Abstract

A growing body of evidence implicates α1-adrenergic receptors (α1ARs) as potent regulators of growth pathways. The three α1AR subtypes (α1aAR, α1bAR, α1dAR) display highly restricted tissue expression that undergoes subtype switching with many pathological stimuli, the mechanistic basis of which remains unknown. To gain insight into transcriptional pathways governing cell-specific regulation of the human α1dAR subtype, we cloned and characterized the α1dAR promoter region in two human cellular models that display disparate levels of endogenous α1dAR expression (SK-N-MC and DU145). Results reveal that α1dAR basal expression is regulated by Sp1-dependent binding of two promoter-proximal GC boxes, the mutation of which attenuates α1dAR promoter activity 10-fold. Mechanistically, chromatin immunoprecipitation data demonstrate that Sp1 binding correlates with expression of the endogenous gene in vivo, correlating highly with α1dAR promoter methylation-dependent silencing of both episomally expressed reporter constructs and the endogenous gene. Further, analysis of methylation status of proximal GC boxes using sodium bisulfite sequencing reveals differential methylation of proximal GC boxes in the two cell lines examined. Together, the data support a mechanism of methylation-dependent disruption of Sp1 binding in a cell-specific manner resulting in repression of basal α1dAR expression.

Keywords: transcription, cell, specific, promoter

Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors (α1ARs) mediate sympathetic responses to endogenous catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine, including end-organ effects such as smooth muscle contraction (1) and enhanced myocardial inotropy (2, 3). These receptors maintain tonic vessel tone (4), divert blood flow to essential organs during the fight-or-flight response (5, 6), and are important pharmacological targets in clinical management of blood pressure and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) (7). α1ARs belong to the superfamily of G protein-coupled receptors and couple predominantly via Gq; stimulation activates the phospholipase C-β pathway, leading to production of inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol, with subsequent mobilization of intracellular calcium and activation of protein kinase C (PKC), respectively (8, 9). cDNAs encoding three subtypes (α1a, α1b, and α1d) have been cloned and pharmacologically characterized. We have previously shown subtype distribution is species and tissue dependent (10–12), with expression regulated at both gene and protein levels (7). Although the regulatory regions of several α1ARs have been cloned and characterized in various models, including human (α1a (13), α1b (14)), mouse (α1a (15), α1b (16)), and rat (α1a (7), α1b (17), α1d (18)), underlying mechanisms governing species and tissue-specific AR expression remain unknown.

Aside from their well-documented pressor response functions, α1ARs play a critical role in regulation of cellular growth pathways, including hypertrophy and proliferation (9, 19–21). While many studies have focused on the role of α1aAR and α1bAR subtypes involved in these processes, a growing body of evidence implicates α1dAR as an important mediator of adrenergic function in disease. In many ways the α1dAR subtype is an atypical α1AR since it binds endogenous NE ligand with 10-fold higher affinity than the α1a or α1bAR (22) and exhibits differential signaling in many model systems, across many species (21, 23–25). Recent findings demonstrate modulation of α1dAR expression levels in various physiological and pathological states. In human bladder, for example, our laboratory has shown dramatic induction of α1dAR message and protein levels in surgically obstructed rat bladder (26). Mechanistically, enhanced α1dAR expression in bladder hypertrophy appears to occur via transcriptional subtype switching from α1aAR to α1dAR, a finding that is consistent with efficacy of α1dAR antagonists in alleviating symptoms of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) (27–31). Similarly, immortalization of human primary prostate cell cultures leads to a striking α1dAR up-regulation with concurrent α1aAR down-regulation (32), potentially linking AR subtype switching to deregulation of cell-cycle control. These observations extend to other species as the α1dAR modulates rat vascular smooth muscle cell growth (33), where specific α1dAR pharmacologic blockade or transcriptional repression by platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) results in suppression of NE-induced smooth muscle cell growth (18). Additionally, age increases functional rat α1dARs in resistance vessels (34), and data from our laboratory demonstrate up-regulation of the α1ARs with age in human vessels (12). Together, these data strongly suggest that robust transcriptional programs govern α1AR subtype levels in various physiological and pathological states and indicate an important role for α1dARs in mitogenic control and growth responses. Therefore, it is surprising that the human α1dAR gene has never been characterized.

DNA methylation at CpG dinucleotides is a prominent feature of the vertebrate genome (35). In eukaryotes, DNA methylation has been implicated in a number of distinct cellular processes, including transcriptional regulation, embryogenesis, regulation of chromatin structure (36), genomic imprinting (37), X-inactivation (38), and cancer pathogenesis (39, 40). Evidence accumulated during the past 20 years suggests an inverse correlation between transcriptional activity and methylation density, and methyl-CpG is now recognized as a gene-silencing signal (41). Specific methyl-CpGs in the promoter can prevent the interaction of transcription factors with their cognate sites. Many of the trans-factors known to bind to sequences containing CpG dinucleotides, including E2F (42), HIF-1 (43), and c-myc (44), do not bind when the CpG doublets are methylated. Accumulating evidence indicates that DNA methylation can not only interfere with factor binding but can also directly modulate chromatin structure by modifying the interaction between core histones and DNA (45, 46). Methyl-CpG-binding proteins 1 and 2 (MeCP-1 and MeCP-2) and other methyl binding domain proteins also bind preferentially to 5-methyl-CpG dinucleotides (47–50) and modulate transcriptional activity in a number of ways. Binding of these proteins can limit access to the recognition site of transcription factors or modulate DNA structure indirectly as a consequence of local binding. Indeed, recent studies show that Sp1 binding to its cognate sequence in certain genes is affected by methylation, and this binding can, in fact, be perturbed by methylation bordering the Sp1 cis-element (51, 52). In the present study, we use several independent approaches to provide evidence of differential methylation of proximal GC boxes in the human α1dAR gene that correlates with promoter activity and endogenous gene expression. Our findings demonstrate a novel mechanism of methylation-dependent disruption of Sp1 binding in a cell-specific manner resulting in repression of basal α1dAR expression. This also represents the first mechanistic description of epigenetic regulation within the adrenergic family of G protein-coupled receptors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning human α1dAR genomic DNA

Human α1dAR gene sequence was cloned directly from SK-N-MC genomic DNA into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) by LA-PCR (PanVera; Madison, WI, USA) using the following primers: forward (5′-GTGGGAATT-TCATTTCATTGCTACCCGCTACC-3′); reverse (5′-TAGA-AGGAGCACACGGAGGAGAAGACAGCGTA-3′), specific for nucleotides −6609/−6578 and + 814/845, respectively (relative to the published cDNA sequence [NM_000678]). A 7.5-kb PCR fragment was generated, containing 6.6 kb of 5′ regulatory sequence and 0.9 kb of coding sequence. The clone was sequenced and compared to a completed published sequence from the chromosome 20 contig NT_011387. Differences in human α1dAR genomic sequence isolated from SK-N-MC compared with the public database include the following: G (-6215), G (-5947), G (-4746), C (-4289), G (-1902), T (-1251), and A (-1242), relative to the ATG.

Cell culture

SK-N-MC human neuroblastoma cells and DU145 human epithelial carcinoma were grown in monolayer using MEM medium (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 nM nonessential amino acids, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and plated onto six-well culture plates at a density of 250,000 cells/well in appropriate media.

RNase protection assays

To determine the sites of transcription initiation, RNase protection assays were performed as described previously (13) using 30 μg total RNA from SK-N-MC cells. RNase protection assay Probe 1 (−203/−78), Probe 2 (−398/−203), Probe 3 (−770/−203), and Probe 5 (−1747/−1332) were generated through deletions in the cloned human α1dAR sequence. Probe 4 consists of the SmaI/BamHI fragment (−1438/−717) of the human α1dAR sequence subcloned into pGEM-7Zf (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). A human cyclophilin control probe (cyclo; Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) was used as a positive control, and a previously described human α1dAR cDNA probe (53) was used as a molecular weight marker.

Primer extension

The primer extension oligonucleotide was synthesized complementary to −1032/−1009, relative to the ATG, and end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. Assays were performed as described previously (7) using 30 μg total RNA from SK-N-MC. Extension products were separated via electrophoresis through a 6% polyacrylamide gel, with a DNA sequencing reaction generated from the same primer as a control.

