Abstract

Much attention is being paid to protein databases as an important information source for proteome research. Although used extensively for similarity searches, protein databases themselves have not fully been characterized. In a systematic attempt to reveal protein-database characters that could contribute to revealing how protein chains are constructed, frequency distributions of all possible combinatorial sets of three, four, and five amino acids (“triplets,” “quartets,” and “pentats”; collectively called constituent sequences) have been examined in the nonredundant (nr) protein database, demonstrating the existence of nonrandom bias in their “availability” at the population level. Nonexistent short sequences of pentats were found that showed low availability in biological proteins against their expected probabilities of occurrence. Among them, six representative ones were successfully synthesized as peptides with reasonably high yields in a conventional Fmoc method, excluding the possibility that a putative physicochemical energy barrier in forming them could be a direct cause for the low availability. They were also expressed as soluble fusion proteins in a conventional Escherichia coli BL21Star(DE3) system with reasonably high yield, again excluding a possible difficulty in their biological synthesis. Together, these results suggest that information on three-dimensional structures and functions of proteins exists in the context of connections of short constituent sequences, and that proteins are composed of evolutionarily selected constituent sequences, which are reflected in their availability differences in the database. These results may have biological implications for protein structural studies.

Keywords: protein sequence, database search, sequence availability, constituent sequence, rare short sequence

Partly due to the worldwide genome projects, there are now >1.5 million records of amino acid sequences of proteins accumulated in public databases. In this post-genome era, much attention is being paid to these protein databases as an important information source for proteome research (Boguski and Mclntosh 2003; Tyers and Mann 2003). Historically, fundamental knowledge of secondary structure prediction of proteins came from the database characterization performed in the 1970s with a limited number of protein records, which revealed the importance of short amino acid sequences (Chou and Fasman 1974; Lim 1974; Garnier et al. 1978). For example, we now know that key residues in “active sites” of proteins are often composed of a small number of amino acids, although these sites must be three-dimensionally supported by other residues to form characteristic structures (Ramachandran and Sassiekharan 1968; Chothia 1984). Many hairpin loops, which often participate in active sites, are composed of just a few residues, usually three to five residues in length. Packing of two α-helices is made between the ridge of one helix and the groove of the other helix, which are mostly made of three or four residues (Chothia et al. 1981).

Since then, protein databases have been used almost exclusively for similarity searches (Altschul et al. 1990, 1997; Jonassen 2000; Yona and Brenner 2000; Baldi and Brunak 2001; Mount 2001; Schuler 2001). Although highly successful, this approach might have difficulty in identifying short, but functional sequences of amino acids in proteins. On the other hand, few systematic studies on protein database characters themselves have been performed. Since proteomics is expected to play an important role in biological sciences (Boguski and Mclntosh 2003; Tyers and Mann 2003), it would be highly valuable to statistically characterize the present-day protein database with >1.5 million records.

Accordingly, we pursued an approach alternative to similarity searches. Since the present-day protein database have accumulated hypothetical protein sequences derived from genome projects, characterization of the database itself would reveal fundamental knowledge on how protein chains are constructed. Our data suggest that information on the primary structure of proteins exists in the context of connections of short sequences. We also show that some amino acid sequences of proteins occur much less frequently than expected and discuss possible implications of the existence of these rare short sequences in proteins.

Results and Discussion

Rationale for the protein database characterization

Proteins coded in human genome are expected to number about 3.5 × 104. If any combinations of 20 amino acids are equally possible, there are 1.3 × 10130 ( = 20100) possible amino acid sequences in proteins being composed of 100 amino acids. Thus, we easily understand that only a very limited number of sequences of amino acids of theoretically possible ones are utilized in real proteins. Furthermore, if amino acids in all proteins coded in the human genome are boldly estimated to number ~108, the combinatorial sets of seven amino acids in them, which is ~108, is only one-tenth of the all possible combinatorial sets of seven amino acids, 1.3 × 109 ( = 207). That is, only one-tenth of the theoretically possible sets of seven amino acids are used in real proteins and found in the protein databases.

This discussion above, however, is based on the presumption that all 20 amino acids are randomly utilized in equal frequency. Obviously, this is not the case in real proteins. Accordingly, to examine which sets of amino acids are frequently used and which are rarely used, one of the fundamental questions in protein science, it is necessary to study how frequently a given set of short amino acid sequence appears in the database against the random probability of occurrence, i.e., to clarify differences in availability of short sequences. In this study, we considered proteins to be composed of unit sequences of n amino acids (n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). We call these unit sequences constituent sequences, and investigated how frequently they appeared in the nonredundant (nr) protein database. In other words, we first generated all possible combinatorial sets of three, four, and five amino acids (203 or 8000 triplet species, 204 or 160,000 quartet species, and 205 or 3,200,000 pentat species, respectively) (Table 1), assuming these sets as a unit of information, and asked how these sets of amino acids occur in the database.

Table 1.

