Abstract

The aims of this study in the ovine fetus were to (1) characterise continuous changes in umbilical blood flow and vascular conductance during acute hypoxaemia and (2) determine the effects of nitric oxide blockade on umbilical blood flow and vascular conductance during normoxic and hypoxaemic conditions using a novel in vivo‘nitric oxide clamp’.

Under 1–2 % halothane anaesthesia, seven ovine fetuses were instrumented between 118 and 125 days of gestation (term is ca 145 days) with vascular and amniotic catheters and a flow probe around an umbilical artery. At least 5 days after surgery, all fetuses were subjected to a 3 h protocol: 1 h of normoxia, 1 h of hypoxaemia and 1 h of recovery during fetal i.v. infusion with saline or, 1-2 days later, during combined fetal treatment with the nitric oxide (NO) inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME, 100 mg kg−1) and the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (NP, 5.1 ± 2.0 μg kg−1 min−1, the ‘nitric oxide clamp’). Following the end of the 3 h experimental protocol, the infusion of NP was withdrawn to unmask any persisting effects of fetal treatment with l-NAME alone.

During acute hypoxaemia, the reduction in arterial partial pressure of O2 (Pa,O2) was similar in fetuses infused with saline or treated with the nitric oxide clamp. In all fetuses, acute hypoxaemia led to a progressive increase in mean arterial blood pressure and a fall in heart rate. In saline-infused fetuses, acute hypoxaemia led to a rapid, but transient, decrement in umbilical vascular conductance. Thereafter, umbilical vascular conductance was maintained and a significant increase in umbilical blood flow occurred, which remained elevated until the end of the hypoxaemic challenge. In contrast, while the initial decrement in umbilical vascular conductance was prevented in fetuses treated with the nitric oxide clamp, the increase in umbilical blood flow during hypoxaemia was similar to that in fetuses infused with saline. After the 1 h recovery period of the acute hypoxaemia protocol, withdrawal of the sodium nitroprusside infusion from fetuses undergoing the nitric oxide clamp led to a significant, but transient, hypertension and a sustained umbilical vasoconstriction.

In conclusion, the data reported in this study of unanaesthetised fetal sheep (1) show that minute-by-minute analyses of haemodynamic changes in the umbilical vascular bed reveal an initial decrease in umbilical vascular conductance at the onset of hypoxaemia followed by a sustained increase in umbilical blood flow for the duration of the hypoxaemic challenge, (2) confirm that the increase in umbilical blood flow after 15 min hypoxaemia is predominantly pressure driven, and (3) demonstrate that nitric oxide plays a major role in the maintenance of umbilical blood flow under basal, but not under acute hypoxaemic, conditions.

During adverse intrauterine conditions the fetus may, if necessity determines, elicit cardiovascular, endocrine and metabolic responses that permit continued survival throughout the period of adversity. For example, during an episode of acute hypoxaemia, a redistribution of the combined ventricular output occurs that shunts blood flow away from the periphery to specific circulations essential to fetal well-being, such as the adrenal, myocardial and cerebral vascular beds (Rudolph, 1984). However, when considering the umbilical-placental vascular response to hypoxaemia, the literature is scant and contradictory, reporting that umbilical blood flow is either maintained (Cohn et al. 1974; Rudolph, 1984), increased (Goodwin, 1968; Mann, 1970) or even reduced (Dilts et al. 1969) during the period of fetal oxygen deprivation. These contradictory reports are largely due to either point measurements of umbilical blood flow taken at varying periods following the onset of adverse intrauterine conditions, as with radioactive microspheres (Cohn et al. 1974; Rudolph, 1984), or measurement of umbilical flow in the exteriorised sheep fetus with additional effects of anaesthesia (Dilts et al. 1969). Hence, such controversial reports emphasise the need for investigation of continuous, direct measurement of umbilical blood flow during basal and stressful intrauterine conditions in the unanaesthetised sheep fetus prepared for long-term recording.

Similarly, while the physiological mechanisms mediating the vasomotor responses to the fetal adrenal, heart, brain and periphery during an episode of fetal stress have been well characterised (for reviews see Rudolph, 1984; Giussani et al. 1994), those mediating any haemodynamic changes in the umbilical vascular bed during adverse intrauterine conditions remain comparatively less well understood. It has been shown that the gas nitric oxide (NO), a by-product from the conversion of l-arginine to l-citrulline by NO synthase, contributes towards the maintenance of basal blood flow in almost all fetal vascular beds studied, including the umbilical (Chang et al. 1992; Chlorakos et al. 1998), cerebral (McCrabb & Harding, 1996), myocardial (Reller et al. 1995) and gastrointestinal (Fan et al. 1998), and in the femoral and carotid arteries (Green et al. 1996). Fewer studies have investigated the role of NO in mediating the haemodynamic response of specific circulations in the fetus during adverse intrauterine conditions, e.g. hypoxaemia (Reller et al. 1995; Green et al. 1996). No study, to date, has either measured umbilical blood flow continuously during an episode of acute hypoxaemia or investigated the role of NO in mediating haemodynamic changes in the umbilical vascular bed during hypoxaemia in the conscious fetus during late gestation.

Studies addressing the role of NO in the control of umbilical blood flow during basal conditions (Chang et al. 1992), or in circulations other than the umbilical vascular bed during acute hypoxaemia (Reller et al. 1995; Green et al. 1996), have blocked the synthesis of NO by fetal administration of either l-NAME alone or other competitive inhibitors of NO synthase. The administration of these compounds alone leads to marked and prolonged fetal hypertension, bradycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction (Chang et al. 1992; Green et al. 1996; Chlorakos et al. 1998), altering basal cardiovascular function in the fetus prior to the onset of a hypoxaemic challenge. Clearly, in order to investigate the influence of NO activity on fetal cardiovascular responses to acute hypoxaemia, basal cardiovascular function must be restored. Hence, the present study used the combination of fetal treatment with l-NAME to block de novo synthesis of NO, and the NO donor sodium nitroprusside to compensate for the tonic production of the gas, thereby maintaining basal cardiovascular function in the fetus.

