Abstract

The gating kinetics and functions of low threshold T-type current in cultured chromaffin cells from rats of 19–20 days gestation (E19–E20) were studied using the patch clamp technique. Exocytosis induced by calcium currents was monitored by the measurement of membrane capacitance and amperometry with a carbon fibre sensor.

In cells cultured for 1–4 days, the embryonic chromaffin cells were immunohistochemically identified by using polyclonal antibodies against dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) and syntaxin. The immuno-positive cells could be separated into three types, based on the recorded calcium current properties. Type I cells showed exclusively large low threshold T-type current, Type II cells showed only high voltage activated (HVA) calcium channel current and Type III cells showed both T-type and HVA currents. These cells represented 44 %, 46 % and 10 % of the total, respectively.

T-type current recorded in Type I cells became detectable at −50 mV, reached its maximum amplitude of 6.8 ± 1.2 pA pF−1 (n = 5) at −10 mV and reversed around +50 mV. The current was characterized by criss-crossing kinetics within the −50 to −30 mV voltage range and a slow deactivation (deactivation time constant, τd = 2 ms at −80 mV). The channel closing and inactivation process included both voltage-dependent and voltage-independent steps. The antihypertensive drug mibefradil (200 nm) reduced the current amplitude to about 65 % of control values. Ni2+ also blocked the current in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 25 μm.

T-type current in Type I cells did not induce exocytosis, while catecholamine secretion by exocytosis could be induced by HVA calcium current in both Type II and Type III cells. The failure to induce exocytosis by T-type current in Type I cells was not due to insufficient Ca2+ influx through the T-type calcium channel.

We suggest that T-type current is expressed in developing immature chromaffin cells. The T-type current is replaced progressively by HVA calcium current during pre- and post-natal development accompanying the functional maturation of the exocytosis mechanism.

In mature chromaffin cells, high voltage activated (HVA) calcium currents such as L-, N-, P/Q- and R-type currents induce catecholamine secretion by exocytosis (Augustine & Neher, 1992; Albillos et al. 1994, 2000; Artalejo et al. 1994; López et al. 1994a, b; Kim et al. 1995; Lomax et al. 1997; Lukyanetz & Neher, 1999). The contribution of each of these to the total current and also to exocytosis remains controversial. In cat chromaffin cells, there are L- and N-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, each one carrying 50 % of the Ca2+ current (Albillos et al. 1994), but L-type Ca2+ channels dominate exocytosis (López et al. 1994a). Bovine chromaffin cells possess not only L- (Artalejo et al. 1991) and N-type channels (Artalejo et al. 1992) but also P- (Mintz et al. 1992; Gandia et al. 1994) and Q-type channels (López et al. 1994b). Exocytosis is evoked essentially by L- and Q-type Ca2+ channel currents (Lomax et al. 1997). In cultured chromaffin cells from adult rat there are L-, N-, P- and Q-type Ca2+ channels and both L- and N-type Ca2+ currents have been shown to be involved during exocytosis (Kim et al. 1995). In slices of mouse adrenal gland, R-type current contributes 20 % of the total Ca2+ current and controls 50 % of rapid secretion (Albillos et al. 2000). Thus, it seems that not all classes of calcium channels are necessarily coupled with the same efficacy to exocytosis. In addition to these calcium channels, a recent study revealed the presence of α1G subunits generating low threshold T-type current in bovine chromaffin cells (García-Palomero et al. 2000). Electrophysiological studies demonstrated the presence of low threshold T-type calcium currents in only a small fraction of adult rat chromaffin cells (Hollins & Ikeda, 1996). It is not yet known, however, if low threshold T-type calcium currents contribute to the secretory mechanism.

Recently, we found that about 50 % of chromaffin cells from prenatal rat (E19–E20) show low threshold T-type transient calcium currents. The aim of the present study is (1) to characterize the biophysical and pharmacological properties of the T-type currents of embryonic chromaffin cells, (2) to determine if these embryonic chromaffin cells secrete catecholamine by the exocytosis mechanism and (3) to discover whether the T-type current of embryonic chromaffin cells contributes to the exocytosis mechanism.

METHODS

Cell culture

Adrenal glands were obtained from prenatal rats (E19–E20). Female Wistar rats (IFFACREDO, Lyon, France) were decapitated with a guillotine after being anaesthetized with CO2 or ether, as approved by the European Committee DGXI concerning animal experiments. The adrenal glands were removed from eight to ten prenatal rats and transferred to ice-cold phosphate buffer solution (PBS). After removing the capsule and cortex of the adrenal glands, the isolated medulla was cut into small pieces. Cells were dissociated by incubating them at 37 °C in 5 ml Ca2+-free digestion solution containing 0.2 % collagenase Type IA, 0.1 % hyaluronidase Type I-S and 0.02 % deoxyribonuclease Type I (Sigma, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France). After 30 min of tissue digestion, the enzymatic activity was stopped by adding 400 μl fetal bovine serum (Bio West, Nuaillé, France). The digested tissue was rinsed three times with PBS and triturated gently with a Pasteur pipette. The cells were then resuspended in 5 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 7.5 % fetal bovine serum, 50 i.u. ml−1 penicillin and 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin. Cells were plated onto 35 mm poly-l-lysine-coated dishes and were kept in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Experiments were performed on cells which had been in culture for 1–4 days. Cell culture media and reagents were purchased from Gibco BRL (Life Technologies, Cergy Pontoise, France).

