Abstract

Rabbit ileal Na+-absorbing cell Na+-H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) was shown to exist in three pools in the brush border (BB), including a population in lipid rafts. Approximately 50 % of BB NHE3 was associated with Triton X-100-soluble fractions and the other ∼50 % with Triton X-100-insoluble fractions; ∼33 % of the detergent-insoluble NHE3 was present in cholesterol-enriched lipid microdomains (rafts).

The raft pool of NHE3 was involved in the stimulation of BB NHE3 activity with epidermal growth factor (EGF). Both EGF and clonidine treatments were associated with a rapid increase in the total amount of BB NHE3. This EGF- and clonidine-induced increase of BB NHE3 was associated with an increase in the raft pool of NHE3 and to a smaller extent with an increase in the total detergent-insoluble fraction, but there was no change in the detergent-soluble pool. In agreement with the rapid increase in the amount of NHE3 in the BB, EGF also caused a rapid stimulation of BB Na+-H+ exchange activity.

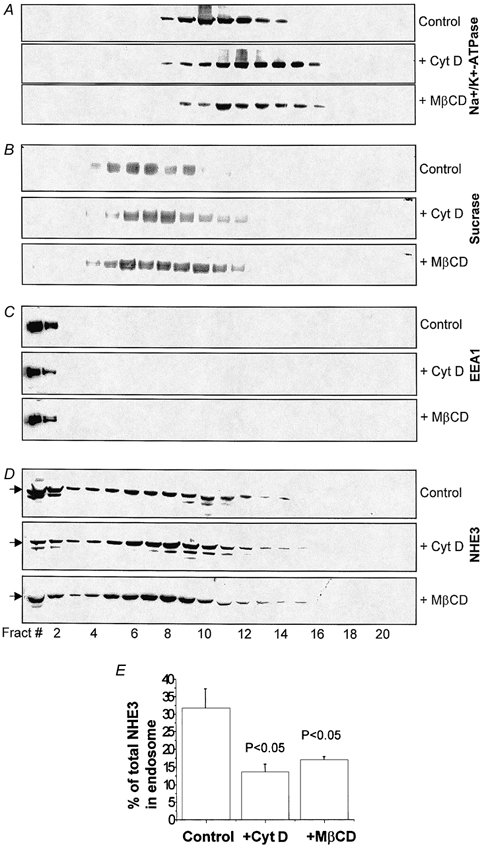

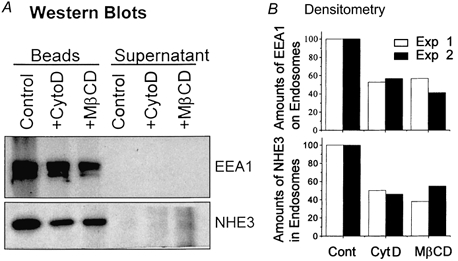

Disrupting rafts by removal of cholesterol with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) or destabilizing the actin cytoskeleton with cytochalasin D decreased the amount of NHE3 in early endosomes isolated by OptiPrep gradient fractionation. Specifically, NHE3 was shown to associate with endosomal vesicles immunoisolated by anti-EEA1 (early endosomal autoantigen 1) antibody-coated magnetic beads and the endosome-associated NHE3 was decreased by cytochalasin D and MβCD treatment.

We conclude that: (i) a pool of ileal BB NHE3 exists in lipid rafts; (ii) EGF and clonidine increase the amount of BB NHE3; (iii) lipid rafts and to a lesser extent, the cytoskeleton, but not the detergent-soluble NHE3 pool, are involved in the EGF- and clonidine-induced acute increase in amount of BB NHE3; (iv) lipid rafts and the actin cytoskeleton play important roles in the basal endocytosis of BB NHE3.

NHE3 is one of seven isoforms of Na+-H+ exchanger identified in eukaryotes (Wakabayashi et al. 1997; Orlowski & Grinstein, 1998; Donowitz & Tse, 2000). It is present in the brush border (BB) membranes of small intestine and colon, and the renal proximal tubule and thick ascending loop of Henle, and plays important roles in physiological intestinal and renal Na+ and HCO3− absorption (Hoogerwerf et al. 1996; Wakabayashi et al. 1997; Donowitz & Tse, 2000). Prolonged inhibition of intestinal NHE3 activity is an important mechanism in the pathophysiology of diarrhoeal diseases (Donowitz & Tse, 2000). Short-term regulation of NHE3 activity appears to be mainly through changes in its Vmax (Levine et al. 1993; Donowitz & Tse, 2000). Details of NHE3 regulation by protein kinases and growth factors is emerging with two different mechanisms identified. (1) Phosphorylation-dependent regulation, which requires the PDZ domain-containing proteins NHERF or E3KARP, at least partially occurs by direct phosphorylation of NHE3 (Kurashima et al. 1997; Zhao et al. 1999; Zizak et al. 1999). This regulation involves the linkage of NHE3 to actin by the BB cytoskeletal protein ezrin plus NHERF and E3KARP. This model has been based on studies in an epithelial cell model (OK cell) and a fibroblast cell line (PS120 cells) (Yun et al. 1998). It has not yet been established in small intestine, although NHE3 and NHERF or E3KARP co-precipitate in the rabbit ileal BB (X. Li & M. Donowitz, unpublished observations). (2) Regulation by trafficking of NHE3 on and off the apical membrane via changes in endocytosis and/or exocytosis (D'Souza et al. 1998; Janecki et al. 1998; Kurashima et al. 1999; Akhter et al. 2000; Janecki et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2000). Concerning endocytosis, NHE3 is internalized by a clathrin-mediated pathway, and NHE3 in rabbit ileal Na+-absorptive cells co-localizes with clathrin (Chow et al. 1999). Upon endocytosis, NHE3 is present on an intracellular compartment in epithelial cells consistent with endosomes (Biemesderfer et al. 1999). Recently cAMP inhibition of NHE3 was shown to involve both mechanisms in OK cells, with increased trafficking occurring with a delayed time course compared to phosphorylation-mediated inhibition (Yang et al. 2000).

Accumulating evidence indicates that lipid microdomains, also called lipid rafts, are involved in both types of regulatory mechanism that affect NHE3, local signalling and trafficking. Lipid rafts are defined as glycosphingolipid- and cholesterol-enriched microdomains that are insoluble in cold Triton X-100 (Simons & Ikonen, 1997; Keller & Simons, 1998; Lafont et al. 1998). Lipid rafts serve as restricted functional domains in which signalling complexes can form. In addition, in epithelial cells, lipid rafts appear to play important roles in apical protein targeting (Simons & Ikonen, 1997; Keller & Simons, 1998; Lafont et al. 1999), as well as endocytosis (Scheiffele et al. 1998). Lipid rafts are present on the apical surface of some epithelial cells (Maples et al. 1997; Lafont et al. 1998). They have been proposed to function as domains that interact with apically designated sorting vesicles.

Only recently were the first multi-membrane-spanning domain transport proteins shown to be present in rafts (Thiele et al. 1999; Martens et al. 2000). These were (1) the c subunit of the vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase), which is a proteolipid and forms the H+ translocation pathway (Finbow & Harrison, 1997; Thiele et al. 1999); and (2) Shaker-like K+ channels (Martens et al. 2000). Recent observations on the localization and regulation of NHE3 suggested that there might be a connection between lipid rafts and the regulation of NHE3: (1) one of the major regulatory mechanisms for NHE3 activity is via endocytosis and apical membrane recycling (D'Souza et al. 1998; Jenecki et al. 1998, 1999; Akhter et al. 2000; Janecki et al. 2000); and (2) EGF-stimulated NHE3 activity in rabbit ileum is dependent on increasing BB c-Src kinase activity (R. Patterson, X. Li, S. Khurana & M. Donowitz, unpublished observations), and c-Src is raft associated (Simons & Ikonen, 1997). In exploring this possibility, we now demonstrate that a component of ileal villus cell BB NHE3 is present in lipid rafts using a previously described definition of lipid rafts (Lafont et al. 1999), which is based on studies utilizing OptiPrep gradient floatation before and after cholesterol extraction of cold Triton X-100-insoluble NHE3. Moreover, such an association appears to be dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton. Furthermore, a functionally important role for this pool of NHE3 is suggested since (1) disruption of lipid rafts significantly decreases the basal endocytosis of NHE3; and (2) EGF and clonidine stimulation of BB NHE3 is associated with increased NHE3 in BB lipid raft fractions.