Therefore, using direct measurement of umbilical blood flow in the unanaesthetised sheep fetus during late gestation, the aims of this investigation were to (i) characterise continuous changes in blood flow and vascular conductance in the umbilical circulation during an episode of acute hypoxaemia and (ii) determine the effects of NO blockade on umbilical blood flow and vascular conductance during normoxic and acute hypoxaemic conditions using a novel in vivo‘nitric oxide clamp’.

METHODS

Animals and surgery

Seven Welsh Mountain ewes (University of Cambridge) carrying singleton pregnancies of known gestational age were used in the study. All procedures were performed under the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. All food, but not water, was withdrawn from the animals for 24 h prior to surgery. Surgery was performed under strict aseptic conditions between 118 and 125 days of gestation (dGA; term is ca 145 dGA). Anaesthesia was induced with sodium thiopentone (20 mg kg−1i.v. Intraval Sodium; Rhone Mérieux, Dublin, Ireland) and maintained with 1-2 % halothane in 50:50 O2:N2O. In brief, catheters were inserted into the carotid artery (extended into the ascending aorta), jugular vein (extended into the superior vena cava), femoral artery (extended into the descending aorta), femoral vein (extended into the inferior vena cava) and amniotic cavity (for the recording of reference pressure). A transit time flow transducer (4RS, Transonic Inc., Ithaca, NY, USA) was placed around an umbilical artery within the fetal abdominal cavity as previously described in detail (Gardner et al. 2001) to measure mean unilateral umbilical blood flow. A Teflon catheter was placed in the maternal femoral artery and extended to the descending aorta. Antibiotics were administered to the fetus during surgery through the femoral vein (300 mg ampicillin; Penbritin, GlaxoSmithKline, Uxbridge, UK) and amniotic catheters (300 mg ampicillin). All catheters were filled with heparinised saline (80 i.u. heparin ml−1 in 0.9 % NaCl), plugged with brass pins and exteriorised, together with the flow probes, through an incision in the maternal flank to be housed in a pouch sutured to the maternal skin.

After surgery animals were housed in individual pens with access to hay and water ad libitum and were fed concentrates twice daily (100 g; Sheep Nuts no. 6; H & C Beart Ltd, Kings Lynn, UK). All ewes received antibiotics (0.20-0.25 mg kg−1 Depocillin i.m.; Mycofarm, Cambridge, UK) and analgesia (10-20 mg kg−1 oral phenylbutazone; Equipalozone Paste, Arnolds Veterinary Products Ltd, Shropshire, UK) immediately after surgery and daily for 3 days. Patency of fetal vascular catheters was maintained by a slow continuous infusion of heparinised saline (25 i.u. heparin ml−1 at 0.1 ml h−1 in 0.9 % NaCl) containing antibiotics (1 mg ml−1 benzylpenicillin; Crystapen, Schering-Plough, Animal Health Division, Welwyn Garden City, UK).

Induction of acute hypoxaemia and the nitric oxide clamp

At least 5 days after surgery, between 131 and 133 dGA, all fetuses (n = 7) were subjected to a 3 h experimental protocol consisting of 1 h of normoxia, 1 h of hypoxaemia and 1 h of recovery during fetal i.v. infusion with saline (0.9 % NaCl, at 0.25 ml min−1). Fetal hypoxaemia was induced by maternal inhalation hypoxia, reducing the maternal inspired O2 fraction (FI,O2) (9 % O2 in N2 with 2-3 % CO2), as previously described in detail (Giussani et al. 1993). In brief, a large, transparent, respiratory hood was placed over the ewe's head into which air was passed at a rate of ca 40 l min−1 for the first 1 h period. Following this, fetal hypoxaemia was induced by changing the concentrations of gases breathed by the ewe. The mixture was designed to reduce fetal carotid Pa,O2 to ca 13 mmHg. Following the 1 h period of hypoxaemia the ewe was returned to breathing air and recordings were made for a further 1 h period of recovery.

One or two days later, in five of the seven fetuses (the catheters could not be maintained patent in two animals), a bolus dose of l-NAME (NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, Sigma; 100 mg kg−1 bolus dissolved in 1 ml saline) was injected i.v. This was immediately followed by fetal i.v. infusion with the NO donor, NP (5.1 ± 2.0 μg kg−1 min−1, mean ± 1 s.d., infusion dissolved in saline; Sigma). Combined treatment of the fetus with l-NAME and NP prevented the vasoconstriction and hypertension associated with l-NAME treatment alone (Chang et al. 1992; Green et al. 1996), thereby maintaining basal cardiovascular function. In addition, fetal treatment with l-NAME and NP permitted blockade of the de novo synthesis of NO while compensating for the tonic production of the gas (the nitric oxide clamp). Under steady-state conditions during fetal i.v. treatment with the nitric oxide clamp, the 3 h experimental protocol (1 h of normoxia, 1 h of hypoxaemia and 1 h of recovery) was repeated. At the end of the protocol, the ewes and fetuses were humanely killed using a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbitone (200 mg kg−1 Pentoject; Animal Ltd, York, UK) and the positions of implanted catheters and flow probes were confirmed.

