Abstract

The effect of added inorganic phosphate (Pi, range 3–25 mm) on active tension was examined at a range of temperatures (5–30 °C) in chemically skinned (0.5 % Brij) rabbit psoas muscle fibres. Three types of experiments were carried out.

In one type of experiment, a muscle fibre was maximally activated at low temperature (5 °C) and its tension change was recorded during stepwise heating to high temperature in ≈60 s. As found in previous studies, the tension increased with temperature and the normalised tension-(reciprocal) temperature relation was sigmoidal, with a half-maximal tension at 8 °C. In the presence of 25 mm added Pi, the temperature for half-maximal tension of the normalised curve was ≈5 °C higher than in the control. The difference in the slope was small.

In a second type of experiment, the tension increment during a large temperature jump (from 5 to 30 °C) was examined during an active contraction. The relative increase of active tension on heating was significantly higher in the presence of 25 mm added Pi (30/5 °C tension ratio of 6–7) than in the control with no added Pi (tension ratio of ≈3).

In a third type of experiment, the effect on the maximal Ca2+-activated tension of different levels of added Pi (3–25 mm) (and Pi mop adequate to reduce contaminating Pi to micromolar levels) was examined at 5, 10, 20 and 30 °C. The tension was depressed with increased [Pi] in a concentration-dependent manner at all temperatures, and the data could be fitted with a hyperbolic relation. The calculated maximal tension depression in excess [Pi] was ≈65 % of the control at 5–10 °C, in contrast to a maximal depression of 40 % at 20 °C and 30 % at 30 °C.

These experiments indicate that the active tension depression induced by Pi in psoas fibres is temperature sensitive, the depression becoming less marked at high temperatures. A reduced Pi-induced tension depression is qualitatively predicted by a simplified actomyosin ATPase cycle where a pre-phosphate release, force-generation step is enhanced by temperature.

It is well known that contraction of intact mammalian muscle is temperature sensitive so that the maximal tetanic tension (= force) increases ≈twofold on warming from ≈10 to > 30 °C (Hajdu, 1951; Ranatunga & Wylie, 1983). The same basic observation has been made on Ca2+-activated skinned fibres where the temperature range could be extended to lower temperatures (Stephenson & Williams, 1981, 1985). Experiments on skinned fibres have also shown that the active tension-temperature relation is sigmoidal (Ranatunga, 1996, and references therein). However, there is some uncertainty about whether this was due to fibre deterioration and/or product accumulation (e.g. Pi) at high temperatures, and there has not been a systematic study on the effect of Pi on this relation. An increase in [Pi] has been shown to depress active tension in skinned muscle fibres (Rüegg et al. 1971; Cooke & Pate, 1985; Hibberd et al. 1985) and in myofibrils (Tesi et al. 2000). Consequently, accumulation of Pi during active contraction is considered an important factor underlying muscle fatigue (Godt & Nosek, 1989). Additionally, a number of experiments have shown that Pi release during ATP-hydrolysis is closely coupled to crossbridge force generation in muscle fibres but that force generation occurs during a step prior to Pi release (Fortune et al. 1991; Kawai & Halvorson, 1991; Dantzig et al. 1992). The crossbridge force-generation step itself has been shown to be endothermic (Goldman et al. 1987; Davis & Harrington, 1987; Bershitsky & Tsaturyan, 1992; Zhao & Kawai, 1994; Ranatunga, 1996).

In view of the above observations from different types of experiments, it is important to examine the temperature dependence of the Pi-induced depression of tension in mammalian muscle fibres. This was the primary aim of the present study. Experiments were done on single skinned muscle fibres isolated from the psoas muscle of the rabbit, and the effect of added Pi was examined over a wide temperature range (5–30 °C), adopting three different experimental protocols. Our main finding is that the Pi-induced depression of maximal active tension is reduced at higher temperatures so that the tension- (reciprocal) temperature relation is shifted in the presence of added Pi. Preliminary reports of these experiments have been published as abstracts (Coupland et al. 1999; Puchert et al. 1999).

METHODS

Bundles of fibres were obtained from the psoas muscles of adult male rabbits that were killed by an intravenous injection of an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone; different tissues from the animal were taken by other researchers. The bundles were chemically skinned using 0.5 % Brij 58 and prepared as described previously (Fortune et al. 1989). The trough system, the force transducer design and other aspects of the apparatus used in the experiments have been fully described elsewhere (Ranatunga, 1994, 1996). The solution temperature of the activating trough was maintained (± 0.5 °C) at a given experimental temperature (range 5–30 °C) by means of thermo-electric modules (Peltier units), and it was monitored by a thermocouple. The solution temperature in relaxing and pre-activating troughs was typically maintained by cooling fluid at a low level (< 10 °C) since it improved fibre stability.

The solutions contained 10 mm glycerol-2-phosphate (as a temperature-insensitive pH buffer; see Goldman et al. 1987), 6–7 mm magnesium acetate, 5.5 mm ATP, 12.5 mm creatine phosphate (and 1–2 mg ml−1 of creatine kinase), 15 mm EGTA (relaxing solution) or CaEGTA (activating solution) or HDTA (pre-activating solution), 10 mm glutathione and ≈50 mm potassium acetate. Potassium acetate was replaced with K2HPO4 in solutions with added Pi (ionic strength = equals; 200 mm; pH = equals; 7.1). Solution compositions were calculated by using a computer program for solving multi-equilibria, maintaining ionic strength and - in activating solutions - the desired free Ca2+ concentration (≈0.032 mm). Solutions also contained 4 % Dextran (mol. mass ≈500 kDa) to compress the filament lattice spacing in the fibres to normal dimensions (Maughan & Godt, 1979).

The outputs of the tension transducer and the thermocouple in the activating trough were examined on a digital cathode ray oscilloscope and digital voltmeters and recorded using a PC based computer (486, CENCE systems) with a CED 1401 (plus) laboratory interface (Cambridge Design Ltd, Cambridge, UK).

Experimental protocols and data analyses

A short segment (≈2–3 mm) of a single fibre was set up for tension recording by attaching it (using nitro-cellulose glue) between two metal hooks, one connected to the force transducer, the other to a servomotor. Sarcomere length was set to 2.5–2.6 μm in the relaxed fibre using He-Ne laser diffraction; fibre length and width (and in some cases, the fibre depth) were determined by optical microscopy and were used in calculating the fibre cross-sectional area. In addition to the control experiments given below in the Methods, three different experimental protocols were adopted in the study.

- In one type of experiment, a muscle fibre was maximally Ca2+ activated at < 5 °C and the temperature was rapidly increased to ≈30 °C in steps of ≈5 °C; the fibre was relaxed immediately after heating. The heating was achieved either by thermo-electric modules (see Ranatunga, 1994) or by laser temperature jumps coupled with thermo-electric module heating in the front trough (Ranatunga, 1996). The total duration of a contraction was 40–60 s; the steady tension before and after a temperature step was measured and the protocol was repeated with and without 25 mm added Pi. In order to characterise the tension (P)-temperature relation, the measurements from these experiments were fitted with a general sigmoidal curve of the form:

where ΔH is enthalpy change, R is 8.314 J mol−1 K−1, 1/T is reciprocal absolute temperature, and 1/T50 is reciprocal absolute temperature corresponding to 50 % tension; Pmax is 1 when the tension in a fibre was normalised to that at 30 °C.

