Abstract

In the rodent cerebellum, both presynaptic CB1 cannabinoid receptors and presynaptic mGluR4 metabotropic glutamate receptors acutely depress excitatory synaptic transmission at parallel fibre-Purkinje cell synapses. Using rat cerebellar slices, we have analysed the effects of selective CB1 and mGluR4 agonists on the presynaptic Ca2+ influx which controls glutamate release at this synapse.

Changes in presynaptic Ca2+ influx were determined with the Ca2+-sensitive dyes fluo-4FF AM or fluo-3 AM. Five stimulations delivered at 100 Hz or single stimulations of parallel fibres evoked rapid and reproducible transient increases in presynaptic fluo-4FF or fluo-3 fluorescence, respectively, which decayed to prestimulus levels within a few hundred milliseconds. Bath application of the selective CB1 agonist WIN55,212-2 (1 μm) markedly reduced the peak amplitude of these fluorescence transients. This effect was fully reversed by the selective CB1 antagonist SR141716-A (1 μm).

Bath application of the selective mGluR4 agonist l-AP4 (100 μm) also caused a transient decrease in the peak amplitude of the fluorescence transients evoked by parallel fibre stimulation.

Bath application of the potassium channel blocker 4-AP (1 mm) totally prevented both the WIN55,212-2- and the l-AP4-induced inhibition of peak fluorescence transients evoked by parallel fibre stimulation.

The present study demonstrates that activation of CB1 and mGluR4 receptors inhibits presynaptic Ca2+ influx evoked by parallel fibre stimulation via the activation of presynaptic K+ channels, suggesting that the molecular mechanisms underlying this inhibition involve an indirect inhibition of presynaptic voltage-gated Ca2+ channels rather than their direct inhibition.

In the mammalian cerebellum, activation of the presynaptic type 4 metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR4) (Kinoshita et al. 1996) as well as activation of the presynaptic type 1-cannabinoid receptors (CB1) (Herkenham et al. 1991) acutely depress excitatory synaptic transmission at parallel fibre (PF)-Purkinje cell (PC) synapses (Larson-Prior et al. 1990; Levenes et al. 1998). Although the mechanisms underlying this depression are unknown, one likely hypothesis is that they involve either direct or indirect inhibition of the presynaptic P-, Q- and/or N-type voltage-gated calcium (Ca2+) channels (VGCCs) responsible for evoked release of glutamate at this synapse (Regehr & Mintz, 1994; Mintz et al. 1995; Randall & Tsien, 1995). Indeed, CB1 receptors inhibit N- and Q-type VGCCs and enhance an inwardly rectifying potassium (K+) channel in expression systems (Mackie & Hille 1992; Caufield & Brown 1992; Mackie et al. 1995; Childers & Deadwyler, 1996). In cultured hippocampal neurones, cannabinoids also inhibit N- and P/Q-type VGCCs and enhance an A-type K+ current (Deadwyler et al. 1995; Twitchell et al. 1997). If such mechanisms are also operational at PF terminals, they could account for the reduction in the probability of glutamate release at PF-PC synapses following the activation of presynaptic CB1 receptors (Levenes et al. 1998). The same holds for presynaptic group III metabotropic glutamate receptors, the activation of which also reduces the probability of neurotransmitter release at central synapses (see references in Anwyl, 1999), by mechanisms including the activation of a 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)-sensitive K+ current (Cochilla & Alford, 1998).

The aim of the present study was to investigate the mechanisms by which mGluR4 and CB1 receptor activation depress excitatory synaptic transmission at PF-PC synapses. Using rat cerebellar slices we first employed fluorometric methods to quantify the effects of presynaptic mGluR4 and CB1 receptor activation on the depolarisation-induced Ca2+ transients recorded in PFs. We next determined whether or not the above-said effects could be abolished in the presence of the K+ channel blocker 4-AP. Our results show that activation of presynaptic mGluR4 and CB1 receptors indirectly inhibits presynaptic VGCCs by modulating presynaptic K+ channel activity. These results are in keeping with previously reported observations at other central synapses (Cochilla & Alford 1998; Robbe et al. 2001).

