Abstract

The ductus arteriosus (DA) undergoes rapid closure after birth as pulmonary circulation is established. The involvement of endothelin-1 (ET1) in this closure mechanism is controversial.

The effect of ATZ1993 (ATZ), a non-peptide antagonist for the ETA and ETB receptors, on postnatal closure and O2-induced contraction of the rat DA was investigated both in vivo and in vitro. Rat pups were delivered by Caesarean section and were given ATZ intraperitoneally. The minimum external DA diameter and the extent of DA constriction in vivo were evaluated at 2.5 h after birth. ATZ caused a dose-dependent inhibition of DA closure in vivo. When rat pups were given ATZ at 2.5 h after birth, re-opening of the DA was observed.

In vitro, ATZ also caused a marked inhibition of O2-induced and ET1-induced DA contractions as did BQ123, an ETA-specific antagonist. In contrast, sarafotoxin S6c, an ETB-specific agonist, did not cause DA contraction and BQ788, an ETB-specific antagonist, did not affect O2-induced DA contraction.

In conclusion, ET1 and its cognate receptor ETA may play a physiological role in the postnatal closure of the rat DA in vivo.

The ductus arteriosus (DA) is a shunt vessel that, in the fetal period of some animals including mammals, connects the pulmonary artery (PA) and systemic circulation, bypassing the unexpanded lungs. After birth, the DA is exposed to an increase in O2 concentration in the blood and undergoes rapid closure as the pulmonary circulation is established. Two major factors are thought to be involved in the closure: an attenuation of dilator activity and an increase of endogenous constrictor activity (Smith, 1998).

Endothelin-1 (ET1) has been suggested as a likely candidate to mediate O2-induced DA constriction (Coceani et al. 1992; Smith, 1998). However, the role of ET1 is still controversial. One group has provided several lines of evidence supporting a role for ET1 in DA closure (Coceani et al. 1989; Coceani & Kelsey, 1991). However, other work, employing ET receptor blockade, did not support a role for ET1 in the closure of the DA after birth (Fineman et al. 1998). Recently, Coceani et al. (1999) have reported that O2-induced contraction was absent in the DA isolated from ET receptor (ETA)-null mice, but that closure of the DA after birth was not affected in the ETA-null mice. The role of ET1 and/or the extent of ET1 involvement in physiological closure of the DA after birth therefore remains an open question.

To further address this question, we used ATZ1993 (ATZ), an orally active non-peptide antagonist for the ETA and ETB receptors (Azuma et al. 1999), to investigate the contribution of the ET system to the postnatal closure and O2-induced contraction of the rat DA in vivo and in vitro.

METHODS

Animals

All experiments were carried out following the guidelines produced by the Ethics Committee of our institute, which conform with the American National Institutes of Health guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Female Wistar rats, 10-12 weeks of age at the time of mating, were housed individually in breeding cages with free access to a normal diet and water. The day on which a vaginal plug was found was designated as day 0 of gestation. On the morning of day 21 of gestation, pups were delivered by Caesarean section from dams killed by decapitation.

In vivo study

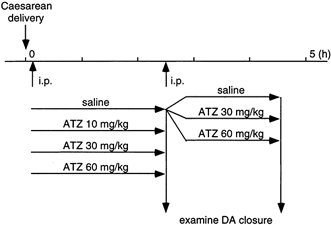

After delivery, pups were rinsed quickly in a warm water bath and were placed in a humidified chamber at 37 °C for 10 min. The pups were weighed and given an intraperitoneal injection of 100 μl (6 g)−1 body weight of saline alone or saline with ATZ at doses of 10, 30 or 60 mg kg−1. The pups were maintained in the chamber for 2.5 h after birth, then decapitated and examined for closure of the DA. In another series of experiments, ATZ was intraperitoneally administered (30 or 60 mg kg−1) at 2.5 h after birth; 2 h later (4.5 h after birth) the pups were decapitated and examined for the re-opening of the DA. These in vivo experimental protocols are summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. In vivo experimental protocol.