The bolus dose of l-NAME injected was derived from preliminary experiments in our laboratory where maximal fetal pressor and vasopressor responses were elicited by 100 mg kg−1l-NAME, with higher doses having no further pressor or vasopressor responses. The dose of NP infused (5.1 ± 2.0 μg kg−1 min−1, mean ± 1 s.d.) was determined in preliminary experiments as that necessary to return fetal cardiovascular variables back to baseline levels following l-NAME i.v. injection. In all of the present series of experiments, the estimated dose of NP for each fetus was sufficiently accurate to titrate the pressor and vasopressor effects of l-NAME i.v. injection, so that almost simultaneous treatment of the sheep fetus with l-NAME and NP avoided any deviation from baseline in any cardiovascular variable. Fetal weight during the experiment was estimated at 2 kg based upon previous studies in the laboratory and infusion doses presented have been retrospectively corrected according to fetal weight determined post mortem. The effectiveness of NO blockade by l-NAME throughout the 3 h acute hypoxaemia protocol was tested by withdrawal of the NP infusion at the end of the 1 h period after acute hypoxaemia, thereby unmasking the influence of fetal treatment with l-NAME alone and, in addition, permitting the investigation of tonic NO activity on all measured cardiovascular variables. In three of the fetuses, the order in which these fetuses received either i.v. infusion with saline or i.v. treatment with the nitric oxide clamp during acute hypoxaemia was randomised.

Data collection

During the acute hypoxaemia protocol, paired maternal and fetal blood samples (0.4 ml) were taken at 15 and 45 min of normoxia, after 15 and 45 min of hypoxaemia and after 15 and 45 min of recovery from hypoxaemia for monitoring arterial blood gases, percentage saturation of O2 in haemoglobin (% SatHb), haemoglobin concentration and acid-base status using an ABL5 blood gas analyser and OSM2 haemoximeter (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Measurements in maternal and fetal blood were corrected to 38 and 39.5 °C, respectively.

Cardiovascular analog signals for calibrated fetal mean arterial blood pressure, heart rate and unilateral umbilical blood flow were recorded continuously at 1 s intervals during the acute hypoxaemia protocol, and thereafter at 8 s intervals, using a data acquisition system. The signal was digitised, displayed and subsequently stored on disk by custom software (NI-DAQ, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) running on a PC. Umbilical blood flow was measured on a T201 or T206 blood flow meter (Transonic Inc.). Umbilical vascular conductance was calculated as umbilical blood flow divided by mean fetal perfusion pressure (arterial – venous pressure). Files were subsequently analysed using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets.

Statistical analyses

Values for all variables are expressed as means ±s.e.m. unless otherwise stated. All measured variables were first analysed for normality of distribution. All data obtained were parametric and assessed for statistical significance using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for the effect of time (baseline vs. early (first 15 min) or late (last 45 min) hypoxaemia or early/late recovery, or before and after withdrawal of sodium nitroprusside) and group (saline vs. nitric oxide clamp) followed by Tukey's post hoc test or Student's t test for unpaired data (Sigma-Stat; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For all comparisons, statistical significance was accepted when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Arterial blood gas and acid-base status during the experimental protocol

Maternal basal arterial blood gas and acid-base status were similar in ewes during fetal saline infusion or during treatment with the nitric oxide clamp (Table 1). During acute hypoxaemia, a similar fall in maternal Pa,O2 and % SatHb, and a similar increase in maternal arterial haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]a) occurred in both groups (Table 1). During recovery, all maternal variables returned to basal values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maternal arterial blood gas and acid-base status during the experiment

| Baseline | Hypoxaemia | Recovery | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N15 | N45 | H15 | H45 | R15 | R45 | ||

| pHa | Control | 7.49 ± 0.01 | 7.49 ± 0.01 | 7.49 ± 0.01 | 7.48 ± 0.01 | 7.52 ± 0.01 | 7.50 ± 0.01 |

| NO clamp | 7.50 ± 0.01 | 7.51 ± 0.01 | 7.50 ± 0.01 | 7.49 ± 0.01 | 7.52 ± 0.01 | 7.51 ± 0.01 | |

| Pa,CO2 | Control | 35.3 ± 0.7 | 36.1 ± 1.4 | 36.8 ± 1.0 | 38.4 ± 1.2 | 33.1 ± 0.4 | 34.4 ± 0.7 |

| (mmHg) | NO clamp | 35.8 ± 1.0 | 34.4 ± 0.9 | 35.8 ± 1.0 | 36.6 ± 0.2 | 32.4 ± 0.2 | 34.4 ± 0.9 |

| Pa,O2 | Control | 101.9 ± 3.4 | 108.0 ± 6.7 | 42.1 ± 1.8* | 35.8 ± 2.9* | 97.6 ± 3.4 | 100.6 ± 1.2 |

| mmHg) | NO clamp | 96.0 ± 4.4 | 98.6 ± 1.9 | 39.8 ± 2.9* | 38.0 ± 3.1* | 101.4 ± 2.7 | 92.2 ± 1.8 |

| SatHb | Control | 91.4 ± 1.6 | 91.4 ± 1.6 | 62.9 ± 4.3* | 56.9 ± 3.3* | 91.0 ± 0.9 | 92.0 ± 1.5 |

| (%) | NO clamp | 90.7 ± 1.3 | 91.3 ± 1.2 | 60.6 ± 2.9* | 58.4 ± 4.3* | 91.6 ± 1.0 | 91.3 ± 0.9 |

| [Hb] | Control | 8.1 ± 0.6 | 7.7 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.5* | 9.7 ± 0.6* | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 0.6 |

| g dl-1) | NO clamp | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 10.3 ± 0.9* | 10.5 ± 1.0* | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 8.7 ± 0.4 |

| ABE | Control | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 0.8 |

| (mequiv l-1) | NO clamp | 5.2 ± 0.9 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 4.8 ± 0.8 |

Values represent the means ±s.e.m. of arterial blood gases and acid-base status of ewes carrying fetuses infused with saline (control, n = 7) or fetuses undergoing combined treatment with L-NAME + NP (NO clamp, n = 5) during normoxic and hypoxaemic conditions. Maternal blood samples were collected at 15 min (N15) and 45 min (N45) of normoxia (baseline), at 15 min (H15) and 45 min (H45) of hypoxaemia and at 15 min (R15) and 45 min (R45) of recovery.