METHODS

Experimental animals and antibodies

Male New Zealand White rabbits weighing 2.5-5 kg were killed by an overdose of intravenous Nembutal (400 mg) and the ileum was then removed as described previously, in accordance with USA guidelines (Cohen et al. 1991). NHE3-specific polyclonal antibody (pAb) 1381 has previously been described (Hoogerwerf et al. 1996). pAbs against NHERF and E3KARP were as previously described (Yun et al. 1998). Anti-EEA1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) was purchased from Transduction Laboratories. pAb to β actin was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. pAb to ezrin was as previously described (Algrain et al. 1993) and was a generous gift from M. Arpin (Curie Institute, Paris, France). mAb to Na+-K+-ATPase was a generous gift from D. Fambrough (Johns Hopkins University). pAbs to syntaxin 3 and 4 were previously described (Fujita et al. 1998) and were a generous gift from Ann L. Hubbard (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine). pAb to intestinal alkaline phosphatase was as previously described (Zhang et al. 1996) and was a generous gift from D. Alpers (Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO, USA).

Materials

Clonidine, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), cytochalasin D and agents not specifically described were purchased from Sigma; EGF was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA); and lantrunculin A was from Calbiochem.

Preparation of ileum and treatment with cytochalasin D, latrunculin A or MβCD

Ileal segments (≈100 cm long) were removed immediately after the animals were killed, rinsed with ice-cold 0.9 % saline, and opened along the mesenteric border. The ileum was used either directly for BB preparation or for total membrane isolation. The ileum was cut into 10 cm segments and divided equally but randomly into three groups for different treatments. These were preincubated for 10 min at 37 °C, gassed with 95 % O2-5 % CO2 in Ringer-HCO3 buffer containing 10 mm glucose and 1 μm indomethacin, 1 mm PMSF, 0.1 mmN-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK), 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 phosphoramidon and 0.7 μg ml−1 pepstatin. In some experiments, cytochalasin D (10 μm), latrunculin A (10 μm), MβCD (10 mm) or an equal volume of Ringer-HCO3 buffer (control) was then added for an additional 20 min. The three groups of ileum were then chilled in ice-cold Petri dishes and processed in parallel. In other studies, EGF (200 ng ml−1)- and clonidine (3 μm)-treated, and control ilea were studied for an additional 1 min before BB isolation in parallel.

Ileal BB and basal lateral membrane (BLM) preparation

BB was isolated by double magnesium precipitation and differential centrifugation as described previously (Cohen et al. 1991). BLM was prepared as described from isolated ileal villus cells, which were obtained using everted ileum and a modification of the method of Weiser as described previously (Cohen et al. 1991). The purity of BB and BLM was compared using specific activities of sucrase and Na+-K+-ATPase, as previously described (Cohen et al. 1991), and gave comparable ×10-15 purifications relative to homogenate. These preparations have previously been characterized in detail and shown to be minimally contaminated with other organelles (Cohen et al. 1991).

Total membranes of lleal villus cells

Scraped ileal villus cells were homogenized with a Polytron in the same homogenization buffer as for the BB preparation. The homogenate was centrifuged at 5000 r.p.m. for 5 min at 4 °C twice to remove cell debris and nuclei. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 150 000 g for 60 min. The resulting total membrane pellet was resuspended at protein concentrations of 5-10 μg μl−1.

Detergent-soluble (DS) and -insoluble (DI) fractions of BB

Ileal BBs were mixed with 50 mm Mes buffer (1/5 v/v), pH 6.4, containing 60 mm NaCl, 3 mm EGTA, 5 mm MgCl2 and 0.5 % Triton X-100 with 1 mm PMSF, 0.1 mm TPCK, 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 phosphoramidon, 0.7 μg ml−1 pepstatin, 1 μg ml−1 E64 and 30 μg ml−1 bestatin, and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min on a rotary shaker. The mixture was centrifuged at 100 000 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant is referred to as the DS fraction. The pellet was resuspended in RIPA buffer (equal volume to the starting mixture) containing 15 mm Hepes (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 % Triton X-100, 1 % deoxycholate and 0.1 % SDS, and the above protease inhibitors. After 14 000 g centrifugation in a microcentrifuge at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected and is referred to as the DI fraction.

Cholesterol removal, detergent solubilization and gradient density floatation

In some cases, the actin cytoskeleton was disrupted by incubating BBs with 10 μm latrunculin A, 10 μm cytochalasin D or an equal volume of buffer (control) at 4 °C for 1 h immediately before cholesterol extraction. Purified BB from rabbit ileum was treated or not with 10 mm MβCD at 37 °C for 30 min in TNE buffer (25 mm Tris-HC1, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA) supplemented with 5 mm DTT, 1 mm Na3VO4 and 50 mm NaF, and a mixture of protease inhibitors, including 1 mm PMSF, 0.1 mm TPCK, 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin, 1 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 10 μg ml−1 phosphoramidon, 0.5 μg ml−1 pepstatin, 1 μg ml−1 E64 and 30 μg ml−1 bestatin (Lafont et al. 1999). The BB membranes were then solubilized with 1 % Triton X-100 for 30 min on a rotary shaker at 4 °C. Samples were adjusted to 35 % of OptiPrep (final volume, 1 ml) before being overlaid with step gradients of 30, 20, 10 and 5 % OptiPrep (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway). Each gradient was prepared with the same TNE buffer described above and adjusted to 1 % Triton X-100. Samples were centrifuged in a Beckman SW41Ti rotor at 40 000 r.p.m. at 4 °C for 4 h. Eleven fractions were collected from the bottom of the tubes. One-ninth of each fraction was analysed with SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Fractionation of total membranes by discontinuous OptiPrep step gradient

Total membrane vesicles (1-2 mg protein) isolated from ileal villus cells were loaded on a nine-step OptiPrep gradient which, consisted of 30, 27.5, 25, 22.5, 20, 17.5, 15, 12.5 and 10 % OptiPrep. Each step gradient was prepared with OptiPrep and Hepes buffer (20 mm, pH 7.2) containing 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm Na3VO4 and 50 mm NaF. Centrifugation was done in Beckman SW 41Ti rotor at 23 000 r.p.m. at 4 °C for 90 min. Twenty-one fractions were collected from the bottom of each centrifuge tube. A quarter of each fraction was analysed with SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Immunoaffinity isolation of endocytic vesicles using magnetic beads

EEA1 (early endosomal autoantigen 1) is present on the surface of early endosomes. Early endosomes were isolated by incubating partially purified early endosomes with magnetic beads (Dynabeads, M-500 subcellular, from Dynal) coated with anti-EEA1 monoclonal antibody (EEA1 mAb) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, rabbit anti-mouse IgG (linker) was incubated for 20 h at 22 °C on a rotary shaker with M-500 Dynabeads at a ratio of 5 μg linker per 107 beads in 0.1 m borate buffer pH 9.5 (final bead concentration, 5 × 108 beads ml−1). The coated beads were washed twice, 5 min each, in PBS pH 7.4 with 0.1 % (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 4 °C, once for 20 h in 0.2 m Tris pH 8.5 with 0.1 % (w/v) BSA at 22 °C and once for 5 min in PBS pH 7.4 with 0.1 % BSA at 4 °C. The linker-coated beads were incubated with anti-EEA1 mAb at a ratio of 5 μg per 107 beads (final bead concentration, 5 × 108 beads ml−1) for 2 h at 4 °C on a rotary shaker. After incubation, the beads were washed 4 times, 5 min each, in PBS pH 7.4 with 0.1 % BSA at 4 °C. Two micrograms of the resulting EEA1 mAb-coated beads (≈4.0 × 107 beads) was resuspended in 900 μl of buffer A containing PBS, pH 7.4, 2 mm EDTA and 5 % BSA, and used for each immunoisolation. The partially purified early endosomes were obtained by mixing the early endosomal fractions (1 and 2) from the fractionation of total membrane vesicles of ileal villus cells by OptiPrep gradients (see details above). A 100 μl sample of partially purified endosomes isolated from ilea treated with 10 mm MβCD, 10 μm cytochalasin D or buffer (control) was incubated with 900 μl buffer A containing EEA1 mAb-coated beads for 3 h at 4 °C with continuous mixing. The amount of the beads used was optimized to deplete all the EEA1 mAb-containing endosomes. After incubation, the beads were first washed 3 times, 15 min each, in buffer A, and then once for 5 min in PBS, pH 7.4, with 2 mm EDTA and 0.1 % BSA. The beads were resuspended in 100 μl of 1× SDS gel sample buffer and analysed with SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

SDS-PAGE, Western blotting and chemiluminescence detection

Proteins were separated on 10 % SDS polyacrylamide gels using Bio-Rad Protein IIxi Cell and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Western blotting and chemiluminescence detection were performed at room temperature. Briefly, nitrocellulose membranes were incubated first in PBST-milk (PBS buffer containing 0.1 % Tween-20 and 5 % milk) for 1 h and then with primary antibodies diluted with PBST-milk for another hour, with constant rocking on a shaker. At the end of the incubation, the blots were washed 3 times, 10 min each, with PBST, and subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted in PBST-milk for 1 h. After three washes, 10 min each, the blots were incubated with Renaissance Enhanced Luminol Reagent (NEN Life Science Products) for 20 s and exposed to Hyperfilm MP film (Amersham).

