Abstract

The aim of the study was to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the depressant effect of the group I/II metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) agonist 1S,3R-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (1S,3R-ACPD) on parallel fibre (PF) to Purkinje cell (PC) synaptic transmission. Experiments were performed in rat cerebellar slices using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique and fluorometric measurements of presynaptic calcium variation

Analysis of short-term plasticity, fluctuation of EPSC amplitude and responses of PCs to exogenous glutamate showed that depression caused by 1S,3R-ACPD is presynaptic.

The effects of 1S,3R-ACPD were blocked and reproduced by group I mGluR antagonists and agonists, respectively.

These effects remained unchanged in mGluR5 knock-out mice and disappeared in mGluR1 knock-out mice.

1S,3R-ACPD increased calcium concentration in PFs. This effect was abolished by AMPA/kainate (but not NMDA) receptor antagonists and mimicked by focally applied agonists of these receptors. Thus, it is not directly due to mGluRs but to presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors indirectly activated by 1S,3R-ACPD.

Frequencies of spontaneous and evoked unitary EPSCs recorded in PCs were respectively increased and decreased by mGluR1 agonists. Similar results were obtained when mGluR1s were activated by tetanic stimulation of PFs.

Injecting 30 mm BAPTA into PCs blocked the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD on unitary EPSCs.

In conclusion, 1S,3R-ACPD reduces evoked release of glutamate from PFs. This effect is triggered by postsynaptic mGluR1s and thus implies that a retrograde messenger, probably glutamate, opens presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors and consequently increases spontaneous release of glutamate from PF terminals and decreases evoked synaptic transmission.

Group I mGluRs (mGluR1, mGluR5) are positively coupled to phospholipase C (PLC) and lead to the production of diacylglycerol (DAG), as well as to the activation of the inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3)-calcium signal transduction pathway, whereas both group II (mGluR2, mGluR3) and group III mGluRs (mGluR4, mGluR6, mGluR7, mGluR8) are negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase (Pin & Duvoisin, 1995). The acute depression of excitatory synaptic transmission by mGluR activation is currently attributed to the activation of presynaptic group II or III mGluRs (see references in Cochilla & Alford, 1998). However, at synapses between parallel fibres (PFs) and Purkinje cells (PCs), application of the groups I/II mGluR agonist trans-aminocyclopentyl-dicarboxylate (trans-ACPD) reversibly depresses synaptic transmission (Crepel et al. 1991; Glaum et al. 1992; Staub et al. 1992), while there are no presynaptic group II mGluRs. Indeed, at these synapses, the only trans-ACPD-sensitive mGluRs are mGluR1s located on PCs (Martin et al. 1992; Baude et al. 1993; Grandes et al. 1994), whereas presynaptic mGluR4s are insensitive to trans-ACPD (see references in Pin & Duvoisin, 1995). Moreover, the depressant effect of 1S,3R-aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (1S,3R-ACPD; the active isomer of trans-ACPD) is lost in mGluR1 knock-out mice (Conquet et al. 1994), confirming that postsynaptic mGluR1s are involved in the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD on PF to PC synaptic transmission. Thus, the mechanism underlying the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD at this synapse remains unknown.

The aim of the present study is to address this question using an in vitro acute slice preparation. The results show that activation of postsynaptic mGluR1s causes a presynaptic decrease of PF to PC synaptic transmission by retrograde signalling through release of a messenger from PCs, probably glutamate.

METHODS

Experiments complied with guidelines of the French Animal Care Committee. Male rats (Sprague-Dawley) aged 14–21 days were stunned before decapitation. The cerebellum was then dissected and sagittal slices, 200 μm thick, were cut with a vibroslicer. Slices were incubated at room temperature in saline solution bubbled with 95 % O2-5 % CO2 for at least 1 h. The recording chamber was perfused at a rate of 2 ml min−1 with oxygenated saline solution containing (mm): NaCl, 124; KCl, 3; NaHCO3, 24; KH2PO4, 1.15; MgSO4, 1.15; CaCl2, 2; glucose, 10; and the GABAA antagonist bicuculline methiodide (10 μm, Sigma Aldrich, St Quentin Fallavier, France); osmolarity 320 mosmol l−1, final pH 7.35 at 25 °C. PCs were directly visualized with Nomarski optics through the × 40 water-immersion objective of an upright microscope (Zeiss). Experiments on strontium-induced asynchronous release of glutamate vesicles from stimulated synapses were performed by simply substituting strontium for calcium in the bathing medium.

1S,3R-Aminocyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (1S,3R-ACPD), (S)3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG), 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-APV), l-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (l-AP4), (RS)-11-aminoindan-1,5-dicarboxylic acid (AIDA), (RS)-α-methylserine-O-phosphate monophenyl ester (MSOPPE), (RS)-α-methylserine-O-phosphate (MSOP), NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate (l-NMMA), 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) and tetrodotoxin citrate (TTX) were purchased from Tocris (Illkirch, France). NG-Nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) was purchase from Sigma (Sigma Aldrich, St Quentin Fallavier, France). SR141716-A was provided by Sanofi-Recherche (Montpellier, France). The GABAB antagonists CGP55845-A and CGP35348 were gifts from Nathalie Leresche (Laboratoire de Neurobiologie Cellulaire et Neurogenetique Moleculaire, CNRS UMR C7624, Paris).

Electrophysiology

Recordings using the patch-clamp technique were performed in the soma of PCs, using an Axopatch-200 amplifier (Axon Instruments). Extracellular stimulation was performed using monopolar saline-filled electrodes. Patch pipettes (2–4 MΩ) were filled with a solution containing (mm): NaCl, 8; potassium gluconate, 70; KCl, 70; Hepes, 10; ATP-Mg, 2; EGTA, 0.75; pH 7.35 with KOH; 300 mosmol l−1. For high BAPTA concentration, the internal solution contained (mm): KCl, 110; BAPTA, 30; Hepes, 10; CaCl2, 3, ATP-Mg, 2; pH 7.35 with KOH; 300 mosmol l−1. Components of internal solutions were purchased from Sigma.

In the cells retained for analysis, access resistance (usually 5–10 MΩ) was partially compensated (50–70 %), according to the procedure described by Llano et al. (1991b). Cells were held at a membrane potential of −70 mV. PFs were stimulated at 0.16 Hz and PF EPSCs were preceded by 10 mV hyperpolarizing voltage steps that allowed monitoring of the passive electrical properties of the recorded cell throughout the experiment (Llano et al. 1991b).

The interstimulus interval used to induce paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) was 30 ms. PPF was estimated by calculating the ratio of the amplitude of the second PF EPSC over the first one. As in previous papers (Levenes et al. 1998), variation of synaptic responses was examined using the coefficient of variation (CV) method (references in Kullmann, 1994). CV is given by: CV2 = (s/M)2, where s is the standard deviation of the amplitude distribution of EPSCs corrected for the background noise, and M is the mean amplitude of EPSCs during the same epoch. The CV was calculated on sets of 50 EPSCs when the responses were stable over this epoch.

Ionophoresis of glutamate or 1S,3R-ACPD was performed through a small patch-like pipette (diameter of approximately 1 μm). Diffusion of glutamate or 1S,3R-ACPD out of the pipette was prevented by maintaining a constant small positive current. The amplitude of the negative current used to deliver the drugs and the position of the pipette in the dendritic field of the recorded PC were adjusted to evoke a clear and stable current with kinetics matching time application. Control periods lasted at least 10 min to ensure the stability of the response.

For analysis, the synaptic currents in PCs were usually filtered at 5 kHz and digitized on-line at 20 kHz. PF EPSCs were analysed with the Acquis1 computer program (Biologic). For analysis of unitary synaptic events, currents were further filtered at 2 kHz and analysed off-line with Detectivent, Labview-based software developed by N. Ankri (Ankri et al. 1994). Detection parameters were adjusted so that most visible synaptic events were detected, and, on the contrary, no detection occurred in current traces recorded from the same cells in the presence of 20 μm CNQX added at the end of the recording. For each cell, analysis was performed on a few hundred of such selected spontaneous or evoked synaptic events. In strontium experiments, events detected between 100 and 500 ms following PF stimulation were considered as potentially evoked and named ‘after-stimulus’ EPSCs. Averaging 100 residual PF-mediated responses for each cell showed that there was no longer an occurrence of after-stimulus events after 600 ms following the stimulation, therefore, events detected in a 400 ms time window starting 1 s after the stimulus were considered as ‘spontaneous’ EPSCs. The number of ‘evoked’ EPSCs encountered during the 100–500 ms period following stimulation was the difference between ‘after-stimulus’ EPSCs and ‘spontaneous’ EPSCs.

