extrinsic primary afferents by serosal capsaicin (10 μm) significantly diminished distension-evoked increase in Isc. The remaining neuronal component mediating distension-evoked chloride secretion was significantly inhibited by serosal tetrodotoxin (TTX; 1 μm). Data are presented as means ±s.e.m.; * significantly different from control; § significantly different from capsaicin; P < 0.05 ANOVA, post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test.

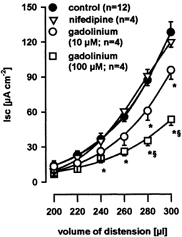

Effect of gadolinium and nifedipine

Serosal application of gadolinium (100 μm) was without effect on the Isc increase induced by electrical field stimulation, carbachol or VIP (Table 1). In contrast, serosal application of gadolinium (100 μm; n = 4) significantly diminished distension-evoked increases in Isc for distending volumes of 240–300 μl by 54.1 ± 3.2 % (Fig. 3). Gadolinium at a lower concentration of 10 μm (n = 4) also significantly, but to a lesser extent, reduced the distension-evoked increase in Isc for distending volumes of 260–300 μl by 32.3 ± 1.7 % (Fig. 3). The magnitude of inhibition of the distension-evoked secretion by gadolinium (100 μm) was comparable to TTX. Consequently, in the presence of TTX, serosal application of 100 μm gadolinium had no further effect on distension-evoked chloride secretion. In the presence of both TTX and gadolinium (n = 4), distensions of 200, 220, 240, 260, 280 and 300 μl evoked increases in Isc of 6.8 ± 2.4, 11.8 ± 1.7, 16.2 ± 2.0, 20.6 ± 2.0, 30.1 ± 1.6, and 43.9 ± 1.7 μA cm−2, respectively. Mucosal application of gadolinium (100 μm; n = 6) had no effect on distension-evoked increases in Isc. Distensions of 200, 220, 240, 260, 280 and 300 μl evoked increases in Isc of 11.7 ± 3.3, 19.3 ± 4.4, 30.6 ± 7.1, 53.2 ± 7.4, 91.5 ± 8.7 and 124.6 ± 16.2 μA cm−2, respectively. Serosal application of the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine (1 μm; n = 4) was without effect on distension-evoked increase in Isc (Fig. 3). These data suggest the involvement of gadolinium-sensitive stretch-activated ion channels in the mediation of distension-evoked chloride secretion. It is noteworthy that gadolinium had comparable effects in capsaicin- and non-capsaicin-treated tissues and decreased distension-evoked Isc depending on the distending volumes (240–300 μl) by 16–75 μA cm−2.

Table 1.

The increase in short-circuit current (Isc) induced by vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), carbachol and electrical field stimulation (EFS, 8 V, 0.5 ms) was not affected by serosal application of gadolinium (Gd3+, 100 μm)

| Isc (μA cm−2) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | n | Gd3+ (100 μm) | n | P value ANOVA | ||

| VIP | 0.01 μm | 24.8 ± 5.9 | 5 | 26.0 ± 8.7 | 4 | 0.430 |

| 0.1 μm | 59.2 ± 24.5 | 66.3 ± 12.2 | 0.793 | |||

| 1 μm | 150.3 ± 38.7 | 127.9 ± 15.5 | 0.991 | |||

| Carbachol | 0.1 μm | 9.3 ± 3.0 | 8 | 9.6 ± 4.1 | 4 | 0.249 |

| 1 μm | 268.9 ± 76.6 | 214.2 ± 88.9 | 0.285 | |||

| 10 μm | 471.4 ± 164.3 | 461.8 ± 116.4 | 0.493 | |||

| EFS | 3 Hz | 120.4 ± 20.6 | 4 | 133.6 ± 24.6 | 4 | 0.267 |

| 10 Hz | 214.8 ± 39.5 | 223.8 ± 31.5 | 0.410 | |||

| 20 Hz | 250.1 ± 47.5 | 241.4 ± 35.4 | 0.597 | |||

Experiments were performed after functional desensitization of primary extrinsic primary afferents with 10 μm capsaicin. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m.

