Abstract

Low threshold, T-type, Ca2+ channels of the Cav3 family display the fastest inactivation kinetics among all voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The molecular inactivation determinants of this channel family are largely unknown. Here we investigate whether segment IIIS6 plays a role in Cav3.1 inactivation as observed previously in high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels.

Amino acids that are identical in IIIS6 segments of all Ca2+ channel subtypes were mutated to alanine (F1505A, F1506A, N1509A, F1511A, V1512A, F1519A, FV1511/1512AA). Additionally M1510 was mutated to isoleucine and alanine.

The kinetic properties of the mutants were analysed with the two-microelectrode voltage-clamp technique after expression in Xenopus oocytes. The time constant for the barium current (IBa) inactivation, τinact, of wild-type channels at −20 mV was 9.5 ± 0.4 ms; the corresponding time constants of the mutants ranged from 9.2 ± 0.4 ms in V1512A to 45.7 ± 5.2 ms (4.8-fold slowing) in M1510I. Recovery at −80 mV was most significantly slowed by V1512A and accelerated by F1511A.

We conclude that amino acids M1510, F1511 and V1512 corresponding to previously identified inactivation determinants in IIIS6 of Cav2.1 (Hering et al. 1998) have a significant role in Cav3.1 inactivation. These data suggest common elements in the molecular architecture of the inactivation mechanism in high and low threshold Ca2+ channels.

Low voltage-activated Ca2+ channels of the Cav3 family (also known as α1G/H/I or T-type channels; Ertel et al. 2000) mediate Ca2+ influx into neurons, endocrine cells and muscle cells. Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated ion channels is affected by the rate of channel inactivation.

High voltage-activated Ca2+ channels such as Cav1.2 and Cav2.1 inactivate by at least two voltage-dependent mechanisms (fast and slow inactivation) and by an additional Ca2+-dependent inactivation (see Hering et al. 2000). Low voltage-activated Ca2+ channels display the fastest inactivation kinetics among all Ca2+ channel subtypes and inactivate in a voltage-dependent manner (Perez-Reyes et al. 1998). As observed with voltage-gated Na+ and high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels, the α1 subunit of T-type channels contains four internal repeats, with each repeat containing six transmembrane segments and a pore loop.

Although there is no direct information on the structure of these α1 subunits, data from the X-ray crystal structure of a potassium channel has been used to glean structural insights (Doyle et al. 1998). Thus, the S6 segments of α1 subunits are thought to line the inner pore as observed with the second transmembrane segments (TM2) of KcsA. These segments are likely to move during channel gating (see Perozo et al. 1998; Yellen, 1999), making them interesting targets for mutagenesis studies. Such studies on high threshold Ca2+ channels have identified a number of important residues in binding of calcium channel blockers, as well as important motifs involved in channel inactivation of Cav2.1 (Hering et al. 1997, 1998; Sokolov et al. 2000; Berjukow et al. 2001). Crucial residues have been identified in segments S5, S6, pore loops (Cens et al. 1999; Sokolov et al. 1999), intracellular domain linkers (Herlitze et al. 1997; Spaetgens & Zamponi, 1999; Stotz et al. 2000), and the carboxy (Soldatov et al. 1998) and amino (Stephens et al. 2000) terminal ends.

The current hypotheses on the mechanisms of high threshold Ca2+ channel inactivation comprise hinged lid mechanisms (I-II loop), ball and chain mechanisms (carboxy terminus), and non-covalent interaction between pore-forming S6 segments (Hering et al. 2000).

In contrast, little is known about the inactivation determinants of the Cav3 family. The data of Staes et al. (2001) suggest a crucial role of the carboxy terminus. Based on our previous studies showing a role of IIIS6 segments in inactivation, we decided to evaluate the role of the IIIS6 segment in Cav3.1 inactivation gating by mutating six residues to alanine (F1505A, F1506A, N1509A, F1511A, V1512A, F1519A). In addition we mutated M1510 to either isoleucine or alanine. These amino acids (except M1510) are identical in the IIIS6 segments of all voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. M1510, F1511 and V1512 correspond to the IFV-inactivation motif that was previously identified in segment IIIS6 of Cav2.1 (Hering et al. 1997, 1998; Sokolov et al. 2000). In order to compare the impact of the corresponding sequence stretches in Cav3.1 and Cav2.1 we analysed entry and recovery from inactivation of the corresponding Cav3.1 mutants at different potentials with the two-microelectrode voltage-clamp technique after expression in Xenopus oocytes. Here we demonstrate that residues in low and high threshold Ca2+ channels have a qualitatively similar impact on channel inactivation.