Significant differences (P < 0.05) for normoxia vs. hypoxaemia. pHa, arterial pH; Pa,CO2, arterial partial pressure of CO2; Pa,O2, arterial partial pressure of O2; SatHb (%), percentage oxygen saturation of Hb; ABE, acid/base excess.

Fetal basal arterial blood gas and acid-base status were similar in fetuses during infusion with saline or treatment with the nitric oxide clamp (Table 2). In all fetuses, acute hypoxaemia induced significant falls in pHa, Pa,O2, %SatHb and acid/base excess (ABE) and an increase in haemoglobin concenration, [Hb]a, without any alteration to Pa,CO2 from baseline (Table 2). The magnitude of these changes was similar during fetal infusion with saline or treatment with the nitric oxide clamp, with the exception of the increase in fetal [Hb]a, which failed to reach significance during fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp. During recovery, a reduction from baseline in Pa,CO2 occurred in both groups of fetuses and the falls in fetal pHa and ABE were maintained until the end of the recovery period (Table 2).

Table 2.

Fetal arterial blood gas and acid-base status during the experiment

| Baseline | Hypoxaemia | Recovery | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N15 | N45 | H15 | H45 | R15 | R45 | ||

| pHa | Control | 7.34 ± 0.01 | 7.34 ± 0.01 | 7.30 ± 0.02 | 7.26 ± 0.01* | 7.24 ± 0.02* | 7.27 ± 0.02* |

| NO clamp | 7.33 ± 0.01 | 7.36 ± 0.01 | 7.32 ± 0.01* | 7.22 ± 0.01* | 7.19 ± 0.02* | 7.25 ± 0.02* | |

| Pa,CO2 | Control | 52.7 ± 1.2 | 52.3 ± 1.8 | 53.2 ± 1.8 | 51.8 ± 1.7 | 48.7 ± 1.3* | 51.0 ± 1.5 |

| (mmHg) | NO clamp | 51.8 ± 0.8 | 49.0 ± 1.7 | 49.6 ± 2.3 | 52.5 ± 1.8 | 48.3 ± 0.7* | 48.6 ± 1.3 |

| Pa,O2 | Control | 24.5 ± 0.9 | 23.7 ± 0.8 | 13.0 ± 0.7* | 12.5 ± 0.3* | 26.2 ± 2.3 | 23.3 ± 1.6 |

| (mmHg) | NO clamp | 24.6 ± 1.3 | 22.8 ± 1.1 | 13.6 ± 0.4* | 14.6 ± 0.9* | 27.6 ± 1.7 | 24.3 ± 1.4 |

| SatHb | Control | 67.9 ± 3.3 | 65.8 ± 3.1 | 36.2 ± 4.6* | 34.3 ± 3.2* | 64.9 ± 3.3 | 61.6 ± 4.2 |

| (%) | NO clamp | 66.6 ± 3.1 | 66.4 ± 3.2 | 41.5 ± 1.6* | 39.3 ± 2.6* | 65.1 ± 2.4 | 65.4 ± 4.9 |

| [Hb] | Control | 8.9 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 0.5 | 9.9 ± 0.5* | 9.7 ± 0.* | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 8.8 ± 0.4 |

| (g dl-1) | NO clamp | 8.0 ± 0.6 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 0.6 | 7.7 ± 0.6 |

| ABE | Control | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | −0.5 ± 1.3* | −4.2 ± 1.7* | −6.7 ± 2.2* | −3.4 ± 1.9* |

| (mequiv l−1) | NO clamp | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | −1.2 ± 1.3 * | −5.6 ± 1.6* | −9.5 ± 1.9* | −6.0 ± 1.8 * |

Values represent the means ±s.e.m. of arterial blood gases and acid-base status of fetuses infused with saline (control, n = 7) or fetuses undergoing combined treatment with L-NAME + NP (NO clamp, n = 5) during normoxic and hypoxaemic conditions. Fetal blood samples were collected at 15 min (N15) and 45 min (N45) of normoxia (baseline), at 15 min (H15) and 45 min (H45) of hypoxaemia and at 15 min (R15) and 45 min (R45) of recovery.

Significant differences (P < 0.05) for normoxia vs. hypoxaemia or recovery.

Fetal cardiovascular responses to acute hypoxaemia during fetal infusion with saline or treatment with nitric oxide clamp

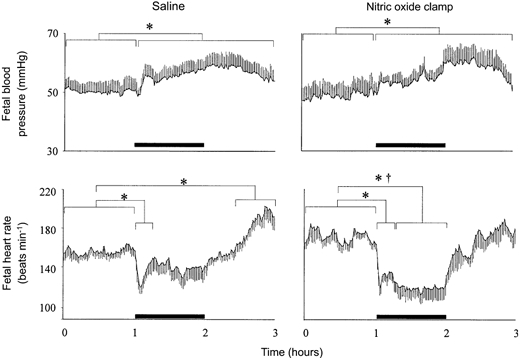

Basal fetal cardiovascular variables were similar during saline infusion or during fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). During acute hypoxaemia, there was a rapid fall in heart rate and a progressive increase in fetal arterial blood pressure, which remained elevated above baseline until the end of the recovery period, in both groups of fetuses (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Whilst fetal heart rate returned to basal values within 20 min of the onset of hypoxaemia during fetal infusion with saline, significant bradycardia persisted until the end of the hypoxaemic episode during fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). During recovery, significant tachycardia developed during fetal infusion with saline, but not during fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Effect of fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp on absolute changes in fetal blood pressure and fetal heart rate.