Quantitative competitive RT-PCR

Competitor construction

Creation of heterologous competitor DNA constructs has been previously described (7). Briefly, a chimeric human α1dAR/pGEM-7Zf 440 bp PCR product was PCR amplified and subcloned into pCRII vector (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Chimeric primers were as follows: forward 5′-GTAGCCAAGAGAGAAAGCCGGACGCTCAAGTCA GAGGTGGCGAAACCCGA-3′ and reverse 5′-CAACCCACCACGATGCCCAGCTT CTAGTGTAGCCGTAGTTAGGCCACCAC-3′; bold sequences are specific for the human α1dAR coding sequence (residues 663– 682 and 874 – 855, respectively from ATG (54)), whereas unbolded sequence corresponds to residues 601– 630 and 971–1000 of pGEM-7Zf plasmid sequence, respectively (GenBank# X65310).

RT-PCR and quantitation of α1d AR mRNA levels

Total RNA and competitor RNA were synchronously reverse transcribed and amplified using a commercially available kit (Perkin Elmer Cetus; Redwood City, CA, USA). Control reactions with no RT were performed to ensure absence of contaminating genomic DNA. Samples were amplified, size-fractionated, and normalized to GAPDH mRNA levels as described (7). Gel photographs were digitized and normalized net band intensities transformed into an amplification ratio and plotted logarithmically vs. competitor amount. The x-intercept of the linear regression (least squares method) reflects the equivalence point where the competitor concentration equals the initial mRNA concentration.

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the TRIzol method (Invitrogen). Genomic DNA contamination was removed by digestion of RNA samples with RNase free DNase I (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA), absence of genomic DNA was confirmed by PCR using GAPDH specific primers. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was utilized to quantify alpha-1 adrenergic receptor levels. Total cellular RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using commercially available reagents (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed in duplicate using a LightCycler Instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and SYBR Green I fluorescence for detection, as described (55). Briefly, a test of optimal annealing conditions, as well as melting curve analysis, was conducted for each set of gene-specific primers. This allowed refinement of PCR kinetics and conditions for each primer pair, as well as facilitated setting the temperature for fluorescence reading between the melting temperature of potential primer-dimer formation and correct amplification product. Typically, fluorescence was acquired on channel F1 at 85°C for 2 s. Relative expression was determined by comparison to three control samples serially diluted four-fold. Abundance of each transcript was determined relative to GAPDH normalization standard. To verify amplification of the correct PCR product, amplicons were recovered after separation by electrophoresis on a 2% Tris-borate agarose gel, cloned into a plasmid, and the inserted fragment DNA sequenced. Primer sets for each gene are as follows: GAPDH forward 5′-GACCCCTTCATTGACCTCAAC-3′ reverse 5′-CTTCTCCATGGTGGTGAAGA-3 ′ α1aAR forward 5′-GTAGCCAAGAGAGAAAGCCG-3′; reverse 5′-CAACCCACCACGATGCCCAG-3′ α1dAR forward 5′-CGTGTGCTCCTTCTACCTACC-3′. reverse 5′-GCACAGGACGAAGACACCCAC-3′.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

An oligonucleotide was synthesized specific for −1234/−1162, a region encompassing two GC boxes upstream of the TIS. Wild-type dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) probe was used as a positive control (56) with either 50-fold excess of cold probe or mutant probe (Geneka; Quebec, Canada) as a competitor. Binding reactions were performed as described previously (7) with 60,000 cpm/reaction (40 fmol) probe, 2 μg antibody, and 5 μg of whole-cell lysate or 1.7 μg of HeLa nuclear extract (Geneka; Quebec, Canada). Sp1 goat IgG (sc-59x) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Transient transfections and reporter activity

Thirty minutes prior to transfection, culture medium was replaced with Opti-MEM (Invitrogen; Madison, WI, USA) serum-free medium. Cells were transfected with a 3:1 ratio (volume/mass) of Gene Juice reagent (Novagen; Madison, WI, USA) using 1 pmol of double CsCl banded reporter plasmids and 0.5 pmol of β-galactosidase plasmid, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were washed and maintained in appropriate medium. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were harvested and luciferase and β-galactosidase activity measured, as described using Dual-Light Assay System (Tropix; Bedford, MA, USA). Transfection efficiency was determined to be >20% by visual staining for β-galactosidase.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Primers spanning the −1192/−1162 (forward: 5′-GAC-TGTCTCACACCC[b]TTTCCGCTTAACCATC-3′, reverse: 5′-GATGGTTAAGCGG[b]AAAGGGTGTGAGACAGTC-3′) and −1233/−1204 regions (forward: 5′-CTGTTAATATGG-[b]AAAGGAGCCTGGATTCAG-3′, reverse: 5′-CTGAATC-CAGGCTCC[b]TTTCCATATTAACAG-3′) were generated containing three mutations (bold) in the GC box consensus sequence. Both were purified by electrophoresis through a 6% polyacrylamide gel and desalted over Sephadex G-25 columns (Roche; Indianapolis, IN, USA). Mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), with 12 ng of the −1972 deletion construct as template. XL10 Gold Ultracompetent cells (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA, USA) were transformed with 2 μl of sample reactions, and resultant mutants confirmed by sequencing. The region containing the mutations was excised with PmlI/RsrII and subcloned into the full-length reporter and sequenced to ensure the absence of unwanted mutations.

5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-azaCdR) treatment

SK-N-MC and DU145 cells were plated 24 h before beginning treatment. The cells were treated for 48 h with different concentrations (from 0.1 to 1 μM) of DNA methyl transferase inhibitor 5-azaCdR (Sigma). Subsequently, cells were harvested for total RNA isolation using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For quantitating total receptor levels, radioligand binding was performed, as described (57). Saturation binding was performed with the radiolabeled α1AR antagonist [125I]-HEAT (300 pM) using cell membranes prepared from DU145 and SK-N-MC cells treated with either vehicle or 5-azaCdR for 48 h.

Methylation of promoter/reporter constructs

The human α1dAR promoter/luciferase reporter construct (pGL2–6663) was in vitro methylated using M. HpaII (Cm-CGG), and M. SssI (mCG) methylases following the recommendations of the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). Mock methylation reactions did not contain any methylase. The methylation status of the constructs was verified using HpaII and MspI. Methylated and mock-methylated constructs were phenol/chloroform-purified and precipitated in ethanol before transient transfection experiments.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

To investigate transcription factor binding in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation exactly as described (58). Briefly, formaldehyde was added to culture medium at a final concentration of 1% for 10 min at 25°C, and cross-linking was stopped by incubating in 0.125 M glycine-PBS for 5 min. Cells were rinsed, sonicated on ice, pelleted by centrifugation, and supernatant collected. Lysates were pre-cleared with protein G beads (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) for 1 h at 4°C and subsequently added to preblocked Protein-G beads with either 1.6 μg of Sp1 rabbit IgG (sc-59 and sc-644 respectively) from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or 1.6 μg of Flag IgG (Sigma; St. Louis, MO, USA) and rotated for overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed, treated with 50 μg proteinase K for 2 h at 55°C, and cross-links reversed overnight at 65°C. DNA was recovered, ethanol precipitated with glycogen carrier, and resuspended in water.

The human α1dAR gene was detected by PCR using primer sequences corresponding to nucleotides −335/−310 and −25/−50, respectively, relative to ATG. To control for nonspecific Sp1 immunoprecipitation, we utilized the human MAT1A gene (GenBank AF110500) that lacks Sp1 consensus sites and is unresponsive to Sp/KLF regulation (59). Promoter proximal MAT1A primers were specific for the −554/−159 region, relative to ATG as a negative control. A dilution curve was performed to determine the linear range of amplification. Reverse cross-linked chromatin prior to immunoprecipitation was used as a positive control (input) for human α1dAR and MAT1A PCR amplification.

Bisulfite treatment of DNA samples

Bisulfite treatments were performed as described (60) with minor modifications. Briefly, genomic DNA (1 μg) was denatured in 0.2 M NaOH at 42°C for 20 min and then mixed with 10 mM hydroquinone (Sigma) and 3 M sodium bisulfite (pH 5.0; Sigma). Reactants were incubated at 55°C for 18 h, and bisulfite-modified DNA was purified using the Wizard purification resin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and eluted into water. After addition of 3 M NaOH (final 0.3 M), samples were ethanol precipitated and resuspended in water. A fragment of genomic DNA encompassing the two proximal Sp1 sites (−1234 to −1162) was amplified using the following primer pairs: wild-type forward, 5′-GGCCAGGAGGTAGACATCACTTCTT-3′; and reverse, 5′-TGTATCAGATGCGGGAATAAACCTT-3′. The two primer pairs for strand-specific amplification of bisulfite treated DNA were as follows: Bis coding forward, 5′-GGTTAGGAGGTAGATATTATTTTTT-3′ Bis coding reverse, 5′-TATATCAAATACAAAAATAAACCTT; Bis noncoding forward, 5′-AACCAAAAAATAAACATCACTTCTT-3′ and Bis noncoding reverse, 5′-TGTATTAGATGTGGGAATAAATTTT-3′. PCR products amplified from both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells were cloned into pCR II (Invitrogen) and sequenced.