METHODS

Generation of Cav3.1 mutants

The residues of segment IIIS6, identical in CaV3.1 and high threshold Ca2+ channels, were replaced by alanine resulting in mutants F1505A, F1506A, N1509A, F1511A, V1512A and F1519A. Additionally, residue M1510 was replaced by alanine and isoleucine (M1510A; M1510I) and two double-point mutants were created: MF1510/1511AA and FV1511/1512AA.

The Cav3.1 mutants were constructed by introducing point mutations into the corresponding rat α1 subunit cDNA (accession number AF027984, Perez-Reyes et al. 1998) by the ‘gene SOEing’ technique (Horton et al. 1989). All constructs were inserted into the transcription plasmid pGEM-HEA and verified by sequence analysis (Chuang et al. 1998).

Electrophysiology

All animal experiments were approved by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Culture. Preparation of stage V-VI oocytes from Xenopus laevis, synthesis of capped run-off cRNA transcripts from linearized cDNA templates, and injection of cRNA were performed as previously described in detail by Grabner et al. (1996). Stage V and VI oocytes were harvested from female Xenopus laevis frogs under anaesthesia with 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (Sigma, 1 mg ml−1 in a water bath for 20 min). After oocyte removal, the abdominal incision was re-sutured and the frog was allowed to recover for 3–5 h in 1000 ml of water. Following the final oocyte harvest, the frogs were humanely killed. Follicle membranes from isolated oocytes were enzymatically digested with 2 mg ml−1 collagenase (Type 1A, Sigma).

Barium currents (IBa) were studied 2–14 days after microinjection of wild-type Cav3.1 and IIIS6-mutants cRNAs using the two-microelectrode voltage-clamp technique. The bath solution contained (mm): 40 Ba(OH)2, 50 mm NaOH, 5 Hepes, 2 CsOH, adjusted to pH 7.4 with methanesulfonic acid as previously described (Berjukow et al. 2000). Voltage-recording and current-injecting microelectrodes were filled with 2.8 m CsCl, 0.2 m CsOH, 10 mm EGTA and 10 mm Hepes (pH 7.4), and had resistances of 0.3–2 MΩ. If not otherwise stated, the holding potential was set to −80 mV.

The voltage of half-maximal inactivation (V0.5,inact) under quasi-steady-state conditions was measured using a multi-step protocol: a control test pulse (30 ms to the peak potential of the I–V curve) was followed by a 1 s step to −100 mV, a 3 s conditioning step, a 1 ms step to −100 mV and a subsequent test pulse to the peak potential of the I–V curve. Inactivation during the 3 s conditioning pulse was calculated as:

The pulse sequence was applied every 1 min from a holding potential of −100 mV and the estimated inactivation curves fitted to a Boltzmann equation:

where V is the membrane potential, V0.5,inact is the midpoint voltage of the inactivation curve, k is a slope factor, and Iss represents the fraction of non-inactivated current (Iss was close to zero).

The voltage of half-maximal activation (V0.5,act) was estimated from gpeak/gpeak,max = 0.5, where gpeak = Ipeak/(V - Erev), gpeak,max is the maximum value of gpeak measured at the descending part of the I–V curve and Erev is the reversal potential.

