Abstract

Knowing the geographic extents of species is crucial for understanding the causes of diversity distributions and modes of speciation and extinction. Species geographic ranges are often viewed as approximately constant in size in geological time, even though climate change studies have shown that historical and modern species geographic distributions are not static. Here, we use an extensive global microfossil database to explore the temporal trajectories of geographic extents over the entire lifespan of marine nannoplankton, diatom, planktic foraminifer and radiolarian species. We show that geographic extents are not static over geological time-scales. Temporal trajectories of species geographic ranges are asymmetric: the rise is quicker than the fall. We propose that once a species has overcome its initial difficulties in geographic establishment, it rises to its peak geographic extent. However, once this peak value is reached, it will also have a maximal number of species to interact with. The negative of these biotic interactions could then cause a gradual geographic decline. We discuss the multiple implications of our findings with reference to macroecological and macroevolutionary studies.

Keywords: geographic area, occurrences, equilibrium versus non-equilibrium, genera, Neptune

1. Introduction

The geographic extent of a species is malleable over ecologic and evolutionary time (Willis 1922). Geographic range shifts, expansions and contractions are among the foci of current research on the effects of historical and recent climate change on species (Davis & Shaw 2001; McCarty 2001; Parmesan & Yohe 2003). Yet, geographic ranges may change even without dramatic environmental perturbations (Holt 2003). Although extant species, including those with fossil records, have been observed to undergo range contractions and expansions (Precht & Aronson 2004), studies on the temporal trajectory of geographic extent over the entire lifespan or duration of species are limited. This is despite the fact that species range transformations (Gaston 1998) have profound implications for understanding both the evolution and ecology of species and their communities.

Using species occurrence data from an extensive global paleontological microfossil database, we ask the following questions: Is there an average temporal trajectory of species or genus geographic extent that is universal for different groups of organisms? What shape does this average temporal trajectory take? Is there a prolonged phase of stability in geographic extent that can be considered an equilibrium geographic range?

Previous studies suggest that geographic ranges are quickly established after speciation and remain perceptibly constant (Jablonski 1987; Vrba & deGusta 2004). Others studies, however, emphasize the temporal transformations of geographic ranges (Miller 1997; Gaston 1998; Webb & Gaston 2000; Raia et al. 2006; Foote in press). We can envision four simple models for an average temporal trajectory. (i) A uniform trajectory, equivalent to Gaston's stasis or post-expansion stasis model (Gaston 1998, 2003) which also approximates Jablonski's (1987) suggestion that species maximum geographic ranges are achieved very quickly (figure 1a). In this case, a prolonged equilibrium geographic range exists, not least because geographic ranges are thought to be a stable species-level property (Jablonski 1987, 2007). (ii) A linear growth trajectory such that a species spreads continuously but experiences a crash instantaneous in geological time, close to the time of its extinction (figure 1b). This is the simplest form of Willis' (1922) age and area model, also discussed by Gaston (1998, 2003). (iii) A symmetric trajectory such that a new lineage at the beginning of its existence may spread out from a restricted geographic location to become maximally dispersed at the same rate as its decline towards the end of its life, after achieving its peak geographic extent (figure 1c). This symmetric temporal trajectory of geographic ranges was shown by Foote (in press) for the genera of marine fossil invertebrates, but no mechanism was proposed for the pattern. (iv) A skewed or asymmetrical trajectory (figure 1d). For example, the initial rise could be slower than the subsequent fall. This is because establishment for a new species is difficult, as evident from the invasive biology literature (Sax & Brown 2000). However, the decline could be relatively quick as demonstrated in the historical and fossil records (e.g. Pandolfi 1999; Steadman & Martin 2003). Alternatively, geographic range increase could be quicker than range decline, as shown empirically for genera of extant birds (Webb & Gaston 2000).

Figure 1.

Idealized models of average temporal trajectories of standardized geographic extent over standardized lifetimes of taxa. (a) Uniform, (b) linear, (c) symmetric and (d) skewed.

Our study is the first to our knowledge that explores temporal trajectories of geographic extents over the entire lifespan of multiple species. From our analyses, we observe that the average temporal trajectories of geographic extent for species of the microfossil groups we studied are asymmetrical, such that the rise is slightly quicker than the fall. There is, however, no perceptible prolonged phase of stability in geographic extent for the average species. Our discoveries impact macroevolutionary and macroecological analyses. We discuss the implications of our findings and suggest directions for future work.