Numbers of combinatorial sets of n amino acids

| Doublet | Triplet | Quartet | Pentat | Hexat | Heptat | |

| Combinatorial set (P = 20n) | 4 × 102 | 8 × 103 | 1.6 × 105 | 3.2 × 105 | 6.4 × 107 | 1.28 × 109 |

| Number in the database (Q)a | 495,984,222 | 494,444,974 | 492,905,726 | 491,366,478 | 489,827,230 | 488,287,982 |

| Q/Pb | 1.2 × 106 | 6.2 × 104 | 3.1 × 103 | 1.5 × 102 | 8 | 0 |

The nr database was downloaded as of September 29, 2003, which contained 1,539,248 entry records after eliminating artificial sequence records and unknown or nonstandard amino acid residues, B (asparatate or asparagine), U (selenocysteine), Z (glutamate or glutamine), and X (any amino acids).

a Q was calculated according to equation 6.

b Q/P indicates the number of combinatorial sets of n amino acids when each amino acid species equally represents 1/20 of the population, serving as a rough indicator for the number of the given combinatorial sets of n amino acids in the nr database.

Amino acid composition of proteins

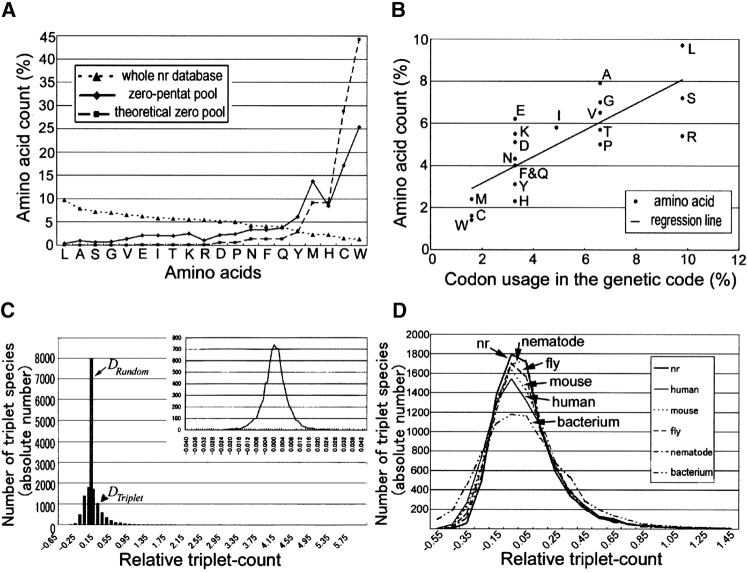

As a first step to characterize the nr protein database, we studied the amino acid composition (or defined here as “amino acid count” for each chemical species of 20 amino acids) of the whole nr protein database (Fig. 1A ▶, dotted line). Relative amino acid counts varied from 9.68% (leucine, L) to 1.35% (tryptophan, W), and these values were used for calculations of theoretical counts for each triplet, quartet, and pentat species to take into account this nonuniform nature (see below). It is worth noting that this rank order of the amino acid count showed no clear rules in terms of chemical nature of amino acids such as hydrophobicity. Interestingly, however, the relative amino acid count showed reasonable correlation with the codon usage in the universal genetic code with Spearman correlation coefficient 0.81 (Fig. 1B ▶), confirming the relation that was previously found with a much smaller number of samples (King and Jukes 1969; Jukes 1973; Jukes et al. 1975). This result supported the notion that the nr database is a reliable reflection of proteins on the earth, whose production is primarily based on the universal genetic code.

Figure 1.

Amino acid count and triplet count in protein databases. (A) Percentage of amino acid counts (relative amino acid counts) in the nr protein database (dotted line), zero-pentat pool (solid line), and theoretical zero-pentat pool (broken line). Amino acids in the X-axis are rank-ordered according to the counts in the whole nr database. Amino acids used less in the nr protein database are used frequently in the zero-pentat pool, indicating their inverse relation. Also note the usage difference between real and theoretical zero-pentat pools. (B) Correlation between the relative amino acid count in the nr protein database and the codon usage in the universal genetic code. Codon usage was determined as the relative number of codons that specify a given amino acid among 61 codons that code for amino acids. Spearman correlation coefficient is 0.81. Regression line is drawn. (C) Triplet-count distribution after operational transformation in the nr protein database. X axis shows relative triplet-count, and Y-axis shows its frequency (triplets) in absolute number. Theoretical triplet-count distribution generated randomly (DRandom) is expressed as a single bar in this histogram. In contrast, real triplet-count distribution (DTriplet) is markedly different. Inset shows the theoretical random distribution (DRandom) with much smaller bar width, indicating its normality. (D) Species-specific triplet-count distributions. Data were treated as in C, except that they were separately examined according to species to which original records belong. Both right and left sides of this graph were truncated.