Recovery from inactivation was studied using a conventional double pulse protocol: after depolarising the channels from a holding potential of −100 mV for 1 s to the peak current potential of the I–V curve, 30 ms test pulses were applied at various time intervals to the same voltage. Peak IBa values were normalised to the peak current measured during the prepulse and the time course of IBa recovery from inactivation was fitted to a biexponential function:

The onset of inactivation at −50 and −40 mV was studied as the effect of variable prepulse durations (from −80 mV to −50 and −40 mV) on the peak current at −20 mV. A 1 ms gap at −80 mV was introduced between the pre and test pulses. Subsequently the time courses of channel inactivation were fitted to the monoexponential function:

At −30, −20 and −10 mV the time course of IBa inactivation was also fitted to a monoexponential function.

The pCLAMP software package version 8.0 (Axon Instruments, Inc.) was used for data acquisition and preliminary analysis. Microcal Origin 5.0 was employed for analysis and curve fitting. Data are given as means ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was calculated according to Student's unpaired t test (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Amino acids in segment IIIS6 of CaV3.1 affect the time constant of channel inactivation

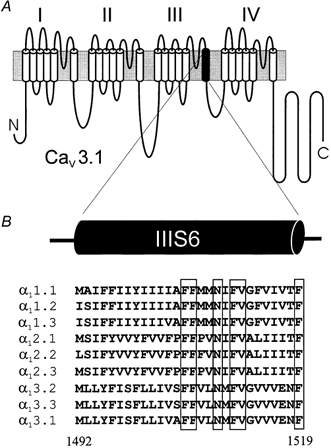

Channels of the CaV3 family display the fastest current inactivation kinetics among all voltage-gated calcium channels (Perez-Reyes et al. 1998, 1999). To elucidate the role of IIIS6 amino acids in inactivation of Cav3.1 we mutated those residues that are identical in all voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to alanine (Fig. 1). Some of these residues have previously been shown to modulate the inactivation properties of Cav2.1 (Hering et al. 1997; Kraus et al. 1998; Sokolov et al. 1999). Six out of the seven mutations (F1505A, F1506A, F1511A, V1512A, FV1511/1512AA and F1519A, but not N1509A) resulted in functional channels when the cRNAs were injected into Xenopus oocytes. In a previous study on Cav2.1 and Cav2.1/1.1 chimeric channel constructs, alanine substitutions of the adjacent I1612 in the Cav2.1 sequence (or Cav1.1, see Fig. 1) significantly slowed current inactivation (Hering et al. 1997). We have, therefore, mutated the corresponding M1510 in Cav3.1 to either alanine or isoleucine (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Segment IIIS6 of voltage-gated Ca2+ channel α1 subunits.

A, putative transmembrane topology of a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel α1 subunit. Each of the four domains consists of six transmembrane segments (segment IIIS6 is shown in black). B, sequence alignment of IIIS6 segments of various voltage-gated Ca2+ channel subtypes. Conserved amino acids are framed. The numbers are given for Cav3.1 sequence according to Perez-Reyes et al. (1998); accession number AF027984.

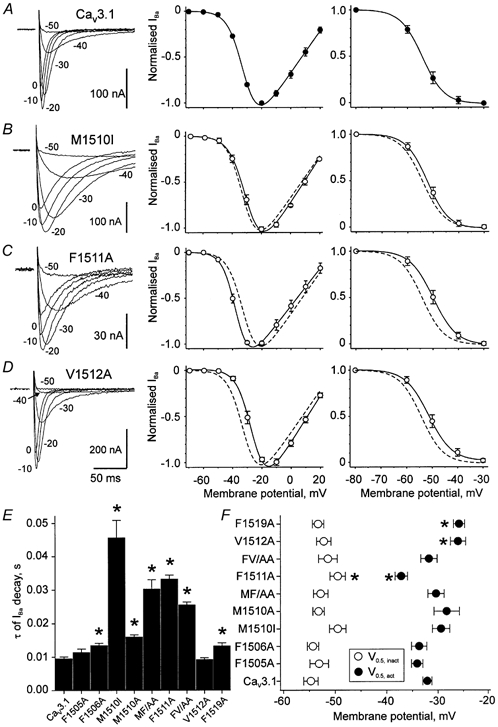

The inactivation properties of IBa through the mutant channels were investigated using the two-microelectrode voltage clamp (see Methods). Figure 2 illustrates the effects of IIIS6 mutations on the Cav3.1 kinetics. Representative families of IBa are shown on the left panels (A–D). The most prominent slowing in IBa inactivation was observed in mutants M1510I and F1511A; almost no change in current inactivation was observed for V1512A. The time constants of IBa decay of all mutants at −20 mV are summarised in Fig. 2E.