2. Material and methods

Microfossils have very high preservation rates (Bown et al. 2004) relative even to taxa such as brachiopods and bivalves, commonly used in quantitative paleobiological analyses. Neptune (Lazarus 1994; Spencer-Cervato 1999; Leckie et al. 2004; Lazarus et al. 2007) is an integrated online database of microfossil occurrence data from deep sea drilling projects, maintained and hosted by Chronos (http://chronos.org), which continues to be updated. This combination of the high preservation rates of marine microfossils and the extensive and highly temporally resolved sampling represented in Neptune allows us to investigate temporal changes in species geographic extent.

We use occurrence data from all four microfossil groups represented in Neptune, namely diatoms, nannoplankton, radiolarians and planktic foraminifers. The first two groups are phytoplankton and the latter are zooplankton. Occurrence data were downloaded from Neptune via the Paleobiology Database (www.pbdb.org access data 19 January 2007). Each occurrence datum of a population with a confirmed identity (‘resolved_species_id’ in Neptune) is identified by a unique sample identification number (‘sample_id’) in Neptune. Only valid taxa were included for the download. We limit this study to the Cenozoic era by including only species originating after 65.5 Myr ago (Ma). We also excluded species that continue to have occurrences after 1 Ma in order to avoid truncations of the temporal trajectories of geographic ranges. Each occurrence datum is associated with current day latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates and an absolute value of its geological age (given by an age model for that particular core, see Spencer-Cervato 1999). The sampling resolution of Neptune is 330 kyr at the coarsest (Spencer-Cervato 1999). The number of occurrences retained is more than 10 000 for hundreds of species. Median durations of the groups range from approximately 7 to 10 Myr (table 1). The occurrence data are globally distributed (see fig. 2.1 in Spencer-Cervato 1999). Owing to plate tectonic activities, the current day latitudes and longitudes in Neptune were reconstructed for a more accurate representation of the geographic distribution of these species using the program LocRot written by D. Rowley (2007, personal communication). It is, however, important to note that the physical location where these planktic microfossils are sampled only approximate their living geographic location in the water column.

Table 1.

Summary of Neptune data used. (Neptune data restricted to species with first records at or after 65.5 Ma and last records at or before 1 Ma. The first two columns of numbers are number of occurrences (occ) and number of species represented (N). The rest of the columns are in Myr for each of the groups, where FO(max), earliest first occurrence; FO(min), latest first occurrence; LO(max), earliest last occurrence; LO(min), latest last occurrence; Dur(med), median duration; Dur(mean), mean duration and Dur(s.d.), standard deviation of durations.)

| occ | N | FO(max) | FO(min) | LO(max) | LO(min) | Dur(med) | Dur(mean) | Dur(s.d.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| diatoms | 14 614 | 453 | 63.0 | 1.0 | 60.4 | 1.0 | 7.4 | 11.4 | 12.6 |

| nannoplankton | 29 174 | 372 | 65.9 | 1.6 | 65.0 | 1.0 | 9.6 | 13.2 | 12.8 |

| planktic foraminifers | 24 741 | 209 | 65.2 | 2.3 | 64.8 | 1.1 | 9.2 | 13.1 | 12.5 |

| radiolarians | 21 395 | 404 | 56.6 | 1.1 | 49.9 | 1.0 | 10.5 | 12.4 | 10.5 |

Owing to their sometimes interchangeable usage in the literature, we have used both the terms geographic range and extent loosely in the introduction. In this section and §3, we adhere to stricter definitions of measures of geographic extent (γ). We calculated the frequency of occurrence (γfoc) and geographic area (sensu Gaston 1991) as measured by kernel-smoothed area (γksa) for species over their observed lifetime. The frequency of occurrence is the number of unique sections of unique cores (‘sample_id’ in Neptune) for a given species occurring in each ith time bin, ti. It is a proxy for abundance which has also been used as a proxy for geographic range (e.g. Vrba & deGusta 2004). Kernel-smoothed area is calculated as the sum of the number of 1° latitude by 1° longitude grids that contains 95% of the density, for a given species occurring in each ith time bin, ti. The function ‘kernel2d’ in the R (R Development Core Team 2006) ‘splancs’ library was modified for this purpose. We are certainly aware of the many other available methods of capturing geographic range and area, especially with the accelerating development of GIS methods (e.g. Gaston 1994; Quinn et al. 1996), but limit ourselves to two measures for the simplicity of presentation and because range measures are in general strongly correlated with one another (Quinn et al. 1996; Blackburn et al. 2004).