In vitro ileal villus cell BB Na+-H+ exchange

Na+-H+ exchange was determined in rabbit ileal BB made from ileal sheets exposed in vitro to EGF (200 ng ml−1) or buffer control as previously described (Cohen et al. 1991; Khurana et al. 1996). In brief, ileal sheets were exposed to EGF or control for 1 min at 37 °C following stabilization for 10 min after preparation. Villus cells were then scraped on ice with a glass slide, and BB membrane vesicles were prepared for transport studies by double Mg2+ precipitation. The final BB pellet was resuspended in (mm): 200 mannitol, 40 Mopso, 11.4 Tris, 9.6 Mes, pH 6.5 and 5 magnesium gluconate. Na+ transport buffers consisted of (mm): 211.8 mannitol, 28 Tris, 9.6 Mes, pH 8.0, 5 magnesium gluconate and 1 sodium gluconate (22Na+) with or without 200 μm methyl propyl amiloride (MPA). Uptake was for 5 s, which had been shown to be within the linear range of Na+ uptake in these vesicles (Cohen et al. 1991; Khurana et al. 1996). Initial uptake rates were expressed in pmol (mg protein)−1 s−1 and represent the MPA-inhibitable Na+ uptake.

Immunocytochemistry

Techniques of immunocytochemistry were performed on sections of rabbit ileum as recently described (Wade et al. 2000). Frozen sections of ileum were fixed with 2 % paraformaldehyde in PBS for 60 min and were incubated overnight with primary antibody at 4 °C. After washing they were incubated with secondary antibody (donkey or goat anti-rabbit; Jackson Immuno-Research Labs, West Grove, PA, USA) for 2 h at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies were coupled to Alexa 488 or 568 dyes (Molecular Probes) and were diluted 1:100. Sections were examined with a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal microscope.

RESULTS

Approximately 50 % of the BB NHE3 is DI

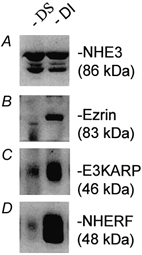

NHE3 has been shown to associate with the cytoskeleton in OK cells and PS120 cells (Lamprecht et al. 1998; Yun et al. 1998). In these cells, NHE3 co-precipitates with NHERF or E3KARP and ezrin, the last of which forms bridges between NHE3-E3KARP or NHERF and the actin cytoskeleton (Lamprecht et al. 1998; Yun et al. 1998). NHE3 (Hoogerwerf et al. 1996), NHERF and E3KARP are present in ileal villus cell BB (Fig. 1A and B), as is ezrin. Until now, no studies have examined the amount of ileal BB NHE3 that is linked to the cytoskeleton. To begin this characterization, we determined how much NHE3 was present in the DI vs. DS fractions of native intestinal BB. Ileal BB were solubilized with cold 0.5 % Triton X-100 and then centrifuged at 100 000 g. The resulting supernatant (DS) was collected and the pellet was resolubilized in RIPA buffer. After 14 000 g centrifugation, the RIPA-solubilized supernatant (DI), along with the DS fraction, were analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. NHE3 was distributed equally in the DS and DI fractions (≈52 and 48 %, respectively; Fig. 2A) as calculated by densitometric scanning. As shown in Fig. 2B–D, the three proteins reported to be NHE3-associated proteins in PS120 and OK cells, NHERF, E3KARP and ezrin (Lamprecht et al. 1998; Yun et al. 1998), were mostly DI fraction associated, with ezrin exclusively associated with the DI fraction. The latter finding indicates that the actin cytoskeleton was well preserved during the DI preparation (Reczek et al. 1997; Algrain et al. 1999).

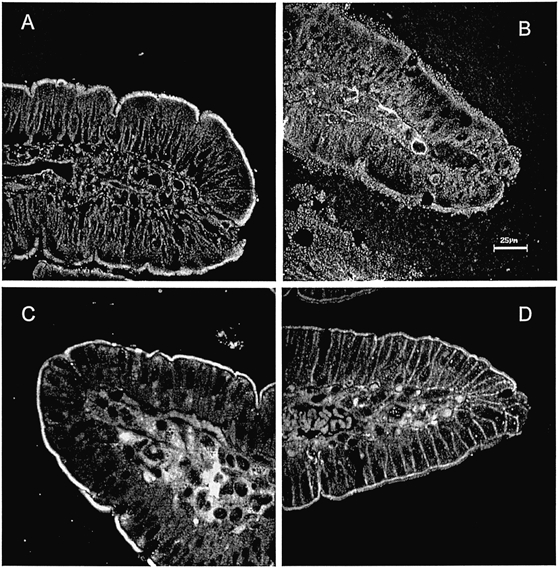

Figure 1. Immunofluorescence localization in rabbit ileum of ileal proteins used in raft studies.

NHERF (A), E3KARP (B), syntaxin 3 (C) and syntaxin 4 (D). Antibodies used are described in Methods. Scale bar, 25 μm.

Figure 2. Half of BB NHE3 is associated with the DI fraction of ileal BB membranes.

BBs were solubilized with 0.5 % Triton X-100 in Mes buffer. The solubilized fractions were designated DS and unsolubilized pellets were resolubilized in RIPA buffer and referred to as DI. Proteins in both DS and DI fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE and analysed by Western blot analysis for NHE3, ezrin, NHERF and E3KARP. Each blot was prepared from the same sample with loading of identical protein amounts. Identical results were obtained in three experiments.

The DI fraction of BB NHE3 is associated with lipid rafts and cytoskeleton

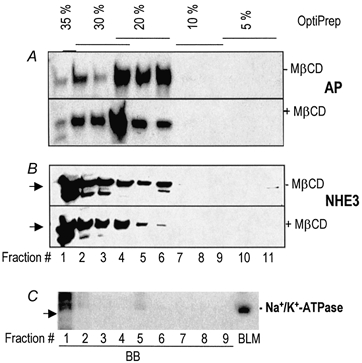

Increasing numbers of cytosolic and integral membrane proteins have been shown to be present in lipid rafts (Simons & Ikonen, 1997; Lamprecht et al. 1998). Thus, we sought to determine whether DI NHE3 was raft associated. The criterion used was whether the component of proteins, including NHE3, which were insoluble in cold Triton X-100 shifted from a lighter to a heavier membrane fraction, based on OptiPrep gradient fractionation, after cholesterol was removed with MβCD. This is the criterion currently used by Simons and co-workers (Lafont et al. 1999). The principle for this technique is as follows. Lipid rafts are detergent-resistant membranes with light density. When mixed with the highest density (35 %, final) of OptiPrep and applied at the bottom of an OptiPrep density gradient for ultracentrifugation, rafts will float to the lighter density fractions. Since lipid rafts are highly enriched in cholesterol, removing or sequestering cholesterol will destabilize/disrupt rafts and thereby increase their density (Simons & Toomre, 2001). Therefore, if rafts are disrupted by incubation with MβCD, which removes cholesterol, before being loaded in the gradient, lipid rafts and their associated proteins will be shifted from the lighter density to the heavier density fractions. As shown in Fig. 3A, alkaline phosphatase, a BB protein in small intestine, which has previously been shown to be present in lipid rafts (Zhang et al. 1996), was distributed on the OptiPrep gradient in fractions 1-6 and shifted from fractions 5 and 6 to fractions 1-4 with cholesterol depletion.

Figure 3. A fraction of BB NHE3 is present in cholesterol-enriched lipid rafts.

The BBs were treated (+) or not (-) with MβCD before solubilization with cold 1 % Triton X-100. The samples were subjected to floatation by fractionating on OptiPrep step gradients with concentrations as labelled on the top of the figure and analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with Abs as indicated on the right. A, alkaline phosphatase (AP); B, NHE3, an ∼90 kDa protein as shown by arrow; and C, Na+-K+-ATPase, indicated by an arrow. Purified basolateral membranes (5 μg) from rabbit ileum, together with the first nine fractions of cold, 1 % Triton X-100-treated BB proteins, fractionated as described above, were analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for Na+-K+-ATPase. Fractions 1-9 from the OptiPrep gradient were separately loaded. Fractions 1-6 contained at least ∼50 μg protein. Fractions 6-9 contained much less protein. Lack of Na+-K+-ATPase in the OptiPrep fractions suggests that there is minimal presence of BLM in the fractions containing NHE3. The large streaks in lane 1 (above the arrow head) are non-specific bands that are larger in size than Na+-K+-ATPase. Each blot in A and B was prepared from the same sample with identical loading of protein amounts. Similar results were obtained in three experiments.