Immunocytochemistry for dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) and syntaxin

Cultured chromaffin cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4 % p-formaldehyde in PBS for 20 min at room temperature. The cultures were then briefly washed three times with PBS followed by permeabilization with 0.05 % saponin and 0.2 % bovine serum albumin for 15 min at room temperature. They were then washed with PBS and incubated with rabbit anti-DBH and mouse anti-syntaxin polyclonal antibodies simultaneously for 40 min at room temperature. Bound primary antibodies were revealed by simultaneous incubation for 40 min with Cy 2-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG for syntaxin and Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Interchim, Asnières, France) for DBH. The dishes were then washed with PBS; we used glycerol as a mounting medium (Biovalley, Marne la vallée, France).

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole-cell current recording and voltage-clamp studies were performed with either an EPC-7 (List Electronics, Darmstadt, Germany) or an RK400 (Biologic, Claix, France) amplifier. Recording electrodes were pulled from microhaematocrit capillary tubes (Oxford Labware, MO, USA) with a Flaming-Brown P87 microelectrode puller (Sutter Instruments, CA, USA). Electrodes were coated with Sticky Wax (S. S. White, Gloucester, UK). Pipette resistance was typically 2–5 MΩ when filled with internal solution. The perforated-patch method (Rae et al. 1991) was also sometimes used for whole-cell current measurement and capacitance measurement. Current recordings were filtered at 1–3 kHz (Frequency Devices, MA, USA) and digitized using a Lab Master DMA board (Scientific Solutions, OH, USA). Data acquisition and analysis was performed with pCLAMP 6 (Axon Instruments, CA, USA) or a laboratory-made program (Acquis1).

Capacitance measurements

Membrane capacitance (Cm) changes associated with exocytosis were measured by the Lindau-Neher technique (Lindau & Neher, 1998) using a patch clamp amplifier (SWAM IIA, Ljubljana, Slovenia). Capacitance contributed by the recording apparatus and the pipette stray capacitance were compensated for using the fast capacitance compensation circuit prior to cell rupture. Under voltage clamp, the 1.6 kHz sinusoidal voltage of 30 mV peak-to-peak amplitude was summed to the holding potential of −80 mV. Current evoked by sinusoidal and pulse stimulation was compensated for using slow capacitance and series conductance compensation circuits. The phase angle was set by adjusting it until Cm changes had no projection on the conductance (G) trace.

Amperometry

Electrochemical detection of catecholamine release was performed as described previously (Kawagoe et al. 1991). Briefly, carbon fibre sensors were constructed by inserting single carbon fibres (of 10 μm diameter) into pulled glass capillaries. The carbon fibre electrode was then coated with a thin and uniform isolation film using the technique of anodic electrophoretic deposition of paint. The polymer film was then heat cured. Before each experiment, the electrodes were polished at a 45 deg angle on a micropipette bevelling wheel (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan). Electrochemical currents were amplified with a List EPC-5 patch-clamp amplifier. The potential of the carbon fibre electrode was set at +650 mV. The current signal was filtered at 10 kHz through a low pass filter, stored and analysed with an IBM PC-compatible computer.

Solutions

The standard extracellular solution contained (mm): 142 NaCl, 2.8 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 0.001 TTX (pH 7.4). Calcium channel currents were measured using an extracellular solution containing (mm): 137 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 BaCl2, 10 Hepes, 0.001 TTX (pH 7.4). Measurements of membrane capacity changes and amperometry experiments were done in the standard solution unless otherwise indicated. The pipette solution contained (mm): 145 caesium glutamate, 8 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 10 Hepes. For perforated patch whole-cell current recordings, the pipette was filled with the internal solution containing, in addition, amphotericin B (24 μg ml−1). The bath had a volume of 2 ml. Drug applications were performed with a modified microflow system (Krishtal & Pidoplichko, 1980). Mibefradil was the kind gift of F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Other chemicals were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise indicated. Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Experiments were carried out at room temperature (20–23 °C).

Confocal microscope observation

Images were acquired with a Carl Zeiss Axiovert (135 M-LSM supplied software and workstation). The 488 nm wavelength line of an argon-ion laser was used for excitation of the FM1–43 fluorophore. Images were collected using a ×40 oil-immersion objective (numerical aperture 1.3). The aperture setting of the confocal pinhole was maintained constant throughout each experiment.

Cultured cells plated on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips were mounted in a 1 ml-capacity experimental chamber and bathed for 5 min with 4 μm FM1-43 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) in either a standard physiological solution or in a 70 mm KCl solution (isosmotic reduction of Na+). Before observation, the cultured cells were washed with a dye-free solution.