Although absolute ages are available for each sample in Neptune, we binned the data temporally, such that each time bin, ti, is 1 Myr in duration, to reflect the uncertainty in the dating of the samples. For example, a sample of age 2.56 Ma would be in the time bin lesser than or equal to 3 Ma and greater than 2 Ma.

The two measures of geographic extent (γfoc and γksa) for each jth species were standardized. That is, γj is weighed by the maximum value of γi,j for each jth species, such that γj ranged between 0 and 1 for every species. Similarly, the lifetime (λj) of each jth species is weighed by the maximum value of λi,j for that species, such that every species is first observed at time=0 and last observed at time=1. A species-specific calculable temporal data point for each measure is termed a standardized data point (s.d.p.). The models described below were fitted to these standardized data for all taxa, or subsets of taxa with a minimum number of s.d.p.s, simultaneously for each microfossil group. In doing this, we assume that there is an estimable average temporal trajectory of geographic extent for each group, although there may be differences among groups.

The uniform, linear, symmetric and skewed models were fitted as justified in §1 (figure 1, see appendix A for detailed descriptions of the models). The skewed model is constrained such that estimated lifetime has to be between 0 and 1 but not the symmetric model (figure 1 and appendix A). Note that the symmetric model can appear asymmetrical within the temporal limits of the standardized data while the skewed model can likewise be symmetrical under some conditions (appendix A). We assume that the two measures of geographic extent, γfoc and γksa, are functions of the time in the life (λ) of taxa and use a maximum likelihood approach for model selection. The Akaike Information Criterion or AIC is computed as −2 log(L(θk|data))+2K, where L(θk|data) is the likelihood of the parameters θ of the kth model, given the data, and K is the number of parameters estimated (Burnham & Anderson 2002). The weight of kth model is calculated as

where AICmin is that of the best model, such that the weights of the four models sum to 1 (Burnham & Anderson 2002). We also estimated parameters for each of these models. Genus analyses were done in the same manner as described for species. Maximum likelihoods were calculated and parameters estimated using the function ‘optim’ in R (R Development Core Team 2006).

3. Results

The frequency of occurrence, γfoc, through standardized lifetime averaged for all species is strongly correlated with geographic area, γksa, in all four microfossil groups (p>0.001 with spearman's ρ ranging from 0.53 for diatom species to 0.75 for planktic foraminifers, detailed results not shown), corroborating the finding that various measures for range size are interchangeable to some extent (Quinn et al. 1996; Blackburn et al. 2004).

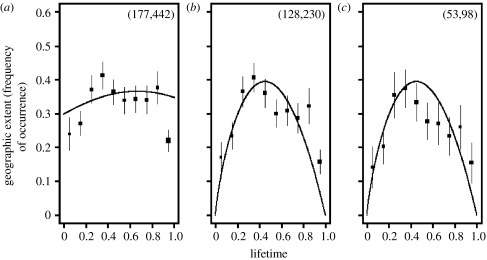

The average temporal trajectory of the frequency of occurrences of the species in each of the four microfossil groups is best described by a symmetric model when all data are used (table 2). However, when only species with more available s.d.p.s were used in model fitting, the skewed distribution was consistently the best model (figure 2). We have chosen to illustrate this with nannoplankton species because they have the most reliable taxonomy (C. Cervato 2007, personal communication).

Table 2.

Summary of model fits for the frequency of occurrences of species. (AIC and model weights for the models compared in each of the four microfossil groups using frequency of occurrence data. Each of the groups are also subsetted such that all species are used (all), only species with more than 10 standardized data points or s.d.p.s (>10) or more than 20 s.d.p.s (>20) are used in model fitting. N, number of species. Best models in each case are in italics.)

| all | >10 | >20 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | weight | AIC | weight | AIC | weight | ||