Triplet distribution revealed availability differences for some sequences

We then statistically examined the frequency distribution of “triplet count” (defined as the number of each triplet that appeared in the nr database). We first constructed a histogram for triplet count, together with a histogram for theoretical triplet-count generated randomly from an imaginary pool of amino acids whose composition was identical to that of the nr database (data not shown), thus taking into account the nonuniform nature of the amino acid composition. Clear comparison to each other was then made through an operational transformation according to equations 4 and 5 to yield their relative values (Fig. 1C ▶). If amino acids were assigned randomly to each position within protein chains even from the biased composition, the distribution of the randomly generated triplet-count must show no difference from that of the real triplet-count. In reality, the distribution of the relative real triplet-count (DTriplet) had much larger range with much smaller peak than the random fluctuations of relative triplet-count (DRandom) (Fig. 1C ▶). Some triplets were used much more than expected in the database, and other triplets much less than expected. This difference thus demonstrated that amino acids were not used randomly even from the biased composition in constructing protein chains at least at the population level, implying the existence of the probabilistic influence of a given amino acid chosen for a particular location to those of the surrounding positions at the level of triplet. We considered these relative counts to be a quantitative expression of availability of short amino acid sequences.

It is obvious that the more database records increase, the less frequency distribution of relative triplet-count is biased by nonrandom sampling of sequence records, because the sample population becomes closer to the parent population, a collection of all protein species on the earth. Since there are already 1.5 million records in the nr protein database, it is unlikely that the characteristic triplet-count distribution shown above is simply an artifact due to a database bias itself. However, the possibility still exists that the characteristic distribution might have resulted from over-representation or under-representation of particular proteins in the database. To examine this possibility, we further performed similar triplet analyses in five phylogenetically distinct biological species, human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), soil nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans), and a colon bacterium (Escherichia coli), whose genome sequences have already been known.

We first obtained amino acid composition in each species. Although they were slightly different from one another, their overall trend of the ranked count seemed to be almost identical to that of the whole nr database and almost invariable throughout species (data not shown). According to equations 4 and 5, we further obtained histograms for the relative triplet-count distributions in each species (Fig. 1D ▶). They were all essentially similar to that of the whole nr protein database, compared with the randomly generated one in terms of fundamental statistical values (data not shown). Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test with Bonferroni correction indicated that they were all similar to one another with P > 0.01 (data not shown), except the combination of human and nematode (P = 8.27 × 10−6), and this significant difference between these two species seemed to arise mainly from the difference in peak values. This result excluded the possibility that the nonrandom nature of the triplet composition was a mere reflection of an artificial database bias. We concluded that this nonrandom nature seemed to originate not from an inherent bias of the database itself, but from some biological reasons. This tendency of low availability of particular constituent sequences was also observed in the frequency distribution of quartet count and also of pentat count (data not shown).

Some pentat species never appeared in the database

Although all 8000 triplet species and all 160,000 quartet species existed in the database in spite of this low availability, some particular pentat species never appeared in the database, which we called “zero-count pentats.” The zero-count pentats can be considered as a representative case where low availability of particular constituent sequences was driven to extremes. There were 12,080 zero-count pentat species among all 3,200,000 pentat species, i.e., 0.4% of the entire population. A collection of 12,080 zero-count pentat species, which we called “zero-count pentat pool” or simply “zero-pentat pool,” was thus to be characterized.

For comparison, we calculated “theoretical” pentat-counts for each of 3,200,000 pentat species and generated a “theoretical” zero-pentat pool from an imaginary pool of amino acids whose composition was identical to that of the nr database, thus taking account the biased amino acid composition. Amino acid composition of the real and theoretical zero-count pentat pools (Fig. 1A ▶, solid and broken lines, respectively) was markedly different; most amino acids were used more frequently in the real pool than in the theoretical one, except for histidine, cysteine, and tryptophan. This result again indicated that the real zero-count pentat species cannot be predicted readily from the amino acid composition of the whole nr database. That is, the availability difference was well reflected in the real zero-count pentat pool.

Theoretically, 832 pentat species had counts <1.00, hence, they were expected not to appear even once in the database, whose collection we called “theoretical zero-pentat pool”. There were only 82 theoretical zero-pentat species when applying more stringent criteria, counts <0.50. In reality, 12,080 pentat species never appeared in the nr database, 14.5 times (when applying counts <1.00) and 147.3 times (when applying counts <0.50) more than expected, respectively. Thus, some pentat species never occurred in the database, even though they were expected to appear.