Figure 3. Effect of gadolinium.

The increase of distension-evoked chloride secretion after functional desensitization of extrinsic primary afferents with capsaicin (control) was dose-dependently suppressed by serosal application of gadolinium (10 and 100 μm). Serosal application of nifedipine did not affect distension-evoked chloride secretion. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m.; *significantly different from control; § significantly different from 10 μm gadolinium; P < 0.05 ANOVA, post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test.

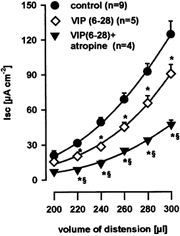

Intrinsic components: effect of VIP(6–28), atropine and NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists

Previous studies have shown that electrical field stimulation-evoked neural increases in Isc were sensitive to VIP receptor antagonists or atropine and were totally blocked by a combination of both (Neunlist et al. 1998). Serosal application of the VIP receptor antagonist VIP(6–28) (10 μm, n = 5) significantly inhibited distension-evoked Isc for distending volumes of 220–300 μl by 33.7 ± 2.7 % (Fig. 4). Combined application of VIP(6–28) and atropine (10 μm; n = 4) resulted in a significant suppression of the distension-evoked Isc for distending volumes of 220–300 μl by 66.7 ± 2.3 % (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Effect of VIP(6–28) and atropine.

Distension-evoked chloride secretion mediated by intrinsic reflex circuits was significantly inhibited by serosal application of the vasoactive intestinal polypeptide receptor antagonist VIP(6–28) (10 μm). Application of both VIP(6–28) and atropine (10 μm) further significantly suppressed the distension-evoked increase in chloride secretion equally as effectively as tetrodotoxin. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m.; *significantly different from control; § significantly different from VIP(6–28); P < 0.05 ANOVA, post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test.

Serosal application of both the NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists CP-99,994–01 and SR 142801 (1 μm; n = 6) significantly diminished the response to tissue distension for distending volumes of 220–300 μl by 65.0 ± 1.1 % (Fig. 5). The magnitude of inhibition of distension-evoked secretion by the NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists was comparable to the combined application of VIP(6–28) and atropine or to TTX. This indicates that the distension-evoked secretory responses were mediated by the neurotransmitter substance P, acetylcholine and VIP. It has previously been shown that NK1 or NK3 agonists induced secretory responses that were blocked by TTX (Frieling et al. 1999). These data, in combination with the finding that application of the NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists (1 μm; n = 6) had no significant effect on the electrically evoked secretory response (211.8 ± 38.2 vs. 242.0 ± 38.5 μA cm−2), indicated that substance P did not directly activate epithelial cells, but that its prosecretory effect was rather due to activation of cholinergic and VIPergic secretomotor neurones.

Figure 5. Effect of NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonism.

Blockade of intrinsic NK1 and NK3 receptors with the corresponding antagonists CP-99,994–01 (1 μm) and SR 142801 (1 μm) suppressed the distension-evoked increase in chloride secretion equally as effectively as tetrodotoxin. Data are presented as means ±s.e.m.; *significantly different from control; P < 0.05 ANOVA, post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test.

Involvement of 5-HT1P receptors

It has been shown that mucosal stroking-evoked secretion involved release of serotonin (5-HT) acting at 5-HT3 and 5-HT1P receptors (Cooke et al. 1997a,c). In contrast, we reported previously that 5-HT3 receptors were not involved in the secretory response to distension (Frieling et al. 1992). In the present study we investigated whether 5-HT1P receptors might be involved in distension-evoked chloride secretion. Serosal application of the 5-HT1P receptor antagonist renzapride (1 μm; n = 4) failed to attenuate the distension-evoked increase in Isc. In the presence of renzapride, distension stimuli of 200, 220, 240, 260, 280 and 300 μl evoked increases in Isc of 10.2 ± 6.6, 20.5 ± 10.6, 37.1 ± 7.8, 63.5 ± 9.2, 110.0 ± 16.4 and 142.3 ± 13.8 μA cm−2, respectively, which were comparable to controls. These data indicate that 5-HT acting on 5-HT1P receptors was not involved in distension-activated chloride secretion.