Calcium-sensitive fluorometric measurements

PFs in coronal slices were loaded by local application of the fluorescent calcium indicators fluo-3 AM or fluo-4-FF AM (100 μm, Molecular Probes), following the procedure described by Regehr & Tank (1991). A suction pipette was placed near the delivery site of the dye to constrain its diffusion in a small area of the molecular layer. The fluorescence was recorded in a 20 μm × 50 μm window placed in the molecular layer approximately 500–800 μm away from the loading site and 100 μm above the PC layer. In order to rinse unloaded dye and to allow diffusion of the dye along PFs, recordings started 30–45 min after 30 min loading of PFs. The epifluorescence excitation was at 485 ± 22 nm and the emitted light was collected by a photomultiplier through a barrier filter at 530 ± 30 nm. Fluorescence data corrected for background fluorescence were expressed as ΔF/F multiplied by 100 to give a percentage, where F is the baseline fluorescence intensity, and ΔF is the change induced either by stimulation of PFs or by drug application. PF stimulations were used to ensure that the calcium signal was actually recordable in the chosen window and to verify the efficacy of TTX when used. To record ΔF/F in granule cells the slices were incubated for 30 min in a standard external solution containing the dye fluo-3 AM (100 μm). The recording window was then placed in a zone of the granule cell layer where no cell types other than granule cells were visible.

RESULTS

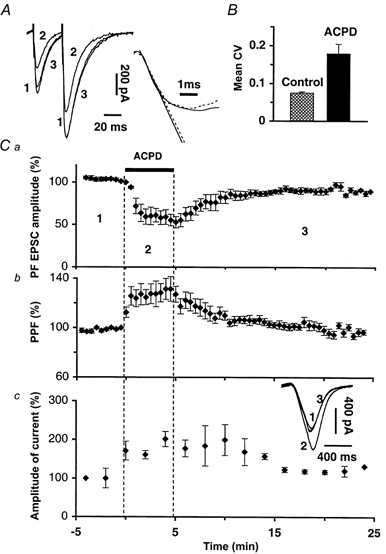

Results are expressed as means ± s.e.m. unless otherwise mentioned. In all cells tested (n = 13), bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD induced a large and reversible reduction in the amplitude of PF EPSCs to 62.1 ± 9.1 % of control (P < 0.01; ANOVA; Fig. 1A and Ca). 1S,3R-ACPD also induced in PCs a transient inward current that could be large (i.e. more than 800 pA in 4 out of 13 cells tested, not illustrated) and partially desensitized before wash-out of 1S,3R-ACPD. However, as already observed (Glaum et al. 1992), there was no difference in the reduction of amplitude of PF EPSCs between the cells where the inward current was large and those where it was modest (i.e. ≤ 100 pA; 63.4 ± 11 %, n = 9, and 61.4 ± 8.1 %, n = 4, of control baseline, respectively). This indicates that the amplitude of the depression of PF EPSCs is independent of the amplitude of the inward current. The depression of PF EPSCs lasted longer than the inward current, which disappeared immediately after wash-out of 1S,3R-ACPD (n = 13). Taking advantage of this, all analyses from this paper were performed after the cells recovered their initial holding current ( ± 10 %). Finally, 1S,3R-ACPD did not change the slope of the rising phase of PF EPSCs (n = 13, Student's paired t test; Fig. 1A), indicating that their decrease in amplitude was not due to alteration of membrane resistance in the dendrites.

Figure 1. Effects of 1S,3R-ACPD PF EPSCs.

A, left trace, superimposed sweeps of PF EPSCs elicited by 2 successive PF stimulations with an interstimulus interval of 30 ms in control (1), in 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (2) and after washout (3); right trace, scaling of sweep 2 to sweep 1 shows that the slopes of their rising phase are not changed by 1S,3R-ACPD. Note that 1, 2 and 3 correspond to numbers indicated in C. B, bar graph of mean CV (+ s.e.m., n = 16) calculated with CV values obtained during control and in the presence of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD. C, plot of the mean ( ± s.e.m.) normalized amplitude (a) or paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) (b) of PF EPSCs recorded from 9 PCs. c, plot of the mean ( ± s.e.m.) amplitude of the current induced in these 9 PCs by 400 ms glutamate pulses. Inset shows an example of these currents recorded from one PC. Y-axis labels are the percentage of the mean amplitude in control (calculated over the 5 min preceding ACPD application).

Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) is a short-term enhancement of synaptic transmission used to detect changes in the probability of release of neurotransmitters (Zucker, 1973; Atluri & Regehr, 1996). In all tested cells, PPF of PF EPSCs (Fig. 1A and Cb) increased during bath application of 1S,3R-ACPD (220.2 ± 18.2 % of control, n = 10). In keeping with these results suggesting a presynaptic site of action of 1S,3R-ACPD, the coefficient of variation (CV, see Methods) of the amplitude of PF EPSCs also increased during the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD to 194.7 ± 13.4 % of control (Fig. 1B, n = 16, Student's t test; P < 0.01).

The increased PPF and CV of PF EPSCs indicate a presynaptic site of action of 1S,3R-ACPD on PF EPSCs but do not rule out an additional postsynaptic effect. We thus tested the effect of bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD on the amplitude of inward currents induced in PCs by ionophoretic application of glutamate in their dendritic field (Fig. 1Cc, n = 12). In these experiments, PF EPSCs were monitored simultaneously to control the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD. 1S,3R-ACPD potentiated responses of PCs to glutamate to 182.3 ± 25.5 % of control, while PF-mediated EPCSs were actually depressed. Consistent with a previous report (Glaum et al. 1992), this potentiation suggests that the postsynaptic effect of 1S,3R-ACPD consists of a transient increase in amplitude of AMPA currents and reinforces the view that the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on PF EPSCs is presynaptic.

1S,3R-ACPD is an agonist of groups I and II mGluRs (see Pin et al. 1999), but in contrast to cultured granule cells (Chavis et al. 1995), in situ granule cells do not express group I or II mGluRs (Martin et al. 1992; Baude et al. 1993; Grandes et al. 1994), except for some mGluR1s which were found in some granule cells scattered throughout the cerebellum (according to Baude et al. 1993) or mainly localized in lobule 9 (according to Grandes et al. 1994). Group III mGluR4s are expressed at PF terminals (Ohishi et al. 1995; Kinoshita et al. 1996), but they are insensitive to 1S,3R-ACPD (see Conquet et al. 1994). Thus, the presynaptic locus of the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD at PF-PC synapses was rather unexpected and it was important to determine the subtype(s) of mGluRs implicated in this effect.

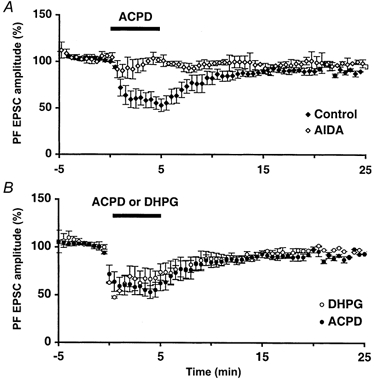

The 1S,3R-ACPD-induced reduction of PF EPSCs was blocked by the selective group I mGluR antagonist, AIDA. Indeed, in control experiments, 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD induced a decrease of PF EPSCs by 62.1 ± 9.1 % (see first section of Results) while the same application done in the presence of 300 μm AIDA led to a decrease of PF EPSCs of only 9.8 ± 3.0 % (n = 5, Fig. 2A). The effects of the specific group I mGluR agonist S-DHPG (Schoepp et al. 1994; Pin & Duvoisin, 1995) were similar to those of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD. Indeed, 5 min bath application of 50 μm S-DHPG decreased the amplitude of PF EPSCs to 55.8 ± 9.5 % of control (n = 7, Fig. 2B) and increased the PPF and CV of these responses.

Figure 2. The depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD is due to group I mGluRs.

Plot of mean ( ± s.e.m.) PF EPSC amplitude over time. A, effect 1S,3R-ACPD in the presence of the group I antagonist AIDA (300 μm, n = 5 cells), plotted on the same axis as the effect of 1S,3R-ACPD alone. B, effect of 1S,3R-ACPD plotted on the same axis as the effect of the specific group I agonist S-DHPG (50 μm, n = 7 cells).

Thus, the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD results from the activation of group I mGluRs. To discriminate between mGluR1 and mGluR5, we used two different transgenic mice after having ascertained that the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD described so far were the same in control mice as in rats (n = 4 each).