On the morning of day 21 of gestation, newborn pups were obtained by Caesarean delivery. The pups were given an intraperitoneal injection of either saline alone (control group) or saline with ATZ as described in Methods (final dose of ATZ was 10, 30 and 60 mg kg−1 body weight). The closure of DA was examined at 2.5 h after birth. Some of the control pups were further injected with saline alone or saline plus ATZ (30 and 60 mg kg−1 body weight) at 2.5 h after birth. These pups were decapitated at 4.5 h after birth to examine the re-opening of DA.

The thorax was opened and the aortic arch and pulmonary trunk were dissected out under a dissecting microscope. The minimum external diameter of the DA and the maximum external diameter of the common PA were measured with a calibrated microscope. The average minimum external diameter of the control DA at 2.5 h after birth was 310 μm and the standard deviation was 30 μm (n = 11). We defined parts of the DA with an external diameter greater than 400 μm as unconstricted parts for the following two reasons. Firstly, if we assume a normal distribution, 3 standard deviations above the mean falls outside the 99 percentile area; secondly, a patent DA at 2.5 h after birth always has a minimum external diameter greater than 400 μm (Table 1 and data not shown). The extent of the constricted DA was estimated. We took a DA as patent when blood passage through it was visualized upon applying pressure to the PA with forceps.

Table 1.

Effect of ATZ on DA closure at 2.5 h after birth

| Diameter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATZ (mg kg-1) | n | DA (μm) | PA (μm) | Ratio | Length of constricted DA (μm) | Patency |

| 0 | 11 (3) | 310 ± 10 | 730 ± 10 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 990 ± 30 | 0/11 |

| 10 | 13 (3) | 380 ± 10* | 820 ± 20* | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 640 ± 80* | 5/13 |

| 30 | 15 (4) | 440 ± 10* | 820 ± 20* | 0.54 ± 0.01* | 360 ± 80* | 14/15* |

| 60 | 13 (4) | 550 ± 10* | 820 ± 20* | 0.67 ± 0.02* | 0* | 13/13* |

ATZ was intraperitoneally administered to pups 10 min after Caesarean delivery and DA closure was evaluated at 2.5 h after birth as described in Fig. 1 and Methods. The number of pups (n) in each group is shown, with the number of litters in parentheses. The minimum external diameter of DA and the maximum external diameter of PA were measured and DA/PA diameter ratios were calculated. The extent of DA with diameter less than 400 μm was estimated as the length of constricted DA. The number of pups that had patent DA out of the total number of pups is given. An asterisk indicates that the value is significantly different from that of the control group (no ATZ, P < 0.01).

In vitro study

Immediately after delivery, pups were decapitated and soaked in ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit solution (composition (mm): NaCl 112, KCl 5.9, MgCl2 1.2, CaCl2 2, NaHCO3 25, NaH2PO4 1.2 and glucose 11.5) gassed with 5 % CO2-95 % N2. The thorax was opened to remove the heart and major vessels en bloc under a dissecting microscope. The DA and PA were dissected out and trimmed at the level where the two pulmonary arteries branched out, resulting in one DA ring and one PA ring from each pup. These operations were done in ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit solution gassed with 5 % CO2-95 % N2. The specimen was mounted in an assay chamber of a Micro Easy Magnus UC-5A (UFER Medical Instrument, Kyoto, Japan). The chamber was filled with Krebs-Henseleit solution which was continuously gassed with 5 % CO2-95 % N2 at 37 °C. A resting tension of 1 mN was initially applied and the responses were recorded isometrically through force displacement transducers (T7-8-240, Orientec, Tokyo, Japan). In preliminary experiments, we confirmed that the resting tension was optimal because 60 mm KCl produced a maximum contraction (data not shown). All preparations were equilibrated for 60 min, followed by a test contraction with 60 mm KCl. Samples were then pretreated with antagonists for 15 min, then exposed either to 5 % CO2-95 % O2 or to increasing concentrations of ET1 in a cumulative fashion under an atmosphere of 5 % CO2-95 % N2. At the end of each experiment, samples were dilated by the addition of 0.1 mm papaverine to obtain the zero tension value, in relation to which all contractile responses were normalized.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means ±s.e.m. Concentration-response data for ET1-induced contractions were analysed with the Prism program (GraphPad software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA, Fisher's exact probability test or Student's t test.