RESULTS

Cloning of the human α1dAR 5′-regulatory sequence and identification of the proximal promoter

To begin studies underlying cell-specific expression of α1dARs, we first characterized the promoter region. To begin this process, we cloned a 7.5-kb fragment (6.6-kb upstream of the ATG) from genomic DNA. To determine the site of transcription initiation and delineate the 5′-regulatory sequence, several overlapping probes spanning the 5′-UTR were utilized in RNase protection assays (Fig. 1A). Use of Probe 4 yielded one major protected fragment, corresponding to a primary transcription initiation site 1097 bp upstream of the ATG (Fig. 1B, arrow, MP). Three clusters of higher and lower molecular weight fragments were also detected (Fig. 1B, brackets A, B, and C), indicating heterogeneity of initiation sites centered on the major product. More proximal probes generated fully protected products, while the more distal Probe 5 generated no protected fragments, suggesting that the human α1dAR gene is transcribed from a single major promoter, centered ~1100 bp upstream of the initiation methionine with heterogeneity in initiation sites (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Identification of transcription initiation site (TIS) of human α1dAR gene. A) Schematic representation of RNase protection assay (RPA) probes used for identification of the TIS. Restriction sites used in generation of RPA probes 1–5 are indicated. Primer location for primer extension analysis is indicated by a dashed arrow. B) Identification of the proximal promoter TIS by RPA. Total RNA (30 μg) from SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells (SK-N-MC) was hybridized to probe 4 at 55°C. Yeast tRNA (tRNA) was used as a negative control (lanes 4 – 6). Molecular weight marker (MW) was a 5′ end-labeled HaeIII digest of ΦX. One major protected fragment was identified, indicated by an arrow. An α1dAR cDNA probe (cDNA) was used as an additional molecular weight marker that comigrates with the major protected fragment in the promoter region (377 bp). Higher-molecular-weight minor products are indicated by bracket (2–7). Cyclophilin (cyclo) was used to control for RNA integrity and produces a protected fragment of 103 bp (lane 3). Unprotected probes are shown for reference (Probe, lanes 7–9). C) Primer extension assays were performed with an anti-sense oligonucleotide using 30 μg total RNA from SK-N-MC cells with yeast tRNA as a negative control. Radiolabeled primer was hybridized at 65°C overnight and extended with MMuLV reverse transcriptase. A DNA-sequencing reaction using the same primer and the cloned human α1dAR 5′UTR is shown on the left as a base pair marker. Several products were detected (1–9) with band 3 (underlined) corresponding to the product 1 detected by RPA (Fig. 1B, arrow).

Primer extension was performed to confirm RPA results (Fig. 1C) using an antisense oligonucleotide primer −1032/−1009 relative to the ATG. Several products were detected, with one corresponding to the major protected fragment detected by RPA (band 3, Fig. 1C). A base pair sequencing ladder maps this exact site at adenosine −1097 (relative to ATG) within a sequence (AG[b]AACAA), which closely matches the consensus initiator (Inr) sequence PyPyA (+1)NT/APyPy (61). The upstream transcription initiation site (TIS) cluster was also confirmed by primer extension analysis; however unlike RPA results, extension products correlating with clusters A and B were more highly represented than the predominant product detected by RPA. These results were obtained from several independent experiments under stringent hybridization conditions, indicating genuine α1dAR extension products. It is important to note that despite the discrepancy in relative intensity of RPA and primer extension products, the fragments detected by both methods correspond to a tightly grouped cluster of transcription initiation sites that highly correlate with one another. Differences in product intensities could potentially be due RNA secondary structure that may result in hairpin-loop formations favoring probe cleavage at −1097 in the enzymatic RPA approach, but would affect extension products to a much lesser degree. Lower-molecular-weight products in primer extension reactions may either represent premature termination during extension through areas of high GC-content (Fig. 1C, asterisks) or bona fide initiation sites (Fig. 1C, bands 1 and 2). We detected no extension products correlating with cluster C (Fig. 1B), which is thought to represent spurious enzymatic cleavage products. Thus, we designate the TIS to be a cluster of initiation sites ~1100 bp upstream of the initiation methionine with specific start points at A-1131, A-1125, A-1120, and A-1097, T-1082, A-1069. For convention, we designate the major TIS identified by RPA to be A-1097.

Cell-specific expression of human α1dAR mRNA

Previous studies from our laboratory have established relative expression levels of endogenous α1dAR levels in several model cell lines; we now wished to determine absolute endogenous α1dAR mRNA levels for these cellular model systems using competitive RT-PCR (cRT-PCR), as described in Materials and Methods. While α1dAR expression is robust in SK-N-MC cells, 17.6 ± 2.0 pg α1dAR mRNA/μg total RNA expression in DU145 cells is almost absent (0.662±0.087 pg mRNA/μg total RNA, Fig. 2). This corresponds to a 26.6-fold decrease of α1dAR mRNA in DU145 by cRT-PCR and is highly consistent with previously reported results from RNase protection assays on these same cell lines (13). Because SK-N-MC cells and DU145 display differential expression, these cell lines were utilized for further mechanistic, cell-specific expression studies.

Figure 2.

Cell-specific expression of the humanα1dAR Gene. Representative quantitation of α1dAR mRNA by competitive RT-PCR Total RNA from SK-N-MC and DU145 cells was coamplified with serial dilutions of competitor RNA (cRNA) for 35 cycles. Two-hundred ng of total RNA from SK-N-MC cells was synchronously amplified with 0.032, 0.18. 0.6, 4, 20, and 100 pg cRNA (lanes 1–5, respectively); 400 ng of DU145 total RNA was synchronously amplified with 0.032, 0.18. 0.6, 4, and 20 pg cRNA (lanes 8–12). GAPDH was amplified with each sample set in a separate reaction using 200 or 400 ng of total RNA for normalization purposes (lanes 7 and 14). Competitor concentrations were used to obtain a standard line to calculate the initial amount of target RNA in each sample. Reverse transcriptase controls (noRT) were included to ensure no contaminating genomic DNA (−RT, lanes 6 and 13).

Cell-specific promoter activity

To delineate regions controlling basal gene expression, full-length and serial 5′-deletion reporter constructs were transiently transfected into SK-N-MC cells and reporter expression quantified. Results show that the full-length promoter confers a 13.5-fold increase over pGL2E empty vector (Fig. 3, white bars). Deletion to −5374 increases expression 101% (P<0.01) above basal, implying repressor activity in the −5870/−5374 region. Further removal to −3643 reduces reporter gene activity to similar levels as the full-length construct, suggesting the presence of an enhancer in the −4662/−3643 sequence. Truncation to −2204 induces expression by 106% relative to the full-length construct (P≤0.01), consistent with a repressor element in the −2924/−2204 region. Further truncation to −1972 results in a 56% decrease (P<0.01) relative to the −2204 construct; however, this is and additional deletion to −1470 is statistically indistinguishable from the full-length promoter. Finally, deletion beyond the putative TIS to −770 completely abrogates expression, consistent with our designation of the promoter, centered 1100 bp upstream of the ATG (data not shown). Thus, we designate −1470 the minimal α1dAR promoter.

Figure 3.

Deletion analysis of the human α1dAR 5′-regulatory region. Full-length 6.6-kb or 5′-serial deletion reporter constructs were cotransfected with β-galactosidase reporter plasmid into SK-N-MC (white bars) and DU145 (gray bars) cells. Luciferase expression was normalized to β-galactosidase and expressed as fold over basal pGL2 enhancer plasmid (mean±sem, n=3–5, P<0.01). The schematic illustrates the location of key consensus sequences and indicates the length of each construct expressed in the graph.

To examine cell-specific human α1dAR promoter activity, DU145 cells were used. Surprisingly, despite low α1dAR mRNA in DU145 cells compared to SK-N-MC cells (refer to Fig. 2B), high levels of human α1dAR promoter activity in DU145 cells are seen, with promoter activity of the full-length construct exceeding that of SK-N-MC cells. (Fig. 3, compare white vs. gray bars; significantly greater for the full-length (P=0.011), −4662 (P=0.0088), −2204 (P<0.05), and −1470 (P<0.05) constructs). Thus, both cell types express factors capable of supporting high levels of α1dAR transcription despite the disparate expression of endogenous α1dAR mRNA. Although a host of processes could play a role in this observation, we first examined transcriptional regulation using the created reporter constructs to identify soluble factors regulating α1dAR basal expression.