In a second type of experiment, the change in steady active tension in response to a large temperature jump (T-jump) was examined. A fibre was initially activated at 4–6 °C in one of the back-troughs in the assembly. After steady tension was reached, it was transferred to the front trough which was filled with activating solution of the same composition but temperature clamped at 30 °C. The fibre was then relaxed and the same procedure repeated with/without 25 mm added Pi. From such data, the high/low temperature tension ratios were determined with and without Pi for comparison with results from the previous experiment.

- In a third series, the effect of different concentrations of added Pi on maximally active steady-state tension was examined at different temperatures. A fibre was transferred from relaxing solution, to pre-activating solution and then to activating solution, all solutions containing 3.12, 6.25, 12.5 or 25 mm added Pi or no added Pi (control). Control tension was measured in solutions with no added Pi before and after the series at different phosphate concentrations; data from fibres where the control tension during a series declined more than 15 % were excluded. All the tensions in a series were normalised to that in the first control contraction. The normalised tension versus[Pi] data were fitted with a hyperbolic relation. The equation used was:

where P is normalised tension, Pmax is maximum tension level (i.e. for zero [Pi], Pmin is minimum tension level (i.e. for excess [Pi]) and Kd is [Pi] for half-tension level (i.e. (Pmax+Pmin)/2). The Pi concentration in control solutions (i.e. with no added Pi) was assumed to be 0.5 mm in these analyses due to contamination; the Pi level within active fibres was calculated for different temperatures (see below).

One-way or two-way analyses of variance with post hoc significance tests, as appropriate, were carried out to determine differences in mean values with respect to temperature and/or [Pi]; P≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Control experiments and some general considerations

With a total EGTA concentration of 15 mm, free [Ca2+] may be assumed to be well buffered in both control and Pi-added solutions (see Millar & Homsher, 1990). However, the apparent stability constant of CaEGTA is known to change slightly with temperature (an increase of < 0.01 per °C; see Harrison & Bers, 1989). Therefore we carried out control experiments on 19 fibres to examine whether the [Ca2+] in ‘normal’ activating solutions was adequate for maximal activation, particularly at high temperature and with added Pi. The steady tension with and without 25 mm added Pi was determined at different free [Ca2+]; maximal calcium activating solution (ca pCa 4.5) was mixed with relaxing solution (ca pCa 8) to obtain a range of pCa values. These experiments were done at two different temperatures, 12 and 24 °C, selected to represent low and high temperature ranges on the basis of temperature dependence of active tension in mammalian muscle (Ranatunga & Wylie, 1983; Goldman et al. 1987). The data (not reported here) at each temperature were analysed by fitting the Hill equation, and taking different apparent stability constants for CaEGTA in the calculation of pCa values for 12 and 24 °C (6.56 and 6.7, respectively). The results showed that the tension in pCa 4.5 solution reached the steady maximal level with and without 25 mm added Pi and at 12 and 24 °C; the full range of the pCa for 50 % tension was 5.9–6.3, and the slope (n in Hill's equation) was 2–6. Hence we assumed that activation in pCa 4.5 solution was maximal for the whole range of temperatures used.

Control buffer solutions with no added Pi contain ≈0.5–0.8 mm of free Pi (0.5 mm - Millar & Homsher, 1990; ≈0.8 mm - Dantzig et al. 1992), due to contamination derived largely from creatine phosphate and ATP. Our solutions contained similar levels of ATP (≈5 mm) and a slightly lower level of creatine phosphate (12.5 mm) to those used in these studies (5 mm ATP, 15 mm creatine phosphate). We therefore assumed that our control solutions contained 0.5 mm Pi (the lower of the two estimates) due to contamination. In a number of control experiments at 10 °C, we compared the steady active tension in normal control solutions and in control solutions incubated with a ‘Pi mop’. Two Pi mops were used, 1–2 mm of 7-methylguanosine (MEG) and 1–2 U ml−1 purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP) (Nixon et al. 1998) and sucrose phosphorylase (0.1–0.8 U ml−1 and 10 mm sucrose, Pate & Cooke, 1989; Millar & Homsher, 1990). This Pi mop enzyme concentration was substantially higher than those used in previous studies and accordingly the Pi level was assumed to be reduced to an insignificant level. The Pi mops were added to control solutions > 60 min before their use; it was found that in every fibre the maximal steady tension was higher in Pi mop solutions, indicating that normal control solutions did contain some free Pi.

- Previous studies also assumed that an additional 0.2 mm level of Pi was generated across an active muscle fibre of typical dimensions (fibre width of 70 μm) at 10 °C, arising from ATP hydrolysis during isometric contraction (Pate & Cooke, 1989). On that basis, the Pi level within fibres using our control solutions at 10 °C would be 0.7 mm Pi (0.5 + 0.2 mm). However, since the average fibre width for our preparations was smaller (see below) and in order to correct for different temperatures, we repeated this calculation. As given by Pate & Cooke (1989), the equation relating Pi generated at radius r from the centre in a fibre of width w is:

where m is myosin head concentration (taken here as 150 μm, He et al. 1997), Vmax is maximum ATPase rate per head (taken as 3 s−1 at 10 °C, He et al. 1999), [ATP] is 5 mm, Km is the Michaelis-Menten constant for ATPase (taken as 20 μm, Pate & Cooke, 1989) and D is the diffusion coefficient for Pi at 10 °C (taken as 2.1 × 10−6 cm2 s−1, Pate & Cooke, 1989); w was taken as 59 μm (mean ±s.e.m. from 50 fibres - average of three measurements per fibre - was 59 ± 1.6 μm). Averaging Pi concentration across the fibre (see Pate & Cooke, 1989), the Pi level generated was 0.235 mm at 10 °C: the data points obtained with Pi mop present were plotted at this [Pi]. Thus, when using our control solutions at 10 °C, the Pi level within fibres would be 0.735 mm (0.5 + 0.235 mm), and the within-fibre Pi levels in other solutions would be x+ 0.735 mm, where x is added Pi. Similar calculations were made for other temperatures, taking a Q10 of 3 for the ATPase rate (He et al. 1997) and of 1.3 (due to decrease of viscosity of water) for D. Thus, [Pi] across the active fibre is 1.2 mm at 30 °C, so that the [Pi] in our control solution recordings would be 1.7 mm at this temperature. These values are used in examination of the data, but the general trends reported and discussed here are not qualitatively affected by slight discrepancies in the actual values.

The average length of fibre segments used was ≈2 mm (mean ±s.e.m., 2.1 ± 0.09 mm, n = 50), so that the fibre volume generating Pi was a very small fraction (≈1/10 000) of the buffer volume bathing it (50–60 μl); thus diffusion of Pi generated by fibres had minimal effect on the buffer [Pi].

In most fibres we measured the half-time of tension rise when the fibre is transferred from pre-activating to activating solution. Such measurements have been found to show differences between fast and slow mammalian fibres in previous studies (Stephenson & Williams, 1981). The mean ±s.d. of the half-time was 525 ± 160 ms (n = 38) at 10–12 °C. In comparison with similar measurements from slow fibres in soleus (> 1 s at 10 °C; M. E. Coupland & K. W. Ranatunga, unpublished data), the fibres used here are fast fibres, although which category of myosin isoform they contained remains unknown as we did not determine the myosin isoform type in these fibres. Thus, some of the variability in our data may have arisen from this uncertainty.