Materials

The following chemicals were used: human ET1 (Peptide Institute Inc., Osaka, Japan), sarafotoxin S6c (S6C; ETB-specific agonist) (Peptide Institute Inc.), BQ123 (ETA-specific antagonist; Peptide Institute Inc.), BQ788 (ETB-specific antagonist; Peptide Institute Inc.), 3-carboxy-4,5-dihydro-1-[1-(3-ethoxyphenyl)propyl]-7-(5-pirimidinyl)methoxy-[1H]-benz[g]indazole (ATZ1993; Teikoku Hormone MFG, Kawasaki, Japan), 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) and papaverine HCl (Nacalai Tesque). ATZ was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide and diluted in saline, and sonicated just before injection.

RESULTS

Inhibition of DA closure by ATZ in vivo

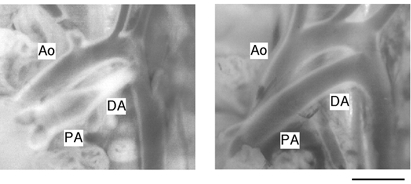

The average body weight and the number of pups in each group was 5.1 ± 0.1 g n = 11, 5.1 ± 0.1 g n = 13, 5.1 ± 0.1 g n = 15 and 5.2 ± 0.2 g n = 13 for the control, 10 mg kg−1, 30 mg kg−1 and 60 mg kg−1 ATZ group, respectively. There was no significant difference in body weight among the groups. Three out of 18 and 6 out of 19 pups treated with 30 and 60 mg kg−1 ATZ, respectively, died within 2.5 h after birth. Because all pups that died had fully patent DAs, the persistent DA opening was thought to be the cause of death, as has previously been observed in prostaglandin receptor (EP4)-deficient mice (Nguyen et al. 1997; Segi et al. 1998). Data were obtained only from pups that were alive at 2.5 h after birth. The DA, which has a similar diameter (800 ± 10 μm, n = 9) to the PA just after birth, underwent a complete closure at 2.5 h after birth. ATZ treatment prevented this DA closure after birth in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1). Photographs of representative tissues are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Morphology of DA.

Photographs of representative cases are shown. Rat pups were given saline alone (left) or saline with ATZ (60 mg kg−1 body weight) 10 min after birth (right) and were examined for DA closure at 2.5 h after birth as described in Methods. Ascending aorta (Ao), pulmonary artery (PA) and ductus arteriosus (DA) are indicated. Scale bar, 1 mm.

Re-opening of DA by ATZ in vivo

Next, we tested the ability of ATZ to reverse DA closure. The body weight of the pups was not significantly different among the groups (data not shown). ATZ (30 or 60 mg kg−1) caused re-opening of DA within 2 h when administered at 2.5 h after birth (Table 2). However, ATZ was not as effective in re-opening the DA as it was in preventing the closure of DA. In addition, when 60 mg kg−1 ATZ was administered at 3 h after birth, re-opening of the DA occurred inconsistently (data not shown).

Table 2.

Effect of ATZ on re-opening of DA after birth

| Diameter | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATZ (mg kg-1) | n | DA (μm) | PA (μm) | Ratio | Length of constricted DA (μm) | Patency |

| 0 | 19 (4) | 320 ± 10 | 780 ± 20 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 870 ± 40 | 07/19 |

| 30 | 19 (4) | 400 ± 10* | 810 ± 10 | 0.50 ± 0.01* | 640 ± 80 | 6/19* |

| 60 | 19 (4) | 430 ± 20* | 820 ± 10 | 0.53 ± 0.02* | 290 ± 70* | 14/19* |

ATZ was administered 2.5 h after birth and DA closure was evaluated at 4.5 h after birth as described in Methods. Data are shown as in Table 1. An asterisk indicates that the value is significantly different from that of control group (P < 0.01).