As shown in Fig. 3B, NHE3 was present as an ≈90 kDa band on the OptiPrep gradient and was distributed primarily between the 20 and 35 % fractions. Similar to alkaline phosphatase, NHE3 in fractions 5 and 6 was shifted to heavier fractions with cholesterol depletion (Fig. 3B). The observation that only NHE3 in fractions 5 and 6 decreased and that these were the fractions from which alkaline phosphatase shifted with cholesterol depletion suggested that these are the two raft-enriched fractions of BBs. By densitometric scanning, raft-associated NHE3 was calculated to be ≈16 % of the total BB NHE3. To check for potential contamination of BLM proteins in these BB fractions, studies were undertaken with Na+-K+-ATPase, a well-established BLM marker. The first nine fractions of the same samples collected from OptiPrep gradient floatation used in Fig. 3A and B, together with purified rabbit ileal BLM were separated by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with mAb against Na+-K+-ATPase (Fig. 3C). Only a small amount of Na+-K+-ATPase was detected in BB fractions, especially considering that total BLM protein loaded for comparison was less than 1/10 of the BB loaded in each lane. This result indicated that the BB had only a minor amount of contamination with BLM.

Syntaxin 4 but not syntaxin 3 associates with ileal BB lipid rafts

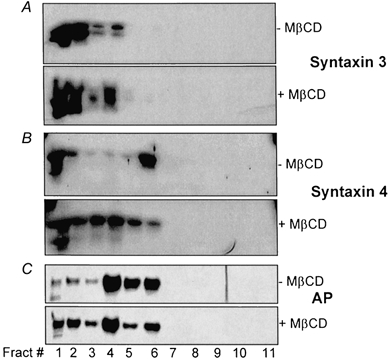

To find other lipid raft markers in the BB, floatation of syntaxin 3 and syntaxin 4 on OptiPrep gradients was studied. This was based on reports that in MDCK cells syntaxin 3 was localized in the apical membrane where it was shown to be raft associated, whereas syntaxin 4 was basolateral and not raft associated (Lafont et al. 1999). Syntaxin 3 was also found to localize at the apical membranes of human intestinal Caco-2 cells (Delgrossi et al. 1997). In preliminary studies, localization of syntaxin 3 and 4 in rabbit ileal epithelium was determined by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 1C and D). Syntaxin 3 was exclusively apical whereas syntaxin 4 occurred in both BB and lateral domains. Sections (between 29 and 45 kDa molecular mass markers) were cut from the same blots used in Fig. 3 and immunostained with pAb to either syntaxin 3 or 4. Both syntaxin 3 and 4 were present in the BB. A large portion of syntaxin 4 was associated with the raft-associated fractions, whereas little syntaxin 3 was associated with these fractions (Fig. 4A and B). Importantly, treatment with MβCD dramatically changed the floatation of syntaxin 4 to heavier fractions whereas ileal syntaxin 3 exhibited only a small shift (Fig. 4A and B). These results show that ileal syntaxin 4 but not syntaxin 3 associates with lipid rafts. Note that these results are different from those found using MDCK cells, in which syntaxin 3 but not syntaxin 4 was raft associated in apical membranes and played an important role in apical membrane docking and fusion (Lafont et al. 1999). Considering the minimal BLM contamination of the ileal BB as shown in Fig. 3 and the immunocytochemical studies (see above), it is likely that both the syntaxin 3 and 4 identified in Fig. 4 represent that present in ileal apical membranes.

Figure 4. Syntaxin 4 but not syntaxin 3 is associated with lipid rafts.

Cholesterol extraction of BB and subsequent OptiPrep floatation experiments were done as described in Fig. 3. Immunostaining was performed using Abs against the proteins indicated on the right of the figure. Each blot was prepared from the same sample with identical loading of protein amounts. Similar results were obtained in three experiments.

Association of BB NHE3 with lipid rafts is dependent on the actin cytoskeleton

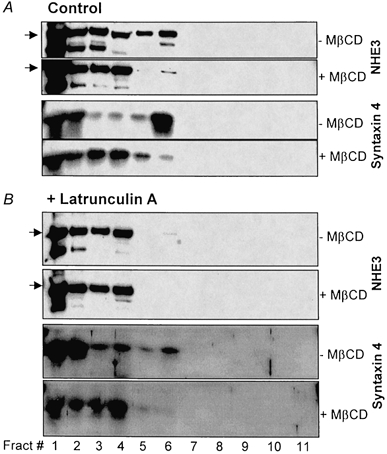

The actin cytoskeleton has been implicated as interacting directly with lipid rafts. First, actin, along with α-actinin, was shown to co-immunoprecipitate with annexin II from solubilized lipid rafts (Finbow & Harrison, 1997). Second, Oliferenko et al. (1999) showed recently that there was a direct interaction of raft-associated CD44 with the underlying actin cytoskeleton. Since the actin cytoskeleton was shown to be associated with lipid rafts (Mu et al. 1995), and reports from our laboratory and others suggest that NHE3 might associate with the actin cytoskeleton via the PDZ domain-containing proteins NHERF or E3KARP (Lamprecht et al. 1998; Yun et al. 1998; Weinman et al. 2000), we postulated that the NHE3-raft association might be dependent on actin filaments. In studies shown in Fig. 5, use was made of latrunculin A, a sponge toxin that disrupts actin microfilament organization by binding to monomeric G-actin in a 1:1 complex at submicromolar concentrations, under conditions (10 μm latrunculin A or cytochalasin D, 1 h, at 4 °C) which greatly decreased the amount of BB actin (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 5, after treatment of ileal BB with latrunculin A, association of NHE3 with the rafts was nearly completely abolished (compare Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, the same treatment had a somewhat lesser effect on the raft-syntaxin 4 association (Fig. 5A and B). Similar results were obtained when latrunculin A was replaced with cytochalasin D (data not shown). These results suggest that the association of NHE3 with BB rafts is dependent on intact BB actin, but not all BB raft proteins have this extent of dependence. It is important to point out that the mechanism by which an intact cytoskeleton is needed for the raft association of NHE3 or other proteins has not been identified.

Figure 5. The association of NHE3 with lipid rafts is dependent on an intact actin cytoskeleton.

The BBs were incubated with either latrunculin A (10 μm), or buffer (Control) on ice for 1 h immediately before cholesterol extraction. Cholesterol extraction, OptiPrep gradient floatation and protein analyses were done as described in Fig. 3. Immunostaining was done using Abs against proteins indicated on the right of the figure. Arrow on left indicates NHE3. Similar results were obtained in three experiments.

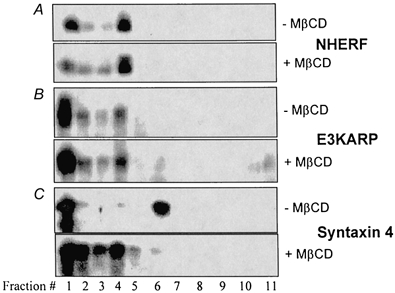

NHERF and E3KARP do not appear to be involved in the BB NHE3-raft association

NHE3 has been shown to form a complex with NHERF or E3KARP and the actin-binding protein ezrin (Lamprecht et al. 1998; Yun et al. 1998; Weinman et al. 2000). Since actin was shown to be required for the association of NHE3 with lipid rafts, and E3KARP and NHERF were shown to be predominantly in the DI fraction, we hypothesized that NHE3 might be attached to rafts by actin through NHERF or E3KARP. This hypothesis was tested by investigating whether NHERF or E3KARP was present in rafts after OptiPrep gradient floatation. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, little NHERF or E3KARP was detected in the raft fractions (lanes 5 and 6), and neither demonstrated a shift to heavier fractions with MβCD exposure, while the raft marker syntaxin 4 did shift in the same membranes. After prolonged exposure of the blots, very small amounts of NHERF/E3KARP were observed in the raft fractions (data not shown). These results strongly suggest that NHERF and E3KARP do not participate in the NHE3-raft association and that the NHERF/E3KARP-associated NHE3 is not the pool associated with lipid rafts. Furthermore, EGF treatment did not promote the association of NHERF or E3KARP with lipid rafts (data not shown). It remains to be experimentally determined whether the non-raft DI ileal BB NHE3 is connected to the actin cytoskeleton by NHERF/E3KARP/ezrin or whether NHE3 associates with the actin cytoskeleton by additional mechanisms.

Figure 6. NHERF and E3KARP are not associated with lipid rafts.

