Abstract

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is known to cause diverse subjective symptoms, in addition to those related to osteitis fibrosa cystica and kidney stones. The treatment of the disease ameliorates the subjective symptoms and improves the patients’ quality of life. In this prospective study, patients undergoing surgery for incidentally detected, mild, asymptomatic PHPT were assessed to determine whether subjective neuropsychological symptoms are improved even in patients with “asymptomatic” PHPT. From October 1995 to March 2004, 25 patients who had one or more neuropsychological symptoms preoperatively and were followed up 1 year after parathyroidectomy were enrolled. The subjective symptoms were identified using questionnaires distributed to patients; eight questions were used to determine the presence or absence of psychoneurological symptoms. Compared to their preoperative status, patients responded that their general health perceptions 1 year after surgery were improved (13 cases, 52%), unchanged (11 cases, 44%), or aggravated (1 case, 4%). There were no statistically significant differences in the patients’ responses before and after surgery with respect to individual neuropsychological symptoms, such as “tiring easily, “forgetfulness,” “decreased concentration,” “depression,” “irritability,” “uneasiness,” and “sleeplessness.” Therefore, subjective neuropsychological symptoms did not improve in otherwise asymptomatic PHPT patients following parathyroidectomy. However, patients’ questionnaire responses may not reflect their actual status as accurately as laboratory examination results. Overall, 52% of patients were subjectively satisfied with surgery; this may result from patients’ expectations of treatment.

Keywords: Asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism, Subjective symptoms, Parathyroidectomy

Introduction

Since calcium concentration is now included in the serum biochemical analyses done by multichannel autoanalyzers, it is possible to detect patients with hypercalcemia. Consequently, an increased incidence of mild cases of primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) has been noted. More than 80% of PHPT patients are essentially “asymptomatic” [1, 2]. Currently, resection of the pathologic parathyroid gland continues to be the sole therapeutic modality available for curing PHPT. However, the surgical procedure is not necessarily easy for surgeons with limited experience, particularly in certain patients with mild PHPT. Under these circumstances, several investigators [1, 3, 4] have reported, based on surveys, on the natural history of patients with asymptomatic PHPT who had been conservatively followed up. Some patients reported no signs or symptoms during observation periods of various durations, although some patients developed complications specific to PHPT that required surgery. PHPT has been known to produce diverse subjective symptoms, in addition to those related to osteitis fibrosa cystica and kidney stones. The treatment of the disease ameliorates these symptoms, which improves patients’ quality of life (QOL).

From the clinical standpoint, based on patient self-reporting after surgery, most surgeons have had the impression that parathyroidectomy improves psychological and mental deficits. This prospective study of patients undergoing surgery for incidentally detected, mild, asymptomatic PHPT determined whether subjective neuropsychological symptoms improved postoperatively in patients with asymptomatic PHPT.

Patients and methods

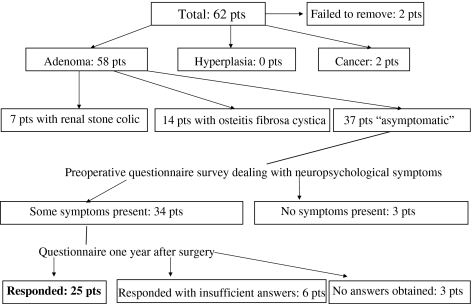

From October 1995 to March 2004, 62 patients with PHPT were treated at the Cancer Institute Hospital. All patients underwent surgery. In 60 patients, the pathological parathyroid glands were successfully removed; the pathology was adenoma in 58 patients, hyperplasia in none, and cancer in 2. Of the 58 patients whose parathyroid adenoma was removed, 7 had kidney stones and 14 had osteitis fibrosa cystica. Thirty-seven patients without any signs and/or symptoms of classic PHPT were diagnosed as “asymptomatic”, because all were incidentally found to have hypercalcemia on laboratory testing, and their subsequent serum examinations showed inappropriately elevated intact parathyroid hormone concentrations without concomitant clinical, biochemical, or radiological evidence of osteitis fibrosa cystica or renal stone colic. Of these 37 patients, 34 reported one or more neuropsychological symptoms preoperatively; 3 patients reported no neuropsychological symptoms preoperatively, and these 3 patients were excluded from the postoperative survey. Twelve months after successful parathyroidectomy, 25 patients responded to our questionnaire (Fig. 1) distributed at the outpatient clinic or by mail. They included 2 males and 23 females, ranging in age from 48 to 76 (mean 64) years. The other 9 patients were requested to respond by mail. Of these 9 patients, 3 gave no response, and 6 responded to less than half of the questions; thus, these 9 patients were excluded from the study.