DA contraction in vitro and the effect of ATZ

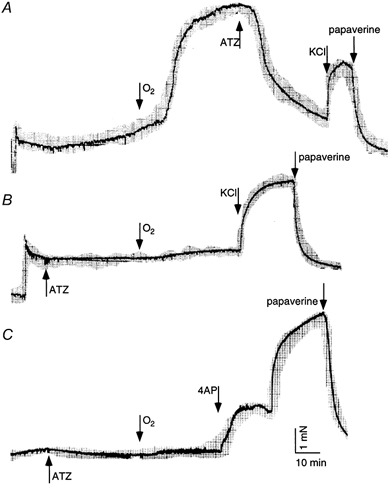

A representative recording of O2-induced DA contraction is shown in Fig. 3A. ATZ at 0.5 μm reversed (Fig. 3A) or inhibited (Fig. 3B and C) O2-induced DA contraction when it was applied during or before the exposure to O2, respectively. The contractile responses of the DA and PA under hypoxic conditions, and the effects of ATZ and other antagonists on O2-induced contraction are summarized in Fig. 4A. The administration of 0.1 μm S6C did not increase the tension in either artery. In contrast, 0.1 μm ET1, 60 mm KCl and 10 mm 4-AP, concentrations that cause a maximal effect for each agonist (Fig. 4B and data not shown), induced contractions in these arteries. Among these three constrictors, 4-AP, a K+ channel inhibitor, evoked the strongest DA contraction, which was comparable with that induced by O2 (Fig. 4A). In addition, the 4-AP-induced contraction showed a two-phase pattern in the DA (Fig. 3C). In contrast to its effect on the DA, O2 did not induce PA contraction. The O2-induced DA contraction was inhibited by pretreatment with ATZ in a concentration-dependent manner. BQ123 also inhibited, but BQ788 did not affect, the O2-induced DA contraction. The 4-AP-induced DA contraction was still observed under conditions in which the O2-induced DA contraction was inhibited by the presence of 0.5 μm ATZ (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Contractile response of DA in vitro and the effect of ATZ.

Representative recordings of O2-induced DA contraction are shown from 3-8 independent experiments. The bubbling gas was switched from 5 % CO2-95 % N2 to 5 % CO2-95 % O2 as indicated. ATZ at 0.5 μm reversed (A), or inhibited (B and C) O2-induced DA contraction. At the end of the experiments, contraction by 60 mm KCl (A and B) or by 10 mm 4-AP (C) and subsequent relaxation by 0.1 mm papaverine were tested. Scale bars in C apply to all traces.

Figure 4. Contractile response of DA and PA in vitro and the effect of ATZ.

A, the contraction of vessels was monitored in the presence of S6C (0.1 μm), ET1 (0.1 μm), KCl (60 mm) and 4-AP (10 mm) in hypoxic conditions (5 % CO2-95 % N2) and with O2 (5 % CO2-95 % O2) as described in Methods. Pretreatment with ATZ (0.01, 0.1 or 0.5 μm) or BQ123 (3 μm) inhibited, but that with BQ788 (3 μm) did not affect the O2-induced DA contraction. Asterisks indicate statistically significant inhibition compared to O2 alone (P < 0.01). Data were obtained from 4-8 independent experiments. B, DA contraction was studied under hypoxic conditions (5 % CO2-95 % N2) with cumulative addition of ET1 (1-300 nm) and the contractile force was normalized to that induced by KCl (60 mm) in the same DA at the beginning of the experiment as described in Methods. DA was incubated without (control) or with ATZ (0.01, 0.1 or 0.5 μm) prior to ET1 addition and the basal tension (0 nm ET1) was estimated from the papaverine-induced zero tension as described in Methods. Asterisks indicate that ATZ at 0.1 and 0.5 μm caused a significant rightward shift of the response curves from the control (P < 0.05 and < 0.01, respectively). Data were obtained from 3-10 independent experiments.