Figure 2. Voltage dependence of IBa through wild-type Cav3.1 and mutant channels.

A–D, left panels, families of the representative IBa through wild-type Cav3.1 (A) and selected Cav3.1 mutant channels (B–D). IBa were evoked by depolarising pulses from a holding potential of −80 mV to the indicated test potentials. Middle panels, normalised current-voltage relationships of the peak IBa through wild-type (A, •) and the mutant channels (B–D, ○). Right panels, voltage dependence of IBa steady-state inactivation of wild-type (A) and mutant channels (B–D). Data points were fitted to a Boltzmann function (see Methods). Dashed lines in B–D illustrate the position of the fitted activation and inactivation curves of wild-type Cav3.1. E, mean time constants of channel inactivation at −20 mV. F, the mean values of the corresponding half-maximal activation and inactivation potentials (V0.5,act and V0.5,inact). *P < 0.05 vs. wild-type.

The voltages of half-maximal inactivation ranged between −54.7 ± 1.4 mV in wild-type and −49.5 ± 1.5 mV in mutant F1511A (Fig. 2A and C, right panels). Thus, only F1511A displayed a statistically significant shift of the steady-state inactivation curve to more depolarised voltages (P < 0.05). The voltage dependence of channel activation was significantly shifted in mutants F1511A (-37.2 ± 1.2 mV, Fig. 2C, middle panel), V1512A (-26.1 ± 1.5 mV, Fig. 2D) and F1519A (-25.9 ± 1.1 mV compared to wild-type 32.1 ± 0.9 mV, Fig. 2A). The V0.5,act and V0.5,inact values are summarised in Fig. 2F.

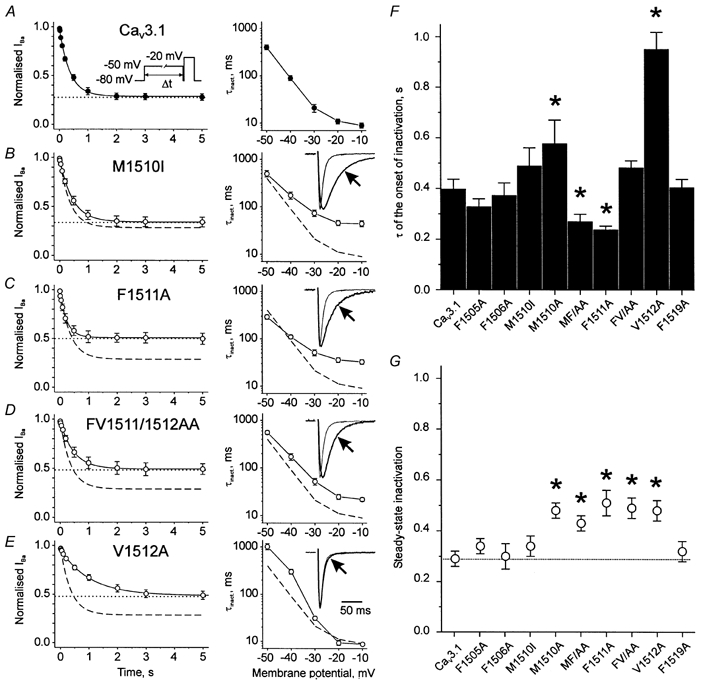

The IIIS6 mutations produced different effects on the voltage dependence of inactivation. The time courses of channel inactivation at −50 mV and the corresponding voltage dependencies of inactivation are illustrated on the left and right panels of Fig. 3A–E. Prominent slowing of the IBa decay at −20 mV was observed for mutants M1510I (4.8-fold) and F1511A (3.5-fold, see Fig. 2). Mutants V1512A did not significantly affect the inactivation time course at −20 mV (Fig. 2D) but significantly slowed inactivation at −50 mV (2.4-fold, Fig. 3E and F). The different levels of steady-state inactivation at −50 mV produced by the various mutations are illustrated in Fig. 3G.