Fig. 1.

Survey of primary hyperparathyroid patients (pts) treated surgically during an 8.5-year period (1995–2004)

Preoperative bone mineral density was measured in the lumbar spine (L2–L4) using a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometer. The serum calcium level was 10.1–12.4 (mean 11.0) mg/dl, the urinary calcium excretion rate was 51–497 (mean 246) mg/24 h, the creatinine clearance rate was 40–183 (mean 90.8) ml/min, and the bone mineral density was 0.2 to −4.8 (mean −2.5) SD.

The subjective symptoms were assessed by distributing questionnaires that contained eight questions dealing with the presence or absence of neuropsychological symptoms (Table 1). The eight questions were formulated based on a textbook [5] and dealt with “tiring easily, “forgetfulness,” “decreased concentration,” “depression,” “irritability,” “uneasiness,” “sleeplessness,” and “general health”. “Uneasiness” was defined as feeling worried or unhappy about a particular situation, especially because one thinks something bad or unpleasant might happen. The questionnaires were distributed before and 1 year after surgery. To ensure that the patients understood the questions, the meaning of each question was thoroughly explained prior to surgery. To ascertain patients’ perceptions of their general health, they were asked whether they felt better 1 year after surgery than before surgery. Patients were asked to select one of the following responses to each question: the symptom is totally absent or occurs rarely (score 0); the symptom is slight or occurs only occasionally (score 1); or the symptom has recently been aggravated or occurs frequently (score 2).

Table 1.

Questionnaire contents

| 1. Do you tire easily? |

| 2. Are you forgetful? |

| 3. Do you lack the ability to concentrate? |

| 4. Do you feel depressed? |

| 5. Do you feel irritable? |

| 6. Do you feel uneasiness? |

| 7. Do you experience sleeplessness? |

| 8. How do you perceive your general health compared with that before surgery?a |

aThis question was asked only once, 1 year postoperatively

Statistical analysis

A two-sided Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test was used to detect statistically significant differences among the responses; the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Results

General health perceptions 1 year after parathyroidectomy

When compared to their preoperative responses, the patients’ general health perceptions 1 year after surgery were improved in 13 cases (52%), unchanged in 11 cases (44%), and aggravated in 1 case (4%); these changes were statistically significant (P = 0.0013).

Comparison of the individual subjective neuropsychological symptoms’ grade

Table 2 shows the preoperative and 1-year postparathyroidectomy comparison of individual subjective neuropsychological symptoms. Preoperatively, 17 patients (68%) reported “tiring easily,” and 1 year postoperatively the symptom had resolved in 6 and was still reported by 11, although all 11 perceived the symptom as mild. However, of the 8 patients who did not report tiring easily preoperatively, 5 reported a mild degree of tiring easily 1 year postoperatively. These changes in the number of patients who reported tiring easily were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Comparison of pre- and postoperative scores

| Neuropsychological symptoms | Preoperative | 1 year postoperative | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | Score | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| Easily tired | Score | 0 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0.24 |

| 1 | 12 | 5 | 7 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | |||

| No. of patients | 25 | 9 | 16 | 0 | |||

| Forgetfulness | Score | 0 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0.8 |

| 1 | 15 | 5 | 8 | 2 | |||

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |||

| No. of patients | 25 | 6 | 17 | 2 | |||

| Decreased concentration | Score | 0 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0.3 |

| 1 | 14 | 6 | 6 | 2 | |||

| 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |||

| No. of patients | 25 | 10 | 13 | 2 | |||

| Depression | Score | 0 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| 1 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| No. of patients | 25 | 16 | 7 | 2 | |||

| Irritability | Score | 0 | 13 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0.45 |

| 1 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 1 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||

| No. of patients | 25 | 17 | 6 | 2 | |||

| Uneasiness | Score | 0 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 13 | 4 | 7 | 2 | |||

| 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| No. of patients | 25 | 12 | 10 | 3 | |||

| Sleeplessness | Score | 0 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 0 | |||

| 2 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |||

| No. of patients | 25 | 10 | 10 | 5 | |||

Changes in the number of patients reporting other neuropsychological symptoms, such as “forgetfulness,” “decreased concentration,” “depression,” “irritability,” “uneasiness,” and “sleeplessness,” before and after surgery were also not statistically significant (Table 2).

Discussion

In normal subjects, the serum calcium concentration is always kept within a narrow normal range and plays an important role in the physiological control of neuropsychological functions. In PHPT patients, even in those with the mild form, the abnormally elevated serum calcium concentration returns to the normal level postparathyroidectomy. It has been assumed that some subjective improvement in neuropsychological function must occur following surgery.