RESULTS

Identification of chromaffin cells

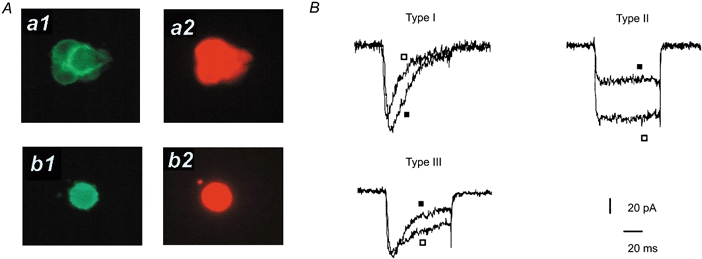

At birth, the adrenal medulla of the rat is composed of immature chromaffin cells, cortical cells, vascular elements and neuronal cells (Elfvin, 1967; Coupland & Tomlinson, 1989). Cultured adrenal medulla cells from prenatal rats (E19–E20) consist essentially of two groups of spherical cells, one group of large diameter (11–15 μm) and another of a smaller diameter (less than 10 μm). Under our culture conditions, the small cells stuck weakly to the bottom of the dish even after 2–3 days in culture, and detached easily when the solution was changed, while the large cells stuck rapidly after seeding. To identify the origin of these cells, double immunohistochemical staining was performed using polyclonal antibodies against DBH and syntaxin. Both DBH and syntaxin are present in chromaffin cells but not in corticoid cells. As expected, around 90 % of the cells in a dish were immuno-positive. These immuno-positive cells were typically of large size and could be easily identified under the microscope. Figure 1A illustrates typical immuno-positive cells in which syntaxin is located more intensely underneath the plasma membrane. These immuno-positive cells could be a mixture of medullary ganglion neurons and embryonic chromaffin cells. However, morphological observation (Coupland & Tomlinson, 1989) showed that the diameter of ganglion neurons is much larger than that of chromaffin cells. Furthermore, the ganglionic neurons represent only 5 % of medullary cells, and therefore contamination by neurons can be considered to be negligible.

Figure 1. Characteristics of embryonic chromaffin cells in culture.

A, immunohistochemical staining of fetal chromaffin cells with antibodies against syntaxin (a1 and b1) and against dopamine β-hydroxylase (a2 and b2): cell clusters (upper panels) and isolated single cells (lower panels). B, calcium channel currents recorded from the three subtypes of chromaffin cells. Superimposed currents were induced by pulses of 75 ms duration to −10 mV (▪) and +10 mV (□) driven from the holding potential of −80 mV.

Low threshold transient calcium channel current in chromaffin cells

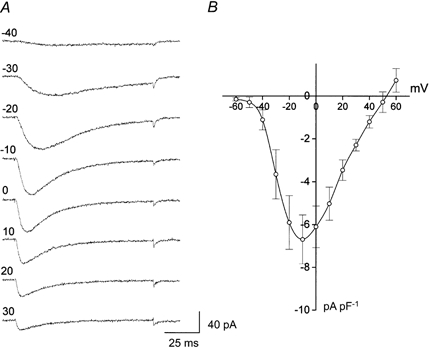

The immuno-positive cells could be further classified into three subclasses of cells following the criteria of their recorded calcium channel currents. Type I cells (44 % of cells studied) showed exclusively low threshold T-type current (Fig. 1B). Type II cells (46 % of cells) showed only HVA calcium channel current. Finally, Type III cells (10 % of cells) showed both T-type and HVA calcium channel currents. Fifteen days after birth, all chromaffin cells express HVA calcium channel currents (data not shown). Thus, Type I cells become almost absent after birth. The average membrane capacitance of Type I cells was 9.58 ± 3.2 pF (n = 15). There was no significant difference in average capacitance among Type I, Type II and Type III cells. T-type current kinetic analysis was performed on Type I cells. As shown in Fig. 2, the T-type current became detectable at around −50 mV, peaked near −10 mV with values of 6.8 ± 1.1 pA pF −1 (n = 5), and reversed at a membrane potential close to +50 mV (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. T-type current in embryonic chromaffin cells.

A, T-type currents were induced by test pulses of 80 ms duration to different potential levels (mV, indicated at left side of each trace), driven from the holding potential of −80 mV. B, current density-voltage relationship of T-type current.