| diatoms | N | 453 | 76 | 15 | |||

| uniform | 730.98 | 0.01 | 240.75 | 0.12 | 59.88 | 0.21 | |

| linear | 729.75 | 0.02 | 241.98 | 0.06 | 61.85 | 0.08 | |

| symmetric | 721.77 | 0.97 | 238.78 | 0.31 | 60.91 | 0.12 | |

| skewed | 806.77 | 0.00 | 237.80 | 0.51 | 57.75 | 0.60 | |

| nannoplankton | N | 372 | 108 | 29 | |||

| uniform | 726.77 | 0.03 | 376.26 | 0.00 | 126.58 | 0.03 | |

| linear | 728.52 | 0.01 | 369.90 | 0.00 | 124.60 | 0.07 | |

| symmetric | 719.82 | 0.96 | 374.27 | 0.00 | 124.66 | 0.07 | |

| skewed | 777.59 | 0.00 | 358.18 | 1.00 | 119.56 | 0.84 | |

| planktic foraminifers | N | 209 | 99 | 24 | |||

| uniform | 593.38 | 0.00 | 338.02 | 0.00 | 112.29 | 0.00 | |

| linear | 593.38 | 0.00 | 336.21 | 0.00 | 112.69 | 0.00 | |

| symmetric | 581.89 | 0.99 | 328.16 | 0.00 | 109.50 | 0.00 | |

| skewed | 593.72 | 0.00 | 294.85 | 1.00 | 89.21 | 1.00 | |

| radiolarians | N | 404 | 129 | 24 | |||

| uniform | 773.05 | 0.01 | 402.12 | 0.00 | 86.84 | 0.04 | |

| linear | 773.71 | 0.01 | 402.69 | 0.00 | 87.75 | 0.03 | |

| symmetric | 763.77 | 0.98 | 396.68 | 0.01 | 86.63 | 0.04 | |

| skewed | 810.64 | 0.00 | 388.07 | 0.99 | 80.62 | 0.89 | |

Figure 2.

Model fits for the temporal trajectories of geographic extent as measured by the frequency of occurrences for nannoplankton species. In (a), all species were used, while in (b) and (c), only species with more than 10 and 20 s.d.p.s, respectively, were used. The squares are the average species geographic extent in each time bin and the size of the square indicates the relative proportion of data points available. Numbers in parentheses at the top right corners indicate the minimum and maximum number of data points available for the time bins in these plots. The error bars are 95% CI. The best models selected are superimposed: (a) symmetric, (b) skewed and (c) skewed, see also tables 2 and 3). Note that the models were fitted to un-binned data.

Results are similar for the average temporal trajectory of the geographic area of species: a symmetric distribution is the best model when all data are used in model fitting, but a skewed distribution is the best model (with model weights >0.9, results not presented) when only species with more available s.d.p.s are used (table 3).

Table 3.

Parameters estimated for the best models. (The best models and their parameters are listed for both the frequency of occurrences and geographic area trajectories for each group. These are also divided into results for all taxa with s.d.p.s of more than 10 and more than 20.)

| best model parameters | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nannoplankton | diatoms | radiolarians | planktic foraminifers | |||||||||

| species—frequency of occurrences | ||||||||||||

| all species | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ |

| 0.67 | 1.09 | 0.31 | 1.08 | 0.64 | 1.11 | 0.33 | 1.06 | |||||

| s.d.p.>10 | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β |

| 1.82 | 0.89 | 1.67 | 0.86 | 2.04 | 0.90 | 1.62 | 0.92 | |||||

| s.d.p.>20 | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β |

| 1.76 | 0.84 | 1.79 | 0.84 | 2.24 | 0.86 | 1.75 | 0.93 | |||||

| species—geographic area | ||||||||||||

| all species | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ |

| 0.41 | 0.99 | 0.30 | 0.96 | 0.36 | 1.07 | 0.27 | 0.97 | |||||

| s.d.p.>10 | skewed | α | β | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ | skewed | α | β |

| 1.74 | 0.96 | 0.36 | 1.03 | 0.60 | 1.08 | 1.57 | 0.96 | |||||

| s.d.p. >20 | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β |

| 1.65 | 0.94 | 1.82 | 0.99 | 1.98 | 0.96 | 1.60 | 0.97 | |||||

| genus—frequency of occurrences | ||||||||||||

| all genera | uniform | k | uniform | k | skewed | α | β | uniform | k | |||

| 0.29 | 0.25 | 1.92 | 0.90 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| s.d.p.>10 | skewed | α | β | uniform | k | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | |

| 1.57 | 0.84 | 0.23 | 1.87 | 0.87 | 1.31 | 0.76 | ||||||

| s.d.p. >20 | uniform | k | uniform | k | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | ||

| 0.26 | 0.23 | 1.89 | 0.88 | 1.29 | 0.75 | |||||||

| genus—geographic area | ||||||||||||

| all genera | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ | symmetric | μ | σ | uniform | k | |

| 0.37 | 1.03 | 0.20 | 1.03 | 0.33 | 1.05 | 0.20 | ||||||

| s.d.p.>10 | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | uniform | k | |

| 1.52 | 0.90 | 1.65 | 0.91 | 1.71 | 0.92 | 0.17 | ||||||

| s.d.p.>20 | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | skewed | α | β | uniform | k | |

| 1.52 | 0.87 | 1.75 | 0.92 | 1.82 | 0.94 | 0.17 | ||||||

Parameter estimates show that μ values are mostly <0.5 when the symmetric model is selected as the best model (table 3), indicating that geographic extent is greatest when closer to the earlier parts of the lifetime of species. Similarly, where the skewed model is selected as the best model, estimated parameters indicate the same asymmetry, with the possible exception of diatoms, whose trajectory borders on being symmetric (table 3). In other words, species temporal trajectories of geographic extent are in general right-skewed.

