Abstract

C-fibre activation induces a long-term potentiation (LTP) in the spinal flexion reflex in mammals, presumably to provide enhanced reflexive protection of damaged tissue from further injury. Descending monoaminergic pathways are thought to depress sensory input but may also amplify spinal reflexes; the mechanisms of this modulation within the spinal cord remain to be elucidated.

We used electrical stimulation of primary afferents and recordings of motor output, in the rat lumbar spinal cord maintained in vitro, to demonstrate that serotonin is capable of inducing a long-lasting increase in reflex strength at all ages examined (postnatal days 2–12).

Pharmacological analyses indicated an essential requirement for activation of 5-HT2C receptors while 5-HT1A/1B, 5-HT7 and 5-HT2A receptor activation was not required. In addition, primary afferent-evoked synaptic potentials recorded in a subpopulation of laminae III-VI spinal neurons were similarly facilitated by 5-HT. Thus, serotonin receptor-evoked facilitatory actions are complex, and may involve alterations in neuronal properties at both motoneuronal and pre-motoneuronal levels.

This study provides the first demonstration of a descending transmitter producing a long-lasting amplification in reflex strength, accomplished by activating a specific serotonin receptor subtype. It is suggested that brain modulatory systems regulate reflex pathways to function within an appropriate range of sensori-motor gain, facilitating reflexes in behavioural situations requiring increased sensory responsiveness.

Spinal neurons are sensitized following stimuli that activate nociceptors. This central sensitization is characterized by an increased excitability in response to sensory inputs, a prolonged afterdischarge to repeated stimulation and expanded peripheral receptive fields (Coderre et al. 1993). Repetitive activation of nociceptors can also induce long-term synaptic potentiation (LTP) in the dorsal and ventral horn of the spinal cord. These modifications occur at glutamatergic synapses since N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation is required for their induction (Randic et al. 1993; Liu & Sandkühler, 1995; Svendsen et al. 1998; Durkovic & Prokowich, 1998). LTP of the spinal flexion reflex has also been observed in cat (Durkovic & Prokowich, 1998) and rat (Anderson & Winterson, 1995). In the spinalized rat, plasticity in the flexor reflex was induced by stimulation of C fibres (Woolf & McMahon, 1985). These actions also appear to be NMDA receptor dependent (Woolf & Thompson, 1991; Anderson & Winterson, 1995; Durkovic & Prokowich, 1998). Because central sensitization and reflex LTP are similar in terms of induction, time course, NMDA receptor dependence, as well as a reduced threshold for recruitment, it is likely that these phenomena share common interneurons (Woolf et al. 1994).

Descending systems also regulate the strength of flexion reflexes. In rat and cat, spinalization results in increased flexion reflexes characterized by reduced thresholds and larger receptive fields (Sherrington, 1910; Holmqvist & Lundberg, 1961; Schouenborg et al. 1992). Activity-induced plasticity in spinal reflex pathways is also modulated by descending systems since flexor reflexes can be enhanced for hours following conditioning C fibre stimulation in the spinal rat (Woolf & Wall, 1986), but identical stimuli evoke a long-lasting inhibition in the intact anaesthetized rat (Gozariu et al. 1997). These results are consistent with observations from many studies showing that intact descending bulbospinal systems exert an inhibitory control of spinal nociceptive systems (Basbaum & Fields, 1984).

Conversely, bulbospinal modulatory systems exist that facilitate spinal nociceptive systems (Zhuo & Gebhart, 1992), the spinal mechanisms of which are unknown (Martin et al. 1999; Wei et al. 1999). The present study uses the isolated rat spinal cord to identify spinal mechanisms by which descending modulatory systems might facilitate spinal reflex activity. Some of these results have been reported in abstract form (Machacek et al. 1999).