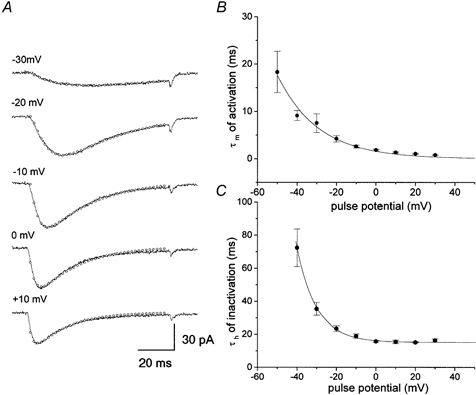

Current activation and inactivation kinetics

Current activation and inactivation kinetics were studied using a depolarizing pulse of 80 ms duration from −70 to +60 mV in 10 mV steps driven from a holding potential of −80 mV (Fig. 2). The recorded currents were well fitted with a sum of two exponentials (Fig. 3A). The current onset time constant (τm) was slow at near threshold voltage (18.2 ± 4.3 ms at −50 mV, n = 5) and was accelerated by increasing depolarization (0.7 ± 0.09 ms at +30 mV, n = 5). Thus, as shown in Fig. 3B, activation time constants were strongly voltage dependent. The time constant for the current decay (τh) was also voltage dependent in the range −40 to −10 mV. However, at more depolarizing potentials (> 0 mV), it became voltage independent with values of about 15 ms (Fig. 3C). Thus the decay phase consisted of a series of voltage-dependent and voltage-independent transition processes and the voltage-independent processes became rate limiting at extreme voltages.

Figure 3. Activation and inactivation time constant of T-type current.

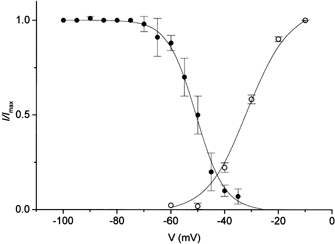

To determine the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation, we measured channel availability by applying a 30 s pre-pulse before a test pulse to −10 mV. The steady-state inactivation curve shows that inactivation occurred at sub-threshold potentials (around −70 mV) (Fig. 4). The averaged data could be fitted by a single Boltzmann equation with the parameter values V1/2 = −50.7 mV and k = 4.9 mV, where V1/2 is the midpoint and k is the slope factor. Figure 4 also compares the activation and steady-state inactivation curves. The activation curve was obtained from the ratio of peak current to test pulses at the maximum current intensity. The averaged experimental points were fitted by a Boltzmann equation with values of V1/2 = −31.7 mV, k = 6.3 mV. Activation and steady-state inactivation curves overlap in the voltage range −50 to −30 mV, where the channels were activated during the pre-pulse, but were not completely inactivated. The current at this voltage, referred to as the window current, is one of the properties characteristic of T-type current (Perez-Reyes, 1999).

Figure 4. Comparison of steady-state inactivation and activation of T-type current.

Averaged experimental points for activation (○) and for inactivation (•) were fitted by single Boltzmann equations (continuous lines).

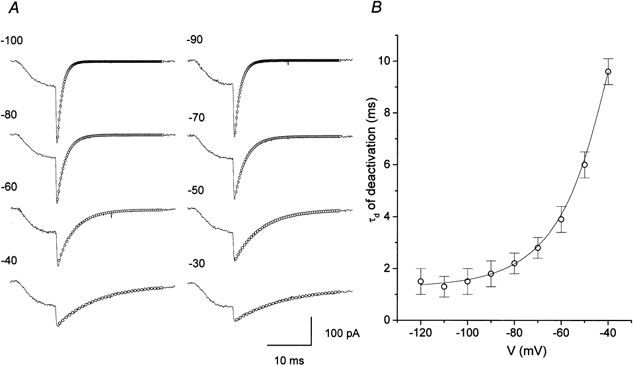

Deactivation of channels

Low voltage-activated T-type calcium channel current is also characterized by a slow deactivation process (Perez-Reyes, 1999). To examine the deactivation kinetics the rate of tail current was measured. A depolarizing test pulse of 10 ms duration, driven from a holding potential of −80 mV to −10 mV, was followed by a repolarizing potential between −120 and −40 mV. As shown in Fig. 5A, the tail current could be well fitted by a single exponential. A plot of the deactivation time constant (τd) as a function of the repolarizing potential (Fig. 5B) shows that the values of τd decreased when the repolarizing potential was shifted to negative potentials and became voltage independent (with τd = 1.5 ms) at potentials below −100 mV. The apparent saturation of τd is unlikely to result from the voltage error introduced by the large capacitative currents, because the series resistance was typically compensated by about 70 %. Thus, these results suggest the presence of a voltage-independent channel-closing process with a rate constant of around 666 s−1.

Figure 5. Voltage dependence of channel deactivation.

A, exponential fits (○) to tail currents elicited by repolarization potentials indicated at the left of each trace. Current (continuous lines) was activated by a 10 ms depolarization pulse to −10 mV from the holding potential −80 mV. B, plot of averaged time constant of deactivation (τd) vs. repolarizing potential.