Tracing studies

In a previous study, we identified ascending cholinergic and descending VIPergic secretomotor neurones in the submucoal plexus (Neunlist et al. 1999). In the present study, we attempted to identify IPANs by applying triple immunohistochemistry for ChAT, SP and Calb to DiI-labelled submucosal neurones with projections to the mucosa.

In a first step we analysed, in 91 submucosal ganglia from five preparations, the average number of ChAT-, SP- and Calb-positive cell bodies per ganglion. This evaluation revealed that there were on average 11.0 ± 1.0 ChAT-, 3.5 ± 0.9 SP- and 5.1 ± 1.0 Calb-positive cell bodies per ganglion. All SP- and Calb-positive neurones were colocalized with ChAT. In addition, almost all (> 99 %) of the SP-immunoreactive neurones were also Calb-positive. These co-localization studies revealed that the population of ChAT/SP/Calb-encoded neurones, very probably representing IPANs, made up 31.5 ± 11.4 % of all ChAT-positive neurones.

In a second step, we applied the retrograde tracer DiI onto the mucosa in order to reveal the chemical coding of dye-labelled submucosal neurones with projections to the mucosa. The analysis of 10 preparations revealed an average number of 92 ± 27 DiI-labelled neurones in the submucous plexus. Of those DiI-traced neurones 34.3 ± 6.5 % were ChAT immunoreactive. Further analysis revealed three subpopulations of ChAT-positive neurones projecting to the mucosa: ChAT alone (ChAT/−), ChAT colocalized with Calb only (ChAT/ Calb/−) and ChAT colocalized with SP and Calb (ChAT/SP/Calb). Of all DiI-labelled neurones the proportions of ChAT/−, ChAT/Calb/− and ChAT/SP/ Calb were 21.5 ± 5.3 % (n = 3 preparations), 7.6 ± 4.4 % (n = 3) and 11.0 ± 3.3 % (n = 9), respectively.

All three subpopulations had projection preferences. Among the ChAT/− neurones 28.1 ± 6.1 % had ascending, 63.2 ± 5.3 % circumferential and 8.8 ± 3.0 % descending projections. The corresponding values for the ChAT/ Calb/− and the ChAT/SP/Calb populations were 28.4 ± 17.4 %, 60.5 ± 28.9 %, 11.1 ± 19.2 %, and 27.3 ± 12.1 %, 66.8 ± 13.7, 6.0 ± 8.3 %, respectively.

Relating the projection preferences of DiI-labelled neurones to their neurochemical coding revealed that of all ascending neurones 59.2 ± 21.3 % had the code ChAT/−, 16.3 ± 5.4 % ChAT/Calb/− and 25.8 ± 10.1 % ChAT/SP/Calb. In addition, of all DiI-labelled neurones with circumferential projections, 49.4 ± 18.9 % had the code ChAT/−, 17.2 ± 14.3 % ChAT/Calb/− and 24.9 ± 5.8 % ChAT/SP/Calb. Finally, only 3.0 ± 0.8 % of all descending DiI-labelled neurones had the code ChAT/−, 0.8 ± 1.3 % ChAT/Calb/− and 2.4 ± 4.1 % ChAT/SP/Calb. We have shown previously that the descending submucosal neurones traced from the mucosa are, in the main, VIP-immunoreactive (Neunlist et al. 1999).

DISCUSSION

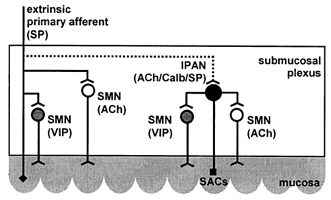

The present study identified neural circuits that mediated increased chloride secretion in response to tissue distension. The results suggested the involvement of intrinsic and extrinsic afferents, which activated cholinergic and non-cholinergic secretomotor neurones (Fig. 6). The proposed model indicates that distension would stimulate capsaicin-sensitive extrinsic sensory neurones as well as submucosal IPANs. Their activation depends on the opening of gadolinium-sensitive stretch-activated ion channels and the concomitant release of substance P. Cholinergic and VIPergic secretomotor neurones are then stimulated via NK1 and NK3 receptor activation. This does not exclude additional activation of myenteric IPANs which send collaterals to the submucosal plexus (Lomax & Furness, 2000).