METHODS

All experimental procedures complied with the guidelines of both the National Institutes of Health and the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Sprague-Dawley rats (postnatal days (P)10–14) were anaesthetized with 10 % urethane (2 mg (kg body weight)−1i.p.) and decapitated, and lumbar spinal segments were removed and cooled using (< 4 °C) oxygenated (95 % O2-5 % CO2) high sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (mm): sucrose, 250; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 1; MgCl2, 3; glucose, 25; NaH2PO4, 1.25; NaHCO3, 26; at a pH of 7.4. Younger animals (P3–9) were decapitated and lumbar spinal segments were removed and cooled using oxygenated normal aCSF (mm): NaCl, 125; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1; glucose, 25; NaH2PO4, 1.25; NaHCO3, 26; at a pH of 7.4.

To record reflexes, spinal cord preparations were either left intact (P3–6) or hemisected (P3–12). Constant-current stimuli were applied throughout each experiment at 0.02 Hz to a lumbar dorsal root (L2-L6) while recording the reflex response on the homologous ventral root. After obtaining a baseline evoked reflex response, 5-HT or a 5-HT receptor ligand was bath applied for 10–45 min and then washed out.

For comparisons of reflex amplitude, responses were rectified and the calculated integrals of the first 80 ms of the evoked reflex (7–87 ms post-stimulus onset) were compared before and after drug application. Stimuli were 500 μA, 100 μs unless otherwise stated. In two experiments, hindlimbs were left attached to allow for electromyographical (EMG) recording of motor unit activity in the triceps surae following stimulation of cut dorsal roots.

Serotonin (5-HT; 10 μm) and 5-HT receptor selective ligands (0.5–5.0 μm) were bath applied. The 5-HT receptor agonists used were 5-carboxamidotryptamine (5-CT), a 5-HT1A/1B receptor agonist; 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin (8-OH-DPAT), a 5-HT1A/7 receptor agonist; 1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodophenyl)-2-amino-propane (DOI), a 5-HT2A/2C receptor agonist; and MK-212, a 5-HT2C receptor agonist. The 5-HT receptor antagonists used were WAY-100635, a 5-HT1A receptor antagonist; normethyl clozapine, a 5-HT2A/2C receptor antagonist; and spiperone, a 5-HT2A/7 receptor antagonist. The NMDA receptor antagonist dl-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV) was applied at 50 μm. All ligands were obtained from RBI/Sigma (Natick, MA, USA).

Whole-cell ‘blind’ patch clamp recordings were made in laminae III-VI from thick spinal cord slices (∼600 μm) or the hemisected spinal cord at P8–14 as described previously (Garraway & Hochman, 2001) to record evoked postsynaptic potentials following stimulation of attached dorsal roots. Resting membrane potential, leak conductance and compensated series resistance (bridge balance) were monitored throughout to ensure recording stability. Synaptic potentials were recorded at the same membrane potential before, during and after 5-HT application to ensure reliable comparison of changes in synaptic potential amplitude.