Sarcomere length was not recorded during active contractions in these experiments, since this required an increased duration of contraction for setting the diffraction pattern recording system. The fibres were, however, regularly examined under the microscope; data from fibres that showed damage and/or irregularities were excluded.

Simulation of active tension

A minimal actomyosin ATPase cycle, which was used in the simulation of Pi-release-induced tension transients at constant temperature (Dantzig et al. 1992), was extended to determine the temperature dependence of steady tension at different Pi levels and the Pi dependence of tension at different temperatures. It consisted of three actomyosin/crossbridge states (1–3) in a linear scheme as:

|

The scheme we used before for simulating T-jump transients (Ranatunga, 1999) differed only in having an additional pre-force-generating step. This is found to be non-essential for the present purpose; the basic tension behaviour is predicted by changes in two equilibria (steps I and II). Step I is a moderately fast, temperature-sensitive (endothermic) force-generating step and its reverse rate constant kb was taken as 135 s−1 from the temperature-jump study (Ranatunga, 1999). To simulate temperature effects, the forward rate constant ka was changed with a Q10 of 3 (Ranatunga, 1996; corresponds to an activation enthalpy of ≈80 kJ K−1). Step II is a rapid release of phosphate, where kc was set as 103 s−1 and kd was changed to simulate different [Pi] levels; the range of kd values used corresponds to a second order rate constant of 0.6 × 105m−1 s−1 for Pi binding. Step III, i.e. AM*.ADP → AM.ADP.Pi, was taken as irreversible and rate limiting (ke, 10 s−1): it represents all the steps necessary to reprime the crossbridges for the next cycle. According to the scheme, state 1 (M/AM.ADP.Pi) is a low force state whereas states 2 and 3 (AM*.ADP.Pi and AM*.ADP) are high (and equal) force states. The fractional occupancy in the three states was calculated using the equations given by Dantzig et al. (1992; p. 272) for a selected number of temperatures (range 0–40 °C) and Pi levels (0.1–100 mm). Thus, the sum of the fractional occupancy of states 2 and 3 was taken to represent muscle force and it was calculated as:

The matrix method as adapted for solving transient reaction kinetics (Gutfreund & Ranatunga, 1999) could also be employed and it gave similar results (not reported here) when the tension level at 1–2 s after a simulated T-jump or Pi perturbation was determined under various conditions to define the steady tension behaviour. All the simulations were done using Mathcad2000 software (Mathsoft).

RESULTS

Tension-temperature relation

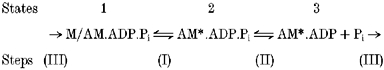

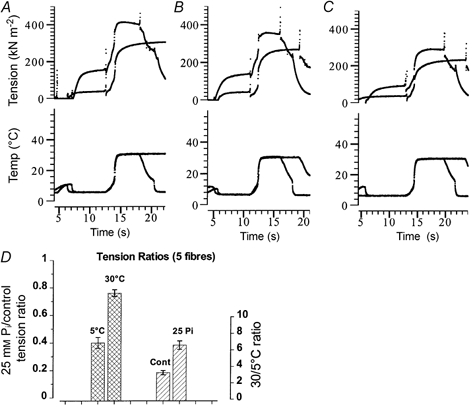

Figure 1A shows tension traces from a muscle fibre that was maximally Ca2+ activated at 2 °C (not shown) in the control solution (no added Pi) and then heated with seven rapid (0.2 ms) laser temperature jumps (T-jumps) of 3–4 °C at intervals of 5–10 s. Note that the tension increment for each temperature jump is less at higher temperature (Goldman et al. 1987; Ranatunga, 1996). Figure 1B shows continuous records of tension and temperature from another fibre that was initially activated at 5 °C and was then heated to 30–32 °C using six 4–5 °C T-jumps + clamps before relaxing (not shown). The traces show that the tension was depressed with 25 mm Pi, but a sharp increase of tension with heating occurred in both control (upper) and with Pi.

Figure 1. Active tension recording at a number of temperatures.

A, sample tension records from a fibre; the fibre was maximally Ca2+ activated at 2 °C (not shown) and temperature was increased by (3–4 °C) laser temperature jumps, while the Peltier T-clamp was set to rise to 30 °C. Superimposed tension transients in response to each T-jump (and the end-temperature) are shown. The fibre was relaxed after the final T-jump (at 30 °C, top trace) and the total duration of contraction was ≈60 s. Note that the relative amplitude of the tension rise to a standard T-jump decreased at higher temperatures. B, two superimposed tension records from a fibre, which was activated at 5 °C and heated to 30 °C, by 4–5 °C laser T-jumps and T-clamps (see Ranatunga, 1996); the fibre was relaxed soon afterwards (not shown). Only one temperature trace (bottom panel) is shown for clarity; it was made using a thermocouple placed close to the muscle fibre. The active force at 5 °C was depressed by 40–50 % in the presence of 25 mm Pi (lower trace), but the marked rise of tension with heating can be seen in both this trace and in the control (no added Pi, upper trace); the relative Pi-induced depression is less at higher temperatures.

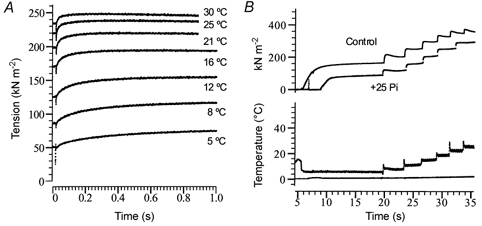

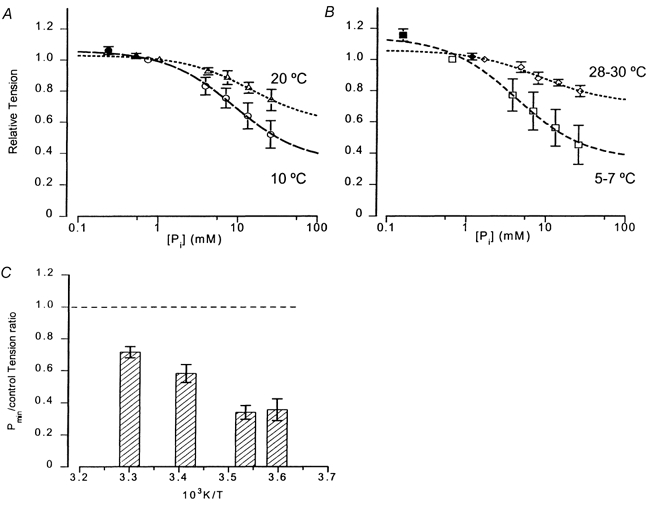

Pooled data from similar experiments on five fibres are shown in Fig. 2. The tensions recorded at other temperatures are normalised to that at 30 °C and control data are shown as filled circles and those with 25 mm added Pi as open symbols (open circles before a control, open squares after a control). The data from control contractions and the sigmoidal curve fitted to them show that 50 % tension occurs at ≈8 °C; the slope of the curve corresponds to an enthalpy change (ΔH; see Methods) of ≈140 kJ mol−1 K−1. The temperature for 50 % tension in the presence of 25 mm added Pi was 13–15 °C, and ΔH was ≈120 kJ mol−1 K−1. In comparison to the control data, the tension data in the presence of 25 mm added Pi are displaced to a higher temperature, and this is more pronounced in the data collected after the control; the change in the slope is not as marked.