Figure 6. Model of proposed reflex circuit.

The proposed reflex circuit mediating distension-evoked chloride secretion consists of gadolinium-sensitive stretch-activated channels (SACs) on intrinsic putative afferent neurones (IPAN) and axon collaterals from extrinsic primary afferents that activate VIPergic and cholinergic secretomotor neurones (SMN) by the concomitant release of substance P (SP).

Activation of extrinsic and intrinsic neural components

In the present study, in vitro distension of submucosa/ mucosa preparations of guinea-pig distal colon evoked electrogenic chloride secretion that was dependent on distension volumes and was almost totally blocked by TTX, indicating that sensory elements responding to distension are located on submucosal neurones. However, based on the capsaicin sensitivity, the involvement of distension-sensitive elements on both extrinsic and intrinsic nerves is strongly suggested. Capsaicin is a neurotoxin which selectively affects small-diameter C-fibres but has no direct effect on enteric neurones (Takaki & Nakayama, 1989; Vanner & MacNaughton, 1995). Acute application of capsaicin initially activates extrinsic primary afferents that subsequently release their transmitter substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). However, with time capsaicin functionally desensitizes extrinsic primary afferents (Holzer, 1991b). The present study revealed that capsaicin initially stimulated chloride secretion. This effect was completely blocked by NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists, indicating that substance P but not CGRP was involved. This is in line with a previous report demonstrating that CGRP did not stimulate chloride secretion in the guinea-pig colon (Cooke, 1992). Our results thereby provided functional evidence for axon collaterals, which arise from extrinsic primary afferents and innervate neurones in the submucosal plexus. Previous Ussing chamber experiments and intracellular recordings revealed that extrinsic primary afferents modulate the activity of submucosal secretomotor neurones (Vanner & MacNaughton, 1995) as well as the activity of IPANs in the myenteric plexus (Takaki & Nakayama, 1990). From these data it is suggested that during tissue distension substance P is released from extrinsic primary afferents that in turn activated secretomotor neurones and possibly IPANs, most probably by an axon reflex pathway (Fig. 6).

Although an additional role for non-capsaicin-sensitive afferents cannot be ruled out, there is evidence that the distension-evoked secretory response, which remained after capsaicin-induced functional desensitization, involved activation of submucosal IPANs. After capsaicin-induced functional desensitization, the secretory response is still sensitive to blockade of tachykinin receptors. The neuropharmacology of the remaining response agrees with the neurochemical coding of submucosal IPANs which contain substance P. A non-specific activation of secretomotor neurones by distension can be ruled out because secretomotor neurones in the guinea-pig colon do not contain substance P and the substance-P-evoked increase in secretion was totally blocked by TTX (Frieling et al. 1999). Based on the present results it has to be concluded that neurotransmission of extrinsic afferents as well as IPANs to secretomotor neurones is primarily dependent on the release of substance P.