METHODS

All procedures used conformed to CNRS guidelines. Male Sprague-Dawley rats, aged 17-26 days, were stunned and decapitated. Coronal or sagittal slices, 200-250 μm thick, were prepared from the vermis of the cerebellum with a vibroslicer and incubated at room temperature in saline solution saturated with 95 % O2-5 % CO2. The saline solution contained (mm): NaCl, 124; KCl, 3; NaHCO3, 24; KH2PO4, 1.15; MgSO4, 1.15; CaCl2, 2; glucose, 10; 330 mosmol l−1, pH 7.35 at 25 °C. The recording chamber was perfused at a rate of 2 ml min−1 with this oxygenated saline solution and the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline methiodide (10 μm, Sigma Aldrich, St Quentin Fallavier, France).

Drugs were added directly to the perfusate. l-2-Amino-4-phosphobutyric acid (l-AP4) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) were purchased from Sigma (Sigma Aldrich, St. Quentin Fallavier, France); WIN55,212-2 was purchased from Tocris (Illkirch, France); SR141716-A was generously provided by Sanofi-Recherche (Montpellier, France). Stocks of WIN55,212-2 and SR141716-A were prepared in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and added to the perfusate at the desired concentration (final concentration of DMSO 0.1 %).

Calcium-sensitive fluorometric measurements

In coronal slices, parallel fibres (PFs) were labelled by local application of a saline solution containing the membrane-permeant form of the fluorescent low affinity calcium-sensitive dye fluo-4FF AM (100 μm, Molecular Probes) according to the procedure described by Regher & Alturi (1995). Briefly, PFs were loaded by continuous local application of the fluorescent calcium indicator using a delivery pipette containing the dye and a suction pipette placed near the delivery site to restrict the diffusion of the dye to a small area of the slice. The fluorescent signal was recorded at 28 °C through a 20 μm × 50 μm window placed in the molecular layer on the visible narrow band of labelled PFs, approximately 400-700 μm away from the loading site. At a such distance, only the loaded fibre tracts were visible in the recording window; no other labelled structures were detectable. A saline-filled electrode placed between the loading site and the recording site was used to activate PFs located in the recording window. Calcium-sensitive fluorometric changes were measured through the × 40 water-immersion objective of an upright microscope (Nikon). The dye was loaded for 30 min and 45 min later the first measurements were taken. This delay allowed sufficient time to rinse unloaded dye and for the uptaken dye to diffuse along PFs. Excitation light obtained from a 100 W xenon lamp was gated with an electromechanical shutter (UniBlitz, Rochester, NY, USA), and the area of illumination was defined by an iris diaphragm. The epifluorescence excitation was at 485 ± 22 nm and the emitted light was collected by a photometer through a barrier filter at 530 ± 30 nm. The output of the photometer was filtered at 200 Hz. Fluorometric measurements were analysed on- and off-line using the Acquis1 computer program (Biologic). Since this single wavelength method does not permit determination of absolute free calcium levels, the fluorescence data corrected for dye bleaching and background fluorescence were expressed as changes in ΔF/F, where F is the baseline fluorescence intensity, and ΔF is the change induced by PF activation. A 100 Hz train of five electrical PF stimulations was used to generate fluorescence changes recordable in the defined window. In some experiments, the PF volley was also recorded as an extracellular field potential (Eccles et al. 1967), with a saline-filled electrode placed in the molecular layer close to the fluorescence recording site. In another series of experiments a single stimulus was used to generate optical fluorescence signals from labelled PFs. In this case, instead of fluo-4FF AM, the relatively high affinity calcium-dye fluo-3 AM (100 μm, Molecular Probes) was used to detect fluorescence changes evoked by such PF activation. Both dyes employed the same labelling procedures and measures of fluorescence levels.

Electrophysiology

Recordings of Purkinje cells from sagittal slices were performed using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique at a somatic level, with an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Axon Instruments). Patch pipettes (2-3.5 MΩ) were filled with an internal solution containing (mm): KCl, 140; NaCl, 8; Hepes, 10; EGTA, 5, CaCl2, 0.5, ATP-Mg, 2; pH 7.3 with KOH; 300 mosmol l−1. Cells were held at a membrane potential of -70 mV. PFs were stimulated with a saline-filled monopolar electrode at 0.033 Hz and the PF-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were recorded and analysed as previously described (Goossens et al. 2001).

RESULTS

At the recording site, 400-700 μm away from the fill site (see Methods), a train of five stimulations of the PF tract induced reproducible transient increases in presynaptic fluorescence, which returned to resting levels within a few hundred milliseconds (a in Fig. 1A–C). The peak amplitude of the fluorescence transients was 4.9 ± 0.3 % (ΔF/F) (mean ± s.e.m., n = 33).