Figure 2. Active tension versus temperature relation - effect of [Pi].

Pooled data from five fibres in each of which tension data were collected at different temperatures (range ≈5–30 °C) during one control and one or two test (25 mm Pi) contractions. A fibre was activated at ≈5 °C, and the temperature raised by laser T-jumps and/or Peltier heating (see Fig. 1). A, tensions recorded in each contraction were normalised to that at 30 °C, and plotted against reciprocal absolute temperature in the abscissa (also labelled in °C). Note that, within the range 2.5–32.5 °C, each fibre contributes only one data point per 5 °C temperature interval (i.e. for 2.4–7.4 °C, for 7.5–12.4 °C, etc.), but two to three data points outside this range are also plotted. Filled circles and continuous curve are from activation in control solutions (no added Pi); open circles and dashed curve are from activation in 25 mm Pi solutions prior to control activation; open squares and dotted curve are from activation in 25 mm Pi after a control activation. The fitted sigmoidal curves (see Methods) correspond to temperatures for 50 % tension of 8 °C for control and 13–15 °C for Pi curves; the slope corresponds to ΔH (in kJ mol−1 K−1) of 143 in control, 116–124 with Pi. Thus, Pi seems to shift the tension-temperature relation to higher temperatures. B, control data (•) are as shown in A. The tensions in the presence of 25 mm Pi from two series (i.e. before and after control) were adjusted to the depression obtained at 30 °C: they were pooled and the open symbols are the means and the error bars, standard deviations. Note that the relative Pi-induced depression of tension was less at the higher temperatures. The tension data with and without Pi and at different temperatures were significantly different (P < 0.05). C, tension recorded in 25 mm Pi was presented as a ratio of that in control solution and mean (±s.e.m.) tension ratios from the five fibres are shown for 30, 20, 10 and 5 °C. Differences in the ratios at 30 °C and 5–10 °C were significant (P < 0.001).

The two data sets with added Pi are pooled in Fig. 2B and the tensions are adjusted to the Pi-induced tension depression at 30 °C (see below). In the range of 2.4–32.5 °C, the tension and temperature values within 5 °C temperature bins were pooled and mean (± standard deviation, s.d.) values are shown by the symbols and error bars. The control data are the same as in Fig. 2A. The data show that 25 mm Pi had a marked effect on the active tension-temperature relation, and that the Pi-induced tension depression was temperature sensitive. This is examined in Fig. 2C, where 25 mm Pi/control tension ratios for 30, 20, 10 and 5 °C are shown as histograms. The 25 mm Pi/control tension ratio at 30 °C was 0.84 ± 0.06, (mean ±s.e.m.), whereas it was reduced to 0.5 ± 0.03 at 10 °C (P < 0.001). For the purpose of characterising the relation, particularly for comparison with data in the next experiment (see below), the 30/5 °C tension ratios were calculated. As expected from the shift in the relation seen previously with 25 mm Pi, the 30/5 °C tension ratio from the above experiments was 2.5–3.5 in the control whereas it was higher (5–8) with 25 mm added Pi.

Large temperature jump experiments

Recording active contraction at high temperature (≈30 °C) is difficult in skinned fibre experiments and leads to some loss of maximum tension in subsequent contractions: thus, determination of Pi-induced depression is affected by this fibre deterioration. In the above experiments, the 25 mm Pi/control tension ratio at 30 °C was 0.93 ± 0.04 for Pi data collected before the control, whereas it was 0.75 ± 0.09 for data collected after the control. Therefore, the validity of the general trends observed above was examined by adopting a different experimental protocol that allowed tensions at high and low temperature to be recorded within a relatively short time interval (≈10 s). A fibre was activated at 4–6 °C in one trough and then transferred to the front trough containing the same activating solution but temperature clamped at 30 °C: the fibre was then relaxed at 4–5 °C. Figure 3 shows experimental records from this type of large temperature-jump experiment on one fibre, where tension records are shown in the upper frames and the temperature records in the lower frames. The two records shown in each frame are from two succeeding contractions, one in 25 mm Pi activating solution (smaller tension amplitude) and the other, in control activating solution recorded 15–20 min previously. The three pairs of records in Fig. 3 show contractions 1 and 2 (A), 3 and 4 (B) and 7 and 8 (C). It can be seen that the control tension at 30 °C in the seventh contraction is ≈70 % of the first, but the general features of the Pi-induced effects are present. Despite the tension decline, there was still a difference in the 35/≈5 °C tension ratio between the control (2–4) and with 25 mm Pi (6–7) in 10 contractions.

Figure 3. Large T-jump experiments and tension decline.

A–C, the fibre was activated at low temperature (4–6 °C) in a rear trough and T-jumped by transferring to the front trough containing the same activation solution clamped at 30 °C; the fibre was then relaxed (not shown completely in all cases). The procedure was repeated at intervals of 15–20 min, activation in alternate contractions being in the presence of 25 mm Pi. A thermocouple placed within 0.2 mm of the fibre, that moved with the fibre, provided the temperature records (lower frames); the temperature record provides an approximate indication of the temperature that a fibre gets exposed to during this procedure. Each frame contains a pair of records, one in control solution (larger tension trace) and the other in 25 mm Pi-containing activating solution. The sequence of recording was: A, contractions 1 and 2, B, contractions 3 and 4 and C, contractions 7 and 8. Note that compared to the control tension, the tension with Pi was reduced more at low temperature than at 30 °C. (For convenient comparison, traces in a frame were horizontally displaced so as to synchronise the T-jump in a pair. The first two contractions were recorded without creatine kinase (CK); 2–3 mg ml−1 CK was present for the other recordings.) D, pooled data from five fibres. Only the first four contractions were taken for the analyses. Cross-hatched bars and left ordinate show the 25 mm Pi/control tension ratios from each contraction (mean ±s.e.m., n = 8) at 4–6 °C and 30 °C. The tension in the presence of 25 mm Pi is ≈80 % of control at 30 °C, whereas it was ≈40 % at ≈5 °C. Hatched bars and right ordinate show the 30/≈5 °C tension ratios for control and 25 mm Pi contractions: thus the tension increased by threefold in the control, but it increased by six to sevenfold in the presence of 25 mm Pi when the temperature was raised from 5 °C to 30 °C. Results are basically similar to those obtained in the previous experiment (see Fig. 2C and text).

Figure 3D shows pooled data from five fibres in which large temperature jumps were made, where the tension ratios from the first two pairs of contractions only were taken. The bar chart shows that the 30/5 °C tension ratio is 2–4 in control whereas it is 6–8 with 25 mm Pi (hatched bars and right ordinate). In two of the fibres, such tension ratios were determined in the absence and presence (2–3 mg ml−1) of creatine kinase in the buffers (see Fig. 3 legend); the ratios were very similar, indicating that ADP accumulation per se (e.g. at high temperature) may not have significantly altered the basic observation. Additionally, the 25 mm Pi/control tension ratios from this type of experiment also are clearly different at low and high temperatures (cross-hatched bars and left ordinate). The tension depression induced by 25 mm Pi was ≈60 % at 5 °C, whereas it was ≈20 % at 30 °C. These findings are essentially similar to the data presented above from longer contractions (see Fig. 2 and above).