Intrinsic sensory and motor pathways

The capsaicin-insensitive component of the distension-evoked secretory response was significantly suppressed by the VIP receptor antagonist VIP(6–28) and could be blocked by the combined application of VIP(6–28) and atropine. The combined blockade with VIP(6–28) and atropine was equally as effective as TTX. Previously, it was shown that the mucosa of the guinea-pig colon receives a polarized innervation by descending VIPergic and ascending cholinergic secretomotor neurones of the submucosal plexus (Neunlist et al. 1998; Neunlist & Schemann, 1998). Selective activation of these cholinergic and non-cholinergic pathways evoked increased chloride secretion (Neunlist et al. 1998). The same pathways were activated by distension because the increase in secretion was completely blocked by muscarinic and VIP receptor antagonists. These data support previous findings in the guinea-pig which showed that nerve-mediated colonic secretion consisted of cholinergic and non-cholinergic components (Frieling et al. 1992). In contrast, in the rat colon distension-evoked secretion could be inhibited by VIP desensitization (Schulzke et al. 1995) whereas atropine was without effect (Diener & Rummel, 1990; Schulzke et al. 1995). Although cholinergic neurones exist in the rat submucosal plexus (Vannucchi & Faussone-Pellegrini, 1996) and carbachol increases chloride secretion (Kunze et al. 2000), it appears that cholinergic secretomotor neurones are not activated during distension of the colon in the rat. In addition to possible species differences, it has to be considered that different distension protocols were used. Whereas we applied serosal distension stimuli of 11–16 s duration that evoked chloride secretion lasting for about 1 min, the other studies used a single distension lasting 15 s which caused the tissue to protrude on the mucosal side (Diener & Rummel, 1990) or 40 consecutive distension stimuli within a period of 20 s (Schulzke et al. 1995). Both studies in the rat colon recorded increased secretion lasting for 10 min and 30 min, respectively. We suggest, that the distending protocol used in the our study closely mimicked physiological conditions. The propagation velocity of a faecal pellet in the guinea-pig colon is about 1.3 mm s−1 (Jin et al. 1999) and thus a pellet of 13 mm length will pass through a segment within 10 s, a period which corresponds to the duration of the chloride secretion we observed with our distension protocol.

Previously, it has been suggested that a population of submucosal multipolar Dogiel type 2 neurones with immunoreactivity for substance P might represent IPANs (Bornstein et al. 1989; Kirchgessner et al. 1992; Lomax & Furness, 2000). Several studies have indicated that IPANs in the enteric nervous system contain choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), substance P (SP) and calbindin (Calb) (Kirchgessner et al. 1992; Li & Furness, 1998). Our retrograde tracing results directly demonstrated the existence of ChAT/SP/Calb-positive submucosal neurones with projections to the mucosa of the distal colon.

In the guinea-pig distal colon and ileum, it has been shown that the majority of VIPergic and cholinergic secretomotor neurones could be activated by tachykinins through NK1 and NK3 receptors (MacNaughton et al. 1997; Frieling et al. 1999). Furthermore, in the present study NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists blocked the distension-evoked secretion equally as effectively as TTX. However, the combined use of NK1 and NK3 receptor did not affect the secretion evoked by electrical stimulation, which would be expected to directly excite the cholinergic and VIPergic secretomotor neurones. It is therefore concluded that IPANs activated by distension will release substance P, which will subsequently activate VIPergic and cholinergic secretomotor neurones (Fig. 6).

It has been suggested previously that the enteric nervous system contains mechanosensitive sites that are activated by distension (Diener & Rummel, 1990; Frieling et al. 1992; Schulzke et al. 1995; Eutamene et al. 1997). Generally, the mechanism by which mechanosensitive sites are activated in response to distension is via opening of stretch-sensitive ion channels (Sharma et al. 1995; Hamill & McBride, 1996; Young et al. 1997). The trivalent cation gadolinium blocks stretch-sensitive ion channels in a concentration range of 1–100 μm (Hamill & McBride, 1996). Previous studies have demonstrated that stretch-activated channels are located in human and guinea-pig smooth muscle acting as mechanotransducers that participate in the regulation of smooth muscle contractile activity (Farrugia et al. 1999; Kunze et al. 1999). Stretching of intestinal muscle led to excitation of myenteric neurones indicating mechanotransduction from the muscle to stretch-sensitive sites on myenteric neurones (Kunze et al. 1999). It is not known whether IPANs in the submucosal plexus have similar properties. The present study demonstrated that distension-evoked secretion in muscle-stripped preparations was inhibited by gadolinium and might therefore involve stretch-sensitive ion channels. Recently, it has been demonstrated that mechanosensitive channels are coexpressed with capsaicin-sensitive channels on small dorsal root ganglion cells (Gschossmann et al. 2000). Several findings of our study indicated that mechanosensitive channels were also present on intrinsic nerves. Firstly, gadolinium affected the distension-evoked secretion even after functional desensitization of extrinsic capsaicin-sensitive afferents. Secondly, transduction of the mechanical stimulus by increased muscle tension in the muscularis mucosae is unlikely because the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine was without effect. Thirdly, mucosal application of gadolinium as well as serosal application in the presence of TTX had no effect on distension-evoked chloride secretion, suggesting that stretch-sensitive ion channels were not located in the epithelial or subepithelial cell line. Whether activation of submucosal processes from myenteric neurones, some of which exhibit mechanosensitive ion channels (Kunze et al. 2000), might be additionally involved in distension-evoked secretion remains to be studied.