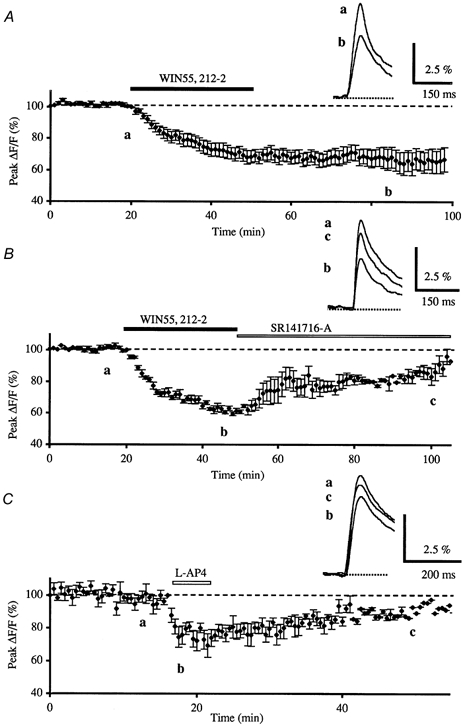

Figure 1. Effects of WIN55,212-2 and l-AP4 on presynaptic calcium influx and reversal of WIN55,212-2 effects by subsequent application of SR141716-A.

A, normalised amplitudes of peak fluo-4FF fluorescence transients (ΔF/F) evoked by five stimulations (delivered at 100 Hz) of the parallel fibres recorded as a function of time, before, during and after bath application of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm, horizontal filled bar) for 30 min. Each point is the mean ± s.e.m. of 10 separate experiments. The inset displays superimposed averaged fluorescence changes in one of these experiments, recorded at the indicated times. Each trace is an average of 10 consecutive trials. B, the inhibitory effect of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm) on the normalised amplitude of peak fluorescence transients was reversed by bath application of the selective CB1 antagonist SR141716-A (1 μm, n = 3). Inset as in A. C, effect on the normalised amplitudes of peak fluorescence transients of bath application of l-AP4 (100 μm) for 5 min (n = 7). Inset as in A.

To determine whether the activation of presynaptic CB1 receptors involved the inhibition of the presynaptic VGCCs, the effect of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm), a powerful CB1 receptor agonist, was examined. Presynaptic fluorescence transients elicited by PF stimulations were inhibited by bath application of this compound as compared to those recorded in control conditions (Fig. 1A), with a resulting mean decrease in the amplitude of fluorescence transients of 32.7 ± 2.2 % (mean ± s.e.m., n = 10), 20 min after the WIN55,212-2 application. This reduction in amplitude lasted the entire duration of the recording session, probably due to the lipophilic nature of this cannabinoid agonist (Levenes et al. 1998). The WIN55,212-2-induced depression was never accompanied by detectable changes in the presynaptic volley (n = 4, not illustrated). Finally, bath application of the CB1 antagonist SR141716-A (1 μm) partially reversed the depressant effect of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm), when the latter was washed out at the same time as SR141716-A was applied (n = 3, Fig. 1B).

In order to establish whether mGluR4 receptor activation also involved an inhibition of presynaptic VGCCs, the effects of l-AP4, a group III metabotropic agonist, were studied. Bath application of l-AP4 (100 μm) for 5 min transiently inhibited presynaptic fluorescence transients elicited by PF stimulations by 25.9 ± 1.8 % (n = 7) (Fig. 1C).

Taken together, these results are consistent with an inhibitory action of WIN55,212-2 and l-AP4 on presynaptic Ca2+ influx, but they do not establish whether these inhibitory effects are due to direct inhibition of the presynaptic Ca2+ channels or result from an indirect inhibition via activation of K+ channels, since these channels might be modulated by CB1 activation (Deadwyler et al. 1993, 1995; Mackie et al. 1995; Robbe et al. 2001) or by l-AP4-sensitive mGluR activation (Cochilla & Alford 1998).

To clarify this issue, and taking into account our assumption that activation of presynaptic CB1 and mGluR4 receptors at PF-PC synapses reduces glutamate release by mechanisms including activation of K+ channels which inhibit presynaptic Ca2+ influx, we have used bath application of 4-AP, which blocks A-like K+ currents in different cell types (Mitgaard et al. 1993; Bossu et al. 1996). In order to determine the concentration of this K+ channel blocker necessary to study the mechanism underlying the inhibitory action of WIN55,212-2 and l-AP4 on presynaptic Ca2+ influx, we first tested the ability of 4-AP to block the depressant effects of WIN55,212-2 or l-AP4 on the excitatory synaptic transmission at PF-PC synapses.