Tension-[Pi] relation at different temperatures

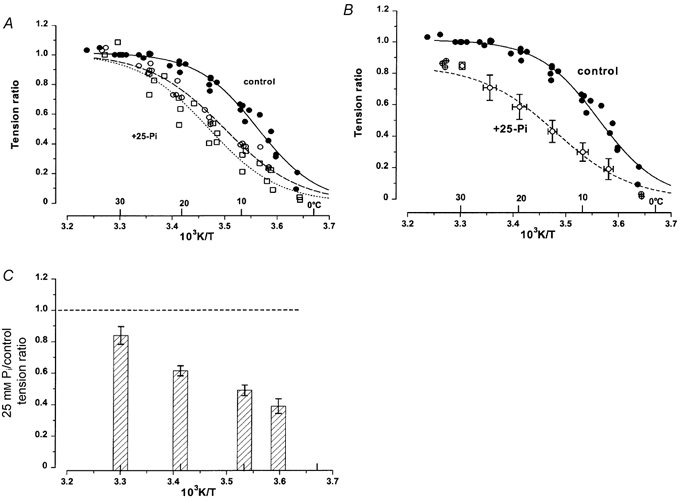

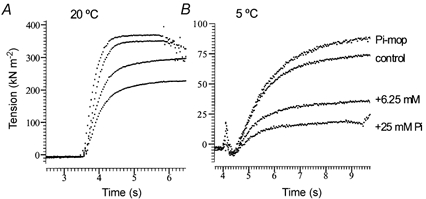

In a separate series of experiments (32 fibres), we examined the tension depression induced by varying levels of added Pi, at a selected number of different steady temperatures (5, 10, 20 and 30 °C): data were collected for more than one temperature in some fibre experiments. Typical tension responses recorded from one fibre at four different levels of [Pi] are shown in Fig. 4A (20 °C) and B (5 °C). The contractions were slower and absolute tensions (see the ordinates) were significantly lower at 5 °C, but the relative tension depression by Pi is much greater.

Figure 4. Effect of [Pi] on active tension.

Sample tension records from a fibre at two different steady temperatures, 20 °C (A) and 5 °C (B). Separate contractions were recorded in activating solutions containing different levels of Pi, after the fibre was pre-equilibrated at the same Pi level in relaxing and pre-activating solutions. Only the activation to a steady tension level is shown for clarity, i.e. the fibre relaxation is not shown. In both A and B, the largest tension record was made in solution containing Pi mop (0.8 U ml−1 of sucrose phosphorylase + 10 mm sucrose; see Methods). The other three records - in sequence of decreasing amplitude - were in the control solution (no added Pi or mop), or solutions with 6.25 mm and 25 mm added Pi. Note that tension rise is slower and the tensions are markedly lower at the low temperature (5 °C, B), but the relative magnitude of the Pi-induced depression is much more pronounced. The control tension at the series end was 99 % at 20 °C and 90 % at 5 °C. (Tension traces were horizontally displaced in order to superimpose the onset of activation.)

The [Pi] dependence of steady maximal active tension was examined in some detail in experiments at 10 °C. Tension data were collected in the control and in each of four Pi-added (3.1, 6.25, 12.5 and 25 mm) solutions in 15 fibres. Data were collected in the control and Pi mop solution in nine fibres, in three of which data were also collected in all the Pi-added solutions. Tensions in each fibre were normalised to that in control solution and the data from 24 fibres pooled; Fig. 5A (circles) shows the mean (±s.d.) normalised tension plotted against [Pi] on a logarithmic abscissa. The curve is the hyperbolic relation (see Methods) fitted to the pooled data and it gives a maximum tension ratio (Pmax) of 1.06, [Pi] for half-tension (Kd) of 9 mm and a minimum tension ratio (Pmin) of 0.34. The triangles represent similar data obtained at 20 °C from 13 fibres, where [Pi] concentrations appropriate for 20 °C were used: the curve fitted gives Pmax of 1.03, Kd of 15 mm and Pmin of 0.58. Thus, Pi-induced tension depression is considerably diminished at the higher temperature (P < 0.01 for 3–25 mm added Pi). Figure 5B shows data for 5 °C (squares) and for 30 °C (diamonds). Unlike at other temperatures, deterioration of the fibre at 30 °C meant that data for a full series of [Pi] could not be obtained from all the fibres; this probably contributed to the greater scatter in the data. Figure 5C shows the mean (±s.e.m.) Pmin value for four temperatures from these experiments; it can be seen that the maximum Pi-induced depression is ≈65 % at 5–10 °C, whereas it is decreased to 40 % at 20 °C and to ≈30 % at 30 °C. The tensions from these fibres, which were only examined at certain steady temperatures, also indicated a marked rise with temperature. Thus, the mean (±s.e.m.) specific tensions (in kN m−2) in control solutions were 134 (± 13, n = 8) at 5–7 °C and 391 (± 13, n = 6) at 28–30 °C; with 25 mm added Pi, the specific tensions were 61 (± 9.6, n = 7) and 311 (± 12, n = 6), respectively.

Figure 5. Active tension versus[Pi] relation at different temperatures.

A, pooled tension data (with their standard deviations) collected for different Pi concentrations at 10 °C (circles, 24 fibres) and at 20 °C (triangles, 13 fibres). Data were collected from each fibre in control solution (no added Pi) and in solutions with 3.1, 6.25, 12.5 and 25 mm added Pi and normalised to the initial control tension (the control tension after a series was (mean ±s.d.) 0.97 ± 0.06 at 10 °C and 0.95 ± 0.05 at 20 °C). The mean (±s.d.) normalised tension is plotted on the ordinate against [Pi] within the fibre on a logarithmic abscissa. For 10 °C, [Pi] was taken as 0.735 mm in the control and as 0.735 mm+ added [Pi] for others; the corresponding values for 20 °C were 1.17 mm (control) and 1.17 mm+ added [Pi] (see Methods). The filled symbols are the normalised tensions obtained with a Pi mop (from nine fibres at 10 °C, three of which also contributed data to the full series, and from four fibres at 20 °C, two of which contributed to the full series; they are plotted at fibre generated [Pi] - see Methods). The curve through each set of points is the hyperbolic relation fitted to the pooled data. The Pmax, Pmin and Kd values (mean ±s.e.m.) from the curve fits are 1.06 ± 0.02, 0.34 ± 0.04 and 8.8 ± 1.5 mm for 10 °C and 1.03 ± 0.01, 0.58 ± 0.06 and 14.6 ± 4.4 mm for 20 °C. Data obtained at more than one temperature in a few individual fibres (n = 6) also indicated the same trends. The difference in the tension reduction with 3–25 mm added [Pi] was significant between the two temperatures (P < 0.01). B, data similar to A, but for 5–7 °C (squares) and for 28–30 °C (diamonds). Curve fits are for pooled data from a total of eight fibres at ≈5 °C (Pi mop from four fibres - filled symbol, two of which also contributed to the full series) and from a total of six fibres at ≈30 °C (Pi mop from three fibres, all contributing to the full series). The Pmax, Pmin and Kd values (mean ±s.e.m.) from the curve fits are 1.14 ± 0.04, 0.36 ± 0.07 and 4.2 ± 1.4 mm for ≈5 °C and 1.06 ± 0.02, 0.71 ± 0.04 and 8.3 ± 3.0 mm for ≈30 °C (P < 0.001). C, predicted tension level (mean ±s.e.m. from curve fit) at excess [Pi], i.e. Pmin, at ≈5, 10, 20 and ≈30 °C; dashed line represents the tension level in the control. Note that the maximum Pi-induced depression is similar between ≈5 and 10 °C, but is markedly decreased at higher temperatures. Differences are significant (P < 0.05) except between 5 and 10 °C and between 20 and 30 °C.