Genus results for both the frequency of occurrences and geographic area are less clear-cut, where either the uniform, symmetric or skewed models are selected, although the skewed model is again increasingly favoured, as models are fitted only to genera with more s.d.p.s (table 3). However, the weights of the models are more even in all cases (where the best model has a model weight of 0.4–0.6, results not shown).

4. Discussion

Microfossil species increase in geographic extent to a peak and decline to extinction without an obvious equilibrium phase, measured either by frequency of occurrences or geographic area. This lack of an observed equilibrium is contrary to the claims of some previous studies (e.g. Jablonski 1987; Vrba & deGusta 2004). The change in geographic extent over time is also not monotonic as indicated by a simple age and area model (Willis 1922; Gaston 1998): there is a gradual rise and a fall. In retrospect, species must have smaller occurrence frequencies and smaller geographic areas to start with and these must decline to zero when they are extinct, regardless of the mode(s) or cause(s) of speciation or extinction. Even in vicariance events, two separated populations destined to become two species will pass through a period when the first individuals to be recognized as descendent species do not constitute large populations. Sampling phenomena may also contribute to this peaked distribution: if species are more abundant around the middle part of their lifespan or duration, the chance of their being sampled increases (Enquist et al. 1995); hence their observed trajectory of geographic extent may appear to be peaked, regardless of their true trajectories. Alternatively, but not mutually exclusively, species could have more established morphological characteristics closer to the middle part of their lives so that they are differentiated with greater ease by systematists. However, should we expect to see a peaked trajectory averaged over multiple species? These different species (and groups) (i) have different preservational probabilities, (ii) have different completeness of sampling, (iii) were extant at different times, places and hence environmental conditions and (iv) have different absolute geographic ranges and varying frequencies of occurrences. This heterogeneity averaged should be observed as a distribution represented by randomness, but instead we see a peaked distribution. This result was foreshadowed at genus level (Jernvall & Fortelius 2004, Foote in press).

When all available occurrence data are used, the best model for the average species trajectory is symmetric but cannot be constrained to having an average estimated lifetime within the span of the observed data. The symmetric trajectory is rather flat between the observed first and last occurrences and the trajectory intersects the lifetime axis at proportions far from 0 to 1 (figure 2a). In other words, for many species, we will rarely observe them in their prolonged period of early existence or during their continued decline.

However, a right-skewed average species trajectory is a better description for the microfossil groups analysed, when more densely sampled species are studied. This observation of a quicker rise than decline has important implications because many species will be declining in their geographic range during their observed lifespans (Gaston 2003). Perhaps because the patterns observed are averaged from multiple species, those with longer lifespan may swamp the true pattern: geologically long-lived, abundant species may have biological characteristics that allow them to expand quickly, but their abundance protects them from a rapid decline, hence the asymmetry. However, the best models from fitting to the species with the longest 25% of stratigraphic ranges are no different from species with shorter durations (results not shown). Moreover, a visual inspection of random species reveals that individual species trajectories often have more skewed distributions than the species averages presented here.

If we take the right-skewed trajectory as the best model, the following proposal can be made. Once a species becomes sufficiently established, it will rise to a high point in extent relatively quickly (cf. its total lifespan) because the initial problems associated with establishment have been solved during the earlier part of its life, a large part of which we may not observe. However, once a peak extent is reached, there is an irreversible downturn, even though the subsequent decline can be rather slow. One possible explanation for this is that once a species has reached its dispersal limit, it will also interact with a maximum number of predators, parasites and/or competitors. Henceforth, it survives by coping with its natural enemies in place, and in time, a combination of biological and physical environmental changes will lead it to extinction.

Like others, we have implicitly assumed that abundance fluctuations are short in relation to the lifespan of species and hence are not prominent in the data reflecting geographic extent (Webb & Gaston 2000; Roy 2001). Spotty sampling may capture biased parts of geographic extent trajectories as species go through taxon cycling or age-dependent abundance variation (McKinney & Frederick 1999; Ricklefs & Bermingham 2002). However, the time-scale of taxon cycling is much smaller than the scale of our analyses here. Time scales apart, it is also difficult to envision how taxon cycling in combination with sampling might consistently give rise to a right-skewed trajectory, if it is not the overarching pattern.