Blots were prepared from the same samples as described in Fig. 3, except that immunostaining was done with pAbs against NHERF, E3KARP and syntaxin 4 as indicated. Similar results were obtained in three experiments.

Rapid stimulation of NHE3 occurs in the lipid raft/DI pools of BB NHE3

Based on the results of these studies, ileal BB NHE3 can be subdivided into three populations under basal conditions: (i) ≈52 % in the DS fraction; (ii) ≈16 % in the raft-associated DI fraction (Fig. 3); and (iii) ≈32 % in the non-raft associated DI fraction, which is assumed to be cytoskeleton associated (calculated by subtracting ≈16 % of BB NHE3 which is raft associated from 48 % of BB NHE3 in the DI fraction). Thus ≈33 % of the DI pool of BB NHE3 appears to be associated with lipid rafts and ≈67 % associated with the cytoskeleton. Multiple questions remain relating to the distribution of NHE3 among these BB pools. For instance, what is the physiological significance of the NHE3-raft association?

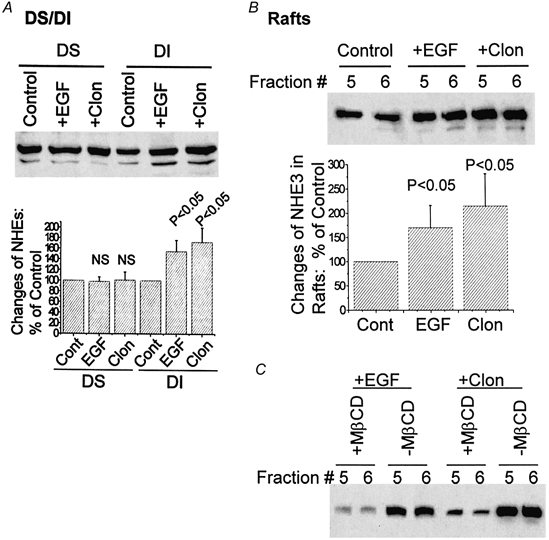

We speculated that the three newly defined pools of BB NHE3 (DS, DI raft associated, DI cytoskeleton associated) might be involved differently in signal transduction processes that rapidly stimulate NHE3 by increasing the amount of BB NHE3. We and others have previously shown that epithelial NHE3 activity and ileal NaCl absorption, which involves NHE3, are rapidly stimulated by EGF (Ghishan et al. 1992; Donowitz et al. 1994, 1999), as also occurs in response to the α2 adrenergic agonist clonidine (Chang et al. 1982). This stimulation occurs very quickly upon addition of EGF or clonidine and is present in the first flux periods, which start immediately with addition of each agonist (Chang et al. 1982; Janecki et al. 2000). We tested whether EGF and clonidine stimulation of NHE3 occurs through redistribution of NHE3 among these three BB pools or whether the stimulation of NHE3 and the increase in total BB NHE3 amount involves more than one of these pools. The approaches taken included: (1) treatment of isolated ilea with EGF and clonidine, separately, for 1 min in vitro, which has been shown to stimulate ileal Na+ absorption (Chang et al. 1982; Donowitz et al. 1994; Khurana et al. 1996); (2) isolation of BB membranes; (3) determination of BB Na+-H+ exchange (done for EGF treatment); and (4) biochemical determination of the NHE3 distribution among the three BB pools.

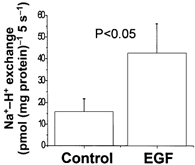

To initially be certain that the conditions of this study were associated with stimulation of NHE3, ileal sheets were incubated in vitro for 1 min in the absence or presence of 200 ng ml−1 EGF and BB membrane vesicles were prepared. Na+-H+ exchange activity was determined in these vesicles. As shown in Fig. 7, EGF treatment increased BB Na+-H+ exchange. These results are similar to results when rabbit ileal and rat jejunal BB Na+-H+ exchange was determined 15 and 30 min, respectively, after in vitro exposure of intestine to EGF (Ghishan et al. 1992; Khurana et al. 1996). Distribution of NHE3 in the BB DS and DI pools was determined. As shown in Fig. 8A, when equal amounts of BB were compared, EGF (200 ng ml−1) and clonidine (3 μm) increased the amount of NHE3 in the BB DI pool but did not alter the amount of NHE3 in the DS pool. Specifically, EGF and clonidine increased the amount of NHE3 in the DI pool by 57 % (P < 0.05) and 93 % (P < 0.05) above control, respectively. This result shows that the total amount of BB NHE3 (DS plus DI) is increased rapidly by EGF and clonidine. The DI pool of BB NHE3 is increased by EGF and clonidine over a short time frame, but the DS pool does not take part in this aspect of rapid stimulation.

Figure 7. EGF rapidly increases ileal BB Na+-H+ exchange.

Sheets of ileal mucosa were exposed to EGF (200 ng ml−1) or buffer control for 1 min. BB vesicles were prepared and Na+-H+ exchange determined as MPA-sensitive 22Na+ uptake at 5 s, which is within the linear range for these vesicles (Cohen et al. 1991; Khurana et al. 1996). Results are means ±s.e.m. from BB preparations from three separate animals. P value is comparison of control vs. EGF-treated BB determined by Student's paired t test.

Figure 8. EGF and clonidine increase the amount of NHE3 in the ileal BB by increasing NHE3 in the BB total DI and lipid raft fractions.

Isolated ilea were treated with buffer (Control), EGF (200 ng ml−1) or clonidine (3 μm; Clon), respectively, for 1 min before BB isolation. The BB from each experiment was subjected to either DS/DI separation (A) or a floatation experiment on OptiPrep gradients with analysis of NHE3 in the lipid raft fractions (fractions 5 and 6; B and C). NHE3 amount in each preparation was analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. A, EGF and clonidine treatments elevate the presence of NHE3 in the DI but not the DS fraction of BB. In the upper panel, results from a single experiment are shown. In the lower panel, means ±s.e.m. of three experiments quantified by scanning densitometry of DS or DI are normalized to the control (Cont, each control set as 100 %). P values of changes with EGF or clonidine are with respect to changes of NHE3 in control (paired t test). B, the increase of NHE3 after treatment with EGF or clonidine occurs in lipid raft fractions. Results from lipid raft fractions 5 and 6 from the OptiPrep gradients of a single experiment are shown in the upper panel. In the lower panel, results from three experiments were normalized to control, quantified by scanning densitometry and means ±s.e.m. are shown. P values are calculated by Student's paired t test comparing changes of NHE3 in EGF- or clonidine-treated ilea with changes in the control. C, NHE3 in BB fractions 5 and 6 of EGF- and clonidine-treated ileum shifted with MβCD treatment, as was shown for control BB in Figs 3 and 5.

In which of the two DI pools does the stimulation of NHE3 occur: cytoskeleton associated or lipid rafts? Since we are technically unable to completely isolate the cytoskeletal DI fraction, whereas we can purify the lipid raft fractions by floatation on a gradient, we examined the amounts of BB NHE3 in lipid rafts prepared from untreated and EGF- and clonidine-treated ilea. For comparison, NHE3 in the BB lipid raft fractions (fractions 5 and 6) collected from OptiPrep floatation gradients was analysed by Western analysis. As shown in Fig. 8B, 1 min treatments with EGF and clonidine increased the raft fraction of BB NHE3 by 75 % (P < 0.05) and 120 % (P < 0.05) above control, respectively. NHE3 in these fractions from EGF- and clonidine-treated ileum shifted with MβCD similar to that for control ileum (compare Fig. 8C with Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). The magnitude of the stimulation of NHE3 in the lipid raft fractions shown in Fig. 8B is slightly greater than the increases of the total DI-associated NHE3. These results show that at least part of the EGF- and clonidine-induced increase in BB NHE3 occurs in BB lipid rafts.