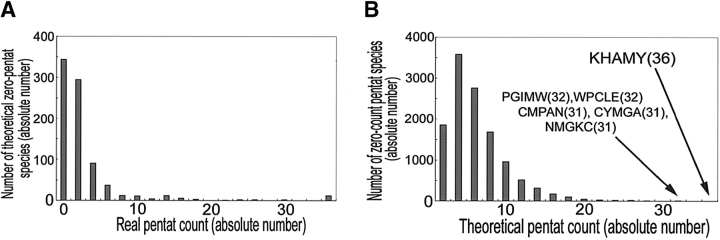

On the other hand, other pentat species occurred in the database, even though they were expected to be zero (Table 2; Fig. 2A ▶). These deviations from the theoretical calculations, based on the nr database composition, showed the existence of not only low availability, but also high availability of some constituent sequences, even if the nonuniform nature of the amino acid composition was taken into account. However, the theoretical zero-count pentat species (832 species) with high real counts showed a repeated usage of a few amino acids such as cysteine, tryptophan, and histidine. Since simple repetition of cysteine, tryptophan, and histidine residues would easily make particular pentat species receive high counts in the nr database, biological significance of these pentats is less clear.

Table 2.

Theoretical zero-count pentat species with the highest real counts

| CCCCC(420)-CCWHC(117)-WCCCC(72)-YCCCC(66)-CWCFW(64)- CHWCH(51)-WCWCF(49)-CCCCY(46)-CWCCC(38)-YWCWC(37)- CCHCC(35)-WCCHC(30)-CYCCC(29)-WWWDC(26) |

Real pentat counts in the whole nr protein database are indicated in parentheses.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the zero-count pentat pool. (A) Frequency distribution of real pentat count for each theoretical zero-pentat species in the theoretical zero-pentat pool (832 species). X-axis is truncated. Maximum, 420 (CCCCC). Bar width, 2. (B) Frequency distribution of expected theoretical pentat count for each zero-count pentat species in the zero-pentat pool. Peak is found around three counts. Total number is 12,080. Minimun, 0; median, 4; and maximum, 36 (KHAMY). Bar width, 2.

In contrast to the theoretical zero-count pentat species with frequent repetitions of limited amino acids, the real zero-count pentat species consisted of varieties of amino acids (Table 3). For example, among the zero-count pentat species, KHAMY had the theoretical pentat count 36, i.e., it was expected to occur 36 times in the database (Table 3). Although this expected count was smaller than the mean value of the theoretical count for each pentat (assuming that the protein sequence data were composed of equal amounts of each amino acid species), which was 154 (Table 1), the fact that 99% of the real zero-count pentat species had expected counts <20 (Fig. 2B ▶) made it likely that those pentats that were highly theoretically deviated had some biological or physicochemical reasons not to be incorporated well as a part of proteins.

Table 3.

Real zero-count pentat species with the highest theoretical counts

| KHAMY(36)-PGIMW(32)-WPCLE(32)-CMPAN(31)-CYMGA(31)- NMGKC(31)-KCAVW(30)-WPPFN(29)-IRWTM(28)-PMNCG(28) |

Theoretical pentat counts (expected) in the real zero-pentat pool are indicated in parentheses.

Zero-count pentats can be synthesized chemically and biologically

We admit that there may be many reasons for the low availability and that different reasons may exist in different zero-count pentats. However, as a first approximation, there would be at least three possible reasons, which should be clearly differentiated, why biological proteins on the earth show low availability of particular constituent sequences in making proteins. The first possibility is simply because of a physicochemical factor such as steric hindrance being unavoidably associated with making such pentats. The second possibility is that the biological translational machinery, but not a binding energy of a pentat molecule, may not be suitable for making them. The third possibility is some evolutionary reasons, although they could easily be made if the system needs to make them.

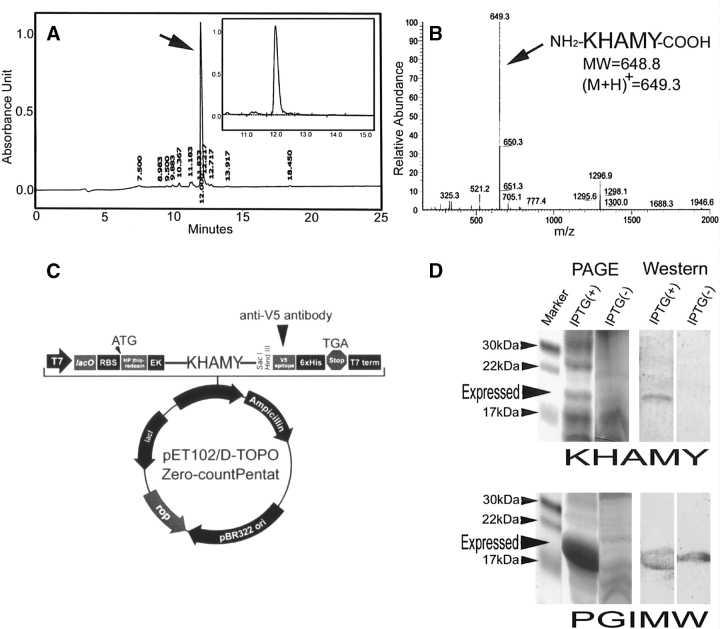

Although unlikely considering a physicochemical nature of peptides, the first and second possibilities were tested simply by chemically synthesizing them as peptides and biologically expressing them as fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. For this purpose, we chose four zero-count pentats with the highest theoretical counts, KHAMY (theoretical pentat count or tpc 36), PGIMW (tpc 32), WPCLE (tpc 32), and CMPAN (tpc 31). We also chose CMWCM (tpc 1) as a representative zero-count pentat because it was composed of CMW, MWC, and WCM, all of which were three most frequently used triplets in the zero-pentat pool (data not shown). For comparison, CMWRL (tpc 13) was also chosen, because it had the highest counts among CMWXX (where X was any amino acids). CMPAN already chosen also served as a good comparison for CMWCM and CMWRL, because it had the highest counts among CMXXX (where X was any amino acids).