The concentration-dependent inhibitory effect of ATZ on ET1-induced DA contraction under hypoxic conditions is shown in Fig. 4B; the contraction induced by 60 mm KCl was taken as 100 %. The pEC50 values were 7.5 ± 0.3, 7.4 ± 0.2, 7.2 ± 0.2 and 6.0 ± 0.8 for the control, 0.01 μm, 0.1 μm and 0.5 μm ATZ samples, respectively. ATZ treatment at 0.1 and 0.5 μm resulted in a significant rightward shift of the concentration-response curves (P < 0.05 and < 0.01, respectively).

The basal tension of the DA preparation slightly increased even in the absence of added O2 during the equilibration period (Figs 3, 4A first column and 4B). This increase in tension was reduced by the addition of ATZ (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4B). The PO2 in Krebs-Henseleit solution bubbled with 5 % CO2-95 % N2 was approximately 4 kPa, which would have been high enough to induce slight DA constriction (Coceani et al. 1986).

DISCUSSION

The closure of the DA is a critical event in the perinatal period of mammals to switch the fetal circulation to the adult status as pulmonary circulation and respiration are established. Both intrauterine drug-induced closure (Van den Veyver & Moise, 1993) and delayed/failed closure (patent ductus arteriosus) (Radtke, 1998) have serious consequences. Prostaglandin E2 has been shown to be a major physiological dilator of the DA and its withdrawal at birth has been thought to facilitate closure of the DA (Smith, 1998). It has been established that an increase in O2 concentration in the blood after birth triggers DA closure. However, the mediator(s) of the constrictor effect of O2 remains the subject of debate.

We employed ATZ, a non-peptide antagonist for ETA and ETB receptors (Azuma et al. 1999), to examine the role of ET1 in the DA closure in vivo. Administration of ATZ to rat neonates just after birth resulted in the inhibition of DA closure (Table 1 and Fig. 2). In addition, administration of ATZ at 2.5 h after birth, when the DA closure was nearly complete (Hornblad & Larsson, 1967), caused a re-opening of the closed DA (Table 2). In vitro experiments (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4A) demonstrated that the DA but not the PA exhibited O2-induced contraction, which appeared to be mediated by the ETA receptor, because an ETB-specific agonist, S6C, did not elicit the contraction and because an ETB-specific antagonist, BQ788, had no effect on the O2-induced contraction. In contrast, an ETA-specific antagonist, BQ123, inhibited the O2-induced DA contraction. ATZ also reversed the O2-induced DA contraction. Finally, ATZ inhibited the ET1-induced DA contraction (Fig. 4B). These lines of evidence suggest that physiological DA closure after birth in the rat is mediated by the ET1-ETA system. However, the inhibitory effect of 0.1 μm ATZ on the ET1-induced contraction appears to have less impact than the effect of the antagonist on the O2-induced DA contraction. One possibility is that the susceptibility of the DA to ET1 and other agents may be largely enhanced by an increase in O2 tension. Thus, an equivalent DA contraction might be induced by less ET1 in hyperoxic conditions than in hypoxic conditions, resulting in a more potent inhibitory effect of ATZ in hyperoxic conditions.