Lipid rafts and the actin cytoskeleton are necessary for basal endocytosis of NHE3

In addition to the stimulation of NHE3 by regulated exocytosis, regulation of NHE3 via endocytosis under basal and stimulated conditions has been demonstrated in NHE3-transfected PS120 (Akhter et al. 2000; Janecki et al. 2000) and AP-1 fibroblasts (D'Souza et al. 1998; Kurashima et al. 1999) as well as in Caco-2 cells (Janecki et al. 1998) and rabbit ileal villus epithelial cells (Chow et al. 1999). As an example, in Caco-2 cells, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) inhibits NHE3 by increasing the rate of NHE3 endocytosis (Janecki et al. 1998). Lipid rafts were recently shown to be required for clathrin-dependent endocytosis in MDCK cells (Rodal et al. 1999). NHE3 has been shown to co-sediment with clathrin in ileal BB (Chow et al. 1999). Thus studies were undertaken to determine whether rafts might be involved in NHE3 endocytosis that occurs under basal conditions. In these studies, it was determined whether extraction of cholesterol from ileal epithelial cells would affect basal endocytosis of NHE3. In addition, the parallel effect of disrupting actin cytoskeleton by cytochalasin D was studied to determine whether raft and cytoskeleton effects overlapped. Cytochalasin D, which binds to the barbed (faster-growing) end of actin, cleaves actin filaments and thereby alters actin polymerization. Ilea were treated with buffer (control), 10 mm MβCD, or 10 μm cytochalasin D; membrane vesicles were separated by OptiPrep step gradients; and proteins of interest were analysed by SDS-PAGE and immunostaining. Marker proteins of three major vesicles were immunostained. They were sucrase-isomaltase for BB, Na+-K+-ATPase for BLM, and EEA1 for early endosomes (Mu et al. 1995). As shown in Fig. 9A–C, the three vesicles were well separated. Na+-K+-ATPase was concentrated in fractions 9-15 (Fig. 9A, Control), while sucrase- isomaltase was detected mainly in fractions 4-10 (Fig. 9B, Control). EEA1 was found exclusively in fractions 1 and 2 (Fig. 9C, Control). NHE3 was detected in both fractions that contained the early endosomal marker EEA1 (compare Fig. 9C and D, Control, lanes 1 and 2) and BB fractions where it co-localized with sucrase (compare Fig. 9B and D, Control, lanes 4-10). Compared to control, treatments with cytochalsin D and MβCD gave rise to strikingly similar changes of distribution patterns of the three different vesicles. Both treatments resulted in slight shifts in the distributions of BLM and BB from heavier fractions (BLM, Fig. 9A, lanes 8-14; BB, Fig. 9B, lanes 5-9) to lighter fractions (BLM, Fig. 9A, lanes 9-16: BB, Fig. 9B, lanes 6-10). Neither treatment affected the distribution pattern of early endosomes (Fig. 9C, lanes 1 and 2). These observations suggested that cytochalasin D and MβCD slightly reduced the density of BB and BLM vesicles. The changes in NHE3 distribution in the BB were very similar to those of sucrase-isomaltose (compare Fig. 9B and D, lanes 4-11). These observations suggest that the actin cytoskeleton and lipid rafts are functionally tightly linked. Importantly, treatment with both cytochalasin D and MβCD significantly reduced the amount of NHE3 in the fractions containing the early endosomes (Fig. 9D, lanes 1 and 2) by ≈50 % as calculated by densitometric analysis. In control ileum, early endosomal NHE3 accounted for ≈30 % of the total (Fig. 9E). After cytochalasin D and MβCD treatment, NHE3 in the early endosome decreased to ≈15 and 17 % of the total, respectively. This represents a 48 % (P < 0.05) and 55 % (P < 0.05) reduction, respectively, of NHE3 in early endosomes (Fig. 9E).

Figure 9. Disruption of lipid rafts or the actin cytoskeleton decreases the basal endocytosis of NHE3 from ileal BB.

Isolated ilea were divided equally and randomly into three groups, each of which was incubated separately with cytochalasin D (10 μm; + Cyt D), MβCD (10 mm; + MβCD) or buffer (Control). Total villus membranes of each treated ileum were isolated and fractionated on 10-30 % OptiPrep step gradients. One-fifth of each fraction (21 total) was analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Fractions 1-21 represent membrane vesicles with the densities from the highest to the lowest. Immunostaining was done separately with mAb to basolateral marker Na+-K+-ATPase (A), or pAb to BB marker sucrase-isomaltase (B), early endosomal autoantigen (EEA1; C), and NHE3 (D). For each treatment, several Abs were used to probe either different portions of the same blot (cut into segments according to the molecular mass standards) or duplicate blots prepared from the same sample. E, percentage changes of NHE3 in early endosomal vesicles (fractions 1 and 2 from D) were calculated by densitometric scanning. The percentage of early endosomal NHE3 was calculated as the percentage of the total NHE3 detected in each blot. Results shown in A–D are from a single representative experiment. Results in E are means ±s.e.m. from three separate experiments. P values compare percentage of total NHE3 in early endosomes of cytochalasin- or MβCD-treated ilea with Control by Student's paired t test.

It is important to note that two distinct techniques were employed in Fig. 9 and Fig. 3, although both used Opti-Prep gradient fractionations. In Fig. 9, the gradient was designed to separate different membrane vesicles that had never been treated with any detergent. Therefore, although NHE3 was shifted from the rafts to the DS pool after MβCD treatment, it would still stay in the membrane and sediment along with BB vesicles. The density of the BB vesicles was not significantly changed. In Fig. 3, the BB was solubilized with 1 % Triton X-100 and therefore all the membranes were lysed except lipid rafts. The lipid rafts have a light density and thus they float to a lighter density of the gradient. Disruption of lipid rafts by MβCD causes the shift of raft proteins from lighter density to heavier density fractions.

Because the above analysis of NHE3 in the early endosomal fractions was based on co-localization with EEA1 and could have been confounded by the presence of other organelles in these fractions, further studies were carried out to more specifically examine the amount of NHE3 in early endosomes. Early endosomes were immunoisolated using EEA1 mAb-coated Dynal M500 magnetic beads from fractions 1 and 2 of the OptiPrep gradients as described in Fig. 9C made from control, and cytochalasin D- or MβCD-treated ilea. The amounts of NHE3 in the early endosomes (EEA1 associated) were reduced by ≈50 % after treatment of isolated ilea with cytochalasin D or MβCD (Fig. 10). These results further showed that altering both lipid rafts and the actin cytoskeleton decreased endocytosis in ileal epithelial cells, including that of NHE3.

Figure 10. Changes of NHE3 amounts in EEA1-containing endosomes after treatment of rabbit ilea with cytochalasin D and MβCD.

Partially purified endosomal vesicles of ileal villus cells (Control, cytochalasin D treated or MβCD treated) were obtained by mixing fractions 1 and 2 of OptiPrep gradient fractions prepared as described in Fig. 9. A 100 μl sample of each mixture was incubated with Dynal M500 beads coated with anti-EEA1 antibody as described in Methods for immunoisolation of EEA1-containing endosomes. A, bead-associated proteins and 100 μl of the post-bead supernatant were analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotted with antibodies to EEA1 and NHE3. Shown here is one of the two experiments. B, the quantification of the Western blots of the two independent experiments by densitometric scanning is shown. The control of each experiment was set as 100 % and the treated samples were expressed as the percentage of the corresponding control.

DISCUSSION

Ileal Na+-absorbing cell NHE3 is present in three BB pools. Our study demonstrates a role for the DI pool, including the lipid raft pool, of NHE3 in the EGF and clonidine stimulation of BB Na+-H+ exchange, while showing that the DS pool of NHE3 is not involved in this stimulation. While the DI fraction of NHE3 is considered to be made up of NHE3 linked to the cytoskeleton plus that in lipid rafts, we acknowledge that the DS pool might include NHE3 initially loosely attached to DI, which becomes dissociated during preparation.

To define the lipid raft population of BB NHE3, we used OptiPrep gradients for the floatation experiments as described by Lafont et al. (1999), one of the pioneering groups that developed the concept of lipid rafts. However, another method using sucrose gradients for floatation is also widely used for defining the raft population (Lafont et al. 1999). During the preparation of this manuscript, we tested isolating BB lipid rafts using a sucrose gradient and Mes buffer approach (Lafont et al. 1999). Forty per cent of total BB NHE3 was present in the MβCD-sensitive lipid rafts using sucrose gradient separation (X. Li & M. Donowitz, unpublished data). These results suggested that (i) potentially the majority of the 50 % DI-associated NHE3 is due to its raft association; and (ii) OptiPrep gradient separation may under-estimate the percentage of total NHE3 in the BB lipid rafts. This result also suggested that the selection of buffers and density gradients affects the outcome of lipid raft isolation. However, we have chosen to use the most classic definition of rafts to allow our results to be compared with other studies of lipid rafts.

The existance of multiple BB pools of NHE3 is an important concept that emerges from the current studies. The fact that E3KARP and NHERF are present in the DI fraction but not in lipid rafts is consistent with the view that E3KARP and NHERF are part of the cytoskeleton, and this implies that at least part of the cytoskeleton-attached NHE3 is separate from the raft pool of NHE3. The E3KARP/NHERF pool of NHE3 is involved in cAMP inhibition of NHE3 (Lamprecht et al. 1998; Yun et al. 1998). Since EGF/clonidine increases NHE3 in the raft pool, this implies that stimulated (EGF/clonidine) and inhibited (cAMP) pools of NHE3 are present in different BB domains. It will be important to determine whether these pools of NHE3 can be interconverted as part of signal transduction or are permanently separate. The presence of multiple BB pools of NHE3 was also recently described for renal cortex in which the DI NHE3 was not studied, but the Triton X-100-soluble DS pool was divided into megalin-associated and megalin-independent pools of NHE3 (Biemesderfer et al. 1999). The megalin-independent pool functioned and the megalin-associated pool was inactive.