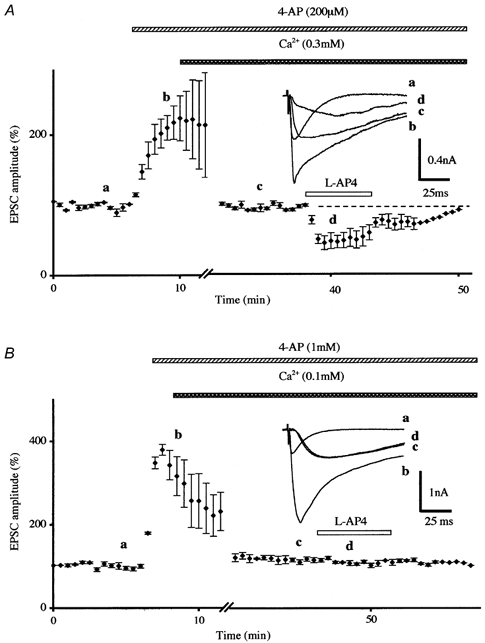

In the presence of 200 μm 4-AP, the resulting mean increase on the amplitude of PF-mediated EPSCs was 244.7 ± 40.4 % (n = 7) and was brought back to control levels after lowering the extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 2 to 0.3 mm (with a corresponding increase in Mg2+ concentration to maintain the osmolarity of the external medium) (Fig. 2A). In these conditions, a clear decrease in the amplitude of PF-mediated EPSCs was seen with bath application of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm) averaging 48.3 ± 3.1 % (n = 3, not illustrated) or l-AP4 (100 μm) (49.9 ± 10.8 %, n = 4, Fig. 2A). In the presence of 1 mm 4-AP, the large enhancement of PF-mediated EPSC amplitude (332.2 ± 35.2 %, n = 6) was brought back to control levels after lowering extracellular Ca2+ concentration from 2 to 0.1 mm. In these conditions, and in contrast with the previous data, application of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm or 10 μm) (n = 3, not illustrated) or l-AP4 (100 μm, n = 3, Fig. 2B) had no discernable effect on PF-mediated responses. Thus, 1 mm 4-AP was used in subsequent experiments to evaluate the consequences of K+ channel inhibition on presynaptic Ca2+ influx.

Figure 2. Effects of potassium channels blockade on l-AP4-induced inhibition of parallel fibre-mediated EPSCs in low external calcium.

A, normalised amplitudes (means ± s.e.m., n = 4) of PF-mediated EPSCs as a function of time before, during bath application of 4-AP (200 μm) and during co-application of l-AP4 (100 μm) in low external calcium. Note that the large increase of PF-mediated EPSC amplitude induced by bath application of 4-AP (a → b) was eliminated by lowering the extracellular calcium concentration from 2 to 0.3 mm, in order to obtain values similar to those observed in standard medium (b → c). In these conditions, 200 μm 4-AP failed to prevent 100 μm l-AP4-induced inhibition of PF-mediated EPSCs. Insets, superimposed averaged PF-mediated EPSCs recorded in one of these experiments. Each trace is an average of 5-10 consecutive trials. Note that application of 4-AP not only increased the amplitude of PF-mediated EPSCs but also affected the kinetics of these responses. B, prevention of 100 μm l-AP4-induced transient inhibition of the normalised amplitude of PF-mediated EPSCs by prior bath application of 1 mm 4-AP in low external calcium (0.1 mm). Each point is the mean ± s.e.m. of three separate experiments. Inset as in A.