Our results are in agreement with reports by Coceani and associates (Coceani et al. 1989, 1992; Coceani & Kelsey, 1991). However, Fineman et al. (1998) reported that an ETA receptor antagonist (PD-156707) did not inhibit postnatal lamb DA closure in vivo until 5 h after birth and did not block O2-induced DA contraction in vitro, although the ET antagonist blocked DA contraction induced by exogenous ET1 in vitro. Recently, Michelakis et al. (2000) also reported that BQ123 did not inhibit O2-induced DA contraction in human DA tissues in vitro. This discrepancy may be due to species differences in the mechanism of DA closure. For instance, DA closure in the rat is complete within the first few hours after birth (Hornblad & Larsson, 1967), in contrast with lambs or humans in which the DA closes more slowly (Hornblad et al. 1969; Smith, 1998). The closure of the DA is probably governed by a balance of two mechanisms: withdrawal of relaxing influence(s) and promotion of O2-linked contractile influence(s). The relative importance of relaxant and constrictor mechanisms may vary between species and, in any species, at different intervals during the early neonatal period. Alternatively, it may be due to physicochemical characteristics of the drugs used; differences in the solubility or lipophilicity affect the accessibility to target tissues. These methodological differences could potentially also play a role in the apparently different findings in tissues derived from the same species.

Coceani et al. (1999) recently reported that in ETA-null mice, the genomic defect did not inhibit postnatal DA closure in vivo, although the contractile response of the DA from the ETA-null mice to O2 or exogenous ET1 in vitro was absent. One possible explanation for these results is that an alternative mechanism, such as the reduction of prostaglandin E2 function, must compensate for the absence of ETA to cause DA closure after birth.

Recently, Takizawa et al. (2000) reported that in rats an ET antagonist, TAK-044, can prevent prenatal indomethacin- or methylene blue-induced DA contraction in utero. Taken together with our results, these data suggest that ET1 is probably a physiological constrictor of the DA in the rat.

Several reports have suggested that DA closure is caused in part by O2-induced inhibition of K+ channels, which leads to depolarization of the membrane potential, which in turn increases Ca2+ influx through voltage-operated Ca2+ channels, resulting in DA contraction (Nakanishi et al. 1993; Tristani et al. 1996; Michelakis et al. 2000). However, we suggest that inhibition of the K+ channel is not the initiator, at least for O2-induced DA contraction, for the following two reasons. Firstly, K+ channels are ubiquitously distributed in the vascular system and are thus unlikely to initiate DA-specific O2-induced contraction. In the PA, in fact, 4-AP, a K+ channel blocker, induced a stronger contraction than that induced by KCl (Fig. 4A). Secondly, 4-AP caused DA contraction, even when O2-induced DA contraction was completely inhibited by ATZ (Fig. 3C). However, our results do not exclude the possibility that K+ channels may be involved in the signalling pathway downstream from the ET1-ETA system in O2-induced DA contraction.

It is believed that DA closure has two phases: first, functional reversible closure and second, permanent irreversible closure. It has been reported that interactions in the DA between cell adhesion molecules such as fibronectin on the surface of smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix components such as hyaluronan are required to complete the remodelling of the DA (Boudreau et al. 1991; Mason et al. 1999). In our experiments, administration of ATZ to rat neonates at 2.5 h but not at 3 h after birth induced consistent re-opening of the DA, suggesting that in the rat the DA becomes refractory to ATZ at about 3 h after birth. We speculate that in the rat the functional closure of the DA is mediated by ET1, secretion of which is accelerated specifically in DA tissue by an increase in blood O2 tension (Coceani & Kelsey, 1991) after birth, and that the ET1-induced constriction is followed by remodelling of the DA to perpetuate the closure. In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the postnatal DA closure, triggered by an increase in blood O2, is mediated by ET1-ETA in the rat.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and by a grant from the Smoking Research Foundation of Japan. M.D.H. was supported by an Invitation Fellowship (FY2000) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