RESULTS

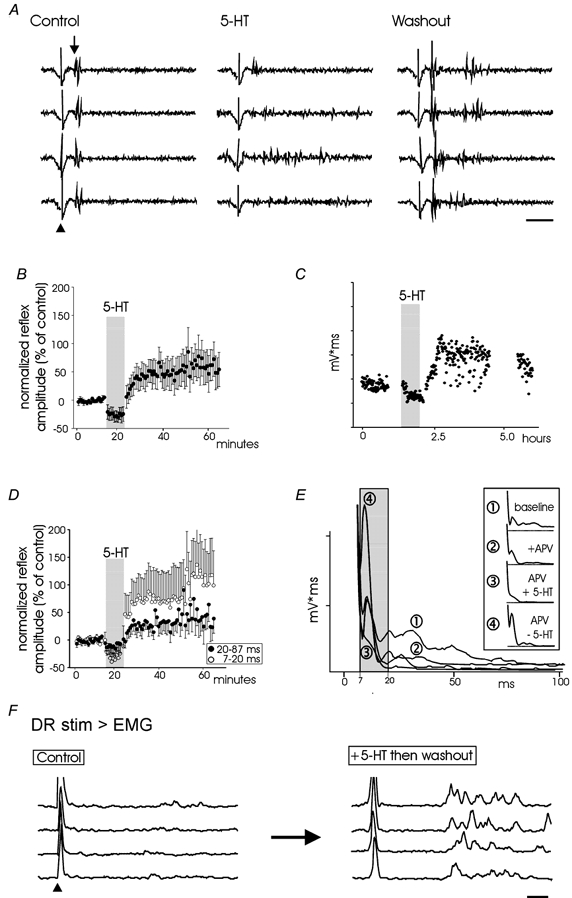

5-HT evokes a long-lasting reflex facilitation

Reflexes were measured in 43 spinal cords (mean age, P7). Following a baseline reflex of consistent amplitude (30–60 min period), superfusion of 5-HT depressed reflex responses (e.g. Crick & Wallis, 1991). However, following 5-HT washout, a long-lasting reflex facilitation (LLRF) was observed (Fig. 1A and B) throughout the age range examined in both intact and hemisected spinal cords and could be maintained for several hours (Fig. 1C). Separation of the reflexes into epochs that approximately divide monosynaptic from polysynaptic components (Crick & Wallis, 1991) demonstrated that the short-latency reflexes underwent a greater relative facilitation (Fig. 1D). In the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist APV, only the early reflex component remained (Fig. 1E). Under these conditions, the remaining short-latency AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated reflex is clearly facilitated following 5-HT washout (Fig. 1E). EMG recordings from the triceps illustrate that the reflex facilitation occurs in somatic motoneurons (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1. 5-HT evokes a long-lasting facilitation of reflexes but only following washout.

A, raw traces of reflexes evoked following dorsal root stimulation at 300 μA, 100 μs. Truncated stimulation artifact at arrowhead is followed by evoked reflex (onset of monosynaptic component is indicated by downward arrow). In the presence of 5-HT, the reflex response is smaller in amplitude. Following washout the early reflex is potentiated and longer-latency reflex responses appear. B, change in reflex amplitude during and after 5-HT application. Reflex amplitude is expressed as a percentage of means of the 10 responses prior to 5-HT application. Data points were obtained from the integral of rectified reflexes for the period of 7–87 ms following stimulus onset. Bars represent standard errors of the mean of response (n = 9). C, example in an individual cord to demonstrate the ability of 5-HT to facilitate reflexes for several hours. For simplicity, the ordinate presents integral of reflex (mV ms) in relative units. D, reflex responses as presented in B but divided into early (7–20 ms) and late (20–87 ms) components. E, the monosynaptic reflex is facilitated. The figure presents the average reflex rectified and integrated in various media. LLRF is induced in the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist APV (compare waveform 2 to 4). The grey area highlights the 7–20 ms latency. Boxed inset identifies waveforms with drug applications. Records A–E are from ventral roots. F, evidence of 5-HT induced LLRF in the triceps surae. EMGs were recorded with a wire electrode while the cut L5 dorsal root was stimulated at threshold for reflex recruitment (70 μA, 100 μs). Following application of 5-HT the same stimulus evoked a larger reflex. Arrowhead indicates onset of truncated stimulus artifact. Scale bars in A and F are 20 ms.