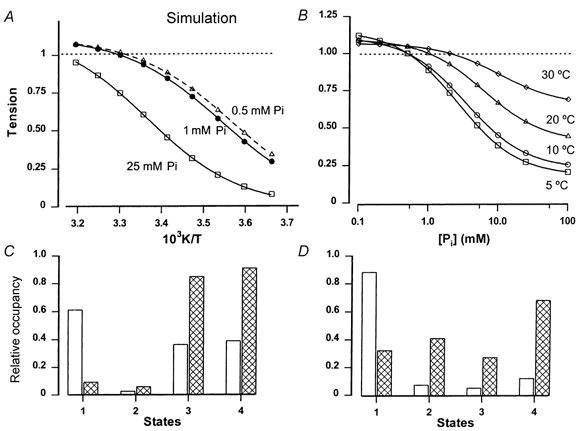

Behaviour of simulated tension in a three-state crossbridge model

A three-state crossbridge model (see Methods) is used here to examine the interactive effects on steady tension of temperature and [Pi] over a wide range (0–40 °C and 0.1–100 mm[Pi]). Figure 6A shows the temperature dependence of steady tension at three different levels of [Pi], 0.5 mm (▵), 1 mm (•) and 25 mm[Pi] (□). The tension versus reciprocal temperature relation appears approximately sigmoidal, and it is shifted to higher temperature with increased [Pi]. The curve fitting shows that the difference in the slope (ΔH, 70–74 kJ mol−1 K−1) is small. Thus, although the actual values are different and the shift in the Pi curve is more marked (see Fig. 6 legend), the basic trends are the same as in the experimental data (see Fig. 2). Figure 6B shows [Pi] dependence of simulated tension at different temperatures. The [Pi] dependence of tension is similar between 5 and 10 °C, but is decreased at the higher temperatures, as observed in the experiments (see Fig. 5); the hyperbolic curves fitted to the calculated tensions show that the Kd and Pmin increase with temperature (see Fig. 6 legend).

Figure 6. Behaviour of simulated tension from a three-state model.

A, plots of calculated tension (symbols) versus reciprocal absolute temperature (full range - 0 to 40 °C, at 5 °C intervals) for a number of different [Pi] levels. Temperature increase was simulated by increasing ka (Q10 3) in the scheme and [Pi] was constant at 0.5 mm (▵), 1 mm (•) and 25 mm (□) by pre-setting kd. Tension normalised to that at 30 °C with 1 mm[Pi] is plotted and sigmoidal curves (see Methods) are fitted through each set of points. The curves give temperatures for 50 % tension of 7.5 °C (0.5 mm Pi), 9.5 °C (1 mm Pi) and 23 °C (25 mm Pi); the slopes correspond to ΔH of 70–74 kJ mol−1 K−1 in the three curves. B, Pi dependence of simulated tension at 5 °C (□), 10 °C (○), 20 °C (▵) and 30 °C (⋄). Tensions are normalised to calculated [Pi] level within the fibre in control solutions; lines are fitted hyperbolic relations to the symbols. Both Kd and Pmin increase with temperature, from 2.6 mm and 0.18 at 5 °C to 10 mm and 0.65 at 30 °C. C, the relative steady-state occupancy of the three crossbridge/actomyosin states at 5 °C (open bars) and 30 °C (cross-hatched bars) with [Pi] pre-set at 1 mm. State 1 is AM.ADP.Pi; state 2, AM*.ADP.Pi; and state 3, AM*.ADP (see Methods). Bars labelled state 4 represent states 2 + 3 (high force states), which is taken as tension; note that 30/5 °C tension ratio is ≈2.3. D, data similar to C, but with [Pi] pre-set at 25 mm. Note that 30/5 °C tension ratio is ≈6.

Figure 6C illustrates in the form of histograms the steady-state fractional occupancy of the three crossbridge/ actomyosin states (states 1–3, see Fig. 6 legend and Methods) at 5 °C (open bars) and at 30 °C (cross-hatched bars) when [Pi] is pre-set at 1 mm. Since, the summed occupancy in states 2 and 3 was taken as tension (shown at state 4), the tension at 30 °C is ≈2.5 times that at 5 °C. Figure 6D shows similar data when [Pi] is pre-set at 25 mm; the 30/5 °C tension ratio is ≈6. These ratios are within the range obtained in the actual experiments illustrated in Fig. 3D.

DISCUSSION

Results herein reported show that, over a wide temperature range of 5–30 °C, the temperature dependence of maximal Ca2+-activated tension of skinned fibres in control solutions (with no added Pi) approximates a sigmoidal curve (Fig. 2). The curvilinear nature of the tension-(reciprocal) temperature relation has been known for some time (see Brown, 1957) and it has been reported from different fibre types in a number of previous studies (see references in Ranatunga, 1996). However, the temperature for half-maximal tension obtained in previous studies was higher (and more variable) than that obtained in this study (≈8 °C). A non-linear tension-temperature relation in skinned fibres could result from uncertainties/inadequacies such as fibre deterioration and accumulation of products that are known to affect their responses at the high temperatures. On the other hand, the present data compare well with those from intact rat muscles where the tetanic tension at ≈10 °C was ≈50–60 % of that at 35 °C (Ranatunga & Wylie, 1983). The agreement with the intact muscle data may probably reflect the fact that the filament lattice in the skinned fibres was compressed to normal dimensions in the present study by using 4 % Dextran (500 kDa) in buffer solutions.

In the presence of 25 mm added [Pi] the normalised tension-reciprocal temperature relation was shifted so that the temperature for half-maximal tension was ≈4–5 °C higher (Fig. 2A); the difference in the slope (ΔH) was small. Consequently, the relative tension increment on heating from 5 °C to 30 °C was more pronounced than in the control contractions (Fig. 3). When compared with control contractions, tension at any temperature was depressed in solutions with 25 mm added [Pi], but the relative depression was less at the higher temperatures (Fig. 2C and Fig. 3C). A reduced tension depression by a standard [Pi] at the higher temperatures was also seen in experiments where individual contractions were recorded at a range of different [Pi] at different steady temperatures (Fig. 4). As reported in the recent experiments of Piroddi et al. (2001) on single myofibrils (see also Fortune et al. 1989; McKillop et al. 1994), the [Pi] dependence of tension at a given temperature could be fitted with a hyperbolic relation (see Fig. 5). Our data show that the predicted minimum tension with an excess of Pi obtained from such curve fitting also decreased with temperature (Fig. 5C), particularly at the higher temperature range (20–30 °C). Myofibrillar experiments at 5 and 15 °C (Piroddi et al. 2001) and our fibre experimental data and simulations at 5–10 °C, on the other hand, do not show a marked change at the low temperatures. The maximal Pi-induced tension depression obtained in myofibrils is clearly larger than in fibres: for example, the Pmin/Pmax tension ratio at ≈5–10 °C is ≈0.3 in our experiments, whereas it is < 0.1 in myofibril experiments (Tesi et al. 2000; Piroddi et al. 2001). The cause of this discrepancy remains unclear, but it may indicate constrained accessibility between the external medium and the inter-filamentary medium in fibres.