These six zero-count pentat species in total showed a variety of chemical characters including hydrophobicity, but were successfully synthesized using a conventional Fmoc method with a reasonably high yield (Table 4; Fig. 3A,B ▶). This result immediately excluded the first possibility. In addition, all were successfully synthesized as a part of soluble proteins using a conventional E. coli BL21Star(DE3) system, although yields somewhat varied (Fig. 3C,D ▶), excluding the second possibility. Thus, the third possibility is most likely. Although we could not exclude the possibility that other zero-count pentats may not be synthesized so easily, it is tempting to speculate that zero-count pentats in general are not highly toxic. It is conceivable that a highly toxic sequence of amino acids may be utilized exactly because of such toxicity as toxins.

Table 4.

Zero-count pentat species synthesized chemically and biologically

| Species | Expected count | Mean hydrophobicitya | Charge densityb | Isoelectric pH | Peptide yieldc | Bacterial expression leveld |

| KHAMY | 36 | −0.94 | 0.6 | 9.1 | 84% | Moderate |

| PGIMW | 32 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 89% | High |

| WPCLE | 32 | 0.06 | 0.6 | 4.1 | 82% | High |

| CMPAN | 31 | 0.22 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 63% | High |

| CMWCM | 1 | 1.58 | 0.4 | 5.6 | 87% | High |

| CMWRL | 13 | 0.56 | 0.6 | 9.4 | 74% | High |

a Mean hydrophobicity was calculated as a sum of Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity of each amino acids. Negative value indicates a hydrophilic nature of peptide.

b Charge density was calculated considering ionic charges of amino acids K, R, D, and E, and both N- and C-terminals of peptide.

c Peptide yield of chemical synthesis by Fmoc method was evaluated by RP-HPLC.

d Level of bacterial expression in BL21Star(DE3) system was evaluated by Coomassie G-250 staining of SDS–polyacrylamide gels.

Figure 3.

Chemical and biological synthesis of six representative zero-count pentats. Results of KHAMY are mainly shown below, but all six pentats were subjected to the same experimental procedure, yielding similar results (data not shown). (A) Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RT–HPLC) of a crude product of a synthetic peptide, KHAMY. Chemical synthesis was carried out by the Fmoc method. The largest peak (indicated by an arrow) occupies 84% of the total peak area of reaction products. (Inset) Enlargement of the largest peak. (B) Mass spectrum (MULDI-TOF-MS) of a crude product of a synthetic peptide, KHAMY. The largest peak (an arrow) is found at 649.3 as predicted, indicating that chemical synthesis was successful. (C) Expression plasmid vector pET102/D-TOPO with an insert of small DNA fragment encoding KHAMY. The insert was flanked by His-Patch (HP)-thioredoxin and enterokinase recognition site (EK) at the N-terminal side and by V5 epitope and 6×His tag at the C-terminal side. Thus, KHAMY is expressed as a fusion protein. The expression is driven by T7 promoter, which permits high level, IPTG-inducible expression. Expression can be checked using anti-V5 antibody. (D) Expression of a fusion protein with KHAMY (or PGIMW). Results of SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using anti-V5 antibody are shown. In the presence of IPTG, a large amount of PGIMW fusion protein was expressed, as clearly seen in the Coomassie staining of the gel. Yield of KHAMY was much lower, but its expression was still detected by the Coomassie staining. Other four zero-count pentats showed the expression level almost identical to that of PGIMW.

Possible implications of the availability differences in proteins

Various availability of different constituent sequences revealed in this study suggests that information on the primary structure of proteins exists in the context of connections of words (constituent sequences) of proteins. Further systematic studies on short amino acid sequences could eventually unveil grammars that govern three-dimensional structures and functions of proteins.

The varied availability detected in this study could be considered as a remnant of a fixed evolutionary accident, but this putative “fixation” is fundamentally different from that of the genetic code, for example. The latter cannot be changed once the system has started to be used, but the former can at least theoretically be revised or ignored easily. Our results imply that proteins on the earth highly evolved in the direction where functionally useful constituent sequences were repeatedly used in any parts of proteins. Thus, instead of an evolutionary remnant, it could be a consequence of functional protein evolution.