The effects of 1S,3R-ACPD in mice lacking mGluR5 (developed and provided by F. Conquet) were similar to that obtained in control mice, indicating that mGluR5 does not participate in the 1S,3R-ACPD-induced reduction of PF EPSCs (n = 4, not shown). As reported previously (see Conquet et al. 1994), we found that application of 50–100 μm 1S,3R-ACPD had no effect on PF EPSCs and on PC responses to glutamate pulses in mice lacking mGluR1 (n = 6, not shown).

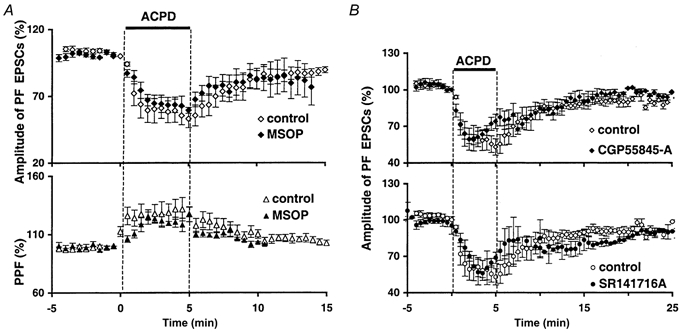

Thus, the presynaptic depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD described in this study originates specifically from mGluR1 activation. However, it is unlikely to result from mGluR1s expressed on PFs themselves because, as discussed above, granule cells generally do not express mGluR1s. It could rather be due to mGluR1s expressed on neighbouring cells. Because mGluR1 activation leads to the release of calcium from internal stores (Takechi et al. 1998), we first considered the possibility that some calcium-dependent diffusible messenger, able to depress PF to PC synaptic transmission, could be released by any cell bearing mGluR1s when depolarized by 1S,3R-ACPD. GABAergic interneurones could release GABA when depolarized by 1S,3R-ACPD. GABAA receptors were blocked by bicuculline, but GABAB receptors, located on PF terminals, could reduce glutamate release and could subsequently decrease PF EPSCs (Dittman & Regehr, 1996). However, bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD in the presence of the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 55845-A (300 nm) still caused a reduction of PF EPSCs not different from control experiments (to 67.6 ± 7.2 and 62.1 ± 9.1 % of control, respectively, n = 5, Fig. 6B). This reduction of PF EPSC amplitude was, however, of slightly shorter duration in the presence of the GABAB antagonist than in control experiments. Similar effects were obtained with another GABAB antagonist, CGP 35348 (500 μm, n = 3, not shown). Thus, activation of neighbouring GABAergic interneurones by 1S,3R-ACPD does not cause the reduction of PF-mediated EPSCs but might prolong its depressant effect on PF to PC synaptic transmission through the activation of GABAB receptors expressed by PFs.

Figure 6. Effects of 1S,3R-ACPD in the presence of mGluR4 or GABAB or CB1 receptor antagonists.

A, plot of normalized amplitudes (mean ± s.e.m., upper graph) and PPF (mean ± s.e.m., lower graph) of PF EPSCs against time before, during and after bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD, in control (⋄ or ▴) or in the presence of 200 μm of the group III mGluR antagonist MSOP (♦ or ▴, n = 5). B, plot of normalized amplitudes (mean ± s.e.m.) of PF EPSCs against time before, during and after bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (filled horizontal bar). Top panel, control conditions (⋄) superimposed on experiments in the presence of 300 nm GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 55845-A (♦). Lower panel, control conditions (○) superimposed on experiments in the presence of 1 μm CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716-A (•).

Among other possible candidates were cannabinoids (through presynaptic CB1 receptors, see Levenes et al. 1998), adenosine (through presynaptic A1 receptors, see Dittman & Regehr, 1996) and nitric oxide (NO, through its presynaptic acute depressant effect, see Blond et al. 1997). However, the 1S,3R-ACPD-induced depression of PF EPSCs was not blocked by the CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716-A (2 μm bath applied 15–20 min prior to 1S,3R-ACPD, n = 5, Fig. 6B, see Levenes et al. 1998) or by an A1 receptor antagonist (100 nm DPCPX, n = 4, not shown), or two NO synthase inhibitors: l-NMMA (60 μm, n = 4) and l-NAME (1 mm, n = 5, not shown). With the CB1 antagonist, there was a slight change in the kinetics of depression by 1S,3R-ACPD (Fig. 6B), suggesting that, as for GABAB receptors, endogenous cannabinoids could participate in the overall effect without causing the major part of the depression.

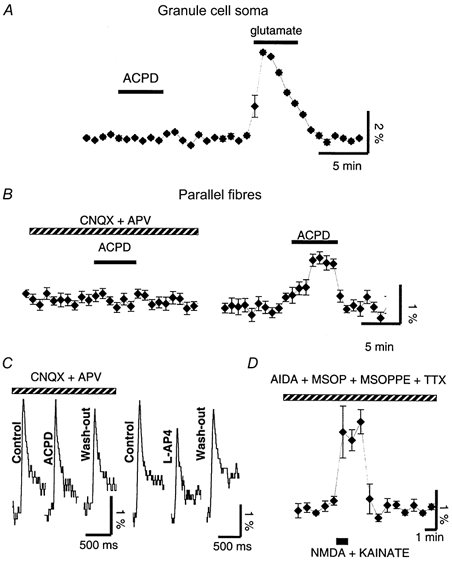

Experiments presented so far did not provide evidence for a participation of neighbouring cells, bearing mGluR1s, in the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD. However, other transmitters or mechanisms were also possible. In particular, the possibility that some mGluR1-like 1S,3R-ACPD-sensitive receptors could be expressed by granule cells, even if not supported by the literature, was the simplest explanation for the presynaptic effect of this compound. Since activation of mGluR1s increases calcium concentration through production of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), we tested the putative presence of presynaptic mGluR1s with fluorometric measurements of calcium variation in PFs or granule cells loaded with calcium-sensitive fluorescent dyes. Changes in resting calcium concentration were studied using the high-affinity dye fluo-3 AM in order to detect small to moderate variations. Changes in the amplitude of evoked calcium transients from PFs were studied using the low-affinity dye fluo-4-FF AM in order to avoid distortion of signal due to saturation of the dye by moderate to high variations of calcium concentration (see Methods). In granule cell somata, bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD did not induce any change in calcium concentration (n = 7, Fig. 3A). In contrast, these cells displayed prominent calcium transient rises in response to bath applications of 50 μm glutamate (n = 7, Fig. 3A), as expected from healthy cells bearing ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs). In PFs, calcium signals resulting from specific activation of mGluRs were investigated while superfusing the slices with the iGluR antagonists CNQX (10 μm) and d-APV (100 μm). In these conditions, 1S,3R-ACPD did not change the resting calcium concentration (n = 13, Fig. 3B). The amplitude of calcium transients evoked by PF stimulation was also unchanged (n = 5, Fig. 3C). However, in the same conditions, activation of mGluR4s located on PFs, by bath application of 100 μm l-AP4 (a specific agonist of group III mGluRs) led to a decrease of 17.2 ± 0.8 % of action potential-mediated calcium transients in PFs (Fig. 3C), indicating that this method was sensitive enough to detect changes of evoked calcium transient that decrease PF EPSCs by the same range of amplitude as 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (see Conquet et al. 1994). Consistent with previous histochemical studies and with electrophysiological results presented above, these results indicate that granule cells and PFs do not express functional mGluR1s or any other mGluR from either group I or II. However, when the iGluR antagonists CNQX and d-APV were removed from the bathing medium, 1S,3R-ACPD caused a reversible increase of calcium concentration in PFs in 10 out of 15 experiments (ΔF/F = 1.35 ± 0.12 %, Fig. 3B, Student's t test, P < 0.05). These data suggest that the increase in calcium concentration elicited by 1S,3R-ACPD did not result from a direct activation of presynaptic mGluRs but from the indirect activation of some iGluRs expressed on PFs. Additional experiments showed that these 1S,3R-ACPD-induced calcium transients in PFs were not blocked by bath application of 1 μm TTX (n = 4), supporting the view that these iGluRs are located on PFs rather than on granule cell somata.

Figure 3. Effects of 1S,3R-ACPD on calcium fluorometric measurements from PFs and granule cells.