References

- Azuma H, Sato J, Masuda H, Goto M, Tamaoki S, Sugimoto A, Hamasaki H, Yamashita H. ATZ1993, an orally active and novel nonpeptide antagonist for endothelin receptors and inhibition of intimal hyperplasia after balloon denudation of the rabbit carotid artery. Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;81:21–28. doi: 10.1254/jjp.81.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau N, Turley E, Rabinovitch M. Fibronectin, hyaluronan, and a hyaluronan binding protein contribute to increased ductus arteriosus smooth muscle cell migration. Developmental Biology. 1991;143:235–247. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90074-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coceani F, Armstrong C, Kelsey L. Endothelin is a potent constrictor of the lamb ductus arteriosus. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1989;67:902–904. doi: 10.1139/y89-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coceani F, Huhtanen D, Hamilton NC, Bishai I, Olley PM. Involvement of intramural prostaglandin E2 in prenatal patency of the lamb ductus arteriosus. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1986;64:737–744. doi: 10.1139/y86-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coceani F, Kelsey L. Endothelin-1 release from lamb ductus arteriosus: relevance to postnatal closure of the vessel. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1991;69:218–221. doi: 10.1139/y91-033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coceani F, Kelsey L, Seidlitz E. Evidence for an effector role of endothelin in closure of the ductus arteriosus at birth. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1992;70:1061–1064. doi: 10.1139/y92-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coceani F, Liu Y, Seidlitz E, Kelsey L, Kuwaki T, Ackerley C, Yanagisawa M. Endothelin A receptor is necessary for O2 constriction but not closure of ductus arteriosus. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277:H1521–1531. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.4.H1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineman JR, Takahashi Y, Roman C, Clyman RI. Endothelin-receptor blockade does not alter closure of the ductus arteriosus. American Journal of Physiology. 1998;275:H1620–1626. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornblad PY, Larsson KS. Studies on closure of the ductus arteriosus. II. Closure rate in the rat and its relation to environmental temperature. Cardiology. 1967;51:242–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornblad PY, Larsson KS, Marsk L. Studies on closure of the ductus arteriosus. VII. Closure rate and morphology of the ductus arteriosus in the lamb. Cardiology. 1969;54:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason CA, Bigras, J L, O'Blenes SB, Zhou B, McIntyre B, Nakamura N, Kaneda Y, Rabinovitch M. Gene transfer in utero biologically engineers a patent ductus arteriosus in lambs by arresting fibronectin-dependent neointimal formation. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:176–182. doi: 10.1038/5538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelakis E, Rebeyka I, Bateson J, Olley P, Puttagunta L, Archer S. Voltage-gated potassium channels in human ductus arteriosus. Lancet. 2000;356:134–137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi T, Gu H, Hagiwara N, Momma K. Mechanisms of oxygen-induced contraction of ductus arteriosus isolated from the fetal rabbit. Circulation Research. 1993;72:1218–1228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.6.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M, Camenisch T, Snouwaert JN, Hicks E, Coffman TM, Anderson PA, Malouf NN, Koller BH. The prostaglandin receptor EP4 triggers remodelling of the cardiovascular system at birth. Nature. 1997;390:78–81. doi: 10.1038/36342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke WA. Current therapy of the patent ductus arteriosus. Current Opinion in Cardiology. 1998;13:59–65. doi: 10.1097/00001573-199801000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segi E, Sugimoto Y, Yamasaki A, Aze Y, Oida H, Nishimura T, Murata T, Matsuoka T, Ushikubi F, Hirose M, Tanaka T, Yoshida N, Narumiya S, Ichikawa A. Patent ductus arteriosus and neonatal death in prostaglandin receptor EP4-deficient mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1998;246:7–12. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GC. The pharmacology of the ductus arteriosus. Pharmacological Reviews. 1998;50:35–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa T, Horikoshi E, Shen MH, Masaoka T, Takagi H, Yamamoto M, Kasai K, Arishima K. Effects of TAK-044, a nonselective endothelin receptor antagonist, on the spontaneous and indomethacin- or methylene blue-induced constriction of the ductus arteriosus in rats. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 2000;62:505–509. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tristani FM, Reeve HL, Tolarova S, Weir EK, Archer SL. Oxygen-induced constriction of rabbit ductus arteriosus occurs via inhibition of a 4-aminopyridine-, voltage-sensitive potassium channel. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98:1959–1965. doi: 10.1172/JCI118999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Veyver IB, Moise KJ. Prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors in pregnancy. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. 1993;48:493–502. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199307000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]