We have thus far only discussed the shape of species geographic extent trajectories not least because the results are much clearer compared with that for genus data. However, a brief mention of genus patterns is warranted because other studies have used genera as their focal levels (Miller 1997; Jernvall & Fortelius 2004; Foote in press). Best models for genus analyses range from uniform to symmetric and skewed; model weights also give a somewhat equivocal answer although there is a tendency for a right-skewed trajectory as seen also for species. The expansion and contraction of ranges of genera may either be due to the ranges of individual species expanding and contracting, or due to the number of species in a genus increasing and decreasing (Miller 1997). We have not investigated the behaviour of species within genera.

This peek at species geographic extent trajectories has opened a wealth of questions for us: are there better models for describing general geographic range trajectories? We have not explicitly included position information and cannot detect position shifts. How might position shifts complicate our understanding of temporal range trajectories? Are the particular trajectories predictable based on the biology of individual species (Raia et al. 2006), or are they strongly influenced by environmental shifts (Jenkins 1992)? Were there some environmental events that had strong effects on the species range trajectories during the Cenozoic? As preliminarily analysed here (results not shown), the observed average declines are not significantly different before and after three investigated times of environmental turbulence, namely the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum (e.g. Gibbs et al. 2006), the Oligocene–Miocene boundary (e.g. Spencer-Cervato 1999; Kamikuri et al. 2005) and the mid-Pliocene turnover (e.g. Spencer-Cervato 1999; Gibbs et al. 2005). This is opposed to the finding that mass extinctions affected the symmetry of the waxing and waning of marine genera (Foote in press). Perhaps the chosen extinction events are not as prominent for microfossils as the big five mass extinctions were for macrofossils, and/or more fine-tuned investigations and temporally denser data may be needed to detect changes in range trajectories. Vertical and horizontal ranges are positively correlated (Liow 2007), but will different trajectories be seen if we include this 3rd spatial dimension of depth? Many non-random physical and biological factors can cause non-fossilization (e.g. Holland 2000). Since we have neither explicitly modelled temporal or spatial sampling nor preservation probabilities, it is uncertain exactly if, and how, sampling will affect the patterns observed and hence the mechanisms we have proposed.

It is clear that species geographic ranges and abundance are not even approximately static through the life of a species, and hence neither is the detectability of a species. We are in general sampling species only after they have been extant for a substantial period of time unless the species are abundant from the start. Likewise, their tapering off at the end of their lives makes it difficult to estimate with confidence the final moment of their existence. This realization, stemming from microfossils that have arguably the most complete fossil record (Bown et al. 2004), has important implications for the use and estimation of parameters from the fossil record in macroevolution and phylogenetics. First, turnover rates are a focal point of today's paleobiological research, and their estimation is dependent on the estimation of true first and last occurrences. Even though some methods have been developed to account for incomplete preservation (Marshall 1997; Foote 2003, 2005; Solow 2003), more needs to be done to accommodate temporally changing geographic distributions. Second, in the widespread use of molecular clocks, it is common to focus on the development of substitution models and flexibility in imposed constraints (e.g. Yang & Rannala 2006) and to assume that fossil data inaccuracy comes mainly in the form of dating errors (e.g. Pulquerio & Nichols 2007). However, clearly, more work is needed to understand the basic temporal distribution of detectability and hence how that affects the estimates of fossil calibration points used in molecular clock studies. Finally, modern environmental change and its effect on species range, distributions and diversity is currently one of the most prominent areas of macroecological research (e.g. Hughes 2000; Thuiller et al. 2005; Araújo & Rahbek 2006). There is a tendency to implicitly assume that pre-human impact geographic distributions are perceptibly static when modelling range shifts (e.g. Lawler et al. 2006), even though ‘background’ changes in range distributions (Willis et al. 2007) are not at all well understood. We hope that this exposé will stimulate more research on the temporal trajectory of taxon geographic ranges, vital for many branches of ecology and evolution.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous referees for constructive reviews, Torbjørn Ergon, Paul Harnik and Michael Foote for discussions, David Rowley for providing reconstructed paleo-coordinates, Cinzia Cervato for advising us on Neptune and Lise Heier for programming help. Michael Foote also generously shared his (un)published results with us.

Appendix A.

The four models of temporal change in standardized geographic extent, where γ (frequency of occurrences or geographic area as measured by kernel-smoothed area) is dependent on the standardized time in the life (lifetime, λ) of a taxon.