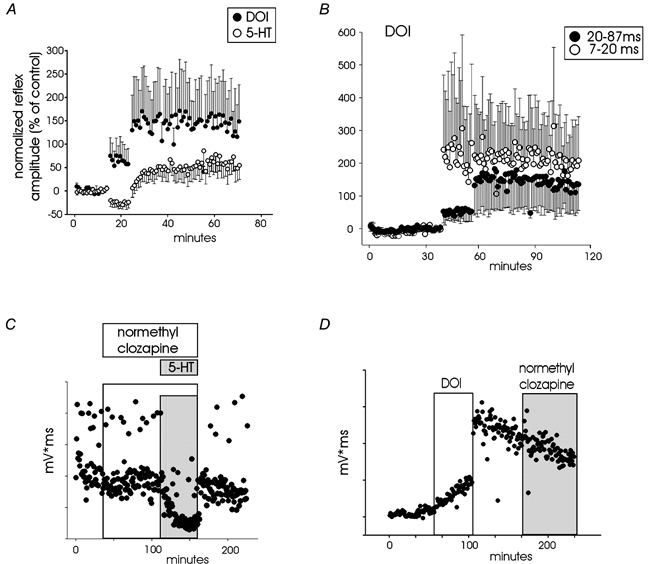

5-HT2C receptors are implicated in generating LLRF

In order to determine the 5-HT receptor subtype required for the induction of LLRF, pharmacological manipulations were performed and are summarized in Table 1. Analyses demonstrated that in the presence of the 5-HT2A/2C receptor antagonist normethyl clozapine, 5-HT failed to induce LLRF (Fig. 2A, top), while the 5-HT2 receptor agonist DOI alone was sufficient to induce LLRF (Fig. 2B, bottom). DOI, in the presence of the 5-HT2A receptor antagonist spiperone, still produced LLRF as did MK-212 alone, a selective 5-HT2C receptor agonist (not illustrated). Agonists selective for the 5-HT1A/1B, 5-HT2A or 5-HT7 receptors did not induce LLRF and antagonists selective for 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A and 5-HT7 receptors could not prevent LLRF induced by 5-HT (Table 1). That 5-HT itself induces LLRF only following washout indicates the potent inhibitory actions of other activated 5-HT receptors on the recruitment of spinal reflexes during its application. Presumably, the 5-HT2 receptor-mediated effects are unmasked following washout due to their uniquely long-lasting actions. The long-lasting actions of DOI do not seem to be due to incomplete washout as they are not outcompeted by a high concentration of a 5-HT2 antagonist, normethylclozapine (Fig. 2D).

Table 1.

Dissection of 5-HT receptor subtype responsible for generating LLRF of spinal reflexes

| LLRF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| after | ||||

| Agonist | Antagonist | washout | Conclusion | n |

| 5-HT | — | Yes | — | 13/14 |

| 5-CT (5-HT1A/1B,7) | — | No | Not 5-HT7 or 5-HT1A/1B | 2/2 |

| 8-OH-DPAT (5-HT1A,7) | — | No | Not 5-HT7 or 5-HT1A | 3/3 |

| DOI (5-HT2A/C) | — | Yes | 5-HT2A or 5-HT2C | 5/5 |

| 5-HT | Way-100635 (5-HT1A) | Yes | Not 5-HT1A | 2/2 |

| 5-HT | Normethyl clozapine (5-HT2A/C) | No | 5-HT2A or 5-HT2C | 3/3 |

| DOI (5-HT2A/C) | Spiperone (5-HT1A,2A) | Yes | 5-HT2C | 3/3 |

| MK-212 (5-HT2C) | — | Yes | 5-HT2C | 3/3 |

The two leftmost columns present 5-HT receptor agonist and/or antagonists applied with putative site of action in brackets. The middle column states whether LLRF was observed following drug washout, and the two rightmost columns provide an interpretation of the results followed by sample size, respectively.

Figure 2. 5-HT2 receptors mediate the LLRF.

A, potentiation following application of DOI (5-HT2 receptor agonist; 0.5 μm) and 5-HT (10 μm) is compared for two different groups of spinal cords for a latency of 7–87 ms (n = 9 for 5-HT, n = 8 for DOI). Data points represent the normalized integral of rectified reflexes expressed as a percentage ± s.e.m. of the last 10 responses prior to drug application. B, 500 nm DOI-induced reflex potentiation for the averaged responses from 8 spinal cords is separated into early (7–20) and late (20–87) reflex components. Note that potentiation of early reflex component is greater but more variable. C, reflex does not undergo 5-HT-induced potentiation when pre-incubated in normethyl clozapine (a 5-HT2 receptor antagonist; 1 μm). Open and grey boxes designate period of application of normethyl clozapine and 5-HT, respectively. D, the reflex facilitation produced following DOI application and its washout is retained with subsequent addition of a 5-HT2 receptor agonist (normethyl clozapine; 1 μm) demonstrating that reflex facilitation is not maintained by continued 5-HT2 receptor activation. Open and grey boxes designate period of application of DOI and normethyl clozapine, respectively.