Among the zero-pentat pool, there was no significant positional bias in the amino acid usage among five positions of amino acids in a pentat (data not shown). However, this does not exclude the possibility that some distribution patterns of certain amino acids exist in the zero-pentat pool. Indeed, it is known that certain patterns of hydrophobic and nonhydrophobic amino acids are favored in α-helices (Vazquez et al. 1993). Similarly, binary patterns of polar and nonpolar amino acids are favored in α-helices and solvent-exposed β-strands (West and Hecht 1995), whose biological significance is at least partially known (Broome and Hech 2000; Mandel-Gutfreund and Gregoret 2002).

In this context, it would be valuable to examine relationships between secondary structures and triplets, quartets, and pentats. As some residues are preferred in a given secondary structure (Chou and Fasman 1974; Lim 1974; Garnier 1978), some pentats, for example, may be favored in a given secondary structure. Availability difference may be a reflection of the number of these secondary structures in proteins at the population level. Another possibility is that proteins containing a particular triplet, quartet, or pentat may preferably belong to a particular protein family, and the family composition in the database may be a cause of the nonrandom nature of the frequency distributions of triplet, quartet, and pentat counts. It is reasonable that protein records for a given triplet, quartet, or pentat are to be examined with respect to structural and functional protein classifications using specialized databases such as PDB (Protein Data Bank) (Berman et al. 2000) and SCOP (Structural Classification of Proteins) (Murzin et al. 1995). Alternatively, more sophisticated algorithms (Rigoutsos and Floratos 1998; Huynh and Rigoutsos 2004) may help us to elucidate such relations. These studies could reveal a hidden logic of building protein chains.

It is well known that structural and functional similarities among proteins are frequently conserved in a stretch of a few amino acids. A notable example can be drawn from the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily, in which little sequence similarity can be found unless two receptors are very closely related (Schwartz 1996; Wess 1998). This makes the conventional similarity search much less useful than one might expect. The combinatorial analyses for triplet, quartet, and pentat performed here can be considered to be complementary to similarity searches. There are several sites with just a single or a few residues that are relatively conserved and functionally important among a group of GPCRs, one of which is called “DRY sequence” (triplet of aspartic acid, arginine, and tyrosine) located at the boundary between the third transmembrane domain and the second intracellular loop (Schwartz 1996; Wess 1998; Ohyama et al. 2002; Wilbanks et al. 2002). Since GPCRs cannot readily be classified based on similarity alignments of sequences, several lines of research already proposed new methods for characterizing GPCR sequences with or without alignments (Graul and Sadee 2001; Otaki and Firestein 2001; Karchin et al. 2002; Lapinsh et al. 2002), one of which is an alignment-independent method using principal component analysis (Lapinsh et al. 2002). This method takes into account functional contributions of all amino acids in GPCRs. Effectiveness of this method indicated varied but significant contributions of all amino acids to the final classification, in contrast to more traditional alignment-based methods that consider only the most important ones, or conventional motifs. Consistent with this, triplet, quartet, and pentat analyses performed here also indicated that any part of a protein molecule is better considered to be composed of evolutionarily selected constituent sequences. In other words, almost any amino acids at a given site influence neighboring ones.

Although most, if not all, zero-count pentats detected in the database as of September 2003 may exist in some proteins on the earth (indeed, some of them already exist in the database as of July 2004), they might be useful in designing proteins with a new folding pattern and a unique biological character. Physiologically important protease-sensitive proteins may be transformed into protease-resistant ones with the use of zero-count pentats.

Materials and methods

Database and sample records

We analyzed all entry records (n = 1,543,320) of the “nonredundant” protein database maintained by NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) (Wheeler et al. 2002). Nonredundant indicates that identical sequence entries are represented by one entry when they have identical lengths and identical residues at every position. We downloaded the “nr.Z” FASTA file from the NCBI FTP site, ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/db/ as of September 29, 2003. This file contains all nonredundant records of PDB (Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics), Swiss-Prot (Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics and European Bioinformatic Institute), PIR (Protein Information Resource, National Biomedical Research Foundation, Georgetown University Medical Center), and conceptual translations of GenBank coding sequences. All data were then converted to XML (Extensible Markup Language) documents with several tags. Sample records with annotation of mutant, mutation, engineered, or engineering in the definition section were deleted, leaving 1,539,248 records. Although this exclusion of artificially created sequences may not be complete, the remaining artificial records, if any, would be insignificant in terms of the data analyses performed afterward. Furthermore, unknown and nonstandard amino acids (B, Z, U, and X) were not considered as a part of possible pentats to be analyzed.