As mentioned in the Introduction, it is generally agreed that release of Pi is closely coupled to crossbridge force generation in muscle fibres (however, see Davis & Rodgers, 1995). The scheme that has been proposed from different studies is that the rapid Pi release is preceded by the force-generation step (Fortune et al. 1991; Kawai & Halvorson, 1991; Dantzig et al. 1992). Temperature-jump (T-jump) studies, in particular, have shown that crossbridge force generation is an endothermic event (Goldman et al. 1987; Davis & Harrington, 1987; Bershitsky & Tsaturyan, 1992; see also Zhao & Kawai, 1994; Ranatunga, 1996). The Pi sensitivity of the tension transient induced by a standard T-jump is consistent with the endothermic force generation being a step before Pi release (Ranatunga, 1999). Whether such a minimal three-step scheme would predict our present observations was examined by simulation. Analyses of the steady tension data from such simulations showed that the model predictions and the experimental findings were not identical, but they indicated the same basic trends in relation to the temperature- and Pi-dependent tension behaviours (see Fig. 6). Thus, the tension-temperature relation was non-linear (roughly sigmoidal) and showed saturation at high temperatures and with Pi it was shifted to a higher temperature; the difference in the slope was small. Additionally, Pi-tension relations at different temperatures indicated a decreased Pi-induced tension depression at higher temperatures.

Such similarities between the experimental and the simulated data may be merely coincidental and hence it is relevant to re-examine both the basic features and, at least some of, the underlying assumptions. Firstly, the model consists of two reversible equilibria; a fast Pi-release/binding, preceded by temperature-sensitive (endothermic) force generation. Other steps in the complex ATPase cycle were reduced to a single re-priming process of crossbridges - in order to close the cycle. The steps involved in this re-priming include ADP release and ATP binding and the absolute amplitude of the sigmoidal tension-temperature relation was directly sensitive to this rate constant. It has been found from studies of enthalpy changes in single steps in myosin-ATPase (see Millar et al. 1987 and references therein) that, whereas ADP release is endothermic (ΔH = equals; +36 to +54 kJ mol−1), ATP binding is exothermic (ΔH = equals; −40 to −65 kJ mol−1). Thus, this part of the path may be relatively temperature insensitive. On the other hand, the ATP cleavage step is endothermic (ΔH = equals; +65 kJ mol−1) whereas Pi release is exothermic (ΔH = equals; −75 kJ mol−1). Whether these data from the myosin-ATPase cycle have direct correlates in the actomyosin cycle in fibres remains unclear. Using the sinusoidal length perturbation technique, Wang & Kawai (2001) provided detailed analyses of the ATPase cycle in muscle fibres and they obtained the highest temperature sensitivity (and a value for standard enthalpy of 60 kJ mol−1) for the force-generation step in psoas fibres, as assumed here. The temperature sensitivity of steps other than force generation (see He et al. 1997) may need to be considered more exactly to accommodate the actual observations.

Secondly, a pre-force-generating step was found to be useful in previous studies to accommodate closely related events (e.g. pressure-release experiments, Ranatunga, 1999; tension re-generation after release, Millar & Homsher, 1992); the basic findings here would also be predicted from such a four-step (or five-step) scheme. The tension transient induced by a T-jump also had a slower component of tension rise that was insensitive to [Pi] (see Ranatunga, 1999). None of the models has taken this into account, and it is possible that the discrepancy between the simulated and the observed data is at least partly due to this inadequacy. Thirdly, it remains unclear whether the scheme would be valid for all different fibre types (see below) and/or conditions, since strain-dependent effects have not been considered here. Dantzig et al. (1992) gave particular attention to the strain-dependent characteristics of the force-generation step and showed that the tension response to Pi changes is dominated by crossbridges at a standard limiting value of strain. Our analyses assume that strain dependence remains similar at different temperatures, an over-simplification that requires further examination. Finally, the indication that change of one transition (in the AM.ADP.Pi state) can more or less predict the overall temperature-dependent tension behaviour, with and without added Pi, raises the possibility that temperature induces a structural (conformational) change in crossbridge state(s) and this leads to an apparent change of rate constants. Wang & Kawai (2001) have discussed in detail how endothermic (+ entropic) crossbridge force generation may be produced on the basis of the known crystallographic structure of myosin and actin. It appears that there may be more than one possible structural mechanism, but hydrophobic interactions between residues in myosin and actin have been implicated. It is important to note, also, that - within the same temperature range - the rigor fibre tension is relatively insensitive to temperature (see Ranatunga, 1994), indicating that temperature sensitivity is not the same in different crossbridge states and is altered/ stabilised in the rigor state. Recent studies of Werner et al. (1999) and Malnasi-Csizmadia et al. (2000), indeed, provide evidence of a temperature-dependent conformational change in myosin in solution.

Experiments of Wang & Kawai (2001) show that, except for slow kinetics, the molecular basis of force generation in slow fibres is fundamentally similar to that of the fast fibres. Indeed, a non-linear active tension-temperature relation is obtained in slow fibres (Stephenson & Williams, 1985) and also, T-jump-induced force generation in slow fibres is slower than in fast fibres (Ranatunga, 1996). However, no data are available on the Pi sensitivity of T-jump-induced force generation in slow fibres. Our preliminary results from slow fibres show that Pi-induced tension depression is less than in fast fibres at low temperatures (confirming findings of Millar & Homsher, 1992, and experiments on myofibrils, Piroddi et al. 2001) and the extent of depression at different temperatures remains similar. This may be related to the finding that Pi-induced depression of force and ATP turn-over are equally affected in slow fibres, whereas the effect on force is greater than on ATP turn-over in fast fibres (Potma et al. 1995).

Accumulation of inorganic phosphate and H+ ions (decreased pH) is an outcome of muscle activity in vivo and has been considered a main cause of muscle fatigue (Dawson et al. 1978; Godt & Nosek, 1989). However, attempts to simulate in situ muscle fatigue in skinned fibre experiments have proved difficult (see Myburgh & Cooke, 1997). Previous studies have shown that decreased intracellular pH is less effective at body temperature (Ranatunga, 1987; Pate et al. 1995; Westerblad et al. 1997). Our present results do not shed light directly on the cause(s) of muscle fatigue, but they indicate that Pi-induced tension depression in psoas fibres is less pronounced at physiological temperatures (< 20 % with 25 mm Pi, see Fig. 2C and Fig. 5B).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Wellcome Trust for financial support and to Dr Gerald Offer (Physiology, Bristol) for reading and making valuable suggestions on the manuscript and for helping with data analyses and model calculations. We thank Professor Mike Ferenczi (Imperial College, London) for calculating the compositions of various buffer solutions used in the study, Dr Martin Webb (NIMR, Mill Hill, London) for advice on the use of Pi mops and Dr Lucy Donaldson (Physiology, Bristol) for advice on statistical analyses.