Figure 2A compares the modulatory actions of the 5-HT2 receptor agonist DOI to 5-HT. In contrast to 5-HT, DOI was capable of increasing reflex amplitude during its application. In addition, following drug washout, DOI produced a greater facilitation than 5-HT. The stronger facilitatory actions observed with DOI are presumably due to its selective activation of signal transduction pathways known to increase spinal cord excitability (see Discussion, Common transduction mechanisms for central sensitization and LLRF). DOI also increased spontaneous motor activity. As with 5-HT, the short-latency reflexes underwent a greater relative facilitation (Fig. 2B).

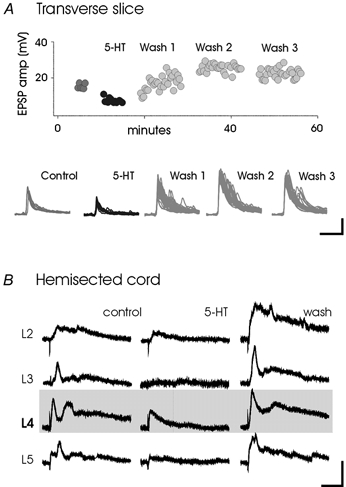

5-HT produces a long-lasting facilitation of sensory synaptic actions in spinal neurons

Neurons in the deep dorsal horn are modulated by 5-HT in a complex manner (e.g. Jankowska et al. 1997; Shay & Hochman 2001; Garraway & Hochman 2001). Patch recordings using thick transverse slices demonstrate that a subpopulation of neurons in the deep dorsal horn undergo a 5-HT-induced long-lasting facilitation of their primary afferent-evoked, largely monosynaptic (see Garraway & Hochman 2001) excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs; Fig. 3A). The isolated hemisected spinal cord preparation was then used to demonstrate that 5-HT also produces a long-lasting facilitation of sensory-evoked EPSPs converging from multiple spinal segments onto a subpopulation of similarly located neurons (Fig. 3B). This observed increase in EPSP amplitude in spinal neurons from distant spinal segments supports a 5-HT receptor-evoked increase in ‘receptive field size’. In all neurons, facilitated synaptic actions continued for the duration of the intracellular recording.

Figure 3. A subpopulation of deep dorsal horn neurons undergoes a long-lasting facilitation of EPSP amplitude.

A, dorsal roots were stimulated within a frequency range of 0.03–0.05 Hz. Facilitation occurred in 5/8 cells. B, 5-HT induces a long-lasting increase in multisegmental convergence. Electrodes were attached to homonymous (L4) and heteronymous roots (L2, L3, L5). Stimuli were delivered at 0.03 Hz. EPSP amplitude increases, following washout of 5-HT, were found in 7/19 cells and persisted for the duration of the recordings. Scale bars are 5 mV, 200 ms.

DISCUSSION

Summary

5-HT depressed reflex activity in the in vitro neonatal rat preparation (cp. Crick & Wallis, 1991). However, we observed a long-lasting facilitation of reflexes following 5-HT washout that could be maintained for several hours. Application of 5-HT receptor ligands demonstrated that LLRF occurred via 5-HT2C receptor activation. While longer latency components of the reflex were clearly facilitated, even the short-latency APV-insensitive reflex was facilitated. Some neurons within laminae III-VI also underwent long-lasting facilitation of afferent-evoked EPSPs. Thus, the increase in reflex gain coincides with an increase in sensory gain to a subpopulation of neurons. That excitatory input from multiple spinal segments is facilitated in individual neurons indicates that the synaptic facilitation is widespread. Some of these facilitated neurons may be spinal interneurons interposed in the polysynaptic reflex pathways that contribute to LLRF.