Specific binding of Sp1 to GC-rich elements

Two GC boxes located −83 and −125 bp upstream of the putative transcription initiation site are identical matches to known functional GC box in the DHFR promoter (Fig. 4A) (56). Thus, we examined a role for Sp1 in the differential expression of α1dAR mRNA in SK-N-MC vs. DU145 cells. In vitro binding was performed by electrophoretic mobility shift assays with SK-N-MC whole-cell extracts using an oligonucleotide probe spanning this region. As Fig. 4B shows, the addition of cell extract results in formation of protein-DNA complexes (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 and 7). Excess cold competitor, an oligonucleotide containing a known GC box from the DHFR promoter, abrogates the top and middle bands (Fig. 4B, lane 3), but excess mutant competitor has no effect (Fig. 4B, lane 4). These results indicate that the protein-DNA interactions are specific for the GC box sequence in the top and middle complexes, whereas the bottom band is nonspecific. The addition of Sp1 antibodies generated a supershift of the top band (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 8) that was blocked by excess Sp1 epitope (Fig. 4B, lane 6), demonstrating specific binding of Sp1 to the probe. Addition of Sp1 antibody did not attenuate the middle complex, suggesting site-specific binding by another protein. Characterization of this latter shift reveals that Sp3 is also able to specifically bind to the GC-element in the human α1dAR promoter (data not shown). We are currently conducting studies to assess the biological relevance of this binding.

Figure 4.

Binding of Sp1 to GC boxes in the human α1dAR 5′-regulatory region. A) Schematic of α1dAR GC box. B) Sp1 binds to promoter proximal α1dAR GC boxes. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from SK-N-MC cells. Five micrograms of extract and 60,000 cpm oligonucleotide probe were used in each reaction and protein: DNA complexes were size fractionated on a 6% native acrylamide gel at 4°C. Shifts were competed with either 50-fold molar excess of cold wild-type DHFR probe or an oligonucleotide containing mutations in the Sp1 binding site (X). Sp1 binding was detected using 2 μg specific antibody (sc-59x) and 2 μg blocking peptide. C) Binding of Sp1 to promoter proximal α1dAR GC boxes in multiple cells. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from SK-N-MC, DU145, rat1-fibroblasts, and HeLa (positive control) cells. Samples were prepared as described above.

To examine the role of Sp1 binding in the observed cell-specific expression of the human α1dAR gene, we performed shift assays using nuclear extracts from SK-N-MC (high α1dAR expression), DU145 (low expression), and rat1-fibroblasts (no endogenous α1d mRNA expression). Results reveal a similar binding profile for each extract using the human α1dAR GC-rich elements as a probe, showing that Sp1 binding activity is comparable in SK-N-MC, DU145 cells, and rat1-fibroblasts (Fig. 4C). HeLa extract was used as a positive control for the presence of Sp1, and Fig. 4C, lanes 7 and 8 reveal the same shift or supershift as with the nuclear extracts from the other cellular models examined. Labeled DHFR probe was run in parallel for all conditions as a control for mobility shift, and resulted in the same pattern as that for the α1dAR (data not shown). These results demonstrate specific in vitro binding of both Sp1 to the GC boxes immediately upstream of the human α1dAR proximal promoter for all cell lines examined.

Sp1 overexpression and site-directed mutagenesis

To confirm a functional role for Sp1 binding, an expression vector encoding Sp1 was cotransfected with full-length and −1470 reporter constructs in SK-N-MC cells (Fig. 5). To create conditions where endogenous Sp1 would become limiting, a titration curve was performed with increasing reporter plasmid and experimental parameters were found where linear relationship between increasing reporter plasmid and reporter gene activity was no longer seen (data not shown). Under these conditions (2 pmol reporter gene), Sp1 overexpression results in a 41% increase in full-length reporter and a 133% increase in the −1470 constructs (Fig. 5). Results from experiments in DU145 cells reveal a similar profile of reporter gene activity. Mutation of the two proximal GC boxes significantly reduced expression by 49% (P<0.01) in the 6.6-kb full-length reporter construct (Fig. 5B). Because this construct contains several powerful enhancer and repressor elements that could confound or mask results, the GC mutants were also introduced into the −1470 promoter construct, containing the least amount of regulatory sequence. In this context, loss of the GC boxed resulted in a dramatic 93% decline in expression from the −1470 promoter decrease (P<0.01), indicating a central role for these cis-elements in regulation of basal α1dAR transcription (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Sp1-dependent regulation of the human α1dAR promoter. A) Sp1 is able to transactivate the human α1dAR promoter. The full-length −6663 (2 pmol/15.5 μg) and −1470 (2 pmol/9.1 μg) constructs and pGL2 enhancer empty reporter (2 pmol/6.8 μg) were cotransfected into SK-N-MC cells with either Sp1 expression vector (dark) or empty pCDNA3 expression vector (light). Luciferase expression was normalized to β-galactosidase activity and expressed as fold over basal pGL2 enhancer plasmid (mean±sem, n=3, P<0.01). Overexpression of Sp1 increased luciferase reporter activity by 41% from the full-length promoter and by 133% from the minimal promoter (P<0.01). B) Proximal GC boxes necessary for maximal levels of α1dAR basal expression. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to create mutations in two GC boxes immediately upstream of the primary transcription initiation site. GC boxes are shown in the schematic with the boxed regions mutated to “AAA” or “TTT,” respectively. Mutations are indicated at left (X) and were verified by DNA sequencing. Both full-length and minimal promoter mutant constructs were transiently transfected into SK-N-MC cells. Luciferase expression was normalized to β-galactosidase and expressed as fold over basal pGL2 enhancer plasmid (mean±sem, n=4). Mutation of the Sp1/Sp3 binding site reduces expression by 49% and 93% from the full-length and minimal promoter reporters respectively (P<0.01).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Because Sp1 binding activity is present in both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells and is necessary for full α1dAR promoter activity in a GC box-dependent manner in vitro, we next wished to investigate whether Sp1 binds the α1dAR proximal promoter region in vivo. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP), we immunoprecipitated Sp1 bound to chromatin and used PCR to detect enrichment for the α1dAR gene. For a negative control, the MAT1A gene was used since it lacks any consensus Sp1 binding sites in the promoter region and has never been described to be Sp1 responsive. As shown in Fig. 6, both MAT1A and α1dAR fragments are amplified from the input chromatin in multiplexed PCR reactions (Fig. 6, input). Immunoprecipitation of sonicated chromatin with anti-Sp1 from both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells, and subsequent multiplex PCR, reveals amplification of α1dAR proximal promoter only in SK-N-MC cells. Flag antibody alone was unable to immunoprecipitate DNA from either cellular source (Fig. 6, αFlag). This provides strong evidence that Sp1 is bound to the proximal GC boxes in vivo in SK-N-MC cells but is not bound to DU145 promoter under normal growth conditions. These data show a strong correlation between Sp1 binding in vivo and expression of the endogenous α1dAR gene. Coupled with previous data, our results suggest the presence of epigenetic processes that differentially govern basal expression of the human α1dAR gene. Given the high GC content (68% overall; 81% in the promoter proximal 500 bp) of the human α1dAR promoter, we next explored the possibility of epigenetic regulation by CpG methylation.

Figure 6.

Cell-specific binding of Sp1 to α1dAR GC boxes in vivo. SK-N-MC and DU145 cells were formaldehyde cross-linked and sonicated as described in Materials and Methods. Cleared lysates were immunoprecipitated with protein-G agarose and Sp1 or Flag antibodies. A portion lysate was reserved as a positive control for PCR analysis (input). Chromatin was eluted from washed beads, treated with proteinase K, crosslinks reversed, and DNA was precipitated. PCR was used to detect enrichment using primers specific for the human α1d proximal promoter. Primers for a region of the methionine adenosyl transferase (MAT1A) gene lacking GC boxes were used as a negative control.