Figure 3. Mutations of amino acids in segment IIIS6 alter kinetics of channel inactivation.

A–E, left panels, mean time courses of channel inactivation at −50 mV. Smooth curves depict monoexponential functions fitted to the mean inactivation time courses. The steady-state levels of inactivation are shown as dotted lines. Dashed lines in B–E illustrate the monoexponential function fitted to the mean time course of inactivation in the wild-type Cav3.1. Inset in A illustrates the voltage protocol. A–E, right panels, voltage dependencies of the inactivation time constants. The dashed lines in B–E correspond to wild-type. Insets in right panels, scaled superimposed families of IBa (at −20 mV) through wild-type and selected Cav3.1 mutant channels. F, mean time constants of channel inactivation at −50 mV. G, steady-state levels of inactivation at −50 mV. The dotted line corresponds to the steady-state inactivation of wild-type. *P < 0.05 vs. wild-type.

In analogy to the Cav2.1 double mutant IF1612/1613AA (see Sokolov et al. 2000) we created a corresponding Cav3.1 construct, MF1510/1511AA. At −20 mV MF1510/ 1511AA inactivated significantly more slowly than wild-type (3.2-fold, Fig. 2E). The double mutation FV1511/1512AA also caused a significantly slower time course of inactivation at −20 mV (2.7-fold slowing). At −50 mV the inactivation of MF1510/1511AA was accelerated, whereas inactivation of FV1511/1512AA was not different from wild-type (Fig. 3F). In other words, dominant effects of a single point mutation on the inactivation kinetics of a double mutant occurred only in a certain voltage range (Fig. 3A–E, right panels).

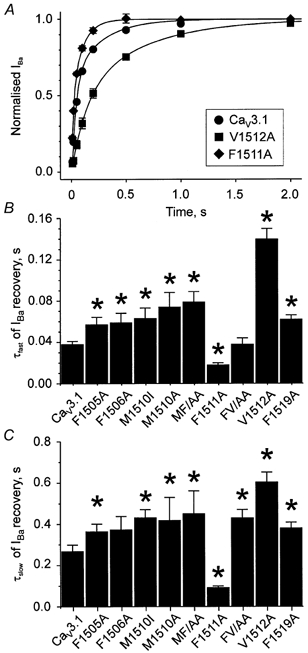

IIIS6 mutations modulate the stability of channel inactivation

In order to elucidate the impact of the IIIS6 mutations on the stability of the inactivated channel conformations, we analysed the IBa recovery at −80 mV. The time course of channel recovery from inactivation was described by a double exponential function (Fig. 4A). Recovery of wild-type channels occurred with a fast time constant (τfast) of 0.038 ± 0.003 s and a slow time constant (τslow) of 0.27 ± 0.03 s. The most pronounced acceleration of repriming was observed for mutant F1511A (τfast = 0.018 ± 0.002 s, τslow = 0.097 ± 0.005 s). As evident from the decelerated recovery, mutation V1512A stabilised the inactivated channel states (τfast = 0.140 ± 0.011 s, τslow = 0.60 ± 0.05 s, Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Mutations in the segment IIIS6 of Cav3.1 affect recovery from inactivation.

A, mean time courses of IBa recovery from inactivation at −80 mV after a 1 s conditioning prepulse to −20 mV in wild-type (•), mutant F1511A (♦) and V1512A (▪) channels. B and C, mean time constants of IBa recovery (τfast and τslow) at −80 mV. *P < 0.05 vs. wild-type.

The double mutant FV1511/1512AA recovered from inactivation with comparable kinetics to V1512A (see Fig. 4B and C).

DISCUSSION

Structural determinants of high threshold Ca2+ channel inactivation are localised in transmembrane S4, S5 and S6 segments, pore loops, intracellular loops (particularly in intracellular domain linkers), and the carboxyl terminus (Zhang et al. 1994; Herlitze et al. 1997; Soldatov et al. 1998; Berjukow et al. 1999; Bourinet et al. 1999; Spaetgens & Zamponi, 1999; Sokolov et al. 2000; Stotz et al. 2000; see Hering et al. 1998, 2000).