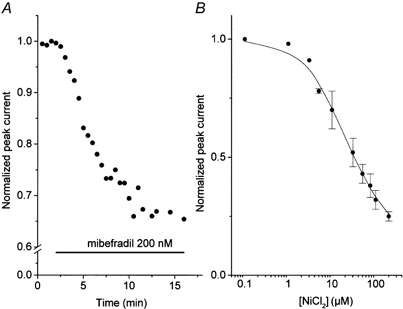

Blockade of T-type current by mibefradil and Ni2+

Mibefradil, an antihypertensive drug, has been reported to inhibit T-type calcium channel current in neuroblastoma cells (Bezprozvanny & Tsien, 1995; Randall & Tsien, 1997), sensory neurons (Todorovic & Lingle, 1998) and spinal motoneurons (Viana et al. 1997). Although the drug also blocks α1A, α1B, α1C and α1E calcium channel currents, higher concentrations are required (McDonough & Bean, 1998). In Fig. 6A an application of 200 nm mibefradil produced a progressive reduction of current amplitude and, at 11 min after drug application, the peak current amplitude became 66 % of control and stabilized despite the continuous application of the drug. In six cells studied, the peak current amplitude was reduced to 47.7 ± 14.7 % of control after application of mibefradil (200 nm). Nickel has also been used as a selective blocker of T-type current over the HVA calcium current (Todorovic & Lingle, 1998). Among the three subfamilies of T-type channels (α1G, α1H and α1I), the α1H channel current is more sensitive to low micromolar concentrations of nickel (IC50 = 13 μm) than α1G and α1I channel currents (Lee et al. 1999). To determine the dose dependence of inhibition, different concentrations of NiCl2 were applied sequentially and the peak current amplitude was measured every 10 s. The concentration at which half the current was blocked (IC50) was 25.3 ± 9.2 μm (n = 5) (Fig. 6B). This value is closer to that obtained for the α1H channel current recorded from stably transfected HEK 293 cells or oocytes (Lee et al. 1999), than to the IC50 of α1I or α1G channel currents.

Figure 6. Inhibition of T-type calcium channel current by antagonists.

A, effect of mibefradil (200 nm) on normalized T-type current amplitude. Application of mibefradil is indicated by a horizontal bar. B, dose-response curve of Ni2+ on T-type currents. Averaged experimental points were fitted by the equation: y = (1 - D)/(1 + ([mibefradil]/IC50)n) +D, where D is the fraction of the drug-resistant current and n is a slope factor. Best fit of the mean value of the responses vs. concentration was obtained with the values: IC50 = 20.5 μm, D = 0.20, n = 0.9. In both cases, current was elicited by a depolarizing pulse to −10 mV from the −80 mV holding potential.

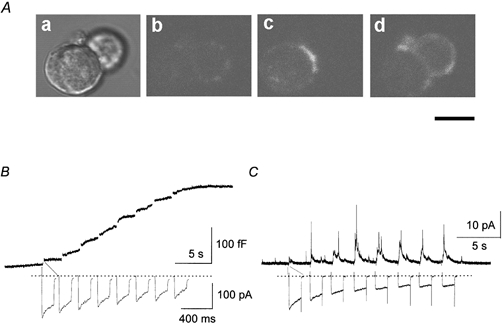

Exocytosis in embryonic chromaffin cells and HVA calcium channel currents

In mature chromaffin cells, HVA calcium currents induce catecholamine secretion (Artalejo et al. 1994; Lopez et al. 1994; Kim et al. 1995; Lomax et al. 1997; Lukayanetz & Neher, 1999). To determine whether membrane depolarization induces exocytosis in embryonic chromaffin cells, we first monitored the activity-dependent internalization of the fluorescent membrane probe FM1–43 by confocal microscopy. Figure 7A shows an increase in fluorescence intensity at the cell surface when the cells were depolarized with 70 mm KCl, suggesting that the presence of depolarization induced exocytosis. The presence of exocytosis was also examined by membrane capacitance measurements (Fig. 7B). These experiments were performed in Type II cells showing HVA calcium channel currents with the normal external solution containing 2 mm Ca2+. HVA calcium currents were elicited by a train of eight depolarizing pulses of 160 ms driven from a holding potential of −80 mV to +10 mV. Each calcium current provoked an increase in membrane capacitance close to 30–35 fF. HVA-induced exocytosis was also confirmed by amperometric detection of catecholamine release. In Fig. 7C the calcium currents generated by the same stimulus protocol produced a spike response in the amperometry current recording. These results indicate that the HVA calcium current of embryonic chromaffin cells induced secretion of catecholamine by the exocytosis mechanism, as in mature chromaffin cells.

Figure 7. Exocytosis in fetal chromaffin cells.

Aa, phase contrast micrograph of fetal chromaffin cells. Ab-Ad, confocal observation of activity-dependent internalization of FM1–43, before (Ab) and after (Ac, Ad) depolarization induced by 70 mm KCl. Ac and Ad were averaged from eight fluorescence images, obtained in two different positions along the z-axis. Scale bar represents 10 μm. B, increase in membrane capacitance induced by HVA calcium current. C, amperometric detection of catecholamine secretion induced by HVA calcium current. In both B and C, HVA calcium currents were evoked by a series of eight 160 ms test depolarization pulses from a holding potential of −80 mV to +10 mV.