How does NHE3 become associated with lipid rafts? A large body of evidence indicates that proteins associate with rafts in four ways: (i) glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins target to rafts through acyl chain interactions (Schroeder et al. 1994; Scheiffele et al. 1999); (ii) cytosolic proteins such as Src family kinases and the neuronal protein GAP-43 are myristoylated at glycine and/or palmitoylated at cysteine residues to provide anchoring motifs for raft association (Milligan et al. 1995; Simons & Ikonen, 1997; Brown & London, 1998); (iii) some membrane proteins such as haemaglutinin of the influenza virus partition into rafts due to intrinsic properties of their transmembrane domains (Scheiffele et al. 1998); and (iv) direct protein-cholesterol interactions (Thiele et al. 1999). Some insight into how proteins are incorporated into rafts was provided by the use of a novel photoactivatable cholesterol, in which direct binding to cholesterol of several membrane raft proteins was demonstrated (Thiele et al. 1999). Cholesterol directly bound caveolin in MDCK cells, while in neuronal cells, it bound synaptophysin, synaptotagmin, and the c subunit of V-ATPase. This suggests a new way of thinking about rafts in which protein-cholesterol binding may contribute to the composition and formation of rafts (Thiele et al. 1999). NHE3 does not appear to contain any of the above known residues or motifs that could account for its raft association. Thus, we suggest a role for the NHE3 transmembrane domains in the raft association, perhaps via direct interactions with cholesterol.

What is the function of the NHE3 pool in lipid rafts? Previously suggested raft functions that are potentially relevant to the short-term regulation of NHE3 include: (i) signal transduction (Simons & Toomre, 2001); (ii) apical membrane targeting (Simons & Ikonen, 1997; Galli et al. 1998; Mayor et al. 1998; Cheong et al. 1999; Lafont et al. 1999); (iii) regulated exocytosis (Gagescu et al. 2000); and (iv) endocytosis (Gottlieb et al. 1993; Kasahara & Sanai, 1999). The function demonstrated here is in the EGF- and clonidine-induced rapid increase in the amount of BB NHE3 that accompanied the rapid stimulation of BB Na+-H+ exchange activity. The percentage change in the raft NHE3 in BB from EGF- and clonidine-treated ileum (75 and 120 %, respectively) exceeded the percentage increase in DI NHE3 (57 and 93 %, respectively), suggesting that raft NHE3 was involved in the movement of NHE3 to the BB. We further conclude that the increase in BB NHE3 amount caused by EGF and clonidine is not due to a redistribution of NHE3 from the apical DS pool, which does not change, but is more likely to be due to increased exocytosis from the recycling endosomes, although this has not been measured directly. Whether lipid rafts contribute to the increase in BB NHE3 via a role in signal transduction or regulated exocytosis is not known.

NHE3 undergoes endocytosis and exocytosis under basal conditions. This occurs rapidly when NHE3 is expressed in AP-1 or PS120 fibroblasts, where its surface half-life is approximately 15 min (D'Souza et al. 1998). In this study we showed that lipid rafts and the actin cytoskeleton play a necessary role in NHE3 endocytosis. However, these studies have not shown that these effects on NHE3 endocytosis are specific or whether it is the lipid raft pool of NHE3 which is involved. This is because both lipid rafts and the cytoskeleton previously have been shown to be necessary for other aspects of epithelial cell endocytosis (Gottlieb et al. 1993; Kasahara & Sanai, 1999).

Previous studies of the role of the actin cytoskeleton in the regulation of NHE3 have been contradictory. The actin cytoskeleton has been shown to be involved in apical endocytosis in epithelial cells (Gottlieb et al. 1993). An intact actin cytoskeleton was required for clathrin-mediated endocytosis from the apical membrane, including in Caco-2 cells (Gottlieb et al. 1993). Recently NHE3 was shown to be present in clathrin-coated vesicles in ileal BB (Chow et al. 1999). In addition, based on cell culture models, the actin cytoskeleton has been shown to physically interact with NHE3 and to be involved in the regulation of plasma membrane NHE3 in NHE3-transfected AP-1 cells (Kurashima et al. 1999). Cytochalasin B and D and latrunculin A induced a profound inhibition of NHE3 activity in AP-1 cells (Kurashima et al. 1999). Intriguingly, however, this inhibition was not due to a diminution in the amount of NHE3 at the plasma membrane, indicating that the inhibitory effect might be via a change of the intrinsic activity of the transporter, perhaps by changes in other associated signalling molecules, rather than via inhibition of NHE3 endocytosis. The explanation for these differences in studies with epithelial cells and fibroblasts is unknown. However, since the current studies were performed with endogenous NHE3 in rabbit ileum, these results implicating cytoskeleton and lipid rafts in NHE3 endocytosis may be more relevant to intestinal regulation of NHE3.

In summary, several important findings are presented: (1) a multi-membrane-spanning domain transport protein (NHE3) is associated with lipid rafts in the plasma membrane; (2) lipid rafts are involved in the stimulation of NHE3 by EGF and clonidine, which occurs by a mechanism in which there is a rapid increase in the amount of BB NHE3; (3) although most NHERF and E3KARP are present in the DI fraction of ileal epithelial cells, NHE3-raft association is mediated by the actin cytoskeleton but occurs via a mechanism other than via NHERF/E3KARP association; and (4) both lipid rafts and the actin cytoskeleton play a necessary role in the endocytosis of NHE3 from the ileal BB under basal conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH NIDDK grants, RO1-DK26523, RO1-DK5581, RO1-DK32839 and PO1-DK44484, T32 DK07632, the Meyerhoff Digestive Diseases Center and the Hopkins Center for Epithelial Disorders, and by a Boursier Rothschild-Mayent Sabbatical Fellowship.

References

- Akhter S, Cavet ME, Tse C-M, Donowitz M. C-terminal domains mediate basal endocytosis of NHE3: basal and serum-stimulated membrane trafficking of NHE3 occurs through different domains. Biochemistry. 2000;3:1990–2000. doi: 10.1021/bi991739s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algrain M, Turunen O, Vaheri A, Louvard D, Arpin M. Ezrin contains cytoskeleton and membrane binding domains accounting for its proposed role as a membrane-cytoskeletal linker. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;120:129–139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemesderfer D, Nagy T, Degrat B, Aronson PS. Specific association of megalin and the Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 in the proximal tubule. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:17518–17524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, London E. Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 1998;14:111–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EB, Field M, Miller RJ. Alpha 2-adrenergic receptor regulation of ion transport in rabbit ileum. American Journal of Physiology. 1982;242:G237–242. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.3.G237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong KH, Zacchetti D, Schneeberger EE, Simons K. VIP/MAL, a lipid raft-associated protein, is involved in apical transport in MDCK cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:6241–6248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow C-W, Khurana S, Woodside M, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. The epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE3, is internalized through a clathrin-mediated pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:37551–37558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen ME, Wesolek J, McCullen J, Rys-Sikora K, Pandol S, Rood RP, Sharp GWG, Donowitz M. Carbachol and elevated Ca2+-induced translocation of functionally active protein kinase C to the brush border of ileal Na+ absorbing cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1991;88:855–863. doi: 10.1172/JCI115387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgrossi M, Breuza L, Mirre C, Chavries P, Lebivic A. Human syntaxin 3 is localized apically in human intestinal cells. Journal of Cell Science. 1997;110:2207–2214. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.18.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donowitz M, Janecki A, Akhter S, Cavet ME, Sanchez F, Lamprecht G, Khurana S, Kwon-Lee W, Yun C, Tse CM. Short-term regulation of NHE3 by EGF and protein kinase C but not protein kinase A involves vesicle trafficking in epithelial cells and fibroblasts. In: Domschke W, Stoll R, Brasitus TA, Kagnoff MF, editors. Intestinal Mucosa and its Diseases. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers and Falk Foundation; 1999. pp. 99–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donowitz M, Montgomery JL, Walker MS, Cohen ME. Brush-border tyrosine phosphorylation stimulates ileal neutral NaCl absorption and brush-border Na+/H+ exchange. American Journal of Physiolology. 1994;266:G647–656. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.266.4.G647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donowitz M, Tse CM. Molecular physiology of mammalian epithelial Na+/H+ exchanger NHE2 and NHE3. In: Barrett K, Donowitz M, editors. Molecular Physiology of Intestinal Transport. Vol. 50. San Diego: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 437–484. [Google Scholar]