Non-specific effects of gadolinium are highly unlikely because gadolinium neither affected electrically evoked secretory responses nor the carbachol or VIP-induced increase in chloride secretion. Under our experimental conditions it is also unlikely that the direct hyperpolarizing effects of gadolinium on epithelial cells (Frings et al. 1999) play any significant role. In addition, the inhibition by serosal gadolinium was equally as effective as combined application of NK1 and NK3 receptor antagonists or atropine and the VIP receptor antagonist VIP(6–28).

Distension versus mucosal stroking: differences in neural pathways

It is known, that the mediation of the peristaltic reflex is stimulus specific and differs between mucosal stroking or tissue distension (Yuan et al. 1991). Likewise, different reflex circuits appear to be activated by tissue distension- or mucosal stroking-evoked chloride secretion. Extrinsic primary afferents were apparently not involved in the response to mucosal stroking (Cooke et al. 1997a), whereas a secretory component after tissue distension was capsaicin sensitive and hence involves activation of extrinsic primary afferents (present study). The intrinsic afferent pathways excited by mucosal stroking and tissue distension are also different. Whereas mucosal stroking activates neural pathways indirectly through the release of 5-HT or prostaglandins (Cooke et al. 1997b,c), the present study provides evidence that tissue distension directly activates IPANs through stretch-sensitive ion channels and does not involve 5-HT3 (Frieling et al. 1992) or 5-HT1P receptors (present study). Unlike mucosal stroking, tissue distension-evoked chloride secretion did not depend on cholinergic transmission involving nicotinic receptors (Frieling et al. 1992) although both cholinergic and non-cholinergic secretomotor neurones possess nicotinic receptors (Frieling et al. 1991). Independent of differences in sensory transduction, both mucosal stroking and tissue distension increased chloride secretion by activation of cholinergic and VIPergic secretomotor neurones, indicating a common motor pathway onto which the sensory nerves converge.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Claudia Rupprecht for her excellent technical assistance. The work was supported by DFG Fr 733/13–1 to T.F., by SFB 280 to M.S. and a Marie Curie Fellowship from the European community to M.N.