Methylation suppresses α1dAR promoter activity

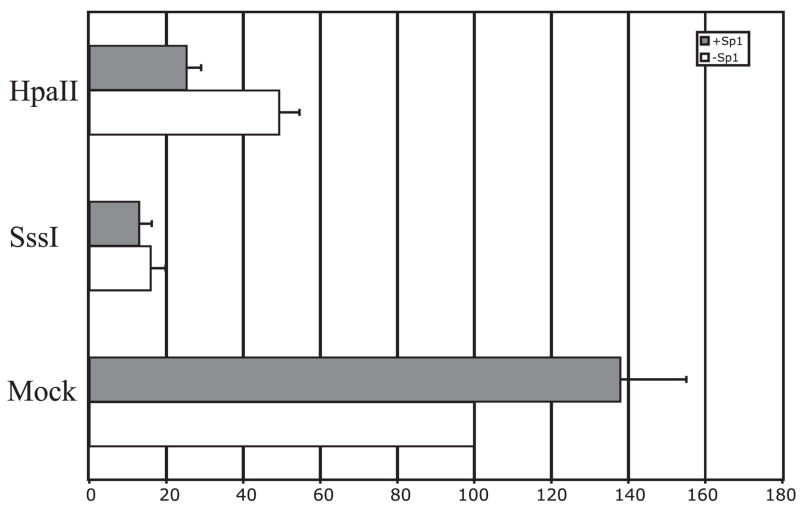

To assess the role of methylation α1dAR expression, the full-length α1dAR reporter construct was methylated by either partial methylase HpaII or full methylase SssI in vitro and subsequently transfected into SK-N-MC cells. In vitro methylation of the reporter construct induced an 48% reduction in promoter activity compared with a mock-methylated construct, whereas full methylation of the constructs with SssI suppresses α1dAR promoter activity by 82%, indicating that methylation of the promoter can repress α1dAR transcription in a methylation-dependent manner (Fig. 7, white bars).

Figure 7.

Repression of α1dAR promoter-driven transcription by CpG methylation. Full-length human α1dAR reporter plasmid was mock-methylated (Mock) or in vitro methylated with HpaII or SssI methylase and transfected (1 pmol) into SK-N-MC cells in the presence of Sp1 or empty expression plasmid (pcDNA3). Results are given as a percentage of mock-treated, full-length reporter plus pcDNA3 expression vector. Data are normalized to cotransfected β-galactosidase activity and are expressed as mean ± se (n=3).

To examine the role of methylation in Sp1-dependent regulation of α1dAR promoter activity, we cotransfected Sp1 expression vector with mock-treated and methylation α1dAR reporter plasmid under conditions where Sp1 levels would again be limiting. Results reveal that Sp1 is able to again transactivate mock-treated reporter plasmid 36%, but this increase in reporter activity is completely attenuated by both partial and full methylation (Fig. 7, gray bars). Together, the data demonstrate that methylation is sufficient to block Sp1-dependent transactivation of the human α1dAR promoter.

5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-azaCdR) induces endogenous α1dAR mRNA and protein expression in DU145 cells

To delineate the role of methylation in vivo, hypomethylation of genomic DNA was induced by the potent inhibitor of DNA methyltransferase, 5-azaCdR, in SK-N-MC and DU145 cells (1 μM, 48 h). Real-time RT-PCR was used to assess the effects of 5-azaCdR treatment on steady-state α1dAR mRNA expression. In the presence of vehicle control (ethanol), we confirmed the significant difference in steady-state mRNA levels between the two cells, with SK-N-MC cells expressing at 23.8 higher levels than DU145 cells (Fig. 8A, white bars), matching closely with previously shown cRT-PCR results (Fig. 2). However, 5-azaCdR treatment induces a dramatic increase in α1dAR mRNA levels in DU145 cells, with expression increasing 43.4-fold versus vehicle control and 1.8-fold higher than SK-N-MC cells (Fig. 8, dark bars; n=3). In contrast, expression of endogenous α1dAR mRNA levels in SK-N-MC cells is statistically unaffected by treatment with 5-azaCdR. To show specificity of response, we next examined endogenous α1aAR mRNA levels in these same cell types. Results show that α1aAR mRNA levels are below the threshold of detection by PCR in DU145 cells and that treatment with 5-azaCdR had no effect on these levels (Fig. 8A, compare white and dark bars in DU145 with α1aAR). Similarly, 5-azaCdR treatment had little effect on endogenous α1aAR mRNA levels in SK-N-MC cells, although expression levels were much higher in SK-N-MC cells vs. DU145 (Fig. 8A, compare white bars for α1aAR in DU145 vs. SK-N-MC).

Figure 8.

Inhibition of methylation derepresses endogenous α1dAR expression. A) 5-azaCdR Induces α1dAR mRNA in DU145 cells in a subtype dependent manner. Real-time RT-PCR was used to relatively quantitate α1aAR and α1dAR steady-state mRNA levels in SK-N-MC and DU145 cells following 5-azaCdR treatment (1 μM, 48 h), as described in Materials and Methods. White bars represent samples that were treated with control (ethanol) while gray bars represent 5-azaCdR-treated samples. α1dAR copy number was quantified by comparison with a standard curve and values were normalized to the copy number of GAPDH. Values are expressed as fold-over DU145 vehicle and are expressed as the mean ± se (n=5). B) 5-azaCdR induces corresponding α1AR protein expression in DU145 cells. Total α1AR receptor levels were quantitated using radioligand binding in SK-N-MC and DU145 cells following 5-azaCdR treatment (1 μM, 48 h), as described in Materials and Methods. White bars represent samples that were treated with control, while gray bars represent 5-azaCdR-treated samples. Values are expressed as fold-over DU145 vehicle and are expressed as the mean ± se (n=3)

Given the often disparate expression between mRNA and corresponding protein levels, we next examined if the dramatic increase in endogenous α1dAR mRNA levels correlated with a corresponding increase in receptor levels. Accordingly, parallel experiments were set up whereby a portion of the samples to be analyzed for mRNA levels were taken and assayed for receptor levels. Because of very low levels of α1AR receptor expression in both SK-N-MC cells and DU145 cells, Western blot analysis is insufficient to provide the sensitivity to detect receptor levels; thus, it was necessary to use radioligand binding assays. Results show that receptor levels increased 2.2-fold with 24-h 5-azaCdR treatment (data not shown) and 6.5-fold in DU145 cells with the identical 48-h treatment used to assay mRNA levels (Fig. 8B, compare white and dark bars). Receptor levels in SK-N-MC cells were statistically unchanged regardless of treatment (Fig. 8B, compare white and dark bars). Taken together, these results suggest that DNA methylation plays a key role in silencing α1dAR endogenous expression levels both at the mRNA, as well as receptor levels in DU145 cells and that inhibition of DNA methyltransferase activity is sufficient to derepress expression levels to those seen in SK-N-MC cells.

Methylation status of the human α1dAR promoter

EMSA data indicated that Sp1 is indeed present in both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells; however, ChIP results revealed that Sp1 was able to interact with the human α1dAR GC boxes only in the former cells. Taken together with 5-azaCdR, data suggesting a role for methylation on the regulation of α1dAR expression, we next wished to investigate the methylation status of the proximal GC boxes using sodium bisulfite sequencing, a reagent that preferentially deaminates unmethylated cytosine to uracil, but 5-methylcytosine remains unreactive (60). DNA from both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells were examined in the region containing the proximal GC boxes. Results revealed that SK-N-MC cells are hemimethylated at two locations on the noncoding strand, one in Sp1–2 box, as well as a site between the two GC boxes (Fig. 9A, closed circles on SK-N-MC A-T primer sequence). CpG dimers in DU145 cells, however, are more extensively methylated on both coding and noncoding strands in both Sp1–1 and Sp1–2 sites vs. SK-N-MC cells (Fig. 9B, closed boxes). The data support a mechanism of methylation-dependent regulation of Sp1 binding that governs basal expression of the human α1dAR gene.

Figure 9.

Sodium bisulfite sequencing reveals differential methylation of proximal Sp1 binding sites of the human α1dAR promoter. A) DU145 cells display more extensive methylation pattern vs. SK-N-MC cells. Genomic DNA was isolated from both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells and subjected to sodium bisulfite treatment, as described in Materials and Methods. Bisulfite treatment alters unmethylated cytosine residues in CpG dinucleotides to uracil, which are detected using strand-specific primers for each strand. Using wild-type and methylation-specific primers, PCR products were amplified from both samples, subcloned, and sequenced (n=4 for each cell line). The unmethylated cytosines on the coding (top) strand and the noncoding (bottom) strand are indicated by arrowheads. Closed circles indicate methylated cytosines that are protected by bisulfite oxidation and remain cytosine. Note that DNA from SK-N-MC cells is hemimethylated in Sp1–2 relative to fully methylated DNA in DU145 cells that is more extensively methylated in both GC boxes. B) Summary of bisulfite treatment data. Sequence for the proximal GC boxes is shown with all CpG dinucleotides indicated by arrows. Diamonds indicate cytosine methylation in both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells. Differentially methylated cytosines in DU145 cells are indicated by filled boxes, found both on coding and noncoding strands in both GC boxes (Sp1–1 and Sp1–2).