Each panel represents a separate experiment. Data are means ± s.e.m. of 3 consecutive points obtained during acquisition except for C, which shows raw sweeps. A, example of fluorescence measurements of calcium changes (ΔF/F) recorded from the soma of fluo-3-loaded granule cells revealed the lack of calcium changes during bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (left), in contrast to the calcium transient increase evoked in the same cells by bath application of 50 μm glutamate (right). B, example of fluorescence measurements of calcium changes (ΔF/F) in a population of fluo-3-labelled PFs during the application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (filled bar) in the presence of CNQX (10 μm) and d-APV (100 μm) (hatched bar) (left), or after wash-out of these antagonists (right). C, left panel, example of calcium increases (in the presence of CNQX and d-APV) evoked in a set of PFs loaded with the low affinity dye fluo-4-FF AM by their stimulation, in control, in the presence of 1S,3R-ACPD and during wash-out of 1S,3R-ACPD. Right panel, same as left, in control, in the presence of the group III agonist and during wash-out of l-AP4. D, example of fluorescence measurements of calcium changes (ΔF/F) in a population of fluo-3-labelled PFs during the local co-application through a theta-tube of NMDA + kainate (100 μm each, 1 min, horizontal filled bar) on the set of loaded PFs. Recordings made in the presence of the group I, II and III mGluR antagonists (200 μm each) and of TTX (1 μm) (hatched bar). Vertical scale bars are ΔF/F multiplied by 100 to give the percentage change.

Immunolabelling studies (Petralia et al. 1994a) and recent electrophysiological indications (Casado et al. 2000) show the presence of iGluRs on PFs. However, functional characterization of presynaptic iGluRs is difficult due to their presence on many cell types in the cerebellar cortex. To further clarify this issue, we looked for direct effects of iGluR agonists on PFs using fluorometric measurements of presynaptic calcium changes. NMDA and kainate (100 μm each) were co-applied on PFs using a theta-tube oriented in the molecular layer in such a way that granule cell somata of the recorded folium were not reached by the flow from the theta tube. In addition, TTX was added to the superfusate to prevent any calcium increase that could be driven by action potentials originating from granule cell somata. A mixture of groups I, II and III mGluR antagonists, respectively AIDA, MSOPPE and MSOP (200 μm each), was also added to the bathing medium at least 10 min prior to the application of the iGluR agonists in order to isolate iGluR responses. In these conditions, applications of NMDA and kainate together induced clear transient calcium increases in PFs loaded with fluo-3 AM (ΔF/F = 1.9 ± 0.5 %, n = 5, Fig. 3D), confirming the presence of iGluRs on PFs. Thus bath application of 1S,3R-ACPD leads to an indirect activation of iGluRs located on PFs, which confirms the presynaptic nature of its effect and indicates that this effect relies on an intermediary compound released in the molecular layer during 1S,3R-ACPD bath applications, most probably glutamate.

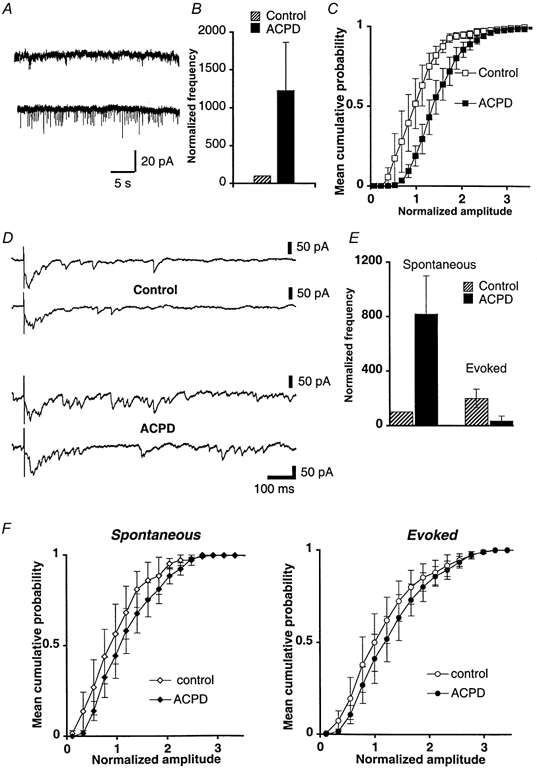

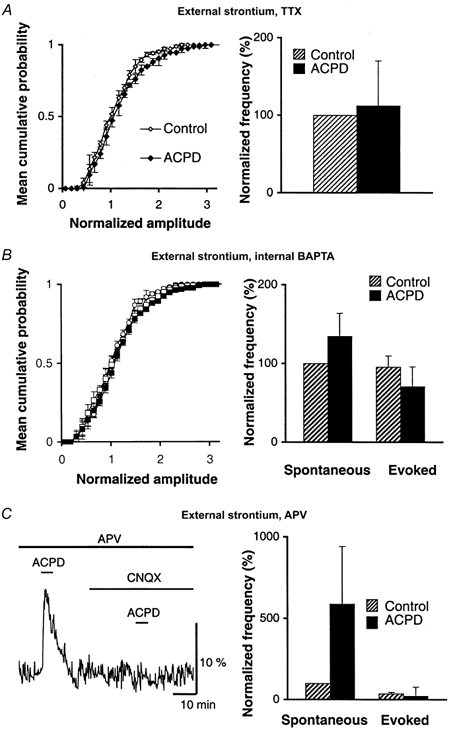

Such an elevation of presynaptic calcium concentration by 1S,3R-ACPD should activate PF terminals, and then should change the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) recorded in PCs. Indeed, bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD increased the frequency of sEPSCs to 1200 ± 520 % of the control (Student's paired t test, P < 0.05, n = 5, Fig. 4A and B). The mean amplitude of sEPSCs was also significantly increased by 1S,3R-ACPD to 128.0 ± 10.3 % of control (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P < 0.05, n = 5, Fig. 4C). This is consistent with our previous results showing that 1S,3R-ACPD increases the amplitude of currents induced in PCs by ionophoresed glutamate (Fig. 1Cc). It can be argued that an increase in the amplitude of sEPSCs could cause, by itself, an apparent increase in their frequency. However, raw and cumulative distribution of amplitude of these events in control and in the presence of 1S,3R-ACPD are very similar in shape, displaying only a right-shift during 1S,3R-ACPD application (Fig. 4C). This indicates that no new classes of amplitudes appear during the application of this compound and, thus, the increase in frequency of sEPSCs cannot be accounted for by their increase in amplitude. Finally, 1S,3R-ACPD had no effect on the properties of sEPSCs (n = 3) in mGluR1-deficient mice, showing that these effects are mediated by mGluR1s. These results confirm (see Fig. 1Cc) that the postsynaptic effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on PF to PC synaptic transmission is potentiating and, therefore, is opposite to its depressant effect on PF EPSCs. It remains to be clarified how these pre- and postsynaptic potentiating effects of 1S,3R-ACPD ultimately lead to a depression of synaptic transmission between PFs and PCs. To answer this question, we recorded synaptic events evoked by PF stimulation using a method based upon substitution of strontium for calcium in the bathing medium (Miledi, 1966; Goda & Stevens, 1994). In such a bathing medium, PF-mediated synchronous EPSCs were markedly reduced in amplitude, and asynchronous release of glutamate was markedly and selectively enhanced over a few hundreds of milliseconds after the stimulus (Fig. 4D). This allows a detailed analysis of evoked EPSCs (eEPSCs) of probably quantal nature originating specifically from PF to PC synapses. In strontium, 1S,3R-ACPD elicited a slight increase in the amplitude of sEPSCs and eEPSCs (Fig. 4F, n = 6), and increased the frequency of sEPSCs to 819 ± 250 % of the control (Fig. 4D, Student's paired t test, P < 0.05). However, the increase in amplitude and frequency of sEPSCs was less prominent in strontium than in calcium (see Fig. 4A, D and E). Strontium is less efficient in mediating calcium-dependent processes compared to calcium itself (Morishita & Alger, 1997; Xu-Friedman & Regehr, 2000), suggesting that these increases in both amplitude and frequency induced by 1S,3R-ACPD depend upon calcium. In contrast to sEPSCs, the frequency of eEPSCs was reduced to 5.3 ± 35 % of the control (Fig. 4E, Student's paired t test; P < 0.05, see Methods). This reduction of eEPSC frequency is consistent with the presynaptic depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on PF EPSCs. In addition, for each of the experiments carried out in strontium, we also ascertained that, as in a standard calcium medium, the amplitude of the residual synchronous PF EPSC was still reduced by 1S,3R-ACPD. In conclusion, the increase of calcium concentration in PFs elicited by 1S,3R-ACPD leads to an increase of spontaneous release of glutamate and to a decrease of evoked release of glutamate from these fibres. Further experiments (n = 5) showed that bath application of TTX (1 μm) blocked the effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on spontaneous EPSCs (n = 5, Fig. 5A). Thus 1S,3R-ACPD affects action potential-dependent sEPSCs, but not miniature EPSCs. Together with the fact that calcium changes elicited in PFs by 1S,3R-ACPD persist in the presence of TTX (see above), these results suggest that the presynaptic iGluRs that are indirectly activated by 1S,3R-ACPD are located at some distance from active zones of PFs.