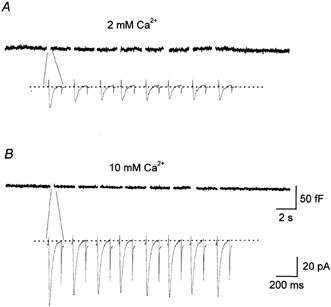

T-type current and capacity changes

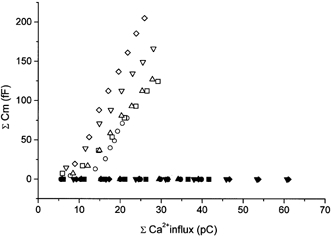

To investigate whether T-type current of Type I cells induces catecholamine secretion, simultaneous recordings of membrane capacitance changes and calcium current were performed. In normal external solution containing 2 mm CaCl2, the calcium current amplitude was −13.9 ± 0.9 pA (n = 8). A train of eight depolarizing pulses driven from −80 mV to −10 mV with a 2 s interval did not induce any membrane capacitance changes (Fig. 8A). It can be assumed that Ca2+ influx through the T-type calcium channel was not sufficient to induce exocytosis. By increasing the external Ca2+ concentration to 10 mm, the T-type current amplitude increased to −54.4 ± 1.3 pA (n = 8). This is almost in the same range as the current intensity recorded in 10 mm Ba2+ (Fig. 2B). A train of these currents, however, did not produce any capacitance changes (Fig. 8B). To determine if the absence of exocytosis in Type I cells was due to insufficient Ca2+ influx through the T-type calcium channel, the relationship between membrane capacitance and the amount of Ca2+ influx was compared in Type I and Type II cells. The amount of Ca2+ influx was estimated by measuring the charges carried by Ca2+ currents. Figure 9 illustrates a plot of cumulative membrane capacitance against total charge carried by Ca2+. In the cells which expressed HVA calcium current, an increase in capacitance could be detected when around 10 pC of charge was mobilized. In contrast, no membrane capacitance changes took place in the cells which expressed exclusively T-type current, even though the charge mobilized was as great as 60 pC. Thus, the absence of exocytosis in the latter cells seems not to be due to an insufficient Ca2+ influx.

Figure 8. Absence of membrane capacitance changes caused by T-type calcium current.

Simultaneous recording of T-type calcium current (lower traces) and membrane capacitance (upper traces) in two different external Ca2+ concentrations, 2 mm (A) and 10 mm (B). In both cases, T-type current was elicited by a series of eight depolarizing pulses of 120 ms driven from the holding potential of −80 mV to −10 mV.

Figure 9. Membrane capacitance increase and calcium currents.

Cumulative membrane capacitance increases (ordinate) were plotted against total charge (abscissa) carried by HVA calcium currents obtained from Type II cells (n = 5, open symbols) and T-type currents recorded from Type I cells (n = 5, filled symbols). The different symbols represent recordings obtained from different cells.

DISCUSSION

The gating kinetics of HVA calcium currents and the contribution of these currents to exocytosis have both been well documented in mature chromaffin cells (Augustine & Neher, 1992; Artalejo et al. 1994; López et al. 1994a, b; Kim et al. 1995; Lomax et al. 1997; Lukyanetz & Neher, 1999). In contrast, there have been few studies of this kind in embryonic chromaffin cells.

The adrenal chromaffin cells are generated from the neural crest, as are sympathetic neurons. In the case of the rat, the sympatho-adrenal cells begin to migrate from the neural crest around day E15 (Souto & Mariani, 1996). At 16–17 days of gestation, the primitive sympathetic cells arrive on mesoderm-derived adrenal cortical primordium and penetrate into the cortical cell layers. The chromoblast cells aggregate in the centre of the adrenal medulla. During this migration, noradrenergic sympatho-adrenal precursor cells differentiate to adrenal chromaffin cells (Souto & Mariani, 1996). At the end of gestation, the embryonic chromaffin cells express all catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes, as well as the presynaptic proteins that are involved in exocytosis (Hepp et al. 2000). Our immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the majority of cultured cells from the adrenal medulla of prenatal rats (E19–E20) show the presence of both DBH and syntaxin, suggesting very low contamination with other types of cells, such as the adrenal cortex cells. It is possible that the immuno-positive cells may also include ganglion neurons. However, morphological observation shows that neuronal cells are much larger in diameter than chromaffin cells and that they represent only a small percentage of medullary cells (Coupland & Tomlinson, 1989). Thus, we consider that the major proportion of the cells studied were embryonic chromaffin cells. Approximately 50 % of the cells showed low threshold transient current. This current possessed gating properties typical of the T-type current: (1) activating at low potential (around −50 mV), (2) being resistant to run down, (3) having low sensitivity to classical calcium channel toxins, (4) showing rapid inactivation and (5) showing slow deactivation. Furthermore, the recorded current shows a typical window current at a voltage range between −50 and −30 mV. Recent studies revealed that there are at least three subtypes of calcium channel α1 subunits (α1G, α1H and α1I), which are responsible for the generation of T-type current. Biophysical analysis of cloned channels expressed in oocytes and in the human kidney cell line HEK 293 demonstrated that α1G and α1H channel currents have very similar biophysical properties, while α1I calcium channel currents have significantly different gating properties (Perez-Reyes, 1999; Klöckner et al. 1999). For instance, α1I channels open at more depolarizing potentials, the kinetics of activation and inactivation are dramatically slower and steady-state inactivation occurs at a higher potential than in other subtypes of T-type currents. T-type current recorded in embryonic chromaffin cells has more rapid activation (2.6 ± 0.3 ms at −10 mV, n = 6) and deactivation time constants (2.2 ± 0.4 ms at −80 mV, n = 6) than α1I calcium channels. These channel gating properties are closer to those of α1H and α1G than to those of α1I. Concerning the difference between α1G and α1H, it has been demonstrated that α1H channel currents are much more sensitive to Ni2+ (IC50 = 13 μm) than α1G currents, in which the IC50 value is approximately 250 μm. The T-type current recorded in embryonic chromaffin cells was blocked by Ni2+ in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 of 25 μm. Taking these results together, the T-type current we recorded from embryonic chromaffin cells shares properties with the α1H channel.