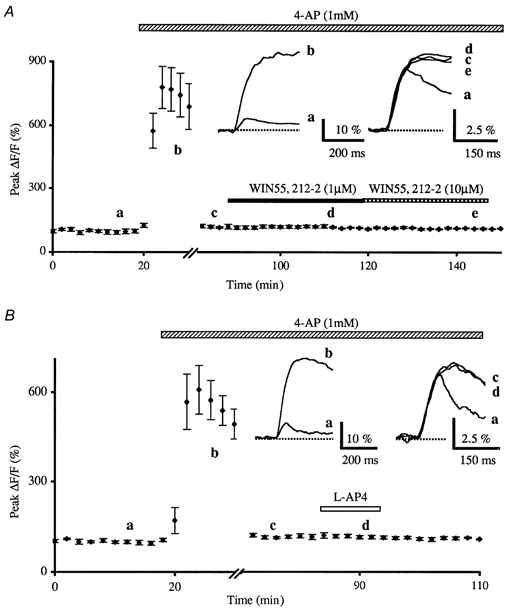

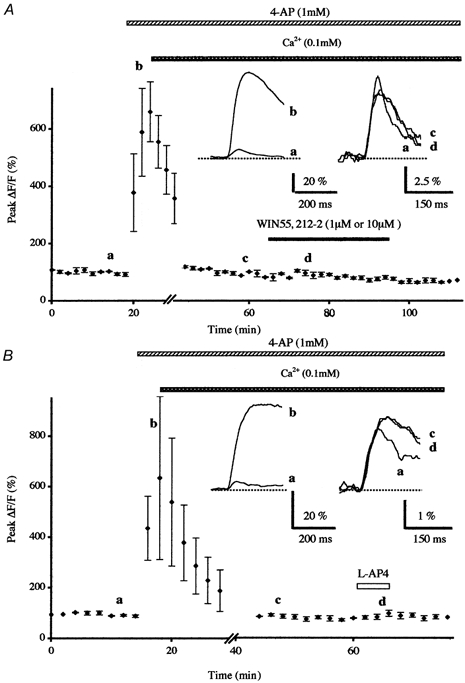

In these experiments, 4-AP did not appreciably alter the absolute fluorescence suggesting that it does not seem to sizeably affect the basal Ca2+ level in PFs (n = 23). In contrast, the amplitude and the duration of presynaptic fluorescence transients elicited by PF stimulations were largely increased, as compared to those recorded in control conditions (Figs 3 and 4). Initially, the resulting mean increase on the amplitude of fluorescence transients was 636 ± 57 % (n = 23), and it then slowly decreased to reach a plateau as long as application of 4-AP was maintained. As such in the presence of this compound, PF stimulation intensity was reduced to bring back evoked Ca2+ transient amplitudes to values similar to those seen in control medium. In such conditions, bath application of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm or 10 μm, n = 6; Fig. 3A) and l-AP4 (100 μm, n = 9; Fig. 3B) no longer had any effect on presynaptic fluorescence transients. Nevertheless, after lowering the intensity of PF stimulation to bring back evoked Ca2+ transient amplitude to control levels in the presence of 1 mm 4-AP, we cannot exclude that the smaller number of PFs activated presented a saturation of calcium handling systems, which could explain the lack of effect of WIN55,212-2 and l-AP4. To address this question, extracellular Ca2+ concentration was lowered (from 2 to 0.1 mm, with correction of Mg2+ concentration for the osmolarity) without changing the intensity of PF stimulation, in order to restore evoked Ca2+ transient amplitudes to values similar to those recorded in control medium. In these conditions WIN55,212-2 (1 μm or 10 μm, n = 4; Fig. 4A) and l-AP4 (100 μm, n = 4; Fig. 4B) had no effect on presynaptic fluorescence transients.

Figure 3. Effects of potassium channels blockade on the WIN55,212-2- and the l-AP4-induced inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx in control medium.

A, normalised amplitudes (means ± s.e.m., n = 6) of peak fluorescence transients (ΔF/F) evoked by five stimuli delivered at 100 Hz of the parallel fibres recorded as a function of time before, during bath application of 4-AP (1 mm) and during co-application of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm or 10 μm). Note that in these experiments, the large enhancement of the peak fluorescence transients amplitude induced by bath application of 4-AP (a → b) was eliminated by lowering the intensity of PF stimulation in order to obtain values similar to those seen in standard medium (b → c). In these conditions, 4-AP totally prevented the 1 μm (d) and 10 μm (e) WIN55,212-2-induced inhibition of peak fluorescence transients evoked by PF stimulation. The insets represent superimposed averaged fluorescence changes in one of these experiments, recorded at the indicated times. Each trace is an average of 10 consecutive trials. Note that application of 4-AP not only increased the amplitude of fluorescence transients but also affected the kinetic of these transients. B, prevention of 100 μm l-AP4-induced transient inhibition of the normalised amplitudes of peak fluorescence transients by prior bath application of 4-AP (1 mm). Each point is the mean ± s.e.m. of nine separate experiments. Inset as in A.