Absolute values for mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate during acute hypoxaemia in fetuses infused with saline (left panel, n = 7) or fetuses undergoing combined treatment with l-NAME + NP (nitric oxide clamp; right panel, n = 5). Fetal intravenous infusion with saline or combined fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp began before the normoxic hour (see Methods). Values are means ±s.e.m. of cardiovascular data averaged each minute during a baseline period (1 h normoxia), 1 h of hypoxaemia (bar) and 1 h of recovery. Significant differences are:*P < 0.05, baseline vs. early/late hypoxaemia or early/late recovery; †P < 0.05, control vs. nitric oxide clamp.

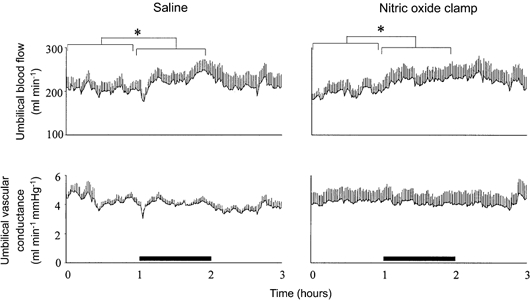

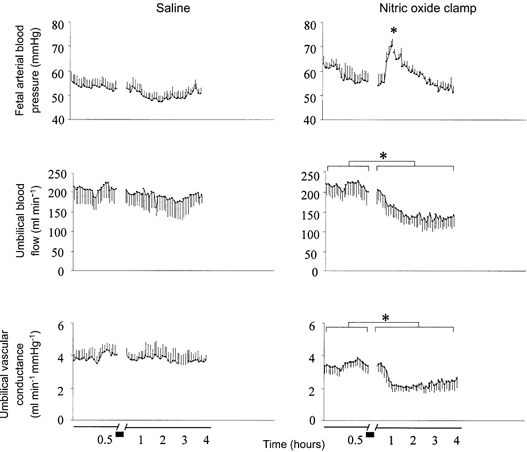

Figure 3. Effect of fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp on absolute changes in umbilical blood flow and vascular conductance.

Absolute values for mean umbilical blood flow and vascular conductance during acute hypoxaemia in fetuses infused with saline (left panel, n = 7) or fetuses undergoing combined treatment with l-NAME + NP (nitric oxide clamp; right panel, n = 5). Fetal intravenous infusion with saline or combined fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp began before the normoxic hour (see Methods). Values are means ±s.e.m. of cardiovascular data averaged each minute during a baseline period (1 h normoxia), 1 h of hypoxaemia (bar) and 1 h of recovery. * Significant differences (P < 0.05) for baseline vs. hypoxaemia.

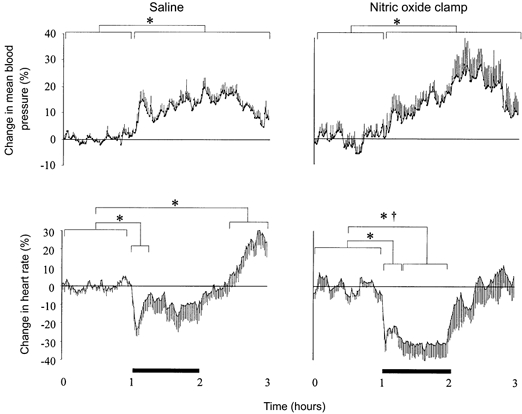

Figure 2. Effect of fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp on percentage changes in fetal blood pressure and fetal heart rate.

Percentage changes from baseline of mean arterial blood pressure and heart rate during acute hypoxaemia in fetuses infused with saline (left panel, n = 7) or fetuses undergoing combined treated with l-NAME + NP (nitric oxide clamp; right panel, n = 5). Fetal intravenous infusion with saline or combined fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp began before the normoxic hour (see Methods). Values are means ±s.e.m. of cardiovascular data averaged each minute during a baseline period (1 h normoxia), 1 h of hypoxaemia (bar) and 1 h of recovery. Significant differences are: *P < 0.05, baseline vs. early/late hypoxaemia or early/late recovery; †P < 0.05, control vs. nitric oxide clamp.

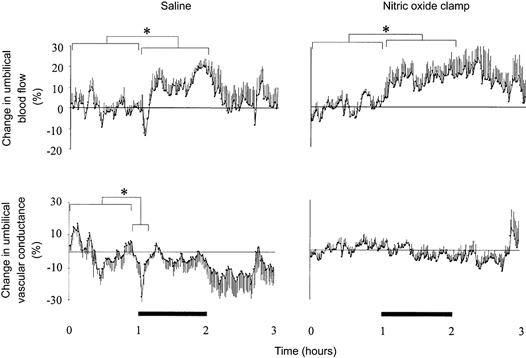

In saline-infused fetuses, acute hypoxaemia led to a rapid, but transient, decrement in umbilical vascular conductance (Fig. 4). Thereafter, umbilical vascular conductance was maintained at basal levels leading to parallel increases in umbilical blood flow and arterial blood pressure, which remained elevated until the end of the hypoxaemic challenge (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). In contrast, fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp prevented the initial decrement in umbilical vascular conductance (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Whilst the magnitude of the increases in umbilical blood flow and arterial blood pressure during hypoxaemia in fetuses treated with the nitric oxide clamp was not different from saline-infused fetuses, the increase in umbilical blood flow remained parallel to the increase in arterial blood pressure during the recovery period also, in contrast to saline infused fetuses (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Effect of fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp on percentage changes in umbilical blood flow and vascular conductance.

Percentage changes from baseline of mean umbilical blood flow and vascular conductance during acute hypoxaemia in fetuses infused with saline (left panel, n = 7) or fetuses undergoing combined treatment with l-NAME + NP (nitric oxide clamp; right panel, n = 5). Fetal intravenous infusion with saline or combined fetal treatment with the nitric oxide clamp began before the normoxic hour (see Methods). Values are means ±s.e.m. of cardiovascular data averaged each minute during a baseline period (1 h normoxia), 1 h of hypoxaemia (bar) and 1 h of recovery. * Significant differences (P < 0.05) for baseline vs. early hypoxaemia/hypoxaemia.