Uniform model, where

such that k is the equilibrium geographic extent.

Linear model, where

such that c value is the value of the standardized geographic extent when we first observe a taxon and m is the rate of geographic expansion (or decline).

Symmetric model, where

such that μ is the time in the life of taxa where the maximum geographic extent occurs and σ is the standard deviation of the geographic extent around this time in a taxon's life, giving indication as to how much of the true lifespan we do not observe. This is based on a normal curve and 2σ from the mean, μ, in each direction can be interpreted as the estimated time of origination and extinction in each direction.

Skewed model, where

such that α and β together describe the shape of geographic expansion and decline. The lifetime of a taxon is constrained such that the observed first and last occurrences are assumed to be true. This is modified from a beta distribution. Note that if α=2 and β=1, the trajectory is symmetric.

References

- Araújo M.B, Rahbek C. How does climate change affect biodiversity? Science. 2006;313:1396–1397. doi: 10.1126/science.1131758. doi:10.1126/science.1131758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn T, Jones K.E, Cassey P, Losin N. The influence of spatial resolution on macroecological patterns of range size variation: a case study using parrots (Aves: Psittaciformes) of the world. J. Biogeogr. 2004;31:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Bown P.R, Lees J.A, Young J.R. Calcareous nannoplankton evolution and diversity through time. In: Thierstein H, Young J.R, editors. Coccolithophores: from molecular processes to global impact. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2004. pp. 481–508. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham K.P, Anderson D.K. Springer; New York, NY: 2002. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M.B, Shaw R.G. Range shifts and adaptive responses to Quaternary climate change. Science. 2001;292:673–679. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5517.673. doi:10.1126/science.292.5517.673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enquist B.J, Jordan M.A, Brown J.H. Connections between ecology, biogeography, and paleobiology—relationship between local abundance and geographic-distribution in fossil and recent mollusks. Evol. Ecol. 1995;9:586–604. doi:10.1007/BF01237657 [Google Scholar]

- Foote M. Origination and extinction through the Phanerozoic: a new approach. J. Geol. 2003;111:125–148. doi:10.1086/345841 [Google Scholar]

- Foote M. Pulsed origination and extinction in the marine realm. Paleobiology. 2005;31:6–20. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031<0006:POAEIT>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Foote, M. In press. Symmetric waxing and waning of marine animal genera. Paleobiology

- Gaston K.J. How large is a species' geographic range? Oikos. 1991;61:434–438. doi:10.2307/3545251 [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K.J. Measuring geographic range sizes. Ecography. 1994;17:198–205. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1994.tb00094.x [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K.J. Species-range size distributions: products of speciation, extinction and transformation. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 1998;353:219–230. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0204 [Google Scholar]

- Gaston K.J. Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2003. The structure and dynamics of geographic range. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs S.J, Young J.R, Bralower T.J, Shackleton N.J. Nannofossil evolutionary events in the mid-Pliocene: an assessment of the degree of synchrony in the extinctions of Reticulofenestra pseudoumbilicus and Sphenolithus abies. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2005;217:155–172. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.11.005 [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs S.J, Bown P.R, Sessa J.A, Bralower T.J, Wilson P.A. Nannoplankton extinction and origination across the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Science. 2006;314:1770–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1133902. doi:10.1126/science.1133902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland S.M. The quality of the fossil record: a sequence stratigraphic perspective. Paleobiology. 2000;26:148–168. [Google Scholar]

- Holt R.D. On the evolutionary ecology of species' ranges. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2003;5:159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes L. Biological consequences of global warming: is the signal already apparent? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000;15:56–61. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01764-4. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01764-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski D. Heritability at the species level: analysis of geographic ranges of Cretaceous mollusks. Science. 1987;238:360–363. doi: 10.1126/science.238.4825.360. doi:10.1126/science.238.4825.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski D. Scale and hierarchy in macroevolution. Palaeontology. 2007;50:87–109. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00615.x [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins D.G. Predicting extinctions of some extant planktic Foraminifera. Mar. Micropaleontol. 1992;19:239–243. doi:10.1016/0377-8398(92)90030-N [Google Scholar]