The structural determinants of low threshold Ca2+ channels are much less characterised. Staes et al. (2001) identified a negatively charged region of 23 amino acids at the carboxy terminus of the Cav3.1 as a crucial determinant of fast inactivation and suggested a model where this sequence stretch serves as an intracellular acceptor for a yet to be identified ball segment hypothetically located at an intracellular channel part.

In the present study we focused on the role of segment IIIS6 in Cav3.1 inactivation. By substituting six amino acids that are identical in the IIIS6 segments of all Ca2+ channel types and an additional M1510, we identified a hot spot of inactivation determinants that has previously been shown to play an essential role in inactivation of the high threshold Cav2.1 (Fig. 1).

Hot spot of inactivation determinants in segment IIIS6

Alanine substitutions of IIIS6 residues revealed that three consecutive amino acids play an important role in Cav3.1 inactivation gating. At −20 mV significant slowing of the IBa decay was observed for four single amino acid substitutions (M1510I > F1511A > M1510A > F1519A). M1510I and F1511A induced the most pronounced slowing at −20 mV, suggesting that these residues play a critical role in Cav3.1 inactivation. At −50 mV the most prominent slowing of channel inactivation was caused by mutation V1512A, while F1511A induced an acceleration (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Recovery of wild-type channels from inactivation was better fitted by two than by one exponential(s) suggesting the existence of at least two (fast and slow) inactivated channel conformations. Point mutations in segment IIIS6 affected both time constants. Recovery from the fast inactivated state at −80 mV was most significantly slowed by V1512A and accelerated by F1511A (Fig. 4). In general, a slowing or acceleration of the fast component in recovery was accompanied by a slowing or acceleration of the slow component (Fig. 4B and C). These data suggest that amino acid substitutions in segment IIIS6 affect the stability of the fast inactivated state as well as the recovery from a second (presumably slow) inactivated channel conformation. Further studies will characterise the mutational effects on the two inactivated states in more detail.

In previous studies on Cav2.1 and chimeric CaV2.1/1.1 channel constructs (Hering et al. 1997; Sokolov et al. 2000) we observed a pronounced slowing of channel inactivation if I1612, F1613 and V1614 in segment IIIS6 were substituted by alanine (IFV-motif, Hering et al. 1998). I1612, F1613 and V1614 in Cav2.1 correspond to M1510, F1511 and V1512 in CaV3.1 (Fig. 1B). In order to analyse if a common structural motif in segment IIIS6 determines inactivation in high and low threshold Ca2+ channels, we have substituted for M1510 in Cav3.1 the CaV2.1 isoleucine and additionally alanine. Both mutations affected the time course of Cav3.1 inactivation (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). These data suggest that, in analogy to the IFV-motif in Cav2.1, M1510, F1511 and V1512 form a ‘hot spot’ of inactivation determinants in segment IIIS6 of CaV3.1. Interestingly, in sodium channels F1468A (corresponding to F1511 in IIIS6 of CaV3.1) also modulates inactivation (Yarov-Yarovoy et al. 2001) suggesting common inactivation determinants in sodium and Ca2+ channels.

Implications for the mechanism of Cav3.1 inactivation

The double mutation MF1510/1511AA slowed Cav3.1 inactivation like the corresponding IF1612/1613AA in Cav2.1 (Sokolov et al. 2000). Interestingly, mutations of neighbouring amino acids on segment IIIS6 (F1511, V1512) lead - at a given membrane voltage - to different and in some cases even opposite effects on the channel kinetics. At −20 mV mutant F1511A inactivated slower than wild-type while V1512A did not significantly change state transitions towards inactivation (Fig. 2C and D). Recovery was substantially slowed by V1512A and accelerated by F1511A (Fig. 4).