Fetal cardiovascular variables during fetal treatment with l-NAME alone

Following the end of the recovery period of the acute hypoxaemia protocol, withdrawal of saline infusion had no effect on any measured fetal cardiovascular variable (Fig. 5). In contrast, withdrawal of the sodium nitroprusside infusion in fetuses undergoing the nitric oxide clamp led to transient hypertension (from 55.7 ± 2.8 to 77.3 ± 2.1 mmHg) and sustained umbilical vasoconstriction (from 0.32 ± 0.05 to 0.60 ± 0.09 mmHg ml−1 min−1), leading to sustained falls in umbilical blood flow (from 205 ± 30 to 144 ± 17 ml min−1) and vascular conductance (from 3.45 ± 0.43 to 2.23 ± 0.41 ml min−1 mmHg−1, P < 0.05 in all cases; Fig. 4). The umbilical vasoconstriction persisted until at least 4 h after the withdrawal of the sodium nitroprusside infusion, which was the end of the recording period.

Figure 5. Effect of fetal treatment with l-NAME alone on fetal cardiovascular variables.

Mean fetal arterial blood pressure, umbilical blood flow and umbilical vascular conductance during the last 30 min of the recovery period of the acute hypoxaemia protocol (0.5 h) and after withdrawal of either saline in control fetuses (left panel, n = 7) or sodium nitroprusside infusion in fetuses undergoing combined treatment with l-NAME + NP (nitric oxide clamp; right panel, n = 5). Values are means ±s.e.m. of cardiovascular data averaged each minute up to 0.5 h and every 8 min thereafter. Short bar indicates period of withdrawal of saline or sodium nitroprusside. * Significant differences (P < 0.05) for baseline (0.5 h) vs. withdrawal of NP.

DISCUSSION

There has been long-standing clinical and physiological interest in the haemodynamic changes in the umbilical vascular bed during pregnancy, particularly in those complicated by adverse intrauterine conditions. Clinically, indirect measurements of umbilical blood flow in human pregnancy are obtained routinely by Doppler flow velocimetry. However, application of this technique in controlled experiments in pregnant sheep has shown that analysis of the umbilical vessel Doppler waveforms is complicated, particularly during fetal distress. For example, while Downing et al. (1991) and Tchirikov et al. (1998) reported an increase in the umbilical artery pulsatility index (PI), signifying an increase in umbilical vascular resistance, Muijers et al. (1990), Morrow et al. (1990) and van Huisseling et al. (1991) were unable to find any significant change in the umbilical artery PI during episodes of hypoxaemia. Similarly, using direct, spot measurement of umbilical blood flow with radioactive microspheres in the sheep fetus, Cohn et al. (1974) and Parer (1983) reported either an increase in umbilical vascular resistance or no change in umbilical blood flow during hypoxaemia. To avoid complications in the interpretation of either indirect indices or point measurements of umbilical blood flow, or of examination of changes in the umbilical vascular bed under the effects of anaesthesia, the present study used continuous measurement of umbilical blood flow by an implanted Transonic flow probe around an umbilical artery within the fetal abdomen in chronically instrumented, unanaesthetised fetal sheep preparations to characterise in detail the haemodynamic response of the umbilical vascular bed to a 1 h episode of acute hypoxaemia. Minute-by-minute analyses of the present data show that there is a transient decrease in umbilical vascular conductance at the onset of hypoxaemia. Shortly after, however, an increase in umbilical blood flow occurs that remains elevated for the duration of the hypoxaemic challenge. These data suggest that the increase in umbilical blood flow during acute hypoxaemia is primarily due to the well-described increase in fetal arterial blood pressure (see Giussani et al. 1994), since umbilical vascular resistance and conductance remained unchanged from baseline for the duration of the hypoxaemic challenge.

The transient fall in umbilical vascular conductance at the onset of hypoxaemia is interesting as it has been proposed that in the dually perfused human placental cotyledon preparation there is a hypoxia-mediated feto-placental vasoconstriction during hypoxaemia (Howard et al. 1987). In that in vitro study, the duration of hypoxaemia was 20 min and was, therefore, equivalent to the period during which a reduction in umbilical vascular conductance occurred during hypoxaemia in the present study (≈15 min). However, in vivo a number of vasoactive humoral agents are released into the fetal circulation (see Giussani et al. 1994) which are likely to influence the umbilico-placental vascular bed. Indeed, when the period of hypoxaemia is prolonged beyond 15-20 min, as in the present study, restoration of umbilical vascular conductance occurs, resulting in a pressure-driven increase in umbilical blood flow during hypoxaemia.

The second aim of the present study was to address the role of nitric oxide in mediating any changes in the umbilical vascular bed during normoxic and hypoxaemic conditions. Previous studies that have addressed the role of NO in the control of umbilical blood flow during basal conditions (Chang et al. 1992), or in circulations other than the umbilical vascular bed during the acute stress of hypoxaemia (Reller et al. 1995; Green et al. 1996), have blocked the synthesis of NO by fetal administration with either l-NAME alone or other competitive inhibitors of NO synthase. Administration of these compounds alone is known to induce marked cardiovascular changes including prolonged hypertension, bradycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction (Chang et al. 1992; Green et al. 1996; Chlorakos et al. 1998), altering fetal cardiovascular steady state prior to the onset of the hypoxaemic challenge. Clearly, in order to investigate the influence of NO activity on fetal cardiovascular responses to acute hypoxaemia, at the very least, basal conditions must be resumed following blockade of NO synthesis. In the present study a technique has been used to clamp the synthesis of NO whilst maintaining basal cardiovascular function in the sheep fetus. This technique has been previously validated by A. V. Edwards at the University of Cambridge and used to investigate the role of NO in mediating regional changes in blood flow in the sheep parotid gland (Hanna & Edwards, 1999) and in the calf adrenal gland (Bloom et al. 1987). The present study is the first to apply the NO clamp technique to address the role of NO in mediating haemodynamic changes in the umbilical vascular bed in sheep. Using this technique, the present data confirm that tonic NO synthesis has a major role in the maintenance of blood flow in a number of circulations, including the umbilical vascular bed (Chang et al. 1992; Reller et al. 1995; McCrabb & Harding, 1996; Green et al. 1996; Chlorakos et al. 1998; Fan et al. 1998), since withdrawal of the nitroprusside infusion in fetuses undergoing the nitric oxide clamp led to fetal hypertension and umbilical vasoconstriction. This finding also confirms that fetal treatment with a bolus injection of l-NAME successfully blocked NO synthesis until at least 4 h after the end of the experimental protocol.