Figure 4. Effects of 1S,3R-ACPD on spontaneous and evoked excitatory events.

A–C, experiments in external calcium medium. A, example of 30 s sweeps recorded from a PC in control (top) or in the presence of 25 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (bottom). B, bar graph of mean detection rates (+s.e.m., n = 5) of spontaneous EPSCs recorded in calcium standard bathing medium, in control (hatched bar), and in the presence of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (filled bar). The histograms are normalized relative to the mean detection rate of spontaneous unitary EPSCs in control solution. Cells analysed here are the same as in C. C, superimposed distributions of cumulative normalized amplitude (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5) of spontaneous events, in control calcium medium (□), and in calcium medium containing 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (▪). D-F, experiments in external strontium medium. D, examples of desynchronized PF EPSCs recorded in a PC when external calcium was replaced by strontium, in control (top) and in the presence of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (bottom). Total acquisition sweeps were of 1.4 s duration; spontaneous and evoked EPSCs were detected in two time windows as described in Methods. E, bar graph of mean detection rates ( ± s.e.m., n = 6) of spontaneous (left) and evoked EPSCs (right), in control (hatched bars), and in the presence of 1S,3R-ACPD (filled bars). The histograms are normalized relative to the mean detection rate of spontaneous events in control solution. Cells analysed here are the same as in F. F, left graph, superimposed distributions of cumulative normalized amplitudes of spontaneous EPSCs (mean ± s.e.m., n = 6 cells), in control strontium medium (⋄), and in the presence of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (♦). Right graph, same as left graph but for evoked events.

Figure 5. Effects of 1S,3R-ACPD on miniature events in PCs loaded with BAPTA and in the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist d-APV.

All experiments from this figure were made in strontium-containing medium. A, left, superimposed cumulative distributions of normalized amplitude of miniature EPSCs recorded from 5 PCs in TTX alone (control, ⋄) or in TTX + 1S,3R-ACPD (ACPD, ♦). Right, bar graph of mean detection rates (+s.e.m.) of miniature EPSCs presented on the left. The histograms are normalized relative to the mean detection rate of miniature EPSCs in control solution (TTX). B, data pooled from 7 PCs loaded with 30 mm BAPTA. Left, superimposed cumulative distributions of normalized amplitude of spontaneous (circles) and evoked (diamonds) events recorded in control (open symbols) or in the presence of 1S,3R-ACPD (filled symbols). Right, histograms of mean detection rates (+s.e.m.) of events described on the left. The histograms are normalized relative to the mean detection rate of spontaneous EPSCs recorded under control conditions (strontium-containing medium, BAPTA-loaded PCs, no 1S,3R-ACPD). C, d-APV does not block the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD. Left, a raw example of fluorescence (ΔF/F) recorded from a population of fluo-3-labelled PFs during 5 min bath application of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD, in the presence of d-APV alone and in the presence of d-APV + CNQX, as indicated by horizontal bars. Right, bar graph of mean detection rates (+s.e.m.) of spontaneous and evoked events recorded from 7 PCs in control (hatched bars) and in the presence of 50 μm 1S,3R-ACPD (filled bars). The bars are normalized relative to the mean detection rate of spontaneous EPSCs recorded in control.

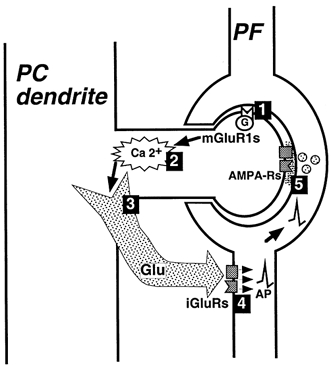

Experiments described so far show that 1S,3R-ACPD depolarizes PFs through the indirect activation of presynaptic iGluRs. This can be visualized at the presynaptic level as a calcium rise in PFs, and at a postsynaptic level as an increase in the frequency of sEPSCs. These experiments imply that some glutamate is released in the molecular layer in the presence of 1S,3R-ACPD, but do not indicate the origin of this glutamate. For instance, glutamate released during high firing of PFs induced by 1S,3R-ACPD could spill over to presynaptic iGluRs located on these fibres. On the other hand, PCs might also be able to release glutamate in an internal calcium-dependent manner following their depolarization (Glitsch et al. 1996). Moreover, the fact that PC dendrites are particularly enriched in mGluR1, together with the fact that activation of these receptors subsequently increases internal calcium (see Takechi et al. 1998), make these cells good candidates for undergoing a calcium-dependent release of glutamate during the application of 1S,3R-ACPD. In order to discriminate between these possibilities, we studied the effects of this compound on spontaneous and evoked events recorded in PCs loaded with a calcium chelator. To record evoked events, these experiments had to be done in strontium-containing medium; we selected BAPTA as a buffer because it binds efficiently to strontium (Rumpel & Behrends, 1999). This is important because, like calcium, strontium may be loaded in internal stores (Fujimori & Jencks, 1992; see also Xu-Friedman & Regehr, 1999) and can replace calcium in triggering calcium-dependent phenomena such as excitation-contraction coupling or exocytosis. Loading PCs with 30 mm BAPTA nearly fully abolished the effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on spontaneous and evoked events, rendering their frequencies not significantly different from control values (n = 7, paired t test Fig. 5B). These results show that the effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on spontaneous and evoked events originates from PCs and depends upon internal calcium in these cells. It can be thus proposed that 1S,3R-ACPD leads to a calcium-dependent release of glutamate from PCs which retrogradely activates iGluRs expressed by PFs (see schematic summary in Fig. 8). A recent electrophysiological study (Casado et al. 2000) shows that PFs express NMDA receptors whose activation decreases PF EPSCs. Such an effect could explain the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD studied here. To test this possibility, the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD on frequency and amplitude of evoked and spontaneous excitatory events were tested in the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist d-APV (100 μm). We found no difference between the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD in these experiments and in controls (n = 6, Student's t test, P > 0.7, Fig. 5C). Confirming these findings, the effects of 1S, 3R-ACPD on PF-mediated EPSCs and on their PPF were also unchanged by the blocking of NMDA receptors with d-APV (100 μm, n = 3, not illustrated). Finally, in the presence of d-APV (100 μm), 1S,3R-ACPD still increased calcium concentration in PFs (n = 3, mean increase of ΔF/F of 4.5 ± 2.2 %, Fig. 5C), while this effect was still abolished by CNQX (10 μm). Thus, NMDA receptors do not underlie the presynaptic depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD. Rather, AMPA or kainate receptors expressed by PFs are involved in this phenomenon. However, this was difficult to test because of the lack of selective kainate receptor antagonists together with the fact that selectively blocking AMPA receptors (with GIKY53655 for instance) would lead to the suppression of excitatory synaptic transmission.

Figure 8. Scheme summarizing the retrograde control of PF activity by PCs.

1, activation of mGluR1 in the PC, either pharmacologically or by tetanic stimulation of PFs. 2, subsequent increase in calcium (Ca2+) concentration in the PC. 3, calcium-dependent release of a retrograde messenger, most probably glutamate (Glu). 4, activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) located in PFs and subsequent depolarization of PFs which propagates to their terminals through action potential (AP)-dependent process. 5, PF terminals undergo vesicular release of glutamate, observed at the level of PCs as an increase in frequency of spontaneous EPSCs and a decrease in frequency of evoked ones. This retrograde depolarization of PFs caused by the activation of postsynaptic mGluR1s explains the decrease in the amplitude of PF EPSCs during mGluR1 activation.