- D'Souza S, Garcia-Cabado A, Yu F, Teter K, Lukacs G, Skorecki K, Moore HP, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. The epithelial sodium-hydrogen antiporter Na+/H+ exchanger accumulates and is functional in recycling endosomes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:2035–2043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finbow ME, Harrison MA. The vacuolar H+-ATPase: a universal proton pump of eukaryotes. Biochemical Journal. 1997;324:697–712. doi: 10.1042/bj3240697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Tuma PL, Finnegan CM, Locco L, Hubbard AL. Endogenous syntaxins 2, 3 and 4 exhibit distinct but overlapping patterns of expression at the hepatocyte plasma membrane. Biochemical Journal. 1998;329:527–538. doi: 10.1042/bj3290527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagescu R, Demaurex N, Parton RG, Hunziker W, Huber LA, Gruenberg J. The recycling endosome of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells is a mildly acidic compartment rich in raft components. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2000;11:2775–2791. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.8.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli T, Zahraoui A, Vaidyanathan VV, Gjian R, Tian JM, Karin M, Niemann H, Louvard D. A novel tetanus neurotoxin-insensitive vesicle-associated membrane protein in SNARE complexes of the apical plasma membrane of epithelial cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1998;9:1437–1448. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghishan FK, Kikuchi K, Riedel B. Epidermal growth factor up-regulates intestinal Na+/H+ exchange activity. Proceedings of the Society of Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1992;201:289–295. doi: 10.3181/00379727-201-43510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb TA, Ivanov IE, Adesnik M, Sabatini DD. Actin microfilaments play a critical role in endocytosis at the apical but not the basolateral surface of polarized epithelial cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;120:695–710. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerwerf WA, Tsao SC, Devuyst O, Levine SA, Yun CH, Yip JW, Cohen ME, Wilson PD, Lazenby AJ, Tse CM, Donowitz M. NHE2 and NHE3 are human and rabbit intestinal brush border proteins. American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270:G29–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.1.G29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecki A, Janecki M, Akhter S, Donowitz M. Basic fibroblast growth factor stimulates surface expression and activity of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 via mechanism involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:8133–8142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecki AJ, Montrose MH, Tse CM, de Medina FS, Zweibaum A, Donowitz M. Development of an endogenous epithelial Na+/H+-exchanger (NHE3) in three clones of Caco-2 cells. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:G292–305. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.2.G292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecki AJ, Montrose MH, Zimniak P, Zweibaum A, Tse CM, Khurana S, Donowitz M. Subcellular redistribution is involved in acute regulation of the brush border Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 in human colon adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2: protein kinase C-mediated inhibition of the exchanger. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:8790–8798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara K, Sanai Y. Possible roles of glyco-sphingolipids in lipid rafts. Biophysical Chemistry. 1999;82:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(99)00111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P, Simons K. Cholesterol is required for surface transport of influenza virus hemagglutin. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;140:1357–1367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana S, Nath SK, Levine SA, Bowser JM, Ming C-M, Cohen ME, Donowitz M. Brush border phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates epidermal growth factor stimulation of intestinal NaCl absorption and Na+/H+ exchange. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:9919–9927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurashima, K, D'Souza S, Szaszi K, Ramjeeingh R, Orlowski J, Grinstein S. The apical Na+/H+ exchanger isoform NHE3 is regulated by the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:29843–29849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurashima K, Yu FH, Cabado AG, Szabo EZ, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Identification of sites required for down-regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 activity by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. phosphorylation-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:28672–28679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont F, Lecat S, Verkade P, Simons K. Annexin XIIIb associates with lipid microdomains to function in apical delivery. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;142:1413–1427. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont F, Verkade P, Galli T, Wimmer C, Louvard D, Simons K. Raft association of SNAP receptors acting in apical trafficking in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1999;96:3734–3738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht G, Weinman EJ, Yun CH. The role of NHERF and E3KARP in the cAMP-mediated inhibition of NHE3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:29972–29978. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine SA, Montrose MH, Tse CM, Donowitz M. Kinetics and regulation of 3 cloned mammalian Na+/H+ exchangers study expressed in a fibroblast cell line. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:25527–25535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maples CJ, Ruiz WG, Apodaca G. Both microtubules and actin filaments are required for efficient postendocytotic traffic of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272:6741–6751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JR, Navarro-Polanco R, Coppock EA, Nishiyama A, Parshley L, Grobaski TD, Tamkun MM. Differential targeting of Shaker-like potassium channels to lipid rafts. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:7443–7446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor S, Sabharanjak S, Maxfield F. Cholesterol-dependent retention of GPI-anchored proteins in endosomes. EMBO Journal. 1998;17:4626–2638. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G, Parenti M, Magee AI. The dynamic role of palmitoylation in signal transduction. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1995;20:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu FT, Callaghan JM, Steele-Mortimer O, Stenmark H, Parton RG, Campbell PL, McCuskey J, Yeo J-P, Tock EPC, Toh B-H. EEAl, an early endosome-associated protein; EEAl is a conserved α-helical peripheral membrane protein flanked by cysteine “fingers” and contains a calmodulin-binding IQ motif. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270:13503–13511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliferenko S, Paiha K, Harder T, Gerke V, Schwarzler C, Schwarz H, Beug H, Gunthert U, Huber LA. Analysis of CD44-containing lipid rafts: recruitment of annexin II and stabilization by the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;146:843–854. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowski J, Grinstein S. Na+/H+ exchangers of mammalian cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;272:22373–22376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek D, Berryman M, Bretscher A. Identification of EBP50: A PDZ-containing phosphoprotein that associates with members of the ezrin-radixin-moesin family. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;139:169–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodal SK, Skretting G, Garred O, Vilhardt F, van Deurs B, Sandvig K. Extraction of cholesterol with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin perturbs formation of clathrin-coated endocytic vesicles. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1999;10:961–974. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Rietveld A, Wilk T, Simons K. Influenza viruses select ordered lipid domains during budding from the plasma membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:2038–2044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Roth MG, Simons K. Interaction of influenza virus haemagglutinin with sphingolipid-cholesterol membrane domains via its transmembrane domain. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:5501–5508. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiffele P, Verkade P, Fra AM, Virta H, Simons K, Ikonen E. Caveolin-1 and -2 in the exocytic pathway of MDCK cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1998;140:795–806. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder R, London E, Brown D. Interactions between saturated acyl chains confer detergent resistance on lipids and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins: GPI-anchored proteins in liposomes and cells show similar behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1994;91:12130–12134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2001;1:31–39. doi: 10.1038/35036052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele C, Hannah MJ, Fahrenholz F, Huttner WB. Cholesterol binds to synaptophysin and is required for biogenesis of synaptic vesicles. Nature Cell Biology. 1999;2:42–49. doi: 10.1038/71366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade JB, Lee AJ, Liu J, Ecelbarger CA, Mitchell C, Bradford AD, Terris J, Kim G-H, Knepper MA. UT-A2: a 55-kDa urea transporter in thin descending limb whose abundance is regulated by vasopressin. American Journal of Physiology – Renal Physiology. 2000;278:F52–62. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.1.F52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi S, Shigekawa M, Pouyssegur J. Molecular physiology of vertebrate Na+/H+ exchangers. Physiological Reviews. 1997;77:51–74. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Donowitz M, Shenolikar S. NHERF associations with sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3) and ezrin are essential for cAMP-mediated phosphorylation and inhibition of NHE3. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6123–6129. doi: 10.1021/bi000064m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Amemiya M, Peng Y, Moe OW, Preisig PA, Alpern RJ. Acid incubation causes exocytic insertion of NHE3 in OKP cell. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology. 2000;279:C410–419. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.2.C410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun CH, Lamprecht G, Forster DV, Sidor A. NHE3 kinase A regulatory protein E3KARP binds the epithelial brush border Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 and the cytoskeletal protein ezrin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:25856–25863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shao J-S, Xie Q-M, Alpers DH. Immunolocalization of alkaline phosphatase and surfactant-like particle proteins in rat duodenum during fat absorption. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:478–488. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wiederkehr MR, Fan, L Collazo RL, Crowder LA, Moe OW. Acute inhibition of Na/H exchanger NHE3 by cAMP. Role of protein kinase A and NHE3 phosphoserines 552 and 605. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:3978–3987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zizak M, Lamprecht G, Steplock D, Tariq N, Shenolikar S, Donowitz M, Yun CH, Weinman EJ. cAMP-induced phosphorylation and inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE3) is dependent on the presence but not the phosphorylation of NHERF. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:24753–24758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]