In addition, the present study shows that fetal treatment with a combination of l-NAME and the NO donor sodium nitroprusside prevented the fall in umbilical vascular conductance, which occurred at the onset of hypoxaemia in fetuses that were infused with saline. This suggests that provision of basal NO prevents the initial hypoxaemia-induced umbilical vasoconstriction and that blockade of de novo NO synthesis during acute hypoxaemia has no major role in mediating the increase in umbilical blood flow observed during hypoxaemia. The implications of this finding are that provision of NO by infusion of sodium nitroprusside may mask the vasoconstrictor actions on the umbilical vascular bed of some agent released during hypoxaemia and/or that the hypoxaemia-induced initial umbilical vasoconstriction may be due to a reduction in the basal production of NO. In support of either possibility, two studies have reported that increased NO activity partially counteracts hypoxaemia-induced feto-placental vasoconstriction (Morrison et al. 2000) and that hypoxaemia-induced feto-placental vasoconstriction in human cotyledons in vitro is due to a reduction in the basal production of NO (Byrne et al. 1997). Furthermore, intravenous infusion of sodium nitroprusside into fetal sheep led to an ≈20 % fall in umbilical vascular resistance (Paulick et al. 1991). The combination of past and present data therefore suggests that the major part of the increase in umbilical blood flow during acute hypoxaemia is secondary to an increase in the perfusion pressure across the placental vascular bed and that failure to maintain umbilical vascular conductance at the onset of hypoxaemia may be due to a reduction in feto-placental NO synthesis.

It could be argued that the fall in umbilical vascular conductance that occurs soon after the onset of hypoxaemia is partly due to a fall in cardiac output, secondary to the marked bradycardia that occurs at this time. However, this possibility seems unlikely since the fall in umbilical vascular conductance after the onset of hypoxaemia was prevented in fetuses treated with the nitric oxide clamp, yet the bradycardia was of similar magnitude to that measured in saline-infused fetuses and, furthermore, persisted for the duration of the hypoxaemic episode. The persistent reduction in heart rate during hypoxaemia in fetuses treated with the nitric oxide clamp is interesting. Hypoxaemia-induced bradycardia is known to be triggered by a carotid chemoreflex (Giussani et al. 1993) and is mediated via increased vagal, and depressed sympathetic, outflow to the fetal heart (Parer, 1984; Giussani et al. 1993). The return of fetal heart rate to basal values during hypoxaemia has been attributed to enhanced β-adrenergic stimulation of the heart, secondary to increased release of plasma catecholamines into the fetal circulation (Court et al. 1984; Jones & Wei, 1985). Persistent bradycardia during acute hypoxaemia in fetuses treated with the nitric oxide clamp may therefore suggest an effect of blockade of NO during hypoxaemia on fetal chemoreflex function and/or the release and/or action of adrenal catecholamines. Although a recent report in the literature has suggested an inhibitory effect of endothelial NO in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat on cardiac baroreflex function (Paton et al. 2001), the influence of endothelial NO on chemoreflex function is unknown even in the adult. Similarly, although previous studies have reported both a stimulatory (O'Sullivan & Burgoyne, 1990; Uchiyama et al. 1994) and inhibitory (Nayagama et al. 1998) role for NO in mediating adrenal catecholamine release, plasma levels of catecholamines could not be determined in the present study.

In conclusion, the data reported in this study of unanaesthetised fetal sheep in late gestation, surgically prepared for long-term recording, (1) show that minute-by-minute analyses of haemodynamic changes in the umbilical vascular bed reveal an initial decrease in umbilical vascular conductance at the onset of hypoxaemia followed by a sustained increase in umbilical blood flow for the duration of the hypoxaemic challenge, (2) confirm that the increase in umbilical blood flow after 15 min hypoxaemia is predominantly pressure driven and (3) demonstrate that nitric oxide plays a major role in the maintenance of umbilical blood flow under basal, but not under acute hypoxaemic, conditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr Paul Hughes for his help during surgery, and Mrs Sue Nicholls and Miss Victoria Johnson for the routine care of the animals used in this study. This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation and the Physiological Laboratory, University of Cambridge.