In the present prospective study of patients with incidentally detected, mild PHPT, 52% of all patients who had successful parathyroidectomy reported improved general health 1 year after surgery. This result was statistically significant.

Pasieka and Parsons [6] reported that general health improved following surgery in 60% of PHPT patients. Talpos et al. [7] studied 53 patients with asymptomatic hyperparathyroidism who were randomized into a parathyroidectomy group or an observation alone group; they were evaluated every 6 months for 2 years using the SF-36 health survey. The 28 patients who had parathyroidectomy had improved social and emotional function scores compared to the observation alone group. Edwards et al. [8], who studied 100 patients with PHPT, found that parathyroidectomy for hyperparathyroidism was associated with significant lasting improvement in subjective symptoms; they stated that the potential for long-term improvement of these QOL symptoms was a valid indication for parathyroidectomy. However, contrary to reports of long-term postoperative improvement in subjective symptoms, Okamoto et al., using the GHQ-28 in 26 patients with mild PHPT, found no improvement in symptoms except for severe depression 24 months after surgery, though they found improvement in the total GHQ score, somatic symptoms, anxiety, and severe depression 3 months following parathyroid surgery [9]. Okamoto et al. hypothesized that the transient, short-term improvement in symptoms after surgery may have been a consequence of patients’ expectations of treatment.

The results of the present study showed that approximately half of the patients reported improvement in general health perceptions, and there was no statistically significant improvement in any of the individual neuropsychological symptoms. The subjective satisfaction with surgery reported by 52% of our patients may also reflect their expectations of treatment.

Bollerslev et al., in a randomized study using the SF-36 involving 191 patients with asymptomatic PHPT who were assigned to surgery or medical observation, found that “no benefit of operative treatment, compared with medical observation, was found” [16]. In the present study, the numbers of patients required for comparison of differences before and after surgery, using a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, were calculated as follows: “tiring easily”, n = 39; “forgetful”, n = 382; “decreased concentration”, n = 62; “depression”, n = 55; “irritability”, n = 165; “uneasiness”, n = 1492; and “sleeplessness”, n = 1878. Therefore, between 39 and 1,878 patients would be required to have adequate statistical power to determine “whether surgery improves psychoneurological symptoms”. The sample size of the present study was 25 patients, which was too low to determine “whether surgery improves psychoneurological symptoms”. However, the present findings were similar to those of Bollerslev et al.

There is a recognized need to determine the surgical indications for PHPT. In 1990, the guidelines of the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) were published. The results from a questionnaire given to the members of the Society of Surgical Endocrinology of America showed that several practices were not precisely in accordance with the 1990 NIH guidelines [11]. Sywak et al. conducted a comparative study involving one group that met the criteria of the 1990 NIH guidelines and one group that did not. They reported that nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, depression, irritability, mood swings, and forgetfulness, improved in both groups [12]. The guidelines were revised in 2002, and a 2002 workshop panel promulgated six criteria for PHPT surgery [13]. Since there is uncertainty concerning the specificity of subjective symptoms, the NIH conference excluded them from the criteria for parathyroidectomy. Although the present study did not find that subjective neuropsychological symptoms were improved in patients with asymptomatic PHPT following parathyroidectomy, patients’ responses to questionnaires may not reflect their actual status as accurately as laboratory test results, such as the serum calcium level, the urinary calcium excretion rate, the creatinine clearance rate, and bone mineral density.

Nevertheless, obtaining information on changes in subjective symptoms is clinically important. The difficulty in quantitatively evaluating nonspecific symptoms has been previously identified, and some studies have used the Visual Analogue Scale [6, 14] or the SF-36 [7, 15, 16]. We devised an original questionnaire based on a textbook [5]. This questionnaire has not been validated as a research tool and was not tested on the normal population. However, the five questions related to “tiring easily, “forgetfulness,” “depression,” “irritability,” and “general health” are identical to those used by Pasieka et al. [6, 14], and the other three questions dealing with “decreased concentration,” “uneasiness,” and “sleeplessness” are all easily understandable neuropsychological symptoms. To ensure that all patients understood the questions, the meaning of each question was thoroughly explained to the patient prior to surgery; however, 1 year postoperatively, the questionnaires were simply sent by mail to the patients with no further explanations. To allow nonspecific symptoms to be more readily evaluated, simple, quantitative methods are required.