References

- Bornstein JC, Furness JB, Costa M. An electrophysiological comparison of substance P-immunoreactive neurons with other neurons in the guinea-pig submucous plexus. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1989;26:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(89)90159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ. Calcitonin gene-related peptides: influence on intestinal ion transport. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;657:313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb22778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Sidhu M, Fox P, Wang YZ, Zimmermann EM. Substance P as a mediator of colonic secretory reflexes. American Journal of Physiology. 1997a;272:G238–245. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.2.G238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Sidhu M, Wang YZ. 5-HT activates neural reflexes regulating secretion in the guinea-pig colon. Neurogastroenterology and Motility. 1997b;9:181–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.1997.d01-41.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Sidhu M, Wang YZ. Activation of 5-HT1P receptors on submucosal afferents subsequently triggers VIP neurons and chloride secretion in the guinea-pig colon. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1997c;66:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(97)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa M, Brookes SJ, Steele PA, Gibbins I, Burcher E, Kandiah CJ. Neurochemical classification of myenteric neurons in the guinea-pig ileum. Neuroscience. 1996;75:949–967. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00275-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener M, Rummel W. Distension-induced secretion in the rat colon: mediation by prostaglandins and submucosal neurons. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1990;178:47–57. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)94792-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eutamene H, Theodourou V, Fioramonti J, Bueno L. Rectal distention-induced colonic net water secretion in rats involves tachykinins, capsaicin sensory, and vagus nerves. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1595–1602. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia G, Holm AN, Rich A, Sarr MG, Szurszewski JH, Rae JL. A mechanosensitive calcium channel in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:900–905. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieling T, Cooke HJ, Wood JD. Synaptic transmission in submucosal ganglia of guinea pig distal colon. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;260:G842–849. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.260.6.G842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieling T, Dobreva G, Weber E, Becker K, Rupprecht C, Neunlist M, Schemann M. Different tachykinin receptors mediate chloride secretion in the distal colon through activation of submucosal neurones. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 1999;359:71–79. doi: 10.1007/pl00005327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieling T, Wood JD, Cooke HJ. Submucosal reflexes: distension-evoked ion transport in the guinea pig distal colon. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;263:G91–96. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.1.G91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings M, Schultheiss G, Diener M. Electrogenic Ca2+ entry in the rat colonic epithelium. Pflügers Archiv. 1999;439:39–48. doi: 10.1007/s004249900159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness JB, Kunze WA, Bertrand PP, Clerc N, Bornstein JC. Intrinsic primary afferent neurons of the intestine. Progress in Neurobiology. 1998;54:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon MD. Review article: roles played by 5-hydroxytryptamine in the physiology of the bowel. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1999;13(suppl. 2):15–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grider JR, Jin JG. Distinct populations of sensory neurons mediate the peristaltic reflex elicited by muscle stretch and mucosal stimulation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:2854–2860. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02854.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschossmann JM, Chaban VV, McRoberts JA, Raybould HE, Young SH, Ennes HS, Lembo T, Mayer EA. Mechanical activation of dorsal root ganglion cells in vitro: comparison with capsaicin and modulation by kappa-opioids. Brain Research. 2000;856:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, McBride DW. The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacological Reviews. 1996;48:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P. Capsaicin as a tool for studying sensory neuron functions. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 1991a;298:3–16. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-0744-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P. Capsaicin: cellular targets, mechanisms of action, and selectivity for thin sensory neurons. Pharmacological Reviews. 1991b;43:143–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin JG, Foxx OA, Grider JR. Propulsion in guinea pig colon induced by 5-hydroxytryptamine (HT) via 5-HT4 and 5-HT3 receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1999;288:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchgessner AL, Tamir H, Gershon MD. Identification and stimulation by serotonin of intrinsic sensory neurons of the submucosal plexus of the guinea pig gut: activity-induced expression of Fos immunoreactivity. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12:235–248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00235.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WA, Clerc N, Bertrand PP, Furness JB. Contractile activity in intestinal muscle evokes action potential discharge in guinea-pig myenteric neurons. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:547–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0547t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WA, Clerc N, Furness JB, Gola M. The soma and neurites of primary afferent neurons in the guinea-pig intestine respond differentially to deformation. Journal of Physiology. 2000;526:375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunze WA, Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and regulation of intestinal motility. Annual Review of Physiology. 1999;61:117–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara A, Cooke HJ. Tachykinin-induced anion secretion in guinea pig distal colon: role of neural and inflammatory mediators. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1990;252:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZS, Furness JB. Immunohistochemical localisation of cholinergic markers in putative intrinsic primary afferent neurons of the guinea-pig small intestine. Cell and Tissue Research. 