Figure 4. Effects of potassium channel blockade on the WIN55,212-2- and the l-AP4-induced inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx in low external calcium.

A, normalised amplitudes (means ± s.e.m., n = 4) of peak fluorescence transients (ΔF/F) evoked by five stimuli delivered at 100 Hz of the parallel fibres recorded as a function of time before, during bath application of 4-AP (1 mm) and during co-application of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm or 10 μm) after lowering extracellular calcium concentration from 2 to 0.1 mm. Inset, superimposed averaged fluorescence changes in one of these experiments. Note that in these conditions 4-AP totally prevented the WIN55,212-2-induced inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx. B, prevention of 100 μm l-AP4-induced transient inhibition of the normalised amplitudes of peak fluorescence transients by prior bath application of 4-AP (1 mm) in low external calcium. Each point is the mean ± s.e.m. of four separate experiments. Inset as in A.

In the present study, all the presynaptic Ca2+ transients, recorded with the low-affinity dye fluo-4FF, have been evoked in PFs by five stimulations delivered at 100 Hz. Taking into account that the electrophysiological studies on the reduction of glutamate release at PF-PC synapses after presynaptic CB1 or mGluR4 receptor activation have been done with single PF stimulations (Levenes et al. 1998 and see above), we tested the inhibitory effects of WIN55,212-2 and l-AP4 on the presynaptic Ca2+ transients evoked by single PF stimulations. The low affinity dye fluo-4FF was not suited to record the small presynaptic Ca2+ changes elicited by a single activation of PFs, and as such we employed a relatively high affinity calcium-dye, fluo-3 AM. Presynaptic fluorescence transients elicited by single PF stimulations were also inhibited by application of WIN55,212-2 (1 μm) or l-AP4 (100 μm) as compared to those recorded in control conditions with a resulting mean decrease of the amplitude of fluorescence transients of 32.7 ± 2.2 % (n = 4) and 20.8 ± 0.4 % (n = 3), respectively (not illustrated). Moreover, in the presence of 1 mm 4AP, and after lowering the extracellular Ca2+ concentration as previously described, WIN55,212-2 (1 μm, n = 3) and l-AP4 (100 μm, n = 3) no longer had any effect on the presynaptic fluorescence transients elicited by a single PF stimulation.

These results strongly suggest that indirect inhibition of presynaptic Ca2+ channels via the activation of presynaptic K+ channels accounts for both the mGluR4 and CB1 receptor-mediated inhibition of presynaptic calcium influx.

DISCUSSION

In the cerebellum, previous experiments have shown that cannabinoids inhibit excitatory synaptic transmission at PF-PC synapses by decreasing the probability of glutamate release (Levenes et al. 1998). Our findings indicate that stimulation of CB1 receptors inhibits presynaptic Ca2+ transients evoked by PFs via activation of presynaptic K+ channels, suggesting that the molecular mechanisms underlying the inhibition of these presynaptic Ca2+ are indirect. This acute effect of cannabinoid agonists is consistent with a recently published study in the mouse nucleus accumbens which demonstrates that CB1 receptor activation can reduce glutamate synaptic transmission, by modulating K+ channel activity rather than by directly modulating presynaptic VGCCs (Robbe et al. 2001). Thus, the present study brings compelling evidence for a major role of K+ channel modulation in the cannabinoid receptor-mediated inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission at PF-PC synapses, even if a direct inhibition of VGCCs cannot completely be ruled out on the basis of the present results.

Activation of group III mGluR located on presynaptic terminals depresses synaptic glutamate release in many preparations including the cerebellum (Larson-Prior et al. 1990; Conquet et al. 1994) and the lamprey spinal cord (Krieger et al. 1996). We have demonstrated here that l-AP4, a group III mGluR agonist, is ineffective in depressing the presynaptic Ca2+ influx evoked by PF stimulation in the presence of a K+ channel blocker.

In agreement with the mechanism of type III mGluR-mediated depression of neurotransmitter release reported in the lamprey spinal cord (Cochilla & Alford 1998), our data in the cerebellum are consistent with the fact that l-AP4 inhibits transmission at the PF-PC synapse by modulating presynaptic K+ channels rather than inhibiting VGCCs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Sanofi Recherche. We thank Dr Jean-Gaël Barbara for helpful comments on the manuscript and Gérard Sadoc for the Acquis1 software used in this study.