Glutamate released in the molecular layer during application of 1S,3R-ACPD could not only activate these presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors but could also reach presynaptic mGluR4s located at PF terminals, thereby contributing to the observed decrease of PF EPSCs. However, the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD on PF EPSCs and on their PPF remained unchanged when mGluR4s were blocked by the group III mGluR antagonist MSOP (n = 5, 200 μm, Fig. 6A) or when they were activated by steady application of the group III agonist l-AP4 prior to and during 1S,3R-ACPD application (100 μm, n = 4, not shown). Thus, the presynaptic depolarization induced by 1S,3R-ACPD seems to directly account for the depressant effect of this compound on evoked synaptic transmission at synapses between PFs and PCs. Usually at these synapses facilitation of synaptic transmission, rather than depression, accompanies presynaptic calcium increases (Kreitzer & Regehr, 2000). Because 1S,3R-ACPD was applied in the bath, thereby activating numerous PCs, there was a possibility that the resulting strong presynaptic depolarization would depress synaptic transmission, whereas more physiological slight and local activation of mGluR1s would facilitate synaptic transmission through a moderate presynaptic activation. However, very focal ionophoretic applications of 1S,3R-ACPD (1 mm in a patch-like pipette) in the distal dendritic field of the recorded PCs still decreased PF EPSCs to 21 ± 4 % of the control amplitude (n = 3) and increased sEPSCs similarly to that described above (n = 3).

These results favour the idea that the release of endogenous glutamate from PCs during the activation of mGluR1 is probably dendritic and indicates that the retrograde depression caused by mGluR1s might have a physiological relevance. This possibility was then more directly addressed. Activation of mGluR1s, which are highly concentrated in peri-synaptic zones at PF to PC synapses (Martin et al. 1992; Baude et al. 1993), occurs following high frequency discharge of PFs, probably due to glutamate spillover (Batchelor et al. 1994; Takechi et al. 1998). In vivo, PFs fire at a high frequency level (50 to hundreds of Hz). Therefore, in a standard calcium bathing medium, pharmacological activation of mGluR1s was replaced by a train of five to eight stimulations of PFs at 100 Hz, a protocol known to activate mGluR1s on PCs (Batchelor et al. 1994; Takechi et al. 1998). In 11 out of 16 cells tested, this short tetanic stimulation of PFs led to the appearance of numerous excitatory events that were named post-tetanic sEPSCs (Fig. 7A). The frequency of these events increased with the number of pulses in the train. No change of sEPSC frequency was observed with one to three pulses in the train (Fig. 7B), whereas maximal increase in frequency was obtained with seven pulses (Fig. 7A). The increase in the frequency of sEPSCs after a tetanus (7 pulses at 100 Hz) was 104.1 ± 21.6 % (n = 11). For 5 out of 16 cells tested, the frequency of sEPSCs was unchanged after the tetanus; nevertheless, the increase in frequency of post-tetanic sEPSCs was significant taking into account the entire population (n = 16, Student's paired t test, P < 0.01). Loading the recorded PC with 30 mm BAPTA strongly inhibited the increase of post-tetanic sEPSC frequency. Indeed, this increase was 91.3 ± 18.1 % before diffusion of BAPTA (10 min following whole-cell break-in) and 27.0 ± 5.9 % after (30 min after whole-cell break-in, n = 4, Student's paired t test, P < 0.02, Fig. 7C). In control experiments, the increase in post-tetanic sEPSCs was very stable as it remained unchanged up to 45 min after whole-cell break-in; therefore, the blockade of post-tetanic sEPSCs by BAPTA was not due to run-down of the phenomenon studied here. Finally, in 3 of 5 cells tested, the group I mGluR antagonist AIDA blocked the increase in post-tetanic sEPSCs, as frequency increased by 103.2 ± 15.2 % in the control, and by 41.7 ± 10.4 % in the presence of 200 μm AIDA (Fig. 7C). In the other two cells, AIDA had no effect. As previously shown, PF stimulation can elevate the calcium concentration in PC dendrites even when mGluRs are blocked (see Eilers et al. 1995). Therefore, the variability of the effects of AIDA might result from an mGluR-independent rise of calcium in the recorded PC, as might occur in distal dendrites, for instance because of voltage-clamp escape caused by the summated PF EPSCs during the tetanus (Llano et al. 1991b). Supporting this view, it is worth mentioning that for the three cells where AIDA blocked the increase in post-tetanic sEPSCs, the intensity of PF stimulation was lower than for the two cells where AIDA had no effect. Altogether, these results suggest that activation of mGluR1s by a tetanic stimulation of PFs, similarly to their pharmacological activation, elicits a calcium-dependent release of glutamate from PCs and a subsequent depolarization of PFs. The effect in PFs can be observed in PC recordings as an increased rate of sEPSCs following the tetanus. Thus, PCs might exert a retrograde control of PF activity under physiological conditions following a repetitive discharge of PFs.

Figure 7. A tetanic stimulation of PFs increases the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs.

A, example of a sweep showing the increase in the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs elicited by a 100 Hz train of 7 PF stimulations (arrows). B, example of a sweep recorded from the same PC as in A, showing that 1 PF stimulation does not change the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs. C, bar graph summarizing the effects of a train of 7 PF stimulations on the frequency of spontaneous EPSCs (the three filled bars) normalized relative to their frequency during the pre-tetanus control period (hatched bar) in control, for PCs loaded with 30 mm BAPTA (n = 4) or in the presence of the group I mGluR antagonist AIDA (200 μm, n = 3).

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that the activation of mGluR1s in PCs causes the opening of presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors located on PFs by a retrograde messenger, probably glutamate, released from PCs (Fig. 8). The resulting depolarization of PFs leads, in turn, both to an increased rate of spontaneous excitatory events and to a decreased rate of evoked ones. The latter effect underlies the well known depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on synaptic transmission between PFs and PCs.

The presynaptic location of the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on PF EPSCs is supported by the analysis of short-term plasticity (increased PPF) and of amplitude fluctuations (increased CV), and by the changes observed in frequencies of spontaneous and evoked excitatory events during application of this drug. The fact that 1S,3R-ACPD increases, rather than decreases, PC responses to ionophoretic glutamate pulses in PCs indicates that its depressant effect on synaptic transmission is not of postsynaptic origin. However, ionophoretic pulses of exogenous glutamate activate both synaptic and extra-synaptic iGluRs on PCs. Activation of these latter could thus mask a decreased sensitivity of synaptic receptors. This possibility was ruled out by the fact that the amplitude of synaptic events was also increased by 1S,3R-ACPD, as shown by the analysis of PF-evoked events recorded in the presence of strontium. Such an increased sensitivity of neurones to neurotransmitter following depolarization is not surprising as it was previously observed in cerebellar Purkinje cells (Llano et al. 1991a; Glaum et al. 1992) and also exists in the hippocampus (Wyllie et al. 1994). The increased sensitivity of PCs to glutamate and the decreased probability of evoked release of glutamate from PF terminals that are induced by mGluR1s could contribute to bringing out synapses active in such a context. However, the present experiments do not allow any conclusion about the function of this postsynaptic enhancement of sensitivity to glutamate.

The inward current induced in PCs by 1S,3R-ACPD could have been responsible for the decrease of PF EPSCs, because of changes in membrane resistance, or because of changes in PF release parameters due to potassium efflux from the depolarized PCs. However, the decrease of PF EPSCs lasts longer than the inward current (see first paragraph of Results), and, after recovery of the initial holding current of the cell, there is no change in the slope of the rising phase of PF EPSCs by 1S,3R-ACPD while they are still depressed. Moreover, the amplitude of sEPSCs and of PC responses to ionophoresed glutamate are clearly increased by 1S,3R-ACPD, indicating that 1S,3R-ACPD does not decrease PF to PC synaptic transmission through a modification of membrane resistance of PCs. Indeed, such an effect would have produced a decrease of these parameters instead of the observed increase. Finally, the presynaptic calcium increase induced by 1S,3R-ACPD is very likely to cause the enhancement of spontaneous release by PFs observed in the presence of this drug. If this effect were due to postsynaptic potassium efflux, it would not have been blocked by CNQX.