DISCUSSION

Given the growing body of evidence showing differential effects of the three αlAR subtypes on cell-cycle progression and growth signaling (13, 21, 62–64), it has become increasingly important to elucidate the mechanisms governing the well-documented tissue- and cell-specific regulation of this family of receptors to understand the dynamic crosstalk among ARs. To this end, we cloned and characterized the human α1dAR promoter and 5′-UTR to elucidate transcriptional pathways governing αldAR expression. We find that the human α1dAR promoter lacks a TATA or CAAT box, similar to other αlAR genes and many housekeeping genes (7, 13, 17, 18, 65, 66), with transcription initiated from a tightly grouped cluster of sites, and with the predominant site located 1097 bp upstream of the ATG (adenosine/−1097) that we designate the predominant promoter. This residue falls within an imperfect Inr consensus sequence, which may explain the observed TIS heterogeneity, as the atypical sequence may represent a weak promoter similar to the recently described rat α1aAR gene (7).

We identified two GC boxes immediately upstream of the TIS conforming to Sp/Krüppel-like factor (KLF) binding sites that are bound by Sp1 both in vitro and in vivo. Promoter proximal Sp1 binding sites have been proposed to serve as anchors that recruit basal transcription factors (66) and likely serve a similar role in the α1dAR gene. Supporting a key role for the proximal GC boxes in Sp1-dependent α1dAR basal regulation, overexpression of Sp1 increased expression by 2.3-fold in an α1dAR minimal-promoter reporter construct, while site-specific mutation of these elements decreased expression by over 10-fold. Contrary to in vitro binding assays that show strong and specific binding of Sp1 to these sites in all cell lines examined, ChIP analysis reveals that Sp1 binding in vivo to the proximal GC boxes is a regulated event that correlates with endogenous gene expression. Mechanistically, we show that methylation of the α1dAR promoter correlates with silencing of both episomally expressed reporter constructs and the endogenous gene. Consistent with these results, we find that the proximal GC boxes are preferentially methylated in DU145 cells, strongly correlating with repression of α1dAR expression. Together, the data support a mechanism of methylation-dependent perturbation of Sp1 binding to the α1dAR promoter in a cell-specific manner and represent the first mechanistic description of epigenetic regulation of an AR gene.

Sp1 can function as a potent transcriptional activator by interacting directly with the TFIID complex (67, 68); however, regulation of Sp1-bound cis-elements is complicated by the fact that other Sp/KLF family members, as well as other factors, such as early growth response gene (Egr)-1 (70), can compete for these same sites, each possessing different effector domains. Within the α1AR family, Gao and Kunos examined the mechanistic basis of Sp1 cell-specific expression of the rat α1bAR promoter. Analysis of the predominant P2 promoter revealed that binding of NF1 proteins to the P2 region is tissue specific; NF1/X is able to bind to footprint II in liver extracts, but this same region is bound by Sp1 in extracts from DDT1-MF-2 hamster smooth muscle cells (70). However, in the current study, two pieces of evidence suggest that binding site competition for the promoter proximal GC boxes is not involved in Sp1-dependent α1dAR regulation in SK-N-MC vs. DU145 cells. First, EMSA analysis reveals that both SK-N-MC and DU145 cells display robust Sp1 binding to the promoter proximal GC boxes, even in the presence of endogenous Sp3, excluding cell-specific Sp1 binding. Second, overexpression of Sp3 in our model system has little impact on reporter gene activity and was not able to displace endogenous Sp1 binding (data not shown). The robust in vitro Sp1 binding, coupled with ChIP data showing differential Sp1 binding in vivo in SK-N-MC cells vs. DU145, suggested the presence of epigenetic mechanisms governing regulation of basal α1dAR expression; the high GC content of the promoter region led us to investigate cytosine methylation. Heritable patterns of CpG methylation have been shown to repress transcription by blocking the access of transcription factors and inducing the formation of inactive chromatin (71). Specifically, we demonstrate that in vitro methylation of the human α1dAR promoter represses basal transcriptional activity in transfected cells and that methylation is sufficient to block Sp1-dependent transactivation (Fig. 7). Consistent with a central role for methylation in regulation of basal α1dAR expression, we found that the two proximal Sp1 sites are preferentially methylated in DU145 cells and 5-aza-CdR treatment induces a 43.4-fold increase in α1dAR mRNA levels in DU145 cells, while endogenous α1dAR mRNA levels in SK-N-MC cells were unaffected (Figs. 8 and 9). Supporting a biological role for this effect, total α1AR receptor levels increased 6.5-fold, correlating well with increases in α1dAR mRNA expression. Although, radioligand saturation binding does not distinguish between the different α1AR subtypes, given that expression of α1aAR and α1bAR subtypes is undetectable at the mRNA level in DU145 cells, coupled with the high correlation with α1dAR mRNA levels, the data strongly indicate the increased receptor levels are due to increased α1dAR expression. Collectively, these results suggest that DNA methylation plays a key role in silencing α1dAR endogenous expression levels in DU145 cells and that inhibition of DNA methyltransferase activity is sufficient to increase α1dAR mRNA and protein levels in DU145 cells to those seen in SK-N-MC cells.

Although never described for adrenergic receptor regulation, DNA methylation has been shown to interfere with the binding of regulatory proteins (72), including Sp1 and Sp3. Indeed, recent studies have shown that increased binding activity of Sp1/Sp3 occurs subsequent to 5-azaCdR-mediated demethylation, either directly via DNA perturbation (51, 52) or via changes at Sp1/Sp3 protein levels (49, 73–75). Additionally, Sp1 activity is also found to be affected by neighboring methylation and histone acetylation events. For example, methylation of the human leukosialin gene leads to binding of methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 that represses Sp1 activation (76). Sp1 has also been demonstrated to maintain CpG islands in the mouse adenine phosphoribosyltransferase gene by protecting CpG island from de novo methylation, thereby acting as a derepressor (77). Alternatively, methylation can affect gene expression directly by interfering with transcription factor binding and/or indirectly by recruiting histone deacetylases (HDACs) through methyl-DNA-binding proteins (75). Using methylase (5-azaCdR) and HDAC (depsipeptide) inhibitors, a recent report advances a model where Sp1 binding to the p21(Cip1) promoter in a methylation sensitive step is required for HDAC-mediated activation of p21(Cip1) expression (75). Additionally, the luteinizing hormone receptor (LHR) provides another model that tethers DNA methylation and histone deacetylation to provide synergistic activation of expression. In an intriguing set of studies, an Sp1 site was identified as a binding site for histone deacetylase (HDAC) and mSin3A corepressor (78); the authors then showed that a critical response element is preferentially methylated in cells where LHR expression is repressed and the authors delineate a mechanism whereby release of the HDAC/mSin3A complex from the Sp1 site and increase of TFIIB association to the LHR gene promoter occurred in a promoter demethylation-dependent manner. We are currently in the process of investigating the potential role of histone modification in the dramatic derepression of α1dAR mRNA levels in DU145 cells on 5-azaCdR treatment, and it will be of interest in future studies to perform hypomethylation footprints experiments to determine whether Sp1 helps maintain regions of DNA methylation-free. Taken together, the data suggest a complex array of signals and processes that enable Sp/KLF proteins to integrate multiple signals and pathways resulting in recruitment of the appropriate constellation of transcription factors to yield proper mRNA levels of Sp/KLF responsive genes.

The literature is replete with confounding results, indicating differential effects of α1AR subtypes on growth responses. Although these effects are highly tissue dependent, it is clear that α1AR expression levels have a profound impact on growth signaling. Indeed, several lines of evidence suggest that α1dAR plays a key role in the regulation of pathways governing the transition from cellular homeostasis to active growth. We have previously reported a dramatic subtype switch in a rat bladder obstruction model where α1aAR mRNA levels decrease with a concurrent up-regulation in α1dAR that correlates with severe bladder hypertrophy (26). Pharmacologic antagonism of the α1dAR subtype improves bladder hypertrophy and function, supporting a mechanistic role for α1dAR in the development of growth-related bladder pathologies. Additional studies in our laboratory showed that immortalization of human prostate smooth muscle cells produced parallel phenomena, where α1aAR mRNA repression was accompanied by a compensatory increase in α1dAR gene expression (32). Thirdly, using a tritiated thymidine incorporation assay in transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, the Michel laboratory showed that α1dAR mediated growth stimulation, while α1aAR displayed growth inhibition (23). A more recent study, also in CHO cells that stably express human α1ARs, similarly revealed differential control of cell-cycle progression in a cAMP/p27kip1-dependent mechanism (21). Thus, while α1aAR and α1bAR are antiproliferative, α1dAR is unique in that proliferative signaling is sustained (21, 23). Interestingly, however, α1ARs appear to be mediate distinct effects in rat-1 fibroblasts in which the Perez laboratory reported that stimulation of the α1aAR and α1dAR causes G1-S cell cycle arrest, while α1bAR mediates cell-cycle progression (61). It is important to note that given recent findings of GPCR heterodimerization and crosstalk, growth effects will be extremely tissue specific and dependent on the cadre of GPCRs that are coexpressed with α1dAR. Finally, hypoxia treatment of isolated cardiomyocytes or whole animal hearts results in a subtype switch where α1aAR and α1bAR decrease dramatically with concurrent α1dAR up-regulation (7, 79). Because hypoxia can result in myocardial hypertrophy to compensate for myocyte loss, this provides yet another example of differential α1AR subtype regulation in which a significant increase in α1dAR proportion correlates with cellular and/or tissue growth. Taken together, these data support a model where α1AR subtype switching (yielding predominant α1dAR subtype expression) results in a permissive growth phenotype. It is tantalizing to speculate that this may enable α1AR stimulation to alter coupling from standard signaling pathways (e.g., IP turnover) to growth-regulated pathways in a subset of clinically relevant tissues such as bladder, and implicates a key role for regulation of α1dAR transcription in this process.