References

- Anwyl R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: electrophysiological properties and role in plasticity. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;29:83–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossu JL, Capogna M, Debanne D, McKinney RA, Gähwiler BH. Somatic voltage-gated potassium currents of rat hippocampal pyramidal cells in organotypic slice cultures. Journal of Physiology. 1996;495:367–381. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield MP, Brown DA. Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit calcium current in NG 108–15 neuroblastoma cells via a pertussis toxin-sensitive mechanism. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;106:231–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers SR, Deadwyler SR. Role of cyclic AMP in the actions of cannabinoid receptors. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1996;52:819–827. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochilla AJ, Alford S. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated control of neurotransmitter release. Neuron. 1998;20:1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conquet F, Bashir ZI, Davies CH, Daniel H, Ferraguti F, Bordi F, Franz-Bacon K, Reggiani A, Matarese V, Conde F, Collingridge GL, Crepel F. Motor deficit and impairment of synaptic plastivity in mice lacking mGluR1. Nature. 1994;372:237–243. doi: 10.1038/372237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Bennett BA, Edwards TA, Mu J, Pacheco MA, Ward SJ, Childers SR. Cannabinoids modulate potassium current in cultured hippocampal neurons. Receptors and Channels. 1993;1:121–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Mu J, Whyte A, Childers S. Cannabinoids modulate voltage sensitive potassium A-current in hippocampal neurons via a cAMP-dependent process. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1995;273:734–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Ito M, Szentagothai J. The Cerebellum as a Neuronal Machine. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M, Lynn A, Jonhson M, Melvin L, de Costa B, Rice K. Characterisation and localisation of cannabinoid receptors in rat brain: a quantitative in vitro autoradiographic study. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:563–583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00563.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens J, Daniel H, Rancillac A, van der Steen J, Oberdick J, Crepel F, De Zeeuw C, Frens MA. Expression of protein kinase C inhibitor blocks cerebellar long-term depression without affecting Purkinje cell excitability in alert mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21:5813–5823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05813.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A, Ohishi H, Nomura S, Shigemoto R, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Presynaptic localization of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR4a, in the cerebellar cortex: a light and electron microscope study in the rat. Neuroscience Letters. 1996;207:199–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger P, el Manira A, Grillner S. Activation of pharmacologically distinct metabotropic glutamate receptors depresses reticulospinal-evoked monosynaptic EPSPs in the lamprey spinal cord. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:3834–3841. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson-Prior LJ, McCrimmon DR, Slater NT. Low excitatory amino acid receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in turtle cerebellar Purkinje cells. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1990;63:637–650. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.3.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenes C, Daniel H, Soubrie P, Crepel F. Cannabinoids decrease excitatory synaptic transmission and impair long-term depression in rat cerebellar Purkinje cells. Journal of Physiology. 1998;510:867–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.867bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K, Hille B. Cannabinoids inhibit N-type calcium channels in neuroblastoma-glioma cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 1992;89:3825–3829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K, Lai Y, Wenstenbroek R, Mitchell R. Cannabinoids activate an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance and inhibit Q-type calcium currents in At20 cells transfected with rat brain cannabinoid receptor. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:6552–6561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06552.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Calcium control of transmitter release at a cerebellar synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:675–688. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midtgaard J, Lasser-Ross N, Ross WN. Spatial distribution of calcium influx in turtle Purkinje cell dendrites in vitro: Role of a transient outward current. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1993;70:2455–2469. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall A, Tsien WT. Pharmacological dissection of multiple types of calcium channel currents in rat cerebellar granule neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:2995–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02995.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr WG, Alturi P. Calcium transients in cerebellar granule cell presynaptic terminals. Biophysical Journal. 1995;68:2156–2170. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80398-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr WG, Mintz IM. Participation of multiple calcium channel types in transmission at single climbing fiber to Purkinje cell synapses. Neuron. 1994;12:605–613. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbe D, Alonso G, Duchamp F, Bockaert J, Manzoni O. Localization and mechanisms of action of cannabinoid receptors at the glutamatergic synapses of mouse nucleus accumbens. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;15:2995–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00109.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twitchell WS, Brown S, Mackie K. Cannabinoids inhibit N- and P/Q-type calcium channels in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1997;78:43–50. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]