1S,3R-ACPD is a broad agonist of groups I and II mGluRs. Both are widely expressed in the cerebellar cortex, especially by inhibitory interneurones. However, this study establishes that the depressant effect of this compound relies on mGluR1s and is triggered by PCs themselves, with negligible contribution of GABAergic interneurones in our conditions (i.e. in the presence of bicuculline). Although this is difficult to directly demonstrate, this study strongly supports the existence of an mGluR1-mediated retrocontrol of PF activity by PCs. This phenomenon shares common mechanisms with previously described calcium-dependent somato-dendritic release of neurotransmitter (Zilberter et al. 1999, 2000), especially with the depolarization-induced suppression of inhibition (DSI), which is a case of retrograde signalling mediated by a messenger released from PCs (Glitsch et al. 1996). In our case, however, the elevation of intracellular calcium in PCs is provided by the activation of mGluR1s. DSI was also found in the hippocampus following pyramidal cell depolarization (Alger et al. 1996). Original studies of DSI in the hippocampus indicated the involvement of a depolarization-induced release of glutamate (Morishita et al. 1999), but a recent publication shows that DSI implies the release of endogenous cannabinoids from pyramidal cells rather than glutamate (Wilson & Nicoll, 2001). However, our results clearly indicate that cannabinoids are not implicated in the mGluR1-mediated depression of PF to PC synaptic transmission. In the case of mGluR1-mediated retrograde depression of PF EPSCs, the blockade by iGluR antagonists of 1S,3R-ACPD-mediated presynaptic calcium changes, together with the presence of these receptors on PFs and the increase in sEPSC frequency elicited by this compound, indicates that the retrograde messenger is most probably glutamate. Its release is calcium dependent but our results do not allow any conclusion about its nature, for instance through vesicle release or reverse transport. It is also possible that PCs release a compound that leads an intermediary cell, for instance a glial cell, to release glutamate. A release of glutamate directly from PCs is the simplest and more direct explanation. In the recent literature, there is increasing evidence for dendritic release of GABA (Zilberter et al. 1999) or glutamate (Schoppa et al. 1998; Aroniadou-Anderjaska et al. 1999; Zilberter, 2000) from neurones. A dendritic release of glutamate would be expected to activate postsynaptic iGluRs of PCs and thus to contribute to the inward current induced in these neurones by 1S,3R-ACPD. As previously observed (Glaum et al. 1992), additional experiments failed to evidence such an effect, as 20 μm CNQX did not significantly reduce the amplitude of the 1S,3R-ACPD-induced inward current (n = 5, not illustrated). This may simply be due to the capping of PF-PC synapses (Barbour et al. 1994), preventing glutamate released from PC dendrites from reaching postsynaptic iGluRs in the synaptic cleft (Fig. 8). The fact that mGluR4s, also located at these capping synapses, do not contribute to the mechanism described here reinforces this view.

Even though NMDA receptors are expressed by PFs (Casado et al. 2000), the lack of blockade of the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD by d-APV demonstrates that these receptors do not underlie the presynaptic depolarization nor the depression of synaptic transmission by mGluR1s. This is in accordance with the fact that the decrease of PF EPSCs elicited by presynaptic NMDA receptors relies on the postsynaptic depressant effect of NO. Indeed, we show here that two different types of NO synthase antagonists failed to inhibit the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD, thereby excluding the involvement of NO in the depressant effect of 1S,3R-ACPD. Moreover, the activation of NMDA receptors on PFs does not change the PPF of PF EPSCs (Casado et al. 2000), while PPF is clearly changed in our study. Finally, our results show that 1S,3R-ACPD has a postsynaptic potentiating effect (see ionophoretic application of glutamate, spontaneous and evoked quantal EPSCs), while Casado et al. (2000) showed that the activation of NMDA receptors on PFs produced postsynaptic depression. In conclusion, it is more likely that the mGluR1-mediated retrograde depolarization of PFs evidenced here relies on AMPA or kainate receptors. The fact that TTX blocked the effect of 1S,3R-ACPD on the rate of sEPSCs while not blocking calcium transients induced by this compound in PFs indicates that these presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors are located along PFs at some distance from active zones (Fig. 8). The reason why glutamate released in the presence of 1S,3R-ACPD activates presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors but not presynaptic NMDA receptors could be that these receptors are not co-located. Indeed, Casado et al. (2000) showed that NMDA does not change PF volley suggesting that NMDA receptors might be located at or near PF terminals themselves.

GluR5, 6 and/or 7 and KA2 subunits of kainate receptors are expressed in the molecular layer (Petralia et al. 1994b), and GluR5, 6 and/or 7 were even detected on parallel fibres (Zhao et al. 1997), but precise location and functional characterization of these receptors at presynaptic loci in the cerebellum is still unclear. Presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors were found to control the release of neurotransmitters in the hippocampus, the cerebral cortex and spinal cord (Rodriguez-Moreno et al. 1997; Sundstrom et al. 1998; Perkinton & Sihra, 1999). It was also observed that presynaptic kainate receptors depolarize isolated dorsal root fibres and subsequently depress electrically evoked C-fibre responses (Davies et al. 1982; Agrawal & Evans, 1986). Recently, in the hippocampus, presynaptic kainate receptors were shown to elicit an inhibition of evoked excitatory synaptic transmission through an increase in the excitability of afferent fibres (Schmitz et al. 2000). Our data suggest that in the cerebellum as well, presynaptic AMPA/kainate receptors depress synaptic transmission between PFs and PCs through depolarization of PFs.

How is it that such a presynaptic depolarization leads to a reduced probability of evoked release of glutamate from PFs? It is possible that sustained depolarization of PFs causes the depletion of their readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles, and that only reluctantly releasable vesicles, which have a lower probability of release, remain available for synaptic transmission. Since synapses between PFs and PCs tend to facilitation (Dittman et al. 2000), there may be a period when calcium concentration in PF terminals is high enough to facilitate synaptic transmission before substantial depletion and consequent depression. Indeed, in some experiments, the depression of PF EPSCs by 1S,3R-ACPD was sometimes preceded by a slight increase in their amplitude (C. Levenes & F. Crepel, unpublished observation). In this hypothesis, the increase in the frequency of spontaneous events should be followed by a decrease in frequency. Our data do not provide evidence for such a phenomenon. However, the use of bath applications renders temporal analysis of the effects of 1S,3R-ACPD difficult. An alternative to explain the depressant effect of a presynaptic depolarization is that the opening of AMPA/kainate receptors expressed by PFs shunts action potentials propagating along these fibres, thereby decreasing evoked synaptic transmission. In this scheme, the opening of AMPA/kainate receptors does not necessarily need to be sustained to disrupt action potential propagation; thus, this mechanism could be a priori of physiological occurrence. Whether a depletion of readily releasable vesicles actually takes place during physiological activation of mGluR1s is more difficult to estimate. Whatever the mechanism, the fact that pharmacological activation of mGluR1s could be replaced by a tetanus to trigger the retrograde depolarization of PFs indicates that this phenomenon does not require a massive activation of mGluR1s as might occur during bath applications. PFs have a high frequency pattern of discharge in vivo (see Thach, 1998). The mechanism described in this study could thus take place in physiological conditions.

Glutamate as a retrograde messenger could modulate excitatory as well as inhibitory neighbouring elements. Thus, retrograde depolarization of PFs might spread to other synapses located in the same beam of PFs. This would introduce a form of local communication among a stack of PCs which share the same PF input, whereas DSI of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs) results in a lateral spread of information in the plane orthogonal to the PFs, i.e. the sagittal plane (see Vincent & Marty, 1993).

In conclusion, the present study elucidates mechanisms by which activation of postsynaptic mGluR1s ultimately causes reversible depression of synaptic transmission at PF to PC synapses. It also provides evidence that repetitive PF activation not only causes postsynaptic mGluR1-dependent modifications in PCs, thereby contributing to cerebellar long-term depression (reviewed in Daniel et al. 1998), but also leads to a retrograde control of presynaptic activity by PCs. This may be of general interest given that, in any structure considered, long-term synaptic plasticity is generally induced by strong afferent stimulation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a European grant BIOTECH No. CT96-0049. We thank Drs Alain Marty and Jean-Gael Barbara for valuable advice and comments on the manuscript. We also thank Gérard Sadoc for the Acquis1 software and Norbert Ankri for the Detectivent software used in this study.