Definitions and operations

We first analyzed 8000 combinatorial sets of three amino acids (triplets). Detailed procedures were described elsewhere (Otaki et al. 2003). A three-amino-acid window that defines a triplet in a large linear sequence is conceptually slid one by one along the protein chain, so that a given amino acid residue is an overlapping part of three different triplets unless it is located at the ends of the chain. Thus, the total number of existing triplets in all sample records (defined as Q below) can be written as:

|

(1) |

Where nj is the number of amino acid residues in a given protein j, N is the number of protein records in the database, and A is the total number of amino acid residues in the database. Alternatively, based on triplet count for each triplet akalam or α in the database, Tk•l•m or Tα, the total number of existing triplets (Q) can be expressed as follows, considering there are 8000 different triplets:

|

(2) |

Conversely, from the probabilistic expression of amino acid count for each amino acid (p, q, or r) in the database, Pp, Pq, or Pr, the expected triplet count, Eα, for each triplet apaqar or α is given as follows:

|

(3) |

Difference between theoretically estimated triplet count Eα and the real triplet count Tα for each triplet in the database is expressed as follows:

|

(4) |

Likewise, difference between theoretically estimated triplet count Eα and randomly generated triplet count Rα from the population with the identical amino acid composition is expressed as follows:

|

(5) |

We call DTriplet and DRandom relative triplet-counts. The frequency distribution of DRandom is supposed to show random fluctuations of the sampling procedure itself around a central value, resulting in the normal error curve. Distribution histograms for DTriplet and DRandom were compared with each other.

Similar operations were performed in analyzing quartets and pentats. General expression of equation 1 for the total number of combinations of n amino acids in the nr protein databases can be written as:

|

(6) |

This equation was used to calculate the number of combinations Q in Table 1.

Computer programs

We developed a program in JAVA to count the number of each amino acid and each triplet in the database, and to subsequently execute several operations. The output data were exported to the Microsoft Excel 2000 and processed numerically and graphically. Statistical analyses were performed using ystat 2002 together with Excel.

To generate a theoretical random distribution from the population with the identical amino acid composition, sampling procedure was exhaustively repeated as many times as the number of amino acid residues in the database, which was equivalent to having a random reconstitute of theoretical proteins from all the real database records that are conceptually broken into pieces of amino acid monomers.

To demonstrate the operational accuracy using the JAVA program developed by ourselves and the one for the random sampling procedure, we used the “ABC model,” in which three imaginary amino acids represented by letters, A, B, and C, were treated using these programs with a given composition and an imaginary population of 100 million letters. In this case, only 27 triplets exist, making the system simpler and amenable to calculations by hand. The output data generated by the programs were compared to the hand-calculated ones. We found these outputs were virtually identical, except for unavoidable fluctuations from the random sampling procedure itself, confirming the operational accuracy (data not shown).

Peptide synthesis and protein expression

Six representative nonbiological pentats were chemically synthesized by Fmoc method using a peptide synthesizer Symphony (Rainin Instrument) and analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP–HPLC) and Mass spectroscopy with the help of QIAGEN laboratory, Japan. RP–HPLC was performed using Gold Nouveau/338 HPLC system (Beckman) equipped with Hydrosphere ODS Vydac C-18 column (L 250 mm × ø 4.6 mm, particle size 5 μm). Samples in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid were separated in the water-acetonitrile solvent gradient system with flow rate 1.0 mL/min. Absorbance was monitored at 215 nm. Mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) was performed with MAT-LC/Q (Finnigan) to confirm the identities of synthetic products.

For bacterial expression, a double-stranded DNA molecule made of two strands of synthetic oligonucleotides corresponding to a zero-pentat amino acid sequence was directionally inserted into an expression vector pET102/D-TOPO (Invitrogen), in which the insert was flanked by thioredoxin in the N-terminal side and V5 epitope in the C-teminal side (Fig. 4C). The recombinant plasmid was isolated from single colonies of Escherichia coli TOP10 and transformed into E. coli BL21Star(DE3). Expression from the T7 promoter was induced with 0.8 mM IPTG in 10 mL LB-ampicillin. Bacterial culture (800 μL aliquot) was sampled at 0, 2, 4, and 6 h after the IPTG addition. Each aliquot was prepared in 60 μL SDS-sample buffer, boiled, and sonicated. This lysate (30 μL each) was applied to 18% Trisglycine SDS–polyacrylamide gel with 1.5 mm thickness. After performing an electrophoresis, protein was either detected on the gel with Colloidal Blue Coomassie G-250 (Invitrogen) or transferred onto a PVDF membrane and probed with anti-V5 antibody conjugated with HRP (Invitrogen). Signals on the membranes were detected using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Vector Lab).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Wada and T. Hiramura for technical help. This work was supported by Grant for the Advancement of Scientific Collaborations from Kanagawa University.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.041092605.