References

- Bloom SR, Edwards AV, Jones CT. Adrenal cortical responses to vasoactive intestinal peptide in conscious hypophysectomised calves. Journal of Physiology. 1987;391:441–450. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Howard RB, Morrow RJ, Whiteley KJ, Admason SL. Role of the L-arginine nitric oxide pathway in hypoxic fetoplacental vasoconstriction. Placenta. 1997;18:627–634. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JK, Roman C, Heymann MA. Effect of endothelium-derived relaxing factor inhibition on the umbilical-placental circulation in fetal lambs in utero. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1992;166:727–734. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91704-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlorakos A, Langille BL, Adamson SL. Cardiovascular responses attenuate with repeated NO synthesis inhibition in conscious fetal sheep. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;274:H1472–1480. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.5.H1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn HE, Sacks EJ, Heymann MA, Rudolph AM. Cardiovascular responses to hypoxemia and acidemia in fetal lambs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1974;120:817–824. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(74)90587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court DJ, Parer JT, Block BS, Llanos AJ. Effects of beta-adrenergic blockade on blood flow distribution during hypoxaemia in fetal sheep. Journal of Developmental Physiology. 1984;6:349–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilts PV, Brinkman CR, Kirschbaum TH, Assali NS. Uterine and systemic haemodynamic interrelationships and their response to hypoxia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1969;103:138–157. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)34357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing GJ, Yarlagadda P, Maulik D. Effects of acute hypoxemia on umbilical arterial Doppler indices in a fetal ovine model. Early Human Development. 1991;25:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(91)90201-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan WQ, Smolich JJ, Wild J, Yu VY, Walker AM. Major vasodilator role for nitric oxide in the gastrointestinal circulation of the mid-gestation fetal lamb. Pediatric Research. 1998;44:344–350. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DS, Fletcher AJW, Fowden AL, Giussani DA. A novel method for controlled and reversible long term compression of the umbilical cord in fetal sheep. Journal of Physiology. 2001;535:217–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giussani DA, Spencer J, Hanson MA. Fetal cardiovascular reflex responses to hypoxaemia. Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review. 1994;6:17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Giussani DA, Spencer JAD, Moore PJ, Bennet L, Hanson MA. Afferent and efferent components of the cardiovascular reflex responses to acute hypoxia in term fetal sheep. Journal of Physiology. 1993;461:431–449. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin JW. The impact of the umbilical circulation on the fetus. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1968;100:461–471. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(15)33479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Bennet L, Hanson MA. The role of nitric oxide synthesis in cardiovascular responses to acute hypoxia in the late gestation sheep fetus. Journal of Physiology. 1996;497:271–277. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna SJ, Edwards AV. The role of nitric oxide in the control of protein secretion in the parotid gland of anaesthetized sheep. Experimental Physiology. 1999;83:533–544. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard RB, Hosokawa T, Maguire MH. Hypoxia-induced fetoplacental vasoconstriction in perfused human placental cotyledons. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1987;157:1261–1266. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CT, Wei G. Adrenal-medullary activity and cardiovascular control in the fetal sheep. In: Kunzel W, editor. Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1985. pp. 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- McCrabb GJ, Harding R. Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of cerebral blood flow in the ovine fetus. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1996;23:855–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann LI. Effects of hypoxia on umbilical circulation and fetal metabolism. American Journal of Physiology. 1970;218:1453–1458. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.5.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison S, Bewick T, Gardner DS, Fletcher AJW, Giussani DA. Enhanced nitric oxide activity partially offsets femoral vasoconstriction during acute hypoxaemia in fetal sheep during late gestation. Journal of Physiology. 2000;527 P, 48P. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow RJ, Adamson SL, Bull SB, Ritchie JW. Acute hypoxemia does not affect the umbilical artery flow velocity waveform in fetal sheep. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1990;75:590–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muijsers GJ, Hasaart TH, Ruissen CJ, Van Huisseling H, Peeters LLH, De Haan J. The response of the umbilical and femoral artery pulsatility indices in fetal sheep to progressively reduced uteroplacental blood flow. Journal of Developmental Physiology. 1990;13:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama T, Hosokawa A, Yoshida M, Suzuki-Kusaba M, Hisa H, Kimura T, Satoh S. Role of nitric oxide in adrenal catecholamine secretion in anesthetized dogs. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:R1075–1081. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.4.R1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan AJ, Burgoyne RD. Cyclic GMP regulates nicotine-induced secretion from cultured bovine adrenal chromaffin cells: effects of 8-bromo-cyclic GMP, atrial natriuretic peptide, and nitroprusside (nitric oxide) Journal of Neurochemistry. 1990;54:1805–1808. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parer JT. The influence of beta-adrenergic activity on fetal heart rate and the umbilical circulation during hypoxia in fetal sheep. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1983;147:592–597. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(83)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parer JT. The effect of atropine on fetal heart rate and oxygen consumption of the hypoxic fetus. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1984;148:1118–1122. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(84)90638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF, Deuchars J, Ahmad Z, Wong LF, Murphy D, Kasparov S. Adenoviral vector demonstrates that angiotensin II-induced depression of the cardiac baroreflex is mediated by endothelial nitric oxide synthase in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. Journal of Physiology. 2001;531:445–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0445i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulick RP, Meyers RL, Rudolph AM. Vascular responses of umbilical-placental circulation to vasodilators in fetal lambs. American Journal of Physiology. 1991;261:H9–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.1.H9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reller MD, Burson MA, Lohr JL, Morton MJ, Thornburg KL. Nitric oxide is an important determinant of coronary flow at rest and during hypoxemic stress in fetal lambs. American Journal of Physiology. 1995;269:H2074–2081. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.6.H2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AM. The fetal circulation and its response to stress. Journal of Developmental Physiology. 1984;6:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchirikov M, Eisermann K, Rybakowski C, Schroder HJ. Doppler ultrasound evaluation of ductus venosus blood flow during acute hypoxemia in fetal lambs. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;11:426–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.11060426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama Y, Morita K, Kitayama S, Suemitsu T, Minami N, Miyasako T, Dohi T. Possible involvement of nitric oxide in acetylcholine-induced increase of intracellular Ca2+ concentration and catecholamine release in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1994;65:73–77. doi: 10.1254/jjp.65.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Huisseling H, Hasaart TH, Muijsers GJ, De Haan J. Umbilical artery pulsatility index and placental vascular resistance during acute hypoxemia in fetal lambs. Gynecological and Obstetric Investigation. 1991;31:61–66. doi: 10.1159/000293104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]