References

- Agrawal SG, Evans RH. The primary afferent depolarising action of kainate in the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1986;87:345–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1986.tb10823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger BE, Pitler TA, Wagner JJ, Martin LA, Morishita W, Kirov SA, Lenz RA. Retrograde signalling in depolarisation-induced suppression of inhibition in rat hippocampal CA1 cells. Journal of Physiology. 1996;496:197–209. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankri N, Legendre P, Faber D, Korn H. Automatic detection of spontaneous synaptic responses in central neurons. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1994;52:87–100. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska V, Ennis M, Shipley MT. Dendrodendritic recurrent excitation in mitral cells of the rat olfactory bulb. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:489–494. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri P, Regehr W. Determinants of the time course of facilitation at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:5661–5671. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05661.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour B, Keller BU, Llano I, Marty A. Prolonged presence of glutamate during excitatory synaptic transmission to cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuron. 1994;12:1331–1343. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90448-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor AM, Madge DJ, Garthwaite J. Synaptic activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the parallel fibre-Purkinje cell pathway in rat cerebellar slices. Neuroscience Letters. 1994;63:911–915. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90558-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Nusser Z, Roberts JD, Mulvihill E, McIlhinney RA, Somogyi P. The metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1α) is concentrated at perisynaptic membrane of neuronal subpopulations as detected by immunogold reaction. Neuron. 1993;11:771–787. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blond O, Daniel H, Jaillard D, Crepel F. Presynaptic and postsynaptic effects of nitric oxide at synapses between parallel fibers and Purkinje cells: involvement in cerebellar long-term depression. Neuroscience. 1997;77:945–954. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado M, Dieudonne S, Ascher P. Presynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors at the parallel fiber-purkinje cell synapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2000;97:11593–11597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200354297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis P, Fagni L, Bockaert J, Lansman JB. Modulation of calcium channels by metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:929–937. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00082-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochilla AJ, Alford S. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated control of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conquet F, Bashir ZI, Davies CH, Daniel H, Ferraguti F, Bordi F, Franz-Bacon K, Reggiani A, Matarese V, Condé F, Collingridge GL, Crepel F. Motor deficit and impairment of synaptic plasticity in mice lacking mGluR1. Nature. 1994;372:237–243. doi: 10.1038/372237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepel F, Daniel H, Hemart N, Jaillard D. Effects of ACPD and AP3 on parallel-fibre-mediated EPSPs of Purkinje cells in cerebellar slices in vitro. Experimental Brain Research. 1991;86:402–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00228964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel H, Levenes C, Crepel F. Cellular mechanisms of cerebellar LTD. Trends in Neurosciences. 1998;21:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Evans RH, Jones AW, Smith DA, Watkins JC. Differential activation and blockade of excitatory amino acid receptors in the mammalian and amphibian central nervous systems. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 1982;C 72:211–224. doi: 10.1016/0306-4492(82)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Interplay between facilitation, depression, and residual calcium at three presynaptic terminals. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:1374–1385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01374.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Regehr WG. Contributions of calcium-dependent and calcium-independent mechanisms to presynaptic inhibition at a cerebellar synapse. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16:1623–1633. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01623.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers J, Augustine GJ, Konnerth A. Subthreshold synaptic Ca2+ signalling in fine dendrites and spines of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Nature. 1995;373:155–158. doi: 10.1038/373155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori T, Jencks WP. The kinetics for the phosphoryl transfer steps of the sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase are the same with strontium and with calcium bound to the transport sites. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:18466–18474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum SR, Slater NT, Rossi DJ, Miller RJ. Role of metabotropic glutamate (ACPD) receptors at the parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapse. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;68:1453–1462. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.4.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glitsch M, Llano I, Marty A. Glutamate as a candidate retrograde messenger at interneurone-Purkinje cell synapses of rat cerebellum. Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:531–537. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y, Stevens C. Two components of transmitter release at a central synapse. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:12942–12946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandes P, Mateos JM, Ruegg D, Kuhn R, Knopfel T. Differential cellular localization of three splice variants of the mGluR1 metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat cerebellum. NeuroReport. 1994;5:2249–2252. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199411000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A, Ohishi H, Nomura S, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Presynaptic localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR4a, in the cerebellar cortex: a light and electron microscope study in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;207:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Modulation of transmission during trains at a cerebellar synapse. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:1348–1357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01348.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann DM. Amplitude fluctuations of dual-component EPSCs in hippocampal pyramidal cells: implications for long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1994;12:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90318-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenes C, Daniel H, Soubrie P, Crepel F. Cannabinoids decrease excitatory synaptic transmission and impair long-term depression in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells. Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:867–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.867bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I, Leresche N, Marty A. Calcium entry increases the sensitivity of cerebellar Purkinje cells to applied GABA and decreases inhibitory synaptic currents. Neuron. 1991a;6:565–574. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano I, Marty A, Armstrong CM, Konnerth A. Synaptic- and agonist-induced excitatory currents of Purkinje cells in rat cerebellar slices. Journal of Physiology. 1991b;434:183–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Blackstone CD, Huganir RL, Price DL. Cellular localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in rat brain. Neuron. 1992;9:259–270. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90165-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R. Strontium as a substitute for calcium in the process of transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. Nature. 1966;212:1233–1234. doi: 10.1038/2121233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita W, Alger BE. Sr2+ supports depolarisation-induced suppression of inhibition and provides new evidence for a presynaptic expression mechanism in rat hippocampal slices. Journal of Physiology. 1997;505:307–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.307bb.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishita W, Alger BE. Evidence for endogenous excitatory amino acids as mediators in DSI of GABAAergic transmission in hippocampal CA1. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1999;82:2556–2564. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohishi H, Akazawa C, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Distributions of the mRNAs for L-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyrate-sensitive metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGluR4 and mGluR7, in the rat brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;360:555–570. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkinton MS, Sihra TS. A high-affinity presynaptic kainate-type glutamate receptor facilitates glutamate exocytosis from cerebral cortex nerve terminals (synaptosomes) Neuroscience. 1999;90:1281–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia R, Yokotani N, Wenthold R. Light and electron microscope distribution of the NMDA receptor subunit NMDAR1 in the rat nervous system using a selective anti-peptide antibody. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994a;14:667–696. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00667.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petralia RS, Wang YX, Wenthold RJ. Histological and ultrastructural localization of the kainate receptor subunits, KA2 and GluR6/7, in the rat nervous system using selective antipeptide antibodies. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994b;349:85–110. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, De Colle C, Bessis AS, Acher F. New perspectives for the development of selective metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;375:277–294. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin J-P, Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr WG, Tank DW. Selective fura-2 loading of presynaptic terminals and nerve cell processes by local perfusion in mammalian brain slice. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1991;37:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90121-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Moreno A, Herreras O, Lerma J. Kainate receptors presynaptically downregulate GABAergic inhibition in the rat hippocampus. Neuron. 1997;19:893–901. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80970-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumpel E, Behrends JC. Sr2+-dependent asynchronous evoked transmission at rat striatal inhibitory synapses in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1999;514:447–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.447ae.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz D, Frerking M, Nicoll RA. Synaptic activation of presynaptic kainate receptors on hippocampal mossy fiber synapses. Neuron. 2000;27:327–338. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp DD, Goldsworthy J, Johnson BG, Salhoff CR, Baker SR. 3,5-Dihydroxyphenylglycine is a highly selective agonist for phosphoinositide-linked metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat hippocampus. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;63:769–772. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63020769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppa NE, Kinzie JM, Sahara Y, Segerson TP, Westbrook GL. Dendrodendritic inhibition in the olfactory bulb is driven by NMDA receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18:6790–6802. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06790.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staub C, Vranesic I, Knöpfel T. Responses to metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in cerebellar Purkinje cells: induction of an inward current. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;4:832–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundstrom E, Holmberg L, Souverbie F. NMDA and AMPA receptors evoke transmitter release from noradrenergic axon terminals in the rat spinal cord. Neurochemical Research. 1998;23:1501–1507. doi: 10.1023/a:1020967601813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takechi H, Eilers J, Konnerth A. A new class of synaptic response involving calcium release in dendritic spines. Nature. 1998;396:757–760. doi: 10.1038/25547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thach WT. What is the role of the cerebellum in motor learning and cognition? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1998;2:331–337. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent P, Marty A. Neighboring cerebellar Purkinje cells communicate via retrograde inhibition of common presynaptic interneurons. Neuron. 1993;11:885–893. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90118-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RI, Nicoll RA. Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature. 2001;410:588–592. doi: 10.1038/35069076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie DA, Manabe T, Nicoll RA. A rise in postsynaptic Ca2+ potentiates miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents and AMPA responses in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1994;12:127–128. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Presynaptic strontium dynamics and synaptic transmission. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:2029–2042. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77360-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Probing fundamental aspects of synaptic transmission with strontium. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:4414–4422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04414.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao HM, Wenthold RJ, Wang YX, Petralia RS. Delta-glutamate receptors are differentially distributed at parallel and climbing fibre synapses on Purkinje cells. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1997;68:1041–1052. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68031041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberter Y. Dendritic release of glutamate suppresses synaptic inhibition of pyramidal neurons in rat neocortex. Journal of Physiology. 2000;528:489–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberter Y, Kaiser KM, Sakmann B. Dendritic GABA release depresses excitatory transmission between layer 2/3 pyramidal and bitufted neurons in rat neocortex. Neuron. 1999;24:979–988. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS. Changes in the statistics of transmitter release during facilitation. Journal of Physiology. 1973;229:787–810. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]