It has been demonstrated that, in mature chromaffin cells, exocytosis can be produced by different types of HVA calcium currents (Artalejo et al. 1994; Kim et al. 1995; Gandía et al. 1998). The present results showed that, in embryonic chromaffin cells, HVA currents of Type II cells induced an increase in membrane capacitance and, furthermore, amperometry measurements detected catecholamine secretion produced by these currents. In contrast, the low threshold T-type current expressed in Type I cells failed to provoke exocytosis. As depicted in Fig. 9, this failure to induce exocytosis could not be attributed to insufficient Ca2+ influx. It may be possible, however, that the same amount of Ca2+ influx into Type I and Type II cells does not produce the same variation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, because of the different intracellular Ca2+ buffering capacities of these cells. For instance, Ca2+ entering through the T-type calcium channel of Type I cells could be rapidly buffered so that intracellular Ca2+ concentration does not attain the threshold needed to trigger exocytosis. An alternative interpretation of the present result is that Type I cells are functionally immature and the exocytosis mechanism is not functional yet. It is likely that embryonic chromaffin cells at E19–E20 are made up of different cell populations. The heterogeneity of populations of embryonic chromaffin cells has also been demonstrated by morphological observations (Coupland & Tomlinson, 1989; Seidl & Unsicker, 1989). We propose, therefore, that T-type current may be expressed in immature cells. During prenatal and postnatal development, T-type current may be replaced by HVA calcium current, a process accompanied by maturation of the exocytosis mechanism. It is frequently observed (Gonoi & Hasegawa, 1988; Thompson & Wong, 1991; Shimahara & Bournaud, 1991; Chameau et al. 1999) that the low threshold T-type current is expressed in embryonic or non-differentiated cells, and that this current is replaced by HVA calcium current as cell maturation or differentiation takes place.

The physiological function of T-type current in chromaffin cells is not known. One of the particular properties of T-type current is its criss-crossing kinetics. This channel activity may contribute to oscillations of the resting membrane potential and to the generation of spontaneous spike discharges. It has been reported that calcium oscillation plays an important role in the process of differentiation (Holliday & Spitzer, 1990). The present results suggest that T-type current is mainly present in developing cells. We could speculate, therefore, that calcium influx through T-type channels of embryonic chromaffin cells may be involved in the maintenance of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, which is an essential factor for cell differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr F. Darchen of the Institute Physico-Chimique for the kind gift of antibodies. The present study was partially supported by a CONICYT-INSERM exchange programme.