In summary, we provide the first evidence of methylation-dependent regulation of any adrenergic receptor gene and show Sp1 is a direct regulator of α1dAR basal expression that may play a key role in coordinated α1AR subtype expression to lead to a permissive growth phenotype. Our results suggest Sp1 binding may play a crucial role in specific responses of the α1ARs to stresses such as hypoxia and growth response in the vasculature and myocardium. Together with data from other laboratories, we hypothesize a central role for Sp1 (either directly or indirectly by recruitment of other factors) in the integration of growth signals from multiple regulatory pathways to set proper α1dAR levels. This is highly relevant clinically since this receptor has 10-fold higher affinity for endogenous neurotransmitters than other α1AR subtypes, thus increasing the proportion of α1dAR in the total α1ARs can have a profound effect on α1AR signaling (22). Future studies will seek to confirm that epigenetic regulation governs endogenous α1dAR gene is regulated in native human tissues to preclude cell culture-specific processes. Within this context, it will be important to examine the effect of methylation on endogenous α1dAR expression in response to various growth modulators.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants #AG17566 and HL49103 (DAS). Dr. Schwinn is a Senior Fellow in the Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University Medical Center.

References

- 1.Leech CJ, Faber J. Different a-adrenoceptor subtypes mediate constriction of arterioles and venules. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1996;270:H710–H722. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.2.H710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anyukhovsky EP, Steinberg SF, Cohen IS, Rosen MR. Receptor-effector coupling pathway for alpha 1-adrenergic modulation of abnormal automaticity in ‘ischemic’ canine Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1994;74:937–944. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.5.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin F, Owens WA, Chen S, Stevens ME, Kesteven S, Arthur JF, Woodcock EA, Feneley MP, Graham RM. Targeted alpha(1A)-adrenergic receptor overexpression induces enhanced cardiac contractility but not hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2001;89:343–350. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.095912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruffolo RR., Jr Distribution and function of peripheral α-adrenoceptors in the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1985;22:827–833. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(85)90535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allen KB, Salam AA, Lumsden AB. Acute mesenteric ischemia after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Vasc Surg. 1992;16:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reilly PM, Bulkley GB. Vasoactive mediators and splanchnic perfusion. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:S55–S68. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199302001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michelotti G, Bauman M, Smith M, Schwinn D. Cloning and characterization of the rat α1a-adrenergic receptor gene promoter: demonstration of cell-specificity and regulation by hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8693–8705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koshimizu TA, Tanoue A, Hirasawa A, Yamauchi J, Tsujimoto G. Recent advances in alpha1-adrenoceptor pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michelotti GA, Price DT, Schwinn DA. Alpha-1-adrenergic receptor regulation: basic science and clinical implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;88:281–309. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(00)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price D, Chari R, Berkowitz D, Meyers W, Schwinn D. Expression of α1-adrenergic receptor subtype mRNAs in rat tissues and human SK-N-MC neuronal calls: implications for α1-adrenergic subtype classification. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price D, Lefkowitz R, Caron M, Schwinn D, Berkowtiz D. Localization of mRNA for three distinct α1-adrenergic subtypes in human tissues: implications for human α-adrenergic physiology. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudner X, Berkowitz D, Booth J, Funk B, Cozart K, D’Amico E, El-Moalem H, Page S, Richardson C, Winters B, et al. Subtype-specific regulation of human vascular alpha(1)-adrenergic receptors by vessel bed and age. Circulation. 1999;100:2336–2343. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.23.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Razik M, Lee K, Price R, Williams M, Ongjoco R, Dole M, Rudner X, Kwatra M, Schwinn DA. Transcriptional regulation of the human α1a-adrenergic receptor gene: characterization of the 5′-regulatory and promoter region. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28237–28346. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramarao CS, Kincade Denker JM, Perez DM, Gaivin RJ, Riek RP, Graham RM. Genomic organization and expression of the human alpha1B-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21936–21945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell TD, Rokosh DG, Simpson PC. Cloning and characterization of the mouse alpha1C/A-adrenergic receptor gene and analysis of an alpha1C promoter in cardiac myocytes: role of an MCAT element that binds transcriptional enhancer factor-1 (TEF-1) Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:1225–1234. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuscik MJ, Piascik MT, Perez DM. Cloning, cell-type specificity, and regulatory function of the mouse alpha(1B)-adrenergic receptor promoter. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1288–1297. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao B, Kunos G. Isolation and characterization of the gene encoding the rat alpha 1B adrenergic receptor. Gene. 1993;131:243–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90300-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xin X, Yang N, Faber JE. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB inhibits rat alpha1D-adrenergic receptor gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells by inducing AP- 2-like protein binding to alpha1D proximal promoter region. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1152–1161. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milano CA, Dolber PC, Rockman HA, Bond RA, Venable ME, Allen LF, Lefkowitz RJ. Myocardial expression of a constitutively active alpha 1B-adrenergic receptor in transgenic mice induces cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10109–10113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rokosh D, Stewart A, Chang K, Bailey B, Karliner J, Camacho S, Long C, Simpson P. α1-adrenergic receptor subtype mRNAs are differentially regulated by α1-adrenergic and other hypertrophic stimuli in cardiac myocytes in culture and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5839–5843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibata K, Katsuma S, Koshimizu T, Shinoura H, Hirasawa A, Tanoue A, Tsujimoto G. Alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes differentially control the cell cycle of transfected CHO cells through a cAMP-dependent mechanism involving p27Kip1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:672–678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201375200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwinn D, Johnston G, Page S, Mosley M, Wilson K, Worman N, Campell S, Fidock M, Furness L, Parry-Smith D, et al. Cloning and pharmacological characterization of human α1-adrenergic receptors: sequence corrections and direct comparison with other species homologues. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:134–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keffel S, Alexandrov A, Goepel M, Michel MC. alpha(1)-adrenoceptor subtypes differentially couple to growth promotion and inhibition in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272:906–911. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minneman KP, Lee D, Zhong H, Berts A, Abbott KL, Murphy TJ. Transcriptional responses to growth factor and G protein-coupled receptors in PC12 cells: comparison of alpha(1)-adrenergic receptor subtypes. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2392–2400. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun J, Zuscik MJ, Gonzalez-Cabrera P, McCune DF, Ross SA, Gaivin R, Piascik MT, Perez DM. Gene expression profiling of α1b-adrenergic receptor-induced cardiac hypertrophy by oligonucleotide arrays. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:443–455. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00696-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hampel C, Dolber P, Smith M, Savic S, Thuroff J, Thor K, Schwinn D. Modulation of α1-adrenergic receptor subtype expression by bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2002;167:1513–1521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De May C. Cardiovascular effects of alpha-blockers used for the treatment of symptomatic BPH: impact on safety and well-being. Eur Urol. 1998;34(Suppl 2):18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunn CJ, Matheson A, Faulds DM. Tamsulosin: a review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in the management of lower urinary tract symptoms. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:135–161. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Narayan P, Lepor H. Long-term, open-label, phase III multicenter study of tamsulosin in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2001;57:466–470. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price D. Potential mechanisms of action of superselective alpha(1)-adrenoceptor antagonists. Eur Urol. 2001;40(Suppl 4):5–11. doi: 10.1159/000049889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwinn D, Michelotti G. α1-adrenergic receptors in the lower urinary tract and vascular bed: potential role for the α1d subtype in filling symptoms and effects of ageing on vascular expression. Br J Urol. 2000;85:6–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Price D, Rudner X, Michelotti G, Schwinn D. Immortalization of a human prostate stromal cell line using a recombinant retroviral approach. J Urol. 2000;164:2145–2150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xin X, Yang N, Eckhart AD, Faber JE. Alpha1D-adrenergic receptors and mitogen-activated protein kinase mediate increased protein synthesis by arterial smooth muscle. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:764–775. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.5.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibarra M, Terron JA, Lopez-Guerrero JJ, Villalobos-Molina R. Evidence of an age-dependent functional expression of α1D-adrenoceptor in the rat vasculature. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;322:221–224. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brero A, Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC. Replication and translation of epigenetic information. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;301:21–44. doi: 10.1007/3-540-31390-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson KD. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holmes R, Soloway PD. Regulation of imprinted DNA methylation. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;113:122–129. doi: 10.1159/000090823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sado T, Ferguson-Smith AC. Imprinted X inactivation and reprogramming in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Hum Mol Genet 14 Spec No. 2005;1:R59–R64. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feinberg AP, Ohlsson R, Henikoff S. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laird PW. Cancer epigenetics. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(Spec No 1):R65–R76. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doerfler W. De novo methylation, long-term promoter silencing, methylation patterns in the human genome, and consequences of foreign DNA insertion. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;301:125–175. doi: 10.1007/3-540-31390-7_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campanero MR, Armstrong MI, Flemington EK. CpG methylation as a mechanism for the regulation of E2F activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6481–6486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100340697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenger RH, Kvietikova I, Rolfs A, Camenisch G, Gassmann M. Oxygen-regulated erythropoietin gene expression is dependent on a CpG methylation-free hypoxia-inducible factor-1 DNA-binding site. Eur J Biochem. 1998;253:771–777. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2530771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tate PH, Bird AP. Effects of DNA methylation on DNA-binding proteins and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3:226–231. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fan Y, Nikitina T, Zhao J, Fleury TJ, Bhattacharyya R, Bouhassira EE, Stein A, Woodcock CL, Skoultchi AI. Histone H1 depletion in mammals alters global chromatin structure but causes specific changes in gene regulation. Cell. 2005;123:1199–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma D, Blum J, Yang X, Beaulieu N, Macleod AR, Davidson NE. Release of methyl CpG binding proteins and histone deacetylase 1 from the estrogen receptor alpha (ER) promoter upon reactivation in ER-negative human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1740–1751. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyes J, Bird A. Repression of genes by DNA methylation depends on CpG density and promoter strength: evidence for involvement of a methyl-CpG binding protein. EMBO J. 1992;11:327–333. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Majumder S, Kutay H, Datta J, Summers D, Jacob ST, Ghoshal K. Epigenetic regulation of metallothionein-i gene expression: differential regulation of methylated and unmethylated promoters by DNA methyltransferases and methyl CpG binding proteins. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:1300–1316. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang G, Wei LN, Loh HH. Transcriptional regulation of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene by CpG methylation: involvement of Sp3 and a methyl-CpG-binding protein, MBD2, in transcriptional repression of mouse delta-opioid receptor gene in Neuro2A cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40550–40556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin SG, Jiang CL, Rauch T, Li H, Pfeifer GP. MBD3L2 interacts with MBD3 and components of the NuRD complex and can oppose MBD2-MeCP1-mediated methylation silencing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12700–12709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mulero-Navarro S, Carvajal-Gonzalez JM, Herranz M, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, Ropero S, Esteller M, Fernandez-Salguero PM. The dioxin receptor is silenced by promoter hypermethylation in human acute lymphoblastic leukemia through inhibition of Sp1 binding. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1099–1104. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Q, Rubenstein JN, Jang TL, Pins M, Javonovic B, Yang X, Kim SJ, Park I, Lee C. Insensitivity to transforming growth factor-beta results from promoter methylation of cognate receptors in human prostate cancer cells (LNCaP) Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2390–2399. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Malloy B, Price D, Price R, Bienstock A, Dole M, Funk B, Donatucci C, Schwinn D. α1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human detrusor. J Urol. 1998;160:937–943. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62836-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stewart AF, Rokosh DG, Bailey BA, Karns LR, Chang KC, Long CS, Kariya K, Simpson PC. Cloning of the rat alpha 1C-adrenergic receptor from cardiac myocytes alpha 1C, alpha 1B, and alpha 1D mRNAs are present in cardiac myocytes but not in cardiac fibroblasts. Circ Res. 1994;75:796–802. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Podgoreanu MV, Michelotti GA, Sato Y, Smith MP, Lin S, Morris RW, Grocott HP, Mathew JP, Schwinn DA. Differential cardiac gene expression during cardiopulmonary bypass: ischemia-independent upregulation of proinflammatory genes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gee JE, Blume S, Snyder RC, Ray R, Miller DM. Triplex formation prevents Sp1 binding to the dihydrofolate reductase promoter. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11163–11167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morris DP, Price RR, Smith MP, Lei B, Schwinn DA. Cellular trafficking of human alpha1a-adrenergic receptors is continuous and primarily agonist-independent. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:843–854. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.000430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morris DP, Michelotti GA, Schwinn DA. Evidence that phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II carboxyl-terminal repeats is similar in yeast and humans. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31368–31377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501546200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng Q, Si X, Horstmann H, Xu Y, Hong W, Pallen CJ. Prenylation-dependent association of protein-tyrosine phosphatases PRL- 1, −2, and −3 with the plasma membrane and the early endosome. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21444–21452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frommer M, McDonald LE, Millar DS, Collis CM, Watt F, Grigg GW, Molloy PL, Paul CL. A genomic sequencing protocol that yields a positive display of 5-methylcytosine residues in individual DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1827–1831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lo K, Smale ST. Generality of a functional initiator consensus sequence. Gene. 1996;182:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Shi T, Yun J, McCune DF, Rorabaugh BR, Perez DM. Differential regulation of the cell cycle by alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5157–5167. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gonzalez-Cabrera PJ, Gaivin RJ, Yun J, Ross SA, Papay RS, McCune DF, Rorabaugh BR, Perez DM. Genetic profiling of alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes by oligonucleotide microarrays: coupling to interleukin-6 secretion but differences in STAT3 phosphorylation and gp-130. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1104–1116. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bouwman P, Philipsen S. Regulation of the activity of Sp1-related transcription factors. Molec Cell Endocrinol. 2002;195:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gao B, Kunos G. Transcription of the rat alpha 1B adrenergic receptor gene in liver is controlled by three promoters. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15762–15767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Azizkhan J, Jensen D, Pierce A, Wade M. Transcription from TATA-less promoters: dihydrofolate reductase as a model. Crit Rev Eukary Gene Express. 1993;3:229–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gill G, Pascal E, Tseng Z, Tjian R. A glutamine-rich hydrophobic patch in transcription factor Sp1 contacts the dTAF11110 component of the drosophila TFIID complex and mediates transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:192–196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chiang C, Roeder R. Cloning of an intrinsic human TFIID subunit that interacts with multiple transcriptional activators. Science. 1995;267:531–536. doi: 10.1126/science.7824954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bahouth SW, Beauchamp MJ, Vu KN. Reciprocal regulation of beta 1-adrenergic receptor gene transcription by Sp1 and early growth response gene 1: induction of EGR-1 inhibits the expression of the beta 1-adrenergic receptor gene. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:379–390. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen J, Spector MS, Kunos G, Gao B. Sp1-mediated transcriptional activation from the dominant promoter of the rat alpha1B adrenergic receptor gene in DDT1MF-2 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23144–23150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kass SU, Pruss D, Wolffe AP. How does DNA methylation repress transcription? Trends Genet. 1997;13:444–449. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16:6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aoyama T, Okamoto T, Nagayama S, Nishijo K, Ishibe T, Yasura K, Nakayama T, Nakamura T, Toguchida J. Methylation in the core-promoter region of the chondromodulin-I gene determines the cell-specific expression by regulating the binding of transcriptional activator Sp3. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28789–28797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ammanamanchi S, Kim SJ, Sun LZ, Brattain MG. Induction of transforming growth factor-beta receptor type II expression in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells through SP1 activation by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16527–16534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu WG, Srinivasan K, Dai Z, Duan W, Druhan LJ, Ding H, Yee L, Villalona-Calero MA, Plass C, Otterson GA. Methylation of adjacent CpG sites affects Sp1/Sp3 binding and activity in the p21(Cip1) promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4056–4065. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4056-4065.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kudo S. Methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 represses Sp1-activated transcription of the human leukosialin gene when the promoter is methylated. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5492–5499. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brandeis M, Frank D, Keshet I, Siegfried Z, Mendelsohn M, Nemes A, Temper V, Razin A, Cedar H. Sp1 elements protect a CpG island from de novo methylation. Nature. 1994;371:435–438. doi: 10.1038/371435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang Y, Fatima N, Dufau ML. Coordinated changes in DNA methylation and histone modifications regulate silencing/derepression of luteinizing hormone receptor gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7929–7939. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.7929-7939.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]