Common transduction mechanisms for central sensitization and LLRF

Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1/ mGluR5) are involved in the central sensitization that follows nociceptive stimuli (Fisher & Coderre, 1996). These receptors lead to an activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and there is a PKC dependence of central sensitization (Yashpal et al. 1995). PKC activation also potentiates NMDA receptor activity thereby facilitating NMDA receptor-dependent LTP (Ben-Ari et al. 1992).

The 5-HT2 class of serotonin receptors also activate PKC. Accordingly, 5-HT2 receptor activation with the selective agonist DOI produces a long-lasting facilitation of glutamatergic transmission in some dorsal horn neurons (Hori et al. 1996). Maintained increases in motoneuronal excitability (Wang & Dun, 1990; Yamazaki et al. 1992) and stretch reflexes (Miller et al. 1996) have also been reported with DOI. Finally, in adult rat, recent studies have demonstrated that some monoaminergic nuclei can facilitate nociceptive reflexes (Calejesan et al. 1998; Martin et al. 1999; Wei et al. 1999), in addition to their traditional antinociceptive role (Basbaum & Fields, 1984), suggesting that a serotonin-induced long-lasting reflex facilitation may be present in the adult CNS. Thus, descending serotonergic systems may activate spinal 5-HT2 receptors to recruit the same signal transduction pathways recruited by nociceptor afferents via activation of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors, and hence also contribute to central sensitization and flexion reflex LTP.

Conclusion

The observation that 5-HT can induce a long-lasting facilitation of spinal reflexes suggests that the brain can amplify the flexion reflex via serotonergic systems. Because the ‘sensitized’ interneurons serving flexion reflex LTP probably receive multi-sensory convergent input (Woolf et al. 1994), these interneurons are likely to correspond to those interposed in flexor-reflex afferent pathways (Baldissera et al. 1981). In conclusion, we provide the first demonstration of a descending transmitter that, when briefly applied, can produce a long-lasting amplification in reflex amplitude.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Christopher Reeve Paralysis Foundation and NIH grant NS40893.

References

- Anderson MF, Winterson BJ. Properties of peripherally induced persistent hindlimb flexion in rat: Involvement of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and capsaicin-sensitive afferents. Brain Research. 1995;678:140–150. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00177-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldissera F, Hultborn H, Illert M. Integration in spinal neuronal systems. In: Brooks VB, editor. Handbook of Physiology, section 1, The Nervous System Motor Control. II. Bethesda MD USA: American Physiological Society; 1981. pp. 509–595. [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Endogenous pain control systems: brainstem spinal pathways and endorphin circuitry. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1984;7:309–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y, Aniksztejn L, Bregestovski P. Protein kinase C modulation of NMDA currents: An important link for LTP induction. Trends in Neurosciences. 1992;15:333–339. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90049-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calejesan AA, Ch'ang MH, Zhuo M. Spinal serotonergic receptors mediate facilitation of a nociceptive reflex by subcutaneous formalin injection into the hindpaw in rats. Brain Research. 1998;798:46–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coderre TJ, Katz J, Vaccarino AL, Melzack R. Contribution of central neuroplasticity to pathological pain: review of clinical and experimental evidence. Pain. 1993;52:259–285. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90161-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick H, Wallis DI. Inhibition of reflex responses of neonate rat lumbar spinal cord by 5-hydroxytryptamine. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1991;103:1769–1775. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb09861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkovic RG, Prokowich LJ. d-2-Amino-5-phosphonovalerate, an NMDA receptor antagonist, blocks induction of associative long-term potentiation of the flexion reflex in spinal cat. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;257:162–164. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher K, Coderre TJ. The contribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) to formalin-induced nociception. Pain. 1996;68:255–263. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraway SM, Hochman S. Serotonin increases the incidence of primary afferent-evoked long-term depression in rat deep dorsal horn neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;85:1864–1872. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozariu M, Bragard D, Willer JC, Le-Bars D. Temporal summation of C-fiber afferent inputs: competition between facilitatory and inhibitory effects on C-fiber reflex in the rat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:3165–3179. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist B, Lundberg A. Differential supraspinal control of synaptic actions evoked by volleys in the flexion reflex afferents in alpha motoneurons. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1961;54:1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori Y, Endo K, Takahashi T. Long-lasting synaptic facilitation induced by serotonin in superficial dorsal horn neurones of the rat spinal cord. Journal of Physiology. 1996;492:867–876. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Hammar I, Djouhri L, Heden C, LackbergSzabo Z, Yin XK. Modulation of responses of four types of feline ascending tract neurons by serotonin and noradrenaline. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;9:1375–1387. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X-G, Sandkühler J. Long-term potentiation of C-fiber-evoked potentials in the rat spinal dorsal horn is prevented by spinal N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor blockage. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;191:43–46. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machacek DW, Garraway SM, Shay B, Hochman S. Serotonin induces a long-lasting reflex facilitation in isolated rat spinal cord. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1999;29:1918. [Google Scholar]