References

- Albillos A, Artalejo AR, López MG, Gandía L, García AG, Carbone E. Calcium channel subtypes in cat chromaffin cells. Journal of Physiology. 1994;477:197–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albillos A, Neher E, Moser T. R-type Ca2+ channels are coupled to the rapid component of secretion in mouse adrenal slice chromaffin cells. Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:8323–8330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08323.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artalejo CR, Adams ME, Fox AP. Three types of Ca2+ channel trigger secretion with different efficacies in chromaffin cells. Nature. 1994;367:72–76. doi: 10.1038/367072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artalejo CR, Dahmer MK, Perlman RL, Fox AP. Two types of Ca2+ currents are found in bovine chromaffin cells: facilitation is due to the recruitment of one type. Journal of Physiology. 1991;432:681–707. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artalejo CR, Perlman RL, Fox AP. ω-conotoxin GVIA blocks a Ca2+ current in chromaffin cells that is not of the “classic” N type. Neuron. 1992;8:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90110-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Neher E. Calcium requirements for secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. Journal of Physiology. 1992;450:247–271. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Tsien RW. Voltage-dependent blockade of diverse types of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes by the Ca2+ channel antagonist mibefradil (Ro 40–5967) Molecular Pharmacology. 1995;48:540–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chameau P, Lucas P, Melliti K, Bournaud R, Shimahara T. Development of multiple calcium channel types in cultured mouse hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;90:383–388. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00457-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland RE, Tomlinson A. The development and maturation of adrenal medullary chromaffin cells of the rat in vivo: a descriptive and quantitative study. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 1989;7:419–438. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(89)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfvin LG. The development of the secretory granules in the rat adrenal medulla. Journal of Ultrastructure Research. 1967;17:45–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(67)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandía L, Albillos A, García AG. Bovine chromaffin cells possess FTX-sensitive calcium channels. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1994;194:671–676. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandía L, Mayorgas I, Michelena P, Cuchillo I, De Pascual R, Abad F, Novalbos JM, Larrañaga E, García AG. Human adrenal chromaffin cell calcium channels: drastic current facilitation in cell clusters, but not in isolated cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1998;436:696–704. doi: 10.1007/s004240050691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Palomero E, Cuchillo-Ibáñez I, García AG, Renart J, Albillos A, Montiel C. Greater diversity than previously thought of chromaffin cell Ca2+ channels, derived from mRNA identification studies. FEBS Letters. 2000;481:235–239. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01984-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonoi T, Hasegawa S. Post-natal disappearance of transient calcium channels in mouse skeletal muscle: effects of denervation and culture. Journal of Physiology. 1988;401:617–637. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepp R, Grant NJ, Aunis D, Langley K. SNAP-25 regulation during adrenal gland development: Comparison with differentiation markers and other SNAREs. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2000;421:533–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday J, Spitzer NC. Spontaneous calcium influx and its roles in differentiation of spinal neurons in culture. Developmental Biology. 1990;141:13–23. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollins B, Ikeda SR. Inward currents underlying action potentials in rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:1195–1211. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoe KT, Jankowski JA, Wightman RM. Etched carbon-fiber electrodes as amperometric detectors of catecholamine secretion from isolated biological cells. Analytical Chemistry. 1991;63:1589–1594. doi: 10.1021/ac00015a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Lim W, Kim J. Contribution of L- and N-type calcium currents to exocytosis in rat adrenal medullary chromaffin cells. Brain Research. 1995;675:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner U, Lee J-H, Cribbs LL, Daud A, Hescheler J, Pereverzev A, Perez-Reyes E, Schneider T. Comparison of the Ca2+ currents induced by expression of three cloned α1 subunits, α1G, α1H and α1I, of low-voltage-activated T-type Ca2+ channels. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:4171–4178. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishtal OA, Pidoplichko VI. A receptor for protons in the nerve cell membrane. Neuroscience. 1980;5:2325–2327. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-H, Gomora JC, Cribbs LL, Perez-Reyes E. Nickel block of three cloned T-type calcium channels: low concentrations selectively block α1H. Biophysical Journal. 1999;77:3034–3042. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau M, Neher E. Patch-clamp techniques for time-resolved capacitance measurements in single cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1988;411:137–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00582306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomax RB, Michelena P, Nunez L, García-Sancho J, García AG, Montiel C. Different contributions of L- and Q-type Ca2+ channels to Ca2+ signals and secretion in chromaffin cells subtypes. American Journal of Physiology. 1997;272:C476–484. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López MG, Albillos A, De la Fuente MT, Borges R, Gandía L, Carbone E, García AG, Artalejo AR. Localized L-type calcium channels control exocytosis in cat chromaffin cells. Pflügers Archiv. 1994a;427:348–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00374544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López MG, Villarroya M, Lara B, Martinez Sierra R, Albillos A, García AG, Gandía L. Q- and L-type Ca2+ channels dominate the control of secretion in bovine chromaffin cells. FEBS Letters. 1994b;349:331–337. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanetz EA, Neher E. Different types of calcium channels and secretion from bovine chromaffin cells. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;11:2865–2873. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough SI, Bean BP. Mibefradil inhibition of T-type calcium channels in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Molecular Pharmacology. 1998;54:1080–1087. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Adams ME, Bean BP. P-type calcium channels in rat central and peripheral neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. Three for T: molecular analysis of the low voltage-activated calcium channel family, CMLS. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 1999;56:660–669. doi: 10.1007/s000180050460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall AD, Tsien RW. Contrasting biophysical and pharmacological properties of T-type and R-type calcium channels. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:879–893. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae J, Cooper K, Gates P, Watsky M. Low access resistance perforated patch recordings using amphotericin B. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1991;37:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90017-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidl K, Unsicker K. The determination of the adrenal medullary cell fate during embryogenesis. Developmental Biology. 1989;136:481–490. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimahara T, Bournaud R. Barium currents in developing skeletal muscle cells of normal and mutant mice foetuses with ‘muscular dysgenesis’. Cell Calcium. 1991;12:727–733. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(91)90041-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souto M, Mariani ML. Immunochemical localization of chromaffin cells during the embryogenic migration. Biocell. 1996;20:179–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SM, Wong RKS. Development of calcium current subtypes in isolated rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. Journal of Physiology. 1991;439:671–689. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic SM, Lingle CJ. Pharmacological properties of T-type Ca2+ current in adult rat sensory neurons: effects of anticonvulsant and anesthetic agents. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;79:240–252. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana F, Van den Bosch L, Missiaen L, Vandenberghe W, Droogmans G, Nilius B, Robberecht W. Mibefradil (Ro 40–5976) blocks multiple types of voltage-gated calcium channels in cultured rat spinal motoneurons. Cell Calcium. 1997;22:299–311. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(97)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]