References

- Altschul, S.F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E.W., and Lipman, D.J. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., and Lipman, D.J. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi, P. and Brunak, S. 2001. Bioinformatics: The machine learning approach. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Berman, H.M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T.N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I.N., and Bourne, P.E. 2000. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boguski, M.S. and Mclntosh, M.W. 2003. Biomedical informatics for proteomics. Nature 422 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome, B.M. and Hecht, M.H. 2000. Nature disfavors sequences of alternating polar and non-polar amino acids: Implications for amyloidogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 296 961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia, C. 1984. Principles that determine the structure of proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53 537–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chothia, C., Levitt, M. and Richardson, D. 1981. Helix-to-helix packing in proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 145 215–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, P.Y. and Fasman, G.D. 1974. Prediction of protein conformation. Biochemistry 13 222–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier, J., Osguthorpe, D.J., and Robson, B. 1978. Analysis of the accuracy and implications of simple methods for predicting the secondary structure of globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 120 97–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graul, R.C. and Sadee, W. 2001. Evolutionary relationships among G protein-coupled receptors using a clustered database approach. AAPS PharmSci. 3 E12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, T. and Rigoutsos, I. 2004. The Web server of IBM’s bioinformatics and pattern discovery group: 2004 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 W10–W15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassen, I. 2000. Methods for discovering conserved patterns in protein sequences and structures. In Bioinfromatics: Sequence, structure, and data-banks. A practical approach (eds. D. Higgins and W. Taylor), pp. 143–166. Oxford University Press, New York.

- Jukes, T.H. 1973. Arginine as an evolutionary intruder into protein synthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 53 709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jukes, T.H., Holmquist, R., and Moise, H. 1975. Amino acid composition of proteins: Selection against the genetic code. Science 189 50–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karchin, R., Karplus, K., and Haussler, D. 2002. Classifying G-protein coupled receptors with support vector machines. Bioinformatics 18 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, J.L. and Jukes, T.H. 1969. Non-Darwinian evolution. Science 164 788–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinsh, M., Gutcaits, A., Prusis, P., Post, C., Lundstedt, T., and Wikberg, J.E. 2002. Classification of G-protein coupled receptors by alignment-independent extraction of principal chemical properties of primary amino acid sequences. Protein Sci. 11 795–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, V.I. 1974. Algorithms for prediction of α-helical and β-structural regions in globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 88 873–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. and Gregoret, L.M. 2002. On the significance of alternating patterns of polar and non-polar residues in β-strands. J. Mol. Biol. 323 453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount, D.W. 2001. Bioinformatics: Sequence and genome analysis. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Murzin, A.G., Brenner, S.E., Hubbard, T., and Chothia, T. 1995. SCOP: A structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 247 536–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama, K., Yamano, Y., Sano, T., Nakagomi, Y., Wada, M., and Inagami, T. 2002. Role of the conserved DRY motif on G protein activation of rat angiotensin II receptor type 1A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 292 362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki, J.M. and Firestein, S. 2001. Length analyses of G-protein-coupled receptors. J. Theor. Biol. 211 77–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otaki, J.M., Gotoh, T., and Yamamoto, H. 2003. Frequency distribution of the number of amino acid triplets in the non-redundant protein database. J. Jpn. Soc. Information Knowledge 13 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran, G.N. and Sassiekharan, V. 1968. Conformation of polypeptides and proteins. Adv. Protein. Chem. 28 283–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigoutsos, I. and Floratos, A. 1998. Combinatorial pattern discovery in biological sequences: The TEIRESIAS algorithm. Bioinformatics 14 55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, G.D. 2001. Sequence alignment and database searching. In Bioinformatics: A practical guide to the analysis of genes and proteins (eds. A.D. Baxevanis and B.F.F. Ouellette), pp. 187–214. Wiley-Liss, New York.

- Schwartz, T.W. 1996. Molecular structure of G-protein-coupled receptors. In Textbook of receptor pharmacology (eds. J.C. Foreman and T. Johansen), pp. 65–84. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Tyers, M. and Mann, M. 2003. From genomics to proteomics. Nature 422 193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, S., Thomas, C., Lew, R.A. and Humphreys, R.E. 1993. Favored and suppressed patterns of hydrophobic and nonhydrophobic amino acids in protein sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90 9100–9104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess, J. 1998. Molecular basis of receptor/G-protein-coupling selectivity. Pharmacol. Therapeutics 80 231–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, M.W. and Hecht, M.H. 1995. Binary patterning of polar and nonpolar amino acids in the sequences and structures of native proteins. Protein Sci. 4 2032–2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, D.L., Church, D.M., Edgar, R., Federhen, S., Helmberg, W., Madden, T.L., Pontius, J.U., Schuler, G.D., Schriml, L.M., Sequeira, E., et al. 2002. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information: 2002 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 13–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbanks, A.M., Laporte, S.A., Bohn, L.M., Barak, L.S., and Caron, M.G. 2002. Apparent loss-of-function mutant GPCRs revealed as constitutively desensitized receptors. Biochemistry 41 11981–11989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yona, G. and Brenner, S.E. 2000. Comparison of protein sequences and practical database searching. In Bioinformatics: Sequence, structure, and data-banks. A practical approach (eds. D. Higgins and W. Taylor), pp.167–190. Oxford University Press, NY.