At −20 mV the kinetic phenotype of the single point mutant F1511A was dominant for FV1511/1512AA. At −50 mV inactivation occurred at an intermediate rate, suggesting an impact of both amino acid substitutions. Recovery of the double mutant FV1511/1512AA occurred with similar kinetics to wild-type while single point mutants either significantly accelerated or slowed channel repriming. Comparable observations were made for M1510A, F1511A and the corresponding double mutation MF1510/1511AA; at −20 mV, inactivation of MF1510/1511AA occurred with a similar time course to F1511A, while channel recovery at −80 mV was apparently determined by M1510A. Thus, our data suggest that point mutations in segment IIIS6 affect inactivation gating predominantly in a certain voltage range. Some of our mutations also affected channel activation. Thus, mutants F1511A and FV1511/1512AA activate apparently with slower kinetics than wild-type (Fig. 1, time to peak of FV1511/1512AA is 15.5 ± 0.7 ms and of F1511A is 16.0 ± 0.4 ms vs. 9.5 ± 0.3 ms in wild-type Cav3.1 at −20 mV, P < 0.05, see also changes in the voltage dependence of steady-state activation in Fig. 2F).

It is tempting to speculate that spontaneous mutations in S6 and adjacent segments played an important role in fine tuning of Ca2+ entry through different Ca2+ channel subtypes during evolution. The recent identification of point mutations in this region causing a number of channelopathies that are associated with disturbances in inactivation gating support this hypothesis (see Jen, 1999). Future studies of the impact of Ca2+ channel subtype-specific amino acids in other S6 segments including also residues that are specific for Cav3 (see Fig. 1) will help to understand the molecular basis of the different inactivation phenotypes.

In summary, we report for the first time a significant role of a S6 segment in Cav3.1 inactivation. We have identified a ‘hot spot’ of inactivation determinants (M1510, F1511, V1512) in segment IIIS6. Our data suggest common elements in the architecture of the inactivation machineries in high and low threshold Ca2+ channels. We hypothesize that these residues play a critical role in helix packing within this putative bundle crossing region of the corresponding α1 subunits (Doyle et al. 1998) thereby modulating the closure of the channel pore during depolarisation (Perozo et al. 1998; Yellen, 1999). Alternatively, structural changes in S6 segments may directly or indirectly affect a pore receptor for a gate formed by the carboxy terminus (Staes et al. 2001).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants of the Fonds zur Förderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (P12649-MED, P12828-MED to S.H.), a grant from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung and a grant of the Austrian National Bank (to S.H.).