- Jernvall J, Fortelius M. Maintenance of trophic structure in fossil mammal communities: Site occupancy and taxon resilience. Am. Nat. 2004;164:614–624. doi: 10.1086/424967. doi:10.1086/424967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikuri S.-I, Nishi H, Moore T.C, Nigrini C.A, Motoyama I. Radiolarian faunal turnover across the Oligocene/Miocene boundary in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Mar. Micropaleontol. 2005;57:74–96. doi:10.1016/j.marmicro.2005.07.004 [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J.J, White D, Neilson R.P, Blaustein A.R. Predicting climate-induced range shifts: model differences and model reliability. Glob. Change Biol. 2006;12:1568–1584. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01191.x [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus D. Neptune: a marine micropaleontology database. Math. Geol. 1994;26:817–831. doi:10.1007/BF02083119 [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, D., Cervato, C. & Diver, P. 2007 Neptune database. See www.chronos.org

- Leckie, M., Cervato, C., Huber, B. T., Clark, K., Diver, P. & Hooks, K. 2004 Using theNeptunedatabase to explore Mesozoic–Cenozoic chronostratigraphy and deep-sea microfossil record vol. 36, Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, pp. 152. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America.

- Liow L.H. Does versatility as measured by geographic range, bathymetric range and morphological variability contribute to taxon longevity? Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2007;16:117–128. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00269.x [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C.R. Confidence intervals on stratigraphic ranges with nonrandom distributions of fossil horizons. Paleobiology. 1997;23:165–173. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty J.P. Ecological consequences of recent climate change. Conservation Biol. 2001;15:320–331. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2001.015002320.x [Google Scholar]

- McKinney M.L, Frederick D.L. Species–time curves and population extremes: ecological patterns in the fossil record. Evol. Ecol. Res. 1999;1:641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Miller A.I. A new look at age and area: the geographic and environmental expansion of genera during the Ordovician radiation. Paleobiology. 1997;23:410–419. doi: 10.1017/s0094837300019813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi J.M. Response of Pleistocene coral reefs to environmental change over long temporal scales. Am. Zool. 1999;39:113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Parmesan C, Yohe G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature. 2003;421:37–42. doi: 10.1038/nature01286. doi:10.1038/nature01286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Precht W.F, Aronson R.B. Climate flickers and range shifts of reef corals. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004;2:307–314. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0307:CFARSO]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Pulquerio M.J.F, Nichols R.A. Dates from the molecular clock: how wrong can we be? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.013. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn R.M, Gaston K.J, Arnold H.R. Relative measures of geographic range size: empirical comparisons. Oecologia. 1996;107:179–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00327901. doi:10.1007/BF00327901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raia P, Meloro C, Loy A, Barbera C. Species occupancy and its course in the past: macroecological patterns in extinct communities. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2006;8:181–194. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2006. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ricklefs R.E, Bermingham E. The concept of the taxon cycle in biogeography. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2002;11:353–361. doi:10.1046/j.1466-822x.2002.00300.x [Google Scholar]

- Roy K. Analyzing temporal trends in regional diversity: a biogeographic perspective. Paleobiology. 2001;27:631–645. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2001)027<0631:ATTIRD>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Sax D.F, Brown J.H. The paradox of invasion. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2000;9:363–371. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2000.00217.x [Google Scholar]

- Solow A.R. Estimation of stratigraphic ranges when fossil finds are not randomly distributed. Paleobiology. 2003;29:181–185. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2003)029<0181:EOSRWF>2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Spencer-Cervato, C. 1999 The Cenozoic deep sea microfossil record: explorations of the DSDP/ODP sample set using the Neptune database. Palaeontol. Electron 2 (available at http://www.nhm.ac.uk/hosted_sites/pe/1999_2/neptune/issue2_99.htm).

- Steadman D.W, Martin P.S. The Late Quaternary extinction and future resurrection of birds on Pacific islands. Earth Sci. Rev. 2003;61:133–147. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00116-2 [Google Scholar]

- Thuiller W, Lavorel S, Araújo M.B, Sykes M.T, Prentice I.C. Climate change threats to plant diversity in Europe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8245–8250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409902102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409902102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrba E.S, deGusta D. Do species populations really start small? New perspectives from the Late Neogene fossil record of African mammals. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2004;359:285–292. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1397. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb T.J, Gaston K.J. Geographic range size and evolutionary age in birds. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2000;267:1843–1850. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1219. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis J.C. The University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1922. Age and area: a study in geographic distribution and origin of species. [Google Scholar]

- Willis K.J, Araújo M.O, Bennett K.D, Figueroa-Rangel B, Froyd C.A, Myers N. How can a knowledge of the past help to conserve the future? Biodiversity conservation and the relevance of long-term ecological studies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2007;362:175–186. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1977. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.H, Rannala B. Bayesian estimation of species divergence times under a molecular clock using multiple fossil calibrations with soft bounds. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:212–226. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj024. doi:10.1093/molbev/msj024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]