Bollerslev et al. [10] reported that asymptomatic patients with mild PHPT have more psychological symptoms than normal controls and decreased QOL. In the present study, of the 37 patients who underwent parathyroid surgery for “asymptomatic” PHPT, 34 had one or more neuropsychological symptoms preoperatively, though it was not confirmed that these symptoms were due to the PHPT itself. The results of the survey done 1 year after successful parathyroidectomy did not show any definite improvement in any of the individual neuropsychological symptoms. The main reason for this might be the mild nature of the patients’ PHPT. Two reasons may explain why six patients gave incomplete answers and three patients did not respond to the second questionnaire: the questionnaires were mailed to patients who had stopped visiting the out-patient clinic, and patients may have found the questionnaire bothersome. If the patients had been truly symptomatic, they would have visited our hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Prof. Yasuo Watanabe (Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapy, Nihon Pharmaceutical University) for his critical comments and to Mr. Masashi Furukawa (Department of Biostatistics, Shionogi & Co., Ltd) for his statistical analysis and clinical comments.

References

- 1.Silverberg SJ, Shane E, Jacobs TP, Siris E, Bilezikian JP (1999) A 10-year prospective study of primary hyperparathyroidism with or without parathyroid surgery. N Engl J Med 341:1249–1255 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Silverberg SJ, Gartenberg F, Jacobs TP, Shane E, Siris E, Staron RB, McMahon DJ, Bilezikian JP (1995) Increased bone mineral density after parathyroidectomy in primary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80:729–734 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Parfitt AM, Rao DS, Kleerekoper M (1991) Asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism discovered by multichannel biochemical screening: clinical course and considerations bearing on the need for surgical intervention. J Bone Miner Res Suppl 2:S97–101 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Jorde R, Bonaa KH, Sundsfjord J (2000) Primary hyperparathyroidism detected in a health screening. The Tromso study. J Clin Epidemiol 53:1164–1169 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Obara T (1989) Diagnosis of primary hyperparathyroidism. In: Fujimoto Y (ed) Practical approach to clinical endocrinology, 1st edn. Chugaiigaku, Tokyo, pp 170–174

- 6.Pasieka JL, Parsons LL (1998) Prospective surgical outcome study of relief of symptoms following surgery in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg 22:513–519 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Talpos GB, Bone HG, Kleerekoper M, Phillips ER, Alam MM, Divine GW, Rao DS (2000) Randomized trial of parathyroidectomy in mild asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: patient description and effects on the SF-36 health survey. Surgery 128:1013–1021 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Edwards ME, Rotramel BA, Beyer T, Gaffud MJ, Djuricin G, Loviscek K, Solorzano CC, Prinz RA (2006) Improvement in the health-related quality-of-life symptoms of hyperparathyroidism is durable on long-term follow-up. Surgery 140:655–664 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Okamoto T, Kamo T, Obara T (2002) Outcome study of psychological distress and nonspecific symptoms in patients with mild primary hyperparathyroidism. Arch Surg 137:779–783 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bollerslev J, Jansson S, Mollerup CL, Nordenstrom J, Lundgren E, Torring O, Varhaug JE, Baranowski M, Aanderud S, Franco C, Freyschuss B, Isaksen GA, Ueland T, Rosen T (2007) Medical observation compared with parathyroidectomy, for asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: a prospective, randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:1687–1692 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Sosa JA, Power NR, Levine MA, Udelsman R, Zeiger MA (1998) Profile of a clinical practice: thresholds for surgery and surgical outcomes for patients with primary hyperparathyroidism: a national survey of endocrine surgeons. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83:2658–2665 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Sywak MS, Knowlton ST, Pasieka JL, Parsons LL, Jones J (2002) Do the National Institutes of Health consensus guidelines for parathyroidectomy predict symptom severity and surgical outcome in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism? Surgery 132:1013–1020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bilezikian JP, Potts JT Jr, Fuleihan Gel H, Kleerekoper M, Neer R, Peacock M, Rastad J, Silverberg SJ, Udelsman R, Wells SA (2002) Summary statement from a workshop on asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism: a perspective for the 21st century. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:5353–5361 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Pasieka JL, Parsons LL, Demeure MJ, Wilson S, Malycha P, Jones J, Krzywda B (2002) Patient-based surgical outcome tool demonstrating alleviation of symptoms following parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. World J Surg 26:942–949 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Burney RE, Jones KR, Peterson M, Christy B, Thompson NW (1998) Surgical correction of primary hyperparathyroidism improves quality of life. Surgery 124:987–991 [PubMed]

- 16.Burney RE, Jones KR, Christy B, Thompson NW (1999) Health status improvement after surgical correction of primary hyperparathyroidism in patients with high and low preoperative calcium levels. Surgery 125:608–614 [PubMed]