References

- Berjukow S, Gapp F, Aczel S, Sinnegger MJ, Mitterdorfer J, Glossmann H, Hering S. Sequence differences between α1C and α1S Ca2+ channel subunits reveal structural determinants of a guarded and modulated benzothiazepine receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:6154–6160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berjukow S, Marksteiner R, Gapp F, Sinnegger MJ, Hering S. Molecular mechanism of calcium channel block by isradipine. Role of a drug induced inactivated channel conformation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:22114–22120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908836199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berjukow S, Marksteiner R, Sokolov S, Weiss RG, Margreiter E, Hering S. Amino acids in segment IVS6 and β-subunit interaction support distinct conformational changes during Cav2. 1 inactivation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:17076–17082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Soong TW, Sutton K, Slaymaker S, Mathews E, Monteil A, Zamponi GW, Nargeot J, Snutch TP. Splicing of α1A subunit gene generates phenotypic variants of P- and Q-type calcium channels. Nature Neuroscience. 1999;5:407–415. doi: 10.1038/8070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cens T, Restituito S, Galas S, Charnet P. Voltage and calcium use the same molecular determinants to inactivate calcium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:5483–5490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang RS, Jaffe H, Cribbs L, Perez-Reyes E, Swartz KJ. Inhibition of T-type voltage-gated calcium channels by a new scorpion toxin. Nature Neuroscience. 1998;1:668–674. doi: 10.1038/3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Cabral JM, Pfuetzner RA, Kou A, Gilbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel EA, Campbell KP, Harpold MM, Hofmann F, Mori Y, Perez-Reyes E, Schwartz A, Snutch TP, Tanabe T, Birnbaumer L, Tsien RW, Catterall WA. Nomenclature of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron. 2000;25:533–535. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner M, Wang Z, Hering S, Striessnig J, Glossmann H. Transfer of 1,4-dihydropyridine sensitivity from L-type to class A (BI) calcium channels. Neuron. 1996;16:207–218. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering S, Aczel S, Kraus RL, Berjukow S, Striessnig J, Timin EN. Molecular mechanism of use-dependent calcium channel block by phenylalkylamines: role of inactivation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:13323–13328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering S, Berjukow S, Aczel S, Timin EN. Ca2+ channel block and inactivation: common molecular determinants. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 1998;19:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering S, Berjukow S, Sokolov S, Marksteiner R, Weiss RG, Kraus R, Timin EN. Molecular determinants of inactivation in voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Journal of Physiology. 2000;528:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitze S, Hockerman GH, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of inactivation and G protein modulation in the intracellular loop connecting domains I and II of the calcium channel α1A subunit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1997;94:1512–1516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton RM, Hunt HD, Ho SN, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Engineering hybrid genes without the use of restriction enzymes: gene splicing by overlap extension. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jen J. Calcium channelopathies in the central nervous system. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1999;9:274–280. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus RL, Hering S, Grabner M, Ostler D, Striessnig J. Molecular mechanism of diltiazem interaction with L-type Ca2+ channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:27205–27212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Cribbs LL, Daud A, Lacerda AE, Barclay J, Williamson MP, Fox M, Rees M, Lee JH. Molecular characterization of a neuronal low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channel. Nature. 1998;391:896–900. doi: 10.1038/36110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Lee JH, Cribbs LL. Molecular characterization of two members of the T-type calcium channel family. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;868:131–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perozo E, Cortes DM, Cuello LG. Three-dimensional architecture and gating mechanism of a K+ channel studied by EPR spectroscopy. Nature Structural Biology. 1998;5:459–469. doi: 10.1038/nsb0698-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov S, Weiss RG, Kurka B, Gapp F, Hering S. Inactivation determinant in the I-II loop of the Ca2+ channel α1-subunit and β-subunit interaction affect sensitivity for the phenylalkylamine (-)-gallopamil. Journal of Physiology. 1999;519:315–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0315m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov S, Weiss RG, Timin EN, Hering S. Modulation of slow inactivation in class A Ca2+ channels by β-subunits. Journal of Physiology. 2000;527:445–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00445.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatov NM, Oz M, O'Brien KA, Abernethy DR, Morad M. Molecular determinants of L-type Ca2+ channel inactivation. Segment exchange analysis of the carboxyl-terminal cytoplasmic motif encoded by exons 40–42 of the human α1C subunit gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:957–963. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaetgens RL, Zamponi GW. Multiple structural domains contribute to voltage-dependent inactivation of rat brain α1E calcium channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:22428–22436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staes M, Talavera K, Klugbauer N, Prenen J, Lacinova L, Droogmans G, Hofmann F, Nilius B. The amino side of the C-terminus determines fast inactivation of the T-type calcium channel α1G. Journal of Physiology. 2001;530:35–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0035m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens GJ, Page KM, Bogdanov Y, Dolphin AC. The α1B Ca2+ channel amino terminus contributes determinants for β-subunit-mediated voltage-dependent inactivation properties. Journal of Physiology. 2000;525:377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotz SC, Hamid J, Spaetgens RL, Jarvis SE, Zamponi GW. Fast inactivation of voltage-dependent calcium channels. A hinged-lid mechanism? Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:24575–24582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarov-Yarovoy V, Brown J, Sharp EM, Clare JJ, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent gating and binding of pore-blocking drugs in transmembrane segment IIIS6 of the Na+ channel α-subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:20–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellen G. The bacterial K+ channel structure and its implications for neuronal channels. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1999;9:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JF, Ellinor PT, Aldrich RW, Tsien RW. Molecular determinants of voltage-dependent inactivation in calcium channels. Nature. 1994;372:97–100. doi: 10.1038/372097a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]