References

- Bershitsky SY, Tsaturyan AK. Tension responses to joule temperature jump in skinned rabbit muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1992;447:425–448. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DES. Temperature-pressure relation in muscular contraction. In: Johnson FH, editor. Influence of Temperature on Biological Systems. Washington: American Physiological Society; 1957. pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R, Pate E. The effects of ADP and phosphate on the contraction of muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1985;48:789–798. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83837-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland ME, Puchert E, Ranatunga KW. Interactive effects of inorganic phosphate and temperature on calcium sensitivity of active force in skinned rabbit muscle fibres. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1999;20:820. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Dantzig JA, Goldman YE, Millar NC, Lacktis J, Homsher E. Reversal of the cross-bridge force-generating transition by photogeneration of phosphate in rabbit psoas muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1992;451:247–278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JS, Harrington W. Force generation by muscle fibers in rigor: a laser temperature-jump study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1987;84:975–979. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.4.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JS, Rodgers ME. Indirect coupling of phosphate release to de-novo tension generation during muscle contraction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1995;92:10482–10486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson MJ, Gadian DG, Wilkie DR. Muscular fatigue investigated by phosphorus nuclear magnetic resonance. Nature. 1978;274:861–866. doi: 10.1038/274861a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune NS, Geeves MA, Ranatunga KW. Pressure sensitivity of active tension in glycerinated rabbit psoas muscle fibres: effects of ADP and phosphate. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1989;10:113–123. doi: 10.1007/BF01739967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune NS, Geeves MA, Ranatunga KW. Tension responses to rapid pressure release in glycerinated rabbit muscle fibers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1991;88:7323–7327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godt RE, Nosek TM. Changes of intracellular milieu with fatigue or hypoxia depress contraction of skinned rabbit skeletal and cardiac muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1989;412:155–180. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman YE, McCray JA, Ranatunga KW. Transient tension changes initiated by laser temperature jumps in rabbit psoas muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1987;392:71–95. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutfreund H, Ranatunga KW. Simulation of molecular steps in muscle force generation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1999;266:1471–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu S. Behaviour of frog and rat muscle at higher temperatures. Enzymologia. 1951;14:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison SM, Bers DM. Correction of proton and Ca association constants of EGTA for temperature and ionic strength. American Journal of Physiology. 1989;256:C1250–1256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1989.256.6.C1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z-H, Chillingworth RK, Brune M, Corrie JET, Trentham DR, Webb MR, Ferenczi MA. ATPase kinetics on activation of rabbit and frog permeabilized isometric muscle fibres: a real time phosphate assay. Journal of Physiology. 1997;501:125–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.125bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z-H, Chillingworth RK, Brune M, Corrie JET, Webb MR, Ferenczi MA. The efficiency of contraction in rabbit skeletal muscle fibres, determined from the rate of release of inorganic phosphate. Journal of Physiology. 1999;517:839–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0839s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd MG, Dantzig JA, Trentham DR, Goldman YE. Phosphate release and force generation in skeletal muscles fibers. Science. 1985;228:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.3159090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M, Halvorson HR. Two step mechanism of phosphate release and the mechanism of force generation in chemically skinned fibers of rabbit psoas muscle. Biophysical Journal. 1991;59:329–342. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82227-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKillop DFA, Fortune NS, Ranatunga KW, Geeves MA. The influence of 2,3-butanedione 2-monoxime (BDM) on the interaction between actin and myosin in solution and in skinned muscle fibres. Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 1994;15:309–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00123483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malnasi-Csizmadia A, Woolley RJ, Bagshaw CR. Resolution of conformational states of Dictyostelium myosin II motor domain using tryptophan (W501) mutants: Implications for the open-closed transition identified by crystallography. Biochemistry. 2000;39:16135–16146. doi: 10.1021/bi001125j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan DW, Godt RE. Stretch and radial compression studies on relaxed skinned muscle fibers of the frog. Biophysical Journal. 1979;28:391–402. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(79)85188-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar NC, Homsher E. The effect of phosphate and calcium on force generation in glycerinated rabbit skeletal muscle fibers. A steady-state and transient kinetic study. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1990;265:20234–20240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar NC, Homsher E. Kinetics of force generation and phosphate release in skinned rabbit soleus muscle fibers. American Journal of Physiology. 1992;262:C1239–1245. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.5.C1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar NC, Howarth JV, Gutfreund H. A transient kinetic study of enthalpy changes during the reaction of myosin subfragment 1 with ATP. Biochemical Journal. 1987;248:683–690. doi: 10.1042/bj2480683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myburgh KH, Cooke R. Responses of compressed skinned skeletal muscle fibers to conditons that simulate fatigue. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1997;82:1297–1304. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.4.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon AE, Hunter JL, Bonifacio G, Eccleston JF, Webb MR. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase: its use in a spectroscopic assay for inorganic phosphate and for removing inorganic phosphate with the aid of phosphodeoxyribomutase. Analytical Biochemistry. 1998;265:299–307. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate E, Bhimani M, Franks-Skiba K, Cooke R. Reduced effect of pH on skinned rabbit psoas muscle mechanics at high temperatures: implications for fatigue. Journal of Physiology. 1995;486:689–694. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate E, Cooke R. Addition of phosphate to active muscle fibers probes actomyosin states within the powerstroke. Pflügers Archiv. 1989;414:73–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00585629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piroddi N, Colomo F, Poggesi C, Tesi C. Force depression by inorganic phosphate in single myofibrils from fast and slow striated muscle. Biophysical Journal. 2001;80:510a. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76845-7. (abstract) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potma EJ, van Graas IA, Steinen GJM. Influence of inorganic phosphate and pH on ATP utilization in fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1995;69:2580–2589. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchert E, Coupland ME, Ranatunga KW. Phosphate-induced depression of active tension in rabbit skinned muscle fibres at different temperatures. Journal of Physiology. 1999;518.P:88P. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga KW. Effects of acidosis on tension development in mammalian muscle. Muscle and Nerve. 1987;10:439–444. doi: 10.1002/mus.880100510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga KW. Thermal stress and Ca-independent contractile activation in mammalian skeletal muscle fibers at high temperatures. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66:1531–1541. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80944-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga KW. Endothermic force generation in fast and slow mammalian (rabbit) muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1996;71:1905–1913. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79389-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga KW. Effects of inorganic phosphate on endothermic force generation in muscle. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1999;266:1381–1385. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga KW, Wylie SR. Temperature-dependent transitions in isometric contractions of rat muscle. Journal of Physiology. 1983;339:87–95. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüegg JC, Schädler M, Steiger GJ, Müller G. Effects of inorganic phosphate on the contractile mechanism. Pflügers Archiv. 1971;325:359–364. doi: 10.1007/BF00592176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson DG, Williams DA. Calcium-activated force responses in fast- and slow-twitch skinned muscle fibres of the rat at different temperatures. Journal of Physiology. 1981;317:281–302. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson DG, Williams DA. Temperature-dependent calcium sensitivity changes in skinned muscle fibres of the rat and toad. Journal of Physiology. 1985;360:1–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesi C, Colomo F, Nencini S, Piroddi N, Poggesi C. The effect of inorganic phosphate on force generation in single myofibrils from rabbit skeletal muscle. Biophysical Journal. 2000;78:3081–3092. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76845-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Kawai M. Effect of temperature on elementary steps of the cross-bridge cycle in rabbit soleus slow-twitch muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:219–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0219j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner J, Urbanke C, Wray J. Fluorescence temperature-jump studies of myosin S1 structures. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:A146. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H, Bruton JD, Lännergren J. The effect of intracellular pH on contractile function of intact, single fibres of mouse muscle declines with increasing temperature. Journal of Physiology. 1997;500:193–204. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Kawai M. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies of the cross-bridge cycle in rabbit psoas muscle fibers. Biophysical Journal. 1994;67:1655–1668. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80638-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]