- Martin WJ, Gupta NK, Loo CM, Rohde DS, Basbaum AI. Differential effects of neurotoxic destruction of descending noradrenergic pathways on acute and persistent nociceptive processing. Pain. 1999;80:57–65. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF, Paul KD, Lee RH, Rymer WZ, Heckman CJ. Restoration of extensor excitability in the acute spinal cat by the 5-HT2 agonist DOI. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;75:620–628. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.2.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randic M, Jiang MC, Cerne R. Long-term potentiation and long-term depression of primary afferent neurotransmission in the rat spinal cord. Journal of Neuroscience. 1993;13:5228–5241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-12-05228.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouenborg J, Holmberg H, Weng H-R. Functional organization of the nociceptive withdrawal reflexes. II. Changes of excitability and receptive fields after spinalization in the rat. Experimental Brain Research. 1992;90:469–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00230929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay BL, Hochman S. Serotonin alters multisegmental convergence patterns in spinal cord deep dorsal horn and intermediate laminae neurons. Pain. 2001 doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00364-5. in the Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington CS. Flexion-reflex of the limb, crossed extension-reflex and reflex stepping and standing. Journal of Physiology. 1910;40:28–121. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1910.sp001362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen F, Tjølsen A, Hole K. AMPA and NMDA receptor-dependent spinal LTP after nociceptive tetanic stimulation. NeuroReport. 1998;9:1185–1190. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MY, Dun NJ. 5-Hydroxytryptamine responses in neonate rat motoneurones in vitro. Journal of Physiology. 1990;430:87–103. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Dubner R, Ren K. Nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis and nucleus raphe magnus in the brain stem exert opposite effects on behavioral hyperalgesia and spinal Fos protein expression after peripheral inflammation. Pain. 1999;80:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, McMahon SB. Injury-induced plasticity of the flexor reflex in chronic decerebrate rats. Neuroscience. 1985;16:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Shortland P, Sivilotti LG. Sensitization of high mechanothreshold superficial dorsal horn and flexor motor neurones following chemosensitive primary afferent activation. Pain. 1994;58:141–155. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Thompson SW. The induction and maintenance of central sensitization is dependent on N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor activation; implications for the treatment of post-injury pain hypersensitivity states. Pain. 1991;44:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90100-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf CJ, Wall PD. Relative effectiveness of C primary afferent fibers of different origins in evoking a prolonged facilitation of the flexor reflex in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1986;6:1433–1442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-05-01433.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki J, Fukuda H, Nagao T, Ono H. 5-HT2/5-HT1C receptor-mediated facilitatory action on unit activity of ventral horn cells in rat spinal cord slices. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;220:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90753-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashpal K, Pitcher GM, Parent A, Quirion R, Coderre TJ. Noxious thermal and chemical stimulation induce increases in 3H-phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate binding in spinal cord dorsal horn as well as persistent pain and hyperalgesia, which is reduced by inhibition of protein kinase C. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:3263–3272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03263.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo M, Gebhart GF. Characterization of descending facilitation and inhibition of spinal nociceptive transmission from the nuclei reticularis gigantocellularis and gigantocellularis pars alpha in the rat. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1992;67:1599–1614. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.6.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]