1998;294:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s004410051154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax AE, Furness JB. Neurochemical classification of enteric neurons in the guinea-pig distal colon. Cell and Tissue Research. 2000;302:59–72. doi: 10.1007/s004410000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNaughton WK, Moore B, Vanner S. Cellular pathways mediating tachykinin-evoked secretomotor responses in guinea pig ileum. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;273:G1127–1134. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.5.G1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel K, Reiche D, Schemann M. Projections and neurochemical coding of motor neurones to the circular and longitudinal muscle of the guinea pig gastric corpus. Pflügers Archiv. 2000;440:393–408. doi: 10.1007/s004240000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neunlist M, Dobreva G, Schemann M. Characteristics of mucosally projecting myenteric neurones in the guinea-pig proximal colon. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:533–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0533t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neunlist M, Frieling T, Rupprecht C, Schemann M. Polarized enteric submucosal circuits involved in secretory responses of the guinea-pig proximal colon. Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:539–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.539bw.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neunlist M, Schemann M. Projections and neurochemical coding of myenteric neurons innervating the mucosa of the guinea pig proximal colon. Cell and Tissue Research. 1997;287:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s004410050737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neunlist M, Schemann M. Polarised innervation pattern of the mucosa of the guinea pig distal colon. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;246:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Gershon MD. Activation of intrinsic afferent pathways in submucosal ganglia of the guinea pig small intestine. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:3295–3309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03295.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang Q, Williamson S, Young HM. Projections of chemically identified myenteric neurons of the small and large intestine of the mouse. Journal of Anatomy. 1997;190:209–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19020209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemann M, Sann H, Schaaf C, Mader M. Identification of cholinergic neurons in enteric nervous system by antibodies against choline acetyltransferase. American Journal of Physiology. 1993;265:G1005–1009. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1993.265.5.G1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemann M, Schaaf C. Differential projection of cholinergic and nitroxidergic neurons in the myenteric plexus of guinea pig stomach. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:G186–195. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.2.G186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulzke JD, Riecken EO, Fromm M. Distension-induced electrogenic Cl− secretion is mediated via VIP-ergic neurons in rat rectal colon. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;268:G725–731. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.268.5.G725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma RV, Chapleau MW, Hajduczok G, Wachtel RE, Waite LJ, Bhalla RC, Abboud FM. Mechanical stimulation increases intracellular calcium concentration in nodose sensory neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;66:433–441. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00560-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhu M, Cooke HJ. Role for 5-HT and ACh in submucosal reflexes mediating colonic secretion. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:G346–351. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.3.G346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TK, McCarron SL. Nitric oxide modulates cholinergic reflex pathways to the longitudinal and circular muscle in the isolated guinea-pig distal colon. Journal of Physiology. 1998;512:893–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.893bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TK, Robertson WJ. Synchronous movements of the longitudinal and circular muscle during peristalsis in the isolated guinea-pig distal colon. Journal of Physiology. 1998;506:563–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.563bw.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song ZM, Brookes SJ, Steele PA, Costa M. Projections and pathways of submucous neurons to the mucosa of the guinea-pig small intestine. Cell and Tissue Research. 1992;269:87–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00384729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RJ, Publicover NG, Smith TK. Induction and organization of Ca2+ waves by enteric neural reflexes. Nature. 1999;399:62–66. doi: 10.1038/19973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki M, Nakayama S. Effects of capsaicin on myenteric neurons of the guinea pig ileum. Neuroscience Letters. 1989;105:125–130. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki M, Nakayama S. Electrical behavior of myenteric neurons induced by mesenteric nerve stimulation in the guinea pig ileum. Acta Medica Okayama. 1990;44:257–261. doi: 10.18926/AMO/30450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanner S, MacNaughton WK. Capsaicin-sensitive afferent nerves activate submucosal secretomotor neurons in guinea pig ileum. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:G203–209. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.2.G203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucchi MG, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. Differentiation of cholinergic cells in the rat gut during pre- and postnatal life. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;206:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)12440-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD. Physiology of the enteric nervous system. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 423–482. [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD, Alpers DH, Andrews PL. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology. Gut. 1999;45:II6–II16. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SH, Ennes HS, Mayer EA. Mechanotransduction in colonic smooth muscle cells. Journal of Membrane Biology. 1997;160:141–150. doi: 10.1007/s002329900303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan SY, Furness JB, Bornstein JC, Smith TK. Mucosal distortion by compression elicits polarized reflexes and enhances responses of the circular muscle to distension in the small intestine. Journal of the Autonomic Nervous System. 1991;35:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(91)90100-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]